Summary

Synthetic and collateral lethality have provided conceptual frameworks to identify cancer-specific vulnerabilities1–3. Here, we explored an approach to identify potential synthetic lethal interactions through screening mutually exclusive deletion patterns in cancer genomes. We sought to identify ‘synthetic essential’ genes, which might be occasionally deleted in some cancers but almost always retained in the context of a specific tumor suppressor deficiency, and posited that such synthetic essential genes would be therapeutic targets in cancers harboring specific tumor suppressor deficiencies. In addition to known synthetic lethal interactions, this approach uncovered the chromatin helicase DNA-binding factor CHD1 as a putative synthetic essential gene in PTEN-deleted cancers. In PTEN-deleted prostate and breast cancers, functional analysis showed that CHD1 depletion profoundly and specifically suppressed cell proliferation, survival and tumorigenic potential. Mechanistically, functional PTEN stimulates GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation of CHD1 degron domains, which promotes CHD1 degradation via β-TrCP-mediated ubiquitination-proteasome pathway. Conversely, PTEN deficiency results in CHD1 protein stabilization, which in turn engages the H3K4me3 mark to activate transcription of the pro-tumorigenic TNFα/NF-κB gene network. Together, this study identifies a novel PTEN pathway in cancer and provides a framework for the discovery of trackable targets in cancers harboring specific tumor suppressor deficiencies.

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second leading cause of cancer death for men in the United States, with 220,800 new cases and 27,540 deaths annually (NCI SEER 2015). Up to 70% of primary prostate tumors show loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the PTEN locus4. In mouse models, prostate-specific Pten deletion (Ptenpc−/−) results in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) that may progress to high-grade adenocarcinoma after a long latency5, a pattern consistent with loss of PTEN as a key initiation event in PCa development. To date, therapeutic targeting of the PTEN-PI3K-AKT pathway has yielded meager clinical benefit, prompting continued effort to identify obligate effectors of this important pathway in order to illuminate effective therapeutic targets for PTEN-deficient cancers.

The notion of targeting synthetic lethal vulnerabilities in cancer has been validated in the treatment of cancers harboring specific loss-of-function mutations1,6. One celebrated example is the effectiveness of poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in BRCA deficient tumors2,7. More recently, collateral lethality has emerged as another target discovery strategy for cancers harboring tumor suppressor gene deletions that also delete neighboring genes encoding functionally redundant essential activities thereby creating cancer-specific vulnerabilities3,8. Genomic analyses have also been helpful in establishing functional interactions of components in specific pathways that show mutually exclusive patterns of genomic alterations. Such epistatic patterns include components of the RB or p53 pathways, where alterations in one gene of the pathway typically alleviates genetic pressure to alter another driver in the same pathway consistent with minimal additional selective advantage to the cancer cell9,10.

Taking advantage of the vast publically available cancer genome database, we sought to establish and validate an approach to identify potential synthetic lethality interactions in cancer via screening for mutually exclusive deletion patterns in the cancer genome. More specifically, we searched for genes that might occasionally be deleted in some cancers (i.e., a non-essential gene) but always retained in the context of deletion of a specific tumor suppressor, reasoning that the retained gene might be required for executing the cancer promoting actions in the context of a specific tumor suppressor deficiency (i.e., a ‘synthetic essential’ gene). By extension, we posited that inhibition of such synthetic essential genes would impair the survival and tumorigenic potential of cancer cells harboring the specific tumor suppressor deficiency. Here, we focused on PCa due to the frequent and early deletion of the PTEN tumor suppressor and the paucity of actionable ‘oncogene’ targets in PCa.

The well-established synthetic lethal interaction of BRCA1/PARP1 provides a measure of validation for our approach since a mutually exclusive deletion pattern of BRCA1 and PARP1 is readily observed in the PCa TCGA database (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Along similar lines, and consistent with preclinical and clinical studies suggesting PTEN-deficiency sensitizes prostate, colorectal and endometrial cancer cells to PARP inhibitors11,12, we observed a synthetic essential relationship between PTEN and PARP1 (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Another mutually exclusive deletion pattern in PCa points to an interaction between PTEN and polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4) (Extended Data Fig. 1b). This observation aligns well with the single-agent antitumor activity of the PLK4 inhibitor, CFI-400945 and its capacity to induce significant regression of PTEN-deficient cancers, compared with PTEN-intact cancer cells13. Together, these circumstantial data prompted us to speculate that druggable essential dependencies (synthetic essential genes) of specific tumor suppressor gene deficiencies might be uncovered by scanning the patterns of cancer genome deletions.

Large-scale genomic analyses of the TCGA and other PCa databases identified CHD1 (5q21 locus) as a locus that is deleted in some human PCa cases (7–10%)14–16 yet consistently retained in PTEN-deleted PCa (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1c). Additionally, the significant mutually exclusive pattern with PTEN deletion was only observed with CHD1 but not other CHD homologues (Extended Data Fig. 1d). The PTEN/CHD1 relationship was reinforced by a strong negative correlation between CHD1 and PTEN expression in 127 prostatic hyperplasia and cancer TMA samples by immunohistochemistry analysis (P=0.001, Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 2a–b). CHD1 deletion per se does not appear to play a significant role in PCa development as suggested by the lack of neoplasia in a tissue recombinant model using mouse prostate epithelial progenitor/stem cells with CHD1 deletion17. Rather, CHD1 expression correlates positively with a high Gleason Grade (p=0.006, Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 2c) and is increased in neoplastic Pten-deleted murine prostatic epithelium compared to wild type controls (Extended Data Fig. 2d–e). Collectively, these observations prompted us to consider the possibility that CHD1 may be required for the progression of PCa driven by loss of PTEN.

Figure 1. Knockdown of CHD1 inhibits tumor growth of PTEN-null prostate cancer (PCa).

(a) Genomic alterations of CHD1 and the PTEN-AKT pathway in TCGA PCa database (N=333)16. (b) Representative images of CHD1 expression, and the negative correlation between CHD1 and PTEN expression in human prostatic hyperplasia and cancer samples (N=127). Staining magnification: 40x. (c) Distribution of CHD1 expression in human PCa samples with different Gleason Grades (N=90). Pearson correlation coefficient and two-tailed p value are shown. (d) Immunoblots of lysates and colony formation assays generated from CHD1 knockdown and control PC-3 cells. (e) Measurement of subcutaneous tumor growth of CHD1 knockdown and control PC-3 cells. Control N=10; shCHD1#2 N=10; shCHD1#4 N=8. (f) Representative images of Ki67 staining of subcutaneous tumor tissues generated from (e). Scale bar: 50 μm. (g) Measurement of subcutaneous tumor growth of CHD1 knockdown PTEN-intact or -deficient DU145 cells. PTEN KO shCHD1 N=5; other groups N=6 for each. Error bars in (e, g) indicate standard deviation (S.D.). P values were determined by two-tailed t-test. N.S.: not significant.

To test the above hypothesis, shRNA-mediated depletion or CRISPR-directed nullizygous mutation of CHD1 was performed in 4 PTEN deficient PCa cell lines (shRNA: human LNCaP and PC-3 PCa cell lines, and mouse Pten/Smad4-null and PtenCaP8 PCa cell lines; CRISPR: human LNCaP cell line). In these models, CHD1 suppression inhibited colony formation and induced cell death (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 2f–j), yet had minimal impact on cell migration (Extended Data Fig. 2k). Moreover, CHD1 depletion attenuated tumor growth of PC-3 and LNCaP in vivo (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 2l–m) and, correspondingly, these tumors exhibited a striking reduction in cell proliferation (Ki67) and increase in apoptosis (Caspase-3) (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 2n). Similarly, administration of siCHD1 in established PTEN-deficient patient-derived xenograft (PDX) tumors attenuated tumor progression (Extended Data Fig. 2o–p). However, CHD1 depletion had minimal impact on colony formation or tumor growth of the PTEN-intact PCa cell lines- 22Rv1, RWPE-2 and DU145 (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 3a–d). In sharp contrast, CRISPR-mediated knockout of PTEN in DU145 cells sensitized these cells to CHD1 depletion both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 3c–d). Together, these data support the view that CHD1 is a synthetic essential gene required for tumor growth of PTEN-null PCa, – a functional relationship consistent with the mutually exclusive pattern of PTEN and CHD1 deletions.

Exploration of the functional relationship between PTEN and CHD1 revealed that PTEN re-expression in PTEN-null PCa cell lines led to a significant decrease in CHD1 protein, but not mRNA, levels (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 3e). Correspondingly, transient ectopic expression of GFP-PTEN suppressed CHD1 in PC-3 cells at the single cell level (Fig. 2b). Time course studies revealed that AKT inhibitor (MK2206) treatment reduced CHD1 protein levels over a 6-hour period (Fig. 2c) and that PTEN re-expression reduced the half-life of CHD1 protein (Extended Data Fig. 3f), supporting a role for the PTEN-AKT axis in the control of CHD1 protein levels. Moreover, compared to PTEN-intact cells, CHD1 was observed to be more stable in PTEN-deficient cells (Extended Data Fig. 3f–h). To explore the mechanisms governing CHD1 protein levels, we treated the PTEN wild-type benign prostatic hyperplasia epithelial cell line, BPH1, with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, resulting in marked accumulation of CHD1 in a time dependent manner (Fig. 3a). Moreover, endogenous CHD1 was modified by ubiquitination (Extended Data Fig. 4a), and PTEN over-expression dramatically enhanced CHD1 ubiquitination (Fig. 3b). Together, these data raise the possibility that CHD1 degradation is controlled via the ubiquitination-proteasome pathway in a PTEN-dependent manner.

Figure 2. PTEN inhibits CHD1 by decreasing its protein stability.

(a) Immunoblots of lysates generated from human PC-3 and LNCaP cells overexpressing PTEN. (b) Co-staining of CHD1 and PTEN by immunofluorescence in PC-3 cells overexpressing GFP-PTEN. The yellow arrows indicate GFP-PTEN negative cells. Scale bar: 100 μm. (c) Immunoblot of CHD1 protein in LNCaP cells treated with 2μM AKT inhibitor (MK2206). pAKT: phosphorylation of AKT at Ser473.

Figure 3. PTEN promotes CHD1 degradation through SCFβ-TrCP mediated ubiquitination-proteasome pathway.

(a) Detection of CHD1 in BPH1 cells treated with 10μM MG132 (HIF-1α as positive control). (b) PTEN and HA-Ub were transfected, followed by 8h MG132 treatment and immunoprecipitation (IP) of endogenous CHD1. CHD1 and HA were detected by immunoblot. (c) Schematic diagram of two β-TrCP binding motifs (DSGXXS) in CHD1. (d) Co-IP using CHD1 antibody, followed by detection of β-TrCP via immunoblot. (e) Immunoblot of CHD1 in 293T cells overexpressing Flag-tagged β-TrCP (Yap and IKBα as positive control). (f) Flag-tagged β-TrCP and HA-Ub were transfected; endogenous CHD1 was immunoprecipitated and CHD1 ubiquitination was detected. (g) HA-tagged WT and constitutively active mutant (S9A) GSK3β were transfected into LNCaP cells, and phospho- and unphospho-CHD1 proteins were separated using Phos-tag gel by immunoblot. Total CHD1 protein as loading control; C-Myc as positive control. (h) Immunoblot of CHD1 in LNCaP cells transfected with HA-tagged GSK3β. β-actin as loading control. (i) HA-Ub was transfected, followed by 2μM CHIR (24h) and 10μM MG132 (8h) treatment and detection of CHD1-ubiquitination by IP-immunoblot.

To identify a specific E3 ligase governing CHD1 protein stability, consensus sequence scanning of multiple E3 ligase interaction domains revealed two evolutionarily conserved putative β-TrCP consensus-binding motifs (DSGXXS) at the N-terminal of CHD1- residues 23–28 (motif 1, DSGSAS) and 53–58 (motif 2, DSGSES) (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 4b). β-TrCP is an F-box protein, and acts as the substrate recognition subunit for the SCFβ-TrCP (Skp1-Cullin1-F-box protein) E3 ubiquitin ligases, which mediate the ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of various substrates including β-catenin, Yap and IKB, among others18–20. The CHD1-β-TrCP link was fortified by documentation of the endogenous interaction of CHD1 and β-TrCP using co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 3d) and by β-TrCP over-expression resulting in reduced CHD1 protein levels and enhanced CHD1 ubiquitination (Fig. 3e–f and Extended Data Fig. 4c). Conversely, shRNA-mediated depletion of β-TrCP caused CHD1 accumulation and inhibited its ubiquitination (Extended Data Fig. 4d–e). To investigate whether the β-TrCP binding motifs of CHD1 were indeed involved in the regulation of CHD1 protein stability, wild-type V5-tagged CHD1 and two β-TrCP binding motif mutants (DAGXXA) were introduced into BPH1 cells, followed by analyses of CHD1 half-life, ubiquitination and β-TrCP interaction. These experiments established that the motif 2 (DSGSES) serves as the major β-TrCP binding motif that contributes to CHD1 ubiquitination and degradation (Extended Data Fig. 4f–h).

β-TrCP is known to specifically recognize and interact with phosphorylated substrates21. Our analysis of CHD1 identified that both β-TrCP binding motifs harbor a GSK3β consensus sequence-SXXXS (Extended Data Fig. 4i). Since GSK3β is a direct target of AKT kinase and is inhibited upon AKT activation, it would be anticipated that PTEN loss would impair GSK3β, resulting in decreased CHD1 phosphorylation and subsequent ubiquitination. In line with this possibility, overexpression of GSK3β and its constitutively active mutant (S9A) in LNCaP cells increased phosphorylation of CHD1 (Fig. 3g), consistent with the role of GSK3β as a CHD1 kinase. This connection was reinforced by documented endogenous interaction between GSK3β and CHD1 (Extended Data Fig. 4j) as well as decreased CHD1 levels with enforced expression of GSK3β (Fig. 3h). Finally, treatment with CHIR, an inhibitor of GSK3β, decreased CHD1 ubiquitination (Fig. 3i) and blocked the negative effect of PTEN expression on CHD1 protein stability (Extended Data Fig. 4k). Together, these data establish that the PTEN-AKT-GSK3β pathway regulates CHD1 degradation via the β-TrCP-mediated ubiquitination-proteasome pathway.

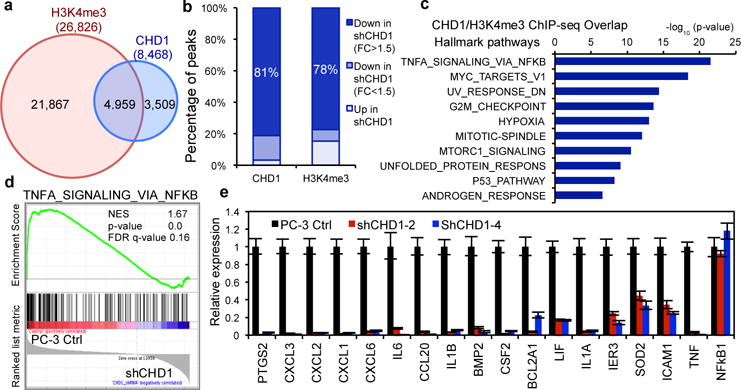

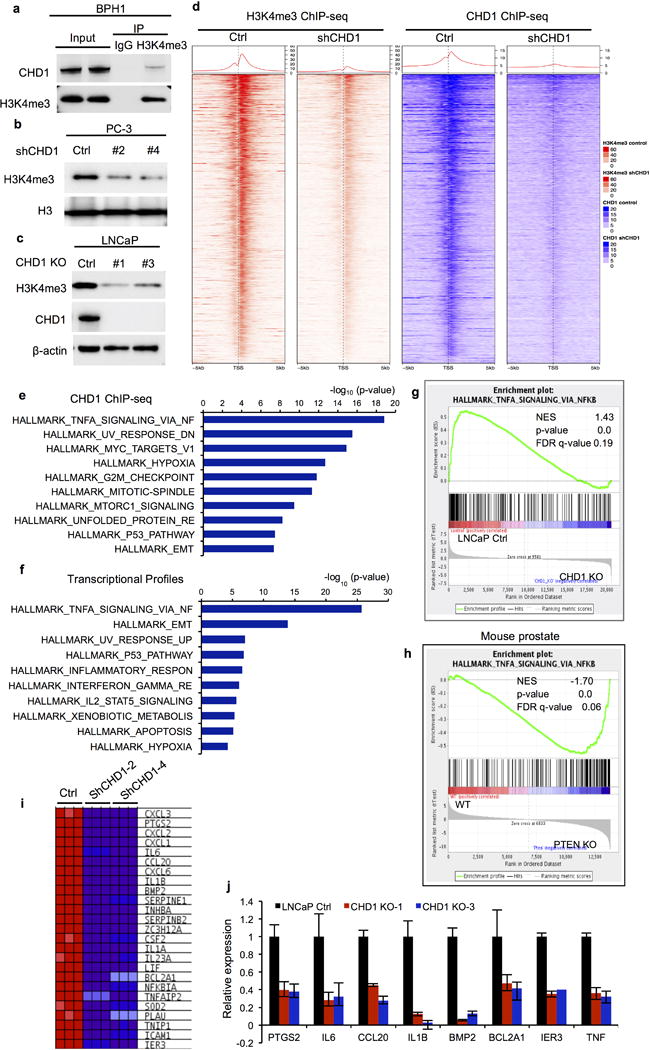

Trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) is known to be associated with transcriptional activation, and CHD1 is known to selectively recognize and bind to H3K4me3 to activate gene transcription22. In addition, CHD1 is involved in the maintenance of open chromatin and cooperates with H3K4me3 to control pluripotency of murine embryonic stem cells23. Correspondingly, co-IP studies in BPH1 cells confirmed that CHD1 binds to H3K4me3 (Extended Data Fig. 5a) and CHD1 depletion in LNCaP and PC-3 cells revealed a significant reduction in the H3K4me3 mark (Extended Data Fig. 5b–c). To determine the downstream transcriptional targets and pathways of CHD1 and H3K4me3 in PTEN-null PCa cells, ChIP-seq was performed in control versus CHD1 knockdown PC-3 cells. ChIP-seq identified a total of 8,468 CHD1-binding sites and 26,826 H3K4me3-enriched regions in control PC-3 cells, with 58.6% of CHD1 peaks overlapping with H3K4me3 peaks (Fig. 4a). Confirming our experimental methodology, 81.4% of CHD1 binding sites showed reduced peak values in CHD1-depleted PC-3 cells (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 5d). And, notably, 77.5% of H3K4me3 enriched regions’ peak values concomitantly diminished in CHD1-depleted PC-3 cells as well (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 5d), strongly supporting an unanticipated role for CHD1 in H3K4me3 maintenance in PCa. In addition, pathway analysis of either the concomitantly regulated genes by CHD1/H3K4me3 or the genes whose promoters are bound by CHD1 revealed a significant enrichment of genes involved in the TNFα/NF-κB network (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 5e; Supplemental Table 1–2).

Figure 4. CHD1 collaborates with H3K4me3 to activate gene transcription in the NF-κB pathway in PTEN-deficient PCa.

(a) Venn diagrams showing the overlap of peak sets identified from the duplicate-merged CHD1 and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq in PC-3 cells. Blue cycle: CHD1 peaks; Red cycle: H3K4me3 peaks. (b) Percentage of decreased CHD1 or H3K4me3 ChIP-seq peaks in CHD1 knockdown PC-3 cells. (c) Top 10 Hallmark pathways showing enrichment of CHD1 and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq overlap genes. 50 MSigDB Hallmark pathways emerged following IPA “Core Analysis”. Graph displays category scores as –log10 (p-value) from Fisher’s exact test. (d) GSEA correlation of NF-κB signature with alternatively expressed genes in CHD1 knockdown PC-3 cells. Normalized Enrichment Score (NES), Nominal p-value and FDR q-value of correlation are shown. (e) Validation of CHD1 regulating genes in CHD1 knockdown PC-3 cells using qRT-PCR. Error bars represent ± S.D. of triplicated experiments.

Next, microarray analysis was performed in CHD1-depleted PC-3 and LNCaP cells (Supplemental Table 3–4). These expression profiles aligned with the above ChIP-seq data, confirming TNFα/NF-κB as the top down-regulated hallmark pathway in CHD1-depleted cells (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 5f–g). Among the Top 30 down-regulated genes in shCHD1 PC-3, 10 were target genes of NF-κB (Extended Data Table 1). Notably, pathway enrichment analysis uncovered that the TNFα/NF-κB pathway is activated in PTEN null mouse prostate tissue (Extended Data Fig. 5h), suggesting that TNFα/NF-κB network regulation is linked to the PTEN-CHD1 axis.

NF-κB is a key regulator of inflammation and plays important roles on PCa initiation and progression24. Blockade of NF-κB alone or in combination with anti-androgen suppresses the tumor growth and metastasis of PCa25,26. Those down-regulated genes in the TNFα/NF-κB pathway identified by microarray analysis included genes that control tumor cell proliferation (PTGS2/COX-2) and anti-apoptosis (IER3, BCL2 and SOD2), as well as multiple cytokines that remodel the tumor microenvironment (CXCLs, IL1 and IL6)24 (Extended Data Fig. 5i). These gene expression results were further validated by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4h and Extended Data Fig. 5j) and, upon analysis of clinical samples in the TCGA PCa database, expression of these TNFα/NF-κB pathway genes correlated positively with CHD1 expression (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Interestingly, although many direct target genes of NF-κB were identified, we did not observe changes in total or activated NF-κB p65 when CHD1 was depleted (Extended Data Fig. 6b and Fig. 4h). Based on CHD1/H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data, all 90 down-regulated genes in the TNFα/NF-κB pathway can be subdivided into three categories: (a) genes bound by CHD1 and marked by H3K4me3 (41.1%), consistent with direct transcriptional control of these genes by CHD1 presumably via its interaction with the H3K4me3 mark; (b) genes not bound by CHD1 but showing decreased H3K4me3 enrichment upon CHD1 depletion (47.8%), possibly reflecting CHD1-directed maintenance of H3K4me3 mark which activates target transcription; and (c) genes neither bound by CHD1 nor marked by H3K4me3 (~10%), suggesting that they are indirectly regulated by CHD1 and H4K4me3 (Extended Data Fig. 6c and Table 2). Thus, the majority (88.9%) of down-regulated TNFα/NF-κB pathway genes are transcriptionally controlled by CHD1 directly or via its maintenance of the H3K4me3 mark. Finally, consistent with PTEN-CHD1-NF-κB pathway epistasis, enforced addition of several CHD1 target genes, such as PTGS2 (PGE2), BMP2 and CSF2, rescued colony formation in PCa cells deficient for both PTEN and CHD1 (Extended Data Fig. 6d).

Together, our data demonstrate that the epigenetic regulator CHD1 represents a prime therapeutic target candidate in PTEN-deficient PCa, validating our in silico approach to identifying synthetic essential genes. Furthermore, our study identified a novel PTEN pathway linking PTEN and chromatin-mediated regulation of the cancer-relevant NF-κB network. Specifically, mechanistic analyses identified PTEN → AKT → GSK3β → β-TrCP-mediated degradation of CHD1 via the ubiquitination-proteasome process (Extended Data Fig. 7a). In cancer, PTEN deficiency stabilizes CHD1, which engages and maintains the H3K4me3 mark to activate cancer promoting gene expression including the NF-κB network, which is known to promote PCa progression (Extended Data Fig. 7b). In addition to PCa, the mutually exclusive deletion pattern of PTEN and CHD1 is also present in breast and colorectal adenocarcinoma (Extended Data Fig. 7c). To evaluate potential roles for CHD1 in breast cancer, shRNA-mediated depletion was introduced into two PTEN-deficient (BT-549 and MDA-MB-468) and two PTEN-intact (MDA-MB-231 and T47D) breast cancer cell lines. Consistent with the observation in PCa, suppression of CHD1 inhibited PTEN-deficient breast cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth (Extended Data Fig. 7d–f), but had minimal impact on PTEN-intact breast cancer cells (Extended Data Fig. 7g–h). One caveat concerning CHD1 is its potential role as a key driver of carcinogenesis in some cancer types regardless of PTEN status. In such cancers, one would expect consistent retention of CHD1 across genotypes.

Finally, we explored the generality of the ‘synthetic essentiality’ concept. To that end, we searched in silico for additional examples of candidate synthetic essential genes that might serve an obligate role in effecting carcinogenesis and tumor maintenance. Analysis of the PCa TCGA database revealed a number of additional candidates that are rarely deleted but typically show increased expression in the context of a specific tumor suppressor gene alteration, such as PTEN, TP53, SMAD4 and RB1 (Extended Data Table 3). Previous studies have shown that inhibiting these putative synthetic essential genes could reduce cell proliferation or lead to tumor regression in PCa and other cancer types, indicating their potential roles in synthetic lethal interaction with putative tumor suppressors in a given cancer type. Further functional analyses will be needed to verify synthetic essentiality of these genes in cancer cells harboring specific tumor suppressor deficiencies, as well as to determine potential regulatory interactions and cell essential mechanisms.

Although most synthetic lethal interactions often involve two genes in parallel pathways that converge on the same essential biological process (e.g., convergence of BRCA and PARP on DNA repair processes), the PTEN/CHD1 example indicates that genetic interactions can also reside between components in the same pathway and that, in the case of the synthetic essential gene CHD1, such genes can serve as an essential downstream effector for a specific tumor suppressor gene deficiency. Together, our study provides a framework for the discovery of targetable vulnerabilities in cancers harboring specific tumor suppressor deficiencies.

Methods

Cell culture and transfection

Prostate cancer cell line PC-3 was cultured in Ham’s F-10 Nutrient Mixture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Prostate cancer cell line LNCaP, 22Rv1 and benign prostatic hyperplasia epithelial cell line BPH-1 were cultured with Gibco RPMI 1640 Medium (RPMI) with 10% FBS. BPH1 was kindly provided by Dr. Simon W. Hayward. Prostate cancer cell line DU145 was cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium with 10% FBS. Mouse prostate cancer derived cell line PtenSmad4 3132 (Ptenpc−/−Smad4pc−/−) was generated in 2010 as described previously27, and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS. Prostate cancer cell lines RWPE-2 and PtenCaP8 were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, 25 μg/mL bovine pituitary extract (BPE), 5 μg/mL bovine insulin and 6 ng/mL human recombinant EGF. Breast cancer cell lines BT-549 and MDA-MB-468 were cultured with RPMI with 10% FBS; and T47D were cultured with RPMI with 10% FBS and 5 μg/mL bovine insulin. MDA-MB-231 and 293T cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. All cell lines were purchased from ATCC, confirmed to be mycoplasma-free, and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. All human cell lines have been validated through fingerprinting by the MD Anderson Cell Line Core Facility.

All transient transfections of plasmids and siRNA into cell lines followed the standard protocol for Lipofectamine 2000™ Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher, #11668019). Two siRNA oligos targeting β-TrCP were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (SASI_Hs01_00189438 and 00189439).

shRNA knockdown of CHD1

We screened 7 hairpins targeting human CHD1 and found two independent sequences that reduced protein levels by >70%. These hairpins were in the pLKO.1 vector (shCHD1 #2 and #4). The human CHD1 shRNA sequences are as follows:

-

shCHD1 #2: NM_001270.2

CCGGGCGGTTTATCAAGAGCTATAACTCGAGTTATAGCTCTTGATAAACCGCTTTTT

-

shCHD1 #4: NM_001270.2

CCGGGCGCAGTAGAAGTAGGAGATACTCGAGTATCTCCTACTTCTACTGCGCTTTTT

In addition, we screened 5 hairpins targeting mouse CHD1 and identified 2 that reduced protein levels by >60%. These hairpins were in the pLKO.1 vector (shChd1 #1 and #2). The mouse Chd1 shRNA sequences are as follows:

-

shChd1 #1: NM_007690

CCGGTCCGAGCACACACATCATAAACTCGAGTTTATGATGTGTGTGCTCGGATTTTTG

-

shChd1 #2: NM_007690

CCGGGCCAGGAGACATACAGTATTTCTCGAGAAATACTGTATGTCTCCTGGCTTTTTG

Recombinant lentiviral particles were produced by transient transfection of 293T cells. Briefly, 8 μg of the shRNA plasmid, 4 μg of psPAX2 plasmid, and 2 μg of pMD2.G plasmid were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 into 293T cells plated in 100 mm dishes. Viral supernatant was collected 48 h and 72 h after transfection and filtered. Cells were infected twice in 48 h with viral supernatant containing 10 μg/mL polybrene, and then selected using 2 μg/mL puromycin and tested for CHD1 expression by immunoblot.

Knockout using CRISPR

sgRNA targeting human CHD1 were designed using the Broad Institute sgRNA Designer (http://www.broadinstitute.org/rnai/public/analysis-tools/sgrna-design), and cloned into pX330-Cherry vector individually. The CHD1 sgRNA sequences are as follows:

sgCHD1_#1F: CACCGGACGCATCATCAGACCAAA

sgCHD1_#3F: CACCGTCAGCTCCATCAACTTTCGG

The plasmids with sgRNA were transiently transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were harvested 72 h later, and 10 cherry-positive cells were sorted by flow cytometry into each well of a 96-well plate, followed by determination of CHD1 protein by immunoblot. PCR-sequencing was also performed using genomic DNA extracted from CHD1-deficient single clones to identify genetic alteration at the CHD1 allele. Finally, we chose the single clone, in which one or more premature stop codons were introduced in coding exons by sgRNA-induced mutations. sgRNA-plasmid targeting human PTEN was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-400103), and a similar process was performed to generate the PTEN knockout DU145 cell line.

Concerning reviewer’s comments “restoration of PTEN to ‘rescue’ the lethality of CHD1 knockout”, re-expression of PTEN in PTEN-deficient cancer cells provoked proliferative arrest and apoptosis, given that PTEN regulates many hallmarks of cancer.

Cell proliferation assays and apoptosis analysis

Cell proliferation was assayed either through colony-formation or cell number counting. For colony formation assay, 5×103 or 1×104 cells were seeded in each well of 6-well plates and cultured for 5–7 days. At the end point, cells were fixed and stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 25% methanol for 1 h. For cell number counting, 5×103 cells were seeded in each well of 6-well plates for each time point. At the indicated time point, cells were counted using Countess II FL automated cell counter (Invitrogen). For apoptosis analysis, cells were stained with Annexin V PE and DAPI, and evaluated by flow cytometry according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Biovision).

Xenograft prostate or breast cancer model

The in vivo tumor growth of human prostate or breast cancer cells transduced with non-targeting hairpin or shCHD1 was determined using a subcutaneous transplant xenograft model. Cancer cells (2 × 106) in PBS/Matrigel mixture were injected subcutaneously into 5-week old male nude mice (Taconic) or NOD/SCID mice (Charles River) under deep anesthesia. The sizes of resulting tumors were measured twice a week. Once the largest tumor diameter reached the maximal tumor diameter allowed under our institutional protocol, all mice were sacrificed and tumors were harvested and weighed. For patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model, a PTEN-deficient PDX line (MDA-PCa-183, generated by Dr. Nora M. Navone28) was selected from 7 candidates through detecting PTEN expression and pAKT levels in tumor lysate by immunoblot. Patient-derived tumor fragments (3–4mm3) were surgically xenografted under the skin of male SCID mice. When tumors reached approximately 100 mm3, mice were assigned randomly into one of two treatment groups. Each tumor was treated weekly (3 times total) with 12 μg control siRNA or siRNA targeting CHD1 using MaxSuppressor™ In Vivo RNA-LANCEr II (Bioo Scientific, #3410-01) following the standard protocol. Tumor volume was measured before first treatment (start point) and 3 days after third treatment (end point). Both negative siRNA control (#VC30002) and human CHD1 siRNA (SASI_Hs02_00331472; 00203194; 00203195) were HPLC purified and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All mouse experiments were performed with the approval of the MD Anderson Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) under protocol number 1069. The maximal tumor diameter allowed by IACUC is 1.5cm.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Immunoblot

For CHD1-IP, cells were lysed in a NP-40 buffer containing 50mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150mM NaCl, 0.3% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell lysates (500 μl) were incubated with anti-CHD1 antibody (Cell signaling #4351S) or control IgG overnight at 4°C. Magnetic or agarose beads (10μl, Novex, # 10003D) were added to each sample. After 3 h, the beads were washed three times with NP-40 buffer, followed by immunoblot. For V5-IP, cell lysates were incubated with anti-V5-tag mAb-Magnetic beads (MBL International, #M167-9) for 3 h at 4°C. For ubiquitination assay, 48h after transfection, cells were lysed in 1% SDS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) and boiled for 15 min, followed by dilution of 5-fold in 50mM Tris-HCl buffer and IP. Proteins were blotted following standard protocol. Antibodies specific for CHD1 (Cell Signaling, #4351S), PTEN (Cell Signaling, #9188S), S473P-AKT (Cell Signaling, #3787S), β-TrCP (Cell Signaling, #4394S), H3K4me3 (Cell Signaling, #9751S), Flag (Sigma, #F7425), HA (Santa Cruz, #sc-7392), GSK3β (Cell Signaling, #12456P), and β-actin (Sigma, #A3854) were purchased. Phos-tag SDS PAGE (Wako Chemicals, SuperSep™ Phos-tag™, #192-17401) was used to detect phosphorylation of CHD1 following the standard protocol.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Immunofluorescence (IF)

Eighty cases of human prostate hyperplasia and cancer samples were purchased from US Biomax (PR807b) and the rest of the samples were acquired from the Prostate Tissue Bank of MD Anderson Cancer Center (total N=127). IHC was performed as previously described27. A pressure cooker (95°C 30 min followed by 120°C 10 sec) was used for antigen retrieval using Antigen unmarking solution (Vector Laboratories). Antibodies specific to CHD1 (Sigma, #HPA022236) and PTEN (Cell Signaling, #9188S) were purchased. The human tissue sections were reviewed and scored in a blinded manner for staining intensity 0–2 by a pathologist, Dr. Wenting Liao. For CHD1, high expression means a staining score of 2, while low expression includes both staining scores 0 and 1. Slides were scanned using Pannoramic 250 Flash III (3DHISTECH Ltd.) and images were captured through Pannoramic Viewer software (3DHISTECH Ltd.). The procedures related to human specimens were approved by MD Anderson’s Institutional Review Board under protocol number #PA14-0420; human samples were obtained from MD Anderson tissue banks which consented the patients for tissue collection for research purposes. PC-3 cells were infected with GFP-PTEN lentiviral particles for 72 h, fixed and stained using CHD1 antibody (Sigma, #HPA022236) following the standard protocol. Images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMi8).

Migration assay

Prostate cancer cells (1×104) were suspended in serum-free culture medium, and seeded into 24-well Transwell® Inserts (8.0 μm). Medium with serum was added to the remaining receiver wells. After 24 h, the inside of each insert was gently swabbed, and crystal violet solution was added for 1 hour staining.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq)

ChIP was performed as described29. Briefly, chromatin from formaldehyde-fixed cells (control and CHD1 knockdown PC-3 cells, 10 ×106 cells for CHD1 antibody and 1×106 cells for H3K4me3 antibody) were cross-linked using 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes and reactions were quenched by 0.125 M glycine for 5 minutes at room temperature. Cells were lysed with ChIP lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.2% SDS, 0.1% deoxycholic acid) for 30 minutes on ice. Chromatin fragmentation was performed using a Diagenode Bioruptor®Pico sonicator (30 secs on and 30 secs off for 45 cycles) to achieve a DNA shear length of 200 to 500 basepairs. Solubilized chromatin was then incubated overnight with their respective antibody-Dynabead (Life Technologies) mixture (CHD1 antibody: Bethyl, #A301-218A; H3K4me3 antibody: Abcam #ab8580). Immune complexes were then washed 3 times with RIPA buffer, once with RIPA-500 (RIPA with 500 mM NaCl), and once with LiCl wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 250 mM LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid). Elution and reverse crosslinking were performed in direct elution buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 5 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS) with proteinase K (20 mg/ml) at 65°C overnight. Eluted DNA was purified using AMPure beads (Beckman-Coulter). Libraries were prepared using NEBNext Ultra DNA Library kit (E7370). Sequencing was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument to generate a dataset GSE91401. Reads were aligned to reference genome (hg 19) using BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner). Reads mapping to more than two genomic loci were ignored.

mRNA Expression Analysis and Microarray

Cells were lysed in TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen; #15596-026), followed by total RNA isolation using the standard protocol. The RNA was further purified using RNeasy (QIAGEN) according to manufacturer’s protocols, and reverse transcribed into cDNA using the SuperScript® III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Quantitative Real-time PCR was performed for target gene expression analysis using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and indicated primers as listed in Supplemental Table 5. Microarray analysis was performed on RNA prepared from control and CHD1 knockdown PC-3 or CHD1 knockout LNCaP cells (biological triplicates for control and each CHD1 shRNA or CHD1 KO) at the MD Anderson Microarray Core facility using the GeneChip® Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix) to generate a dataset GSE84970. Differentially expressed genes between control and CHD1 depleted groups were subjected to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). The GSE25140 dataset of wild-type and Pten deletion mouse prostate tissues was downloaded from the NCBI GEO database repository, published in 201127. The raw data were processed and analyzed by GenePattern using Expression File Creator Module (version 12.3) and GSEA module (v17). The default GSEA basic parameters were used and t test was used as the metric for ranking genes.

Computational Analysis of Human Prostate TCGA Data

A list of 60 down-regulated genes (fold change >2) in the TNFα/NF-κB pathway identified by microarray analysis was generated as Extended Data Table 2. The mRNA expression z-Scores of each gene in 498 TCGA prostate cancer samples were downloaded from http://www.cbioportal.org. The two-tailed Pearson correlations between CHD1 expression and indicated genes were calculated using SPSS Statistics software (IBM), and p values were determined by two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. The gene list was then ranked by Pearson’s correlation with CHD1 expression. The heat map was generated using Microsoft Excel Graded Color Scale function with a 3-color scale set at number of −1, 0, and 1. For the analysis of mutual exclusiveness and gene expression listed in Extended Data Table 3, the genetic alteration and gene expression of 332 TCGA PCa samples with mRNA, CNA and sequencing data were downloaded from http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/runs/stddata__2016_01_28/data/PRAD/20160128/ and analyzed. Odds ratio score was calculated to indicate mutual exclusiveness between Gene A and Gene B deletion. The mean values of Gene B expression in all 332 samples and that in Gene A deleted samples were calculated, and p values were determined by two-tailed student t test.

Statistics

Images of genomic alterations in TCGA database were captured from http://www.cbioportal.org. Estimations of sample size were done taking into consideration previous experience with animal strains, assay sensitivity and tissue collection methodology used. The two-tailed Pearson correlation between CHD1 and PTEN or Gleason grades was calculated using SPSS Statistics software (IBM), and P values were determined by two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. The Student t test assuming two-tailed distributions was used to calculate statistical significance between groups (GraphPad Prism 6 or Microsoft Excel). N represents biological replicates. Error bars indicate standard deviation (S.D.). The P values shown in tumor growth plot indicate the differences of tumor sizes at end-point. * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001. For IPA analysis, we included all 50 “hallmark” gene sets of the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) as described30 as customized pathways. Then the gene fold-change list generated from Microarray (Supplemental Table 3) or the peak-score list generated from ChIP (Supplemental Table 1 or 2) was uploaded for IPA Core Analysis. The filter threshold of microarray data was Fold changes (Ctrl vs. shCHD1) >1.5.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Mutually exclusive deletion patterns in prostate cancer genome.

Genetic alterations of (a) BRCA1/PARP1, (b) PTEN/PARP1 and PTEN/PLK4, (c) CHD1/PTEN, and (d) PTEN/CHD homologues in PCa databases. The gene alteration percentages are shown.

Extended Data Figure 2. Inhibiting CHD1 suppresses tumor growth of PTEN-null prostate cancer (PCa).

(a) Representative images of PTEN staining (Scores 0–2). Staining magnification: 40x. (b) The negative correlation between CHD1 and PTEN staining in human PCa samples was analyzed by two-tailed Pearson correlation coefficient. (c) The correlation between CHD1 staining and Gleason Grade in human PCa samples was analyzed by two-tailed Pearson correlation coefficient. (d-e) Representative CHD1 staining and immunoblots of lysates of prostate tissues of wild-type and prostate-specific Pten deletion mice (Ptenpc−/−). AP: Anterior prostate; DLP: Dorsal lateral prostate; VP: Ventral prostate. Scale bar: 50 μm. pAKT indicates phosphorylation of AKT at Ser473. (f) Immunoblots of lysates generated from CHD1 knockout and control LNCaP cells. Cell proliferation was determined by counting cell numbers in triplicate wells. (g) CHD1 knockout and control LNCaP cells were stained with Annexin V PE and DAPI, and cell apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry. (h-j) Immunoblots of lysates and colony formation assays generated from CHD1 knockdown and control LNCaP cells, PtenSmad4 3132 cells (a mouse prostate cancer cell line generated from the Pten/Smad4 co-deletion prostate cancer mouse model) or PtenCap8 cells (a mouse prostate cancer cell line generated from the Pten deletion prostate cancer mouse model). (k) Representative migration images of CHD1 knockdown and control PC-3 cells determined by transwell assay. (l) Measurement of subcutaneous tumor weight of CHD1 knockdown and control PC-3 cells. (N=10 for both control and shCHD1 #2 groups; N=8 for shCHD1 #4 group). (m) Measurement of subcutaneous tumor growth of CHD1 knockdown and control LNCaP cells. (N=10 for both control and shCHD1 #2 groups; N=8 for shCHD1 #4 group). (n) Representative images and quantification of CHD1 and Caspase-3 staining in subcutaneous tumor tissues generated by CHD1 knockdown and control PC-3 cells (N=4). Scale bar: 50 μm. (o) Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model mice were treated by siRNA targeting CHD1 at 3 time points (40μg/tumor/time). Fold changes of tumor volume are shown (siCtrl group N=6; siCHD1 group N=7). (p) Representative images and quantification of CHD1 staining of xenograft tumor tissues generated from (o) (N=4). PTEN status of the PDX tumor was shown. Scale bar: 100 μm. Error bars in (f, l-m, p) indicate standard deviation (S.D.). P values were determined by two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Figure 3. Targeting CHD1 has minimal impact on tumor growth of PTEN-intact prostate cancer (PCa).

(a) Immunoblots of lysates and colony formation assays generated from CHD1 knockdown and control 22Rv1 cells, followed by measurement of subcutaneous tumor growth in vivo (Ctrl group N=8; shCHD1 group N=7). (b) Immunoblots of lysates and colony formation assays generated from CHD1 knockdown and control RWPE-2 cells. (c) Immunoblots of lysates and colony formation assays generated from CHD1 knockdown wild-type or PTEN-knockout DU145 cells. (d) Measurement of subcutaneous tumor weight of CHD1 knockdown DU145 cells (N=5 for PTEN KO shCHD1 group; other group N=6). (e) CHD1 mRNA levels were detected by qRT-PCR in PC-3 cells overexpressing PTEN. Error bars represent ± S.D. of triplicated experiments. (f) Immunoblot time courses of CHD1 protein in control PC-3 (GFP) and PTEN-overexpressing (HA-PTEN) cells treated with 50μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX). (C-Myc as positive control; LDH-A as negative control). (g) Immunoblot time courses of CHD1 protein in LNCaP and 22Rv1 cells treated with cycloheximide (CHX). (h) Immunoblot of CHD1 protein in PTEN-intact and -deficient cell lines. Error bars in (a, d) indicate standard deviation (S.D.). P values were determined by two-tailed t-test. N.S.: not significant.

Extended Data Figure 4. PTEN-AKT-GSK3β pathway promotes CHD1 degradation through β-TrCP mediated ubiquitination-proteasome.

(a) HA-tagged ubiquitin (HA-Ub) was transfected into 293T cells for 40h, followed by 8h MG132 treatment and immunoprecipitation (IP) of endogenous CHD1. CHD1 and HA were detected by immunoblot. (b) Conservation of two β-TrCP binding motifs in vertebrates. (c-d) Immunoblots of CHD1 in BPH1 cells overexpressing Flag-tagged β-TrCP or knockdown of β-TrCP (Yap as positive control). (e) HA-Ub and si β-TrCP were transfected into 293T cells for 48 h, followed by 8 h MG132 treatment (10μM) and detection of CHD1-ubiquitination by IP-immunoblot. (f) V5-tagged WT or two β-TrCP binding motif mutants (DSGXXS => DAGXXA) of CHD1 were introduced into BPH1 cells, followed by CHX treatment over a time course, and V5-tagged CHD1 was detected by immunoblot. (g-h) V5-tagged WT, the two β-TrCP binding motif mutants of CHD1 were introducted into BPH1 cells, followed by V5-IP and detection of ubiquitination and β-TrCP binding by immunoblot. (i) Schematic diagram of GSK3β substrates consensus sequences in β-TrCP binding motifs of CHD1. (j) Endogenous CHD1 was immunoprecipitated, followed by immunoblot using GSK3β antibody. (k) Overexpressing PTEN LNCaP cells were treated with 2μM CHIR for 24h, and CHD1 protein levels were detected by immunoblot. β-actin was used as loading control.

Extended Data Figure 5. CHD1 collaborates with H3K4me3 to activate gene transcription.

(a) Endogenous H3K4me3 was immunoprecipitated from BPH1 cells, and CHD1 binding was detected by immunoblot. (b-c) Immunoblots of H3K4me3 in CHD1 knockdown PC-3 cells or CHD1 knockout LNCaP cells. (d) Heat maps showing the CHD1 and H3K4me3 binding features across gene promoters in shCHD1 vs. Ctrl PC-3 cells (only CHD1/H3K4me3 overlap genes shown). Each panel represents 5 kb upstream and downstream of TSS. (e) Top 10 Hallmark pathways showing enrichment of CHD1 target genes identified by ChIP-seq. 50 MSigDB Hallmark pathways emerged following IPA “Core Analysis.” Graph displays category scores as –log10(p-value) from Fisher’s exact test. (f) Microarray analysis was performed in CHD1 knockdown and control PC-3 cells. Top 10 hallmark pathways showing enrichment of the down-regulated genes in shCHD1 PC-3 cells (Fold changes>1.5). (g-h) GSEA correlation of NF-κB signature with alternatively expressed genes in CHD1 knockout LNCaP cells (g), and wild-type and PTEN knockout mouse prostate tissues (h). Normalized Enrichment Score (NES), Nominal p-value and FDR q-value of correlation are shown. (i) A heat map representation of top 25 down-regulated NF-κB pathway genes in CHD1 knockdown PC-3 cells (from blue, low expression, to red, high expression). (j) Validation of CHD1 regulating genes in two individual CHD1 knockout LNCaP cells using qRT-PCR. Error bars represent ± S.D. of triplicated experiments.

Extended Data Figure 6. CHD1 activates gene transcription in NF-κB pathway.

(a) Heat maps showing expression of down-regulated TNFα/NF-κB pathway genes in 498 TCGA prostate samples, with all samples sorted by CHD1 expression level shown as top bar. Gene names, Pearson correlation coefficient between CHD1 and indicated genes, and two-tailed p value were shown. (b) Immunoblot of total and activated NF-κB p65 in control and CHD1 knockdown PC-3 cells. (c) CHD1/H3K4me3-enriched profiles at indicated genes in CHD1 knockdown and control PC-3 cells. (d) Colony formation assays of rescue CHD1 knockdown PC-3 cells by indicated CHD1 downstream genes of NF-κB pathway. PGE2: Prostaglandin E2, the metabolic product of PTGS2/Cox-2.

Extended Data Figure 7. CHD1 shows synthetic essentiality in PTEN-deficient breast cancer.

(a, b) Schematic representation of the role of CHD1 in PCa. (a) In PTEN-intact prostate cells, GSK3β is activated by PTEN through inhibition of AKT, and phosphorylates CHD1, which stimulates its degradation through β-TrCP mediated ubiquitination-proteasome pathway. (b) However, in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer cells, accumulated CHD1 interacts with and maintains H3K4me3, followed by transcriptional activation of NF-κB downstream genes leading to prostate cancer progression. (c) Mutual exclusiveness of PTEN and CHD1 deletions also occurs in breast cancer and colon cancer. (d-e) Immunoblots of lysates and colony formation assays generated from CHD1 knockdown and control BT549 and MDA-MB-468 cells. (f) Measurement of subcutaneous tumor growth of CHD1 knockdown MDA-MB-468 cells (Ctrl group N=10; shCHD1 group N=8). Error bars in indicate standard deviation (S.D.). P values were determined by two-tailed t-test. (g-h) Immunoblots of lysates and colony formation assays generated from CHD1 knockdown and control MDA-MB-231 and T47D cells.

Extended Data Table 1. Top 30 down-regulated genes in CHD1 knockdown PC-3 cells.

Top 30 down-regulated genes in shCHD1 vs. control PC-3 cells are shown, and 10 genes highlighted in bold are known downstream genes of NF-κB pathway.

| Gene Name | Fold Change (Ctrl/shCHD1) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5, CXCL5 | 268.6616213 |

| 2 | S100 calcium binding protein A8, S100A8 | 177.2496755 |

| 3 | lipocalin 2, LCN2 | 62.23575313 |

| 4 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 3, CXCL3 | 61.23078885 |

| 5 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (prostaglandin G/H synthase and cyclooxygenase), PTGS2 | 56.11995411 |

| 6 | S100 calcium binding protein A9, S100A9 | 44.14645634 |

| 7 | interleukin 8, IL8 | 35.64989451 |

| 8 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2, CXCL2 | 31.37390813 |

| 9 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (melanoma growth stimulating activity, alpha), CXCL1 | 27.15252757 |

| 10 | chromosome 8 open reading frame 4, C8orf4 | 27.09241053 |

| 11 | brain expressed, X-linked 1, BEX1 | 25.25263821 |

| 12 | serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 3, SERPINB3 | 24.09258976 |

| 13 | interleukin 6 (interferon, beta 2), IL6 | 20.87206377 |

| 14 | complement component 3, C3 | 20.49050477 |

| 15 | transforming growth factor, beta-induced, 68kDa, TGFBI | 19.19589456 |

| 16 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20, CCL20 | 18.37413513 |

| 17 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 6 (granulocyte chemotactic protein 2), CXCL6 | 18.16844795 |

| 18 | cytochrome b5 reductase 2, CYB5R2 | 17.12023197 |

| 19 | chromosome 15 open reading frame 48, C15orf48 | 16.9709983 |

| 20 | aquaporin 3 (Gill blood group), AQP3 | 16.50004445 |

| 21 | interleukin 1, beta, IL1B | 15.92818569 |

| 22 | hypothetical protein LOC285628, LOC285628 | 12.89755561 |

| 23 | prostaglandin E synthase, PTGES | 12.81294498 |

| 24 | pro-platelet basic protein (chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 7), PPBP, CXCL7 | 11.50025421 |

| 25 | cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily B, polypeptide 1, CYP1B1 | 11.36293073 |

| 26 | NADPH oxidase, EF-hand calcium binding domain 5, NOX5 | 10.35608831 |

| 27 | fasciculation and elongation protein zeta 1 (zygin I), FEZ1 | 10.32840696 |

| 28 | galanin prepropeptide, GAL | 10.22785538 |

| 29 | bone morphogenetic protein 2, BMP2 | 10.18134837 |

| 30 | interleukin 1 family, member 7 (zeta), IL1F7 | 10.18103235 |

Extended Data Table 2. CHD1 target genes of NF-κB pathway in PC-3 cells.

A summary of 90 down-regulated NF-κB pathway genes in CHD1 knockdown PC-3, including expression fold changes and the peak scores of binding sites with CHD1 or enrichment of H3K4me3 mark.

| Gene Symbol | Entrez Gene Name | Peak Score (ChIP-seq) | Exp Fold Change (Ctrl/shCHD1) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD1 | H3K4me3 | |||

| CXCL3 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 3 | 20.8477 | 28.1396 | 61.231 |

| CXCL2 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2 | 18.31 | 24.2217 | 31.374 |

| CXCL1 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 | 20.9437 | 25.1565 | 27.153 |

| IL6 | interleukin 6 | 12.8091 | 10.9158 | 20.872 |

| CXCL6 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 6 | 12.5971 | 22.7408 | 18.168 |

| IL1B | interleukin 1 beta | 17.5558 | 11.7779 | 15.928 |

| INHBA | inhibin beta A | 19.6438 | 17.8982 | 7.954 |

| ZC3H12A | zinc finger CCCFI-type containing 12A | 15.2155 | 34.8075 | 7.19 |

| PLAU | plasminogen activator, urokinase | 41.0902 | 59.2763 | 4.763 |

| NFKBIA | NFKB inhibitor alpha | 26.6431 | 40.0661 | 4.473 |

| CD44 | CD44 molecule (Indian blood group) | 11.8957 | 24.3992 | 4.211 |

| FOSL2 | FOS like antigen 2 | 16.331 | 26.8986 | 3.349 |

| TNIP1 | TNFAIP3 interacting protein 1 | 15.5569 | 21.336 | 3.233 |

| IER3 | immediate early response 3 | 28.1256 | 26.4733 | 3.054 |

| ACKR3 | atypical chemokine receptor 3 | 7.70203 | 8.73691 | 3.025 |

| DUSP1 | dual specificity phosphatase 1 | 18.9257 | 25.6815 | 2.698 |

| NAM PT | nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase | 12.8093 | 24.4044 | 2.627 |

| CFLAR | CASP8 and FADD like apoptosis regulator | 14.2285 | 21.6311 | 2.544 |

| LAMB3 | laminin subunit beta 3 | 13.0399 | 18.6755 | 2.525 |

| CEBPD | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein delta | 6.54248 | 22.0576 | 2.447 |

| JUNB | jun B proto-oncogene | 20.7099 | 32.9637 | 2.379 |

| VEGFA | vascular endothelial growth factor A | 16.1158 | 28.7962 | 2.243 |

| BTG3 | BTG family member 3 | 9.71861 | 26.8775 | 2.161 |

| PPP1R15A | protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 15A | 10.0349 | 26.0106 | 2.136 |

| GEM | GTP binding protein overexpressed in skeletal muscle | 10.957 | 28.2779 | 2.1 |

| IRF1 | interferon regulatory factor 1 | 12.3429 | 21.9984 | 2.096 |

| PTX3 | pentraxin 3 | 17.3919 | 29.0129 | 2.052 |

| FJX1 | four jointed box 1 | 19.6547 | 32.1701 | 1.847 |

| PHLDA1 | pleckstrin homology like domain family A member 1 | 28.5275 | 51.8317 | 1.826 |

| DUSP4 | dual specificity phosphatase 4 | 26.8631 | 29.1908 | 1.737 |

| FOSL1 | FOS like antigen 1 | 39.8505 | 36.7278 | 1.607 |

| CYR61 | cysteine rich angiogenic inducer 61 | 20.7935 | 29.9102 | 1.598 |

| JUN | jun proto-oncogene | 19.585 | 39.506 | 1.592 |

| SDC4 | syndecan 4 | 12.2208 | 28.5915 | 1.553 |

| IER5 | immediate early response 5 | 13.3464 | 22.5679 | 1.544 |

| IER2 | immediate early response 2 | 31.4396 | 49.4192 | 1.525 |

| ETS2 | ETS proto-oncoqene 2, transcription factor | 13.4695 | 30.3076 | 1.505 |

|

| ||||

| CEBPB | CCAAT/enhancer bindinq protein beta | 17.7794 | 0 | 1.73 |

|

| ||||

| PTGS2 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | 0 | 10.3651 | 56.12 |

| BMP2 | bone morphogenetic protein 2 | 0 | 20.9614 | 10.181 |

| CSF2 | colony stimulating factor 2 | 0 | 12.0562 | 6.422 |

| LIF | leukemia inhibitory factor | 0 | 13.7197 | 5.375 |

| KYNU | kynureninase | 0 | 10.8662 | 5.097 |

| TNFAIP2 | TNF alpha induced protein 2 | 0 | 19.0498 | 3.92 |

| SOD2 | superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial | 0 | 20.1497 | 3.542 |

| ICAM1 | intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | 0 | 17.779 | 3.173 |

| CDKN1A | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A | 0 | 27.1233 | 2.94 |

| PLAUR | plasminogen activator, urokinase receptor | 0 | 20.5747 | 2.872 |

| TNC | tenascin C | 0 | 12.682 | 2.821 |

| NFKBIE | NFKB inhibitor epsilon | 0 | 22.8154 | 2.801 |

| HBEGF | heparin binding EGF like growth factor | 0 | 27.7034 | 2.741 |

| AREG | amphiregulin | 0 | 11.5075 | 2.663 |

| NFKB2 | nuclear factor kappa B subunit 2 | 0 | 18.1199 | 2.593 |

| RELB | RELB proto-oncogene, NF-kB subunit | 0 | 14.7293 | 2.57 |

| SOCS3 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | 0 | 44.0616 | 2.476 |

| BCL3 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 3 | 0 | 14.1549 | 2.388 |

| RNF19B | ring finger protein 19B | 0 | 28.4536 | 2.361 |

| SQSTM1 | sequestosome 1 | 0 | 24.3794 | 2.328 |

| IL15RA | interleukin 15 receptor subunit alpha | 0 | 26.6349 | 2.324 |

| TNFAIP3 | TNF alpha induced protein 3 | 0 | 9.96643 | 2.212 |

| EIF1 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1 | 0 | 19.1981 | 2.199 |

| KLF2 | Kruppel-like factor 2 | 0 | 23.576 | 2.173 |

| MAFF | v-maf avian musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog F | 0 | 26.0075 | 2.101 |

| ATF3 | activating transcription factor 3 | 0 | 37.8612 | 2.081 |

| RHOB | ras homolog family member B | 0 | 32.8819 | 2.032 |

| TRIP10 | thyroid hormone receptor interactor 10 | 0 | 37.5187 | 1.95 |

| GADD45B | growth arrest and DNA damage inducible beta | 0 | 29.8176 | 1.945 |

| SAT1 | spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1 | 0 | 14.176 | 1.908 |

| TAP1 | transporter 1, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP) | 0 | 28.2344 | 1.906 |

| PER1 | period circadian clock 1 | 0 | 17.6631 | 1.813 |

| SERPINB8 | serpin family B member 8 | 0 | 22.5062 | 1.786 |

| TNFSF9 | tumor necrosis factor superfamily member 9 | 0 | 23.0011 | 1.762 |

| SPSB1 | splA/ryanodine receptor domain and SOCS box containing 1 | 0 | 29.9498 | 1.735 |

| TUBB2A | tubulin beta 2A class I la | 0 | 26.5246 | 1.719 |

| SNN | stannin | 0 | 19.8059 | 1.63 |

| NR4A1 | nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1 | 0 | 22.6394 | 1.626 |

| MARCKS | myristoylated alanine rich protein kinase C substrate | 0 | 15.7629 | 1.613 |

| EHD1 | EH domain containing 1 | 0 | 39.3525 | 1.584 |

| TNIP2 | TNFAIP3 interacting protein 2 | 0 | 21.4255 | 1.579 |

| CD83 | CD83 molecule | 0 | 26.8444 | 1.569 |

| BTG2 | BTG family member 2 | 0 | 36.7798 | 1.542 |

|

| ||||

| CCL20 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 20 | 0 | 0 | 18.374 |

| SERPINE1 | serpin family E member 1 | 0 | 0 | 9.249 |

| SERPINB2 | serpin family B member 2 | 0 | 0 | 7.824 |

| BCL2A1 | BCL2 related protein A1 | 0 | 0 | 7.616 |

| TNFAIP6 | TNF alpha induced protein 6 | 0 | 0 | 7.377 |

| IL1A | interleukin 1 alpha | 0 | 0 | 6.351 |

| IL23A | interleukin 23 subunit alpha | 0 | 0 | 5.887 |

| PLPP3 | phospholipid phosphatase 3 | 0 | 0 | 1.607 |

| B4GALT1 | beta-1,4-qalactosyltransferase 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.503 |

Extended Data Table 3. Mutual exclusiveness pairs in PCa.

Gene A (PTEN, TP53, SMAD4 and RB1) represents the most common altered tumor suppressors in PCa. For each gene in the Gene B list the table shows (1) mutual exclusiveness score (odds ratio score) with Gene A; (2) Gene B expression in Gene A deleted PCa samples (P<0.1); and (3) proposed functions in cancer progression. P values were determined by two-tailed t-test.

| Gene A | Gene B | #Deletion (#Total samples=332)

|

Mutual Exclusivenes s score* | Gene B Expression

|

Gene B Description | Function in cancer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only in A | Only in B | In A and B | Mean In A Del samples | Mean in all samples | P-VALUE | |||||

| PTEN (Deletion) | PARP1 | 64 | 7 | 1 | −0.784987109 | 4104.537 726 |

3716.751 276 |

0.000887378 | Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 | PARP1 has a role in repair of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) breaks. PARP1 is overexpressed in a number of cancer types. PARP1 inhibitors prove highly effective therapies for cancers with BRCAness. |

| PLK4 | 64 | 10 | 1 | −1.316303546 | 65.86536 923 |

50.79139 009 |

0.019904268 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase PLK4 | PLK4 knockdown decreases in vivo growth of breast cancer xenografts. PLK4 inhibitor, CFI-400945, had single-agent antitumor activity in vivo, and induced significant regression of PTEN-null TNBC and colon cancer, suggesting PLK4 may be a PTEN-null therapeutic target. | |

| HDAC2 | 62 | 36 | 3 | −1.68740977 | 2283.613 283 |

1992.844 976 |

4.62E-05 | Histone deacetylase 2 | HDAC2 is often significantly overexpressed in solid tumors; its inactivation resulted in regression of tumor cell growth and activation of cellular apoptosis. | |

| DHFR | 64 | 10 | 1 | −1.316303546 | 303.3643 354 |

239.0140 045 |

0.00019444 | Dihydrofolate reductase | DHFR is essential for DNA precursor synthesis, thus it was the first enzyme to be targeted for cancer chemotherapy. | |

| MY06 | 64 | 22 | 1 | −2.52279368 | 7100.480 743 |

5470.694 425 |

0.006672326 | Unconventional myosin-VI | MY06 overexpressed in prostate cancer and multiple cancer types; MY06 knockdown attenuates prostate cancer cell migration; shMY06 reduced cell growth and increased apoptosis in colorectal cancer. | |

| NQ01 | 64 | 14 | 1 | −1.824361347 | 1016.423 495 |

752.4725 285 |

0.012669247 | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase [quinone] 1 | NQ01 is expressed at high levels in numerous human cancers, including breast, colon, cervix, lung, and pancreas; NQ01 has potential as a therapeutic target for cancer therapy. | |

|

| ||||||||||

| TP53 (Mutation) | CDK7 | 29 | 19 | 0 | −11.94014085 | 517.6720 103 |

453.7370 643 |

0.009587173 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 7 | Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells are highly dependent on CDK7, and CDK7 inhibitor blocks tumor growth in TNBC PDX model; A covalent CDK7 inhibitor, THZ1, strongly reduces the proliferation and cell viability of T-ALL cell lines. |

| RAD17 | 29 | 19 | 0 | −11.94014085 | 626.6575 414 |

594.3827 793 |

0.084934618 | Cell cycle checkpoint protein RAD17 | Overexprssed in colon and breast cancer; Depletion of RAD17 sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine. | |

| BDP1 | 29 | 18 | 0 | −11.83157895 | 1013.501 324 |

829.4167 408 |

0.025936849 | Transcription factor TFIIIB component B″ homolog | High rates of Pol III transcription are necessary for cancer cells to sustain growth, and requires TFIIIB. BDP1 is a component of TFIIIB. | |

| GALNT 3 | 29 | 13 | 0 | −11.3 | 2594.882 314 |

2168.293 56 |

0.054622435 | Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 3 | GALNT3 overexpression in multiple cancers, including gastric, ovarian, pancreatic and lung. GALNT3 knockdown in epithelial ovarian cancer cells led to sharp decrease of cell proliferation, migration and invasion. | |

|

| ||||||||||

| SMAD4 (Deletion) | NMT1 | 6 | 17 | 0 | −10.33009709 | 2115.429 033 |

1917.665 085 |

0.026318219 | Glycylpeptide N- tetradecanoyltransferase 1 | NMT1 activity and protein expression were higher in human colorectal cancer, gallbladder carcinoma and brain tumors. NMT1 inhibition reduces cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in melanoma cell lines and also blocks tumor growth in vivo. |

| ACLY | 6 | 11 | 0 | −10.20952381 | 9849.062 85 |

8788.038 608 |

0.064880591 | ATP-citrate synthase | ACLY is upregulated or activated in several types of cancers, and its inhibition is known to induce proliferation arrest in cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. | |

| XBP1 | 6 | 9 | 0 | −10.170347 | 23601.68 268 |

16697.94 201 |

0.002389882 | X-box-binding protein 1 | XBP1 is activated in TNBC and has a pivotal role in the tumorigenicity and progression of this human breast cancer subtype; Depletion of XBP1 inhibited tumor growth and tumor relapse. | |

|

| ||||||||||

| RB1 (Deletion) | MBD2 | 53 | 5 | 0 | −10.96715328 | 1272.695 374 |

1156.523 888 |

0.034600109 | Methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 2 | MBD2 is a very attractive target for cancer prevention and treatment; Mbd2 deficiency dramatically reduces adenoma burden and extends life span in a gene dosage- dependent manner in mouse model. |

| PATZ1 | 53 | 5 | 0 | −10.96715328 | 1912.832 768 |

1675.643 638 |

0.005508321 | ΡΟΖ-, AT hook-, and zinc finger- containing protein 1 | PATZ1 binds to other DNA binding structures to play an important role in chromatin modeling and transcription regulation; PATZ1 is overexpressed in colon carcinomas; Its silencing inhibits colon cancer cell proliferation or increases sensitivity to apoptotic stimuli of glioma cells; The development of B-cell lymphomas, sarcomas, hepatocellular carcinomas and lung adenomas in Patzl-knockout mice supports its tumor suppressor function. | |

| SKA1 | 53 | 4 | 0 | −10.77090909 | 34.81816 038 |

29.72090 931 |

0.099886183 | Spindle and kinetochore- associated protein 1 | SKA1 is overexpressed in gastric cancer and promotes cell growth; SKA1 overexpression promotes prostate tumourigenesis; SKA1 is required for metastasis and cisplatin resistance of non-small cell lung cancer. | |

Supplementary Material

The CHD1/H3K4me3-enriched TSS regions across gene promoters in PC-3 cells (only CHD1 and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq overlap genes shown)

The annotated CHD1 binding regions across gene promoters in PC-3 cells.

Fold changes of down-regulated and up-regulated genes in shCHD1 (#2 and #4) vs. control PC-3 cells are shown (Fold change >1.5). P values are calculated by t test.

Fold changes of down-regulated and up-regulated genes in CHD1 knockout vs. control LNCaP cells are shown (Fold change >1.5). P values are calculated by t test.

Supplementary Table 5. Real-time PCR primers.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Simon W. Hayward (Vanderbilt University) for providing the BPH1 cell line, Dr. Peter Shepherd for providing the PDX models, Dr. Yaohui Chen for providing Flag-tagged β-TrCP plasmid, Dr. Tony Gutschner for generating and providing X330-Cherry vector for CRISPR, and Dr. Yonathan Lissanu Deribe for providing HA-tagged PTEN plasmid. This work was supported in part by the Odyssey Program and Theodore N. Law Endowment For Scientific Achievement at The University of Texas MDACC 600649-80-116647-21 (D.Z.); DOD Prostate Cancer Research Program (PCRP) Idea Development Award–New Investigator Option W81XWH-14-1-0576 (X.Lu); NIH Pathway to Independence (PI) Award (K99/R00)-NCI: 1K99CA194289 (G.W.); DOD PCRP W81XWH-14-1-0429 (P.D.); CPRIT research training award RP140106-DC (D.C.); NIH grants P01 CA117969 (R.A.D) and R01 CA084628 (R.A.D).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: D.Z. Y.A.W. and R.A.D. conceived the original hypothesis of synthetic essentiality. D.Z. designed and performed cell line derived xenograft model and signaling pathway experiments. X.Lu and X.S. performed the patient derived xenograft model and siRNA treatment. G.W. performed microarray and GSEA analyses. Z.L. performed ChIP-seq experiments, and M.T. performed ChIP-seq data analysis. W.L. reviewed and scored human tissue sections. P.T. and W.L. provided the human prostate cancer tissue sections. J.L., J.Z. and J.R.C. performed TCGA data analyses. X.Liang, S.S., J.R.C., P.Deng and P.C. assisted with cell culture, IHC, western blotting, and xenograft-associated experiments. N.M.N. provided the PDX model. Y.A.W., X.Lu, G.W., Z.L., D.C. and P.Dey provided critical intellectual contributions throughout the project. D.Z., Y.A.W., D.J.S. and R.A.D. wrote the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data Availability Statement:

The Microarray dataset generated during the current study has been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository with the accession code GSE84970 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE84970). The ChIP-seq dataset generated in this study has been deposited in GEO repository with the accession code GSE91401 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE91401). The ChIP-seq signal annotate file and alternatively expressed genes lists (fold change >1.5) generated in this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). Relevant TCGA datasets were downloaded from http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/runs/stddata__2016_01_28/data/PRAD/20160128/ or http://www.cbioportal.org.

References

- 1.Hartwell LH, Szankasi P, Roberts CJ, Murray AW, Friend SH. Integrating genetic approaches into the discovery of anticancer drugs. Science. 1997;278:1064–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farmer H, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller FL, et al. Passenger deletions generate therapeutic vulnerabilities in cancer. Nature. 2012;488:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature11331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cairns P, et al. Frequent inactivation of PTEN/MMAC1 in primary prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4997–5000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, et al. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer cell. 2003;4:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. doi:S1535610803002150 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fece de la Cruz F, Gapp BV, Nijman SM. Synthetic lethal vulnerabilities of cancer. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2015;55:513–531. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant HE, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–917. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nijhawan D, et al. Cancer vulnerabilities unveiled by genomic loss. Cell. 2012;150:842–854. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas RK, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nature genetics. 2007;39:347–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciriello G, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Mutual exclusivity analysis identifies oncogenic network modules. Genome research. 2012;22:398–406. doi: 10.1101/gr.125567.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendes-Pereira AM, et al. Synthetic lethal targeting of PTEN mutant cells with PARP inhibitors. EMBO molecular medicine. 2009;1:315–322. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dillon LM, Miller TW. Therapeutic targeting of cancers with loss of PTEN function. Current drug targets. 2014;15:65–79. doi: 10.2174/1389450114666140106100909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason JM, et al. Functional characterization of CFI-400945, a Polo-like kinase 4 inhibitor, as a potential anticancer agent. Cancer cell. 2014;26:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang S, et al. Recurrent deletion of CHD1 in prostate cancer with relevance to cell invasiveness. Oncogene. 2012;31:4164–4170. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.590. onc2011590 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burkhardt L, et al. CHD1 is a 5q21 tumor suppressor required for ERG rearrangement in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2795–2805. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1342. 0008-5472.CAN-12-1342 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Genome Atlas, Research N. The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell. 2015;163:1011–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodrigues LU, et al. Coordinate loss of MAP3K7 and CHD1 promotes aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1021–1034. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1596. 75/6/1021 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart M, et al. The F-box protein beta-TrCP associates with phosphorylated beta-catenin and regulates its activity in the cell. Current biology: CB. 1999;9:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao B, Li L, Tumaneng K, Wang CY, Guan KL. A coordinated phosphorylation by Lats and CK1 regulates YAP stability through SCF beta-TRCP. Gene Dev. 2010;24:72–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.1843810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strack P, et al. SCF beta-TRCP and phosphorylation dependent ubiquitination of I kappa B alpha catalyzed by Ubc3 and Ubc4. Oncogene. 2000;19:3529–3536. doi: 10.1038/Sj.Onc.1203647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs SY, Spiegelman VS, Kumar KG. The many faces of beta-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligases: reflections in the magic mirror of cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:2028–2036. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flanagan JF, et al. Double chromodomains cooperate to recognize the methylated histone H3 tail. Nature. 2005;438:1181–1185. doi: 10.1038/nature04290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaspar-Maia A, et al. Chd1 regulates open chromatin and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2009;460:863–868. doi: 10.1038/nature08212. nature08212 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-Neriah Y, Karin M. Inflammation meets cancer, with NF-kappaB as the matchmaker. Nature immunology. 2011;12:715–723. doi: 10.1038/ni.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang SY, Pettaway CA, Uehara H, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Blockade of NF-kappa B activity in human prostate cancer cells is associated with suppression of angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. Oncogene. 2001;20:4188–4197. doi: 10.1038/Sj.Onc.1204535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin R, et al. Inhibition of NF-kappa B signaling restores responsiveness of castrate-resistant prostate cancer cells to anti-androgen treatment by decreasing androgen receptor-variant expression. Oncogene. 2015;34:3700–3710. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding Z, et al. SMAD4-dependent barrier constrains prostate cancer growth and metastatic progression. Nature. 2011;470:269–273. doi: 10.1038/nature09677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wan X, et al. Prostate cancer cell-stromal cell crosstalk via FGFR1 mediates antitumor activity of dovitinib in bone metastases. Science translational medicine. 2014;6:252ra122. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garber M, et al. A high-throughput chromatin immunoprecipitation approach reveals principles of dynamic gene regulation in mammals. Molecular cell. 2012;47:810–822. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liberzon A, et al. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell systems. 2015;1:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The CHD1/H3K4me3-enriched TSS regions across gene promoters in PC-3 cells (only CHD1 and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq overlap genes shown)

The annotated CHD1 binding regions across gene promoters in PC-3 cells.

Fold changes of down-regulated and up-regulated genes in shCHD1 (#2 and #4) vs. control PC-3 cells are shown (Fold change >1.5). P values are calculated by t test.

Fold changes of down-regulated and up-regulated genes in CHD1 knockout vs. control LNCaP cells are shown (Fold change >1.5). P values are calculated by t test.

Supplementary Table 5. Real-time PCR primers.