Abstract

Marfan syndrome (MFS) is the autosomal dominant-inherited multisystem connective-tissue disorder, with a reported incidence of 1 in 10,000 individuals and equal distribution in both genders. The main clinical manifestation of this disorder consists of an exaggerated length of the upper and lower limbs, hyperlaxity, scoliosis, alterations in the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems, and atypical bone overgrowth. Orofacial manifestations such as high-arched palate, hypodontia, long narrow teeth, bifid uvula, mandibular prognathism, and temporomandibular disorders are also common. Early diagnosis of MFS is essential to prevent the cardiovascular complications and treatment of orofacial manifestations, thus to increase the quality of life of the patient.

KEYWORDS: Autosomal dominant, Marfan syndrome, oral manifestation

INTRODUCTION

Marfan syndrome (MFS) is a rare autosomal dominant genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the gene encoding (fibrillin 1, chromosome 15q15–21.3), a glycoprotein that is an integral part of the connective tissue in the body.[1] The prevalence has been estimated as 1 in 5–10,000 individuals. The main target organs of this disorder are cardiovascular system, eyes, and skeleton. The diagnosis is commonly considered in a young person with a tall, thin body habitus, long limbs, arachnodactyly, pectus deformities, and sometimes scoliosis.

Out of proportioned overgrowth of the long bones is observed which is frequently considered to be the most highlighted and evident skeletal feature. The main ocular abnormality is the dislocation of the lens; however, several other pathologies can be developed such as cataracts or glaucoma. The cardiovascular disorder most frequently presented is the dilatation of the ascending aorta at the aortic sinuses level associated with aortic valve incompetence leading to aortic dissection.[2,3] Cardiovascular complications constitute the main cause of mortality for patients with MFS.

Craniofacial features of MFS consist of narrow cranium, with dolichocephalic features, deep palatal vault, and retrognathia or micrognathia of the upper jaw. This may lead to posterior crossbite. In addition, the maxillary hypoplasia generally causes dental crowding. Teeth may exhibit hypoplastic enamel with increased caries incidence in these patients. Pulp stones are common findings in radiographs of teeth in MFS. The gingival index shows significantly higher values even without much local irritants. Temporomandibular alterations are more prevalent because of articular deformation and ligament hyperlaxity.[4]

The diagnosis of MFS relies on defined clinical criteria (Ghent nosology) of 1996 which was modified in 2010, outlined by panel of international experts to facilitate accurate recognition of this genetic syndrome and to improve patient management. Diagnosis is further complicated by age-dependent clinical manifestations and is the reason many younger patients with suspected MFS do not fulfill the clinical diagnostic criteria.[5] Nevertheless, they should be offered repeat clinical evaluations and periodic follow-up. In addition, a detailed medical and family history and a complete physical, cardiovascular, and ophthalmologic examination are mandatory for all patients with features suggestive of MFS.

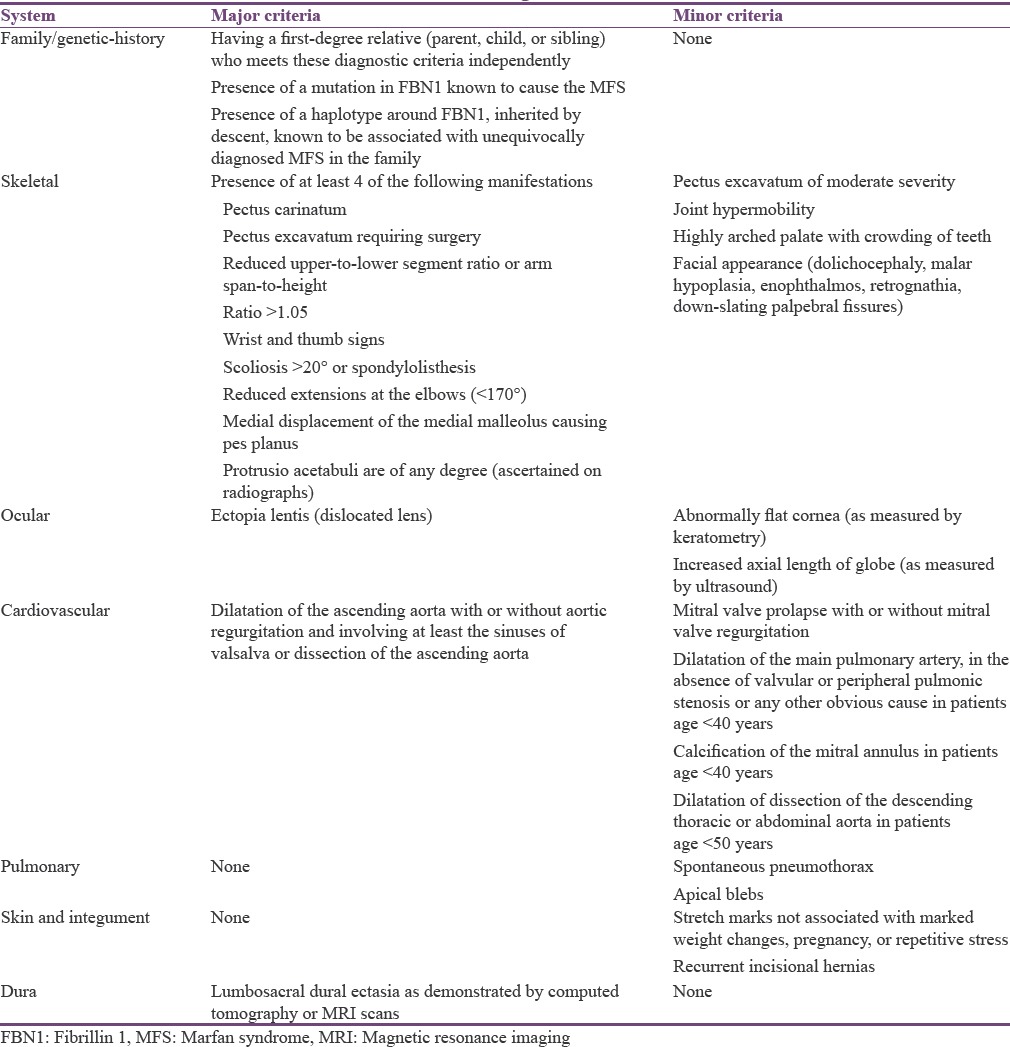

Despite these challenges, the diagnosis can be established by a comprehensive clinical evaluation and by applying Ghent diagnostic criteria. The Ghent criteria are based on family/genetic-history, involvement of organ systems (primarily skeletal, cardiovascular, and ocular), and whether the clinical sign is major or minor [Table 1].[6] Major criteria are specific for MFS and are rarely present in the general population. According to Ghent nosology, MFS in a patient with unequivocal family history is diagnosed when there is major involvement in one organ system (skeletal, cardiovascular, or ocular) and involvement of a second organ system. If the patient has no first-degree relative who is unequivocally affected by MFS syndrome, the patient must have major criteria in at least two different organ systems and involvement of a third (skeletal, cardiovascular, and ocular) to be diagnosed with MFS.[4]

Table 1.

Ghent diagnostic criteria

CASE REPORT

A 22-year-old male patient reported to the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology for routine dental checkup. His medical and dental histories were not contributory. His family history revealed recurrent ophthalmic and cardiac disorders for his father.

On general examination, vital signs were within normal limits. The patient had long slender upper and lower extremities, flat foot [Figure 1], and thin body habitus with the lower segment (LS) of the body greater than the upper segment (US). Fingers of upper limbs were long and slender (arachnodactyly) [Figure 2]. His height was 164 cm with arm span of 159 cm (arm span height) and body weight was 47 kg, and a ratio of upper to LS of 0.75. The chest was flat with prominent ribs. Scoliosis was another truncal finding. Wrist (walker's sign) [Figure 3] and thumb or Steinberg sign [Figure 4] were positive. Extraorally, a long and narrow face with a convex profile was observed [Figure 5]. Intraoral examination revealed high arch palate [Figure 6] with crowding of anterior teeth. The overall periodontal status was poor.

Figure 1.

Flat foot

Figure 2.

Upper limbs were long and slender (arachnodactyly)

Figure 3.

Wrist (walker's sign)

Figure 4.

Thumb or Steinberg sign

Figure 5.

Long and narrow face with a convex profile

Figure 6.

High arch palate

Routine blood and urine investigations were within normal range. Chest X-ray also did not show significant changes. Ophthalmic examination showed ectopia lentis on the right eye with iridodonesis (tremor of iris). On the left eye, aphakia (absence of lens) was noticed due to complete dislocation of lens floating free within the vitreous cavity. His echocardiogram was normal and there was no evidence of pulmonary manifestations.

Based on the history, examinations, and ophthalmologic findings, the case was diagnosed as MFS. Differential diagnosis considered was Beals syndrome (congenital and contractural arachnodactyly) and homocystinuria, because of the similarities clinical manifestations with MFS. Patients with Beals syndrome exhibit skeletal features similar to those of MFS with long, slender limbs (dolichostenomelia) with arachnodactyly. However, in Beals syndrome, joint contractures rather than looseness of the joints and absence of eye and heart involvement differentiates it from MFS. Homocystinuria also shows MFS like features (dolichostenomelia, arachnodactyly, tall stature, and ophthalmologic disorders) along with osteoporosis, mental retardation, and history of thromboembolic phenomena. However, the subluxation of the eye lens is downward, contrary to upward dislocation in MFS. Some patient may have no discernible clinical manifestations, except for tall stature. In this situation, serum and urine amino acid concentrations should be determined for differentiation of homocystinuria.

DISCUSSION

MFS was first described by the pediatrician Antoine Bernard-Jean Marfan in 1896 who reported a case characterized by out of proportioned length of the lower limbs and fingers. About 15% of cases are sporadic and apparently are the result of mutation occurring in a germ cell of one or other parent; the other 85% of patients have one parent affected.[7] In our case also patient's father had ophthalmic and cardiac manifestations.

Typical skeletal characteristics of the syndrome such as the elongation of the extremities because of an exaggerated overgrowth of the long bones are observed in this patient. Excessive length of tubular bones results in dolichostenomelia (disproportionate long and thin extremities) and arachnodactyly or spidery fingers. Dolichostenomelia is defined by an US-to-LS ratio of at least 2 standard deviation below the mean or arm-span-to-height ratio of at least 1.05. Hyperextensibility of joints with habitual dislocations is common.[1,8] Kyphosis or scoliosis may be present. In eyes, bilateral ectopia lentis caused by weakening or rupture of suspensory ligaments are common. Myopia and glaucoma are the other ophthalmologic manifestations of MFS. Skin striae may occur over the shoulders and buttocks. Inguinal hernias are also reported. Pulmonary manifestations include spontaneous pneumothorax and apical blebs.[2] The chest radiograph may show evidence of cardiomegaly, broadening of upper mediastinum, and distortion of aortic knuckle (in 60% of patients). A left-sided pleural effusion is common. Electrocardiogram may show left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with hypertension.[3]

Among maxillofacial disorders, periodontal diseases are presented with a higher frequency and severity in these patients. Regarding temporomandibular joint disorders in MFS patients, Bauss et al. reported a high prevalence of 51.6% for articular dysfunction and 24.2% for subluxation.

Preimplantation and prenatal diagnosis by molecular studies has been accomplished. Genetic testing is reported to be helpful.[4] During the third trimester, diagnosis can be strongly suspected on the basis of ultrasonographic analysis of limb lengths. Lumbosacral dural sac dimensions can be measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Dural ectasia is a good marker for MFS.

CONCLUSION

The Ghent nosology remains the most effective way of diagnosing or excluding MFS. However, when evaluating patients for MFS, clinicians need to be aware that symptoms and signs are age-dependent and manifestations of the syndrome vary among patients. Dentists play an important role in the early diagnosis of MFS in youngsters as in the present case.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Douglas G, Faracs WF, Odolakin W. Anesthesia and Marfan's syndrome: Case report. Can J Anaesth. 1987;34:311–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03015173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basappa S, Das A. Marfan syndrome – Review. Indian J Multidiscip Dent. 2010;1:50–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pyeritz RE. The Marfan syndrome. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:481–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Coster PJ, Martens LC, De Paepe A. Oral manifestations of patients with Marfan syndrome: A case-control study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:564–72. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.121430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean JC. Marfan syndrome: Clinical diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:724–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorlin RJ, Cohen MM, Hennekam RC. Syndromes of Head and Neck. 4th ed. Calcutta: Oxford Publishers; 2001. pp. 327–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Straub AM, Grahame R, Scully C, Tonetti MS. Severe periodontitis in Marfan's syndrome: A case report. J Periodontol. 2002;73:823–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.7.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morales-Chávez MC, Rodríguez-López MV. Dental treatment of Marfan syndrome. With regard to a case. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:e859–62. doi: 10.4317/medoral.15.e859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]