Abstract

Background

Frailty is an aging syndrome caused by exceeding a threshold of decline across multiple organ systems leading to a decreased resistance to stressors. Treatment for frailty focuses on multi-domain interventions to target multiple affected functions in order to decrease the adverse outcomes of frailty. No systematic reviews on the effectiveness of multi-domain interventions exist in a well-defined frail population.

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to determine the effect of multi-domain compared to mono-domain interventions on frailty status and score, cognition, muscle mass, strength and power, functional and social outcomes in (pre)frail elderly (≥65 years). It included interventions targeting two or more domains (physical exercise, nutritional, pharmacological, psychological, or social interventions) in participants defined as (pre)frail by an operationalized frailty definition.

Methods

The databases PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, PEDro, CENTRAL, and the Cochrane Central register of Controlled Trials were searched from inception until September 14, 2016. Additional articles were searched by citation search, author search, and reference lists of relevant articles. The protocol for this review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42016032905).

Results

Twelve studies were included, reporting a large diversity of interventions in terms of content, duration, and follow-up period. Overall, multi-domain interventions tended to be more effective than mono-domain interventions on frailty status or score, muscle mass and strength, and physical functioning. Results were inconclusive for cognitive, functional, and social outcomes. Physical exercise seems to play an essential role in the multi-domain intervention, whereby additional interventions can lead to further improvement (eg, nutritional intervention).

Conclusion

Evidence of beneficial effects of multi-domain compared to mono-domain interventions is limited but increasing. Additional studies are needed, focusing on a well-defined frail population and with specific attention to the design and the individual contribution of mono-domain interventions. This will contribute to the development of more effective interventions for frail elderly.

Keywords: nutrition, supplement, exercise, cognition, hormone, social, vulnerable, older adults

Introduction

Frailty is a late-life syndrome that results from reaching a threshold of decline across multiple organ systems.1 Because frailty leads to excess vulnerability and reduced ability to maintain homeostasis, frail elderly are predisposed to functional deficits, comorbidity, and mortality.1,2

Despite a lack of international consensus on the definition of frailty, two conceptual definitions are commonly used.3,4 First, Fried et al introduced the frailty phenotype and described frailty based on the presence of five physical characteristics: unintentional weight loss, weakness, exhaustion, slow gait, and low physical activity.5,6 Subjects are considered robust (no criteria present), prefrail (1 or 2 criteria present), or frail (3–5 criteria present).5 Second, the frailty index of Rockwood and Mitnitski defines frailty as an accumulation of heterogeneous deficits identified by a comprehensive geriatric assessment.7 The index reflects the proportion of present deficits to the total number of potential deficits, to determine whether a patient is robust (≤20%), prefrail (20%–35%), or frail (≥35%).7,8 The frailty index represents a broader scope of frailty, including cognitive, social, and psychological components, next to the physical characteristics. Although the frailty syndrome includes multiple domains, physical frailty (and more specifically musculoskeletal frailty) is seen as the main component of frailty.2,9

Depending on the frailty definition and evaluation tool, frailty prevalence ranges between 4.0% and 59.1% in community-dwelling people aged >65 years.10 As the population ages, frailty represents increasingly important public health concerns and has an incremental effect on health expenditures (additional ±€1500/frail person/year).11,12 Because of the major clinical and economic burden, it is critical to find efficient, feasible, and cost-effective interventions to prevent or slow down frailty in order to avoid or diminish the adverse outcomes and maintain or improve quality of life.1,9

Frailty is possibly reversible or modifiable by interventions.13–16 Previous research on nonpharmacological interventions such as physical exercise and nutritional interventions showed promising effects on frailty status, functional outcomes, and cognitive outcomes.17–19 These interventions can be combined with each other or with other (eg, pharmacological, hormonal, or cognitive) therapies to prevent or treat frailty.20 As frailty results from reaching a threshold of decline in different physiological systems, the approach to address frailty should act on multiple domains.13,21

Previous overviews of multi-domain interventions only examined combinations of exercise and nutritional interventions.22 Also, studies combining more than two domains were not in their scope of interest.23 Other reviews focused on other populations (eg, sarcopenia or obesity)22,24–26 or included studies that used no diagnostic tool to determine the frail population27,28 or used poor search criteria for (pre) frail participants (eg, only one keyword in database search).29 Because of the limitations of existing reviews as well as to include information from recent studies, a systematic review was conducted, aiming to provide an overview of the effects of controlled multi-domain interventions in (pre)frail people aged ≥65 years on frailty status and score, cognition, muscle mass strength and power, and functional and social outcomes.

Methodology

The review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42016032905) and was reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.30

Search methods

First, a systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, PEDro, CENTRAL, and the Cochrane Central register of Controlled Trials from inception of the database until September 14, 2016, to ensure comprehensive article retrieval. The search strategy was developed for PubMed (Figure S1) and then translated for use in other databases (available upon request). The literature search was limited to articles published in English, Dutch, French, or German and excluded case reports, letters, and editorials. Second, additional studies were searched by hand-searching reference lists, citations, and other publications from first and last authors from relevant papers retrieved in the first search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria are as follows: 1) randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, or prospective or retrospective cohort studies with control groups; 2) testing of a multi-domain intervention to prevent or treat frailty in people aged ≥65 years; 3) classification in terms of (pre) frailty status according to an operationalized definition; and 4) primary outcomes including one or more of the following: frailty status or score, muscle mass, strength or power, physical functioning, and cognitive or social outcomes.

A multi-domain intervention was defined as an intervention that intervenes in at least two different domains, including exercise therapy (Ex), nutritional intervention (supplementation of proteins [NuP], supplementation of vitamins and minerals [NuVM], milk fat globule membrane [NuMF], or nutritional advice [NuAd]), hormone (Hor), cognitive (Cog) or psychosocial (PS) interventions. Studies that did not compare groups in view of the delivered multi-domain intervention were excluded.

Study selection

Identification of potentially relevant papers based on title and abstract was conducted by one reviewer (LD). Thereafter, the full texts of all potentially relevant abstracts were examined for eligibility. In case of inconclusiveness, a second reviewer (JT) was consulted to discuss eligibility. In case of disagreement, consensus was sought between the reviewers or involvement of a third reviewer (EG) was asked.

Critical appraisal

Risk of bias in the individual studies was assessed by the methodological index for nonrandomized studies (MINORS). The following 12 MINORS criteria were evaluated by two independent researchers (LD and MD): clearly stated aim, inclusion of consecutive patients, prospective collection of data, endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study, unbiased assessment of the study endpoint, follow-up period appropriate to the aim of the study, loss to follow-up <5%, prospective calculation of the study size, adequate control group, contemporary groups, baseline equivalence of groups, and adequate statistical analyses.31 Each criterion was scored 0 (not reported), 1 (reported but inadequate), or 2 points (reported and adequate), resulting in a total quality score ranging from 0 (low quality) to 24 (high quality).

Data extraction and synthesis

The following data were extracted from the included studies: study characteristics (aim, country, design, and setting), participant characteristics (age and gender), frailty diagnostic tool, characteristics of multi-domain interventions (duration, content, frequency, intensity, follow-up moments, and compliance), characteristics of intervention and control groups (number of participants and loss to follow-up), frailty status or score, cognition, muscle mass, strength or power, functional and social outcomes, and quality-of-life measurements. Data on effect measures (mean ± standard deviation or median [10th–90th percentile]) of the included studies were extracted up to 1 year after the intervention. Data were extracted by one researcher (LD) and checked by a second reviewer (EG or JT). Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers.

The primary outcomes were frailty status, cognition, muscle mass, muscle strength, and power and functional outcomes. Secondary outcomes are quality of life, social involvement, psychosocial well-being, and depression and subjective health. The effects between intervention groups were reported, as this study focuses on the effect of multi-domain interventions compared to mono-domain interventions. No effects over time within individual groups were reported. No meta-analysis was performed due to high heterogeneity of the study interventions and outcomes.

Results

Study selection

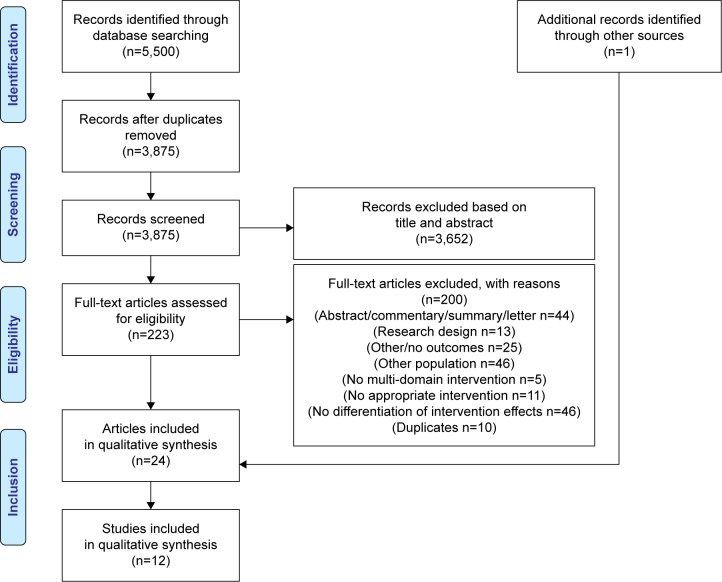

Figure 1 visualizes the study selection process based on the PRISMA flowchart.30 The literature search yielded 5,500 publications. To assess the eligibility of the articles, full texts were read, and 200 articles were excluded with reasons (Table S1). Overall, 24 articles reporting on twelve individual studies met the study eligibility criteria and were included in this systematic review.32–55

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process.

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the study characteristics. Five studies were conducted in Europe,33,46,50,53,54 two in the USA,41,42 and five in Asia.32,43–45,55 Eleven studies32,33,41–46,50,53,54 had a randomized controlled design and one study55 had a randomized crossover design. The studies ranged in sample size from 31 to 246.41,45 The duration of the intervention varied between 12 weeks32,43,44,53,55 and 9 months.46 Five studies included a follow-up moment at 3–9 months after the intervention.32,43–46 Nine of the twelve studies were dated from 2010 onwards.32,42–45,50,53–55

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Study | Country | Study participants | Duration of the intervention | Measurements

|

Study design | N | Frailty diagnostic tool | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention period

|

Follow-up period

|

|||||||||||

| Pre | 3 months before end of intervention | Post (0 months) | 3–4 months | 6 months | 9 months | |||||||

| Chan et al32 | Taiwan | (Pre)frail, men and women, aged 71.4 (±3.7) | 3 months | * | * | * | * | RCT | 117 | 3–6 on The Chinese Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale Telephone Version AND ≥1 of modified Fried frailty phenotype criteriab | ||

| Chin A Pawet al33,34,39 and De Jong et al35–38,40 | The Netherlands | Frail, men and women, aged 79a | 17 weeks | * | * | RCT | 112–161 | Modified Chin A Paw frailty definitionc | ||||

| Hennessey et al41 | United States | Moderately frail, men and women, aged 71.3 (±4.5) | 6 months | * | * | RCT | 31 | Physical performance test (PPT): score (12–28)/36d | ||||

| Ikeda et al55 | Japan | (Pre)frail, men and women, aged 78.4±7.8 and 80.4±8.9 | 3 months | * | * | Cross-over | 52 | Fried frailty phenotype criteriae | ||||

| Kenny et al42 | United States | Frail, women, aged 76.6 (±6.0) | 6 months | * | * | RCT | 99 | At least 1 of 5 Fried frailty criteria: population is at least prefraile | ||||

| Kim et al43 | Japan | Frail, women, aged 75+ | 3 months | * | * | * | RCT | 131 | At least 3 of the modified Fried frailty phenotype criteriaf | |||

| Kwon et al44 | Japan | Prefrail, women, aged 76.8 | 3 months | * | * | * | RCT | 89 | Modified Fried frailty phenotype criteriag | |||

| Luger et al53 | Austria | (Pre)frail, men and women, aged 82.8(±8.0) | 12 weeks | * | * | RCT | 80 | Prefrail or frail according to Frailty Instrument for Primary Care of the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE-FI)h | ||||

| Ng et al45 | Singapore | (Pre)frail, men and women, aged 70.0 (±4.7) | 6 months | * | * | * | * | RCT | 246 | Fried frailty phenotype criteriae | ||

| Rydwik et al46–48 Lammes et al49 |

Sweden | Frail, men and women, aged 83.3(±4.0) | 9 months | * | * | * | RCT | 96 | Modified Chin A Paw frailty definitionc | |||

| Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54 | Spain | Frail, men and women, aged 70+ | 24 weeks | * | * | RCT | 100 | Fried frailty phenotype criteriae | ||||

| Tieland et al50 and Van de Rest et al51 | The Netherlands | (Pre)frail, men and women, aged 78(±1.0) | 24 weeks | * | * | RCT | 62 | 1–2 (prefrail) or at least 3(frail) of the Fried frailty phenotype criteriae | ||||

Notes:

Reported mean age of largest study group.

Chan et al: 3/6 on the CCSHA_CFS_TV84,85 for first-stage screening. CHS-PCF5 with modifications: weight loss of 3 kg instead of 5 kg; Taiwan international physical activity questionnaire short form instead of the Minnesota Leisure time physical activity questionnaire86 to measure energy expenditure.

Chin A Paw et al and Rydwik et al: Physical activity in combination with weight loss is used as an effective screening criterion for identifying frailty.87 The first criterion, inactivity, is defined as not participating regularly in physical activities of moderate to high intensity, defined as >30 minutes of brisk walking, cycling, or gymnastics weekly in Chin A Paw et al, and as ≤ grade 3/6 scale of physical activity88,89 in Rydwik et al. The second criterion is involuntary weight loss (≥5% in Rydwik et al) or a BMI below 25 kg/m2 (Chin A Paw et al) or below 20 kg/m2 (Rydwik et al) or more, based on self-reported height and weight.

Hennessey et al: PPT, developed by Reuben was used, frail participants were defined as those with PTT score between 12 and 28 of a total possible score of 36.90

Ikeda et al, Kenny et al, Ng et al, Tarazona-Santabalbina et al, and Tieland et al: (Pre)frailty according to the Fried Frailty phenotype.5

Kim et al: Frailty according to CHS-PCF5 with modifications: weight loss of 2–3 kg instead of 5 kg; 1–1.5 kg after 3 months intervention or 1.3–2 kg after 4 months follow-up; Grip strength less than 19 kg; walking speed <1 m/s; low activity: answering “true” to at least 3 of the following 4 statements “I regularly take walks less than once a week,” “I do not exercise regularly,” “I do not actively participate in hobbies or lessons of any sort,” and “I do not participate in any social groups for elderly people or volunteering.”

Kwon et al: Based on CHS-PCF,5 Frailty: lowest 20th percentile on handgrip strength and walking ability among the total participants; Prefrailty: muscle weakness (handgrip strength in lowest quartile at baseline, ≤23 kg) and slow gait speed (lowest quartile of times usual walking speed at baseline, ≤1.52 m/s).

Luger et al: (Pre)frail according to the SHARE-FI.91

Abbreviations: RCT, randomized controlled trial; CCSHA_CFS_TV, Chinese Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale Telephone Version; CHS-PCF, Cardiovascular Health Study Phenotypic Classification of Frailty; BMI, body mass index; PPT, Physical performance test; SHARE-FI, Frailty Instrument for Primary Care of the Survey of health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe.

One study did not report participant setting,55 whereas all others recruited participants living in the community. Three studies included only women.42–44 To select (pre)frail participants, the Fried frailty phenotype criteria were most frequently used (n=8), often modified or in combination with additional criteria.32,42–45,50,54,55 Two studies used the frailty definition of Chin A Paw et al,33,46 one study41 used the physical performance test score of Reuben and Siu,90 and one study examined (pre)frailty by the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe Frailty Instrument for Primary Care (SHARE-FI).53 Studies included only frail,33,42,43,46,54 moderate frail,41 only prefrail,44 or both prefrail and frail phenotypes.32,45,50,53,55

Quality of the study

The total methodological quality scores of the included studies ranged from 16 “moderate”33,41 to 23 “excellent”43 (Table 2). Only six studies prospectively calculated the sample size.43,45,50,53–55 Baseline differences between intervention and control groups were observed in four studies32,46,53,54 and were not reported in one study.41

Table 2.

Methodological quality assessment of the included studies

| Study | Clearly stated aim | Inclusion of consecutive patients | Prospective collection of data | Endpoints appropriate to study aim +ITT | Unbiased assessment of study endpoint(s) | Follow-up period appropriate to study aim | Loss to follow-up <5% | Prospective study size calculation | Adequate control group | Contemporary groups | Baseline equivalence of groups | Adequate statistical analyses | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan et al32: Ex + NuAd + PS | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 19 |

| Chin A Paw et al33: Ex + NuP + NuVM | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| Hennessey et al41: Ex + Hor | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 16 |

| Ikeda et al55 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 |

| Kenny et al42: Ex + Hor + NuVM | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 |

| Kim et al43: Ex + NuP | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 23 |

| Kwon et al44: Ex + NuAd | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

| Luger et al53 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 19 |

| Ng et al45: Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 |

| Rydwik et al46: Ex + NuAd | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 17 |

| Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 19 |

| Tieland et al50: Ex + NuP + NuVM | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

Notes: 0, not reported; 1, reported but inadequate; 2, reported and adequate.

Abbreviation: ITT, intention-to-treat analyses; Ex, exercise intervention; Cog, cognitive intervention; NuVM, nutritional supplementation of vitamins and minerals; NuP, nutritional supplementation of proteins; NuAd, nutritional advise; NuMF, nutritional supplementation of MFGM; MFGM, milk fat globule membrane; PS, problem-solving therapy.

Characteristics of the multi-domain intervention programs

Table 3 summarizes the interventions of the twelve included studies. Nine studies combined two domains in their interventions. Thereof, eight combined a nutritional and physical activity intervention,33,43,44,46,50,53–55 and one combined hormone therapy with physical activity intervention.41 The remaining three studies combined three interventions, of which one study combined exercise, nutritional, and hormone intervention,42 one study combined exercise and nutritional intervention with psychotherapy,32 and one study combined exercise, nutritional, and cognitive interventions.45 All the studies (n=12) included an exercise intervention, and all but one study42 included a strength training component. Three of the twelve studies included an exercise intervention with only a strength training component,41,50,53 whereas the other nine studies included a multicomponent exercise intervention (at least two of following components: endurance and/or strength and/or balance and/or flexibility). All but one study41 included a nutritional intervention: four studies provided nutritional advice,32,44,46,53 seven studies provided nutritional supplementation,33,42,43,45,50,54,55 and one study provided both nutritional advice and supplementation.54 Compliance was reported in nine studies:32,33,42,45,46,50,53–55 compliance to the exercise intervention ranged from 47.3%54 to ≥95%,55 and compliance to the nutritional intervention ranged from 73%46 to 100%.55

Table 3.

Intervention characteristics

| Study | Exercise intervention

|

Nutritional intervention

|

Other intervention

|

Control intervention

|

Compliance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | Frequency | Content | Frequency | Content | Frequency | Content | Frequency | ||

| Chan et al32 | Warm up (brisk walk, stretching major joints and muscles), resistance training, postural control activities, and balance training, cool down (relaxation) Resistance weights: rubber band and water (0.6–1 L); intensity not reported = Ex |

3×/week 60 min | Nutritional consultation: possibility to ask dietary questions, assess dietary compliance = NuAd | During exercise session (3×/week) |

– Problem-solving therapy: solve problems contributing to mood-related conditions, increase self-efficacy – All participants: educational booklet on frailty, healthy diets, exercise protocols, and self-coping strategies |

2×/month problem-solving therapy | Non-Ex and NuAd and non- PS: how much they read the booklet and how well they complied with suggested diet and exercise protocols described in educational booklets | 1×/month | Ex + Nu: 18/55 participants attended at least 50% of the 36 intervention sessions PST: 17/57 completed the 6 courses |

| Chin A Paw et al and de Jong et al33–40 | Warm-up (walking and exercise- to-music routines), skills training (strength training with 450 g wrist and ankle weights, speed, flexibility, coordination, endurance) to perform and sustain motor actions (reaching, throwing, catching, kicking, etc), cool down (stretching and relaxation) Gradually increased intensity: train at intensity between 6 and 8 on a 10-point perceived exertion scale = Ex |

2×/week 45 min | Supplementation: fruit and dairy products enriched with vitamins and minerals at 25%–100% of recommended dietary allowance = NuP + NuVM | 1 fruit and 1 dairy product/day | = PS | Exercise: social program (lectures, social activities, and crafts) Home visit for supply of fresh food products Nutritional: same foods as intervention group but not enriched (= NuP) | 1×/2 weeks 90 min 1×/2 weeks 1 fruit and 1 dairy product/day |

Ex: attendance: 90% (range 47%–100%) Nu: high compliance: percentage of participants with at least one deficiency decreased from 61% to 15% Control: attendance: 80% (range 50%–100%) | |

| Hennessey et al41 | Warm-up, low impact graded resistance training, cool down. Knee extension and ankle dorsiflexion: W1–5: 20%–60% 1 RM; W6–9: 80%–90% 1 RM; W10–17 & W18–25: 60%–95% retested 1 RM Plantar flexion: weights 5%–10% of body weight or quadriceps strength and progress 2%–5% every 2 weeks = Ex |

3×/week 60 min | Growth hormone: rhGH (sc) 0.0025–0.0037 mg/kg = Hor | 1×/day | Hormone: placebo injections | 1×/day | Not reported | ||

| Ikeda et al55 | Muscle strength exercise (intensity: 30% of MVC; 3 sets of 20 repetitions), aerobic exercise (intensity 12 on BRP), balance exercise, cool down = Ex |

2×/week | 6 g Branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) supplementation (1,560 mg BCAA; 1,440 mg essential AA) = NuP | 2×/week within 10 min before exercise | Nutritional: maltodextrin (MD) | 2×/week within 10 min before exercise | Ex: compliance rate ≥95% Nu: compliance rate 100% | ||

| Kenny et al42 | Yoga (Ivengar): breathing exercises, postures focusing on balance and stretching, relaxation; progressive difficulty OR Chair aerobics: commercially available tapes of moderate aerobic effort, increasing difficulty from week 4–6 onwards Intensity not reported = Ex | 2×/week 90 min 2×/week 90 min | All participants: 630 mg calcium and 400 IU cholecalciferol = NuVM | 1×/day | Hormone: 50 mg/day DH EA = Hor | 1×/day | Hormone: placebo | 1×/day | Ex: 73.1%±24.2% adherence DHEA/placebo: 88.9%±22.4% adherence |

| Kim et al43 | Warm-up, progressive strengthening exercises (with Thera bands, increasing repetitions), balance and gait training, cool down Moderate intensity: 12–14 on BRP = Ex |

2×/week 60 min | 6 pills with each 167 mg MFGM (21% protein; 44% fat; 26.5% carbohydrate, 33.3% phospholipids) = NuMF | 1×/day morning | Nutritional: placebo with similar shape, taste and texture but whole milk powder instead of MFGM (26.3% protein; 25.2% fat; 39.5% carbohydrate, 0.286% phospholipids) = NuP | 1×/day morning | Not reported | ||

| Kwon et al44 | Warm up, stretching exercises, exercises aiming to increase muscle strength and balance capability, cool down Strength training: one set of 5 repetitions progressing to 1 set of 10 repetitions = Ex |

1×/week 60 min | – Nutritional education: lecture – Cooking classes: using food ingredient rich in protein and vitamin D = NuAd |

1×/week | General health education session: – Information on physical training for preventing falls and urinary incontinence – Dietary guideline for healthy aging |

1×/month | Not reported | ||

| Luger et al53 | Warm-up and strength training(6 exercises, 2 sets of 15 repetitions until muscular exhaustion) + physical education = Ex |

2(−3) ×/week 30 min | Dietary discussions: how to enrich food with protein, recipes, healthy for life plate = NuAd |

2×/week | Portfolio of possible activities(go out, have a chat, and sharing interests), especially cognitive training | 2×/week | Mean adherence rate for recommended 20 home visits Ex + NuP: 90% (18.0±4.6)Control group: 70%(14.1±5.2) |

||

| Ng et al45 | Strength and balance training. Resistance training integrated with functional tasks Gradually increasing intensity: 1 set of 8–15 RM or 60%–80% of 10 RM, starting with <50% 1 RM. Balance training involving functional strength, sensory input, and added attentional demand = Ex |

2×/week90 min | Supplementation: – Fortisip Multi Fibre(12 g protein) – Iron – Folate – Vit B6, Vit B12 – Calcium and Vit D = NuP + NuVM |

1×/day | Cognition: engage in cognitive-enhancing activities to stimulate short-term memory, enhance attention and information-processing skills, and reasoning and problem-solving abilities = Cog |

First 12 weeks: 1×/week 120 minutes. Subsequent 12 weeks: 1×/2 weeks 120 minutes |

– General: one standard care from health and aged care services – Nutritional: equal volume of artificially sweetened liquid, 2 capsules, and 1 tablet |

1×/day | Mean compliance levels: Ex: 85% NuP + NuVM: 91% Cog: 79% Control: 94% Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog: 88% |

| Rydwik et al46–48 and Lammes et al49 | Warm-up (aerobic training), progressive muscle strength training (W1-2: 60% 1 RM; at W3: 80% 1 RM; 1 RM measurement was repeated at W6 and W10), Qigong balance training, cool down Weights: 10%–20% of body weight = Ex |

2×/week 60 min | – Individual dietary counseling based on baseline food record data – Group session covering topics as nutritional needs for the elderly with serving of well-balanced snack = NuAd |

1× in total 60 min 5 sessions |

General advice regarding physical activity and nutrition for the elderly | Ex: mean compliance rate was 65% (4%–100%) Nu: mean compliance rate was 73% (20%–100%) | |||

| Tarazona- Santabalbina et al54 | Proprioception and balance exercises, aerobic training (initially 40% of maximum heart rate to 65%), strength(initially 25% of 1 RM to 75%), stretching = Ex |

5×/week 65–70 min | Nutritional information of the optimal energy intake, the requirement to ensurea minimal protein intake of 0.8 g/kg body weight. Calcidol levels <30 ng/mL: calcidol loading dose. Supplementation of 1,200 mg calcium and 800 IU calciferol = NuAd + NuVM |

1×/day | Nutritional: identical | 1×/day | Ex: 47.3% (95% CI 38.7%–55.7%) | ||

| Tieland et al50 and Van de Rest et al51 | Warm up, resistance exercises at increasing intensity (50%[10–15 repetitions] – to 75%[8–10 repetitions] of 1 RM).1 RM measurement was repeated after 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 weeks of training = Ex |

2×/week | Supplementation: 250 mL protein supplemented beverage with 15 g protein, 7.1 g lactose, 0.5 g fat, 0.4 g calcium= NuP + NuVM | 2×/day: after breakfast and after lunch | Nutritional: placebo drink without protein, 7.1 g lactose, 0.4 g calcium | 2×/day | Average adherence ≥98% and not different between the groups | ||

Abbreviations: RM, repetition maximum; Vit, vitamin; rhGH, recombinant human growth hormone; sc, subcutaneous; MFGM, milk fat globule membrane; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; CE, conjugated estrogens; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; min, minutes; Hor, hormonal intervention; Ex, exercise intervention; Cog, cognitive intervention; NuVM, nutritional supplementation of vitamins and minerals; NuP, nutritional supplementation of proteins; NuAd, nutritional advise; NuMF, nutritional supplementation of MFGM; PS, problem-solving therapy; BRP, Borg Rate of Perceived Exertion scale; MVC, maximal voluntary contraction; CI, confidence interval; W, week; AA, amino acid.

Impact of the intervention strategies on frailty

Change in frailty status and frailty score

Five studies assessed the impact of a multi-domain intervention on frailty status (frail, prefrail, or robust) and/or frailty score (0–5 points) (Table 4).32,43,45,53,54 Postintervention, four studies found a significantly improved frailty status or score in the multi-domain intervention groups (Ex + NuMF43; Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog45; Ex + NuAd + PS and Ex + NuAd32; Ex + NuAd + NuVM54) compared to mono-domain intervention groups or control group.32,43,45,54 One study found no significant difference on SHARE-FI score between an Ex + NuAd and a social support intervention.53 At 4 months follow-up, in one study, larger significant improvements were maintained in groups with an exercise intervention irrespective of their additional nutritional intervention (Ex + NuMF and Ex + NuP intervention groups compared to NuP for frailty status, and compared to NuP and NuMF for frailty score).43 In another study, participants of the Ex + NuAd (±PS) intervention did not maintain its significant larger improvement of frailty status at 3 months follow-up compared to control or a PS interventions.32 At 6 months follow-up, the multi-domain Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog intervention of Ng et al showed a significantly improved frailty status and score (higher frailty reduction odds ratio compared to control group) compared to the mono-domain interventions.45 Overall, multi-domain interventions showed significantly larger improved frailty status and score in four studies compared to mono-domain or control interventions.32,43,45,54

Table 4.

Frailty outcomes

| Study | Outcome | 3 months before end of intervention | Post-intervention (0 m) | 3–4 m FU | 6 m FU | 9 m FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al43: Ex + NuP/NuMF | Frailty status | / | Ex + NuMF (OR =3.12, CI =1.13; 8.60): significantly improved compared to NuP group | Ex + NuP (OR =3.64, CI =1.12; 11.85) and Ex + NuMF (OR =4.67, CI =1.45; 15.08): significantly improved compared to NuP group | / | / |

| Frailty score | / | / | Ex + NuMF and Ex + NuP: significantly improved** compared to NuP and NuMF | / | / | |

| Ng et al45: Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog | Frailty status | / | / | / / |

Significantly improved compared to control group: – Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog (OR =5.00 [CI =1.88; 13.3])** – Ex (OR =4.05 [CI =1.50; 10.8])** – NuP + NuVM (OR =2.98 [CI =1.10; 8.07])** – Cog (OR =2.89 [CI =1.07; 7.82])** |

/ / |

| Frailty score | Significantly improved compared to control group (mean change = −0.47 [− 0.75; −0.19]): – Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog (mean change = −0.87 [CI = −1.16; −0.59])* – Ex (mean change = −0.98 [CI = −1.26; −0.70])* |

Significantly improved compared to control group (mean change =−0.34 [CI =−0.63; −0.06]): – Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog (mean change =−0.75 [CI =−1.04; −0.47])* – Ex (mean change =−0.92 [CI =−1.20; −0.63])** |

Significantly improved compared to control group (mean change = −0.14 [CI = −0.43; −0.14]): – Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog: (mean change = −0.92 [CI = −1.21; −0.64])** – Ex (mean change = −0.83 [CI = −1.12; −0.54])** – NuP + NuVM: (mean change = −0.63 [CI = −0.92; −0.34])* – Cog (mean change = −0.62 [CI = −0.91; −0.33])* |

|||

| Chan et al32: Ex +NuAd + PS | Frailty status | / | Ex + NuAd + PS and Ex + NuAd (45%): significantly improved** compared to PS or control group (27%) | NS | / | NS |

| Luger et al53: Ex + NuAd | Frailty status | / | NS | / | / | / |

| Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54: Ex + NuAd + NuVM | Frailty score | / | Ex + NuAd + NuVM (FFC: 1.6±0.9) (EFS: 7.7±2.0): significantly improved*** compared to NuAd + NuVM group (FFC: 3.8±0.3) (EFS: 9.3±2.3) | / | / | / |

Notes: Values are (mean ± SD) or (median [10th–90th percentile]) unless otherwise indicated. Frailty score: number of frailty criteria (out of five); frailty status: frail, prefrail, or robust.

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001.

Abbreviations: FFC, Fried frailty criteria; EFS, Edmonton frailty scale; m, months; FU, follow-up; Hor, hormone; Ex, exercise intervention; Cog, cognitive intervention; NuVM, nutritional supplementation of vitamins and minerals; NuP, nutritional supplementation of proteins; NuMF, nutritional supplementation of milk fat globule membrane; PS, psychosocial intervention; NS, no significant difference; /, not available; kg, kilogram; CI, 95% confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Impact of the intervention strategies on the elements of the frailty phenotype

Fried et al5 described frailty in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). More specifically, the Phenotypic Classification of Frailty (CHS-PCF)5 includes five components: unintentional weight loss, weakness, exhaustion, slow gait, and low physical activity.5,6 In the following section, effects of multi-domain interventions in frail elderly on these components are described.

Change in muscle mass (unintentional weight loss)

Seven studies examined muscle mass after a multi-domain intervention (Table 5). First, Tieland et al found that adding a protein and mineral supplementation to an exercise intervention significantly improved appendicular and total muscle mass post-intervention.50 Chin A Paw et al found a significantly improved muscle mass by an exercise intervention combined with a protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation intervention compared to protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation.36 Kenny et al found that adding a hormonal dehydroepiandrosterone intervention to an exercise and vitamin and mineral supplementation increased total (but not appendicular) lean mass post-intervention.42 The other four studies found no significant differences between multi-domain and mono-domain interventions. No significant effect was found of adding a milk fat globule membrane (MFGM) or protein supplementation to an exercise intervention.43 Psychosocial intervention (problem-solving therapy) with or without Ex + NuAd intervention compared to no psychosocial intervention or an Ex + NuAd intervention with or without a PS intervention compared to no Ex + NuAd intervention had also no significant effect on muscle mass.32 Also, the combination of Ex + NuAd did not alter muscle mass significantly compared to Ex or NuAd alone or control group.46 Tarazona-Santabalbina et al found that adding exercise to nutritional advice and vitamin and mineral supplementation intervention did not significantly improve muscle mass.54

Table 5.

Muscle mass

| Study | Outcome and method | 3 months before end of intervention | Post-intervention (0 m) | 4 m FU | 6 m FU | 9 m FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al43: Ex + NuP/NuMF | Appendicular skeletal mass (kg); DXA | / | NS | NS | / | / |

| Tieland et al50: Ex + NuP + NuVM | Lean mass (kg); DXA | / | Treatment × time interactions: Ex + NuP + NuVM: significantly improved compared to Ex group for appendicular*** and total muscle mass** Appendicular muscle mass: Ex + NuP + NuVM: +4.48%; Ex: −1.04% Total muscle mass: Ex + NuP + NuVM: +2.75%; Ex: −0.66% | / | / | / |

| Chin A Paw et al36: Ex + NuP + NuVM | Lean body mass (kg); DXA | / | Ex + NuP + NuVM and Ex (+0.5 kg): significantly improved* compared to NuP + NuVM or control group (−0.1 kg) Ex (0.2±1.4 kg): change (0.47%) significantly improved* compared to control group (−1.18%) (−0.5±1.4 kg) | / | / | / |

| Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54: Ex + NuAd + NuVM | Lean mass (kg); BIA | / | NS | / | / | / |

| Kenny et al42: Ex + NuVM + Hor | Total and regional lean tissue mass (kg); DXA | / | Appendicular skeletal muscle mass: NS; Lean mass: Ex + NuVM + Hor (39.6±6.1 kg): significantly improved* compared to Ex + NuVM (38.1±5.2 kg) | / | / | / |

| Rydwik et al46: Ex + NuAd | FFM (kg); body weight minus fat mass (sum of four skin folds) | / | NS | / | NS | / |

| Chan et al32: Ex + NuAd + PS | FFM (kg); BIA method | / | / | / | / | NS |

Notes: Values are (mean ± SD) or (median [10th–90th percentile]) unless otherwise indicated.

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001.

Abbreviations: DXA, dual X-ray absorptiometry; BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; FFM, fat-free mass; m, months; FU, follow-up; Hor, hormone; Ex, exercise intervention; Cog, cognitive intervention; NuVM, nutritional supplementation of vitamins and minerals; NuP, nutritional supplementation of proteins; NuMF, nutritional supplementation of MFGM; PS, psychosocial intervention; NS, no significant difference; /, not available; kg, kilogram; CI, 95% confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Change in muscle strength (weakness)

Muscle strength was examined in nine studies, combining Ex + NuP,43,55 Ex + NuMF,43 Ex + NuP + NuVM,33,50 Ex + NuAd,44,46 Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog,45 Ex + NuVM + Hor,42 Ex + Hor41 (Table 6). One study found that adding protein supplementation to a strength and balance exercise intervention significantly improved leg press strength and knee extension strength but not for hip abduction strength and rowing.55 Two studies examined the effect of 3 months Ex + NuAd.44,46 Rydwik et al found in both Ex + NuAd and Ex groups a significantly improved lower (compared to NuAd) and upper (elbow) (compared to control group) muscle strength post-intervention, but not in shoulder muscle strength.46 Kwon et al found no significant differences between Ex + NuAd and other intervention groups post-intervention.44 At 6 months follow-up, they found significantly declined muscle strength in the Ex + NuAd group compared to the control group.44 The interventions Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog, Ex alone, and Cog alone showed significantly improved lower muscle strength both post-intervention and at 6 months follow-up compared to the control group.45 Finally, Kenny et al found that adding a hormone intervention to an exercise and vitamin and mineral supplementation significantly improved lower but not upper muscle strength.42 Some studies found no significant differences between multi-domain interventions and mono-domain interventions: there was no significant effect in adding an MFGM (NuMF)43 or protein supplementation (with vitamin/mineral supplementation)50 or hormone intervention41 to an exercise intervention. Chin A Paw et al found no significantly improved muscle strength by an exercise intervention combined with a protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation intervention compared to protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation or by combined exercise and nutritional intervention compared to single exercise or no intervention.33

Table 6.

Muscle strength

| Study | Strength | 3 months before end of intervention | Post-intervention (0 m) | 4 m FU | 6 m FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al43: | Upper | / | NS | NS | / |

| Ex + NuP/NuMF | Lower | / | NS | NS | / |

| Tieland et al50: | Upper | / | NS | / | / |

| Ex + NuP + NuVM | Lower | / | NS | / | / |

| Ikeda et al55: | Upper | / | NS for rowing | / | / |

| Ex + NuP | Lower | / | Ex + NuP: significantly improved leg press rate* (13.9%±36.0%) and knee extension rate** (9.5%±26.3%) compared to Ex: leg press |

/ | / |

| / | rate (2.7%±12.5%) and knee extension rate (−0.8%±18.2%) | ||||

| NS for hip abduction | / | / | |||

| Chin A Paw et al33: | Upper | / | NS | / | / |

| Ex + NuP + NuVM | Lower | / | NS | / | / |

| Rydwik et al46: Ex + NuAd | Upper | / | Ex + NuAd (mean change =1.7 kg [CI =0.04; 3.4]) and Ex (mean change =1.8 kg [CI =0.8; 2.8]): change significantly improved** compared to control group (mean change =−1.1 kg [CI =−3.2; 0.9]) in elbow but | / | NS |

| Lower | / | NS in shoulder Ex + NuAd (mean change =9 kg [CI =1.8; 16.2]) and Ex (mean change =11.9 kg [CI =6.3; 17.5]): change significantly improved** compared to NuAd (mean change =−2.4 kg [CI =−7.9; 3.2]) |

/ | NS | |

| Kwon et al44: Ex + NuAd | Upper | / | Ex + NuAd: NS Ex (2.3±3.1 kg) significantly improved** compared to control group (0.4±2.6 kg) |

/ | Ex: NS Ex + NuAd (−2.1±5.0 kg) significantly declined** compared to control group (0.1 ±2.4 kg) |

| Ng et al45: Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog | Lower | NS | Significantly improved change compared to control group (mean change =0.02 kg [CI =−1.08; 1.12]) – Cog** (mean change =2.18 kg [CI =1.08; 3.27]) – Ex** (mean change =2.75 kg [CI =1.66; 3.83]) – Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog** (mean change =2.67 kg [CI =1.58; 3.76]) |

/ | Significantly improved change compared to control group (mean change = −0.24 kg [CI = −1.34; 0.87]) – Cog** (mean change =1.98 kg [CI =0.87; 3.09]) – Ex* (mean change =1.41 kg [CI =0.31; 2.51]) – Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog** (mean change =2.35 kg [CI =1.25; 3.44]) |

| Kenny et al42: Ex + NuVM + Hor | Upper Lower |

/ / |

NS Ex + NuVM + Hor (484±147 N): significantly improved* compared to Ex + NuVM (447±128 N) |

/ / |

/ / |

| Hennessey et al41: Ex + Hor | Lower | / | Hor** (P=0.007) and Ex*** (P<0.0005) significantly improved strength compared to control group | / | / |

Notes: Values are (mean ± SD) or (median [10th–90th percentile]) unless otherwise indicated.

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001.

Abbreviations: DXA, dual X-ray absorptiometry; BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; FFM, fat-free mass; m, months; FU, follow-up; Hor, hormone; Ex, exercise intervention; Cog, cognitive intervention; NuVM, nutritional supplementation of vitamins and minerals; NuP, nutritional supplementation of proteins; NuMF, nutritional supplementation of MFGM; PS, psychosocial intervention; NS, no significant difference; /, not available; kg, kilogram; CI, 95% confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Exhaustion

The exhaustion component of the phenotypical frailty definition cannot be covered in the “Results” section as none of the included articles described the effect of multi-domain interventions on exhaustion.

Gait speed (slow gait)

Seven studies measured gait speed (Table 7A). Overall, two studies found more improved gait speed in multi-domain interventions including exercise.33,43 Kim et al found that adding an exercise intervention to NuMF supplementation improved gait speed.43 Chin A Paw et al found significant improvements on gait speed by an exercise intervention with protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation intervention compared to protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation.33 Adding nutritional advice or protein supplementation to an exercise intervention showed no significant effect on gait speed, compared to exercise intervention alone.44,46,50 Also, adding a hormone intervention to a vitamin and mineral supplementation and exercise intervention showed no significant effect for gait speed.42 No significant between-group effects were found post-intervention by Ex + Cog + NuVM + NuP intervention compared to single-domain interventions.45

Table 7.

Gait speed and physical activity

| Study | 3 months before end of intervention | Post-intervention (0 m) | 3–4 m FU | 6 m FU | 9 m FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Gait speed (m/s) | |||||

| Kim et al43-: Ex + NuP/NuMF | / | Ex + NuMF (% change =14.7±4.1) (CI =6.4; 23.1): change significantly improved* compared to NuMF (% change =2.1±1.9) (CI =−1.8; 5.9) or NuP (% change =3.6±2.7) (CI =−1.9; 9.1) | NS | / | / |

| Tieland et al50: Ex + NuP + NuVM | / | NS | / | / | / |

| Rydwik et al46: Ex + NuAd | / | NS | / | NS | / |

| Kwon et al44: Ex + NuAd | / | NS | / | NS | / |

| Chin A Paw et al33: Ex + NuP + NuVM | / | Ex + NuP + NuVM or Ex (0.06±0.1): significantly improved** compared to NuP + NuVM or control group (0.0±0.04) | / | / | / |

| Kenny et al42: Ex + NuVM + Hor | / | NS | / | / | / |

| Ng et al45: Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog | NS | NS | / | NS | / |

| B: Physical activity | |||||

| Kenny et al42: Ex + NuVM + Hor | / | NS | / | / | / |

| Rydwik et al47: Ex + NuAd | / | Ex and Ex + NuAd: change significantly improved* compared to control group | / | Ex: change significantly improved* compared to control group or NuAd | / |

| Ng et al45: Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog | NS | NuP + NuVM (mean change =96.2 [CI =57.8; 134.7]): change significantly improved** compared to control group (mean change =20.5 [CI =−17.0; 58.1]) | / | NuP + NuVM (mean change =110.1 [CI =71.9; 148.2]): significantly improved** compared to control group (mean change =34.8 [CI =−2.99; 72.6]) | / |

| Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54: Ex + NuAd + NuVM | / | Ex + NuAd + NuVM (485.6±98.1): significantly improved*** compared to NuAd + NuVM group (265.8±46.1) | / | / | / |

| Ikeda et al55: Ex + NuP | / | NS | / | / | / |

Notes: Values are (mean ± SD) or (median [10th–90th percentile]) unless otherwise indicated.

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001.

Abbreviations: m, months; FU, follow-up; Hor, hormone; Ex, exercise intervention; Cog, cognitive intervention; NuVM, nutritional supplementation of vitamins and minerals; NuP, nutritional supplementation of proteins; NuMF, nutritional supplementation of milk fat globule membrane; PS, psychosocial intervention; NS, no significant difference; /, not available; kg, kilogram; CI, 95% confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Physical activity level (low physical activity)

Five studies examined the effect of the intervention on physical activity level (Table 7B). Adding an exercise intervention to a nutritional advice and vitamin and mineral supplementation increased physical activity.54 Another study found significantly increased physical activity by a NuP + NuVM intervention compared to the control group post-intervention and at 6 months follow-up.45 Physical activity was also increased by Ex intervention alone or Ex combined with NuAd post-intervention and at 6 months follow-up; this increase remained in the Ex group compared to NuAd or control group.47 Kenny et al and Ikeda et al found no significant effect on physical activity of adding a hormone intervention to exercise and nutritional vitamin and mineral supplementation42 and adding a protein supplementation to exercise intervention,55 respectively.

Impact of the intervention strategies on the consequences of frailty

Change in functional abilities

Four studies examined the effect of multi-domain interventions on functional abilities (Table 8A). Functional abilities are described by activities of daily living (ADL) and/or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and/or personal activities of daily living dependency or scores. There was a significant improved effect on ADL and IADL by adding an exercise intervention to a nutritional advice and vitamin and mineral supplementation intervention.54 No significant differences were found between a PS intervention (problem-solving therapy) with or without Ex + NuAd intervention compared to no psychosocial intervention or between an Ex + NuAd intervention with or without a PS intervention compared to no Ex + NuAd intervention,32 or between an exercise intervention with protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation intervention compared to protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation or between a combined exercise and nutritional intervention compared to a single exercise or no intervention33 or between Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog compared to Ex or NuP + NuVM or Cog.45

Table 8.

Functional abilities and physical functioning

| Study | 3 months before end of intervention | Post-intervention (0 m) | 3–4 m FU | 6 m FU | 9 m FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Functional abilities (ADL/IADL/PADL) | |||||

| Ng et al45: Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog | NS | NS | / | NS | / |

| NS | NS | / | NS | / | |

| Chan et al32: Ex + NuAd + PS | / | NS | NS | / | NS |

| Chin A Paw et al33: Ex + NuP + NuVM | / | NS | / | / | / |

| Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54: Ex + NuAd + NuVM | / | ADL: Ex + NuAd + NuVM (91.6±8.0): significantly improved*** compared to NuAd + NuVM group (82.0±11.0) IADL: Ex + NuAd + NuVM (6.9±0.9): significantly improved*** compared to NuAd + NuVM group (5.7±2.0) |

/ | / | / |

| B: Physical functioning | |||||

| SPPB Tieland et al50: Ex + NuP + NuVM |

/ | NS | / | / | / |

| SPPB Kenny et al42: Ex + NuVM + Hor |

/ | Ex + NuVM + Hor (10.7±1.9): significantly improved* compared to Ex + NuVM (10.1±1.8) | / | / | / |

| SPPB Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54: Ex + NuAd + NuVM |

/ | Ex + NuAd + NuVM (9.5±1.8): significantly improved** compared to NuAd + NuVM group (7.1±2.8) | / | / | / |

| PPT Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54: Ex + NuAd + NuVM |

/ | Ex + NuAd + NuVM (23.5±5.9): significantly improved*** compared to NuAd + NuVM group (16.5±5.1) | / | / | / |

| Tinetti Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54: Ex + NuAd + NuVM |

/ | Ex + NuAd + NuVM (24.5±4.4): significantly improved** compared to NuAd + NuVM group (21.7±4.5) | / | / | / |

| Performance score Chin A Paw et al33: Ex + NuP + NuVM |

/ | Ex and Ex + NuP + NuVM significantly improved*** compared to NuP + NuVM or control group | / | / | / |

| Fitness score Chin A Paw et al33: Ex + NuP + NuVM33 |

/ | NS: Ex and Ex + NuP NuVM NS different compared to NuP + NuVM or control group | / | / | / |

Notes: Values are (mean ± SD) or (median [10th–90th percentile]) unless otherwise indicated.

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001.

Abbreviations: FU, follow-up; TUG, timed up and go test; Hor, hormone; Ex, exercise intervention; Cog, cognitive intervention; NuVM, nutritional supplementation of vitamins and minerals; NuP, nutritional supplementation of proteins; PS, psychosocial intervention; NS, no significant difference; /, not available; s, seconds; CI, 95% confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Change in physical functioning

Three studies examined physical functioning by the short physical performance test (SPPB) (Table 8B).42,50,54 Moreover, Tarazona-Santabalbina et al also assessed the physical performance test and Tinetti balance and gait score.54 The study of Chin A Paw et al assessed performance score and fitness score.33 There was a significant beneficial effect on physical functioning of adding a hormone intervention to a vitamin and mineral supplementation and exercise intervention,42 adding an exercise intervention to a nutritional advice and vitamin and mineral supplementation intervention,54 and of an exercise intervention with protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation intervention compared to protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation on performance score but not fitness score.33 Adding a protein, vitamin, and mineral supplementation to an exercise intervention did not show improvements.50

Other frequently described outcomes including cognitive function, muscle power, gait ability, balance, functional lower extremity strength, and falls are described in detail in Tables 9–11.

Table 9.

Muscle power

| Study | Post-intervention (0 m) | 3 m FU | 9 m FU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chan et al32: Ex + NuAd + PS | NS | Ex + NuAD + PS and PS (2.71±6.08 kg): significantly improved* change compared to Ex + NuAd or control group (0.18±6.68 kg) | Ex + NuAD + PS and PS (−3.52±9.65 kg): significantly improved* change compared to Ex + NuAd or control group (−7.14±8.74 kg) |

| Kenny et al42: Ex + NuVM + Hor | NS | / | / |

Notes: Values are (mean ± SD) or (median [10th–90th percentile]) unless otherwise indicated.

P<0.05.

Abbreviations: m, months; FU, follow-up; Hor, hormone; Ex, exercise intervention; NuVM, nutritional supplementation of vitamins and minerals; PS, psychosocial intervention; NS, no significant difference; /, not available; kg, kilogram; SD, standard deviation.

Table 10.

Gait ability, balance, functional lower extremity strength, falls

| Study | 3 months before end of intervention | Post-intervention (0 m) | 3–4 m FU | 6 m FU | 9 m FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Gait ability (TUG) | |||||

| Kim et al43: Ex + NuP/NuMF | / | Ex + NuMF (% change =−14.4±2.0) (CI =−13.8; −9.9) and Ex + NuP (% change =−18.5±2.1) (CI =−22.9; −14.0): change significantly improved*** compared to NuMF (% change =−6.1±2.6) (CI =−11.6; −0.7) or NuP (% change =−3.0±2.6) (CI =−8.3; 2.3) |

NS | / | / |

| Rydwik et al46: Ex + NuAd | / | NS | / | NS | / |

| Kenny et al42: Ex + NuVM + Hor | / | NS | / | / | / |

| Ikeda et al55: Ex + NuP | / | NS | / | / | / |

| B: Balance | |||||

| Dynamic balance | |||||

| Rydwik et al46: Ex + NuAd | / / |

NS (modified figure eight) Ex + NuAd (mean change =−1.1 [CI =−3.2; 1]): score step test significantly decreased* compared to Ex (mean change =3.2 [CI =0.9; 5.5]) |

/ / |

NS NS |

/ / |

| Ikeda et al55: Ex + NuP | / | Ex + NuP: functional reach test improvement rate significantly improved* (11.0%±22.0%) compared to Ex (1.0%±17.0%) | / | / | / |

| Static balance | |||||

| Chan et al32: Ex + NuAd + PS | / | NS (single leg stance) | NS | / | NS |

| Kenny et al42: Ex + Hor + NuVM | / | NS (singe leg stance) | / | / | / |

| Rydwik et al46: Ex + NuAd | / | NS (tandem stance) | / | NS | / |

| / | NS (single leg stance) | / | NS | / | |

| Kwon et al44: Ex + NuAd | / | NS (stork stance) | / | NS | / |

| Chin A Paw et al33: Ex + NuP + NuVM | / | NS (tandem stance) | / | / | / |

| / | Ex + NuP + NuVM and Ex (4 [−7; 17]): change in score for balancing on balance board significantly improved* compared to NuP + NuVM and control group: (2 [−12; 13]) | / | / | / | |

| Dynamic and static balance | |||||

| Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54: Ex + NuAd + NuVM | NS (Tinetti balance index) | / | / | / | |

| C: Functional lower extremity strength | |||||

| Rydwik et al46: Ex + NuAd | / | NS | / | NS | / |

| Chin A Paw et al33: Ex + NuP + NuVM | / | Ex + NuP + NuVM and Ex (−2.3 s for chair stand [−7.7; 1.4]): change significantly improved* compared to NuP + NuVM and control group (−1.0 s for chair stand [−6.4; 3.8]) | / | / | / |

| Kenny et al42: Ex + Hor + NuVM | / | NS | / | / | / |

| Tieland et al50: Ex + NuP + NuVM | / | NS | / | / | / |

| D: Falls | |||||

| Ng et al45: Ex + NuP + NuVM + Cog | NS | NS | / | NS | / |

| Tarazona-Santabalbina et al54: Ex + NuAd + NuVM | / | NS | / | / | / |

Notes: Values are (mean ± SD) or (median [10th–90th percentile]) unless otherwise indicated.

P<0.05;

P<0.001.

Abbreviations: FU, follow-up; SPPB, short physical performance test; PPT, physical performance test; Hor, hormone; Ex, exercise intervention; Cog, cognitive intervention; NuVM, nutritional supplementation of vitamins and minerals; NuP, nutritional supplementation of proteins; NuMF, nutritional supplementation of milk fat globule membrane; PS, psychosocial intervention; NS, no significant difference; /, not available; s, seconds; CI, 95% confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Table 11.

Cognitive status

| Study | Post-intervention (0 m) |

|---|---|

| van de Rest51: Ex + NuP + NuVM | Episodic memory: NS |

| Attention and working memory: NS | |

| Information processing speed* Ex + NuP + NuVM (0.08±0.51): change significantly improved compared to | |

| NuP + NuVM (-0.23±0.19) | |

| Executive functioning: NS |

Notes: Values are (mean ± SD) or (median [10th–90th percentile]) unless otherwise indicated.

P<0.05.

Abbreviations: Ex, exercise intervention; NuVM, nutritional supplementation of vitamins and minerals; NuP, nutritional supplementation of proteins; NS, no significant difference; SD, standard deviation.

Table S2 summarizes the secondary outcomes quality of life, social involvement, psychosocial well-being/depression, and subjective health.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

Mono-domain nonpharmacological interventions such as physical exercise have shown beneficial effects for frail elderly on gait speed, physical functioning,17 mobility, falls, functional abilities, muscle strength, body composition, and frailty.56 However, no systematic reviews exist on the effectiveness of multi-domain interventions, nor the contribution of a mono-domain intervention to a multi-domain intervention. This systematic review included twelve studies investigating the effect of a multi-domain intervention in frail elderly on frailty status and score, cognition, muscle mass strength and power, and functional, emotional, and social outcomes. These studies were heterogeneous in terms of included participants (frailty diagnostic tool), intervention strategies (type of interventions, number of interventions, and combinations of interventions), and intervention duration. Overall, multi-domain interventions show a greater beneficial impact compared to mono-domain interventions (eg, nutritional intervention alone) or usual care for frailty characteristics, physical functioning, and muscle mass and strength. To be more specific, physical exercise seems to play an essential role in the multi-domain intervention, with some improvements by an additional intervention (eg, nutritional intervention). As suggested in previous reviews, the positive effects of nutritional supplementation increase when associated with physical exercise and the positive effects of physical exercise increase when associated with nutritional supplementation.22,57–59 Also, it could be claimed that the physical exercise component accounts for the greatest improvements, which has also been suggested in reviews discussing frail28 and sarcopenic elderly.22

Multi-domain interventions improve frailty characteristics and physical functioning more effectively than mono-domain interventions

Overall, this review indicates that multi-domain interventions are more effective than mono-domain interventions for several outcomes, such as frailty status or score. More specifically, the combination of physical exercise and nutritional intervention yielded a more positive result on frailty status or score compared to a nutritional intervention43,45,54 or a physical exercise intervention.45 This effect was not found consistently and probably partly depends on variables such as the type and frequency of intervention and target group. The impact of physical exercise on frailty characteristics was previously described.29 It is now of particular interest to mark the added value of the combination of an exercise and nutritional intervention, underlining the contribution of the nutritional intervention to frailty improvements. Moreover, this positive effect on frailty seems to be more prolonged in multi-domain compared to mono-domain interventions. These observations underpin the inherent characteristics of the frailty syndrome: a system-wide syndrome that demands a system-wide approach.

Besides frailty status and score, multi-domain interventions also improved physical functioning (eg, SPPB) more effectively compared to a nutritional intervention,33,54 a combined exercise and nutritional intervention42 or no intervention.33 This is plausible as multiple interventions can act on multiple levels of physical functioning and therefore affect the score of a multifaceted test. Although there is a tendency for improved results by multi-domain interventions, particularly the combination of an exercise and nutritional intervention,33,43,46 the effects were less conclusive for the individual components of the physical functioning test (gait speed, gait ability, balance, and functional lower extremity strength).

Muscle mass and strength showed a tendency to be improved more effectively by multi-domain compared to mono-domain interventions. These results were previously described in reviews in sarcopenic populations.22,57 More specifically, the combined physical exercise and nutritional intervention showed a tendency to improve muscle mass and muscle strength more than exercise or nutritional intervention alone. Skeletal muscle strength does not solely depend on muscle mass but is a function of multiple factors such as nutritional, hormonal, and neurological components and physical activity.60,61 Therefore, it is plausible that the combination of two or more of these interventions will add to the intervention efficacy. In addition, the results seemed to be more consistent when the intervention duration was at least 4 months.33,42,50

The beneficial effects of an exercise intervention alone on frailty,62 muscle outcomes,63 physical functioning,17 quality of life,64 depression,65 and cognition66 have been described extensively. Although this review did not focus on single-domain interventions, it was observed that the exercise intervention on its own consistently contributed to the core effects on frailty, muscle mass, and muscle strength.33,44–46 Therefore, the role of the exercise intervention seems primordial as part of a multi-domain intervention. Exercise program characteristics (frequency, intensity, duration, and type of training) influence its effects and must therefore be optimized. According to the recent literature, an optimal exercise intervention for frail elderly is performed at least three times a week with progressive moderate intensity for 30–45 minutes per session and for a duration of at least 5 months. The optimal type of exercise intervention is a multicomponent intervention covering aerobic exercise, strength training, balance, and flexibility67,68 but depends on the outcome that must be improved. The content of the exercise interventions in the different studies in this review is diverse, including several interventions with insufficient training stimulus, for example, training only once a week.44 Exercise interventions with a clear insufficient dose or intensity of training cannot be expected to have an effect, for example, on muscle strength.

The additional effect of combining physical exercise with a nutritional intervention is frequently observed, however not consistently. One argument could be that due to the energy and protein deficits as a consequence of the malnutrition of the participants, the effect of the nutritional intervention is suboptimal because the nutrients are first used to resolve these energy and protein deficits. Malnutrition is often present in community-dwelling elderly;69 moreover, frail elderly have lower intakes of energy, protein, and/or several micronutrients compared to non-frail elderly.70,71 Malnutrition is a result of several factors including anabolic resistance. Anabolic resistance is an aging-associated resistance in response to the positive effects of dietary protein on protein synthesis that elderly develop.72 Several mechanisms underlie anabolic resistance such as splanchnic sequestration of amino acids, decreased postprandial availability of amino acids, and decreased muscle uptake of dietary amino acids.72 Protein intake combined with exercise could increase the anabolic stimulus of exercise. However, due to the anabolic resistance and to obtain beneficial effects of exercise interventions, frail elderly need larger protein intakes. Similarly, physical exercise improves muscle sensitivity to protein or amino acid uptake, consequently counteracting anabolic resistance. Furthermore, the quality and quantity of the nutritional intervention must be emphasized: with insufficient protein intake, an additional effect compared to the exercise intervention alone cannot be expected, similar as when the exercise stimulus is insufficient. Guidelines recommend an intake of 1.2–1.5 g protein/kg bodyweight/day for frail elderly. In addition, each meal should contain 20–40 g protein in order to stimulate muscle protein synthesis in the elderly.73–76 Therefore, nutritional supplementation to reach this threshold must include an assessment of the daily protein intake of the participants. This was done in only one study included in this review.50 As a result, nutritional interventions may be inadequate and results may be misinterpreted. This could lead to an underestimation of the value of nutritional supplementation. To exclude this argument in future, it is important 1) to implement nutritional interventions tailored to the nutritional intake and habits of the participants or 2) to restore the participant’s nutritional status both before the start and during the intervention.

Nutritional status can be targeted directly by adding proteins or nutrients to the diet or indirectly by advising the participant about the importance of several nutrients and how to add them to the diet. Nutritional interventions in this review were heterogeneous in terms of content (NuAd, NuP, NuVM, and NuMF) and design (daily, once a month), resulting in variability in effects. Therefore, no reliable conclusions regarding the stronger intervention can be drawn. To all intents and purposes, direct nutritional supplementation can be advised to achieve direct effects on nutritional status, moreover, higher protein intake was associated with less likelihood of being frail (based on Fried criteria).77 However, teaching the participant to evaluate and adapt his/her own nutritional intake will improve the sustainability of the effect and the compliance to the intervention.

In conclusion, multi-domain interventions, where both exercise and nutritional interventions are optimally designed, reveal a stronger effect as frailty, physical functioning, and muscle mass and strength depend on multiple factors. As a result, we recommend the exercise intervention as an essential part of future multi-domain intervention studies. Moreover, attention must be paid to the design of both exercise and nutritional interventions to elucidate the optimal effect of the interventions. In addition, the compliance of the participants to the interventions is of crucial importance. In turn, compliance to the exercise intervention is influenced by the supervision on and location of the intervention.

Inconsistent effects on functional abilities, falls, and psychosocial outcomes

No consistent effects of multi-domain interventions on functional abilities, falls or quality of life, psychosocial behavior, or depression were found. However, beneficial effects may have been missed due to a low number of studies examining these outcomes or insufficient power, as several studies did not do a proper sample size calculation for these outcomes or did not include these outcomes as primary outcomes. Previous studies describe improved functional abilities by an exercise intervention but underline the importance that the intervention exercises are functional and task specific (eg, exercising chair rises) in order to improve functional abilities.78,79 Furthermore, recent systematic reviews found conflicting results of the effect of physical activity on quality of life: one review described no consistent effect in elderly with mobility problems, physical disability, and/or multi-morbidity,80 whereas another review described a positive and consistent association in elderly.81

Methodological considerations

Multiple studies were excluded during the study selection, mainly because the authors did not report outcomes stratified by interventions, for example, the Frailty Intervention Trial by Cameron et al.82 These studies, often reporting interdisciplinary team-based approaches, assess affected domains by a comprehensive geriatric assessment and thereafter tailor the treatment to the goals, capacity, and context of the individual.20 As authors did not discriminate between intervention combinations, the interpretability of the effectiveness of the intervention components is inherently impossible.83 The exclusion of these types of articles confines the scope of this review, which was considered reasonable given the goal of the review.

Thanks to the assistance of an expert librarian in the citation, reference and author search, and the inclusion of studies reported in four languages; this review considerably reduced the risk for selection bias. Although the study selection based on title and abstract was done by one reviewer, all relevant articles should have been retrieved as this step was thoroughly performed and in case of doubt, the full article was read and discussed with a second reviewer.

Methodological quality of the included studies ranged from medium to high scores. This indicates that the observed effects are not likely to be overestimated. Moreover, as almost all studies performed poorly with regard to the prospective calculation of the study sample size, the likelihood of type II errors increases, meaning that some nonsignificant results may be falsely considered as nonsignificant. This problem should be addressed in future studies, improving overall study quality.

As the primary focus of this review is to determine the effect of different multi-domain interventions, effects over time within one intervention group were not covered and will not be discussed further. Recent reviews can be consulted for a literature review of these over time effects (eg, Denison et al22).

Remaining and upcoming questions and challenges for future studies

Several questions remain, due to the limited number of studies. First, intervention effects on cognition, social involvement, or some functional outcomes remain unclear, as well as the contribution of several mono-domain interventions (eg, hormonal intervention). Therefore, they should be a focus of future research. Second, the optimal duration of intervention to obtain the effects on frailty status or physical functioning could not be derived due to too small number of studies. Similarly, the persistence of the achieved effects is difficult to discuss as only five studies included follow-up measurements in their study. Third, more studies should examine the ability of the interventions to prevent or treat frailty, as considerable literature describes that multi-domain interventions have this potential.13,16 Essentially, researchers are encouraged to investigate their results from a broader perspective. A core outcome set for these types of studies consisting of following measures is suggested: 1) frailty status, score, and/or characteristics; 2) muscle outcomes (mass and strength); 3) physical outcomes (at least functional abilities and one physical functioning test); 4) cognition, social outcomes, and/or psychological well-being.

In addition, new questions arise. First, heterogeneous populations are considered as (pre)frail elderly as a broad spectrum of frailty screening tools is used in research and clinical practice. Not only were different frailty definitions used, also considerable variety was observed within one type of definition, challenging the generalizability of the intervention. Ultimately, the development of a well-accepted opera-tionalized frailty screening tool will improve homogeneity in study populations and will contribute to the understanding of the results. Second, following questions arise: “What is the optimal moment to tackle frailty by an intervention (preventive or in early pre-frailty stage)?” and “How can participants be motivated to adhere to the intervention program (personal characteristics, program factors, environmental factors)?”

Conclusion

These limited but promising data highlight the potential of the physical exercise component as a standard intervention component, optimally combined with at least a nutritional intervention. Hereby, adequate design of interventions will improve results. Multi-domain interventions were found to be more effective than mono-domain interventions for improving frailty status and physical functioning. Also, a multi-domain intervention tended to yield more positive outcomes for muscle mass and strength. Eventually, understanding the contribution of each mono-domain intervention would pave the way to optimize and prioritize the frailty syndrome management. Finally, diverse frailty definitions cause heterogeneous study populations and urge the development of an overall accepted operationalized frailty definition.

Acknowledgments

Marleen Michels participated in the database search. All authors agreed to publish the paper. Funding for this systematic review was provided by internal funding of the University of Leuven, KU Leuven.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferrucci L, et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(6):991–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gielen E, Verschueren S, O’Neill TW, et al. Musculoskeletal frailty: a geriatric syndrome at the core of fracture occurrence in older age. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012;91(3):161–177. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouillon K, Kivimaki M, Hamer M, et al. Measures of frailty in population-based studies: an overview. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abellan van Kan G, Rolland Y, Houles M, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Soto M, Vellas B. The assessment of frailty in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(2):275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried L, Tangen C, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol. 2001;56A(3):M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sternberg SA, Schwartz AW, Karunananthan S, Bergman H, Clarfield AM. The identification of frailty: a systematic literature review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2129–2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):722–727. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulminski AM, Ukraintseva SV, Kulminskaya IV, Arbeev KG, Land KC, Yashin AI. Cumulative deficits better characterize susceptibility to death in the elderly than phenotypic frailty: lessons from the cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):898–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizzoli R, Reginster J-Y, Arnal J-F, et al. Quality of life in sarcopenia and frailty. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;93(2):101–120. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9758-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirven N, Rapp T. The cost of frailty in France. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(2):243–253. [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Commission . Multidimensional Aspects of Population Ageing. Population Ageing in Europe: Facts, Implications and Policies: Outcomes of EU-funded Research. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X, Mao G, Leng SX. Frailty syndrome: an overview. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:433–441. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S45300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, Han L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(4):418–423. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xue QL. The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron ID, Fairhall N, Gill L, et al. Developing interventions for frailty. Adv Geriatr. 2015;2015:7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gine-Garriga M, Roque-Figuls M, Coll-Planas L, Sitja-Rabert M, Salva A. Physical exercise interventions for improving performance-based measures of physical function in community-dwelling, frail older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(4):753.e3–769.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]