Abstract

Background

Outpatient care facilities provide a variety of basic healthcare services to individuals who do not require hospitalisation or institutionalisation, and are usually the patient's first contact. The provision of outpatient care contributes to immediate and large gains in health status, and a large portion of total health expenditure goes to outpatient healthcare services. Payment method is one of the most important incentive methods applied by purchasers to guide the performance of outpatient care providers.

Objectives

To assess the impact of different payment methods on the performance of outpatient care facilities and to analyse the differences in impact of payment methods in different settings.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), 2016, Issue 3, part of the Cochrane Library (searched 8 March 2016); MEDLINE, OvidSP (searched 8 March 2016); Embase, OvidSP (searched 24 April 2014); PubMed (NCBI) (searched 8 March 2016); Dissertations and Theses Database, ProQuest (searched 8 March 2016); Conference Proceedings Citation Index (ISI Web of Science) (searched 8 March 2016); IDEAS (searched 8 March 2016); EconLit, ProQuest (searched 8 March 2016); POPLINE, K4Health (searched 8 March 2016); China National Knowledge Infrastructure (searched 8 March 2016); Chinese Medicine Premier (searched 8 March 2016); OpenGrey (searched 8 March 2016); ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (searched 8 March 2016); World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (searched 8 March 2016); and the website of the World Bank (searched 8 March 2016).

In addition, we searched the reference lists of included studies and carried out a citation search for the included studies via ISI Web of Science to find other potentially relevant studies. We also contacted authors of the main included studies regarding any further published or unpublished work.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials, non‐randomised trials, controlled before‐after studies, interrupted time series, and repeated measures studies that compared different payment methods for outpatient health facilities. We defined outpatient care facilities in this review as facilities that provide health services to individuals who do not require hospitalisation or institutionalisation. We only included methods used to transfer funds from the purchaser of healthcare services to health facilities (including groups of individual professionals). These include global budgets, line‐item budgets, capitation, fee‐for‐service (fixed and unconstrained), pay for performance, and mixed payment. The primary outcomes were service provision outcomes, patient outcomes, healthcare provider outcomes, costs for providers, and any adverse effects.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently extracted data and assessed the risk of bias. We conducted a structured synthesis. We first categorised the comparisons and outcomes and then described the effects of different types of payment methods on different categories of outcomes. We used a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis within a study if a study included more than one indicator in the same category of outcomes. We used a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis across studies. If the data for meta‐analysis were not available in some studies, we calculated the median and interquartile range. We reported the risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and the relative change for continuous outcomes.

Main results

We included 21 studies from Afghanistan, Burundi, China, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Tanzania, the United Kingdom, and the United States of health facilities providing primary health care and mental health care. There were three kinds of payment comparisons.

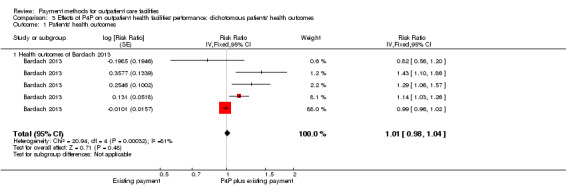

1) Pay for performance (P4P) combined with some existing payment method (capitation or different kinds of input‐based payment) compared to the existing payment method

We included 18 studies in this comparison, however we did not include five studies in the effects analysis due to high risk of bias. From the 13 studies, we found that the extra P4P incentives probably slightly improved the health professionals' use of some tests and treatments (adjusted RR median = 1.095, range 1.01 to 1.17; moderate‐certainty evidence), and probably led to little or no difference in adherence to quality assurance criteria (adjusted percentage change median = ‐1.345%, range ‐8.49% to 5.8%; moderate‐certainty evidence). We also found that P4P incentives may have led to little or no difference in patients' utilisation of health services (adjusted RR median = 1.01, range 0.96 to 1.15; low‐certainty evidence) and may have led to little or no difference in the control of blood pressure or cholesterol (adjusted RR = 1.01, range 0.98 to 1.04; low‐certainty evidence).

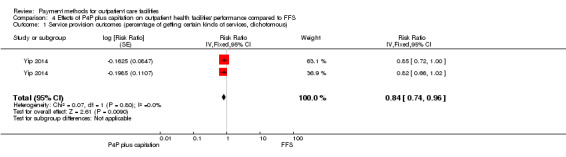

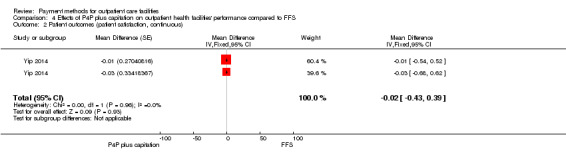

2) Capitation combined with P4P compared to fee‐for‐service (FFS)

One study found that compared with FFS, a capitated budget combined with payment based on providers' performance on antibiotic prescriptions and patient satisfaction probably slightly reduced antibiotic prescriptions in primary health facilities (adjusted RR 0.84, 95% confidence interval 0.74 to 0.96; moderate‐certainty evidence).

3) Capitation compared to FFS

Two studies compared capitation to FFS in mental health centres in the United States. Based on these studies, the effects of capitation compared to FFS on the utilisation and costs of services were uncertain (very low‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Our review found that if policymakers intend to apply P4P incentives to pay health facilities providing outpatient services, this intervention will probably lead to a slight improvement in health professionals' use of tests or treatments, particularly for chronic diseases. However, it may lead to little or no improvement in patients' utilisation of health services or health outcomes. When considering using P4P to improve the performance of health facilities, policymakers should carefully consider each component of their P4P design, including the choice of performance measures, the performance target, payment frequency, if there will be additional funding, whether the payment level is sufficient to change the behaviours of health providers, and whether the payment to facilities will be allocated to individual professionals. Unfortunately, the studies included in this review did not help to inform those considerations.

Well‐designed comparisons of different payment methods for outpatient health facilities in low‐ and middle‐income countries and studies directly comparing different designs (e.g. different payment levels) of the same payment method (e.g. P4P or FFS) are needed.

Plain language summary

Payment methods for outpatient care facilities

Review aim

The aim of this Cochrane review was to assess the effect of different payment systems for outpatient care facilities. We collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question and included 21 studies.

Key messages

Pay‐for‐performance systems probably have only small benefits or make little or no difference to healthcare provider behaviour or patients' use of healthcare services. We are uncertain whether they cause harm. We are uncertain about the benefits and harms of other payments systems because the research is lacking or of very low certainty.

What was studied in the review?

Many healthcare services are offered to patients through outpatient facilities rather than to inpatients in hospitals. Outpatient facilities are also known as ambulatory care facilities, and include primary healthcare centres, outpatient clinics, urgent care centres, family planning centres, mental health centres, and dental clinics.

Different systems to reimburse outpatient (ambulatory) care facilities for their services are available to governments and health insurers. These systems include:

• budget systems, where the facility is given a fixed amount of money in advance to cover expenses for a fixed period;

• capitation payment systems, where the facility is paid a fixed amount of money in advance to provide specific services to each enrolled patient for a fixed period;

• fee‐for‐service systems, where payment is based on the specific services that the healthcare facility provides;

• pay‐for‐performance systems, where payment is partly based on the performance of the facility's healthcare providers.

Different payment systems can have different effects on how healthcare facilities deliver care. These changes can be intentional or unintentional and can lead to both benefits and harms. At best, a payment system can encourage healthcare providers to offer the right healthcare services to the right patients in the best and most cost‐efficient way. However, payment systems can also lead providers to offer poor‐quality, expensive, and unnecessary care, which can ultimately have a negative impact on patients' health.

This Cochrane review assessed the effect of different payment systems for outpatient care facilities. Other Cochrane reviews have assessed the effect of different payment systems for individual healthcare professionals and for inpatient facilities.

Main results

We found 21 relevant studies from the United Kingdom, the United States, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, Afghanistan, China, and Democratic Republic of Congo. Most of the studies were from primary healthcare facilities. The studies assessed capitation systems, fee‐for‐service systems, and different types of pay‐for‐performance systems.

Pay‐for‐performance systems:

• probably slightly improve providers' use of some tests and treatments;

• probably lead to little or no difference in providers' compliance with quality assurance criteria;

• may lead to little or no difference in patients' use of health services;

• may lead to little or no difference in patients' health status.

Capitation combined with a pay‐for‐performance system targeted at reducing antibiotic use probably slightly reduces antibiotic prescriptions when compared to a fee‐for‐service system.

Two studies compared capitation with fee‐for‐service systems, however, we assessed the certainty of the evidence as very low.

We did not find any relevant studies that assessed budget systems.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

We searched for studies that had been published up to March 2016.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Outpatient care facilities, also known as ambulatory health facilities, are organisations that deliver healthcare services to individuals who do not require hospitalisation or institutionalisation. They provide a variety of types of health care including preventive health care, treatment of acute illness, dental care, and some types of maternal and family‐planning care. Most of these services are first‐contact and basic healthcare services. The provision of outpatient care contributes to immediate and large gains in health status, and a large portion of total health expenditure goes to outpatient healthcare services, especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Berman 2000).

Description of the intervention

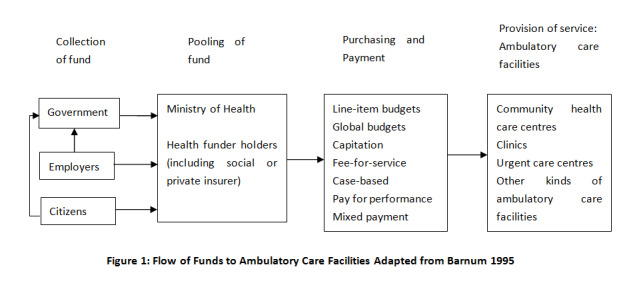

Based on Barnum's framework of "flow of funds under generic reforms" (Figure 1), the flow of funds would typically be from the Ministry of Health to government providers, and from social or private insurers, if they exist, to providers. Different payment methods can be used for different outpatient care facilities (Barnum 1995).

1.

The most commonly used payment systems to remunerate outpatient care facilities are budgets, capitation, fee‐for‐service, pay for performance, and mixed systems (Barnum 1995; Langenbrunner 2009; WHO 2000).

Line‐item budgets

The allocation of a fixed amount of funds to a healthcare provider to cover specific line items (or input costs), such as personnel, utilities, medicines, and supplies, for a certain period of time (Langenbrunner 2009). Line‐item budgets are widely used in low‐ and middle‐income countries and are often an important part of a centrally directed healthcare system (Barnum 1995).

Global budgets

A payment fixed in advance to cover aggregate expenditures for a given period. This method is used by government or insurers to pay hospitals (Hirdes 1996; Wolfe 1993), as well as some types of outpatient care facilities. For example, in 1996 the National Health Insurance program in Taiwan implemented a global budget payment system for clinics with the aim of reducing pharmaceutical expenditures (Lee 2006). Global budgets can be an important element of health sector reforms such as decentralisation of the healthcare system.

Capitation

The provider is paid a predetermined fixed rate in advance to provide a defined set of services for each individual enrolled with the provider for a fixed period. Capitation payment may be a flat fee for each of the enrollees or it can be a risk‐adjusted fee, based on the relative risk of the registered population. This payment method has been widely used in low‐, middle‐, and high‐income countries. For example, in Thailand, capitation was used to motivate hospitals to provide comprehensive health services (ILO/UNDP 1993); it was also used to pay primary care providers in Hungary (Deeble 1992).

Fee‐for‐service

Providers are reimbursed based on specific items provided. Fee‐for‐service, with fixed‐fee schedules or without (unconstrained), is commonly used in such countries as Canada, China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea; among private insurers in the Gulf states, such as Saudi Arabia; in indemnity plans in the United States (a type of health insurance that reimburses the patient or provider as expenses are incurred) (Pati 2005); and in parts of Western Europe, such as Austria and Germany.

Pay for performance

The payment is directly linked to the performance of healthcare providers. Pay for performance can be used to pay individuals, groups of people, or organisations by government or insurers. Pay‐for‐performance schemes vary widely in terms of the types of performance that are targeted, how performance is measured, when payments for performance are paid, the size of payments for performance, and the proportion of total reimbursements that is paid for performance (Witter 2012).

Mixed systems

A mixed system may be adopted simply because it is administratively more practical or to counter the adverse incentives of specific payment methods while retaining their desirable features. Most provider payment systems are mixed.

Categories of payment methods

Provider payment methods can be categorised based on three characteristics (Table 4) (Langenbrunner 2009):

1. Outpatient care facilities payment methods and characteristics.

| Payment methods | Payment rate determined | Payment made | Payment related to | |||

| Prospectively | Retrospectively | Prospectively | Retrospectively | Inputs | Outputs | |

| Line‐item budgets | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Global budgets | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Capitation | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Fee‐for‐service | ||||||

| ‐Unconstrained | √ | √ | √ | |||

| ‐Fixed | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Pay for performance | √ | √ | √ | |||

whether payment rates to providers for a single service or a package of services are set prospectively (in advance) or retrospectively (after services are provided). For prospectively set payment methods, services are bundled into a package reimbursed at a fixed payment rate, and some financial risk is shifted from the purchaser to the provider. Alternatively, payment rates are set retrospectively when the provider is simply reimbursed the amount that is billed, the reimbursement rates reflect the cost of providing the services, and the purchaser bears all the financial risk;

whether payment to the provider is made prospectively (before services are provided) or retrospectively (after services are provided). With prospective rate setting, the actual payment may be made either prospectively or retrospectively;

whether the payment that is made to providers is based on inputs used to provide services (i.e. all costs of providing services are financed) or on outputs produced, such as cases treated, bed‐days completed, or individual services provided (i.e. each test, procedure, or consultation).

How the intervention might work

Different types of payment methods have different incentives. Retrospective payment systems provide incentives to providers to deliver more services, and thereby might increase utilisation of services. There is little risk for providers, provided the payments are appropriate, and there are no incentives for patient selection. However, retrospective payment systems can also provide incentives to provide unnecessary and inappropriate care. Retrospective payments can also provide incentives to deliver desired services, thereby improving quality. In contrast, prospective payment methods can provide incentives to deliver rational levels of services, to improve efficiency, and to contain costs (Langenbrunner 2009).

An input‐based payment method creates incentives to increase the number of inputs. An output‐based payment method creates stronger incentives to increase the number or quality of services delivered. The lower the levels of aggregation at which services are defined as outputs, the greater the incentives are to increase the number of services delivered.

Based on these theoretical incentives, different payment methods might be expected to have different effects on the quality and quantity of services provided per patient, the efficiency (cost per unit), and selection of patients (risk selection) (Table 5).

2. Incentives in pure reimbursement systems of outpatient care facilities.

| Reimbursement type | Performance | ||||

| Services/Case | Quantity | Quality | Cost/Unit | Risk selection | |

| Line‐item budgets | ‐ | ‐‐ | ‐ | + | 0 |

| Global budgets | ‐‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐‐ | 0 |

| Capitation | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐ | ‐‐ | ++ |

| Fee‐for‐service | |||||

| ‐Unconstrained | ++ | + | ‐‐ | ‐ | 0 |

| ‐Fixed | ++ | + | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | + |

| Case‐based | ‐‐ | ++ | ++ | ‐‐ | + |

| Pay for performance | + | ++ | ++ | ‐‐ | + |

Line‐item budgets are input‐based, whereas global budgets can be input‐ or output‐based payments. Both are prospective, which means that providers have incentives to under‐provide services (negative effects) and increase inputs, and no incentives to improve the efficiency of the input mix. The main incentive of global budgets is to encourage providers to control healthcare costs, rather than to improve performance.

Fee‐for‐service with a fixed‐fee schedule and bundling of services is output‐based, which provides incentives to increase the number of services delivered, including unnecessary ones (negative effects), and to reduce the amount of input per service. Fee‐for‐service with no fixed‐fee schedule (unconstrained) is input‐based and retrospective. The provider has incentives to increase the number of services and increase inputs.

Capitation is output‐based and prospective. The provider has incentives to increase output or attract more patients to enrol, which increases the total payment received. Providers might attract enrollees through improved quality of care, additional services that are not typically covered, or other measures that patients may perceive as increasing the benefit of enrolling with that provider rather than with another provider. It also provides incentives to improve efficiency of the input mix and decrease inputs, focus on less expensive health promotion and prevention, and attempt to select healthier enrollees (negative effects).

Pay‐for‐performance is output‐based and retrospectively paid for the providers. Providers are informed as to how much they could be paid with different levels of performance on service provision. It motivates the providers behaviour to the desired performance target, which could be the improvement in quantity or quality of services; however, it can also result in providers selecting the patients who are easier to achieve the performance target (e.g. blood pressure control) and ignoring the services that are not included in the performance target (negative effects).

Administrative costs are incurred whatever payment methods are used. Administrative costs include the costs of making payments and monitoring inputs, outputs (quantity and quality of services provided). More complex payment methods, such as pay‐for‐performance schemes, entail more administrative costs.

Why it is important to do this review

Several systematic reviews have evaluated the effects of payment to individual health providers (Flodgren 2011; Gosden 2000; Scott 2011). However, little is known about the effects of the different types of payment system on performance of healthcare facilities.

This review focused on payment for healthcare facilities providing outpatient services. Together with the Cochrane reviews on payment methods for individual health professionals and payment methods for hospitals (Jia 2015; Mathes 2014), this review will contribute to the evidence on which types of payment methods are effective in improving provision of outpatient health services, from which policy advice can be disseminated to policymakers in different countries and managers of health insurance.

Objectives

To assess the impact of different payment methods on the performance of outpatient care facilities and to analyse the differences in impact of payment methods in different settings.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials, including cluster‐randomised trials

Non‐randomised trials

Interrupted time series and repeated measures studies with:

a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred;

at least three data points before and three data points after the intervention.

Controlled before‐after studies with:

contemporaneous data collection;

a minimum of two intervention and two control sites.

Types of participants

We evaluated the payment targeted to health facilities, so outpatient care facilities are the participants included in this review. Outpatient care facilities, also known as ambulatory health facilities, are those facilities that provide health services to individuals who do not require hospitalisation or institutionalisation, including community healthcare centres, clinics (including outpatient clinics), urgent care centres, family planning centres, mental health centres, and dental clinics. We also included primary care practices (groups of individual professionals).

As some studies might investigate the individual patients to measure the performance of health facilities as the impact of payment methods, the participants in this review also included patients receiving services from outpatient care facilities.

Types of interventions

The payment methods varied with respect to the level at which the incentives were targeted. We only included the provider payment method that was used to transfer funds from the purchaser of healthcare services to the level of health facilities (including groups of individual professionals). In this review, payment methods included:

global budgets;

line‐item budgets;

capitation;

fee‐for‐service (fixed and unconstrained) (FFS);

pay for performance (P4P);

mixed payment.

We included comparisons of:

any two types or combinations of the above payment methods for outpatient care facilities; or

changes in the design of a payment method, such as increasing or decreasing the level of funding, changing the payment frequency, or changing performance target used in P4P.

We excluded methods of paying individuals who work in outpatient care facilities.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

To be included, the study must have reported at least one of the following objective measures of outpatient care facilities' performance in health services provision.

-

Service provision outcomes (controlled by providers' behaviour):

Quantity of health services provided (e.g. proportion of patients getting aspirin prescription, rate of referral of smokers to quit line);

Quality of health services provided (e.g. adherence to guidelines, quality score for certain health services).

-

Patient outcomes (not only controlled by providers' behaviour):

Patients' utilisation of health services (e.g. proportion of women having any prenatal care, proportion of children being fully immunised);

Patients' intermediate and final health outcomes (e.g. blood pressure of patients with hypertension, health‐related quality of life, mortality).

Healthcare provider outcomes (e.g. workload, work morale)

Costs for providers (e.g. cost per service, administration costs, total cost for purchasers)

Adverse effects (e.g. unnecessary services, reduced access to services (especially for disadvantaged populations), and patient selection)

Secondary outcomes

Satisfaction of patients, providers, or other stakeholders.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), 2016, Issue 3, part of the Cochrane Library (searched 8 March 2016)

MEDLINE, 1946 to present, In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, OvidSP (searched 8 March 2016)

Embase, 1947 to present, OvidSP (searched 24 April 2014)

PubMed, 1966 to present (searched 8 March 2016)

Dissertations and Theses Database, 1861 to present, ProQuest (searched 8 March 2016)

Conference Proceedings Citation Index, 1990 to present (ISI Web of Science) (searched 8 March 2016)

IDEAS Research Papers in Economics, 1927 to present (searched 8 March 2016)

EconLit, 1969 to present (searched 8 March 2016)

ProQuest (searched 8 March 2016)

POPLINE (Population Information Online), 1970 to present, K4Health (searched 8 March 2016)

China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CHKD‐CNKI), 1915 to present, (searched 8 March 2016)

Chinese Medicine Premier (Wanfang Data), 1988 to present, (searched 8 March 2016)

Website of the World Health Organization(www.who.int/en/) (searched 8 March 2016)

Website of the World Bank (www.worldbank.org/) (searched 8 March 2016)

The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Information Specialist developed the MEDLINE strategy in consultation with the authors.

Search strategies are comprised of keywords and controlled vocabulary terms. We applied no language limits. We searched all databases from database start date to date of search.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We conducted a grey literature search to identify studies not indexed in the databases listed above. We searched one grey literature database: OpenGrey (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) (www.opengrey.eu/) (searched 8 March 2016).

Trial registries

ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Institutes of Health (clinicaltrials.gov/) (searched 8 March 2016)

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en/) (searched 8 March 2016)

In addition, we:

searched reference lists of all relevant papers identified;

searched Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index, ISI Web of Science, for papers citing any studies included in the review;

searched PubMed for related citations to any studies included in the review;

contacted authors of relevant papers regarding any further published or unpublished work.

All search strategies are provided in Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors scanned titles and abstracts of all articles obtained from the search and retrieved the full text of articles deemed relevant. Two review authors independently assessed full texts of studies for inclusion. Any disagreements on inclusion were resolved by discussion with a third review author or EPOC editor.

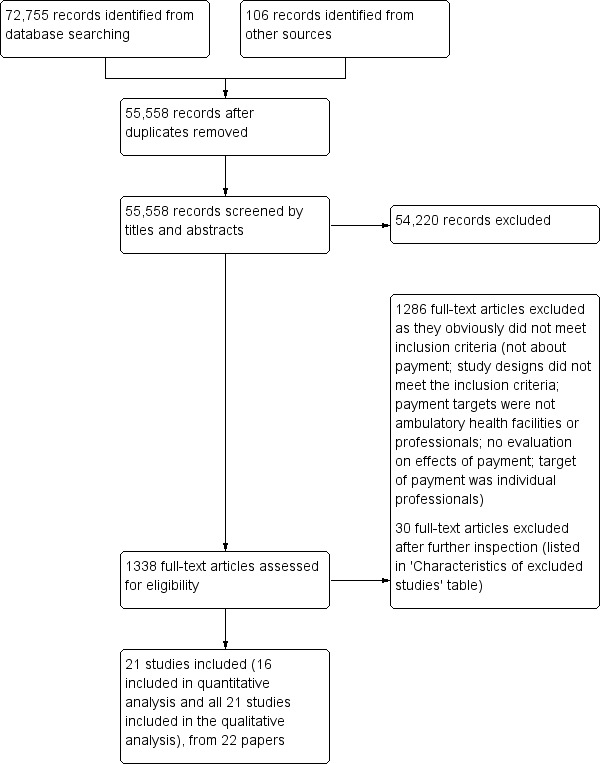

The screening process and results are reported in a study flow chart (Figure 2). We described all included studies in the Characteristics of included studies tables, even if the included studies did not report usable results for re‐analysis or synthesis. We listed studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, but were eventually excluded, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

2.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently carried out data extraction using a data extraction form adopted from the Cochrane good practice data collection form (EPOC 2013a). The information we extracted included:

general information of study;

participants and setting;

study method;

intervention groups, including payment method description, duration of intervention, if patients can choose providers, how purchasers monitored the implementation of payment;

outcomes, including outcome measures, time points measured, unit of measurement, and person measuring outcomes;

results, including results reported by authors, analysis method, unintended effects, if re‐analysis was required and possible.

Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third review author or the EPOC contact editor. Data were managed in Microsoft Word. For interrupted time series (ITS) studies reporting time series data that are not appropriately analysed, we extracted and re‐analysed the data as described in the EPOC resources for review authors (EPOC 2013b).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the EPOC suggested 'Risk of bias' criteria to assess the risk of bias for each outcome in all included studies (EPOC 2013c). For each criterion, two review authors independently described what was reported in the study, commented on the description, and judged the risk of bias. Any unresolved disagreements were discussed with a third review author, and, if consensus could not be reached, with the EPOC contact editor. We summarised the overall risk of bias across criteria for the primary outcome of the included studies. For randomised trials, non‐randomised trials, and controlled before‐after studies, we primarily considered four criteria: baseline outcome measurements, baseline characteristics measurements, incomplete outcome data addressed, and protection against contamination. If all four criteria were scored 'low risk of bias' for the outcome in a study, the summary assessment was that there was a low risk of bias; if one or more key criteria were scored 'unclear', the summary assessment was unclear risk of bias. If one or more key criteria were scored 'high risk of bias', the summary assessment was high risk of bias. For ITS studies, when we summarised the overall risk of bias across these criteria, we primarily considered the following criteria: intervention independence, intervention affecting data collection, and incomplete outcome data addressed.

Measures of treatment effect

For randomised trials, non‐randomised trials, and controlled before‐after studies, we recorded or calculated risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous outcomes. If adjusted analysis was done, we reported the effect estimates reported by the authors, also converting them into RRs when possible. For continuous outcomes, when possible, we reported the absolute change from a statistical analysis adjusted for baseline differences or the relative change adjusted for baseline differences in the outcome measures. If not enough data were provided for statistical analysis, we only reported the absolute and relative change adjusted for baseline differences.

For interrupted time series and repeated measures studies, we attempted to report the difference between the predicted value based on the pre‐intervention trend and the estimated value based on the change in level and postintervention trend at relevant time points (including immediately after the intervention (change in level), one year, two years, and three years). However, in all included interrupted time series studies, only one paper provided enough data for us to calculate the above effect outcomes, so for other interrupted time series studies, we only used change in level immediately after intervention and change in trend to measure the treatment effects, or the effects results reported by the authors if any re‐analysis was not possible.

We included five controlled before‐after studies with very high risk of bias and unclear reporting for a large number of outcomes, but did not use them in effects analyses (Bonfrer 2014a; Canavan 2008; Rudasingwa 2015; Soeters 2008; Soeters 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to re‐analyse comparisons that allocated clusters (e.g. clinics in one district) but did not account for clustering, if we could extract the intracluster coefficient. However, all included studies adjusted for clustering in their analyses.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the original investigators to request missing data. At the time of submission of this review we had not received any response on missing data. We used the available data for those studies reporting the point estimate of effect measures without confidence intervals or, if that information was missing, we included the study in the review, but not in analyses of the effects of payment methods. If information on subgroup analyses was missing (e.g. for P4P, the size of the incentive or frequency of payment), we contacted the original investigators to request information. We received replies from two authors regarding P4P interventions. If we did not receive a response clarifying the P4P design, we did not include the study in subgroup analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We conducted meta‐analysis to synthesise the effect measures of included studies if they had:

similar intervention and comparison payment methods: the payment methods evaluated by all studies were defined as the same category of payment;

same participants: e.g. all targets of payment methods included were primary care clinics or practices;

same category of outcome measures: e.g. all outcome measures were health service provision measures, or all were patient outcome measures.

When the included studies were similar enough based on the above criteria, we used the Chi2 test and I2 statistic to assess statistical heterogeneity. When the P value from a Chi2 test was smaller than 0.1, we interpreted this as an indication that the observed difference in results across studies was unlikely to have occurred by chance alone.

We used the random‐effects model for meta‐analysis across studies, because the payment methods included several components; the payment methods conducted by different purchasers or in different areas were not exactly the same; and the effectiveness of payment methods may also have been influenced by many contextual factors that varied in different studies. In addition, the outcome measures under the same category were not exactly the same in different studies.

We explored heterogeneity in the design of payment methods through prespecified subgroup analyses. We downgraded the certainty of the evidence for results from meta‐analyses with high levels of heterogeneity without a compelling explanation for the heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use funnel plots to examine asymmetry and assess the potential of any asymmetry being due to publication bias. However, there were too few studies of similar comparisons to allow for a meaningful assessment of asymmetry.

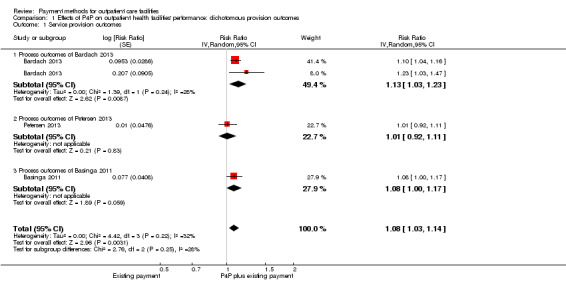

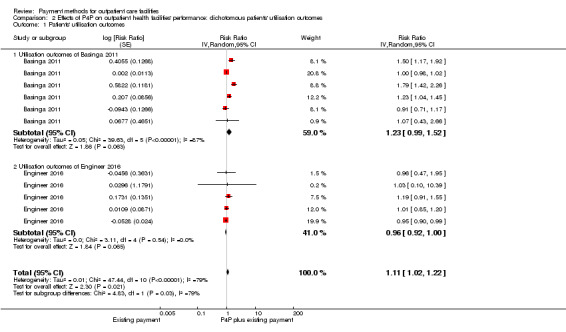

Data synthesis

We conducted a structured synthesis, as described in the EPOC resources for review authors (EPOC 2013d). We firstly categorised the comparisons and outcomes, and then described the effects of different kinds of payment methods on different categories of outcomes. We also listed and described the differences in context and components of payment methods in different studies. We considered the potential influence of these factors on the effects of the payment methods in the Discussion. We planned on using meta‐analysis if we found more than one study with similar comparisons and outcomes. Only three randomised trials, Bardach 2013, Engineer 2016, and Petersen 2013, and one controlled before‐after study, Basinga 2011, were similar enough and provided sufficient data for a meta‐analysis. For these studies, we firstly used a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis within a study, if the study included more than one outcome in the same category of outcome measures (service provision measures or patients outcome measures). We then used the random‐effects model for meta‐analysis across studies. If the data for meta‐analysis were not available in some studies, we calculated the median and interquartile range of effect sizes, if there was a sufficient number of included studies. We reported RRs for dichotomous outcomes and the relative change for continuous outcomes.

For the synthesised effects of each comparison, we assessed the certainty of evidence for each outcome(i.e. the extent of our confidence in the estimate of effect across studies) using the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Based on the incentives of different reimbursement systems for outpatient care facilities (Table 5), in the protocol for this review we hypothesised and analysed the following factors (Table 6) that might affect the size of effects of payment methods to explain any differences in the effects of payment methods.

3. Factors that might modify the effects of changes in payment methods on the delivery of services per case.

| Explanatory factors | How we will categorise the factor | Hypothesised direction of the interaction | Basis for the hypothesis |

| Larger fees (per service) | Relative increase in fees (continuous) | Larger (positive) effects with larger relative increases | The larger the incentive, the larger the effect |

| Duration of follow‐up | When outcomes are measured relative to when the change was made (continuous) | Larger (positive) effects with shorter follow‐up | Other changes and adjustments over time might reduce the initial incentive. |

| Ownership | For‐profit vs not‐for‐profit ownership | Larger (positive) effects with for‐profit ownership | For‐profit facilities might be more motivated to increase income and therefore more sensitive to changes in incentives. |

| Multiple providers | Choice of providers available to patients vs little or no choice of providers | Larger (negative) effects with little or no choice | Need to attract and retain patients might provide counteractive incentives to offer more services. |

| Monitoring | Monitoring vs no monitoring of the delivery of services | Larger (negative) effects without monitoring | Monitoring might provide counteractive incentives to offer more services. |

Larger fees: Relative increase in fees.

Duration of follow‐up: When outcomes are measured relative to when the change was made.

Ownership: For‐profit versus not‐for‐profit ownership.

Multiple providers: Choice of providers available to patients versus little or no choice of providers.

Monitoring: Monitoring versus no monitoring of the delivery of services.

Of the three kinds of comparisons included in this review, there were enough studies for conducting subgroup analysis for only one comparison (between P4P plus existing capitation or input‐based payment with the existing payment method). Especially for the P4P, we hypothesised and analysed the following factors that might affect the size of effects of P4P payment to explain any differences in the effects of payment methods; these factors and hypothesis were based on the dimensions of P4P schemes defined by Conrad and Perry and the analysis of results‐based financing by Oxman (Conrad 2009; Oxman 2009).

Type of performance measures applied by P4P: service provision measures, patient outcome measures, or combined measures (P4P with provision measures leads to larger effects because provision behaviour is easier to change).

Type of performance target applied by P4P: threshold payment, or pay for each instance of service (P4P with pay for each instance of service leads to larger effects because one instance of service is easier to achieve).

Size of incentive (percentage of P4P payment on total income level): lower than 10%, 10% to 30%, higher than 30% (the larger the size, the larger the effects).

Frequency of monitoring and feedback: quarterly, annual (the more frequently the monitoring and feedback, the larger the effects).

Frequency of payment: quarterly, annual (the more frequently the payment, the larger the effects).

Resourcing: involvement of extra fund or not (involvement of extra fund leads to larger effects because of the support of extra resources).

Individual payment inside facility: no payment to individual, equally allocated to individual, or allocated to individual based on individual performance (allocation to individual based on individual performance leads to larger effects because individual health workers are more motivated).

Duration of follow‐up: 1 year or less, 1.5 to 2 years, 3 years (larger effects with shorter follow‐up because changes and adjustments over time might reduce the initial incentive).

We did not include two factors we had prespecified in the protocol in the review: ownership (for‐profit versus not‐for‐profit ownership) and multiple providers (choice of providers available to patients versus little or no choice of providers), because data and information from the included studies were insufficient.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not use imputed data and did not include studies with a high risk of bias in meta‐analyses. We therefore did not conduct sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the findings in relation to assumptions about imputed data or judgments about the risk of bias, as planned in the protocol.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies

Results of the search

We identified 55,558 references after removing duplicates. We screened this large number of references because the searches were conducted without the study design filters in MEDLINE Ovid and Embase in order to also find relevant studies for a larger scoping review on payment for health facilities or individual providers.

Two researchers independently examined these references. We retrieved 1338 full‐text articles regarded as potentially relevant, which two review authors read independently. We included 21 studies evaluating payment methods for outpatient health facilities (Figure 2). Basinga 2011 and a 2010 unpublished working paper by the same authors were from the same study (a P4P program in Rwanda). They had the same outcomes measures, analysis methods, and study results, so we listed the unpublished working paper as a secondary reference to Basinga 2011. Bonfrer 2014a, Soeters 2008, and Rudasingwa 2015 were also from the same study (a P4P program in Burundi), but they applied different outcome measures, data sources, and analysis methods, therefore we treated them as three studies in the analysis.

Included studies

Study design

We included 21 studies (see Characteristics of included studies): eight randomised trials (An 2008; Bardach 2013; Engineer 2016; Hillman 1998; Hillman 1999; Petersen 2013; Roski 2003; Yip 2014), six controlled before‐after studies (Basinga 2011; Bonfrer 2014a; Canavan 2008; Rudasingwa 2015; Soeters 2008; Soeters 2011), four interrupted time series studies (Catalano 2000; Catalano 2005; McLintock 2014; Serumaga 2011), and three repeated measure studies (Alshamsan 2012; Chien 2012; Lee 2011).

Participants and settings

All of the facilities in the included studies provided primary health care or mental health care, although the facilities had different names in different countries. Four studies evaluated P4P for general practitioner practises in the United Kingdom (Alshamsan 2012; Lee 2011; McLintock 2014; Serumaga 2011). Nine studies were conducted in the United States, of which two included community mental health centres (Catalano 2000; Catalano 2005). The remaining seven studies included clinics providing different types of primary health care, Bardach 2013, An 2008, Petersen 2013, Roski 2003, Hillman 1998, and Hillman 1999, or physician groups providing primary health care (Chien 2012). Eight studies were conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Rwanda (Basinga 2011), Tanzania (Canavan 2008), Burundi (Soeters 2008), Democratic Republic of Congo (Bonfrer 2014a; Rudasingwa 2015; Soeters 2011), China (Yip 2014), and Afghanistan (Engineer 2016)). All of these studies from low‐ and middle‐income countries included primary healthcare facilities (centres).

Interventions' characteristics and comparison interventions

Characteristics of included studies tables provide a summary of the interventions and comparisons. The interventions varied. There were three types of comparisons: P4P plus some existing payment method (capitation or input‐based payment) compared to the existing payment method (Alshamsan 2012; An 2008; Bardach 2013; Basinga 2011; Bonfrer 2014a; Canavan 2008; Chien 2012; Engineer 2016; Hillman 1998; Hillman 1999; Lee 2011; McLintock 2014; Petersen 2013; Roski 2003; Rudasingwa 2015; Serumaga 2011; Soeters 2008; Soeters 2011); P4P combined with capitation compared to FFS (Yip 2014); and capitation versus FFS (Catalano 2000; Catalano 2005).

Most of the payment methods evaluated in the included studies were P4P, however the design of these P4P interventions varied. Based on the dimensions of P4P schemes defined by Conrad and Perry and the analysis of results‐based financing by Oxman (Conrad 2009; Oxman 2009), we systematically disentangled the P4P payment methods into seven components and described their characteristics (Table 7): the performance measures applied by P4P, the performance target for payment applied by P4P, size of incentive, frequency of monitoring, frequency of payment, individual payment inside the facility, and resourcing (if involvement of extra funding).

4. The characteristics of P4P payments included in review.

| Study | Performance measures | Performance target | Size of incentive | Frequency of monitoring | Frequency of payment | Individual payment | Resourcing (if with more funds) |

|

Alshamsan 2012 Lee 2011 Serumaga 2011 McLintock 2014 |

Both provision and outcome measures: 76 clinical quality indicators and 70 indicators relating to organisation of care and patient experience. Of the clinical indicators, 10 relate to maintaining disease registers, 56 to processes of care (such as measuring disease parameters and giving treatments), and 10 to intermediate outcomes (such as controlling blood pressure). | Threshold payment: Practices are awarded points based on the proportion of patients for whom targets are achieved, between a lower achievement threshold of 40% for most indicators (i.e. practices must achieve the targets for over 40% of patients to receive any points) and an upper threshold that varies according to the indicator. Each point earned the practice the certain level of money, adjusted for patient population size and disease prevalence. A maximum of 1000 points was available. | The highest level of performance payment is 25% of total income. | Annual | Annual | Allocated to individual based on individual performance | Yes |

| An 2008 | Provision outcome measures: referral of smokers to consultation | Threshold payment combined with payment for each instance: Clinics that referred 50 smokers would receive a USD 5000 performance bonus. Clinics would also receive $25 for each referral beyond the initial 50. | Not clear, but mentioned "This incentive amount was arrived at after consultation with the management team and represents an amount that was judged as likely to be meaningful to most clinics ..." | 10 months | 10 months | Into clinics' operation fund, no payment to individual physicians and administrators | Yes |

| Bardach 2013 | Both provision and outcome measures: 4 quality goals, including aspirin prescription, blood pressure control, cholesterol control, and smoking cessation intervention provision | Payment for each instance of performance measure unit: An incentive was paid for every instance of a patient meeting the quality goal (e.g. 1 blood pressure control USD 20). A higher payment was paid for patients with certain comorbidities or, as proxies for socioeconomic status, had Medicaid insurance or were uninsured. | Approximately 5% of an average physician's annual salary | Quarterly | Annual | Allocated to individual based on individual performance | Yes |

| Basinga 2011 | Process measures: The 14 key maternal and child healthcare output indicators. Some of these output indicators are reasons for a visit, such as prenatal care or delivery, whereas others are services provided during a visit, such as tetanus vaccination during prenatal care. | Payment for each instance of performance measure unit: Basis for payment is calculated based on the number of 14 kinds of services provided; the final payment level is adjusted based on quality index. | Facility funding increased by 22% | Quarterly | Quarterly | 77% of P4P1 funds to allocate to individual personnel, amounting to 35% increase in salary | No, control group funding also increased by the same level. |

| Canavan 2008 | Process measures: outpatient utilisation rate, delivery rate, VCT2 clients | Threshold payment: 50% of support paid upfront for the year; 50% paid retrospectively if all the targets are met (outpatient utilisation rate 0.6, delivery rate 20/1000, VCT2 clients 20/1000). | 8% of facility income | Semi‐annual | Semi‐annual | 50% maximum bonus allocated to individual | Yes |

| Chien 2012 | Both provision and outcome measures: diabetes patient completing all the missing care processes, and whether glycated haemoglobin and low‐density lipoprotein levels were lowered or at goal levels | Payment for each instance of performance measure unit: Certain amount of money for each patient paid if this patient met the performance target, e.g. USD 15 for 1 glycated haemoglobin test, USD 35 for glycated haemoglobin < 7%. | Not clear, but mentioned that "then incentive amount ... may not have been strong enough" | Annual | Annual | Not clear | Yes |

| Engineer 2016 | Provision outcome measures: volume of 9 primary health services provided, combined with service provision quality indicators | Payment for each instance of performance measure unit: Certain amount of bonus per unit per quarter, e.g. USD 1.30 to USD 2.67 for first antenatal care visit; final payment was also adjusted by quality indicators. | The bonus amounts paid were about 6% to 11% above health workers' base salary, and increased to about 14% to 28% depending on the health worker's cadre. | Quarterly | Quarterly | All allocated to individual, but the allocation method was determined by health facility managers, including giving individual bonuses proportional to the health worker's salary, giving them in equal amounts to all staff, or giving them based on their determination of an individual's contribution to the performance indicators. | Yes |

| Hillman 1998 | Provision outcome measures: compliance with a quality assurance policy, i.e. is referral of clinically indicated for Pap test, colorectal screening, or mammography | Threshold payment: 3 intervention sites with highest compliance scores received full bonus (20% of capitation); 3 with the next highest scores and the 3 improving most from previous audit both received partial bonus (10% of capitation). | 10% to 20% of capitation for all female members 50 years of age and older | Semi‐annual | Semi‐annual | Not clear, 38.5% of sites were solo group. | Yes |

| Hillman 1999 | Provision outcome measures: compliance with provision of defined services for children, including immunisation, other preventive services | Threshold payment: 3 intervention sites with highest compliance scores received full bonus (20% of capitation); 3 with the next highest scores and the 3 improving most from previous audit both received partial bonus (10% of capitation). | 10% to 20% of capitation for all paediatric members up to 7 years | Semi‐annual | Semi‐annual | Not clear, 42.1% of sites were solo group. | Yes |

| Petersen 2013 | Combined provision and outcome measures: blood pressure thresholds or appropriately responding to uncontrolled blood pressure, prescribing guideline‐recommended antihypertensive medications | Payment for each instance: a maximum prerecord reward of USD 18.20, USD 9.10 for each successful measure | Mean level was 1.6% of a physician's salary. | 4 months | 4 months | Equally allocated to individual physician, non‐physician in team | Yes |

| Roski 2003 | Provision outcome measures: Tobacco status clearly identified at each visit and documented in their medical records for their last visit; smokers should have provision of advice to quit smoking documented in their medical record. | Threshold payment: Performance targets were set at approximately 15 percentage points above the average performance for these clinic practices as assessed by the medical group 2 years prior to the effort described here. Incentive amounts were based on the number of providers per clinic. Specifically, clinics with 1 to 7 providers could receive a USD 5000 award, and clinics with 8 or more providers were eligible for a USD 10,000 bonus. Clinics that reached or exceeded only 1 of the 2 performance goals were eligible for half the amount. | Not clear, just discussed "it is not clear whether significantly higher incentive payments would have been able to focus clinic sites' attention more strongly on ..." |

Semi‐annual | Annual | Not clear, just mentioned "Clinics were provided with suggestions on how to spend earned incentive payments (i.e., travel and registration for educational courses). Ultimately, clinics decided how to allocate incentive payments." | Yes |

|

Soeters 2008 Bonfrer 2014a Rudasingwa 2015 |

Provision measures: health provision actions and quality composite index | Payment for each instance: Fixed amount paid per targeted action; multiplied by quality bonus ranging from 1 to 1.25 based on quarterly reviews of quality. | Studies published at different times reported different proportions: 58% of facility total revenue in 2009; in 2014, this part accounted for 40% of total health facility budget; in 2010, 20% of total health facility revenue. |

Quarterly | Quarterly | Allocated to individual based on individual performance, using a systematic approach called "indices". | Yes |

| Soeters 2011 | Provision measures: health provision actions and quality composite index with 154 indicators | Payment for each instance: Fixed amount paid per targeted action; top‐up of 15% available, based on quarterly reviews of quality. Also 15% additional payment for remote facilities. | Not clear, but should be the major component of funding for the health centres | Quarterly | Quarterly | Just mentioned facilities having discretion to pay staff. | Yes |

| Yip 2014 | Provision measures: antibiotic prescription rates and patient satisfaction | Threshold payment: 70% of the budget allocated to health facilities firstly, withholding the balance until after performance assessments at the middle and end of the year; after each assessment, the performance scores were compared between each health facility to the average score in the county; each centre that scored above the average received more than the 30% of the budget that had been withheld, in proportion to how much above the county average its score was. Each centre that scored below the average received less than the 30%, in proportion to how much lower than average its score was. | 30% of capitation budget | Semi‐annual | Semi‐annual | No allocation to individual | No |

1P4P: pay for performance 2VCT: voluntary counselling and testing

Performance measures applied by P4P

There were two categories of performance measures: provision performance measures and outcome performance measures. For the provision measures, payment was based on the providers' performance on the process of service provision, for example percentage of tobacco use identified and percentage of smokers receiving advice to quit (Roski 2003), percentage of patients whose blood pressure was measured (Serumaga 2011), percentage of patients with guideline‐based prescriptions and treatments (Petersen 2013), number or percentage of women having any prenatal care (Basinga 2011; Soeters 2008; Soeters 2011), or number or percentage of women with a facility‐based delivery (Basinga 2011; Bonfrer 2014a; Canavan 2008; Engineer 2016; Rudasingwa 2015; Soeters 2008; Soeters 2011). For the outcome measures, payment was based on patients' health or behaviour outcomes, for example the percentage of patients with blood pressure controlled (Alshamsan 2012; Bardach 2013; Petersen 2013), total cholesterol control (Alshamsan 2012; Lee 2011), or the percentage of smokers with seven‐days sustained abstinence from smoking (Roski 2003). There were also several P4P programs that used combined process and outcome performance measures (Alshamsan 2012; Bardach 2013; Lee 2011; Petersen 2013; Serumaga 2011).

Performance target for payment

This component is the level of performance for which the incentives were paid. There are two main categories in the included P4P methods: threshold payment and payment for each instance of performance. Threshold payment means that the providers only received the performance incentives if they achieved a certain level of performance, and this level of performance could be absolute performance or relative performance compared with other providers or their previous performance, for example at least 40% of covered patients with diabetes who have a record of total cholesterol (Alshamsan 2012; Lee 2011; Serumaga 2011), the outpatient utilisation rate achieving at least 0.6 per resident and the facility‐based delivery achieving at least 20/1000 (Canavan 2008), referral of at least 50 smokers (An 2008), percentage of tobacco status identified achieving 15% above the average performance (Roski 2003), or being one of six facilities with the highest compliance scores or one of three facilities improving the most from a previous audit (Hillman 1998; Hillman 1999). Payment for each instance of performance means providers received an award for each instance of service provision or patient's health improvement, for example payment of USD 20 for one case of blood pressure control (Bardach 2013), USD 15 for one glycated haemoglobin test (Chien 2012), or USD 18.20 payment for one blood pressure control or appropriate response to uncontrolled blood pressure (Petersen 2013). One P4P program used a combined performance target (An 2008), in which the intervention clinics who referred 50 smokers received a USD 5000 performance bonus, and clinics also received USD 25 for each referral beyond the initial 50.

Size of incentive

This component is the percentage of P4P incentives to the total income level of health facilities or individuals (if incentives were allocated to individuals within facilities). Some P4P incentives accounted for less than 10% of total income level of health facilities or individuals (Bardach 2013; Canavan 2008; Petersen 2013); in two P4P programs evaluated in four studies (Alshamsan 2012; Basinga 2011; Lee 2011; Serumaga 2011), incentive levels were about 20% to 25% of total facilities' income; in one program in Burundi (Soeters 2008), the P4P payments constituted 58% of facilities' revenue. In three studies, the levels of incentive were only compared with part of the facilities' revenue (20% of capitation for some female members 50 years of age and older) (Hillman 1998; Hillman 1999); 30% of capitation fee from one insurance plan (Yip 2014)). Several studies did not report the exact level of incentive (An 2008; Chien 2012; Roski 2003; Soeters 2011).

Frequency of monitoring and payment

The frequency of monitoring and payment was the same in most P4P programs, including quarterly (Basinga 2011; Bonfrer 2014a; Engineer 2016; Rudasingwa 2015; Soeters 2008; Soeters 2011), 4 months (Petersen 2013), semi‐annual (Canavan 2008; Hillman 1998; Hillman 1999; Yip 2014), 10 months (An 2008), and annual (Alshamsan 2012; Chien 2012; Lee 2011; McLintock 2014; Serumaga 2011). Two P4P programs had four times, in Bardach 2013, and two times, in Roski 2003, of monitoring on performance respectively, but both paid the health facilities annually.

Individual payment within facilities

How the facilities allocate the payment to individual health workers is an important component, potentially related to the effects of P4P methods. Some payment methods were explicitly described as incentives or bonuses allocated to individual physicians based on their individual performance (Alshamsan 2012; Bardach 2013; Bonfrer 2014a; Lee 2011; Rudasingwa 2015; Serumaga 2011; Soeters 2008), or were equally allocated to individuals (Petersen 2013). In P4P programs in Rwanda and Tanzania (Basinga 2011; Canavan 2008), part of P4P incentives received by facilities was used to increase individual's income, but the allocation criteria were not clear. In a P4P program in Afghanistan (Engineer 2016), all of the P4P incentives received by facilities were used to pay individual health workers, and facility managers decided the allocation criteria. In two P4P programs, facilities did not use the extra payment to reward individual health professionals (An 2008; Yip 2014). Four studies did not provide information on how the facilities allocated P4P payments to individuals (Hillman 1998; Hillman 1999; Roski 2003; Soeters 2011).

Resourcing (if extra funding)

Some P4P programs included the input of additional resources (Alshamsan 2012; An 2008; Bardach 2013; Bonfrer 2014a; Chien 2012; Engineer 2016; Hillman 1998; Hillman 1999; Lee 2011; Petersen 2013; Roski 2003; Rudasingwa 2015; Serumaga 2011; Soeters 2008; Soeters 2011), and the additional resources were paid based on performance. In another two P4P programs (Basinga 2011; Yip 2014), there was no input of additional resources, but adjusting of existing resources from input‐based payment or FFS to P4P.

Study outcomes

We categorised the majority of outcome measures in the included studies into two types: service provision measures and patient outcome measures.

Provision measures included the quantity and quality of service provision. They included the services related to the control of risk factors for chronic diseases, An 2008, Bardach 2013, Petersen 2013, Roski 2003, Serumaga 2011, Hillman 1998, Hillman 1999, and Rudasingwa 2015, and the general outpatient consultations (Yip 2014), for example the rate of smokers referred to a quit line (An 2008), the percentage of hypertension patients prescribed guideline‐recommended medications (Petersen 2013), and the percentage of outpatient visits with an antibiotic prescription (Yip 2014).

Patient outcome measures included patients' utilisation of health services and their intermediate and final health status changes, which could not be entirely controlled by providers. This category of outcome measures covered maternal and children healthcare services, Basinga 2011, Soeters 2008, Soeters 2011, Bonfrer 2014a, Engineer 2016, and Rudasingwa 2015, and the control of risk factors for chronic diseases (Alshamsan 2012; Bardach 2013; Lee 2011; Petersen 2013; Roski 2003; Serumaga 2011), for example the percentage of children aged 12 to 23 months being fully immunised (Basinga 2011), the percentage of general population with cholesterol control (Bardach 2013), the glycated haemoglobin level of diabetic patients (Alshamsan 2012), and the percentage of smokers’ 7‐day sustained abstinence from smoking (Roski 2003).

One study evaluating the effects of capitation compared with FFS also included costs of services as outcome measures, including total inpatient costs and total costs of treating people younger than 18 (Catalano 2000).

All outcome measures reported in the included studies are listed in Table 8.

5. Outcome measures of included studies (for studies included in effects analysis).

| Study | Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes | Unintended or adverse effects | Length of observation | ||

| Provision outcomes | Patient outcomes | Costs | ||||

| Bardach 2013 | Proportion of patients 18 years or older with IVD1 or 40 years or older with DM2 taking aspirin or another antithrombotic therapy (including cilostazol, clopidogrel bisulfate, warfarin sodium, dipyridamole); Proportion of patients 18 years or older identified as current smokers who received certain smoking cessation services (cessation counselling, referral for counselling, or prescription or increased dose of a cessation aid) |

Proportion of patients aged 18 to 75 years with hypertension getting blood pressure control (with blood pressure lower than 140/90 mmHg (if without DM2) or lower than 130/80 mmHg (if with DM2)) (Health); Proportion of male patients 35 years or older and female patients 45 years or older without IVD1 or DM2 who have cholesterol control (total cholesterol lower than 240 mg/dL or low‐density lipoprotein lower than 160 mg/dL measured in the past 5 years) (Health) |

— | — | — | 12 months |

| Petersen 2013 | Proportion of physicians' patients getting the guideline‐recommended antihypertensive medications | Proportion of physicians' patients with blood pressure control or appropriate response to uncontrolled blood pressure (Health) | — | — | Performance of physician groups during the final intervention period to the post‐washout performance period | 24 months |

| Chien 2012 | — | Probability of diabetes patients getting glycated haemoglobin testing (Utilisation); Probability of diabetes patients getting lipid testing (Utilisation); Probability of diabetes patients getting dilated eye exam (Utilisation) |

— | — | — | 12 months |

| Basinga 2011 | Probablity of respondents getting tetanus vaccine during prenatal visit | Probability of respondents having any prenatal care (Utilisation); Probability of respondents having 4 or more prenatal care visits (Utilisation); Probability of respondents having institutional delivery (Utilisation); Probability of children younger than 23 months preventive visit in previous 4 weeks (Utilisation); Probability of children aged 24 to 59 months preventive visit in previous 4 weeks (Utilisation); Probability of children aged 12 to 23 months being fully immunised (Utilisation) |

— | — | — | 23 months |

| Roski 2003 | Percentage of tobacco users identified at last visit; Percentage of smokers who received advice to quit; Percentage of smokers who were offered assistance to quit at last visit |

Percentage of respondents reporting using any aids for smoking cessation (Utilisation); Percentage of respondents reporting using any medication for quitting (Utilisation); Percentage of respondents reporting using any counselling services (Utilisation); Percentage of smoker respondents 7‐day sustained abstinence from smoking (Health); Percentage of respondents being current smokers (7‐day point prevalence); Percentage of respondents reporting intention to quit within 30 days (Health) |

— | — | — | 12 months for provision outcomes; 18 months for patient outcomes |

| Serumaga 2011 | Proportion of patients receiving 0, 1, 2, and 3 or more classes of antihypertensive drugs as a proportion of all study patients | Proportion of patients with blood pressure measured each month (Utilisation); Proportion of patients with controlled blood pressure (blood pressure less than 150/90 mmHg) (Health); Percentage of patients with hypertension‐related adverse outcomes (myocardial infarction, stroke, renal failure, heart failure) or on all‐cause mortality (Health) |

— | — | — | 12 months; 24 months; 36 months |

| An 2008 | Rate of referral of smokers to quit line | Rate of smokers enrolled into quit line (Utilisation) | — | The marginal cost per additional quit line enrollee | — | 10 months |

| Hillman 1999 | Compliance scores3 of providers for immunisation; Compliance scores of providers for other indicators; Overall compliance scores of providers |

— | — | — | — | 6 months; 12 months; 18 months |

| Hillman 1998 | Compliance scores for Pap test; Compliance scores for colorectal screening; Compliance scores for mammography; Compliance scores for breast exam; Total compliance scores |

— | — | — | — | 6 months; 12 months; 18 months |

| Alshamsan 2012 | — | Glycated haemoglobin level for diabetes patients; Total cholesterol level for diabetes patients (Health); Systolic blood pressure for diabetes patients (Health); Diastolic blood pressure for diabetes patients (Health) |

— | — | Ethnic disparities in all outcomes | 12 months; 24 months; 36 months |

| Lee 2011 | — | Total cholesterol level for CHD4 patients (Health); Total cholesterol level for stroke patients (Health); Systolic blood pressure for CHD4 patients (Health); Systolic blood pressure for stroke patients (Health); Systolic blood pressure for hypertension patients (Health); Diastolic blood pressure for CHD4 patients (Health); Diastolic blood pressure for stroke patients (Health); Diastolic blood pressure for hypertension patients (Health) |

— | — | Ethnic disparities in all outcomes | 12 months; 24 months; 36 months |

| Yip 2014 | Percentage of visits with antibiotic prescription in Township Health Centre; Percentage of visits with antibiotic prescription in Village Posts |

— | — | Patient satisfaction score in Township Health Centre; Patient satisfaction score in Village Posts; Total expenditure per visit; Total drug expenditure visit |

Patient volume | — |

| Catalano 2000 | Number of people younger than 18 receiving outpatient services | Number of people younger than 18 receiving inpatient services; Number of people younger than 5 in treatment; Number of disruptive children in treatment; Number of people younger than 18 treated in emergency |

Total outpatient costs; Total costs of treating people younger than 18; Total inpatient costs |

— | — | 12 months 18 months |

| Catalano 2005 | — | Number of emergency visits by adults who had a primary mental or substance use disorder | — | — | — | 12 months |

| Engineer 2016 | — | Percentage of current use of modern family planning methods;

Percentage of at least 1 antenatal checkup from a skilled provider;

Percentage of skilled birth attendant present at latest delivery;

Percentage of postnatal checkup within 42 days of delivery by

a skilled provider;

Percentage of children who received pentavalent 3 vaccination; Concentration index for institutional deliveries; Concentration index for children's utilisation of outpatient services |

— | 20 indicators covering 5 domains of quality of care: Client and community perspectives, including an index of overall client satisfaction and perceived quality of care; Human resources perspectives, including a health worker satisfaction index and health worker motivation index; Physical capacity of health facility inputs (drugs, equipment, infrastructure); Quality of service provision, measuring 4 processes of care; and Management systems | — | 23 to 25 months |

| McLintock 2014 | Percentage of patients on the diabetes register or CHD4 register, or both, for whom case finding, diagnosis, and prescription for depression has been undertaken | — | — | — | Percentage of patients with non‐target long‐term physical conditions for whom case finding for depression, diagnosis, and prescription has been undertaken | 60 months |

1IVD: ischaemic vascular disease 2DM: diabetes mellitus 3Compliance scores: the extent of providers' consistent with the quality assurance criteria 4CHD: coronary heart disease

Excluded studies

Studies that initially appeared to meet the inclusion criteria but that were eventually excluded are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We excluded all of these studies because they did not fulfil the criteria for study design.

Risk of bias in included studies

Our assessment of the risk of bias for each of the included studies can be found in the 'Risk of bias' tables in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Of the eight randomised trials, we assessed one study as at low risk of bias (Bardach 2013). We judged the remaining seven trials as having an unclear risk of bias for all the primary outcomes (An 2008; Engineer 2016; Hillman 1998; Hillman 1999; Petersen 2013; Roski 2003; Yip 2014). One major issue with some of the randomised trials was that the statistical comparison of the characteristics and outcomes of participants at baseline was not done (An 2008; Hillman 1998; Hillman 1999). This is not important for large randomised trials because of the randomised allocation; however, in this review small numbers of health facilities (12 to 143) were randomised.

Basinga 2011 was described as a randomised trial by the authors, but during the study the original randomised allocation of districts was changed. Originally, eight blocks were randomised into two comparison groups, and one group in each block was randomly assigned to the intervention group. However, before implementation of the baseline survey, the administrative district boundaries were redefined by the government in a decentralisation process. As a result, some of the districts selected for this study were combined with districts that already had existing P4P schemes. Consequently, the researchers had to switch the assignment (intervention or control) for eight districts from four blocks, and add one block to the sample. Due to the unclear allocation process and changed allocation, we grouped and analysed this study as a controlled before‐after study. Despite the change of allocation, the intervention and control groups were comparable in terms of the main characteristics and outcomes measured at baseline, so we rated this study as a controlled before‐after study with a low risk of bias.

We assessed five other included controlled before‐after studies as being at high risk of bias (Bonfrer 2014a; Canavan 2008; Rudasingwa 2015; Soeters 2008; Soeters 2011; ). The main issue with these studies was that the control areas had very different characteristics from the intervention areas. Another concern was that there were several different interventions or supports from international donors at the same time the intervention was evaluated (Bonfrer 2014a; Canavan 2008; Rudasingwa 2015; Soeters 2008; Soeters 2011). It was therefore not clear if the effects of the payment interventions were independent of other changes. We included these studies and described their characteristics in this review, but did not use them in analysing intervention effects.

Of seven ITS or repeated measure studies, we assessed one study as having a low risk of bias (Chien 2012), five studies as having an unclear risk of bias (Alshamsan 2012; Catalano 2000; Catalano 2005; Lee 2011; Serumaga 2011), and one study as having a high risk of bias for the primary outcomes (McLintock 2014). Catalano 2000 and Catalano 2005 used different data sources before and after the intervention. Alshamsan 2012, Lee 2011, Serumaga 2011, and McLintock 2014 all used existing medical record databases, and general practitioners' recording of performance measures may have improved in the intervention group (and not in the control group) after the intervention, because the financial incentives for their performance were based on what they recorded.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. P4P plus some existing payment method compared with existing payment method for provision and patient outcomes.

| P4P plus some existing payment method compared with existing payment method for provision and patient outcomes | ||||

|

Patient or population: outpatient health facilities Settings: United States, United Kingdom, Rwanda, Afghanistan Intervention: P4P plus some existing payment method Comparison: existing payment method (capitation or input‐based payment) | ||||

| Outcomes |

Impact: RR for dichotomous outcomes and relative percentage change for continuous outcomes Median (range) |

No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Provision outcomes (prescription of testing or treatment, dichotomous) | The adjusted RR median = 1.095 (ranged from 1.01 to 1.17) | 3 randomised trials and 1 CBA |

Moderate ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

Of 3 randomised trials, 2 were rated as unclear risk of bias, and only 1 was rated as low risk of bias. The certainty was downgraded 1 level because of limitation in study design. |

| Provision outcomes (compliance with quality criteria, continuous) | The adjusted percentage change median = ‐1.345% (ranged from ‐8.49% to 5.8%) | 2 randomised trials |

Moderate ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

2 randomised trials were rated as unclear risk of bias. The certainty was downgraded 1 level because of limitation in study design. |

| Patients' utilisation of health services (dichotomous) | The adjusted RR median = 1.01 (ranged from 0.96 to 1.15) | 3 randomised trials and 1 CBA |

Low ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

3 randomised trials were rated as unclear risk of bias. The certainty was downgraded 1 level because of limitation in study design. The heterogeneity among estimates of effect of different studies was tested, and the certainty was downgraded 1 level because of inconsistency. |

| Patients' health outcomes (dichotomous) | The adjusted RR median = 1.01 (ranged from 0.98 to 1.04) | 1 randomised trial |

Low ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

This trial was rated as unclear risk of bias. In addition, only 1 study targeting small primary health clinics in the United States was included, and the certainty was downgraded 1 level because of indirectness. |

| Provider outcomes | — | 0 | — | |