Abstract

Merkel cell carcinoma is a primary cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma, which once metastatic is difficult to treat. Recent mutation analyses of Merkel cell carcinoma revealed a low number of mutations in Merkel cell polyomavirus-associated tumors, and a high number of mutations in virus-negative combined squamous cell and neuroendocrine carcinomas of chronically sun-damaged skin. We speculated that the paucity of mutations in virus-positive Merkel cell carcinoma may reflect a pathomechanism that depends on derangements of chromatin without alterations in the DNA sequence (epigenetic dysregulation). One central epigenetic regulator is the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which silences genomic regions by trimethylating (me3) lysine (K) 27 of histone H3, and thereby establishes the histone mark H3K27me3. Recent experimental research data demonstrated that PRC2 loss in mice skin results in the formation of Merkel cells. Prompted by these findings, we explored a possible contribution of PRC2 loss in human Merkel cell carcinoma. We examined the immunohistochemical expression of H3K27me3 in 35 Merkel cell carcinomas with pure histological features (22 primary and 13 metastatic lesions) and in 5 combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin. We found a strong reduction of H3K27me3 staining in tumors with pure histologic features and virus-positive Merkel cell carcinomas. Combined neuroendocrine carcinomas had no or only minimal loss of H3K27me3 labeling. Our findings suggest that a PRC2-mediated epigenetic deregulation may play a role in the pathogenesis of virus-positive Merkel cell carcinomas and in tumors with pure histologic features.

Keywords: Merkel cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine, immunohistochemistry, Polycomb Repressive Complex 2, PRC2, H3K27me3, epigenetics

INTRODUCTION

Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive primary cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma with an estimated annual incidence of 0.6 cases per 100,000 persons1–3. Risk factors for developing Merkel cell carcinoma include chronic sun-damage and immune-suppression4, 5. Stage I disease is surgically curable, but despite recent progress in treating Merkel cell carcinoma patients with the PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab6, advanced disease has been difficult to treat7–9.

Merkel cell carcinoma is commonly associated with clonal integration of the Merkel cell polyomavirus10, 11, especially in the setting of immune-suppression and tumors arising de novo in the dermis and/or subcutis of sun-protected skin. The Merkel cell polyomavirus is less frequently found in tumors of chronically sun-damaged skin and is usually absent in combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinomas11, 12.

We and others have recently found that oncogenic mutations are frequent in combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinomas, but rare in classic virus-associated Merkel cell carcinoma12–14. These observations suggest that there are at least two major pathogenetic variants of cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma: a virus-independent pathomechanism driven by UV-induced mutations, and a virus-associated pathomechanism, in which mutations have a subordinate role.

In recent years, it became clear that epigenetic changes play a significant role in the development of cancer. For example, the genomic analyses of pediatric cancers have identified several tumor types with few or no mutations, suggesting that epigenetic dysregulation can drive cancer15. The Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) complex is one of the central epigentic regulators, which catalyzes the trimethylation (me3) of lysine (K) 27 at histone H3 (H3K27me3) and thereby regulates chromatin compaction and controls transcriptional activity. Recent basic research studies in mice found that loss of PRC2 in the epidermis leads to the formation of Merkel cells through the upregulation of key Merkel-differentiation genes16, 17. These observations in mice have led us to investigate the role of PRC2 in the development of human virus-associated Merkel cell carcinoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the institutional review board. 40 tumors were analyzed immunohistochemically, including 35 Merkel cell carcinomas with pure histologic features (22 primary and 13 metastatic lesions) and 5 primary combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinomas. All tumors were from different patients. Tumors were only accepted as Merkel cell carcinoma, if clinically the presentation of a primary cutaneous tumor was obvious (no prior history of neuroendocrine carcinoma elsewhere) and/or the tumors were positive for at least one of the following three markers (Cam 5.2, CK20, neurofilament) with a perinuclear dot-like staining pattern, and also negative for TTF1.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Five micron thick sections were taken from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue. Sections were taken from both whole tumor profiles.

An automated immunohistochemistry system (Leica Bond, polymer) was used for the detection of H3K27me3, using a commercially available antibody (Cell Signaling, clone C36B11), as well as the Merkel cell polyoma virus large T-antigen (Santa Cruz, clone CM2B4, dilution 1:150). For CK20 used in the routine clinical work-up a different automated immunohistochemistry system (Ventana BenchMark XT, Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ) was used, with a ready to use reagent (Ventana Ks20.8).

Labeling was scored according to the percentage of immunoreactive tumor cells per total number of tumor cells: 0 = no staining; 1+ = 1 – 25% of tumor cells are positive; 2+ = 26–50% of tumor cells are positive; 3+ = 51–75% of tumor cells positive and 4+ = 76–100% of tumor cells are positive.

Micro-dissection and DNA extraction

For each tumor normal control tissue and tumor tissue were examined. Non-tumor tissue was manually removed to enrich the tumor cell population to at least 80% of the entire tissue sample. The tissue was then scraped off from sections of archival paraffin-embedded tissue into sterile Eppendorf tubes. Microscopically uninvolved skin was used as normal background control. DNA was extracted and purified with a QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Targeted Next-generation sequencing

Next-generation sequencing was performed on a subset of twelve tumors using the IMPACT assay (Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets) as previously described18. Briefly, IMPACT is a hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing assay for targeted deep sequencing of all exons and selected introns of 341 key cancer genes in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumors. The libraries are sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer with a 100 bp paired-end protocol. Reads were aligned to the reference human genome hg19 using the Burrows-Wheeler Alignment tool19 and post-processed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) according to GATK best practices20. Somatic alterations (single base substitutions, small insertions and deletions, and copy number alterations) were identified according to their presence in the tumor genome and absence from the corresponding normal genome. Single-nucleotide variants were called using muTect21 and retained if the variant allele frequency in the tumor was >5 times that in the matched normal. Insertions and deletions (indels) were called using the SomaticIndelDetector tool in GATK. All candidate mutations and indels were reviewed manually using the Integrative Genomics Viewer.

Statistical Analysis

Fisher exact tests were used to evaluate the association of the categorical variables (tumor type, immunoreactivity for Merkel cell polyoma virus, presence of mutations) with reduction in labeling for H3K27me3. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were conducted using Excel (Microsoft).

RESULTS

Clinical Findings

The clinical and pathologic findings are summarized in Table 1. Among the 25 patients with primary pure Merkel cell carcinoma, 17 were male, 8 female. The mean age at diagnosis was 73.5 years; the median was 76.6 years. Eleven primary tumors were located on the extremities, 8 in the head and neck region and 6 on the trunk. Of the 15 patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma, 10 were male, 5 female. The mean and median ages at diagnosis were 76.5 and 78.5 years, respectively.

Table 1.

Patients with Merkel cell polyomavirus-positive tumors (immunoreactive for CM2B4).

| Age (years) |

Gender | Primary Site | H3K27me3 IHC |

Tumor Stage |

Number of Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 74 | F | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 77 | M | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 71 | F | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 77 | M | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 74 | F | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | None detected |

| 80 | F | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 78 | M | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 62 | M | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 78 | F | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 80 | F | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 85 | F | Head and Neck | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 65 | M | Head and Neck | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 77 | M | Trunk | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 48 | M | Trunk | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 75 | M | Trunk | 1+ | 1 | None detected |

| 76 | M | Trunk | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 52 | F | Extremity | 1+ | 1 | ? |

| 75 | M | Extremity | 1+ | 2 | None detected |

| 84 | F | Extremity | 1+ | 2 | None detected |

| 65 | M | Extremity | 1+ | 2 | None detected |

| 79 | M | Extremity | 1+ | 2 | None detected |

| 80 | M | Extremity | 1+ | 2 | None detected |

| 78 | M | Extremity | 1+ | 2 | ? |

| 89 | M | Extremity | 1+ | 2 | ? |

| 74 | M | Head and Neck | 1+ | 2 | ? |

| 90 | M | Head and Neck | 1+ | 2 | None detected |

| 97 | F | Head and Neck | 1+ | 2 | None detected |

| 83 | F | Trunk | 1+ | 2 | None detected |

| 52 | M | Trunk | 1+ | 2 | None detected |

| 75 | F | Trunk | 1+ | 2 | None detected |

Abbreviations/Explanations: CM2B4 – antibody to Merkel cell polyoma virus large T-antigen.

F = female; M = male; Tumor Stage: 1 = primary tumor; 2 = locoregional (lymph node or soft tissue) metastasis; IHC = immunohistochemistry; 1 + = positive labeling in 1 – 25% of tumor cells

? = unknown (mutation analysis was not performed)

All 5 patients with primary combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin were men. The mean and median ages at diagnosis were 75 and 74 years, respectively. Three tumors were located in the head and neck region, one was on the trunk and one on the upper arm.

Immunohistochemical Findings

Of the 40 Merkel cell carcinomas, 30 (75%) were positive for CM2B4 indicating virus integration, 10 (25%) were negative, including all 5 combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinomas. As documented in Tables 1 and 2 and illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, loss of labeling for H3K27me3 in the majority (> 50%) of tumor cells was strongly associated with pure histology (p < 0.0001) and positive labeling for CM2B4 (p < 0.0001). None of the virus-positive Merkel cell carcinomas studied herein expressed H3K27me3 in more than 25% of the tumor cells. In most of them (25/30), less than 10% of the tumor cells were positive for H3K27me3. None of the pure Merkel cell carcinomas of this series expressed H3K27me3 in more than 50% of its tumor cells. On the other hand, combined neuroendocrine and squamous cell carcinomas showed minimal or no reduction in labeling for H3K27me3 (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Patients with tumors immunonegative for Merkel cell polyomavirus (CM2B4)

| Age (years) |

Gender | Primary Site | H3K27me3- IHC |

Tumor Stage |

Histologic Type |

Number of Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 71 | M | Extremity | 4+ | 1 | Mixed | ? |

| 74 | M | Head and Neck | 4+ | 1 | Mixed | ? |

| 67 | M | Head and Neck | 4+ | 1 | Mixed | 12 |

| 79 | M | Head and Neck | 4+ | 1 | Mixed | ? |

| 82 | M | Trunk | 4+ | 1 | Mixed | 16 |

| 70 | F | Head and Neck | 2+ | 1 | Pure | ? |

| 86 | M | Head and Neck | 2+ | 1 | Pure | 68 |

| 64 | M | Head and Neck | 1+ | 1 | Pure | ? |

| 71 | M | Trunk | 1+ | 1 | Pure | ? |

| 60 | M | Head and Neck | 1+ | 1 | Pure | 38 |

Abbreviations/Explanations: CM2B4 = monoclonal antibody to Merkel cell polyomavirus large T-antigen; F = female; M = male; Tumor stage: 1 = primary skin tumor; ? = unknown (mutation analysis was not performed); IHC = immunohistochemistry; 1+ = 1 – 25% of tumor cells are positive; 2+ = 26–50% of tumor cells are positive; 3+ = 51–75% of tumor cells positive and 4+ = 76–100% of tumor cells are positive.

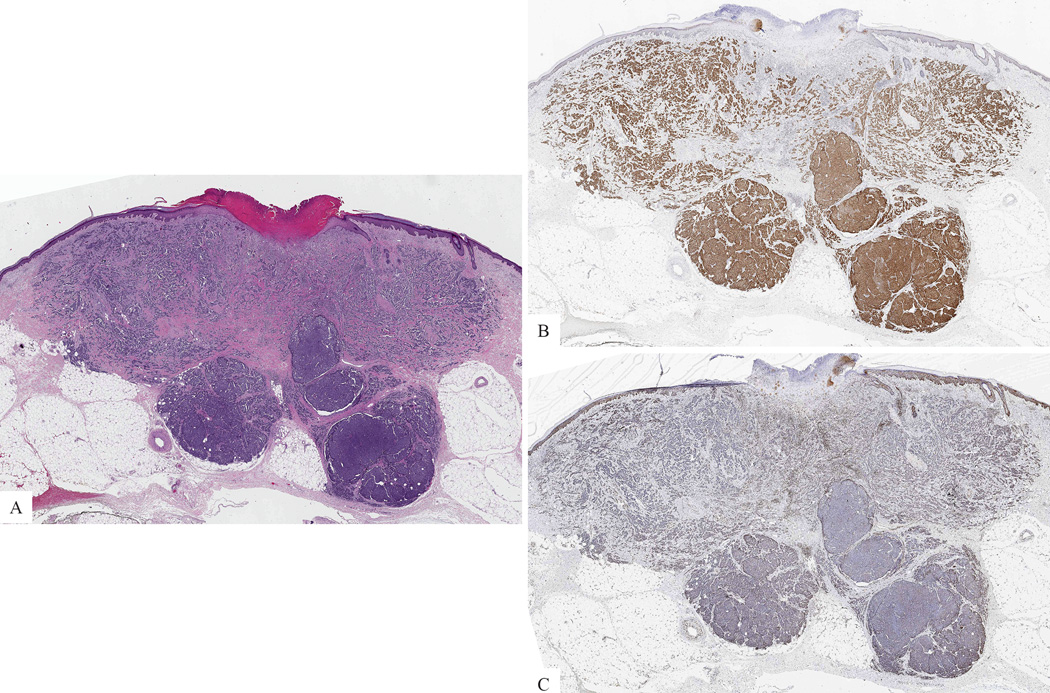

Figure 1. Primary cutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma.

A: Nodule in dermis and subcutis (H&E-stained section). B: The tumor cells are positive for CM2B4. C: The tumor cells lack expression of H3K27me3.

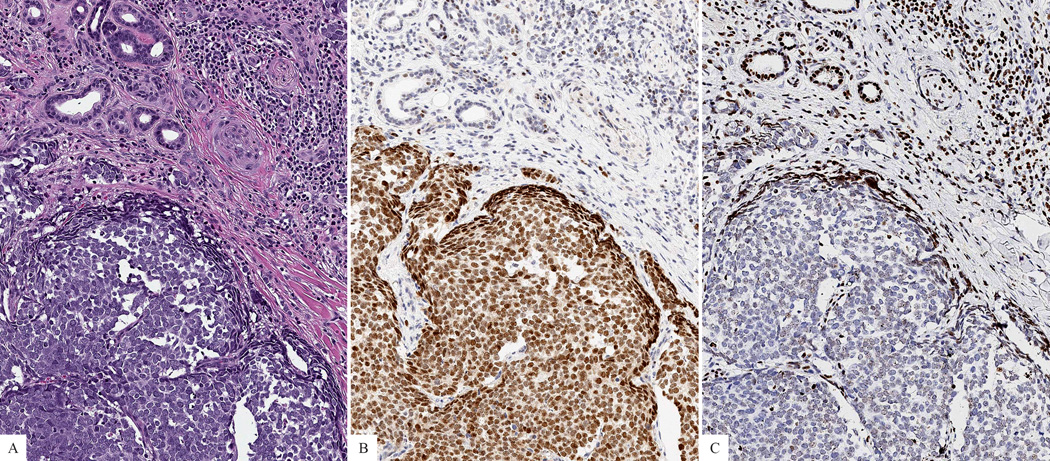

Figure 2. Primary cutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma.

A: Nodule of malignant tumor cells with cytologic features of neuroendocrine differentiation. B: The tumor cells are positive for CM2B4. C: The tumor cells lack expression of H3K27me3, while adjacent non-neoplastic cells are positive.

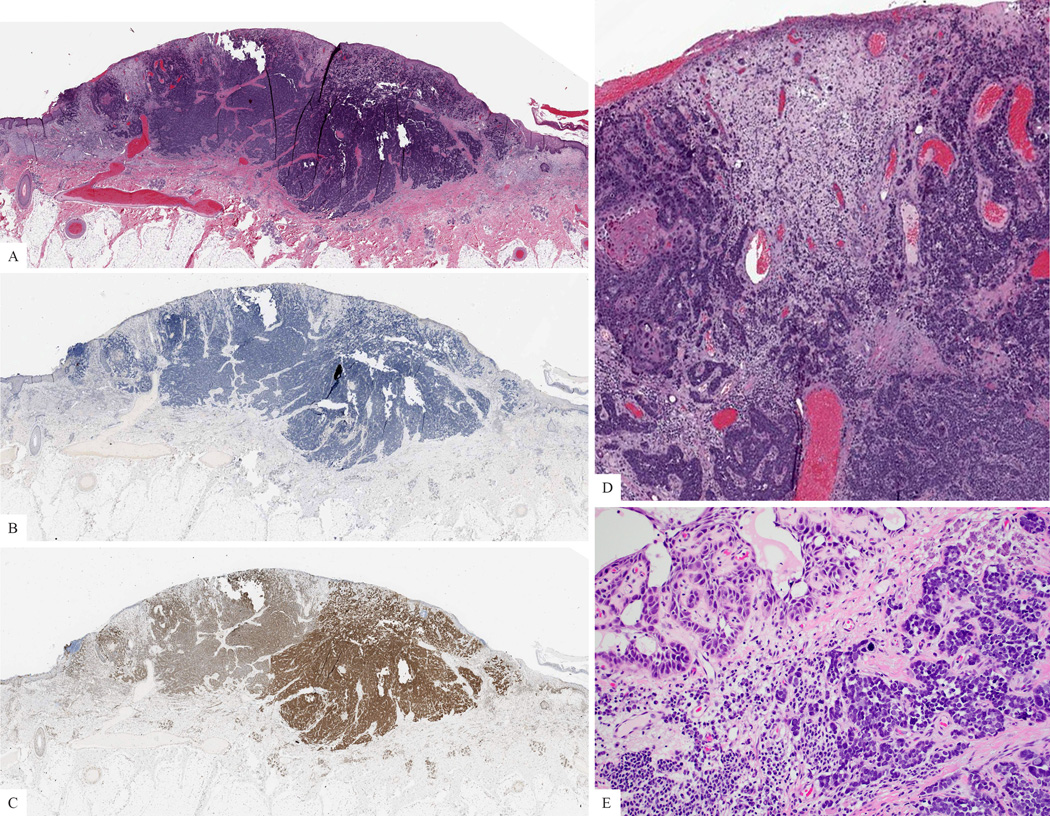

Figure 3. Combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin.

A. Silhouette of the lesion (H&E). B: The tumor cells are negative for CM2B4. C: The tumor cells express H3K27me3. D: Combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinoma. The small cell neuroendocrine component dominates. E: Focally, the tumor displays squamous differentiation, with features of acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma.

Molecular Findings and Association with IHC

The number of mutations per tumor detected in a selected subset of Merkel cell carcinoma is documented in Tables 1 and 2. No mutations were identified in the pure virus-positive Merkel cell carcinomas of this series. Mutations were detected in tumors, which were virus-negative and/or had combined phenotype of invasive squamous and neuroendocrine carcinoma or associated extensive actinic keratosis in the same tissue sample that was submitted for mutation analysis. All tumors without mutations showed marked reduction in labeling for H3K27me3. No significant reduction in labeling for H3K27me3 was seen in two cases of combined invasive squamous and neuroendocrine carcinoma, which were found to carry mutations. However, reduction in labeling for H3K27me3 was also seen in one case of virus-negative Merkel cell carcinoma with associated actinic keratosis and mutations.

DISCUSSION

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare skin tumor2. The discovery of the Merkel cell polyomavirus in the majority of tumors has been a milestone in understanding the biology of this tumor3, 10. However, not all tumors show clonal integration and little is known about the pathway how viral integration leads to malignant transformation.

Efforts to identify driver mutations in Merkel cell carcinoma have so far failed to reveal characteristic genomic aberrations. Recent mutation analyses of Merkel cell carcinomas and combined cutaneous squamous and neuroendocrine carcinomas indicate that mutations are frequent in virus-negative Merkel cell carcinomas and in combined neuroendocrine carcinomas, but uncommon in classic virus-associated Merkel cell carcinoma. Results from molecular analysis of the subset of cases, which were tested for mutations in the clinical setting to identify possible treatment targets, support the notion that the mutation burden of virus-independent, UV-related tumors tends to be high, while virus-associated Merkel cell carcinomas tend to lack or harbor only few mutations. The results of mutation analyses of the cases reported herein are in keeping with those observations. The lack of frequent mutations in virus-associated Merkel cell carcinoma made us hypothesize about a possible role of epigenetic events in the pathogenesis of Merkel cell carcinoma.

Post-translational modifications of the N-terminal cores of histones, such as by methylation, influences chromatin configuration and thereby modulates accessibility of transcription factors and transcriptional activity22. The Polycomb repressive complexes 2 (PRC2) containing enhancer of zeste (EZH) 2, a methyltransferase and core component of PRC2, are responsible for trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H323. H3K27me3 is a well-established histone mark for epigenetic gene silencing and chromatin compaction, which decreases the transcriptional activity. Loss of trimethylation on H3K27 has been found in different types of cancers, including malignant peripheral nerve sheet tumors (MPNSTs)24–26 or pediatric high-grade gliomas27 and has been correlated with adverse prognosis in metastatic colon cancer20.

H3K27me3 expression levels can be assessed in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues by immunohistochemistry24. To explore a potential role of epigenetic events in Merkel cell carcinoma, we examined H3K27me3 expression levels in primary and metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma as well as combined cutaneous squamous and neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Our findings indicate that decreased labelling of H3K27me3 is strongly associated with a pure histologic phenotype of Merkel cell carcinomas and virus-positive Merkel cell carcinomas. Combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinomas retained expression of H3K27me3. The results suggest that epigenetic deregulation may play a role in the pathogenesis of pure Merkel cell carcinoma, in particular those tumors associated with the Merkel cell polyomavirus. Failure to detect a significant reduction in H3K27me3 labeling in combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin provides further support to prior observations that the pathobiology of combined tumors is different from pure Merkel cell carcinoma. Combined squamous and neuroendocrine carcinomas are pathogenetically more closely related to squamous cell carcinomas of sun-damaged skin.

Epigenetic changes are not only of interest for the pathogenesis and classification of neuroendocrine carcinomas, they may also be targets, for which novel treatment strategies for patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma could be developed. Although recent evidence suggests that immunotherapeutic approaches to Merkel cell carcinoma are promising6, immunotherapy is unlikely to cure the majority of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. Thus, additional treatments are needed, including strategies to interfere with epigenetic mechanisms of tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: This work was supported by grants from the Harry J. Lloyd Trust - Translational Research Grant to K.J.B and T.W., and the Charles H. Revson Senior Fellowship to T.W. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Cancer Center Support Grant of the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute under award number P30CA008748.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bichakjian CK, Lowe L, Lao CD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer. 2007;110:1–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pulitzer MP, Amin BD, Busam KJ. Merkel cell carcinoma: review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:135–144. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181a12f5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moshiri AS, Nghiem P. Milestones in the staging, classification, and biology of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:1255–1262. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oram CW, Bartus CL, Purcell SM. Merkel cell carcinoma: a review. Cutis. 2016;97:290–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nghiem P. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Intersection of Immune Dysfunction, Infection, and Malignant Progression. J Invest Derm Symp P. 2015;17:36. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2015.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. PD-1 Blockade with Pembrolizumab in Advanced Merkel-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2542–2552. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassler NM, Merrill D, Bichakjian CK, et al. Merkel Cell Carcinoma Therapeutic Update. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17:36. doi: 10.1007/s11864-016-0409-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fields RC, Busam KJ, Chou JF, et al. Five hundred patients with Merkel cell carcinoma evaluated at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2011;254:465–473. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822c5fc1. discussion 73–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatia S, Storer BE, Iyer JG, et al. Adjuvant Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy in Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Survival Analyses of 6908 Cases From the National Cancer Data Base. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang Y, Moore PS. Merkel cell carcinoma: a virus-induced human cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:123–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busam KJ, Jungbluth AA, Rekthman N, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus expression in merkel cell carcinomas and its absence in combined tumors and pulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1378–1385. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181aa30a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pulitzer MP, Brannon AR, Berger MF, et al. Cutaneous squamous and neuroendocrine carcinoma: genetically and immunohistochemically different from Merkel cell carcinoma. Modern Pathol. 2015;28:1023–1032. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harms PW, Vats P, Verhaegen ME, et al. The Distinctive Mutational Spectra of Polyomavirus-Negative Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3720–3727. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harms PW, Collie AM, Hovelson DH, et al. Next generation sequencing of Cytokeratin 20-negative Merkel cell carcinoma reveals ultraviolet-signature mutations and recurrent TP53 and RB1 inactivation. Modern Pathol. 2016;29:240–248. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feinberg AP, Koldobskiy MA, Gondor A. Epigenetic modulators, modifiers and mediators in cancer aetiology and progression. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:284–299. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perdigoto CN, Dauber KL, Bar C, et al. Polycomb-Mediated Repression and Sonic Hedgehog Signaling Interact to Regulate Merkel Cell Specification during Skin Development. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardot ES, Valdes VJ, Zhang J, et al. Polycomb subunits Ezh1 and Ezh2 regulate the Merkel cell differentiation program in skin stem cells. EMBO J. 2013;32:1990–2000. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan AA, Lee AJ, Roh TY. Polycomb group protein-mediated histone modifications during cell differentiation. Epigenomics. 2015;7:75–84. doi: 10.2217/epi.14.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He WP, Li Q, Zhou J, et al. Decreased expression of H3K27me3 in human ovarian carcinomas correlates with more aggressive tumor behavior and poor patient survival. Neoplasma. 2015;62:932–937. doi: 10.4149/neo_2015_113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prieto-Granada CN, Wiesner T, Messina JL, et al. Loss of H3K27me3 Expression Is a Highly Sensitive Marker for Sporadic and Radiation-induced MPNST. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:479–489. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaefer IM, Fletcher CD. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) arising in diffuse-type neurofibroma: clinicopathologic characterization in a series of 9 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1234–1241. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee W, Teckie S, Wiesner T, et al. PRC2 is recurrently inactivated through EED or SUZ12 loss in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1227–1232. doi: 10.1038/ng.3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bender S, Tang Y, Lindroth AM, et al. Reduced H3K27me3 and DNA hypomethylation are major drivers of gene expression in K27M mutant pediatric high-grade gliomas. Cancer cell. 2013;24:660–672. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.