Abstract

Differentiation of secondary metabolite profiles in closely related plant species provide clues for unravelling biosynthetic pathways and regulatory circuits, an area that is still under-investigated. Cucurbitacins, a group of bitter and highly oxygenated tetracyclic triterpenes, are mainly produced by the plant family Cucurbitaceae. These compounds have similar structures, but differ in their anti-tumor activities and eco-physiological roles. By comparative analyses of the genomes of cucumber, melon, and watermelon, we uncovered conserved syntenic loci encoding metabolic genes for distinct cucurbitacins. Characterization of the cytochrome P450s (CYPs) identified from these loci enabled us to unveil a novel multi-oxidation CYP for the tailoring of the cucurbitacin core skeleton as well as two other CYPs responsible for the key structural variations among cucurbitacins C, B and E. We also discovered a syntenic gene cluster of transcription factors that regulate the tissue-specific biosynthesis of cucurbitacins and that may confer the loss of bitterness phenotypes associated with convergent domestication of wild cucurbits. This study illustrates the potential to exploit comparative genomics to identify enzymes and transcription factors that control the biosynthesis of structurally related yet unique natural products.

Introduction

The structural diversity of plant secondary metabolites in phylogenetically related species is likely to be associated with adaptation to different ecological niches1. In the plant family Cucurbitaceae, bitter compounds known as cucurbitacins can serve as protectants against generalists, and also as feeding attractants for specialists2,3, in mediating the co-evolutionary association between herbivores and cucurbits including cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.), melon (Cucumis melo L.), and watermelon (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. et Nakai)3. To date, twelve categories of cucurbitacins have been discovered, most of these from cucurbit plants4. Although a cucurbitacin C (CuC) biosynthetic module consisting of nine genes has been identified in cucumber and four of the pathway enzymes have been characterized5, the genetic basis of cucurbitacin diversity among the wider cucurbits is unknown. Cucurbitacins also exhibit wide-ranging pharmacological potential, including anti-inflammatory, purgative and anti-tumor activities4,6,7. It is of particular interest that cucurbitacins B (CuB) and E (CuE) (Fig. 1a), the major bitter compounds isolated from melon8 and watermelon9 respectively, display much stronger anti-tumor activities than the structurally similar CuC9–11. Understanding the evolutionary and genetic basis of this metabolic diversity and specificity could provide crucial clues for chemical ecology and tools for crop breeding, as well as opening up opportunities for production and engineering of these plant-derived chemicals for pharmaceutical applications.

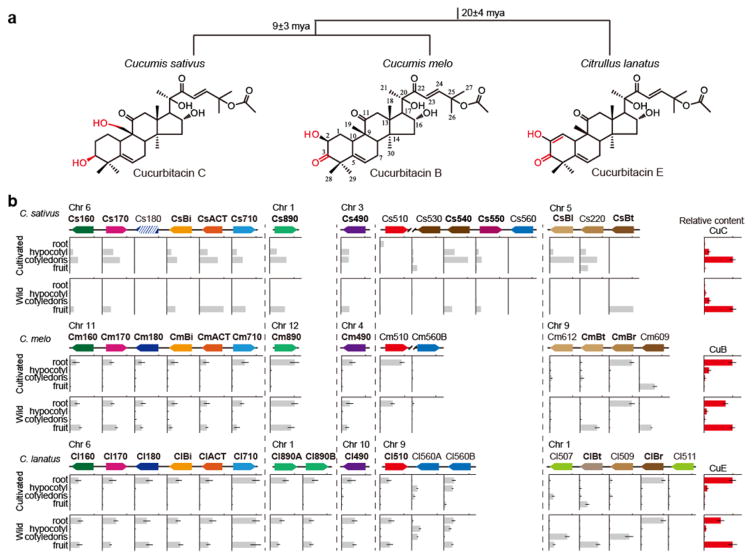

Figure 1. Comparative analysis of cucurbitacin biosynthetic and regulatory genes in cucumber, melon and watermelon.

(a) Evolutionary relationship of three cucurbits and structures of CuC, CuB and CuE. mya, million years ago. (b) Distribution of bitter compound and expression profiles of genes in wild or cultivated lines. Genes were renamed according to Table 1. For cucumber, gene expressions were shown by the FPKM value; for melon and watermelon, expressions profiles were determined by qRT-PCR. Relative gene expression values are shown with identical scales (means ± SEM, n=3 biological replicates). The potential biosynthetic enzymes and regulators of CuC, CuB or CuE are indicated in bold.

The non-bitter cucurbit cultivars that are used for production of vegetables and fruits for human consumption have been domesticated from their extremely bitter progenitors. In cucumber, expression of the CuC biosynthetic genes is controlled by two tissue specific basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors (TFs) in the leaves (Bl, bitter leaf) and fruit (Bt, bitter fruit)5. Mutations within the promoter of Bt effectively remove fruit bitterness, and this trait of non-bitterness has been selected and fixed during the domestication process5. However, it is unclear whether the mechanisms underlying CuC regulation and domestication in cucumber also prevail in other cucurbits. Since genome mining has become a powerful strategy for metabolic studies in both microbes and plants12–20, we envisioned that investigation of the genome sequences of three cucurbit plants (cucumber21, melon22, and watermelon23) would provide a unique opportunity to understand the regulatory and biochemical principles dictating cucurbitacin diversity in cucurbits.

Here, by applying a comparative genomic study, we report that independent mutations within syntenic transcription factor genes in the three cucurbits may result in marked decreases in fruit bitterness, in turn giving rise to converged domestication of bitter wild cucurbits. Furthermore, dynamic genomic variations in the biosynthetic loci explain the observed chemical diversity of cucurbitacins, opening up the possibility to produce novel cucurbitacins or derivatives thereof via metabolic engineering.

Results

Comparative analyses of cucurbitacin biosynthetic genes

Since CuC, CuB and CuE share very similar structures (Fig. 1a), their biosynthetic processes in the different cucurbits should be comparable to each other. According to the previous study5, nine CuC biosynthetic enzymes, including an oxidosqualene cyclase (OSC, the Mendelian gene Bi), seven cytochromes P450 (CYPs) and an acyltransferase (ACT), are co-expressed in the leaves of cultivated cucumber and the fruit of the wild ancestor, five of which are clustered (Bi, three CYPs, and an ACT) on chromosome 6 (Bi cluster). A comparative genomics approach was pursued to unravel the biosynthetic pathways of CuB and CuE in melon and watermelon, respectively. We analyzed the gene annotations within the collinear regions as well as the sequence similarities amongst the three cucurbits, focusing first on the region where the Bi cluster is localized (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Consistent with our expectations, similar gene clusters were identified in melon and watermelon on chromosomes 11 and 6, respectively. The gene annotations and orientations within these two regions are exactly the same as those of Bi cluster (Supplementary Fig. 1a). To simplify the narrative, we renamed all the genes annotated within these syntenic regions (Table 1). Similar syntenic genes were also observed at the collinear region of Cs490 and Cs890 except for the presence of two paralogous genes (Cl890A and Cl890B) in the watermelon genome (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). In contrast, less similarity was observed at the collinear region where Cs540 and Cs550 are located: the full-length orthologous genes were truncated in melon and missing in watermelon (Supplementary Fig. 1d, f).

Table 1. Abbreviation and functional summary of the cucurbitacin biosynthetic and regulatory genes in three cucurbits.

Orthologous genes are listed in row and indicated with the same background. The co-expressed genes encoding potential CuC, CuB or CuE biosynthetic enzymes or regulators are indicated in bold. C2, C11, C20, C19, and C25 represent the corresponding carbon atom of cucurbitadienol. The evolutionary relationship of the genes encoding CYP88s or bHLH TFs is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

| Gene type | Cucumis sativus | Cucumis melo | Citrullus lanatus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene ID | Abbr. | Remark | Gene ID | Abbr. | Remark | Gene ID | Abbr. | Remark | |

| Biosynthetic genes | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| CYP81Q58 | Csa6G088160 | Cs160 | C25 hydroxylase | Melo3C022377 | Cm160 | Cla007077 | Cl160 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| CYP89A140 | Csa6G088170 | Cs170 | Melo3C022376 | Cm170 | Cla007078 | Cl170 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| CYP81Q59 | Csa6G088180 | Cs180 | Melo3C022375 | Cm180 | C2 hydroxylase | Cla007079 | Cl180 | C2 hydroxylase | |

|

| |||||||||

| OSC | Csa6G088690 | CsBi | cucurbitadienol synthase | Melo3C022374 | CmBi | cucurbitadienol synthase | Cla007080 | ClBi | cucurbitadienol synthase |

|

| |||||||||

| ACT | Csa6G088700 | CsACT | acetyltransferase | Melo3C022373 | CmACT | acetyltransferase | Cla007081 | ClACT | acetyltransferase |

|

| |||||||||

| CYP87D19 | Csa6G088710 | Cs710 | Melo3C022372 | Cm710 | Cla007082 | Cl710 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| CYP87D20 | Csa1G044890 | Cs890 | C11 carbonylase + C20 hydroxylase | Melo3C002192 | Cm890 | C11 carbonylase + C20 hydroxylase | Cla008355 | Cl890A | C11 carbonylase + C20 hydroxylase |

| Cla008354 | Cl890B | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| CYP712D8 | Csa3G698490 | Cs490 | Melo3C023960 | Cm490 | Cla017252 | Cl490 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| CYP88A60 | Csa3G903510 | Cs510 | Melo3C003387 | Cm510 | Cla016164 | Cl510 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| CYP88L2 | Csa3G903530 | Cs530 | PredictedT | Cm540 | |||||

| Csa3G903540 | Cs540 | C19 hydroxylase | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| CYP88L3 | Csa3G903550 | Cs550 | Melo3C003385T | Cm550A | |||||

| Melo3C003384T | Cm550B | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| CYP88L4 | Csa3G903560 | Cs560 | Melo3C003383T | Cm560A | Predicted | Cl560A | |||

| PredictedΔ | Cm560B | Cla016162 | Cl560B | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Regulatory genes | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| bHLH TF | Predicted | C1507 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| PredictedT | Cs508 | PredictedT | Cm508 | Cla011508 | ClBt | fruit specific | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Csa5G156220 | CsBl | leaf specific | Melo3C005612 | Cm612 | |||||

| Melo3C005611 | CmBt | fruit specific | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Csa5G157220 | Cs220 | Melo3C005610 | CmBr | root specific | Predicted | C1509 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Csa5G157230 | CsBt | fruit specific | PredictedΔ | Cm610 | Cla011510 | ClBr | root specific | ||

|

| |||||||||

| PredictedΔ | Cl511 | ||||||||

Abbr., abbreviation; Predicted, genes not annotated in the genome database; superscript T, truncated gene; superscript Δ, premature translational termination.

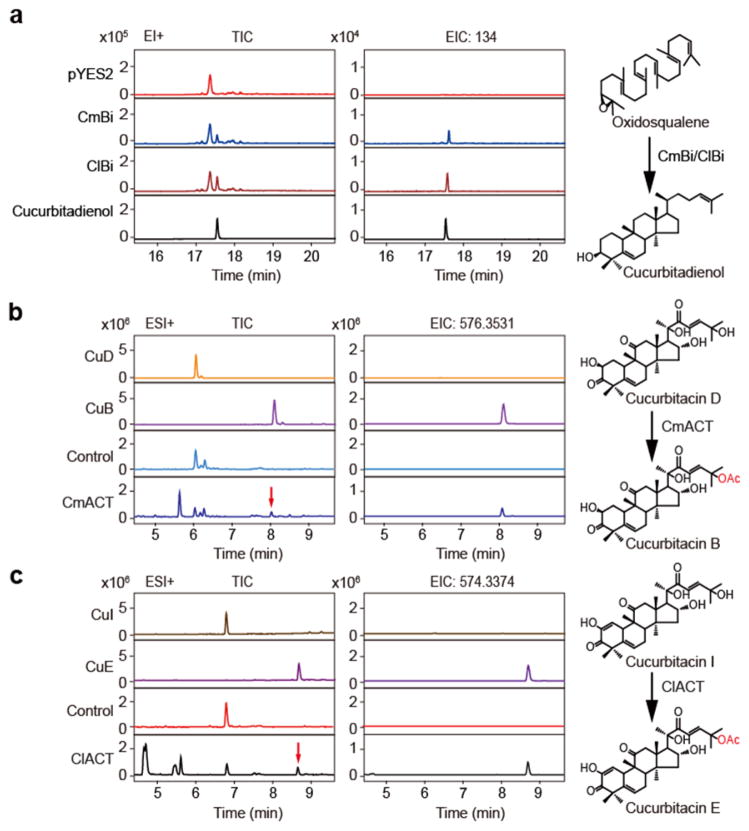

Subsequently, expression profiles of these genes as well as cucurbitacin distribution in melon and watermelon were analyzed. Interestingly, most of the candidates are highly expressed in the roots of seedlings or the fruit in wild lines, consistent with the cucurbitacin content in the different plant tissues (Fig. 1b), suggesting that these genes may be involved in CuB and CuE biosynthesis in melon and watermelon, respectively. In line with this speculation, the orthologous genes of CsBi, two putative OSCs (CmBi and ClBi) from the gene clusters in melon and watermelon respectively (Fig. 1b), are capable of cyclizing 2,3-oxidosqualene to generate cucurbitadienol in yeast (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2), which represents the first committed step in cucurbitacin biosynthesis24. In addition, CmACT and ClACT, the orthologs of the CsACT that is involved in the final CuC biosynthetic step (Fig. 1b), are also able to acetylate the cucurbitacin precursors CuD and CuI in the production of CuB and CuE, respectively (Fig. 2b, c). All three ACTs exhibit substrate promiscuity and have the capacity to acylate a wide range of substrates (e.g., CuD, CuI, and deacetyl CuC) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, the potential CuB and CuE biosynthetic enzymes are eight (CmBi, 6 CYPs, and CmACT) in melon and ten (ClBi, 8 CYPs, and ClACT) in watermelon, respectively.

Figure 2. Elucidation of the catalytic steps invovled in CuB and CuE biosynthesis.

(a) GC-MS profiles of the extracts prepared from the yeast that harbored CmBi, ClBi, or empty vector, and an authentic cucurbitadienol standard. EI+, electron ionization in positive ion mode; TIC, total ion chromatograms; EIC 134, extracted ion chromatograms of the characteristic fragment ion of cucurbitadienol at a mass/charge ratio (m/z) of 134. (b and c) UPLC-qTOF-MS analysis of the ACT-catalytic reaction products. The sample without CmACT or ClACT protein was served as the negative control. EIC 576.3531 and 574.3374, extracted ion chromatograms of the accurate parent ions at m/z 576.3531 [M+NH4]+ and 574.3374 [M+NH4]+, for CuB and CuE, respectively.

A new multifunctional CYP

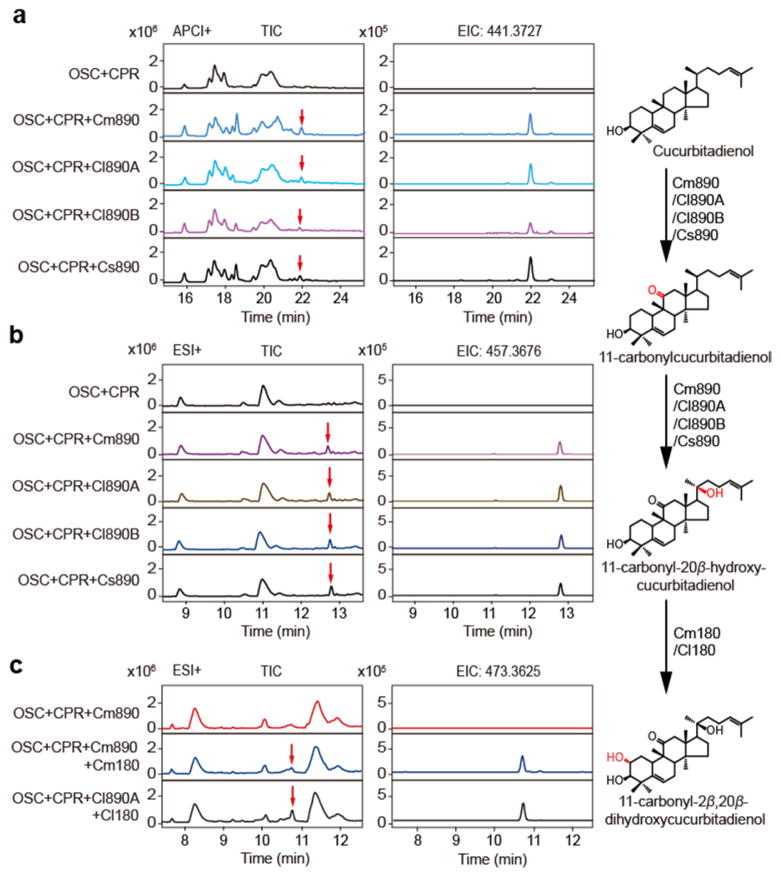

To identify the CYP involved in hydroxylation of the cucurbitadienol scaffold to product CuB and CuE, each of the potential CuB and CuE biosynthetic CYPs was expressed in the yeast engineered to produce cucurbitadienol, and the resulting metabolites analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Cm890, Cl890A and Cl890B (all belonging to the CYP87D subfamily) were each shown to oxidize cucurbitadienol to two new products (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). LC-MS/MS and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic analyses identified these compounds as 11-carbonylcucurbitadienol and 11-carbonyl-20-hydroxycucurbitadienol, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 5–11). Interestingly, of the two homologous CYP87Ds from watermelon (87% amino acid identity), Cl890A displayed a significantly higher catalytic activity than Cl890B (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e). We concluded that the multi-functional CYP87Ds catalyze two oxygenation reactions for CuB and CuE biosynthesis.

Figure 3. Functional elucidations of a multifunctional and a divergent CYPs.

(a) UPLC-qTOF-MS analysis of the extracts prepared from the yeast expressing OSC, CPR, and each candidate CYP with APCI in positive ion mode. One expected product (red arrows) is generated by CYP87D20 (Cm890, Cl890A, Cl890B, or Cs890). The structure of this product (right) was elucidated by MS/MS and NMR. EIC 441.3727, extracted ion chromatogram of the accurate parent ion at m/z of 441.3727 [M+H]+. (b) UPLC-qTOF-MS analysis of the extracts used in (a) with ESI in positive mode. One expected product (red arrows) is detected. The structure of this product (right) was elucidated by MS/MS and NMR. EIC 457.3676, extracted ion chromatogram of the accurate parent ion at m/z of 457.3676 [M+H]+. (c) UPLC-qTOF-MS analysis of the extracts prepared from the yeast accumulating 11-carbonyl-20β-hydroxycucurbitadienol and expressing candidate CYPs with ESI in positive ion mode. One expected product peak (red arrow) is generated by CYP81Q59 (Cm180 or Cl180). The structure of this product (below) was elucidated by MS/MS and NMR. EIC 473.3625, extracted ion chromatogram of the accurate parent ion at m/z of 473.3625 [M+H]+.

We noticed that cucumber has an orthologue (Cs890; CYP87D20) of the above melon and watermelon CYP87Ds with high sequence identity (96.2–98.3%). However, our previous studies could not detect any catalytic activity for this CYP. Accordingly, we re-investigated the activity of the Cs890 gene product in yeast using the same analytical method that utilizes atmospheric chemical ionization (APCI) in comparison to the electrospray ionization (ESI) in previous work. This experiment showed that cucumber CYP87D20 encoded in Cs890 could catalyze the same reactions as the orthologous CYP87Ds in melon and watermelon. Previously, we showed that Cs540 encodes a CYP that is able to hydroxylate C19 of cucurbitadienol5. When Cs540 and Cs890 were simultaneously expressed in yeast producing cucurbitadienol, both 19-hydroxycucurbitadienol and 11-carbonyl-20-hydroxycucurbitadienol could be detected, although the catalytic efficiency of Cs890 was higher than Cs540 (Supplementary Fig. 12). These results suggested that both Cs890 (CYP87D20) and Cs540 (CYP88L2) are capable of oxidizing cucurbitadienol. While the former enzyme is conserved among three cucurbits, the latter one is specific to cucumber. Based on the nearly perfect collinearity of the genomic regions among the three cucurbits, as well as the conserved biosynthetic processes, we conclude that the structural similarities among cucurbitacins are conferred by conserved orthologous enzymes.

Functional diversification of enzyme in the gene clusters

The above experiments with OSC, ACT and CYP87D20 support the notion that closely related enzymes contribute to the structural similarity among cucurbitacins. It is rational to predict that the diversity of the bitter chemicals should be conferred by those functionally non-conserved CYPs. We observed that the syntenic region of Cs540 has undergone dynamic evolution among the three cucurbits and that the orthologs of Cs540 are either truncated or missing in melon and watermelon. As Cs540 hydroxylates C19 of cucurbitadienol5, the hydroxyl modification that is present in CuC but absent in CuB/E (Fig. 1a), rapid evolution in this genomic region may explain this distinct chemical divergence of the three cucurbitacins at C-19.

We also noticed another difference in the syntenic regions between cucumber and melon/watermelon at the locus occupied by the non-expressed gene Cs180 in cucumber (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1a), where melon and watermelon encode highly transcribed counterpart genes (Cm180 and Cl180). Functional characterization of the CYPs annotated within this discrepant region may elucidate the potential mechanisms underlying cucurbitacin diversity. When Cm180 or Cl180 was expressed in the yeast engineered to produce 11-carbonyl-20-hydroxycucurbitadienol, a single new product was synthesized from the yeast strain (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 4c). After purification and NMR analysis, the structure of this new product was identified to be 11-carbonyl-2, 20-dihydroxycucurbitadienol (Supplementary Figs. 13–16). As the C2-hydroxyl moiety is lacking in cucumber CuC, this result clearly showed that expressional variation in the syntenic loci of Cs180 is responsible for the C2-hydroxyl pattern in CuB and CuE.

Convergent domestication of wild cucurbits

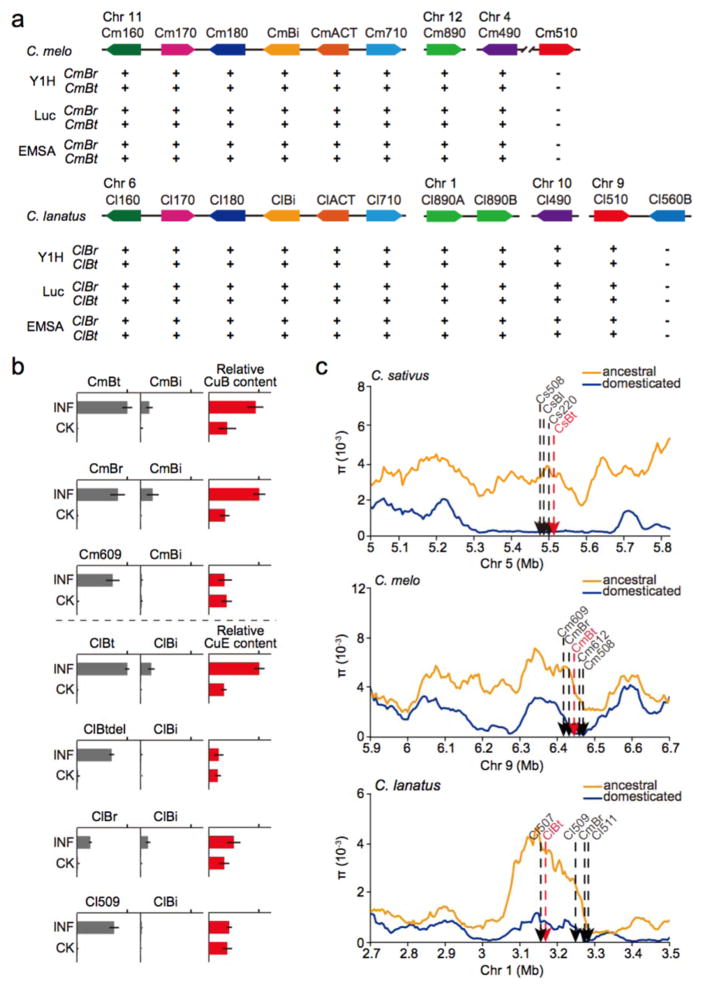

In cucumber, CsBl is the leaf-specific TF that directly regulates CuC biosynthetic genes in leaves, while CsBt is the fruit-specific TF, mutation of which has led to the domestication of the extremely bitter wild ancestor. Given the fact that cucurbitacins biosynthesis is conserved in cucurbits (described above), we presumed the CuB and CuE biosynthetic enzymes may also be modulated by conserved transcription factors (TFs). In order to unveil the putative regulators in melon and watermelon, we screened for the genes predicted to encode TFs within the syntenic region that contains CsBl and CsBt. Five bHLH TFs were identified in this collinear region in both melon and watermelon (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1e, g). As revealed by the expression profiles of these candidates as well as the cucurbitacin content in different tissues of seedling and fruit, CmBr and ClBr (Br, bitter root) are co-expressed with other CuB and CuE biosynthetic enzymes in the roots of melon and watermelon respectively, consistent with the bitterness distribution in these plants (Fig. 1b). Thus, these TFs are likely to be the potential root-specific regulators of cucurbitacin biosynthesis and probably participate in the chemical defense against underground herbivores in melon and watermelon. To identify the putative regulators of fruit bitterness in melon and watermelon, the expression patterns of TFs as well as the bitterness content in the fruits of wild and cultivated accessions were compared. Observation of the predominant expression of CmBt and ClBt in the bitter fruit of wild lines, with decreased expression in the cultivated lines, indicated that these two TFs may regulate fruit bitterness in melon and watermelon, respectively (Fig. 1b). More importantly, analogous to the function of Bl and Bt, these putative root-specific and fruit-specific regulators are able to directly activate transcription of the co-expressed genes for the CuB and CuE biosynthetic enzymes (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figs. 17–20), whereas two bHLH TFs (Cm609 and Cl509) from the same collinear region do not have the same capacity (Supplementary Fig. 21). A cotyledon transient agro-infiltration expression system was developed to further confirm the in vivo function of these regulators, as effective stable gene transformation in melon or watermelon is still not available. Expression of either CmBt or CmBr in non-bitter melon cotyledons activated the transcription of CmBi and induced CuB biosynthesis in this tissue (Fig. 4b). A similar result was observed when ClBt or ClBr were transiently expressed in watermelon cotyledons, resulting in CuE biosynthesis (Fig. 4b). Based on these results, we speculated that these four TFs (i.e., CmBt and CmBr, ClBt and ClBr) should be the tissue-specific cucurbitacin regulators in melon and watermelon, respectively.

Figure 4. Characterization of the tissue-specific bitterness regulators from melon or watermelon.

(a) Summary of the interactions between the promoters of candidate genes and the regulators from melon or watermelon (see Supplementary Figs 17–20 for further information). Y1H, yeast one-hybrid; Luc, luciferase trans-activation assay. (b) Transient expression of potential regulators in the non-bitter cotyledons of melon or watermelon activated the transcription of OSC and induced generation of bitter chemicals. Gene expression levels and contents of cucurbitacins were determined 5 days after agroinfiltration. Relative values are shown with identical scales (means ± SEM, n=3 biological replicates). INF, sample infiltrated with TF expression construct; CK, sample infiltrated with empty vector. (c) Comparison of the domestication sweep region among the three cucurbits. Numeric pi values are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The fruit-specific regulator genes (indicated in red) in melon or watermelon are also located within a large domestication sweep region. The Y axis represents the distribution of nucleotide diversity. Chr, chromosome.

Since disruption of bitterness regulation in the fruit of wild cucumber has led to the domesticated non-bitter cultivar5, we questioned whether convergent domestication of wild cucurbits was likely to be conferred by the mutations within the conserved fruit-specific regulators. Both CmBt and ClBt are located within the domestication sweep region, as for the domestication gene (Bt) in cucumber, suggesting their potential roles in crop domestication (Fig. 4c). In order to identify the genetic variants associated with the bitter fruit phenotype in watermelon, sequences of ClBt from seven bitter wild lines were compared with the genes from thirteen non-bitter cultivars. A single base pair mutation at the second exon of ClBt resulting in a premature protein translation in cultivated watermelon was identified (Supplementary Fig. 22a). This SNP corresponds with the bitter fruit phenotype: the nucleotide at position 382 is T in thirteen non-bitter cultivars and C in seven bitter wild lines. The mutated ClBt encodes a truncated protein, predicted to be around about half the length of the wild type protein (127 versus 249 amino acids), and so is likely to be nonfunctional. As expected, the truncated ClBt gene did not show regulatory ability (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 22b, c, d), which may explain the lack of CuE production in the fruit of cultivated watermelon. These discoveries support the hypothesis that changes within the homologs of fruit bitterness regulators have caused convergent domestication of cucurbits. For CmBt, we failed to amplify the whole sequence of CmBt, most likely due to a genome assembly error. Instead, the coding region of CmBt was obtained by applying the RACE method. Although no coding differences were found in CmBt between wild and cultivated lines, its expression is substantially reduced in the cultivated lines (Fig. 1b), suggesting that the causative mutation that gave rise to the non-bitter melon phenotype may have occurred in the promoter region of this gene, similar to the situation for Bt in cucumber.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the genomic synteny among cucurbits to identify biosynthetic pathway and master regulators of cucurbitacin in melon and watermelon. During crop domestication, similar human demands have led to convergent phenotypic evolution (e.g., bigger fruit size and better fruit taste)25. Although the molecular events underlying these convergent phenotype alterations are still only poorly understood, an increasing number of examples support the tenet that causative mutations at orthologous genes may underlie convergent changes in key traits in crop domestigation25. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that the loss-of-bitterness domestication of three wild cucurbits was caused by mutations occurring at homologous fruit bitterness regulators at the syntenic regions. Breeding has led to selection for loss of function of these direct fruit-specific regulators (i.e., CsBt, ClBt and CmBt) during the domestication process of wild cucurbits, avoiding unwanted additional pleiotropic effects that are likely caused by the changes in upstream regulators as well as reserving the cucurbitacins biosynthetic machinery for herbivore resistance, so increasing the likelihood of the trait being selected and fixed. Interestingly, CmBr and CmBt are homologs but not orthologs of Bl and Bt, respectively. For instance, CmBr regulates bitterness biosynthesis in the roots of melon, while its orthologous genes Cs220 in cucumber and Cl509 in watermelon have lost their function (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1e). A similar situation was also observed in watermelon for ClBt (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1e). ClBt is specific to watermelon among three cucurbits, since the corresponding genes are truncated in cucumber and melon. On the other hand, the region collinear with Bl and Bt in watermelon has two full-length homologues (Cl507 and Cl511) that are absent in cucumber and melon. Based on their sequence similarity (74% amino acid identity), it is likely that these two watermelon-specific genes have resulted from gene duplication after speciation of the genus Citrullus followed by rapid rate sequence evolution (Supplementary Fig. 1g).

Closely related plants are known to synthesize structurally similar but distinct specialized metabolites. These conserved yet divergent structural features of specialized metabolites may be due to adaptive evolution in response to various biotic stresses (e.g., insects and pathogens)26, or alternatively to random mutation and genetic drift. One key finding from this work is that the major gene clusters for cucurbitacin biosynthesis are highly conserved in the three cucurbits. This suggests that selective pressure may have been imposed on cucurbits to retain these biosynthetic gene clusters, thereby maintaining effective biosynthesis of specialized metabolites27–29. While the three clusters all produce cucurbitacin-derived triterpenes, minor differences in the structures of the pathway end-products leading to diversification have arisen from gene duplications and random mutations. By comparing the cucurbitacin-biosynthetic gene clusters in the three Cucurbitaceae species, we could accurately correlate the unique genomic features to subtle, but potentially important, structural diversification in different cucurbitacins.

Such experimental data, uniquely linking comparative genomic features to catalytic activities, provide compelling evidence of the in planta biochemical functions of these regions without involving laborious mutant screening or RNA interference analysis. Considering the difficulties of precisely assigning specific enzyme functions for complex, specialized metabolites (e.g., cucurbitacins) in non-model organisms, our approaches in combining comparative genomics and biochemical analysis could be effective tools to expedite gene discovery. Because the numerous chemical structures of distinct cucurbitacins are known from Cucurbitaceae plants and genome sequencing has become affordable, we can infer and validate the biochemical functions of various genes by simply comparing different genomic features (e.g., pseudogene, absence and presence of genes) among many different cucurbits. It is known that subtle differences in the structures of specialized metabolites can markedly alter their pharmaceutical and biological activities30–32. Therefore, the new enzymes identified in this work can be valuable additions to the catalytic tool kits for customized cucurbitacin production by microbial or plant metabolic engineering33,34.

Methods

Gene expression in yeast

The coding sequences of potential CuB and CuE biosynthetic genes were cloned from the cDNA mixture of root of melon and watermelon, respectively. The purified PCR products were cloned into the pMD19-T vector (TAKARA) and sequenced for errors. The pYES2 (Invitrogen) was modified by replacing the Ura selection marker with Trp, Leu, and His markers, respectively. Gene was constructed into pYES2 or modified pYES2 for yeast in vivo assay using an In-Fusion Cloning Kit (Clontech) with the primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. Yeast INVSc1 (Invitrogen) strain was transformed with different construct. The recombinant cells were first cultured in SC minimal medium containing 2% glucose at 30°C. For protein induction, cells were collected and resuspended in SC minimal medium containing 2% galactose instead of glucose, and cultured at 30°C for 2 days.

Yeast extract preparation

Yeast harboring CPR and each candidate CYPs was cultured and then centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in 20% KOH/50% EtOH (1:1) and treated with alkali lysis method for 1 h at 95°C. Lysate was extracted twice with the same volume of petroleum ether (PE, 60~90°C), the PE was gathered and then dried with blowing nitrogen gas.

In vitro actyltransferase assay

E. coli cells transformed with the pET32a vector harboring each putative ACT gene (Cs700, Cm700, or Cl700) were grown overnight at 37°C in 2 mL of LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL ampicillin. After cultivation, 500 μL of this inoculum was added to 250 mL of LB supplemented with 50 μg/mL ampicillin and grown at 37°C. When cells grew to an OD600 of 0.4, IPTG was added to the inoculum making final concentration at 0.5 mM. After incubating for 24 h at 16°C, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was then resuspended with 20 ml of assay buffer [50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole], and then disrupted on ice by sonication. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. Recombinant His-tagged ACT was purified by Ni-affinity chromatography. Protein concentration was determined by SDS/PAGE using BSA as quantification standard.

ACT enzyme activity assays were performed by incubating 40 μg of the purified recombinant protein in 1 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 400 μM acetyl-CoA and 400 μM substrate. After incubating for 30 min at 31°C, the reaction mixture was extracted three times with an equivalent volume ethyl acetate, and the solvent was concentrated using blowing nitrogen gas. The crude product was dissolved in methyl alcohol and analyzed by LC-MS.

UPLC-ESI-qTOF-MS analysis of yeast extract

The yeast extracts were dissolved in methanol and the solution was filtered through 0.22 μm membrane prior to injection. Chromatography was performed on an Agilent 1290 UPLC system using a ZORBAX SB-C18 column (1.8 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm, Agilent). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution (v/v, solvent A) and acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (v/v, solvent B). The flow was 0.3 mL/min, and the injection volume was 1 μL. A linear gradient with the following proportion of phase B (tmin, B%) was used: (0, 30), (17, 100), (22, 100). The UPLC was coupled with an electrospray ionization (ESI), a hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight (qTOF) mass spectrometer (model 6540, Agilent). The mass acquisition was performed on positive ionization and full scan (50–800 Da) modes. Spray parameters were as follows: gas temp. 350°C, gas flow 11 L/min, nebulizer 32 psi, sheath gas temp. 350°C, sheath gas flow 8.5 L/min, Vcap 4,000, nozzle voltage 500 V, fragment voltage 135 V.

Transient gene expression in the cotyledon of melon or watermelon

The coding sequence of CmBr, CmBt, ClBr or ClBt was fused into the binary vector (pCAMBIA1300) downstream of the 35S promoter and sequenced for error. The construct was then transformed into EHA105. After cultivation, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 10 mM MES buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 200 μM acetosyringone (Sigma). The final OD600 of the Agrobacterium suspension was adjusted to 0.4. After incubation at room temperature for 2–4 hours, the Agrobacterium suspension was infiltrated into the cotyledon of eight-day-old seedling from the adaxial side using a needleless syringe. To maximize the gene expression, the infiltrated plants were sampled at 3, 5 and 7 days after the infiltration. These experiments were repeated independently for at least ten times with the similar results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jinwei Ren (Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for providing NMR assay platform and Lida Han (Institute of Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for experimental assistance. The CYPs were named according to the alignment made by David Nelson (http://drnelson.uthsc.edu/cytochromeP450.html). This work was supported by founding from the National Key R & D Program for Crop Breeding (2016YFD0100307), National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (31225025 to S.H.), the National Program on Key Basic Research Projects in China (the 973 Program; 2012CB113900), the leading talents of Guangdong province Program (00201515), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31322047, 31401886 and 31101550), The Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-IVFCAAS), the Chinese Ministry of Finance (1251610601001), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2014M550902), the Discovery Grant from National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and Canada Research Chair program to D.K. Ro, and the UK Biotechnological and Biological Sciences Research Council Institute Strategic Programme Grant ‘Understanding and Exploiting Plant and Microbial Metabolism’ [BB/J004561/1], the John Innes Foundation, and the Genomes to Natural Products National Institutes of Health Programme grant U01GM110699 awards to A. Osbourn. This work was also supported by the Shenzhen Municipal and Dapeng District Governments. Institute of Flowers and Vegetables has two pending patent applications relating to the genes reported in this study.

Footnotes

Author contributions

S.H, and Y.S. conceived and organized the research. Y.M., Y.S., J.Z., H.W., Z.L., K.Z., Y.Z., M.L., H.Z., and P.H. performed biology experiments. Y.Z., L.D., X.X., X.L., Z.Q., and X.L. performed metabolic detection. Y.Z., Y.M., Y.S., D.R., J.Z., L.D., X.X., T.L., S.Z., Q.H., J.R., X.L., P.H., Z.Q., X.L., Z.Z., H.K., and A.O. performed data analysis. Y.S., D.R., Y.Z., and S.H. wrote the manuscript. J.Z., L.D., J.R., P.T., Z.Z., H.K., and A.O. revised the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Speed MP, Fenton A, Jones MG, Ruxton GD, Brockhurst MA. Coevolution can explain defensive secondary metabolite diversity in plants. New Phytol. 2015;208:1251–1263. doi: 10.1111/nph.13560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metcalf RL, Metcalf RA, Rhodes AM. Cucurbitacins as kairomones for diabroticite beetles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3769–3772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Da Costa CP, Jones CM. Cucumber beetle resistance and mite susceptibility controlled by the bitter gene in Cucumis sativus L. Science. 1971;172:1145–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3988.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JC, Chiu MH, Nie RL, Cordell GA, Qiu SX. Cucurbitacins and cucurbitane glycosides: structures and biological activities. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:386–399. doi: 10.1039/b418841c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shang Y, et al. Biosynthesis, regulation, and domestication of bitterness in cucumber. Science. 2014;346:1084–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.1259215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, et al. Biological activities and potential molecular targets of cucurbitacins: a focus on cancer. Anti-cancer drugs. 2012;23:777–787. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3283541384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thoennissen NH, et al. Cucurbitacin B induces apoptosis by inhibition of the JAK/STAT pathway and potentiates antiproliferative effects of gemcitabine on pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5876–5884. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lester G. Melon (Cucumis melo L.) fruit nutritional quality and health functionality. HortTechnology. 1997;7:222–227. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuo K, DeMilo AB, Schroder RFW, Martin PAW. Rapid high-performance liquid chromatography method to quantitate elaterinide in juice and reconstituted residues from a bitter mutant of Hawkesbury watermelon. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:2755–2759. doi: 10.1021/jf9811572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong Y, et al. Cucurbitacin E, a tetracyclic triterpenes compound from Chinese medicine, inhibits tumor angiogenesis through VEGFR2-mediated Jak2–STAT3 signaling pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:2097–2104. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwanski GB, et al. Cucurbitacin B, a novel in vivo potentiator of gemcitabine with low toxicity in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Bri J Pharmacol. 2010;160:998–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zerikly M, Challis GL. Strategies for the discovery of new natural products by genome mining. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:625–633. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frey M, et al. Analysis of a chemical plant defense mechanism in grasses. Science. 1997;277:696–699. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winzer T, et al. A Papaver somniferum 10-gene cluster for synthesis of the anticancer alkaloid noscapine. Science. 2012;336:1704–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1220757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field B, Osbourn AE. Metabolic diversification—independent assembly of operon-like gene clusters in different plants. Science. 2008;320:543–547. doi: 10.1126/science.1154990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itkin M, et al. Biosynthesis of antinutritional alkaloids in solanaceous crops is mediated by clustered genes. Science. 2013;341:175–179. doi: 10.1126/science.1240230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Luca V, Salim V, Atsumi SM, Yu F. Mining the biodiversity of plants: a revolution in the making. Science. 2012;336:1658–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.1217410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falara V, et al. The tomato terpene synthase gene family. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:770–789. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.179648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nützmann HW, Huang A, Osbourn A. Plant metabolic clusters–from genetics to genomics. New Phytol. 2016;211:771–789. doi: 10.1111/nph.13981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chae L, Kim T, Nilo-Poyanco R, Rhee SY. Genomic signatures of specialized metabolism in plants. Science. 2014;344:510–513. doi: 10.1126/science.1252076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang S, et al. The genome of the cucumber, Cucumis sativus L. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1275–1281. doi: 10.1038/ng.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Mas J, et al. The genome of melon (Cucumis melo L.) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11872–11877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205415109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo S, et al. The draft genome of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) and resequencing of 20 diverse accessions. Nat Genet. 2013;45:51–58. doi: 10.1038/ng.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibuya M, Adachi S, Ebizuka Y. Cucurbitadienol synthase, the first committed enzyme for cucurbitacin biosynthesis, is a distinct enzyme from cycloartenol synthase for phytosterol biosynthesis. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:6995–7003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenser T, Theiβen G. Molecular mechanisms involved in convergent crop domestication. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:704–714. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keeling CI, Bohlmann J. Genes, enzymes and chemicals of terpenoid diversity in the constitutive and induced defence of conifers against insects and pathogens. New Phytol. 2006;170:657–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field B, et al. Formation of plant metabolic gene clusters within dynamic chromosomal regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16116–16121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109273108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zi J, Mafu S, Peters RJ. To gibberellins and beyond! Surveying the evolution of (di) terpenoid metabolism. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65:259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-035705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuba Y, et al. Evolution of a complex locus for terpene biosynthesis in Solanum. The Plant Cell. 2013;25:2022–2036. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.111013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaturvedi D, Goswami A, Saikia PP, Barua NC, Rao PG. Artemisinin and its derivatives: a novel class of anti-malarial and anti-cancer agents. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:435–454. doi: 10.1039/b816679j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masters BA, et al. In vitro myotoxicity of the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, pravastatin, lovastatin, and simvastatin, using neonatal rat skeletal myocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995;131:163–174. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strømgaard K, et al. Ginkgolide derivatives for photolabeling studies: preparation and pharmacological evaluation. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4038–4046. doi: 10.1021/jm020147w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ro DK, et al. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature. 2006;440:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paddon CJ, et al. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature. 2013;496:528–532. doi: 10.1038/nature12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.