Abstract

The rhizome of Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge (A. asphodeloides) has been used as a traditional East Asian medicine for the treatment of various types of inflammatory disease. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no systemic studies regarding the molecular mechanisms of action of the A. asphodeloides rhizome anti-inflammatory effects. The aim of the present study was to elucidate the anti-inflammatory effects and underlying mechanism of action of ethanol extracts of the rhizome of A. asphodeloides (EAA) in murine macrophages. Non-cytotoxic concentrations of EAA (10–100 µg/ml) significantly decreased the production of NO and interleukin (IL)-6 in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages, while the production of tumor necrosis factor-α was not regulated by EAA. EAA-mediated reduction of nitric oxide (NO) was due to reduced expression levels of inducible NO synthase (iNOS). Furthermore, protein expression levels of LPS-induced cyclooxygenase-2, another inflammatory enzyme, were alleviated in the presence of EAA. EAA-mediated reduction of those proinflammatory mediators was due to inhibition of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein 1 transcriptional activities followed by the stabilization of inhibitor of κ Bα and inhibition of p38, respectively. These results indicate that EAA suppresses LPS-induced inflammatory responses by negatively regulating p38 and NF-κB, indicating that EAA is a candidate treatment for alleviating inflammation.

Keywords: ethanol extracts, rhizome, Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge, macrophages, inflammatory mediators, p38, nuclear factor-κB

Introduction

Inflammatory responses elicit a host defense to external stimuli, including bacterial contamination. Invasion of pathogens triggers sequential innate immune responses. The main immune cells that act in the innate immune response include neutrophils, dendritic cells and macrophages, whose inflammatory properties involve phagocytic action, antigen presentation, and production of inflammatory mediators (1). In particular, macrophages initiate and maintain inflammation via the production of inflammatory mediators, including nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and proinflammatory cytokines (2). An adequate degree of inflammation rescues the human body from infectious diseases; however, the tight regulation of inflammatory responses is important, as excessive inflammatory responses cause severe inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, atherosclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis (3). Therefore, identifying candidate molecules possessing anti-inflammatory properties is a valuable strategy for the treatment of severe inflammatory states.

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factors are major signaling molecules involved in the regulation of inflammatory mediators (4). NF-κB is a pivotal regulator of inflammation that controls expression of proinflammatory genes (5). AP-1, a heterodimeric protein consisting of members of the Jun and Fos families of DNA-binding proteins, activates cellular processes, such as inflammation, proliferation and apoptosis, by binding to the promoter regions of various genes (6). Thus, AP-1 proteins are recognized as regulators of cytokine expression and important modulators of inflammatory diseases.

Many traditional medicines have been used for the treatment of various inflammatory diseases. Of them, the rhizome of Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge (Asparagaceae) is widely administered as traditional medicine in China, Korea and Japan for the treatment of inflammatory disorders, including fever, coughs, allergies, diabetes, and Alzheimer's disease (7,8). Numerous previous studies support the use of A. asphodeloides for the treatment of various inflammatory disorders. Lee Mo Tang, a mixture of A. asphodeloides and Fritillaria cirrhosa, was reported to exhibit anti-asthmatic effects via the inhibition of ovalbumin-induced eosinophil accumulation and Th2-mediated bronchial hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of asthma (9). Zi Shen Pill, another agent containing A. asphodeloides, exerted effects on benign prostatic hyperplasia via inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor expression in rats (10). Furthermore, methanol extracts of A. asphodeloides were reported to inhibit the binding activity of leukotriene B4 on human neutrophils (11). Certain active components of A. asphodeloides, including anemarsaponin B, broussonin B, mangiferin, and timosaponin AIII, have also been reported to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects in various experimental models, such as models of learning and memory deficits, ear edema and colitis mouse models (12–14).

Despite its traditional uses and many studies on the anti-inflammatory effects of its active components, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies regarding the molecular mechanisms of action of ethanol extracts of A. asphodeloides (EAA). In the current study, the anti-inflammatory effects of EAA and mechanisms of action in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated murine macrophage cells were investigated.

Materials and methods

EAA preparation

A 95% ethanol extract (code no. PBC345AS) of A. asphodeloides was obtained from the Korea Plant Extract Bank (KPEB Daejeon, South Korea). The concentrated ethanol extract was manufactured according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the rhizomes of A. asphodeloides were dried at room temperature (RT), treated with ethanol (GR grade), and sonicated numerous times at 45°C. The extracts were filtrated to remove solid substances and concentrated with reduced pressure at 45°C. A stock solution (200 mg/ml) of the extract was prepared in Sigma-Aldrich dimethoxysulfoxide (DMSO; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and this was stored at −20°C before use.

Cell culture and reagents

RAW 264.7 macrophages, a mouse monocytic cell line and HEK 293 cells, a human embryonic kidney cell line, were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences), 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Rabbit anti-inhibitor of κBα (IκBα; cat. no. sc-371) and mouse anti-α-tubulin (cat. no. sc-5286) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). Rabbit anti-inducible NO synthase (iNOS; cat. no. 2982), anti-cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (cat. no. 4842), anti-p-IκBα (Ser32/36; cat. no. 9246), anti-p38 (cat. no. 9212), anti-p-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182; cat. no. 9211), anti-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK; cat. no. 9102), anti-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK; 9252), anti-p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185; cat. no. 9251) and mouse anti-p-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204; cat. no. 9106) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; cat. no. LF-SA8002) and goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. LF-SA8001) secondary antibodies were purchased from AbFrontier (Young In Frontier Co., Ltd., Seoul, South Korea). Ez-cytox solution was purchased from Daeil Lab (Seoul, South Korea). Ready-SET-Go! ELISA kits for the detection of interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α were obtained from Ebioscience, Inc. (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Measurement of cell viability

RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with EAA (10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 µg/ml) for 2 h and further incubated for 24 h at 37°C in the absence or presence of LPS (1 µg/ml). Following incubation, Ez-cytox solution (one-tenth of the culture medium) was added to each well and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Supernatants were transferred to fresh 96-well plates and the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a Synergy H1 Microplate Reader.

Measurement of NO production

NO production in activated macrophages was measured according to the method described in our previous study (15). Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates (4.0×104 cells/well) and incubated at 37°C overnight. Cells were pretreated with various concentrations of EAA (10, 20, 50 and 100 µg/ml) for 2 h prior to LPS treatment. Following stimulation with LPS (1 µg/ml) for 24 h, the supernatants (100 µl) were transferred to fresh 96-well plates and 100 µl Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% N-1-naphthylenediamine dihydrochloride and 2.5% phosphoric acid) was added to each well. Nitrite standard solution (NaNO2; 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50 and 100 µM) was used to generate a standard curve for calculating the quantity of NO in the supernatants. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm using a Synergy H1 Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (4.0×104 cells/well) and incubated at 37°C overnight. Cells were pretreated with various concentrations of EAA (10, 20, 50 and 100 µg/ml) for 2 h prior to LPS treatment. Subsequent to stimulation with LPS (1 µg/ml) for 24 h, the culture supernatants were collected and diluted according to a predetermined dilution rate for each proinflammatory cytokine. The production of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-α, was measured using Ready-SET-Go! ELISA kits for each type of cytokine, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with coating solution overnight at 4°C, washed with 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/Tween-20 (PBST) three times, and treated with 1X Assay Diluent for 1 h at RT. The wells were emptied and diluted supernatant and standard solutions were added to each well. Following incubation (2 h) at RT, the plates were washed with 1X PBST three times and detection antibody solution diluted in 1X Assay Diluent was added to each well. The plates was washed after 1 h of treatment, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-streptavidin solution was added for 30 min and the plates were washed five times with 1X PBST. Tetramethylbenzidine solution was subsequently added to the plates and they were incubated for 10 min in the dark. Additional 1 N H3PO4 was added to the wells to terminate the reaction and the absorbance in each well was measured using a Synergy H1 Microplate Reader at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Luciferase reporter assays

HEK 293 cells were seeded into a 100-mm dish (70% confluence on the day of transfection) and transfected with pNF-κB-luc or pAP-1-luc cis-reporter plasmids (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), which contains the NF-κB or AP-1 promoters, respectively [gWIZ-green fluorescent protein (GFP; Aldevron, Fargo, ND, USA) served as an internal control for transfection efficiency]. Transfected cells were divided into 12-well plates, incubated at 37°C overnight, and treated with various concentrations of EAA (10, 20, 50 and 100 µg/ml) in the presence of phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA). After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, cells were lysed using cell culture lysis reagent (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) and luciferase activity was measured using luciferin as a substrate. The GFP expression levels were determined using the fluorescence change of excitation at 485 nm and emission at 525 nm.

Preparation of total cell lysates

RAW 264.7 macrophages pretreated with EAA were further stimulated with LPS (1 µg/ml) for the optimal duration for detecting target proteins [IκBα and transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) for 3 min; mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) for 15 min; and iNOS and COX-2 for 24 h]. Following stimulation for the indicated durations, cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS. Lysis buffer (0.5% NP-40, 0.5% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1% glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4) was added to the washed wells and collected into microtubes after 10 min. Following centrifugation at 15,814 × g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatants were prepared in fresh microtubes.

Immunoblot analysis

After boiling the mixture of lysates and sample buffers, aliquots of the samples (20 µg) were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes with transfer buffer [192 mM glycine, 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), and 20% methanol (v/v)] at 100 V for 1 h. After blocking with 5% non-fat dried milk, each membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies (dilution, 1:1,000). Each membrane was then incubated for an additional 1 h with the secondary peroxidase-conjugated IgG antibodies (1:5,000). Subsequent to washing five times with 1X PBST, the target proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence. Protein levels were quantified by scanning of the immunoblots and analysis with LabWorks software 4.6 (UVP, LLC, Upland, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The data are represented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparisons between multiple experimental groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test using GraphPad Prism 3.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. The data from nine replicates were analyzed, including three independent experiments with three replicates in each.

Results

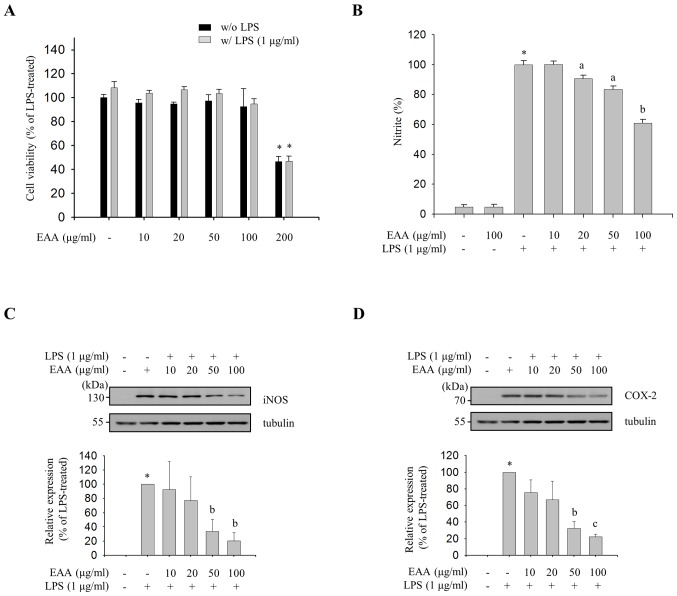

Inhibitory effects of EAA on LPS-induced NO production and expression levels of iNOS and COX-2

As the inhibitory effect of an anti-inflammatory agent should be assessed at concentrations that do not exhibit cytotoxicity, the maximal non-cytotoxic concentration was determined with a cell viability assay. EAA did not exhibit cytotoxicity in concentrations up to 100 µg/ml. However, significant cytotoxicity was observed at 200 µg/ml (Fig. 1A). Thereafter, concentrations of ≤100 µg/ml EAA were used throughout the current study. To evaluate the anti-inflammatory properties of EAA, the effect of EAA on the production of NO, a proinflammatory mediator, was measured in LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells. As shown in Fig. 1B, EAA inhibited LPS-induced NO production in a dose-dependent manner. The results indicate that EAA inhibits LPS-induced NO production in macrophages.

Figure 1.

Effects of EAA on the production of inflammatory mediators. RAW 264.7 macrophages were pre-treated with EAA (10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 µg/ml) for 2 h, and were incubated in the presence or absence of LPS (1 µg/ml) for an additional 24 h. (A) Cell viability was determined using EZ-Cytox solution. Cell viability data are presented as the mean ± SEM and analyzed using one-way ANOVA. *P<0.01 vs. LPS-untreated or -treated control groups. (B) NO levels in the supernatants were measured using Griess reagent. NO levels were calculated with a standard curve using nitrite standard solution (NaNo2). The relative production of NO in the EAA-treated compared with the LPS-treated group is presented as the mean ± SEM and analyzed using one-way ANOVA. *P<0.001 vs. LPS-untreated control groups. aP<0.05 and bP<0.01 vs. LPS-treated groups. Western blot analysis was performed with total cell lysates and the expression levels of (C) iNOS and (D) COX-2 were detected using specific antibodies. The results were normalized to tubulin (loading control). The relative expression of iNOS in the EAA-treated compared with the LPS-treated group is presented as the mean ± SEM and analyzed using one-way ANOVA. *P<0.001 vs. LPS-untreated control groups. aP<0.05, bP<0.01, and cP<0.001 vs. LPS-treated groups. EAA, ethanol extracts of the rhizome of A. asphodeloides; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; SEM, standard error of the mean; ANOVA, analysis of variance; NO, nitric oxide; iNOS, inducible NO synthase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2.

Subsequently, the effect of EAA on the protein expression levels of iNOS, an NO synthesizing enzyme, and COX-2, an enzyme responsible for the production of PGE2, was evaluated in order to investigate the transcriptional regulation of proinflammatory mediators. As shown in Fig. 1C and D, the immunoblot analysis with iNOS- and COX-2-specific antibodies revealed an inhibitory effect of EAA on LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression levels in a dose-dependent manner. These data indicate that NO and PGE2 production are tightly regulated at the protein level by EAA.

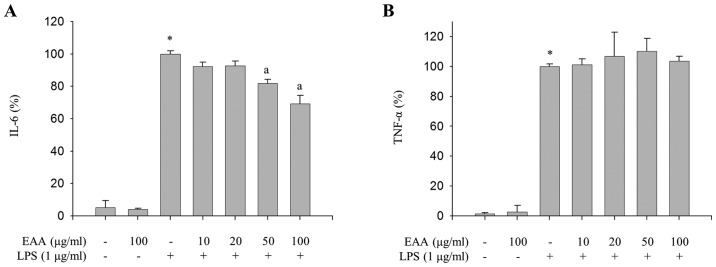

Inhibitory effects of EAA on LPS-induced production of IL-6

As the excessive production of inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, as well as NO and PGE2, in macrophages is accompanied by severe inflammation (16), the effect of EAA on the production of proinflammatory cytokines in LPS-treated RAW 264.7 macrophages were measured to investigate the additional anti-inflammatory properties of EAA. As presented in Fig. 2A, EAA inhibited LPS-induced production of IL-6. However, LPS-induced TNF-α production was not alleviated by EAA (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that EAA inhibits the production of IL-6, whereas TNF-α production is not regulated by EAA in LPS-treated macrophages.

Figure 2.

Inhibitory effects of EAA on the production of proinflammatory cytokines. RAW 264.7 macrophages were pre-treated with EAA (10, 20, 50 and 100 µg/ml) for 2 h, and incubated with LPS for 24 h. IL-6 and TNF-α production in the supernatants were measured using ELISA. Relative production of (A) IL-6 (B) TNF-α in the EAA-treated compared with the LPS-treated group is represented as the mean ± standard error of the mean Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance. *P<0.001 vs. LPS-untreated control groups. aP<0.05 vs. LPS-treated groups. EAA, ethanol extracts of the rhizome of A. asphodeloides; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor.

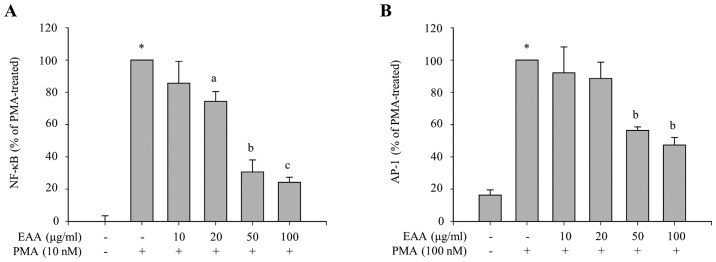

Selective inhibition of the NF-κB and p38 pathways by EAA

To identify which transcription factors are involved in the inhibitory effects of EAA on the production of proinflammatory mediators, the transcriptional activities of NF-κB and AP-1, major transcription factors in the inflammatory responses, were measured using luciferase reporter assays. HEK 293 cells were treated with various concentrations of EAA in the presence of PMA, which induces transcriptional activation of NF-κB- or AP-1-dependent genes. The luciferase reporter gene is placed under the control of NF-κB or AP-1 transcriptional activity. As presented in Fig. 3A and B, PMA-induced luciferase activities, which are regulated by NF-κB or AP-1 transcription factor, respectively, were reduced by EAA treatment. This indicates that EAA exerts anti-inflammatory responses via the inhibition of NF-κB and AP-1 transcriptional activities.

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effects of EAA on the transcriptional activation of NF-κB and AP-1. HEK 293 cells were transfected with (A) pNF-κB-luc or (B) pAP-1-luc cis-reporter plasmids and gWIZ-green fluorescent protein. Transfected cells were pre-treated with EAA (10, 20, 50 and 100 µg/ml) for 2 h and then incubated with PMA (10 nM for NF-κB-luc and 100 nM for AP-1-luc) for 24 h. Cells were lysed, and luciferase activity and fluorescence intensity were measured. Luciferase activity of each group was calculated by applying the fluorescence intensity values as internal controls for transfection efficiency. Relative luciferase activity compared to the PMA-treated group is presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.001 vs. PMA-untreated control groups. aP<0.05, bP<0.01, and cP<0.001 vs. PMA-treated groups. EAA, ethanol extracts of the rhizome of A. asphodeloides; nuclear factor-κB; AP-1, activator protein 1; PMA, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate.

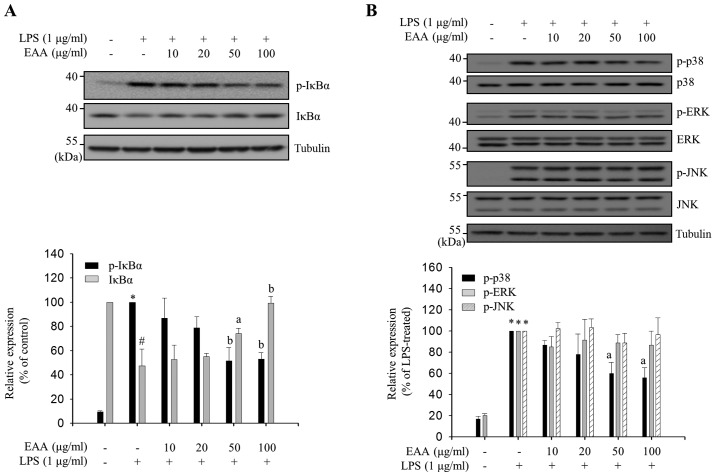

LPS-induced NF-κB activation in macrophages is predominantly mediated by IκBα phosphorylation at Ser-32/36, followed by IκBα degradation and the translocation of released cytoplasmic p50 and p65 complex to the nucleus (17). Phosphorylation in the activation loops of MAPKs leads to their activation, which results in transcriptional activation of AP-1, a transcription factor that binds to the promoter regions of inflammatory mediator genes (4). EAA-mediated IκBα phosphorylation levels in LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells were measured to assess whether EAA regulates NF-κB activation. The p-IκBα levels were reduced and the IκBα levels were increased by EAA treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A), indicating that EAA inhibits IκBα phosphorylation at Ser-32/36 and, thus, reduces degradation of IκBα. Subsequently, the phosphorylation levels in the activation loops of three MAPKs (ERK, JNK and p38) were measured by EAA in LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells. As shown in Fig. 4B, EAA selectively inhibits the phosphorylation of p38 without altering the total p38 levels, whereas ERK and JNK phosphorylation was not regulated by EAA. These results indicate that EAA exhibits its anti-inflammatory properties in macrophages by inhibiting the activation of the major inflammatory signaling pathways, NF-κB and p38.

Figure 4.

Inhibitory effects of EAA on inflammatory signaling pathways. RAW 264.7 macrophages were pre-treated with EAA (10, 20, 50 and 100 µg/ml) for 2 h, and incubated with LPS (1 µg/ml) for the indicated times. Total cell lysates were prepared following LPS stimulation for (A) 3 and (B) 15 min. Western blot analysis was performed using the appropriate antibodies. The expression levels and phosphorylation levels of IκBα, p38, ERK and JNK were measured using enhanced chemiluminescence solutions. The results are presented following normalization to endogenous tubulin level. the relative IκBα level compared with the non-treated group and p-IκBα, p-p38, p-ERK and p-JNK levels compared with the LPS-treated group are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance. #P<0.01 and *P<0.001 vs. LPS-untreated control groups. aP<0.05 and bP<0.01 vs. LPS-treated groups. EAA, ethanol extracts of the rhizome of A. asphodeloides; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IκBα, inhibitor of κBα; ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; p, phosphorylated.

Discussion

iNOS triggers its effector molecule, NO, which is a free radical that is synthesized from l-arginine and results in cellular damage at sites of inflammation (18). COX-2 catalyzes the production of PGE2 from the lipid arachidonic acid, which ultimately induces inflammation and fever (19). However, improper upregulation of iNOS and COX-2 by proinflammatory stimuli has been associated with the pathophysiology of certain types of inflammatory disorders, including sepsis and arthritis (20). Numerous studies have demonstrated that natural products that inhibit iNOS and COX-2 expression levels could be valuable phytomedicines for the treatment of severe inflammatory states (21–23). In the present study, it was demonstrated that EAA attenuates LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression levels in RAW264.7 macrophages without causing cytotoxic effects (Fig. 1). These results indicate that EAA is a promising candidate for an anti-inflammatory phytomedicine.

In addition to iNOS and COX-2, activated macrophages produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 (24). These proinflammatory cytokines stimulate an increase in blood flow and permeability of capillaries, lead to infiltration of immune cells and cause inflammatory responses (24). Notably, EAA reduced the production of IL-6, but not TNF-α, in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages (Fig. 2), indicating that EAA may suppress LPS-induced inflammation by selectively inhibiting IL-6 expression levels. IL-6 has a vital role in the earliest stages of inflammation; when its activation persists, acute inflammation becomes chronic inflammation (25). Furthermore, IL-6 is an endogenous mediator of LPS-induced fever (26). Therefore, selective inhibition of IL-6 production by EAA may alleviate the acute response to LPS, thereby reducing LPS-induced inflammation.

In the current study, EAA suppressed LPS-induced phosphorylation of IκBα and p38 (Fig. 4), although it did not affect ERK and JNK phosphorylation. Selective regulation of major inflammatory signal transductions by EAA may be accomplished by targeting individual kinases upstream of NF-κB and MAPK. LPS binding to toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on the surface of macrophages leads to the recruitment of accessory molecules and subsequent activation of TAK1, an upstream kinase that regulates NF-κB and MAPK signal transduction (27). Following TAK1 activation, NF-κB is regulated by IκB kinases (IKKs), and each MAPK is activated by its specific upstream kinase (27). Therefore, EAA may selectively regulate NF-κB and p38 or their specific upstream kinases, IKKs and MKK3/6, respectively, but not TAK1 or TLR4 accessory molecules.

In conclusion, the current results indicate that EAA may serve as a potent anti-inflammatory phytomedicine via the inhibition of NF-κB and p38, and subsequent production of inflammatory mediators, including iNOS, COX-2 and IL-6. Although the current study clarified the anti-inflammatory effects of EAA and its underlying mechanisms of action in murine macrophages, further studies using experimental animal models of inflammation are required to provide further support of EAA as a valuable candidate for the treatment of severe inflammatory states.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2016R1A6A3A11931134).

References

- 1.Nowarski R, Gagliani N, Huber S, Flavell RA. Innate immune cells in inflammation and cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1:77–84. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu LC, Fan NC, Lin MH, Chu IR, Huang SJ, Hu CY, Han SY. Anti-inflammatory effect of spilanthol from Spilanthes acmella on murine macrophage by down-regulating LPS-induced inflammatory mediators. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:2341–2349. doi: 10.1021/jf073057e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutolo M. Macrophages as effectors of the immunoendocrinologic interactions in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;876:32–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adcock IM. Transcription factors as activators of gene transcription: AP-1 and NF-kappa B. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 1997;52:178–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: The control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wisdom R. AP-1: One switch for many signals. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:180–185. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SY, Choi YH, Lee W. Dangnyohwan improves glucose utilization and reduces insulin resistance by increasing the adipocyte-specific GLUT4 expression in Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;115:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Dan Y, Yang D, Hu Y, Zhang L, Zhang C, Zhu H, Cui Z, Li M, Liu Y. The genus Anemarrhena Bunge: A review on ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;153:42–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeum HS, Lee YC, Kim SH, Roh SS, Lee JC, Seo YB. Fritillaria cirrhosa, Anemarrhena asphodeloides, Lee-Mo-Tang and cyclosporine a inhibit ovalbumin-induced eosinophil accumulation and Th2-mediated bronchial hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of asthma. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;100:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun H, Li TJ, Sun LN, Qiu Y, Huang BB, Yi B, Chen WS. Inhibitory effect of traditional Chinese medicine Zi-Shen Pill on benign prostatic hyperplasia in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;115:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HJ, Ryu JH. Hinokiresinol: A novel inhibitor of LTB4 binding to the human neutrophils. Planta Med. 1999;65:391. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia D, Delgado R, Ubeira FM, Leiro J. Modulation of rat macrophage function by the Mangifera indica L. extracts Vimang and mangiferin. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:797–806. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(02)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JY, Shin JS, Ryu JH, Kim SY, Cho YW, Choi JH, Lee KT. Anti-inflammatory effect of anemarsaponin B isolated from the rhizomes of Anemarrhena asphodeloides in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages is mediated by negative regulation of the nuclear factor-kappaB and p38 pathways. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:1610–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu WQ, Qiu Y, Li TJ, Tao X, Sun LN, Chen WS. Timosaponin B-II inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine induction by lipopolysaccharide in BV2 cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2009;32:1301–1308. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1916-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho YC, Ju A, Kim BR, Cho S. Anti-inflammatory effects of Crataeva nurvala Buch. Ham. are mediated via inactivation of ERK but not NF-κB. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;162:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feghali CA, Wright TM. Cytokines in acute and chronic inflammation. Front Biosci. 1997;2:d12–d26. doi: 10.2741/A171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karin M, Delhase M. The I kappa B kinase (IKK) and NF-kappa B: Key elements of proinflammatory signalling. Semin Immunol. 2000;12:85–98. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connelly L, Palacios-Callender M, Ameixa C, Moncada S, Hobbs AJ. Biphasic regulation of NF-kappa B activity underlies the pro- and anti-inflammatory actions of nitric oxide. J Immunol. 2001;166:3873–3881. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuccurullo C, Mezzetti A, Cipollone F. COX-2 and the vasculature: Angel or evil? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2007;9:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s11906-007-0013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asehnoune K, Strassheim D, Mitra S, Kim JY, Abraham E. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in Toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation of NF-kappa B. J Immunol. 2004;172:2522–2529. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camacho-Barquero L, Villegas I, Sánchez-Calvo JM, Talero E, Sánchez-Fidalgo S, Motilva V, Alarcón de la Lastra C. Curcumin, a Curcuma longa constituent, acts on MAPK p38 pathway modulating COX-2 and iNOS expression in chronic experimental colitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Mediavilla V, Crespo I, Collado PS, Esteller A, Sánchez-Campos S, Tuñón MJ, González-Gallego J. The anti-inflammatory flavones quercetin and kaempferol cause inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2 and reactive C-protein, and down-regulation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway in Chang Liver cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiwari M, Dwivedi UN, Kakkar P. Tinospora cordifolia extract modulates COX-2, iNOS, ICAM-1, pro-inflammatory cytokines and redox status in murine model of asthma. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;153:326–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sweet MJ, Hume DA. Endotoxin signal transduction in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:8–26. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gabay C. Interleukin-6 and chronic inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(Suppl 2):S3. doi: 10.1186/ar1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LeMay LG, Vander AJ, Kluger MJ. The effects of pentoxifylline on lipopolysaccharide (LPS) fever, plasma interleukin 6 (IL 6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in the rat. Cytokine. 1990;2:300–306. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(90)90032-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]