Abstract

Importance

Investigation of the conversion rates from normal cognition (NC) to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is important, as effective early intervention could potentially prevent or substantially delay the onset of dementia. However, reported conversion rates differ across studies and recruitment source.

Objective

Our study examined predictors of conversion from NC to MCI in a racially and ethnically diverse sample drawn both from community and clinic recruitment sources.

Design

Rates and predictors of conversion were assessed in an ongoing prospective longitudinal study at University of California, Davis, Alzheimer’s Disease Center from 2000 to 2015.

Setting

Participants were recruited through a clinic (5%) and community sample (95%).

Participants

Participants (n = 254) were clinically confirmed as cognitively normal at baseline and followed up to seven years.

Exposures

Recruitment source, demographic factors (age, gender, race/ethnicity, year of education, APOE ε4 positive), cognitive measures (SENAS test scores), functional assessments (CDR sum of boxes), and neuroimaging measures (total brain volume, total hippocampal volume, white hyperintensity volume).

Main outcome measure

Conversion from cognitively normal to mild cognitive impairment.

Results

Of 254 participants, 62 (11 clinic, 51 community) progressed to MCI. The clinic-based sample showed an annual conversion rate of 30% (95% CI 17–54%) per person-year, whereas the community-based sample showed a conversion rate of 5% (95% CI 3–6%) per person-year. Risk factors for conversion include clinic based recruitment, being older, lower executive function and worse functional assessment at baseline, and smaller total brain volume.

Conclusion and Relevance

Older adults who sought out a clinical evaluation, even when they are found to have normal cognition, have increased risk of subsequent development of MCI. Results are consistent with other studies showing subjective cognitive complaints are a risk for future cognitive impairment, but extend such findings to show that those who seek evaluation for their complaints are at particularly high risk. Moreover, these individuals have subtle, but significant differences in functional and cognitive abilities that, in the presence of concerns and evidence of atrophy on by brain imaging, warrant continued clinical follow-up. These risk factors could also be used as stratification variables for dementia prevention clinical trial design.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is common among older adults, the prevalence ranging from 18% to 36%1. MCI often represents the earliest form of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), with most estimates ranging from 10–15% per year2. Thus, a majority of older adults with MCI develop dementia within five years3. The burden of AD on society, family, and the individual will become increasingly heavy as the number of AD cases increases4.

Investigation of the conversion rates from normal cognition (NC) to MCI is important, not only because of its contribution to the overall mechanism of AD, but also because MCI itself poses challenges to the patient and family. In addition, disappointing results from clinical trials in early AD and MCI have prompted speculation that much earlier intervention would be necessary to prevent or substantially delay dementia onset5.

While there has been considerable research investigating particular risk factors for progression from MCI to dementia, relatively less work has yet addressed predictors of incident MCI in cognitively intact individuals. Regarding genetic contributions, the APOE 4 allele is well recognized as a risk for AD while the E2 allele may decrease risk in transition from NC to MCI6, 7. There is also intense interest in identifying biomarkers that would serve as very early indicators of AD, prior to expression of any clinical symptoms. Mounting evidence suggests that a substantial percent of NC older adults harbor evidence of AD pathology (e.g., amyloid plaques)5,8. There is also evidence that atrophy in brain regions typically impacted by AD (e.g., medial temporal lobe) in CN older adults has been associated with greater risk for disease progression9.

A number of studies have examined the degree to which subtle cognitive changes predict a later diagnosis of MCI. In particular, lower (but not ‘impaired’) performance on tests of verbal learning and recall6,10 and verbal expression10 have been shown to predict decline from NC to MCI. Finally, while changes in everyday function have traditionally been thought of as late occurring manifestations of AD, a growing body of literature demonstrates that mild changes in everyday function are commonly observed in MCI11,12. More recent studies have shown that very subtle changes in complex everyday functional tasks can also be observed in cognitively normal older adults who later go on to develop MCI13,14.

Only a few studies have simultaneously examined the contribution of different classes of variables in predicting progression from NC to MCI or dementia. Both neuropsychological measures and brain atrophy independently predict conversion from normal to MCI15. In another study, both memory and APOE2 carrier status were predictors of time to conversion to MCI6. In sum, early studies suggest that there are likely a variety of predictors of early disease progression.

Rate of disease progression can also be a function of the study sample. For example, we have previously shown that annual conversion rates from MCI to dementia varied as a function of how participants were recruited16. Specifically, individuals recruited from clinical settings (i.e., they had undergone a clinical evaluation and then referred for research) have a higher rate of developing dementia over the following several years than those recruited directly from the community16. Such findings suggest that the act of seeking a clinical evaluation because of concern about cognitive decline, even when found to be cognitively normal, may also increase the likelihood of eventual development of clear cognitive impairment.

The current study longitudinally examined the contribution of genetic, clinical (cognitive, functional changes) and biomarker variables in predicting risk of incident MCI in a demographically diverse cohort of older adults that were followed for an average of 4.5 years. We hypothesized that individuals who were recruited from the community would have a lower risk of developing MCI than those who were clinically recruited. Other variables of interest included: demographic factors, genetic status, cognitive function, independent function, and neuroimaging measures.

Methods

Participants

Participants were a part of the University of California, Davis, Alzheimer’s Disease Center (ADC) Longitudinal Cohort. Participants were recruited through clinical and community routes. Clinical cases had originally been referred (by health care provider or family member) for evaluation of suspected cognitive decline through a memory clinic and subsequently were invited to enroll in the ADC longitudinal cohort. They entered the longitudinal cohort as volunteer NC control subjects. The community outreach program was designed to maximize demographic and cognitive diversity17. Bicultural (and bilingual) recruiters approached elderly persons in community recruitment settings designed to be inclusive of individuals with all forms of cognitive ability (e.g., community health care facilities).

Diagnostic evaluation

All participants received annual multidisciplinary diagnostic evaluations (physical and neurological exam, imaging, lab work, and neuropsychological testing from the Alzheimer’s Disease Uniform Dataset Neuropsychological Battery18) at study baseline and at yearly follow-up visits; diagnostic syndromes are categorized as NC, MCI, or dementia. To be included in the current study, baseline diagnosis had to be NC. Participants with MCI at follow-up were diagnosed according to standard clinical criteria according to current Alzheimer’s Disease Centers Uniform Data Set guidelines19. Importantly, none of the predictor variables were used in making a diagnosis. All participants signed informed consent, and all human subject involvement was approved by institutional review boards at University of California at Davis, the Department of Veterans Affairs Northern California Health Care System and San Joaquin General Hospital in Stockton, California.

Genetic Status

APOE genotyping was conducted using the LightCycler ApoE mutation detection kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).

Image Analysis

Analysis of brain and WMH volumes was based on a Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) sequence designed to enhance WMH segmentation20. Images were orientated parallel to a hypothetical line connecting the Anterior Commissure (AP) and Posterior Commissure (PC). Brain and WMH segmentation was performed in a two-step process according to previously reported methods21,22. In brief, non-brain elements were manually removed from the image by operator guided tracing of the dura matter within the cranial vault including the middle cranial fossa, but excluding the posterior fossa and cerebellum. The resulting measure of the cranial vault was defined as the total cranial volume (TCV) and was used to correct for differences in head size amongst the subjects. Image intensity nonuniformities23 were then removed from the image and the resulting corrected image was modeled as a mixture of two Gaussian probability functions with the segmentation threshold determined at the minimum probability between these two distributions24. Once brain matter segmentation was achieved, a single Gaussian distribution was fitted to the image data and a segmentation threshold for WMH was a priori determined at 3.5 SDs in pixel intensity above the mean of the fitted distribution of brain parenchyma. Morphometric erosion of two exterior image pixels was also applied to the brain matter image before modeling to remove the effects of partial volume CSF pixels and ventricular ependyma on WMH determination. Intra and inter rater reliability for these methods are high and have been published previously 25.

Hippocampal volumes

Boundaries for the hippocampus were manually traced from the coronal 3D-T1 weighted images after reorientation along the axis of the left hippocampus. While the borders were traced on the coronal slices, corresponding sagittal and axial views were simultaneously presented to the operator in separate viewing windows in order to verify hippocampal boundaries. Tracing proceeded according to previously described boundaries which included mostly the anterior portion of the hippocampus26

Neuropsychological assessment

Neuropsychological functioning was assessed using the Spanish English Bilingual Neuropsychological Assessment Scales battery (SENAS)27–29. This study used the episodic memory and executive function composite indices from the SENAS. The Episodic Memory Index is a composite score derived from a multi-trial word list-learning test (Word List Learning I). The Executive Function Index was a composite measure constructed from component tasks of Category Fluency, Phonemic (letter) Fluency, and Working Memory. SENAS development and validation are described in detail elsewhere28.

Everyday Function

The Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) was used as a global measure of independent functioning. The CDR is based on a structured caregiver interview. Scores are obtained in six different functional domains (memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care). The “sum of boxes” score is the arithmetic sum of the six subscores30 was used in the primary analysis.

Statistical methods

Our analytic goal was to compare rates of progression to MCI 1) between clinic and community recruitment sources, 2) across race/ethnic groups and 3) across baseline cognitive, functional, and imaging characteristics to see if these might account for differences in risk of progression. Two-sample t-tests were used for between-group comparisons of continuous demographic and clinical variables, and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Time from study entry to either the last assessment or the assessment at which a diagnosis of MCI was made was considered the time to the event. Four participants went from NC to a diagnosis of dementia (no interim diagnosis of MCI and were not included in the present analysis). Kaplan-Meier curves with conversion to MCI considered as an event were used to illustrate differences in conversion patterns between the recruitment sources. Annualized conversion rates with 95% confidence intervals were estimated using generalized linear models (GLM) with Poisson error, log link, and offset for person-years exposure (time from baseline to censoring or conversion). Cox proportional hazards (PH) models were used to assess risk of incident MCI. The baseline model examined recruitment source as a potential risk factor. Subsequent hazards models included recruitment source and demographics. Finally, the independent effects of all cognitive, imaging, and functional measures were sequentially assessed by one constant survival model with recruitment source as the main exposure of interest and age, year of education, and race/ethnicity adjusted as covariates. To reduce differences in follow-up time and provide a fair comparison between recruitment sources, analyses were restricted to a maximum of 7 years of follow-up. To account for the uncertainty of the timing of the conversion between assessments, a parallel survival analysis using accelerated failure time (AFT) model was also conducted, with time from the last assessment with a non-MCI diagnosis to the assessment at which a diagnosis of MCI was made considered as the interval in which the event occurred. All the Cox and AFT models included baseline age and years of education as covariates. All analysis was performed using R.

Results

This current study included 253 individuals diagnosed as having NC at the baseline assessment and were followed for up to 7 years. A total of 13 participants were recruited through a memory disorders clinic and 241 were recruited through community outreach26 (see Table 1 for demographic and clinical variables). The groups did not differ in age or APOE genotype, but the clinic group included a higher percentage of males, and the community group included a higher percentage of Caucasian male participants with lower level of education. The two groups did not differ significantly on measures of episodic memory or executive function, or on baseline neuroimaging measures of white matter hyperintensity or total brain volume. However, the clinic-recruited participants did show greater total hippocampus volume and worse everyday function on the CDR than the community-recruited participants, even after adjusting for education.

Table 1.

Differences between demographic and clinical variables between the recruitment source groups

| Variable | Recruitment sources | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic (N = 13) | Research (N = 241) | |||

| Demographic | Age, mean (SD) | 73.38 (7.47) | 73.66 (7.03) | 0.900 |

| Education, mean (SD) | 15.69 (3.77) | 12.62 (4.62) | 0.014 | |

| Male, frequency (proportion) | 9 (69.23) | 78 (32.37) | 0.013 | |

| White, frequency (proportion) | 11 (84.62) | 81 (33.61) | 0.0005 | |

| Black, frequency (proportion) | 0(0.00) | 8 (32.37) | ||

| Hispanic, frequency (proportion) | 2 (15.38) | 82 (34.02) | ||

| APOE4 positive (at least one E4 allele) (SD) | 6(46.15) | 70(29.04) | 0.360 | |

| Cognitive | Average episodic memory composite, mean (SD) a | 0.14 (0.80) | 0.09 (0.81) | 0.563 |

| Average executive function composite, mean (SD) a | 0.26 (0.88) | −0.01 (0.61) | 0.439 | |

| Imaging | Log transformed white matter hyperintensity volume, mean (SD) b | −5.36 (1.22) | −5.36 (1.22) | 0.818 |

| Total brain volume, mean (SD) b | 0.77 (0.03) | 0.79 (0.05) | 0.899 | |

| Total hippocampal volume, mean (SD) b | 3.34 (0.79) | 3.28 (0.79) | 0.014 | |

| Functional | Standard CDR sum of boxes, mean (SD) a | 0.83 (1.17) | 0.46 (0.95) | 0.051 |

P values are from linear regression adjusting for year of education.

All these imaging variables were normalized to total intracranial volume, and the value of hippocampal volume was multiplied by 1000.

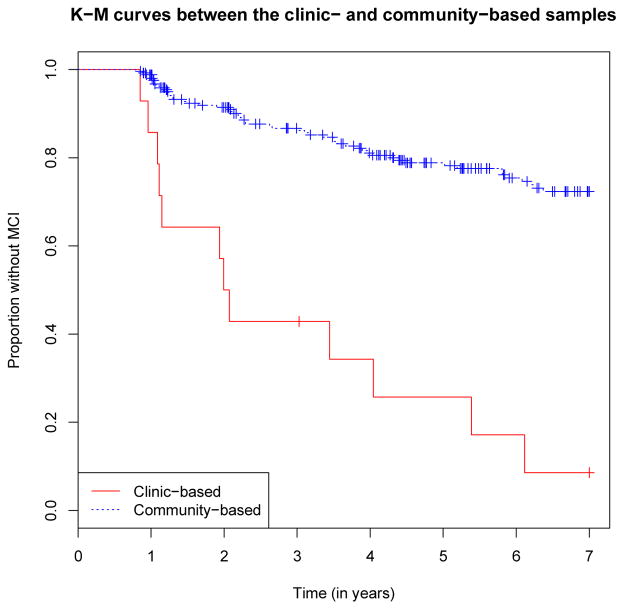

Conversion rates

As shown in Table 2, of the entire sample, 62 participants (11 from the clinic, 51 from the community) progressed to MCI with a mean (SD) time of follow-up of 2.8 years (2.1) for clinical-based sample and 4.6 years (2.3) for the community-based sample. The overall MCI incidence rate was 6% per person-year (95% CI 4–7%). When examined separately, however, the incidence rates were substantially different between the two recruitment sources. The clinic-based sample showed an annual conversion rate of 30% (95% CI 17–54%) per person-year, whereas the community-based sample showed a conversion rate of 5% (95% CI 3–6%) per person-year (Figure 1: p < 0.001, log-rank test). Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards models found clinic-recruited participants were 7 times more likely to convert to MCI compared to the community-recruited participants (HR=6.7, 95% CI: 3.5–12.9).

Table 2.

Annual incidence rates for conversion from NC to MCI

| Recruitment source

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Clinic (N = 13) | Community (N = 241) | |

|

| ||

| Annual conversion rate (95% CI) | 30% (17%, 54%) | 5% (3%, 6%) |

|

| ||

| Years of follow-up, mean (SD) | 2.83 (2.13) | 4.60 (2.29) |

|

| ||

| Number of participants converted | 11 | 51 |

|

| ||

| MCI subtypes | ||

| Amnestic | 5/8 | 17/54 |

| Memory plus another domain | 1/8 | 16/54 |

| Non-amnestic, single domain | 0/8 | 14/54 |

| Non-amnestic, multiple domain | 2/8 | 7/54 |

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves comparing conversion rates from NC to MCI between the clinic- and community-based samples (log-rank test, p-value < 0.001)

Predictors of conversion

A series of models were generated for assessing the predictors. Demographic variables (age, gender, education, race/ethnicity) and genetic status (APOE4) were assessed first. In the Cox PH model, recruitment source remained a significant factor with an increased hazard of conversion for clinic-recruited participants (HR=10.8, 95% CI: 4.5–24.2). Being older (HR=1.1, 95% CI: 1.09–1.2) or Hispanic (HR=2.4, 95% CI: 1.1–5.4) was also associated with higher risk of conversion, independent of recruitment source. Recruitment source and demographic variables were included in all analyses unless otherwise noted.

Second, the clinical measures were evaluated, including the cognitive and functional assessment. In separate models that included each clinical variable, better baseline episodic memory (HR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.3–0.6), better baseline executive function (HR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.6), and higher CDR score (worse everyday function) were associated with greater risk of conversion to MCI (HR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.4–2.1). In a model with all clinical measures, clinic-based recruitment (HR, 12.43; 95% CI, 5.40–28.61) as well as being older (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.07–1.2), having worse baseline executive function (SENAS) (HR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3–0.96) or worse baseline everyday function represented by larger CDR score (HR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3–2.1) were all significantly independently associated with an increased hazard of conversion.

Next, we assessed the independent effect of neuroimaging variables, including log-transformed white matter hyperintensity volume, total brain volume, and total hippocampal volume. In a model with each one of the imaging variables, we found recruitment source remained a significant predictor of conversion. Only total brain volume was independently associated with the hazard of conversion rate (HR=0.991, 95% CI, 0.984–0.998), and none of the other imaging variables helped account for the effect (for WMH, p-value = 0.28; for total hippocampal volume, p-value = 0.10). In a model with all three neuroimaging measures, recruitment source remained an independent risk factor for conversion (HR=21.2, 95% CI, 8.3–54.2), and being Hispanic (HR=3.4, 95% CI, 1.4–8.5), and smaller total brain volume (HR=0.99, 95% CI, 0.98–0.999) were also significantly associated with increased risk of conversion.

Finally, all of the variables that were independently associated with risk of conversion in previous models were added in a joint model, as shown in Table 3. Recruitment source remained a significant predictor (HR=13.5; 95% CI: 5.1–35.4). Besides the recruitment source, older age (HR=1.1, 95% CI: 1.0–1.2), worse baseline executive function (HR=0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.96), smaller total brain volume (HR=0.7, 95% CI: 0.5–0.96), and worse baseline everyday function (HR=1.6, 95% CI: 1.3–2.0) were independently associated with risk of conversion to MCI. Follow-up analyses with AFT models, used to allow for the effect of interval censoring, showed consistent conclusions with the Cox PH models.

Table 3.

All potential predictors for conversion from NC to MCI

| Variables | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Clinic-based sample vs. Community-based sample* | 13.46 (5.12, 35.38) |

| Age* | 1.08 (1.02, 1.15) |

| Year of education | 1.05 (0.97, 1.14) |

| African American vs. White | 1.17 (0.51, 2.69) |

| Hispanic vs. White | 1.89 (0.73, 4.87) |

| APOE4 positive | 1.10 (0.60, 2.04) |

| Average episodic memory composite | 0.70 (0.40, 1.22) |

| Average executive memory composite* | 0.48 (0.25, 0.94) |

| Standardized total brain volume* | 0.66 (0.46, 0.96) |

| Standard CDR sum of boxes* | 1.63 (1.30, 2.04) |

Statistically significant factors with p-value < 0.05

Secondary analysis evaluated the impact of the same variables within the community sample alone. In this case, older age (HR=1.1, 95% CI: 1.0–1.2), worse baseline executive function (HR=0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.9), and poorer baseline everyday function (HR=1.6, 95% CI: 1.3–2.0) were predictive of increased risk for conversion to MCI.

Discussion

This study found a 13-fold greater risk of conversion from NC to MCI in clinically recruited older adults (30% per year) as compared to community recruited older adults (5% per year). This pattern of findings is consistent with our previous study of conversion from MCI to dementia, in which we found a 3.5-fold greater rate of conversion in clinic-recruited participants16. Importantly, this higher conversion rate in the clinic group occurred within the setting of equivalent baseline cognitive test scores among the groups. However, the clinically recruited group did show significantly more functional difficulties at baseline, which was also shown to be an important predictor of conversion. The finding that being concerned enough to seek out a clinical evaluation puts one at risk for the development of cognitive decline in subsequent years is in line with the growing literature on the importance of subjective cognitive complaints as a predictor of subsequent development of cognitive impairment as evident on clinical exam31,32.

There were a number of variables that contributed to risk of conversion, independent of recruitment source. Most notably, greater difficulty in everyday function was associated with an increased risk of conversion. Such findings suggest that there are subtle changes in everyday functioning present even prior to being able to detect clear cognitive impairment that are harbingers of early disease and subsequent cognitive impairment. This is consistent with other studies showing that there are mild functional limitations present in cognitively normal individuals who later go on to be diagnosed with MCI or dementia13,14,33.

Greater cognitive impairment at baseline was another factor that contributed to risk of conversion. Interestingly, it was not poorer memory performance but worse executive functioning at study baseline that was associated with increased risk for the development of MCI. While this finding runs contrary to considerable clinical lore regarding change in memory being the early hallmark of AD, a number of other studies have found executive difficulties to precede memory decline34. Since everyday function has been strongly associated with executive functioning, especially among normal or minimally impaired older adults35, these findings may also be consistent with functional changes being a very early marker of neurodegenerative disease.

Finally, some studies have suggested increased predictive power when you include both biologic markers and clinical variables7, 16. The current study found that brain atrophy provided predictive utility in addition to cognitive and functional measures. In particular, greater degree of total brain atrophy (but not hippocampal atrophy or white matter changes) was associated with increased risk for developing MCI. Such results highlights the benefits of having brain imaging results when presenting diagnostic and prognostic information to patients and their families. The current study did not find that APOE 4, which is a known risk factor for AD, was associated with risk for conversion from normal to MCI when accounting for recruitment sources. Other studies have found it to be a risk for developing MCI 36,37 but not in the context of controlling for the same variables as done in this study.

One study limitation is the modest sample size for clinically-recruited participants. However, additional analysis among only the community recruited participants showed similar predictors of MCI. These findings have considerable clinical relevance. Notably, subjective concern about cognition leading one to seek evaluation, particularly when accompanied by subtle changes in everyday function reported by an informant, should be taken seriously even in the context of otherwise intact cognition. While subjective concerns are often attributed to depression, when we included depression as a covariate in our analysis (data not shown) results remained the same. Additionally, the presence of brain atrophy should be an early indication for risk and therefore should be considered as part of an early clinical work-up.

Systematic Review

Background knowledge in this area was evaluated by literature reviews on topics of subjective cognitive complaints (SCC), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), functional, cognitive and biological contributors to the risk of conversion to MCI or dementia.

Interpretation

Our findings contribute to identification of individuals at risk for conversion to MCI. Specifically, individuals who are seeking a clinical evaluation due to cognitive concerns but who are found to be cognitively normal, have a substantially elevated risk of developing MCI over subsequent years. Additional risk factors for developing MCI include weaknesses in executive function, subtle difficulties in everyday functional abilities, and reduced brain volume on imaging. Findings suggest that concerns about cognitive changes among older adults should be taken serious, even when formal cognitive remains normal, and when present warrants further clinical follow-up.

Future Directions

To confirm these findings, future research should include a larger clinic sample.

Highlights.

Examined rates/predictors of conversion from normal cognition to mild cognitive impairment

The clinic-based sample showed an annual conversion rate of 30% (95% CI 17–54%) per person-year

The community-based sample showed an annual conversion rate of 5% (95% CI 3–6%) per person-year

Risk factors: older, worse baseline executive function/functional ability, small brain volume

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (nia.nih.gov) grants P30AG010129 (DH, SF, DM, CD, LB). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors Disclosure Statement: All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ganguli M, Chang CC, Snitz BE, Saxton JA, Vanderbilt J, Lee CW. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment by multiple classifications: The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT) project. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry: official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010 Aug;18(8):674–683. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cdee4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell AJ, Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia--meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2009 Apr;119(4):252–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Archives of neurology. 1999 Mar;56(3):303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Archives of neurology. 2003 Aug;60(8):1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sperling R, Mormino E, Johnson K. The evolution of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: implications for prevention trials. Neuron. 2014 Nov 5;84(3):608–622. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blacker D, Lee H, Muzikansky A, et al. Neuropsychological measures in normal individuals that predict subsequent cognitive decline. Archives of neurology. 2007 Jun;64(6):862–871. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.6.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brainerd CJ, Reyna VF, Petersen RC, et al. The apolipoprotein E genotype predicts longitudinal transitions to mild cognitive impairment but not to Alzheimer’s dementia: findings from a nationally representative study. Neuropsychology. 2013 Jan;27(1):86–94. doi: 10.1037/a0030855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sperling RA, Dickerson BC, Pihlajamaki M, et al. Functional alterations in memory networks in early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromolecular medicine. 2010 Mar;12(1):27–43. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickerson BC, Stoub TR, Shah RC, et al. Alzheimer-signature MRI biomarker predicts AD dementia in cognitively normal adults. Neurology. 2011 Apr 19;76(16):1395–1402. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oulhaj A, Wilcock GK, Smith AD, de Jager CA. Predicting the time of conversion to MCI in the elderly: role of verbal expression and learning. Neurology. 2009 Nov 3;73(18):1436–1442. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c0665f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedrosa H, De Sa A, Guerreiro M, et al. Functional evaluation distinguishes MCI patients from healthy elderly people--the ADCS/MCI/ADL scale. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2010 Oct;14(8):703–709. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jefferson AL, Byerly LK, Vanderhill S, et al. Characterization of activities of daily living in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry: official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008 May;16(5):375–383. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318162f197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farias ST, Chou E, Harvey DJ, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of everyday function by diagnostic status. Psychology and aging. 2013 Dec;28(4):1070–1075. doi: 10.1037/a0034069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall GA, Zoller AS, Kelly KE, et al. Everyday cognition scale items that best discriminate between and predict progression from clinically normal to mild cognitive impairment. Current Alzheimer research. 2014;11(9):853–861. doi: 10.2174/1567205011666141001120903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui Y, Liu B, Luo S, et al. Identification of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease using multivariate predictors. PloS one. 2011;6(7):e21896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, DeCarli C. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic- vs community-based cohorts. Archives of neurology. 2009 Sep;66(9):1151–1157. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinton L, Carter K, Reed BR, et al. Recruitment of a community-based cohort for research on diversity and risk of dementia. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2010 Jul-Sep;24(3):234–241. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181c1ee01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2009 Apr-Jun;23(2):91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2006 Oct-Dec;20(4):210–216. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jack CR, Jr, O’Brien PC, Rettman DW, et al. FLAIR histogram segmentation for measurement of leukoaraiosis volume. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001 Dec;14(6):668–676. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeCarli C, Maisog J, Murphy DG, Teichberg D, Rapoport SI, Horwitz B. Method for quantification of brain, ventricular, and subarachnoid CSF volumes from MR images. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992 Mar-Apr;16(2):274–284. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199203000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeCarli C, Miller BL, Swan GE, et al. Predictors of brain morphology for the men of the NHLBI twin study. Stroke. 1999;30(3):529–536. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeCarli C, Murphy DG, Teichberg D, Campbell G, Sobering GS. Local histogram correction of MRI spatially dependent image pixel intensity nonuniformity. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1996;6(3):519–528. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880060316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeCarli C, Maisog J, Murphy DG, Teichberg D, Rapoport SI, Horwitz B. Method for quantification of brain, ventricular, and subarachnoid CSF volumes from MR images. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16(2):274–284. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199203000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeCarli C, Massaro J, Harvey D, et al. Measures of brain morphology and infarction in the framingham heart study: establishing what is normal. Neurobiol Aging. 2005 Apr;26(4):491–510. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeCarli C, Reed BR, Jagust W, Martinez O, Ortega M, Mungas D. Brain behavior relationships among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2008 Oct-Dec;22(4):382–391. doi: 10.1097/wad.0b013e318185e7fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mungas D, Reed BR, Marshall SC, Gonzalez HM. Development of psychometrically matched English and Spanish language neuropsychological tests for older persons. Neuropsychology. 2000 Apr;14(2):209–223. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.14.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mungas D, Reed BR, Crane PK, Haan MN, Gonzalez H. Spanish and English Neuropsychological Assessment Scales (SENAS): further development and psychometric characteristics. Psychological assessment. 2004 Dec;16(4):347–359. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mungas D, Reed BR, Haan MN, Gonzalez H. Spanish and English neuropsychological assessment scales: relationship to demographics, language, cognition, and independent function. Neuropsychology. 2005 Jul;19(4):466–475. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daly E, Zaitchik D, Copeland M, Schmahmann J, Gunther J, Albert M. Predicting conversion to Alzheimer disease using standardized clinical information. Archives of neurology. 2000;57:675–680. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell AJ, Beaumont H, Ferguson D, Yadegarfar M, Stubbs B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: meta-analysis. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2014 Dec;130(6):439–451. doi: 10.1111/acps.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendonca MD, Alves L, Bugalho P. From Subjective Cognitive Complaints to Dementia: Who Is at Risk?: A Systematic Review. American journal of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 2015 Jul 3; doi: 10.1177/1533317515592331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau KM, Parikh M, Harvey DJ, Huang CJ, Farias ST. Early Cognitively Based Functional Limitations Predict Loss of Independence in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Older Adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 2015 Oct;21(9):688–698. doi: 10.1017/S1355617715000818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson JK, Lui LY, Yaffe K. Executive function, more than global cognition, predicts functional decline and mortality in elderly women. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2007 Oct;62(10):1134–1141. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitter-Edgecombe M, Parsey C, Cook DJ. Cognitive correlates of functional performance in older adults: comparison of self-report, direct observation, and performance-based measures. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 2011 Sep;17(5):853–864. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Risacher SL, Kim S, Shen L, et al. The role of apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype in early mild cognitive impairment (E-MCI) Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2013;5:11. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts RO, Cha RH, Mielke MM, et al. Risk and protective factors for cognitive impairment in persons aged 85 years and older. Neurology. 2015 May 5;84(18):1854–1861. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]