SUMMARY

BACKGROUND

Tuberculosis (TB) disproportionately affects the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected, foreign-born, Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, homeless, incarcerated, alcoholic, diabetic or cancer patients, male, those aged >44 years, smokers and poor persons.

METHODS

We present TB knowledge, attitudes and risk perceptions overall and for those experiencing TB disparities from the 2000–2005 US National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).

RESULTS

A total of 32% of respondents said TB is curable; 44% correctly recognized that TB is transmitted by air. Persons with less knowledge about TB transmission were aged 18–24 years, alcohol abusers, educated <12 years, Hispanics or males. Persons less likely to say TB is curable were aged 18–44 years, smokers, HIV-tested, uninsured, alcohol abusers or homeless/incarcerated. Only 28% of foreign-born persons from Mexico/Central America/the Caribbean said TB was curable.

CONCLUSIONS

Knowledge about TB transmission and curability was low among a representative US population. Renewed TB educational efforts are needed for all populations, but should be targeted to populations disproportionately affected, especially those who are HIV-infected, homeless/incarcerated, Black, alcohol abusers, uninsured or born in Mexico/Central America/the Caribbean.

Keywords: tuberculosis, knowledge, attitudes

In the united states, disease due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains a cause of serious morbidity and occasional mortality for approximately 14 000 persons annually. Approximately 11 000 000 persons had latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) in 2000.1 The US public, however, has little knowledge about tuberculosis (TB). From the 1994 US National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), only 33% of respondents correctly recognized that TB transmission occurs through sharing air with an infectious TB patient.2 Accurate knowledge of TB transmission was lowest in groups with the highest risk.

TB disproportionately affects persons who are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected, foreign-born, Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, homeless, incarcerated, alcoholic, diabetic, male or those aged ≥45 years.3 In 2004, HIV-infected persons had estimated rates of 98–112 per 100 000 population compared with a rate of 4.6/100 000 among non-HIV-infected persons, i.e., 21–24 times greater.* In 2005, foreign-born US residents had nearly nine times the TB rate of US-born persons.† Non-Hispanic Blacks (27% foreign-born), Hispanics (75% foreign-born), American Indian/Alaska Natives and Asians (96% foreign-born) had rates that were respectively 8, 7, 5 and 20 times higher than among non-Hispanic Whites.‡ Persons who abused or were dependent on alcohol had nearly twice the TB rate of non-alcoholics.§ Likewise, TB rates were nearly twice as high for males (vs. females) and for those aged ≥45 years (vs. younger persons). ¶ From special studies, TB rates for homeless persons were 5 to 8 times higher than those for nonhomeless persons from 1994 to 2003.* Federal and state prison inmates had four times higher TB rates than non-inmates from 1993–2003.9 From multiple study review, diabetics had an increased TB risk or odds of 1.5–7.8 times that of non-diabetics.10 Cancer patients had greater TB rates (16 times for head/neck cancer patients) than those without cancer.11 Many TB patients belong to several groups for which TB disparities exist. Despite continual declines in TB cases since 1993, these disparities persist (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tuberculosis prevalence rates, various sources, United States, 2005

| Characteristic | Rate per 100 000 population | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| HIV status | ||

| Infected | 98.6–112.2* | 3,4 |

| Non-infected | 4.6 | 3,4 |

| Origin | ||

| Foreign-born | 22.3 | 3 |

| US-born | 2.5 | 3 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 10.9 | 3 |

| Hispanic | 9.4 | 3 |

| Asian | 25.7 | 3 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 12.8 | 3 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 6.8 | 3 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.3 | 3 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 5.8 | 3 |

| Female | 3.4 | 3 |

| Age, years | ||

| ≥45 | 6.4 | 3 |

| <45 | 3.9 | 3 |

| History of excess alcohol use within the past year | ||

| Yes | 9.6 | 5,6 |

| No | 5.0 | 5,6 |

| History of homelessness within the past year | ||

| Yes | 40.1–61.1 | 7,8 |

| No | 7.4–7.5 | 7,8 |

| Residence in a federal/state prison at time of TB diagnosis | ||

| Yes | 24.2–29.4 | 9 |

| No | 6.7 | 9 |

The rate for HIV-infected persons is for 2004, the most recent year of full reporting to the CDC.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; TB = tuberculosis; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The present study describes the TB knowledge, attitudes and risk perceptions of a nationally representative sample of the US public and groups disproportionately affected by TB disease from the 2000–2005 US NHIS.

STUDY POPULATION AND METHODS

The NHIS collects data using annual face-to-face interviews of civilian, non-institutionalized household residents aged ≥18 years, chosen through multistage stratified cluster probability sampling designed to be representative of the US population. The authors obtained and aggregated 6 years (2000–2005) of NHIS data. TB outcomes were derived from the following questions:

Have you ever heard of tuberculosis? (Only those responding ‘yes’ continued)

Have you ever personally known anyone who had TB?

How much do you know about TB? A lot, some, a little or nothing? (Those responding that they knew a lot, some or a little proceeded to questions 4 and 5. Those responding they knew nothing continued to questions 6 and 7.)

How is TB spread?

As far as you know, can TB be cured?

What are your chances of getting TB? Would you say high, medium, low or none? (already have TB)

If you or a member of your family were diagnosed with TB, would you feel ashamed or embarrassed?

Each person in the NHIS sample was selected with a known non-zero probability. Data analysis was conducted on responses weighted for the sampling design, ratio, non-response and post stratification adjustments to census totals for sex, age and race/ethnicity. Associations were assessed with the following socio-economic variables: sex, race/ethnicity, region of birth, age, no high school diploma (i.e., low education), history of homelessness or incarceration, diabetes, ever diagnosed with cancer, being a current cigarette smoker, a lcohol abuse within the past year, lack of health insurance, and ever tested for HIV. Race/ethnicity was defined as White, Black, Hispanic or other, which were consistently reported over time. We assumed that other race/ethnicity includes mostly Asian and American Indian/Alaskan Natives, as they comprise the remainder of the US population (5% and 1%, respectively).†

We used SUDAAN statistical software (Research Triangle Institute, Cary, NC, USA), which adjusts the variance for the complex sampling design to analyze bivariate and multivariate associations between the socio-economic variables and TB outcomes. Separate models for each TB outcome question, plus another for those responding that they already had TB to question 6, were estimated using multivariate logistic regression to identify significant adjusted odds ratios (aORs) of associated characteristics. Only aORs significant at the 99% confidence interval (CI) level are presented. Wherever percentages are mentioned, they are of the weighted sample.

Respondents in the NHIS gave informed consent to participate in the survey. The Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics reviews survey content and procedures to safeguard the rights of study participants. Ethical approval was not required for this study of non-identified data obtained from the NHIS to conduct the current analyses.

RESULTS

There were 190 350 unweighted and 209 560 379 weighted respondents aged ≥18 years from 2000 to 2005. Table 2 presents sample characteristics, unweighted and weighted numbers, and comparison percentages of the US population. Respondents were 73% non-Hispanic White (vs. 69% from US census data for the period), 11% non-Hispanic Black (vs. 12%), 12% Hispanic (vs. 13%) and 4% other (vs. 6%).* By age, 48% were aged ≥45 years (vs. 48%);† 15% (vs. 12% in 2003) were foreign-born;13 17% had a low level of education (vs. 16% in 2003);‡ 20% had a recent history of alcohol abuse; 22% were current smokers; 4% had a history of incarceration or homelessness. One third (33%) had ever been tested for HIV, with nearly half (48%) of non-Hispanic Black respondents (and more Black women [50%] than men [46%]) having been tested.

Table 2.

Characteristics of respondents, NHIS, United States, 2000–2005

| Characteristic | Unweighted (n = 190 350) | Weighted (n = 209 560 379) | Weighted % of the sample | % of the US population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 83 073 | 100 648 754 | 48 | 49 |

| Female | 107 277 | 108 911 626 | 52 | 51 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 124 393 | 152 224 388 | 73 | 69 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 26 281 | 23 709 183 | 11 | 12 |

| Hispanic | 32 766 | 24 456 295 | 12 | 13 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 6 910 | 9 170 513 | 4 | 6 |

| Origin | ||||

| Foreign-born | 32 960 | 31 162 365 | 15 | 12 |

| US-born | 157 390 | 178 398 015 | 85 | 88 |

| Age, years | ||||

| 18–24 | 19 998 | 27 533 296 | 13 | 13 |

| 25–44 | 75 064 | 81 868 329 | 39 | 39 |

| 45–64 | 59 240 | 66 406 320 | 32 | 31 |

| ≥65 | 36 048 | 33 752 434 | 16 | 17 |

| Low education | 37 117 | 35 193 097 | 17 | 16 |

| Current smoker | 41 657 | 45 581 340 | 22 | |

| History of alcohol abuse | 37 001 | 42 577 420 | 20 | |

| History of homelessness, jail or prison | 9 087 | 9 416 539 | 4 | |

| Diabetic | 13 798 | 13 930 686 | 7 | 6 |

| Ever diagnosed with cancer | 13 649 | 14 382 772 | 7 | |

| Ever tested for HIV | 64 643 | 68 559 518 | 33 | 38 |

| No health insurance | 32 279 | 33 129 076 | 16 | 18 |

NHIS = US National Health Interview Survey; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

Table 3 presents significant aORs of selected characteristics and the TB outcomes. Nearly all (87%) respondents had heard about TB (Table 3). HIV-tested persons, homeless or incarcerated persons or those who abused alcohol were 30–40% more likely to have heard about TB. Foreign-born persons, those of other race/ethnicity, those with a low level of education, Hispanics, those aged 18–24 years, persons lacking health insurance, males, Blacks and those aged 25–44 years were from 60% to 20% less likely to have heard about TB.

Table 3.

Tuberculosis outcomes and associated adjusted odds ratios, NHIS, United States, 2000–2005*

| Heard of TB aOR (99%CL) | Knew someone with TB aOR (99%CL) | Had TB aOR (99%CL) | Knew a lot about TB aOR (99%CL) | Knew TB is spread by breathing aOR (99%CL) | Knew TB is curable aOR (99%CL) | Felt at high risk of getting TB aOR (99%CL) | Felt ashamed if had TB aOR (99%CL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted n | 164 452 | 38 743 | 668 | 16 859 | 83 788 | 61 476 | 2 494 | 3 714 |

| Weighted n | 182 474 268 | 41 188 099 | 642 378 | 18 240 634 | 92 573 452 | 66 775 802 | 2 505 881 | 3 998 644 |

| Weighted, % | 87 | 20 | 0.31 | 9 | 44 | 32 | 1 | 2 |

| Male | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | 0.8 (0.8–0.8) | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | Referent | |||||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 2.3 (1.9–2.8) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.6 (0.5–0.6) | 0.8 (0.8–1.0) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | ||||

| Other, non-Hispanic | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) | 1.6 (1.3–1.8) | 2.6 (1.9–3.6) | |||

| Foreign-born | 0.4 (0.4–0.5) | 2.4 (1.7–3.2) | 1.4 (1.2–1.5) | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | |||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) | |||

| 25–44 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) | 0.7 (0.7–0.8) | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | |||

| ≥45 | Referent | |||||||

| Low education | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 2.5 (1.8–3.3) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | |||

| History of homelessness, jail, or prison | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.8 (1.6–1.9) | 2.3 (1.5–3.5) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 2.2 (1.8–2.7) | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | |

| Diabetic | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | |||||||

| Ever diagnosed with cancer | 1.6 (1.4–1.6) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | |||||

| Current smoker | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | ||||||

| History of alcohol abuse | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | ||||

| No health insurance | 0.6 (0.6–0.7) | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | |||||

| Ever tested for HIV | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.2 (1.2–1.2) | 1.8 (1.7–2.0) | 1.2 (1.2–1.3) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 1.7 (1.5–2.0) |

All variables shown in the left-hand column were entered into each multivariate logistic regression model. Each column presents the final model showing aORs for only those variables that remained in the model. All aORs are significant at P < 0.01.

NHIS = US National Health Interview Survey; TB = tuberculosis; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CL = confidence level; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

Nine per cent of respondents stated they knew a lot about TB; HIV-tested persons were 80% more likely than others to say this. Those of other race/ethnicity, foreign-born persons, Blacks, homeless or incarcerated persons and cancer patients were 20–50% more likely than others to state they knew a lot about TB. Persons aged 18–24 years and those with a low level of education were half as likely to say they knew a lot about TB as others. Males, persons aged 25–44 years, persons lacking health insurance, and alcohol abusers were 40–20% less likely to claim they knew a lot about TB than others.

One fifth (20%) of respondents knew someone with TB. Persons with a history of homelessness or incarceration were 80% more likely than others to have known someone with TB. Those who had cancer were 60% more likely, persons of other race/ethnicity were 40% more likely, diabetics were 30% more likely and HIV-tested persons were 20% more likely to have known someone with TB. Persons less likely to have known someone with TB were those in the 18–24 year and 25–44 year age groups, or males.

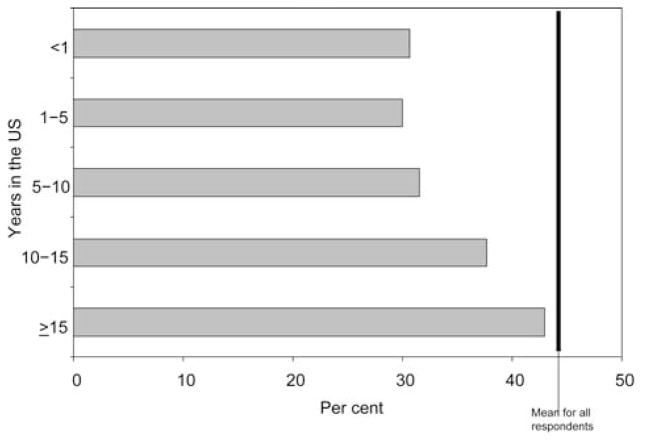

Less than half (44%) of respondents recognized (correctly) that TB is transmitted by breathing air around infectious TB patients. HIV-tested persons or Blacks were 20% more likely than others to mention that TB is spread by air. Those aged 18–24 years were 40% less likely than others to know about airborne TB spread. Alcohol abusers, persons with a low level of education, Hispanics and males were 20–10% less likely to correctly recognize TB transmission by air. Among foreign-born persons, knowledge of TB air transmission was greater for those who had been in the US for ≥15 years (43%) compared with those in the US for <1 year (31%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of foreign-born respondents who mentioned tuberculosis is spread by breathing, by number of years in the United States, NHIS, 2000–2005. NHIS = US National Health Interview Survey.

One per cent of respondents felt at high risk of getting TB or responded that they already had TB. Persons of other race/ethnicity, Blacks, homeless or incarcerated persons and Hispanics were 2.1–2.6 times as likely as others to feel at high risk. HIV-tested persons were 70% more likely and current smokers 40% more likely to feel at high risk of getting TB than others. Males were 20% less likely to feel at high risk of getting TB than females.

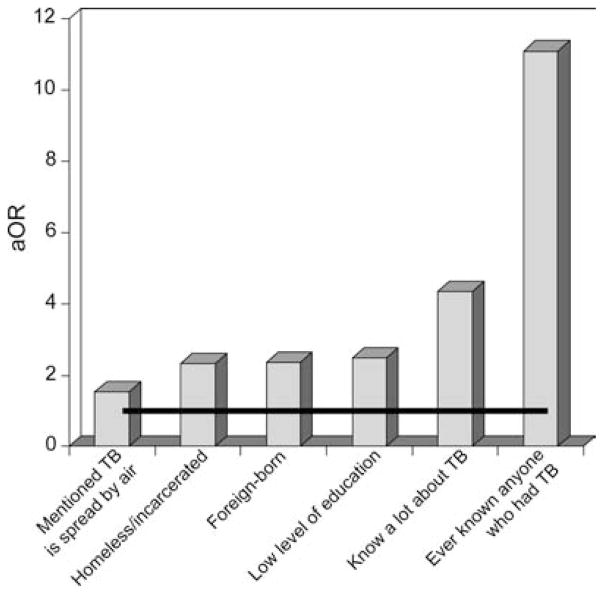

Some respondents (0.31%, or 310/100 000) stated they already had TB. These persons were 11.1 times as likely as others to say they knew someone with TB, 4.3 times as likely to know a lot about TB and 1.6 times as likely to know that TB is spread by sharing air with infectious TB patients (Figure 2). They were also 2.5 times as likely to have low education, 2.4 times as likely to be foreign-born and 2.3 times as likely to have been homeless or incarcerated. History of TB was two times as high among foreign-born (0.55%) than among US-born respondents (0.26%).

Figure 2.

Likelihood of characteristic* among those who had TB† vs. those who had not had TB, NHIS, United States, 2000–2005. TB = tuberculosis; NHIS = US National Health Interview Survey; OR = odds ratio; aOR = adjusted OR. *All aORs significant at the 99% confidence level. †Responded ‘already have TB’ to the question ‘What are your chances of getting TB?’

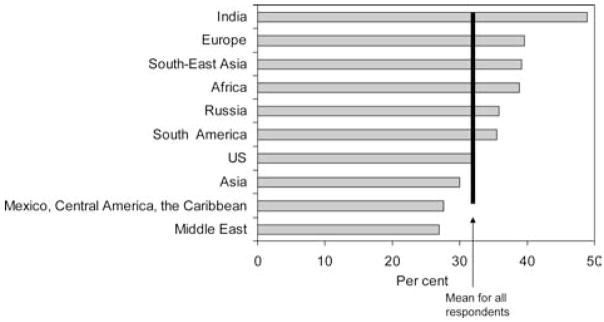

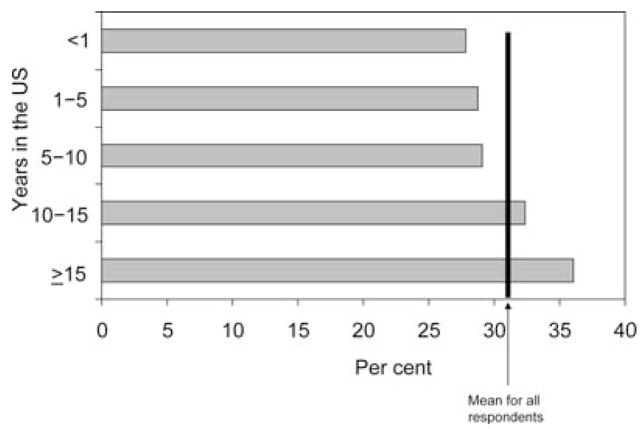

About one third (32%) of respondents said TB is curable (Table 3). Foreign-born persons were 90% more likely, persons of other race/ethnicity 60% more likely, and cancer patients, Hispanics and Blacks 30% more likely to say that TB is curable. Persons less likely to say TB is curable were persons aged 18–44 years, smokers, HIV-tested persons, persons lacking health insurance, alcohol abusers, or homeless or incarcerated persons. Among foreign-born persons, a high percentage (49%) of those from the Indian subcontinent knew TB is curable (Figure 3). Lower percentages of those from Mexico/Central America/the Caribbean (28%) or from the Middle East (27%) stated TB is curable. Also among foreign-born persons, knowledge of TB being curable was 8% greater for those in the US ≥15 years (36%) vs. those who had been in the US for <1 year (28%) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Percentage of persons who knew tuberculosis can be cured, by region of birth, NHIS, United States, 2000–2005. NHIS = US National Health Interview Survey.

Figure 4.

Percentage of foreign-born respondents who knew tuberculosis can be cured, by number of years in the United States, NHIS, 2000–2005. NHIS = US National Health Interview Survey.

Two per cent of respondents would feel ashamed or embarrassed if they or a family member had TB (Table 3). Homeless or incarcerated persons were 2.2 times as likely to feel ashamed as others (4.2% vs. 1.9%), as were foreign-born persons (1.5 times, 2.2% vs. 1.8%), Blacks (1.5 times, 2.7% vs. 1.8%), those with low education (1.4 times, 2.4% vs. 1.8%) or those aged 25–44 years (1.3 times, 2.2% vs. 1.7%). Males were less likely (or females more likely) than others to feel ashamed if they or others had TB (1.8% vs. 2%). Foreign-born persons from the M iddle East (3.3%), South-East Asia (2.9%), South America (2.7%) and Mexico/Central America/the Caribbean (2.3%) were significantly more likely to mention shame than others.

Limitations

The HIV status of respondents was not surveyed— only whether the respondent had been tested for HIV. While the HIV-tested group likely included many with HIV risk behaviors and some who were HIV-infected, it might also have included many who neither had risk behaviors nor were HIV-infected. However, those at increased risk for HIV report testing at rates higher than the general population.15 Another limitation is that TB preventive or care-seeking behaviors were not measured; it was thus impossible to correlate knowledge, attitudes or risk perceptions with actual behaviors. While it is unknown whether those responding that they already had TB truly had TB disease or included LTBI, we analyzed knowledge, attitudes and risk perceptions of that group as if they had the disease.

DISCUSSION

Knowledge about TB transmission remained low from 2000 to 2005: less than half (44%) of NHIS respondents recognized correctly that TB is transmitted by breathing air around infectious TB patients. Knowledge of TB curability was also low: only one third knew that TB is curable. This low knowledge of the curability of TB may translate into low levels of care seeking among those with TB symptoms (e.g., why seek treatment if the disease is incurable?), and result in increased transmission or deaths due to late diagnoses. Increasing TB communication and educational efforts to improve knowledge about TB transmission and curability, especially for those most at risk for TB, may prove effective in improving TB outcomes.16

The survey sample included a small group (0.31% of the weighted sample, 310/100 000) who stated they already had TB, including foreign-born respondents at twice the rate as US-born persons. This group was also more likely to include those with low education or a history of homelessness or incarceration. While it is unknown how well TB disease was explained to respondents and whether it may be an under- or overestimate (e.g., if some interpreted LTBI as TB), to our knowledge this might be the only US representative sample of TB prevalence history. This group said they knew a lot about TB and its airborne transmission, suggesting that current health education efforts among TB patients might be successful.

HIV-tested persons were more likely than others to have heard of TB, know someone with TB, feel they know a lot about TB, know correctly that TB is transmitted through shared air and feel at high risk for acquiring TB. This could be because of previous interaction with the health care system and probable receipt of some patient education. For HIV-tested persons, feeling highly susceptible to TB may indicate their willingness to prevent TB and seek TB care.17 However, HIV-tested persons were also less likely to know that TB is curable, which indicates a need for additional education targeting this group.

Homeless or incarcerated persons were not more likely to know about airborne TB transmission and were less likely to know that TB is curable. These results are worrying, as this group stated they already had TB more frequently than others. This group also felt the most shame or embarrassment from TB. Outbreaks of TB occur frequently among the homeless and incarcerated populations; such knowledge and willingness to come forward with symptoms despite embarrassment are needed to identify TB suspects early in these settings to prevent further transmission.

Blacks were less likely to have heard about TB, but also claimed to know a lot about it, which was validated when they mentioned more often than others that TB is spread by breathing and that TB is curable. Blacks also felt at high risk for getting TB and would feel shame or embarrassment if they or family members had TB. Further efforts are needed to improve the awareness of Blacks about TB.

Foreign-born persons were also more likely to feel shame because of TB, but were more likely to say that TB is curable. However, there was considerable variation in responses of foreign-born subjects by region and years in the US, with those in the US for ≥15 years having greater knowledge of airborne TB transmission and its cure than recent arrivals. While Hispanics overall were more likely to say TB is curable, recent foreign-born Hispanic migrants from the Mexico/Central America/Caribbean region, where approximately one third of US foreign-born TB patients originate, were among those least likely to know that TB is curable.

Other high-risk populations likely to be poor, such as those with no health insurance or with a low level of education, also had low TB knowledge and stigmatizing attitudes. They, too, need to be targeted in educational efforts.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found overall low levels of knowledge about airborne TB transmission and the curable nature of TB. Renewed TB educational efforts are needed for all populations, but should be specifically targeted at those populations disproportionately affected, especially persons who are HIV-infected, homeless/incarcerated, Black, alcohol abusers, uninsured or born in Mexico/Central America/the Caribbean.

Addressing disparities in TB knowledge, attitudes and perceptions may help eliminate disparities in TB disease. Further studies should compare TB knowledge/attitudes and health-seeking behaviors with TB disease.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

Footnotes

CDC,3 Table 13, Tuberculosis cases and percentages with HIV test results and with HIV co-infection by age group: United States, 1993–2005; and CDC,4 2003 figures updated to 2004 by 20 000 cases using http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-01-03, to obtain an estimated 1 059 000–1 205 000 persons living with HIV/AIDS in 2004.

CDC,3 Table 5, Tuberculosis cases, percentages and case rates per 100 000 population by origin of birth: United States, 1993–2006.

CDC,3 Table 2, Tuberculosis cases, percentages and case rates per 100 000 population by Hispanic ethnicity and non-Hispanic race: United States, 1993–2006.

CDC,5 Table 34, Tuberculosis cases and percentages by excess alcohol use, age ≥15: reporting areas, 2005; and SAMHSA,6 Table 5, where we applied the number of 2005 TB cases among alcoholics (1789) to the number of persons aged ≥12 years who experienced alcohol abuse or dependence in 2005 (18 658 000) to find a rate of 9.59/100 000 persons, compared with the number of 2005 TB cases among non-alcoholics (11 119) to the number of non-alcohol dependent or abusing persons (224 562 000) for a rate of 4.95/100 000 persons.

CDC,5 Table 16. Tuberculosis case rates per 100 000 population by Hispanic ethnicity and non-Hispanic race, sex, and age group: United States, 2005.

Burt et al.,7 estimate of between 2.3 and 3.5 million homeless persons per year; and Haddad et al.,8 where we applied the reported numbers of homeless (14 043) and non-homeless TB patients (202 028) from 1994 to 2003, divided by denominators of homeless persons (23 000 000–35 000 000) and total population minus homeless estimates (2 711 724 003–2 719 724 003) for the period.

US Census Bureau,12 Table 3, Annual estimates of the population by sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino origin for the United States: 1 April 2000 to 1 July 2006.

US Census Bureau,12 Table 3, Annual estimates of the population by sex, race and Hispanic or Latino origin for the United States: 1 April 2000 to 1 July 2006.

References

- 1.Bennett DE, Courval JM, Onorato I, et al. Prevalence of tuberculosis infection in the US population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:348–355. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-057OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JE, Sumartojo E, Miller B. Only one-third of US adults can correctly identify how tuberculosis is spread. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:607–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2006. Atlanta, GA, USA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. Estimated persons living with HIV/AIDS, 2003. Atlanta, GA, USA: CDC; 2004. [Accessed August 2008]. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/basic.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2005. Atlanta, GA, USA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2004 and 2005. Rockville, MD, USA: SAMHSA; 2008. [Accessed August 2007]. http://www.drugabusestatistics.samhsa.gov/dependence.htm#Data. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burt MR, Aron LY, Lee E. Helping America’s homeless: emergency shelter or affordable housing? Washington DC, USA: Urban Institute Press; 2001. p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haddad MB, Wilson TW, Ijaz K, Marks SM, Moore M. T uberculosis and homelessness in the United States, 1994–2003. JAMA. 2005;293:2762–2766. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.22.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacNeil JR, Lobato MN, Moore M. An unanswered health disparity: tuberculosis among correctional inmates, 1993 through 2003. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1800–1805. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson CR, Critchley JA, Forouhi NG, et al. Diabetes and the risk of tuberculosis: a neglected threat to public health. Chronic Illness. 2007;3:228–245. doi: 10.1177/1742395307081502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feld R, Bodey GP, Groschel D. Mycobacteriosis in patients with malignant disease. Archives Int Med. 1976;136:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the population. Washington DC, USA: US Census Bureau; 2007. [Accessed November 2007]. http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/NC-EST2006/NC-EST2006-03.xls Internet release date May 17, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen LJ. Current population reports, P20–551. Washington DC, USA: US Census Bureau; 2004. The foreign born population in the United States: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Census Bureau. Educational attainment of the population 15 years and over, by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. Washington DC, USA: US Census Bureau; 2003. Internet release date June 29, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Number of persons tested for HIV—United States, 2002. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:1110–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin SJ, Kinmonth AL, Veltman MW, Gillard S, Grant J, Stewart M. Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:595–608. doi: 10.1370/afm.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy DA, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Joshi V. HIV-infected adolescent and adult perceptions of tuberculosis testing, knowledge and medication adherence in the USA. AIDS Care. 2000;12:59–63. doi: 10.1080/09540120047477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]