Abstract

Background

Current estimates for the direct costs of a single episode of care for periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) after THA are approximately USD 100,000. These estimates do not account for the costs of failed treatments and do not include indirect costs such as lost wages.

Questions/purposes

The goal of this study was to estimate the long-term economic effect to society (direct and indirect costs) of a PJI after THA treated with contemporary standards of care in a hypothetical patient of working age (three scenarios, age 55, 60, and 65 years).

Methods

We created a state-transition Markov model with health states defined by surgical treatment options including irrigation and débridement with modular exchange, single-stage revision, and two-stage revision. Reoperation rates attributable to septic and aseptic failure modes and indirect and direct costs were calculated estimates garnered via multiple systematic reviews of peer-reviewed orthopaedic and infectious disease journals and Medicare reimbursement data. We conducted an analysis over a hypothetical patient’s lifetime from the societal perspective with costs discounted by 3% annually. We conducted sensitivity analysis to delineate the effects of uncertainty attributable to input variables.

Results

The model found a base case cost of USD 390,806 per 65-year-old patient with an infected THA. One-way sensitivity analysis gives a range of USD 389,307 (65-year-old with a 3% reinfection rate) and USD 474,004 (55-year-old with a 12% reinfection rate). Indirect costs such as lost wages make up a considerable portion of the costs and increase considerably as age at the time of infection decreases.

Conclusions

The results of this study show that the overall treatment of a periprosthetic infection after a THA is markedly more expensive to society than previously estimated when accounting for the considerable failure rates of current treatment options and including indirect costs. These overall costs, combined with a large projected increase in THAs and a steady state of septic failures, should be taken into account when considering the total cost of THA. Further research is needed to adequately compare the clinical and economic effectiveness of alternative treatment pathways.

Level of Evidence

Level II, economic and decision analysis.

Introduction

When a THA is unsuccessful, the costs to the patient and to society are great [16, 18, 22, 42, 53]. Revision THAs generally are much more complicated, involving longer operative times, greater bone and blood loss, longer hospitalization, and are performed on patients who generally are older and have more medical comorbidities [15, 16]. When a revision arthroplasty is performed for aseptic failure, it often can be completed with one additional surgical procedure and hospitalization. However, when a THA fails owing to a periprosthetic joint infection (PJI), even if revision surgery can be limited to a single surgical procedure such as an irrigation and débridement or a single-stage exchange, the revision surgery and subsequent treatments are associated with extremely high direct medical costs consisting of long-term antibiotic treatment, multiple physician appointments, extended inpatient stays, increased physical therapy, and rehabilitation hospital admissions [4, 17, 21, 23, 30, 37, 41, 49, 53–57, 60, 63, 72, 80, 84, 85, 92, 98]. Moreover, the indirect costs such as time lost from work and a negative effect on quality of life and emotional wellbeing are considerable [13]. Because more THAs are being performed on younger patients, particularly those of working age, these indirect costs for septic failures become magnified.

The current estimate for the direct episodic cost of a two-stage revision THA for periprosthetic infection is USD 100,000 [18, 58, 59]. This is approximately four times the cost of a primary THA, estimated to be approximately USD 21,470 [18]. To our knowledge, the longer-term economic implications of PJIs after THA have not been assessed. Previous studies have evaluated direct costs of a single episode of care (ie, the direct costs of a two-stage revision or of an irrigation and débridement), but have not been able to evaluate longer-term costs [16, 18, 34, 40, 41, 53, 59]. Some of these studies also do not consider that current treatments for a PJI after THA are not 100% effective; even the gold standard, two-stage revision, has only a 70% to 90% likelihood of achieving infection control [1, 5]. Indirect costs associated with multiple surgical procedures such as lost wages also have not been evaluated. Although one decision analysis found single-exchange arthroplasty favorable to a two-staged approach regarding mortality rates and patient outcomes, it did not address any costs associated with these treatments [98].

The goal of our study was to estimate the long-term economic effect to society (direct and indirect costs) of a PJI after THA treated with contemporary standards of care in a hypothetical patient of working age (three scenarios, age 55, 60, and 65 years).

Materials and Methods

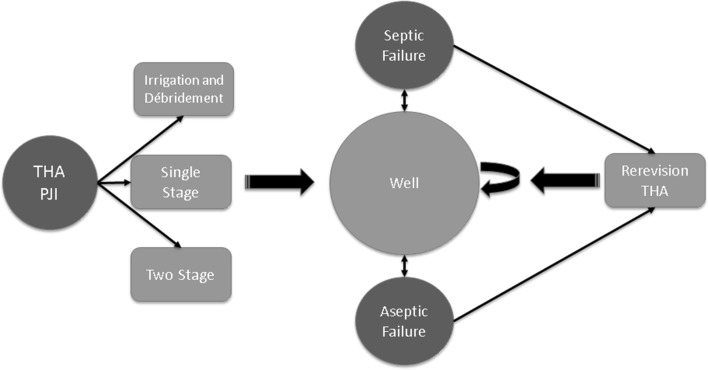

TreeAge Pro 2009 (TreeAge Software, Williamstown, MA, USA) was used to create a Markov state-transition model of a hypothetical patient of working age with a PJI after a THA who was undergoing treatment with three possible surgical strategies including irrigation and débridement, single-stage exchange, or two-stage exchange (Fig. 1). The process models patients’ discrete and mutually exclusive health states at different times along with any associated health costs and/or earnings. The algorithm accounts for a fixed percentage of patients undergoing one of these three initial treatments based on available studies of current practices (Table 1) [30, 57, 60, 63, 84]. Defined and unique rates for treatment failures (septic and aseptic) and age-specific mortality rates during the first year and then subsequent years are used to predict transitions between different health states (Table 1). Patients who are modeled as having a successful treatment enter a well state with a fixed annual rate of repeat septic failure beyond the first year. Patients for whom treatment failed owing to sepsis will undergo a second procedure (two-stage exchange). This model accommodates for any patient to have two revisions where fixed components are removed and the hip subsequently is reconstructed (ie, one irrigation and débridement followed by two two-stage exchanges, one single-stage and one two-stage, or two two-stage exchanges). Should a patient experience two failed fixed component exchanges, the model assumes that the patient will not undergo further surgery, but will enter a nonworking, suboptimal health state. Patients with failure owing to aseptic modes (ie, loosening or dislocation) are modeled to undergo revision surgery for aseptic failure with specific and unique revision rates and costs for aseptic revisions. The model also accounts for incidence and cost estimates associated with common perioperative medical complications such as pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, and myocardial infarction [2, 8, 14, 27, 44, 51, 62, 66, 69, 70, 77, 78, 88, 89].

Fig. 1.

The flow chart shows the different health states of the Markov state-transition decision model and the various pathways along which patients may transition with time. The curved arrows represent the patient remaining in the same health state for the next analytic cycle. The absorbing states of failed repeat two-stage exchange and death are not shown.

Table 1.

Model input variables

| Variable | Rate | |

|---|---|---|

| Rate of irrigation and débridement as an initial strategy | 67% | |

| Rate of one-stage as an initial strategy | 10% | |

| Rate of two-stage as an initial strategy | 23% | |

| Failure rate for irrigation and débridement during the first year | 30% | |

| Failure rate for irrigation and débridement after the first year | 56.7% | |

| Failure rate for single-stage during the first year | 9.8% | |

| Failure rate for single-stage after the first year | 12.4% | |

| Failure rate for two-stage in the first year | 4.27% | |

| Failure rate for two-stage after the first year | 8.6% | |

| Rate of aseptic revision after infection (loosening, dislocation, fracture) | 5.6%r | |

| Failure rate of aseptic revision THA | 13.1% | |

| Rate and cost of medical complications after revision THA | Rate | Cost |

| Mortality | 1.16% | |

| Deep vein thromboembolism | 0.82% | $9287 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.48% | $10,411 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.47% | $13,100 |

| Pneumonia | 0.93% | $6666 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.56% | $896 |

| Stroke | 0.29% | $15,300 |

| Transfusion | 68.4% | $3071 |

| Overall medical complication rate (not including transfusion or death) | 4.55% | |

| Weighted average cost of complications | $2409 | |

| Other costs | ||

| Cost of aseptic revision THA | $35,997 (direct hospital costs) | |

| Treatment cost for the first year after infection | 1st 90 Days | Remainder of 1st year (add $5386) |

| Inpatient rehabilitation (10.2%) | $80,491 | $85,877 |

| Skilled nursing facility (20.2%) | $48,955 | $54,341 |

| Home health care (25.2%) | $37,370 | $42,756 |

| Home with outpatient physical therapy (42.1%) | $31,558 | $36,944 |

| Weighted average for the first year postinpatient costs | $46,189 | |

| Treatment cost after the first year | $187 | |

| Cost of nonsurgical treatment for infection (long-term antibiotics) | Annual cost approximately $7500 | |

Each health state is assigned a net cost for one analytic cycle (defined as 1 year), and transition probabilities determine the likelihood that a patient will either transition to the next health state or remain in the current one. The base case models patients at 65, 60, and 55 years old at the time of the initial revision procedure to estimate a typical patient of working age who might elect to have a THA. The simulation runs until all patients have died (based on US life expectancy data tables and systematic review) [3, 8, 27, 62, 65, 66, 69, 70, 77, 78, 88, 89]. We conducted one-way sensitivity analysis to determine how cost estimates would be affected by different rates of THA reinfection (during the first year of treatment and beyond the first year) based on the variability in published studies.

The health state transitions, probabilities and associated direct costs, and medical complication rates and costs were estimated via a systematic review of the literature performed in November and December 2016 via PubMed for: (1) outcomes and failure rates for septic THA treatments: irrigation and débridement (Table 2), single-stage revision (Table 3); and two-stage revision (Table 4); (2) direct medical costs for revision THA attributable to PJI; (3) failure rates and costs for aseptic revision THA; (4) perioperative complication rates and costs after septic and aseptic revision THA; and, (5) postdischarge costs after revision THA. The search terms “periprosthetic joint infection and total hip arthroplasty” OR “periprosthetic joint infection and total hip arthroplasty and cost” OR “revision total hip arthroplasty and aseptic” OR “revision total hip arthroplasty and complications” OR “revision total hip arthroplasty and complications and cost” OR “total joint arthroplasty and post discharge costs” yielded 1041 separate articles, 937 of which were excluded because they did not pertain to the specific diagnosis or treatments of interest, the study included less than 15 patients, the study had a mean followup less than 2 years, or was a duplication. Bibliographies of selected articles subsequently were hand-searched to ensure the inclusion of all pertinent studies [4, 5, 9–11, 19–21, 23, 24, 26, 30, 31, 33, 37–39, 45–47, 49, 52–56, 60, 63, 64, 67, 68, 72, 75, 82, 83, 86, 87, 90, 92, 94, 96, 98–100].

Table 2.

Data from studies regarding irrigation and débridement of the hip

| Study | Year | Sample size | Mean followup (months) | Rate of medical complications | Mortality rate related to surgery or infection | Annualized reinfection rate | Overall reinfection rate | Failure rates for other reasons | Overall infection eradication success rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azzam et al. [4] | 2010 | 51 | 68 | 25%† | 3% | 11.6% | 66% | NM | 44% |

| Odum et al. [72] | 2011 | 53 | NM | NM | 8% | 69%* | 69% | NM | 31% |

| Byren et al. [23] | 2009 | 52 | 27 | NM | NM | 11% | 18% | NM | 82% |

| Lora-Tamayo et al. [63] | 2013 | 146 | NM | NM | 7% | 38.5%* | 45% | NM | 55% |

| Cobo et al. [30] | 2011 | 69 | 24 | NM | 3.6% | 21.5% | 43% | NM | 57% |

| Buller et al. [21] | 2012 | 62 | 34 | NM | NM | 40.6%* | 48.2% | NM | 52% |

| Koyonos et al. [54] | 2011 | 60 | 54 | NM | NM | 14.5% | 65% | NM | 35% |

| El Helou et al. [37] | 2010 | 40 | 24 | NM | 12.5% | 32% | 32% | NM | 68% |

| Tornero et al. [92] | 2012 | 39 | 46 | NM | NM | 6.3% | 24% | NM | 76% |

| Romano et al. [85] | 2014 | 796 | 48 | NM | NM | 44.9%* | 55% | NM | 45% |

| Crockarell et al. [31] | 1998 | 42 | 76 | 11.9% | 7% | 28%* | 79% | 4.7% | 21% |

| Brandt et al. [19] | 1997 | 30 | 48 | NM | NM | 54%* | 69% | NM | 31% |

| Meehan et al. [68] | 2003 | 19 | 34 | NM | NM | 11%* | 11% | NM | 89% |

| Totals | 1459 | 42.8 | 24.7% | 56.7% | 4.7% | 43.3% |

Weighted annual reinfection rate 30.1%; * rate stated explicitly in study; †packed red blood cell transfusion rate; NM = not mentioned.

Table 3.

Data from studies of single-stage revision of the hip

| Study | Year | Sample size | Mean followup (months) | Rate of medical complications | Mortality rate related to surgery or infection | Annualized reinfection rate | Overall reinfection rate | Failure rates for other reasons | Overall infection eradication success rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buchholz et al. [20] | 1981 | 640 | 52 | NM | 2.7% | 16% | 23% | 3.3% | 76.8% |

| Wroblewski [99] | 1986 | 102 | 38 | NM | NM | 3% | 9% | NM | 91% |

| Hope et al. [46] | 1989 | 72 | NM | NM | NM | NM | 13% | 3% | 87% |

| Loty et al. [64] | 1992 | 90 | 47 | NM | 1.1% | 9% | 10% | 7.8% | 79% |

| Elson [38] | 1994 | 235 | NM | NM | NM | NM | 14% | NM | 86% |

| Raut et al. [83] | 1994 | 57 | 88 | 12.3% | 7% | 2% | 14% | 7% | 86% |

| Raut et al. [82] | 1996 | 15 | 120 | NM | NM | 1% | 7% | 6.7% | 87% |

| Ure et al. [94] | 1998 | 20 | 120 | NM | 0% | 0% | 0% | 10% | 100% |

| Callaghan et al. [24] | 1999 | 24 | 120 | NM | NM | 1% | 8.3% | 4.2% | 92% |

| Jackson & Schmalzried [49] | 2000 | 1299 | 58 | NM | 0.8% | 5% | 17% | NM | 83% |

| Vielpeau & Lortat-Jacob [96] | 2002 | 127 | 36 | NM | NM | 12% | 16% | NM | 84% |

| Rudelli et al. [86] | 2008 | 32 | 103 | NM | NM | 1% | 6.2% | 3.1% | 94% |

| Wolf et al. [98] | 2011 | 576 | NM | NM | 0.5% | 12%* | 28% | 4.3% | 72% |

| Beswick et al. [10] | 2012 | 1225 | 24 | NM | NM | 5% | 9% | NM | 91% |

| Lange et al. [60] | 2012 | 375 | NM | NM | NM | NM | 13% | NM | 87% |

| Zeller et al. [100] | 2014 | 157 | 41.6 | NM | 1.3% | 3% | 5% | 5.7% | 88% |

| Kunutsor et al. [56] | 2015 | 2536 | 35 | NM | NM | 8% | 8% | NM | 92% |

| Totals | 7582 | 67.8 | 5.1% | 12.4% | 5.5% | 87.5% |

Weighted annual reinfection rate 9.8%; * rate stated explicitly in study; NM = not mentioned.

Table 4.

Data from studies of two-stage revision of the hip

| Study | Year | Sample size | Mean followup (months) | Rate of medical complications | Mortality rate related to surgery or infection | Annualized reinfection rate | Overall reinfection rate | Failure rates for other reasons | Overall infection eradication success rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D’Angelo et al. [33] | 2011 | 28 | 53 | NM | NM | 1% | 4% | 7.1% | 96% |

| Babis et al. [5] | 2015 | 31 | 30 | NM | NM | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Berend et al. [9] | 2013 | 205 | 53 | 1% | 4% | 6% | 24% | 5% | 76% |

| Biring et al. [11] | 2009 | 99 | 144 | NM | NM | 1% | 11% | 9.1% | 89% |

| Chen et al. [26] | 2009 | 48 | 66 | NM | NM | 1% | 4% | 8.3 | 96% |

| Engesaeter et al. [39] | 2011 | 283 | 24 | NM | NM | 4% | 8% | 13% | 92% |

| Hofmann et al. [45] | 2005 | 27 | 76 | 7.4% | 0% | 1% | 6% | 3.7% | 94% |

| Hsieh et al. [47] | 2004 | 42 | 55.2 | NM | NM | 2% | 7% | NM | 93% |

| Klouche et al. [52] | 2012 | 46 | 24 | NM | NM | 2% | 3% | NM | 97% |

| Masri et al. [67] | 2007 | 29 | 24 | NM | 6.9% | 7% | 14% | 6.9% | 86% |

| Oussedik et al. [75] | 2010 | 39 | 60 | NM | NM | 1% | 5% | NM | 95% |

| Sanzen et al. [87] | 1988 | 102 | 24 | 4.5% | 1.8% | 13% | 25% | 10.9% | 75% |

| Lange et al. [60] | 2012 | 929 | NM | NM | NM | NM | 10% | 10% | 90% |

| Shen et al. [90] | 2014 | 33 | 60 | NM | NM | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Totals | 1941 | 53.3 | 4.3% | 3.2% | 3.0 | 8.6% | 6.7% | 91.4% |

Weighted annual reinfection rate 4.27%; NM = not mentioned.

Direct cost input variables based on the above systematic reviews and Medicare reimbursement data were adjusted to 2016 US dollars using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index [6, 7, 12, 15, 17, 18, 25, 28, 29, 32, 35, 36, 41, 43, 48, 53, 61, 71, 73, 74, 79–81, 91, 95, 101]. Costs for surgery and nonsurgical complications for each procedure were accounted for, and nonsurgical costs related to outpatient treatments and followup care for the first year and beyond were considered (Table 5) [17, 18, 53, 59, 76, 80, 85]. Indirect costs in the form of lost wages were calculated using an assumption of 3 months out of work per surgical intervention for the average US worker until age 70 [93]. We estimated indirect costs by multiplying the US gross domestic product per capita by the proportion of the year spent recovering [93]. We ignored indirect costs after age 70 years because we assumed that patients had retired. The annual costs for patient monitoring, including physician visit and radiographs, were obtained via systematic review and estimated using the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule [29]. The outcome of interest was the sum of direct medical costs and indirect costs in the form of lost wages. All costs were discounted by 3% annually [93]. Our analysis conformed to the guidelines reported by Weinstein et al. [97].

Table 5.

Cost data

| Procedure/source data | Converted to 2016 USD |

|---|---|

| Two-stage revision | |

| Hospital costs | |

| Parvizi et al. [76] | 132,921.03 |

| Klouche et al. [53] | 85,568.24 |

| Romano et al. [85] | 99,079.44 |

| Kurz et al. [59] | 105,463.55 |

| Bozic et al. [16] | 135,554.94 |

| Average | 111,717.44 |

| Outpatient charges | |

| Bozic et al. [16] | 63,530.24 |

| One-stage revision | |

| Klouche et al. [53] | 49,243.89 |

| Parvizi et al. [76] | 67,781.07 |

| Average | 58,512.48 |

| Irrigation and débridement | |

| Peel et al. [80] | 55,593.41 |

| Bozic et al [17] | 47,599.44 |

| Parvizi et al. [76] | 73,506.26 |

| Average | 58,899.70 |

Results

Based on the input parameters of this model, the overall lifetime cost of treatment of a septic THA is USD 390,806 per patient aged 65 years with an infected THA. One-way sensitivity analysis (Table 6) showed that as infection rates increase, even by small increments in percentage, the overall cost increases accordingly. In patients at age 65 years, a 3% reinfection rate had a modeled cost of USD 389,307, whereas a 12% reinfection rate had a modeled cost of USD 412,091.

Table 6.

Results and sensitivity analysis of total costs of two-stage revision

| Age at revision and rate of failure | Base failure rate | Theoretical year-one failure rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-year failure rate | 4.27% | 3% | 6% | 8% | 10% | 12% |

| 65 year-old | 390,806 | 389,307 | 392,869 | 395,283 | 397,729 | 400,208 |

| 60 year-old | 415,183 | 413,363 | 417,693 | 420,638 | 423,630 | 426,669 |

| 55 year-old | 441,986 | 439,786 | 445,015 | 448,562 | 452,160 | 455,806 |

| Annualized failure rate after first year | 8.6% | 3% | 6% | 8% | 10% | 12% |

| 65 year-old | 390,806 | 335,512 | 369,163 | 386,299 | 400,373 | 412,091 |

| 60 year-old | 415,183 | 348,745 | 389,194 | 409,760 | 426,731 | 440,981 |

| 55 year-old | 441,986 | 361,779 | 410,321 | 435,335 | 456,236 | 474,004 |

All costs listed in 2016 USD.

Indirect costs such as lost wages made up an increasingly considerable portion of the costs as the age of patients decreased. At the base infection rate of 4.27%, the modeled cost of a 65-year-old individual undergoing revision was USD 390,806. When decreasing the age by 5 years to 60 years (ie, 5 more years of income potential), this increases to USD 415,183, and when 55 years, this increases further to USD 441,986 (Table 6).

Discussion

Numerous studies have shown that the direct costs of treating a PJI after THA are shockingly high, with current cost estimates for two-stage revision arthroplasty exceeding USD 100,000, or approximately four times as much as a primary THA [18, 53, 59, 76, 85]. The current study shows that these previous estimates are relatively low because they do not account for the high failure rate of current treatments nor do they account for indirect costs. Even with a relatively low reinfection rate of 3% (lower than most published rates of failure for irrigation and débridement, single-stage, or two-stage revision), the overall costs are modeled to approach just less than USD 400,000, approximately four times previous estimates for a two-stage revision, and greater than seven times the published costs of an irrigation and débridement or a single-stage exchange [53, 76, 80]. When factoring in costs such as lost productivity, the costs become even higher. Modeled costs of a 55-year-old hypothetical patient who requires two-stage revision arthroplasty increase to almost half a million USD.

Our study has several limitations. The model was kept relatively simple with only 11 distinct, mutually exclusive health states. The idea that a patient would transition neatly from a state of infection to well after revision, reinfection, or death is an oversimplification that does not take into account the many other health states, such as noninfected but painful revision, or failure for other reasons such as aseptic loosening or periprosthetic fracture. Additionally, the analytic cycle timing was arbitrarily set for 1 year which is per convention, but may be an oversimplification with many reinfections occurring sooner than 1 year. Another arbitrary cutoff was the assumption that all patients would be retired by the age of 70 years. While average retirement ages have varied over the years, the most recent normal retirement age set by Social Security was 67 years. Finally, while the three most common treatments of septic THA were included in the model and every attempt was made to incorporate the typical treatment patterns and expected reinfection rates based on published studies, the model does not distinguish between an acute infection or chronic infection, nor does it take into account important variables such as type of organism, timing of symptoms, surgical approach, or other possible treatments such as resection arthroplasty, amputation, or long-term antibiotic suppression. Although it would be ideal to model each possible failure scenario with its prevalence and associated costs, the sheer complexity of the nearly infinite permutations makes it difficult to achieve this successfully. However, although our inability to model every possible health state, including every possible medical complication, may be a weakness of the study, we attempted to capture the most-common clinical scenarios with the sensitivity analysis serving to limit uncertainty attributable to these limitations.

Another major limitation of this study is that it does not directly compare the cost of different treatments available. While the majority of US studies quotes a two-stage revision as the gold standard for treatment, there is an increasing number of studies supporting single-stage revision owing to decreased morbidity and cost, and increased function and outcome in terms of quality-adjusted-life-years [50, 52, 53, 94, 98]. Although a true cost comparison would be helpful to payers and perhaps clinicians, we thought it was not possible to do a commensurate analysis given the relatively little amount of cost data available regarding single-stage exchange arthroplasty [53, 76]. We were able to find only two studies that adequately provided direct costs of a single-stage exchange, and those sources actually found single-stage exchange costs to be less than those for irrigation and débridement [53, 76]. Additionally, while single-stage exchange is increasingly used, we found that it is used only approximately 10% of the time as the initial treatment strategy for PJI [30, 56, 60, 63, 84]. Moreover, the use of single-stage exchange often is predicated on the susceptibility of the infection organism, a factor that we chose not to incorporate in this model. A direct cost comparison of single- and two-stage exchange would not be accurately represented by this model [50, 57, 60].

Because the precise estimation of the true cost in healthcare is difficult, the cost estimates in many models such as this one are limited. Direct costs of hospitalization and medical complications were estimated from published studies and garnered from Medicare data, and indirect costs were based solely on lost productivity from work [18, 28, 29, 53, 59, 66, 76, 80, 85, 93]. Other posthospitalization costs such as outpatient physical therapy were not accounted for, nor was lost productivity of loved ones taking care of patients who had undergone treatment.

This model illustrates the substantial costs of revision THA for septic failure and the economic implications of these costs on the individual and society. The majority of previously published cost estimates accounted for only direct hospital charges [18, 53, 59, 76, 80, 85], and few included posthospitalization costs and indirect costs such as lost productivity. Although it is known that revision THA for PJI is extremely expensive, this model estimates that even in the base case scenario, with relatively low treatment failure rates, the cost is at least three times as much as previously estimated. Fisman et al. [41], and Wolf et al. [98] found that less-invasive (and still less-effective) irrigation and débridement and single-stage exchange were more cost-effective in terms of overall quality of life years compared with two-stage revision, however further studies are needed to clarify overall clinical and economic outcomes of single- versus two-stage exchange. A multicenter, randomized clinical trial is necessary to compare the two treatments, and clarification of hospital costs (not charges) and outpatient costs is needed to more precisely estimate true costs of this increasingly profound problem. Our study puts into perspective how profound an economic problem PJI after THA continues to be, and highlights the need for policymakers and researchers to combine forces to do the necessary research to accurately determine which treatments are most effective clinically and economically.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he, or a member of his immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

A comment to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11999-017-5365-y.

References

- 1.Aggarwal VK, Rasouli MR, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection: current concept. Indian J Orthop. 2013;47:10–17. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.106884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfonso DT, Toussaint RJ, Alfonso BD, Strauss EJ, Steiger DT, Di Cesare PE. Nonsurgical complications after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2006;35:503–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias E. United States Life Tables, 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azzam KA, Seeley M, Ghanem E, Austin MS, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Irrigation and debridement in the management of prosthetic joint infection: traditional indications revisited. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babis GC, Sakellariou VI, Pantos PG, Sasalos GG, Stavropoulos NA. Two-stage revision protocol in multidrug resistant periprosthetic infection following total hip arthroplasty using a long interval between stages. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:1602–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrack RL. Economics of revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;319:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrack RL, Sawhney J, Hsu J, Cofield RH. Cost analysis of revision total hip arthroplasty: a 5-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;369:175–178. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199912000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belmont PJ, Jr, Goodman GP, Hamilton W, Waterman BR, Bader JO, Schoenfeld AJ. Morbidity and mortality in the thirty-day period following total hip arthroplasty: risk factors and incidence. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:2025–2030. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berend KR, Lombardi AV, Jr, Morris MJ, Bergeson AG, Adams JB, Sneller MA. Two-stage treatment of hip periprosthetic joint infection is associated with a high rate of infection control but high mortality. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:510–518. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2595-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beswick AD, Elvers KT, Smith AJ, Gooberman-Hill R, Lovering A, Blom AW. What is the evidence base to guide surgical treatment of infected hip prostheses? Systematic review of longitudinal studies in unselected patients. BMC Med. 2012;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biring GS, Kostamo T, Garbuz DS, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Two-stage revision arthroplasty of the hip for infection using an interim articulated Prostalac hip spacer: a 10- to 15-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1431–1437. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B11.22026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanchette CM, Wang PF, Joshi AV, Kruse P, Asmussen M, Saunders W. Resource utilization and costs of blood management services associated with knee and hip surgeries in US hospitals. Adv Ther. 2006;23:54–67. doi: 10.1007/BF02850347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boettner F, Cross MB, Nam D, Kluthe T, Schulte M, Goetze C. Functional and emotional results differ after aseptic vs septic revision hip arthroplasty. HSS J. 2011;7:235–238. doi: 10.1007/s11420-011-9211-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohl DD, Samuel AM, Basques BA, Della Valle CJ, Levine BR, Grauer JN. How much do adverse event rates differ between primary and revision total joint arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bozic KJ, Durbhakula S, Berry DJ, Naessens JM, Rappaport K, Cisternas M, Saleh KJ, Rubash HE. Differences in patient and procedure characteristics and hospital resource use in primary and revision total joint arthroplasty: a multicenter study. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bozic KJ, Katz P, Cisternas M, Ono L, Ries MD, Showstack J. Hospital resource utilization for primary and revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:570–576. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200503000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Vail TP, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:128–133. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozic KJ, Ries MD. The impact of infection after total hip arthroplasty on hospital and surgeon resource utilization. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1746–1751. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brandt CM, Sistrunk WW, Duffy MC, Hanssen AD, Steckelberg JM, Ilstrup DM, Osmon DR. Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infection treated with debridement and prosthesis retention. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:914–919. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchholz HW, Elson RA, Engelbrecht E, Lodenkamper H, Rottger J, Siegel A. Management of deep infection of total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63:342–353. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198163030-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buller LT, Sabry FY, Easton RW, Klika AK, Barsoum WK. The preoperative prediction of success following irrigation and debridement with polyethylene exchange for hip and knee prosthetic joint infections. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:857–864.e1-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Burns AW, Bourne RB. Economics of revision total hip arthroplasty. Curr Orthop. 2006;20:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cuor.2006.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byren I, Bejon P, Atkins BL, Angus B, Masters S, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Berendt A. One hundred and twelve infected arthroplasties treated with ‘DAIR’ (debridement, antibiotics and implant retention): antibiotic duration and outcome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:1264–1271. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Callaghan JJ, Katz RP, Johnston RC. One-stage revision surgery of the infected hip: a minimum 10-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;369:139–143. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caprini JA, Botteman MF, Stephens JM, Nadipelli V, Ewing MM, Brandt S, Pashos CL, Cohen AT. Economic burden of long-term complications of deep vein thrombosis after total hip replacement surgery in the United States. Value Health. 2003;6:59–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2003.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen WS, Fu TH, Wang JW. Two-stage reimplantation of infected hip arthroplasties. Chang Gung Med J. 2009;32:188–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi HR, Beecher B, Bedair H. Mortality after septic versus aseptic revision total hip arthroplasty: a matched-cohort study. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:56–58. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CMS.gov. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Inpatient Charge Data FY 2011. 2011. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Inpatient2011.html. Accessed October 28, 2014.

- 29.CMS.gov. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician Fee Schedule 2012. 2012. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/index.html. Accessed October 28, 2014.

- 30.Cobo J, Miguel LG, Euba G, Rodriguez D, Garcia-Lechuz JM, Riera M, Falgueras L, Palomino J, Benito N, del Toro MD, Pigrau C, Ariza J. Early prosthetic joint infection: outcomes with debridement and implant retention followed by antibiotic therapy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1632–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crockarell JR, Hanssen AD, Osmon DR, Morrey BF. Treatment of infection with debridement and retention of the components following hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1306–1313. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199809000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crowe JF, Sculco TP, Kahn B. Revision total hip arthroplasty: hospital cost and reimbursement analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;413:175–182. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000072469.32680.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Angelo F, Negri L, Binda T, Zatti G, Cherubino P. The use of a preformed spacer in two-stage revision of infected hip arthroplasties. Musculoskelet Surg. 2011;95:115–120. doi: 10.1007/s12306-011-0128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1422–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:943–953. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Edelsberg J, Ollendorf D, Oster G. Venous thromboembolism following major orthopedic surgery: review of epidemiology and economics. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(suppl 2):S4–13. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.suppl_2.S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El Helou OC, Berbari EF, Lahr BD, Eckel-Passow JE, Razonable RR, Sia IG, Virk A, Walker RC, Steckelberg JM, Wilson WR, Hanssen AD, Osmon DR. Efficacy and safety of rifampin containing regimen for staphylococcal prosthetic joint infections treated with debridement and retention. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:961–967. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0952-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elson R. One-stage exchange in the treatment of the infected total hip arthroplasty. Semin Arthroplasty. 1994;5:137–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engesaeter LB, Dale H, Schrama JC, Hallan G, Lie SA. Surgical procedures in the treatment of 784 infected THAs reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:530–537. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.623572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez-Fairen M, Torres A, Menzie A, Hernandez-Vaquero D, Fernandez-Carreira JM, Murcia-Mazon A, Guerado E, Merzthal L. Economical analysis on prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment of periprosthetic infections. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:227–242. doi: 10.2174/1874325001307010227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fisman DN, Reilly DT, Karchmer AW, Goldie SJ. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 2 management strategies for infected total hip arthroplasty in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:419–430. doi: 10.1086/318502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furnes A, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Vollset SE. The economic impact of failures in total hip replacement surgery: 28,997 cases from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, 1987–1993. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67(2):115–121. doi: 10.3109/17453679608994653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garrido-Gomez J, Arrabal-Polo MA, Giron-Prieto MS, Cabello-Salas J, Torres-Barroso J, Parra-Ruiz J. Descriptive analysis of the economic costs of periprosthetic joint infection of the knee for the public health system of Andalusia. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1057–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.George J, Sikora M, Masch J, Farias-Kovac M, Klika AK, Higuera CA. Infection is not a risk factor for perioperative and postoperative blood loss and transfusion in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(214–219):e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hofmann AA, Goldberg TD, Tanner AM, Cook TM. Ten-year experience using an articulating antibiotic cement hip spacer for the treatment of chronically infected total hip. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:874–879. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hope PG, Kristinsson KG, Norman P, Elson RA. Deep infection of cemented total hip arthroplasties caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71:851–855. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B5.2584258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsieh PH, Shih CH, Chang YH, Lee MS, Shih HN, Yang WE. Two-stage revision hip arthroplasty for infection: comparison between the interim use of antibiotic-loaded cement beads and a spacer prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1989–1997. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iorio R, Healy WL, Richards JA. Comparison of the hospital cost of primary and revision total knee arthroplasty after cost containment. Orthopedics. 1999;22:195–199. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19990201-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson WO, Schmalzried TP. Limited role of direct exchange arthroplasty in the treatment of infected total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;381:101–105. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200012000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiranek WA, Waligora AC, Hess SR, Golladay GL. Surgical treatment of prosthetic joint infections of the hip and knee: changing paradigms? J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:912–918. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kinkel S, Kessler S, Mattes T, Reichel H, Kafer W. [Predictive factors of perioperative morbidity in revision total hip arthroplasty][in German] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2007;145:91–96. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-960504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klouche S, Leonard P, Zeller V, Lhotellier L, Graff W, Leclerc P, Mamoudy P, Sariali E. Infected total hip arthroplasty revision: one- or two-stage procedure? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klouche S, Sariali E, Mamoudy P. Total hip arthroplasty revision due to infection: a cost analysis approach. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koyonos L, Zmistowski B, Della Valle CJ, Parvizi J. Infection control rate of irrigation and debridement for periprosthetic joint infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:3043–3048. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1910-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuiper JW, Willink RT, Moojen DJ, van den Bekerom MP, Colen S. Treatment of acute periprosthetic infections with prosthesis retention: review of current concepts. World J Orthop. 2014;5:667–676. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kunutsor SK, Whitehouse MR, Blom AW, Beswick AD, Team I. Re-infection outcomes following one- and two-stage surgical revision of infected hip prosthesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kunutsor SK, Whitehouse MR, Webb J, Toms A, Stockley I, Taylor A, Jones S, Wilson M, Burston B, Board T, Whittaker JP, Blom AW, Beswick AD. Re-infection outcomes following one- and two-stage surgical revision of infected hip prosthesis in unselected patients: protocol for a systematic review and an individual participant data meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2015;4:58. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0044-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, Zhao K, Parvizi J. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier JK, Parvizi J. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):61–65.e1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Lange J, Troelsen A, Thomsen RW, Soballe K. Chronic infections in hip arthroplasties: comparing risk of reinfection following one-stage and two-stage revision: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:57–73. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S29025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lavernia CJ, Drakeford MK, Tsao AK, Gittelsohn A, Krackow KA, Hungerford DS. Revision and primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a cost analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;311:136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liodakis E, Bergeron SG, Zukor DJ, Huk OL, Epure LM, Antoniou J. Perioperative complications and length of stay after revision total hip and knee arthroplasties: an analysis of the NSQIP database. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:1868–1871. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lora-Tamayo J, Murillo O, Iribarren JA, Soriano A, Sanchez-Somolinos M, Baraia-Etxaburu JM, Rico A, Palomino J, Rodriguez-Pardo D, Horcajada JP, Benito N, Bahamonde A, Granados A, del Toro MD, Cobo J, Riera M, Ramos A, Jover-Saenz A, Ariza J; REIPI Group for the Study of Prosthetic Infection. A large multicenter study of methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infections managed with implant retention. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:182–194. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Loty B, Postel M, Evrard J, Matron P, Courpied JP, Kerboull M, Tomeno B. [One stage revision of infected total hip replacements with replacement of bone loss by allografts. Study of 90 cases of which 46 used bone allografts][in French] Int Orthop. 1992;16:330–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00189615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mahomed NN, Barrett JA, Katz JN, Phillips CB, Losina E, Lew RA, Guadagnoli E, Harris WH, Poss R, Baron JA. Rates and outcomes of primary and revision total hip replacement in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:27–32. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mantilla CB, Horlocker TT, Schroeder DR, Berry DJ, Brown DL. Risk factors for clinically relevant pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis in patients undergoing primary hip or knee arthroplasty. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:552–560; discussion 5A. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Masri BA, Panagiotopoulos KP, Greidanus NV, Garbuz DS, Duncan CP. Cementless two-stage exchange arthroplasty for infection after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.02.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meehan AM, Osmon DR, Duffy MC, Hanssen AD, Keating MR. Outcome of penicillin-susceptible streptococcal prosthetic joint infection treated with debridement and retention of the prosthesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:845–849. doi: 10.1086/368182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Memtsoudis SG, Della Valle AG, Besculides MC, Esposito M, Koulouvaris P, Salvati EA. Risk factors for perioperative mortality after lower extremity arthroplasty: a population-based study of 6,901,324 patient discharges. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller KA, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Johnston RC. Early postoperative mortality following total hip arthroplasty in a community setting: a single surgeon experience. Iowa Orthop J. 2003;23:36–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nichols CI, Vose JG. Clinical outcomes and costs within 90 days of primary or revision total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(1400–1406):e3. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Odum SM, Fehring TK, Lombardi AV, Zmistowski BM, Brown NM, Luna JT, Fehring KA, Hansen EN; Periprosthetic Infection Consortium. Irrigation and debridement for periprosthetic infections: does the organism matter? J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(6 suppl):114–118. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Ollendorf DA, Vera-Llonch M, Oster G. Cost of venous thromboembolism following major orthopedic surgery in hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59:1750–1754. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.18.1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oster G, Ollendorf DA, Vera-Llonch M, Hagiwara M, Berger A, Edelsberg J. Economic consequences of venous thromboembolism following major orthopedic surgery. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:377–382. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oussedik SI, Dodd MB, Haddad FS. Outcomes of revision total hip replacement for infection after grading according to a standard protocol. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1222–1226. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.23663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parvizi J, Pawasarat IM, Azzam KA, Joshi A, Hansen EN, Bozic KJ. Periprosthetic joint infection: the economic impact of methicillin-resistant infections. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(6 suppl):103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Parvizi J, Pour AE, Keshavarzi NR, D’Apuzzo M, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ. Revision total hip arthroplasty in octogenarians: a case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2612–2618. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Sorensen HT, Emmeluth C, Overgaard S, Johnsen SP. The risk of venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, major bleeding and death in patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement: a 15-year retrospective cohort study of routine clinical practice. Bone Joint J. 2014;96:479–485. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B4.33209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peel TN, Cheng AC, Liew D, Buising KL, Lisik J, Carroll KA, Choong PF, Dowsey MM. Direct hospital cost determinants following hip and knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67:782–790. doi: 10.1002/acr.22523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peel TN, Dowsey MM, Buising KL, Liew D, Choong PF. Cost analysis of debridement and retention for management of prosthetic joint infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:181–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ramos NL, Wang EL, Karia RJ, Hutzler LH, Lajam CM, Bosco JA. Correlation between physician specific discharge costs, LOS, and 30-day readmission rates: an analysis of 1,831 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1717–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Raut VV, Orth MS, Orth MC, Siney PD, Wroblewski BM. One stage revision arthroplasty of the hip for deep gram negative infection. Int Orthop. 1996;20:12–14. doi: 10.1007/s002640050019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Raut VV, Siney PD, Wroblewski BM. One-stage revision of infected total hip replacements with discharging sinuses. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:721–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rodriguez D, Pigrau C, Euba G, Cobo J, Garcia-Lechuz J, Palomino J, Riera M, Del Toro MD, Granados A, Ariza X, Group R. Acute haematogenous prosthetic joint infection: prospective evaluation of medical and surgical management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 85.Romano C, Logoluso N, Drago L, Peccati A, Romano D. Role for irrigation and debridement in periprosthetic infections. J Knee Surg. 2014;27:267–272. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1373736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rudelli S, Uip D, Honda E, Lima AL. One-stage revision of infected total hip arthroplasty with bone graft. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:1165–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sanzen L, Carlsson AS, Josefsson G, Lindberg LT. Revision operations on infected total hip arthroplasties: two- to nine-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;229:165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schwartz BE, Piponov HI, Helder CW, Mayers WF, Gonzalez MH. Revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States: national trends and in-hospital outcomes. Int Orthop. 2016;40:1793–1802. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shahi A, Tan TL, Chen AF, Maltenfort MG, Parvizi J. In-hospital mortality in patients with periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(948–952):e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shen B, Huang Q, Yang J, Zhou ZK, Kang PD, Pei FX. Extensively coated non-modular stem used in two-stage revision for infected total hip arthroplasty: mid-term to long-term follow-up. Orthop Surg. 2014;6:103–109. doi: 10.1111/os.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Taylor GJ, Mikell FL, Moses HW, Dove JT, Katholi RE, Malik SA, Markwell SJ, Korsmeyer C, Schneider JA, Wellons HA. Determinants of hospital charges for coronary artery bypass surgery: the economic consequences of postoperative complications. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:309–313. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90293-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tornero E, Garcia-Oltra E, Garcia-Ramiro S, Martinez-Pastor JC, Bosch J, Climent C, Morata L, Camacho P, Mensa J, Soriano A. Prosthetic joint infections due to Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci. Int J Artif Organs. 2012;35:884–892. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/cpi. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- 94.Ure KJ, Amstutz HC, Nasser S, Schmalzried TP. Direct-exchange arthroplasty for the treatment of infection after total hip replacement: an average ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:961–968. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199807000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vekeman F, LaMori JC, Laliberte F, Nutescu E, Duh MS, Bookhart BK, Schein J, Dea K, Olson WH, Lefebvre P. Risks and cost burden of venous thromboembolism and bleeding for patients undergoing total hip or knee replacement in a managed-care population. J Med Econ. 2011;14:324–334. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.578698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vielpeau C, Lortat-Jacob A. [Management of the infected hip prostheses][in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2002;88:159–216. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Kamlet MS, Russell LB. Recommendations of the Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. 1996;276:1253–1258. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540150055031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wolf CF, Gu NY, Doctor JN, Manner PA, Leopold SS. Comparison of one and two-stage revision of total hip arthroplasty complicated by infection: a Markov expected-utility decision analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:631–639. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wroblewski BM. One-stage revision of infected cemented total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;211:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zeller V, Lhotellier L, Marmor S, Leclerc P, Krain A, Graff W, Ducroquet F, Biau D, Leonard P, Desplaces N, Mamoudy P. One-stage exchange arthroplasty for chronic periprosthetic hip infection: results of a large prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e1. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, Franz C, Song P, Yamin CK, Keohane C, Denham CR, Bates DW. Health care-associated infections: a meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:2039–2046. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]