Abstract

Purpose

This article describes the protocol for a randomized effectiveness trial of a method to link alcohol use disordered women who are in pretrial jail detention with post-release 12-step mutual help groups.

Background

Jails serve 15 times more people per year than do prisons and have very short stays, posing few opportunities for treatment or treatment planning. Alcohol use is associated with poor post-jail psychosocial and health outcomes including sexually transmitted diseases and HIV, especially for women. At least weekly 12-step self-help group attendance in the months after release from jail has been associated with improvements in alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences. Linkage strategies improve 12-step attendance and alcohol outcomes among outpatients, but have not previously been tested in criminal justice populations.

Design

In the intervention condition, a 12-step volunteer meets once individually with an incarcerated woman while she is in jail and arranges to be in contact after release to accompany her to 12-step meetings. The control condition provides schedules for local 12-step meetings. Outcomes include percent days abstinent from alcohol (primary), 12-step meeting involvement, and fewer unprotected sexual occasions (secondary) after release from jail. We hypothesize that (1) 12-step involvement will mediate the intervention’s effect on alcohol use, and (2) percent days abstinent will mediate the intervention’s effect on STI/HIV risk-taking outcomes. Research methods accommodate logistical and philosophical hurdles including rapid turnover of commitments and unpredictable release times at the jail, possible post-randomization ineligibility due to sentencing, 12-step principles such as Nonaffiliation, and use of volunteers as interventionists.

Keywords: Jail, Alcohol addiction, Women, 12-step, Volunteers

1. Introduction

More than 11 million admissions to U.S. jails occur each year; about 15% of these (~1.65 million) are women.1 Even relative to incarcerated men, incarcerated women are largely poor, uninsured, and face complex health, housing, and employment issues.2 They also have high rates of substance use problems (65–70%),3–5 including alcohol use disorders (AUD; 39%).6 Alcohol use is associated with poor post-release psychosocial, criminal, and health outcomes such as sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV.

Alcohol treatment is challenging in jail settings because of short jail stays. Unlike prison, where women have been sentenced and typically stay from months to years, women in jail are either pretrial (unsentenced) and may be released on bond or are serving short sentences. The weekly turnover rate in jails is 65%.7 In prisons, longer stays offer opportunities to receive alcohol treatment and post-release treatment planning. In contrast, because women may be in jail only a few days and release times are unpredictable, professional in-jail alcohol treatment or even post-release treatment planning is often not available or feasible.8,9 Therefore, women often face community re-entry with limited recovery supports.

Nearly two thirds of incarcerated women with AUD are willing to enter treatment.10 However, accessing treatment during transition to the community is challenging because of cost, lack of insurance, low availability, unfamiliarity with agencies/providers, time conflicts, and transportation difficulties.11 Our previous work suggests that requiring re-entering women to seek out strangers for alcohol recovery support is another important barrier.12–14

Twelve-step self-help groups are a free, widely available intervention. Many incarcerated women have attended 12-step groups at some point during their lives, but most do not currently attend regularly.15 Participation in 12-step groups is associated with improvements in alcohol-related consequences and patterns of drinking post-incarceration.15 Due to short jail stays, there are few long-standing 12-step self-help groups in jails.16 Even if 12-step meetings occur in jail, no routine opportunity is available for an incarcerated woman to meet one-to-one with a 12-step volunteer during incarceration or for her to connect with that same volunteer after release. As a result, as a woman returns to the community, she is expected to initiate contact with unfamiliar individuals to support her recovery.

Previous randomized trials in non-jail populations17–19 have found that providing a “warm handoff” in the form of phone or personal contact with 12-step members results in dramatically increased rates of meeting attendance18 and enhances likelihood of abstinence relative to the more typical strategy of offering meeting lists and reasons to attend 12-step groups.17,18 Our pilot work indicates that the same may be true for women leaving jail.13 The NIAAA-funded randomized effectiveness trial described below is the first to test a 12-step self-help group linkage (i.e., warm handoff) approach in a criminal justice population. Novel aspects of the trial design include planning research procedures to accommodate 12-step principles (e.g., Nonaffiliation and Attraction), rapid turnover and unpredictable jail release times, post-randomization ineligibility if a woman is sentenced, and community volunteers as interventionists. In-jail PEth testing20 is another novel feature of this study design.

2. Method

This randomized clinical trial (RCT) evaluates the effectiveness of a method to enhance the linkage between women with AUD who are leaving jail and 12-step self-help resources in the community. The intervention is independent of 12-step self-help groups, but, like many professional interventions, it seeks to promote 12-step participation. The intervention (Community Links to Establish Alcohol Recovery; CLEAR) consists of having a 12-step volunteer come into the jail to meet individually with the incarcerated woman. During this meeting, the volunteer develops rapport with the woman, discusses 12-step meetings and principles (typical of a 12-step call), and arranges to be in contact with the woman after her discharge to attend a meeting together. In the control condition, research staff provide women with a list of local 12-step meetings and community resources. The sample will include 320 unsentenced women who are in pretrial jail detention who meet criteria for AUD and who do not expect to be sentenced to serve jail or prison time. Alcohol use and HIV risk-taking are assessed at baseline (in jail) and at 1-, 3-, and 6-months after release from jail. Hypotheses are that:

Adding an intervention that provides 12-step linkage (CLEAR) will result in less alcohol use at follow-up relative to standard of care (SOC), as indexed by greater percent days abstinent (primary outcome).

CLEAR will increase 12-step self-help attendance/involvement and network support for abstinence relative to SOC (secondary outcomes).

Because incarcerated women report that addiction/intoxication is the primary reason they engage in unprotected sex, CLEAR, will result in less HIV/STI sex risk relative to SOC, as indexed by fewer unprotected sexual occasions at all follow-up assessments (secondary outcome).

12-step attendance/involvement will mediate the effect of CLEAR on alcohol use;

Percent days abstinent will mediate the effect of CLEAR on HIV/STI risk-taking outcomes.

The trial is funded by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). It is approved by Butler Hospital’s Institutional Review Board as well as regulatory bodies overseeing jail research in our participating jail. A 6-member external Data Safety and Monitoring Board (consisting of 3 external members, the two PIs, and the study statistician) has been assembled to evaluate data and safety of study participants. The trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 01970293).

2.1. Preliminary studies

The rationale for the current trial developed from our previous findings in studies of interventions for incarcerated women with substance use who were returning to the community. First, we found that among 224 women with alcohol problems, those who attended alcohol-focused 12-step self-help groups at a rate of weekly or greater (15–20%) in the 6 months after leaving jail experienced greater reductions in drinking consequences (B = −.45) and drinking days (B = −.28) than those who did not attend such groups or attended less than weekly.15

Next, we found that in our RCT samples, half the women leaving prison who relapsed to substances did so within the first 8 days, before many had been able to attend formal treatment.14,21,22 12-step self-help groups can help to address this challenge because they are free, available, do not require an appointment, and can be used intensively in the critical first few days after release.

A third set of studies12,14,21 suggested that face-to-face contact with incarcerated women has a powerful influence on the resources that they are willing to utilize after release. Incarcerated women expressed a strong preference to talk to prison/jail counselors with whom they were already familiar after release, rather than establish a new contact at time of release. A small open trial (n = 22) provided 24 sessions of in-prison treatment encouraging women to attend 12-step self-help meetings after release. It also provided post-release cell-phones preprogrammed with community resources, including the number of Bridging the Gap (BTG), a 12-step organization available in nearly every state that a woman could call to be assigned a female volunteer to take her to her first 12-step meeting after release. All participants contacted the study counselors with whom they were familiar, and 0 of the 22 women called the BTG hotline where they did not know anyone.12,13 When this finding was explored in qualitative work,12,14,21 women and providers consistently described women being willing to reach out to people perceived as familiar and trustworthy (“we will call you because we know you and trust you”), but described personal unfamiliarity and lack of trust as an important barrier to accessing post-release services.

To pilot a strategy to overcome this barrier, we conducted a small feasibility trial of CLEAR that recruited unsentenced women in jail who met criteria for AUD.13 We cooperated with a local BTG group to have its volunteers meet participants one-on-one in jail for 30–45 minutes. After release, the same volunteer reached out to accompany the participant to her first few 12-step meetings. Among women who met with BTG volunteers in jail, 8 of 11 were in contact with their BTG volunteer after release from jail an average of 4 times. Drinking days, drug using days, and drinking problems significantly (p < .05) decreased, and the number of 12-step self-help meetings attended increased (p = .051) from baseline to 1-month follow-up.13 Overall, pilot open trial results indicated that CLEAR was feasible and acceptable, and that women experienced significant improvements in drinking.13

2.2. Interventions

2.2.1. Working with Bridging the Gap (BTG)

The long history, availability, no-cost entry, and promise of confidentiality and anonymity of 12-step mutual help groups make them a highly accessible resource. Existing 12-step infrastructure already provides resources for incarcerated populations. In nearly every state, 12-step organizations have developed a subsidiary group of 12-step group members called Bridging the Gap (BTG). BTG serves incarcerated persons re-entering the community by accompanying them to 12-step meetings post-release. However, BTG has historically done little or no outreach into prisons/jails (for example, in local jails/prisons, one might find their business card if one knows who to ask) but rather requires a recently released inmate to call strangers at a 1–800 number to get connected with someone to accompany her to a meeting, limiting use of this valuable 12-step service.

With this information in mind, we cooperated with local and national 12-step leadership to develop a mutually satisfactory approach to enhancing linkage to local 12-step groups that is consistent with 12-step traditions and that addresses the under-utilization of 12-step resources by jailed women returning to the community. Any coordination with researchers or professional providers must exist within the framework of 12-step membership rules. Members must be true to the 12-step Traditions, limiting what can be asked as part of their involvement in a research study. For example, we had many discussions about the Traditions of Nonaffiliation (12-step groups “ought never endorse, finance, or lend the name of 12-step organizations to any related facility or outside enterprise, lest problems of money, property, and prestige divert us from our primary purpose”) and Attraction (“Our public relations policy is based on attraction rather than promotion; we need always maintain personal anonymity at the level of press, radio, and films”).23 We preserved the volunteer group’s Nonaffiliation by (1) having them recruit, train, and supervise their own volunteers (rather than having us do it), (2) agreeing to not in any way imply that we or our study were endorsed by BTG or local 12-step organizations, (3) and framing ourselves as the matchmakers/coordinators of standard 12-step calls to a difficult-to-reach group. The rationale to our local BTG organization was: “Women transitioning from jail to community need your message. Despite their desire to connect with 12-step resources, standard outreach procedures to the jail (i.e., business cards for the 800 number) do not seem to help them get to 12-step meetings. We can’t provide the message for you, but we can find women who want the message and connect you with them, so you can deliver it.” The main selling point for the BTG volunteers was that it provided them an opportunity to do a 12-step call with a woman transitioning out of jail that they would not otherwise have. That is what they want to do, and this coordination helps them expand their reach to more people who need it.

We preserve volunteers’ Anonymity and Nonaffiliation in that we do not collect research data from BTG volunteers (e.g., about what occurred in the meeting) or record the meetings for fidelity (as would occur in a typical psychotherapy trial). We addressed the concern about Attraction (which some interpret as a prohibition on active outreach) by emphasizing that we would enroll study participants who reported interest in meeting with BTG volunteers, and emphasizing our “matchmaker-only” role. To the volunteers, what they are doing is a 12-step call with someone else to arrange the logistics.

Our previous qualitative work had shown that many re-entering women prefer not to make the first call, and interpret being called by providers or BTG volunteers as proving that they care. Because of the tradition of Attraction, volunteers were initially hesitant about making the first call after release, but pragmatics (i.e., the high level of need and life chaos for recently released women) overcame this concern. Getting the message to re-entering women who needed it, especially given that they will have already met with the BTG volunteer and expressed interest in 12-step participation, was the primary overarching goal.

It is worth noting that there is a very wide range as to how the 12 traditions are interpreted and a wide diversity of practices and opinions among 12-step groups and 12-step members. Given that each BTG chapter is more or less self-governing, some chapters found this solution acceptable, but at least one BTG chapter in another state (that required unanimity of opinions among members to participate) declined participation in this project.

2.2.2. CLEAR Intervention

BTG Volunteer – Participant Meetings

The in-jail meeting begins with the research staff member, study participant, and female BTG volunteer briefly discussing study expectations and logistics together. This discussion includes: (1) the plan for study staff to contact the volunteer on the day of participant release, (2) the plan for the volunteer to make a reasonable attempt to reach the participant by phone during the days immediately following release, and (3) how the volunteer will be involved in attempting to increase the participant’s awareness of and interest in 12-step meetings in the community, and accompanying her to agreed-on meetings to introduce her to other 12-step members and help her feel comfortable. As a convenience, the research assistant also has 12-step self-help materials and meeting books on hand for the volunteer to discuss with or provide to the participant, if desired.

After this brief discussion, the research assistant excuses herself, and the plan is for the study participant and volunteer to talk informally together for 30–45 minutes, typical of an 12-step call. Discussions typically cover 12-step philosophies, what meetings are about and how they work, the volunteer’s recovery story, the participant’s recovery goals, benefits of 12-step self-help meetings and principles, the participant’s previous experiences with 12-step meetings, what kind of meetings the participant might like, and meetings they might be able to attend together.

As in our pilot study, research staff monitor jail releases each day in order to let each BTG volunteers know one of her participants has left jail. The volunteer then calls the study participant to set up a time to take her to her first 12-step meeting. The plan is for the volunteer to bring the participant to a meeting (or meets her at a meeting) that they have decided might be a good fit for her based on their conversation. In typical 12-step fashion, the volunteer introduces the participant to the meeting and to other 12-step members. The volunteer arranges to take the participant to a second meeting, if this is acceptable to the participant, and helps the participant get connected to others there. The second meeting may be the same or different.

The volunteer makes no commitment beyond these two escorts (for instance, she does not commit to being a 12-step “sponsor”), but if the participant and volunteer want to continue to attend meetings together it is encouraged, consistent with standard 12-step policies. In sum, the volunteer’s role is to get the woman into meetings, introduce her to other 12-step members, and help her feel comfortable, and we anticipate that the broader 12-step fellowship will build from there.

2.2.3. Salience of external validity

Although the study’s role in the linkage is scripted, the meetings between the participant and BTG volunteer cannot be scripted or manualized. Furthermore, BTG prohibits the audiotaping of the in-jail visit which would allow a more precise description of the interaction. Therefore, we characterize the intervention in other ways (see Section 2.10.3). The impact of this study comes from testing what is designed as a “real world” intervention. Indeed, allowing for these limitations is the only way that BTG and 12-step members agreed to serve this population of vulnerable women for the current proposal. The proposed approach has the advantages of being externally valid, flexible, and potentially exportable to other 12-step groups. Participant meetings with 12-step volunteers are characterized using data collected from participants.

2.2.4. SOC

Because external validity is a crucial concern in criminal justice settings, many, if not most, NIH-funded criminal justice R01s use Standard of Care (SOC) control conditions. Similarly, because our goal was to design a study relevant to jail practice and policy decisions, this study employs an SOC control condition. As is the case in many jails nationally8, standard care for women in pretrial jail detention at the study site does not include any alcohol intervention. In keeping with ethical obligations to this population, we enhance standard care for trial participants by providing treatment and resource brochures and 12-step meeting lists. In addition, we provide free treatment for trichomoniasis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea if enrollees test positive for any of these infections at research follow-ups in the community. Contamination of intervention conditions is unlikely to occur because BTG volunteers do not typically come into the recruitment jail site or have one-on-one meetings with incarcerated women outside of their cooperation with this study.

2.3. Participants

Women in the participating jail are eligible for the study if they are: (1) 18 years of age or older; (2) unsentenced and do not expect to be sentenced to prison or jail time, (3) live within 20 miles of our research offices and plan to remain in the area for the next 6 months, (4) meet DSM-5 criteria for AUD in the last six months, (5) do not expect to attend residential alcohol or drug treatment upon release (residential treatment has strong independent effects on abstinence and 12-step self-help group attendance, and often does not allow 12-step volunteers to visit women), and (6) speak English well enough to understand study measures when read aloud. Women are excluded if they cannot provide the name of at least two verifiable locator persons who will know where they can be found.

We plan to recruit 320 women from the women’s jail. Recruitment began in October 2013. Research staff have access to the jail facility only 4 hours per day (including weekends), with one or two private rooms available for interviewing. In addition, BTG volunteers on this project are available only 2–3 nights per week. After obtaining consent for the screening phase of the study, research staff conduct the screening to determine eligibility for the intervention study. For those who meet eligibility requirements, research staff carefully explain all aspects of the study individually and privately, including possible benefits and risks, the schedule of visits, and the expected duration of participation. Research staff then address any questions or concerns regarding the study. Potential participants are informed that: (1) a decision not to participate in the research will have no impact on their status or expected length of stay at the jail; (2) the study has a Certificate of Confidentiality; and (3) no information provided during the study will be shared with correctional staff, officers of the court, parole officers or others in the criminal justice system. We ask participants if they would like us to read the consent forms aloud.

2.4. BTG 12-step volunteers

Because of Nonaffiliation, BTG manages the recruitment, training, and supervision of all of its volunteers for any activity. It has committees that meet regularly, provide ongoing support to volunteers, and recruit and train additional volunteers as needed. Volunteers for this study are taken from the pool of female volunteers who are already vetted by the local BTG chapter to provide services to women leaving jail. This protects the integrity of 12-step procedures and increases the external validity of the study. Monthly, research staff ask volunteers for their available dates to travel to the jail to meet new study participants.

Our local 12-step organization’s expectations of jail and prison volunteers are that they: (1) have been sober for at least 2 years; (2) can be cleared for entry into the jail (i.e., no felonies, no outstanding warrants, not on the visiting list of any current inmate; have attended the 4-hour introductory meeting at the jail for new volunteers); (3) can get to the jail and to meetings (either in a car or convenient access to public transportation); and (4) are perceived as reliable and responsible, invested in 12-step service to incarcerated women, and who have availability to take women to meetings. As a result of needing a criminal background check clearance, volunteers are typically not formerly incarcerated.

2.5. Research site

Nationally, jails (unlike prisons) tend to serve metro areas or counties, covering areas similar in size to our participating jail. Nationally, as in our participating jail, the majority of people passing through jails each year are charged with misdemeanor offenses, such as public drunkenness, trespassing, shoplifting, and public disturbances8. Nationally, as in our participating jail, women in jail tend to be young (with most in their 20s and 30s) and to have lower SES than the general population.24,25 Rates of AUD (43%) and length of stay among women in jail (median length of stay of 4 days) at our participating jail are similar to reported national rates (39% with AUD6, 65% weekly turnover rate).7 Thus, our participating jail is similar to other jails in characteristics relevant to this intervention. The average female daily census for the jail is 65. Private rooms are available for research assessments and for the intervention.

2.6. Randomization

Randomization occurs immediately after the baseline assessment. Because turnover in the jail is so rapid, we designed the CLEAR intervention and other study procedures so that a participant’s entire in-jail study participation occurs within a single day. When we have a volunteer scheduled for the evening, research staff recruit in the morning. Consent and baseline take place early in the day, followed by randomization. For women assigned to the CLEAR condition, the in-jail intervention meeting takes place later in the day. For those assigned to SOC, research staff review the follow-up schedule and participant contacts immediately following randomization. Given the large anticipated sample size, we do not stratify randomization.

2.7. Post-randomization ineligibility

Our target population is unsentenced female pretrial detainees who are returning to the community. We exclude women who expect to be sentenced to serve jail or prison time. However, we expect 6–8% of the pretrial jail detainee participants we consent who do not expect to be sentenced will in fact be sentenced to serve prison or jail time without leaving detention. These individuals are no longer be considered eligible for follow-up (because they are not pretrial detainees being released to the community) and are included in our attrition estimates. This is a standard approach taken in other re-entry studies (e.g., U01 MH106660; U01 DA01619126) that must consent participants when their sentencing or release status is still unknown. Sentencing occurs independent of study condition, so their exclusion from analysis (no “at-risk” community months) is unlikely to influence internal validity. In addition, if an unsentenced enrollee is incarcerated for more than 2 months after the baseline interview (and CLEAR or SOC intervention) occurs, she is also considered post-randomization ineligible. We will follow all remaining participants who are released from jail to the community after the index incarceration through the 6-month post-release period regardless of re-incarceration or continued participation in CLEAR or SOC.

2.8. Retention

We employ several approaches that we have found helpful in achieving good follow-up rates in the PIs’ other intervention studies with incarcerated women at the recruitment site.24,27–29 These include study staff’s strong relationships with participants and efforts to value and appreciate the women’s study participation. Research assistants call women to remind them of their appointments and maintain a list of 2 other people who will always know where the woman resides. Contact with a significant other serves as a valuable tool for maintaining participant involvement, and updating contact information. We check in by phone with participants within a week of their release (and collect a few brief assessments), and then participants receive multiple phone reminders on the days leading up to interviews. Follow-up interviews occur at safe locations convenient for participants, including safe community locations, our research offices, or at the jail if the participant is re-incarcerated. We are also able to offer a phone interview option for participants who cannot be interviewed any other way. Cab service to interviews also facilitate participant retention. Participants are remunerated $60 for their 1-, 3-, and 6-month assessments.

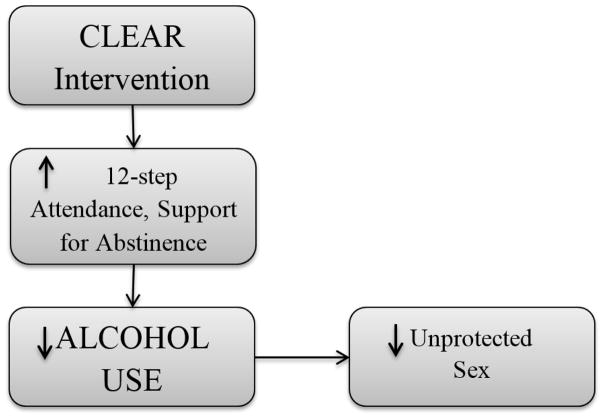

2.9. Rationale for choice of secondary outcomes and mediators (see Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of intervention effects

Network support for abstinence is a secondary outcome, and 12-step self-help attendance/involvement is a hypothesized mediator of the effects of the linkage intervention on alcohol use. 12-step participation also offers opportunities to extend sobriety support networks,30,31 which are related to post-release substance use treatment engagement60, 61 and to preventing substance use relapse and re-incarceration,32–35 especially for women.36 12-step self-help organizations naturally provide an enhanced sober support network through meeting attendance and general 12-step involvement where women receive emotional support, sober support, and information about accessing tangible supports.

Addressing alcohol problems among jailed women may help to diminish risky sexual behavior. Because incarcerated women report that addiction/intoxication is the primary reason they engage in unprotected sex,37 HIV/STI sex risk (as indexed by unprotected sexual occasions) is another secondary outcome. We hypothesize that percent days abstinent will mediate the effect of CLEAR on HIV/STI risk-taking outcomes. We chose to focus on HIV/STI risk as an important potential consequence of alcohol use in this study because of its public health significance and prevalence among our target population (about 50% of incarcerated women self-report STI history38,39). We focus on sex risk for HIV/STI because 90% of HIV transmission among women of childbearing age in the United States has been attributed to heterosexual contact,40 and because the large majority of our target population do not inject drugs.24

2.10. Assessments

Assessments take place at baseline, and at 1-, 3-, and 6-months after jail release (see Table 1). We follow guidelines for getting accurate self-report of substance use41 by assuring confidentiality (we obtained an NIAAA Certificate of Confidentiality), breath testing at interviews, and assuring participants that information they provide, regardless of outcome, is important, minimizing participants’ fear of disappointing the researchers.

Table 1.

Schedule of assessments

| Measure | Post-release: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1-mo | 3-mo | 6-mo | |

|

| ||||

| SCID-5 substance use disorders | X | |||

| TLFB: alcohol, drugs, sex, 12-step meetings | X | X | X | X |

| 12-step Affiliation Scale | X | X | X | X |

| Important People and Activities (IPA) | X | X | X | X |

| Short Inventory of Problems (SIP) | X | X | X | |

| PEth/STI testing | X | X | X | X |

| Breathalyzer/urine tox screens | X | X | X | |

| Treatment Services Review (TSR) | X | X | X | X |

| End of Treatment Questionnaire (ETQ) | X | |||

| Topics discussed checklist | X | |||

| Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-12) | X | X | ||

| Readiness to Change Behavior Ladder | X | |||

| Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS) | X | |||

| Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) | X | |||

2.10.1. Screening

The alcohol use disorder module from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5)42 is used to determine diagnostic eligibility for current AUD.

2.10.2. Outcomes (see Table 1)

Alcohol use (primary outcome) is measured with the Timeline Followback (TLFB). The TLFB interview43 is used to assess days abstinent and drinks per drinking day during each follow-up period. The TLFB is also used to assess secondary outcomes including number of 12-step self-help meetings attended with and without one’s volunteer, as well as sex risk behaviors including number of vaginal and anal sex occasions and unprotected vaginal and anal sexual occasions (USOs) for each of the participant’s sexual partners. Although alcohol use is our primary outcome, we also collect tertiary outcomes including drug using days, as well as arrests and re-incarcerations over the follow-up period, using the TLFB. 12-step involvement pre-incarceration, during incarceration, and during follow-up is measured with the 12-step Affiliation Scale.44 This 9-item scale assesses a range of 12-step experiences, including having a sponsor, reading 12-step literature, working the steps, and self-identification as a 12-step member. Network support for abstinence (sober support) is measured using the revised Behavioral Support for Abstinence scale45 of the Important People and Activities (IPA)45–47 scale. We also assess alcohol-related problems using the Short Inventory of Problems (SIP48). STI/HIV Sexual Risk Behavior. We measure self-reported sexual behavior and biologically confirm common STIs (see next paragraph). We use sex risk behaviors and other STIs as surrogates for HIV risk to improve study power, given that HIV has a far lower incidence rate than sex risk behavior or STIs.

Study assessments also include biological verification. A breathalyzer and urine toxicology are performed at assessments outside the jail (1, 3, 6 months if not re-incarcerated) by the RA. Participants found to be alcohol-positive (BAL >.02) are re-scheduled or delayed until the person is alcohol-negative. We are also conducting biological testing with PEth20 (which reflects alcohol use over the last few weeks) at all visits, including visits in the jail. We are not aware of previous studies that have conducted PEth testing (which involves a finger stick) inside the jail and then outside during re-entry, making this an additional novel aspect of the study. STI Testing occurs at all interviews and includes: (1) vaginal trichomoniasis; (2) cervical infection with C trachomatis; (3) cervical infection with N gonorrhoeae. C trachomatis, and trichomonas are diagnosed based on positive ligase chain reaction testing. Incarcerated participants are treated (if needed) by correctional staff. For women found to be positive for any of these infections at community-based assessments, research staff re-contact them to offer single-dose curative antibiotic treatment provided by study investigators or to make referrals to participants’ primary care or gynecological providers.

2.10.3. Intervention characterization and process measures

Our local 12-step organizations (including BTG) will not permit audiotaping of the in-jail interview nor surveys directed at volunteers. Instead, to characterize these interviews, we time the meetings and ask participants immediately after the meeting to estimate whether the following were discussed: the sharing of recovery stories, advantages of meetings, what meetings the participant might like, and practical arrangements for meeting post-release, and any other topics discussed. We ask participants to estimate the ratio of time the volunteer spends talking to the amount of time the participant spent talking, and to rate their working alliance using the 12-item Working Alliance Inventory (WAI).49 We will determine whether or not these in-session variables predict the number of: (1) times the volunteer and woman meet after release, (2) meetings attended by the woman, or (3) drinking days.

We also assess barriers and incentives for 12-step meeting attendance and participants’ reactions to the referral process. Volunteers’ ability to foster trust and comfort among women in jail is important. The adapted End of Treatment Questionnaire (ETQ)50 assesses the perceived helpfulness of intervention components, barriers and facilitators of trust, comfort, and desire to continue to see the volunteer and go to 12-step meetings among CLEAR condition participants. Finally, the Treatment Services Review (TSR51) is used to assess receipt of alcohol, drug, mental health, and medical treatment.

2.10.4. Individualized intervention response

We will explore variables potentially relevant to personalization of intervention response by exploring whether the following predict study outcomes as main effects or act as moderators of intervention effects. Predictors to examine include baseline levels of outcome variables (alcohol use, USOs, 12-step attendance, 12-step involvement), opiate or cocaine use disorder, and readiness to change as assessed by the Readiness to Change Behavior Ladder.52 Additional predictors from the Twelve-Step Facilitation literature53,54 are also assessed and explored, including prior 12-step experience (assessed by questions about number of meetings attended in lifetime and number of substance use treatment episodes),53 poor resources (a composite index of unemployment, education, and income), psychiatric severity (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms,55 Davidson Trauma Scale56), AUD severity (as indexed by number of SCID-5 criteria met), and age.

2.11. Data Analysis

Primary analyses will be intent-to-treat. A 2-sided α = .05 will be used for tests of Hypotheses 1–5, specified a priori. Additional tests (e.g., of moderation) and outcomes (e.g., drug use, days incarcerated) will be considered to be exploratory and/or will correct for multiple comparisons. Descriptive statistics will include effect sizes, 95% confidence interval estimates, and measures of clinical significance (e.g., number needed to treat; NNT). We will separate our primary outcome (i.e., effect of CLEAR on alcohol use) from the remaining outcomes.

2.11.1. Missing Data

Prior to examining outcomes, we will explore whether baseline characteristics (e.g. sociodemographics, cocaine use) predict patterns of missingness. Any significant (p<.10) predictors of missingness will be included as covariates in multiple imputation procedures (MICE)57 and model fitting to explore the shape of individual changes over time.58 We will also compare intervention conditions on rates of missingness and time to missingness. Maximum likelihood estimation of individual growth curve models with Mplus will be used to take advantage of using all available data, with continuous, categorical, or count outcomes and provides implementation of modeling using multiply imputed data sets.

2.11.2. Primary Outcome

Participants randomized to the intervention will have higher percent days abstinent from alcohol than controls (Hypothesis 1). In our previous studies,24 graphical analysis and examination of model residuals indicated that 30-day rates of alcohol use during follow-up were well-approximated by the negative binomial distribution, though an excess number of high frequency, daily or near daily users, was observed. Therefore, we propose using negative-binomial (NB) regression to estimate the effect of intervention on the rate of alcohol abstinence days (number of abstinent days/30 non-incarcerated days). However, alternative models for count data (e.g., Poisson, zero-inflated Poisson, zero-inflated negative-binomial) may be more appropriate. Our final choice of analytical model will be based on graphical analysis comparing observed distributions with possible exponential family error distributions and an examination of model residuals. Tests of significance and CI estimates will be based on the robust variance estimators.

2.11.3. Secondary Outcomes

We hypothesize that CLEAR will increase 12-step self-help attendance/involvement and network support for abstinence relative to SOC (Hypothesis 2). Number of meetings attended (a count variable assessed using the TLFB) will be analyzed using the same procedures as Hypothesis 1. Continuous variables (12-step involvement [i.e., the 12-step Affiliation Scale score] and IPA network support for abstinence scores) will be analyzed using parallel models for continuous outcomes, with transformation as needed. We hypothesize that CLEAR, relative to SOC, will result in less HIV/STI sex risk, as indexed by fewer unprotected sexual occasions (USOs) at all follow-up assessments (Hypothesis 3). Number of USOs (a count variable) will be analyzed using the procedures for analyzing count outcomes described for Hypothesis 1. We anticipate operationalizing these outcomes as TLFB-assessed USOs/30 days. Exploratory effects of CLEAR on STI incidence will be conducted using generalized estimating equations to predict y/n STI status at each follow-up time point; baseline STI history will be a covariate. We will also explore the effects of CLEAR on TLFB-assessed drug using days, number of re-arrests, and y/n re-incarceration over the follow-up period.

2.11.4. Mediation Hypotheses

Hypotheses 4 and 5: We hypothesize that frequency of attendance at 12-step meetings (as assessed by the TLFB) and 12-step involvement (as assessed by the 12-step Affiliation Scale) will mediate the effect of intervention on rates of alcohol abstinence. We further hypothesize that rates of alcohol abstinence will mediate the effect of intervention on frequency of USOs. These mediation hypotheses will be tested in a structural equation model (SEM) framework using Mplus. Mplus can decompose total effects into direct and specific indirect effects. As recommended by MacKinnon et al59. the statistical significance of the indirect effect will be assessed using bias-corrected bootstrapped standard errors; 95% CI estimates for the specific indirect effect of intervention on rates of alcohol abstinence via rate of 12-step meeting attendance (and the specific indirect effect of intervention on frequency of USO via rate of alcohol abstinence) that do not include zero will provide support for the mediation hypotheses. We will also explore the effects of drug use and number of drinks on USOs.

2.11.5. Predictors/Processes

We will explore whether predictors listed in Section 2.10.4 act as main effects on outcomes (after controlling for the intervention) or as moderators of the intervention on outcomes with p < .01 to control for Type I error. We will explore whether in-session or between-session processes predict number of: (1) times the volunteer and woman meet after release, (2) 12-step self-help meetings attended, or (3) drinking days.

2.11.6. Statistical Power

Primary analyses will be intent-to treat. We express effect sizes as the percentage difference in the expected count outcomes after adjusting for the baseline measure of the corresponding outcome (e.g., days abstinent from alcohol; see description of negative binomial analyses above in Sections 2.11.2, 2.11.3, and 2.11.4). Using parameter estimates derived from a previous study,24 robust (MLR) variance estimators, and 5,000 replications, we estimated statistical power for negative binomial regression models by simulation. All models included the baseline rate of alcohol use as a planned covariate. Based on recruiting 160 subjects/intervention arm and specifying 20% attrition and α = .05, the estimated statistical power was .99, .97, and .84 for effect sizes corresponding to 30%, 25%, and 20% lower rates of alcohol use (operationalized as using days per 30 non-incarcerated days) in the intervention arm. Previous 12-step linkage studies among non-incarcerated populations, as well as our trials of other brief interventions for incarcerated women, have had effect sizes at least this large.60,24,61,62 In our pilot work, 15 of 17 correctional substance use treatment providers said that they would change their practice behavior if an intervention reduced likelihood of substance use by even 10%. Thus, our targeted 20% drinking rate reduction represents a clinically significant difference that is likely to have treatment and policy implications.

Following Fritz and MacKinnon’s63 simulation studies estimating sample size requirements for detecting mediated effects under varying conditions, a sample of 148 is required to have a power of .8 to detect mediation if both coefficients defining the indirect were between small and medium. Based on their analysis we believe the proposed study has sufficient power to detect meaningful mediation processes.63–65

3. Summary and Discussion

Transition back into the community after discharge from jails represents a high-risk period for resurgence of alcohol use and concomitant life problems, such as unprotected sex while intoxicated. Our approach, if supported, will bypass many of the cost and availability obstacles that impede the widespread adoption of evidence-based interventions in the criminal justice system to improve the outcomes of jailed women and benefit society at large. Because 12-step meetings are free and volunteers are widely available, enhancing their use by incarcerated women returning to the community is a disseminable and low-cost method to improve alcohol and other related (e.g., sexual risk) outcomes in this vulnerable population with limited resources. If the CLEAR intervention is successful, results will have important implications for addressing the needs of incarcerated women with AUD and lay the groundwork for future studies of implementation or expansion to other criminal justice populations.

This trial is novel in several ways. It addresses the compelling unmet need for effective interventions for jailed women with AUD at community re-entry. This is an underserved population at high risk for alcohol relapse, STI/HIV, and other health consequences. The trial also targets the under-studied but vast jailed population, where high and extremely rapid turnover rates, few financial resources, and difficulty implementing services that require trained correctional system personnel complicate intervention delivery. Finally, the trial is the first to test an intervention that provides 12-step linkage in a criminal justice population, potentially mitigating a critical barrier to post-release 12-step self-help meeting attendance. Research methods were designed to accommodate: (1) 12-step principles such as Non-affiliation, Attraction, and Anonymity, (2) use of 12-step community volunteers as interventionists, (3) rapid turnover of commitments and unpredictable release times at the jail, and (4) need to randomize and intervene before fully determining eligibility (i.e., sentencing may occur unexpectedly after in-jail randomization and intervention). Creating a feasible protocol to accommodate these logistical and philosophical constraints is innovative. The use of PEth testing to inside the jail and then outside during re-entry to confirm recent alcohol use is an additional novel aspect of the study.

Results from this registered randomized trial will be published following the CONSORT guidelines. We will also contribute to the scientific literature through publication of papers evaluating our mediational hypotheses, predictor papers, process papers, temporal ordering papers (for example, examining the temporal association of days with 12-step meeting attendance, alcohol use days, days with unprotected sex), and other secondary analyses to better understand the behaviors of jailed alcohol-abusing women returning to the community. This trial and associated manuscripts will extend findings relating 12-step linkage interventions to a new population with a pressing need.

Acknowledgments

Funding. All authors’ participation in this research was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; R01 AA021732; PIs Stein and Johnson). NIAAA did not participate in the design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Competing interests. The authors have no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Minton T, Zeng Z. Jail inmates at midyear 2014. Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Brien P. Making it a Free World: Women in Transition from Prison. New York: State University of New York Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan BK, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Caddell JM. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women. II. Convicted felons entering prison. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(6):513–519. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830060057008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis C. Treating incarcerated women: Gender matters. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29(3):773–789. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women. I. Pretrial jail detainees. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(6):505–512. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830060047007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karberg J, James D. Substance dependence, abuse, and treatment of jail inmates, 2002. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice; 2005. Report No. NCJ 209588. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minton TD. Bureau of Justice Statistics, editor. Jail inmates at midyear 2010 - Statistical tables. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon AL, Osborne JWL, LoBuglio SF, Mellow J, Mukamal DA. Life after lockup: Improving reentry from jail to the community. Washington, DC: Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 44. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005. Substance abuse treatment for adults in the criminal justice system. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 05–4056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullings JL, Hartley DJ, Marquart JW. Exploring the relationship between alcohol use, childhood maltreatment, and treatment needs among female prisoners. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39(2):277–305. doi: 10.1081/ja-120028491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatton DC, Kleffer D, Fisher AA. Prisoners' perspectives of health problems and healthcare in a US women's jail. Women & Health. 2006;44(1):119–136. doi: 10.1300/J013v44n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JE, Williams C, Zlotnick C. Development and feasibility of a cell phone-based transitional intervention for women prisoners with comorbid substance use and depression. The Prison Journal. 2015;95(3):330–352. doi: 10.1177/0032885515587466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson JE, Schonbrun YC, Stein MD. Pilot test of twelve-step linkage for alcohol abusing women leaving jail. Substance Abuse. 2013 doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.794760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson J, Schonbrun YC, Peabody ME, Shefner RT, Fernandes KM, Rosen RK, Zlotnick C. Provider experiences with prison care and aftercare for women with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorder: Treatment, resource, and systems integration challenges. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2014 Mar 25;:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9397-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schonbrun YC, Strong DR, Anderson BJ, Caviness CM, Brown RA, Stein MD. Alcoholics Anonymous and hazardously drinking women returning to the community after incarceration: Predictors of attendance and outcome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(3):532–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01370.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alcoholics Anonymous. A.A. in correctional facilities. New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Hirsch LS. Maintaining change after conjoint behavioral alcohol treatment for men: outcomes at 6 months. Addiction. 1999;94(9):1381–1396. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.949138110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timko C, DeBenedetti A. A randomized controlled trial of intensive referral to 12-step self-help groups: one-year outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(2–3):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timko C, Debenedetti A, Billow R. Intensive referral to 12-Step self-help groups and 6-month substance use disorder outcomes. Addiction. 2006;101(5):678–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piano MR, Tiwari S, Nevoral L, Phillips SA. Phosphatidylethanol levels are elevated and correlate strongly with AUDIT scores in young adult binge drinkers. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2015;50(5):519–525. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson JE, Schonbrun YC, Nargiso JE, Kuo CC, Shefner RT, Williams CA, Zlotnick C. “I know if I drink I won’t feel anything”: Substance use relapse among depressed women leaving prison. International Journal of Prisoner Health. 2013;9(4):1–18. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-02-2013-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke J, Anderson BJ, Stein MD. Hazardously-drinking women leaving jail: Time to first drink. J Correct Health Care. 2011;17(1):61–68. doi: 10.1177/1078345810385915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anonymous A. This is A.A.: An introduction to the A.A. Recovery Program. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services Inc; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein M, Caviness C, Anderson B, Hebert M, Clarke J. A brief alcohol intervention for hazardously-drinking incarcerated women. Addiction. 2010;105(3):466–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snyder HN, Mulako-Wangota J. Generated using the Arrest Data Analysis Tool. Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2012. Arrests of females by age in the United States, 2009. at www.bjs.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedmann P, Katz E, Rhodes A, Taxman FS, O'Connell DJ, Frisman LK, Burdon WM, Fletcher BW, Litt MD, Clarke J, Martin SS. Collaborative behavioral management for drug-involved parolees: Rationale and design of the Step'n Out study. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2008;47(3):290–318. doi: 10.1080/10509670802134184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zlotnick C, Johnson J, Najavits LM. Randomized controlled pilot study of cognitive-behavioral therapy in a sample of incarcerated women with substance use disorder and PTSD. Behav Ther. 2009;40(4):325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson J, Zlotnick C. Pilot study of treatment for major depression among women prisoners with substance use disorder. J Psychiatric Res. 2012;46:1174–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson JE, Zlotnick C. A pilot study of group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in substance-abusing female prisoners. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(4):371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bond J, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. The persistent influence of social networks and Alcoholics Anonymous on abstinence. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(4):579–588. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Humphreys K, Mankowski ES, Moos RH, Finney JW. Do enhanced friendship networks and active coping mediate the effect of self-help groups on substance abuse? Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(1):54–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02895034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsons M, Warner-Robbins C. Factors that support women's successful transition to the community following jail/prison. Health Care Women Int. 2002;23:6–18. doi: 10.1080/073993302753428393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benda B. Gender differences in life-course theory of recidivism: A survival analysis. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2005;49(3):325–342. doi: 10.1177/0306624X04271194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liau AK, Shively R, Horn M, Laudau J, Barriga A, Gibbs JC. Effects of psychoeducation for offenders in a community correctional facility. Journal Community Psychology. 2004;32:543–558. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skeem J, Louden JE, Manchak S, Haddad E, Vidal S. Social networks and social control of probationers with co-occurring mental and substance abuse problems. Law Hum Behav. 2009;33(2):122–135. doi: 10.1007/s10979-008-9140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simpson DD, Knight K, Dansereau DF. Addiction treatment strategies for offenders. Journal of Community Corrections. 2004;13(4):7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staton-Tindall M, Leukefeld C, Palmer J, Oser C, Kaplan A, Krietemeyer J, Saum C, Surrat HL. Relationships and HIV risk among incarcerated women. The Prison Journal. 2007;87(1):143–165. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke JG, Hebert MR, Rosengard C, Rose JS, DaSilva KM, Stein MD. Reproductive health care and family planning needs among incarcerated women. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):834–839. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hale GJ, Oswalt KL, Cropsey KL, Villalobos GC, Ivey SE, Matthews CA. The contraceptive needs of incarcerated women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18(8):1221–1226. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. HIV Infection in Women. 2006 Downloaded 2/19/08 from the NIAID website http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/hivaids/understanding/population%20specific%20information/pages/womenhiv.aspx.

- 41.Babor TF, Stephens RS, Marlatt GA. Verbal report methods in clinical research on alcoholism: response bias and its minimization. J Stud Alcohol. 1987;48(5):410–424. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.First M, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Klajner F, Pavan D, Basian E. The reliability of a timeline method for assessing normal drinker college students' recent drinking history: utility for alcohol research. Addict Behav. 1986;11(2):149–161. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Humphreys K, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. The Alcoholics Anonymous Affiliation Scale: development, reliability, and norms for diverse treated and untreated populations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(5):974–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zywiak WH, Rohsenow D, Martin RA, Eaton CA, Neighbors C. Internal consistency, concurrent, and predictive validity of the drug and alcohol version of the IPA. Paper presented at: the 66th Annual Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence; San Juan, Puerto Rico. June, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zywiak WH, Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW. Decomposing the relationships between pretreatment social network characteristics and alcohol treatment outcome. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(1):114–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Litt MD, Kadden RM, Kabela-Cormier E, Petry NM. Changing network support for drinking: network support project 2-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(2):229–242. doi: 10.1037/a0015252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller W, Tonigan J, Longabaugh R. Project MATCH Monograph Series. Vol. 4. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism; 1995. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences: an instrument for assessing adverse consequence of alcohol abuse. DHHS Publication No. 95–3911. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tracey TJ, Kokotovic AM. Factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychol Assess. 1989;1:207–210. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Najavits LM, Gastfriend DR, Barber JP, et al. Cocaine dependence with and without PTSD among subjects in the National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(2):214–219. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Cacciola J, Metzger D, O'Brien CP. A new measure of substance abuse treatment. Initial studies of the treatment services review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180(2):101–110. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hogue A, Dauber S, Morgenstern J. Validation of a contemplation ladder in an adult substance use disorder sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24(1):137–144. doi: 10.1037/a0017895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timko C, Billow R, DeBenedetti A. Determinants of 12-step group affiliation and moderators of the affiliation-abstinence relationship. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83(2):111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaskutas LA, Subbaraman M. Integrating Addiction Treatment and Mutual Aid Recovery Resources. In: Kelly JF, White WL, editors. Addiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research, and Practice. Humana Press; 2011. pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, Comdy TJ, Biggs MM, Suppes T, Cirmon ML, Shores-Wilson K, Toprac MG, Denney EB, Witte B, Kashner TM. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med. 2004;34(1):73–82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, Hertzberg M, Mellman T, Beckham JC, Smith RD, DAvison RM, Katz R, FEldman ME. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 1997;27(1):153–160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Buuren S, Oudshoorn K. Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations: MICE V1.0 User’s manual. Report No. PG/VGZ/00.038. Leiden, The Netherlands: TNO Prevention and Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Graham JW. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stein MD, Caviness CM, Anderson BJ, Hebert M, Clarke JG. A brief alcohol intervention for hazardously drinking incarcerated women. Addiction. 2010;105:466–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Timko C, DeBenedetti A. A randomized controlled trial of intensive referral to 12-step self-help groups: One-year outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walitzer KS, Dermen KH, Barrick C. Facilitating involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous during out-patient treatment: A randomized clinical trial. Addiction. 2009;104:391–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fritz MS, Mackinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muthen L, Muthen B. Version 6 MPlus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2010. [Google Scholar]