Abstract

The 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 region is found duplicated or deleted in people with cognitive, language, and behavioral impairment. We report on a family (a father and 3 male twin siblings) that presents with a duplication of the 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 region and a variable phenotype: the father and the fraternal twin are normal carriers, whereas the monozygotic twins exhibit severe language and cognitive delay as well as behavioral disturbances. The genes located within the duplicated region are involved in brain development and function, and some of them are related to language processing. The probands' phenotype may result from changes in the expression level of some of these genes important for cognitive development.

Keywords: Copy number variations, Cognitive delay, Language impairment, Microduplication 15q11.2 BP1–BP2, Variable penetrance

Rare or sporadic conditions involving language deficits and resulting from chromosomal rearrangement or copy number variation (CNV) provide crucial evidence of the genetic underpinnings of the human faculty of language. The BP1-BP2 region at 15q11.2 is commonly found duplicated or deleted in patients referred for microarray analysis. CNV of this region usually results in developmental delay, intellectual disability, speech and language delay, behavioral disturbance, and motor delay, but also in neuropsychiatric conditions such as autism and schizophrenia; dysmorphic features and epilepsy are also reported [Burnside et al., 2011; Abdelmoity et al., 2012; Cafferkey et al., 2014; Cox and Butler, 2015; Picinelli et al., 2016]. Changes in the BP1-BP2 region have been claimed to increase the predisposition to language delay in type I deletion subjects with Angelman syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome [Burnside et al., 2011], 2 conditions resulting from the deletion of the BP1-BP3 (type I) or the BP2-BP3 (type II) regions at 15q11.2. Deletions and duplications of the BP1-BP2 region are equally common, but apparently, deletions impact more than duplications on cognitive development and language acquisition [Burnside et al., 2011]. At the same time, variable penetrance of this CNV is commonly reported [for discussion, see Hashemi et al., 2015; Vanlerberghe et al., 2015]. As noted by many authors [e.g., De Wolf et al., 2013], studies on how the deletion or the duplication of this region is transmitted over generations may help to understand this heterogeneity. Likewise, we still lack an in-depth account of language deficits and language development in people affected by CNV of the BP1-BP2 region.

In this study, we report on 3 twin children who bear a duplication of the BP1-BP2 region transmitted by their father, providing a detailed characterization of their linguistic phenotype. Interestingly, the 2 monozygotic twins (MT1 and MT2) present with severe language delay, motor problems, and behavioral disturbances, including autistic features, whereas the fraternal twin (FT) and the father show a milder phenotype with no major impairment.

Methods

Cognitive, Linguistic, and Behavioral Evaluation

Global development of the 3 children was assessed with the Spanish version of the Battelle Developmental Inventories [De la Cruz LÓpez and González Criado, 2011]. This test comprises 341 items and includes specific subtests for evaluating receptive and expressive communication skills, gross and fine motor skills, cognitive development, personal/social development, and adaptive abilities.

Autistic features in MT1 and MT2 were assessed with the Spanish version of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) [Robins et al., 2001]. M-CHAT is a screening tool (not a diagnostic tool) for toddlers between 18 and 60 months. It comprises 23 questions. A positive score is indicative of the possibility of suffering from the disease.

Psycholinguistic development of FT was assessed in more detail with the Spanish version of the Illinois Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities (ITPA) [Ballesteros and Cordero, 2004]. This test is aimed to evaluate the child's abilities in 2 different channels of communication (auditive-vocal and visuo-motor), 2 levels of organization (automatic and representative), and 3 psycholinguistic processes (receptive, associative, and expressive). Items are organized in 13 subtests: Auditory Reception (AR), Visual Reception (VR), Auditory Sequential Memory (ASM), Visual Sequential Memory (VSM), Auditory Association (AA), Visual Association (VA), Auditory Closure (AC), Visual Closure (VC), Manual Expression (ME), Verbal Expression (VE), Grammatical Closure (GC), and Sounds Combination (SC). Because of the severity of their cognitive impairment, this test could not be applied to MT1 and MT2.

The verbal abilities of FT were also assessed with the verbal component of the Spanish version of WISC-IV [Wechsler, 2005], whereas the Spanish version of WAIS-III [Wechsler, 1999] was used to evaluate the parents' verbal performance. This component of the test comprises 6 tasks aimed to evaluate 2 different domains of language processing: verbal comprehension (Similarities [S], Vocabulary [V], Information [I], and Comprehension [CO]) and working memory (Digits [D] and Arithmetic [A]).

Molecular Cytogenetic Analysis

Karyotype Analysis

Peripheral venous blood lymphocytes were grown following standard protocols and collected after 72 h. A moderate resolution G-band karyotyping (550 bands) by trypsin (Gibco 1X trypsin® and Leishmann stain) was subsequently performed. Microscopic analysis was done with a Nikon® eclipse 50i optical microscope and the IKAROS karyotyping system (MetaSystem® software).

Angelman Syndrome Determinants

FISH with the LSI Prader-Willi/Angelman probes (15q11q13 SNPRN and 15q11q13 D15S10 Izasa®) was conducted to detect microdeletions in the 15q11q13 locus and/or in UBE3A, located in 15q11.2. Metaphase spreads were harvested from peripheral blood as above. Slides were analyzed with a Nikon eclipse 50i optical microscope and the Metasystem ISIS® software.

Multiplex Ligation-Dependent Probe Amplification

MLPA was performed to detect abnormal CNVs in the subtelomeric regions of the probands' chromosomes. The SALSA MLPA kits P036 and P070 from MRC-Holland were used according to the instructions provided by the supplier.

Microrrays for CNV Search and Chromosome Aberration Analysis

DNA samples (total amount: 500 ng) extracted from blood were hybridized on a CGH platform (Cytochip Oligo ISCA 60K). The DLRS value was >0.10. The platform included 60,000 probes. Data were analyzed with Agilent Genomic Workbench 7.0 and the ADM-2 algorithm (threshold = 6.0; aberrant regions had more than 5 consecutive probes).

Results

Clinical History

The probands are 3 twin brothers (1 fraternal twin and 2 monozygotic twins) resulting from in vitro fertilization and born after 35 weeks of normal gestation by cesarean section to a healthy 31-year-old female. The most relevant clinical data at birth are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary table with the most relevant clinical findings at birth

| MT1 | MT2 | FT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth order | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Weight | 1,870 g (3rd percentile) | 1,805 g (3rd percentile) | 2,080 g (10th percentile) |

| Height | 44 cm (25th percentile) | 45 cm (25th percentile) | 46 cm (50th percentile) |

| Cephalic perimeter | 30 cm (50th percentile) | 30.5 cm (50th percentile) | 32 cm (50th percentile) |

| Apgar score (1 min) | 9 | 8 | 7 |

| Apgar score (5 min) | 10 | 9 | 9 |

| Clinical diagnosis at birth | preterm child, respiratory distress, multifactorial jaundice | preterm child, multifactorial jaundice | preterm child, multifactorial jaundice |

| Days of incubation | 22 | 17 | 13 |

MT1, monozygotic twin 1; MT2, monozygotic twin 2; FT, fraternal twin.

The newborns were kept in an incubator between 2 and 3 weeks. No relevant clinical problems were observed during this period (Table 1). Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of MT1 and MT2, performed at 2 years/11 months, yielded normal results. No MRI was performed on FT. At the age of 4 years/3 months, both MT1 and MT2 were diagnosed with mild transmission hypoacusia (affecting the left ear in MT1 and both ears in MT2). No hearing problem was observed in FT.

Language and Cognitive Development

Early developmental milestones were achieved normally by all 3 children, including head control and the ability to sit without aid and to walk. Nonetheless, their parents and pediatricians soon reported significant developmental differences between MT1 and MT2, and FT, including absence of speech, lack of interest in the social environment, and motor disturbances. Differences were prominent at 7 years/8 months, when the global development of the 3 siblings was compared using the Spanish version of the Battelle Developmental Inventories (Fig. 1). Below we provide a detailed report of the cognitive and linguistic profiles of the 3 children.

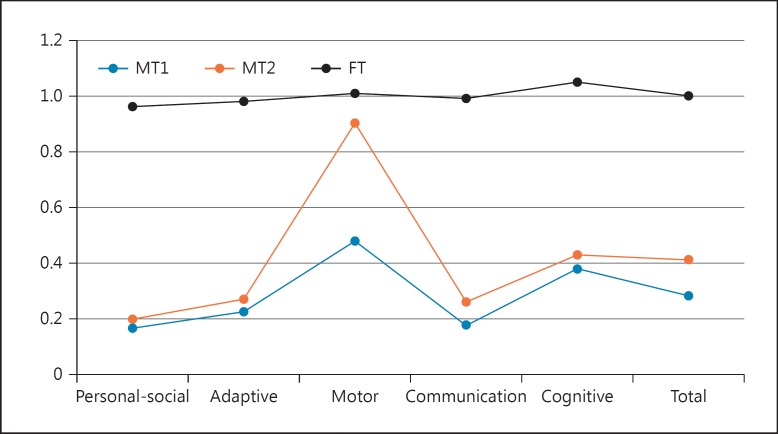

Fig. 1.

A comparison of the probands' developmental profiles at the age of 7 years/8 months according to the Battelle Developmental Inventories. In order to make more reliable comparisons, the resulting scores are shown as relative values referred to the expected scores according to the chronological age of the child. FT, fraternal twin; MT1, monozygotic twin 1; MT2, monozygotic twin 2.

Monozygotic Twins

Subsequent developmental stages were achieved later by MT1 and MT2. At 2 years/11 months, both children exhibited lack of sustained attention and motor disturbances. Language was substantially delayed to the extent that they only uttered bi-syllabic babbling with no evident communicative intention. The 2 boys only interacted with their closest relatives. They were diagnosed with lack of attention, restlessness, and language delay according to the 9th edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-9).

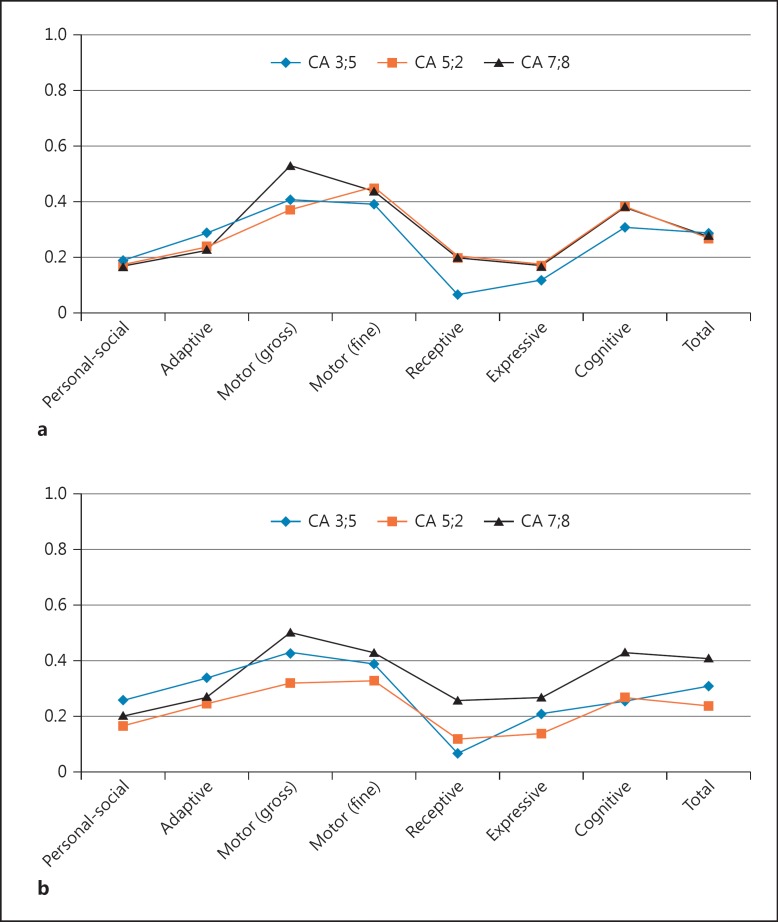

In order to follow up their global development in detail, the Spanish version of the Battelle Developmental Inventories was administered at ages 3 years/5 months, 5 years/2 months, and 7 years/8 months. The resulting scores were suggestive of a broad developmental delay (which was not ameliorated or exacerbated over the years) impacting mostly on their language abilities. Accordingly, communication skills were severely impaired; cognitive, personal-social, and adaptive abilities were impaired, and motor skills were the least-affected area (Fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 2.

Changes in the developmental profiles of the monozygotic twins 1 (a) and 2 (b) from 3 years/5 months to 7 years/ 8 months according to the Battelle Developmental Inventories. In order to make more reliable comparisons, the resulting scores are shown as relative values referred to the expected scores according to the chronological age of the child. CA, chronological age.

At 3 years/5 months, repetitive behavior was observed in both children. Although the screening with M-CHAT yielded a positive score, both MT1 and MT2 were reported to interact normally between themselves and with their parents, although they did not interact with other peers or adults. Gaze following was observed, and no obsessive or stereotyped behaviors were reported. In turn, cognitive abilities were found to be severely impaired. Although the children were able to recognize aspects of their surroundings, such as common foods, they were unable to discriminate among colors, sounds, or tactile sensations. Basic concepts, e.g., “small/big” or “inside/outside,” had not been acquired yet. Language development was seriously delayed. Bi-syllabic babbling was still observed, and the children were unable to utter single words. Comprehension was severely impaired to the extent that they barely understood their own names. Indexical pointing was still absent. Their diagnosis according to the ICD-10 was severe mental delay (F.72). In turn, the children's motor abilities were quite spared, and they were able to run, jump, throw, and move their arms and legs (still, grasping was absent).

From 3 years/2 months, both children started to attend a general education unit and also to receive speech therapy 4 times a week following an Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) paradigm [Baer et al., 1968; Sulzer-Azaroff and Mayer, 1991]. No major changes at the cognitive, language, and behavioral levels were observed from ages 3 to 4 years. At the age of 4, both twins were moved to a special education unit at the general school. At that time, language was still severely delayed. Communicative intentionality was not observed yet. They were unable to attend verbal commands. Speech therapy was also provided at school.

At age 5, stereotyped behavior and restricted interests were observed, supporting the presence of autism. Self-stimulatory behavior was also reported as well as lack of sustained attention and motor hyperactivity. Regarding their communicative abilities, auxiliary gestures were not observed and both children were still unable to understand verbal cues or instructions. Their diagnosis according to the ICD-10 was autism spectrum disorder (F.84.1) and severe mental delay (F.72).

At 6 years of age, intentionality was observed in some verbal interactions and both children seemed to understand simple verbal commands. Deictic indexing was also reported. In order to improve their verbal abilities, the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) [Bondy and Frost, 1998] was introduced by the speech therapist at school. This is an augmentative system intended to provide the child with a self-initiating, functional communication system. The system makes use of simple icons that are arranged in “sentence” structures, with a focus on requesting instead of responding or commenting. Both children started to use single words for requesting, although some differences between MT1 and MT2 were observed. Accordingly, MT1 only completed the phase 2 of PECS (Expanding Spontaneity), while MT2 was able to complete the phase 3 (Picture Discrimination). Some differences were also observed in their behavior. Accordingly, MT1 was more defiant, but less aggressive than MT2; self-hurting was reported in MT2 only.

From the age of 7, some regression was observed in both children at the behavioral level with an impact on their language abilities. Stereotypies and restricted interests as well as aggressive behavior were reported in MT1, whereas inattention problems were observed in MT2. At present, both twins have been moved to a specialized school for disabled children.

Fraternal Twin

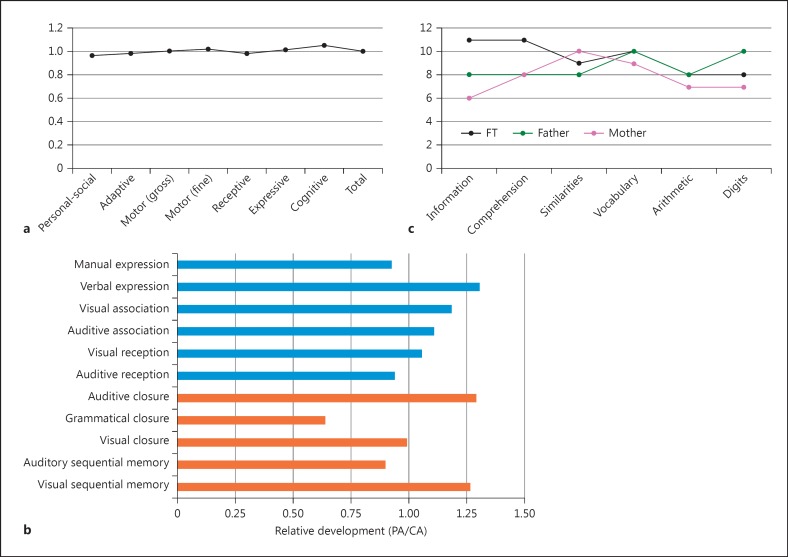

Early in childhood, the parents reported a language delay, particularly in the expressive domain, and the child received speech therapy until age 4 to improve verbal expression, speech fluency, and articulation. At 3 years of age, he commenced attending a general school. At that time, his speech was impaired, and he suffered from articulatory problems and apraxia. The child employed an unintelligible jargon with his peers and seemed unable to understand simple commands, which suggests that he also suffered from some deficit in comprehension. Nonetheless, these problems disappeared with time, and evidence of language delay was not observed from age 5 onwards. Also, no delays or deficits were reported regarding his broad cognitive development and the achievement of instrumental abilities. In order to evaluate his global development in detail, the Spanish version of the Battelle Developmental Inventories was administered at 7 years/8 months. The proband scored as typically developing children in all domains (Fig. 3a). Psycholinguistic development was assessed in more detail with the Spanish version of the Illinois Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities (ITPA) and with the verbal component of the Spanish version of the WISC-IV. In the ITPA, the child scored 306, showing a composite psycholinguistic age of 9 years/1 month, well above his chronological age. However, his profile was quite irregular, with marked strengths and weaknesses, particularly in the automatic domain, in which he scored the lowest in the grammar closure test, which evaluates the ability to add missing grammatical components to a given sentence (Fig. 3b). In the WISC-IV, the proband scored 10 in the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI), with lower scores in Similarities and higher scores in Comprehension and Information (Fig. 3c). His global score was similar to the scores achieved by his parents in the Intellectual Verbal Index of the WAIS-III, although the latter scored lower at the Comprehension and the Information components. All of them scored similarly in the tasks evaluating working memory (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Developmental profile and language abilities of the fraternal twin at 7 years/8 months. a Developmental profile according to the Battelle Developmental Inventories. b Developmental profile according to the Illinois Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities. c Developmental profile according to the verbal component of the WISC-IV (for comparison, the figure includes the parents' profiles according to the verbal component of the WAIS-III). CA, chronological age; PA, psychological age.

Molecular Cytogenetic Analysis

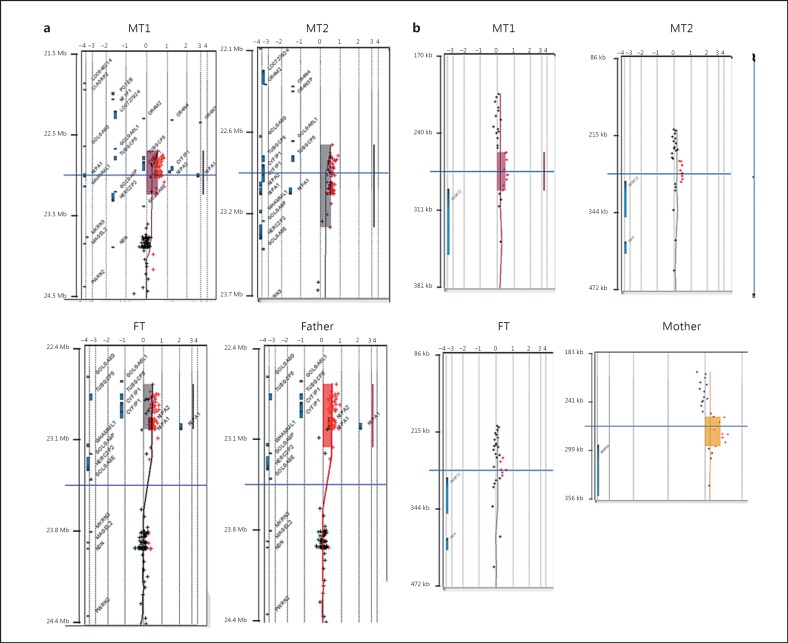

Routine molecular cytogenetic analyses of the 3 children were performed at age 3. FISH analyses of the loci of SNRPN and UBE3A (2 main determinants of Angelmansyndrome) were normal. No major chromosomal rearrangements were observed in the karyotype analysis. At 5 years/7 months, an MLPA of the subtelomeric regions of all chromosomes was performed. A deletion in 4q35.2 affecting FRG1 was then reported, but this was not confirmed later by FISH when using a 4qter subtelomeric probe. In order to discard the presence of low-frequency mosaicisms and/or cryptic chromosomal alterations, an array CGH was performed. The array discarded the deletion in chromosome 4, but identified a duplication in the 15q11.2 region in all 3 children that was inherited from the father (Fig. 4a; Table 2). Differences in the predicted size of the duplicated fragments are expected to result from differences in the intensity of the signals, considering that the 4 probes exhibit similar profiles (Fig. 4a). The duplicated region corresponds to the BP1-BP2 region in 15q11.2, which encompasses the genes TUBGCP5, CYFIP1, NIPA2, and NIPA1. The 3 children also bear a microduplication in 6p25.3, which affects the promoter and part of the first exon of DUSP22 and was inherited from the mother (Fig. 4b; Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Array CGH and duplicated genes in the probands. a Array CGH of the probands' chromosome 15 showing a microduplication at 15q11.2. b Array CGH of the probands' chromosome 6 showing a microduplication at 6p25.3.

Table 2.

Summary table with the CNVs found in the probands

| Predicted coordinates (hg19) | Expected coordinates (hg38) | Expected affected genes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duplication in 15q11.2 | |||

| MT1 | chr15:22,765,628–23,300,287 | chr15:22,693,148–23,088,545 | TUBGCP5, CYFIP1, NIPA2, NIPA1 |

| MT2 | chr15:22,765,628–23,300,287 | chr15:22,693,148–23,088,545 | TUBGCP5, CYFIP1, NIPA2, NIPA1 |

| FT | chr15:22,765,628–23,085,096 | chr15:22,693,148–23,088,545 | TUBGCP5, CYFIP1, NIPA2, NIPA1 |

| Father | chr15:22,765,628–23,217,514 | chr15:22,693,148–23,088,545 | TUBGCP5, CYFIP1, NIPA2, NIPA1 |

| Duplication in 6p25.3 | |||

| MT1 | chr6:259,318–293,615 | chr6:259,318–293,615 | DUSP22 |

| MT2 | chr6:259,318–293,615 | chr6:259,318–293,615 | DUSP22 |

| FT | not available due to low signal | chr6:259,318–293,615 | DUSP22 |

| Mother | chr6:259,318–293,615 | chr6:259,318–293,615 | DUSP22 |

MT1, monozygotic twin 1; MT2, monozygotic twin 2; FT, fraternal twin.

Discussion

In this study, we characterized in detail the linguistic and cognitive profile of a family (the father and 3 male siblings) bearing a duplication of the BP1-BP2 region in 15q11.2. Two of the children are monozygotic twins who exhibit most of the features commonly associated with this duplication (Table 3). The father and the FT are phenotypically normal carriers, although the FT exhibited some language delay in early infancy which resolved with time. This outcome can be explained in terms of reduced penetrance or altered gene dosage on a particular genetic background, as reported in some cases [Burnside et al., 2011]. Another possibility is that a protective allele in the father has been transmitted to FT only, but not to MT1 and MT2, as suggested in other cases [Lee et al., 2015].

Table 3.

Summary table with the clinical findings of the probands compared to those described in other patients bearing the duplication of the BP1–BP2 region

| MT1 | MT2 | FT | Father Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysmorphic features | 0/3 | 22/49 | 0/5 | |||

| Developmental delay | + | + | 2/3 | 19/49 | 5/5 | |

| Motor delay | 1/3 | 13/49 | 4/5 | |||

| Speech delay | + | + | +c | 1/3 | 22/44 | 5/5 |

| Autism/autistic features/Asperger | + | + | 3/3 | 18/44 | 3/5 | |

| ADD/ADHD | + | + | 0/3 | 18/44 | 2/5 | |

| OCD/ODD, self-injury, tantrums, etc. | +a | +b | 1/3 | 10/44 | 2/5 | |

| Other neurological problems (insomnia, personality issues, abnormal brain MRI or EEG, etc.) | 0/3 | 14/49 | 2/5 | |||

| Hypotonia | 0/3 | 7/49 | 1/5 | |||

| Ataxia/gait/balance/dyspraxia issues | +d | 0/3 | 11/44 | 1/5 | ||

| Seizures | 0/3 | 6/49 | 0/5 |

ADD/ADHD, attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; OCD/ODD, obsessive-compulsive disorder/oppositional defiant disorder; FT, fraternal twin; MT1, monozygotic twin 1; MT2, monozygotic twin 2; +, present.

Defiant and aggressive behavior, but reduced impulsivity.

Severe self-injury behavior.

Resolved later in life.

The core BP1-BP2 region contains 4 genes (TUBGCP5, CYFIP1, NIPA2, and NIPA1) involved in behavioral and neurological functions, which are expressed biallelically [Chai et al., 2003]. As reviewed by Picinelli et al. [2016], TUBGCP5 has been related to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder; CYFIP1 encodes a protein that interacts with FMRP, the main determinant for fragile X mental retardation syndrome, and NIPA1 has been linked to autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia. No patient bearing a single duplication of any of these genes is found in the DECIPHER database. Nonetheless, stronger links between some of these genes and language (dis)abilities are expected to exist. Accordingly, a common variant of CYFIP1 has been recently associated with interindividual variation in the surface area across the left supramarginal gyrus, a brain area involved in language processing, and the gene is predicted to be regulated by FOXP2, a well-known gene important for speech and language [Woo et al., 2016].

All 3 children in our study also bear a partial duplication of the DUSP22 gene, involving the proximal part of the promoter and the first exon, which is also found in their mother. This duplication has been reported as common polymorphism in the normal population but may underlie differential susceptibility to disease [see Iafrate et al., 2004, suppl. Table 1]. DUSP22 encodes a dual specificity phosphatase involved in cell death [Ju et al., 2016]. Similar duplications are reported as of unknown pathogenicity in DECIPHER (patient 250238), whereas deletions affecting the same region are reported as likely benign (patient 286128) or of unknown pathogenicity (patient 250711). CNVs affecting the promoter of the gene only have been found in individuals with intellectual disability (DECIPHER patients 1566 [duplication] and 652 [deletion]). Interestingly, the promoter of DUSP22 has been found hypermethylated in the hippocampus of patients with Alzheimer disease, and the DUSP22 protein seemingly contributes to determine the TAU phosphorylation status and CREB signaling [Sánchez-Mut et al., 2014]. The DECIPHER database shows that duplications of the whole DUSP22 gene are less frequently found than deletions, which usually entail more severe developmental problems, including autism [Leblond et al., 2012]. Speech and language delay is only reported in patients with deletions affecting the downstream genes (DECIPHER patients 249742 or 273907). Because of the normal phenotype of the mother, we expect that the deficits observed in the 2 affected children result from the duplication of the BP1-BP2 region in 15q11.2. Nonetheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that a change in the amount of DUSP22 due to the partial duplication of the gene contributes to the language deficits found in the 3 siblings at the initial stages of development, considering that the mother scored below the mean in the tasks evaluating verbal comprehension.

Conclusions

Although the exact genetic cause of the language and cognitive impairment exhibited by 2 of our probands remains to be fully elucidated, we believe that the duplication of the genes in 15q11.2 discussed above may explain most of their deficits and clinical problems. Comparisons with the genetic background of their unaffected brother and father will help clarify the variable manifestation of the duplication of this region. We expect that this familiar case further contributes to a better understanding of the genetic underpinnings of the human faculty for language.

Statement of Ethics

Ethics approval for this research was granted by the Comité Ético del Hospital Universitario “Reina Sofía.” Written informed consent was obtained from the probands' parents for publication of this case report and any accompanying tables and images.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the probands and their family for their participation in this research. We also wish to thank Luis Antonio Alcaraz Mas, from Bioarray (http://www.bioarray.es/es), for his technical aid with the microarray analyses. This study was supported in part by funds from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grants FFI2014-61888-EXP and FFI2016-78034-C2-2-P to A.B.-B.).

References

- Abdelmoity AT, LePichon JB, Nyp SS, Soden SE, Daniel CA, Yu S. 15q11.2 proximal imbalances associated with a diverse array of neuropsychiatric disorders and mild dysmorphic features. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33:570–576. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31826052ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer D, Wolf M, Risley R. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. J Appl Behav Anal. 1968;1:91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros S, Cordero A. ITPA: Test Illinois de Aptitudes Psicolingüísticas. Madrid: TEA Ediciones; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bondy AS, Frost LA. The picture exchange communication system. Semin Speech Lang. 1998;19:373–388. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1064055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnside RD, Pasion R, Mikhail FM, Carroll AJ, Robin NH, et al. Microdeletion/microduplication of proximal 15q11.2 between BP1 and BP2: a susceptibility region for neurological dysfunction including developmental and language delay. Hum Genet. 2011;130:517–528. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0970-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferkey M, Ahn JW, Flinter F, Ogilvie C. Phenotypic features in patients with 15q11.2(BP1-BP2) deletion: further delineation of an emerging syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:1916–1922. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai JH, Locke DP, Greally JM, Knoll JH, Ohta T, et al. Identification of four highly conserved genes between breakpoint hotspots BP1 and BP2 of the Prader-Willi/Angelman syndromes deletion region that have undergone evolutionary transposition mediated by flanking duplicons. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:898–925. doi: 10.1086/378816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DM, Butler MG. The 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 microdeletion syndrome: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:4068–4082. doi: 10.3390/ijms16024068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz López MV, González Criado M. Adaptación española del inventario de Desarrollo Battelle. Madrid: TEA Ediciones; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Wolf V, Brison N, Devriendt K, Peeters H. Genetic counseling for susceptibility loci and neurodevelopmental disorders: the del15q11.2 as an example. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:2846–2854. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi B, Bassett A, Chitayat D, Chong K, Feldman M, et al. Deletion of 15q11.2(BP1-BP2) region: further evidence for lack of phenotypic specificity in a pediatric population. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A:2098–2102. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, Listewnik ML, Donahoe PK, et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:949–951. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju A, Cho YC, Kim BR, Park SG, Kim JH, et al. Scaffold role of DUSP22 in ASK1-MKK7-JNK signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164259. e0164259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblond CS, Heinrich J, Delorme R, Proepper C, Betancur C, et al. Genetic and functional analyses of SHANK2 mutations suggest a multiple hit model of autism spectrum disorders. PLoS Genet. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002521. e1002521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IS, Carvalho CM, Douvaras P, Ho SM, Hartley BJ, et al. Characterization of molecular and cellular phenotypes associated with a heterozygous CNTNAP2 deletion using patient-derived hiPSC neural cells. NPJ Schizophr. 2015;1:15019. doi: 10.1038/npjschz.2015.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picinelli C, Lintas C, Piras IS, Gabriele S, Sacco R, et al. Recurrent 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 microdeletions and microduplications in the etiology of neurodevelopmental disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2016;171:1088–1098. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins DL, Fein D, Barton ML, Green JA. The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers: an initial study investigating the early detection of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:131–144. doi: 10.1023/a:1010738829569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Mut JV, Aso E, Heyn H, Matsuda T, Bock C, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of the phosphatase DUSP22 mediates PKA- dependent TAU phosphorylation and CREB activation in Alzheimer's disease. Hippocampus. 2014;24:363–368. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer-Azaroff B, Mayer R. Behavior Analysis for Lasting Change. Fort Worth: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwaag B, Staal WG, Hochstenbach R, Poot M, Spierenburg HA, et al. A co-segregating microduplication of chromosome 15q11.2 pinpoints two risk genes for autism spectrum disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B:960–966. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanlerberghe C, Petit F, Malan V, Vincent-Delorme C, Bouquillon S, et al. 15q11.2 microdeletion (BP1-BP2) and developmental delay, behaviour issues, epilepsy and congenital heart disease: a series of 52 patients. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WAIS-III. Escala de inteligencia de Wechsler para adultos-III. Madrid: TEA Ediciones; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Escala de Inteligencia de Wechsler para niños-WISC-IV. Madrid: Pearson Educación; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Woo YJ, Wang T, Guadalupe T, Nebel RA, Vino A, et al. A common CYFIP1 variant at the 15q11.2 disease locus is associated with structural variation at the language-related left supramarginal gyrus. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158036. e0158036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]