Abstract

Since the prognosis of advanced biliary tract cancer (aBTC) still remains very poor, new therapeutic approaches, including immunotherapies, need to be developed. In the current study, we conducted an open‐label randomized phase II study to test whether low dose cyclophosphamide (CPA) could improve antigen‐specific immune responses and clinical efficacy of personalized peptide vaccination (PPV) in 49 previously treated aBTC patients. Patients with aBTC refractory to at least one regimen of chemotherapies were randomly assigned to receive PPV with low dose CPA (100 mg/day for 7 days before vaccination) (PPV/CPA, n = 24) or PPV alone (n = 25). A maximum of four HLA‐matched peptides were selected based on the pre‐existing peptide‐specific IgG responses, followed by subcutaneous administration. T cell responses to the vaccinated peptides in the PPV/CPA arm tended to be greater than those in the PPV alone arm. The PPV/CPA arm showed significantly better progression‐free survival (median time: 6.1 vs 2.9 months; hazard ratio (HR): 0.427; P = 0.008) and overall survival (median time: 12.1 vs 5.9 months; HR: 0.376; P = 0.004), compared to the PPV alone arm. The PPV alone arm, but not the PPV/CPA arm, showed significant increase in plasma IL‐6 after vaccinations, which might be associated with inhibition of antigen‐specific T cell responses. These results suggested that combined treatment with low dose CPA could provide clinical benefits in aBTC patients under PPV, possibly through prevention of IL‐6‐mediated immune suppression. Further clinical studies would be recommended to clarify the clinical efficacy of PPV/CPA in aBTC patients.

Keywords: Biliary tract cancer, cyclophosphamide, IL‐6, peptide vaccine, randomized phase II clinical trial

Recent advances in cancer immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, have shown some durable clinical responses in patients with various types of advanced cancers.1, 2 However, since their clinical efficacy has still been limited, new immunotherapeutic approaches to increase tumor‐specific T cells remain to be developed. We have developed a novel immunotherapeutic strategy, personalized peptide vaccination (PPV), in which a maximum of four human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I‐matched peptides for vaccination are selected from candidate antigen peptides on the basis of both HLA class I type and pre‐existing peptide‐specific immune responses.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Recent clinical trials of PPV have demonstrated significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced cancers, including prostate and bladder cancers, through induction of antigen‐specific T cells.7, 8, 9 However, we previously reported limited clinical benefit in a trial of PPV for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer (aBTC). In that trial, aBTC patients with higher interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) values before and after PPV showed worse clinical outcomes.4

Cyclophosphamide (CPA), an alkylating cytotoxic agent, has been well known to show immunomodulatory properties, such as suppression of regulatory T cells (Treg) and modulation of antigen‐specific T cells responses and dentritic cell homeostasis, depending on dose, timing, and sequence of administration.11, 12, 13, 14 Large numbers of clinical studies of cancer immunotherapies combined with CPA were conducted in the past decades, but the effects of CPA on either T cell boosting or clinical benefits have been controversial.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 We conducted an open‐label randomized phase II study to test if combination of low dose CPA could improve the PPV‐induced immune responses and clinical efficacy in previously treated aBTC patients, who has been shown to have a poor prognosis with median survival time (MST) of <9 months in most reports.19, 20, 21

Materials and Methods

Patient selection

Eligible patients should be at least 20 years old with histologically confirmed aBTC and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) 0 or 1. All patients were refractory to at least one regimen of standard chemotherapies. The other inclusion criteria included life expectancy of at least 12 weeks, adequate bone marrow, hepatic, and renal functions, positive status for HLA‐A2, ‐A24, ‐A3 supertype (‐A3, ‐A11, ‐A31 and ‐A33) or ‐A26, and positive immunoglobulin G (IgG) responses to at least two of the 31 different candidate peptides (Table S1), as reported previously.3, 4, 5, 9, 10 Exclusion criteria included an acute infection, a history of severe allergic reaction, pulmonary, cardiac or other systemic diseases, and other inappropriate conditions for enrollment as judged by clinicians.

The study was compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization of Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and was conducted in an outpatient setting at the Cancer Vaccine Center of Kurume University in Japan. The protocol was approved by Kurume University Ethical Committees (# 11086). All patients provided written informed consent before participating in this study.

Study design and treatment

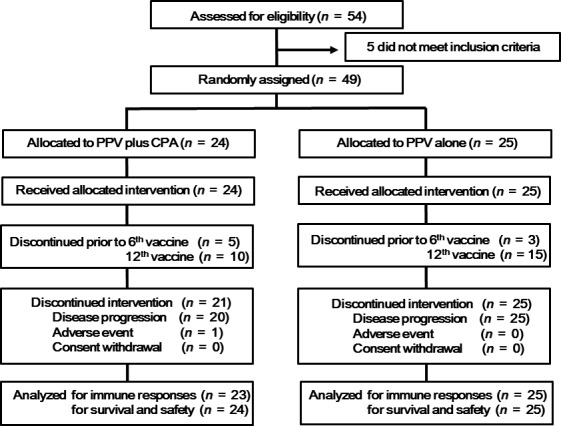

This was an open‐label, randomized phase II trial of PPV plus low‐dose CPA (PPV/CPA, study arm) and PPV alone (control arm) for aBTC patients who had previously treated with at least one regimen of chemotherapies (clinical trial registration number, UMIN000006249). Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either PPV/CPA or PPV alone, using a minimization technique with the following stratification factors: PS (0 or 1) and clinical stage (IV or recurrence) (Fig. 1). Since the frequency of aBTC had been relatively low in Japan, the number of patents in each arm was determined as 25 to increase the possibility of successful completion of this phase II trial. The primary endpoint was to evaluate the antigen‐specific immune responses and inhibitory immune cell subsets in peripheral blood, and the secondary endpoints were progression‐free survival (PFS), OS, and safety.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

For PPV treatment, two to four peptides were selected every cycle of six vaccinations by the levels of IgG titers specific to HLA‐matched 31 candidate peptides (Table S1).3, 4, 5, 9, 10 Each of the selected peptides was mixed with incomplete Freund's adjuvant (Montanide ISA‐51VG; Seppic, Paris, France) and injected subcutaneously into the inguinal, abdominal, or lateral thigh areas as 1.5 mL emulsion (3 mg/each peptide). All peptides were prepared under conditions of Good Manufacturing Practice using a Multiple Peptide System (San Diego, CA, USA). Patients received six times of PPV at 1 week intervals (the first cycle) and six times at 2‐week intervals (the second cycle and thereafter) until withdrawal of consent or unacceptable toxicity. In the PPV/CPA arm, patients were administered orally with 100 mg of CPA (50 mg × 2/day) for 7 days followed by the first cycle of vaccinations, and also for 7 days followed by the second cycle of vaccinations. This dose and schedule of CPA was determined by referring and following the previously published paper, which showed that the same dose of CPA [100 mg of CPA (50 mg × 2/day) orally for 7 days] significantly reduced both number and suppressive function of regulatory T cells, whereas a twice higher dose of CPA (200 mg per day instead of 100 mg per day) decreased not only regulatory T cells but also all lymphocyte subpopulations.22 The combined treatment with chemotherapeutic drugs (gemcitabine, 5‐FU, S‐1, or CDDP) was allowed throughout the study period and also thereafter.

CT scans were examined every 2 months for efficacy assessment by the RECIST criteria. PFS was defined as the time from the first day of peptide vaccination until objective disease progression or death, whichever occurred first. OS was calculated as the time from the first day of peptide vaccination until the date of death or the last date when the patient was known to be alive. Analyses of PFS and OS were based on a full analysis set that included all randomly assigned patients who received PPV. Safety was assessed throughout the study by monitoring adverse events (AEs), assessed according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 (NCI‐CTCAE Ver. 4.0).

Immune responses

T cell responses and IgG titers specific to the antigen peptides in peripheral blood were evaluated by interferon (IFN)‐γ ELISPOT and bead‐based multiplexed Luminex assay (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA), respectively, before and after vaccination (at the time of 6th and 12th vaccinations), as described previously.5, 9, 10 In brief, 30 mL of peripheral blood was obtained before and after vaccination, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation with Ficoll‐Paque Plus (GE Healthcare; Uppsala, Sweden). For measurement of T cell responses, PBMC (1 × 105 cells/well) were incubated in 96‐round‐well microculture plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY, USA) with 200 μL of medium (OpTmizer T Cell Expansion SFM; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% FBS (MP Biologicals, Solon, OH), IL2 (20 IU/mL; AbD serotec, Kidlington, UK), and each peptide (10 μg/mL) for 5 days. After incubation, the cells were harvested and tested for their ability to produce IFN‐γ in response to either the corresponding peptides or a negative control peptide from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) sequence. Antigen‐specific IFN‐γ secretion after 18 h of incubation was determined by the ELISPOT assay, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (MBL, Nagoya, Japan), and spots were counted by an ELISPOT reader (CTL‐immunoSpot S5 Series; Cellular Technology, Ltd, Shaker Heights, OH, USA). Antigen‐specific T‐cell responses were evaluated by the difference between the numbers of spots produced in response to each corresponding peptide and those produced in response to the control peptide.

For measurement of IgG titers, plasma was incubated with 100 μL of peptide‐coupled color‐coded beads for 1.5 h at 30°C on a plate shaker. After incubation, the mixture was washed with a vacuum manifold apparatus and incubated with 100 μL of biotinylated goat anti‐human IgG (gamma chain‐specific; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 h at 30°C. The plate was then washed, followed by the addition of 100 μL of streptavidin‐PE (Life Technologies) into wells, and was incubated for 30 min on a plate shaker. The beads were washed three times followed by the addition of 100 μL of Tween‐PBS into each well and detection of fluorescence intensity unit (FIU) on the beads using the Luminex system. The cutoff values of anti‐peptide IgG were set to 10 FIU in 100‐time diluted samples.

Inhibitory immune cells and IL‐6

Inhibitory immune cell subsets, including regulatory T cells (Treg) and myeloid‐derived suppressor cells (MDSC), in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were examined by flow cytometry before and after vaccination. For the analysis of Tregs, PBMC (0.5 × 106 cells) were stained with anti‐CD‐4, anti‐CD25, and anti‐FoxP3 antibodies (Ab) by using the One Step Staining Human Treg Flow Kit (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA). For the analysis of MDSC, PBMC (0.5 × 106 cells) were stained with the monoclonal Ab against the following antigens: CD3, CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD33, CD56, and HLA‐DR (all from Biolegend). In the cell subset negative for lineage markers (CD3, CD19, CD56, CD14) and HLA‐DR, granulocytic MDSC were identified as positive for CD33 and CD11b. Monocytic MDSC were identified as positive for CD14 and low (or negative) for HLA‐DR. The samples were run on a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), and the frequencies of Treg and MDSC were analyzed using the Diva software package (BD Biosciences). The levels of IL6 in plasma before and after vaccination were examined by ELISA using the kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Statistical methods

Time‐to‐event endpoints were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and between‐treatment comparisons for PFS and OS were conducted using the log‐rank test or the Fleming‐Harrington test. Cox proportional hazards analysis with time‐dependent variables was performed to calculate hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Welch's t‐test and the χ2 test were used to compare quantitative and categorical variables, respectively. A two‐sided significance level of 5% was considered statistically significant in all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

A total of 49 aBTC patients were randomly assigned to receive either PPV plus CPA (PPV/CPA, n = 24) or PPV alone (n = 25) between November 2011 and December 2014 (Fig. 1). Demographic and baseline disease characteristics were well balanced between both arms (Table 1). All patients enrolled in the study had failed at least one regimen of standard chemotherapies at the time of entry. Five and 10 of 24 patients in the PPV/CPA arm and three and 15 of 25 patients in the PPV alone arm dropped from the study before 6th and 12th vaccination, respectively, due to disease progression. The numbers of vaccinated peptides were four, three, and two for 23, one, and zero patients in the PPV/CPA or 23, one, and one in the PPV alone, respectively. The median numbers of vaccination were 12 (2–37) or 11 times (3–23) in the PPV/CPA or PPV alone, respectively. The combined chemotherapies were gemcitabine (GEM) for four and four, S‐1 or 5‐FU for 10 and eight, GEM and S‐1 for three and seven, GEM and CDDP for five and six, or none for three and one patients with the PPV/CPA and PPV alone, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the enrolled patients

| PPV + CPA (n = 24) | PPV alone (n = 25) | P‐valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (range) | 62.5 (52–77) | 63 (55–77) | 0.67 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 14 | 18 | 0.38 |

| Female | 10 | 7 | |

| Performance status | |||

| 0 | 20 | 19 | 0.73 |

| 1 | 4 | 6 | |

| HLA type | |||

| A24 | 17 | 15 | 0.56 |

| A2 | 10 | 11 | |

| A3 supertype | 12 | 11 | |

| A26 | 4 | 9 | |

| Clinical stage | |||

| IV | 10 | 15 | 0.20 |

| Recurrence | 14 | 10 | |

| Disease type | |||

| Intrahepatic | 13 | 10 | 0.69 |

| Extrahepatic | 4 | 5 | |

| Gallbladder | 4 | 4 | |

| Ampullary | 3 | 6 | |

| Number of previous chemotherapy regimens | |||

| 1 | 8 | 5 | 0.33 |

| 2 | 11 | 13 | |

| >3 | 5 | 7 | |

| CRP (mg/dL, before vaccination) | |||

| Median (range) | 0.245 (0.02–17.98) | 0.63 (0.02–8.40) | 0.79 |

| Albumin (g/dL before vaccination) | |||

| Median (range) | 4.15 (2.8–5.2) | 4.10 (2.9–4.8) | 0.96 |

| Number of vaccination | |||

| Median (range) | 12 (2–37) | 11 (3–23) | 0.08 |

| Combination chemotherapy | |||

| None | 3 | 1 | 0.52 |

| GEM | 4 | 4 | |

| S‐1 or 5‐FU | 10 | 8 | |

| GEM + S‐1 | 3 | 7 | |

| GEM + CDDP | 5 | 6 | |

P‐values were calculated by the Welch's t‐test for quantitative variables or by the χ2 test for categorical variables. CPA, cyclophosphamide; GEM, Gemcitabine; PPV, personalized peptide vaccine.

Immune responses

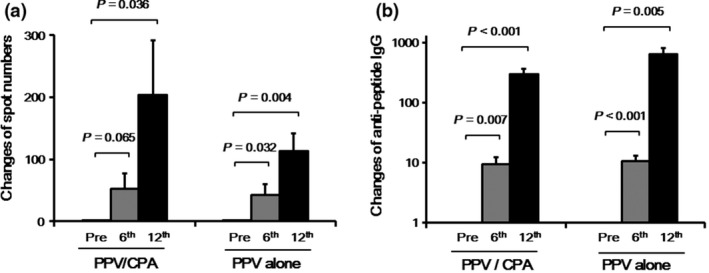

T cell responses to at least one of the vaccinated peptides were detectable in pre‐vaccination PBMC by IFN‐γ ELISPOT assay in nine of 23 or eight of 25 patients in the PPV/CPA or PPV alone, respectively (Table S2). The numbers of wells positive for IFN‐γ spots among total wells examined were 16 of 93 (17%) or 16 of 105 (15%) wells in pre‐vaccination PBMC, 23 of 78 (29%) or 20 of 93 (22%) at the 6th vaccination, and 31 of 58 (58%) or 20 of 44 (45%) at the 12th vaccination in the PPV/CPA or PPV alone, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between the two arms in the frequency of positive wells (pre‐vaccination, P = 0.7076; 6th, P = 0.2308; 12th, P = 0.4239; by χ2 test). To better understand the magnitude of PPV‐induced augmentation of T cell activity, we compared the relative changes of IFN‐γ spot numbers after PPV between the two arms. Antigen‐specific T cell responses were significantly increased after vaccination in both arms. Although not statistically significant (P = 0.334), the increase of IFN‐γ spot numbers per well in the PPV/CPA tended to be greater than that in the PPV alone at the 12th vaccination (Fig. 2a). Increase in antigen‐specific IFN‐γ spot numbers tended to be significantly correlated with better prognosis in the PPV/CPA (HR = 0.348, 95% CI = 0.119–1.015, P = 0.053), but not in the PPV alone (HR = 0.915, 95% CI = 0.331–2.535, P = 0.865).

Figure 2.

Antigen‐specific immune responses after personalized peptide vaccination (PPV). T cell and IgG responses specific to the vaccine peptides were determined by interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) ELISPOT and bead‐based multiplexed assays before and after (6th and 12th vaccination) PPV, respectively. (a) The relative changes of peptide‐specific IFN‐γ spot numbers after PPV compared to those before PPV were estimated. The spot numbers before PPV were set to 1.0. Means and standard errors are shown. (b) The relative changes of peptide‐specific IgG titers after PPV compared to those before PPV were estimated. The IgG titers before PPV were set to 1.0. Means and standard errors are shown.

Humoral immune responses before and after PPV was also evaluated by the levels of IgG to the vaccinated peptides (Table S2). The IgG levels were significantly increased after vaccination in both arms (Fig. 2b). However, there were no significant differences in peptide‐specific IgG levels before and after PPV between the two arms. The changes in antigen‐specific IgG levels were not significantly correlated with prognosis in either the PPV/CPA (HR = 1.714, 95% CI = 0.550–5.343, P = 0.353) or PPV alone (HR = 0.980, 95% CI = 0.309–3.114, P = 0.973).

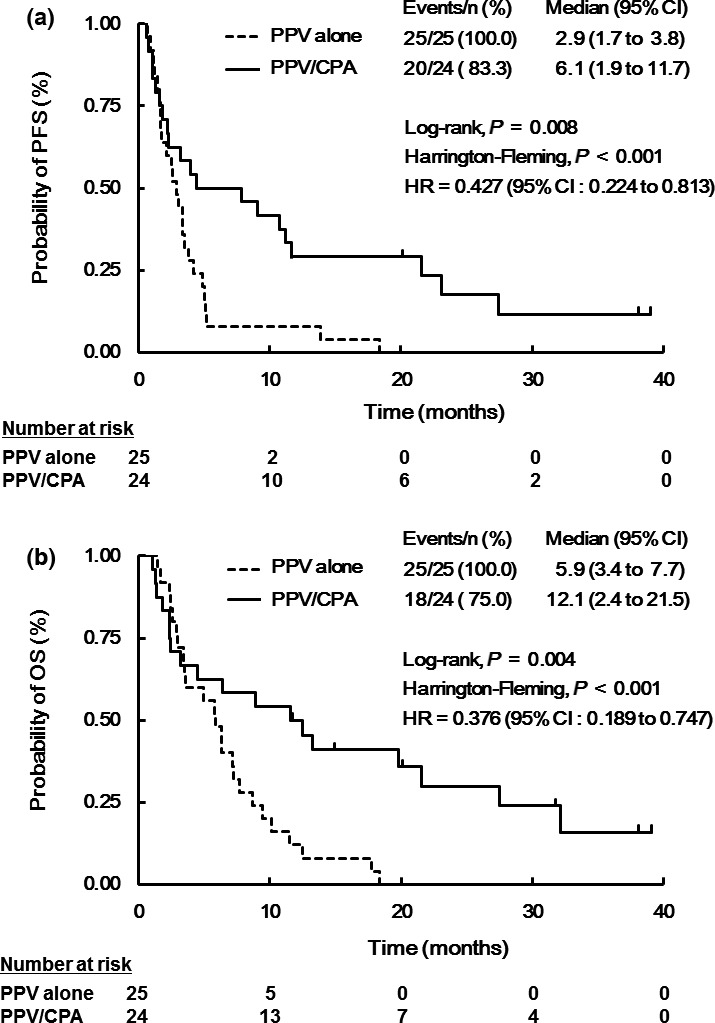

Clinical efficacy

At the data cutoff date of 10 November 2015, 43 (87.8%) of 49 patients (18 of 24 in the PPV/CPA and all 25 in the PPA alone) had died because of tumor progression. Based on the RECIST criteria, best clinical responses were two or one partial response (PR), nine or two stable disease (SD), and 12 or 22 progressive disease (PD) in the PPV/CPA or PPV alone, respectively (Table S2). Median PFS time was 6.1 or 2.9 months in the PPV/CPA or PPV alone, respectively (HR 0.427; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.224–0.813; P = 0.008 by log‐rank test and P < 0.001 by Fleming‐Harrington test) (Fig. 3a). Median OS time was 12.1 or 5.9 months in the PPV/CPA or PPV alone, respectively, and the risk of death was reduced by 62.4% in the PPV/CPA (HR, 0.376; 95% CI, 0.189–0.747; P = 0.004 by log‐rank test and P < 0.001 by Fleming‐Harrington test) (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression‐free survival (PFS) and of overall survival (OS). PFS (a) and OS (b) were evaluated by the Kaplan‐Meier method in the PPV/CPA (solid line, n = 24) and PPV alone (dotted line, n = 25). Between‐treatment comparisons for PFS and OS were conducted using the log‐rank test or the Fleming‐Harrington test.

Cox regression analysis was performed with potentially prognostic factors, including PS, clinical stage, number of previous chemotherapy regimens, combination with or without CPA, and peptide‐specific T cell responses after PPV (Table 2). Combination with CPA (HR = 0.257, 95% CI = 0.104–0.635, P = 0.003) and lower PS (HR = 2.949, 95% CI = 1.145–7.598, P = 0.025) were significantly associated with favorable OS. In addition, although not statistically significant, the increase of peptide‐specific T cell responses after vaccination tended to be also associated with favorable OS (HR = 0.548, 95% CI = 0.268–1.119, P = 0.099).

Table 2.

Cox regression analysis with time‐dependent variables for overall survival (OS)

| Factor | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|

| Performance status | 2.949 (1.145–7.598) | 0.025 |

| Clinical stage | 0.885 (0.402–1.950) | 0.762 |

| Number of previous chemotherapy regimens | 1.034 (0.622–1.719) | 0.898 |

| CPA combination | 0.257 (0.104–0.635) | 0.003 |

| Increase of T cell responses | 0.548 (0.268–1.119) | 0.099 |

CI, confidence interval; CPA, cyclophosphamide.

Safety

Adverse events due to any cause are listed in Table S3. No treatment‐related death occurred on either arm. The most frequently reported AEs in both arms were the injection site reactions (75% in the PPV/CPA and 76% in the PPV alone). Severe AEs (grade 3 or 4) except for one grade 3 skin reaction were judged to be not related to PPV by evaluation of the independent review committee.

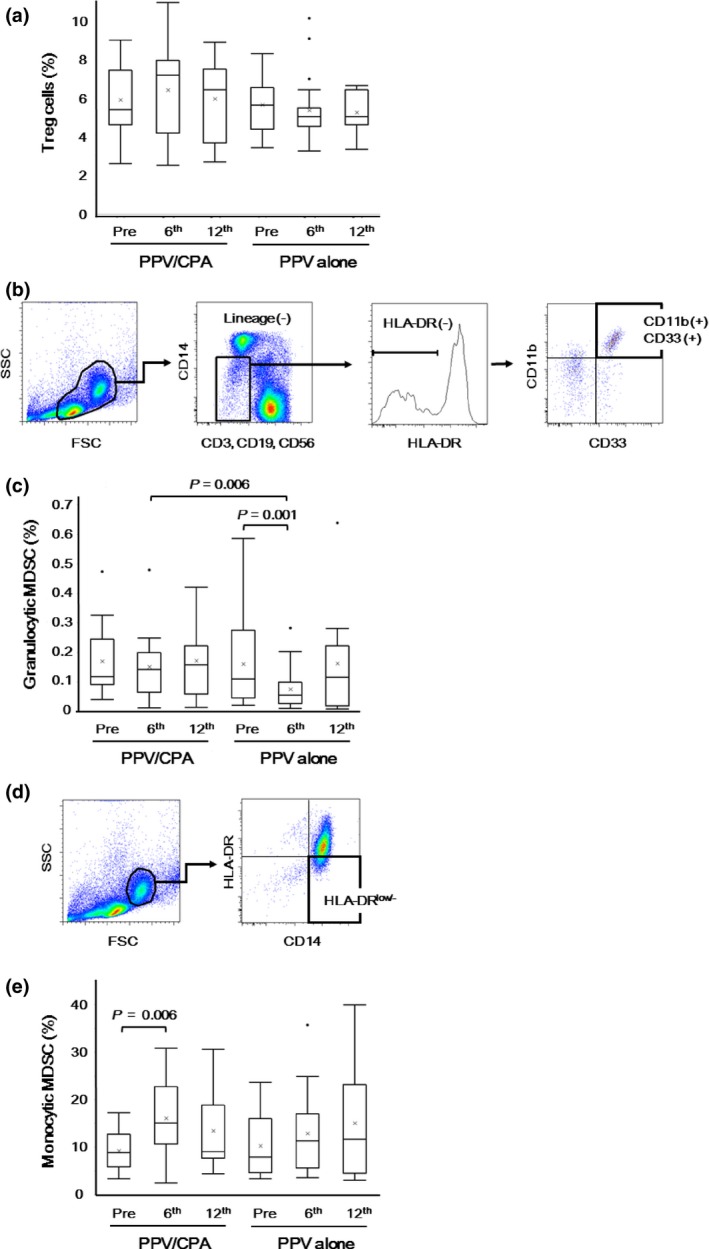

Inhibitory immune cells and IL‐6

The frequencies of inhibitory immune cells, Treg and MDSC, in PBMC were investigated before and after PPV (at the 6th or 12th vaccination). There were no significant differences in the frequency of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg between both arms before and after PPV (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

Inhibitory immune cells before and after personalized peptide vaccination (PPV). Inhibitory immune cells, including Treg cells, granulocytic myeloid‐derived suppressor cells (MDSC), and monocytic MDSC, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were examined before and after PPV (6th and 12th vaccination). (a) The percentages of Foxp3+ CD25+ cells in CD4+ cells were determined before and after PPV. (b) In the cell subset negative for lineage markers (CD3, CD19, CD56, CD14) and HLA‐DR in the lymphocyte/monocyte gate, granulocytic MDSC were identified as positive for CD33 and CD11b. (c) The percentages of CD11b+ CD33+ cells in PBMC were determined before and after PPV. (d) Monocytic MDSC were identified as positive for CD14 and low (or negative) for HLA‐DR in the monocyte gate. (e) The percentages of HLA‐DR low/− cells in CD14+ cells were determined before and after PPV. Box plots show median and interquartile range (IQR). The whiskers (vertical bars) are the lowest value within 1.5× IQR of the lower quartile and the highest value within 1.5× IQR of the upper quartile. Data not included between the whiskers were plotted as an outlier with dots. “X” shows the mean of the data.

The frequencies or absolute numbers of granulocytic MDSC (CD11b +CD33+) were evaluated before and after PPV and compared between the PPV/CPA and PPV alone arms (Fig. 4b). The frequencies of granulocytic MDSC significantly decreased at the 6th vaccination (P = 0.001) in the PPV alone, but did not change during PPV in the PPV/CPA (Fig. 4c). The absolute numbers of granulocytic MDSC significantly decreased at the 6th (P < 0.001) and 12th (P = 0.005) vaccinations in the PPV alone, but only at the 6th vaccination (P = 0.012) in the PPV/CPA (data not shown). There were significant differences in the frequencies (P = 0.006) and absolute numbers (P = 0.044) of granulocytic MDSC between both arms at the 6th vaccinations, but not at the 12th vaccinations.

The frequencies or absolute numbers of monocytic MDSC (CD14 + HLA‐DRlow/−) were also evaluated before and after PPV and compared between the PPV/CPA and PPV alone arms (Fig. 4d). The frequencies of monocytic MDSC significantly increased at the 6th vaccination (P = 0.006) in the PPV/CPA, but did not change during PPV in the PPV alone (Fig. 4e). In contrast, the absolute numbers of monocytic MDSC did not significantly change during PPV in either the PPV/CPA or PPV alone. There were no significant differences in the frequencies or absolute numbers of monocytic MDSC between both arms before and after PPV (data not shown).

The frequencies of Treg and granulocytic and monocytic MDSC before and after PPV, as well as their changes after PPV, were not significantly correlated with prognosis in either PPV/CPA or PPV alone (data not shown).

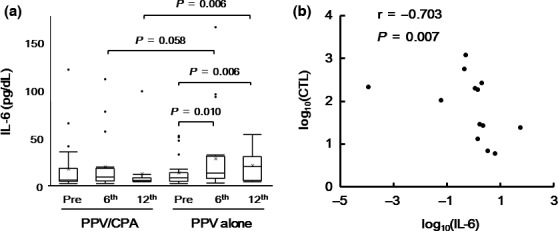

We further assessed an inflammatory cytokine IL‐6 in plasma before and after PPV, because our previous clinical trial showed that pre‐ and post‐vaccination IL‐6 values were significantly associated with OS in aBTC patients treated with PPV.4 As shown in Figure 5(a), plasma IL‐6 values significantly increased after PPV in the PPV alone (6th, P = 0.010; 12th, P = 0.006), but not in the PPV/CPA. There was a significant difference in plasma IL‐6 between both arms at 12th vaccination (P = 0.006). Of note, the changes of plasma IL‐6 were negatively correlated with those of T cell responses specific to the vaccinated peptides (Spearman rank correlation coefficient, –0.703; P = 0.007) (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Plasma IL‐6 values before and after personalized peptide vaccination (PPV). (a) The values of IL6 in plasma were examined before and after PPV (6th and 12th vaccination). Box plots show median and interquartile range (IQR). The whiskers (vertical bars) are the lowest value within 1.5× IQR of the lower quartile and the highest value within 1.5× IQR of the upper quartile. Data not included between the whiskers were plotted as an outlier with dots. “X” shows the mean of the data. (b) The correlation between the changes of plasma IL‐6 and those of T cell responses against the vaccinated peptides after vaccination were evaluated by Spearman's Rank correlation test.

The IL‐6 levels before and after PPV (at the 6th vaccination) were significantly correlated with prognosis in both the PPV/CPA (Before: HR = 5.777, 95% CI = 1.868–17.868, P = 0.002; After: HR = 9.989, 95% CI = 1.754–56.880, P = 0.010) and the PPV alone (Before: HR = 14.085, 95% CI = 3.151–62.957, P < 0.001; After: HR = 7.272, 95% CI = 1.828–28.926, P = 0.005). In addition, the changes in IL‐6 levels after PPV were also significantly correlated with prognosis in both PPV/CPA (HR = 6.341, 95% CI = 1.677–23.981, P = 0.007) and PPV alone (HR = 12.395, 95% CI = 2.629–58.437, P = 0.002).

Discussion

In the current study, the patients treated with PPV/CPA showed significantly better PFS (median time, 6.1 vs 2.9 months) and OS (median time, 12.1 vs 5.9 months) than those with PPV alone. In addition, T cell responses to the vaccinated peptides in the PPV/CPA arm tended to be greater than those in the PPV alone. These results suggested that combination with CPA could provide clinical benefits in aBTC patients under PPV, possibly due to enhanced boosting of T cell responses to the vaccinated peptides. Considering the poor prognosis in previously treated aBTC patients with MST of <9 months in most reports,19, 20, 21 the MST of 12.1 months in the PPV/CPA arm of the current study seems to be quite promising, despite the limitation of small number of patients. Although CPA has been employed in different doses and schedules as immunomodulatory agent in combination with various types of cancer immunotherapies,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 it may be possible that our current regimen of low‐dose CPA (100 mg/day) for only 7 days before vaccinations might be sufficient for providing clinical benefits for cancer peptide vaccinations.

It has been suggested that low‐dose CPA (100 mg/day) might contribute to anti‐tumor immunity, whereas higher‐dose CPA might work through its direct cytotoxic effects on tumor cells.11, 12, 13, 14 Thus, the prolonged OS in the PPV/CPA arm of the current study might be explained by enhanced anti‐tumor immunity mediated by CPA, but not by its direct effect on tumor cells, although there was no direct evidence. Of note, in the current study, IL‐6 values significantly increased in the patients treated with PPV alone, but not in those with PPV/CPA, suggesting that combined treatment with CPA inhibited IL‐6 elevation. Since the changes of IL‐6 were negatively correlated with those of peptide‐specific T cell activity after PPV, it may be possible that combination with CPA might enhance boosting of antigen‐specific T cell activity after PPV through prevention of IL‐6‐mediated immune suppression. In line with our finding, CPA treatment has been reported to augment antitumor immunity by enhancing Th1 polarization of CD4+ T cells, which might inhibit Th2‐type immune responses, including IL‐6 production.11, 13, 14

We previously reported that elevated IL‐6 levels before and after vaccination might be related to worse prognosis in aBTC patients treated with PPV.4 The current study also showed that more increase in IL‐6 after PPV, as well as higher IL‐6 values before and after PPV, were significantly correlated with worse prognosis in both PPV/CPA and PPV alone arms. Therefore, although further studies remains to confirm these results, it might be recommended that PPV should be used in combination with CPA, which might prevent the increase of IL‐6, in aBTC patients. Alternatively, agents that can inhibit IL‐6 activity, such as anti‐IL‐6 or anti‐IL‐6 receptor antibodies, could be used in aBTC patients undergoing PPV.

Low dose of CPA has been known to deplete Treg, which may suppress antigen‐specific T cell activity, in patients under various types of cancer immunotherapies.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 However, the current study showed that low‐dose CPA in our regime did not change the frequency of Treg. This might be explained by inadequate timing of blood sampling for detecting the depletion of Treg cells, since we collected blood samples around 5 weeks (35 days) after CPA treatment. Indeed, low dose CPA treatment was reported to reduce the numbers of Treg cells transiently, but not continuously for longer periods.22, 23 Alternatively, our current regimen of low‐dose CPA (100 mg/day) for only 7 days before vaccinations might be too weak to deplete Treg, since the depletion and/or suppression of Treg was generally reported to be observed in the regimens of higher doses or longer administration of CPA.10, 15, 22, 23 For example, our previous clinical trial of PPV in advanced prostatic cancer patients demonstrated that longer administration of low dose CPA (50 mg/day for 49 days) during vaccinations significantly decreased the frequencies of Treg cells.10

The current study demonstrated that combined treatment with CPA might affect the frequencies or absolute numbers of granulocytic and monocytic MDSC. The frequencies and absolute numbers of granulocytic MDSC after vaccination in the PPV/CPA were significantly higher than those in the PPV alone. In addition, the frequencies of monocytic MDSC were significantly increased after vaccinations in the PPV/CPA, but not in the PPV alone. Similar to our finding, several studies showed that low dose CPA increase the frequencies of MDSCs in mice.24, 25 Since it was also reported that CPA enhanced the therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapy despite increase in MDSCs,24 it may be possible that the CPA‐mediated increase of MDSCs might not significantly affect anti‐tumor immune responses through compensation by other anti‐tumor mechanisms, such as Treg cell suppression. The mechanism and clinical significance of changes in MDSC frequencies or numbers induced by CPA remain to be determined.

In summary, the current study suggested that combined treatment with CPA could provide clinical benefits in aBTC patients under PPV. To our knowledge, this study might be the first report showing a potential clinical benefit of CPA combined with cancer peptide vaccines in a randomized clinical study. Nevertheless, this study has several drawbacks. First, this is a small study with a limited number of patients. Secondly, uneven combined chemotherapies during the vaccination period might affect the clinical effectiveness observed in this study. To appropriately assess the clinical effectiveness of PPV, other randomized Phase II studies, which will compare PPV/CPA with PPV alone in combination with the same regimen of chemotherapies or without combined chemotherapies might be recommended. In addition, further randomized trials might also be recommended to address whether PPV/CPA might show better clinical outcomes than chemotherapies plus CPA in aBTC patients.

Disclosure Statement

Akira Yamada is a board member and has stock ownership of Green Peptide Co., Ltd. Takuto Yamashita is an employee of Green Peptide Co., Ltd. Kyogo Itoh has stock ownership of Green Peptide Co., Ltd, and received research fund from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The other authors have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. Peptide candidates used for personalized peptide vaccination.

Table S2. Immune and clinical responses.

Table S3. Toxicities.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from a research program of The Project for Development of Innovative Research on Cancer Therapeutics (P‐DIRECT) from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and a grant from the Sendai Kousei Hospital.

Cancer Sci 108 (2017) 838–845

Clinical trial registration number: UMIN000006249

Funding Information

The Project for Development of Innovative Research on Cancer Therapeutics (P‐DIRECT) from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and a grant from the Sendai Kousei Hospital.

References

- 1. Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 2011; 480: 480–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Postow MA, Callahan MK, Wolchok JD. Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 1974–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sasada T, Yamada A, Noguchi M, Itoh K. Personalized peptide vaccine for treatment of advanced cancer. Curr Med Chem 2014; 21: 2332–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yoshitomi M, Yutani S, Matsueda S et al Personalized peptide vaccination for advanced biliary tract cancer: IL‐6, nutritional status and pre‐existing antigen‐specific immunity as possible biomarkers for patient prognosis. Exp Ther Med 2012; 3: 463–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kibe S, Yutani S, Motoyama S et al Phase II study of personalized peptide vaccination for previously treated advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2014; 2: 1154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Terasaki M, Shibui S, Narita Y et al Phase I trial of a personalized peptide vaccine for patients positive for human leukocyte antigen–A24 with recurrent or progressive glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Noguchi M, Kakuma T, Uemura H et al A randomized phase II trial of personalized peptide vaccine plus low dose estramustine phosphate (EMP) versus standard dose EMP in patients with castration resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2010; 59: 1001–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoshimura K, Minami T, Nozawa M et al A phase 2 randomized controlled trial of personalized peptide vaccine immunotherapy with low‐dose dexamethasone versus dexamethasone alone in chemotherapy‐naive castration‐resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2016; 70: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Noguchi M, Matsumoto K, Uemura H et al An open‐label, randomized phase II trial of personalized peptide vaccination in patients with bladder cancer that progressed after platinum‐based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22: 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Noguchi M, Moriya F, Koga N et al A randomized phase II clinical trial of personalized peptide vaccination with metronomic low‐dose cyclophosphamide in patients with metastatic castration‐resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2016; 65: 151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sistigu A, Viaud S, Chaput N, Bracci L, Proietti E, Zitvogel L. Immunomodulatory effects of cyclophosphamide and implementations for vaccine design. Semin Immunopathol 2011; 33: 369–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Le DT, Jaffee EM. Regulatory T‐cell modulation using cyclophosphamide in vaccine approaches: a current perspective. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 3439–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Madondo MT, Quinn M, Plebanski M. Low dose cyclophosphamide: mechanisms of T cell modulation. Cancer Treat Rev 2016; 42: 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abu Eid R, Razavi GS, Mkrtichyan M, Janik J, Khleif SN. Old‐school chemotherapy in immunotherapeutic combination in cancer, a low‐cost drug repurposed. Cancer Immunol Res 2016; 4: 377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walter S, Weinschenk T, Stenzl A et al Multipeptide immune response to cancer vaccine IMA901 after single‐dose cyclophosphamide associates with longer patient survival. Nat Med 2012; 18: 1254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Slingluff CL, Petroni GR, Chianese‐Bullock KA et al Randomized multicenter trial of the effects of melanoma‐associated helper peptides and cyclophosphamide on the immunogenicity of a multipeptide melanoma vaccine. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 2924–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vermeij R, Leffers N, Hoogeboom BN et al Potentiation of a p53‐SLP vaccine by cyclophosphamide in ovarian cancer: a single‐arm phase II study. Int J Cancer 2012; 131: E670–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le DT, Wang‐Gillam A, Picozzi V et al Safety and survival with GVAX pancreas prime and listeria monocytogenes‐expressing mesothelin (CRS‐207) boost vaccines for metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 1325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lamarca A, Hubner RA, David Ryder W, Valle JW. Second‐line chemotherapy in advanced biliary cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 2328–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fornaro L, Vivaldi C, Cereda S et al Second‐line chemotherapy in advanced biliary cancer progressed to first‐line platinum‐gemcitabine combination: a multicenter survey and pooled analysis with published data. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2015; 34: 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brieau B, Dahan L, De Rycke Y et al Second‐line chemotherapy for advanced biliary tract cancer after failure of the gemcitabine‐platinum combination: a large multicenter study by the Association des Gastro‐Entérologues Oncologues. Cancer 2015; 121: 3290–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ghiringhelli F, Menard C, Puig PE et al Metronomic cyclophosphamide regimen selectively depletes CD4 + CD25 + regulatory T cells and restores T and NK effector functions in end stage cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2007; 56: 641–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ge Y, Domschke C, Stoiber N et al Metronomic cyclophosphamide treatment in metastasized breast cancer patients: immunological effects and clinical outcome. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012; 61: 353–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peng S, Lyford‐Pike S, Akpeng B et al Low‐dose cyclophosphamide administered as daily or single dose enhances the antitumor effects of a therapeutic HPV vaccine. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2013; 62: 171–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ding ZC, Lu X, Yu M et al Immunosuppressive myeloid cells induced by chemotherapy attenuate antitumor CD4 + T‐cell responses through the PD‐1‐PD‐L1 axis. Cancer Res 2014; 74: 3441–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Peptide candidates used for personalized peptide vaccination.

Table S2. Immune and clinical responses.

Table S3. Toxicities.