Abstract

Analysing child mortality may enhance our perspective on global achievements in child survival. We used data from surveillance sites in Bangladesh, Nicaragua and Vietnam and Demographic Health Surveys in Rwanda to explore the development of neonatal and under‐five mortality. The mortality curves showed dramatic reductions over time, but child mortality in the four countries peaked during wars and catastrophes and was rapidly reduced by targeted interventions, multisectorial development efforts and community engagement.

Conclusion: Lessons learned from these countries may be useful when tackling future challenges, including persistent neonatal deaths, survival inequalities and the consequences of climate change and migration.

Keywords: Child mortality, Migration, Natural catastrophes, Sustainable Development Goals, War

Key notes.

This review analysed child mortality in different settings to examine global achievements in child survival

It found that child mortality in Bangladesh, Nicaragua, Rwanda and Vietnam peaked during wars and catastrophes and was rapidly reduced by targeted interventions, multisectorial development efforts and community engagement

The lessons learned may be useful for tackling future challenges, such as persistent neonatal deaths, survival inequalities and the consequences of climate change and migration

Introduction

In September 2000, the largest gathering of world leaders in history adopted the United Nations’ Millennium Declaration, committing their countries to a new global partnership to reduce extreme poverty by 2015.

At the end of the Millennium Development Goal era, reports assessed the progress that had been made and the challenges that remained. Extreme poverty had been halved, and global mortality in children below five years of age had dropped from 90 per 1000 live births in 1990 to 43 per 1000 in 2015 1, 2. This review focuses on four examples of child survival development that underpinned this global progress. These cases emanated from countries with impressive improvements in child survival: Bangladesh, Nicaragua, Rwanda and Vietnam. Authors from these four countries, and Sweden, have worked together on different collaborative child survival projects over the past few decades. The aim of this review was to describe the development of child mortality in these settings over recent decades and to reflect on the possible mechanisms behind the progress that took place against a background of war, catastrophes and human suffering.

The four settings and the data sources from Bangladesh, Nicaragua, Rwanda and Vietnam are presented in the Appendix.

Child survival patterns

A first look at the mortality graphs may give the impression of bedside body temperature curves of febrile children, who successfully recover, with dramatic peaks, rapid changes and large differences between the high initial levels and the lower levels towards the end of the study periods (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

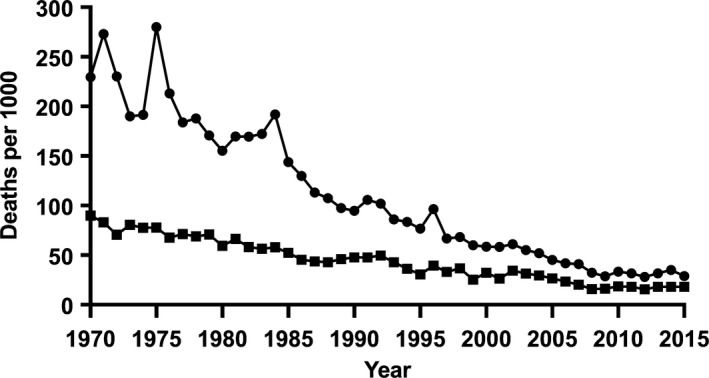

Figure 1.

The under‐five mortality rate (circles) and the neonatal mortality rate (squares) in Matlab, Bangladesh, 1970–2015.

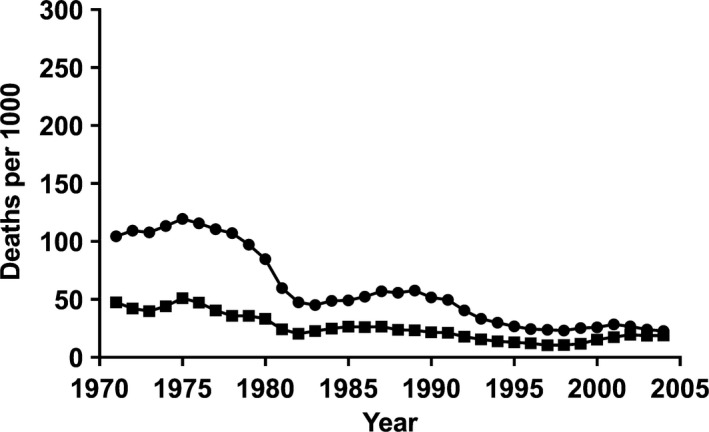

Figure 2.

The under‐five mortality rate (circles) and the neonatal mortality rate (squares) in León, Nicaragua, 1970–2005.

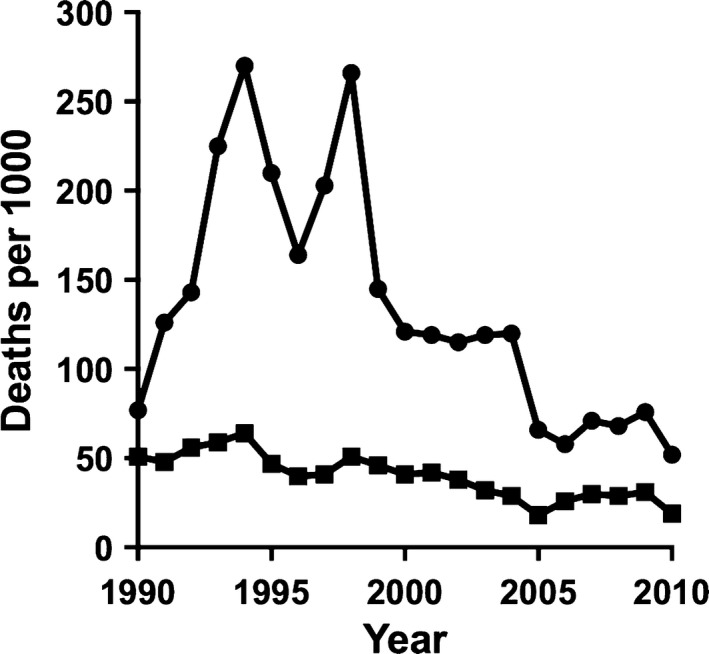

Figure 3.

The under‐five mortality rate (circles) and the neonatal mortality rate (squares) in Rwanda, 1990–2010.

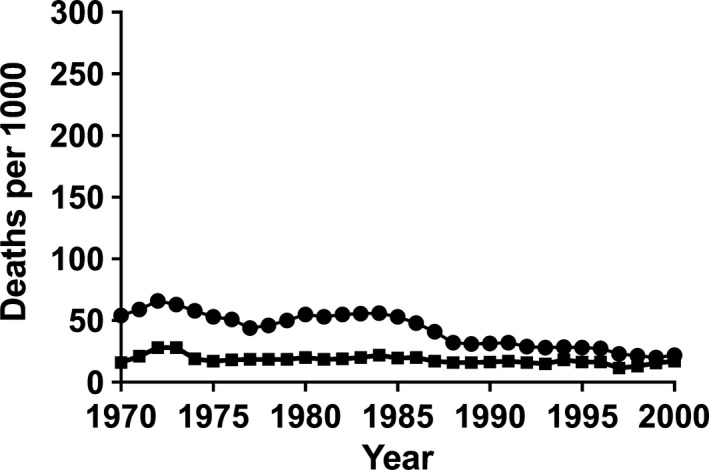

Figure 4.

The under‐five mortality rate (circles) and the neonatal mortality rate (squares) in Ba Vi, Vietnam, 1970–2000.

In 1970, the mortality of children under the age of five years in Matlab, Bangladesh, was above 200 per 1000 live births (Fig. 1). Higher peaks followed at the time of the 1971 liberation war and the 1974 flooding and famine. A Shigella outbreak in 1984 led to a high death toll among children. From the late 1980s, comprehensive maternal and child health services, including door‐step family planning services and adequate immunisation coverage, resulted in great improvements in child survival 3. Within the time window of the Millennium Development Goals from 1990 to 2015, the targeted two‐third reduction in under‐five mortality was reached.

The Nicaraguan story starts with an under‐five mortality level of around 100 per 1000 live births (Fig. 2). There were, in spite of an overall downward trend, some increases in mortality at the time of the liberation from the Somoza dictatorship in 1979 and during a period of the US‐backed Contras war in the following decade. At the end of the study period in 2005, the under‐five mortality rate was approaching 20 per 1000 4, 5.

Rwanda's under‐five mortality level in 1990 was estimated to be around 80 per 1000 live births, but the 1994 genocide tripled this figure (Fig. 3) 6. Immediate efforts to improve security and international assistance reduced the child mortality in the postgenocide period. A second peak in the late 1990s coincided with the withdrawal of some of the international support and a temporary reintroduction of user fees in the health service. A number of initiatives such as the millennium efforts to achieve universal coverage of essential maternal and child health services and targeted interventions aimed at vulnerable groups – combined with multisectorial development investment – resulted in an under‐five mortality rate of around 50 per 1000 in 2010 6.

The Vietnam data from the Red River delta area showed an under‐five mortality rate of around 50 per 1000 in 1970 (Fig. 4). President Nixon's order to restart and intensify bombings over the north of Vietnam in December 1972 almost doubled the mortality rate of newborn infants, as the bombardment made it difficult to access perinatal health services 7. At the end of the war in 1975, the under‐five mortality rate had reduced. However, the following years were characterised by limited rice production, an economic crisis and increased poverty and were accompanied by higher mortality rates in children. The expansion of the immunisation programme and other vertical interventions in the early 1980s, and the doi moi reforms that aimed to create a market economy from the mid‐1980s, resulted in a rapid decrease in under‐five mortality rates.

The neonatal mortality level was consistent over the three decades – 1970 to 2000 – covered by the Ba Vi data from Vietnam (Fig. 4). These recorded deaths during the first 28 days of life have frequently been invisible in official statistics in low‐income settings 8, 9. The Millennium Development Goal agenda did not include a neonatal mortality target from the start 10. Births are often not officially counted until it is evident that the newborn child is surviving. The families may not approach the local authorities for a birth certificate for one to a few months, and the deaths of young infants are frequently missing from the official data.

A continuum of good healthcare for all pregnant and delivering women and their children is needed to cope with perinatal health problems and prevent deaths 11, 12. Examples from other countries illustrate the difficulties in reducing the number of deaths during the first month of life in comparison to postneonatal health problems. Perinatal health concerns cannot be managed by vertical approaches, such as vaccinations, or single standardised treatments such as oral rehydration therapy. They require health system approaches with good coverage, quality and continuity 13.

Wars, catastrophes and mortality

The four countries we focus on in this review show, with terrifying clarity, how children become victims of wars and catastrophes. In the years before the genocide in Rwanda, the political turmoil and suffering of the population had already resulted in increasing under‐five mortality (Fig. 3). We also observed rapidly increasing child mortality in Somalia, whose society was collapsing before the onset of war. The dominating causes of death in such situations are preventable and treatable, namely diarrhoea, pneumonia, and other vaccine preventable diseases 14. The Rwanda example also illustrates a scary new phenomenon that continues to be reported from several conflict countries: children become specific targets in armed conflicts 15.

Usually, the youngest infants are relatively protected from the consequences of war and unrest. The high peaks of mortality in Bangladesh in the early 1970s (Fig. 1) and in Rwanda in the 1990s (Fig. 3) were not accompanied by corresponding increases in neonatal mortality. The data from the war in Vietnam in the early 1970s were an exception (Fig. 4). Bombing prevented access to perinatal health services, mothers had to deliver without skilled attendance and an increased death toll was seen among newborns infants 7.

There was a remarkable reduction in under‐five mortality in the Nicaraguan data starting when the Somoza dictatorship fell in 1979 and continuing throughout the following decade, despite the US‐backed Contras war (Fig. 2). People were mobilised by literacy and vaccination campaigns, and primary healthcare was expanded into rural areas that previously had no access to health services. Under‐five mortality was reduced by half during this period of war and unrest 4.

The Bangladesh 1974 famine caused many deaths, shown in the high peak of mortality after the neonatal period (Fig. 1). It should be noted that even children conceived or born at the time of the famine continued to have increased mortality risks during the first few years of life 16. There is also accumulating evidence of chronic disease risks associated with intrauterine exposure to famine, as demonstrated by studies of the Dutch famine in 1944–1945 17, the Chinese famine in 1959–1961 18 and the Biafra famine in 1968–1970 19.

Health sector reforms, multisectorial development and mortality

Which characteristics of a successful health system performance have resulted in reduced child mortality? The Nicaraguan experiences from the revolution and the Contras war, tell us that even a few targeted and prioritised preventive and curative interventions delivered by motivated primary care workers can be successful if there is high child mortality 4. Essential health services were made available free of charge to previously underserved parts of the population, resulting in a dramatic improvement in child survival during a period of war and unrest 4. The improved education levels of girls and women also contributed substantially to the improvement in child health and survival 5, 20.

From the end of the 1990s, the Rwandan Government initiated a series of health system reforms. These built on the experiences of other countries, but were innovative in how they adapted and combined approaches to strengthen all the building blocks of the health system 6. New additional services were piloted, documented, published and – after modifications – scaled up in the system. These included interventions by community health workers, performance‐based finance and health insurance. The combination of the interventions and their comprehensive coverage were part of the success story 21. The health system reforms were also combined with developmental initiatives in other sectors of society, to enhance equity and eradicate poverty 6.

The Matlab achievements in child survival should be related to the high coverage of essential health services in combination with socio‐economic development efforts 22, 23. In this subdistrict of Bangladesh, as in all parts of the country, the national development organisation BRAC has been running development activities, including micro‐credit programmes and educational activities. A population‐based analysis of these activities and child mortality data from Matlab illustrate the benefits that development activities focused on women have had on child survival 23. Several innovative interventions in Bangladesh have also proven to be effective and been scaled up to national programmes with high coverage and effects. One such example is the doorstep delivery of family planning, which was developed and evaluated in Matlab and later implemented throughout the whole country. This programme has had huge effects on demography, women's health and child survival 3. Another example is the oral rehydration therapy that was developed by the researchers in Dhaka. This intervention was evaluated in clinical and population‐based studies before being scaled up nationally and globally. Millions of lives have been saved, and there is still large potential to save more children using this simple solution 24.

Community engagement and child survival

The Matlab experience of rapidly improving child survival illustrates the progress made in the whole of Bangladesh. The remarkable education achievements, the progress in gender equity, sustained fertility reduction, improved child survival and the reductions in maternal mortality have been labelled the Bangladesh paradox 25. These advancements are in contrast to a continued burden of infectious diseases, malnutrition, poverty and a fragile political system. Several factors may explain the progress, for example an engaged civil society with powerful nongovernmental organisations, an equity orientation in development efforts, increasing proportions of educated women and a skilled cadre of female community health workers.

The Bangladesh community health workers including those called Shasthya Shebikas have been potent agents for achieving almost universal immunisation coverage, the world's highest coverage of oral rehydration therapy use, the success of the family planning programme 26 and successful experiments that provide community‐based management for sick newborn infants 27. Community health workers appear in different guises and may deliver impressive results if they are given well‐defined tasks and are properly trained and supervised, remunerated and integrated into a functioning health system 28. The Brigadistas of Nicaragua, who were community volunteers, immunised, treated dehydration and pneumonia and saved child lives during the time of war 4. The Binome and other categories of community health workers in Rwanda have been judged to have played a significant role in the country's progress in child survival 21, 29.

Community engagement for maternal and child health was an important ingredient in all four country examples. In Vietnam, as well as in other Asian countries, intervention studies have shown that participatory approaches to community engagement can solve some of the local problems that threaten perinatal survival and thereby reduce neonatal mortality and increase equity in survival 30, 31, 32, 33. A number of organisations have played important roles in the child health revolutions in these countries, including the civil society and nongovernmental organisations in Bangladesh 23, the strong Women's Union in Vietnam 30 and communities that have engaged in development and welfare in Rwanda 6.

Future challenges

As illustrated in all four countries, increasing proportions of deaths under the age of five occurred during the first month of life (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4). In the Nicaragua and Vietnam settings with the lowest under‐five mortality levels, more than three‐quarters were neonatal deaths at the end of the study period. In Bangladesh, a half took place during the first month of life, while in Rwanda – with an under‐five mortality level of around 50 per 1000 – slightly more than a third was due to neonatal mortality. The global research and advocacy for improved child survival that took place after the Millennium shift was mainly giving priority to postneonatal and child health problems 34 and the potential for change by a series of cost‐effective, evidence‐based interventions 35. Later, more emphasis was given to neonatal deaths 10 and the strategies to prevent these by establishing a continuum of maternal and newborn care 36. The huge problem of preventable fresh stillbirths in low‐income settings has now been added to the agenda 37. As with neonatal deaths, there is an urgent need to identify and register these cases to identify the problems 38.

The Nicaraguan graph shows the lowest population‐based figure of neonatal mortality for some years in the mid‐1990s (Fig. 2). This low level reflected quality improvements in maternal and neonatal services in the regional hospital in León, which lowered the hospital‐based early neonatal mortality rate from 56 to 11 per 1000 live births over the course of a few years 39. The improved survival was the result of a participatory process, including all staff, which identified and acted upon fundamental problems related to the separation of the mother and baby, hygiene, temperature control, feeding and invasive procedures. The later increase in neonatal mortality, when almost all of the women in the area delivered their babies at the hospital, may again be due to problems in the quality of care. Such tendencies of increasing time trends in neonatal mortality, when more women delivered at health institutions, were also seen in the Vietnam data (Fig. 4). It is not sufficient just to increase the number of institutional deliveries, resources must also be made available to maintain and improve the quality of perinatal care that the health centre or hospital can offer 40.

It has been reported that rapid progress in child health outcomes can increase health inequities 41, but that is not always the case. The investments in health during the Nicaraguan revolution prioritised the underserved rural population and the poorer segments of society, resulting in a reduced social gap in child survival 4. Similarly, the pro‐poor investments in health in Rwanda not only lowered under‐five mortality, but also increased equity in survival 6. Towards the end of the Millennium Development Goal era, the global community identified the need to monitor the social distribution in the coverage of interventions and effects on outcomes, such as under‐five mortality, as well as the averages in process and outcome indicators 42. Abolishing inequity is not just fair in terms of considering the rights of the child, it is a prerequisite for poverty reduction and the continued reduction of child deaths 43.

Matlab, Bangladesh, is one of the areas in the world where the consequences of climate on its inhabitants are visible. The increasing flooding of the area, the erosion along the river banks, the villages that are taken by the rivers and the people that have no option but to live in the slums in Dhaka when they have lost their land 25. The surveillance systems have shown that the frequency and magnitude of extreme weather have been associated with the occurrence of childhood diarrhoea 44.

An equity lens should not only be used to visualise gender differences and socio‐economic gaps in child health 41. In some parts of the world, urban–rural differences are increasing, with the urban poor often living in the huge slum settlements of the mega cities in Asia, Africa and Latin America 45. In such settings, innovative approaches are needed to engage the urban poor communities in the provision of low‐cost, high‐quality maternal and child health services 46.

The eight Millennium Development Goals had a strong focus on health, with maternal and child health and survival represented by two separate goals. The world has now committed itself to reaching 17 Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, and there is only one specific health goal, number three, that focuses on good health and wellbeing, 47. On the one hand, this change in focus may threaten further progress if the previous achievements are forgotten and not sustained 48, 49. On the other hand, it may lead to a positive paradigm shift towards prevention and extensive multisectorial efforts that target poverty alleviation and improved health and welfare 47. Rwanda is one of the countries with a very clear agenda for the years to come, not only in poverty alleviation, but in building systems for further advancements in health 50. The Sustainable Development Goal 2030 Agenda integrates poverty, health and welfare perspectives with the need to counteract climate change and achieve peace and planetary stability, which may be the greatest prerequisites for continued improvements in child survival in the years to come 51.

Funding

There was no external funding for this review.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Bangladesh

The Matlab Health and Demographic Surveillance System was established in 1966 and includes a 220 000 rural population in the delta area 50 km south of the capital, Dhaka 52, 53. The data used for this paper covered the period 1970–2015. The under‐five mortality rate is shown for the entire population up to 1978 and thereafter for the 110 000 population area, where the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research provides selected health services, including the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases and maternal and child health services. The Matlab subdistrict is representative of the rice‐cultivating delta area of Bangladesh.

Nicaragua

The Nicaraguan data were derived from the Health and Demographic Surveillance System in the city and surrounding countryside of León, a university town north of the capital, Managua 4, 5, 54. The study period covered 1970–2005. The surveillance sample included a population of around 55 000 inhabitants in 11 000 households. The surveillance system was established in 1993, followed by repeated updates that provided information on births, deaths and migration in the study area 54. Retrospective reproductive life interviews with women aged 15–49 years in 1993 formed the basis for the analysis of earlier births and deaths. The area is relatively typical for the more densely populated western part of Nicaragua towards the Pacific coast.

Rwanda

The Rwanda data emanated from three consecutive Rwandan Demographic and Health Surveys conducted in 2000, 2005 and 2010 6. These data were representative of the whole of Rwanda. In sampled households, 35 413 women aged 15–49 years were interviewed. The analysis covered the period from January 1990 to December 2010. The weighted sample size was 15 198 births in the 2000 survey, 8753 in 2005 and 10 848 in 2010.

Vietnam

The Vietnam data come from the Health and Demographic Surveillance System in the Ba Vi District, a rural area situated 70 km west of Hanoi. The district includes lowland and highland areas and some islands in the Red River Delta. The area is representative of the northern parts of Vietnam regarding geography, demography, disease pattern and administrative structure 7. It provided the retrospective reproductive life experiences of 14 329 women aged 15–54 years, including 26 796 live births, and covered the period 1970 to 2000.

References

- 1. You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S, Idele P, Hogan D, Mathers C, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under‐5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario‐based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Inter‐agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Lancet 2015; 386: 2275–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. United Nations . The millennium development goals report 2015. New York, NY, USA: United Nations, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joshi S, Schultz TP. Family planning and women's and children's health: long‐term consequences of an outreach program in Matlab, Bangladesh. Demography 2013; 50: 149–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peña R, Liljestrand J, Zelaya E, Persson LÅ. Fertility and infant mortality trends in Nicaragua 1964–1993. The role of women's education. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999; 53: 132–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pérez W, Eriksson L, Blandón EZ, Persson LÅ, Källestål C, Peña R. Comparing progress toward the millennium development goal for under‐five mortality in León and Cuatro Santos, Nicaragua, 1990–2008. BMC Pediatr 2014; 14: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Musafili A, Essén B, Baribwira C, Binagwaho A, Persson LÅ, Selling KE. Trends and social differentials in child mortality in Rwanda 1990–2010: results from three demographic and health surveys. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015; 69: 834–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoa DP, Nga NT, Målqvist M, Persson LÅ. Persistent neonatal mortality despite improved under‐five survival: a retrospective cohort study in northern Vietnam. Acta Paediatr 2008; 97: 166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Målqvist M, Eriksson L, Nguyen TN, Fagerland LI, Dinh PH, Wallin L, et al. Unreported births and deaths, a severe obstacle for improved neonatal survival in low‐income countries; a population based study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2008; 8: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huy TQ, Johansson A, Long NH. Reasons for not reporting deaths: a qualitative study in rural Vietnam. World Health Popul 2007; 9: 14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet 2005; 365: 891–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Målqvist M, Nga NT, Eriksson L, Wallin L, Ewald U, Persson L‐AÅ. Delivery care utilisation and care‐seeking in the neonatal period: a population‐based study in Vietnam. Ann Trop Paediatr 2008; 28: 191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Målqvist M, Sohel N, Do TT, Eriksson L, Persson LÅ. Distance decay in delivery care utilisation associated with neonatal mortality. A case referent study in northern Vietnam. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kerber KJ, de Graft‐Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, Okong P, Starrs A, Lawn JE. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet 2007; 370: 1358–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ibrahim MM, Omar HM, Persson LA, Wall S. Child mortality in a collapsing African society. Bull World Health Organ 1996; 74: 547–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shenoda S, Kadir A, Goldhagen J. Children and armed conflict. Pediatrics 2015; 136: e309–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Razzaque A, Alam N, Wai L, Foster A. Sustained effects of the 1974–75 famine on infant and child mortality in a rural area of Bangladesh. Popul Stud (Camb) 1990; 44: 145–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roseboom TJ, Painter RC, van Abeelen AFM, Veenendaal MVE, de Rooij SR. Hungry in the womb: what are the consequences? Lessons from the Dutch famine Maturitas 2011; 70: 141–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fan W, Qian Y. Long‐term health and socioeconomic consequences of early‐life exposure to the 1959–1961 Chinese Famine. Soc Sci Res 2015; 49: 53–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hult M, Tornhammar P, Ueda P, Chima C, Bonamy A‐KE, Ozumba B, et al. Hypertension, diabetes and overweight: looming legacies of the Biafran famine. PLoS ONE 2010; 5: e13582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peña R, Wall S, Persson LA. The effect of poverty, social inequity, and maternal education on infant mortality in Nicaragua, 1988–1993. Am J Public Health 2000; 90: 64–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sayinzoga F, Bijlmakers L. Drivers of improved health sector performance in Rwanda: a qualitative view from within. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hale L, DaVanzo J, Razzaque A, Rahman M. Why are infant and child mortality rates lower in the MCH‐FP area of Matlab, Bangladesh? Stud Fam Plann 2006; 37: 281–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bhuiya A, Chowdhury M. Beneficial effects of a woman‐focused development programme on child survival: evidence from rural Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med 2002; 55: 1553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sabot O, Schroder K, Yamey G, Montagu D. Scaling up oral rehydration salts and zinc for the treatment of diarrhoea. BMJ 2012; 344: e940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chowdhury AMR, Bhuiya A, Chowdhury ME, Rasheed S, Hussain Z, Chen LC. The Bangladesh paradox: exceptional health achievement despite economic poverty. Lancet 2013; 382: 1734–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. El Arifeen S, Christou A, Reichenbach L, Osman FA, Azad K, Islam KS, et al. Community‐based approaches and partnerships: innovations in health‐service delivery in Bangladesh. Lancet 2013; 382: 2012–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baqui AH, El Arifeen S, Darmstadt GL, Ahmed S, Williams EK, Seraji HR, et al. Effect of community‐based newborn‐care intervention package implemented through two service‐delivery strategies in Sylhet district, Bangladesh: a cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 371: 1936–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, Rowe AK, Lawn JE, Jan S, et al. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet 2007; 369: 2121–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Condo J, Mugeni C, Naughton B, Hall K, Tuazon MA, Omwega A, et al. Rwanda's evolving community health worker system: a qualitative assessment of client and provider perspectives. Hum Resour Health 2014; 12: 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Persson LÅ, Nga NT, Målqvist M, Thi Phuong Hoa D, Eriksson L, Wallin L, et al. Effect of facilitation of local maternal‐and‐newborn stakeholder groups on neonatal mortality: cluster‐randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2013; 10: e1001445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Målqvist M, Hoa DPT, Persson LÅ, Ekholm Selling K. Effect of facilitation of local stakeholder groups on equity in neonatal survival; results from the NeoKIP trial in Northern Vietnam. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0145510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Houweling TAJ, Tripathy P, Nair N, Rath S, Rath S, Gope R, et al. The equity impact of participatory women's groups to reduce neonatal mortality in India: secondary analysis of a cluster‐randomised trial. Int J Epidemiol 2013; 42: 520–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, Azad K, Coomarasamy A, Copas A, et al. Women's groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low‐resource settings: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet 2013; 381: 1736–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet 2003; 361: 2226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS, Bellagio Child Survival Study Group . How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 2003; 362: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Darmstadt GL, Walker N, Lawn JE, Bhutta ZA, Haws RA, Cousens S. Saving newborn lives in Asia and Africa: cost and impact of phased scale‐up of interventions within the continuum of care. Health Policy Plan 2008; 23: 101–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pattinson R, Kerber K, Buchmann E, Friberg IK, Belizan M, Lansky S, et al. Stillbirths: how can health systems deliver for mothers and babies? Lancet 2011; 377: 1610–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Pattinson R, Cousens S, Kumar R, Ibiebele I, et al. Stillbirths: Where? When? Why? How to make the data count? Lancet 2011; 377: 1448–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aleman J, Brännström I, Liljestrand J, Peña R, Persson LA, Steidinger J. Saving more neonates in hospital: an intervention towards a sustainable reduction in neonatal mortality in a Nicaraguan hospital. Trop Doct 1998; 28: 88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hanson C, Manzi F, Mkumbo E, Shirima K, Penfold S, Hill Z, et al. Effectiveness of a home‐based counselling strategy on neonatal care and survival: a cluster‐randomised trial in six districts of rural southern Tanzania. PLoS Med 2015; 12: e1001881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Victora CG, Wagstaff A, Schellenberg JA, Gwatkin D, Claeson M, Habicht J‐P. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough. Lancet 2003; 362: 233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Victora CG, Barros AJD, Axelson H, Bhutta ZA, Chopra M, França GVA, et al. How changes in coverage affect equity in maternal and child health interventions in 35 Countdown to 2015 countries: an analysis of national surveys. Lancet 2012; 380: 1149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Målqvist M. Abolishing inequity, a necessity for poverty reduction and the realisation of child mortality targets. Arch Dis Child 2015; 100(Suppl 1): S5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wu J, Yunus M, Streatfield PK, Emch M. Association of climate variability and childhood diarrhoeal disease in rural Bangladesh, 2000–2006. Epidemiol Infect 2014; 142: 1859–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. UNICEF . State of the world's children 2012: children in an urban world. New York, NY, USA: United Nations Children's Fund; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marcil L, Afsana K, Perry HB. First steps in initiating an effective maternal, neonatal, and child health program in urban slums: the BRAC Manoshi Project's Experience with community engagement, social mapping, and census taking in Bangladesh. J Urban Health 2016; 93: 6–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Buse K, Hawkes S. Health in the sustainable development goals: ready for a paradigm shift? Global Health 2015; 11: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hill PS, Buse K, Brolan CE, Ooms G. How can health remain central post‐2015 in a sustainable development paradigm? Global Health 2014; 10: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bryce J, Victora CG, Black RE. The unfinished agenda in child survival. Lancet 2013; 382: 1049–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Binagwaho A, Farmer PE, Nsanzimana S, Karema C, Gasana M, de Dieu Ngirabega J, et al. Rwanda 20 years on: investing in life. Lancet 2014; 384: 371–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Griggs D, Stafford‐Smith M, Gaffney O, Rockström J, Öhman MC, Shyamsundar P, et al. Policy: sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 2013; 495: 305–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rahman A, Moran A, Pervin J, Rahman A, Rahman M, Yeasmin S, et al. Effectiveness of an integrated approach to reduce perinatal mortality: recent experiences from Matlab, Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pervin J, Moran A, Rahman M, Razzaque A, Sibley L, Streatfield PK, et al. Association of antenatal care with facility delivery and perinatal survival ‐ a population‐based study in Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012; 12: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Peña R, Pérez W, Meléndez M, Källestål C, Persson LÅ. The Nicaraguan Health and Demographic Surveillance Site, HDSS‐Leon: a platform for public health research. Scand J Public Health 2008; 36: 318–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]