Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of the selected non-pharmacological lifestyle activities on the delay of cognitive decline in normal aging. This was done by conducting a literature review in the four acknowledged databases Web of Science, Scopus, MEDLINE, and Springer, and consequently by evaluating the findings of the relevant studies. The findings show that physical activities, such as walking and aerobic exercises, music therapy, adherence to Mediterranean diet, or solving crosswords, seem to be very promising lifestyle intervention tools. The results indicate that non-pharmacological lifestyle intervention activities should be intense and possibly done simultaneously in order to be effective in the prevention of cognitive decline. In addition, more longitudinal randomized controlled trials are needed in order to discover the most effective types and the duration of these intervention activities in the prevention of cognitive decline, typical of aging population groups.

Keywords: cognitive impairment, healthy older individuals, intervention, benefits

Background

Cognitive skills play a crucial role in the daily functioning of older people. Unfortunately, some of these cognitive skills (eg, memory, problem-solving activities, or speed processing) decline in the process of aging.1–4 There are several risk factors which appear to have an impact on cognitive decline.5 These risk factors can be divided into modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. The non-modifiable risk factors include age, race and ethnicity, gender, and genetics.6 In fact, it has been proved that 60% of general cognitive ability is of genetic origin.7 The modifiable risk factors mainly involve diabetes, head injuries, lifestyle, and education.8

Furthermore, Klimova and Kuca9 divide the non-pharmacological lifestyle intervention activities into three most influential groups which have a positive impact on cognitive decline: physical activities, healthy diet, and cognitive training. These activities have a positive effect on the maintenance of synaptic function whose loss is usually connected with toxic forms of amyloid-β protein, which can result in the onset of aging diseases such as dementia. However, thanks to the non-pharmacological activities and their intensity, this synapse and synaptic protein loss may be prevented. In addition, physical activities can contribute to the increase of vascularization, energy metabolism, and resistance against oxidative stress, which has a positive effect on cognitive functions.10 Recent research11,12 has also revealed beneficial effects of music therapies in the prevention of cognitive decline. Since there are findings13–16 that certain non-pharmacological lifestyle activities such as physical activities or adherence to Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) may contribute to the prevention of cognitive aging, the purpose of this study is to examine the effects of the selected non-pharmacological lifestyle activities on the delay of cognitive decline in normal aging. This is done on the basis of the findings from the selected studies. Since pharmacological intervention is relatively costly, might have serious side effects, and impose a severe social burden, the main purpose of this review is to analyze and compare the effects of non-pharmacological activities – physical activities/exercises, adherence to MedDiet, music therapy, and cognitive training such as solving crosswords – on the prevention of cognitive decline in normal aging.17

Methods

The methodology used in this review is based on the study of Moher et al.18 The relevant studies were searched using key words in four acknowledged databases: Web of Science, Springer, Scopus, and MEDLINE. This review screened for studies conducted in the period from 2000 to June 2016, using the following key words: cognitive skills in normal aging AND intervention strategies; healthy older people AND cognitive decline AND physical activities; healthy older people AND cognitive decline AND physical exercises; healthy older people AND cognitive decline AND Mediterranean diet; and healthy older people AND cognitive decline AND music.

A study was included if it matched the corresponding period, from 2000 up to June 2016. The selection period started with the year of 2000 because this is the year when the studies on the research topic conducted among older people started to appear. Furthermore, the study was included if it involved healthy older people without any cognitive impairment or dementia, aged 60+ years, and focused on the topic of non-pharmacological lifestyle intervention strategies, that is, physical activities/exercises, adherence to MedDiet, music therapy, or mental activity such as solving a crossword. All studies had to be written in English to be included in this review.

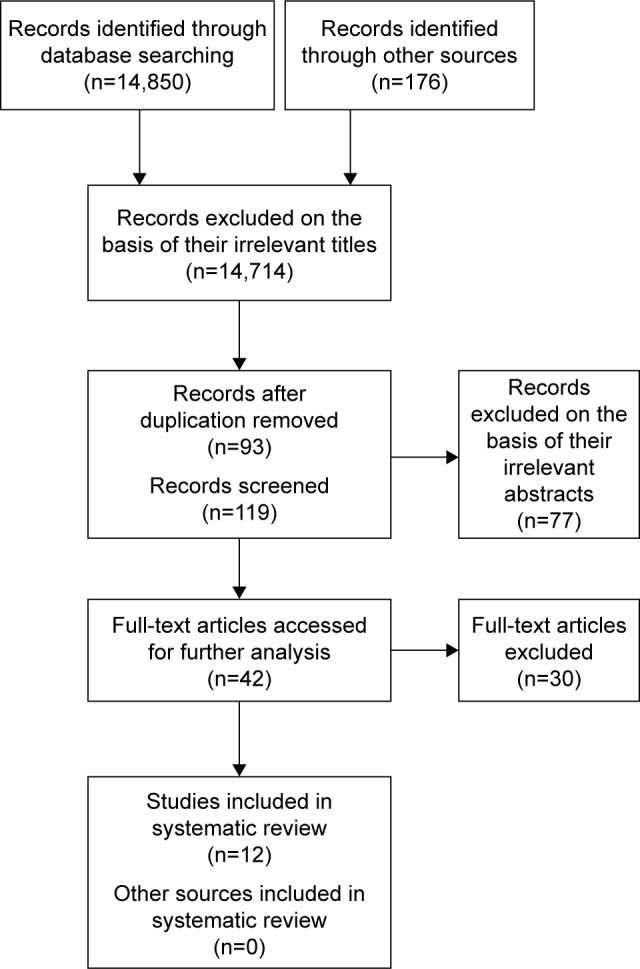

This review included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, descriptive studies, retrospective studies, theoretical articles, reviews, books, book chapters, web pages, study protocols, seminar papers, and abstracts on the research topic. The majority of the included studies were detected in the Springer database (14,641 studies), followed by Web of Science (110 studies), Scopus (61 studies), and MEDLINE (38 studies). Altogether 14,850 studies were found via the database search, and 176 from other available sources (ie, web pages, conference proceedings, and books outside the scope of the databases described above). Then, the titles of all the included studies were checked in order to confirm whether they focus on the research topic, and irrelevant studies were excluded. In addition, duplicate studies were also excluded. After this step, 119 studies remained for further analysis. Afterwards, the authors checked the content of the abstracts to verify whether the study examined the relevant research topic. Finally, 42 studies/articles were selected for the full-text analysis, out of which the findings of 30 studies are compared in the present review and the remaining 12 studies were used for the detailed analysis of the research topic (Figure 1). The rigid process of selection of these studies is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the selection procedure.

Findings

Altogether 12 studies focusing on the research topic were identified. Out of these studies, six exclusively focused on physical activities, two on MedDiet, two on a music therapy, one on an educational program, and one on doing crosswords. The intervention period in the studies ranged from 2 weeks to 6.5 years. The subject samples also varied; the smallest sample of subjects consisted of 21 older individuals, whereas the largest one involved 716 older adults. The efficacy of the intervention therapies focused on the prevention of cognitive decline in the studies was measured with the available validated cognitive assessment tools such as cognitive tests and/or magnetic resonance imaging. Table 119–28 provides an overview of the main findings of these studies. The results are summarized in alphabetical order of their first author name.

Table 1.

Overview of the 12 selected studies focused on cognitive decline and its prevention by intervention activities

| Author | Objective | Type of the intervention activity and its frequency | Intervention period | Number of subjects | Main outcome assessments | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buchman et al19 (observational cohort study) | To verify a hypothesis that objective measure of total daily physical activity predicts incident AD and cognitive decline | Daily physical activities for 24 hours for 10 days | 4 years | 716 older subjects free of dementia. No control group | Structured annual clinical examination including a battery of 19 cognitive tests; actigraphy | People who do more physical activities per day have a lower risk of cognitive decline than those doing it only occasionally |

| Bugos et al11 (RCT) | To assess the efficacy of IPI on executive functioning and working memory in older healthy individuals | IPI: the intervention group had a 30-minute lesson per week and practiced for 3 hours a week at minimum | 9 months | 31 musically naïve seniors (60–85 years). Two randomly assigned groups: intervention group (16 subjects) and passive control group (15 subjects) | Neuropsychological assessments were administered at three time points: pre-training, following 6 months of intervention, and following a 3-month delay | Results of this study suggest that IPI may serve as an effective cognitive intervention for age-related cognitive decline |

| Colcombe et al20 (RCT) | To assess whether aerobic fitness training of older humans can increase brain volume in regions associated with age-related decline in both brain structure and cognition | Aerobic training in the intervention group; toning and stretching exercises in the active control group; three 1-hour exercises per week in both groups | 6 months | 59 healthy but sedentary community-dwelling volunteers, aged 60–79 years. 30 subjects in the intervention group and 29 in the active control group +20 younger passive controls | Magnetic resonance imaging; a graded exercise test on a motor-driven treadmill; peak oxygen uptake (VO2 peak) was measured from expired air samples taken at 30-second intervals until the highest VO2 peak was attained at the point of volitional exhaustion | The results show that the participation in an aerobic exercise program increased volume in both gray and white matter primarily located in prefrontal and temporal cortices in comparison with no effects in the active non-aerobic control group |

| Erickson et al21 (descriptive study) | To investigate whether individuals with higher levels of aerobic fitness display greater volume of the hippocampus and better spatial memory performance than individuals with lower fitness levels | Aerobic exercises | NA | 165 nondemented older adults | In exploratory analyses, it was assessed whether hippocampal volume mediated the relationship between fitness and spatial memory; by using a region-of-interest analysis on magnetic resonance images a triple association such that higher fitness levels were associated with larger left and right hippocampi after controlling for age, sex, and years of education, and larger hippocampi and higher fitness levels were correlated with better spatial memory performance | The results indicate that higher levels of aerobic fitness are associated with increased hippocampal volume in older humans, which translates to better memory function |

| Martinez-Lapiscina et al22 (RCT) | To assess the effect on cognition of a controlled intervention testing MedDiet | MedDiet (supplemented with EVOO or mixed nuts) versus a low-fat control diet; participants allocated to the MedDiet groups received EVOO (1 L/week) or 30 g/day of mixed nuts | Clinical trial after 6.5 years of nutritional intervention | 285 subjects, 44.8% men, 74.1±5.7 years; 95 randomly assigned to each of three groups | Evaluation by two neurologists blinded to group assignment after 6.5 years of nutritional intervention | Better post-trial cognitive performance versus control in all cognitive domains and significantly better performance across fluency and memory tasks were observed for participants allocated to the MedDiet + EVOO group |

| Miller et al23 (observational study) | To determine whether a 6-week educational program can lead to improved memory performance in older adults | Educational program on memory training, physical activity, stress reduction, and healthy diet; 60-minute classes held twice weekly with 15–20 participants per class | 6 weeks | 115 participants (mean age: 80.9 [SD: 6.0 years]); no control group | Objective cognitive measures evaluated changes in five domains: immediate verbal memory, delayed verbal memory, retention of verbal information, memory recognition, and verbal fluency. A standardized metamemory instrument assessed four domains of memory self-awareness: frequency and severity of forgetting, retrospective functioning, and mnemonics use | The findings indicate that a 6-week healthy lifestyle program can improve both encoding and recalling of new verbal information, as well as self-perception of memory ability in older adults residing in continuing care retirement communities |

| Murphy et al24 (RCT) | To evaluate the effect on PVF performance of a brief crossword-based intervention in a cognitively normal, community-based sample | The intervention group was doing a crossword on a daily basis; the control group was keeping a daily gratitude diary for the same period | 4 weeks | 37 older subjects divided randomly into the intervention and control group | 2×2 mixed analyses of variance has been conducted | The results indicate that the crossword group performed significantly better over time than the control group in both total PVF score and in the cluster size component |

| Muscari et al25 (RCT) | To evaluate the effects of EET on the cognitive status of healthy community-dwelling older adults | The intervention group had a 12-month supervised EET in a community gym, 3 hours a week | 12 months | 120 healthy subjects aged 65–74 years; 60 subjects in the intervention group; 60 in the passive control group | Cognitive status was assessed by one single test (MMSE). Anthropometric indexes, routine laboratory measurements, and C-reactive protein were also assessed | The control group showed a significant decrease in MMSE score (mean difference −1.21, 95% CI −1.83/−0.60, P=0.0002), which differed significantly (P=0.02) from the intervention group scores (−0.21, 95% CI −0.79/0.37, P=0.47) |

| Sato et al26 (RCT) | To compare the effects of water-based exercise with and without cognitive stimuli on cognitive and physical functions | The exercise sessions were divided into two exercise series: a 10-minute series of land-based warm-up, consisting of flexibility exercises, and a 50-minute series of exercises in water. The Nor-WE consisted of 10 minutes of walking, 30 minutes of strength and stepping exercise, including stride over, and 10 minutes of stretching and relaxation in water. The Cog-WE consisted of 10 minutes of walking, 30 minutes of water-cognitive exercises, and 10 minutes of stretching and relaxation in water | 10 weeks | 21 older subjects were randomly divided into the intervention group and the active control group | Cognitive function, physical function, and ADL were measured before the exercise intervention (pre-intervention) and 10 weeks after the intervention (post-intervention) | The findings show that participation in the Cog-WE considerably improved attention, memory, and learning, and in the general cognitive, while participation in the Nor-WE dramatically improved walking ability and lower limb muscle strength. The results reveal that the benefits depend on the characteristics of each specific exercise program. These findings highlight the importance of prescription for personalized water-based exercises to elderly adults to improve cognitive function |

| Simoni et al27 (cross-sectional study) | To compare the effects of overground and treadmill gait on dual task performance in older healthy adults | Overground walking and treadmill walk | The treadmill testing was performed first, followed by overground testing between 1 and 2 weeks | 29 healthy older adults (mean age 75 years, 14 females) | Gait kinematic parameters and cognitive performance were obtained in 29 healthy older adults when they were walking freely on a sensorized carpet or during treadmill walking with an optoelectronic system, in single task or dual task conditions, using alternate repetition of letters as a cognitive verbal task | Both motor and cognitive performances decline during dual task testing with overground walking, while cognitive performance remains unaffected in dual task testing on the treadmill. These findings suggest that treadmill walk does not involve brain areas susceptible to interference from the introduction of a cognitive task |

| Tai et al12 (RCT) | To identify the effect of music intervention on cognitive function and depression status of residents in senior citizen apartments | Buddhist hymns; the intervention group listened to the 30-minute Buddhist hymns using the Buddha machine alone twice a day (in the morning and before bedtime) from Monday to Friday for 4 months; they also took a note if they finished their daily music therapy | 4 months | 60 healthy seniors, aged 65+; 41 participated in the intervention music group and 19 in the passive comparison group | MMSE and the Geriatric Depression Scale-short form at the baseline, 1 month, and 4 months | Music intervention, specifically Buddhist hymns may delay cognitive decline and improve mood of older people |

| Valls-Pedret et al28 (RCT) | To investigate whether a MedDiet supplemented with antioxidant-rich foods influences cognitive function compared with a control diet | Participants were randomly assigned to MedDiet supplemented with EVOO (1 L/week), MedDiet supplemented with mixed nuts (30 g/day), or a control diet (advice to reduce dietary fat) | 5 years | 447 cognitively healthy volunteers (233 women [52.1%]; mean age, 66.9 years); three groups: two intervention groups and one control group | A neuropsychological test battery: MMSE, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, Animals Semantic Fluency, Digit Span subtest from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Verbal Paired Associates from the Wechsler Memory Scale, and the Color Trail Test | In an older population, a MedDiet supplemented with olive oil or nuts is associated with improved cognitive function |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ADL, activities of daily living; CI, confidence interval; EET, endurance exercise training; EVOO, extravirgin olive oil; IPI, individualized piano instruction; MedDiet, Mediterranean diet; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; NA, not available; PVF, phonemic verbal fluency; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation.

The findings of all studies in Table 1 exhibit positive results as far as cognitive functions (ie, executive functions, better memory, learning, attention, or verbal fluency) are concerned. Based on the evidence of the outcome measures, all studies indicate that cognitive functions can be maintained or even enhanced by intervention activities such as sport (eg, walking or aerobic exercises), music, healthy MedDiet, or doing crosswords. The findings also suggest that the immediate results may be detected after intervening for just 1 month. However, this is questionable because according to Kurz and van Baelen,29 the minimum period for medication assessment as suggested by regulatory authorities is 24 weeks.

Discussion

The findings from the selected studies in Table 1 are discussed in this section according to their representation of intervention activities. Thus, the majority of studies deal with physical activities. The results show that people who do more physical activities per day have a lower incidence of cognitive decline compared with those doing them occasionally. The same is true for their intensity. For example, Larson et al30 claim that intensive physical activities may delay the decline of cognitive functioning. They indicate that people who exercise three times a week or more fall ill with dementia less compared with those who conduct physical exercises less than three times a week. Thus, it seems that healthy older people who do physical activities regularly and intensively at least two to three times a week may enhance their cognitive functions. However, another study performed for a period of 15 years by Sorman et al31 among 1,475 healthy individuals aged 65 years and above shows that the positive outcomes of these physical activities may be valid just for a shorter time span, but there is a little support for the effect of the physical activities in the prevention of cognitive decline in a longer time span. This is also supported by a review,19 whose authors report that the benefits of physical activity are small and cumulative over many years and they may be beyond resolution by RCTs.

Studies11,12,32,33 also emphasize the role of music therapy, especially listening to Buddhist hymns,12 in the improvement of cognitive competences because music may recall past memories and activate patient’s brain more as affects both the hemispheres of the brain. In fact, music comprehension is connected with one specific area of the brain that remains intact even after all other functions, such as verbal language, are impaired.34 For example, a study12 shows that the results obtained over a 4-month follow-up period revealed a significant difference between the experimental group and comparison group in cognitive scores. After 4 months, a significant decline in the Mini-Mental State Examination score compared with the initial score was observed in the comparison group, but not in the experimental group. Furthermore, Craig33 suggests that music therapies should be done in groups in order for them to be effective, that is, regularly twice a week, and patients should be exposed to such kind of music that is familiar to them and in which they are engaged.

Furthermore, some studies22,28 prove the benefits of MedDiet, especially if it is rich in olive oil and nuts. Recent studies35–37 indicate that a proper dietary regime plays a crucial role in the maintenance of optimal synoptic function.

The findings of the analyzed studies also prove the efficacy of solving crosswords on cognitive decline24 because learning something new and training the brain may lower the risk of cognitive decline.10 However, they must be done several times a week. For example, Verghese et al38 in their study confirm that if a person solves crosswords four times a week, she/he can reduce the risk of dementia by 47% compared with the person who does it only once a week.

Recent studies have revealed that the most effective type of intervention activity seems to be the one which consists of several intervention activities.39,40 Nevertheless, these activities must be done on a regular basis, ideally several times a week, and people should start with them in their middle age.41

The limitations of this review are the lack of available RCTs on the research issue and the different methodologies of the included publications such as the use of passive control groups, or no intervention group at all, or small subject samples. These insufficiencies may result in the overestimated effects of the discussed findings and have a negative impact on the validity of the reviewed studies.42–44 The heterogeneity of the selected studies also prevented the authors from conducting the meta-analysis.

Conclusion

The results of this review indicate that all the selected non-pharmacological lifestyle intervention strategies explored appear to have positive effects on the cognitive functions in older people. These therapies are generally less costly and noninvasive in comparison with the pharmacological treatment, which is usually lengthy and brings about possible side effects. Older people also have a chance to meet with their peers while performing these preventive non-pharmacological therapies. Nevertheless, the findings of this study also suggest that future research should focus on conducting more longitudinal RCTs with larger samples of subjects in order to discover the most effective types and the duration of these intervention activities for the prevention of cognitive decline, typical of aging population groups.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the project Excelence 2017 run at the Faculty of Informatics and Management of the University of Hradec Kralove and the long-term development plans of the University Hospital Hradec Kralove and University of Hradec Kralove.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests to declare in this work.

References

- 1.Harada CN, Natelson Love MC, Triebel K. Normal cognitive aging. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(4):737–752. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reichman WE, Fiocco AJ, Rose NS. Exercising the brain to avoid cognitive decline: examining the evidence. Aging Health. 2010;6(5):565–584. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craik F, Salthouse T. The Handbook of Aging and Cognition. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salthouse T. Consequences of age-related cognitive declines. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:201–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(9):819–828. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deary IJ, Corley J, Gow AJ, et al. Age-associated cognitive decline. Br Med Bull. 2009;92:132–152. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldp033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClearn GE, Johansson B, Berg S, et al. Substantial genetic influence on cognitive abilities in twins 80 or more years old. Science. 1997;276:1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5318.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(8):788–794. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klimova B, Kuca K. Alzheimer’s disease: potential preventive, non-invasive, intervention strategies in lowering the risk of cognitive decline – a review study. J Appl Biomed. 2015;13(4):257–261. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clare R, King VG, Wirenfeldt M, Vinters HV. Synapse loss in dementias. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88(10):2083–2090. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugos JA, Perlstein WM, McCrae CS, Brophy TS, Bedenbaugh PH. Individualized piano instruction enhances executive functioning and working memory in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(4):464–471. doi: 10.1080/13607860601086504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tai S-Y, Wang L-C, Yang Y-H. Effect of music intervention on the cognitive and depression status of senior apartment residents in Taiwan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1449–1454. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S82572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klimova B, Maresova P, Kuca K. Non-pharmacological approaches to the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease with respect to the rising treatment costs. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016;13(11):1249–1258. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666151116142302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erickson KI, Kramer AF. Aerobic exercise effects on cognitive and neural plasticity in older adults. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(1):22–24. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.052498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bherer L, Erickson KI, Liu-Ambrose T. A review of the effects of physical activity and exercise on cognitive and brain functions in older adults. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:ID657508. doi: 10.1155/2013/657508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tagney CC. DASH and Mediterranean-type dietary patterns to maintain cognitive health. Curr Nutr Rep. 2014;3(1):51–61. doi: 10.1007/s13668-013-0070-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maresova P, Klimova B, Novotny M, Kuca K. Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s diseases: expected economic impact on Europe – a call for a uniform European strategy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(3):1123–1133. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Yu L, Shah RC, Wilson RS, Bennett DA. Total daily physical activity and the risk of AD and cognitive decline in older adults. Neurology. 2012;78(17):1323–1329. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colcombe SJ, Erickson KI, Scalf PE, et al. Aerobic exercise training increases brain volume in aging humans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(11):1166–1170. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.11.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erickson KI, Prakash RS, Voss MW, et al. Aerobic fitness is associated with hippocampal volume in elderly humans. Hippocampus. 2009;19(10):1030–1039. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Lapiscina EH, Clavero P, Toledo E, et al. Virgin olive oil supplementation and long-term cognition: the PREDIMED-NAVARRA randomized, trial. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(6):544–552. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller KJ, Siddarth P, Gaines JM, et al. The memory fitness program: cognitive effects of a healthy aging intervention. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(6):514–523. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318227f821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy M, O’Sullivan K, Kelleher KG. Daily crosswords improve verbal fluency: a brief intervention study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(9):915–919. doi: 10.1002/gps.4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muscari A, Giannoni C, Pierpaoli L, et al. Chronic endurance exercise training prevents aging-related cognitive decline in healthy older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(10):1055–1064. doi: 10.1002/gps.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato D, Seko C, Hashitomi T, Sengoku Y, Nomura T. Differential effects of water-based exercise on the cognitive function in independent elderly adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27(2):149–159. doi: 10.1007/s40520-014-0252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simoni D, Rubbieri G, Baccini M, et al. Different motor tasks impact differently on cognitive performance of older persons during dual task tests. Clin Biomech (Bristol Avon) 2013;28(6):692–696. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valls-Pedret C, Sala-Vila A, Serra-Mir M, et al. Mediterranean diet and age-related cognitive decline: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1094–1103. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurz A, van Baelen B. Ginkgo biloba compared with cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of dementia: a review based on meta-analyses by the Cochrane collaboration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18(2):217–226. doi: 10.1159/000079388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larson EB, Wang L, Bowen JD, et al. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):73–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorman DE, Sundstrom A, Ronnlund M, Adolfsson R, Nilsson LG. Leisure activity in old age and risk of dementia: a 15-year prospective study. J Gerontology B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(4):493–501. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balbag MA, Pedersen NL, Gatz M. Playing a musical instrument as a protective factor against dementia and cognitive impairment: a population-based study. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;2014:836748. doi: 10.1155/2014/836748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig J. Music therapy to reduce agitation in dementia. Nurs Times. 2014;10(32–33):12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooke M, Moyle W, Shum D, Harrison S, Murfield J. A randomized controlled trial exploring the effect of music on quality of life and depression in older people with dementia. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(5):765–776. doi: 10.1177/1359105310368188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arab L, Sabbagh MN. Are certain life style habits associated with lower Alzheimer disease risk? J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(3):785–794. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swaminathan A, Jicha GA. Nutrition and prevention of Alzheimer’s dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:282. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mosconi L, Murray J, Tsui WH, et al. Mediterranean diet and magnetic resonance imaging-assessed brain atrophy in cognitively normal individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2014;1(1):23–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verghese JM, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2508–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fissler P, Kolassa I-T, Schrader C. Educational games for brain health: revealing their unexplored potential through a neurocognitive approach. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1056. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paillard T, Rolland Y, de Sonto Barreto P. Protective effects of physical exercise in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: a narrative review. J Clin Neurol. 2015;11(3):212–219. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2015.11.3.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melby-Lervag M, Hulme C. There is no convincing evidence that working memory training is effective: a reply to Au et al. (2014) and Karbach and Verhaeghen (2014) Psychon Bull Rev. 2016;23(1):324–330. doi: 10.3758/s13423-015-0862-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melby-Lervag M, Hulme C. Is working memory training effective? A meta-analytic review. Dev Psychol. 2013;49(2):270–291. doi: 10.1037/a0028228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klimova B. Use of the Internet as a prevention tool against cognitive decline in normal aging. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1231–1237. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S113758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maresova P, Mohelska H, Dolejs J, Kuca K. Socio-economic aspects of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12(9):903–911. doi: 10.2174/156720501209151019111448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]