Abstract

The importance of genetic susceptibility in determining the progression of demyelination and neurologic deficits is a major focus in neuroscience. We studied the influence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ polymorphisms on disease course and neurologic impairment in virus-induced demyelination. HLA-DQ6 or DQ8 was inserted as a transgene into mice lacking endogenous expression of MHC class I (β2m) and class II (H2-Aβ) molecules. Following Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection, we assessed survival, virus persistence, demyelination, and clinical disease. Mice lacking expression of endogenous class I and class II molecules (β2m°Aβ°mice) died 3 to 4 weeks postinfection (p.i.) due to overwhelming virus replication in neurons. β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice had increased survival and decreased gray matter disease and virus replication compared to nontransgenic littermate controls. Both β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice developed chronic virus persistence in glial cells of the white matter of the spinal cord, with greater numbers of virus antigen-positive cells in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 than in β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice. At day 45 p.i., the demyelinating lesions in the spinal cord of β2m°Aβ°DQ8 were larger than those in the β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice. Earlier and more profound neurologic deficits were observed in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice, although by 120 days p.i. both strains of mice showed similar extent of demyelination and neurologic deficits. Delayed-type hypersensitivity and antibody responses to TMEV demonstrated that the mice mounted class II-mediated cellular and humoral immune responses. The results are consistent with the hypothesis that rates of progression of demyelination and neurologic deficits are related to the differential ability of DQ6 and DQ8 transgenes to modulate the immune response and control virus.

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiologic studies have correlated HLA class II alleles with susceptibility or resistance to certain immune-mediated diseases (Black et al., 1992; Zanelli et al., 1996). In some cases the presence of a particular HLA allele appears to modulate the immune response to certain exogenous antigens and protects the host from illness, whereas in other cases the host may mount an immune response against self-antigens. Similar associations have been reported in diseases with neurologic involvement, including Behcet’s disease (Alpsoy et al., 1998), narcolepsy (Kadotani et al., 1998; Aldrich, 1998), myasthenia gravis (Tola et al., 1994), Lyme neuroborreliosis (Halperin et al., 1991), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Kott et al., 1979). Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain these associations. Certain class II polymorphisms may be more prone to positively select either protective or autoreactive T cells than others (thymic selection). The second hypothesis states that some HLA molecules (such as HLA-DR, -DP, or -DQ) bind peptides derived from a pathogen, which results in widespread activation of T cells that cross-react with self-peptides (molecular mimicry) (Oldstone, 1998). The third hypothesis postulates that over time the immune response directed against an initial antigenic challenge (i.e., a virus) results in the recognition of new epitopes (epitope spreading) that results in tissue damage (Tuohy et al., 1998). None of the hypotheses has been convincingly proven in human autoimmune disease. Furthermore, whether DR, DP, and DQ contribute individually or in concert to protection versus immune-mediated neurologic injury following exogenous antigen challenge is unknown.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is characterized by central nervous system (CNS) demyelinating lesions containing B cells, T cells, and macrophages (Prineas and Wright, 1978). Attempts to correlate susceptibility and/or resistance to demyelination with particular class II alleles have yielded mixed results. Other factors, including ethnicity and environment, also appear important to the development of disease. The temporal development of disability between MS patients varies greatly. Recently, investigators have focused on the hypothesis that particular MHC class II alleles are indicators of clinical progression and neurologic deficits in MS (Weinshenker et al., 1998). These associations have become more powerful when the specific subtype of MS is also considered. Primary progressive MS has been associated with the HLA DR4/DQ8 and DR7/DQ9 extended haplotypes (Olerup et al., 1989). Associations with the DR2/DQ6 haplotype and primary progressive and relapsing remitting MS have also been made (Olerup et al., 1989; Duquette et al., 1985). Because certain HLA-DR and -DQ genes exist in linkage disequilibrium, it is difficult to discern whether the observed phenotype is the result of independent or interdependent effects of the class II genes. Limited study populations further confound these associations because of variability in forms of the disease and the potential for large numbers of genotypes.

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection of susceptible mouse strains provides investigators with a reproducible model of virus-induced demy- elination. During the first week following infection, virus replicates rapidly in CNS neurons, resulting in acute encephalitis (Dal Canto and Lipton, 1982). Susceptible animals that survive the acute phase clear virus from the neurons and develop chronic, progressive immune-mediated demyelinating disease (Dal Canto and Lipton, 1982) with virus persistence in the oligodendrocytes (Rodriguez et al., 1983; Aubert et al., 1987), microglia/macrophages (Clatch et al., 1990; Lipton, 1975; Dal Canto and Lipton, 1982), and astrocytes (Aubert et al., 1987). This model has also been used to study the subsequent neurologic deficits in chronically infected mice (Rivera-Quinones et al., 1998). Resistant mice infected with TMEV experience acute encephalitis and clear the virus, and no further pathology or clinical deficits result.

In a previous study we demonstrated that expression of HLA-DR3 in transgenic mice reduced the severity of TMEV-induced demyelination (Drescher et al., 1998). To understand the role of HLA-DQ polymorphisms in de- myelination and neurologic deficits, in this study we generated mice lacking expression of murine class I and class II molecules that were reconstituted with a single human class II DQ gene and examined the role of HLA-DQ polymorphisms in the TMEV model of MS. We first assessed the contribution of these genes to protection from neuronal disease and then investigated subsequent development of demyelination and progressive neurologic deficits. The data presented indicate that DQ6 and DQ8 each contribute uniquely to controlling virus-induced pathogenesis, supporting the hypothesis that demyelination and neurologic deficits are related to the ability of the human class II genes to modulate the immune response and control virus replication.

RESULTS

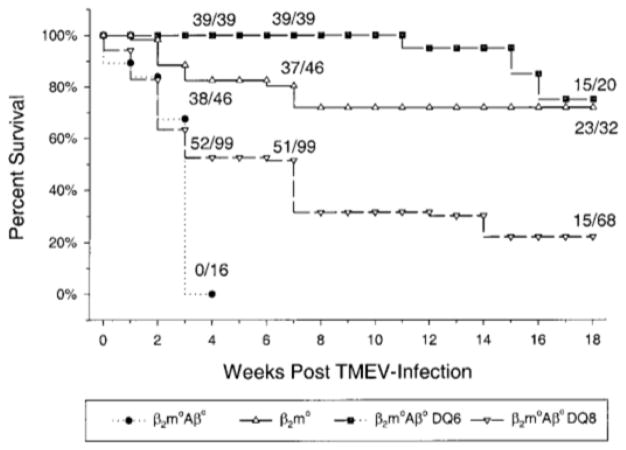

Expression of Human Class II (DQ6 or DQ8) Genes Protects Aβ°β2m° Mice from Death Following TMEV Infection

Previous studies have shown that mice with severe immune deficits [i.e., mice deficient in both class I and class II (β2°Aβ° mice)] are highly susceptible to death during the acute phase of the disease, presumably as a result of overwhelming viral replication in neurons, and die by day 24 postinfection (p.i.) (Drescher et al., 1999). Initially, mice expressing human class II genes (DQ6 or DQ8) were generated by inserting these genes into H-2b-mice lacking endogenous class II (Aβ°) expression but with preserved mouse class I. The level of expression of DQ6 and DQ8 molecules was similar on lymphocytes, splenocytes, and thymocytes (see Experimental Methods). Aβ°DQ6 (n = 16) and Aβ°DQ8 (n = 14) mice survived the acute phase of the disease, and all survived through 7 weeks postinfection, showing minimal pathology and no neurologic deficits. As these mice also expressed mouse class I and efficiently controlled virus replication, we tested whether the observed survival was related solely to the mouse class I gene by generating mice expressing the human transgene in the absence of both endogenous class I and class II. The mice further enabled us to study the effects of the respective HLA-DQ polymorphism on demyelinating disease without the influence of endogenous mouse MHC molecules. It has previously been reported that class I-deficient mice on a resistant background become susceptible to TMEV-induced demyelinating disease (Rodriguez et al., 1993). β2m°Aβ°DQ8 or β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice had significantly increased survival compared to infected nontransgenic β2m°Aβ° mice. Approximately 50% of β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (51/99) and 100% of β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice (39/39) survived to 7 weeks p.i. (Fig. 1). The β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice had a significant survival advantage over the β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice as 75% of the β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice survived to 18 weeks postinfection, whereas only 22% of the β2m°Aβ°DQ8 survived to the same time point. Interestingly, the survival advantage observed in β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice was comparable to that observed in β2m° mice (72%) expressing endogenous mouse class II. These data demonstrate that the expression of a human DQ gene in the absence of endogenous mouse class I and class II MHC can function in this model to prevent early death.

FIG. 1.

Survival of HLA transgenic mice following intracerebral infection with TMEV. Mice that do not express endogenous mouse class I and class II (β2m°Aβ°) died by 3 to 4 weeks p.i. Expression of a human class II transgene (DQ6 or DQ8) in β2m°Aβ°mice resulted in significant increase in survival at 3 weeks p.i. (χ2, P < 0.001). In addition, β2m°Aβ°DQ6 transgenic mice had enhanced survival over β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (χ2, P < 0.001) and β2m° mice (χ2, P < 0.018) during the acute phase (3 weeks)of the disease. Also at this time point, β2m° mice had enhanced survival over β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (χ2, P < 0.001). During the late chronic phase (18 weeks) of disease, β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m° mice had enhanced survival over β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (χ2, P < 0.001). All Aβ°DQ6 (n = 16) and Aβ°DQ8 (n = 14) mice survived through 7 weeks postinfection (data not shown).

DQ Antigens Are Expressed in Gray and White Matter of β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 Transgenic Mice

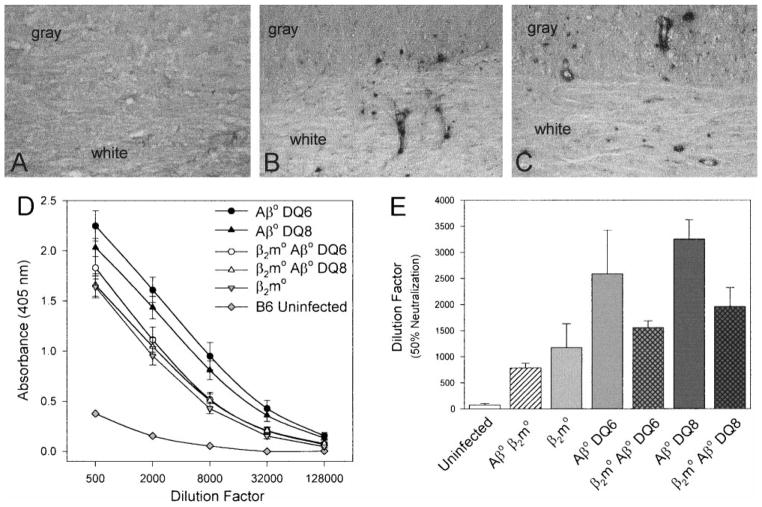

Normal CNS tissue does not express MHC class II. Previous work from our laboratory has demonstrated that following infection with TMEV, endogenous mouse MHC class II is upregulated on CNS resident cells (Rodriguez et al., 1987). To test whether the human DQ genes were expressed in the spinal cord following TMEV infection, immunostaining with an antibody that recognized both DQ6 and DQ8 was performed at day 21 p.i., a time when there is early development of inflammation and demyelination in the spinal cord. DQ-positive cells were readily detected in both the gray and the white matter of the β2m°Aβ°DQ6 (Fig. 2B)and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (Fig. 2C) mice. Staining was seen primarily in cells morphologically identified as perivascular inflammatory cells, macrophages and microglia. No staining was observed in uninfected mice (data not shown) or infected nontransgenic littermate control mice (Fig. 2A), demonstrating that the antibody did not cross-react with endogenous murine proteins. These observations demonstrate that human class II genes are expressed in the spinal cords of TMEV-infected mice.

FIG. 2.

β2m°Aβ° mice expressing HLA-DQ6 or DQ8 have functional in vivo immune responses. Shown are immunostaining for DQ antigen in spinal cords from infected mice (A, B, C) and TMEV-specific humoral immune responses (D, E). (A) At day 21 p.i. β2m°Aβ° mice were negative for expression of DQ antigen in both the gray and the white matter as determined by the avidin–biotin immunoperoxidase technique. Positive DQ staining was observed in both the spinal cord gray and white matter of TMEV-infected (B) β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and (C) β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice. The dark immunoreaction product indicates DQ-positive cells. Immunoreactivity was primarily observed in perivascular inflammatory cells and parenchymal cells, consistent morphologically with macrophages or microglial cells. (Original magnification for A, B, and C was 220×.) (D) At day 45 p.i., Aβ°DQ6, Aβ°DQ8, β2m°Aβ°DQ6, and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice mounted strong TMEV-specific IgG responses in the serum compared to uninfected C57BL/6 and β2m° mice. TMEV-specific IgG levels were measured by ELISA using purified TMEV as the antigen. Absorbances were read at 405 nm and plotted against the serum dilution factor. All samples were assayed in triplicate and the data are expressed as the means ± SEM. (E) The highest level of neutralizing antibody titers were observed in Aβ°DQ6 and Aβ°DQ8 mice at 45 days p.i. Lower levels of virus-neutralizing antibody were detected in β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice at day 45 p.i. No difference was observed in neutralizing antibody titers between β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice. Virus-specific neutralizing antibody titers were determined by co-incubating sera from TMEV-infected mice with infectious virus and then assaying for infectivity of L2 cells by plaque assay. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM dilutions that reduced the number of plaques by 50%.

Humoral Immune Responses and Delayed-Type Hypersensitivity (DTH) Responses Directed against Virus Antigens Are Mounted in TMEV-Infected Mice Expressing HLA-DQ6 and HLA-DQ8

Studies have demonstrated that immunoglobulins may play a role in modulating the pathogenesis of TMEV infection (Lipton et al., 1995; Cash et al., 1989; Rodriguez et al., 1988; Drescher et al., 1999). To test whether mice expressing human DQ genes mount a humoral response to a murine virus, TMEV-specific IgM and IgG were measured by ELISA to purified virus antigen at days 21 and 45 p.i. All groups of infected mice (β2m°Aβ°, AβDQ6, Aβ°DQ8, β2m°Aβ°DQ6, β2m°Aβ°DQ8) developed high-titered IgM responses to TMEV at 21 days p.i. compared to C57BL/6J uninfected mice (data not shown). Aβ°DQ6, Aβ°DQ8. β2m°Aβ°DQ6, and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice also had similar levels of TMEV-specific IgG at 45 day p.i. (Fig. 2D), which was increased compared to uninfected C57BL/6J mice. These levels were not significantly different from those detected in TMEV-infected C57BL/6 × 129 β2m° mice that express endogenous mouse class II genes. To test whether DQ polymorphisms influenced the level of TMEV-specific neutralizing antibody production, we performed a virus-neutralization assay using sera from mice at day 45 p.i. Comparable levels of neutralizing antibody were detected in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice (Fig. 2E) and were significantly higher than those in uninfected C57BL/6J mice (P < 0.05). The levels of neutralizing antibody in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice were similar to those in β2m° mice. Higher TMEV-neutralizing antibody titers were observed in Aβ°DQ8 mice compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice (P < 0.03), consistent with the fact that β2m is required for normal homeostasis of antibody in serum by influencing the rate of catabolism (Isreal et al., 1996). These results indicate that the human class II gene (DQ) in the absence of endogenous mouse class I MHC can function to generate high-titered neutralizing antibody directed against TMEV, and the levels of antibody generated were comparable to those in β2m° mice expressing endogenous mouse class II.

Previous studies have correlated DTH responses to TMEV in infected animals with the level of demyelination (Clatch et al., 1985). These studies suggest that the DTH response may be involved in the pathology observed in susceptible strains of mice. To assess the ability of mice expressing human class II transgenes to mount a class II-mediated CD4+ T cell response and to determine if an elevated DTH response was associated with increased pathology, DTH responses to purified TMEV were measured at day 47 postinfection. This time point was chosen because β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice showed significant differences in demyelination (Table 1). At day 47 postinfection, β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (n = 7) mice had significantly higher DTH responses to virus antigen at 48 h postchallenge (10.1 ± 1.6 increase in ear swelling) compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ6 (n = 8; 4.4 ± 0.7 mm−2; P = 0.002), β2m° (n = 7; 5.0 ± 1.0 mm−2; P = 0.021). The DTH responses of β2m° mice expressing endogenous murine class II and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice were not significantly different from those of mice used as negative controls: uninfected C57BL/6 × 129 (n = 9; 3.6 ± 0.5 mm−2; P > 0.05) or uninfected β2m° (n = 9; 2.8 ± 0.4 mm−2; P > 0.05) mice. Therefore, the insertion of a human class II molecule into β2m°Aβ° mice allows the animals to mount a CD4 T-cell-dependent immune response to TMEV.

TABLE 1.

Spinal Cord Pathology in Human Class II Transgenic Mice

| Strain | HLA | No. of mice | Days p.i. | Percentage of quadrants with disease (mean ± SEM)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray matter inflammation | Meningealinflammation | Demyelination | ||||||||||

| β2m° | — | 10 | 24 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 3.0 ± 0.7 |

|

3.7 ± 0..7 |

|

||||

| β2m°Aβ° | — | 8 | 21 | 21.6 ± 3.8 |

|

|

4.9 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | ||||

| β2m°Aβ° | DQ6 | 9 | 21 | 5.2 ± 1.5 | 16.9 ± 4.7 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | ||||||

| β2m°Aβ° | DQ8 | 7 | 23 | 7.2 ± 3.1 | 11.0 ± 3.2 | 4.2 ± 1.7 | ||||||

| β2m° | — | 8 | 45 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 9.4 ± 3.5 |

|

11.0 ± 2.7 |

|

||||

| β2m°Aβ° | DQ6 | 13 | 45 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 12.9 ± 1.9 |

|

12.5 ± 2.2 |

|

||||

| β2m°Aβ° | DQ8 | 16 | 45 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 20.2 ± 2.5 | 31.7 ± 3.5 | ||||||

| β2m° | — | 6 | 120 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 15.9 ± 2.4 |

|

|

35.9 ± 3.7 |

|

|

||

| β2m°Aβ° | DQ6 | 12 | 120–129 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 39.1 ± 2.8 | 58.7 ± 3.1 | ||||||

| β2m°Aβ° | DQ8 | 13 | 118–120 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 35.9 ± 3.9 | 62.6 ± 3.8 | ||||||

Note. For each mouse, 10 to 15 spinal cord sections were graded for gray matter inflammation, meningeal inflammation, and demyelination. The data are expressed as the percentage of spinal cord quadrants with disease (mean ± SEM).

Statistically significant by one-way ANOVA on ranks (P < 0.05).

Statistically significant by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

HLA-DQ6 and HLA-DQ8 Protect β2m°Aβ° Mice from a Lethal Neuronal Infection during the Acute Phase of the Disease

Previous work has demonstrated that severe-combined immunodeficiency (Scid) mice and recombinase-activating gene-1 (Rag-1) knockout mice, which are deficient in both B and T cells, die within 3 to 4 weeks after infection due to overwhelming virus replication in the gray matter (Drescher et al., 1999). To determine whether HLA-DQ6 and HLA-DQ8 would protect β2m°Aβ° mice from acute neuronal disease, we performed pathologic analysis on spinal cord and brain sections, virus plaque assay to detect replicating virus, dot blot to detect virus RNA, and immunoperoxidase staining to detect virus antigen expression.

At day 7 p.i., β2m°Aβ° (n = 3), β2m°Aβ°DQ6 (n = 3), β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (n = 4), and β2m° (n = 3) mice had similar high titers of infectious replicating virus isolated by plaque assay (7.7 ± 0.2, 6.4 ± 0.3, 5.5 ± 0.2, and 6.9 ± 0.1 log10 of replicating virus per gram of CNS tissue, respectively). By day 17 the amount of viral RNA quantitated by dot blot hybridization assay was decreased approximately twofold in β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m° mice compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (data not shown). In contrast, β2m°Aβ°viral RNA was twofold higher than that of β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice and fourfold higher than that of β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m° mice. By day 21 high titers of infectious virus persisted in the CNS in five of six β2m°Aβ° mice (5.0 ± 0.5 log10) and in three of six β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice (4.0 ± 0.5 log10). However, by this time point the level of infectious virus in the CNS of β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m° mice was below the level of detection of the plaque assay. These results indicate that the DQ6 transgene was most effective in controlling replicating virus in the CNS during the acute phase of the disease, and this level of control was comparable to endogenous mouse class II.

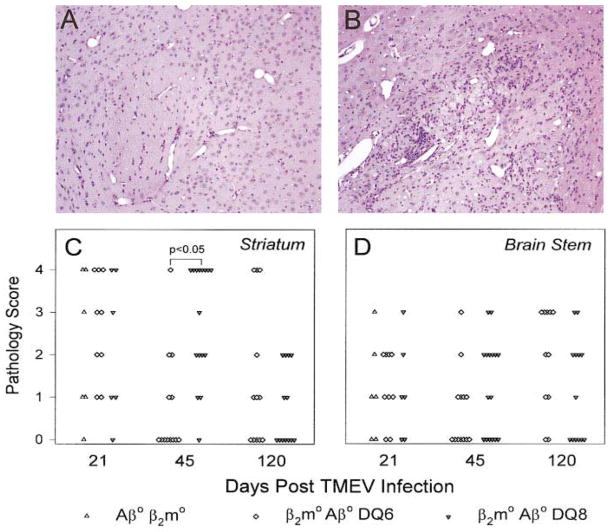

Previously, we demonstrated that distinct arms of the immune system protect specific regions of the brain from TMEV-induced damage (Drescher et al., 1999). To determine if the expression of human class II transgenes influenced acute brain disease, we examined the brains of β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice at days 21 p.i. Severe pathology characterized by inflammation, parenchymal damage, neurophagia, and tissue destruction was observed in the hippocampus (data not shown) and striatum (Fig. 3) of TMEV-infected mice. No significant differences in the level of brain pathology were found between the β2m°Aβ°DQ8, the β2m°Aβ°DQ6, and the β2m°Aβ°mice in the cerebellum, brain stem, and cortex (data not shown; Fig. 3). These results indicate that expression of DQ8 and DQ6 genes did not influence the extent and severity of acute neuronal disease in the brains of TMEV-infected mice.

FIG. 3.

Illustration of the pathology in the striatum (A, B) and quantification of brain disease (C, D) in β2m°Aβ°, β2m°Aβ°DQ6, and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice following infection. Each symbol represents an individual mouse graded at each area of the brain according to the scale detailed under Experimental Methods. No differences in striatum and brain-stem pathology were observed in β2m°Aβ°, β2m°Aβ°DQ6, or β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice at day 21 p.i. By day 45 p.i., β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice (B) experienced significantly more disease in the striatum compared with the β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice (A) (P < 0.05). By day 120 p.i. both groups had similar levels of pathology in the striatum and brain stem. (Original magnification for A and B was 150×.)

Previous experiments have indicated that acute viral infection of neurons in the gray matter of the spinal cord may contribute to death of Scid and Rag −/− mice infected with TMEV (Drescher et al., 1999). To address the contributions of DQ genes to acute neuronal disease in the spinal cord, we studied 10–15 spinal cord sections from each mouse for the presence or absence of gray matter disease and inflammation. Gray matter pathology was statistically increased in β2m°Aβ° mice compared to HLA-DQ transgenic animals (P < 0.05; Table 1). Anterior horn cell neurons from β2m°Aβ°mice showed vacuolar changes and necrosis compared to the β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice, indicating that the expression of HLA-DQ8 or HLA-DQ6 lessened the extent and severity of acute neuronal infection of the spinal cord. However, the gray matter inflammation observed in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice was not statistically different compared to C57BL/6 × 129 β2m° mice that express endogenous mouse class II (Table 1).

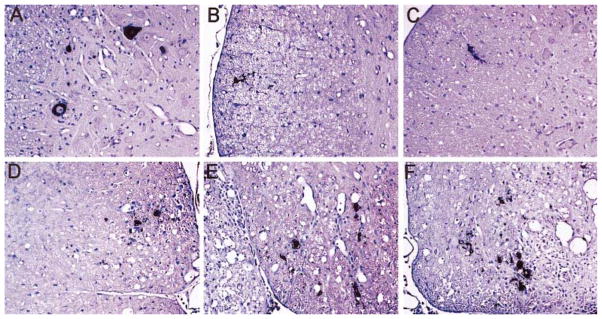

Immunostaining revealed that β2m°Aβ° mice had increased numbers of TMEV-positive cells (0.9 ± 0.2 positive cells / mm2; Fig. 4A) in the gray matter of the spinal cord at day 21 p.i. compared with β2m°Aβ°DQ6 (0.1 ± 0.1; Fig. 4B) and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (0.1 ± 0.1; Fig. 4C) mice (P < 0.05). β2m°Aβ° mice expressed TMEV antigens at this time point almost exclusively in cells morphologically identified as neurons. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that human class II molecules control virus in the gray matter of the spinal cord.

FIG. 4.

Virus antigen localization in the spinal cords of TMEV-infected mice at days 21 (A, B, C) and 120 postinfection (D, E, F). (A) Prominent immunoreactivity to TMEV was observed in the gray matter of β2m°Aβ° mice at day 21 p.i. In either (B) β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice or (C) β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice, virus was cleared completely from the gray matter and localized exclusively to glial cells in the white matter of the spinal cord at day 21. At day 120 p.i., increased numbers of TMEV-positive cells were observed in the white matter of (D) β2m°, (E) β2m°Aβ°DQ6, and (F) β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice compared to the 21-day time point. This localization (in glial cells of the spinal cord white matter) was comparable to that observed at day 45 p.i. Staining was performed using the immunoperoxidase technique with polyclonal rabbit antisera to TMEV that recognizes VP1, VP2, and VP3 viral capsid proteins. The dark reaction product identifies virus antigen-positive cells. The sections were lightly counter-stained with Meyer’s hematoxylin. (Original magnification for A–F was 140×.)

β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 Mice Have Viral Persistence in the White Matter of the Spinal Cord and Brain Disease during the Chronic Phase of Disease

In mice of a susceptible haplotype, infection with TMEV results in virus persistence in glial cells and macrophages of the spinal cord white matter (Dal Canto and Lipton, 1982). We asked whether β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice that survived the acute neuronal infection would ultimately develop virus persistence in the spinal cord white matter. Even though the amount of infectious replicating virus following 45 days of infection was below the level of detection by plaque assay, abundant virus antigen was detected in the spinal cord white matter of β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice. Increased virus antigen-positive cells were detected in the spinal cords of β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice (8.3 ± 2.2 virus antigen-positive cells/mm2) compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice (4.3 ± 1.2). At a later time point (120 days p.i.), equal numbers of TMEV-positive cells were identified in the spinal cord white matter of β2m°Aβ°DQ6 (Fig. 4E) and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (Fig. 4F) mice (4.8 ± 0.5 and 4.6 ± 0.5 positive cells/mm2 white matter, respectively). This localization of TMEV antigens (in glial cells of the white matter) was similar to that observed in β2m° mice that express endogenous murine class II (Fig. 4D), demonstrating that the expression of the HLA transgenes does not alter the pattern of virus persistence in this model. This finding supports the hypothesis that β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice have the capacity to initially control the infection more efficiently than β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice, which alters the timing and rate of the disease progression.

We also examined whether the level of brain disease observed in the transgenic mice changed during the chronic phase of the disease (greater than day 21 p.i.). By 45 days p.i., β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice had significantly higher levels of disease in the striatum compared to the β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice (Fig. 3; P < 0.001). The finding that disease levels observed in the striatum were different in the β2m°Aβ°DQ6 versus the β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice is consistent with previous data that the class II-mediated immune response influences protection of this region of the brain (Drescher et al., 1999). However, no other significant differences in other brain areas were observed between mice at 45 days p.i. despite the presence of extensive disease in the hippocampus, brain stem, corpus callosum, and cortex (data not shown). β2m°Aβ° mice were unavailable for examination at this time point due to death during the acute disease. By day 120 p.i. similar levels of brain disease were observed between the β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and the β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice (Fig. 3). At this time point, moderate disease was still apparent in the brain stem, cortex (data not shown), and striatum. The reduction in striatum pathology observed in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 at day 120 p.i. compared to day 45 p.i. can be explained by a 30% mortality of β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice between these two time points. It is likely that the mice with the most severe spinal cord and brain pathology died during this chronic phase of the disease, leaving the mice with lessor pathology scores to be assessed at day 120 p.i.

HLA-DQ8 Expression Results in Earlier and More Extensive Demyelination in the Spinal Cord White Matter

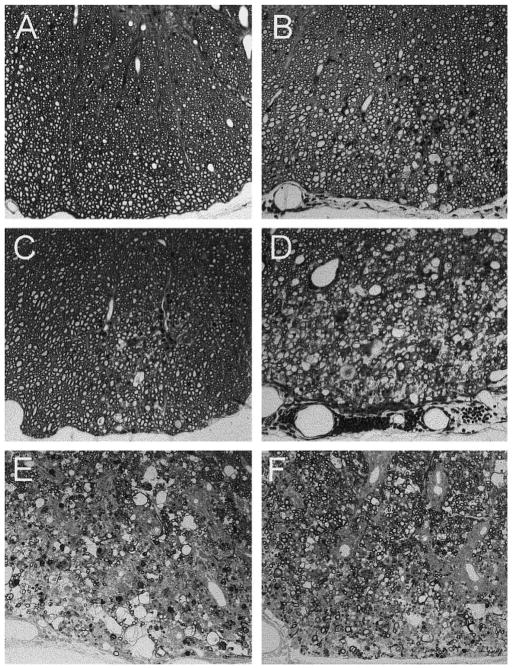

Demyelination was not detected in β2m°Aβ° mice following TMEV infection. Three hypotheses may explain this observation: (1) the mice die during the acute phase of the disease at a point that is too early for demyelination to occur, (2) virus may not replicate in the spinal cord white matter in the absence of endogenous class I and II, or (3) the immune system is required for demyelination to commence. Previous work from our laboratory using Scid mice has demonstrated that these mice can demyelinate if low numbers of splenocytes are adoptively transferred near the time of infection (Rodriguez et al., 1996). To test if expression of a human class II gene can convert β2m°Aβ° mice to a demyelinating phenotype, we quantitated the amount of gray matter inflammation, meningeal inflammation, and demyelination in β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice at day 45 p.i. This time point was chosen because it has been used previously to determine susceptibility or resistance to demyelination (Rodriguez and David, 1985). As nontransgenic β2m°Aβ° mice die by day 24 p.i., prior to the onset of demyelination (Fig. 5A), β2m° mice were used as controls for these experiments. These mice are on a resistant C57BL/6 × 129 background and lack MHC class I, which makes them susceptible to demyelination (Rodriguez et al., 1986a). However, these mice do express endogenous mouse class II genes. At day 45 p.i., β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice had a significantly increased level of meningeal inflammation and demyelination compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m° mice (Table 1; P < 0.05). In addition, the lesions in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (Fig. 5D) mice were more extensive than those observed in either β2m°Aβ°DQ6 (Fig. 5C) or β2m° mice (Fig. 5B). These data demonstrate that expression of a human class II gene in the absence of class I MHC provides a sufficient immune response to allow demyelination to begin, and human class II genes differentially modulate the level of white matter disease in the spinal cord resulting from TMEV infection. By day 120 p.i., extensive demyelination and meningeal inflammation was observed in both the β2m°Aβ°DQ8 (Fig. 5E) and the β2m°Aβ°DQ6 (Fig. 5F) mice, and this pathology was more significant than that observed in β2m° mice (C57BL/6 background) (Table 1; P < 0.05). The pathology scores observed at day 120 p.i. in C57BL/6 β2m° mice are comparable to those previously observed in C57BL/6 × 129 β2m° (Rodriguez et al., 1993). This indicates that the human transgenes did not provide complete protection from disease, but rather affected the timing of disease. Both strains of mice ultimately develop comparable levels of pathology in the spinal cord white matter; however, neither human class II molecule is as effective as endogenous mouse class II at protecting from demyelination.

FIG. 5.

Demyelination and meningeal inflammation in the spinal cord of mice after infection with TMEV. (A) No demyelination was observed in β2m°Aβ° mice prior to death (day 21 p.i.). (B) β2m° mice that express endogenous mouse class II molecules developed small demyelinated lesions with meningeal inflammation by day 45 p.i. (C) β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice also developed demyelination by day 45 p.i., but these were on average smaller and less frequent that in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice (see Table 1). (D) In contrast, well-formed demyelinated lesions developed in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice by day 45 p.i. Note the denuded axons and the moderate inflammation in these mice. By day 120 p.i., both (E) β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and (F) β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice developed similar large demyelinated lesions in the spinal cord white matter. As β2m°Aβ°mice died by 3 to 4 weeks p.i., β2m° mice were used as controls for the later time point experiments. Spinal cord sections were embedded in glycol methacrylate plastic and stained with a modified erichrome/cresyl violet stain. (Original magnification for A–F was 160×.)

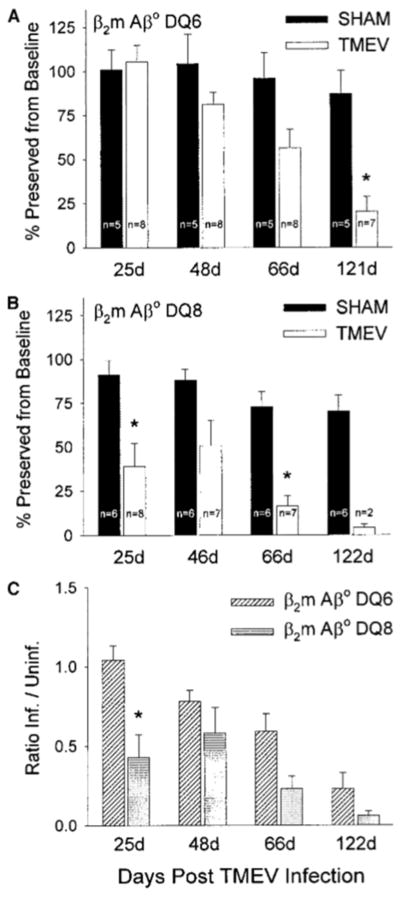

β2m°Aβ°DQ8 Mice Develop Earlier and More Pronounced Neurologic Deficits Compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ6 Mice

Progressive demyelination following TMEV infection is usually associated with chronic progressive neurologic deficits. However, there are examples in mice on a normally resistant MHC background with deficiency of either class I MHC (Rivera-Quinones et al., 1998) or perforin (Murray et al., 1998) in which demyelination can occur with minimal neurologic deficits. To determine if expression of human class II genes was associated with the development of neurologic deficits, we used the rotarod assay to objectively measure motor balance, coordination, and control. To account for intracerebral injection and age, we used sham-infected, age-matched mice as controls. This assay revealed significant decreases in the performance of TMEV-infected β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice compared with sham-infected controls by day 25 p.i. (Fig. 6B). Of interest, β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice were protected from this early disruption of motor coordination following TMEV infection (Fig. 6A). When ratios of infected/uninfected (sham) rotarod performances were calculated to allow for interstrain comparisons, β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice had a 59% reduction in function compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice at day 25 p.i. (Fig. 6C). Following day 25 p.i., both β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice had reductions in rotarod performance over time, consistent with the development of demyelination (Figs. 6A, 6B, and 6C). These data demonstrate that despite the ability of a β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mouse to mount an immune response to TMEV, the response was not sufficient to protect from motor dysfunction. In addition, despite the decrease in viral burden, β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice were ultimately susceptible to the progressive neurologic deficits as a result of TMEV infection; however, the development of neurologic deficits was delayed.

FIG. 6.

Assessment of neurologic function in β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 transgenic mice. (A) β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice did not develop statistically significant neurologic deficits until 66 days following TMEV infection compared with sham-infected control mice. (B) In contrast, TMEV-infected β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice developed significant decrease in function by day 25 p.i. (Asterisks signify a significant decrease in rotarod performance between sham- and TMEV-infected mice by Student’s t test—P < 0.05.) (C) Ratios of infected/uninfected (sham) rotarod performances were calculated to allow interstrain comparisons. Ratios equivalent to 1 signify no difference between the infected group and the respective sham-infected control. Data are expressed as the ratios of infected/sham-infected rotarod performance. β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice a showed significant decrease in rotarod performance at day 25 p.i. compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice. Both strains had ratios less than 1 at days 48, 66, and 122 p.i., indicative of neurologic deficits resulting from the demyelinating phase of the disease. (Asterisk signifies significant decrease in rotarod performance between β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice by Student’s t test—P < 0.05.)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the effects of human DQ polymorphisms in a mouse model of chronic virus- induced immune-mediated demyelination and neurologic deficits. Initially, we examined Aβ°DQ6 and Aβ°DQ8 mice expressing endogenous mouse class I. These mice survived through 7 weeks p.i. and showed minimal pathology and no neurologic deficits. To study the effects of the human DQ polymorphisms on TMEV-induced demyelinating disease, we studied the human DQ genes in mice lacking expression of endogenous class I and class II (β2m°Aβ° mice), since the deletion of β2m° from resistant mice results in susceptibility to demyelination (Rodriguez et al., 1993). Normally, β2m°Aβ° mice are highly susceptible to death during the acute phase of TMEV infection, as a result of overwhelming virus replication in neurons. Most of the mice expressing either DQ6 or DQ8 survived the acute disease, indicating that expression of a single DQ gene in a β2m°Aβ° mouse mounted an immune response that was sufficient to allow for survival during the acute disease. Of particular interest, the human transgenes elicited strong class II-mediated immune responses (antibody and DTH) directed against virus antigen. β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice were equally effective in mounting a neutralizing humoral immune response to TMEV that may have enhanced survival during the acute phase of the disease (or prevented overwhelming encephalitis). However, the resulting immune response was not completely protective, as approximately 40% of the β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice died during the acute phase of disease. Interestingly, β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice had an increased survival advantage over β2m° mice, which express endogenous mouse class II, during the acute phase of disease. In mice expressing DQ6 and DQ8 that survived the acute phase of the disease, the virus persisted in the spinal cord white matter, which resulted in demyelination and subsequent progressive neurologic deficits. The class I-mediated response appeared to be critical for protection from demyelination since both β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice ultimately developed demyelination and subsequent chronic neurologic deficits. The results are consistent with previous findings demonstrating that resistance genetically maps to H-2D (Rodriguez et al., 1986a) and is associated with the ability to mount a class I-mediated CTL response against virus (Rodriguez and David, 1985).

Of interest was the observation that in addition to the effects on survival, the HLA-DQ genes also differentially influenced chronic pathology in the spinal cord. The level of demyelination observed in the β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice was more severe than that seen in the β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice at 45 days p.i., yet both strains had comparable levels of demyelination at a later time point. There are two explanations as to why DQ6 versus DQ8 had different effects on chronic immune-mediated demyelination following TMEV infection. First is the possibility that DQ6 was more efficient in clearing virus from the CNS compared to DQ8. The higher levels of infectious virus by plaque assay and viral RNA during the acute phase of the disease (7–21 days) in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice versus β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice support this hypothesis. More virus antigen-positive cells were found in the spinal cord white matter of β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice at a time point when the demyelinating phase was active (45 days postinfection). This would imply that the DQ8-mediated CD4+ T cell response was less efficient than the DQ6-mediated CD4 response in clearing the virus from the CNS. Thus, the decrease in demyelination in β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice may have been related to less persistent virus antigen. The second possibility is that the DQ8 transgene directly participated in enhanced pathogenesis compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice. This is of interest because some data support the conclusion that a more vigorous DTH response to virus antigen is associated with more demyelination and neurologic deficits (Clatch et al., 1985). In support of this hypothesis, β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice showed higher levels of virus-specific DTH responses compared to β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice. Alternatively, DQ8 may have predisposed animals to immune recognition of autoantigens from myelin epitopes as a result of either molecular mimicry (Old-stone, 1998) or epitope spreading (Tuohy et al., 1998). These hypotheses, however, are not mutually exclusive, as the failure of viral clearance may have predisposed the mice to enhanced immune-mediated pathology restricted to the human class II molecule.

Previous work from our laboratory has demonstrated that β2m° mice from a resistant C57BL/6 × 129 background that express endogenous mouse class II do not develop clinical disease despite their susceptibility to demyelination (Rivera-Quinones et al., 1998). In contrast, class II-deficient mice develop severe neurologic deficits and early death following TMEV infection (Njenga et al., 1996). In the absence of endogenous class I, the DQ6 and DQ8 transgenes have different abilities to modulate demyelination. However, neither DQ molecule was as effective as endogenous mouse class II at protecting from demyelination during the late chronic stage of disease (day 120 p.i., Table 1). To determine whether expression of human class II would be associated with the development of neurologic deficits, we performed rotarod analyses on mice expressing DQ6 or DQ8 to assess motor control, balance, and coordination. In contrast to the situation with class I-deficient mice expressing endogenous mouse class II MHC, both β2m°Aβ°DQ6 and β2m°Aβ°DQ8 transgenic mice developed progressive neurologic deficits. The neurologic deficits in the β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice occurred during both the acute and the demyelinating phases of disease. During the acute phase of the disease, the mice showed significantly reduced rotarod performances by day 25 p.i. This most likely resulted from the increased viral burden in β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice. The neurologic disease stabilized between days 25 and 45 p.i. However, between days 66 and 120 p.i. another severe loss of motor function was observed. This resulted in the death of five β2m°Aβ°DQ8 mice between these two time points. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the cumulative effects of significant neurologic injury induced during both the acute and the demyelinating phases of the disease result in increased mortality. The β2m°Aβ°DQ8 survival curve shown in Fig. 1 also supports this hypothesis. In contrast, β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice did not show neurologic deficits until approximately day 66 p.i., which is suggestive that the loss of function resulted from demyelination and not acute neuronal injury. By day 120 p.i. β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice showed comparable reductions in motor function. Therefore, the development of neurologic deficits is not only influenced by the presence or absence of class I, but may be influenced in this experimental paradigm by human class II genes (in this case DQ genes) and the ability to control virus replication. Several lines of research have highlighted the influence of class II genes in TMEV-induced demyelination and neurologic deficits. These include the observation that (1) class II gene expression is induced in the CNS following TMEV infection (Rodriguez et al., 1987), (2) monoclonal antibody therapy to mouse class II MHC is effective in reducing the extent of demyelinating disease in susceptible SJL/J mice (Rodriguez and Sriram, 1988), and (3) different Ia alleles in congenic mice influence the extent of demy- elination observed following Theiler’s virus infection (Rodriguez and David, 1985). It is also possible that the genetic background of β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 mice contributed to their susceptibility to neurologic disease, because the original experiment showing demyelination and minimal neurologic deficits in class I-deficient mice was done on the C57BL/6 × 129 background (Rivera-Quinones et al., 1998).

The data from these human transgenic mice infected with a mouse pathogen parallel the scenario reported in some epidemiological studies on human multiple sclerosis, indicating that some individuals with the DQ6 gene have a less severe disease course than their counterparts expressing the DQ8 gene. Preliminary studies using an autoimmune model of MS induced by immunization with mouse myelin illustrate a similar phenomenon that EAE is dramatically worse in transgenic mice expressing DQ8 compared to those expressing DQ6 (Das et al., 1999). This raises the possibility that part of the mechanism for demyelination and neurologic deficits observed in mice expressing DQ8 versus DQ6 mice may be similar between virus-induced and autoimmune demyelination and by analogy multiple sclerosis. Thus, these mice may provide investigators with a unique and novel in vivo model that more closely reflects the influence of human class II genes on neurologic disease.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Virus

The Daniel’s strain of TMEV was used for all experiments (Lipton, 1975).

HLA-DQ Transgenic Mice

Aβ°DQ8 (HLA-DQA1*0301, HLA-DQB1*0302) and Aβ°DQ6 mice (HLA-DQA1*0103, HLA-DQB1*0601) were generated as described previously (Raju et al., 1998). β2m°Aβ°DQ8 and β2m°Aβ°DQ6 were generated by crossing the corresponding Aβ°DQ transgene-positive mice to β2m° mice. Littermate control Aβ° mice negative for DQ8 or DQ6 mated to β2m° were used to generate β2m°Aβ° mice. The presence of the transgenes was determined by PCR and expression was determined by flow cytometry as previously described (Raju et al., 1998). A minimum of five Aβ°DQ8 and Aβ°DQ6 founder lines were examined to determine transgene copy number and RNA/protein expression levels. These lines were used to select single Aβ°DQ8 and Aβ°DQ6 lines with comparable high transgene copy numbers and expression levels for experimentation. The expression of HLA-DQ6 and DQ8 molecules in the selected lines was comparable on peripheral blood lymphocytes (35% vs 30%), splenocytes (51% vs 42%), and thymocytes (7.5% vs 7.2%) using flow cytometry. Transgenic mice were housed and bred at the Mayo Immunogenetics mouse colony. C57BL/6 × 129 β2m° mice were a kind gift from R. Jaenisch, Whitehead Institute (Cambridge, MA). Additional C57BL/6J mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). At 4 to 6 weeks of age mice were intracerebrally inoculated with 2 X 106 PFU of TMEV in a 10-μl volume. Care and handling of mice conformed to the guidelines of both the National Institutes of Health and the Mayo Clinic Animal Care and Use Committee.

Survival Analysis

Mice were monitored throughout the time of infection and deaths were recorded at the end of each week.

Immunoperoxidase Staining

Ten-micrometer spinal cord sections from infected mice were cut from tissue frozen in OCT mounting media (Miles, Inc., Elkhart, IN). Sections were fixed in cold acetone and stained with an anti-DQ, DR, DP antibody from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA) using the avidin–biotin immunoperoxidase technique (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Detection was performed with Hanker–Yates (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) using hydrogen peroxide as the substrate. Virus staining was performed on paraffin-embedded sections. Slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through an alcohol series and stained with polyclonal rabbit anti-TMEV sera as previously described (Rodriguez et al., 1983) also using the avidin–biotin immunoperoxidase technique (Vector Laboratories). Slides were lightly counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Gray and white matter areas were quantitated with a Zeiss photomicroscope with a Zidas interactive camera lucida system. Data were expressed as the number of virus-positive cells/mm2 of gray or white matter areas sampled as previously described (Patick et al., 1991). Photography was performed using an Olympus AX70 scope fitted with a SPOT cooled color digital camera.

Virus-Specific Antibody Isotype Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Whole blood was collected from mice at time of sacrifice, and sera were isolated and stored at –80°C. Total serum IgGs and IgMs against TMEV were assessed by ELISA as described (Njenga et al., 1996). Virus was adsorbed to 96-well plates (Immulon II; Dynatech Laboratories Inc., Chantilly, VA) and then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in PBS. Serial serum dilutions were made in 0.2% BSA/PBS and were added in triplicate. Biotinylated anti-mouse IgG or IgM secondary antibodies were used for detection (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Westbury, NY). Signals were amplified with streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) and detected using p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate. Absorbances were read at 405 nm and plotted against serum dilution factors.

Virus-Neutralization Assay

Virus-specific neutralizing antibody titers were determined as described (Rodriguez et al., 1983). Samples of TMEV, diluted to contain 100 PFU, were mixed with an equal volume of serial twofold dilutions of heat-inactivated (56°C for 45 min) serum from TMEV-infected mice. After incubation at 25°C for 1 h, virus serum mixtures were assayed for infectivity by plaque assay on L2 cells. Neutralization titers were expressed as the dilution of serum that reduced the number of virus plaques by 50%.

Delayed-Type Hypersensitivity Responses to Virus

Mice were challenged with an intradermal injection in the pinna of the ear with 5 μg purified, UV-inactivated TMEV in a 10-μl volume. Prechallenge ear thickness measurements were taken with a Peacock dial gauge G-50 micrometer (Ozaki Manufacturing Co.) and expressed in mm−2. Postchallenge measurements were taken at 24 and 48 h postinjection.

Histopathology

Twenty-one, 45, and 120 days after virus infection, mice were anesthetized with 0.2 ml of pentobarbital (i.p.) and perfused by intracardiac infusion of Trump’s fixative. Spinal cords were sectioned coronally into 30 to 35 1-mm blocks. Every third block was postfixed in osmium tetroxide and embedded in glycol methacrylate plastic and 1-μm sections were stained with a modified erichrome stain (Pierce and Rodriguez, 1989). This technique has previously been shown to stain myelin sheaths and allows one to distinguish between myelinated and demyelinated axons (Pierce and Rodriguez, 1989). Additional blocks were embedded in paraffin for virus antigen staining. Two coronal cuts were made in the brain (one section through the optic chiasm and a second section through the in infundibulum). This resulted in three blocks that were then embedded in paraffin. The resulting slides from the brain were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Drescher et al., 1999). Photography was performed using an Olympus AX70 scope fitted with a SPOT cooled color digital camera.

Pathologic Analysis

Detailed pathologic analysis was performed on spinal cord and brain sections. Gray matter inflammation, meningeal inflammation, and demyelination were assessed on 12 to 15 coronal spinal cord sections per mouse without knowledge of genotype. Each section was scored for the presence of pathology in each of the four spinal cord quadrants as previously described (Paya et al., 1989, 1990). A maximum score of 100 reflects the presence of pathology in all quadrants of every spinal cord block from an individual spinal cord. Brain sections were assessed morphologically by grading the extent of pathology in different brain regions. The cerebellum, brain stem, cortex, hippocampus, striatum, and corpus callosum were analyzed. Each area of the brain was graded on a scale of 0 to 4 as previously described (Drescher et al., 1999). A score of 0 reflects the absence of pathology, a 1 reflects no tissue destruction but minimal inflammation, a 2 reflects early tissue destruction (loss of architecture) and moderate inflammation, a 3 reflects definite tissue destruction (demyelination, parenchymal damage, cell death, neurophagia, neuronal vacuolization), and a 4 represents necrosis (complete loss of all tissue elements with associated cellular debris).

Virus Plaque Assay

Virus titers in brain and spinal cords were performed at days 7, 21, and 45 after TMEV infection. Assays were performed as described (Rodriguez et al., 1986b). Briefly, brain and spinal cords were homogenized with a variable speed tissue homogenizer to yield a 10% wt/vol homogenate in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD). Samples were sonicated with three 1-min bursts, clarified by centrifugation, and stored at –70°C until the time of plaque assay. The assay was performed on L2 cells without knowledge of mouse strain. All dilutions were done in triplicate.

Dot Blot Hybridization

CNS tissues were homogenized in RNA Stat-60 (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, TX) and total RNA was isolated from the brains and spinal cords of TMEV-infected mice per the manufacturer’s guidelines. RNA samples were loaded onto Zeta-Probe blotting membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) following the manufacturer’s guidelines for the Bio-Dot SF microfiltration apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Dot blot membranes were washed and then hybridized with a 32P-labeled probe specific for the VP1 portion of TMEV, a major capsid protein. To control for the amount of RNA loaded, membranes were stripped and reprobed with a probe for the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Relative levels of RNA were assessed using a PhosphorImager scanning system and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Rotarod Analysis

A Rotamex rotarod (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) was used to assess balance, coordination, and motor control. This device monitors the ability of a mouse to stay on a rotating rod at constant speed or with acceleration as previously described (McGavern et al., 1999). Briefly, mice were trained with a constant speed assay for 3 days prior to collecting preinjection baseline data using an accelerated assay. Mice were then injected with TMEV or PBS and assessed at specific time points postinfection using an accelerated rotarod assay. PBS-injected mice served as controls for intracerebral injection and age. Data were expressed as percentage preserved function from baseline-accelerated performances per mouse to control for variations in the abilities of individual mice. These percentages were then averaged and used to calculate standard errors for each group. To allow comparisons between DQ6 and DQ8 transgenic mice, data were expressed as ratios of infected divided by sham (PBS)-infected performances for the individual strains.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA for normally distributed data. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Student–Newman–Keuls method (P < 0.05). Brain pathology scores and data that were not distributed normally were analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA on ranks. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Dunn method (P < 0.05). Comparisons between two individual groups were done using the Student t test (P < 0.05). Survival curves were compared at various time points postinfection using the χ2 test. Statistical differences between infected and sham-infected rotarod performances at various time points postinfection were assessed using a Student t test (P < 0.05).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants NS 24180 and NS 32129 (M.R.) and AI14764 (C.S.D.). K.M.D. is a fellow of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. D.B.M. is supported by a predoctoral NRSA from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant 1F31ME12120). We appreciate the generous financial support of Ms. Kathryn Petersen and Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Applebaum for this project.

References

- Aldrich MS. Diagnostic aspects of narcolepsy. Neurology. 1998;50(2 Suppl 1):S2–S7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.2_suppl_1.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpsoy E, Yilmaz E, Coskun M, Savas A, Yegin O. HLA antigens and linkage disequilibrium patterns in Turkish Behcet’s patients. J Dermatol. 1998;25:158–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1998.tb02372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubert C, Chamorro M, Brahic M. Identification of Theiler’s virus infected cells in the central nervous system of the mouse during demyelinating disease. Microb Pathog. 1987;3:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black C, Briggs D, Welsh K. The immunogenetic background of scleroderma—An overview. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:73–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash E, Bandeira A, Chirinian S, Brahic M. Characterization of B lymphocytes present in the demyelinating lesion induced by Theiler’s virus. J Immunol. 1989;143:984–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatch RJ, Melvold RW, Miller SD, Lipton HL. Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-induced demyelinating disease in mice is influenced by the H-2D region: Correlation with TMEV-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity. J Immunol. 1985;135:1408–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatch RJ, Miller SD, Metzner R, Dal Canto MC, Lipton HL. Monocytes/macrophages isolated from the mouse central nervous system contain infectious Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) Virology. 1990;176:244–254. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90249-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Canto MC, Lipton HL. Ultrastructural immunohistochemical localization of virus in acute and chronic demyelinating Theiler’s virus infection. Am J Pathol. 1982;106:20–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Drescher KM, Geluk A, Bradley DS, Rodriguez M, David CS. Complementation between specific HLA-DR and HLA-DQ genes in transgenic mice determines susceptibility to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Hum Immunol. 1999 doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(99)00135-4. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher KM, Murray PD, David CS, Pease LR, Rodriguez M. CNS cell populations are protected from virus-induced pathology by distinct arms of the immune system. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:21–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher KM, Nguyen LT, Taneja V, Coenen MJ, Leibowitz JL, Strauss G, Hammerling GJ, David CS, Rodriguez M. Expression of the human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen DR3 transgene reduces the severity of demyelination in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1765–1774. doi: 10.1172/JCI167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duquette P, Decary F, Pleines J, Boivin D, Lamareoux G, Cosgrove JB, Lapierre Y. Clinical subgroups of multiple sclerosis in relation to the HLA: DR alleles as possible markers of disease progression. Can J Neurosci. 1985;12:106–110. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100046795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin JJ, Volkman DJ, Wu P. Central nervous system abnormalities in Lyme neuroborreliosis. Neurology. 1991;41:1571–1582. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.10.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isreal EJ, Wilsker DF, Hayes KC, Schoenfeld D, Simister NE. Increased clearance of IgG in mice that lack beta 2-microglobulin: Possible protective role of FcRn. Immunology. 1996;89:573–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadotani H, Faraco J, Mignot E. Genetic studies in the sleep disorder narcolepsy. Genome Res. 1998;8:427–434. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kott E, Livni E, Zamir R, Kuritzky A. Cell-mediated immunity to polio and HLA antigens in amyotropic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1979;29:1040–1044. doi: 10.1212/wnl.29.7.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton HL. Theiler’s virus infection in mice: An unusual biphasic disease process leading to demyelination. Infect Immun. 1975;11:1147–1155. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.5.1147-1155.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton HL, Twaddle G, Jelachich ML. The predominant virus antigen burden is present in macrophages in Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelinating disease. J Virol. 1995;69:2525–2533. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2525-2533.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGavern DB, Zoecklein L, Drescher KM, Rodriguez M. Quantitive assessment of neurologic deficits in a chronic progressive murine model of CNS demyelination. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:171–181. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PD, McGavern DB, Lin X, Njenga MK, Leibowitz J, Pease LR, Rodriguez M. Perforin-dependent neurologic injury in a viral model of multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7306–7314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07306.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njenga MK, Pavelko KD, Baisch J, Lin X, David C, Leibowitz J, Rodriguez M. Theiler’s virus persistence and demyelination in major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. J Virol. 1996;70:1729–1737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1729-1737.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldstone MBA. Molecular mimicry and immune-mediated diseases. FASEB J. 1998;12:1255–1265. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.13.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olerup O, Hillert J, Fredrickson S, Olsson T, Kan-Hansen S, Moller E, Carlsson B, Wallin J. Primary chronic progressive and relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis: Two immunologically distinct disease entities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7113–7117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patick AK, Thiemann RL, O’Brien PC, Rodriguez M. Persistence of Theiler’s virus infection following promotion of central nervous system remyelination. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1991;50:523–537. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paya CV, Leibson PJ, Patick AK, Rodriguez M. Inhibition of Theiler’s virus-induced demyelination in vivo by tumor necrosis factor alpha. Int Immunol. 1990;2:909–913. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.9.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paya CV, Patick A, Leibson PJ, Rodriguez M. Role of natural killer cells as immune effectors in encephalitis and demyelination induced by Theiler’s virus. J Immunol. 1989;143:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce ML, Rodriguez M. Erichrome stain for myelin on osmicated tissue embedded in glycol methacrylate plastic. J Histotech. 1989;12:35. [Google Scholar]

- Prineas JW, Wright RG. Macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells in the perivascular compartment in chronic multiple sclerosis. Lab Invest. 1978;38:409–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju R, Munn SR, Majoribanks C, David CS. Islet cell autoimmunity in NOD mice transgenic for HLA-DQ8 and lacking I-Ag7. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:561. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)01404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Quinones C, McGavern D, Schmelzer JD, Hunter SF, Low PA, Rodriguez M. Absence of neurological deficits following extensive demyelination in a class I-deficient murine model of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 1998;4:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, David CS. Demyelination induced by Theiler’s virus: Influence of the H-2 haplotype. J Immunol. 1985;135:2145–2148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Dunkel AJ, Thiemann RL, Leibowitz J, Zijlstra M, Jaenisch R. Abrogation of resistance to Theiler’s virus-induced demyelination in H-2b mice deficient in β 2-microglobulin. J Immunol. 1993;151:266–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Leibowitz J, David CS. Susceptibility to Theiler’s virus-induced demyelination: Mapping of the gene within the H-2D region. J Exp Med. 1986a;163:620–631. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.3.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Lafuse W, Leibowitz J, David CS. Partial suppression of Theiler’s virus-induced demyelination in vivo by administration of monoclonal antibodies to immune response gene products (Ia antigens) Neurology. 1986b;36:964–970. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.7.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Leibowitz JL, Lampert PW. Persistent infection of oligodendrocytes in Theiler’s virus-induced encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:426–433. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Lucchinetti CF, Clark RJ, Yaksh TL, Markowitz H, Lennon VA. Immunoglobulins and complement in demyelination induced in mice by Theiler’s virus. J Immunol. 1988;140:800–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Pavelko KD, Njenga MK, Logan WC, Wettstein PJ. The balance between persistent virus infection and immune cells determines demyelination. J Immunol. 1996;157:5699–5709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Pierce ML, Howie EA. Immune response gene products (Ia antigens) on glial and endothelial cells in virus-induced demyelination. J Immunol. 1987;138:3438–3442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Sriram S. Successful therapy of TMEV-induced demyelination (DA strain) with monoclonal anti lyt2.2 antibody. J Immunol. 1988;140:2950–2955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tola MR, Caniatti LM, Casetta I, Granieri E, Conighi C, Quatrale R, Monetti VC, Paolino E, Govoni V, Pascarella R. Immunogenetic heterogeneity and associated autoimmune disorders in myasthenia gravis: A population-based survey in the province of Ferrara, northern Italy. Acta Neurol (Scand) 1994;90:318–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb02731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuohy VK, Yu M, Yin L, Kawczak JA, Johnson JM, Mathisen PM, Weistock-Guttman B, Kinkel RP. The epitope spreading cascade during progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Immunol Rev. 1998;164:93–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker BG, Santrach P, Bissonet AS, McDonnell SK, Schaid D, Moore SB, Rodriguez M. Major histocompatibility complex class II alleles and the course and outcome of MS: A population-based study. Neurology. 1998;51:742–747. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanelli E, Krco CJ, Baisch J, Cheng S, David CS. Could HLA-DRB1 be a protective locus in rheumatoid arthritis? Immunol Today. 1996;16:274–276. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]