Abstract

Although prices for medical services are known to vary markedly between hospitals, it remains unknown whether variation in hospital prices is explained by differences in hospital quality or reimbursement from major insurers. We obtained “out-of-pocket” price estimates for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) from a random sample of US hospitals for a hypothetical patient without medical insurance. We compared hospital CABG price to (1) “fair price” estimate from Healthcare Bluebook data using each hospital’s zip code and (2) Society of Thoracic Surgeons composite CABG quality score and risk-adjusted mortality rate. Of 101 study hospitals, 53 (52.5%) were able to provide a complete price estimate for CABG. The mean price for CABG was $151,271 and ranged from $44,824 to $448,038. Except for geographic census region, which was weakly associated with price, hospital CABG price was not associated with other structural characteristics or CABG volume (p >0.10 for all). Likewise, there was no association between a hospital’s price for CABG with average reimbursement from major insurers within the same zip code (ρ = 0.07, p value = 0.6), Society of Thoracic Surgeon composite quality score (ρ = 0.08, p value = 0.71), or risk-adjusted CABG mortality (ρ = −0.03 p value = 0.89). In conclusion, the price of CABG varied more than 10-fold across US hospitals. There was no correlation between price information obtained from hospitals and the average reimbursement from major insurers in the same market. We also found no evidence to suggest that hospitals that charge higher prices provide better quality of care.

Health care in the United States (US) is costly and accounts for nearly 18% of the gross domestic product,1,2 As a result, health care expenses are a leading cause of financial stress in US households.1 Moreover, unlike other businesses where consumers choose services based on prices, the price of health care services in the US is usually not known until the services are received, making it difficult for patients to function as educated consumers. Furthermore, although major insurers negotiate discounted prices for their members, uninsured patients do not enjoy a similar protection. Therefore, increasing transparency in medical prices has gained significant traction in recent years as a measure to reduce costs by engaging patients in comparison shopping and encouraging competition between hospitals.3 Although previous studies have shown a 10-fold variation in price of health care services across US hospitals,2,4–8 it remains unknown whether hospitals that charge higher prices for uninsured patients also receive high reimbursement for insured patients or provide greater quality of care. Clarifying this relation will be of critical importance to patients who may be willing to pay a higher price for superior quality of care. To address this gap in knowledge, we contacted a sample of US hospitals by telephone to request hospital and physician prices for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) for a hypothetical patient without health insurance. We examined the association between a hospital’s price for CABG with (1) average hospital reimbursement from major insurers within the hospital’s zip code and (2) risk-adjusted mortality rate and composite quality score for CABG obtained from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database.

Methods

We used 4 main sources of data in our study: (1) Medicare part A data, 2010 to identify CABG hospitals; (2) American Hospital Association (AHA) data, 2010 for hospital structural characteristics; (3) Healthcare Bluebook data for average reimbursement for CABG in the hospital’s zip code of location (https://www.healthcarebluebook.com); and (4) STS data, 2013 for hospital risk-adjusted CABG mortality and composite quality score.

We used Medicare data to identify all US hospitals that performed at least 10 CABG surgeries on Medicare patients in 2010 (latest year of Medicare data available at our institution). From that list, we randomly selected 2 hospitals from each of the 50 US states and the District of Columbia. A total of 101 hospitals were identified (Vermont only had one hospital that met our CABG volume criteria) for participation in the study (Table 1). The list of 101 study hospitals is provided in the Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

US hospitals and study hospital population by characteristics

| Variables | All U.S. hospitals, N = 1141 | Study hospitals, N = 101 | p values |

|---|---|---|---|

| CABG volume | |||

| <50 | 293 (26%) | 19 (19%) | 0.35 |

| 50–99 | 334 (30%) | 33 (33%) | |

| 100–199 | 348 (30%) | 30 (30%) | |

| > 200 | 166 (15%) | 19 (19%) | |

| Geographic area | |||

| North Mid-Atlantic | 149 (13%) | 17 (17%) | |

| South Atlantic | 170 (15%) | 18 (18%) | |

| North Central | 305 (27%) | 24 (24%) | 0.43 |

| South Central | 266 (23%) | 16 (16%) | |

| Mountain-Pacific | 234 (21%) | 26 (26%) | |

| Teaching status | |||

| Yes | 229 (20%) | 31 (31%) | 0.014 |

| No | 903 (79%) | 70 (69%) | |

| Location | |||

| Urban | 1036 (91%) | 93 (92%) | 0.9 |

| Rural | 85 (7%) | 8 (8%) | |

| Ownership | |||

| Non-profit | 795 (70%) | 75 (74%) | 0.66 |

| For-profit | 219 (19%) | 16 (16%) | |

| Government | 118 (10%) | 10 (11%) | |

Bold value indicates statistically significance.

Based on previous work and method developed by our author group,5 we developed a standardized script to conduct telephone interviews to obtain price for CABG from our study hospitals (included in the Supplementary Material). We developed a hypothetical scenario in which the 62-year-old father of one of the study investigators (BDG) was advised to undergo CABG, and the caller was trying to obtain a price estimate for that procedure. Briefly, the caller’s father was a previously healthy man who developed angina over the past few months. He had undergone multiple testing and imaging procedures, had failed medical therapy, and had multiple evaluations from physicians, all of whom recommended CABG. The caller’s father did not have health insurance but would be willing to pay for the procedure “out-of-pocket.” Therefore, the caller was “shopping” for the best possible price for the surgery and would be comparing prices from different hospitals before choosing a hospital. Additional details regarding the medical history, results of the cardiac testing, social history, expected length of stay, postdischarge care, the Current Procedural Terminology and International Classification of Diseases–Ninth Clinical Modification codes were also included in the script. The study’s lead investigator (BDG) made all the telephone calls to study hospitals. During the telephone call, every effort was made to use the script as much as possible. Pilot testing of the script was completed on 4 hospitals that were not included in the study sample to assess for content, structure, and clarity; modifications and revisions were made as needed.

All telephone interviews were conducted during January 1, 2014, to February 11, 2014. The invesigator (BDG) called the main hospital telephone number for each hospital and requested to be connected to an office or a department that could provide a “cash” or “out-of-pocket” price estimate for a surgery. If the main hospital operator was unable to find the appropriate contact person or department, the caller requested to speak with either the financial department or the patient billing office. On being transferred to the appropriate department, the caller repeated her request to speak with someone who could provide a price estimate for a surgery. Once connected with someone who stated they could provide that information, the caller transitioned immediately to the script for the remainder of the interview. The caller requested an estimate for the bundled price (hospital and physicians fees). If the hospital was unable to provide a complete bundle price, information regarding affiliated cardiac surgery practices was obtained. If more than one cardiac surgery practice was affiliated with the hospital, each practice was contacted in alphabetical order until a price estimate was obtained. All prices were recorded in addition to information regarding the phone call process. When the caller was unable to speak directly with the appropriate person, a standard message with the reason for the phone call and a callback telephone number was left. If a hospital declined to provide a price estimate, the reason for this was recorded. Every hospital was contacted a maximum of 3 times. If the caller was unable to obtain a price estimate after 3 separate attempts that hospital was deemed as unable to provide an estimate.

Our primary outcome was the complete price for CABG obtained as a bundled price or after summing the individual hospital and physician price. We used the AHA data, 2010 to obtain information regarding each hospital’s structural characteristics—geographic census region (North Mid-Atlantic, South Atlantic, North Central, South Central, and Mountain Pacific), teaching status, location (urban vs rural), and ownership structure (nonprofit, for-profit, and government). In addition, for each hospital that was able to provide a compete bundle price, we also obtained data regarding average reimbursement price for CABG within the zip code of the hospital location using the Healthcare Bluebook website.

Finally, we obtained data regarding hospital quality from the STS website. Briefly, the STS database collects data on 11 quality measures that are endorsed by the National Quality Forum and are reported under the following 4 domains: (1) perioperative medical care, (2) operative care, (3) avoidance of risk-adjusted mortality, and (4) avoidance of risk-adjusted major morbidity. Performance in individual domains is combined to yield a composite STS CABG quality score for each hospital. For this study, we obtained the risk-adjusted mortality and the overall CABG composite score from the STS website for hospitals that provide a price estimate. Additional details regarding the quality measures from the STS database are described in detail elsewhere.9–11

First, we compared characteristics of our study hospitals with all hospitals that met our study inclusion criteria (i.e., performed CABG on at least 10 Medicare patients during the year 2010). Second, we compared characteristics of hospitals that were and were not able to provide a complete price (either bundled or separate) using the chi-square test or unpaired t test when appropriate. Third, we examined hospital variation in price for CABG between hospitals using graphical methods and examined the association between hospital price, structural characteristics (geographic census region, teaching status, urban/rural location, and ownership status), and Medicare 2010 CABG volume. We also examined the correlation between a hospital’s quoted price for CABG with (1) average reimbursement for CABG obtained from the Healthcare Bluebook; (2) hospital’s overall STS CABG quality composite score; and (3) STS risk-adjusted mortality rate using Pearson’s correlation.

All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina) and Microsoft Excel (version 14.4). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa, whom waived the requirement for informed consent, approved the study.

Results

A total of 101 hospitals were included in our study. A comparison between our study hospitals and all US hospitals (n = 1,141) that performed CABG in Medicare patients during 2010 is provided in Table 1. As can be seen from the table, hospitals included in our study were generally similar to US. CABG hospitals except a higher prevalence of teaching hospitals were in our study population (31% vs 20%).

Of the 101 hospitals in our study, only 9 hospitals (8.9%) were able to provide a complete bundled price (combined physician and hospital price) for CABG. Complete price was obtained from an additional 44 hospitals (43.6%) after calling the hospital and physician offices separately, resulting in a total of 53 hospitals (52.5%) that were able to provide a price for CABG.

Hospitals that were able to provide a price for CABG were more likely to be located in the North Central census region (p value <0.01) and in rural locations compared to hospitals that were not able to provide a complete price (Table 2). However, there was no difference between hospitals that were and were not able to provide a price for CABG with regards to the Medicare CABG volume, teaching status, and ownership status (Table 2). Data regarding STS quality measures for CABG were available from only 23 hospitals (50.9%) that were able to provide a price for CABG, and 16 (33%) that were not able to provide a price for CABG. Overall, the mean STS composite score for these hospitals was 96.4 (SD 1.14, range 94.1 to 98), and mean risk-adjusted CABG mortality rate was 2.1% (SD 0.33, range 1.6 to 2.9), and did not differ between hospitals that were and were not able to provide a CABG price.

Table 2.

Characteristics of hospitals that were and were not able to provide a price estimate for coronary artery bypass grafting

| Variable | Hospitals

|

* p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All hospitals, N=101 | Hospitals able to provide a price, N=53 | Hospitals unable to provide a price, N=48 | ||

| CABG volume | ||||

| < 50 | 24 (24%) | 12 (23%) | 12 (25%) | 0.87 |

| 50–99 | 34 (34%) | 16 (30%) | 18 (38%) | |

| 100–199 | 28 (28%) | 17 (32%) | 11 (23%) | |

| > 200 | 15 (15%) | 8 (15.%) | 7 (15%) | |

| Geographic Region | ||||

| North Mid-Atlantic | 17 (17%) | 6 (11%) | 11 (23%) | <0.01 |

| South Atlantic | 18 (18%) | 9 (17%) | 9 (19%) | |

| North Central | 15 (15%) | 14 (26%) | 1 (2%) | |

| South Central | 25 (25%) | 6 (11%) | 19 (40%) | |

| Mountain-Pacific | 26 (26%) | 18 (34%) | 8 (17%) | |

| Teaching Status | ||||

| Yes | 29 (29%) | 14 (26%) | 15 (31%) | 0.6 |

| No | 72 (71%) | 39 (74%) | 33 (69%) | |

| Location | ||||

| Urban | 82 (81%) | 39 (74%) | 43 (90%) | 0.04 |

| Rural | 19 (19%) | 14 (26%) | 5 (10%) | |

| Ownership | ||||

| Non-profit | 73 (72%) | 41 (77%) | 32 (67%) | 0.4 |

| For-profit | 16 (16%) | 6 (11%) | 10 (21%) | |

| Government | 12 (12%) | 6 (11%) | 6 (13%) | |

| STS Scores availability | N = 39 | N = 23 | N = 16 | |

| Mortality scores | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0.53 |

| Composite scores | 96.4 | 96.6 | 96.2 | 0.34 |

p Values compare hospitals that provided a price for CABG with hospitals that were unable to provide a price.

Bold value indicates statistically significance.

Among the 53 hospitals that were able to provide a price estimate, the mean complete price for CABG (physician and hospital) was $151,271 (SD 71,917). Mean price for CABG was similar between hospitals that provided a bundled price compared with hospitals that provided a hospital and physician price separately ($167,513 vs $147,949, p value = 0.47). However, there was a 10-fold variation in price for CABG across our study hospitals (range: $44,824 to $448,038; Figure 1). In contrast, the average reimbursement for CABG obtained from Healthcare Bluebook for patients residing in the same zip code as the study hospitals showed much less variation and ranged from $35,304 to $54,166 (Figure 1). Moreover, the prices obtained from the Healthcare Bluebook were 20% to 90% lower than the prices provided by hospitals. There was no correlation between the price of CABG obtained from hospitals and the average reimbursement price obtained from Healthcare Bluebook (ρ = 0.07, p value = 0.6).

Figure 1.

Distribution of price estimate of CABG provided by hospitals and average reimbursement price obtained from Healthcare Bluebook.

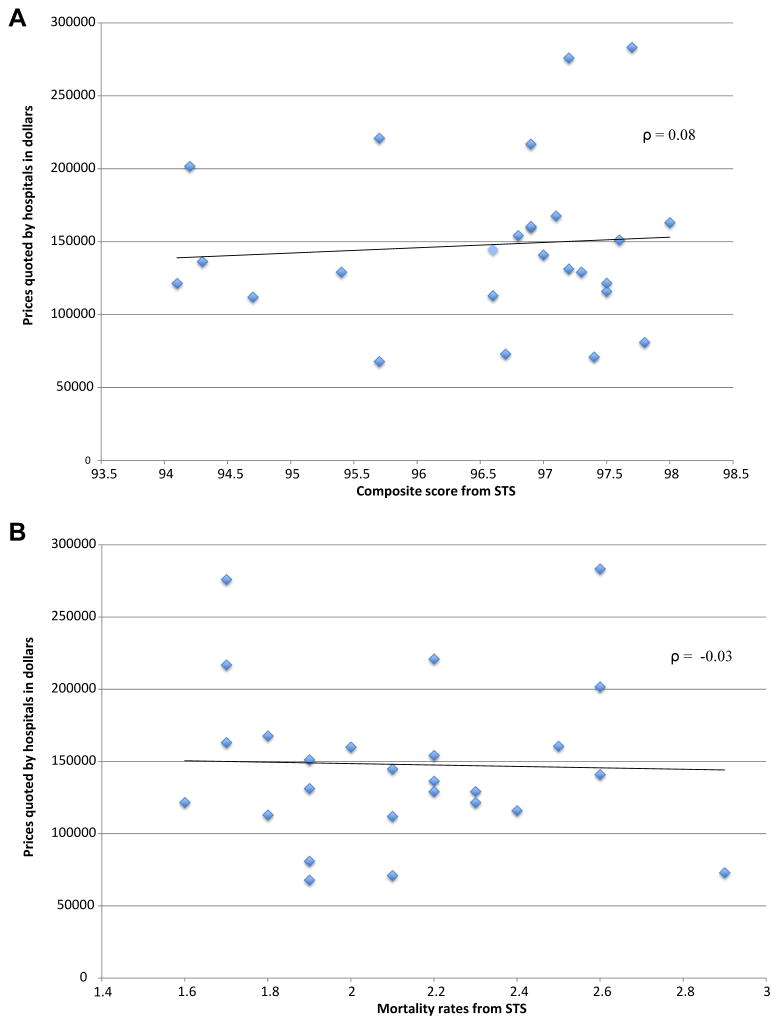

Table 3 lists the association between a hospital’s quoted CABG price with its structural characteristics. There was a weak association between geographic location and hospital CABG price. Mean price of CABG was lowest at hospitals located in the South Central area and highest at hospitals located in the Mountain Pacific area ($104,045 vs $187,501; p value = 0.04, Table 3). Other hospital characteristics such as Medicare CABG volume, teaching status, location, and ownership status were not significantly associated with hospital CABG price (Table 3). Importantly, we found no association between the price of CABG provided by hospitals with their STS composite quality score (ρ = 0.08, p value = 0.71) and their risk-adjusted CABG mortality rate (ρ = −0.03, p value = 0.89; Figure 2).

Table 3.

Association between hospital characteristics and price estimate for CABG

| Price, Mean (SD) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| All hospitals | 151,271 (71917) | |

| CABG volume | ||

| < 50 | 181,628 (107432) | 0.17 |

| 50–99 | 167,288 (62699) | |

| 100–149 | 132,820 (34356) | |

| 150–199 | 102,872 (37255) | |

| > 200 | 131,629 (46865) | |

| Geographic Region, | ||

| North Mid-Atlantic | 141,285 (32420) | 0.04 |

| South Atlantic | 116,051 (34548) | |

| North Central | 154,163 (60231) | |

| South Central | 98,652 (36508) | |

| Mountain-Pacific | 187,501 (90113) | |

| Teaching Status | ||

| Yes | 135,741 (57008) | 0.36 |

| No | 156,847 (75792) | |

| Location | ||

| Urban | 156,004 (77551) | 0.43 |

| Rural | 138,088 (50895) | |

| Ownership | ||

| Non-profit | 148,075 (69326) | 0.24 |

| For-profit | 196,937 (75872) | |

| Government | 130,238 (72304) | |

Bold value indicates statistically significance.

Figure 2.

(A) Correlation between the price of CABG provided by hospitals with STS composite score; (B) correlation between the price of CABG provided by hospitals and STS risk-adjusted CABG mortality rate.

Discussion

Despite increasing emphasis on health care transparency in recent years, we found that obtaining price information for CABG remains difficult. We also found a marked (10-fold) variation in hospital prices for CABG in the United States. Moreover, the price information that we received from hospitals was often 400% to 500% higher than the suggested fair price in that hospital’s market. Most importantly, we found no evidence to suggest that hospitals that charge higher prices also provide better quality of care or achieve superior outcomes. A number of our findings are important and merit further consideration.

Currently, 35 states require that hospitals make information regarding prices available to patients12 with more aggressive legislation regarding out-of-pocket costs being considered.12–14 Many individual health plans have also developed tools to estimate out-of-pocket costs to guide consumers’ choice of providers.13 Despite these efforts, obtaining price for CABG remains difficult and time-consuming. In this study, we were able to obtain a complete price from only 53 (52.5%) of our study hospitals. It required multiple telephone calls, speaking with different people across various hospital departments, and frequently multiple explanations as to why we were seeking this information. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have also suggested a similar difficulty in obtaining price information regarding common procedures.5,8 These findings suggest that efforts at improving price transparency need to be reenergized.

We also found that price for CABG varied nearly 10-fold in our study and ranged from $44,824 to $448,039. The reasons for such marked variation in prices are likely multifactorial. Although we used a standardized script to obtain hospital prices, it is likely that hospitals differed in the approach that they used to provide a price estimate. Some hospitals may have provided the direct “charge master” price where as others may have provided a discounted price, and still, others may have provided the average Medicare reimbursement price. However, regardless of the cause, a 10-fold variation in prices for CABG is significant and underscores the importance of increasing price transparency in health care as a means to lower overall price through market-based competition. Although the number of uninsured Americans has decreased significantly with the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, the number of patients with higher cost sharing through high-deductible health plans and reference pricing is likely to grow,2,4,6,15 requiring patients to bear greater financial responsibility with respect to their health care cost.

The evidence regarding the effectiveness of increasing price transparency to lower costs is encouraging. In a recent study, reference pricing (programs that provide the consumer with agreed on reimbursement rates for specific procedures, leaving any difference to be paid by the consumer) for knee and hip replacement surgery was implemented within the California Public Employees’ Retirement System.15 This initiative led to significant cost savings for both California Public Employees’ Retirement System and out-of-pocket costs for the members ($2.8 million and $0.3 million, respectively), an increase in volume at the low-priced hospitals, a decrease in volume at the high-priced hospitals, and most importantly, a decrease in hospital prices at both high-price and low-price hospitals. Although another study did not observe any decrease in overall health care costs after implementing transparency legislature,16 additional studies are needed to fully examine the impact of making health care prices more transparent on overall cost, quality of care, and patient outcomes.

Perhaps, the most important finding of our study is that it dispels a commonly held belief that a higher price tag is associated with superior quality of care. We found no association between the quoted hospital price for CABG, its STS composite quality score, or its risk-adjusted mortality rate. Moreover, there was no evidence that hospitals that charge a higher price from uninsured patients also receive a similarly higher reimbursement from major insurers for insured patients. Based on our findings, patients should feel reassured that engaging in comparison shopping is unlikely to lead them to hospitals or providers with worse outcomes or poorer quality of care. In fact, with data on hospital quality (i.e., Hospital Compare) and health care prices (i.e., Healthcare Bluebook) becoming increasingly available, patients may have a unique opportunity to choose low-cost, high-quality hospitals. Policy experts have suggested that increasing transparency in health care prices coupled with improvement in cost and outcome measurement and reimbursement that is value-based rather than fee-based has the potential to reduce costs without compromising quality and ultimately benefiting consumers.17

Our study findings should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, although study hospitals were contacted for CABG price information in 2014, the list of CABG hospitals and their structural characteristics were obtained using 2010 Medicare and AHA data as these were the latest years of data available at our institution. This may have led to exclusion of some hospitals that had established new cardiac surgery programs from 2010 to 2014 and an inclusion of hospitals that no longer offered cardiac surgery in 2014. It is possible that the response rate for hospital prices would have been higher if we had used more current Medicare data. However, given that the response rate in our study is consistent with other studies that have used a similar approach,2,4–8 it is unlikely that this affected our results in a substantial manner. Second, it is possible that we lacked statistical power in our analyses of the association between hospital price and hospital structural characteristics because of our limited sample size. Third, we were able to obtain STS data on risk-adjusted mortality rate and composite quality score from only 23 hospitals (43%) that provided a price estimate. Although we found no signal for an association between hospital price and hospital quality, it is possible that the association between hospital price and quality measures may have been different if all hospitals had data available. Fourth, STS CABG quality scores, including 30-day mortality, may be limited as quality measures because of potential underreporting and inability to capture events beyond 30 days, which may still be related to the surgery. Fifth, our study focused on only CABG; and therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other procedures or diagnoses. Sixth, although we used a standardized script to obtain price estimates from study hospitals, it is possible that different hospitals may process the clinical information we provided differently or may have modified the price after a formal review of the clinical case (i.e., review of coronary angiography films and so on). Moreover, although the caller made every effort to use the standardized script when connected with the person who was able to provide pricing information, deviations from the script were inevitable and may have influenced hospital price estimates. Finally, our study focuses on only CABG; and therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other procedures or diagnoses.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.01.004.

References

- 1.Brill S. Bitter pill: how outrageous pricing and egregious profits are destroying our health care. Time. 2013;181:16–24. 26. 28 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthal E. The $2.7 Trillion Medical Bill. New York, New York: The New York Times; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinaiko AD, Rosenthal MB. Increased price transparency in health care–challenges and potential effects. New Engl J Med. 2011;364:891–894. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1100041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millman J. Price transparency stinks in health care. Here’s how the industry wants to change that. [Accessed September 10, 2014];Wonkblog. 2014 Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs.

- 5.Rosenthal JA, Lu X, Cram P. Availability of consumer prices from US hospitals for a common surgical procedure. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:427–432. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinhardt UE. The disruptive innovation of price transparency in health care. JAMA. 2013;310:1927–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stockwell Farrell K, Finocchio L, Trivedi A, Mehrotra A. Does price transparency legislation allow the uninsured to shop for care? J Gen Intern Med. 2009;25:110–114. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1176-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein JR, Bernstein J. Availability of consumer prices from Philadelphia area hospitals for common services: electrocardiograms vs parking. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:292–293. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shahian DM, Edwards FH, Ferraris VA, Haan CK, Rich JB, Normand SL, DeLong ER, O’Brien SM, Shewan CM, Dokholyan RS, Peterson ED Society of Thoracic Surgeons Quality Measurement Task Force. Quality measurement in adult cardiac surgery: part 1–Conceptual framework and measure selection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:S3–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shroyer AL, Coombs LP, Peterson ED, Eiken MC, DeLong ER, Chen A, Ferguson TB, Jr, Grover FL, Edwards FH Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons: 30-day operative mortality and morbidity risk models. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1856–1864. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00179-6. discussion 1864–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien SM, Shahian DM, DeLong ER, Normand SL, Edwards FH, Ferraris VA, Haan CK, Rich JB, Shewan CM, Dokholyan RS, Anderson RP, Peterson ED. Quality measurement in adult cardiac surgery: part 2–Statistical considerations in composite measure scoring and provider rating. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:S13–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Hospital Association. TrendWatch Price Transparency Efforts Accelerate: What Hospitals and Other Stakeholders Are Doing to Support Consumers. Chicago, Illinois: Americal Hospital Association; 2014. [Accessed September 8, 2014]. Available at: http://www.aha.org. [Google Scholar]

- 13.iHealthBeat. Bill Aims to Boost Transparency of Health Care Cost Information HR1326-Health Care Price Transparency Promotion Act of 2013. Oakland, California: The Advisory Board Company for the California Healthcare Foundation; 2013. [Accessed October 9, 2014]. Available at: www.ihealthbeat.org. [Google Scholar]

- 14.APCD Council. [Accessed September 23, 2014];Interactive State Report Map. 2014 Available at: www.apcecouncil.org.

- 15.Robinson JC, Brown TT. Increases in consumer cost sharing redirect patient volumes and reduce hospital prices for orthopedic surgery. Health Aff. 2013;32:1392–1397. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tu HT, Lauer JR. Impact of health care price transparency on price variation: the New Hampshire experience. Issue brief. 2009:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan R, Porter M. The big idea: how to solve the cost crisis in health care. Harv Business Rev. 2011;89:46–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.