The current and expected consequences of global change challenge traditional strategies for conserving biodiversity and the ecological patterns and processes that govern such diversity. Conservation efforts traditionally were focused on protecting ecosystems within reserves (e.g., wilderness areas) and restoring degraded lands that were missing key structures, processes, or species that historically characterized ecosystems (e.g., reestablishing ponderosa pine forests and their fire regimes or reintroducing wolves to Yellowstone National Park). However, climate change and other global threats, such as invasive species, cross reserve boundaries and create moving targets for preservation and restoration. This is leading ecologists to rethink traditional conservation strategies (Hobbs et al. 2010).

Protected areas have been established for decades to restrict development and limit human intervention into natural processes. Conservation scientists long held that unmanipulated, autonomous ecosystems within a reserve will maintain their biological diversity (Aplet and Cole 2010). A recent conservation strategy calls for setting aside half of the planet's terrestrial surface in conservation reserves (doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014) and increasing efforts for protecting what is left of undeveloped wild areas (Martin et al. 2016, Watson et al. 2016). Similarly, Aycrigg and colleagues (2016) called for “completing the system” of conservation reserves to better represent biodiversity in an ecologically connected network. Climate change and invasive species, however, are increasingly affecting native species and ecosystems within reserves, leading some ecologists to question the strategy of designating additional wilderness reserves that limit intervention (Kareiva and Marvier 2012). They instead propose aggressive management interventions in places originally set aside to minimize human influence (Hobbs et al. 2010).

Another area in which climate change poses a challenge to traditional conservation strategies involves restoration of degraded lands. Ecologists have begun to reconsider historical targets of restoration (Higgs et al. 2014). Many restoration scientists have traditionally aimed to reestablish the suite of species that occurred in a site before recent human activity altered land cover, eradicated native species, and introduced exotic species. But do historical targets for restoration still make sense in an age when climate change may profoundly alter which species can survive there (Hobbs et al. 2006, Keane et al. 2009)? It makes little sense, critics argue, that we should try to restore historical conditions (i.e., retrospective-based strategies) if the past no longer serves as a guide for maintaining native biodiversity in the future. Rather, some argue, we should plan for the future and use novel management tactics that anticipate projected climate (e.g., prospective-based strategies such as planting genotypes adapted to projected climate in degraded lands).

In response to the challenges and dilemmas that traditional conservation strategies face under climate change, a number of conceptual frameworks have been developed to support climate-intentional conservation decisions (Millar et al. 2007, Cross et al. 2012, Gillson et al. 2013, Schmitz et al. 2015). Some authors have used data to recommend either retrospective or prospective strategies suited to lands on the basis of their existing conditions, the projected climate vulnerability, and risks associated with action or inaction. For instance, researchers have proposed that climate-adaptation strategies be assigned to management areas (e.g., wildlife refuges; Magness et al. 2011) or ecoregions (Watson et al. 2013), depending on their ecological condition (e.g., ecological integrity or topographic variability) and predicted climate (Magness et al. 2011, Gillson et al. 2013, Watson et al. 2013, Hobbs et al. 2014). Given the variability in climate projections among general circulation models (Knutti and Sedláček 2012), the diverse metrics of climate vulnerability (Garcia et al. 2014), and the uncertainty in ecological responses to climate change (Gray 2011), some scientists suggest that climate-adaptation efforts should identify and protect resilient landscapes on the basis of the geophysical diversity and landscape permeability—not on predictions of climate-driven species shifts (Anderson et al. 2012).

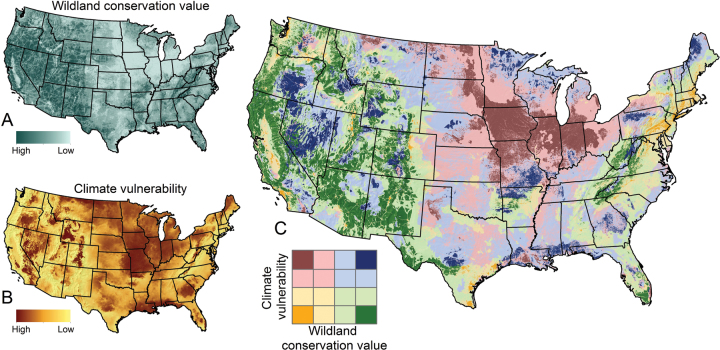

Here, we address these challenges by proposing a conceptual framework for assigning conservation strategies across a network of diverse areas and mapping where different strategies, among a portfolio of approaches, might most appropriately be emphasized (figure 1). We begin by suggesting that the traditional conservation strategies of reducing carbon emissions, protecting ecosystems from nonclimate stressors (e.g., invasive species, resource extraction, and land-cover conversion), establishing an ecologically representative and connected system of reserves, and restoring historical processes or species are all still critical “no-regrets” strategies to pursue (sensu Hallegatte 2009). Recognizing the challenges described above, we believe that an assessment of conservation values and climate vulnerability might help decisionmakers distinguish between alternative options during coarse-scale scenario planning (Gray 2011).

Figure 1.

A national assessment of conservation values (a) and climate-change vulnerability as has been indicated by forward climate velocity (b) to guide conservation strategies (c). The composite map of wildland conservation values was created from mapped indices of ecological integrity, connectivity, and ecosystem and endemic-species representation in protected areas (a). The climate velocity map shows the median multivariate forward velocity among 18 estimates based on nine general circulation models and two relative-concentration pathway scenarios averaged over a 30-year period centered on 2055 (b). We suggest emphasizing diverse conservation strategies based on a simultaneous evaluation of conservation values and climate vulnerability (c).

To demonstrate one example of applying our approach, we combined geospatial data on existing conservation values with a metric of projected climate change to map recommendations across the conterminous United States. First, we scored and mapped existing conservation values on the basis of an estimate of ecological integrity and human-caused stressors (Theobald 2013), the importance of land as a natural corridor between protected areas (Belote et al. 2016), how well ecosystems are already represented within protected areas (Aycrigg et al. 2013), and whether a location is rich in endemic species that are not well protected in conservation reserves (Jenkins et al. 2015). Areas that rate highly in these combined values should receive greater consideration and priority for some form of conservation protection in a national network of ecological reserves (figure 1a; Belote et al. 2017), per the recent recommendations of Aycrigg and colleagues (2016). Adding lands with these qualities may be an important strategy to improve the resilience of conservation reserve systems for the future (Belote et al. 2017).

Next, onto our map of conservation values, we superimposed spatial data on forward climate velocity (figure 1b; Carroll et al. 2015), a measure of climate vulnerability that estimates the geographic distance species may need to travel to keep up with multivariate climate shifts. Combining conservation values and climate vulnerability in this way provides support for decisions that focus on where to emphasize various conservation strategies under a changing climate (figure 1c).

High conservation value, low climate vulnerability (green regions in figure 1c)

Areas with high conservation value and low climate vulnerability may be the best candidate lands for additional conservation reserves where interventions are limited (e.g., wilderness areas that are established to protect untrammeled ecosystems). These places are relatively wild and intact and should be considered conservation priorities (Martin et al. 2016, Watson et al. 2016). They are also important for connecting protected areas, and they are composed of habitat types and range-limited species that are not well represented in existing conservation reserves. The climate in these places may be relatively stable (climate velocity is low), and reserves may serve as important refugia for plants and animals. Wilderness-like conservation reserves have proven a successful strategy for sustaining ecological processes and biodiversity (Gaston et al. 2008), and they are still considered among the highest climate-adaptation priorities (Hagerman and Satterfield 2014). Intervention in these areas may be unnecessary, risky, and fraught with unintended consequences.

Low value, low vulnerability (yellow regions of figure 1c)

Restorative interventions that use historical range of variability as a guide make sense where conservation values have been degraded and future climate will be least altered. Although their current ecological and connectivity values may be low, the relative stability of climate into the future in these areas suggests that past conditions may still provide a guide to sustaining future biodiversity. Restoring historical processes and species composition in these areas may yield effective results for biodiversity conservation.

Low value, high vulnerability (red regions of figure 1c)

Low-value areas with high climate vulnerability (e.g., a strip-mined landscape with expected high climate velocity) may be important candidates for prospective interventions that restore degraded ecological processes (Higgs et al. 2014) and experiment with establishing regionally native species or genotypes suited to the projected future climate (e.g., Rehfeldt and Jaquish 2010). These approaches may sustain ecosystem services and native biodiversity, even where conservation values are currently low, without giving up on the importance of maintaining regional native species pools. We caution against using exotic species in these areas because risks of intentional or unintentional invasions are well documented (Mack et al. 2000).

High value, high vulnerability (blue regions of figure 1c)

Finally, areas with both high conservation value and high climate vulnerability present a challenge. These important lands are relatively intact, serve as important corridors, and are composed of ecosystems or species underrepresented in protected areas, but they may also be highly affected by climate change. Here, as in other high-value areas, we recommend maintaining connectivity and protecting ecosystems from additional stressors such as mineral extraction, livestock grazing, road building, invasive species, or other intensive development that alters land cover. However, we recognize that management interventions may be necessary because climate change affects species and ecosystems. In these regions, it may be most appropriate to spread risk among a portfolio of management strategies that are closely linked to rigorous monitoring programs. Managers should work to alleviate or prevent potential stressors to nature, but they should also understand that intervention and management flexibility to address climate-change challenges may be needed (Radeloff et al. 2015) after closely scrutinizing risks of unintended consequences. Experimental applications of treatments would be applied if monitoring indicators of ecosystem conditions triggered management thresholds (e.g., Bowker et al. 2013). Even in those lands where interventions may be deemed necessary, we should proceed with humility and employ experimental adaptive management, including untreated “controls,” where ecosystems can adjust to changes in climate and serve as references for any intervention (Larson et al. 2013).

In conclusion, the impacts of climate change have been a part of conservation considerations for at least three decades (Peters and Darling 1985). Recently, however, enhanced understanding of global-change science has presented a new suite of challenges, including (a) heightened perception of the risks associated with action as well as with inaction (e.g., Is intervention needed, or are the risks associated with action too high?); (b) uncertainty surrounding prospective versus retrospective restoration strategies (e.g., Does the historical range of variability still provide a guide for restoration and management?); (c) uncertainty associated with model predictions of climate change (Knutti and Sedláček 2012); (d) limited understanding of how ecosystems will respond to various aspects of climate change (Garcia et al. 2014); and (e) uncertainties about how ecosystems will respond to the actions we may take to sustain the very components of nature we hope to maintain (Stein et al. 2013). Our proposed framework and mapping approach can bring existing conservation values and estimates of climate vulnerability to bear on conservation planning or scenario development (Gray 2011). We provide a framework by which to evaluate different approaches using available data. Recognizing some of the uncertainties described above, we recommend that a portfolio of strategies be applied and actions adjusted as we monitor and learn from our experiments (Aplet and McKinley 2017). Conservation is a complex process, but we hope that our assessment can help organize data using a map and framework for considering conservation values and climate vulnerability.

References cited

- Anderson MG, Barnett A, Clark M, Ferree C, Sheldon AO, Prince J. 2012. Resilient Sites for Terrestrial Conservation in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic Region. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science. [Google Scholar]

- Aplet GH, Cole DN. 2010. The trouble with naturalness: Rethinking park and wilderness goals. Pages 12–29 in Cole DN, Yung L, eds. Beyond Naturalness: Rethinking Park and Wilderness Stewardship in an Era of Rapid Change. Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aplet GH, McKinley PS. 2017. A portfolio approach to managing ecological risks of global change. Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 3(art. e01261). [Google Scholar]

- Aycrigg JL, Davidson A, Svancara LK, Gergely KJ, McKerrow A, Scott JM. 2013. Representation of ecological systems within the protected areas network of the continental United States. PLOS ONE 8(art. e54689). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aycrigg JL, et al. 2016. Completing the system: Opportunities and challenges for a national habitat conservation system. BioScience 66: 774–784. [Google Scholar]

- Belote RT, Dietz MS, McRae BH, Theobald DM, McClure ML, Irwin GH, McKinley PS, Gage JA, Aplet GH. 2016. Identifying corridors among large protected areas in the United States. PLOS ONE 11(art. e0154223). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belote RT, Dietz MS, Jenkins CN, McKinley PS, Irwin GH, Fullman TJ, Leppi JC, Aplet GH. 2017. Wild, connected, and diverse: Building a more resilient system of protected areas. Ecological Applications. doi:10.1002/eap.1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowker MA, Miller ME, Belote RT, Garman SL. 2013. Ecological Thresholds as a Basis for Defining Management Triggers for National Park Service Vital Signs: Case Studies for Dryland Ecosystems. US Geological Survey; Open-File Report no. 2013–1244. (15 February 2016; https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2013/1244) [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C, Lawler JJ, Roberts DR, Hamann A. 2015. Biotic and climatic velocity identify contrasting areas of vulnerability to climate change. PLOS ONE 10(art. e0142024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross MS, et al. 2012. The adaptation for conservation targets (ACT) framework: A tool for incorporating climate change into natural resource management. Environmental Management 50: 341–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia RA, Cabeza M, Rahbek C, Araujo MB. 2014. Multiple dimensions of climate change and their implications for biodiversity. Science 344(art. 1247579). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston KJ, Jackson SF, Cantú-Salazar L, Cruz-Piñón G. 2008. The ecological performance of protected areas. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 39: 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Gillson L, Dawson TP, Jack S, McGeoch MA. 2013. Accommodating climate change contingencies in conservation strategy. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 28: 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray ST. 2011. From uncertainty to action: Climate change projections and the management of large natural areas. BioScience 61: 504–505. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman SM, Satterfield T. 2014. Agreed but not preferred: Expert views on taboo options for biodiversity conservation, given climate change. Ecological Applications 24: 548–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallegatte S. 2009. Strategies to adapt to an uncertain climate change. Global Environmental Change 19: 240–247. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs E, Falk DA, Guerrini A, Hall M, Harris J, Hobbs RJ, Jackson ST, Rhemtulla JM, Throop W. 2014. The changing role of history in restoration ecology. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12: 499–506. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs RJ, et al. 2006. Novel ecosystems: Theoretical and management aspects of the new ecological world order. Global Ecology and Biogeography 15: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs RJ, et al. 2010. Guiding concepts for park and wilderness stewardship in an era of global environmental change. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 8: 483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs RJ, et al. 2014. Managing the whole landscape: Historical, hybrid, and novel ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12: 557–564. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CN, Van Houtan KS, Pimm SL, Sexton JO. 2015. US protected lands mismatch biodiversity priorities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112: 5081–5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kareiva P, Marvier M. 2012. What is conservation science? BioScience 62: 962–969. [Google Scholar]

- Keane RE, Hessburg PF, Landres PB, Swanson FJ. 2009. The use of historical range and variability (HRV) in landscape management. Forest Ecology and Management 258: 1025–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Knutti R, Sedláček J. 2012. Robustness and uncertainties in the new CMIP5 climate model projections. Nature Climate Change 3: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Larson AJ, Belote RT, Williamson M, Aplet GH. 2013. Making monitoring count: Project design for active adaptive management. Journal of Forestry 111: 348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Mack RN, Simberloff D, Lonsdale WM, Evans H, Clout M, Bazzaz FA. 2000. Biotic invasions: Causes, epidemiology, global consequences, and control. Ecological Applications 10: 689–710. [Google Scholar]

- Magness DR, Morton JM, Huettmann F, Chapin FS, McGuire AD. 2011. A climate-change adaptation framework to reduce continental-scale vulnerability across conservation reserves. Ecosphere 2(art. 112). [Google Scholar]

- Martin J-L, Maris V, Simberloff DS. 2016. The need to respect nature and its limits challenges society and conservation science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 6105–6112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar CI, Stephenson NL, Stephens SL. 2007. Climate change and forests of the future: Managing in the face of uncertainty. Ecological Applications 17: 2145–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters RL, Darling JD. 1985. The greenhouse effect and nature reserves. BioScience 35: 707–717. [Google Scholar]

- Radeloff VC, et al. 2015. The rise of novelty in ecosystems. Ecological Applications 25: 2051–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeldt GE, Jaquish BC. 2010. Ecological impacts and management strategies for western larch in the face of climate-change. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 15: 283–306. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz OJ, et al. 2015. Conserving biodiversity: Practical guidance about climate change adaptation approaches in support of land-use planning. Natural Areas Journal 35: 190–203. [Google Scholar]

- Stein BA, et al. 2013. Preparing for and managing change: Climate adaptation for biodiversity and ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 11: 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Theobald DM. 2013. A general model to quantify ecological integrity for landscape assessments and US application. Landscape Ecology 28: 1859–1874. [Google Scholar]

- Watson JEM, Iwamura T, Butt N. 2013. Mapping vulnerability and conservation adaptation strategies under climate change. Nature Climate Change 3: 989–994. [Google Scholar]

- Watson JEM, Shanahan DF, Di Marco M, Sanderson EW, Mackey B. 2016. Catastrophic declines in wilderness areas undermine global environment targets. Current Biology 26: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]