Abstract

G2A, T cell death-associated gene 8 (TDAG8), ovarian cancer G protein-coupled receptor 1 (OGR1), and G protein-coupled receptor 4 (GPR4) form a group of structurally related G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) originally proposed to bind proinflammatory lipids. More recent studies have challenged the identification of lipid agonists for these GPCRs and have suggested that they function primarily as proton sensors. We compared the ability of these four receptors to modulate pH-dependent responses by using transiently transfected cell lines. In accordance with previously published reports, OGR1 was found to evoke strong pH-dependent responses as measured by inositol phosphate accumulation. We also confirmed the pH-dependent cAMP production by GPR4 and TDAG8. However, we found the activity of the human G2A receptor and its mouse homolog to be significantly less sensitive to pH fluctuations as measured by inositol phosphate and cAMP accumulation. Sequence homology analysis indicated that, with one exception, the histidine residues that were previously shown to be important for pH sensing by OGR1, GPR4, and TDAG8 were not conserved in the G2A receptor. We further addressed the pH-sensing properties of G2A and TDAG8 in a cellular context where these receptors are coexpressed. In thymocytes and splenocytes explanted from receptor-deficient mice, TDAG8 was found to be critical for pH-dependent cAMP production. In contrast, G2A was found to be dispensable for this process. We conclude that members of this GPCR group exhibit differential sensitivity to extracellular protons, and that expression of TDAG8 by immune cells may regulate responses in acidic microenvironments.

Keywords: cyclic AMP, inositol phosphate, proton sensing

G2A (1), T cell death-associated gene 8 (TDAG8) (2), ovarian cancer G protein-coupled receptor 1 (OGR1) (3), and G protein-coupled receptor 4 (GPR4) (4) are members of a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) subfamily (referred in this article as the “G2A group”) defined by sequence homology analysis. Initially identified as orphan receptors, these GPCRs were later proposed to recognize lysolipid molecules. The naturally occurring lipid mediator sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPC) was shown to bind with high affinity to OGR1 (5). The related lipid, lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), and SPC were claimed by Kabarowski et al. (6) as high-affinity ligands for G2A. These two lipids were later claimed to bind to GPR4 (7). No independent reports confirming the identification of LPC- or SPC-specific GPCRs are available.

We have been unable to reproduce experiments produced by our collaborators indicating specific binding of LPC to G2A-expressing cells (6). This inability for replication led a subset of the authors to conclude that the paper by Kabarowski et al. (6) incorrectly claimed a high-affinity ligand–receptor relationship for LPC and G2A, and the paper has been retracted. Data from Kabarowski et al. (6) regarding chemotaxis of G2A-expressing immune cells to LPC have been confirmed and extended in our laboratory (8, 9). We have also been able to reproduce the G2A-dependent extracellular receptor kinase activation by LPC (6) and have further examined the LPC-dependent regulation of G2A cellular trafficking (L.W., C.G.R., L. Yang, L. Bentolila, M. Riedinger, and O.N.W., unpublished data). Other groups have identified additional biological effects of LPC that depend on G2A expression. These effects include augmentation of G2A-dependent apoptosis in HeLa cells (10), inhibition of actin stress fiber formation (11), up-regulation of CXCR4 in human helper T cells (12), and protection of mice against lethal septic shock (13). Ligand independent effects mediated by G2A, including accumulation of cells at G2 and M and a partial block in the progression of mitosis, suppression of contact inhibition, foci formation, and assembly of actin stress fibers, have also been observed (1, 10, 11, 14, 15). We cannot rule out a requirement for a weak direct interaction between LPC and G2A, but a more likely explanation would postulate an indirect effect of LPC on G2A, mediated by a yet-to-be-identified lysolipid sensor.

TDAG8 was proposed by Im et al. (16) to function as a specific receptor for galactosylsphingosine (psychosine, PSY) based on its requirement for PSY-mediated formation of multinucleated cells. No binding data supporting a ligand–receptor relationship between PSY and TDAG8 have been reported.

More recently, a series of published reports examined the effects of extracellular pH on the constitutive activities of OGR1 and related receptors. Ludwig et al. (17) showed that exposure of OGR1- or GPR4-transfected CCL39 or HEK293 cell lines to acidic pH activated the production of inositol phosphate (IP) and cAMP, respectively. These observations led the authors to conclude that OGR1 and GPR4 function primarily as proton sensors. Significantly, this study did not detect any effects of previously proposed lipid ligands, SPC or LPC, on the proton-mediated activation of OGR1 or GPR4.

Wang et al. (18) reported that TDAG8 functions as a proton sensor. The authors showed that production of cAMP by cell lines overexpressing TDAG8 is markedly enhanced by exposure to an acidic pH. PSY was found to partially antagonize the TDAG8-dependent pH response. Partial inhibitory effects of PSY on the pH-mediated activation of GPR4 and OGR1 were also observed in this study.

Data presented by Murakami et al. (11) support a proton-sensing ability for human G2A. This receptor was shown to mediate acidic pH-sensitive production of IP and activation of the zif268 promoter. In PC12h and COS-7 cell lines, IP production at acidic pH (6.4 and 6.8, respectively) was ≈2- to 3-fold above levels seen at physiological pH (7.4). Inhibitory effects of 10 μM LPC on the pH-induced IP production led the authors to propose that this lipid acts as an antagonist during G2A activation.

A common thread among these studies was the dependence of pH sensing on the presence of histidines in the predicted extracellular regions of these receptors. Using a computational 3D model of OGR1, Ludwig et al. (17) predicted several hydrogen-bond interactions occurring between unprotonated histidines. Under alkaline conditions these interactions could stabilize the receptor in an inactive state. Exposure to an acidic pH would destabilize the hydrogen bonds, switching the receptor to its active conformation. Conversion of several histidines (H17, H20, H84, H169, and H269) to phenylalanines by using site-directed mutagenesis reduced the proton-sensing ability of OGR1. Sequence alignment analysis (clustalw) indicates that two of these critical residues (H17 and H20) are conserved in TDAG8 but are not present in G2A orthologues from multiple species including human, mouse, rat, chimpanzee, and zebrafish (C.G.R. and O.N.W., unpublished data). Murakami et al. (11) identified one histidine in human G2A (H174) that was partially required for pH sensing. Interestingly, the corresponding histidine in OGR1 (H159) was previously shown (17) not to be important for OGR1 pH sensing, and this residue is not conserved in the mouse G2A orthologue.

In the current study we quantitatively compared the proton-sensing abilities of all four members of the G2A group. Using transiently transfected 293T cells or RAT-1 cells chronically expressing these receptors, we confirmed previously reported pH-sensing activities of OGR1, GPR4, and TDAG8. In contrast, the constitutive activities of overexpressed human or mouse G2A were largely pH insensitive. A possible explanation for these findings was the low number of histidines required for pH-sensing in G2A. We also analyzed the pH-dependent responses of explanted thymocytes and splenocytes, which coexpress G2A and TDAG8. Using immune cells from WT and receptor-deficient mice, we found TDAG8, but not G2A, to be critically required for pH-induced cAMP production. Collectively our results suggest that G2A and TDAG8 respond differentially to protons and also define a potential previously uncharacterized mechanism for pH sensing by cells of the immune system.

Materials and Methods

Reagents. 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (no. I5879), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2, no. P0409), and dexamethasone (DEX, no. D8893) were purchased from Sigma. Radioactive myo-[3H]inositol was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences (no. TRK883).

GPCR Expression Vectors. The ORFs of human G2A (huG2A), mouse G2A (muG2A), TDAG8, OGR1, and GPR4 were tagged with EGFP at their C termini and cloned in the murine stem cell virus vector (19) by using standard molecular biology techniques. clustalw (www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw) was used for sequence alignments.

Cell Culture and Transfections. HEK 293T (293T) cells were maintained in DMEM, containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS and l-glutamine, and grown at 37°C, 8% CO2, in a humidified incubator. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, no.11668) was used for transient transfection of 293T cells. The expression of the GPCR-EGFP fusion proteins was determined 24 h posttransfection by using a FACScan instrument and the cellquest software (Becton Dickinson) (data not shown). RAT-1 cells chronically expressing equivalent levels of the GPCR-EGFP fusion proteins were generated by retroviral transduction, followed by FACS sorting (J.M. and O.N.W., unpublished data).

Fluorescent Microscopy Analysis of GPCR Localization in Transfected 293T Cells. 293T cells grown on polylysine-coated coverslips were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and washed with PBS. Coverslips were mounted on slides by using Slowfade (Molecular Probes, no. S2828). Specimens were analyzed on a TCS SP2 AOBS laser-scanning confocal inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, Exton, PA), equipped with a ×63 oil-immersion objective (HCX PL APO, NA 1.40) and a 488-nm laser line.

Buffers and pH Adjustments. As described in ref. 11, DMEM (Irvine Scientific, no. 9418) containing 0.1% fatty acid-free BSA (Sigma, no. A8806–5G), 0.5 g/liter sodium bicarbonate, and either 20 mM Hepes (Wako Biochemicals, Osaka, no. 342-01375) (DMEM/Hepes) or 7.5 mM each of Hepes, EPPS (Wako Biochemicals, no. 346–03193), and Mes (Wako Biochemicals, no. 349–01623) (DMEM/Hepes/4-(2-hydroxyethyl)1-piperazine-propanesulfonic acid/Mes, DMEM-HEM) were used to achieve a wide pH range. We recorded pH values at 37°C by using a Fisher Scientific AR25 meter with a precision of ±0.05.

Intracellular IP and cAMP Accumulation. IP and cAMP were quantified as described in refs. 11 and 18. A detailed description is provided in Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR. DNA-free RNA was prepared from thymocytes and splenocytes by using the Absolutely RNA Microprep Kit from Stratagene (no. 400800). RNA was reverse-transcribed by using oligo dT primers and the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, no. 11904-018). The PCR conditions and the primers used for amplification are in Supporting Materials and Methods.

Mice. Single-cell suspensions of thymocytes and splenocytes were prepared from 4- to 8-week-old female WT (C57/BL6 or BALB/c), G2A-deficient (20) (backcrossed for 10 generations on the BL/6 strain), and TDAG8-deficient mice (C.G.R., A.N., J.M., R. Lim, and O.N.W., unpublished data). Briefly, for the generation of TDAG8-deficient mice, a genomic DNA fragment containing exon 2-derived tdag8 coding sequences was replaced by a construct encoding promoterless IRES-EGFP sequences and the neomycin resistance cassette flanked by loxP sites. TDAG8-deficient mice were backcrossed for six generations on the BL/6 and BALB/c strains. All mice were bred and maintained according to the guidelines of the Department of Laboratory and Animal Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Data Analysis. Graphs were constructed by using prism software (version 4.02 GraphPad, San Diego). Data are presented as mean ± standard error.

Results

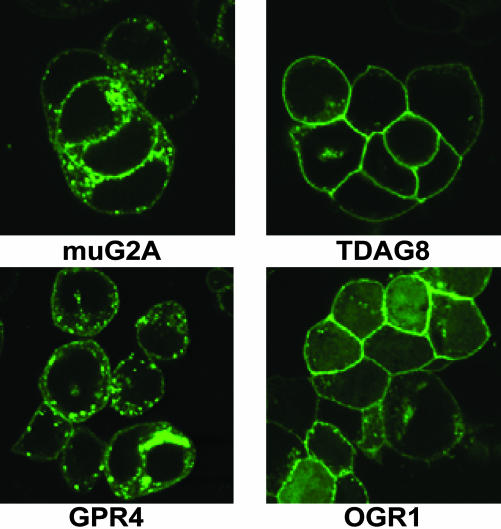

Quantitative Variations in pH-Sensitivities of Ectopically Overexpressed Members of the G2A Group. To directly compare proton-induced responses, cDNA constructs encoding the mouse OGR1, GPR4, TDAG8, and G2A (muG2A) receptors, as well as the human G2A orthologue (huG2A), were transiently transfected in 293T cells. The GPCRs were expressed as EGFP fusion proteins, with the fluorescent tag located at their C termini. Comparable levels of receptor expression were achieved 24 h posttransfection for TDAG8, huG2A, and muG2A, whereas OGR1 and GPR4 levels were ≈2- to 3-fold higher, as revealed by FACS and Western blot analyses (data not shown). Cell surface expression of all receptors could be detected by laser-scanning confocal fluorescent microscopy examination (Fig. 1), when cells were grown in 10% serumcontaining medium. Although huG2A (data not shown), TDAG8, and OGR1 were predominantly localized on the plasma membrane, significant pools of intracellular receptors were detected in muG2A- and GPR4-transfected cells (Fig. 1). According to previous studies (11, 17, 18), we used the production of the secondary messengers IP and cAMP to interrogate the function of ectopically overexpressed receptors. IP production provided a measure of G2A and OGR1 activity, and cAMP was used to evaluate TDAG8 and GPR4. Because a previous report (10) demonstrated the ability of G2A to activate the Gαs-adenylyl cyclase pathway, we also measured the production of cAMP in cells overexpressing the human and mouse G2A receptors.

Fig. 1.

Localization of GPCR-EGFP fusion proteins ectopically overexpressed in 293T cells. 293T cells expressing muG2A-, TDAG8-, OGR1-, and GPR4-EGFP fusion proteins were evaluated by confocal fluorescent microscopy as described in Materials and Methods.

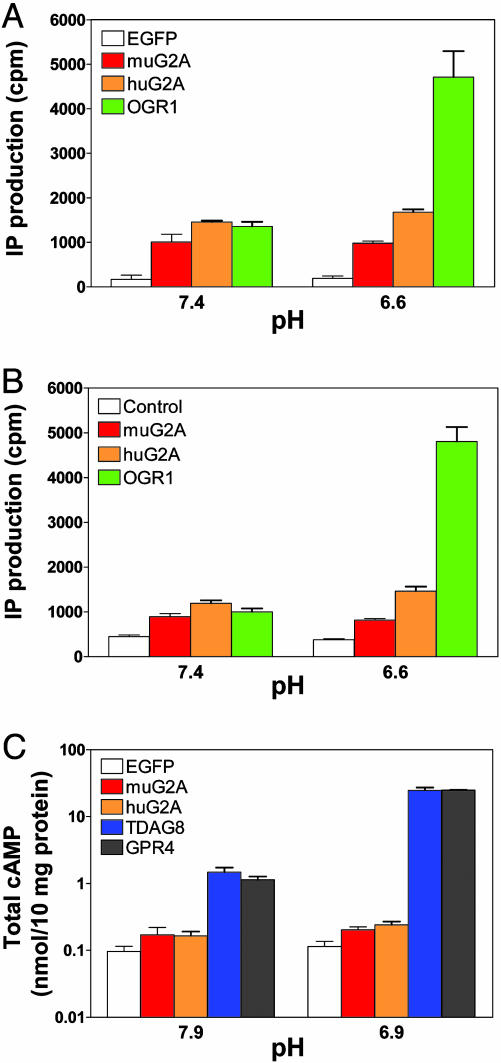

Fig. 2A shows the IP production by cells transfected with muG2A, huG2A, OGR1, or control (EGFP) vectors. These cells were exposed to physiological pH (7.4) or to acidic pH (6.6), in the absence of exogenously added ligand. At pH 7.4, we noted an ≈3- to 5-fold increase in IP production by G2A-(mouse and human) and OGR1-transfected cells versus control cells, indicating that these GPCR-EGFP fusion proteins have significant constitutive activity. In agreement with findings in ref. 17, exposure of cells to pH 6.6 induced an additional 4-fold increase in IP production by OGR1-transfected cells. Although we have consistently observed a small increase (≈20%) in the activity of huG2A at acidic pH, the constitutive activity of muG2A was found to be pH-insensitive. Importantly, an almost identical pattern of IP production was detected in RAT-1 cells engineered to chronically express equivalent levels of these GPCRs (Fig. 2B). Exposure of muG2A- and huG2A-expressing 293T cells to a range of acidic pH (6.9, 6.4, 5.9, 5.4, and 4.9) also failed to increase IP production (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

IP and cAMP production by GPCR-expressing cells exposed to acidic pH. IP production by transfected 293T (A) or retroviral-transduced RAT-1 cells (B) was measured after exposure to DMEM-HEM solutions with different pH, as described in Materials and Methods. (C) cAMP levels in transfected 293T cells exposed to acidic pH. Note the use of a logarithmic scale to display the range of cAMP production. Each experimental sample was done in duplicate or triplicate. These data were repeated in a similar pattern in two (IP production) or three (cAMP production) independent experiments.

Using the 293T overexpression system we also investigated pH-induced cAMP production by muG2A-, huG2A-, TDAG8-, GPR4-, and control (EGFP)-transfected cells. As shown in Fig. 2C (note the log scale used to display cAMP levels), under both alkaline (pH 7.9) and acidic (pH 6.9) conditions, muG2A and huG2A induced an ≈2-fold increase in cAMP production over control cells. In contrast, even at alkaline pH, production of cAMP by TDAG8- and GPR4-expressing cells was ≈10-fold higher than control cells. Decreasing the extracellular pH to 6.9 resulted in an additional 10-fold increase in cAMP levels in GPR4- and TDAG8-transfected cells, a result in agreement with observations in refs. 17 and 18.

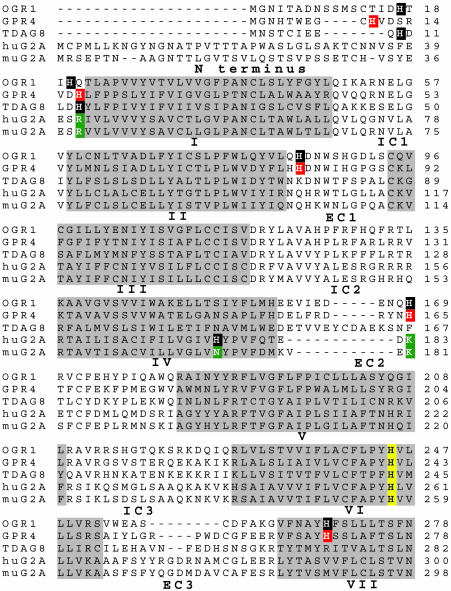

Structural Requirements for Proton-Sensing. In comparison with the production of IP and cAMP by its homologues, we found G2A to be significantly less sensitive to protons. These results could be explained if G2A lacks structural features shown to be required for pH sensitivity of the related receptors OGR1 and TDAG8 in refs. 17 and 18. To examine this hypothesis, we aligned the sequences of the members of the G2A group by using the clustalw software (Fig. 3). We then analyzed the G2A residues corresponding to histidines shown by Ludwig et al. (17) to be required for pH sensing by OGR1. All histidines (H) previously shown to be required for proton sensing by OGR1 and TDAG8 (17, 18) (highlighted in black in Fig. 3) were found to be conserved across multiple species, including mice (data not shown). In contrast, huG2A and muG2A lack many of the OGR1-defined histidines involved in pH-sensing, including those located in the N terminus (H17 and H20) and in the extracellular loops 2 (H169) and 3 (H269). Two of these residues (OGR1 H20 and H169) correspond to positively charged amino acids (arginine, R; lysine, K) in human (R42 and K183) and mouse G2A (R39 and K181, highlighted in green in Fig. 3). In a pH-independent manner, these residues could mimic the roles of protonated histidines in maintaining G2A in an active conformation. Additionally, huG2A H174 (highlighted in black in Fig. 3), a residue shown to be partially required for the pH sensitivity of this GPCR (11), is replaced by asparagine (N) in mouse (highlighted in green in Fig. 3) and rat G2A orthologues (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Several OGR1-defined histidine residues required for pH-sensing are absent in muG2A. Sequences of human OGR1, GPR4, TDAG8, and G2A (huG2A) receptors, as well as the mouse G2A (muG2A) orthologue, were aligned by using clustalw. The putative transmembrane domains (I–VII) are highlighted in gray. IC, intracellular loops; EC, extracellular loops. The histidine residues that have been shown to be important for proton sensing in OGR1 (H17, H20, H84, H169, and H269) and TDAG8 (H10 and H14) are highlighted in black (17, 18). Two of these residues, H20 and H169, are replaced by positively charged amino acids, arginine (R) and lysine (K), respectively, in G2A (highlighted in green). Residues in GPR4 that are assumed to be critical for proton-sensing based on alignment with OGR1 are highlighted in red. H174 in huG2A was found to be required for proton-sensing (highlighted in black) (11). The corresponding residue in muG2A is replaced by an asparagine (N, highlighted in green). H245 of OGR1 (highlighted in yellow) is critical for protein folding and is highly conserved in all five receptors.

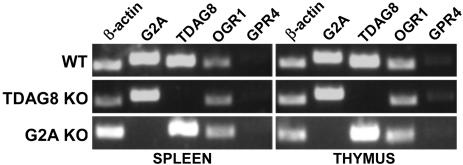

TDAG8 Is Required for pH-Dependent cAMP Production in Immune Cells. Local acidosis represents a hallmark of numerous immunopathological conditions (reviewed in ref. 21). We therefore wished to determine whether members of the G2A group could function as proton sensors in immune cells. Expression analyses with available microarray data (symatlas 0.8.0, Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation, San Diego; http://symatlas.gnf.org/SymAtlas) and RT-PCR data (Fig. 4) show that in primary and secondary lymphoid organs G2A and TDAG8 mRNA levels are higher than those of OGR1 and GPR4. A genetic approach was used to further investigate the pH-sensing abilities of G2A and TDAG8 in mouse thymocytes and splenocytes. A newly created TDAG8-deficient mouse strain (C.G.R., A.N., J.M., R. Lim, and O.N.W., unpublished data) and G2A KO mice (20) were used as a source of genetically modified immune cells (Fig. 4). Production of cAMP served as an indicator for pH sensitivity.

Fig. 4.

TDAG8 and G2A are expressed in WT immune cells and are absent in receptor-deficient mice. DNA-free RNA was prepared from thymocytes and splenocytes explanted from WT, TDAG8-deficient (TDAG8 KO), and G2A-deficient (G2A KO) mice. The expression of G2A, TDAG8, OGR1, and GPR4 was evaluated by RT-PCR. β-actin served as a positive control. The sizes of the PCR products were as follows: β-actin, ≈466 bp; G2A, ≈542 bp; TDAG8, ≈492 bp; OGR1, 442 bp; and GPR4, ≈498 bp.

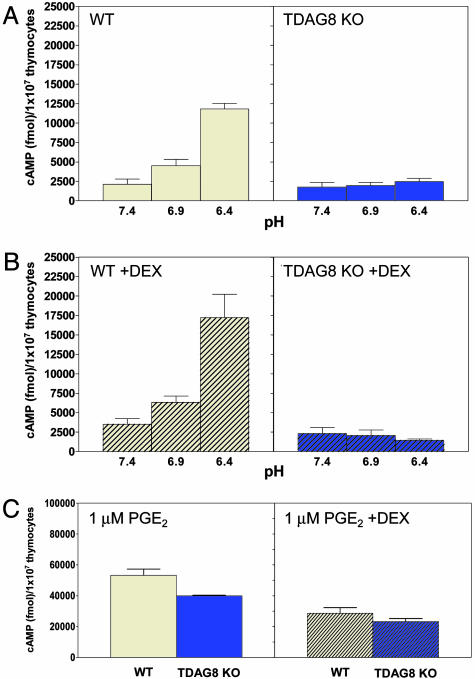

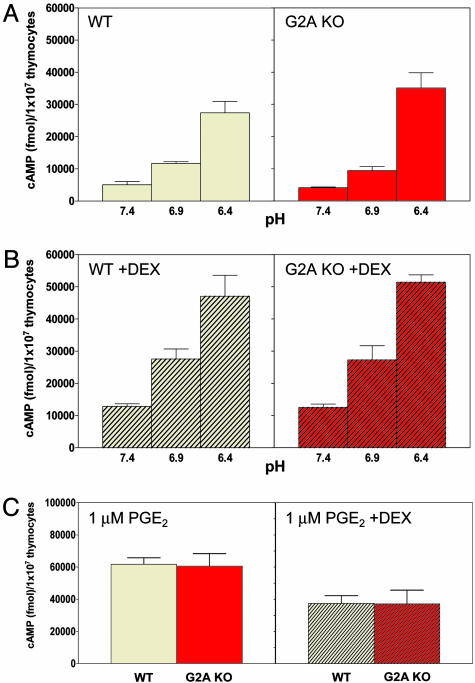

As previously shown by Wang et al. (18), 30 min of exposure of WT thymocytes from C57/BL6 mice to acidic pH induced a significant up-regulation of cAMP production (≈4- to 5-fold) (Fig. 5A). Pretreatment of cells with the synthetic corticosteroid DEX, known to up-regulate the expression of TDAG8 mRNA (2), further increased cAMP production by WT cells by ≈30–40% (Fig. 5B). In contrast, we did not detect any pH-dependent cAMP production by TDAG8 KO thymocytes (Fig. 5 A and B). Production of cAMP by G2A KO thymocytes exposed to acidic pH was indistinguishable from that of their WT counterparts (Fig. 6 A and B). Stimulation of WT, TDAG8, and G2A KO thymocytes with 1 μM PGE2 at pH 7.4, an activator of the Gαs-adenylyl cyclase signaling (18), resulted in comparable levels of cAMP (Figs. 5C and 6C). This result suggests that TDAG8-deficient cells do not have a global defect in cAMP production. Production of PGE2-induced cAMP by TDAG8 KO cells was ≈20% lower (Fig. 5C); however, this difference did not reproduce in multiple experiments. The critical role of TDAG8 for pH-induced cAMP production is not restricted to cells from the BL6 strain because examination of thymocytes from a second congenic strain (BALB/c) yielded similar results (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 5.

TDAG8 is required for pH-induced cAMP production in thymocytes. Thymocytes from WT and TDAG8-deficient (TDAG8 KO) 4- to 6-week-old female mice were incubated either in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 1 μM DEX for 4 h. Thymocytes were then exposed to DMEM-HEM solutions (pH 7.4, 6.9, and 6.4) (A and B) or 1 μM PGE2 at pH 7.4 (C) for 30 min and lysed for cAMP quantification. Data presented are representative of six independent experiments. Two to three mice per group were examined in each experiment. The total numbers of mice examined were 14 WTs and 14 TDAG8 KOs.

Fig. 6.

G2A is dispensable for pH-induced cAMP production in thymocytes. Thymocytes from WT and G2A-deficient (G2A KO) 4- to 6-week-old female mice were incubated either in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 1 μM DEX for 4 h. Thymocytes were then exposed to DMEM-HEM solutions (pH 7.4, 6.9, and 6.4) (A and B) or 1 μM PGE2 at pH 7.4 (C) for 30 min and lysed for cAMP quantification. Data presented are representative of two independent experiments. Three mice per group were examined in each experiment.

TDAG8 was previously associated with the apoptotic death of thymocytes (2, 22, 23). The lack of pH-induced cAMP production by TDAG8 KO thymocytes could be explained by differential viability of these cells during the course of the assay. However, similar percentages of early apoptotic cells (identified as Annexin V positive/7-aminoactinomycin D-negative) were found in WT and TDAG8 KO thymocytes cultures after exposure to DEX and acidic pH (data not shown).

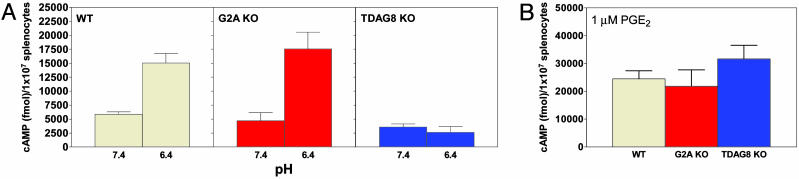

To determine whether the critical role of TDAG8 for pH-dependent cAMP accumulation in thymocytes extends to mature immune cells, we analyzed total splenocytes explanted from WT, TDAG8 KO, and G2A KO mice (all on the C57/BL6 background). Exposure of WT and G2A KO splenocytes to pH 6.4 resulted in an ≈2.5- to 3-fold increase in cAMP production compared with pH 7.4 (Fig. 7A). In contrast, production of cAMP by TDAG8 KO splenocytes was insensitive to pH. Comparable amounts of cAMP were produced in all cultures after stimulation with 1 μM PGE2 (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

TDAG8 is required for pH-induced cAMP production in splenocytes. Splenocytes from WT (Left), G2A-deficient (G2A KO) (Center), and TDAG8-deficient (TDAG8 KO) (Right) 6- to 8-week-old female mice were exposed to DMEM-HEM solutions (pH 7.4, 6.9, and 6.4) (A) or 1 μM PGE2 at pH 7.4 (B) and lysed for cAMP quantification. Data shown are representative of two to four independent experiments, each with three mice per group. A total of 12 WT, 12 TDAG8 KO, and 6 G2A KO mice were analyzed.

Discussion

Differential pH Sensitivity Among Related GPCRs. In this article we quantitatively compared the effects of acidic extracellular pH on the activities of four structurally related GPCRs, G2A, TDAG8, OGR1, and GPR4. Although several groups have recently reported the pH sensitivity of subsets of the G2A group (11, 17, 18), a direct comparison of all four members was not available. Using transient transfections in 293T cells, we observed that overexpression of these receptors is sufficient to induce production of the second messengers IP and cAMP at physiological pH. These findings are indicative of the constitutive, ligand-independent activities of these receptors and are consistent with previous observations (1, 10, 11, 14, 15, 17, 24). We also found that acidification of the extracellular environment significantly augments the constitutive activities of OGR1, GPR4, and TDAG8; therefore, providing confirmation of previous observations (17, 18). In contrast, an analysis of cells overexpressing huG2A detected a less significant increase in IP production after exposure to a range of acidic pH in comparison with the other members of the group. Mouse G2A, although constitutively active, was essentially insensitive to pH variations, as measured by the production of IP or cAMP.

We considered several scenarios that could explain the differential pH sensitivity of G2A relative to its homologs. We cannot exclude the possibility that the proton-sensing function of G2A depends on the cellular context. Although Murakami et al. (11) used PC12h and COS-7 cell lines to document pH-dependent effects of huG2A, these authors also mention the failure to detect such effects in NIH 3T3 cells. Significantly, our observations of pH-modulated IP production by muG2A, huG2A, and OGR1 in transfected 293T cells were accurately reproduced in RAT-1 fibroblastic cell lines stably transduced with these receptors and FACS sorted for equivalent GPCR levels.

Lowering the extracellular pH was proposed to trigger the activation of cell surface receptors by induction of conformational changes (25). These changes could result from the protonation of the imidizole group of histidine, the most common protein functional group with a pKa between pH 6 and 7 (25). The work of Ludwig et al. (17) by using a computational 3D model of OGR1 and site-directed mutagenesis has provided strong experimental support for the role of histidine residues in pH sensing. An analysis of the human and mouse G2A sequences (Fig. 3) reveals a striking absence of histidine residues at positions corresponding to those shown to be critical for pH-induced activation of OGR1 (17). Interestingly, two of these residues (OGR1 H20 and H169) are replaced by positively charged amino acids (arginine and lysine, respectively) in the G2A sequence. This finding raises the possibility that, at physiological pH, these residues could mimic the charge of the protonated histidines in OGR1 and constrain G2A into an active conformation (26).

Effects of Lysolipids on pH-Modulated Activities. One of the most complex features shared by the members of the G2A group relates to the biological effects of small lipid molecules, such as LPC, SPC, and psychosine PSY on cells expressing these GPCRs. Although some of the initial reports claiming a ligand relationship for these molecules and corresponding GPCRs have not been independently confirmed (5), have been contradicted by other studies (7, 24), or have been retracted (6), the effects of lysolipids on pH-dependent activation have been recently examined (11, 17, 18). A review of these studies reveals a complex pattern. Although Ludwig et al. (17) failed to detect any specific effects of SPC or LPC on OGR1 and GPR4, Murakami et al. (11) found an antagonistic role for LPC during pH-mediated activation of huG2A. The proposed ligand for TDAG8, PSY (16), was found by Wang et al. (18) to antagonize pH responses by TDAG8, GPR4, and OGR1. In this study, the addition of LPC, SPC, or PSY during exposure of GPCR-transfected cells to acidic environments resulted in minor and generally nonspecific effects (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). However, we have consistently observed an ≈25–35% inhibition of the IP production by huG2A-transfected 293T cells by LPC (Fig. 9). This inhibition was independent of the pH of the assay. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that these lipids exert weak antagonism specific for the members of the G2A group, another explanation should take into account possible nonspecific effects. These effects could involve lysophospholipid-induced modifications of the lipid bilayer, a process known to affect the function of different classes of membrane proteins, such as inward rectifier potassium channels, voltage-dependent sodium channels, and Na+, K+-ATPase (27). Further work is clearly required to better characterize the effects of lysophospholipids on the pH-dependent activation of the G2A group of GPCRs.

Proton Sensors in the Immune System. Extracellular acidosis is frequently associated with a variety of immunopathological situations. Inflammatory responses during infections (28), airway condensates from asthmatic patients (29), and microenvironments of many solid tumors (30) are all accompanied by pH values as low as 5.5–7.0. However, few studies have examined the effects of protons on the function of immune cells (31; reviewed in ref. 21).

Our results suggest that TDAG8 expression by immune cells is critically required for the production of cAMP after exposure to acidic extracellular pH. The functional consequences, if any, of this response are yet to be identified. In immune cells, elevation of intracellular cAMP, as a result of prostaglandin E and β-adrenergic stimuli or through the inhibition of members of the cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase superfamily, has the potential of evoking a range of antiinflammatory effects (reviewed in ref. 32). Despite the significant in vitro defect in the acidic pH-induced cAMP production by TDAG8 KO immune cells, a preliminary examination of TDAG8-deficient mice has not revealed any major abnormalities in the development of the immune system or in its major functions (C.G.R., A.N., J.M., R. Lim, and O.N.W., unpublished data). However, future experiments aimed at inducing local or systemic pH alterations in these mice may uncover immune phenotypes resulting from the loss of TDAG8-dependent responses to acidic pH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Takehiko Yokomizo for generously providing the protocol for the IP assay; Shirley Quan, Donghui Cheng, and Mireille Riedinger for outstanding technical assistance; James Johnson, LaKeisha Perkins, Mathew Au, and Rosalyn Taijeron for maintaining the mouse colony; and Barbara Anderson for excellent preparation of the manuscript. This work were supported in part by funds from the Plum Foundation. O.N.W. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. C.G.R. is supported by a Cancer Research Institute fellowship. A.N. was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Training Fellowship for Medical Students. L.W. is a Fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Abbreviations: DEX, dexamethasone; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; GPR4, G protein-coupled receptor 4; IBMX, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine; IP, inositol phosphate; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; OGR1, ovarian cancer G protein-coupled receptor 1; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PSY, psychosine; SPC, sphingosylphosphorylcholine; TDAG8, T cell death-associated gene 8; HEM, Hepes/4-(2-hydroxyethyl)1-piperazine-propanesulfonic acid/Mes.

References

- 1.Weng, Z., Fluckiger, A. C., Nisitani, S., Wahl, M. I., Le, L. Q., Hunter, C. A., Fernal, A. A., Le Beau, M. M. & Witte, O. N. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12334–12339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi, J. W., Lee, S. Y. & Choi, Y. (1996) Cell Immunol. 168, 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu, Y. & Casey, G. (1996) Genomics 35, 397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heiber, M., Docherty, J. M., Shah, G., Nguyen, T., Cheng, R., Heng, H. H., Marchese, A., Tsui, L. C., Shi, X., George, S. R., et al. (1995) DNA Cell Biol. 14, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu, Y., Zhu, K., Hong, G., Wu, W., Baudhuin, L. M., Xiao, Y. & Damron, D. S. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabarowski, J. H., Zhu, K., Le, L. Q., Witte, O. N. & Xu, Y. (2001) Science 293, 702–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu, K., Baudhuin, L. M., Hong, G., Williams, F. S., Cristina, K. L., Kabarowski, J. H., Witte, O. N. & Xu, Y. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41325–41335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radu, C. G., Yang, L. V., Riedinger, M., Au, M. & Witte, O. N. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang, L. V., Radu, C. G., Wang, L., Riedinger, M. & Witte, O. N. (September 21, 2004) Blood, 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1916.

- 10.Lin, P. & Ye, R. D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14379–14386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murakami, N., Yokomizo, T., Okuno, T. & Shimizu, T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 42484–42491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han, K. H., Hong, K. H., Ko, J., Rhee, K. S., Hong, M. K., Kim, J. J., Kim, Y. H. & Park, S. J. (2004) J. Leukocyte Biol. 76, 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan, J. J., Jung, J. S., Lee, J. E., Lee, J., Huh, S. O., Kim, H. S., Jung, K. C., Cho, J. Y., Nam, J. S., Suh, H. W., et al. (2004) Nat. Med. 10, 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabarowski, J. H., Feramisco, J. D., Le, L. Q., Gu, J. L., Luoh, S.-W., Simon, M. I. & Witte, O. N. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 12109–12114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zohn, I. E., Klinger, M., Karp, X., Kirk, H., Symons, M., Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M., Der, C. J. & Kay, R. J. (2000) Oncogene 19, 3866–3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Im, D. S., Heise, C. E., Nguyen, T., O'Dowd, B. F. & Lynch, K. R. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 153, 429–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludwig, M. G., Vanek, M., Guerini, D., Gasser, J. A., Jones, C. E., Junker, U., Hofstetter, H., Wolf, R. M. & Seuwen, K. (2003) Nature 425, 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, J. Q., Kon, J., Mogi, C., Tobo, M., Damirin, A., Sato, K., Komachi, M., Malchinkhuu, E., Murata, N., Kimura, T., et al. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45626–45633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawley, R. G., Hawley, T. S., Fong, A. Z., Quinto, C., Collins, M., Leonard, J. P. & Goldman, S. J. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 10297–10302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le, L. Q., Kabarowski, J. H., Weng, Z., Satterthwaite, A. B., Harvill, E. T., Jensen, E. R., Miller, J. F. & Witte, O. N. (2001) Immunity 14, 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lardner, A. (2001) J. Leukocyte Biol. 69, 522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tosa, N., Murakami, M., Jia, W. Y., Yokoyama, M., Masunaga, T., Iwabuchi, C., Inobe, M., Iwabuchi, K., Miyazaki, T., Onoe, K., et al. (2003) Int. Immunol. 15, 741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malone, M. H., Wang, Z. & Distelhorst, C. W. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52850–52859. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Bektas, M., Barak, L. S., Jolly, P. S., Liu, H., Lynch, K. R., Lacana, E., Suhr, K. B., Milstien, S. & Spiegel, S. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 12181–12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith, J. B., Dwyer, S. D. & Smith, L. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 8723–8728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kostenis, E. (2004) J. Cell Biochem. 92, 923–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lundbaek, J. A. & Andersen, O. S. (1994) J. Gen. Physiol. 104, 645–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmen, H. P. & Blaser, J. (1993) Am. J. Surg. 166, 24–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunt, J. F., Fang, K., Malik, R., Snyder, A., Malhotra, N., Platts-Mills, T. A. & Gaston, B. (2000) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 161, 694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evelhoch, J. L. (2001) Novartis Found Symp. 240, 68–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vermeulen, M., Giordano, M., Trevani, A. S., Sedlik, C., Gamberale, R., Fernandez-Calotti, P., Salamone, G., Raiden, S., Sanjurjo, J. & Geffner, J. R. (2004) J. Immunol. 172, 3196–3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Essayan, D. M. (2001) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 108, 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.