SUMMARY

OBJECTIVES

To describe trends and risk factors for tuberculosis (TB) mortality.

DESIGN

We calculated trends, identified patient characteristics associated with TB diagnosis at death or death during TB treatment, and described diagnostic procedures using the United States National TB Surveillance System for 1997–2005.

RESULTS

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected TB patients had an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 4–11 for TB diagnosis at death (foreign-born non-Whites, aOR = 11) and of 3–19 for death during TB treatment vs. non-HIV-infected patients. Odds increased by age. Hispanic males had an aOR of 2 for TB diagnosis at death compared with female non-Hispanics. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) patients had a three times greater aOR of death during treatment than non-MDR patients. American Indians, Black females, residents in long-term care facilities, US-born patients, and non-HIV-infected homeless persons aged 25–44 years each had an aOR of 2 for mortality during treatment; 86% of pulmonary patients diagnosed at death had a chest radiograph, but 34% had no sputum smear or culture reported.

CONCLUSION

During 1997–2005, controlling for age, HIV remained the characteristic with the greatest aOR for TB diagnosis at death or death during TB therapy. Race/ethnicity, country of birth and homelessness further increased the adjusted odds of death. Results show possible missed opportunities for TB diagnosis prior to death.

Keywords: tuberculosis, mortality, HIV

TUBERCULOSIS (TB) remains a potentially deadly disease, especially for those living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Deaths can occur prior to TB diagnosis or during TB treatment.

The most recent publication on TB mortality (diagnosis at death) using the United States National TB Surveillance System (NTSS) was in 1991, before HIV infection was reported in TB case reports.1 Using 1985–1988 NTSS data, the authors found that 5.1% (4373) of TB patients were diagnosed at death. From a multivariate model, the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of being diagnosed with TB at death increased with age (34–54 years, aOR 1.4–1.5; 55–64 years, aOR 2.5; 65–74 years, aOR 4.0; 75–84 years, aOR 6.5; ≥85 years, aOR 11.3), being Black (aOR 1.3) or Hispanic (aOR 1.2), and having miliary, meningeal, or peritoneal TB (aOR 4.7–5.7).

A clinical trial of TB patients enrolled after 2 months of treatment during 1995–1998 found that 7% died during therapy or during the 2-year follow-up; those who died (vs. those who survived) were more likely to have malignancy (aOR 5.3), to be HIV-infected (aOR 3.9), to use alcohol daily (aOR 2.9), to be unemployed (aOR 2.0), and to be older (aOR 1.1).2 Several studies document that HIV-infected TB patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) during TB therapy survive for longer than those not on ART.3–7

The present study describes trends in mortality and characteristics associated with TB diagnosis at death or death during TB therapy. We also describe diagnostic procedures for patients diagnosed at death to assess missed opportunities for prevention.

METHODS

In the NTSS, there are two mortality outcomes associated with TB: 1) TB diagnosis at death; and 2) death during TB treatment. A diagnosis of TB at death is defined as when TB is investigated after a patient dies, or if a live patient on one or less anti-tuberculosis medication died and is subsequently diagnosed with TB disease. If a patient was suspected or diagnosed with TB disease and started on two or more anti-tuberculosis medications, then dies during TB treatment, this is classified as death during TB treatment.

We excluded data from California, which has not reported AIDS (acquired immune-deficiency syndrome) registry match data for TB patients to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since 2004, and data for patients with unknown (as positive or negative) HIV status. In 2004, California reported 123 TB patients with AIDS, i.e., 10% of known TB-HIV patients in the United States. Since 1989, the CDC has recommended that all TB patients be offered HIV testing.8 Reporting of the HIV status of TB patients to the CDC began in 1993, and has increased over time from 54% of patients in 1997 to 71% in 2005 (excluding California; unpublished analyses by Elvin Magee).

We separately analyzed TB diagnoses at death and deaths during TB treatment from the NTSS for 1997–2005,* a period when access to highly active ART (HAART) became available to many persons living with HIV infection. We described trends in mortality data and case-fatality rates (CFR; i.e., deaths divided by TB cases) by race/ethnicity and for TB-HIV. We identified characteristics associated with mortality outcomes by comparing dead vs. alive TB patients. We performed bivariate analyses and then multivariate logistic regression using backwards selection to obtain aORs at the 99% confidence level. The following variables were entered into both multivariate models: age (0–4, 5–14, 25–44, 45–64, 65–74, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, ≥85 years; 15–24 as referent), race/ethnicity (White, Black/African American, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaskan native; Asian as referent), sex (male, female as referent), country of birth (US, foreign-born as referent), HIV infection (HIV-positive, HIV-negative as referent) and multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB; isoniazid and rifampin resistance on initial or final drug susceptibility tests, otherwise as referent). For deaths during treatment, the following additional variables were entered: homelessness (yes within past year, otherwise as referent), injecting drug use (yes within past year, otherwise as referent), non-injecting drug use (yes within past year, otherwise as referent), excess alcohol use (yes within past year, otherwise as referent), incarceration (prison/jail resident at time of diagnosis, otherwise as referent), and long-term care residency (resident at time of diagnosis, otherwise as referent). Interaction was assessed among all variables identified by backwards selection in each model, with significant interaction terms and their components retained.

We described reported diagnostic procedures separately for pulmonary and extra-pulmonary only TB cases diagnosed at death. Similar analyses were then conducted to assess reported diagnostic methods.

US state and local health departments report TB cases to the NTSS under an assurance of confidentiality; this analysis has been cleared by the CDC for public release.

RESULTS

Trends

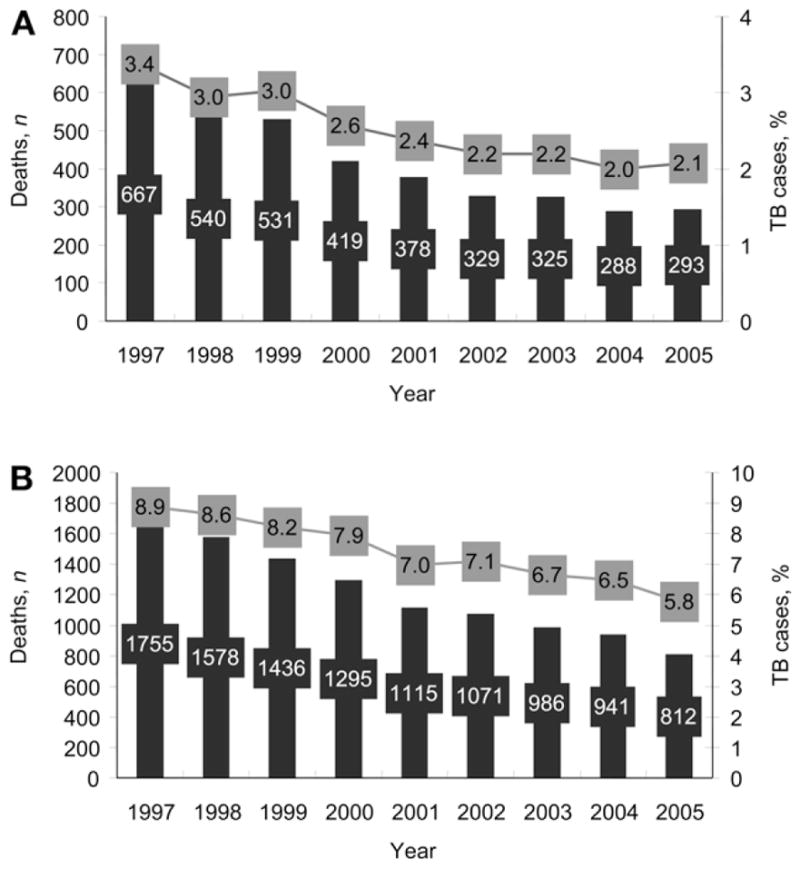

During 1997–2005, among 146 253 US-reported TB cases, 3770 cases were diagnosed at death and 10 989 died during treatment. Mortality declined by 9% annually during 1997–2005, over twice the 4% average annual decline in total TB cases. However, TB diagnosed at death declined by only 1% in 2003 from 2002, and increased in 2005 from 2004.

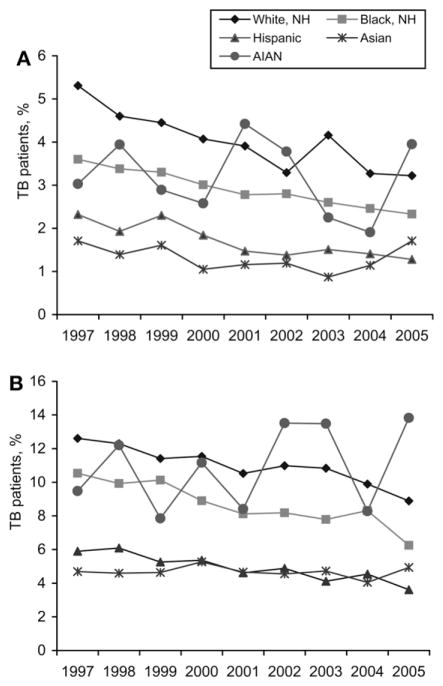

In 2005, as a percentage of total reported TB cases, 2.1% of TB patients were diagnosed at death and 5.8% died during TB treatment (Figure 1). CFRs were highest during 1997–2005 for Whites, followed by Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians (Figure 2). Average annual CFR declines were similar for Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics, at 5–6% for TB diagnoses at death and 4–6% for deaths during TB treatment. For Asians, CFR on diagnosis at death increased in 2004 and 2005, while the CFR for death during TB treatment increased in 2005.

Figure 1.

TB-associated mortality, number and percentage of cases. A. TB diagnosed at death, NTSS, 1997–2005. B. Death during TB treatment, NTSS, 1997–2005. TB = tuberculosis; NTSS = United States National TB Surveillance System.

Figure 2.

A. Case-fatality rates for TB diagnosed at death by race/ethnicity. Rates not shown for native Hawaiians (range 0–4.7, average = 2.7). B. Case-fatality rates for death during TB treatment by race/ethnicity. Rates not shown for native Hawaiians (range 0–9.6, average = 4.8). NH = native Hawaiians; AIAN = American Indian/Alaskan native.

Excluding California and cases with unknown HIV status, HIV-infected patients comprised 49% of diagnoses at death and 38% of deaths during treatment in 1997–2005, declining to respectively 34% and 31% in 2005. Deaths during treatment ranged from 17% of HIV-infected TB patients in 1997 to 13% in 2005. For diagnoses at death, TB-HIV CFRs ranged from 4% in 1997 to 2% in 2005. CFRs for persons with HIV infection declined linearly during 1997–2005, with deaths during treatment falling by 0.4% annually (R2 = 0.52) and diagnoses at death by 0.2% annually (R2 = 0.53).

Characteristics associated with TB mortality in multivariate analyses

After exclusion of California and cases with unknown HIV, 950 cases of TB were diagnosed at death and 4578 died during TB treatment from 1997 to 2005. Mortality outcomes increased with age. For TB diagnosed at death, controlling for age, HIV-infected persons aged 25–44 years, foreign born and non-Whites had the greatest odds (aOR 11.4), followed by age 25–44 years, US-born Whites (aOR 9.5), non-White foreign-born patients aged <25 or ≥45 years (aOR 7.3), White US-born aged <25 or ≥45 years (aOR 6.0), non-White US-born aged 25–44 years (aOR 5.7), and US-born non-Whites aged <25 or ≥45 years (aOR 3.6; Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics associated with tuberculosis diagnosed at death (n = 950)

| Characteristic | n | Adjusted OR (99%CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≥85 years | 36 | 16.2 (8.0–33.2) |

| Age 80–84 years | 38 | 13.1 (6.5–26.4) |

| HIV-infected, age 25–44 years, non-White, foreign-born | 69 | 11.4 (5.6–23.2) |

| Age 75–79 years | 46 | 10.7 (5.4–21.1) |

| Age 70–74 years | 49 | 9.5 (4.8–18.5) |

| HIV-infected, age 25–44 years, White, US-born | 30 | 9.5 (3.2–28.3) |

| HIV-infected, non-age 25–44 years, non-White, foreign-born | 36 | 7.3 (4.7–11.1) |

| Age 65–69 years | 49 | 7.2 (3.7–14.1) |

| HIV-infected, non-age 25–44 years, White, US-born | 24 | 6.0 (2.4–15.4) |

| HIV-infected, age 25–44 years, non-White, US-born | 179 | 5.7 (2.1–15.2) |

| Age 45–64 years | 326 | 4.1 (2.3–7.3) |

| HIV-infected, non-age 25–44 years, non-White, US-born | 118 | 3.6 (1.6–8.1) |

| Hispanic male | 123 | 2.3 (1.1–4.8) |

| Non-Hispanic male | 571 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| Hispanic female | 19 | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

For deaths during TB treatment, HIV-infected persons who were non-homeless and aged 45–64 years had the greatest odds (aOR 18.9), followed by the homeless aged 25–44 years (aOR 8.5), non-homeless aged 25–44 (aOR 7.7), homeless aged <25 or ≥65 years (aOR 3.9), non-homeless aged <25 or ≥45 years (aOR 3.6), and homeless patients aged 45–64 years (aOR 3.0; Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics associated with death during tuberculosis treatment (n = 4578)

| Characteristic | n | Adjusted OR (99%CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≥85 years | 248 | 26.4 (19.2–36.3) |

| HIV-infected, age 45–64 years, non-homeless | 554 | 18.9 (14.1–25.2) |

| Age 80–84 years | 239 | 18.6 (13.5–25.4) |

| Age 75–79 years | 308 | 16.0 (11.9–21.6) |

| Age 70–74 years | 302 | 13.1 (9.7–17.6) |

| Age 65–69 years | 316 | 10.6 (7.9–14.2) |

| HIV-infected, age 25–44 years, homeless | 114 | 8.5 (5.9–12.2) |

| HIV-infected, age 25–44 years, non-homeless | 854 | 7.7 (5.7–10.4) |

| Age 45–64 years, no HIV, non-homeless | 948 | 5.3 (4.1–6.8) |

| HIV-infected, non-age 25–64 years, homeless | 233 | 3.9 (3.1–5.0) |

| HIV-infected, non-age 25–44 years, non-homeless | 679 | 3.6 (3.1–4.1) |

| HIV-infected, age 45–64 years, homeless | 101 | 3.0 (1.9–4.8) |

| MDR-TB | 102 | 2.7 (2.0–3.6) |

| American Indian | 81 | 2.4 (1.7–3.5) |

| Black females | 761 | 2.1 (1.6–2.6) |

| Long-term care residents | 278 | 1.9 (1.5–2.2) |

| US-born | 3645 | 1.8 (1.6–2.0) |

| Homeless, no HIV, age 25–44 years | 55 | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) |

| Non-Black males | 1675 | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) |

| Age 25–44 years, no HIV, non-homeless | 304 | 1.5 (1.2–2) |

| Hispanic | 722 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) |

| White | 1150 | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) |

| Correctional facility resident | 151 | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; MDR-TB = multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

Hispanic males diagnosed with TB at death had an aOR 2.3 times greater than female Asians (Table 1). Patients with MDR-TB had an aOR for death during treatment 2.7 times greater than non-MDR patients (Table 2). American Indians, Black females, residents in long-term care facilities, US-born patients, and non-HIV-infected homeless persons aged 25–44 years each had an aOR of 2 for mortality during treatment. Non-Black males, Hispanics, and Whites had increased aORs (respectively 50%, 50% and 40%) compared with those without these characteristics.

Reported TB diagnostic practices of patients diagnosed with TB at death

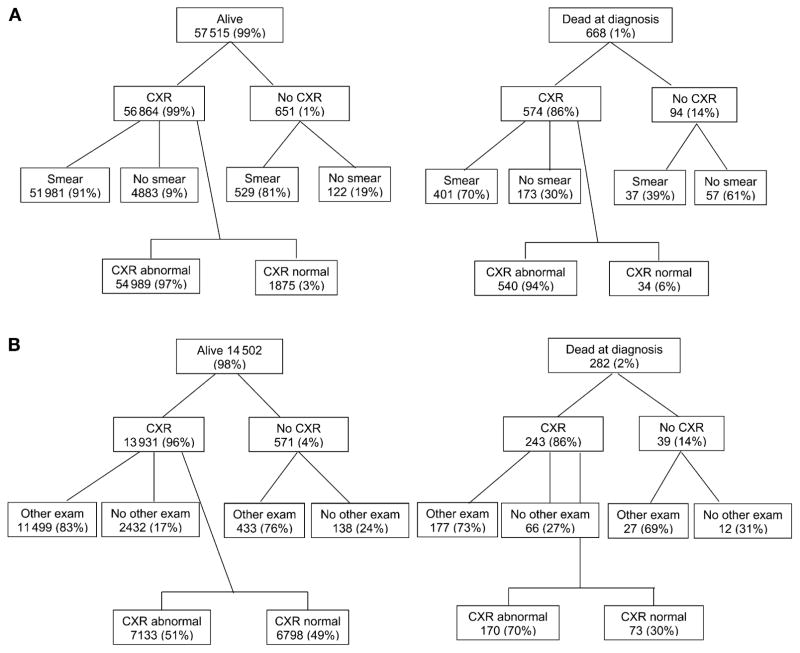

For pulmonary TB patients diagnosed with TB at death (n = 668), 29% (n = 196) reported a tuberculin skin test (TST), compared with 78% of live patients; 86% (n = 574) reported a chest radiograph (CXR), of which 94% (n = 540) were abnormal (Figure 3). Over one third (n = 230, 34%) reported no sputum smear/culture for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), including 173 who had a CXR; 9% (n = 57) reported neither a CXR nor a sputum smear. Reported sputum smears were less likely to be AFB-positive among those diagnosed with TB at death than for live TB patients (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Reported diagnostics of pulmonary and extra-pulmonary TB cases. A. Reported diagnostics of pulmonary TB cases. B. Reported diagnostics of extra-pulmonary TB cases. CXR = chest X-ray; exam = examination; TB = tuberculosis.

For extra-pulmonary only TB patients who were dead at diagnosis (n = 282), 30% (n = 85) reported a TST vs. 76% of those alive; 86% (n = 243) reported a CXR, of which 70% were abnormal (n = 170), and 72% (n = 204) had a specimen other than sputum examined.

The main sites of disease for those dead (vs. alive) at TB diagnosis were pulmonary (69% vs. 78%), pleural (4% vs. 4%), miliary (9% vs. 2%), meningeal (7% vs. 1%), peritoneal (2% vs. 1%) and other (6% vs. 2%). Specimens other than sputum taken from lung, cerebrospinal fluid, blood and feces were more likely to be AFB-positive.

DISCUSSION

TB-associated mortality reflects both the risk of death with undiagnosed TB or during TB treatment and the risk of a diagnosis of TB after death. Patients who are older or have comorbidities such as HIV have a greater overall risk of death, regardless of their TB disease.9,10 However, some proportion of these deaths is caused by TB and might be preventable.

The study findings highlight groups that should be targeted for reducing TB-associated mortality. TB-HIV cases comprised 40–50% of TB mortality from 1997 to 2005. While TB-HIV mortality declined linearly over the period, HIV infection remained the strongest associated factor, controlling for older age. HIV-infected TB patients had an aOR of 4–11 for TB diagnosis at death (foreign-born non-Whites aOR = 11) and of 3–19 for death during TB treatment versus non-HIV-infected patients. In addition to preventing TB and associated mortality through latent TB infection (LTBI) treatment among HIV-infected persons, HAART can reduce TB incidence,11–13 recurrence with disease (i.e., another instance of TB disease following treatment completion) and mortality.3

Other groups disproportionately experiencing TB-associated mortality during 1997–2005 included MDR-TB patients, American Indians, males, Black females, long-term care residents, homeless non-HIV-infected persons, Hispanics and Whites. TB CFRs fell for Whites, Blacks and Hispanics during 1997–2005, indicating progress in reducing mortality relative to TB cases. However, Asian patients (overwhelmingly foreign-born) did not experience declining CFR trends. Delays in TB diagnosis associated with lack of access to care, the severity/toxicity of MDR-TB, and co-morbidities undocumented in the NTSS (e.g., cancer) likely explain some of these disparities.

The risk of a TB diagnosis at death depends on access to care, diagnostic practices and the sensitivity of TB diagnostics. Reported diagnostic practices for patients diagnosed with TB at death suggest that 86% of both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary TB patients entered some health care facility while alive and had a CXR. The patients likely had some evidence of pulmonary disease prior to death for which a CXR was performed (possibly to detect pneumonia, a common and deadly disease). One third of pulmonary patients had no sputum smears/cultures reported, which are generally ordered if the physician suspects TB. For HIV-infected patients during the study period, the CDC recommended both CXRs and sputum examinations (regardless of the CXR result).14 In 2009, the CDC recommended a CXR and sputum smear with culture only for patients with pulmonary symptoms and CXR abnormalities.15 Missing sputum smear reports could be due to: 1) late CXR readings, available after death, resulting in no smear ordered; 2) non-suspicion of TB, and thus no smear ordered; or 3) non-reporting of sputum smear results. For extra-pulmonary only TB cases diagnosed at death, 28% had no result reported other than for sputum. Diagnostic algorithms need to be improved to identify TB disease more rapidly and assess diagnostic reporting.

Lack of TB detection using current diagnostic techniques, which have low sensitivity for immunosuppressed patients, can delay TB diagnosis and care, leading to mortality. Among HIV-infected TB patients, extra-pulmonary disease is more common, and among pulmonary patients the sputum smear is often falsely negative, with only culture showing the Mycobacterium tuberculosis organism. In HIV-infected immunosuppressed persons, CXRs are often normal. One fourth of HIV-infected persons with pulmonary TB disease have false-negative TST or interferon-gamma release assay results, showing that LTBI diagnostic tests cannot be relied upon to exclude TB disease.16 Early knowledge of HIV infection through routine HIV testing of TB suspects and contacts might alert providers to screen for TB disease using all available tools.

Limitations

Because of small numbers, we did not analyze data separately for native Hawaiians. For the TB diagnosis at death analyses, some factors could not be examined for those who died because of significantly more missing data on injecting and non-injecting drug use, excess alcohol use, homelessness, residence in a long-term care facility and residence in a correctional facility. The following patients were more likely to be missing HIV status: those aged ≥65 years, Whites, American Indians, Asians, US-born, long-term care residents and those with extra-pulmonary TB. While some of these patients are known to have lower rates of HIV infection (e.g., ≥65 years, Whites, Asians), others (e.g., US-born, extra-pulmonary cases) have higher rates. The exclusion of US-born and extra-pulmonary cases with unknown HIV status might therefore have resulted in the underestimation of the odds of TB mortality for these patients. Another limitation was that the NTSS did not assess comorbidities other than HIV and did not collect data on HAART use during the study period.

TB as a cause of death is difficult to ascertain and cannot be determined definitively from the NTSS. Autopsies declined from 41% of hospital deaths in 1961 to 5–10% in the mid-1990s in the United States.17,18 In the absence of US autopsy studies, one US study using smears at death and tissue cultures found that 22% of a 1997 TB-HIV cohort died, 44% of which were from TB.7 A random sample (n = 20) record review of the cause of TB-associated deaths during 2000–2004 in California found that 85% (n = 17) were definitely or possibly TB-related and that 60% (n = 12) could have been prevented; death certificate data were often inaccurate in determining the cause of death.19 Reviews of medical records and other data, in the absence of autopsies, could improve the determination of the cause of TB-associated mortalities,19 and improve the completeness of data on excess alcohol use, injecting drug use, non-injecting drug use, homelessness, and residence in a long-term care facility or correctional facility. In 2009, the NTSS began collecting TB as a cause of death and comorbidities (diabetes, immunosuppression, end-stage renal disease). The CDC is currently conducting a national study on TB mortality.

CONCLUSIONS

While TB mortality in HIV-infected persons has declined over time due to reductions in TB incidence and prevalence, the implementation of HAART, and improvements in TB and HIV case management in the United States,20 HIV-infected TB patients still had a 3–19 times higher adjusted odds of TB-associated mortality than non-HIV-infected TB patients. We need to increase routine voluntary HIV testing of TB contacts and TB suspects and provide HAART, routinely screen known HIV-infected persons for TB symptoms, target LTBI and TB testing for populations experiencing mortality disparities, and improve TB diagnostics and diagnostic algorithms to prevent TB-associated mortality.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the US Government; analyses were conducted at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) by CDC employees. No part of the research presented has been funded by tobacco industry sources. None of the authors has a financial conflict of interest or any financial interests related to the material in the manuscript.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the CDC or the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

Footnotes

NTSS dataset as of May 9, 2009.

References

- 1.Rieder HL, Kelly GD, Bloch AB, et al. Tuberculosis diagnosed at death in the United States. Chest. 1991;100:678–681. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.3.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sterling TR, Zhao Z, Khan A, et al. for the TB Trials Consortium. Mortality in a large tuberculosis treatment trial: modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:542–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahid P, Gonzalez LC, Rudoy I, et al. Treatment outcomes of patients with HIV and tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1199–1206. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1529OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akksilp S, Karnkawinpong O, Wattanaamornkiat W, et al. Anti-retroviral therapy during tuberculosis treatment and marked reduction in death rate of HIV-infected patients, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1001–1007. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.061506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manosuthi W, Chottanapand S, Thongyen S, et al. Survival rate and risk factors of mortality among HIV/tuberculosis-co-infected patients with and without antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:42–46. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230521.86964.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dheda K, Lampe FC, Johnson MA, et al. Outcome of HIV-associated TB in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1670–1676. doi: 10.1086/424676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonard MK, Larsen N, Drechsler H, Blumberg H, et al. Increased survival of persons with tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection, 1991–2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1002–1007. doi: 10.1086/339448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection: recommendations of the Advisory Committee for the Elimination of Tuberculosis (ACET) MMWR. 1989;38:236–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nijhuis EW, Nagelkerken L. Age-related changes in immune reactivity: the influence of intrinsic defects and of a changed composition of the CD4+ T cell. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 1992;9:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao VK, Iademarco EP, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. The impact of comorbidity on mortality following in-hospital diagnosis of tuberculosis. Chest. 1998;114:1244–1252. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.5.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones JL, Hanson DL, Dworkin MS, DeCock KM and the Adult/Adolescent Spectrum of HIV Disease Group. HIV-associated tuberculosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. The adult/adolescent spectrum of HIV disease group. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Incidence of tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1772–1782. doi: 10.1086/498315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badri M, Wilson D, Wood R. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on incidence of tuberculosis in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359:2059–2064. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08904-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and treatment of tuberculosis among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: principles of therapy and revised recommendations. MMWR. 1998;47(RR-20):26–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. 2009;58:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menzies D, Pai M, Comstock G. New tests for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: areas of uncertainty and recommendations for research. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:340–354. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. The autopsy, medicine, and mortality statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2001;3:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyert DL, Kung HC, Xu J. Autopsy patterns in 2003. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2006;20:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sprinson J, Bahl M, Benjamin R, et al. TB death assessment tool in California: development and pilot test. TB Notes. 2008:4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munsiff SS, Ahuja SD, Driver CR. Public-private collaboration for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis control in New York City. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:639–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]