Abstract

There is a lack of research examining whether smoking cues in anti-tobacco advertisements elicit cravings, or whether this effect is moderated by countervailing message attributes, such as disgusting images. Furthermore, no research has examined how these types of messages influence nicotine withdrawn smokers’ cognitive processing and associated behavioral intentions. At a laboratory session, participants (N = 50 nicotine-deprived adults) were tested for cognitive processing and recognition memory of 12 anti-tobacco advertisements varying in depictions of smoking cues and disgust content. Self-report smoking urges and intentions to quit smoking were measured after each message. The results from this experiment indicated that smoking cue messages activated appetitive/approach motivation resulting in enhanced attention and memory, but increased craving and reduced quit intentions. Disgust messages also enhanced attention and memory, but activated aversive/avoid motivation resulting in reduced craving and increased quit intentions. The combination of smoking cues and disgust content resulted in moderate amounts of craving and quit intentions, but also led to heart rate acceleration (indicating defensive processing) and poorer recognition of message content. These data suggest that in order to counter nicotine-deprived smokers’ craving and prolong abstinence, anti-tobacco messages should omit smoking cues but include disgust. Theoretical implications are also discussed.

Mass media constitute a major source for exposure to smoking cues. This is even true of media intended to promote cessation; nearly half of televised anti-smoking public service announcements (PSAs) depict smoking cues (Cappella, Bindman, Sanders-Jackson, Forquer, & Brechman, 2009). Smoking cues, such as a visual depiction of an actor lighting and smoking a cigarette, may be incorporated in anti-tobacco advertisements in hopes of capturing smokers’ attention (Lee, Cappella, Lerman, & Strasser, 2011). Smoking cues in PSAs are often followed by negative graphic images in hopes of persuading smokers that smoking is dangerous, disgusting, and socially undesirable (Leshner, Bolls, & Wise, 2011). Although research has yielded similar results on the effects of smoking cue PSAs on smokers and former smokers’ responses, no research has replicated these findings among a sample of nicotine withdrawn smokers.

The Limited Capacity Model of Motivated Mediated Message Processing (LC4MP; Lang, 2006) offers a theoretical framework for addressing these questions. The LC4MP posits that humans have a limited amount of mental resources that can be allocated to processing message content. Sensory information in our environment is presumed to activate two motivational systems: appetitive/approach and aversive/avoid that then influence encoding and storage of message content and retrieval of information from memory networks. The appetitive system activates in response to pleasant stimuli (i.e., smoking cues for smokers; Robinson & Berridge, 1993) thereby enhancing encoding of content, whereas the aversive system activates to unpleasant stimuli (i.e., disgust images) thereby also resulting in greater encoding of mediated content (i.e., the negativity bias; Cacioppo, Gardner, & Berntson, 1999). However, if the aversive system becomes activated beyond a certain threshold, defensive processing may occur (Cacioppo et al., 1999).

Experimental work on the appetitive/incentivizing effects that smoking cues have on smokers and former smokers has yielded similar results over the past several years. Specifically, research has shown that smokers are hypersensitive to depictions of smoking cues, which has been found to elicit automatic approach tendencies in current and former smokers resulting in cue-elicited cravings (Robinson & Berridge, 1993; Tiffany, 1990). These findings have held true even when smoking cues are depicted in anti-tobacco commercials (Lee & Cappella, 2013). Indeed, existing evidence indicates that including smoking cues in anti-tobacco advertisements leads to increased ratings of pleasantness and greater attention to the message (Lee & Cappella, 2013; Sanders-Jackson et al., 2011), but also results in “boomerang” effects, such as increased craving, especially when the message includes weak arguments against smoking (Kang, Cappella, Strasser, & Lerman, 2009). In alignment with the cue-reactivity literature, the LC4MP would predict that smoking cues in PSAs would effectively capture smokers’ attention but would also trigger urges, potentially countering the persuasive intent of the message.

Aside from depicting smoking cues to capture attention, campaigns often employ visual depictions of disgust content in order to persuade smokers that smoking is disgusting and consequential on one’s health. Depictions of the short- and long-term consequences of smoking (e.g., body envelope violations, hygiene, and death) have been conceptualized as disgust-elicitors (Beaudoin, 2002; Haidt, McCauley, & Rozin, 1994; Leshner et al., 2011), and were used as disgust elicitors in all high disgust messages in this experiment. Research has indicated that although aversive, disgust serves to elicit attention to facilitate avoidance of harmful substances and identification of threats to survival (Cacioppo et al., 1999; Rubenking & Lang, 2014). In the context of anti-tobacco ads, research has shown that disgusting images elicit emotional responses associated with the aversive motivational system including increased self-reports of unpleasantness (Hammond, Fong, McDonald, Brown, & Cameron, 2004) and furrowing of the brow as seen with facial electromyography responses (Leshner et al., 2011). Moreover, disgust has been found to increase attention to and memory of message content (Leshner et al., 2011). However, when paired with additional aversive content such as fear or deception by tobacco companies, participants’ aversive systems became over-activated resulting in processing patterns indicative of a defensive cascade (Leshner et al., 2011; Leshner, Clayton, Bhanduri, & Bolls, 2013).

Overview of the Study and Hypotheses

The current study investigated how nicotine-deprived smokers cognitively process anti-tobacco advertisements selected to vary with respect to depictions of smoking cues and disgusting images. This group is of special interest because it may provide greater insight into how anti-tobacco messages impact smokers who are experiencing symptoms similar to those whom have taken the first step to make a quit attempt but may be vulnerable to craving and relapse. Based on the LC4MP, we predict that when smoking cues are presented (SC+) in the absence of disgusting images (low disgust; LD), they will activate the appetitive motivational system resulting in approach tendencies including increases in craving reports compared to three other message conditions (Hypothesis 1). Messages presenting disgust content (high disgust; HD without smoking cues (SC−) are predicted to activate the aversive motivational system resulting in avoidance tendencies including increased intentions to quit smoking compared to the three other message conditions (Hypothesis 2).

The LC4MP (Lang, 2006) would predict that messages activating the appetitive motivational system (SC+/LD) should result in increased attention and memory. The negativity bias hypothesis would predict that messages activating the aversive motivational system (SC−/HD) should also result in increased attention and memory as long as disgust does not over activate the aversive motivational system beyond a certain threshold (Cacioppo et al., 1999; Leshner et al., 2011). Moreover, messages not depicting either message attribute (SC−/LD) should be motivationally relevant to our sample since these messages are often designed to target tobacco smokers. Therefore SC−/LD messages should also result in increased attention and memory (Lang, 2006).

However, the critical research goal was to determine how messages depicting motivationally opposing attributes (i.e., smoking cues/appetitive and disgust images/aversive) interact with each other to influence on nicotine withdrawn smokers’ message processing and recognition memory compared to three other message conditions. For instance, disgust images might call for greater cognitive resources (i.e., due to the negativity bias) post smoking cue depictions thereby resulting in increased attention and memory. In this case, SC+/HD messages would result in the greatest amount of attention and memory relative to three other message conditions. Or, smoking cue depictions paired with the opposing motivational attribute of disgust might lead to cognitive/motivational dissonance resulting in defensive processing, as was found in an Event Related Potential (ERP) anti-tobacco study with a sample of tobacco smokers (Kessels, Ruiter, & Jansma, 2010). Therefore, we predict that SC+/HD messages will result in different levels of attention, that is, either greater cardiac deceleration or greater cardiac acceleration compared to the three other message conditions (Hypothesis 3) and better or worse recognition memory compared to three other message conditions (Hypothesis 4).

Method

Participants and Procedure

A power analysis was conducted to determine the necessary sample size for this experiment. The parameters were set with power (1 − β) at 0.80, 0.17 effect size f, and α = .05, one tailed. The results indicated a total sample size of 44 participants needed to detect statistical differences at the 0.05 statistical level for ANOVA: repeated measures, within factors. Therefore, a total of 62 participants were recruited for the experiment. Participants had to be between the ages of 18 and 70, report smoking at least 10 cigarettes per day for at least 12 months, and not currently attempting to quit smoking. Participants in the current study were instructed to abstain from smoking for a minimum of 12 hours before the laboratory session. Of the 62 participants enrolled, 3 were excluded because they reported a current cessation attempt and 9 failed to meet the criterion for biochemical abstinence verification (see below), leaving a total of 50 participants for analysis. The average amount of cigarettes smoked a day was M = 12.14 (SD = 5.41). Participants ranged in age from 19 to 54 (Mage = 30.30 years, SDage = 9.58) and the sample was 54% male. The ethnic composition of the sample was as follows: Caucasian (76%), Asian Americans (7%), African-Americans (6%), Hispanics (5%), and Other (6%).

Experimental sessions were held between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. on weekdays. Upon laboratory arrival, participants provided informed consent, reported when they last smoked a cigarette, and provided a breath sample for measurement of expired carbon monoxide (CO; Micro Smokerlyzer, Bedfont Scientific, Ltd.). A CO cutoff of 10 ppm or lower was the requirement to participate in the experiment (Benowitz et al., 2002). Those not meeting the CO requirement (≥10 ppm) were thanked and dismissed. Smokers then completed a battery of questionnaires. Next, they were seated 7 feet from a high definition 42″ LCD television set and were prepped for collection of psychophysiological data. Once all electrodes were securely placed, participants were shown a 2-minute nature video intended to promote acclimation to the lab environment.

Participants viewed a series of PSAs. After each, participants completed questionnaires assessing feelings of disgust, smoking urge, and intentions to quit smoking. Once this task was complete, participants were shown a 5-minute video clip (not related to tobacco) in order to clear short-term memory and to reduce any remaining emotional responses before beginning the recognition task. Participants were provided instructions for the audio recognition task and a 10-minute audio recognition task followed a brief practice trial. Once the recognition task was completed, participants were debriefed, compensated ($30 USD), thanked, and dismissed. The experiment lasted roughly 1-hour. This study was approved by a university Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Design

The experiment utilized a 2 (smoking cues) × 2 (disgust content) × 3 (multiple messages) repeated-measures design, with conditions varying with regard to smoking cues (present/absent, manipulated within-subject), disgust images (high/low, manipulated within-subject), and message. Smokers randomly watched three 30-second anti-tobacco advertisements in each smoking cue × disgust message condition, resulting in a total of 12 advertisements. Thus, message presentation was randomized within-subjects. Advertisements containing smoking cues (SC+) depicted an actor lighting and smoking a cigarette whereas absent smoking cue (SC−) messages did not depict an actor lighting and smoking a cigarette, or any other types of smoking cues (i.e., ashtray, a cigarette package, etc.). Messages were considered “high disgust” (HD) if negative graphic images, such as gross, repulsive and sickening images (e.g., body envelope violations, hygiene, and death; Haidt et al., 1994) that are associated with tobacco smoking were present whereas “low disgust” (LD) messages did not depict such images.

Anti-Tobacco Advertisements

Stimuli were selected from a collection of anti-tobacco PSAs produced in English and were pre-tested for depictions of smoking cues and disgust content. Coders (N = 3) rated the presence (1) and absence (0) of smoking cues depicted in 60 anti-tobacco messages. Coders were instructed that smoking cues consisted of an actor lighting and smoking a cigarette. Only advertisements in which smoking cues appeared within the first 15-seconds were selected to permit phasic analyses probing of how message processing was affected by subsequent introduction of disgust content (see below). Coders had perfect agreement on the presence/absence of smoking cues on 30 messages. Thirty undergraduate students rated how much each of these 30 messages depicted gross, repulsive, and sickening content on a Likert scale anchored by 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely (α = .83; Nabi, 2002). Participants in the pre-test were instructed to focus on rating the content as opposed to how the messages made them feel (O’Keefe, 2003). Based on the students’ ratings of disgust content, 12 messages (3 in each smoking cue × disgust message conditions) were eligible for inclusion and selected as the stimuli for the experiment.1 Student raters judged the selected HD advertisements to be higher in disgust than the LD messages, t(1, 49) = 20.06, p < .001; MHD = 3.92, SD = 0.57; MLD = 1.47, SD = 0.37). We also pre-tested messages on amount of fear depicted in each message in order control for fear/disgust covariation. Fear content was measured in each message by having participants rate the following three criteria: fearful, frightening, and scary (scale 1–5; α = .90; Dillard & Anderson, 2004). Paired samples t-tests revealed that the selected HD advertisements had significantly greater disgust than fear, t(1, 49) = 11.70, p < .001; MHD = 3.92, SD = 0.27; MHDFear = 2.01, SD = 0.70).

Measures

Nicotine Dependence and Withdrawal

Participants completed the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991), a 6-item measure of individual differences in nicotine dependence. The six items were summed together to compute a composite score for nicotine dependence (α = .87). Withdrawal symptoms were assessed using the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS; Hughes & Hatsukami, 1986). Smokers rated nine symptoms on a scale ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = absent to 4 = severe). The nine items were summed together to compute a composite score for nicotine withdrawal (α = .81).

Disgust Responses

Participants rated each ad immediately after exposure on three items designed to measure disgust responses using a 7-point Likert scale anchored by 1 = Strongly Disagree and 7 = Strongly Agree. Disgust items included: This message grossed me out; repulsed me; and made me sick to my stomach (Nabi, 2002). Each participant had one disgust score per ad. The three disgust scores for each message condition were then averaged together.2

Craving

A shortened version of the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Brief (QSU-B; Cox, Tiffany, & Christen, 2001; Toll, Katulak, & McKee, 2006; α = .90) was provided after exposure to each message. Participants responded to five items using a scale ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Each participant had one craving score per ad. The three craving scores for each message condition were then averaged together.

Ad-Induced Intentions to Quit

Smokers were asked to rate their likelihood of quitting smoking based on the recommendations of each message using three items (Bruner, 2009). One item included, “Based on the message you just saw, how likely are you to quit tobacco smoking?” Responses were anchored by 1 = unlikely to 7 = likely. Each participant had one intention to quit score per ad. The three intentions to quit scores for each message condition were then averaged together.

Cognitive Effort

Cardiac deceleration over time has been shown to be a valid and reliable indicator of cognitive resources allocated to encoding media messages (Lang, 1994), whereas reduced cardiac deceleration (i.e., acceleration) is an indicator of reduced resource allocation (Bartholow & Bolls, 2013; Potter & Bolls, 2012). Heart rate was recorded for a 5-second black-screen baseline period prior to the onset of each anti-tobacco advertisement. The signal was obtained by utilizing a Lead I placement of two 8 mm Ag/AgCl disposable electrodes on the left and right forearms with a ground electrode placed on the left wrist. The signal was amplified using a gain setting of 5 K, a low pass filter was set to 35 Hz, and the high pass filter was set to 1 Hz. The signal was sampled at 5000 Hz. Heart rate was converted from milliseconds (ms) between R-spikes in the QRS complex to beats per minute (bpm) by averaging over each second of message exposure.

Recognition

Twenty-four 2-second audio clips derived from the anti-tobacco advertisements shown in the experiment were randomized with 24 two-second audio clips taken from other anti-tobacco advertisements not shown in the study. One audio clip came from each half of each message, but after the first 5-seconds of each message and before the last 5-seconds (Leshner et al., 2011). Participants were asked to indicate whether they believed they had heard the designated audio clip during one of the previously watched advertisements.

Signal Detection Analysis

Two signal-detection parameters of recognition performance were computed: sensitivity and criterion bias (Shapiro, 1994). Sensitivity (A′) is computed as the ratio of hits to false alarms and is advantageous to relying solely on accuracy as it indicates how well participants distinguish between old and new information (Clayton & Leshner, 2015; MacMillan & Creelman, 2004; Murdock & Dufty, 1972). Criterion bias (B″) measures how willing and confident participants are to say “yes” when presented with an item that was previously heard (Shapiro, 1994). Conservative (higher absolute value) criterion bias indicates less confidence for saying something is familiar (i.e., higher threshold for saying something is familiar/less willing to guess) and hence less encoding of the message. In this case there will be fewer false alarms and fewer hits. In contrast, a liberal (lower absolute value) indicates greater confidence for identifying familiar content (i.e., lower threshold for saying something is familiar/more willing to guess) and hence better encoding of the message (Shapiro, 1994). In this case there will be more hits but there will also be more false alarms (MacMillan & Creelman, 2004).

Results

Induction Check

Disgust

As a check of the manipulation for the induction of disgust, smokers indicated how much disgust each message made them feel (Nabi, 2002). Smokers rated HD advertisements as eliciting higher disgust compared to LD advertisements, F(1, 49) = 350.66, p < .001, η2 = .877; MHD = 5.98, SD = 1.31; MLD = 2.52, SD = .93), thereby reassuring there was in fact variance in disgust responses.

Manipulation Check

Nicotine Dependence, Abstinence, and Withdrawal

The average FTND score was 5.70 (SD = 1.64, Range = 4.0–9.0), reflecting medium to high nicotine dependence (Heatherton et al., 1991). On average, participants reported having last smoked 13.9 hours (SD = 3.73, Range = 10.0–25.0) prior to the session and had low CO levels (M = 4.12, SD = 3.53, Range = 1.0–10.0). The mean score on the MNWS was M = 3.02 (SD = 0.55, Range = 3.0–3.83).

Message Ratings

Craving reports were submitted to a 2 (smoking cues) × 2 (disgust) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results (Figure 1, left panel) indicated a significant interaction between smoking cues and disgust, F(1, 49) = 4.11, p = .046, η2 = .057, such that SC+/LD advertisements elicited the greatest craving (M = 5.52, SD = 1.15), followed by SC+/HD advertisements (M = 5.02, SD = 1.00), then SC−/LD advertisements (M = 2.58, SD = 0.98), and finally SC−/HD advertisements (M = 2.48, SD = 1.16). A Bonferroni post-hoc test revealed that both SC+ message conditions were significantly different on craving, F(1, 49) = 4.13, p = .047, η2 = .077), such that SC +/LD ads resulted in greater craving than the next lowest message condition (i.e., SC+/HD ads). H1 was supported. The repeated-measures ANOVA also revealed a significant main effect for smoking cues on craving, F(1, 49) = 192.71, p < .001, η2 = .857, such that SC+ messages elicited greater urge (M = 5.52, SD = 1.07) than SC− messages (M = 2.53, SD = 1.07). There was also a significant main effect for disgust, F(1, 49) = 6.37, p = .015, η2 = .084, such that HD messages elicited lower craving (M = 3.73, SD = 1.08) compared to LD messages (M = 4.05, SD = 1.06).

Fig. 1.

Output for self-report smoking behaviors. SC−/LD = absent smoking cues/low disgust ads, SC−/HD = absent smoking cues/high disgust ads, SC+/LD = present smoking cues/low disgust ads, SC+/HD = present smoking cues/high disgust ads. All messages were 30 seconds in duration.

A parallel analysis of intentions to quit ratings revealed a significant interaction between smoking cues and disgust, F(1, 49) = 4.17, p = .042, η2 = .16, such that SC−/HD advertisements elicited the greatest intentions to quit smoking (M = 4.70, SD = 1.23), followed by SC+/HD advertisements (M = 4.05, SD = 1.29), then SC−/LD advertisements (M = 2.81, SD = 1.46), and finally SC+/LD advertisements (M = 2.73, SD = 1.19). See Figure 1, right panel. A Bonferroni post-hoc test revealed that both high disgust message conditions were significantly different on intentions to quit ratings, F(1, 49) = 10.96, p = .002, η2 = .182), such that SC−/HD ads resulted in greater quit intentions than the next lowest message condition (i.e., SC+/HD ads). H2 was supported. The repeated-measures ANOVA also revealed a significant main effect for smoking cues, F(1, 49) = 6.73, p = .012, η2 = .172, such that SC− messages elicited greater intentions to quit (M = 3.76, SD = 1.34) than SC+ messages (M = 3.38, SD = 1.24). There was also a significant main effect for disgust, F(1, 49) = 60.13, p < .001, η2 = .663, such that HD messages elicited greater intentions to quit (M = 4.37, SD = 1.26) than LD messages (M = 2.77, SD = 1.32).

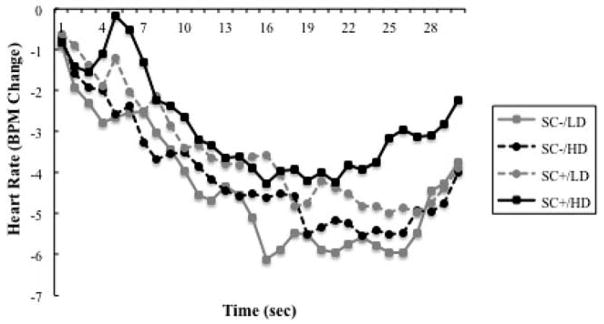

Message Processing

With heart rate measured as change from baseline (BPM during each second of message exposure minus the value of the last second of the 5-second baseline data), a 2 (smoking cues) × 2 (disgust) × 3 (ads) × 30 (time) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted. Results indicated a significant smoking cues × disgust × time interaction, F(29, 1421) = 2.50, p = .003, η2 = .034. As Figure 2 shows, heart rate decelerated less over time for SC+/HD messages compared to the three other message conditions. H3 was supported. This finding suggests participants withdrew from processing SC+/HD messages relative to the other message conditions. There was not a main effect for smoking cues or disgust.

Fig. 2.

Heart rate by time for smoking cues and disgust.

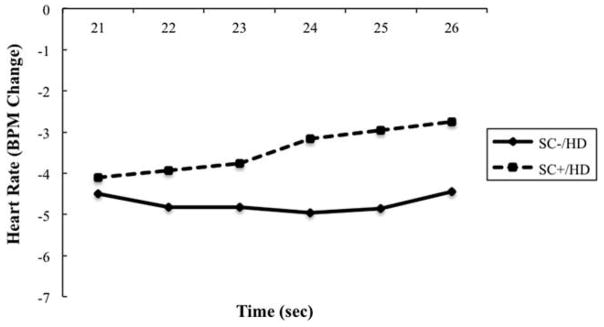

A phasic analysis focused more specifically on the cognitive effects coinciding with the introduction of disgust images. We were interested in examining when heart rate for SC+ messages diverged as a function of the onset of disgust images. To be included in the phasic analysis the disgust content had to appear between the 21-and 26-second marks of the advertisement without any further depictions of smoking cues. Two SC−/HD advertisements and two SC +/HD advertisements were used for the purpose of this analysis since one SC+/HD message depicted smoking cues prior and post disgust images. Change scores were computed from the heart rate data calculated at the 20th second for each message selected for this analysis. A repeated-measures ANOVA using HR data collected between seconds 21–26 revealed a significant disgust × time interaction, F(5, 245) = 2.84, p = .043, η2 = .156). As Figure 3 shows, heart rate for the SC+ condition accelerated shortly after the onset of disgust, whereas heart rate decelerated shortly after the onset of disgust in the SC− message condition.

Fig. 3.

Heart rate by time for disgust as a function of smoking cues.

Message Recognition

Accuracy of message content (% of targets correctly identified) were submitted to a 2 (smoking cues) × 2 (disgust) repeated-measures ANOVA, revealing a significant smoking cues × disgust interaction, F(1, 49) = 6.52, p = .014, η2 = .33. As Table 1 shows, recognition accuracy was significantly worse for SC+/HD messages compared to the three other message conditions. H4 was supported. The repeated-measures ANOVA also revealed a significant main effect for smoking cues on recognition accuracy, F(1, 49) = 9.83, p = .003, η2 = .266, such that SC− messages were recognized better (M = 88%, SD = 0.015) than SC+ messages (M = 81%, SD = 0.020). There was also a significant main effect for disgust on recognition accuracy, F(1, 49) = 24.20, p < .001, η2 = .399, such that LD messages were recognized better (M = 91%, SD = 0.013) than HD messages (M = 78%, SD = 0.023). Provided with the heart rate patterns (Figures 2 and 3), the researchers analyzed recognition accuracy for the second half (seconds 16–30) of SC+/HD and SC−/HD ads. As expected, recognition accuracy for the second half of SC+/HD messages was significantly worse (M = .63%, SD = .38) than the second half of SC−/HD messages (M = .91%, SD = .16); F(1, 49) = 27.18, p < .001, η2 = .381). These data further support H3.

Table 1.

Accuracy, sensitivity, and criterion bias for audio recognition memory data as a function of smoking cues and disgust content.

| SC−/LD | SC−/HD | SC+/LD | SC+/HD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (%) | 91% (.13)a | 85% (.20)a | 91% (.20)a | 70% (.26)b |

| Sensitivity (A′) | .94 (.13)a | .92 (.06)a | .98 (.16)a | .72 (.21)b |

| Criterion Bias (B″) | −.06 (.60)a | −.14 (.63)a | −.15 (.66)a | .37 (.62)b |

Note: Means which do not share a superscript differ significantly from one another (p < .05) across rows. Planned comparisons were computed using Bonferroni post-hoc tests.

Each signal-detection parameter was tested with a 2 (smoking cues) × 2 (disgust) repeated-measures ANOVA. A significant interaction on sensitivity (A′) was found, F(1, 49) = 27.51, p < .001, η2 =.337. As Table 1 shows, A′ was significantly lower for SC+/HD advertisements compared to three other message conditions. There was also a significant main effect for smoking cues on A′, F(1, 49) = 15.27, p < .001, η2 = .263, such that smokers were more sensitive to SC− messages (M = 0.93, SD = 0.011) than SC+ messages (M = 0.85, SD = 0.019). A significant main effect for disgust on A′ was also observed, F(1, 49) = 41.38, p < .001, η2 = .398. Smokers were more sensitive to LD messages (M = 0.96, SD = 0.015) than HD messages (M = 0.82, SD = 0.017). A significant interaction on criterion bias (B″), F(1,49) = 7.95, p = .007, η2 = .472, indicated that smokers were more conservative for SC+/HD advertisements, but more liberal for the three other message conditions. There was also a main effect for smoking cues on B″, F(1, 49) = 7.83, p = .007, η2 = .254, such that smokers were more liberal for SC− messages (M = −0.10, SD = 0.069) than SC+ messages (M = 0.11, SD = 0.049). A significant main effect for disgust on B″, F(1, 49) = 7.57, p = .008, η2 = .273, indicated that smokers were more liberal for LD messages (M = −0.10, SD = 0.056) than HD messages (M = 0.11, SD = 0.065). These data further support H3 and H4.

Discussion

This study examined how nicotine deprived smokers respond to anti-tobacco advertisements that vary in depictions of smoking cues and disgust images. The LC4MP (Lang, 2006) proposes that activation of appetitive and aversive motivational systems influence how we encode, store, and retrieve message content. The self-report findings build upon the cue-reactivity literature and prior anti-tobacco research operating from the LC4MP indicating that smoking cues activate the appetitive motivational system (eliciting smoking urges) thereby producing a boomerang effect and countering the persuasive impact of the message, whereas disgust images in anti-tobacco ads activate the aversive motivational system (evoking feelings of disgust and quit intentions).

In further support of the LC4MP, analyses of the heart rate data indicated that participants allocated the greatest amount of cognitive resources when a message depicted either smoking cues or disgust, or neither was depicted. Thus, although smoking cues promoted message processing, SC+/LD ads created a boomerang effect by eliciting smoking urges and reducing quit intentions, whereas SC−/HD ads promoted message processing but reduced smoking urges and increased quit intentions. These data suggest that in order to counter nicotine-deprived smokers craving or prolong their abstinence, anti-tobacco campaigns should likely omit smoking cues but include disgust content. Furthermore, the combination of smoking cues and disgust in a single message uniquely affected message-processing outcomes. Compared to three other message conditions, SC+/HD messages evoked cardiac acceleration over time indicative of reduced message encoding and defensive processing (Cacioppo et al., 1999). The phasic analysis (Figure 3) and the memory data specifically indicated that smokers reduced resource allocation once disgust images appeared in smoking cue messages, whereas SC−/HD messages did not lead to processing patterns indicative of the defensive cascade. These data suggest that it is the combination of depicting smoking cues with disgust images that led to defensive processing.

Cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957) provides one theoretical explanation as to why defensive processing occurred when messages depicted two motivationally eliciting and opposing attributes. According to cognitive dissonance theory, dissonance is aroused when “two cognitions generate mutually incompatible dispositions, such as approach and avoidance tendencies toward the same object” (Jones & Gerard, 1967, p. 191). The combination of appetitive stimuli (smoking cues) with aversive stimuli (disgust images) in our study appeared to generate two seemingly incompatible dispositions (i.e., approach-craving/avoid-quit). When SC+/HD messages (which initially appear as SC+/LD advertisements during the first 20+ seconds) introduced disgust content following smoking cues, an abrupt and sustained cardiac acceleration emerged, indicative of the initial stages of the defensive cascade (Cacioppo et al., 1999). The researchers surmise that participants reduced resources from encoding content in order to alleviate the discomfort of processing motivationally incongruent content (Kessels et al., 2010). Although uncertain, this motivational interpretation appears to be similar to prior research examining smokers’ cognitive processing of dissonant-eliciting anti-tobacco PSAs. Specifically, research has shown alleviation strategies to occur in response to dissonant-eliciting anti-tobacco ads including defensive processing (Kessels et al., 2010), biasing processing of compromising information (Chaiken, 1992), and by refuting message claims (Brown & Locker, 2009). In this study, we found not only defensive processing (i.e., cardiac acceleration) to occur for motivationally incongruent ads (i.e., SC +/HD) but also reduced recognition memory of message content. This finding also supports the LC4MP, which posits that when defensive processing occurs and fewer resources are allocated to encoding message content, recognition memory should suffer (Lang, 2006). Consistent with this prediction, smokers were less accurate in recognizing content for SC+/HD messages (e.g., 70% accuracy), had reduced A′, and a more conservative (B″) compared to messages that either depicted smoking cues, disgust content, or neither.

Limitations

The current findings should be considered concert with study limitations. We asked participants to report the likelihood of quitting smoking using a small parcel of items after each advertisement. These reports might not reflect behavioral intentions per se; instead, they might be interpreted as ratings of message persuasiveness. Much research has indicated that argument strength against smoking has effects on smokers’ cognitive and behavioral outcomes (Lee & Cappella, 2013); however, this message attribute was not considered in this study. The recognition task required participants to identify content from the audio track of the message, but the message attributes under investigation in this study were visual depictions. A visual recognition task would have potentially provided greater insight into the degree of which smoking cue and disgust depictions were encoded into memory. We did not investigate whether individual differences (e.g., sex, nicotine dependence) moderated message processing. Finally, this study employed a within-subjects design due to the amount of power required to detect significant differences between groups for physiological measures (Vasey & Thayer, 1987).

Conclusions

This study provides novel theoretical insights into how certain state characteristics (i.e., nicotine-withdrawal) during message processing of anti-tobacco ads influences cognitive outcomes and smoking intentions. This study also provides practical insights into anti-tobacco message design. First, smoking cue depictions in anti-tobacco ads should likely be discarded altogether, especially since smoking cues create boomerang effects. Second, our study suggests that when there is a switch in emotional trajectories (i.e., positive/smoking cues to negative/disgust), defensive processing may occur. Third, anti-tobacco ads should continue to depict disgusting images but without smoking cues, especially since these ads increased attention and memory, elicited the fewest smoking urges, and increased intentions to quit smoking. Thus, in order to counter nicotine-deprived smokers craving or prolong their abstinence, anti-tobacco campaigns should likely omit smoking cues but continue to include disgust content.

Footnotes

A description of the stimuli is available upon request from the first author.

A list of the disgust, craving, and intention to quit means per message and message condition as well as their Cronbach’s alphas are available upon request from the first author.

ORCID

Russell B. Clayton http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0471-1585

References

- Bartholow BD, Bolls P. Media psychophysiology: The brain. In: Dill K, editor. The Oxford handbook of media psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. p. 474. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin CE. Exploring antismoking ads: Appeals, themes, and consequences. Journal of Health Communication. 2002;7:123–137. doi: 10.1080/10810730290088003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Jacob P, III, Ahijevych K, Jarvis MJ, Hall S, LeHouezec J, … Hurt RD. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4(2) doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Locker E. Defensive responses to an emotive anti-alcohol message. Psychology & Health. 2009;24:517–528. doi: 10.1080/08870440801911130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner GC. Marketing Scales Handbook. 1. Vol. 5. Carbondale, IL: GCBII Productions; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Gardner WL, Berntson GG. The affect system has parallel and integrative processing components: Form follows function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:839–855. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.76.5.839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cappella J, Bindman A, Sanders-Jackson A, Forquer H, Brechman J. Summary of coding: Anti-smoking public service announcements. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Excellence in Cancer Communication Research, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken S. Defensive processing of personally relevant health messages. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18:669–679. doi: 10.1177/0146167292186002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton RB, Leshner G. The uncanny valley: The effects of rotoscope animation on motivational processing of depression drug messages. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2015;59:57–75. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2014.998227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3:7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard JP, Anderson JW. The role of fear in persuasion. Psychology & Marketing. 2004;21:909–926. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, McCauley C, Rozin P. Individual differences in sensitivity to disgust: A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;16:701–713. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90212-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW, Brown KS, Cameron R. Graphic Canadian cigarette warning labels and adverse outcomes: Evidence from Canadian smokers. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1442–1445. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.8.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EE, Gerard H. Foundations of social psychology. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Cappella JN, Strasser AA, Lerman C. The effect of smoking cues in antismoking advertisements on smoking urge and psychophysiological reactions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:254–261. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels LT, Ruiter RA, Jansma BM. Increased attention but more efficient disengagement: Neuroscientific evidence for defensive processing of threatening health information. Health Psychology. 2010;29:346. doi: 10.1037/a0019372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. What can the heart tell us about thinking? In: Lang A, editor. Measuring psychological responses to media messages. II. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 99–111. LEA’s communication series. [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. Using the limited capacity model of motivated mediated message processing to design effective cancer communication messages. Journal of Communication. 2006;56:S57–80. doi: 10.1111/jcom.2006.56.issue-s1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Cappella JN. Distraction effects of smoking cues in antismoking messages: Examining resource allocation to message processing as a function of smoking cues and argument strength. Media Psychology. 2013;16(2):154–176. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2012.755454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Cappella JN, Lerman C, Strasser AA. Smoking cues, argument strength, and perceived effectiveness of antismoking PSAs. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13:282–290. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner G, Bolls P, Wise K. Motivated processing of fear appeal and disgust images in televised anti-tobacco ads. Journal of Media Psychology. 2011;23:77–89. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner G, Clayton RB, Bhanduri M, Bolls P. The impact of anger and disgusting images in anti-tobacco ads on viewers’ message processing. Psychophysiology. 2013;50:s45–45. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection theory: A user’s guide. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Murdock BB, Jr, Dufty PO. Strength theory and recognition memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1972;94:284–290. doi: 10.1037/h0032795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi RL. The theoretical versus the lay meaning of disgust: Implications for emotion research. Cognition and Emotion. 2002;16:695–703. doi: 10.1080/02699930143000437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe DJ. Message properties, mediating states, and manipulation checks: Claims, evidence, and data analysis in experimental persuasive message effects research. Communication Theory. 2003;13:251–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00292.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Potter RF, Bolls PD. Psychophysiological measurement and meaning: Cognitive and emotional processing of media. New York, NY: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug cravings: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenking B, Lang A. Captivated and grossed out: An examination of processing core and sociomoral disgust in entertainment media. Journal of Communication. 2014;3:545–565. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Jackson A, Cappella JN, Linebarger DL, Piotrowski JT, O’Keeffe M, Strasser AA. Visual attention to antismoking PSAs: Smoking cues versus other attention-grabbing features. Human Communication Research. 2011;37:275–292. doi: 10.1111/hcre.2011.37.issue-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MA. Signal detection measures of recognition memory. In: Lang, editor. Measuring psychological responses to media. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1994. pp. 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST. A cognitive model of drug urges and drug-use behavior: Role of automatic and nonautomatic processes. Psychological Review. 1990;97:147–168. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.97.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll BA, Katulak NA, McKee SA. Investigating the factor structure of the Questionnaire on Smoking Urges-Brief (QSU-Brief) Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(7):1231–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasey MW, Thayer JF. The continuing problem of false positives in repeated measures ANOVA in psychophysiology: A multivariate solution. Psychophysiology. 1987;24:479–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1987.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]