ABSTRACT

The model opportunistic pathogen Listeria monocytogenes has been the object of extensive research, aiming at understanding its ability to colonize diverse environmental niches and animal hosts. Bacterial transcriptomes in various conditions reflect this efficient adaptability. We review here our current knowledge of the mechanisms allowing L. monocytogenes to respond to environmental changes and trigger pathogenicity, with a special focus on RNA-mediated control of gene expression. We highlight how these studies have brought novel concepts in prokaryotic gene regulation, such as the ‘excludon’ where the 5′-UTR of a messenger also acts as an antisense regulator of an operon transcribed in opposite orientation, or the notion that riboswitches can regulate non-coding RNAs to integrate complex metabolic stimuli into regulatory networks. Overall, the Listeria model exemplifies that fine RNA tuners act together with master regulatory proteins to orchestrate appropriate transcriptional programmes.

KEYWORDS: CRISPR, excludon, non-coding RNA, riboswitch, thermosensor, transcriptome

Abbreviations

- ANTAR

amiR and nasR transcriptional antiterminator regulator

- asRNA

antisense RNA

- BCAA

branched-chain amino-acid

- CAMP

cationic antimicrobial peptide

- CRISPR

clustered regularly interspersed palindromic repeats

- Crp

cyclic adenosine monophosphate receptor protein family

- Csp

cold-shock domain- family protein

- DNA

desoxyribonucleic acid

- GSH

glutathione

- lasRNA

long antisense RNA

- LLO

listeriolysin O

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- ncRNA

non-coding RNA

- ORF

open reading frame

- PTS

phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SD

Shine-Dalgarno

- sRNA

small RNA

- TIS

translation initiation site

- TSS

transcription start site

- UTR

untranslated region

Introduction

The foodborne pathogen L. monocytogenes is well known for its adaptation to a broad range of habitats, ranging from soil or wastewater to the mammalian intracellular space. This bacterial species has acquired the ability to survive and grow in a variety of temperature, pH or osmotic conditions, which allows it to colonize different niches. For instance, replication has been observed at temperatures close to zero, or up to 45°C.1 L. monocytogenes can also use distinct types of motility; whereas flagella drive swimming motility in liquid media or swarming motility on semi-solid surfaces,2 intracellular bacteria exploit actin polymerisation mechanisms to be propelled in the cytoplasm and from cell to cell.3 Upon a change in environmental conditions, bacteria can switch lifestyles through dramatic changes in their gene expression programmes, thus allowing saprophytic growth, stress response and resistance to extreme conditions, or triggering virulence properties.

Since the first completion of a Listeria genome,4 a number of transcriptomic studies have analyzed Listeria gene expression in a variety of conditions.5-8 In parallel, functional studies have revealed the role and impact of major transcriptional regulators coordinating the timing and extent of expression across gene networks in response to external cues.9 Among them, the transcription factor PrfA stands out as the master coordinator of a major virulence regulon.10,11 By improving the depth and resolution of transcriptome analysis, tiling arrays and high-throughput sequencing have more recently highlighted a significant impact of non-coding RNA (ncRNA)-mediated gene regulation in shaping bacterial gene expression.12,13

We review here how studies on transcriptional reprogramming upon L. monocytogenes switch from saprophytism to virulence have unveiled original concepts and mechanisms of gene expression control, some of which can be generalized to other bacterial species. We will not discuss extensively the housekeeping transcriptome common to other prokaryotes; we rather aim at underlining how specific regulations of L. monocytogenes non-coding transcripts and virulence genes are coordinated during infection and contribute to pathogenesis.

Protein-mediated control of virulence gene expression

PrfA, the master regulator of Listeria virulence genes

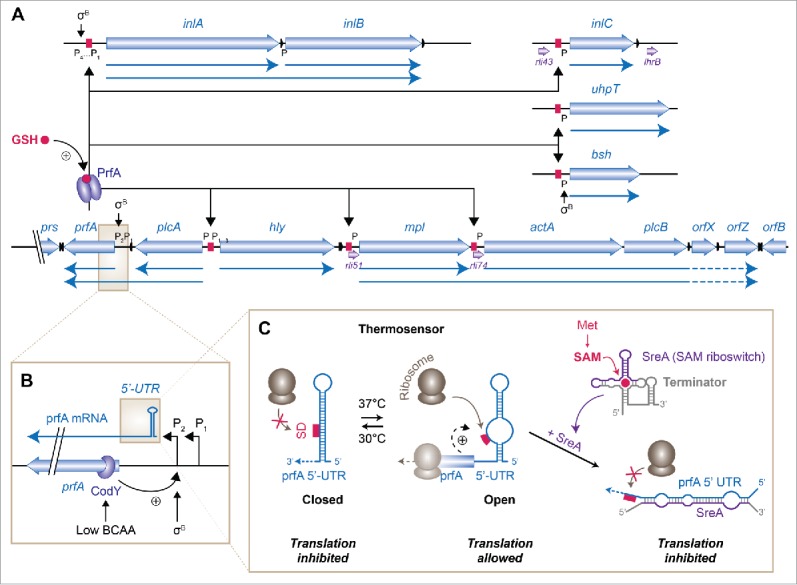

The first identified and major regulator of virulence genes in L. monocytogenes is PrfA.14,15 This protein belongs to the broad family of cyclic AMP receptor protein (Crp) transcriptional regulators that can bind DNA as dimers on specific sites in gene promoters and activate transcription.16 PrfA was initially identified for its ability to stimulate the expression of the hly gene,14 encoding the pore-forming toxin listeriolysin O (LLO),17 and later on found to regulate major genes supporting intracellular life.18 hly is co-expressed together with a PrfA-dependent virulence cluster encompassing prfA itself, as well as the genes encoding Listeria secreted phosphadidylinositol-specific (plcA)19 and broad-range (plcB)20 phospholipases, a metalloprotease (mpl),21 and ActA, the protein which promotes actin comet tail formation by recruiting the cellular actin nucleator complex Arp2/322 (Fig. 1A). PrfA also activates other genes harbouring a PrfA box in their promoter region, and located elsewhere in the genome. Among these, the genes encoding the two main surface proteins involved in Listeria entry, the internalin-family proteins InlA and InlB,23 inlC, encoding a short, secreted internalin-like protein important for cell-to-cell spread and dampening of inflammatory response, bsh, encoding a bile-salt hydrolase participating in the intestinal and hepatic phases of infection,24 and uhpT, encoding an hexose phosphate transporter, are under control of PrfA.18

Figure 1.

The PrfA regulon and its multiple control mechanisms. (A) Diagram of the main virulence cluster in L. monocytogenes and other PrfA-dependent genes, inspired from Kreft and Vázquez-Boland and de las Heras et al.9,18 Open reading frames (ORF) are highlighted in thick blue arrows, small RNAs in purple, terminators in black. The main transcriptional units are displayed with plain blue arrows. PrfA binding sites are boxed in magenta. Positive or negative regulators are shown. P, promoter; GSH, glutathione. (B) Transcriptional control of prfA. In addition to σB-dependent regulation, transcription is enhanced by binding of CodY in the coding sequence, in response to low availability of branched-chain amino-acids (BCAA). UTR, untranslated region. (C) Control of prfA translation initiation, adapted from Cossart and Lebreton.103 At 30°C, the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence of prfA mRNA is masked from ribosomes by a closed stem-loop structure. At 37°C, a change in the conformation of the 5′-UTR liberates the SD and allows translation initiation. Binding of ribosomes to the SD is further stabilised by the 20 first codons of the ORF. The SreA small RNA, which is the product of a S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) riboswitch, can also base-pair with prfA 5′-UTR and block access of ribosomes to the SD sequence.

The production and activity of PrfA are critical for, but not exclusive to, the intracellular stages of infection. Like for other members of the Crp family, PrfA activity is regulated by allostery. For more than 20 years, the nature of the small-molecule activator, which could specifically activate PrfA in the host cell cytosol, has remained elusive. PrfA activity was early known to be inhibited by environmental cellobiose, via an unknown indirect mechanism;25 whereas a proteinase K-sensitive component present in human cell extracts could stimulate PrfA activity.26 An elegant genetic screen using a Listeria strain unable to replicate when PrfA is active has recently revealed that the long-sought activating ligand was glutathione (GSH).27 Intra-bacterial GSH levels depend on the uptake of this tripeptide from the host cell, and also on the intracellular production by the bacterial glutathione synthetase GshF. Of note, the expression of gshF is induced in the spleen of infected mice;28 its regulators are unknown, and might for instance respond to sensing of redox conditions by the bacteria in their host.

PrfA activity has also been linked to the nature of the sugar sources available to the bacteria.29 In the environment, the uptake of carbohydrates requires the phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system (PTS) before they enter glycolysis; in contrast, in the host cell cytoplasm, bacteria can readily import phosphorylated hexoses via UhpT,30 and use them in the pentose phosphate pathway. It has been postulated that PrfA would be sequestered in an inactive state when the permeases in the PTS system are phosphorylated.31 Clear mechanistic evidence of this model is still missing, as well as a possible link between sugar uptake and GSH metabolism.

prfA transcription is also regulated by RNA elements, as further described below.

σB, a stress-responsive activator of Listeria virulence genes in the intestine

The transcription of a large number of L. monocytogenes virulence genes is additionally controlled by the stress-responsive, alternative sigma factor SigmaB (σB).32,33 σB is essential for the activation of an array of virulence genes in the intestine.34 This regulon encompasses factors required for survival in the intestinal environment, such as Bsh, or crossing the intestinal barrier, such as InlA. Activation of the σB regulon is not restricted to L. monocytogenes pathogenic phase; as for other bacilli, it is induced in stationary phase when bacteria are cultivated in broth.35 Importantly, the PrfA and σB regulons are significantly overlapping. This is partly due to the fact that σB regulates PrfA expression,36 but also a number of genes are targets of both regulators.37

VirR, a coordinator of surface components modification and antimicrobial resistance

Apart from these two main players, other transcriptional regulators contribute to the fine-tuning of gene expression during infection. Even though our goal here is not to describe their regulons extensively, we will briefly discuss how some of them contribute to transcriptional reprogramming. Among those, the 2-component system VirR/S controls the expression of 17 genes, including its own operon.38 A virR deletion mutant is defective for virulence in mice and entry in cultured epithelial cells. The expression of VirR/S and its regulated genes is enhanced in the spleen of infected mice.28 In addition, VirR/S participates to resistance to a variety of antimicrobials and food preservatives.39 In line with this, most of the characterized VirR/S targets contribute to the modification of bacterial surface components and/or provide resistance to antimicrobial peptides:39 The dlt operon encodes proteins involved in D-alanylation of lipoteichoic acids and has been shown to be required for virulence;40 lmo1695 and lmo1696 encode respectively MprF, which can lysinylate phospholipids and confer resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs),41 and a putative glycopeptide antibiotic resistance protein of the VanZ family;42 last, the ABC transporter AnrAB is involved in resistance to the bacteriocin nisin, and to several other antibiotics.43 VirR/S thus appears as a coordinator of bacterial protection against membrane and envelope damage, and against antimicrobials produced by its competitors or its host, or used in food preservation.

MogR, the repressor of motility genes

L. monocytogenes switches off its flagella genes during murine infection, extracellular growth at 37°C or intracellular growth.44 The bacterial flagella play a role in two forms of the bacterial life; they allow the swimming motility of pelagic bacteria in liquid environment; they are also required for the colonisation of surfaces and biofilm formation.45,46 Expression of flagella genes is controlled by a complex network of transcriptional regulators. Among them, the motility gene repressor MogR and the glycosyltransferase and motility anti-repressor GmaR antagonize to allow flagellin production at 30°C, and repress it at 37°C.47,48 MogR acts as a repressor on the transcription of both flagella genes and gmaR. At low temperature, the anti-repressor GmaR interacts with MogR and inhibits it, thereby positively regulating its own expression, and allowing the transcription of the motility regulon. At higher temperature, the thermosensitive interaction between MogR and GmaR is disrupted, GmaR is degraded, and MogR represses the regulon. There is also evidence that motility is under a negative control by PrfA, probably via an indirect regulation.49,50

CodY, a regulator of Listeria metabolism in host cells

Intracellular growth conditions also require the adaptation of carbon uptake and nitrogen assimilation to available sources. The nutrient-responsive regulator CodY coordinates the de novo synthesis of branched-chain amino-acids (BCAA) and sugar catabolism with the onset of virulence programmes and regulation of motility.51-53 Importantly, CodY activates the transcription of prfA by direct binding in its coding sequence, 15 nucleotides downstream of the start codon, and thereby stimulates the expression of virulence genes in response to low availability of BCAA (Fig. 1B).54

RNA-mediated control of virulence gene expression

In addition to the action of transcriptional regulators, in- 185 depth studies of the bacterial gene expression switches triggered by environment changes have highlighted a large variety of RNA-mediated regulatory mechanisms of bacterial gene expression.

Role of 5′-UTRs in virulence gene expression

5′-untranslated regions (UTR) have been shown to control the expression of several L. monocytogenes virulence genes at the post-transcriptional level. For instance, the 5′-UTRs of the actA, hly, inlA and iap are required for optimal expression of these virulence genes by affecting their stability or translation.55

Regulation of mRNA stability by 5′-UTRs

The integrity of the 5′-UTR region of hly influences the abundance of mRNA (mRNA) as well as protein production, hemolytic activity and virulence, suggesting that these sequences participate in the stabilization of the transcript.56 Based on these findings, the 5′-UTR of the hly gene has been successfully used to enhance expression of genes in L. monocytogenes strains for research.57 However, the stabilization mechanism, which could rely on the protection from nucleases via the formation of secondary structures or binding of protective proteins, is still unknown.

The 5′-UTR of inlA also controls the expression of the inlAB transcript.58 This regulation relies on the presence of a motif similar to a Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence, located immediately downstream of the transcription start site (TSS) and far upstream of the TIS. This sequence is proposed to act as a SD mimic named stability-SD (STAB-SD), which would stabilize transcripts by sequestering ribosomes.55,59 STAB-SD motifs are also found upstream of the inlC and uhpT transcripts;55 however, their role on the expression of these two virulence genes has not been explored.

Regulation of translation initiation by 5′-UTRs

Expression of the iap gene, encoding the invasion-associated murein hydrolase p60, is regulated via a post-transcriptional mechanism.60 The 5′-UTR of iap is thought to form a secondary structure masking the SD sequence and/or translation initiation site (TIS) and controlling translational initiation, depending on the binding of a yet-unknown ligand.

actA expression is also regulated via its 5′-UTR.61 The tight post-transcriptional control of ActA production is crucial for the bacterial ability to form comet tails and spread from cell to cell, independently of PrfA-mediated transcriptional activation in the cytosol. Note that the genomic region located 5′ of actA has been annotated as a small RNA (Rli74, Fig. 1);62 however, it has also been proposed that Rli74 represents in fact the long regulatory 5′-UTR of actA.12 The status of this Rli remains so far unclear.

Relatively long 5′-UTRs in other virulence genes suggest that more candidates could be the object of similar modes of regulation, which remain to be characterized.12,34,55 Last, regulatory regions affecting translation can extend within the coding sequence of virulence genes. This was shown for prfA, whose 20 first codons enhance ribosomal binding to the SD region and are thus required for optimal translation initiation.63

The PrfA RNA thermosensor

Soon after the characterization of PrfA as an activator of the expression of hly,14 the expression of PrfA-dependent virulence genes was found to be thermoregulated in L. monocytogenes.64 Indeed at low temperatures, prfA is transcribed but very low amounts of PrfA proteins are produced.25 The mechanism of this regulation relies on a thermosensor, consisting of a secondary structure in the 5′-UTR of prfA transcripts that controls translation depending on the temperature (Fig. 1C).65 At environmental temperatures (30°C or below), the SD sequence of PrfA is sequestered into a closed stem-loop structure, which blocks the access of the small ribosomal subunit and thereby inhibits translation initiation. During infection of warm-blooded organisms, the temperature rise to 37°C opens the stem-loop and unmasks the TIS. PrfA is then produced, which results in the transcription of the PrfA regulon; by doing so, PrfA also stimulates its own transcription, by acting on the plcA promoter, thus generating a bicistronic plcA-pfrA transcript (Fig. 1A).

The example of the PrfA thermosensor is a good illustration that RNA structures are highly sensitive to temperature, and that their folding or unfolding can affect their function. For organisms that can live in a wide range of temperatures like Listeria, the ability to resolve RNA structures is crucial to resist cold shock and allow cold growth; in line with this, mutants in helicase genes usually display cold-sensitive phenotypes.66 Two families of RNA binding proteins participate in cold-stress adaptation in Listeria: the cold-shock domain family proteins (Csps) CspA, CspB and CspD, and the DExD-box, ATP-dependent RNA helicase family proteins CshA, Lmo1246, Lmo1450 and Lmo1722.67,68

Expression of Csps and helicases is induced during cold stress at 3 or 4°C.67,69,70 In addition, deletion mutants of cspA, cspD, cshA, lmo1450 or lmo1722 are impaired in growth and motility at low temperature.67,68,70 Lmo1722, and to a lesser extent CshA and Lmo1450, are involved in the maturation of the large ribosomal subunit, processing of 23S rRNA (rRNA) and maintenance of active translation.68,71 The helicases are also required for PrfA-dependent expression of virulence genes actA, hly, inlA and inlB, and for hemolytic activity.68,72 However, the expression of PrfA itself is not affected in helicase mutants, suggesting that Listeria helicases promote PrfA activity on its targets.

Riboswitches

Riboswitches consist in short RNA sequences that change conformation upon binding of a dedicated ligand, and adjust the expression of certain operons according to the availability of specific metabolites. Typical riboswitches are parts of the 5′-UTRs of genes, where they can for instance act as transcription terminators or anti-terminators, or control the access of the small ribosomal subunit to the SD sequence.73 The structure of these motifs is highly conserved across species, allowing their rather accurate prediction throughout genomes and their annotation in databases like Rfam (http://rfam.xfam.org).81

The genome of L. monocytogenes encompasses at least 55 validated or candidate riboswitches, responding to 13 distinct ligands.12 The identification of the ‘on’ and ‘off’ states of 40 of these riboswitches by transcriptome analysis using tiling arrays has pinpointed that functional riboswitches can also be located in 3′-UTRs. For instance, a lysine riboswitch (LysRS), which controls the transcription of the downstream gene lmo0798 encoding a lysine transporter, also acts as a transcription terminator for the upstream gene lmo0799.34 Likewise, several other riboswitches from different families were proposed to act as transcription terminators.

A riboswitch-regulated antisense RNA

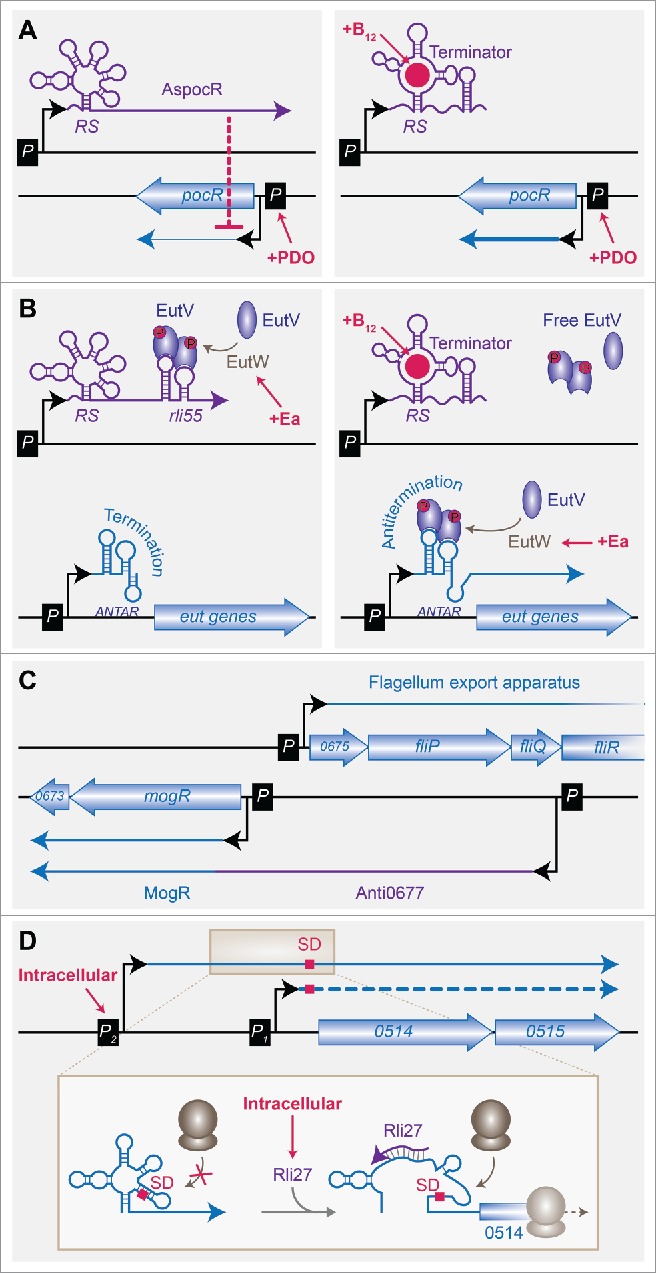

A vitamin B12-dependent riboswitch, positioned downstream of the lmo1149 gene, is in a convergent orientation with the gene lmo1150 encoding a transcriptional regulator, PocR (Fig. 2A). Contrary to the initial assumption that this riboswitch was a transcriptional terminator of lmo1149, the riboswitch controls the transcription of an antisense RNA to pocR (AspocR), and thereby positively regulates PocR expression when vitamin B12 is available.74

Figure 2.

Novel RNA-mediated regulations of L. monocytogenes gene expression. (A) Control of AsPocR by a B12 riboswitch, adapted from Cossart and Lebreton.103 (Left) In absence of B12, full-length AspocR is produced and inhibits pocR expression. (Right) In presence of B12, the transcription of AsPocR is terminated prematurely by the B12 riboswitch (RS), and transcription of pocR is allowed, provided that propanediol (PDO) is also present in the medium. (B) Sequestration of an antiterminator by a B12 riboswitch, inspired from Mellin et al.75 In presence of Ethanolamine (Ea), the antiterminator EutV is phosphorylated by EutW and activated. (Left) In absence of B12, full-length Rli55 is produced and sequesters active EutV. The transcription of eut genes is prevented by early termination at the ANTAR elements. (Right) In presence of B12, the transcription of Rli55 is terminated prematurely by the B12 riboswitch. Free phosphorylated EutV dimers can then bind the ANTAR element and mediate antitermination, allowing the expression of eut genes. (C) The mogR-fli locus excludon, adapted from Cossart and Lebreton.103 mogR is encompassed by 2 transcripts. In the longest one, the 5′-UTR of upstream of MogR coding sequence also acts as an antisense RNA, Anti0677, overlapping the fli operon. The two divergent transcriptional units encode proteins of opposite functions: MogR is a transcriptional repressor of flagellum genes, whereas Fli proteins participate in the flagellum export apparatus. (D) Rli27 allows the intracellular-specific translation of an alternative transcript, inspired from Quereda et al.94 Extracellular bacteria express mainly lmo0514-lmo0515 from the constitutive P1 promoter. An alternative, long mRNA is produced in low amounts from P2, but ribosomes cannot access the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD). In cells, the P2 promoter is activated, and Rli27 is expressed. Base-pairing of Rli27 with the 5′-UTR of the long transcript allows ribosome binding and translation to proceed.

The transcriptional factor PocR is required for the expression, in presence of propanediol, of two operons: pdu, which governs propanediol utilization, and cob, which is involved in vitamin B12 biosynthesis. The two functions are intimately linked, due to the need of B12 as a cofactor for propanediol catabolism. The B12-dependent antisense-mediated regulation of pocR ensures that pdu genes are expressed only when the substrate and the cofactor are available together. When propanediol is present but in absence of B12, PocR expression is partially repressed by AspocR. These low levels of PocR are however sufficient to stimulate the expression of cob genes, allowing the synthesis of the cofactor while pdu genes are repressed.

Sequestration of an antiterminator by a riboswitch-regulated ncRNA

The investigation of the role of other B12-regulated ncRNAs in L. monocytogenes has shed light on a new type of RNA-mediated regulation in the ethanolamine utilization operon (eut).75 This operon is activated in the presence of ethanolamine via a two-component system, EutVW, where EutW is a sensor kinase, and EutV acts as an antiterminator. In presence of ethanolamine, EutW activates EutV. This is however not sufficient to upregulate the operon, which requires ethanolamine and vitamin B12 to be transcribed. This can occur due to the presence, upstream of the operon, of a B12-riboswitch controlling the expression of a small RNA (sRNA), Rli55 (Fig. 2B).

In the absence of B12, full length Rli55 is transcribed; it contains an EutV binding site, consisting of a structural motif similar to ANTAR (amiR and nasR transcriptional antiterminator regulator) elements. Rli55-ANTAR sequesters EutV and thereby prevents the transcription of eut genes. In the presence of B12, the riboswitch terminates the transcription of Rli55 upstream of the ANTAR element. EutV is no longer titrated and can bind ANTAR elements in the transcripts of its target genes, thus allowing their antitermination. As for propanediol catabolism, enzymes of the ethanolanine utilization pathway use vitamin B12 as a cofactor; here again, the dual regulation of the operon ensures the optimal timing of gene expression with regards to the availability in metabolites. A similar mechanism has been identified in Enterococcus faecalis, where the small RNA EutX sequesters EutV in absence of B12, whereas it is terminated by a B12 riboswitch when the concentration of this vitamin increases.76

Interestingly, the three operons pdu, cob and eut are significantly up-regulated in the intestinal lumen of mice during orally-acquired listeriosis.7 This induction implies that the gut environment provides L. monocytogenes with the metabolites required for these pathways. Several other enteropathogens, such as Salmonella enterica, Enterococcus faecalis and Clostridium perfringens harbour similar operons, whereas these functions are deficient in most bacterial species from the microbiota;77 this has been proposed to confer a metabolic advantage to pathogenic species in competition with the gut flora. In agreement with this hypothesis, competition experiments between lactobacilli and L. monocytogenes during intestinal infection led to an even stronger induction of the 3 operons,7 suggesting that Listeria can adjust its carbon metabolism in presence of commensal competitors toward unshared carbon sources.

Regulation of antibiotic resistance by conditional transcription termination

Our current repertoire of known bacterial riboswitches and other conditional, premature transcription terminators (attenuators, antiterminators) is far from being exhaustive. A novel, unbiased approach was recently developed for ab initio discovery of regulated, premature termination events, by systematic sequencing of RNA 3′-ends (term-seq).78 In addition to validating known or predicted conditional terminators in Bacillus subtilis, L. monocytogenes and E. faecalis, this work has revealed premature termination events that can be alleviated by antibiotics. In L. monocytogenes, termination of Rli53 and Rli59, in the 5′-UTR of lmo0919 and lmo1652 respectively, is hampered by sub-lethal doses of translation-inhibiting antibiotics. Rli53 behaves as a terminator/anti-terminator structure, specifically responding to lincomycin. In presence of the antibiotic, Rli53 switches to an open state and allows transcriptional read-through into the downstream ORF. The latter encodes an ABC transporter providing resistance to lincomycin.

By applying term-seq to oral commensals submitted to short antibiotic treatment, similar patterns of regulation of antibiotic-resistance genes in gram-positive members of the oral microbiota could be identified, illustrating that conditional transcription termination represents a general feature in the set-up of antibiotic resistance. The use of this pipeline should allow the identification of unknown regulators responding to diverse ligands in the coming years, and provide a more accurate overview of the variety of RNA-mediated mechanisms used by bacteria to adapt to their environment. This expanding toolkit could also be used in the design of specific biosensors in diagnostic or industry.79

Cis-regulation by antisense transcription

Cis-antisense RNAs in Listeria monocytogenes

Pioneering transcriptomic analysis based on the use of macroarrays with a limited number of oligonucleotide probes per transcripts allowed the differential analysis of L. monocytogenes gene expression, depending on growth conditions, strains or mutations in regulators.80 The increase in resolution provided first by tiling arrays, soon followed by high-throughput sequencing of full-length mRNAs or 5′-ends, has allowed the precise mapping of TSSs and transcript lengths, and the identification of novel transcriptional units.34,35,81

The resulting thorough characterization of Listeria transcripts have revealed an unexpected wealth of ncRNAs, a number of which actively participate in co- or post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Among them, around a hundred sequences are transcribed in opposite orientation to another transcript.13 These cis-encoded antisense RNAs (asRNA) are potential negative regulators of gene expression on the opposite strand. We will not detail here the various possible mechanisms of antisense-RNA mediated repression, which have been extensively covered by others,82 and include transcriptional interference, transcriptional attenuation, alteration of transcript stability, and translational inhibition. L. monocytogenes asRNAs vary in length from 30 to several thousands of nucleotides. They can be antisense to known open reading frames (ORF), or occur due to the overlap of 3′-UTRs of convergent genes, or 5′-UTRs of divergent genes.

mRNAs with a dual function: the excludon concept

An original class of divergent transcriptional units was shown to rule the expression of operons encoding opposite functions, and consequently named “excludon.”81 Typically, an excludon corresponds to a situation where the long 5′-UTR of one transcript overlaps with the coding sequence of the upstream unit, which is transcribed in the other direction (Fig. 2C). The 5′-UTR thereby acts as a long antisense RNA (lasRNA) and inhibits the expression of the divergent operon, while its own downstream sequence can be translated. This situation where a transcript can exert a dual function, as a mRNA and a non-coding antisense RNA, has first been described at the mogR locus.34 As indicated above, MogR is a negative regulator of flagella synthesis genes, which are induced in the environment and repressed during infection. Among these, the fli operon, encoding proteins required for the synthesis of the flagellum export apparatus, is transcribed opposite of the mogR operon. The latter can be transcribed from two distinct promoters: a constitutive promoter is located just upstream of mogR coding sequence; an additional σB-dependent promoter is located within the coding sequence of fliQ, and thus gives rise to a long 5′-UTR antisense to fliQ and fliP. Abrogation of the long mogR transcript, by either mutation in the σB-dependent promoter or deletion of sigB, enhances the expression of fliP.

High resolution transcriptomics has extended the concept to 13 other pairs of divergent operons throughout the genomes of L. monocytogenes, involved in a variety of functions such as permeases versus efflux pumps, utilization of distinct carbon sources, and nucleic acids metabolism.8,83 Similar divergent operons, where the 5′UTR of one gene extends into the coding sequence of the upstream gene, and thus possibly forming excludons, were identified in other members of the Listeria genera, as well as in more distant bacterial species.83,84

Trans-acting functions of small RNAs

The Listeria genome encodes many ncRNAs that share a partial complementarity with targets located elsewhere in the genome, and can regulate them in trans. More than 150 putative trans-acting sRNAs, named Rli, have been annotated to date.13,85 The expression of several of them is enhanced or repressed in a mouse model of listeriosis or intracellularly; in addition, deletion mutants of rliB, rli31, rli33-1, rli38 and rli50 impair virulence in this mouse model of listeriosis, in Galleria mellonella, or during growth in macrophages, suggesting a regulatory function in virulence.34,62 However, the functions of most Listeria sRNAs remain uncharacterized.

Hfq-dependent small RNAs control chitinase activity

In Gram-negative bacteria, most trans-acting sRNAs form a complex with Hfq, a RNA chaperone required for their function.86 This does not seem to be the rule in Gram-positive bacteria, including in L. monocytogenes, where Hfq is dispensable for the stability of several sRNAs.87 Nevertheless, a Δhfq mutant is affected in stress tolerance, and in virulence in mice.88 Furthermore, 3 sRNAs could be co-immunoprecipitated with Hfq: The Listeria Hfq-binding RNAs LhrA (Rli17), B (Rli14) and C (Rli4).89 Among them, LhrA directly controls the expression of lmo0302, lmo0850 and the chitinase gene chiA. Hfq is required for the base-pairing of LhrA with lmo0850 mRNA, which induces the degradation of its target.90 LhrA and Hfq also interfere with the recruitment of the ribosomes to lmo0302 and chiA mRNAs, thus repressing their translation.91 LhrA thereby acts as a repressor of chitinolytic activity, which contributes to L. monocytogenes pathogenicity in mice.92

A small RNA antagonizes a global post-transcriptional regulator

The virulence-associated sRNA Rli31 was recently found to bind the 5′-UTR of spoVG mRNA, as well as SpoVG itself, a RNA-binding protein and a global post-transcriptional regulator of motility, carbohydrate metabolism and virulence genes.93 Deletions of rli31 and spoVG have opposite phenotypes for lysozyme resistance and virulence in a mouse listeriosis model and are mutual suppressors, suggesting that their functions are antagonistic. The molecular mechanisms underlying these opposite effects will require further investigation.

A small RNA stimulates the translation of an alternative transcript

Another sRNA, Rli27, can base-pair within the 5′-UTR region of lmo0514, encoding a bacterial cell-wall protein (Fig. 2D).94 lmo0514 can be encoded as two transcripts differing in their 5′-UTR; the shortest one is constitutive, whereas the longest one as well as Rli27 are induced in intracellular bacteria. Binding of Rli27 to the long 5′-UTR unmasks the SD sequence and promotes translation. The two levels of regulation, transcriptional via the two distinct promoters, and translational via Rli27, act in synergy to sharply enhance the production of Lmo0514 protein when bacteria reach the host cytosol.

Short transcripts generated by a riboswitch can act in trans

In addition to the cis-regulating activity of riboswitches on transcriptional regulation, they can give rise to small RNAs with a trans-acting function. This was shown for 2 S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) riboswitches, SreA and SreB.95 SreA controls the expression of genes encoding an ABC transporter (lmo2419 to lmo2417) during the switch from exponential (high intracellular concentration of SAM) to stationary phase (low SAM concentration). SAM binding to the RNA aptamer causes early transcription termination after 229 nucleotides. This short SreA riboswitch transcript can base-pair, in trans, with the 5′-UTR region of prfA mRNA, mask the SD sequence and impede translation initiation (Fig. 1C). Conversely, PrfA is a transcriptional activator of SreA. The short riboswitch-containing RNA is thus part of a negative feedback loop on the expression of the main virulence gene regulator.

Similarly, a second short transcript released by a SAM riboswitch, SreB, can bind prfA mRNA and prevent its translation. Altogether, these early-terminated transcripts add an additional layer of regulation to the subtle network restricting prfA expression in the host.

PNPase binds and processes an atypical Rli/CRISPR

CRISPRs represent a widespread class of genetic loci in bacteria, which can provide acquired immunity against bacteriophages and conjugative plasmids.96 They consist of a series of repeats and spacers of fixed size acquired from an invading DNA. These loci can be transcribed, processed by cleavage within the repeats, and loaded into an effector protein complex. Base-pairing of a specific CRISPR spacer RNA sequence to a cognate nucleic acid drives the endonucleolytic activities of the effector complex to eliminate invading agents.

Listeria RliB is an atypical member of the CRISPR family, conserved at the same genomic locus in all analyzed L. monocytogenes genomes and also in other Listeria species.97 The deletion of rliB impairs virulence in mice.34 The processing and activity of CRISPRs usually depend on cas (CRISPR-associated) genes, transcribed in the immediate vicinity of CRISPR loci. In contrast, no cas genes are found in the neighborhood of RliB.97 Biochemistry experiments have shown that RliB is stably bound by, and also a substrate of, Listeria polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase), which is likely responsible for its processing into a mature form. Last, in L. monocytogenes strains encoding a complete CRISPR-cas system elsewhere in the genome, RliB can hamper, albeit modestly, the uptake of exogenous DNA corresponding to its spacer sequences, suggesting that Cas proteins from another locus can complement a defective one.

Conclusions

Upon infection, the timely set-up of virulence programmes by Listeria monocytogenes relies on a wide variety of control mechanisms acting at all steps of gene expression as listed above. Among the identified regulations, a striking observation is the extreme versatility of mechanisms controlling PrfA regulon. prfA transcription is activated by σB in response to stress, by CodY in response to BCAA depletion, and by PrfA itself in a positive feedback loop (Fig. 1). Its translation is controlled by temperature due to a thermosensor in its 5′-UTR region, and tuned by the trans-acting riboswitches SreA and SreB. PrfA activity is dependent on the binding of glutathione, the levels of which increase when bacteria reach the cytosol. We have also mentioned that PrfA target genes actA, hly, inlA and inlB are the object of specific post-transcriptional regulation. This apparent wealth of mechanisms might reflect the fact that the PrfA regulon has been more studied than others, due to its primary role in virulence. Nonetheless, it stresses the crucial importance of a fine-tuning of the expression of virulence genes, limiting their effects to the adequate time and place. In agreement with this, a mutant in prfA which leads to constitutive PrfA activity, enhanced invasion in cell cultures and hyper-virulence in mice (PrfA*), displays impaired growth in rich medium.98 In addition, the cross-coordination of the PrfA regulon with other pathways attests of the ability of invasive bacteria to integrate multiple signals, in order to adapt their metabolism, growth and pathogenic potential to their new environment.

Further studies will be required to fully document the molecular basis of virulence gene expression regulation. For instance, the precise post-transcriptional mechanism of regulation by many 5′-UTRs is still unknown; most excludons and their role in adaptation to environmental conditions are uncharacterized; our understanding of the influence of in vivo cues and commensals on Listeria transcriptome remains fragmentary; research on the comparative role of transcriptional regulation in virulence in between L. monocytogenes strains is only in its infancy, and could provide a ground for pathogenic variability among closely-related isolates.99

Beyond gene expression regulation, the denomination small RNA does not necessary mean non-coding RNA. Among the remaining sRNAs to be characterized in Listeria, 19 might prove to be coding for small peptides.12 Last, an emerging theme in the field focuses on the ability of bacterial mRNAs and ncRNAs to be modified, like what was long known for rRNAs and tRNAs (tRNAs).100 Base edition offers a potent lever for flexibility in transcript functions, the impact of which on bacterial physiology and virulence is likely underestimated, and will probably be better assessed in the coming years.

We have discussed here the role of transcription reprogramming and non-coding RNAs in Listeria monocytogenes virulence. An intriguing hypothesis is whether RNA molecules could also play a role as virulence effectors. In theory, this is not excluded, since short RNA fragments can be secreted by Listeria into the cytoplasm of infected macrophages or epithelial cells, depending on the SecA2 secretion system.101,102 However, so far only a role as activators of the innate immune RNA sensor RIG-I was identified for these RNAs. An active function of these secreted nucleic acids is still to be found.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

Work in the laboratory of P.C. received financial support from European Research Council advanced grant BacCellEpi-670823, ERA-NET Infect-ERA ProAntiLis, Investissements d'Avenir BACNET (ANR-10-BINF-0201) and IBEID (ANR-10-LABX-62-01), and Fondation le Roch Les Mousquetaires. The laboratory of A.L. is supported by Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM-AJE20131128944), Inserm ATIP-Avenir, Mairie de Paris (Program Émergences – Recherche médicale), and Investissements d'Avenir MemoLife (ANR-10-LABX-54). P.C. is a Senior International Research Scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Membré J-M, Leporq B, Vialette M, Mettler E, Perrier L, Thuault D, Zwietering M. Temperature effect on bacterial growth rate: quantitative microbiology approach including cardinal values and variability estimates to perform growth simulations on/in food. Int J Food Microbiol 2005; 100:179-86; PMID:15854703; http://dx.doi.org/15302931 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundling A, Burrack LS, Bouwer HGA, Higgins DE. Listeria monocytogenes regulates flagellar motility gene expression through MogR, a transcriptional repressor required for virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101:12318-23; PMID:15302931; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0404924101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cossart P, Kocks C. The actin-based motility of the facultative intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 1994; 13:395-402; PMID:7997157; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaser P, Frangeul L, Buchrieser C, Rusniok C, Amend A, Baquero F, Berche P, Bloecker H, Brandt P, Chakraborty T, et al.. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 2001; 294:849-52; PMID:11679669; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1063447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cossart P, Archambaud C. The bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes: an emerging model in prokaryotic transcriptomics. J Biol 2009; 8:107; PMID:20053304; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/jbiol202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soni KA, Nannapaneni R, Tasara T. The contribution of transcriptomic and proteomic analysis in elucidating stress adaptation responses of Listeria monocytogenes. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2011; 8:843-52; PMID:21495855; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/fpd.2010.0746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archambaud C, Nahori M-A, Soubigou G, Bécavin C, Laval L, Lechat P, Smokvina T, Langella P, Lecuit M, Cossart P. Impact of lactobacilli on orally acquired listeriosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109:16684-9; PMID:23012479; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1212809109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultze T, Hilker R, Mannala GK, Gentil K, Weigel M, Farmani N, Windhorst AC, Goesmann A, Chakraborty T, Hain T. A detailed view of the intracellular transcriptome of Listeria monocytogenes in murine macrophages using RNA-seq. Front Microbiol 2015; 6:1199; PMID:26579105; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.las Heras de A, Cain RJ, Bielecka MK, Vázquez-Boland JA. Regulation of Listeria virulence: PrfA master and commander. Curr Opin Microbiol 2011; 14:118-27; PMID:21388862; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mib.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milohanic E, Glaser P, Coppée J-Y, Frangeul L, Vega Y, Vázquez-Boland JA, Kunst F, Cossart P, Buchrieser C. Transcriptome analysis of Listeria monocytogenes identifies three groups of genes differently regulated by PrfA. Mol Microbiol 2003; 47:1613-25; PMID:12622816; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xayarath B, Freitag NE. Optimizing the balance between host and environmental survival skills: lessons learned from Listeria monocytogenes. Future Microbiol 2012; 7:839-52; PMID:22827306; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2217/fmb.12.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellin JR, Cossart P. The non-coding RNA world of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. RNA Biol 2012; 9:372-8; PMID:22336762; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/rna.19235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schultze T, Izar B, Qing X, Mannala GK, Hain T. Current status of antisense RNA-mediated gene regulation in Listeria monocytogenes. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2014; 4:135; PMID:25325017; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leimeister-Wächter M, Haffner C, Domann E, Goebel W, Chakraborty T. Identification of a gene that positively regulates expression of listeriolysin, the major virulence factor of Listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:8336-40; PMID:2122460; http://dx.doi.org/1662763 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mengaud J, Dramsi S, Gouin E, Vázquez-Boland JA, Milon G, Cossart P. Pleiotropic control of Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors by a gene that is autoregulated. Mol Microbiol 1991; 5:2273-83; PMID:1662763; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Körner H, Sofia HJ, Zumft WG. Phylogeny of the bacterial superfamily of Crp-Fnr transcription regulators: exploiting the metabolic spectrum by controlling alternative gene programs. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2003; 27:559-92; PMID:14638413; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00066-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamon MA, Ribet D, Stavru F, Cossart P. Listeriolysin O: the Swiss army knife of Listeria. Trends Microbiol 2012; 20:360-8; PMID:22652164; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tim.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreft J, Vázquez-Boland JA. Regulation of virulence genes in Listeria. Int J Med Microbiol 2001; 291:145-57; PMID:11437337; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1078/1438-4221-00111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leimeister-Wächter M, Domann E, Chakraborty T. Detection of a gene encoding a phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C that is co-ordinately expressed with listeriolysin in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 1991; 5:361-6; PMID:1645838; http://dx.doi.org/8384163 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02117.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vázquez-Boland JA, Kocks C, Dramsi S, Ohayon H, Geoffroy C, Mengaud J, Cossart P. Nucleotide sequence of the lecithinase operon of Listeria monocytogenes and possible role of lecithinase in cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun 1992; 60:219-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poyart C, Abachin E, Razafimanantsoa I, Berche P. The zinc metalloprotease of Listeria monocytogenes is required for maturation of phosphatidylcholine phospholipase C: direct evidence obtained by gene complementation. Infect Immun 1993; 61:1576-80; PMID:8384163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kocks C, Gouin E, Tabouret M, Berche P, Ohayon H, Cossart P. L. monocytogenes-induced actin assembly requires the actA gene product, a surface protein. Cell 1992; 68:521-31; PMID:1739966; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90188-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pizarro-Cerda J, Kühbacher A, Cossart P. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes in mammalian epithelial cells: an updated view. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2:a010009-a010009; PMID:23125201; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a010009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dussurget O, Cabanes D, Dehoux P, Lecuit M, Buchrieser C, Glaser P, Cossart P. European Listeria Genome Consortium. Listeria monocytogenes bile salt hydrolase is a PrfA-regulated virulence factor involved in the intestinal and hepatic phases of listeriosis. Mol Microbiol 2002; 45:1095-106; PMID:12180927; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renzoni A, Klarsfeld A, Dramsi S, Cossart P. Evidence that PrfA, the pleiotropic activator of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes, can be present but inactive. Infect Immun 1997; 65:1515-8; PMID:9119495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renzoni A, Cossart P, Dramsi S. PrfA, the transcriptional activator of virulence genes, is upregulated during interaction of Listeria monocytogenes with mammalian cells and in eukaryotic cell extracts. Mol Microbiol 1999; 34:552-61; PMID:10564496; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reniere ML, Whiteley AT, Hamilton KL, John SM, Lauer P, Brennan RG, Portnoy DA. Glutathione activates virulence gene expression of an intracellular pathogen. Nature 2015; 517:170-3; PMID:25567281; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature14029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Camejo A, Buchrieser C, Couvé E, Carvalho F, Reis O, Ferreira P, Sousa S, Cossart P, Cabanes D. In vivo transcriptional profiling of Listeria monocytogenes and mutagenesis identify new virulence factors involved in infection. PLoS Pathog 2009; 5:e1000449; PMID:19478867; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freitag NE, Port GC, Miner MD. Listeria monocytogenes - from saprophyte to intracellular pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009; 7:623-8; PMID:19648949; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrmicro2171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chico-Calero I, Suárez M, González-Zorn B, Scortti M, Slaghuis J, Goebel W, Vázquez-Boland JA. European Listeria Genome Consortium. Hpt, a bacterial homolog of the microsomal glucose- 6-phosphate translocase, mediates rapid intracellular proliferation in Listeria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99:431-6; PMID:11756655; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.012363899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joseph B, Mertins S, Stoll R, Schär J, Umesha KR, Luo Q, Müller-Altrock S, Goebel W. Glycerol metabolism and PrfA activity in Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol 2008; 190:5412-30; PMID:18502850; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JB.00259-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiedmann M, Arvik TJ, Hurley RJ, Boor KJ. General stress transcription factor sigmaB and its role in acid tolerance and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol 1998; 180:3650-6; PMID:9658010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kazmierczak MJ, Mithoe SC, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M. Listeria monocytogenes sigma B regulates stress response and virulence functions. J Bacteriol 2003; 185:5722-34; PMID:13129943; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JB.185.19.5722-5734.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toledo-Arana A, Dussurget O, Nikitas G, Sesto N, Guet-Revillet H, Balestrino D, Loh E, Gripenland J, Tiensuu T, Vaitkevicius K, et al.. The Listeria transcriptional landscape from saprophytism to virulence. Nature 2009; 459:950-6; PMID:19448609; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature08080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oliver HF, Orsi RH, Ponnala L, Keich U, Wang W, Sun Q, Cartinhour SW, Filiatrault MJ, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ. Deep RNA sequencing of L. monocytogenes reveals overlapping and extensive stationary phase and sigma B-dependent transcriptomes, including multiple highly transcribed noncoding RNAs. BMC Genomics 2009; 10:641; PMID:20042087; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2164-10-641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nadon CA, Bowen BM, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ. Sigma B contributes to PrfA-mediated virulence in Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun 2002; 70:3948-52; PMID:12065541; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3948-3952.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ollinger J, Bowen B, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ, Bergholz TM. Listeria monocytogenes sigmaB modulates PrfA-mediated virulence factor expression. Infect Immun 2009; 77:2113-24; PMID:19255187; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/IAI.01205-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandin P, Fsihi H, Dussurget O, Vergassola M, Milohanic E, Toledo-Arana A, Lasa I, Johansson J, Cossart P. VirR, a response regulator critical for Listeria monocytogenes virulence. Mol Microbiol 2005; 57:1367-80; PMID:16102006; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04776.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang J, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ, Bergholz TM. VirR-mediated resistance of Listeria monocytogenes against food antimicrobials and cross-protection induced by exposure to organic acid salts. Appl Environ Microbiol 2015; 81:4553-62; PMID:25911485; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.00648-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abachin E, Poyart C, Pellegrini E, Milohanic E, Fiedler F, Berche P, Trieu-Cuot P. Formation of D-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid is required for adhesion and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 2002; 43:1-14; PMID:11849532; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thedieck K, Hain T, Mohamed W, Tindall BJ, Nimtz M, Chakraborty T, Wehland J, Jänsch L. The MprF protein is required for lysinylation of phospholipids in listerial membranes and confers resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs) on Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 2006; 62:1325-39; PMID:17042784; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05452.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evers S, Quintiliani R, Courvalin P. Genetics of glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Microb Drug Resist 1996; 2:219-23; PMID:9158763; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collins B, Curtis N, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. The ABC transporter AnrAB contributes to the innate resistance of Listeria monocytogenes to nisin, bacitracin, and various beta-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54:4416-23; PMID:20643901; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AAC.00503-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shen A, Higgins DE. The MogR transcriptional repressor regulates nonhierarchal expression of flagellar motility genes and virulence in Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog 2006; 2:e30; PMID:16617375; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Neil HS, Marquis H. Listeria monocytogenes flagella are used for motility, not as adhesins, to increase host cell invasion. Infect Immun 2006; 74:6675-81; PMID:16982842; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/IAI.00886-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lemon KP, Higgins DE, Kolter R. Flagellar motility is critical for Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 2007; 189:4418-24; PMID:17416647; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JB.01967-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamp HD, Higgins DE. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of the GmaR antirepressor governs temperature-dependent control of flagellar motility in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 2009; 74:421-35; PMID:19796338; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06874.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamp HD, Higgins DE. A protein thermometer controls temperature-dependent transcription of flagellar motility genes in Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog 2011; 7:e1002153.; PMID:21829361; http;//dx.doi.org/9868779 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michel E, Mengaud J, Galsworthy S, Cossart P. Characterization of a large motility gene cluster containing the cheR, motAB genes of Listeria monocytogenes and evidence that PrfA downregulates motility genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1998; 169:341-7; PMID:9868779; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13338.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shetron-Rama LM, Mueller K, Bravo JM, Bouwer HGA, Way SS, Freitag NE. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes mutants with high-level in vitro expression of host cytosol-induced gene products. Mol Microbiol 2003; 48:1537-51; PMID:12791137; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03534.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bennett HJ, Pearce DM, Glenn S, Taylor CM, Kuhn M, Sonenshein AL, Andrew PW, Roberts IS. Characterization of relA and codY mutants of Listeria monocytogenes: identification of the CodY regulon and its role in virulence. Mol Microbiol 2007; 63:1453-67; PMID:17302820; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lobel L, Sigal N, Borovok I, Ruppin E, Herskovits AA. Integrative genomic analysis identifies isoleucine and CodY as regulators of Listeria monocytogenes virulence. PLoS Genet 2012; 8:e1002887; PMID:22969433; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lobel L, Herskovits AA. Systems Level Analyses Reveal Multiple Regulatory Activities of CodY Controlling Metabolism, Motility and Virulence in Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Genet 2016; 12:e1005870; PMID:26895237; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lobel L, Sigal N, Borovok I, Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL, Herskovits AA. The metabolic regulator CodY links Listeria monocytogenes metabolism to virulence by directly activating the virulence regulatory gene prfA. Mol Microbiol 2015; 95:624-44; PMID:25430920; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/mmi.12890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loh E, Gripenland J, Johansson J. Control of Listeria monocytogenes virulence by 5′-untranslated RNA. Trends Microbiol 2006; 14:294-8; PMID:16730443; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tim.2006.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen A, Higgins DE. The 5' untranslated region-mediated enhancement of intracellular listeriolysin O production is required for Listeria monocytogenes pathogenicity. Mol Microbiol 2005; 57:1460-73; PMID:16102013; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04780.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Balestrino D, Hamon MA, Dortet L, Nahori M-A, Pizarro-Cerda J, Alignani D, Dussurget O, Cossart P, Toledo-Arana A. Single-cell techniques using chromosomally tagged fluorescent bacteria to study Listeria monocytogenes infection processes. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010; 76:3625-36; PMID:20363781; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.02612-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stritzker J, Schoen C, Goebel W. Enhanced synthesis of internalin A in aro mutants of Listeria monocytogenes indicates posttranscriptional control of the inlAB mRNA. J Bacteriol 2005; 187:2836-45; PMID:15805530; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JB.187.8.2836-2845.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agaisse H, Lereclus D. STAB-SD: a Shine-Dalgarno sequence in the 5' untranslated region is a determinant of mRNA stability. Mol Microbiol 1996; 20:633-43; PMID:8736542; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5401046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Köhler S, Bubert A, Vogel M, Goebel W. Expression of the iap gene coding for protein p60 of Listeria monocytogenes is controlled on the posttranscriptional level. J Bacteriol 1991; 173:4668-74; PMID:1906869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong KKY, Bouwer HGA, Freitag NE. Evidence implicating the 5' untranslated region of Listeria monocytogenes actA in the regulation of bacterial actin-based motility. Cell Microbiol 2004; 6:155-66; PMID:14706101; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mraheil MA, Billion A, Mohamed W, Mukherjee K, Kuenne C, Pischimarov J, Krawitz C, Retey J, Hartsch T, Chakraborty T, et al.. The intracellular sRNA transcriptome of Listeria monocytogenes during growth in macrophages. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39:4235-48; PMID:21278422; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkr033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Loh E, Memarpour F, Vaitkevicius K, Kallipolitis BH, Johansson J, Sondén B. An unstructured 5'-coding region of the prfA mRNA is required for efficient translation. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:1818-27; PMID:22053088; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkr850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leimeister-Wächter M, Domann E, Chakraborty T. The expression of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes is thermoregulated. J Bacteriol 1992; 174:947-52; PMID:173222712230973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Johansson J, Mandin P, Renzoni A, Chiaruttini C, Springer M, Cossart P. An RNA thermosensor controls expression of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell 2002; 110:551-61; PMID:12230973; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00905-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iost I, Bizebard T, Dreyfus M. Functions of DEAD-box proteins in bacteria: current knowledge and pending questions. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1829:866-77; PMID:23415794; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmid B, Klumpp J, Raimann E, Loessner MJ, Stephan R, Tasara T. Role of cold shock proteins in growth of Listeria monocytogenes under cold and osmotic stress conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009; 75:1621-7; PMID:19151183; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.02154-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bäreclev C, Vaitkevicius K, Netterling S, Johansson J. DExD-box RNA-helicases in Listeria monocytogenes are important for growth, ribosomal maturation, rRNA processing and virulence factor expression. RNA Biol 2014; 11:1458-67; PMID:25590644; http;//dx.doi.org/17720827 10.1080/15476286.2014.996099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chan YC, Raengpradub S, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M. Microarray-based characterization of the Listeria monocytogenes cold regulon in log- and stationary-phase cells. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007; 73:6484-98; PMID:17720827; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.00897-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Markkula A, Mattila M, Lindström M, Korkeala H. Genes encoding putative DEAD-box RNA helicases in Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e are needed for growth and motility at 3°C. Environ Microbiol 2012; 14:2223-32; PMID:22564273; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02761.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Netterling S, Vaitkevicius K, Nord S, Johansson J. A Listeria monocytogenes RNA helicase essential for growth and ribosomal maturation at low temperatures uses its C terminus for appropriate interaction with the ribosome. J Bacteriol 2012; 194:4377-85; PMID:22707705; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JB.00348-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Netterling S, Bäreclev C, Vaitkevicius K, Johansson J. An RNA-helicase important for Listeria monocytogenes haemolytic activity and virulence factor expression. Infect Immun 2015; 84(1):67-76; PMID:25939511; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/IAI.00849-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peselis A, Serganov A. Themes and variations in riboswitch structure and function. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1839:908-18; PMID:24583553; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mellin JR, Tiensuu T, Bécavin C, Gouin E, Johansson J, Cossart P. A riboswitch-regulated antisense RNA in Listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:13132-7; PMID:23878253; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1304795110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mellin JR, Koutero M, Dar D, Nahori M-A, Sorek R, Cossart P. Sequestration of a two-component response regulator by a riboswitch-regulated noncoding RNA. Science 2014; 345:940-3; PMID:25146292; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1255083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.DebRoy S, Gebbie M, Ramesh A, Goodson JR, Cruz MR, van Hoof A, Winkler WC, Garsin DA. A riboswitch-containing sRNA controls gene expression by sequestration of a response regulator. Science 2014; 345:937-40; PMID:25146291; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1255091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tsoy O, Ravcheev D, Mushegian A. Comparative genomics of ethanolamine utilization. J Bacteriol 2009; 191:7157-64; PMID:19783625; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JB.00838-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dar D, Shamir M, Mellin JR, Koutero M, Stern-Ginossar N, Cossart P, Sorek R. Term-seq reveals abundant ribo-regulation of antibiotics resistance in bacteria. Science 2016; 352:aad9822-2; PMID:27120414; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.aad9822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mellin JR, Cossart P. Unexpected versatility in bacterial riboswitches. Trends Genet 2015; 31:150-6; PMID:25708284; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tig.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Puttamreddy S, Carruthers MD, Madsen ML, Minion FC. Transcriptome analysis of organisms with food safety relevance. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2008; 5:517-29; PMID:18673071; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/fpd.2008.0112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wurtzel O, Sesto N, Mellin JR, Karunker I, Edelheit S, Bécavin C, Archambaud C, Cossart P, Sorek R. Comparative transcriptomics of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Listeria species. Mol Syst Biol 2012; 8:583; PMID:22617957; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/msb.2012.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thomason MK, Storz G. Bacterial antisense RNAs: how many are there, and what are they doing? Annu Rev Genet 2010; 44:167-88; PMID:20707673; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sesto N, Wurtzel O, Archambaud C, Sorek R, Cossart P. The excludon: a new concept in bacterial antisense RNA-mediated gene regulation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2013; 11:75-82; PMID:23268228; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrmicro2934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oliva G, Sahr T, Buchrieser C. Small RNAs, 5' UTR elements and RNA-binding proteins in intracellular bacteria: impact on metabolism and virulence. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2015; 39:331-49; PMID:26009640; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/femsre/fuv022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sesto N, Koutero M, Cossart P. Bacterial and cellular RNAs at work during Listeria infection. Future Microbiol 2014; 9:1025-37; PMID:25340833; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2217/fmb.14.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gottesman S, Storz G. Bacterial small RNA regulators: versatile roles and rapidly evolving variations. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011; 3:a003798-8; PMID:20980440; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a003798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mandin P, Repoila F, Vergassola M, Geissmann T, Cossart P. Identification of new noncoding RNAs in Listeria monocytogenes and prediction of mRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:962-74; PMID:17259222; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkl1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Christiansen JK, Larsen MH, Ingmer H, Søgaard-Andersen L, Kallipolitis BH. The RNA-binding protein Hfq of Listeria monocytogenes: role in stress tolerance and virulence. J Bacteriol 2004; 186:3355-62; PMID:15150220; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JB.186.11.3355-3362.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Christiansen JK, Nielsen JS, Ebersbach T, Valentin-Hansen P, Søgaard-Andersen L, Kallipolitis BH. Identification of small Hfq-binding RNAs in Listeria monocytogenes. RNA 2006; 12:1383-96; PMID:16682563; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.49706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nielsen JS, Lei LK, Ebersbach T, Olsen AS, Klitgaard JK, Valentin-Hansen P, Kallipolitis BH. Defining a role for Hfq in Gram-positive bacteria: evidence for Hfq-dependent antisense regulation in Listeria monocytogenes. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:907-19; PMID:19942685; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkp1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nielsen JS, Larsen MH, Lillebæk EMS, Bergholz TM, Christiansen MHG, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M, Kallipolitis BH. A small RNA controls expression of the chitinase ChiA in Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS One 2011; 6:e19019; PMID:21533114; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0019019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chaudhuri S, Bruno JC, Alonzo F, Xayarath B, Cianciotto NP, Freitag NE. Contribution of chitinases to Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010; 76:7302-5; PMID:20817810; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/AEM.01338-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Burke TP, Portnoy DA. SpoVG is a conserved RNA-binding protein that regulates Listeria monocytogenes lysozyme resistance, virulence, and swarming motility. MBio 2016; 7:e00240-16; PMID:27048798; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/mBio.00240-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Quereda JJ, Ortega AD, Pucciarelli MG, García-del Portillo F. The listeria small RNA Rli27 regulates a cell wall protein inside eukaryotic cells by targeting a long 5'-UTR variant. PLoS Genet 2014; 10:e1004765; PMID:25356775; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Loh E, Dussurget O, Gripenland J, Vaitkevicius K, Tiensuu T, Mandin P, Repoila F, Buchrieser C, Cossart P, Johansson J. A trans-acting riboswitch controls expression of the virulence regulator PrfA in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell 2009; 139:770-9; PMID:19914169; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Horvath P, Barrangou R. CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea. Science 2010; 327:167-70; PMID:20056882; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1179555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sesto N, Touchon M, Andrade JM, Kondo J, Rocha EPC, Arraiano CM, Archambaud C, Westhof E, Romby P, Cossart P. A PNPase dependent CRISPR system in listeria. PLoS Genet 2014; 10:e1004065; PMID:24415952; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bruno JC, Freitag NE. Constitutive activation of PrfA tilts the balance of Listeria monocytogenes fitness towards life within the host versus environmental survival. PLoS One 2010; 5:e15138; PMID:21151923; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0015138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hain T, Ghai R, Billion A, Kuenne C, Steinweg C, Izar B, Mohamed W, Mraheil M, Domann E, Schaffrath S, et al.. Comparative genomics and transcriptomics of lineages I, II, and III strains of Listeria monocytogenes. BMC Genomics 2012; 13:144; PMID:22530965; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2164-13-144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Marbaniang CN, Vogel J. Emerging roles of RNA modifications in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol 2016; 30:50-7; PMID:26803287; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mib.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Abdullah Z, Schlee M, Roth S, Mraheil MA, Barchet W, Böttcher J, Hain T, Geiger S, Hayakawa Y, Fritz JH, et al.. RIG-I detects infection with live Listeria by sensing secreted bacterial nucleic acids. EMBO J 2012;. 31(21):4153-4164; PMID:23064150; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2012.274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hagmann CA, Herzner AM, Abdullah Z, Zillinger T, Jakobs C, Schuberth C, Coch C, Higgins PG, Wisplinghoff H, Barchet W, et al.. RIG-I detects triphosphorylated RNA of Listeria monocytogenes during infection in non-immune cells. PLoS One 2013; 8:e62872; PMID:23653683; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0062872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cossart P, Lebreton A. A trip in the “New Microbiology” with the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. FEBS Lett 2014; 588:2437-45; PMID:24911203; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]