Abstract

Background and Objectives

Although several multicenter registries have evaluated percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedures in Korea, those databases have been limited by non-standardized data collection and lack of uniform reporting methods. We aimed to collect and report data from a standardized database to analyze PCI procedures throughout the country.

Materials and Methods

Both clinical and procedural data, as well as clinical outcomes data during hospital stay, were collected based on case report forms that used a standard set of 54 data elements. This report is based on 2014 Korean PCI registry cohort data.

Results

A total of 92 hospitals offered data on 44967 PCI procedures. The median age was 66.0 interquartile range 57.0-74.0 years, and 70.3% were men. Thirty-eight percent of patients presented with acute myocardial infarction and one-third of all PCI procedures were performed in an urgent or emergency setting. Non-invasive stress tests were performed in 13.9% of cases, while coronary computed tomography angiography was used in 13.7% of cases prior to PCI. Radial artery access was used in 56.1% of all PCI procedures. Devices that used PCI included drug-eluting stent, plain old balloon angioplasty, drug-eluting balloon, and bare-metal stent (around 91%, 19%, 6%, and 1% of all procedures, respectively). The incidences of in-hospital death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and stroke were 2.3%, 1.6%, and 0.2%, respectively.

Conclusion

These data may provide an overview of the current PCI practices and in-hospital outcomes in Korea and could be used as a foundation for developing treatment guidelines and nationwide clinical research.

Keywords: Percutaneous coronary intervention, Registry

Introduction

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has emerged as an important modality to treat coronary artery disease (CAD). As research improves pharmacology and clinical approaches for patient treatment, more complex CADs are being successfully treated with PCI and clinical outcomes are consistently improving. PCI can now be performed in most patients that require revascularization and it is also offered to subjects that have a high operative risk.1)

Guideline-based strategies and monitoring of PCI procedures are strongly recommended to improve in-hospital and long-term clinical outcomes of patients that undergo PCI.2),3),4),5) Specifically, performance measures for PCI and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) were established to guide physicians with approaches for these interventions.6),7),8)

Although several multicenter registries have evaluated PCI procedures in Korea,9),10),11),12),13) no nationwide contemporary PCI registries have been collected with standardized collection forms and unified reporting methods. The Korean Society of Cardiology (KSC) and Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology (KSIC) established the Korean percutaneous coronary intervention (K-PCI) registry to collect and report results in a standardized database for PCI case analysis throughout the country. The purpose of this study was to construct baseline data standards to set-up treatment guidelines that reflect relevant clinical situations and to facilitate clinical research for cardiologists that treat CAD in Korea.

Materials and Methods

Participation and data definitions

The K-PCI registry final protocol was created in the task force team meeting and the K-PCI registry governing committee conference, it was designed for enrolling participants with respect to clinical diagnosis information, procedural data, and by considering major complications after PCI procedures performed to treat ischemic heart disease. The hospitals that could perform PCI were asked to participate and 92 hospitals voluntarily took part in this registry. Demographic characteristics, clinical history, procedural information and PCI complications that occurred before hospital discharge were collected retrospectively using case report forms (CRFs) comprised of a standard set of 54 data elements. When multiple interventions were performed in a subject, individual procedures were considered as single cases and were entered in the database. All variables corresponded with written definitions in the CRF dictionary (K-PCI registry 2014 CRF v1.4., Supplementary Table 1) in the online-only Data Supplement) to standardize the data, and were provided by using common specifications with question and answer cases for participants.

This study was approved by the local institutional review board (IRB) at each participating site. The written consent document was waived in participating centers, because of the retrospective nature of the study, with no clinical follow-up. Data were collected using a web-based reporting system.

Data collection and management

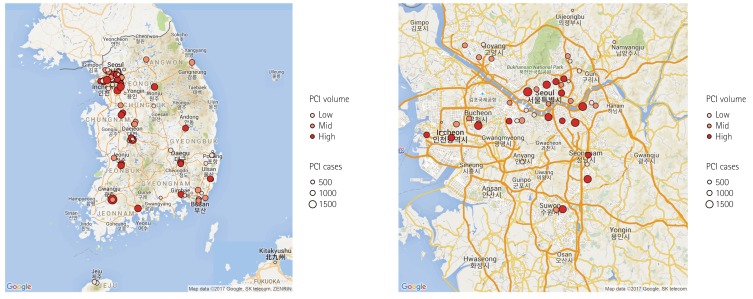

This report represents PCI data of the participating hospitals from January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2014. The K-PCI registry governing committee centrally managed the web-based registered study data. After the K-PCI registry was approved by the IRBs, demographic, procedural, and in-hospital outcomes data for 44967 PCI cases from 92 hospitals were collected. About half (45.7%) of the PCI centers were located in the capital area and high-volume facilities that performed more than 781 PCI procedures annually were concentrated in metropolitan areas, including Seoul (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Geographic distribution of PCI facilities participating in the K-PCI registry. Ninety-two hospitals submitted data for 44967 PCI cases. High-volume facilities were concentrated in Seoul and metropolitan areas. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, K-PCI: Korean percutaneous coronary intervention.

The K-PCI data management and inspection program determined whether collected data were accurate and complete and the CRF variables were refined based on the program results. The K-PCI registry governing committee periodically monitored the enrollment status and shared the results with participating hospitals via newsletters, the committee also performed data management quality verification through the query process.

Statistical analysis

Discrete data for demographic, clinical, procedural and outcome variables were presented as numbers and percentages and compared using Chi-square tests. Continuous variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) unless otherwise specified, and were compared using the Student's t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, where applicable. All p values were 2-tailed, and a p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using R version 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study populations

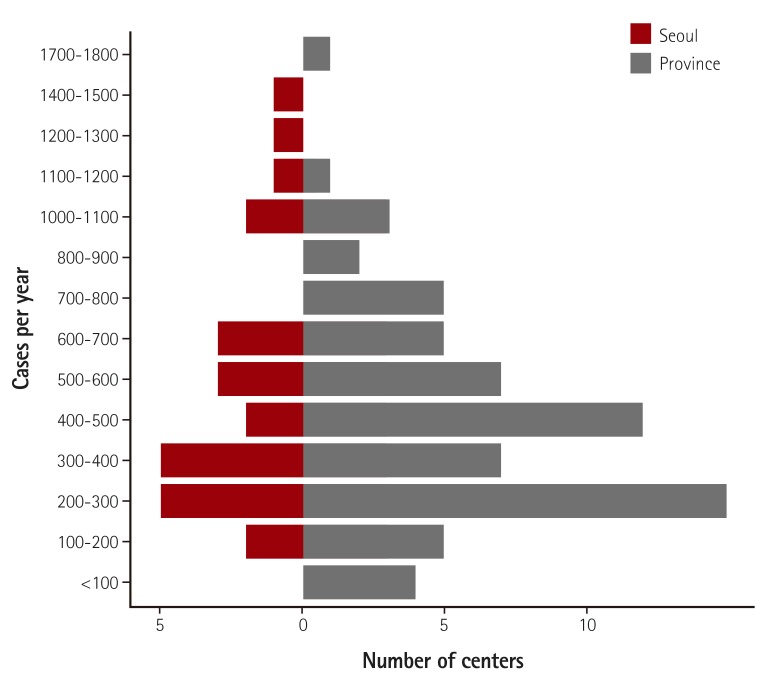

A total of 92 hospitals submitted data on 44967 PCI procedures performed from January through December 2014. The data presented in this report provide a contemporary assessment of PCI, as performed in Korea during the collection period, and represent important aspects of coronary interventions, including use of diagnostic support tools and procedural devices, as well as clinical outcomes before hospital discharge. Among the hospitals included in the K-PCI registry, 62% performed 500 or fewer PCI procedures and 11% performed more than 1000 PCIs during the collection period. Twelve hospitals (13%) performed 200 or fewer PCIs for one year and these hospitals accounted for 3.2% of all PCI procedures (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Distribution of facilities with different PCI volume. Sixty-two percent of the included hospitals performed 500 or fewer PCI procedures and 11% performed more than 1000 PCIs during the collection period. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

Clinical characteristics and presentation

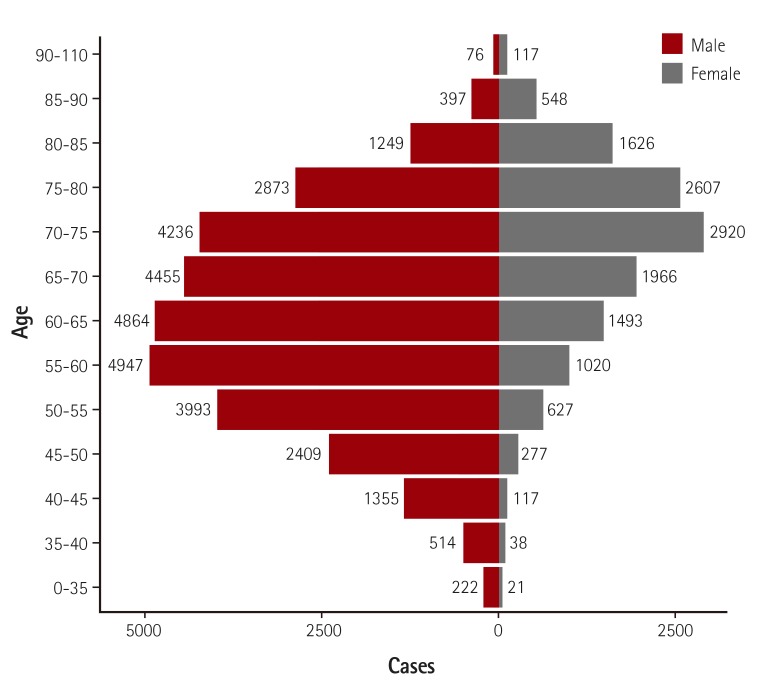

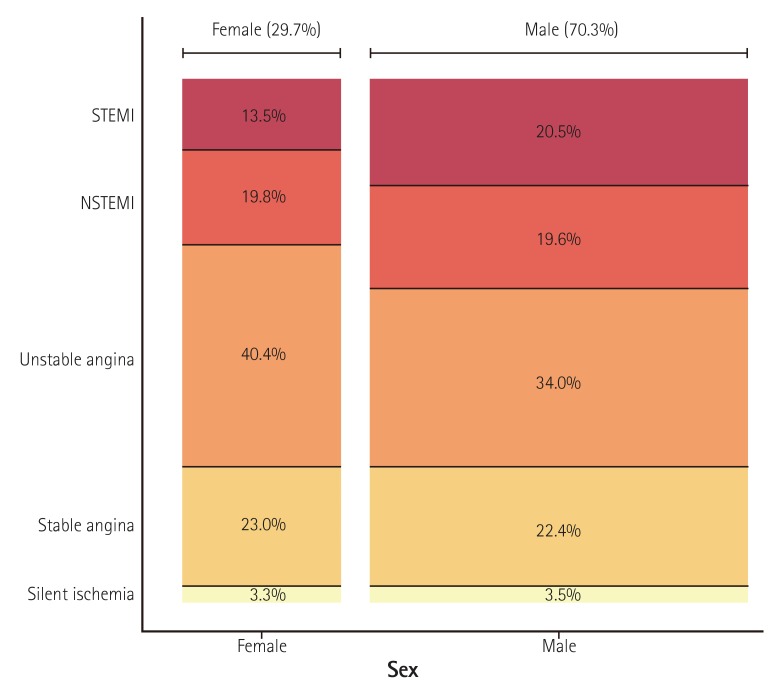

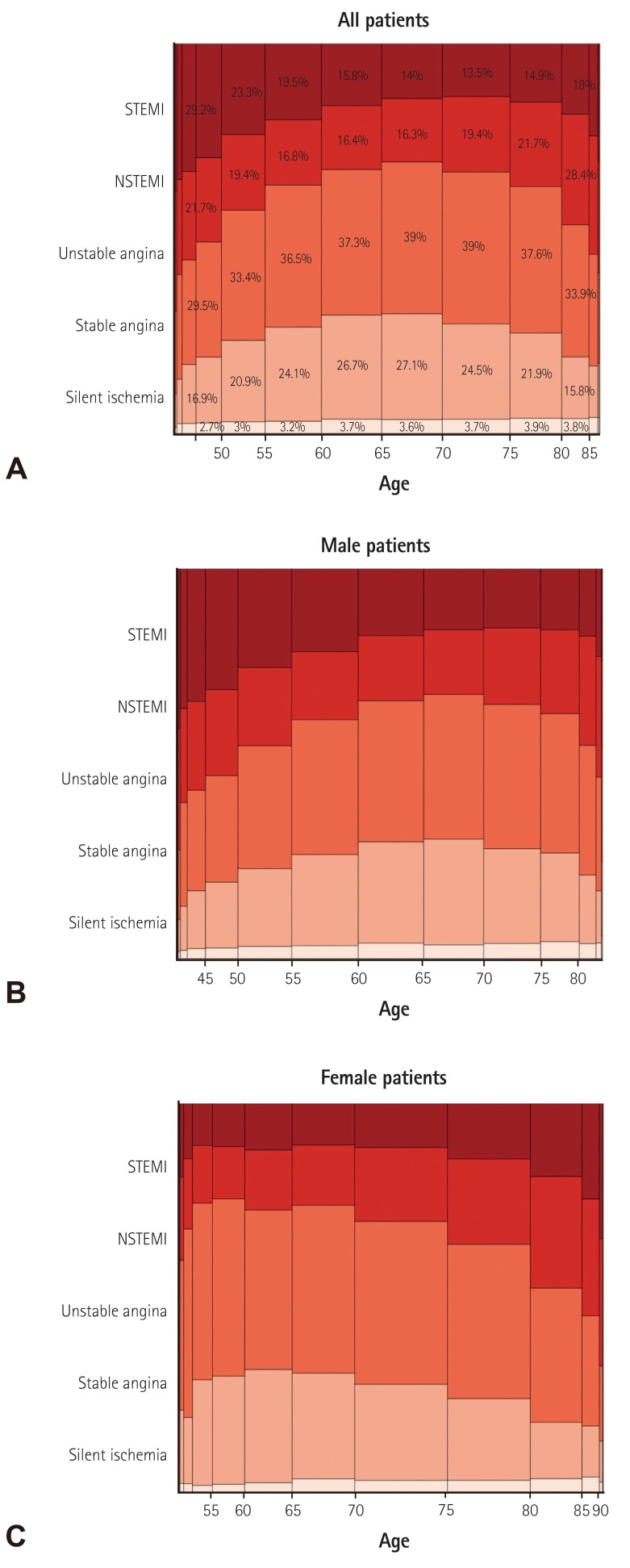

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of included patients are presented in Table 1). Median age was 66.0 [IQR 57.0-74.0] years and the proportion of male patients was 70.3% (Fig. 3). Among patients undergoing PCI, 35.9% had diabetes mellitus, 9.2% had history of prior myocardial infarction, 24% had history of PCI, 1.3% had prior coronary artery bypass surgery, 6.4% had renal failure, 8.8% had prior history of cerebrovascular disease, and 2.7% had peripheral vascular disease. Unstable angina was the most common initial presentation (35.9%) that was a clinical indication for PCI, followed by stable angina (22.6%), NSTEMI (19.7%), STEMI (18.4%), and silent ischemia (3.5%) (Fig. 4). Patients that were between 60-80 years, were more likely to present with stable angina compared with other age groups, whereas patients in younger groups and elderly groups were more likely to present with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (Fig 5A). However, when this age-diagnosis interaction was sorted by gender, there was a trend toward a higher incidence of ACS in young male patients and elderly female patients (Fig. 5B, C). Cardiogenic shock was identified in 3.1% and cardiac arrest was present in 2.3% of patients in the 24 hours prior to admission. Beta blocking agents were the most frequently prescribed antianginal medication (53.5%) within 2 weeks of the procedure, followed by calcium channel blockers (36.5%), nicorandil (24.1%), long-acting nitrates (17.6%), and trimetazidine (15.2%).

Table 1. Baseline patient and clinical characteristics.

| Variables | All (n=44967) | Men (n=31590) | Women (n=13377) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years (IQR) | 66.0 (57.0-74.0) | 63.0 (55.0-72.0) | 72.0 (65.0-78.0) | <0.001 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Diabetes | <0.001 | |||

| Any | 16139 (35.9) | 10710 (33.9) | 5429 (40.6) | |

| Insulin-dependent | 1601 (9.92) | 956 (8.92) | 645 (11.9) | |

| Hypertension | 27828 (61.9) | 18154 (57.5) | 9674 (72.3) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 17823 (39.6) | 12486 (39.5) | 5337 (39.9) | 0.748 |

| Current/recent smoker | 14376 (31.96) | 13499 (42.76) | 877 (6.55) | <0.001 |

| Family history of CAD | 2518 (5.60) | 1893 (5.99) | 625 (4.67) | <0.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 4132 (9.19) | 3170 (10.0) | 962 (7.19) | <0.001 |

| Prior PCI | 10798 (24.0) | 7792 (24.7) | 3006 (22.5) | <0.001 |

| Prior CABG | 598 (1.33) | 437 (1.38) | 161 (1.20) | 0.278 |

| Renal failure* | <0.001 | |||

| Any | 2877 (6.40) | 1931 (6.11) | 946 (7.07) | |

| Dialysis-dependent | 1134 (2.52) | 718 (2.27) | 416 (3.11) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3943 (8.77) | 2695 (8.53) | 1248 (9.33) | 0.023 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1198 (2.66) | 937 (2.97) | 261 (1.95) | <0.001 |

| Clinical indication for PCI | <0.001 | |||

| Silent ischemia | 1553 (3.45) | 1114 (3.53) | 439 (3.28) | |

| Stable angina | 10166 (22.6) | 7085 (22.4) | 3081 (23.0) | |

| Unstable angina | 16127 (35.9) | 10729 (34.0) | 5398 (40.4) | |

| NSTEMI | 8839 (19.7) | 6192 (19.6) | 2647 (19.8) | |

| STEMI | 8282 (18.4) | 6470 (20.5) | 1812 (13.5) | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 1395 (3.10) | 1015 (3.21) | 380 (2.84) | 0.114 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1034 (2.30) | 803 (2.54) | 231 (1.73) | <0.001 |

| Non-invasive stress or imaging test | ||||

| Stress test performed | ||||

| Done | 6269 (13.9) | 4688 (14.8) | 1581 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Negative (any stress test) | 1799 (4.0) | 1321 (4.2) | 478 (3.6) | |

| Positive (any stress test) | 4470 (9.94) | 3367 (10.7) | 1103 (8.25) | <0.001 |

| TMT positive | 2972 (6.61) | 2301 (7.28) | 671 (5.02) | <0.001 |

| Thallium positive | 1307 (2.91) | 931 (2.95) | 376 (2.81) | 0.817 |

| Stress echo positive | 271 (0.60) | 201 (0.64) | 70 (0.52) | 0.288 |

| Stress MR positive | 36 (0.08) | 28 (0.09) | 8 (0.06) | 0.611 |

| Pre-PCI LVEF† | ||||

| Done | 30383 (67.6) | 20908 (66.2) | 9475 (70.8) | <0.001 |

| Mean (±SD) | 60.0 (50.0-66.0) | 60.0 (50.0-65.0) | 61.0 (51.0-67.0) | <0.001 |

| Coronary CTA performed | 0.009 | |||

| Done | 6164 (13.7) | 4243 (13.4) | 1921 (14.4) | |

| 1 vessel disease | 2632 (42.7) | 1777 (41.9) | 855 (44.5) | 0.107 |

| 2 vessel diseases | 1855 (30.1) | 1293 (30.5) | 562 (29.3) | |

| 3 vessel diseases | 1457 (23.6) | 1019 (24.0) | 438 (22.8) | |

| Undetermined | 71 (1.15) | 56 (1.32) | 15 (0.78) | |

| Antianginal medications (within 2 weeks) | ||||

| Beta-blockers | 13146 (53.3) | 9184 (54.4) | 3962 (50.9) | <0.001 |

| Ca-channel- blockers | 8999 (36.5) | 5952 (35.3) | 3047 (39.1) | <0.001 |

| Long-acting nitrates | 4339 (17.6) | 2989 (17.7) | 1350 (17.3) | 0.493 |

| Nicorandil | 5934 (24.1) | 4062 (24.1) | 1872 (24.0) | 0.987 |

| Trimetazidine | 3745 (15.2) | 2602 (15.4) | 1143 (14.7) | 0.141 |

| Others | 4544 (18.4) | 3078 (18.2) | 1466 (18.8) | 0.270 |

Values are presented as number (%) if not otherwise specified. *GFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2, †can be assessed via invasive (i.e. left ventriculography) or non-invasive (i.e. echocardiography, magnetic resonance, computed tomography, or nuclear) testing. IQR: interquartile range, CAD: coronary artery disease, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG: coronary artery bypass graft, NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction, TMT: treadmill test, MR: magnetic resonance, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, SD: standard deviation, CTA: computed tomography angiography

Fig. 3. Age and gender distribution. Median age was 66 years and the proportion of male patients was 70.3%.

Fig. 4. Gender-specific clinical indications for PCI. The width of the bars in the histogram indicates the number of patients. NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

Fig. 5. Age-specific clinical indications for PCI. The width of the bars in the histogram indicates the number of patients. NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

Non-invasive test and imaging studies

From the total number of patients undergoing PCI, only 13.9% (9.8% in ACS patients, 25.8% in non-ACS patients) underwent certain types of non-invasive tests before the PCI (Table 1). The treadmill test (TMT) was the dominant stress test (6.7% in ACS patients, 19.5% in non-ACS patients). Of the non-ACS patients who underwent different types of non-invasive stress tests, 13.3% demonstrated positive TMT and 5.1% demonstrated positive thallium single-photon emission computed tomography. Stress echocardiography and stress magnetic resonance imaging studies were done in less than 1% of patients in this registry. Coronary computed tomography (CT) angiography was performed in 13.7% (10.0% in ACS, 24.1% in non-ACS) of patients and 42.7% of those patients had one vessel involved. Pre-PCI evaluation of left ventricular function was performed in 67.6% of patients and the mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 60.0%.

Procedural characteristics

Angiographic and procedural characteristics for each PCI procedure are presented in Table 2). More than half of the patients had multi-vessel CAD, whereas 42.7% of patients had single vessel involvement. The left anterior descending artery was the most frequently involved vessel (70.1%), followed by the right coronary artery (35.4%), left circumflex artery (27.3%), and left main coronary artery (4.9%). Among patients that underwent PCI, a chronic total occlusion lesion was present in 10.5% and an in-stent restenosis lesion was present in 7.6%. Graft vessel PCI was done in only 0.2 % of all procedures. Two-thirds of the PCI procedures were performed in an elective setting. In this registry the trans-radial approach was more frequently (56.1%) used for PCI procedures, compared to the trans-femoral approach (45.4%). Even among ACS patients, more than half (52.7%) of procedures were performed via the trans-radial approach.

Table 2. Baseline angiographic and procedural characteristics.

| Variables | All (n=44967) | Men (n=31590) | Women (n=13377) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease extent | <0.001 | |||

| 1 vessel disease | 19210 (42.7) | 13641 (43.2) | 5569 (41.6) | |

| 2 vessel diseases | 14674 (32.6) | 10352 (32.8) | 4322 (32.3) | |

| 3 vessel diseases | 10664 (23.7) | 7310 (23.1) | 3354 (25.1) | |

| Lesion location | ||||

| Left main | 2216 (4.93) | 1629 (5.16) | 587 (4.39) | 0.001 |

| Proximal LAD | 14327 (31.9) | 10083 (31.9) | 4244 (31.7) | 0.697 |

| Mid to distal LAD | 17200 (38.3) | 11468 (36.3) | 5732 (42.8) | <0.001 |

| LCX | 12294 (27.3) | 8732 (27.6) | 3562 (26.6) | 0.028 |

| RCA | 15925 (35.4) | 11392 (36.1) | 4533 (33.9) | <0.001 |

| Graft | 100 (0.22) | 75 (0.24) | 25 (0.19) | 0.352 |

| ISR lesion | 3421 (7.61) | 2426 (7.68) | 995 (7.44) | 0.351 |

| CTO lesion | 4740 (10.5) | 3561 (11.3) | 1179 (8.81) | <0.001 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||

| PCI status | <0.001 | |||

| Elective | 29971 (66.7) | 20536 (65.0) | 9435 (70.5) | |

| Urgent | 5458 (12.1) | 3836 (12.1) | 1622 (12.1) | |

| Emergent | 8981 (20.0) | 6836 (21.6) | 2145 (16.0) | |

| Salvage | 158 (0.35) | 116 (0.37) | 42 (0.31) | |

| PCI approach | ||||

| Trans-radial | 25213 (56.1) | 17884 (56.6) | 7329 (54.8) | <0.001 |

| Trans-femoral | 20396 (45.4) | 14146 (44.8) | 6250 (46.7) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical support tool | 0.505 | |||

| Not done | 43954 (97.7) | 30861 (97.7) | 13093 (97.9) | |

| Done (IABP or EBS) | 1002 (2.23) | 721 (2.28) | 281 (2.10) | |

| Adjunctive support tool | ||||

| IVUS use | 12846 (28.6) | 9339 (29.6) | 3507 (26.2) | <0.001 |

| FFR use | 1675 (3.72) | 1234 (3.91) | 441 (3.30) | 0.006 |

| Angioplasty device | ||||

| BMS | 483 (1.07) | 327 (1.04) | 156 (1.17) | 0.237 |

| DES | 41077 (91.3) | 28909 (91.5) | 12168 (91.0) | 0.060 |

| DEB | 2666 (5.93) | 1866 (5.91) | 800 (5.98) | 0.780 |

| POBA | 8611 (19.1) | 5953 (18.8) | 2658 (19.9) | 0.012 |

| Number of BMS | 0.144 | |||

| 1 | 372 (0.83) | 254 (0.80) | 118 (0.88) | |

| 2 | 81 (0.18) | 57 (0.18) | 24 (0.18) | |

| ≥3 | 30 (0.06) | 16 (0.05) | 14 (0.1) | |

| Number of DES | 0.121 | |||

| 1 | 27406 (60.9) | 19361 (61.3) | 8045 (60.1) | |

| 2 | 9784 (21.8) | 6841 (21.7) | 2943 (22.0) | |

| ≥3 | 3887 (8.64) | 2707 (8.53) | 1180 (8.81) |

Values are presented as number (%) and percent if not otherwise specified. LAD: left anterior descending, LCX: left circumflex, RCA: right coronary artery, ISR: in-stent restenosis, CTO: chronic total occlusion, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump, EBS: emergency bypass system, IVUS: intravascular ultrasound, FFR: fractional flow reserve, BMS: bare-metal stents, DES: drug-eluting stents, DEB: drug-eluting balloon, POBA: plain old balloon angioplasty

Mechanical support devices, such as an intra-aortic balloon pump or emergency bypass system, were used in 2.2% of all PCI procedures. Data on the use of PCI devices was also collected. At least one drug-eluting stent (DES) was placed in 91.3% of procedures, plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) without stent implantation was done in 19.1%, and drug-eluting balloon (DEB) was used in 5.9% of patients. A bare-metal stent was placed in only 1.1% of all patients. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was used in 28.6% of patients (27.1% in ACS patients, 32.7% in non-ACS patients) as an adjunctive PCI support tool, whereas fractional flow reserve (FFR) was only performed in 3.7% of patients (2.5% in ACS patients, 7.2% in non-ACS patients).

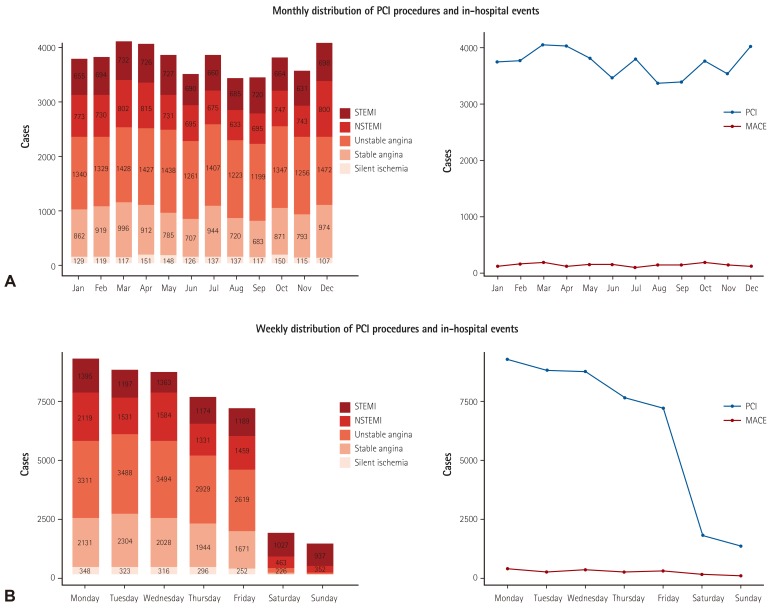

Clinical outcomes during hospitalization

Patient clinical outcomes during hospitalization are summarized in Table 3). The in-hospital, all-cause mortality for the entire cohort was 2.3% (1023 patients), of which 68.8% (704 patients) experienced cardiac-related deaths (Table 3). In-hospital mortality ranged from 0.2% in patients with stable angina to 6.9% in STEMI patients. Other in-hospital event rates were low including, non-fatal MI 1.6%, stroke 0.2%, urgent repeat revascularization 0.3%, and stent thrombosis in 0.4% (172 patients). There were significantly higher rates of all-cause mortality (3.0 vs. 2.0; p<0.001) and cardiac mortality (2.0 vs. 1.4%; p<0.001) in women undergoing PCI. The rates for transfusion during hospitalization were 2.2%, which was higher in women (2.9 vs. 1.9%; p<0.001). Although the number of PCI procedures peaked in March and December, the incidence of in-hospital events was evenly distributed throughout the year. However, the rates of in-hospital cardiac events were significantly higher when PCI cases were performed during weekends than for procedures performed during weekdays (9.4 vs. 3.8%; p<0.001; Fig. 6), this is likely because most cases performed over the weekend were in emergency settings.

Table 3. In-hospital outcomes.

| Variables | All (n=44967) | Men (n=31590) | Women (n=31590) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 1023 (2.28) | 629 (1.99) | 394 (2.95) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac death | 704 (1.57) | 432 (1.37) | 272 (2.03) | <0.001 |

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction | 701 (1.56) | 516 (1.63) | 185 (1.38) | 0.075 |

| Stent thrombosis | 172 (0.38) | 139 (0.44) | 33 (0.25) | 0.003 |

| Stroke | 90 (0.20) | 58 (0.18) | 32 (0.24) | 0.426 |

| Urgent repeat PCI | 118 (0.26) | 96 (0.30) | 22 (0.16) | 0.015 |

| Transfusion | 978 (2.17) | 589 (1.86) | 389 (2.91) | <0.001 |

Values are presented as number (%). PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Fig. 6. Temporal distribution of PCI procedures and in-hospital events. (A) Monthly distribution of PCI procedures and in-hospital cardiac events. (B) Weekly distribution of PCI procedures and in-hospital cardiac events. STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction, NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, MACE: major adverse cardiac events.

Centers patterns and results

To understand differences in demographics, procedural characteristics and clinical outcomes between high vs. low PCI volume centers, we divided all PCI centers into three tertiles based on the number of PCIs performed during the collection period (1st tertile: 41-493; 2nd tertile: 494-780; 3rd tertile: 781-1794). Patients in high-volume centers were more likely to have a history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, renal failure, peripheral vascular disease, prior PCI, and coronary artery bypass graft than patients from lower volume centers (Table 4). High volume centers had more stable patients, used non-invasive pre-tests more frequently, and more frequently performed elective PCI with a trans-radial approach using IVUS/FFR (Table 5). In contrast, low volume centers had higher incidences of acute myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest. Thus, these centers performed emergency PCI more frequently (24.4 vs. 14.9%; p<0.001) without IVUS/FFR and were less likely to conduct non-invasive pre-tests. Consequently, low volume centers showed higher in-hospital mortality (2.7 vs. 2.3 vs. 1.8%; p<0.001) (Table 6).

Table 4. Baseline patient and clinical characteristics by PCI case-volume.

| Variables | All (n=44967) | Low-tertile volume centers [41–493]* (n=15105) | Mid-tertile volume centers [494–780]* (n=15286) | High-tertile volume centers [781–1794]* (n=14576) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, years (IQR) | 66 (57-74) | 66 (57-75) | 66 (57-74) | 65 (57-74) | <0.001 |

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||

| Men | 31590 (70.3) | 10498 (69.5) | 10572 (69.2) | 10520 (72.2) | |

| Women | 13377 (29.7) | 4607 (30.5) | 4714 (30.8) | 4056 (27.8) | |

| Risk factors | |||||

| Diabetes | |||||

| Any | 16139 (35.9) | 5335 (35.3) | 5296 (34.6) | 5508 (37.8) | <0.001 |

| Insulin-dependent | 1601 (9.92) | 524 (9.82) | 511 (9.65) | 566 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 27828 (61.9) | 9165 (60.7) | 9492 (62.1) | 9171 (62.9) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 17823 (39.6) | 5065 (33.5) | 5531 (36.2) | 7227 (49.6) | <0.001 |

| Current/recent smoker | 14376 (31.96) | 4763 (31.57) | 4927 (32.21) | 4686 (32.10) | <0.001 |

| Family history of CAD | 2518 (5.60) | 762 (5.04) | 663 (4.34) | 1093 (7.50) | <0.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 4132 (9.19) | 1328 (8.79) | 1470 (9.62) | 1334 (9.15) | <0.001 |

| Prior PCI | 10798 (24.0) | 3298 (21.8) | 3692 (24.2) | 3808 (26.1) | <0.001 |

| Prior CABG | 598 (1.33) | 123 (0.81) | 167 (1.09) | 308 (2.11) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure† | <0.001 | ||||

| Any | 2877 (6.40) | 1012 (6.70) | 858 (5.62) | 1007 (6.91) | |

| Dialysis-dependent | 1134 (2.52) | 427 (2.83) | 307 (2.01) | 400 (2.74) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3943 (8.77) | 1357 (8.98) | 1350 (8.83) | 1236 (8.48) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1198 (2.66) | 307 (2.03) | 390 (2.55) | 501 (3.44) | <0.001 |

| Clinical Indication for PCI | <0.001 | ||||

| Silent ischemia | 1553 (3.45) | 347 (2.30) | 540 (3.53) | 666 (4.57) | |

| Stable angina | 10166 (22.6) | 2862 (18.9) | 2780 (18.2) | 4524 (31.0) | |

| Unstable angina | 16127 (35.9) | 5752 (38.1) | 5966 (39.0) | 4409 (30.2) | |

| NSTEMI | 8839 (19.7) | 3095 (20.5) | 2998 (19.6) | 2746 (18.8) | |

| STEMI | 8282 (18.4) | 3049 (20.2) | 3002 (19.6) | 2231 (15.3) | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 1395 (3.10) | 642 (4.25) | 443 (2.90) | 310 (2.13) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1034 (2.30) | 446 (2.95) | 333 (2.18) | 255 (1.75) | <0.001 |

| Non-invasive stress or imaging test | |||||

| Stress test performed | |||||

| Done | 6269 (13.9) | 1775 (11.8) | 1997 (13.1) | 2497 (17.1) | <0.001 |

| Negative (any stress test) | 1799 (3.96) | 497 (3.34) | 594 (3.92) | 708 (4.8) | |

| Positive (any stress test) | 4470 (9.94) | 1278 (8.46) | 1403 (9.18) | 1789 (12.3) | <0.001 |

| TMT Positive | 2972 (6.61) | 979 (6.48) | 829 (5.42) | 1164 (7.99) | <0.001 |

| Thallium positive | 1307 (2.91) | 201 (1.33) | 566 (3.70) | 540 (3.70) | <0.001 |

| Stress echo positive | 271 (0.60) | 108 (0.71) | 29 (0.19) | 134 (0.92) | <0.001 |

| Stress MR positive | 36 (0.08) | 3 (0.02) | 3 (0.02) | 30 (0.21) | <0.001 |

| Pre-PCI LVEF‡ | |||||

| Done | 30383 (67.6) | 10657 (70.6) | 9984 (65.3) | 9742 (66.8) | <0.001 |

| Mean (±SD) | 60.0 (50.0-66.0) | 60.0 (50.0-65.0) | 60.0 (49.5-65.3) | 60.0 (52.0-66.0) | <0.001 |

| Coronary CT performed | <0.001 | ||||

| Done | 6164 (13.7) | 1649 (10.9) | 1260 (8.24) | 3255 (22.3) | |

| 1 vessel disease | 2632 (42.7) | 752 (45.6) | 559 (44.4) | 1321 (40.6) | <0.001 |

| 2 vessel diseases | 1855 (30.1) | 474 (28.7) | 385 (30.6) | 996 (30.6) | |

| 3 vessel diseases | 1457 (23.6) | 359 (21.8) | 265 (21.0) | 833 (25.6) | |

| Undetermined | 71 (1.15) | 22 (1.33) | 8 (0.63) | 41 (1.26) | |

| Antianginal medications (within 2 weeks) | |||||

| Beta-blockers | 13146 (53.3) | 3564 (46.2) | 4499 (54.3) | 5083 (58.6) | <0.001 |

| Ca-channel-blockers | 8999 (36.5) | 2525 (32.8) | 2897 (35.0) | 3577 (41.2) | <0.001 |

| Long-acting nitrates | 4339 (17.6) | 1283 (16.6) | 1393 (16.8) | 1663 (19.2) | <0.001 |

| Nicorandil | 5934 (24.1) | 1908 (24.8) | 1741 (21.0) | 2285 (26.3) | <0.001 |

| Trimetazidine | 3745 (15.2) | 1316 (17.1) | 1328 (16.0) | 1101 (12.7) | <0.001 |

| Others | 4544 (18.4) | 1783 (23.1) | 1781 (21.5) | 980 (11.3) | <0.001 |

Values are presented as number and percent if not otherwise specified. *Centers were divided into three tertiles based on PCI case-volume (1st tertile: 41-493; 2nd tertile: 494-780; 3rd tertile: 781-1794), †GFR ≤60 mL/min/1.73 m2, ‡can be assessed via invasive (i.e. left ventriculography) or non-invasive (i.e. echocardiography, magnetic resonance, computed tomography, or nuclear) testing. IQR: inter-quartile range, CAD: coronary artery disease, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG: coronary artery bypass graft, NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction, TMT: treadmill test, MR: magnetic resonance LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, VD: vessel disease, SD: standard deviation

Table 5. Baseline angiographic and procedural characteristics by PCI case-volume.

| Variables | All (n=44967) | Low-tertile volume centers [41–493]* (n=15105) | Mid-tertile volume centers [494–780]* (n=15286) | High-tertile volume centers [781–1794]* (n=14576) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiographic characteristics | |||||

| Disease extent | <0.001 | ||||

| 1 vessel disease | 19210 (42.7) | 6795 (45.0) | 6249 (40.9) | 6166 (42.3) | |

| 2 vessel diseases | 14674 (32.6) | 4782 (31.7) | 5016 (32.8) | 4876 (33.5) | |

| 3 vessel diseases | 10664 (23.7) | 3371 (22.3) | 3872 (25.3) | 3421 (23.5) | |

| Lesion location | |||||

| Left main | 2216 (4.93) | 586 (3.88) | 718 (4.70) | 912 (6.26) | <0.001 |

| Proximal LAD | 14327 (31.9) | 4694 (31.1) | 5002 (32.7) | 4631 (31.8) | 0000.008 |

| Mid to distal LAD | 17200 (38.3) | 5373 (35.6) | 6047 (39.6) | 5780 (39.7) | <0.001 |

| LCX | 12294 (27.3) | 4101 (27.1) | 4370 (28.6) | 3823 (26.2) | <0.001 |

| RCA | 15925 (35.4) | 5453 (36.1) | 5612 (36.7) | 4860 (33.3) | <0.001 |

| Graft | 100 (0.22) | 20 (0.13) | 29 (0.19) | 51 (0.35) | <0.001 |

| ISR lesion | 3421 (7.61) | 998 (6.61) | 1080 (7.07) | 1343 (9.21) | <0.001 |

| CTO lesion | 4740 (10.5) | 1648 (10.9) | 1204 (7.88) | 1888 (13.0) | <0.001 |

| Procedural characteristics | |||||

| PCI status | <0.001 | ||||

| Elective | 29971 (66.7) | 9005 (59.6) | 9963 (65.2) | 11003 (75.5) | |

| Urgent | 5458 (12.1) | 1991 (13.2) | 2115 (13.8) | 1352 (9.28) | |

| Emergent | 8981 (20.0) | 3681 (24.4) | 3123 (20.4) | 2177 (14.9) | |

| Salvage | 158 (0.35) | 44 (0.29) | 77 (0.50) | 37 (0.25) | |

| PCI approach | |||||

| Trans-radial | 25213 (56.1) | 8117 (53.7) | 8536 (55.8) | 8560 (58.7) | <0.001 |

| Trans-femoral | 20396 (45.4) | 7123 (47.2) | 6969 (45.6) | 6304 (43.2) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical support tool | 0000.034 | ||||

| Not done | 43954 (97.7) | 14743 (97.6) | 14951 (97.8) | 14260 (97.8) | |

| Done (IABP or EBS) | 1002 (2.23) | 354 (2.34) | 332 (2.17) | 316 (2.17) | |

| Adjunctive support tool | |||||

| IVUS use | 12846 (28.6) | 3770 (25.0) | 4278 (28.0) | 4798 (32.9) | <0.001 |

| FFR use | 1675 (3.72) | 296 (1.96) | 382 (2.50) | 997 (6.84) | <0.001 |

| Angioplasty device | |||||

| BMS | 483 (1.07) | 70 (0.46) | 106 (0.69) | 307 (2.11) | <0.001 |

| DES | 41077 (91.3) | 13912 (92.1) | 14117 (92.4) | 13048 (89.5) | <0.001 |

| DEB | 2666 (5.93) | 993 (6.57) | 719 (4.70) | 954 (6.55) | <0.001 |

| POBA | 8611 (19.1) | 5041 (33.4) | 2153 (14.1) | 1417 (9.72) | <0.001 |

| No. of BMS | <0.001 | ||||

| 1 | 372 (0.83) | 53 (0.35) | 87 (0.57) | 232 (1.59) | |

| 2 | 81 (0.18) | 8 (0.05) | 12 (0.08) | 61 (0.42) | |

| ≥3 | 30 (0.06) | 9 (0.06) | 7 (0.05) | 14 (0.0) | |

| No. of DES | <0.001 | ||||

| 1 | 27406 (60.9) | 9578 (63.4) | 9320 (61.0) | 8508 (58.4) | |

| 2 | 9784 (21.8) | 3207 (21.2) | 3347 (21.9) | 3230 (22.2) | |

| ≥3 | 3887 (8.64) | 1127 (7.47) | 1450 (9.48) | 1310 (8.99) |

Values are presented as number (%) if not otherwise specified. *Centers were divided into three tertiles based on PCI case-volume (1st tertile: 41-493; 2nd tertile: 494-780; 3rd tertile: 781-1794). LAD: left anterior descending, LCX: left circumflex, RCA: right coronary artery, ISR: in-stent restenosis, CTO: chronic total occlusion, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump, EBS: emergency bypass system, IVUS: intravascular ultrasound, FFR: fractional flow reserve, BMS: bare-metal stents, DES: drug-eluting stents, DEB: drug-eluting balloon, POBA: plain old balloon angioplasty

Table 6. In-hospital outcomes by PCI case-volume.

| Variables | All (n=44967) | Low-tertile volume centers [41–493]* (n=15105) | Mid-tertile volume centers [494–780]* (n=15286) | High-tertile volume centers [781–1794]* (n=14576) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 1023 (2.28) | 403 (2.67) | 352 (2.30) | 268 (1.84) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac death | 704 (1.57) | 274 (1.81) | 240 (1.57) | 190 (1.30) | 0.001 |

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction | 701 (1.56) | 260 (1.72) | 237 (1.55) | 204 (1.40) | 0.171 |

| Stent thrombosis | 172 (0.38) | 86 (0.57) | 59 (0.39) | 27 (0.19) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 90 (0.20) | 32 (0.21) | 30 (0.20) | 28 (0.19) | 0.984 |

| Urgent re-PCI | 118 (0.26) | 38 (0.25) | 60 (0.39) | 20 (0.14) | <0.001 |

| Transfusion | 978 (2.17) | 246 (1.63) | 338 (2.21) | 394 (2.70) | <0.001 |

Values are presented as number (%). *Centers were divided into three tertiles based on PCI case-volume (1st tertile: 41-493; 2nd tertile: 494-780; 3rd tertile: 781-1794). PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Discussion

This study represents the first nationwide database for PCI in Korea that was collected and analyzed by the KSC/KSIC K-PCI registry. Key findings were as follows: 1) thirty-eight percent of patients presented with acute myocardial infarction and one-third of all PCI procedures were performed in urgent or emergency settings, 2) non-invasive stress tests were performed in 13.9% of cases, while coronary CT angiography was used in 13.7% of cases before PCI, 3) radial artery access was used in 56.1% of all PCI procedures, 4) devices used in PCI included DES, POBA, DEB, and BMS (91.3%, 19.1%, 5.9%, and 1.1% of all procedures, respectively), 5) the incidences of in-hospital death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and stroke were 2.3%, 1.6%, and 0.2%, respectively, 6) depending on the case volume of each center, there were differences in the baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and in-hospital clinical outcomes after PCI.

The National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) of the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) is a representative database that was developed to assist healthcare providers document their processes and quality of care in the cardiac catheterization laboratory.14),15) This registry records data on patient and hospital characteristics, clinical presentation, length of hospital stay, treatment information, and in-hospital outcomes for PCI procedures from >1000 sites across the United States. Several European countries are now conducting nationwide interventional registries that are organized either by a scientific society or the government.16),17),18),19),20) However, patterns for Korean PCI practice have differed, compared to western countries, therefore a Korean database that reflects relevant situations in Korea is needed.

After FDA approval, the use of DES rapidly increased by up to 89% of all stents that were implanted in 2005. However, after research presented in 2006 suggested that there was an increase in adverse events in patients that received DES, use declined to 66% of all stents and was recorded as 73% in 2011.21) In the US, physicians were less likely to use DES for patients that presented with myocardial infarction and were at high risk for stent thrombosis compared to unstable angina. In this cohort, DESs were used in 91.3% of all procedures, whereas only 1.1% of patients received bare-metal stents. Moreover, physicians consistently used DES across clinical diagnoses at initial presentation. Even in STEMI patients that underwent primary PCI, 92.2% received DES. Although the position of DES during primary PCI was not extensively established and increased risk of late stent thrombosis was indicated,22) the practice pattern of DES use might reflect a gap in knowledge between actual and alleged benefits of DES, thus representing a possibility to improve clinical outcomes and quality of care for patients with different clinical presentations.

In this cohort, IVUS was used in 32.7% and FFR was used in 7.2% of non-ACS cases as adjunct PCI support tools in patients undergoing PCI. These rates are higher than reported in US patterns of IVUS and FFR use.23) However, there was a significant increase in the use of FFR and IVUS, according to the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database of patients undergoing left heart catheterization between 2009 and 2011 in the US. Specifically, the number of in-hospital FFR utilization in US increased from 1173 cases in 2008 to 21365 cases in 2012, representing an 18-fold rise.24) Further research studies are needed to elucidate the implementation of adjunct PCI support tools in lesions with different locations and different severities in our cohort.

The overall in-hospital mortality rate for PCI patients in this report was somewhat higher than previous registries.25),26) In-hospital mortality among 181775 PCI procedures performed from January 2004 through March 2006 in US NCDR was 1.27%, ranging from 0.65% in elective PCI to 4.81% in STEMI patients.25) In our registry, in-hospital mortality ranged from 0.2% in patients with stable angina to 6.9% in STEMI patients. Higher overall in-hospital mortality in our registry can be partly explained by older age, more female patients, higher proportion of diabetes mellitus, and greater likelihood of undergoing emergency PCI in subjects included in our registry. Although the exact mechanism of higher mortality in the K-PCI registry has not been fully elucidated, additional mortality risk model assessment is needed to accurately measure patient risks in order to improve quality of care and shared decision making.27)

We found significant variations between high vs. low PCI volume centers in terms of baseline demographic, clinical characteristics and in-hospital clinical outcomes. For example, the frequency of non-invasive tests before PCI was 12% in low-tertile volume centers while 17% in high-tertile volume centers. The frequency of IVUS/FFR use during PCI was 27% in low-volume centers while 40% in high-volume centers. These actual differences, particularly the lower utilization of IVUS or FFR during procedures in low-tertile volume centers, suggest an important opportunity to improve the consistency of care for patients undergoing PCI because evidence indicates that adjunct PCI support tools can reduce repeat revascularization and stent thrombosis rates after PCI with DES implantation.28),29),30) The lower utilization of IVUS/FFR during PCI or non-invasive tests before PCI in low-volume centers could be related to critical care or patient emergencies. The low-volume centers had fewer patients with stable angina (20 vs. 35% in high-volume) and that underwent less elective PCI (60 vs. 75% in high-volume centers) than high-volume centers. In other words, low-volume centers more frequently performed urgent/emergency PCI for patients with ACS than high-volume centers. This could affect the ability of centers to use non-invasive tests before PCI or IVUS/FFR during PCI, which is possible in more stable patients or in PCI situations. This analysis was not designed to formulate definite conclusions from this observation. Therefore, additional research efforts are needed to elucidate how the differences in quality of care have affected clinical outcomes in high- vs. low-volume centers.

Performance measures and outcome implementation information from the K-PCI registry could provide data for creating and developing Korean guidelines for PCI, acute myocardial infarction, and unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. The K-PCI registry will support improvements in catheterization laboratory performance around the country and assist in the acquiring and maintaining individual physician certification for KSIC. The K-PCI registry committee is currently planning to capture catheterization data in 2016 and this report will be the most comprehensive database for PCI in Korea.

Limitations

There were some limitations to this study that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, patients and hospitals participating in the K-PCI registry may not have been representative of all Korean PCI procedures. However, the K-PCI registry represents 92 PCI-capable hospitals across Korea and captures the majority of PCI procedures performed nationally. Second, several factors may have influenced the decision-making of the interventional cardiologists represented in different region or different hospitals, in regards to procedural features, such as use of adjunct PCI tools and pre-PCI non-invasive test selection. Third, the K-PCI registry dataset only records clinical outcomes that occurred before hospital discharge prior to PCI. Moreover, given that our data were analyzed retrospectively, clinical outcomes associated with the clinical or procedural characteristics of patients or catheterization laboratories are observational and causality cannot be established. Fourth, data collection and reports lagged behind PCI procedures by 1 year, thus limiting rapid feedback of contemporary practices to implement quality improvement processes for the participating centers.

Conclusion

This study presents the first Korean PCI data collected and analyzed by the KSC/KSIC K-PCI registry. These data may provide an opportunity to understand current PCI practices and in-hospital outcomes in Korea and could be used as a foundation for developing treatment guidelines and nationwide clinical research.

Acknowledgments

This study was co-sponsored by the Korean Society of Cardiology (KSC) and Koran Society of Interventional Cardiology (KSIC). Authors acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Byung-Hee Oh (Chairman, Board of Directors, KSC in 2015-2016) and Dr. Tae-Hoon Ahn (Chairman, Board of Directors, KSIC in 2015-2016) who initiated the KPCI registry project in 2015.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

The online-only Data Supplement is available with article at https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2017.0071.

K-PCI registry 2014 CRF

References

- 1.Grech ED. ABC of interventional cardiology: percutaneous coronary intervention. I: history and development. BMJ. 2003;326:1080–1082. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7398.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:2354–2394. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Authors/Task Force members. Windecker S, Kolh P, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the task force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:e574–e651. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ba622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Gara P, Kushner F, Ascheim D, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e78–e140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bashore TM, Balter S, Barac A, et al. 2012 American College of Cardiology Foundation/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions expert consensus document on cardiac catheterization laboratory standards update: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus documents developed in collaboration with the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:2221–2305. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krumholz HM, Anderson JL, Bachelder BL, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 performance measures for adults with ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to develop performance measures for ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction): developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Emergency Physicians: endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Hospital Medicine. Circulation. 2008;118:2596–2648. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nallamothu BK, Tommaso CL, Anderson HV, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI/AMA-convened PCPI/NCQA 2013 performance measures for adults undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on performance measures, the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions, the American medical association-convened physician consortium for performance improvement, and the national committee for quality assurance. Circulation. 2014;129:926–949. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441966.31451.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sim DS, Jeong MH, Kang JC. Current management of acute myocardial infarction: experience from the Korea acute myocardial infarction registry. J Cardiol. 2010;56:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn JY, Chun WJ, Kim JH, et al. Predictors and outcomes of side branch occlusion after main vessel stenting in coronary bifurcation lesions: results from the COBIS II Registry (COronary BIfurcation Stenting) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1654–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee PH, Lee SW, Park HS, et al. Successful recanalization of native coronary chronic total occlusion is not associated with improved long-term survival. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SH, Jeong MH, Han KR, et al. comparison of transradial and transfemoral approaches for percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome and anemia. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1582–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KH, Kim CH, Jeong MH, et al. Differential benefit of statin in secondary prevention of acute myocardial infarction according to the level of triglyceride and high density lipoprotein cholesterol. Korean Circ J. 2016;46:324–334. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.3.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dehmer GJ, Weaver D, Roe MT, et al. A contemporary view of diagnostic cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: a report from the CathPCI registry of the national cardiovascular data registry, 2010 through June 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2017–2031. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson HV, Shaw RE, Brindis RG, et al. A contemporary overview of percutaneous coronary interventions. The American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC-NCDR) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banning AP, Baumbach A, Blackman D, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in the UK: recommendations for good practice 2015. Heart. 2015;10(Suppl 3):1–13. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia del Blanco B, Hernandez Hernandez F, Rumoroso Cuevas, JR, Trillo Nouche R. Spanish cardiac catheterization and coronary intervention registry. 23rd official report of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology (1990-2013) Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2014;67:1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harnek J, Nilsson J, Friberg O, et al. The 2011 outcome from the Swedish Health Care Registry on Heart Disease (SWEDEHEART) Scand Cardiovasc J. 2013;47(Suppl 62):1–10. doi: 10.3109/14017431.2013.780389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jernberg T, Attebring MF, Hambraeus K, et al. The Swedish web-system for enhancement and development of evidence-based care in heart disease evaluated according to recommended therapies (SWEDEHEART) Heart. 2010;96:1617–1621. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.198804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeymer U, Zahn R, Hochadel M, et al. Incications and complications of invasive diagnostic procedures and percutaneous coronary interventions in the year 2003. Results of the quality control registry of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausarzte (ALKK) Z Kardiol. 2005;94:392–398. doi: 10.1007/s00392-005-0233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bangalore S, Gupta N, Guo Y, Feit F. Trend in the use of drug eluting stents in the United States: insight from over 8.1 million coronary interventions. Int J Cardiol. 2014;175:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalesan B, Pilgrim T, Heinimann K, et al. Comparison of drug-eluting stents with bare metal stents in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:977–987. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dattilo PB, Prasad A, Honeycutt E, Wang TY, Messenger JC. Contemporary patterns of fractional flow reserve and intravascular ultrasound use among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2337–2339. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pothineni NV, Shah NS, Rochlani Y, et al. U.S. Trends in Inpatient Utilization of Fractional Flow Reserve and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:732–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson ED, Dai D, DeLong ER, et al. Contemporary mortality risk prediction for percutaneous coronary intervention: results from 588,398 procedures in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1923–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan BP, Clark DJ, Buxton B, et al. Clinical characteristics and early mortality of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting compared to percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons (ASCTS) and the Melbourne Interventional Group (MIG) Registries. Heart Lung Circ. 2009;18:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Committee for the Korean Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia. 2015 Korean guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia: executive summary (English translation) Korean Circ J. 2016;46:275–306. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:991–1001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang JS, Song YJ, Kang W, et al. Intravascular ultrasound-guided implantation of drug-eluting stents to improve outcome: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong SJ, Kim BK, Shin DH, et al. Effect of intravascular ultrasound-guided vs angiography-guided everolimus-eluting stent implantation: the ivus-xpl randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:2155–2163. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

K-PCI registry 2014 CRF