Abstract

Background

During its 120 days sojourn in the circulation, the red blood cell (RBC) remodels its membrane. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked enzyme that may serve as a marker for membrane processes occurring this ageing-associated remodelling process.

Materials and methods

Expression and enzymatic activity of AChE were determined on RBCs of various ages, as obtained by separation based on volume and density (ageing in vivo), and on RBCs of various times of storage in blood bank conditions (ageing in vitro), as well as on RBC-derived vesicles.

Results

During ageing in vivo, the enzymatic activity of AChE decreases, but not the AChE protein concentration. In contrast, neither AChE activity nor concentration show a consistent, significant decrease during ageing in vitro. CD59, another GPI-linked protein that protects against complement-induced removal, also remains constant during storage. The cellular content of the integral membrane protein glycophorin A, however, decreases with storage time in the more dense RBC fractions. The latter are enriched in echinocytes and other misshapen cells during storage.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that, during RBC ageing, GPI-linked proteins and integral membrane proteins are differentially sorted. Also, the vesicles that are generated in vitro show a fast and extensive loss of AChE activity, but not of AChE expression. Thus, AChE characteristics may constitute sensitive biomarkers of RBC ageing in vivo, and a source of information on the structural and functional changes that GPI-linked proteins undergo during ageing in vivo and in vitro. This information may help to understand RBC homeostasis and the effects of transfusion, especially in immunologically compromised patients.

Keywords: acetylcholinesterase, ageing, red blood cell, storage, vesicles

Introduction

During its life of 120 days in the circulation, functionality of the red blood cell (RBC) is maintained and cell removal is postponed by disposal of modified haemoglobin and damaged membrane components through vesiculation. When vesiculation capacity has reached its limits, the ongoing mechanical, osmotic and oxidative stress induces recognition and removal of the old RBC by the immune system1–3. The same mechanisms that cause the decrease in deformability, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production and maintenance of redox status, are also likely to be responsible for the generation of removal signals. This process revolves around band 3 and its partners1,2.

Although considerable progress has been made in the characterisation of RBCs of various ages by comparative proteomics and metabolomics, the molecular details of the ageing mechanism(s) remain elusive2,4–6. This is mainly due to the practical and ethical limitations of manipulating RBCs in healthy volunteers. Insights obtained from investigating patients with RBC-centred pathologies are obscured by disease-specific and systemic effects7,8. Thus, storage in blood bank conditions may be the most valid model for the elucidation of RBC ageing processes, with the highest translational value9–11.

In all conditions, the study of RBC ageing is hampered by the absence of an easily determined, unambiguous, general age marker. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), linked to the RBC membrane through a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor, might be such a marker for RBC ageing in vivo12. Determination of AChE characteristics may also yield information on the mechanism of ageing-associated vesicle formation. Microvesicles generated after an increase in intracellular calcium concentration or after mechanically-induced membrane deformation in vitro have been described to be enriched in AChE as well as other GPI-anchored proteins such as CD55 and CD59, with a concomitant depletion of these proteins in the cellular membrane13–15. In addition, we have found that the membrane distribution of AChE in vesicles generated during storage in blood bank conditions changes with storage time16. Therefore, we investigated the structural and functional changes that AChE undergoes during RBC ageing in vivo, and compared this with ageing in vitro during storage in blood bank conditions.

Materials and methods

Red blood cell sampling

Fresh RBCs were isolated from 5 mL whole EDTA-blood from healthy volunteers. Written informed consent was obtained from all donors. The study was performed following the guidelines of the local medical ethical committee and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Storage experiments were performed with RBCs from 5 leucodepleted red cell concentrates (3 blood group A RhD-positive donors, 1 blood group A RhD-negative donor, 1 blood group O RhD-positive donor), as described before17. Samples of 10 mL were taken at 1, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 35 days after blood collection. RBCs were isolated from fresh blood and leukocytes and platelets were removed as described before17. RBCs were extensively washed three times with Ringer (125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 32 mM Hepes, 5 mM glucose, 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) by repeated centrifugation for 15 min at 700 g.

Red blood cell fractionation

Red blood cells were fractionated according to cell volume followed by a fractionation according to cell density as described earlier18, and fractions were combined to achieve 5 fractions ranging in cell age from young to middle-aged to old cells, as determined by their HbA1c content3.

Red blood cell fractionation according to density was performed using a discontinuous Percoll gradient consisting of six layers ranging from 0% Percoll (1.060 g/mL) to 80% Percoll (1.096 g/mL) and the resulting layers were combined into top, middle and bottom layer fractions, basically as described before17,18.

Acetylcholinesterase activity assay

Acetylcholinesterase activity of intact RBCs at a concentration of 2×106 cells/mL and RBC-derived vesicles was measured using a modified Ellman’s method under Vmax conditions, basically as described before12,15. The AChE activity of vesicles was measured using the supernatant obtained after centrifugation for 30 min at 2,880 g in the presence of the butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor tetraisopropyl pyrophosporamide (0.1 μM, Sigma Life Sciences, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands). One arbitrary AChE enzyme unit was defined as an increase in absorbance at 412 nm of 0.005 per minute, determined from the slope of the initial part of the absorption vs the time curve that was obtained by linear regression analysis.

Flow cytometry

The presence of AChE on RBCs was examined by flow cytometry using goat anti-AChE ab34533 (biotin, 1:25; Molecular Probes, ABCAM, Uithoorn, The Netherlands), detected by a rabbit anti-goat labeled with Alexa 488 (1:200; Molecular Probes). RBCs were analysed with a flow cytometer (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and its accompanying software (CELLQUEST, Becton Dickinson). The results are expressed as percentages of AChE-positive RBCs and/or their mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Vesicles were isolated and analysed by flow cytometry, as described previously19.

Microscopy

Cells were suspended in Ringer and RBC morphology was assessed by classifying the cells in normocytes, echinocytes, cells of indistinct morphology (misshapen cells), stomatocytes, macrocytes, spherocytes, ovalocytes and elliptocytes in random field pictures, using confocal laser microscopy, as described before20. At least 100 cells were analysed per sample.

Results

In order to investigate the structural and functional changes in acetylcholinesterase upon ageing in vivo and in vitro, we started by determining enzymatic activity. RBCs isolated from whole blood and separated according to cell age by a double separation method showed a decrease in activity with increasing cell age (Table I). Similar differences were observed when cells were separated based on differences in cell density only (Table I). This loss of activity could be due to a selective loss of AChE-containing membrane by vesiculation. Quantitation of AChE content by flow cytometry, however, showed no differences between the various cell fractions (Table I). These data indicate that RBC ageing in vivo is not accompanied by a selective loss of AChE protein, but by a decrease in enzyme activity.

Table I.

Red blood cell (RBC) acetylcholinesterase (AchE) activity during ageing in vivo.

| Double separation | Density separation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Fraction | AChE activity ±SD | N | MFI anti-AChE | N | Layer | AChE activity ±SD | N | MFI anti-AChE ±SD | N |

| Young | 100 | 4 | 100 | 1 | Top | 100 | 4 | 100 | 3 |

| Middle-aged | 83.70±30.71 | 4 | 102.69 | 1 | Middle | 79.70±16.01 | 4 | 97.96±11.11 | 3 |

| Old | 68.73*±18.34 | 4 | 99.78 | 1 | Bottom | 61.23*± 8.53 | 4 | 111.6±4.2 | 3 |

Acetylcholinesterase activity was measured for RBCs separated according to cell age using double separation, and on RBCs separated according to density using Percoll gradients (see “Materials and methods”). Enzyme activity, expressed as arbitrary units, and protein content, expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), were determined using a spectrophotometric assay and flow cytometry, respectively (see “Materials and methods”).

p<0.05, as determined by ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparison test, as compared with the young fraction or top layer2,3.

SD: standard deviation; N: number; RBC: red blood cell.

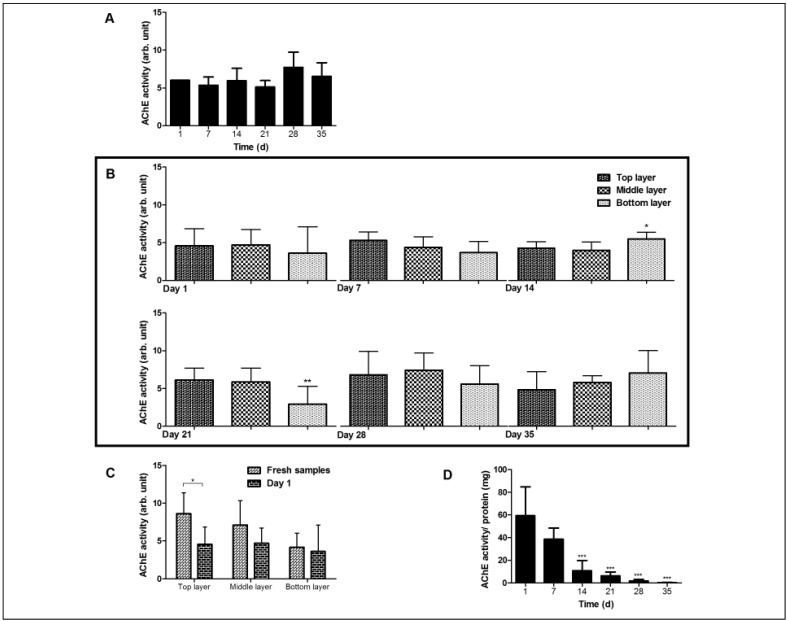

In contrast, during ageing in vitro, i.e. during storage as red cell concentrates in the blood bank, the mean AChE activity of RBCs did not undergo a statistically significant change with storage time (Figure 1A). However, there was considerable variation between the red cell concentrates (data not shown), probably due to biological, inter-individual variability in the response to the artificial storage conditions17, 21. Measurement of the AChE activities of RBCs in density-separated fractions did not show a consistent correlation between enzyme activity and density, although there was a significant decrease in the most dense cell layer after 21 days of storage, which was not observed at later time points (Figure 1B). These observations are in stark contrast to the differences between the activity of Percoll-separated RBCs of fresh samples, i.e. before they underwent the red cell concentrate production procedure. Already on the first day, the AChE activity of the least dense RBCs was significantly reduced compared with the activity of fresh RBCs (Figure 1C). In contrast to the RBCs, pronounced changes were observed in RBC-derived vesicles. During storage, the vesicle concentration increases from a vesicle/RBC ratio of 1.0 at days 7 and 14 to a vesicle/RBC ratio of 1.5 at day 21, and a vesicle/RBC ratio of 4.3 on day 35, as has been shown before16. The AChE activity of these vesicles, however, showed a strong, steady decrease during storage (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Red blood cell acetylcholinesterase (AchE) activity during storage in blood bank conditions.

(A) Acetylcholinesterase activity of unseparated red blood cells (RBCs) during storage. (B) AChE activity of RBCs during storage after Percoll separation per layer. (C) Comparison of AChE activity of Percoll-separated fresh RBCs and RBCs after one day of blood bank storage. (D) AChE activity of RBC-derived vesicles expressed as arbitrary (arb.) unit/total vesicle protein during storage. RBCs and vesicles were isolated and their AChE activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. (A–D) Tukey’s multiple comparison test, ANOVA. (C) Student’s t-test.

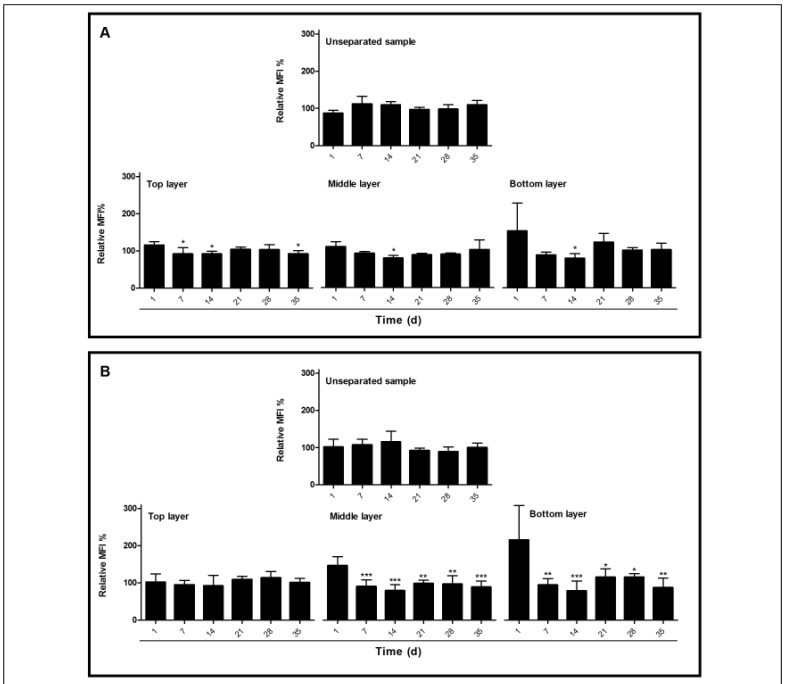

CD59, another GPI-linked protein showed no change in cell content with storage time, neither in the whole population nor in the various cell fractions (Figure 2A). Similar data were obtained with an anti-AChE antibody and comparable data have been obtained for ageing in vivo3. In addition to GPI-anchored proteins, we included the integral membrane protein CD235a (glycophorin A) in our analyses. Even though there were no storage-associated changes in the total cell population, there was a decrease in glycophorin A content in the higher density RBCs of the middle and bottom Percoll layers starting after one week of storage (Figure 2B). These data indicate a selective disappearance of integral membrane proteins upon storage.

Figure 2.

Red blood cell (RBC) CD59 and glycophorin A content during storage in blood bank conditions.

(A) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD59 and (B) CD235a (glycophorin A) of unseparated samples, and the top, middle and bottom layers after density separation during storage time. MFI values are expressed as percentage relative to the MFI of the RBCs on day 1, respectively of the RBCs in the top layers. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Tukey’s multiple comparison test, ANOVA.

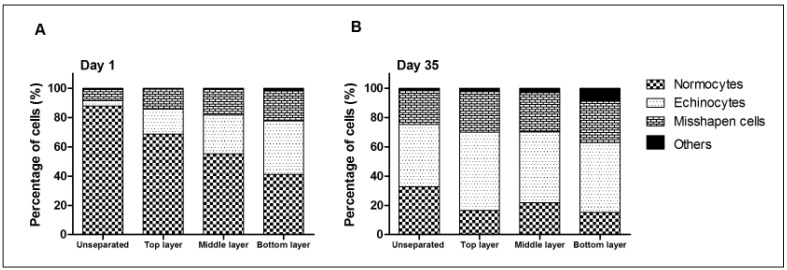

Ageing in vivo as well as ageing in vitro have been described to be accompanied by changes in cell shape9,18. We performed a semi-quantitative analysis of RBC morphology during storage, both in unseparated samples and in the RBC fractions obtained after density separation. Our data confirm previous data, showing an overall decrease in the fraction of normocytes when storage time increases, with a concomitant increase in the numbers of echinocytes and otherwise misshapen cells (Figure 3). Morphological analysis of the various Percoll layers showed considerable variation, even within one red cell concentrate during storage (data not shown), but in general this change occurred in all layers (Figure 3A and B), and the most dense layers are enriched in echinocytes already after one day of storage (Figure 3A). We found no statistically significant correlations between cell morphology, AChE activity or AChE content.

Figure 3.

Red blood cell (RBC) morphology during storage in blood bank conditions.

RBCs were classified as normocytes, echinocytes, unclassified misshapen cells, or “others” (ovalocytes, elliptocytes, stomatocytes).

Discussion

Flow cytometry measurements of protein expression show no alterations in cellular AChE content with ageing in vivo (Table I). Together with previous data on other GPI-linked proteins such as CD55 and CD593, as confirmed here, these findings suggest that there is no specific loss of GPI-linked proteins from the RBCs by vesiculation in physiological circumstances. Thus, previous findings suggesting selective sorting of GPI-linked proteins and microdomain-associated proteins during RBC vesiculation13–16,22 are likely to be related to the method that was employed to generate such vesicles in vitro16. This conclusion is supported by proteomic data that show selective membrane and cytoskeletal protein sorting during vesicle formation, but also indicate that different mechanisms underlie vesicle generation in vivo and in vitro5. In contrast, AChE enzyme activity clearly decreases with ageing in vivo. Such a decrease was already visible after Percoll separation only (Table I). Since this density-based separation generates fractions that are only moderately enriched with young but not with older cells20,23, this finding strongly suggests that the first and major loss of enzyme activity in vivo occurs relatively early in RBC life. Thus, AChE activity, but not AChE amount, constitutes a sensitive biomarker of RBC ageing in vivo. This apparent divergence between changes in expression and activity of one GPI-linked protein indicates that the absence of a clear ageing-associated decrease in CD55 and CD59 content, as has been reported previously3, does not necessarily imply sustained protection against complement activation-associated opsonisation during ageing24. Thus, during ageing in vivo, CD59 may very well undergo conformational changes that decrease its capacity to shield the RBC from the complement system. This implication of our findings warrants further investigation of the role of complement in RBC removal in physiological conditions.

The conspicuous discrepancy between AChE protein content and enzymatic activity becomes even more pronounced in the vesicles that are produced with increasing storage time (Table I and Figure 1D). This apparent enrichment of inactivated AChE in vesicles confirms previous proteomic and immunological data showing a removal of damaged membrane components by vesiculation, both in vivo and in vitro3–5,25–27. Thus, vesicles in red cell concentrates may constitute a rich and relatively pure source of damaged AChE, which may facilitate a molecular identification of the processes that cause the underlying structural alterations during ageing in vivo and in vitro. Such an identification will help in understanding the unwanted side effects of transfusion, especially with regard to complement-mediated haemolysis in susceptible patients.

The data obtained by determination of AChE expression and activity during RBC storage in blood bank conditions emphasise the differences between ageing in vivo and ageing in vitro. In general, neither AChE expression nor enzymatic activity decreased significantly with storage time (Figure 1A). This result is in agreement with previous data showing no significant or only small alterations in AChE activity after prolonged storage times28. Also, there were hardly any consistent differences between the RBCs of the different Percoll layers (Figure 1B). Many other observations show storage-associated changes in morphology (Figure 39), metabolism and membrane protein composition5,12. A large inter-individual variability, together with an altered osmotic behaviour in response to the storage medium16, are likely to obscure any ageing-related changes occurring in blood bank conditions. Data on phosphatidylserine exposure support these hypotheses, as does the absence of a decrease in cell volume during storage, in spite of the large increase in vesicles2,16,25,29. These phenomena also hamper the interpretation of the flow cytometry data on CD59 and glycophorin A content with storage (Figure 2). A comparison of the various density fractions, however, suggests that during storage integral and lipid-linked membrane proteins undergo different fates when the RBCs change from discocytes to echinocytes (Figures 2 and 3). Such fates are likely to be dependent on selective removal by vesiculation.

The relatively large difference in AChE activity between fresh and 1-day old RBCs (Figure 1C) is likely to be caused by loss of AChE in vesicles that are generated during the mechanical stress that the RBCs undergo during the production of the red cell concentrates. The small, but significant increase in phosphatidylserine-exposing RBCs during blood bank processing and/or in the first week of storage supports this theory21.

Conclusions

The physiological role of RBC-bound AChE is not clear, but our findings may provide new tools for studying the putative role of acetylcholine on RBC physiology, and the impact of transfusion on acetylcholinesterase-mediated RBC homeostasis and survival, and on the circulation30–33.

Footnotes

Funding

JKFL was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - Brazil.

Authorship contributions

JKFL and GJCGMB performed the experiments, JKFL, MJWA-H, RB and GJCGMB designed the experiments. All Authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kay M. Immunoregulation of cellular life span. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1057:85–111. doi: 10.1196/annals.1356.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosman GJ, Stappers M, Novotný VM. Changes in band 3 structure as determinants of erythrocyte integrity during storage and survival after transfusion. Blood Transfus. 2010;8:s48–52. doi: 10.2450/2010.008S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willekens FL, Werre JM, Groenen-Döpp YA, et al. Erythrocyte vesiculation: a self-protective mechanism? Br J Haematol. 2008;141:549–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosman GJ, Lasonder E, Groenen-Döpp YA, et al. The proteome of erythrocyte-derived microparticles from plasma: new clues for erythrocyte aging and vesiculation. J Proteomics. 2012;76:203–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosman GJ, Lasonder E, Groenen-Döpp YA, et al. Comparative proteomics of erythrocyte aging in vivo and in vitro. J Proteomics. 2010;73:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Alessandro A, Blasi B, D’Amici GM, et al. Red blood cell subpopulations in freshly drawn blood: application of proteomics and metabolomics to a decades-long biological issue. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:75–87. doi: 10.2450/2012.0164-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darghouth D, Koehl B, Madalinski G, et al. Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease is mirrored by the red blood cell metabolome. Blood. 2011;117:e57–66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-299636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darghouth D, Koehl B, Heilier JF, et al. Alterations of red blood cell metabolome in overhydrated hereditary stomatocytosis. Haematologica. 2011;96:1861–5. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.045179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Alessandro A, D’Amici GM, Vaglio S, Zolla L. Time-course investigation of SAGM-stored leukocyte-filtered red bood cell concentrates: from metabolism to proteomics. Haematologica. 2012;97:107–15. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.051789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosman GJ. Survival of red blood cells after transfusion: processes and consequences. Front Physiol. 2013;4:376. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reisz JA, Wither MJ, Dzieciatkowska M, et al. Oxidative modifications of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase regulate metabolic reprogramming of stored red blood cells. Blood. 2016;128:e32–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-714816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prall YG, Gambhir KK, Ampy FR. Acetylcholinesterase: an enzymatic marker of human red blood cell aging. Life Sci. 1998;63:177–84. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butikofer P, Kuypers FA, Xu CM, et al. Enrichment of two glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins, acetylcholinesterase and decay-accelerating factor, in vesicles released from human red blood cells. Blood. 1989;74:1481–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knowles DW, Tilley L, Mohandas N, Chasis JA. Erythrocyte membrane vesiculation: model for the molecular mechanism of protein sorting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12969–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salzer U, Hinterdorfer P, Hunger U, et al. Ca(++)-dependent vesicle release from erythrocytes involves stomatin-specific lipid rafts, synexin (annexin VII), and sorcin. Blood. 2002;99:2569–77. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salzer U, Zhu R, Luten M, et al. Vesicles generated during storage of red cells are rich in the lipid raft marker stomatin. Transfusion. 2008;48:451–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosman GJ, Cluitmans JC, Groenen YA, et al. Susceptibility to hyperosmotic stress-induced phosphatidylserine exposure increases during erythrocyte storage. Transfusion. 2011;51:1072–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosch FH, Werre JM, Roerdinkholder-Stoelwinder B, et al. Characteristics of red blood cell populations fractionated with a combination of counterflow centrifugation and Percoll separation. Blood. 1992;79:254–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinkla S, Brock R, Joosten I, Bosman GJ. Gateway to understanding microparticles: standardized isolation and identification of plasma membrane-derived vesicles. Nanomedicine. 2013;8:1657–68. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cluitmans JC, Gevi F, Siciliano A, et al. Red blood cell homeostasis: pharmacological interventions to explore biochemical, morphological and mechanical properties. Front Mol Biosci. 2016;3:10. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2016.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinkla S, Peppelman M, Van Der Raadt J, et al. Phosphatidylserine exposure on stored red blood cells as a parameter for donor-dependent variation in product quality. Blood Transfus. 2014;12:204–9. doi: 10.2450/2013.0106-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tissot JD, Rubin O, Canellini G. Analysis and clinical relevance of microparticles from red blood cells. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:571–7. doi: 10.1097/moh.0b013e32833ec217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werre JM, Willekens FL, Bosch FH, et al. The red cell revisited--matters of life and death. Cell Mol Biol. 2004;50:139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lutz HU, Bogdanova A. Mechanisms tagging senescent red blood cells for clearance in healthy humans. Front Physiol. 2013;4:387. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dinkla S, Novotný VM, Joosten I, Bosman GJ. Storage-induced changes in erythrocyte membrane proteins promote recognition by autoantibodies. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kriebardis AG, Antonelou MH, Stamoulis KE, et al. RBC-derived vesicles during storage: ultrastructure, protein composition, oxidation, and signaling components. Transfusion. 2008;48:1943–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonelou MH, Kriebardis AG, Stamoulis KE, et al. Apolipoprotein J/clusterin in human erythrocytes is involved in the molecular process of defected material disposal during vesiculation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karon BS, van Buskirk C, Jaben EA, et al. Temporal sequence of major biochemical events during blood bank storage of packed red blood cells. Blood Transfus. 2012;10:453–61. doi: 10.2450/2012.0099-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzounakas VL, Georgatzakou HT, Kriebardis AG, et al. Donor variation effect on red blood cell storage lesion: a multivariable, yet consistent, story. Transfusion. 2016;56:1274–86. doi: 10.1111/trf.13582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carvalho FA, de Almeida JP, Freitas-Santos T, Saldanha C. Modulation of erythrocyte acetylcholinesterase activity and its association with G protein-band 3 interactions. J Membr Biol. 2009;228:89–97. doi: 10.1007/s00232-009-9162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopes de Almeida JP, Saldanha C. Nonneuronal cholinergic system in human erythrocytes: biological role and clinical relevance. J Membr Biol. 2010;234:227–34. doi: 10.1007/s00232-010-9250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teixeira P, Duro N, Napoleão P, Saldanha C. Acetylcholinesterase conformational states influence nitric oxide mobilization in the erythrocyte. J Membr Biol. 2015;248:349–54. doi: 10.1007/s00232-015-9776-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carelli-Alinovi C, Ficarra S, Russo AM, et al. Involvement of acetylcholinesterase and protein kinase C in the protective effect of caffeine against β-amyloid-induced alterations in red blood cells. Biochimie. 2016;121:52–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]