Abstract

Background

We investigated the relationship between metabolic activity and histological features of gliomas using fluorine-18α-methyltyrosine (18F-FAMT) positron emission tomography (PET) compared with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET in 38 consecutive glioma patients. The tumor to normal brain ratios (T/N ratios) were calculated, and the relationships between T/N ratio and World Health Organization tumor grade or MIB-1 labeling index were evaluated. The diagnostic values of T/N ratios were assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses to differentiate between high-grade gliomas (HGGs) and low-grade gliomas (LGGs).

Results

Median T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET was 2.85, 4.65, and 4.09 for grade II, III, and IV gliomas, respectively, with significant differences between HGGs and LGGs (p = 0.006). Both T/N ratio (p = 0.016) and maximum standardized uptake value (p = 0.033) of 18F-FDG PET showed significant differences between HGGs and LGGs. ROC analysis yielded an optimal cut-off of 3.37 for the T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET to differentiate between HGGs and LGGs (sensitivity 81%, specificity 67%, accuracy 76%, area under the ROC curve 0.776). Positive predictive value was 84%, and negative predictive value was 62%. T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET was not correlated with MIB-1 labeling index in all gliomas, whereas T/N ratio of 18F-FDG PET was positively correlated (r s = 0.400, p = 0.013). Significant positive correlation was observed between T/N ratios of 18F-FDG and 18F-FAMT (r s = 0.454, p = 0.004), but median T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET was significantly higher than that of 18F-FDG PET in all grades of glioma.

Conclusions

The T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT uptake has high positive predictive value for detection of HGGs. 18F-FAMT PET had higher T/N ratio, with better tumor-normal brain contrast, compared to 18F-FDG PET in both LGGs and HGGs. Therefore, 18F-FAMT is a useful radiotracer for the preoperative visualization of gliomas.

Keywords: 18F-FAMT, PET, Glioma, 18F-FDG, MIB-1 labeling index

Background

Magnetic resonance imaging with or without gadolinium enhancement is the standard method for the diagnosis of brain tumors, but new imaging methods have also been proposed based on the specific metabolic characteristics of gliomas. Malignant gliomas have increased metabolism caused by anaerobic glycolysis, so that positron emission tomography (PET) using fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG), a glucose analog, is now widely used for the diagnosis of gliomas [1]. However, the high utilization of glucose by normal gray matter makes identification of other brain tumors difficult on 18F-FDG PET [2]. Consequently, PET imaging of glucose metabolism is basically unsuitable for the detection of tumors against the background of the normal brain.

Radiolabeled amino acids are well-established tracers for brain tumor imaging with PET. The Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology working group has recently recommended the use of amino acid PET imaging for brain tumor management in addition to magnetic resonance imaging [3, 4]. L-[methyl-11C]methionine (11C-MET) is the most widely used amino acid PET imaging tracer for gliomas for the preoperative detection, diagnosis of subtypes and grades, differential diagnosis from radiation necrosis, estimation of tumor infiltration, and delineation of the border of tumor removal [5, 6]. Methyl-11C-choline, another PET radiotracer, potentially reflects the grade of malignancy [7]. However, the short half-life (20 min) of 11C requires in-house radiosynthesis and repeated radiolabeling of the tracer for each PET study, resulting in limited use only in PET centers with an in-house cyclotron facility [7]. Consequently, development of an amino acid tracer using the long half-life of 18F has been desirable to overcome these disadvantages of 11C-labeled agents [2]. Recently, the 18F-based PET tracers, O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (18F-FET) and L-6-[18F]fluoro-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalnine have been used for the imaging of brain tumors [8–12]. In Europe, the high clinical interest in 18F-FET PET has led to more than 10000 PET scans being performed in some centers [13].

Previously, we developed L-[3-18F]-α-methyltyrosine (18F-FAMT), a new amino acid tracer for PET imaging and demonstrated its potential for detecting neoplasms using experimental tumor models [14, 15]. 18F-FAMT accumulates in tumor cells only via an amino acid transport system, and most of the incorporated 18F-FAMT is not metabolized [14, 15]. Recently, we have made advances in the clinical utility of 18F-FAMT PET for the investigation of lung cancers, oral and maxillofacial cancers, and other tumors [16–20]. Our preliminary study showed specific accumulation of the tracer in 15 patients with glioma, including 7 cases before treatment [21]. However, no detailed study has assessed 18F-FAMT PET in a glioma series.

The present study investigated the value of 18F-FAMT uptake for differentiating high-grade glioma (HGG) from low-grade glioma (LGG) and the correlation with the proliferation rate, compared with 18F-FDG as the standard PET tracer.

Methods

Patients

The clinical records of patients treated between July 2007 and December 2013 were retrospectively reviewed. The criteria for inclusion were (i) histopathology of the tumor was established by open surgery or by stereotactic biopsy, and (ii) both 18F-FAMT PET and 18F-FDG PET were performed in random order before surgery within 2 months. The histological type of the tumors was determined by the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system [22]. No cases of pilocytic astrocytomas (WHO grade I) were included. Extremely rare histological types were also excluded. None of the patients had insulin-dependent diabetes, and serum glucose levels were less than 120 mg/dL in all patients just before 18F-FAMT or 18F-FDG injection. All patients agreed to participate in this study and provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Gunma University Graduate School of Medicine.

PET studies

Both 18F-FDG and 18F-FAMT were synthesized in the cyclotron facility of our institute, with 18F-FAMT produced according to the methods of Tomiyoshi et al. [14].

In this study, PET used a Discovery STE (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) or Biograph 16 (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA) scanner, with field of view of 700 mm and slice thickness of 3.27 mm. Three-dimensional data acquisition was performed for 3 min per bed position, followed by imaging reconstruction with the three-dimensional ordered-subset expectation maximization method. Correction of segmented attenuation was based on 128 × 128 matrix images obtained by X-ray computed tomography (CT) (140 kV, 120–240 mAs) without intravenous contrast material. CT images were reconstructed using a conventional filtered back projection method. Axial full-width half-maximum at 1 cm from the center of field of view was 5.6 mm, and z-axis full-width half-maximum at 1 cm from the center of field of view was 6.3 mm. Intrinsic system sensitivity was 8.5 cps/kBq for three-dimensional acquisition. Patients were scanned from the thigh to the head in the arms-down position. Limited breath-holding at normal expiration was used during CT to avoid motion-induced artifacts and allow co-registration of CT and PET images in the area of the diaphragm.

Imaging analysis

All 18F-FAMT PET and 18F-FDG PET images were interpreted by two independent experienced nuclear physicians (Y.A. and T.H.), and final values were determined by consensus. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the interrater reliability. The interpreting physicians were unaware of the patient’s clinical history and data. For semi-quantitative analysis, the standardized uptake value (SUV) was obtained from an attenuation-corrected transaxial image. SUV was calculated as follows: radioactive concentration in the region of interest (ROI) (MBq/g)/injected dose (MBq)/patient body weight (g). The ROI was manually drawn over the primary tumor. ROI analysis was conducted by a nuclear medicine physician with reference to the CT and magnetic resonance images. The maximum SUV (SUVmax) and mean SUV in the ROI represent the uptake of 18F-FAMT and 18F-FDG in the lesion [23]. The ratio of the SUVmax in the tumor to the mean SUV in the contralateral normal brain (T/N ratio) was calculated. If the lesion was located in the thalamus, the T/N ratio to the contralateral normal thalamus was calculated.

Histological study

Surgical or biopsy specimens were fixed in 10% formalin and were embedded in paraffin. The histological tumor type was established based on specimens stained with hematoxylin and eosin, according to the previous WHO criteria [22]. The relevance of this investigation is limited by the fact that the tumor classification is based on the previous, out-of-date WHO classification and so may no longer be directly applicable to the current classification [24].

The cellular proliferation activity of the tumor was determined by measuring the MIB-1 proliferation index obtained by immunohistochemical staining with anti-Ki-67/MIB-1 antibody (Dako, Tokyo, Japan). The percentage of tumor cells stained positively for MIB-1 antigen (MIB-1 labeling index: MIB-1 LI) was determined in the area containing the largest number of positive tumor cells and was regarded as representative of the tumor proliferation activity.

Statistical analysis

All values are reported as proportions (%) or medians with interquartile range. Between-group comparisons of non-parametric data were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. To compare T/N ratios between 18F-FAMT and 18F-FDG, the Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test was used because of matched pairing. The correlation between different variables was analyzed using the non-parametric Spearman’s rank test. Probability values of <0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference. The diagnostic accuracy of the T/N ratio and SUVmax of 18F-FAMT and 18F-FDG uptake for differentiation of HGGs from LGGs was evaluated by receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve analysis using subsequent histological analysis of all lesions. The decision cutoff was considered optimal at the maximum of the product of paired values for sensitivity and specificity. In addition, the area under the ROC curve (AUC), its median, and the level of significance were determined as measures of the diagnostic quality of the test. For ROC analysis, the gliomas of WHO grades III and IV were considered together as HGGs. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for Mac.

Results

Uptake of 18F-FAMT and 18F-FDG

This study included 38 patients (24 men and 14 women), aged 16 to 79 years (median 52.5 years). The final pathological diagnosis was based on samples obtained by open craniotomy (n = 37) or biopsy (n = 1). The tumors were classified as WHO grade II in 12 patients, grade III in 12, and grade IV in 14, and the histological diagnoses are summarized in Table 1. The median SUV in the contralateral normal cortex was 0.94 (range 0.49 to 1.50) for 18F-FAMT, and 5.91 (range 2.20–18.9) for 18F-FDG. The SUVmax and T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT and 18F-FDG are summarized in Table 2. Correlation coefficient and interobserver agreement for quantitative measurements was very high in all cases (p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Histological characteristics of the tumors

| Histopathology | n (%) | Median MIB-1 LI (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| WHO grade II | 12 (32) | 4.1 (2.9–7.6) |

| Diffuse astrocytoma | 3 (8) | 7.4 |

| Oligoastrocytoma | 7 (18) | 3.8 (2.7–4.4) |

| Oligodendroglioma | 2 (5) | 5.3 |

| WHO grade III | 12 (32) | 16 (12–27) |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 3 (8) | 30 |

| Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma | 5 (13) | 14 (9–21) |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma | 4 (11) | 16 (7.7–19) |

| WHO grade IV | 14 (37) | 28 (21–41) |

| Glioblastoma | 14 (37) | 28 (21–41) |

MIB-1 LI MIB-1 labeling index, IQR interquartile range

Table 2.

18F-FAMT and 18F-FDG uptake in various tumor types

| Histological classification | 18F-FAMT | 18F-FDG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median SUVmax (IQR) | Median T/N ratio (IQR) | Median SUVmax (IQR) | Median T/N ratio (IQR) | |

| All gliomas | 3.45 (2.58–4.63) | 4.08 (2.87–4.76) | 6.65 (5.55–10.2) | 1.12 (0.86–1.83) |

| WHO grade II | 2.88 (2.04–3.75) | 2.85 (2.06–4.28) | 5.40 (4.20–8.45) | 0.88 (0.75–1.04) |

| Diffuse astrocytoma | 3.07 | 2.05 | 4.10 | 0.90 |

| Oligoastrocytoma | 2.65 (1.90–4.00) | 2.80 (2.11–4.33) | 5.10 (4.50–5.80) | 0.86 (0.62–0.88) |

| Oligodendroglioma | 3.60 | 4.23 | 10.7 | 1.39 |

| WHO grade III | 4.20 (2.17–5.75) | 4.65 (3.50–5.42) | 6.55 (6.00–8.28) | 1.17 (0.68–2.24) |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 2.63 | 5.20 | 6.60 | 1.22 |

| Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma | 2.68 (1.61–5.15) | 4.29 (2.47–5.05) | 6.00 (4.93–6.45) | 0.71 (0.63–1.17) |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma | 5.70 (4.93–6.40) | 5.03 (3.71–6.39) | 12.8 (6.70–21.3) | 1.91 (1.17–2.75) |

| WHO grade IV | 3.60 (3.05–4.60) | 4.09 (3.36–4.92) | 9.15 (6.38–11.5) | 1.56 (1.11–2.50) |

| Glioblastoma | 3.60 (3.05–4.60) | 4.09 (3.36–4.92) | 9.15 (6.38–11.5) | 1.56 (1.11–2.50) |

IQR interquartile range

T/N ratio and SUVmax

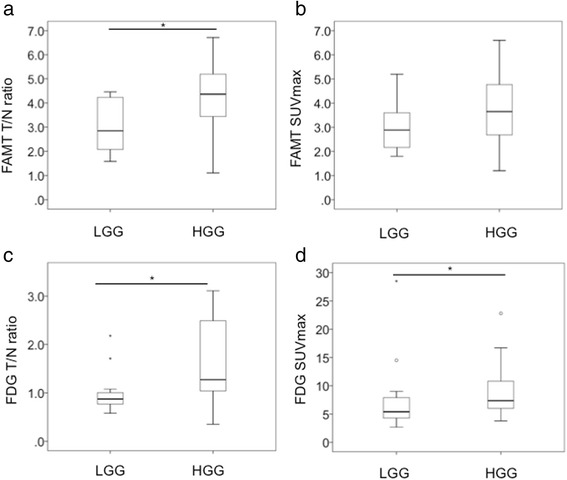

The median T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET was 2.85, 4.65, and 4.09 for grades II, III, and IV in all gliomas, respectively (Table 2). The median T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET was 2.85 for LGGs and 4.37 for HGGs, showing a significant difference between LGGs and HGGs (p = 0.006, Fig. 1a). The median SUVmax of 18F-FAMT PET was 2.88, 4.20, and 3.60 for grade II, III, and IV gliomas, respectively. However, the SUVmax of 18F-FAMT PET showed no significant differences between LGGs and HGGs (p = 0.087, Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Box-and-whisker plots of 18F-FAMT and 8F-FDG uptake for LGG and HGG. a The difference in T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT uptake between LGG and HGG was significant (p = 0.006). b The difference in SUVmax of 18F-FAMT uptake between LGG and HGG was not significant (p = 0.087). c, d The differences in T/N ratio and SUVmax of 18F-FDG uptake between LGG and HGG were significant (p = 0.016 and p = 0.033, respectively)

The median T/N ratio of 18F-FDG PET was 0.88, 1.17, and 1.56 for grade II, III, and IV gliomas, respectively (Table 2). The median T/N ratio of 18F-FDG PET was 0.88 for LGGs and 1.27 for HGGs. The median SUVmax of 18F-FDG PET was 5.40, 6.55, and 9.15 for grade II, III, and IV gliomas, respectively. The median SUVmax of 18F-FDG PET was 5.40 for LGGs and 7.37 for HGGs. Both the T/N ratio and the SUVmax of 18F-FDG PET showed significant differences between HGGs and LGGs (p = 0.016 and p = 0.033, respectively, Fig. 1c, d).

ROC analysis for 18F-FAMT PET and 18F-FDG PET

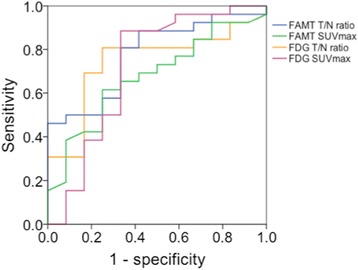

T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET was significantly higher for HGGs (n = 26) than for LGGs (n = 12) (4.37 ± 2.22 vs. 2.85 ± 1.81; p = 0.006) (Fig. 1a). ROC analysis for differentiation between HGGs and LGGs yielded an optimal cutoff of 3.37 for the T/N ratio (sensitivity 81%, specificity 67%, accuracy 76%, AUC 0.776, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.623–0.928). The positive predictive value (PPV) was 84%, and the negative predictive value (NPV) was 62% (Fig. 2). On the other hand, the SUVmax of 18F-FAMT PET showed no significant differences between HGGs and LGGs (3.65 ± 2.16 vs. 2.88 ± 1.71; p = 0.087) (Fig. 1b). ROC analysis for differentiation between HGGs and LGGs yielded an optimal cutoff of 3.45 for SUVmax of 18F-FAMT PET (sensitivity 61.5%, specificity 75%, accuracy 66%, AUC 0.675, 95% CI 0.497–0.852). The PPV was 84%, and the NPV was 47% (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

ROC curve analysis of T/N ratio (blue curve) and SUVmax (green curve) of 8F-FAMT to differentiate between HGGs and LGGs. Area under the curve was 0.776 for T/N ratio (p = 0.007, 95% CI 0.623–0.928, optimal cutoff 3.37) and 0.675 for SUVmax (p = 0.087, 95% CI 0.497–0.852, optimal cutoff 3.45). ROC curve analysis of T/N ratio (orange curve) and SUVmax (purple curve) of 8F-FDG to differentiate between HGGs and LGGs. Area under the curve was 0.742 for T/N ratio (p = 0.018, 95% CI 0.575–0.909, optimal cutoff 0.92) and 0.716 for SUVmax (p = 0.034, 95% CI 0.510–0.923, optimal cutoff 5.85)

T/N ratio of 18F-FDG PET was significantly higher for HGGs than for LGGs (1.27 ± 1.47 vs. 0.88 ± 0.29; p = 0.016) (Fig. 1c). ROC analysis yielded an optimal cutoff of 0.92 for the T/N ratio of 18F-FDG PET to differentiate between HGGs and LGGs (sensitivity 81%, specificity 67%, accuracy 76%, AUC 0.742, 95% CI 0.575–0.909). The PPV was 84%, and the NPV was 62% (Fig. 2). Similarly, SUVmax of 18F-FDG PET was significantly higher for HGGs than for LGGs (7.37 ± 4.92 vs. 5.40 ± 4.25; p = 0.033) (Fig. 1d). ROC analysis for differentiation between HGGs and LGGs yielded an optimal cutoff of 5.85 for SUVmax of 18F-FDG PET (sensitivity 89%, specificity 67%, accuracy 82, AUC 0.716, 95% CI 0.510–0.923). The PPV was 85%, and the NPV was 73% (Fig. 2).

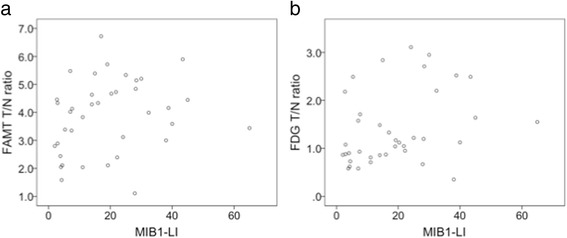

MIB-1 LI and T/N ratio

Neither the SUVmax nor the T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET was correlated with the MIB-1 LI in all gliomas (SUVmax: r s = 0.138, p = 0.408; T/N ratio: r s = 0.290, p = 0.077; Fig. 3a). The T/N ratio of 18F-FDG PET was also positively correlated with the MIB-1 LI in all gliomas (r s = 0.400, p = 0.013; Fig. 3b), whereas the SUVmax of 18F-FDG PET was not correlated (r s = 0.242, p = 0.144).

Fig. 3.

Correlation analysis between the MIB-1 LI and the T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET or 18F-FDG PET. a The T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET was not correlated with MIB-1 LI in all gliomas (r s = 0.290, p = 0.077). b The T/N ratio of 18F-FDG PET was positively correlated with MIB-1 LI in all gliomas (r s = 0.400, p = 0.013)

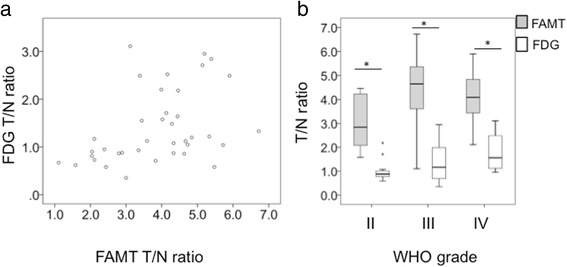

Comparison of 18F-FAMT and 18F-FDG

Significant positive correlation was observed between the T/N ratios of 18F-FDG and 18F-FAMT in all gliomas (r s = 0.454, p = 0.004; Fig. 4a). The median T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT was significantly higher than that of 18F-FDG in all gliomas (p < 0.05; Fig. 4b). The T/N ratio of 18F-FDG was lower than 1.0 in 15 (39%) of 38 gliomas, resulting in poor tumor-normal brain contrast. On the other hand, the T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT was greater than 2.0 in 36 (95%) of 38 gliomas, and all cases showed clear tumor-normal brain contrast. These results indicated that 18F-FAMT provides better tumor-normal brain contrast. Representative cases are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4.

a Correlation analysis between the T/N ratios of 18F-FAMT PET and 18F-FDG PET showed significant positive correlation in all gliomas (r s = 0.430, p < 0.01). b Comparison of the T/N ratios of 18F-FAMT PET and 18F-FDG PET found significant differences for each WHO grade (all p < 0.05)

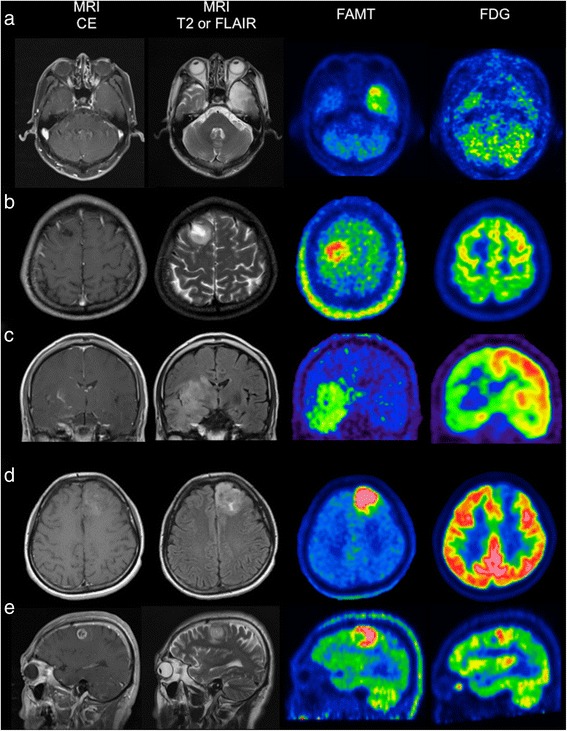

Fig. 5.

Representative cases. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance images (MRI CE), T2-weighted or fluid attenuated inversion recovery images (MRI T2 or FLAIR), 18F-FAMT PET images, and 18F-FDG PET images, from left to right. a A 71-year-old man with diffuse astrocytoma. 18F-FAMT T/N ratio was 2.05. 18F-FDG T/N ratio was 0.90. b A 32-year-old man with oligoastrocytoma. 18F-FAMT T/N ratio was 2.80. 18F-FDG T/N ratio was 0.86. c A 50-year-old man with anaplastic astrocytoma. 18F-FAMT T/N ratio was 5.33. 18F-FDG T/N ratio was 1.22. d A 39-year-old woman with anaplastic oligoastrocytoma. 18F-FAMT T/N ratio was 5.48. 18F-FDG T/N ratio was 0.58. e A 56-year-old man with glioblastoma. 18F-FAMT T/N ratio was 4.73. 18F-FDG T/N ratio was 1.05

Discussion

The T/N ratios of both 18F-FAMT and 18F-FDG were significantly higher for HGGs than for LGGs, although the T/N ratios of different tumor grades showed wide overlap. For HGGs, 18F-FAMT uptake beyond a T/N ratio cutoff of 3.37 or 18F-FDG uptake beyond a T/N ratio cutoff of 0.92 had a PPV of 84 or 84%, respectively. The T/N ratios of 18F-FAMT were not correlated with MIB-1 LI in all gliomas. The T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT was significantly higher than that of 18F-FDG in all gliomas and all tumor subtypes.

Radiosynthesis of 18F-FAMT, an amino acid analog with a relatively high chemical yield, was originally developed at our institute [14], and experimental and clinical investigations have demonstrated that accumulation of 18F-FAMT in tumor cells occurs via an amino acid transport system [14, 15, 23]. 18F-FAMT was predicted to act as a specific radiotracer of brain tumor tissue based on the low uptake by normal brain tissue compared with 18F-FDG and has proven specificity to detect gliomas [15]. No significant relationship between 18F-FAMT uptake and WHO grade of tumor was found in the first series of 15 glioma cases [21]. The current study has now demonstrated significantly different 18F-FAMT uptake in gliomas of various histologies and grades compared to 18F-FDG.

Recently, 11C-MET PET has become the most commonly used amino acid imaging modality for gliomas, although use is restricted to PET centers with an in-house cyclotron facility. 11C-MET PET is useful for detecting and delineating gliomas [5, 6, 25–28]. 11C-MET uptake shows positive correlation with astrocytoma grade (II/IV and III/IV) [5, 27]. However, oligodendroglioma, which is a low-grade tumor, may show higher uptake of 11C-MET than diffuse astrocytoma (WHO grade II) [5].18F-FAMT tracer was developed on the basis of the known accumulation in brain tumor tissue of L-3-[123I]iodo-α-methyl tyrosine [21]. Uptake of L-3-[123I]iodo-α-methyl tyrosine and of 11C-MET involves almost the same transport mechanism, system L, which is a Na-independent amino acid transport system, in cultured glioma cell lines [29]. In fact, L-3-[123I]iodo-α-methyl tyrosine single photon emission computed tomography and 11C-MET PET have equivalent clinical value in the diagnostic evaluation of glioma [29, 30]. Therefore, 18F-FAMT PET imaging is likely to have similar characteristics to 11C-MET PET imaging for glioma diagnosis. However, the cell transport systems of 18F-FAMT and 11C-MET may be different. L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) is a major route for the transport of large neutral amino acids, including L-tyrosine, L-leucine, and L-methionine, through the plasma membrane. LAT1 is essential in tumor growth and is widely expressed in primary human cancers as well as gliomas [31–33]. Recent findings have proved that 18F-FAMT is highly selective for LAT1 because of its α-methyl moiety [34], which suggests that the tumor imaging sensitivity and specificity of 18F-FAMT PET and 11C-MET PET may have subtle differences. Recently, another 18F-labeled amino acid tracer, 18F-FET, has been shown to be useful for PET diagnosis of glioma [8–10, 35]. 18F-FET PET has high T/N ratio and better contrast in all gliomas compared to 18F-FDG PET, similar to our findings for 18F-FAMT PET, and is a clinically valuable PET tracer for imaging of gliomas [8–10, 35]. 18F-FET was clearly proved to be transported through both LAT1 and LAT2, with less selectivity for LAT1 than 18F-FAMT [34]. However, a more recent study suggested that trapping of 18F-FET within the cells is caused by the asymmetry of its intra- and extracellular recognition by LAT1 [36]. Therefore, 18F-FET and 18F-FAMT have similar characteristics as 18F-based brain tumor imaging tracers, but with structural differences and different biological activities. Standard 18F-FET summation image analysis of the 20–40 min time frame revealed mean maximum tumor-to-background ratio (TBRmax) of 2.1 in LGGs and significantly higher TBRmax of 3.3 in HGGs (p < 0.001) [37]. ROC analyses revealed a cutoff value of TBRmax 2.7 for the differentiation between LGGs and HGGs in the conventional 20–40 min summation images (sensitivity 66.7%, specificity 77.9%, accuracy 70.4%) [37]. In our series, ROC analysis for differentiation between HGGs and LGGs yielded an optimal cutoff value of 3.37 for the T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT (sensitivity 81%, specificity 67%, accuracy 76%) The cutoff value is higher than for 18F-FET PET, but the accuracy of 18F-FAMT uptake may be considered equivalent. Further study is required for comparison of the imaging characteristics of 18F-FET PET and 18F-FAMT PET for the diagnosis of glioma.

MIB-1 LI is considered to be an indicator of the simple cell proliferation rate. In contrast, WHO grade is a direct index of the malignancy grade, based on the consideration of various pathological factors, including the presence of necrosis, nuclear polymorphism, microvascular proliferation, mitotic activity, etc. The present investigation found that the T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET was not correlated, but the T/N ratio of 18F-FDG PET was correlated with MIB-1 LI in all gliomas. The increase in 18F-FAMT uptake does not necessarily indicate high cell proliferation activity. Comparisons of the T/N ratios of 11C-MET PET and the MIB-1 LI have found a significant correlation in diffuse astrocytoma but not in oligodendroglial tumor [5, 26, 28]. In our cohort, the ratio of diffuse astrocytoma was small, and the larger ratio of oligodendroglial tumor may have affected our results suggesting the T/N ratio of 18F-FAMT PET was not correlated with MIB-1 LI in all gliomas.

The glucose metabolic rate is highest in the brain parenchyma compared to the other organs of the body. Consequently, 18F-FDG is less effective as a tracer for the diagnostic imaging of brain tumor. Therefore, novel non-18F-FDG brain tumor radiotracers have been intensively researched in the past decade [2]. Multiple studies have compared brain tumor imaging with radiolabeled amino acids and 18F-FDG with the general finding that amino acids are more sensitive than 18F-FDG to detect brain tumors [12, 38–47]. Amino acids provide higher tumor-normal brain contrast and are better suited to delineate the tumor extent, to differentiate tumor recurrence from treatment-related changes, and to assess treatment response. Whether 18F-FDG or amino acids is the better choice for grading and prognosis remains controversial [48]. In our study, the T/N ratios of 18F-FAMT PET and 18F-FDG PET in the ROC analysis were almost equivalent for the differential diagnosis of tumor grade. 18F-FAMT uptake in the normal brain parenchyma was 0.94 (median SUV) in our series, lower than that of 18F-FDG, and almost the same as that of 11C-MET [27] and 18F-FET [8]. 18F-FAMT PET provided clearer imaging with higher T/N ratio and better contrast in all gliomas compared to 18F-FDG PET. Delineation of tumor extent and definition of the optimal site for biopsy are well-known and important advantages of amino acid PET at initial evaluation of brain tumors [38–40, 45]. In this study, the difference in T/N ratio between 18F-FAMT PET and 18F-FDG PET was significant. We are interested in whether 18F-FAMT PET can provide valuable data for the decisions concerning evaluation of true tumor size, extent of tumor excision range, and identification of the optimal site for biopsy. Further study will be necessary for these investigations.

More reliable grading may be possible with dynamic 18F-FET PET, since this tracer exhibits differences in the time-activity curves of tracer uptake depending on tumor grade [34]. HGGs are characterized by an early peak around 10–15 min after injection followed by a decrease of 18F-FET uptake. In contrast, LGGs typically exhibit delayed and steadily increasing tracer uptake [49]. The differential kinetics of tracer uptake in HGGs and LGGs appear to be a special property of 18F-FET because such differences were not observed with 11C-MET or L-6-[18F]fluoro-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalnine [11, 50]. Therefore, dynamic study with 18F-labeled tracer may be useful as an indicator of tumor grade. Further dynamic study using 18F-FAMT PET will be necessary in the future.

There were limitations to the present study. This study was based on relatively strict pathological and grading differentiations in astrocytomas and oligodendroglial tumors. Therefore, some pathological categories included a relatively small number of samples. Furthermore, simultaneous 18F-FAMT PET and 18F-FDG PET imaging is the ideal method of comparison. Since both tracers are labeled with fluorine, the tracer half-life requires a suitable interval between these PET studies. In these 38 cases, the interval between 18F-FAMT PET and 18F-FDG PET studies ranged from 1 to 38 days, and the median was 5 days. Recently, accumulation of 18F-FAMT was reported to be strongly correlated with the expression of LAT1 in cancers [34]. However, correlation of 18F-FAMT transport and LAT1 expression was not examined in this study. A further study will be needed to investigate the mechanism of 18F-FAMT accumulations in gliomas. 18F-FAMT is a new radiotracer for brain tumor imaging. More experience with cases of gliomas or other brain tumors is needed. A comparative study with radiotracers other than 18F-FDG is also needed to clarify the diagnostic utility of 18F-FAMT PET.

Conclusions

18F-FAMT is a useful radiotracer for the preoperative evaluation of tumor malignancy. 18F-FAMT PET provides clearer imaging with higher T/N ratio and better contrast compared to 18F-FDG PET in all gliomas. Therefore, 18F-FAMT is a useful radiotracer for the preoperative visualization of gliomas.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following neuroradiologists for critical comments: Dr. Azusa Tokue of Department of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Gunma University Graduate School of Medicine, Maebashi, Gunma, Japan, and Dr. Takashi Shibasaki of Neurosurgery Section, Yuaikinen Hospital, Koga, Ibaraki, Japan. We also thank the following radiological technologist for technical assistance: Tsuyoshi Otake, Kazuhiro Kishi, and Hidenori Otake of Department of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Gunma University Graduate School of Medicine.

Funding

None.

Authors’ contributions

KH is the guarantor of integrity of the entire study, is responsible for the data analysis, statistical analysis, and manuscript writing. MT contributed to the study design, literature research, and manuscript editing. TH and YA helped in the data collection and data analysis. KS carried out the clinical study and data collection. JH and YH helped in the data analysis. YT and YY contributed to the manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All patients agreed to participate in this study, and provided written informed consent.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Gunma University Graduate School of Medicine.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CI

Confidence interval

- C-MET

L-[methyl-11C]methionine

- CT

Computed tomography

- F-FAMT

Fluorine-18α-methyltyrosine

- F-FDG

Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose

- F-FET

O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine

- HGG

High-grade glioma

- LAT1

L-type amino acid transporter 1

- LGG

Low-grade glioma

- MIB-1 LI

MIB-1 labeling index

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- ROI

Region of interest

- SUV

Standardized uptake value

- SUVmax

Maximum SUV

- T/N ratio

Tumor to normal brain ratio

- TBRmax

Maximum tumor-to-background ratio

- WHO

World Health Organization

References

- 1.Di Chiro G, Brooks RA. PET-FDG of untreated and treated cerebral gliomas. J Nucl Med. 1988;29:421–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulyás B, Halldin C. New PET radiopharmaceuticals beyond FDG for brain tumor imaging. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;56:173–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert NL, Weller M, Suchorska B, Galldiks N, Soffietti R, Kim MM, et al. Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology working group and European Association for Neuro-Oncology recommendations for the clinical use of PET imaging in gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:1199–208. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langen KJ, Watts C. Neuro-oncology: amino acid PET for brain tumours—ready for the clinic? Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:375–6. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shinozaki N, Uchino Y, Yoshikawa K, Matsutani T, Hasegawa A, Saeki N, et al. Discrimination between low-grade oligodendrogliomas and diffuse astrocytoma with the aid of 11C-methionine positron emission tomography. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:1640–7. doi: 10.3171/2010.11.JNS10553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glaudemans AW, Enting RH, Heesters MA, Dierckx RA, van Rheenen RW, Walenkamp AM, et al. Value of 11C-methionine PET in imaging brain tumours and metastases. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:615–35. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohtani T, Kurihara H, Ishiuchi S, Saito N, Oriuchi N, Inoue T, et al. Brain tumour imaging with carbon-11 choline: comparison with FDG PET and gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:1664–70. doi: 10.1007/s002590100620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber WA, Wester HJ, Grosu AL, Herz M, Dzewas B, Feldmann HJ, et al. O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine and L-[methyl-11C]methionine uptake in brain tumours: initial results of a comparative study. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:542–9. doi: 10.1007/s002590050541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Floeth FW, Pauleit D, Wittsack HJ, Langen KJ, Reifenberger G, Hamacher K, et al. Multimodal metabolic imaging of cerebral gliomas: positron emission tomography with [18F]fluoroethyl-L-tyrosine and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:318–27. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.2.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pauleit D, Floeth F, Hamacher K, Riemenschneider MJ, Reifenberger G, Müller HW, et al. O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET combined with MRI improves the diagnostic assessment of cerebral gliomas. Brain. 2005;128:678–87. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kratochwil C, Combs SE, Leotta K, Afshar-Oromieh A, Rieken S, Debus J, et al. Intra-individual comparison of 18F-FET and 18F-DOPA in PET imaging of recurrent brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:434–40. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tripathi M, Sharma R, D’Souza M, Jaimini A, Panwar P, Varshney R, et al. Comparative evaluation of F-18 FDOPA, F-18 FDG, and F-18 FLT-PET/CT for metabolic imaging of low grade gliomas. Clin Nucl Med. 2009;34:878–83. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181becfe0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langen KJ, Tonn JC, Weller M, Galldiks N. Letter to the Editor: “The role of imaging in the management of progressive glioblastoma. A systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline” [J Neurooncol 2014;118:435–460] J Neurooncol. 2014;120:665–6. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1594-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomiyoshi K, Amed K, Muhammad S, Higuchi T, Inoue T, Endo K, et al. Synthesis of isomers of 18F-labelled amino acid radiopharmaceutical: position 2- and 3-L-18F-alpha-methyltyrosine using a separation and purification system. Nucl Med Commun. 1997;18:169–75. doi: 10.1097/00006231-199702000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue T, Tomiyoshi K, Higuichi T, Ahmed K, Sarwar M, Aoyagi K, et al. Biodistribution studies on L-3-[fluorine-18]fluoro-alpha-methyl tyrosine: a potential tumor-detecting agent. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:663–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Otani Y, Shimizu K, Tanaka S, Imai H, et al. Fluorine-18-alpha-methyltyrosine positron emission tomography for diagnosis and staging of lung cancer: a clinicopathologic study. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6369–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Shimizu K, Tominaga H, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, et al. 18F-FMT uptake seen within primary cancer on PET helps predict outcome of non-small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1770–6. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.066837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Shimizu K, Ishikita T, Higuchi T, Imai H, et al. Evaluation of thoracic tumors with (18)F-FMT and (18)F-FDG PET-CT: a clinicopathological study. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1152–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyashita G, Higuchi T, Oriuchi N, Arisaka Y, Hanaoka H, Tominaga H, et al. 18F-FAMT uptake correlates with tumor proliferative activity in oral squamous cell carcinoma: comparative study with 18F-FDG PET and immunohistochemistry. Ann Nucl Med. 2010;24:579–84. doi: 10.1007/s12149-010-0398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki S, Kaira K, Ohshima Y, Ishioka NS, Sohda M, Yokobori T, et al. Biological significance of fluorine-18-α-methyltyrosine (FAMT) uptake on PET in patients with oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1985–91. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue T, Shibasaki T, Oriuchi N, Aoyagi K, Tomiyoshi K, Amano S, et al. 18F alpha-methyl tyrosine PET studies in patients with brain tumors. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue T, Koyama K, Oriuchi N, Alyafei S, Yuan Z, Suzuki H, et al. Detection of malignant tumors: whole-body PET with fluorine 18 alpha-methyl tyrosine versus FDG--preliminary study. Radiology. 2001;220:54–62. doi: 10.1148/radiology.220.1.r01jl1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–20. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaschten B, Stevenaert A, Sadzot B, Deprez M, Degueldre C, Del Fiore G, et al. Preoperative evaluation of 54 gliomas by PET with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose and/or carbon-11-methionine. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:778–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato T, Shinoda J, Oka N, Miwa K, Nakayama N, Yano H, et al. Analysis of 11C-methionine uptake in low-grade gliomas and correlation with proliferative activity. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1867–71. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato T, Shinoda J, Nakayama N, Miwa K, Okumura A, Yano H, et al. Metabolic assessment of gliomas using 11C-methionine, [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose, and 11C-choline positron-emission tomography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1176–82. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derlon JM, Petit-Taboué MC, Chapon F, Beaudouin V, Noël MH, Creveuil C, et al. The in vivo metabolic pattern of low-grade brain gliomas: a positron emission tomographic study using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose and 11C-L-methylmethionine. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:276–87. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199702000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langen KJ, Mühlensiepen H, Holschbach M, Hautzel H, Jansen P, Coenen HH. Transport mechanisms of 3-[123I]iodo-alpha-methyl-L-tyrosine in a human glioma cell line: comparison with [3H]methyl]-L-methionine. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1250–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langen KJ, Ziemons K, Kiwit JC, Herzog H, Kuwert T, Bock WJ, et al. 3-[123I]iodo-alpha-methyltyrosine and [methyl-11C]-L-methionine uptake in cerebral gliomas: a comparative study using SPECT and PET. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:517–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi K, Ohnishi A, Promsuk J, Shimizu S, Kanai Y, Shiokawa Y, et al. Enhanced tumor growth elicited by L-type amino acid transporter 1 in human malignant glioma cells. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:493–503. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000316018.51292.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Imai H, Shimizu K, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, et al. L-type amino acid transporter 1 and CD98 expression in primary and metastatic sites of human neoplasms. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2380–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okubo S, Zhen HN, Kawai N, Nishiyama Y, Haba R, Tamiya T. Correlation of L-methyl-11C-methionine (MET) uptake with L-type amino acid transporter 1 in human gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2010;99:217–25. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiriyasermkul P, Nagamori S, Tominaga H, Oriuchi N, Kaira K, Nakao H, et al. Transport of 3-fluoro-L-α-methyl-tyrosine by tumor-upregulated L-type amino acid transporter 1: a cause of the tumor uptake in PET. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1253–61. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.103069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weckesser M, Langen KJ, Rickert CH, Kloska S, Straeter R, Hamacher K, et al. O-(2-[18F]fluorethyl)-L-tyrosine PET in the clinical evaluation of primary brain tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:422–9. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1705-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Habermeier A, Graf J, Sandhofer BF, Boissel JP, Roesch F, Closs EI. System L amino acid transporter LAT1 accumulates O-(2-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (FET) Amino Acids. 2015;47:335–44. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albert NL, Winkelmann I, Suchorska B, Wenter V, Schmid-Tannwald C, Mille E, et al. Early static (18)F-FET-PET scans have a higher accuracy for glioma grading than the standard 20–40 min scans. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1105–14. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldman S, Levivier M, Pirotte B, Brucher JM, Wikler D, Damhaut P, et al. Regional methionine and glucose uptake in high-grade gliomas: a comparative study on PET-guided stereotactic biopsy. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1459–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pirotte B, Goldman S, David P, Wikler D, Damhaut P, Vandesteene A, et al. Stereotactic brain biopsy guided by positron emission tomography (PET) with [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose and [C-11]methionine. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1997;68:133–8. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6513-3_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pirotte B, Goldman S, Massager N, David P, Wikler D, Lipszyc M, et al. Combined use of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose and 11C-methionine in 45 positron emission tomography-guided stereotactic brain biopsies. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:476–83. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.3.0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spaeth N, Wyss MT, Weber B, Scheidegger S, Lutz A, Verwey J, et al. Uptake of 18F-fluorocholine, 18F-fluoroethyl-L-tyrosine, and 18F-FDG in acute cerebral radiation injury in the rat: implications for separation of radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1931–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Laere K, Ceyssens S, Van Calenbergh F, de Groot T, Menten J, Flamen P, et al. Direct comparison of 18F-FDG and 11C-methionine PET in suspected recurrence of glioma: sensitivity, inter-observer variability and prognostic value. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:39–51. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1564-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pauleit D, Stoffels G, Bachofner A, Floeth FW, Sabel M, Herzog H, et al. Comparison of (18)F-FET and (18)F-FDG PET in brain tumors. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:779–87. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lau EW, Drummond KJ, Ware RE, Drummond E, Hogg A, Ryan G, et al. Comparative PET study using F-18 FET and F-18 FDG for the evaluation of patients with suspected brain tumour. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plotkin M, Blechschmidt C, Auf G, Nyuyki F, Geworski L, Denecke T, et al. Comparison of F-18 FET-PET with F-18 FDG-PET for biopsy planning of non-contrast-enhancing gliomas. Euro Radiol. 2010;20:2496–502. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1819-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyake K, Shinomiya A, Okada M, Hatakeyama T, Kawai N, Tamiya T. Usefulness of FDG, MET and FLT-PET studies for the management of human gliomas. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:205818. doi: 10.1155/2012/205818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tripathi M, Sharma R, Varshney R, Jaimini A, Jain J, Souza MM, et al. Comparison of F-18 FDG and C-11 methionine PET/CT for the evaluation of recurrent primary brain tumors. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37:158–63. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318238f51a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galldiks N, Langen KJ. Applications of PET imaging of neurological tumors with radiolabeled amino acids. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;59:70–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calcagni ML, Galli G, Giordano A, Taralli S, Anile C, Niesen A, et al. Dynamic O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (F-18 FET) PET for glioma grading: assessment of individual probability of malignancy. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:841–7. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182291b40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moulin-Romsee G, D’Hondt E, de Groot T, Goffin J, Sciot R, Mortelmans L, et al. Non-invasive grading of brain tumours using dynamic amino acid PET imaging: does it work for 11C-methionine? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:2082–7. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0557-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]