Abstract

Objectives

Studies suggest that rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-related autoimmunity is initiated at a mucosal site. However, the factors associated with the mucosal generation of this autoimmunity are unknown, especially in individuals who are at-risk for future RA. Therefore, we tested anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies in the sputum of RA-free first-degree relatives (FDRs) of RA patients and patients with classifiable RA.

Methods

We evaluated induced sputum and serum from 67 FDRs and 20 RA subjects for anti-CCP-IgA and anti-CCP-IgG, with cut-off levels for positivity determined in a control population. Sputum was also evaluated for cell counts, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) using sandwich ELISAs for protein/nucleic acid complexes, and total citrulline.

Results

Sputum anti-CCP-IgA and/or anti-CCP-IgG was positive in 17/67 (25%) FDRs and 14/20 (70%) RA subjects, including a portion of FDRs who were serum anti-CCP negative. In FDRs, elevations of sputum anti-CCP-IgA and anti-CCP-IgG were associated with elevated sputum cell counts and levels of NET complexes. Anti-CCP-IgA was associated with ever-smoking and elevated sputum citrulline levels.

Conclusions

Anti-CCP is elevated in the sputum of FDRs, including seronegative FDRs, suggesting the lung may be one site of anti-CCP generation in this population. The association of anti-CCP with elevated cell counts and NET levels in FDRs supports a hypothesis that local airway inflammation and NET formation may drive anti-CCP production in the lung and may promote the early stages of RA development. Longitudinal studies are needed to follow the evolution of these processes relative to the development of systemic autoimmunity and articular RA.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, ACPA, anti-CCP

INTRODUCTION

Seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is characterized by disease-associated autoantibodies, including antibodies to citrullinated proteins/peptides (ACPAs) that are commonly measured using anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) assays. In established RA, ACPA isotypes including immunoglobulin (Ig)-A and IgG are prevalent, specific, and associated with higher disease activity, suggesting they play an important role in RA pathogenesis (1–4). Therefore, understanding the development of ACPA isotypes could provide further insight into the etio-pathogenesis of RA.

It is well established that ACPAs can be present for years prior to the onset of inflammatory arthritis (IA) during a period of systemic autoimmunity associated with RA that can be termed ‘preclinical’ RA and defined as the presence of circulating RA-related autoimmunity prior to the onset of clinically-apparent synovitis (2–10). Importantly, individuals without classifiable RA who have circulating ACPA do not exhibit synovitis as assessed by physical examination (5, 11), imaging with ultrasound or MRI (5, 11–13) or synovial biopsy (12, 13). These findings strongly suggest that in order to understand the initial steps in the generation of ACPA, studies must examine individuals who have not yet developed clinically apparent synovitis and classifiable RA. In addition, these data support that ACPAs originate at a site outside of the joint.

As to where that site is, emerging data support the hypothesis that ACPAs may be initially generated at a mucosal surface (2–5, 14–20). For example, serum ACPA-IgA is elevated in populations who are at-risk for future RA, including first-degree relatives (FDR) of RA patients (2–4). Additionally, the strong association between smoking, lung disease and ACPA-positive RA supports that the lung mucosa may be a particularly relevant mucosal site of ACPA generation (17–19). Furthermore, our group has previously demonstrated that circulating RA-related autoantibodies were associated with airway abnormalities in the absence of IA (5), and using induced sputum testing, ACPAs are detectable in the lung of a portion of IA-free FDRs (14).

While these data are intriguing, the mechanisms that trigger local ACPA production in the lung are unknown; however, understanding the factors that may drive the initial development of ACPA, and in particular ACPA-IgA given IgA’s role in mucosal immunity, may ultimately lead to novel approaches for the prediction, treatment and prevention of RA.

With regard to potential factors that may be associated with ACPA formation at a mucosal surface, there are several candidates including exposures to environmental agents such as smoking and local inflammation that can lead to citrullination. In addition, multiple studies have suggested a role for neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation (termed NETosis) in RA. NETosis is a peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD)-4 mediated process by which neutrophils decondense and externalize their DNA in complex with neutrophil cytoplasmic granule proteins such as myeloperoxidase (MPO) and neutrophil elastase (NE) (21–23). Enhanced NETosis has been associated with ACPA peripherally and in the joints of patients with established RA (24–26). While NET formation in sputum has been associated with lung disease (27–29), it is unknown if NETs are associated with ACPA in the lung of subjects at-risk for RA.

In order to explore factors associated with APCA generation in the lung, in this study we evaluated IA-free FDRs who are at higher risk for future RA, specifically FDRs of patients with RA, and using induced sputum, we investigated isotype-specific anti-CCP levels and a variety of factors including demographics, environmental exposures, genetic factors, and sputum biomarkers including cell counts, total citrullination and markers of NETosis.

METHODS

Study subjects

Subjects were recruited from the Studies of the Etiology of RA (SERA) cohort that is described in detail elsewhere (30, 31). Briefly, SERA evaluates in a prospective fashion FDRs of RA patients, with these FDRs being at elevated risk of future RA based on their family history of disease (32, 33), making them a reasonable group to study to evaluate the earliest stages of RA. For this study, SERA subjects were recruited from the Denver, CO, USA study site between January 2011 and October 2015.

FDRs

We recruited SERA FDRs who were without IA. FDRs could be with or without serum anti-CCP determined by commercial assay testing. As our group and others have reported, IA-free FDRs have a higher prevalence of serum anti-CCP positivity compared to the general population, including 9.5% positivity for the commercially-available anti-CCP3.1 (IgG/IgA, Inova Diagnostics, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA)(3, 6).

Early RA subjects

We recruited subjects with classifiable RA who were within 1 year of RA diagnosis and were serum anti-CCP3.1-positive. RA subjects were recruited sequentially from rheumatology clinics or from SERA research study visits if a subject developed incident IA that met classification criteria during prospective follow-up. RA was confirmed by medical chart review, and all subjects met the 2010 ACR/EULAR RA classification criteria (34).

Healthy Control subjects

In order to determine cut-off levels for anti-CCP isotype positivity, we recruited healthy control subjects from the community through local advertisement who were serum anti-CCP3.1-negative, without RA or IA, and without an FDR with RA.

Study visit

All subjects had paired collection of blood and sputum collected on the same day except for 3 subjects who had sputum collected within 2 weeks of blood collection. Subjects without RA underwent a joint-focused interview and 66/68-count joint examination by a trained rheumatologist to assure no clinically-evident IA. Standardized questionnaires were used to obtain demographic information and self-reported histories of smoking and chronic lung disease.

Genetic testing

Blood was tested for the presence of alleles containing the shared epitope (SE) using previously described methodologies (30). The alleles considered to contain the SE were as follows: DRB1*04:01, 04:04, 04:05, 04:08, 04:09, 04:10, and DR1 01:01 and 01:02.

Sputum collection

Induced sputum was collected and processed using established protocols that are described in detail elsewhere (14). Briefly, sputum samples were collected over 15 minutes using hypertonic nebulized saline. The entire sputum sample underwent dilution with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) followed by syringe-based mechanical homogenization. Samples collected after September 2013 had manual cell count with cell differential performed using a hemocytometer and cytocentrifugation. Cell counts were reported in cells x104/mL. To minimize salivary contamination of sputum samples, subjects underwent oral wash prior to sputum collection. In addition, as per established methods, during the sputum collection, subjects were asked to spit any saliva into a separate plastic container, and they were instructed to only use the sputum collection cup when producing a sample from coughing (35). Furthermore, the only samples used for analyses were those consistent with lower airways origin by demonstrating <10 squamous epithelial cells/high power field on light microscopy or <80% squamous epithelial cells on cell differential (35, 36).

After homogenization, samples underwent centrifugation, and proteinase inhibitors phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) were added to the supernatant. A mucolytic agent such as dithiothreitol was not used to avoid the destruction of disulfide bonds that could affect antibody structure and conformation. All sputum biomarker testing was performed on the cell-free supernatant except for cell count and differential that was performed prior to centrifugation. Because sputum testing was performed on diluted samples, all sputum results reported in this manuscript have been multiplied by the sample’s dilution factor that was calculated based on the amount of PBS added and the sample’s original weight.

Serum and sputum anti-CCP-IgA and anti-CCP-IgG testing

In the University of Colorado Division of Rheumatology Clinical Research Laboratory, serum and sputum underwent ELISA testing for anti-CCP-IgA and anti-CCP-IgG using a CCP3 plate and the respective conjugate (Inova Diagnostics, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA; for research only). A positive control sample was provided by the manufacturer for each isotype, and results for levels in sputum and serum are reported in relative units (RU) based on the optical density (OD) of the subjects’ sample divided by the OD of the positive control. This approach allowed us to account for any plate-to-plate variation. Cut-off levels for positivity for anti-CCP isotypes were set at a level that was present in <5% of our healthy Control subjects, thereby corresponding to a level at or above the 95th percentile in Controls. Of note, cut-off levels for both serum and sputum anti-CCP isotypes were set using the same control group.

In this study, serum and sputum anti-CCP levels were measured in duplicate wells. For sputum, the mean coefficient of variation between wells was 4.8% for anti-CCP-IgA and 5.3% for anti-CCP-IgG. To further validate the anti-CCP isotype assays, we tested serum from 6 subjects without RA, 3 of whom were previously found to have high anti-CCP isotype levels and 3 with low levels. We determined intra-assay variability for each isotype by testing serum from each subject in 10 wells each. The mean coefficient of variation was 8.4% for anti-CCP-IgA and 8.0% for anti-CCP-IgG.

Total Ig testing

In subjects with adequate sputum volume available after anti-CCP testing, total IgA and IgG level (mg/dL) was tested in sputum (Siemens BN II nephelometry cerebrospinal fluid assessment system) and serum (Beckman-Coulter Synchron nephelometry system).

NET levels

In samples collected prior to January 2015 that had adequate sputum volume after anti-CCP and Ig testing, the level of NETosis was measured as NET remnants in sputum cell-free supernatant. Specifically, NET-associated protein/nucleic acid complexes were quantified using a sandwich ELISA that detects complexes of DNA-MPO and DNA-NE as previously described (37) and as follows: for DNA:MPO complexes, high-binding 96-well ELISA microplates were incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-human MPO (clone 4A4; AbD, Serotec) in coating buffer from the Cell Death Detection ELISA kit (Roche). After blocking with 1% BSA, plates were incubated overnight at 4°C with 10% sputum in blocking buffer, washed and anti-DNA-POD (Roche) was added for 1.5 hours at room temperature. TMB substrate (Sigma) was then added and absorbance measured at 450 nm after addition of stop reagent (Sigma). For DNA-NE complexes, methods were similar as for DNA:MPO. The antibody used to coat plates was rabbit anti-human NE (Calbiochem). After overnight incubation with sputum, plates were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with mouse anti-dsDNA monoclonal antibody (Millipore), followed by anti-mouse IgG-HRP conjugate (Biorad). Procedure was then completed as for DNA:MPO complexes.

Total citrulline content

In sputum samples that had NET testing, total citrulline level was quantified in nmol of citrulline/mL using the detection step of the Color Development Reagent (COLDER) assay and quantified as previously described (38–40). To avoid detection of urea and methylurea with this assay, a 20-fold excess of urease was added to each sputum sample for 15 minutes at 25°C prior to testing.

Statistical analyses

Prevalence of positivity was compared between groups using Chi-square/Fisher’s exact test and within groups using McNemar’s test. Because of a non-normal distribution of anti-CCP isotype levels, non-parametric testing was used to compare anti-CCP levels across groups (Mann-Whitney U), and perform correlation analyses between anti-CCP levels and other factors (Spearman’s correlation coefficient). In addition, linear regression was used to evaluate the relationship between sputum anti-CCP levels and sputum cell counts, NETs and citrulline, and accounting for adjustment variables when necessary, and we report the t-statistic and p-value for each relationship. In these linear models, sputum anti-CCP levels and cell counts were log transformed to meet the assumption of normality for linear regression. The potential confounders of age, sex, ever-smoking, SE positivity and citrulline level were included in the model(s), and removed at an alpha >0.10 level.

Analyses were performed using SPSS (version 23) and SAS (version 9.4). Figures were generated in GraphPad Prism (version 7).

Ethical considerations

All study procedures were approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

We evaluated 67 FDRs, 20 RA and 70 healthy Control subjects. Characteristics of these subjects are reported in Table 1. There was no difference in age, sex, presence of ≥1 SE allele, history of ever-smoking or chronic lung disease between FDR and RA subjects. RA subjects were more likely to be current smokers and less likely to be non-Hispanic white. Compared to FDR and RA subjects, Controls were younger, less often SE-positive, and less often smokers.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| FDRs1 N=67 |

RA2 N=20 |

p-value3 | Controls N=70 |

p-value4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Median (range) | 52 (23–77) | 54 (33–66) | 0.79 | 36 (20–71) | <0.01 |

| Female, N (%) | 47 (70) | 13 (65) | 0.66 | 56 (80) | 0.27 |

| Non-Hispanic white, N (%) | 48 (72) | 9 (45) | 0.03 | 49 (70) | 0.07 |

| Ever-smoker, N (%) | 24 (36) | 9 (45) | 0.46 | 19 (27) | 0.27 |

| Current-smoker, N (%) | 5 (8) | 7 (35) | <0.01 | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| Shared Epitope (≥1 allele), N (%)5 | 42 (63) | 10 (59)5 | 0.77 | 24 (35) | <0.01 |

| History of chronic lung disease, N (%)6 | 14 (21) | 3 (15) | 0.75 | 8 (11) | 0.32 |

Seven of 67 (10%) FDRs were serum anti-CCP3.1 positive. There was no significant difference between age, sex, race, history of smoking, SE positivity or chronic lung disease in those who were serum CCP3.1 positive vs. serum CCP3.1 negative.

Non-biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARD) were taken by 13/20 (65%) RA subjects.

P-value is calculated comparing FDR and RA subjects using Mann-Whitney U for age and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for other characteristics.

P-value is calculated comparing Controls, FDR and RA subjects using Kruskal Wallis test for age and Chi-square/Fisher’s exact test for other characteristics.

17/20 RA and 69/70 Control subjects had blood available for SE testing

The presence of chronic lung disease was determined by self-report using a questionnaire that asked if subjects had a health care provider diagnosed history of asthma, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, interstitial lung disease, lung cancer, pulmonary artery hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, or other chronic lung disease.

Sputum anti-CCP-IgA and anti-CCP-IgG positivity in FDR and RA subjects

Seventeen of 67 (25.4%) FDRs were positive for anti-CCP-IgA and/or anti-CCP-IgG in sputum (Table 2). Within the FDRs, there was a non-significant trend that sputum anti-CCP-IgA positivity was more prevalent than anti-CCP-IgG [16/67 (23.9%) vs. 11/67 (16.4%), p=0.13]. Data on Controls are included in Figure 1, and because they were used to establish cut-off values, these subjects are not studied relative to FDR or RA populations.

Table 2.

Sputum and serum anti-CCP positivity in FDR and RA subjects

| FDRs (N=67) | RA (N=20) | p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sputum, N (%) | |||

| Anti-CCP-IgA and/or CCP-IgG (+) | 17 (25)2 | 14 (70)2 | <0.01 |

| Anti-CCP-IgA(+)/IgG(+) | 10 (15) | 8 (40) | 0.03 |

| Anti-CCP-IgA(+)/IgG(−) | 6 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.33 |

| Anti-CCP-IgA(−)/IgG(+) | 1 (1) | 6 (30) | <0.01 |

| Anti-CCP-IgA(−)/IgG(−) | 50 (75) | 6 (30) | <0.01 |

| Serum, N (%) | |||

| Anti-CCP-IgA and/or CCP-IgG (+) | 12 (18)3 | 20 (100)3 | <0.01 |

| Anti-CCP-IgA(+)/IgG(+) | 2 (3) | 12 (60) | <0.01 |

| Anti-CCP-IgA(+)/IgG(−) | 8 (12) | 1 (5) | 0.68 |

| Anti-CCP-IgA(−)/IgG(+) | 2 (3) | 7 (35) | <0.01 |

| Anti-CCP-IgA(−)/IgG(−) | 55 (82) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

P-value is calculated comparing prevalence of positivity between FDRs and RA subjects using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test.

When comparing sputum anti-CCP isotype positivity within subjects using McNemar’s test, FDRs were more often anti-CCP-IgA vs. anti-CCP-IgG (p=0.13), while RA subjects were more often anti-CCP-IgG vs. anti-CCP-IgA (p=0.03).

When comparing serum anti-CCP isotype positivity within subjects using McNemar’s test, FDRs were more often anti-CCP-IgA vs. anti-CCP-IgG (p=0.11), while RA subjects were more often anti-CCP-IgG vs. anti-CCP-IgA (p=0.07).

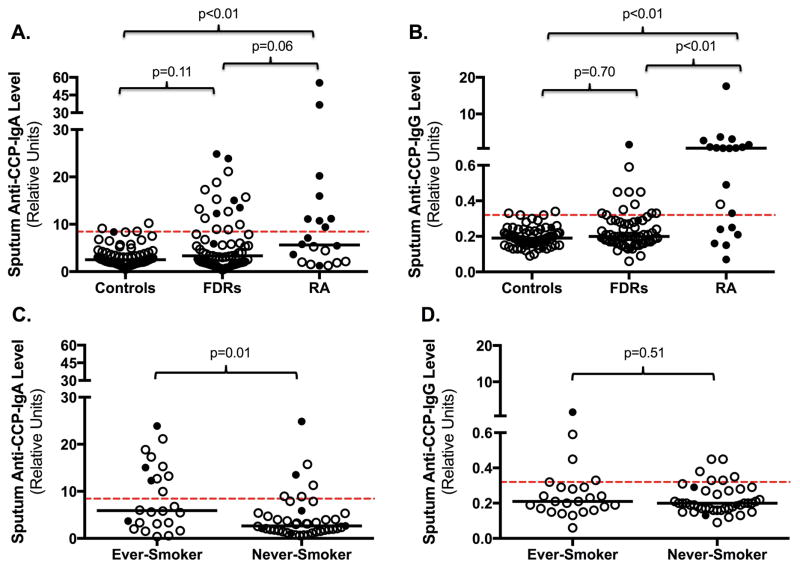

Figure 1. Distribution of sputum anti-CCP-IgA and anti-CCP-IgG levels in all subjects and FDRs stratified by smoking status.

Depicted are the distributions of sputum anti-CCP-IgA (Panel A) and anti-CCP-IgG (Panel B) in Controls, FDRs and RA subjects. Panels C and D depict the distribution of sputum anti-CCP-IgA (Panel C) and anti-CCP-IgG (Panel D) for FDR subjects stratified by ever- or never-smoking history. P-values compare differences in anti-CCP levels between groups using non-parametric testing.

=Serum anti-CCP-negative for the anti-CCP isotype associated with that panel; ●=Serum anti-CCP-positive for the anti-CCP isotype associated with that panel; ---- Cut-off level for anti-CCP positivity; — Median anti-CCP level.

=Serum anti-CCP-negative for the anti-CCP isotype associated with that panel; ●=Serum anti-CCP-positive for the anti-CCP isotype associated with that panel; ---- Cut-off level for anti-CCP positivity; — Median anti-CCP level.

Fourteen of 20 (70.0%) RA subjects were positive for anti-CCP-IgA and/or anti-CCP-IgG in sputum, which was significantly higher than in FDRs (70.0% vs. 25.4%, p<0.01). RA subjects also demonstrated higher rates of positivity for sputum anti-CCP-IgG compared to FDRs [14/20 (70.0%) vs. 11/67 (16.4%), p<0.01], whereas sputum anti-CCP-IgA positivity was not significantly higher in RA subjects as compared to FDRs [8/20 (40.0%) vs. 16/67 (23.9%), p=0.26]. In addition, sputum anti-CCP-IgA and anti-CCP-IgG levels were highest in RA (Figure 1, Panels A–B).

When comparing rates of autoantibody positivity within each group of RA and FDR subjects, in RA, that rates of sputum anti-CCP-IgG positivity were higher than anti-CCP-IgA [14/20 (70.0%) vs. 8/20 (40.0%), p=0.03] as compared to within FDR subjects where anti-CCP-IgA was not significantly more positive than anti-CCP-IgG [16/67 (23.9%) vs. 11/67 (16.4%), p=0.13].

Sputum and serum anti-CCP comparisons

To evaluate the relationship between sputum and serum anti-CCP positivity, we stratified FDRs based on their serum anti-CCP isotype status, where overall 12/67 (17.9%) FDRs and 20/20 (100%) RA subjects were positive for serum anti-CCP-IgA and/or anti-CCP-IgG.

There were 10 serum anti-CCP-IgA positive FDRs, of whom 5 (50%) were also sputum anti-CCP-IgA positive, and there were 57 serum anti-CCP-IgA negative FDRs of whom 11 (19%) were sputum anti-CCP-IgA positive (Supplemental Figure 1, Panel A). Furthermore, there were 4 serum anti-CCP-IgG positive FDRs of whom 1 (25%) was also sputum anti-CCP-IgG positive, and there were 63 serum anti-CCP-IgG negative FDRs of whom 10 (16%) were sputum anti-CCP-IgG positive (Supplemental Figure 1, Panel B). In the RA subjects, 13 were serum anti-CCP-IgA positive of whom 8 (62%) were also sputum anti-CCP-IgA positive, and there were 7 serum anti-CCP-IgA negative RA subjects of whom none were sputum anti-CCP-IgA positive (Supplemental Figure 1, Panel C). In addition, there were 19 serum IgG anti-CCP-positive RA patients, of whom 13 (68%) were also sputum anti-CCP-IgG positive, and there was 1 serum anti-CCP-IgG negative RA subject who was sputum anti-CCP-IgG positive (Supplemental Figure 1, Panel D).

To evaluate the potential for translocation of anti-CCP from serum to sputum, we compared the ratios of anti-CCP to total Ig levels for each isotype in sputum and serum with the rationale that a higher ratio at one site supports that that antibody is generated at that site (41, 42). In sputum anti-CCP positive FDRs, 11/14 (79%) had a higher anti-CCP-IgA/total-IgA ratio in sputum compared to serum and 9/10 (90%) FDR had a higher anti-CCP-IgG/total-IgG ratio in sputum supporting that the anti-CCP was generated in the lung in the majority of these subjects. In sputum anti-CCP positive RA subjects, 3/8 (38%) had a higher anti-CCP-IgA/total-IgA ratio in sputum and 11/13 (85%) had higher anti-CCP-IgG/total-IgG in sputum. In addition, median total IgA and IgG levels in sputum did not differ between FDR and RA subjects, but total sputum IgA in both groups was higher compared to Controls (Supplemental Figure 2).

Subject characteristics and sputum anti-CCP isotypes

Because smoking has been associated with increased risk for serum anti-CCP-positive RA and is relevant for sputum studies (17), we analyzed subjects stratified by smoking history. In FDRs, sputum anti-CCP-IgA but not anti-CCP-IgG positivity was significantly higher in ever-smokers compared to never-smokers (Figure 1, Panels C–D). A similar but non-significant association was seen in RA (Supplemental Figure 3).

In addition, there were no associations of sputum anti-CCP-IgA or anti-CCP-IgG positivity with sex, race, ≥1 SE allele, or history of lung disease (data not shown). In addition, correlation analysis did not identify a significant correlation between age and sputum anti-CCP isotype levels.

Similarly, in RA and Control subjects, there were no significant correlations or associations between sputum anti-CCP isotypes and age, sex, race, SE positivity, or history of lung disease (data not shown).

Sputum cell counts and sputum anti-CCP isotypes

The known predominant cell types in sputum are neutrophils and macrophages (35, 36), and as such we focused our analyses on these cell types. In FDRs, the median (IQR) for neutrophils was 12.3 (4.3–26.3) cells x104/mL and macrophages was 17.5 (8.2 -47.1) cells x104/mL. For RA subjects, the median (IQR) for neutrophils was 24.7 (6.5–44.0) cells x104/mL and for macrophages was 12.7 (4.6–27.2) cells x104/mL.

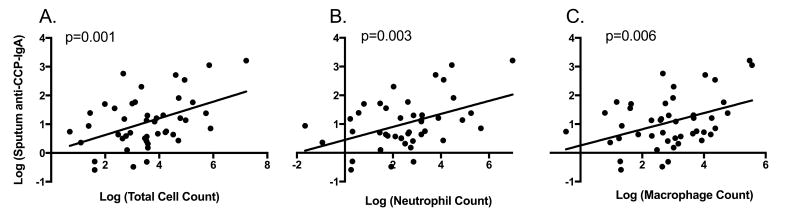

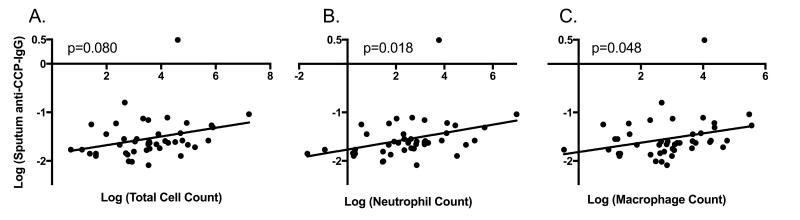

Using regression analyses, we evaluated the association of anti-CCP levels with signs of airway inflammation as measured by sputum total cell count (excluding squamous epithelial cells), and neutrophil and macrophage counts. In FDRs, sputum anti-CCP-IgA was significantly associated with total (t=3.5, p<0.01), neutrophil (t=3.2, p<0.01) and macrophage counts (t=2.9, p<0.01) (Figure 2). Similar associations within FDRs were demonstrated for sputum anti-CCP-IgG and total (t=1.8, p=0.08), neutrophil (t=2.5, p=0.02) and macrophage counts (t=2.0, p<0.05) (Figure 3). In RA subjects, sputum anti-CCP-IgA was significantly associated with total cell count (t=2.3, p=0.04), but no other significant associations were seen between sputum anti-CCP-IgA or anti-CCP-IgG levels and cell counts in RA subjects (data not shown).

Figure 2. Relationship between sputum anti-CCP-IgA levels and sputum cell counts in FDRs.

Log transformed levels of sputum anti-CCP-IgA are plotted along the Y-axis. Log transformed levels of the sputum total cell count (Panel A), total neutrophil count (Panel B) and total macrophage count (Panel C) are plotted along the X-axis. P-values are calculated using linear regression.

Figure 3. Relationship between sputum anti-CCP-IgG levels and sputum cell counts in FDRs.

Log transformed levels of sputum anti-CCP-IgG are plotted along the Y-axis. Log transformed levels of the sputum total cell count (Panel A), total neutrophil count (Panel B) and total macrophage count (Panel C) are plotted along the X-axis. P-values are calculated using linear regression.

Furthermore, sputum neutrophil and macrophage counts were higher in sputum anti-CCP isotype positive FDRs compared to sputum anti-CCP isotype negative healthy Controls [median (IQR) cells x104/mL; for neutrophils, 43.8 (7.6–85.5) vs. 9.2 (3.9–31.8), p=0.14; for macrophages, 56.9 (20.5–240.5) vs. 17.2 (6.7–41.5), p=0.01]. However, sputum levels of neutrophils and macrophages were similar between sputum anti-CCP isotype negative FDRs and Controls (p=0.69 and p=0.58 respectively).

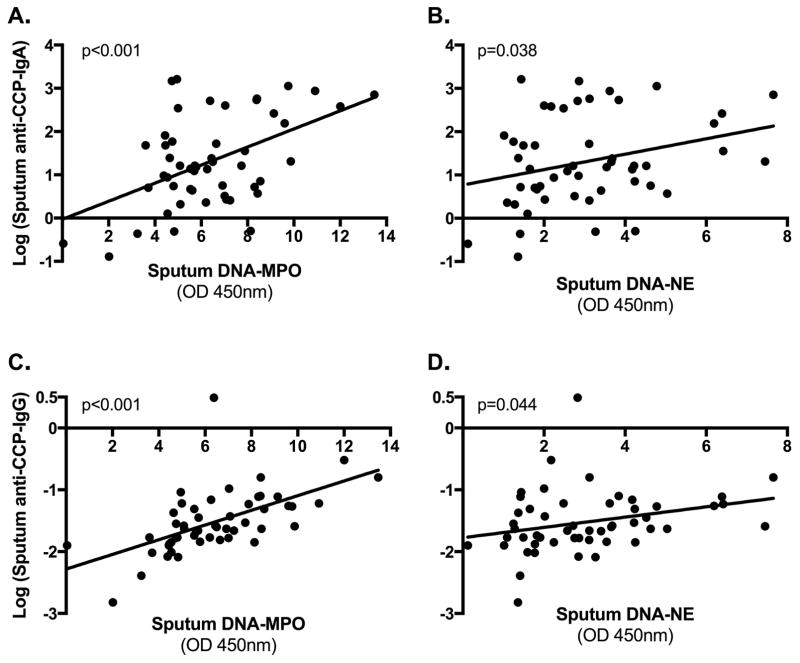

Sputum NET levels and sputum anti-CCP isotypes

We next studied the association between sputum levels of anti-CCP and NETs. Using log transformed anti-CCP levels, in FDRs, sputum levels of anti-CCP-IgA and anti-CCP-IgG were significantly associated with sputum NET levels measured by DNA-MPO and DNA-NE (Figure 4). In analyses adjusting for ever-smoking and citrulline level, in FDRs the association between sputum anti-CCP-IgA and NET levels remained significant: by DNA-MPO, t=3.75, p<0.01; and by DNA-NE, t=2.10, p=0.04. In particular, for every 1-unit increase in NET level as measured by DNA-MPO, there was a 1.20 increase in sputum anti-CCP-IgA (95% CI; 1.09–1.33) and a 1.13 increase in sputum anti-CCP-IgG (95% CI; 1.07–1.18). Similarly, for every 1-unit increase in NET level as measured by DNA-NE, there was a 1.17 increase in sputum anti-CCP-IgA (95% CI; 1.01–1.37) and a 1.09 increase in sputum anti-CCP-IgG (95% CI; 1.00–1.18). No significant associations were demonstrated between sputum anti-CCP-IgA or anti-CCP-IgG levels and NET levels in RA subjects (data not shown).

Figure 4. Associations of sputum anti-CCP isotypes and sputum neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) levels in FDRs.

Plotted along the Y-axis are sputum anti-CCP-IgA levels (log transformed, Panels A–B) and sputum anti-CCP-IgG levels (log transformed, Panels C–D) for FDRs. Plotted along the X-axis are sputum NET levels as measured by complexes of deoxyribonucleic acid and myeloperoxidase (DNA-MPO) (Panels A and C) as well as by complexes of DNA and neutrophil elastase (DNA-NE) (Panels B and D). P-values are calculated using linear regression.

Sputum citrulline levels and sputum anti-CCP isotypes

In FDRs there was a significant association between sputum citrulline and sputum anti-CCP-IgA levels (t=3.2, p<0.01), but not between citrulline and sputum anti-CCP-IgG (t=0.7, p=0.50). Sputum citrulline levels were higher in ever-smokers compared to never-smokers, but in analyses that were adjusted for ever-smoking, sputum anti-CCP-IgA remained significantly associated with total citrulline level (t=2.7, p<0.01). In RA subjects, there were no significant associations were seen between sputum anti-CCP-IgA or anti-CCP-IgG and total citrulline levels (data not shown).

Of note, as presented in Supplemental Figure 4, due to sample volume restrictions, a subset of 51 FDRs and 9 RA subjects had sputum volume available for testing of NET and citrulline levels. To ensure there was no selection bias in the subjects who had larger volumes of sputum, we compared FDR and RA subjects who did and did not undergo NET and citrulline testing. In these analyses, we found no significant difference in age, sex, race, SE positivity, history of ever-smoking, serum anti-CCP positivity or sputum anti-CCP positivity.

DISCUSSION

Similar to our prior work (43) but in an expanded cohort and newly discriminating isotype specific ACPA reactivity, we found that ACPA elevations in the lung/sputum as characterized by anti-CCP isotypes is prevalent in a portion of FDR (25%) and RA subjects (70%). Of particular interest, we also newly demonstrate sputum anti-CCP-IgA in sputum and determined that anti-CCP-IgA and anti-CCP-IgG are associated with increased sputum cell counts and NET remnants in FDRs.

Importantly, these findings provide support for the conclusion that sputum ACPA elevations are associated with local airway inflammation. We also provide the first evidence that NET formation is associated with ACPA in the lung, suggesting that NETosis may drive ACPA production locally in FDRs who are at an elevated risk of future RA.

The relationship between ACPA elevations and NET formation in FDRs is of particular interest for several reasons. Elevated NETosis has been associated with established RA, can expose citrullinated proteins to the immune system including RA-associated proteins such as citrullinated histone-H3, and can release PAD4 that could citrullinate other local proteins (24–26, 44). Although it is possible that NET formation could have been induced in our study during sputum collection or processing, this is less likely given that all samples underwent the same protocols, while elevated NET remnants were identified only in a subset. In addition, prior studies have applied immunostaining techniques that visually demonstrate the formation of NETs from sputum neutrophils (28, 29). Going forward it will be important to understand the mechanisms contributing to higher sputum NETosis levels in these FDRs. Specific questions to be addressed are whether neutrophils from FDRs are more likely to undergo NETosis compared to non-FDRs, and whether increased NETosis in the sputum can be generated by another source (e.g. microbiota, inflammatory cytokines, or ACPAs triggered by another mechanism). Furthermore, a recent study identified that microbial factors may impact neutrophil-related citrullination through pore-forming mechanisms (45); therefore, other mechanisms beyond NETosis by which neutrophils or other factors may contribute to mucosal citrullination need to be explored.

Notably, because we wanted to study factors associated with the earliest steps of ACPA formation and to enhance our ability to find RA-related autoimmunity, we focused on FDRs as a population that is known to be at elevated risk to develop ACPA (2, 3, 6). However, it is worth noting that we did not find associations between sputum ACPA isotypes and cell counts or NET levels in RA subjects. This lack of association could be due to the small number of RA subjects studied or their use of immunosuppressive medications. However, it could also be that the mechanisms that drive ACPA change during the evolution of disease or after the onset of synovitis in RA. For example, only after arthritis is present in RA has ACPA been identified in synovial tissues (42, 46). Going forward, this will need to be explored in prospective evaluation of the evolution of sputum and serum ACPA and other biomarkers in individuals who transition to classifiable RA.

Furthermore, citrullination in the lung has been associated with smoking and inflammation (16, 20). In this study, we demonstrated that sputum ACPA-IgA but not ACPA-IgG was associated with smoking and increased citrulline levels. Although the COLDER assay quantifies ureido groups that can include citrullinated as well as homocitrullined peptides, this finding suggests that perhaps ACPA-IgA is more likely than ACPA-IgG to be formed in response to non-specific inflammation in the lung, and that other factors may be required to drive ACPA-IgG formation. This finding also highlights that different ACPA isotypes may play different roles in the pathogenesis of RA. Prior studies demonstrate that serum ACPA-IgG positivity is higher in patients with established RA, compared to unaffected FDRs who were more often serum ACPA-IgA positive (2, 3). In our study, we found similar associations in serum as well as sputum. Although prospective studies are needed, this finding does raise the question as to whether the development of ACPA-IgG is an important step in the transition from preclinical RA to clinically-apparent arthritis. We also found that a subset of FDRs demonstrated sputum ACPA isotype positivity in the absence of serum ACPA positivity. This finding further validates our prior work that the lung may be a site where ACPAs originate, and indeed we have demonstrated in subset analyses that sputum anti-CCP-IgA does not appear to be from a salivary source (see Supplement). However, we also found some FDRs who were serum ACPA positive in the absence of sputum ACPA positivity suggesting that in some FDRs ACPA may have originated at a site outside of the lung. This highlights the importance of comprehensively examining additional mucosal surfaces as potential sites of initiation of RA-related autoimmunity.

While FDRs are at increased risk for developing RA-related autoimmunity, it is clear that the number of FDRs demonstrating sputum ACPA positivity exceeds the number that statistically will develop classifiable RA. This suggests that local ACPA formation may be necessary but not sufficient to progress to systemic RA-related autoimmunity and eventually arthritis. In addition, sputum ACPAs could have been translocated from the serum in FDRs. We believe this is unlikely because many FDRs were only ACPA positive in sputum; in addition, anti-CCP/Ig ratios were higher in sputum compared to serum for the majority of FDRs. Furthermore, the primary goal in the selection of our Control population was to set cut-off levels for sputum ACPA positivity. With that, our Controls were younger than FDR or RA subjects. Because there was not an association of age with ACPA level, this difference was unlikely to influence establishment of a positive cut-off level. However, additional longitudinal studies of the prevalence and evolution of sputum ACPA in individuals who transition to classifiable RA as well as carefully matched controls will be needed to better understand these issues, and specifically to validate the diagnostic accuracy of sputum ACPA isotypes for ultimate progression to classifiable RA, as well as to explore the mechanisms by-which ACPA generation at a mucosal surface may occur in broader populations, perhaps as a natural response to mucosal inflammation. These latter studies are especially important if ultimately detection of sputum autoantibodies becomes a method by which to identify subjects who may be at-risk of future RA.

In addition, emerging data suggest that antibody reactivity to ‘native’ or non-citrullinated/arginine peptides may play a role in the early development of autoimmunity in RA (19, 47, 48). Older studies have demonstrated that in non-RA populations, serum ACPA reactivity can be non-specific or cross-reactive with arginine peptides (49). While our study only tested antibody reactivity to the citrullinated CCP3 plate substrate, based on these other studies, it would be expected that a portion of our subjects could have antibodies to native proteins. Future studies are needed to address whether antibodies to native proteins precede development of ACPAs in FDRs, whether FDRs demonstrate simultaneous generation of antibodies to citrullinated and non-citrullinated targets, or whether sputum ACPAs in FDRs are less specific and cross-react with non-citrullinated antigens.

In conclusion, ACPA isotypes as measured by anti-CCP are present in the sputum of a portion of FDRs and subjects with early classifiable disease. In FDRs, sputum ACPA is associated with elevated cell counts and NET remnants supporting that the lung plays an important role in the early phases of RA-related autoimmunity. Longitudinal and additional mechanism-based studies in broader populations are needed to further investigate this relationship.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grants: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers AR066712, AI101990, HD057022, TR001082, AI103023] and the Intramural Research Program (NIAMS; project ZIAAR041199); Rheumatology Research Foundation [Disease Targeted Research Initiative Programs, Scientist Development Award]; and the Walter S. and Lucienne Driskill Foundation. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Michael Mahler is an employee of Inova Diagnostics.

References

- 1.Svard A, Kastbom A, Reckner-Olsson A, Skogh T. Presence and utility of IgA-class antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides in early rheumatoid arthritis: the Swedish TIRA project. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(4):R75. doi: 10.1186/ar2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barra L, Scinocca M, Saunders S, Bhayana R, Rohekar S, Racape M, et al. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies in unaffected first-degree relatives of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(6):1439–47. doi: 10.1002/art.37911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arlestig L, Mullazehi M, Kokkonen H, Rocklov J, Ronnelid J, Dahlqvist SR. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides of IgG, IgA and IgM isotype and rheumatoid factor of IgM and IgA isotype are increased in unaffected members of multicase rheumatoid arthritis families from northern Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(6):825–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kokkonen H, Mullazehi M, Berglin E, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Ronnelid J, et al. Antibodies of IgG, IgA and IgM isotypes against cyclic citrullinated peptide precede the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(1):R13. doi: 10.1186/ar3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demoruelle MK, Weisman MH, Simonian PL, Lynch DA, Sachs PB, Pedraza IF, et al. Brief report: airways abnormalities and rheumatoid arthritis-related autoantibodies in subjects without arthritis: early injury or initiating site of autoimmunity? Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):1756–61. doi: 10.1002/art.34344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demoruelle MK, Parish MC, Derber LA, Kolfenbach JR, Hughes-Austin JM, Weisman MH, et al. Performance of anti-cyclic citrullinated Peptide assays differs in subjects at increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis and subjects with established disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(9):2243–52. doi: 10.1002/art.38017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deane KD, O’Donnell CI, Hueber W, Majka DS, Lazar AA, Derber LA, et al. The number of elevated cytokines and chemokines in preclinical seropositive rheumatoid arthritis predicts time to diagnosis in an age-dependent manner. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(11):3161–72. doi: 10.1002/art.27638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Stenlund H, et al. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(10):2741–9. doi: 10.1002/art.11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokolove J, Bromberg R, Deane KD, Lahey LJ, Derber LA, Chandra PE, et al. Autoantibody epitope spreading in the pre-clinical phase predicts progression to rheumatoid arthritis. PloS one. 2012;7(5):e35296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van de Stadt LA, Witte BI, Bos WH, van Schaardenburg D. A prediction rule for the development of arthritis in seropositive arthralgia patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1920–6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van de Stadt LA, Bos WH, Meursinge Reynders M, Wieringa H, Turkstra F, van der Laken CJ, et al. The value of ultrasonography in predicting arthritis in auto-antibody positive arthralgia patients: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(3):R98. doi: 10.1186/ar3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Hair MJ, van de Sande MG, Ramwadhdoebe TH, Hansson M, Landewe R, van der Leij C, et al. Features of the synovium of individuals at risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: implications for understanding preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(3):513–22. doi: 10.1002/art.38273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Sande MG, de Hair MJ, van der Leij C, Klarenbeek PL, Bos WH, Smith MD, et al. Different stages of rheumatoid arthritis: features of the synovium in the preclinical phase. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):772–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.139527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willis VC, Demoruelle MK, Derber LA, Chartier-Logan CJ, Parish MC, Pedraza IF, et al. Sputum autoantibodies in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis and subjects at risk of future clinically apparent disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(10):2545–54. doi: 10.1002/art.38066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynisdottir G, Karimi R, Joshua V, Olsen H, Hensvold AH, Harju A, et al. Structural changes and antibody enrichment in the lungs are early features of anti-citrullinated protein antibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(1):31–9. doi: 10.1002/art.38201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lugli EB, Correia RE, Fischer R, Lundberg K, Bracke KR, Montgomery AB, et al. Expression of citrulline and homocitrulline residues in the lungs of non-smokers and smokers: implications for autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:9. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0520-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klareskog L, Stolt P, Lundberg K, Kallberg H, Bengtsson C, Grunewald J, et al. A new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: smoking may trigger HLA-DR (shared epitope)-restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullination. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):38–46. doi: 10.1002/art.21575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer A, Solomon JJ, du Bois RM, Deane KD, Olson AL, Fernandez-Perez ER, et al. Lung disease with anti-CCP antibodies but not rheumatoid arthritis or connective tissue disease. Respir Med. 2012;106(7):1040–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen KM, de Smit MJ, Brouwer E, de Kok FA, Kraan J, Altenburg J, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated autoantibodies in non-rheumatoid arthritis patients with mucosal inflammation: a case-control study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:174. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0690-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makrygiannakis D, Hermansson M, Ulfgren AK, Nicholas AP, Zendman AJ, Eklund A, et al. Smoking increases peptidylarginine deiminase 2 enzyme expression in human lungs and increases citrullination in BAL cells. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(10):1488–92. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.075192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(3):677–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Li M, Stadler S, Correll S, Li P, Wang D, et al. Histone hypercitrullination mediates chromatin decondensation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. J Cell Biol. 2009;184(2):205–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khandpur R, Carmona-Rivera C, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Gizinski A, Yalavarthi S, Knight JS, et al. NETs are a source of citrullinated autoantigens and stimulate inflammatory responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(178):178ra40. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spengler J, Lugonja B, Ytterberg AJ, Zubarev RA, Creese AJ, Pearson MJ, et al. Release of Active Peptidyl Arginine Deiminases by Neutrophils Can Explain Production of Extracellular Citrullinated Autoantigens in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Fluid. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(12):3135–45. doi: 10.1002/art.39313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sur Chowdhury C, Giaglis S, Walker UA, Buser A, Hahn S, Hasler P. Enhanced neutrophil extracellular trap generation in rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of underlying signal transduction pathways and potential diagnostic utility. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(3):R122. doi: 10.1186/ar4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen F, Marwitz S, Holz O, Kirsten A, Bahmer T, Waschki B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap formation and extracellular DNA in sputum of stable COPD patients. Respir Med. 2015;109(10):1360–2. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright TK, Gibson PG, Simpson JL, McDonald VM, Wood LG, Baines KJ. Neutrophil extracellular traps are associated with inflammation in chronic airway disease. Respirology. 2016;21(3):467–75. doi: 10.1111/resp.12730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Obermayer A, Stoiber W, Krautgartner WD, Klappacher M, Kofler B, Steinbacher P, et al. New aspects on the structure of neutrophil extracellular traps from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and in vitro generation. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolfenbach JR, Deane KD, Derber LA, O’Donnell C, Weisman MH, Buckner JH, et al. A prospective approach to investigating the natural history of preclinical rheumatoid arthritis (RA) using first-degree relatives of probands with RA. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(12):1735–42. doi: 10.1002/art.24833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deane KD, Striebich CC, Goldstein BL, Derber LA, Parish MC, Feser ML, et al. Identification of undiagnosed inflammatory arthritis in a community health fair screen. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(12):1642–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frisell T, Holmqvist M, Kallberg H, Klareskog L, Alfredsson L, Askling J. Familial risks and heritability of rheumatoid arthritis: role of rheumatoid factor/anti-citrullinated protein antibody status, number and type of affected relatives, sex, and age. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(11):2773–82. doi: 10.1002/art.38097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sparks JA, Chen CY, Hiraki LT, Malspeis S, Costenbader KH, Karlson EW. Contributions of familial rheumatoid arthritis or lupus and environmental factors to risk of rheumatoid arthritis in women: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(10):1438–46. doi: 10.1002/acr.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, 3rd, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(9):1580–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gershman NH, Wong HH, Liu JT, Mahlmeister MJ, Fahy JV. Comparison of two methods of collecting induced sputum in asthmatic subjects. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(12):2448–53. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09122448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.in ’t Veen JC, de Gouw HW, Smits HH, Sont JK, Hiemstra PS, Sterk PJ, et al. Repeatability of cellular and soluble markers of inflammation in induced sputum from patients with asthma. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(12):2441–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09122441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lood C, Blanco LP, Purmalek MM, Carmona-Rivera C, De Ravin SS, Smith CK, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps enriched in oxidized mitochondrial DNA are interferogenic and contribute to lupus-like disease. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):146–53. doi: 10.1038/nm.4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kearney PL, Bhatia M, Jones NG, Yuan L, Glascock MC, Catchings KL, et al. Kinetic characterization of protein arginine deiminase 4: a transcriptional corepressor implicated in the onset and progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Biochemistry. 2005;44(31):10570–82. doi: 10.1021/bi050292m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knuckley B, Causey CP, Jones JE, Bhatia M, Dreyton CJ, Osborne TC, et al. Substrate specificity and kinetic studies of PADs 1, 3, and 4 identify potent and selective inhibitors of protein arginine deiminase 3. Biochemistry. 2010;49(23):4852–63. doi: 10.1021/bi100363t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knipp M, Vasak M. A colorimetric 96-well microtiter plate assay for the determination of enzymatically formed citrulline. Anal Biochem. 2000;286(2):257–64. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masson-Bessiere C, Sebbag M, Durieux JJ, Nogueira L, Vincent C, Girbal-Neuhauser E, et al. In the rheumatoid pannus, anti-filaggrin autoantibodies are produced by local plasma cells and constitute a higher proportion of IgG than in synovial fluid and serum. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;119(3):544–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snir O, Widhe M, Hermansson M, von Spee C, Lindberg J, Hensen S, et al. Antibodies to several citrullinated antigens are enriched in the joints of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(1):44–52. doi: 10.1002/art.25036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willis VC, Demoruelle MK, Derber LA, Chartier-Logan CJ, Parish MC, Pedraza IF, et al. Sputum autoantibodies in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis and subjects at risk of future clinically apparent disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(10):2545–54. doi: 10.1002/art.38066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sohn DH, Rhodes C, Onuma K, Zhao X, Sharpe O, Gazitt T, et al. Local Joint inflammation and histone citrullination in a murine model of the transition from preclinical autoimmunity to inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(11):2877–87. doi: 10.1002/art.39283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Konig MF, Abusleme L, Reinholdt J, Palmer RJ, Teles RP, Sampson K, et al. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans-induced hypercitrullination links periodontal infection to autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(369):369ra176. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaj1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Humby F, Bombardieri M, Manzo A, Kelly S, Blades MC, Kirkham B, et al. Ectopic lymphoid structures support ongoing production of class-switched autoantibodies in rheumatoid synovium. PLoS Med. 2009;6(1):e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0060001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brink M, Hansson M, Ronnelid J, Klareskog L, Rantapaa Dahlqvist S. The autoantibody repertoire in periodontitis: a role in the induction of autoimmunity to citrullinated proteins in rheumatoid arthritis? Antibodies against uncitrullinated peptides seem to occur prior to the antibodies to the corresponding citrullinated peptides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):e46. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konig MF, Giles JT, Nigrovic PA, Andrade F. Antibodies to native and citrullinated RA33 (hnRNP A2/B1) challenge citrullination as the inciting principle underlying loss of tolerance in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(11):2022–8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kakumanu P, Yamagata H, Sobel ES, Reeves WH, Chan EK, Satoh M. Patients with pulmonary tuberculosis are frequently positive for anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, but their sera also react with unmodified arginine-containing peptide. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(6):1576–81. doi: 10.1002/art.23514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Svard A, Kastbom A, Sommarin Y, Skogh T. Salivary IgA antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides (CCP) in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunobiology. 2013;218(2):232–7. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.