Abstract

Objective:

The present study aims to evaluate antioxidants and protective role of Cassia tora Linn. against oxidative stress-induced DNA and cell membrane damage.

Materials and Methods:

The total and profiles of flavonoids were identified and quantified through reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. In vitro antioxidant activity was determined using standard antioxidant assays. The protective role of C. tora extracts against oxidative stress-induced DNA and cell membrane damage was examined by electrophoretic and scanning electron microscopic studies, respectively.

Results:

The total flavonoid content of CtEA was 106.8 ± 2.8 mg/g d.w.QE, CtME was 72.4 ± 1.12 mg/g d.w.QE, and CtWE was 30.4 ± 0.8 mg/g d.w.QE. The concentration of flavonoids present in CtEA in decreasing order: quercetin >kaempferol >epicatechin; in CtME: quercetin >rutin >kaempferol; whereas, in CtWE: quercetin >rutin >kaempferol. The CtEA inhibited free radical-induced red blood cell hemolysis and cell membrane morphology better than CtME as confirmed by a scanning electron micrograph. CtEA also showed better protection than CtME and CtWE against free radical-induced DNA damage as confirmed by electrophoresis.

Conclusion:

C. tora contains flavonoids and inhibits oxidative stress and can be used for many health benefits and pharmacotherapy.

KEYWORDS: Antioxidants, Cassia tora extract, DNA protection, free radicals, membrane protection, scanning electron microscopy

INTRODUCTION

Oxidative stress is the center of many disease conditions such as degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease,[1] diabetes,[2] and cardiovascular disorders.[3] Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated as part of normal metabolic processes.[4] The ROS that are generated during normal metabolism include hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anion, singlet oxygen, and hydroxyl radicals.[5,6] Oxidative stress is the result of imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants in the body.[7] The imbalance condition for a long period causes damage to cells, macromolecules, tissues, organs, and body as a whole. Once there is damage to these macromolecules, their vital functions in the cell metabolism are altered resulting in the manifestation of many diseases.[8,9] Nucleic acid is one of the major targets for the oxidative damage,[10] resulting in the metabolic dysfunction and membrane disruption, which leads to many diseases such as cancer,[11] degenerative diseases, and atherosclerosis.[12,13] Those molecules which neutralize free radicals are called as antioxidants.[14] Plants are the richest sources of antioxidants.[15] Due to their enormous potential, plants are used for many therapeutic applications. The medicinal potential of plants is attributed to the presence of secondary metabolites such as phenolic compounds, flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, vitamins, and tannins. Since from the last one century, there has been considerable interest in the use of herbal-based medicine worldwide.[16] Moreover, in modern medicine, plants occupy a very significant place as raw material for preparation of drugs.[17]

Nowadays, there is an intensive research on identifying novel antioxidants from naturally available sources. These antioxidants counteract free radical ions and inhibit oxidative damage caused by free radicals.[18] Cassia tora belongs to family Fabaceae, and it mainly grows in India, China, Sri Lanka, and some tropical countries. It is also called as Charota in Hindi and Foetid Cassia in English. It is also known by different names such as Sickle Senna, Wild Senna, Sickle Pod, Coffee Pod, Tovara, Chakvad, and Ringworm plant in various places.[19,20] Traditionally, cassia is used in Ayurveda mainly for the treatment of leprosy, cardiac disorder, flatulence, bronchitis, cough, dyspepsia, intestinal dryness, etc., The seeds of cassia are in use to treat vision problem, lowering blood pressure, cholesterol, antiasthenic, and xerophthalmia.[20,21] C. tora has varied bioactivities, namely, antioxidant,[22] hypolipidemic,[23] larvicidal,[24] antihepatotoxic,[25] antiplasmodial,[26] and anti-inflammatory.[27,28] Moreover, a wide range of compounds isolated from this plant such as achrosin, emodin, anthraquinones, apigenin, chryso-obtusin, chrysarobin, chrysophanol, and campesterol showed antioxidant activity.[29] The extract of C. tora showed peroxynitrite scavenging activity which is ascribed to alaternin and norrubrofusarin glucose in it. Peroxynitrite is potent pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory molecule which is formed as a result of oxidative stress.[30] Recent report showed that C. tora leaves extract showed significant cognition enhancing property in scopolamine-induced amnesia models.[31] Polyphenols from C. tora leaves can prevent apoptosis and modulate cataract pathology in rat pups.[32] Furthermore, C. tora extract and its active component aurantio-obtusin inhibited allergic responses in IgE-mediated mast cells and anaphylactic models.[28] The ethnomedicinal uses of C. tora imply that this plant may be capable of protecting DNA and membrane damage against oxidative stress. The present study is focused to determine the levels of flavonoids in the leaf extracts of C. tora and to determine its role in protecting DNA and membrane damage by oxidative stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Agarose, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, and trichloroacetic acid were purchased from Sisco Research Laboratories. λ-DNA was purchased from Bangalore Genei, India. FeSO4, 7H2O, H2O2, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical, 2,2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), 2-deoxy-d-ribose, Tris base, ascorbic acid, Na2-EDTA, ethidium bromide (EtBr), epicatechin, myricetin, daidzein, quercetin, kaempferol, apigenin, rutin and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and thiobarbituric acid were purchased from Sigma Chemicals Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals used in the experiment were of analytical grade.

Collection of plant material

C. tora plant was collected in Shanthigrama Hobli, Hassan district, Karnataka, India. The location of plant collected lie between 12° 13' and 13° 33' north latitudes and 75° 33' and 76° 38' east longitude. Collected plant was identified by a botanist. The collected plant was washed with running tap water to remove soil and other dust particles, followed by washing with distilled water. The leaf sample was separated and shade dried at room temperature (25°C) for 1 week. The dried leaf was finely powdered using domestic mixer and uniformly sieved using 18 mm mesh size.

Preparation of solvent extract

Fifteen grams of finely powdered leaf was extracted with 150 ml of hexane for 6 h, followed by extraction with 150 ml of ethyl acetate for 12 h using Soxhlet apparatus, the extract is filtered using 0.45 mm filter paper, and the extract was then concentrated at 40°C. Further, the extract was freeze dried to achieve complete removal of solvent and stored at 4°C for further use. The residue obtained from ethyl acetate was extracted with 150 ml of methanol for 12 h using Soxhlet apparatus, and it is filtered using 0.45 mm filter paper. The extract was then concentrated at 40°C, followed by freeze drying to completely remove solvent and stored at 4°C for further use. The residue obtained from methanol extraction was further extracted with 10 g of dried residue being added into 100 ml of sterile double-distilled water, followed by boiling for 20 min, and the infusion obtained was filtered with a sterile filter paper Whatman No. 1 under sterile conditions. The extract was then concentrated by a freeze drier (DELVAC company, model no. 00-12).

Analysis of total flavonoids

The total flavonoid content of C. tora extracts was determined adopting earlier described method.[33] Quercetin (0–100 μg/ml in methanol) was used as a standard reference. The standard and the extract solutions (mg/ml) were mixed with 0.1 ml of 10% (W/V) aluminum chloride, 0.1 ml of potassium acetate, 1.5 ml of methanol, and 2.8 ml of water. For the blank, both potassium acetate and aluminum chloride were added and their volume was replaced by water. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and the absorbance was taken at 415 nm. The result was analyzed in quercetin equivalent using a 0–100 μg/ml standard curve.

Identification of flavonoids in Cassia tora extracts by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

Detection and quantification of flavonoids in the C. tora extracts were analyzed by earlier described method,[34] with slight modifications. The standards used were epicatechin, myricetin, daidzein, quercetin, and kaempferol. The column used was reversed-phase C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm) high-performance liquid chromatography system (Agilent-Model 1200 series), and the detector used was diode array detector (operating at 260 nm). A gradient solvent system is used which consisting of solvent A – water: acetic acid (98:2) and solvent B – methanol: acetic acid (99:1). Gradient elution was linear to 10% B in 5 min, 23% B in 31 min, and 35% B in 43 min, followed by 6 min washing with 100% B and equilibrated for 6 min at 100% A with total run time of 55 min. Ultraviolet (UV) absorbance at 260 nm was used to detect and quantify flavonoids present in the extracts.

Total antioxidant capacity

The total antioxidant capacity of extracts was evaluated by the phosphomolybdenum method.[35] The assay is based on the reduction of Mo (VI) to Mo (V) by the extract and subsequent formation of green phosphate Mo (V) complex at acid pH. In this assay, 0.1 ml of extract was combined with 3 ml of reagent solution (0.6 M sulfuric acid, 28 mM sodium phosphate, and 4 mM ammonium molybdate). The tubes were incubated at 95°C for 90 min. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at 695 nm using a spectrophotometer against blank after cooling to room temperature. Methanol in the place of extract was used as the blank. The antioxidant activity is expressed as the number of gram equivalent of ascorbic acid. The calibration curve was prepared by mixing ascorbic acid (10–100 μg/ml) with methanol.

Measurement of antioxidant activity

2,2'-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical cation decolorization assay

The antioxidant activity was tested by ABTS method described earlier.[36] 7 mM concentration of ABTS was diluted in water. ABTS radical cations were generated by mixing 7 mM ABTS and 2.45 mM potassium persulfate. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 12–16 h in dark. After 12–16 h, the reaction mixture was diluted in methanol to obtain an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.020 at 734 nm. In this study, 0–25 μg/ml of different concentrations of C. tora extracts was mixed with 1000 μl of ABTS solution and the absorbance was measured using a UV/visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu) exactly after 5 min of initial mixing. Ascorbic acid (AA) was used as positive control. A dose-dependent curve was plotted to calculate the IC50 value.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was analyzed by deoxyribose method.[37] Hydroxyl radical was generated using Fenton reagent (ascorbate-EDTA-H2O2-Fe3+ method). The total reaction mixture contained 2-deoxy-2-ribose (2.6 mM), ferric chloride (20 μM), H2O2 (500 μM), ascorbic acid (100 μM), and plant extracts with various concentrations. The total reaction volume was made up to 1 ml with phosphate buffer (100 μM, pH 7.4). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h to initiate the reaction. After incubation period, 0.8 ml of the reaction mixture was added to the 2.8% TCA (1.5 ml), followed by 1% tertiary butyl alcohol (1 ml) and 0.1% safety data sheet (0.2 ml). The reaction mixture was then heated to 90°C for 20 min to obtain color, later cooled and 1 ml of double-distilled water was added and absorbance was read at 532 nm with respective blank sample. The percentage of inhibition was calculated by the following equation:

% inhibition = (A0 – [A1 − A2])/A0 × 100

where A0 is the absorbance of the control without a sample, A1 is the absorbance in the presence of the sample and deoxyribose, and A2 is the absorbance of the sample without deoxyribose.

Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay

The reductive potential of the C. tora extracts was determined using standard method.[38] Different concentrations of C. tora extracts in 0.5 ml of water were mixed with equal volumes of 0.2 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.6, and 1% potassium ferricyanide [K3 Fe (CN)6]. The mixture was incubated for 20 min at 50°C. At the end of incubation, an equal volume of 10% trichloroacetic acid was added to the mixture and centrifuged at 3200 ×g for 10 min. The supernatant was mixed with distilled water and 0.1% ferric chloride at 1:1:0.2 (v/v/v) and the absorbance was measured at 700 nm. An increase in the absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates the reducing power potential of the sample. Ascorbic acid was used as a standard for comparison.

Prevention of λ-DNA damage by Cassia tora extracts

Agarose gel electrophoresis

Oxidative λ-DNA damage was prevented by C. tora leaf extract, and it was assayed by adopting previously described method.[39] λ-DNA (0.5 μg) with and without C. tora extracts (50 μg) was incubated with Fenton reagent (1 mMFeSO4, 25 mM H2O2 in Tris buffer 10 mM, pH 7.4) in a final reaction volume of 30 μL for 1 h at 37°C. Relative difference between oxidized and native DNA was analyzed on 1% agarose gel prepared in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (pH 8.5) at 50 V for 3 h at room temperature. The gel was documented (Uvitec Company, software platinum 1D, UK) and the band intensity was determined.

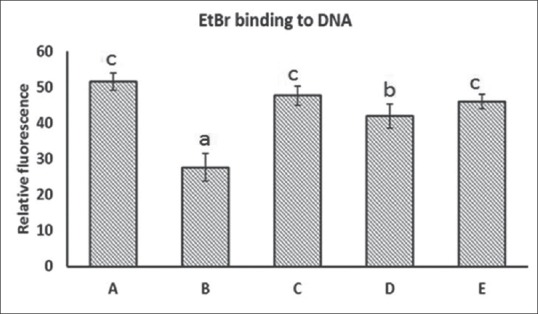

Ethidium bromide binding to DNA by fluorescence analysis

Protective effect of C. tora extracts against oxidative λ-DNA damage was analyzed by adopting previously described method.[40] The change in fluorescence of EtBr bound to DNA was measured. The assay was carried out by incubating λ-DNA (1 μg) with 1 mM FeSO4, 25 mM H2O2 in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) for 1 h. The protection of oxidative λ-DNA damage was analyzed in the presence of 50 μg of C. tora extracts for 1 h. The samples thus prepared were mixed with 5 μg of EtBr, and the fluorescence was recorded at excitation at 535 nm and emission at 600 nm.

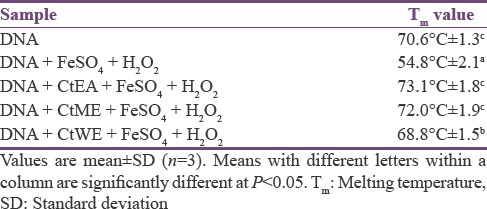

Melting temperature studies

The effect of C. tora extracts on the λ-DNA integrity was measured by thermal denaturation studies using a spectrophotometer (Ultrospec, 4300 probe) equipped with thermoprogrammer and data processor (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Hong Kong). λ-DNA (1 μg) was incubated with 1 mM FeSO4, 25 mM H2O2 in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) for 1 h for monitoring the oxidative λ-DNA damage in the presence of extract (50 μg) for 1 h. The melting profiles (melting temperature [Tm]) of λ-DNA were recorded at different temperatures ranging from 25°C to 95°C. The Tm value was determined graphically from the absorbance versus temperature plots.

Preparation of erythrocytes

Rat erythrocytes were isolated and stored as per previously described method.[41] Briefly, blood samples collected were centrifuged (1500 ×g, 5 min) at 4°C; erythrocytes were separated from the plasma and buffy coat and were washed three times using 10 volumes of 20 mM phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4, PBS). Each time, the cell suspension centrifuged at 1500 ×g for 5 min. The supernatant and buffy coats of white cells were carefully removed with each wash. Erythrocytes thus obtained were stored at 4°C and used within 6 h for further studies.

Protective effect on erythrocytes structural morphology

Rat erythrocytes (50 μl) were incubated with and without C. tora extracts (50 μg) and treated with 100 μl of 200 μM H2O2 for 30 min at 37°C. After incubation, it was centrifuged at 1500 ×g for 10 min and the cell pellets were processed and were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde on a coverslip.[42,43] After fixing on the coverslip, the cells were dehydrated in an ascending series of acetone (30%–100%). The dried samples were mounted on an aluminum stub (100–200 Å) using double-sided tape and coated with gold film with a thickness of 10–20 nm using a sputter coater (Polaron, E 5000, and scanning electron micrograph [SEM] coating system). The cells were examined under a scanning electron microscope (Model No, LEO 425 VP, Electron Microscopy Ltd, Cambridge, UK).

In vitro assay of inhibition of rat erythrocyte hemolysis

The inhibition of rat erythrocyte hemolysis by the C. tora extracts was determined as per the previously described method with slight modifications.[44] The rat erythrocyte hemolysis was performed with H2O2 as free radical initiator. To 200 μl of 10% (v/v) suspension of erythrocytes in PBS, C. tora extracts with different concentrations (0–200 μg) were added. To this, 100 μl of 500 μM H2O2 (in PBS pH 7.4) was added. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and was centrifuged at 2000 ×g for 10 min. The absorbance of the resulting supernatant was measured at 410 nm by taking 200 μl of reaction mixture with 800 μl PBS to determine the hemolysis. Likewise, the erythrocytes were treated with H2O2 and without inhibitors (extracts) to obtain a complete hemolysis. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at the same condition. Percentage of hemolysis was calculated by taking hemolysis caused by 200 μM H2O2 as 100 %. The IC50 values and the concentration required for the inhibition of 50% hemolysis were calculated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

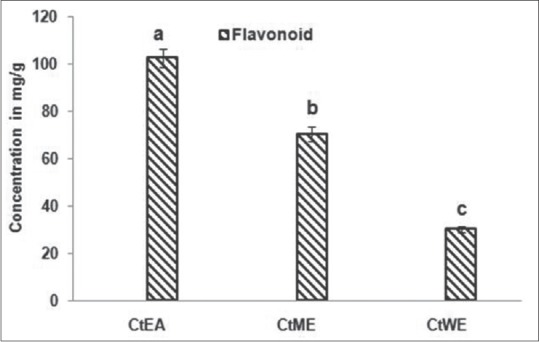

Flavonoids content of Cassia tora extracts and identification of flavonoids by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

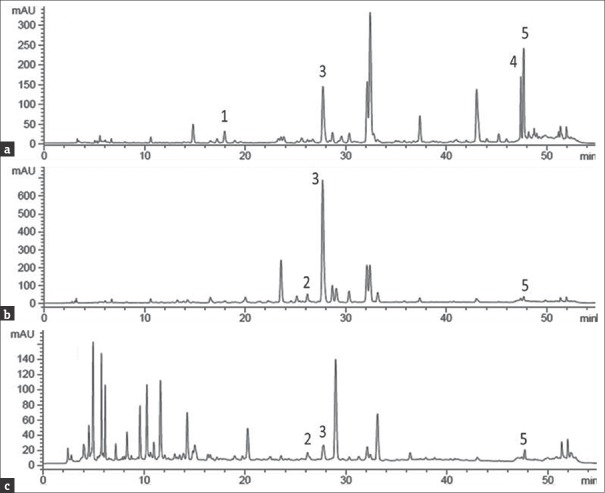

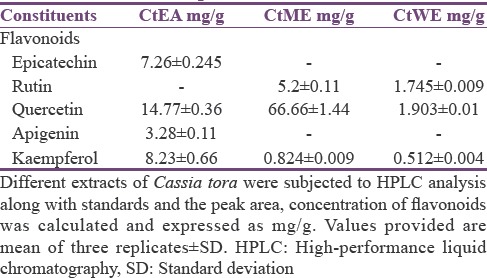

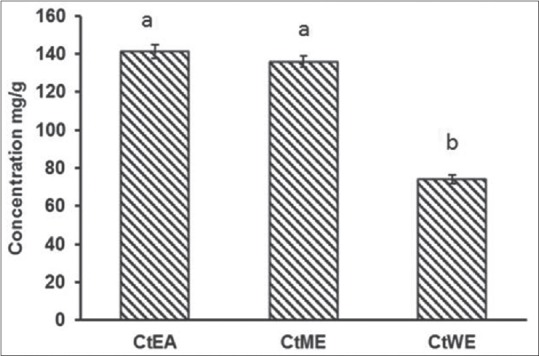

The levels of flavonoid compounds in the different solvent extract obtained from leaf are represented in Figure 1. The results showed that CtEA contains 106.8 ± 2.8 mg/g d.w.QE, CtME contains 72.4 ± 1.1 mg/g d.w.QE, and CtWE contains 30.4 ± 0.8 mg/g d.w.QE. The high-performance liquid chromatography analysis revealed the presence of flavonoid compounds with maximum detection wavelength at 260 nm. The major flavonoids present in C. tora extracts were in the following decreasing order: in CtEA: quercetin >kaempferol > epicatechin; in CtME: quercetin >rutin >kaempferol; whereas, in CtWE: quercetin >rutin >kaempferol [Table 1 and Figure 2]. The extract contains significant amounts of flavonoids in them. This result suggests that antioxidant activity of extracts is ascribed to flavonoids present in the extract. Polyphenol and flavonoid compounds are collectively present in plants. They have varied bioactives such as antiallergic, anti-inflammatory, antiatherosclerotic, and antithrombogenic.[45] Furthermore, phenolic compounds isolated from Cassia species such as alaternin and norrubrofusarin glucoside have shown to have free radical scavenging activity.[46] The antioxidant potential of flavonoids has been evaluated in vitro to measure the ability to trap free radicals. This ability depends on the molecular structure of the molecule.[47,48] These flavonoids are of beneficial to humans as it has antioxidant function, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, antiallergic, antitumor activity, etc.[49,50,51,52]

Figure 1.

Total flavonoid content of leaf extracts of Cassia tora. Extracts of Cassia tora were quantitated for total flavonoid content. The values were expressed in mg/g d.w.QE. The values are mean of three replicates ± standard deviation. Means followed by letters (a, b) are significantly different (P < 0.05)

Table 1.

Flavonoid profiles of Cassia tora extracts

Figure 2.

High-performance liquid chromatography chromatogram of Cassia tora extracts. Different extracts of Cassia tora were subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography analysis (a) CtEA, (b) CtME, (c) CtWE, high-performance liquid chromatography chromatogram of Cassia tora extracts. The flavonoids analyzed were expressed in numbers (1) epicatechin, (2) rutin, (3) quercetin, (4) apigenin, and (5) kaempferol

Total antioxidant content

The total antioxidant content of the C. tora extracts was measured spectrophotometrically by phosphomolybdenum method. The reduction of Mo (VI) to Mo (V) by the extracts is the main principle of this assay. The formation of green-colored Mo (V) end product was measured at 695 nm. The total antioxidant activity of the extracts in the decreasing order; CtEA > CtME > CtWE and is presented in Figure 3. The antioxidant activity of extracts is attributed to flavonoids and other antioxidant compounds present in the extracts. Previous report showed that C. tora is rich in phytochemical constituents anthraquinones and glycosides and exhibits rich antioxidant activity.[53,54]

Figure 3.

Total antioxidant content of Cassia tora extracts. Data represent mean ± standard deviation, letter a, b indicates statistical difference between the extracts at P < 0.05

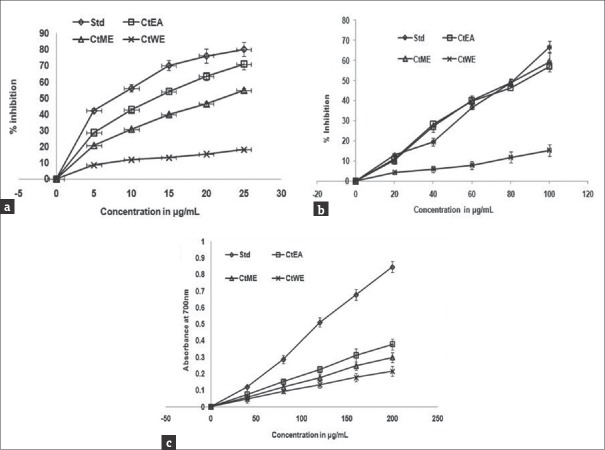

2,2'-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical cation decolorization assay

This method is used to know the ability of antioxidant molecules to quench the long live ABTS+. When antioxidant addition to this preformed radical cation reduced it to ABTS in dose dependent manner.[55] The ABTS is in blue green; by reacting with oxidizing agent potassium persulfate, it becomes dark blue. The antioxidants present in the extracts acts as strong hydrogen donor, in which the colored solution turns to colorless; this can be measured at 734 nm. The IC50 value of ascorbic acid was 8.91 ± 0.8 μg/ml, CtEA was 13.88 ± 1.2 μg/ml, CtME was 21.7 ± 2.1 μg/ml, and CtWE was 24.50 ± 2.8 μg/ml. Average IC50 values determined by ABTS assay were lower as compared to the values determined by hydroxyl scavenging and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assays as represented in Figure 4a. This result implies that free radical scavenging activity is ascribed to flavonoid. Earlier studies with methanol extracts of C. tora leaf exhibited antioxidant potency confirming our results.[56,57]

Figure 4.

Antioxidant activities of Cassia tora extracts. (a) Free radical scavenging activity by 2,2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), (b) hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, (c) ferric reducing antioxidant power of CtEA, CtME, and CtWE of Cassia tora. Ascorbic acid was used as positive control. The data points represent means ± standard deviation of three independent determinations

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of Cassia tora extracts

Hydroxyl radical is the major ROS present in biological systems.[58] The hydroxyl radical has the ability to cause DNA strand breakage and DNA base modifications, which leads to cytotoxicity, carcinogenesis, etc.[59,60] It also considered as initiators of lipid peroxidation. Hydroxyl radical scavenging potential of C. tora extracts was analyzed using 2-deoxy-2-ribose method. IC50 value of CtEA was 82.08 ± 2.88 μg/ml, CtME was 85.8 ± 3.11 μg/ml, CtWE was 327.7 ± 6.88 μg/ml, and of standard ascorbic acid was 81.83 ± 2.4 μg/ml as shown in Figure 4b. This indicates the ability of the extracts to scavenge hydroxyl radicals. This result suggests that extracts reduce the chromogen product formation, which reveals hydroxyl radical scavenging ability. The methanolic extracts of Ficus sycomorus, Piliostigma thonningii, and Moringa oleifera exhibited higher radical scavenging activity in a dose-dependent manner.[61,62]

Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay

FRAP assay is mainly used to measure antioxidant activity. The results of this assay indicate that there was a gradual increase in absorbance in a dose-dependent manner, with increase in the concentration of different extracts. The antioxidant activity trend of different extracts was in the decreasing order; CtEA > CtME > CtWE as shown in Figure 4c. This result gives an insight that the extracts have the ability to scavenge various free radicals. Earlier findings from other groups showed that those extracts with free radical scavenging ability may be used for various therapeutics to inhibit oxidative stress.[63] Arya and Yadav showed that different solvent extracts of C. tora leaf exhibited higher ferric reducing power and implied the presence of many bioactive antioxidant molecules.[64] Dalar et al. found that hydrophilic extracts of flower and stem exhibited stronger FRAP potency than leaf and root of Centaurea karduchorum.[65] M. oleifera leaf extracts exhibited higher FRAP.[61] Similarly, reducing capacities exhibited in commonly available herbs widely used in many phytopharmaceutical industry including Zingiber officinale, Cananga odorata, Daucus carota, Carica papaya, Laurus nobilis, Ribes nigrum, Vanilla planifolia and pine, oak, and cinnamon have shown high ferric reducing antioxidant potential.[66] Earlier report suggests that extracts of C. tora exhibited high amount of secondary metabolites and showed rich antioxidant potential.[67]

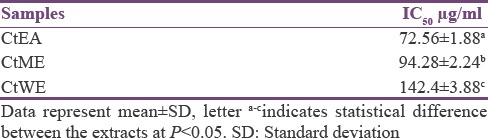

Inhibition of rat erythrocytes hemolysis

In the current study, membrane damage or hemolysis of erythrocytes was induced using H2O2. The protective effect of C. tora against damage of erythrocytes was studied using C. tora extracts. Oxidants lyse the erythrocytes membrane and lead to leaching of hemoglobin into the medium. The medium turns into red and it is measured at 410 nm as shown in Table 2. The CtEA showed higher inhibitory activity than CtME and CtWE. The IC50 values for the corresponding extracts CtEA, CtME, and CtWE 72.56 ± 1.88 μg/ml, 94.28 ± 2.24 μg/ml, and 142.4 ± 3.88 μg/ml, respectively. This indicates that bioactive constituents present in the plants acts as antihemolytic activity. The hydrophilic extracts of six plants, namely, Morinda lucida, Uvaria chamae, Lonchocarpus cyanescens, Croton zambesicus, Raphiostylis beninensis, and Xylopia aethiopica, showed high hemolysis inhibition of red blood cells (RBCs).[54] Similarly, methanol and ethyl acetate extract of plant stem of Caesalpinia mimosoides exhibited significant antihemolytic activity which confirms the cytoprotective function.[68]

Table 2.

Red blood cells protective ability of Cassia tora extracts

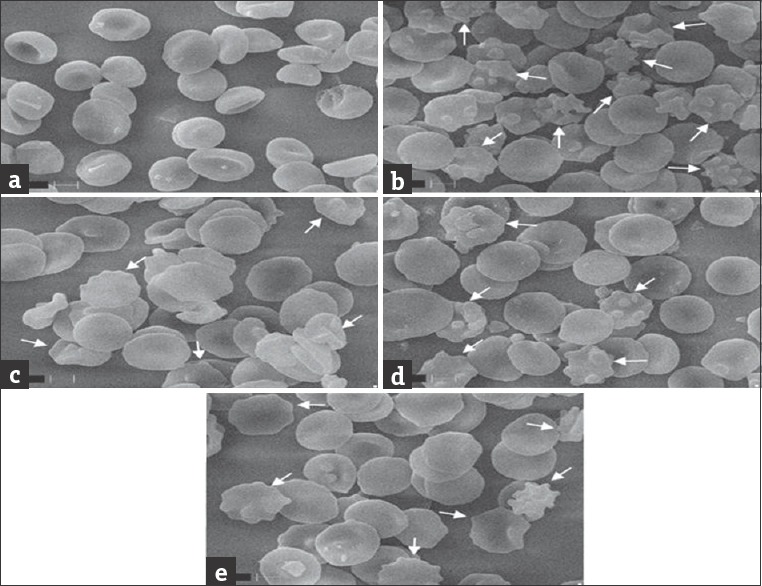

Protective effect of Cassia tora extracts on red blood cell structural morphology

In vitro SEMs of erythrocytes incubated with H2O2 alone and with extracts are shown in Figure 5. Control erythrocytes appeared as classic discocytes while exposure to H2O2 resulted in a significant change in the cell shape and distinct echinocyte formation. The changes in the morphology induced by oxidative system were prevented when the cells were treated with CtEA and CtME extracts. Oxidant damages the cell integrity and leads to disruption in cell rigidity and shape and leads to the formation of echinocytes. Thus, formed cells eventually affect the functioning of erythrocytes.[69] According to bilayer couple hypothesis, when oxidant or foreign molecules enter RBC, it induce changes in RBC shape and function due to discrepancy of two monolayers of the red cell membrane.[70,71] When compounds insert into the inner layer, stomatocytes are formed. However, speculated echinocytes are formed when it locates into the outer layer. To substantiate the results of cytoprotectivity on erythrocyte, oxidation was studied. The SEMs represented in Figure 5 show the protective ability of extracts on membrane oxidation when compared to the normal erythrocytes [Figure 5a]. Erythrocytes when treated with H2O2 showed the appearance of echinocytes indicates damage to the cell membrane [Figure 5b]. The CtEA- and CtME-treated RBC displayed normal erythrocyte morphology which indicates the protective role of C. tora extracts. Studies showed that C. tora seed extract possesses significant cytoprotection against galactosamine-induced toxicity in primary rat hepatocytes.[72] Girish et al. showed that aqueous extract of black gram husk protected erythrocyte membrane damage caused by H2O2. Furthermore, hydroalcoholic extracts of Sapindus saponaria L. prevents the cellular structural changes in Candida albicans.[40,73] Furthermore, reports available from the literature showed polyphenols from plant sources having cytoprotective role in cell lines.[74,75]

Figure 5.

Scanning electron micrograph of normal erythrocytes and protective effect of Cassia tora against H2O2 induced oxidative damage on RBC. (a) RBC; (b) RBC + H2O2; (c) RBC + H2O2 + CtEA; (d) RBC + H2O2 + CtME; (e) RBC + H2O2 + CtWE (×10,000). RBC: Red blood cell

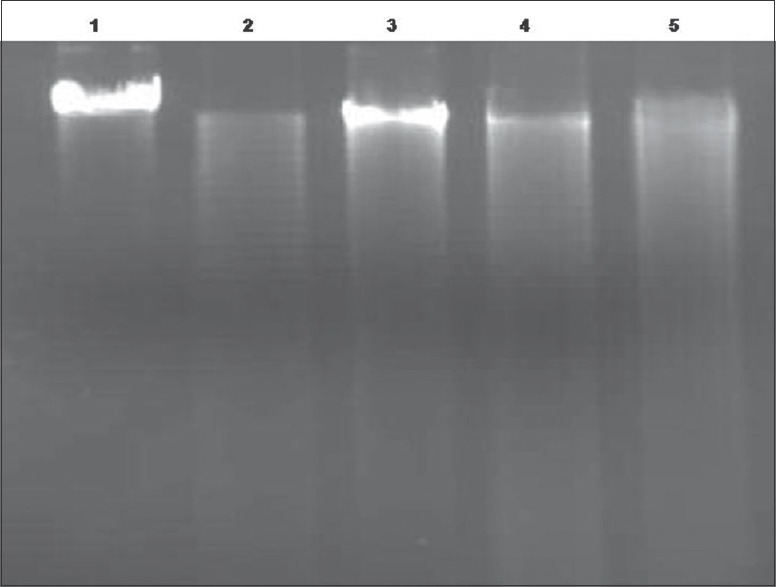

Inhibition of Fe2+ induced λ-DNA damage by Cassia tora extracts

DNA protection ability of Cassia tora extracts

DNA damage is mainly caused by the radiations and induces photolysis of H2O2. The hydroxyl radicals thus released from photolysis causes DNA damage, leading to breakage in the DNA strands and DNA base modification.[76,77,78,79] DNA protective ability of C. tora extracts was evaluated on λ-DNA oxidation [Figure 6]. The hydroxyl radical generated by Fenton reagent caused DNA oxidation, with an increase in electrophoretic mobility (Lane 2). This was recovered with the treatment of CtEA and CtME extracts than CtWE. Results indicate that λ-DNA in the presence of radicals and with extracts showed increase in the band intensity where λ-DNA with radicals and without extracts showed no band in 1% agarose gel. Further, treating λ-DNA with extract alone for 1 h did not alter DNA integrity, which suggests the extract itself was not toxic to λ-DNA. Furthermore, more band intensity was observed in the CtEA extracts than CtME and CtWE. Thus, CtEA seems to have protected DNA damage induced by oxidative stress. Thus, DNA damage protection activity of C. tora is attributed to flavonoids and other antioxidant compounds that are present in the extract. Methanol extract of Mentha spicata Linn exhibits successful protecting activity against DNA damage.[80]

Figure 6.

Gel electrophoresis image of λ-DNA damage inhibition of Cassia tora extracts. Gel electrophoresis image of λ-DNA damage inhibition by Cassia tora extracts after 1h of incubation of reaction mixture. Lane 1: 0.5μg DNA alone; Lane 2: 0.5 μg DNA + 1mM FeSO4 + 25 mM H2O2; Lane 3: 0.5 μg DNA + 1 mM FeSO4 + 25 mM H2O2 + 50 μg CtEA; Lane 4: 0.5 μg DNA + 1 mM FeSO4 + 25 mM H2O2 + 50 μg CtME; Lane 5: 0.5 μg DNA + 1 mM FeSO4 + 25 mM H2O2 + 50 μg CtWE

Melting temperature studies

The Tm study provides an insight on the integrity of DNA. The Tm of λ-DNA was 70.6°C, whereas it was 54.8°C when it was treated with FeSO4/H2O2 shown in Table 3. Low Tm in the case of λ-DNA treated with FeSO4/H2O2 was due to the damage of DNA in the presence of hydroxyl radicals whereas Tm value for DNA in the presence of CtEA with FeSO4/H2O2 was 73.1°C, CtME with FeSO4/H2O2 was 72.0°C, and CtWE with FeSO4/H2O2 was 68.8°C. The higher Tm of λ-DNA in the presence of extracts indicates that oxidative damage was prevented by the extract. Thus, this result indicates that extracts prevented the oxidative DNA damage caused by chelating free radicals. The mechanism of prevention may be due to the scavenging of free radicals by the flavonoids. Girish et al. evaluated that the aqueous extracts of black gram husk prevent the damage of DNA in the presence of hydroxyl radicals.[40]

Table 3.

Melting temperature of DNA treated with Cassia tora

Ethidium Bromide-binding Studies

Fenton reaction causes damage in λ-DNA. The measurement of λ-DNA damage by FeSO4/H2O2 is done by noting the changes in fluorescence of EtBr on binding to λ-DNA in the presence and absence of extracts. EtBr fluorescence for intact λ-DNA was 51.51, whereas λ-DNA treated with FeSO4 in the presence of H2O2 was 27.65. The significant decrease in the fluorescence intensity in the case of λ-DNA treated with FeSO4 and H2O2 was due to the damage of DNA by hydroxyl radicals generated. However, the fluorescence intensity for DNA in the presence of FeSO4/H2O2 and C. tora extract was 47.7, 41.98, and 45.96 for CtEA, CtME, and CtWE, respectively, shown in Figure 7. The higher fluorescence intensity observed may be attributed to the free radical scavenging activity of antioxidant compounds and flavonoids in the extracts which prevented DNA damage.

Figure 7.

Ethidium bromide binding to DNA. (a) λ-DNA; (b) λ-DNA + FeSO4 + H2O2; (c) λ-DNA + CtEA + FeSO4 + H2O2; (d) λ-DNA + CtME + FeSO4 + H2O2; (e) λ-DNA + CtWE + FeSO4 + H2O2. Values are mean ± standard deviation (n = 3), means with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05

Statistical analysis

Three independent experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the data were reported as mean ± standard deviation as determined using the statistical program SPSS for Windows, version 10.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.), with level of significance of P < 0.05.

CONCLUSION

Free radicals are produced in normal physiological process, which is very noxious and causes many neurodegenerative diseases, chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and atherosclerosis. Imbalance in levels of free radicals and antioxidants in the body causes oxidative stress. The imbalance may be due to excessive production of free radicals or reduced production of antioxidants. There is a need to augment the system with external sources of antioxidants. The requirement of antioxidant through nutrient supply is very much essential. For this purpose, identifying different sources of antioxidants is an important task. To date, plants are the richest source of antioxidants. Our current study on using CtEA and CtME showed that they are rich in flavonoids. The C. tora shows that it has quercetin, epicatechin, kaempferol, and apigenin, which acts as antioxidants. The protective effect of these molecules in the extract also exhibited protective role against DNA and erythrocyte damage caused by free radicals. These molecules present in the extracts have the ability to alleviate free radical-radical-induced oxidative stress condition [Figure 8]. This plant could be source of several nutraceuticals for managing many degenerative diseases such as neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and diabetes. This study is the first of its kind wherein different solvent extracts are used to find out levels of flavonoids and assayed for their protective effect against free radical-induced DNA and membrane damage. Further work is in progress to isolate the novel antioxidant compounds responsible for the activity.

Figure 8.

In the biological system, ROS are formed as a natural byproduct during normal metabolism. Environmental stress elevates ROS levels dramatically. This leads to significant damage to nucleic acids and cell structures. Plant as a source of novel drug candidate for protecting DNA and cell structure from oxidative damage. Natural bioactives present in the C. tora extracts acts through several mechanisms to quench free radicals. Extracts exhibited antioxidant properties and also protected DNA and cell membrane from oxidative damage

Financial support and sponsorship

This work is funded by Startup Grant for Young Scientists by Science and Engineering Research Board, Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen X, Guo C, Kong J. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7:376–85. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asmat U, Abad K, Ismail K. Diabetes mellitus and oxidative stress-A concise review. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24:547–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Csányi G, Miller FJ., Jr Oxidative stress in cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:6002–8. doi: 10.3390/ijms15046002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharyya A, Chattopadhyay R, Mitra S, Crowe SE. Oxidative stress: An essential factor in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal mucosal diseases. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:329–54. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00040.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7915–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sosa Torres ME, Saucedo-Vazquez JP, Kroneck PM. The dark side of dioxygen. In: Kroneck PM, Torres ME, editors. Sustaining Life on Planet Earth: Metalloenzymes Mastering Dioxygen and Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 15. Springer; 2014. pp. 1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poljsak B, Šuput D, Milisav I. Achieving the balance between ROS and antioxidants: When to use the synthetic antioxidants. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:956792. doi: 10.1155/2013/956792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardo-Andreu GL, Philip SJ, Riaño A, Sánchez C, Viada C, Núñez-Sellés AJ, et al. Mangifera indica L. (Vimang) protection against serum oxidative stress in elderly humans. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:158–64. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice-Evans C, Burdon R. Free radical-lipid interactions and their pathological consequences. Prog Lipid Res. 1993;32:71–110. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(93)90006-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandra K, Salman AS, Mohd A, Sweety R, Ali KN. Protection against FCA induced oxidative stress induced DNA Damage as a model of arthritis and in vitro anti-arthritic potential of Costus speciosus rhizome extract. Int J Pharm Pharm Res. 2015;7:383–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and cancer: Have we moved forward? Biochem J. 2007;401:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonomini F, Tengattini S, Fabiano A, Bianchi R, Rezzani R. Atherosclerosis and oxidative stress. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:381–90. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajan I, Rabindran R, Jayasree PR, Kumar PR. Antioxidant potential and oxidative DNA damage preventive activity of unexplored endemic species of Curcuma. Indian J Exp Biol. 2014;52:133–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Percival M. Antioxidants. Clin Nutr Insights. 1998;31:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shebis Y, Iluz D, Kinel-Tahan Y, Dubinsky Z, Yehoshua Y. Natural antioxidants: Function and sources. Food Nutr Sci. 2013;4:643–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyler VE. The Honest Herbal. 3rd ed. New York: Pharmaceutical Products Press, Haworth Press (Birgharmton); 1993. p. 275. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prakash S, Jain AK. Antifungal activity and preliminary phytochemical studies of leaf extract of Solanum nigrum Linn. Int J Pharm Sci. 2011;3:352–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan P, Lou H. Effects of polyphenols from grape seeds on oxidative damage to cellular DNA. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;267:67–74. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000049366.75461.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satish AB, Deepa RV, Nikhil CT, Rohan VG, Ashwin AT, Parinita PS. Bioactive constituents, ethnobotany and pharmacological prospectives of Cassia tora Linn. Int J Bioassays. 2013;2:1421–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain S, Patil UK. Phytochemical and pharmacological profile of Cassia tora Linn.– An overview. Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2010;1:430–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gulia Y, Choudhary M. Antiulcer activity of hydroalcoholic extract of Cassia tora Linn using ethanol induced ulcer. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012;4:160–3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yen GC, Chuang DY. Antioxidant properties of water extracts from Cassia tora L. in relation to the degree of roasting. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:2760–5. doi: 10.1021/jf991010q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Awasthi VK, Mahdi F, Chander R, Khanna AK, Saxena JK, Singh R, et al. Hypolipidemic Activity of Cassia tora seeds in hyperlipidemic rats. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2015;30:78–83. doi: 10.1007/s12291-013-0412-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jang YS, Baek BR, Yang YC, Kim MK, Lee HS. Larvicidal activity of leguminous seeds and grains against Aedes aegypti and Culex pipiens pallens. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2002;18:210–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong E, Francis CM. Flavonoids in genotypes of Trifolium subterraneum I, The normal flavonoids pattern of the geraldton variety. Phytochemistry. 1968;7:2123–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Tahir A, Satti GM, Khalid SA. Antiplasmodial activity of selected sudanese medicinal plants with emphasis on Acacia nilotica. Phytother Res. 1999;13:474–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(199909)13:6<474::aid-ptr482>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh S, Sameer HS. Evaluation of antimicrobial and topical anti-inflammatory activity of extracts and formulations of Cassia tora leaves. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;5:920–2. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim M, Lim SJ, Lee HJ, Nho CW. Cassia tora seed extract and its active compound aurantio-obtusin inhibit allergic responses in IgE-mediated mast cells and anaphylactic models. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:9037–46. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yadav JP, Arya V, Yadav S, Panghal M, Kumar S, Dhankhar S. Cassia occidentalis L.: A review on its ethnobotany, phytochemical and pharmacological profile. Fitoterapia. 2010;81:223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park TH, Kim DH, Kim CH, Jung HA, Choi JS, Lee JW, et al. Peroxynitrite scavenging mode of alaternin isolated from Cassia tora. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2004;56:1315–21. doi: 10.1211/0022357044229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malabade R, Ashok T. Cassia tora A potential cognition enhancer in rats with experimentally induced amnesia. J Young Pharm. 2015;7:455–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sreelakshmi V, Abraham A. Polyphenols of Cassia tora leaves prevents lenticular apoptosis and modulates cataract pathology in Sprague-Dawley rat pups. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;81:371–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muslim NS, Nassar ZD, Aisha AF, Shafaei A, Idris N, Majid AM, et al. Antiangiogenesis and antioxidant activity of ethanol extracts of Pithecellobium jiringa. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:210. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sreerama YN, Sashikala VB, Pratape VM. Variability in the distribution of phenolic compounds in milled fractions of chickpea and horse gram: Evaluation of their antioxidant properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:8322–30. doi: 10.1021/jf101335r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prieto P, Pineda M, Aguilar M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: Specific application to the determination of Vitamin E. Anal Biochem. 1999;269:337–41. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li P, Huo L, Su W, Lu R, Deng C, Liu L, et al. Free radical-scavenging capacity, antioxidant activity and phenolic content of Pouzolzia zeylanica. J Serbian Chem Soc. 2011;76:709–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM, Aruoma OI. The deoxyribose method: A simple “test-tube” assay for determination of rate constants for reactions of hydroxyl radicals. Anal Biochem. 1987;165:215–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oyaizu M. Studies on products of browning reaction antioxidative activities of products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn J Nutr. 1986;44:307–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghanta S, Banerjee A, Poddar A, Chattopadhyay S. Oxidative DNA damage preventive activity and antioxidant potential of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni) Bertoni, a natural sweetener. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:10962–7. doi: 10.1021/jf071892q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Girish TK, Vasudevaraju P, Prasada Rao UJ. Protection of DNA and erythrocytes from free radical induced oxidative damage by black gram (Vigna mungo L.) husk extract. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1690–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang HL, Chen SC, Chang NW, Chang JM, Lee ML, Tsai PC, et al. Protection from oxidative damage using Bidens pilosa extracts in normal human erythrocytes. Food Chem Toxicol. 2006;44:1513–21. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agrawal D, Sultana P. Biochemical and structural alterations in rat erythrocytes due to hexachlorocyclohexane exposure. Food Chem Toxicol. 1993;31:443–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(93)90161-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoyer LC, Bucana C. Principles of immuno-electron microscopy. In: Marchalories JJ, Warr GW, editors. Antibodies as a Tool. London: John Wiley; 1982. pp. 257–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tedesco I, Russo M, Russo P, Iacomino G, Russo GL, Carraturo A, et al. Antioxidant effect of red wine polyphenols on red blood cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2000;11:114–9. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(99)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nijveldt RJ, van Nood E, van Hoorn DE, Boelens PG, van Norren K, van Leeuwen PA. Flavonoids: A review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:418–25. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh S, Singh SK, Yadav A. A review on Cassia species: Pharmacological, traditional and medicinal aspects in various countries. Am J Phytomed Clin Ther. 2013;1:291–312. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kandaswami C, Middleton E., Jr Free radical scavenging and antioxidant activity of plant flavonoids. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;366:351–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1833-4_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scalbert A, Manach C, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Dietary polyphenols and the prevention of diseases. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2005;45:287–306. doi: 10.1080/1040869059096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dai J, Mumper RJ. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules. 2010;15:7313–52. doi: 10.3390/molecules15107313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hollman PC, Katan MB. Dietary flavonoids: Intake, health effects and bioavailability. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37:937–42. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Bolwell PG, Bramley PM, Pridham JB. The relative antioxidant activities of plant-derived polyphenolic flavonoids. Free Radic Res. 1995;22:375–83. doi: 10.3109/10715769509145649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Paganga G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:933–56. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mandal S, Rath J. Phytochemical and antioxidant activities of ethnomedicinal plants used by fisher folks of Chilika lagoon for indigenous phytotherapy. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2015;3:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khatak S, Sharma P, Laller S, Malik DK. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and phytochemical property of Cassia tora against pathogenic microorganisms. J Pharm Res. 2014;8:1279–84. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pellegrini N, Serafini M, Colombi B, Del Rio D, Salvatore S, Bianchi M, et al. Total antioxidant capacity of plant foods, beverages and oils consumed in Italy assessed by three different in vitro assays. J Nutr. 2003;133:2812–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.9.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chakrabarty K, Chawla H. Terpenoids and phenolics from Cassia species stem bark. Indian J Chem. 1983;22:1165–6. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim SY, Kim JH, Kim SK, Oh MJ, Jung MY. Antioxidant activities of selected oriental herb extracts. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1994;71:633–40. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gutteridge JM. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidants as biomarkers of tissue damage. Am Assoc Clin Chem. 1995;41:1819–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hochstein P, Atallah AS. The nature of oxidants and antioxidant systems in the inhibition of mutation and cancer. Mutat Res. 1988;202:363–75. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(88)90198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kappus H. Lipid peroxidation – Mechanism and biological relevance. In: Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, editors. Free Radicals and Food Additives. London UK: Taylor and Francis; 1991. pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sikder K, Sinha M, Das N, Das DK, Datta S, Dey S. Moringa oleifera leaf extract prevents in vitro oxidative DNA damage. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2013;6:159–63. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dluya T, Daniel D, Gaiuson YW. Comparative biochemical evaluation of leaf extracts of Ficus sycomorus and Piliostigma thonningii plant. JMPS. 2015;3:32–7. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhoyar MS, Mishra GP, Pradeep KN, Srivastava RB. Estimation of antioxidant activity and total phenolics among natural populations of Caper (Capparis spinosa) leaves collected from cold arid desert of trans-Himalayas. Aust J Crop Sci. 2011;5:912–9. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arya V, Yadav JP. Antioxidant activity and total phenolics in leaves extracts of Cassia tora L. Pharmacol Online. 2010;2:1030–6. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dalar A, Uzun Y, Mukemre M, Turker M, Konczak I. Centaurea karduchorum Boiss. from Eastern Anatolia: Phenolic composition, antioxidant and enzyme inhibitory activities. J Herb Med. 2015;2015:211–6. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dudonné S, Vitrac X, Coutière P, Woillez M, Mérillon JM. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:1768–74. doi: 10.1021/jf803011r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumari S, Chandra BS. Antioxidant ability of medicinal plants against stress induced by H2O2 and their role as antimicrobial agent. J Pharm Res. 2011;4:2279–81. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Supriya MS, Nagamani JE, Komal Kumar J. Cytoprotective and antimicrobial activities of stem extract of Caesalpinia mimosoides. Int J Pharm Biol Res. 2013;4:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Linderkamp O, Kiau U, Ruef P. Cellular and membrane deformability of red blood cells in protein infants with and without growth retardation. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 1997;17:279–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lim HW, Wortis M, Mukhopadhyay R. Stomatocyte-discocyte-echinocyte sequence of the human red blood cell: Evidence for the bilayer- couple hypothesis from membrane mechanics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16766–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202617299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sheetz MP, Singer SJ. Biological membranes as bilayer couples. A molecular mechanism of drug-erythrocyte interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:4457–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.11.4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ignacimuthu S, Dhanasekaran M, Agastian P. Potential hepatoprotective activity of ononitol monohydrate isolated from Cassia tora L. on carbon tetra chloride induced hepatotoxicity in wistar rats. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:891–5. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shinobu-Mesquita CS, Bonfim-Mendonça PS, Moreira AL, Ferreira IC, Donatti L, Fiorini A, et al. Cellular structural changes in Candida albicans caused by the hydroalcoholic extract from Sapindus saponaria L. Molecules. 2015;20:9405–18. doi: 10.3390/molecules20059405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang J, Wang W, Sun YJ, Hu M, Li F, Zhu DY. Neuroprotective effect of curcumin on focal cerebral ischemic rats by preventing blood-brain barrier damage. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;561:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ray PS, Maulik G, Cordis GA, Bertelli AA, Bertelli A, Das DK. The red wine antioxidant resveratrol protects isolated rat hearts from ischemia reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:160–9. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Balasubramanian B, Pogozelski WK, Tullius TD. DNA strand breaking by the hydroxyl radical is governed by the accessible surface areas of the hydrogen atoms of the DNA backbone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9738–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guha G, Rajkumar V, Ashok Kumar R, Mathew L. Therapeutic potential of polar and non-polar extracts of Cyanthillium cinereum in vitro. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:784826. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rajkumar V, Guha G, Ashok Kumar R, Mathew L. Evaluation of antioxidant activities of Bergenia ciliata rhizome. Rec Nat Prod. 2010;4:38–48. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Russo A, Izzo AA, Cardile V, Borrelli F, Vanella A. Indian medicinal plants as antiradicals and DNA cleavage protectors. Phytomedicine. 2001;8:125–32. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee JC, Kim HR, Kim J, Jang YS. Antioxidant property of an ethanol extract of the stem of Opuntia ficus-indica var. saboten. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:6490–6. doi: 10.1021/jf020388c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]