Abstract

The accumulation of damaged or excess proteins and organelles is a defining feature of metabolic disease in nearly every tissue. Thus, a central challenge in maintaining metabolic homeostasis is the identification, sequestration, and degradation of these cellular components including protein aggregates, mitochondria, peroxisomes, inflammasomes, and lipid droplets. A primary route through which this challenge is met is selective autophagy, the targeting of specific cellular cargo for autophagic compartmentalization and lysosomal degradation. In addition to its roles in degradation, selective autophagy is emerging as an integral component of inflammatory and metabolic signaling cascades. In this review, we focus on emerging evidence and key questions about the role of selective autophagy in the cell biology and pathophysiology of metabolic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and steatohepatitis. Essential players in these processes are the selective autophagy receptors, defined broadly as adapter proteins that both recognize cargo and target it to the autophagosome. Additional domains within these receptors may allow integration of information about autophagic flux with critical regulators of cellular metabolism and inflammation. Details regarding the precise receptors involved, such as p62 and NBR1, and their predominant interacting partners are just beginning to be defined. Overall, we anticipate the continued study of selective autophagy will prove informative in understanding the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases and to provide previously unrecognized therapeutic targets.

Introduction

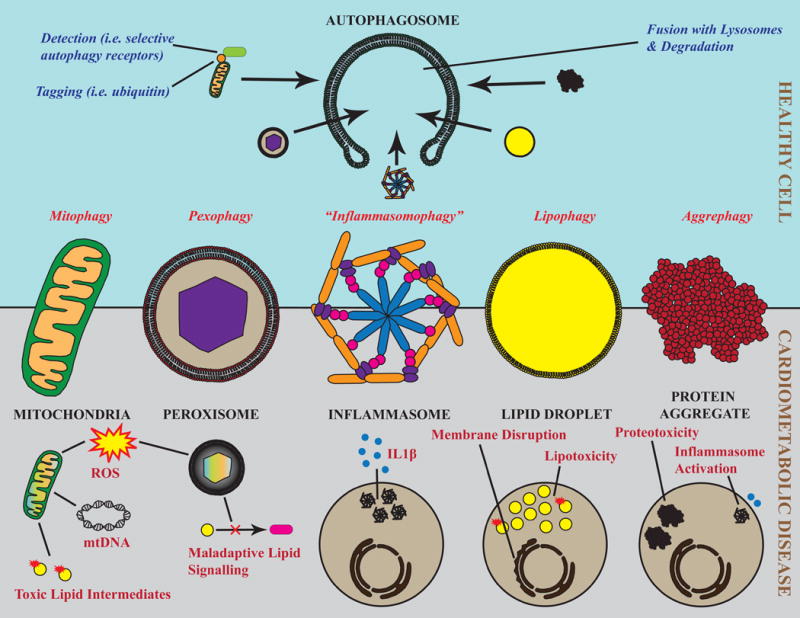

Presently, the most widespread and fastest growing threat to public health is the constellation of epidemiologically associated and mechanistically intertwined cardiometabolic diseases including obesity, diabetes, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and associated cardiovascular complications of atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure (1). A consistent, unifying mechanism of metabolic dysfunction is an inability of cells to appropriately degrade proteins and organelles, resulting in their accumulation (Figure 1). The accumulation of these defective or excess cellular components including protein aggregates, mitochondria, lipid droplets, peroxisomes, and inflammasomes not only represents organelle-intrinsic failure, but also perpetuates cellular dysfunction through the buildup of potentially maladaptive signals including reactive oxygen species (ROS), proinflammatory cytokines, and lipid intermediates. In turn, the importance of degradation is twofold: first to limit overt accumulation of dysfunctional or aging organelles, and second to dampen the impact of signals generated by organelles (Figure 2). Thus, a longstanding area of investigation lies in characterizing the systems that cells use to identify and degrade dysfunctional cellular components to maintain metabolic homeostasis. Two primary machineries serve this goal: the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy. Although the UPS is pivotal to overall protein turnover and cell signaling, it primarily targets smaller and short-lived protein substrates and becomes overwhelmed in disease scenarios (2, 3). Autophagy can be subdivided into several subtypes, which have been described elsewhere (4, 5). In macroautophagy, larger protein or organelle substrates are sequestered by a double-membrane phagophore, which extends to form a mature autophagosome. The autophagosome then fuses with an acidic lysosome, where diverse hydrolases mediate degradation to yield basic biological substrates. “Bulk” macroautophagy refers to nonselective mass degradation of cytosolic components under conditions such as starvation with the primary goal of recycling to generate nutrients. In contrast, selective autophagy is the coordinated tagging, autophagic sequestration, and degradation of specific protein and organelle substrates (6). This specificity of degradation makes selective autophagy important in limiting and correcting the cellular dysfunctions for which no other pathway can compensate. In this review, we explore how selective autophagy impacts the physiology of cell and organismal metabolism, giving particular consideration to its roles in modulating the pathogenesis of cardiometabolic disease.

Figure 1. Accumulation of Dysfunctional Organelles in Cardiometabolic Disease.

Organelle accumulation and dysfunction is a common feature of cardiometabolic diseases in nearly every tissue and cell type including hepatocytes, macrophages, myocytes, cardiomyocytes, pancreatic islet β-cells, and adipocytes. Specific players include lipid accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, protein aggregation, inflammasome activation, and peroxisome dysfunction.

Figure 2. Selective Autophagy Degrades Dysfunctional or Excess Organelles.

In cardiometabolic disease states, dysfunctional and/or excess organelles produce adverse signals that mediate disease pathology. Mitochondria and peroxisomes produce reactive oxygen species, and mitochondria additionally release mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and incompletely oxidized lipid intermediates. Activated inflammasomes produce massive amounts of IL-1β. Lipid droplets are a relatively safe storage site for neutral lipids; their saturation results in lipotoxicity, ectopic lipid deposition, and membrane disruption. Protein aggregates are both inherently cytotoxic (proteotoxicity) and can activate inflammasomes as an example of pathological intraorganelle crosstalk (Bottom). Selective autophagy is a primary mode of degradation for each of these types of organelles and serves to both maintain intrinsic organelle function and limit toxic byproducts. Archetypal steps in selective autophagy include tagging of dysfunctional or excess cargo (for example, by ubiquitin), recognition by selective autophagy receptors (e.g. p62), delivery to the autophagosome, and fusion with the lysosome for complete degradation (Top).

Molecular Basis of Selective Autophagy

The molecular details of downstream events in autophagy after selectivity is established, including phagophore assembly, membrane elongation, and fusion with the lysosome for degradation can be found in various comprehensive reviews and glossaries (4, 5, 7). The molecular basis of selective autophagy lies in how specific organelles or proteins are exclusively tagged and targeted to the autophagic machinery (Figure 2). Ubiquitination seems to be the predominant mechanism of tagging, is shared with proteasomal degradation, and features a complex set of E1, E2, and E3 ligases involved in conjugating proteins and organelles. Ubiquitin monomers also self-oligimerize into lysine-linked polyubiquitin chains. The particular ubiquitin lysine residue bound determines chain structure and serves as a point of control for further specificity. Monoubiquitination, or polyubiquitination involving residues Lys27 and Lys63, targets cargo to the autophagosome (as in macroautophagy) or directly to the lysosome (as in microautophagy) (6). In contrast, Lys48 polyubiquitin chains are a potent signal for proteasomal degradation (8). Therefore, the molecular events that dictate ubiquitination are crucial for conferring specificity at the initiation of selective autophagy. Next, a small but growing class of adapter molecules known as the selective autophagy receptors feature structural domains that recognize cargo, often through a ubiquitin binding domain, and a means of initiating or binding to the autophagic machinery, such as a MAP1 light chain 3 (LC3)-binding domain. Prominent members of this family include p62, Neighbor of BRCA1 (NBR1), Nuclear Dot Protein 52 (NDP52), and Optineurin (OPTN). Through combinatorial arrangements of different cargo, ubiquitination, and selective autophagy receptors, highly regulated and specific autophagy can be achieved. The exact contributions of particular ubiquitination events and autophagy receptors in targeting organelles under various conditions are just beginning to be unraveled. Additionally, cases are emerging in which noncanonical means of selective cargo recognition (“precision” autophagy) or autophagic processing (chaperone-mediated or microautophagy) take precedence in mediating selective autophagic degradation. Overall, the impact of selective autophagy on metabolic homeostasis and disease progression can best be conceptualized at the level of the substrate, mainly, specific organelles (Figure 2). Directly implicating selective autophagy in physiological disease processes is experimentally daunting due to the multifaceted roles of selective autophagy receptors in cell signaling, redundancy, and the persistent lack of understanding of the molecular processes involved. However the combined evidence consisting of accumulation of dysfunctional organelles in disease states, pathologies observed in selective autophagy-deficient disease models, and beneficial effects of driving autophagy together make a compelling case for its importance. We discuss how organelles important to metabolism are specifically processed through selective autophagy, how modification of selective autophagy in turn impacts their function, and how these processes contribute to cardiometabolic disease pathology and protection.

Aggrephagy

Protein inclusions are formed when the cellular ability to degrade aggregation-prone damaged or misfolded proteins is overwhelmed. Nascent, smaller protein aggregates are particularly cytotoxic due to a preponderance of reactive side chains (9). Thus, an additional adaptive cellular response to aggregate formation is the coalescence of such protein masses into higher-order structures including inclusion bodies and the aggresome (10). While classically associated with neurodegenerative diseases, accumulation of protein aggregates has also been observed in nearly every cardiometabolic disease (Figure 1). Enter aggrephagy – the degradation of protein inclusions through selective autophagy. Aggrephagy is thought to have a nearmonopoly on aggregate degradation due to their size and complexity, and aggregates themselves halt proteasomal function (11). Several well established molecular details (12) are informative to understanding the procession of aggrephagy (Figure 3) and are either confirmed or likely to participate in the degradation of specific inclusions found in cardiometabolic diseases.

Figure 3. Models of Key Molecular Events Mediating Pexophagy, Aggrephagy, and Inflammasomophagy.

A. Pexophagy: Mammalian pexophagy primarily proceeds through Pex2-mediated ubiquitination of Pex5. NBR1 serves as the main selective autophagy receptor for peroxisomes that mediates interaction with the autophagosome. B. Aggrephagy: CHIP and Parkin are the main E3 ubiquitin ligases that target protein aggregates and inclusions. NBR1, p62, and ALFY interact with the autophagosome to mediate aggrephagy. C. Inflammasomophagy: Inflammasomes are targeted for autophagic destruction through at least two routes. A mechanism termed “precision” autophagy involves direct recognition of multiple inflammasome components by TRIM20 (also known as MEFV) which recruits key components of autophagy machinery such as Beclin, ULK1, and ATG8 (top). Alternatively, upon polyubiquitination of the ASC subunit by a yet to be identified E3 ligase, the inflammasome is recognized by p62 for autophagy (bottom).

Newly formed aggregates of misfolded or damaged proteins are first recognized by members of the heat-shock protein family. E3-ubiquitin ligases including C-terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP) or Parkin then cooperate with heat shock proteins to ubiquitinate cargo (13, 14). Cargo can take on two distinct types of structures. Aggresomes are localized to the microtubule organizing center and depend on ordered cytoskeletal delivery of substrates. A separate type of formed aggregate is microtubule-independent and referred to as an aggresome-like inducible structure or inclusion body. Ubiquitinated substrate can be recognized by histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) for microtubule-mediated delivery (14), or alternatively, a ubiquitin-independent pathway involving (Bag3) cargo recognition can also route damaged proteins to the aggresome (15,16). In any case, p62 is essential for aggregate formation (17–19) and its ubiquitin binding domain is required for this process and downstream sequelae (19, 20). Finally, p62 cooperates with NBR1 and a downstream adapter protein ALFY (21) to mediate interaction of mature aggregates with the autophagic machinery (Figure 3) (12).

The role of aggrephagy in limiting protein aggregate toxicity is evident in cardiometabolic disease states, and even more so in autophagy-deficient disease models. In each case, it is worth considering that aggregate formation is in itself likely a protective response against proteotoxicity until clearance can occur. For example, Mallory-Denk bodies (MDBs, also known as Mallory bodies) are aggregates of the intermediate filament keratin enriched with ubiquitin and p62 and are classically found in alcoholic liver disease but have also been reported in the hepatocytes of patients with non-alchoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (22). MDB formation correlates with markers of inflammation in human NAFLD and can be used as a histological marker of disease progression to the more serious steatohepatitis (23–25). Ultimately, a chief concern in the management of NAFLD is the eventual progression to hepatocellular carcinoma. The accumulation of p62 and MDB are fundamental drivers in this process, (26) and are limited by autophagic removal (27). The specific players involved in aggrephagy of MDBs remain elusive, though examination of MDB formation and hepatosteatotic phenotypes in the settings of autophagy and/or p62 deficiency has given preliminary insight. Broad disruption of autophagy consistently leads to severe liver pathology (18, 28, 29) and buildup of p62-inclusion bodies (18, 28), indicating a role for constitutive aggrephagy in their clearance. Intriguingly, p62 deficiency partially abrogates the hepatic pathology induced by autophagy deficiency (18, 30), perhaps because of the many signaling roles of p62 (31). Several investigations have unveiled further complexity in the contribution of p62 signaling to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, in which p62 is proposed to be tumor suppressive in liver stellate cells and oncogenic in hepatocytes (32, 33). p62-deficiency alone does not cause overt hepatic dysfunction (18, 34) nor does it modulate removal of MDBs during recovery after drug-induced insult (35). Overall, it should be emphasized that p62 is important for aggregate formation(35), has important roles in cell signaling, and is cleared by autophagy, but does not seem to be a primary adapter recruiting the autophagy machinery to MDBs. Identification of the receptors specifically involved in MDB clearance will be useful in understanding NAFLD pathophysiology.

A second prominent role for aggrephagy in cardiometabolic disease is in the clearance of the islet amyloid polypeptide (iAPP). iAPP is somewhat distinct from typical aggregate contents in that it self-oligomerizes into cytotoxic beta sheets and amyloid fibrils. In type 2 diabetes, iAPP accumulation initiates proteotoxicity and membrane disruption leading to pancreatic beta cell dysfunction (36). iAPP is also found in distal sites such as the heart, where it can induce oxidative stress and contractile dysfunction (37, 38). Rivera et al. have previously shown that iAPP itself induces autophagy-lysosomal dysfunction (39), and have suggested that p62-mediated activation of the transcription factor NRF2 is protective in this setting (40). A crucial role for aggrephagy in iAPP homeostasis has been established by a trio of studies showing that iAPP is protectively sequestered in ubiquitin- and p62-enriched aggregates which are subsequently cleared by aggrephagy. Autophagy deficiency greatly exacerbates pancreatic beta cell dysfunction and diabetes progression (40–42). In addition, Kim et al. have demonstrated that trehalose, an autophagy-inducing disaccharide, can specifically induce clearance of iAPP aggregates and rescue diabetic pathology (41). In the context of atherosclerosis, we and others have observed p62 and ubiquitin-tagged protein inclusions in murine and human atherosclerotic lesions (3, 79, 43), and note that these structures are associated with plaque instability and acute coronary syndromes in human disease (44). The etiology and contents of these aggregates is mostly unknown, but candidates include extensively modified LDL and ApoB (45, 46), perhaps a result of failed lysosomal degradation after initial endocytic uptake (47). In contrast to others’ findings in the liver (18), we have found that the formation of p62 aggregates in autophagy-deficient macrophages is broadly protective, and limits aggregate-induced inflammasome activation and overall atherosclerotic progression (19). Overall, selective autophagy serves to limit the toxicity of protein aggregates observed in many cardiometabolic diseases.

Autophagic Degradation of Inflammasomes by “Inflammasomophagy”

The inflammasome is a large, oligomeric protein complex that produces inflammatory cytokines in a two-step process. Classic inflammatory pathways such as Toll-like receptor activation and subsequent NF-κB signaling prime transcription and translation of the precursor forms of IL-1β and IL-18 peptides (pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18). Second, damage-associated molecular patterns, such as cholesterol crystals and reactive oxygen species (ROS), trigger inflammasome formation which leads to caspase-1 activation and selective cleavage of the interleukin pro-peptides to active IL-1β and IL-18. These inflammasome products, which are generated primarily by macrophages (48–57), act locally and systemically on target cells to promote cell death, insulin resistance, and vascular dysfunction, and are implicated in nearly every human cardiometabolic disease state (Figure 1) (52–55). A crucial aspect of inflammasome regulation was first detailed by Shi and colleagues, who showed inflammasomes are Lys63 polyubiquitinated on the ASC subunit and targeted to the autophagosome through p62 acting as the primary selective autophagy receptor (56). This type of selective autophagy is also activated by inflammatory signaling cascades and serves as a crucial molecular brake to limit inflammation(56, 57). The modes of inflammasome regulation by selective autophagy are ripe for investigation. Kimura et al. (58) describe a second, alternative mechanism of inflammasome clearance through autophagy. The selective autophagy receptor tripartite motif-containing 20 (TRIM20, also known as Mediterranean Fever, MEFV) recognizes inflammasome components including Nod-like Receptor protein -1 (NLRP1), NLRP3, and caspase-1 independent of ubiquitination, and uniquely serves as a platform to spur autophagy through the recruitment of Beclin-1, ULK1, and ATG8 (58). This mechanism contrasts with the binding of other autophagy receptors to ubiquitin and LC3, and is termed “precision autophagy” owing to the direct, ubiquitin-independent recognition of specific cargo (59, 60). Particularly fascinating is the impaired autophagic clearance of inflammasomes associated with common mutations in the MEFV gene found in patients with Familial Mediterranean Fever (58). This relatively common genetic disorder results in IL-1β hypersecretion (61) and increased atherogenesis (62, 63). We believe these studies collectively constitute sufficient evidence to distinguish autophagic clearance of inflammasomes from “bulk” autophagy and propose the term “inflammasomophagy” to refer to this selective process (Figure 3).

Direct assessment of the role of inflammasomophagy in common cardiometabolic diseases thus far is sparse, but studies in other settings suggest the relevance of this process to interleukin secretion from macrophages and progression of pathology in Gaucher disease (64), burn-wound healing (65), and neuroinflammation (66). A broader role for autophagy (and selective autophagy) in dampening cardiometabolic disease-associated inflammasome activity is, however, well established. In atherosclerosis, lack of autophagy in macrophages greatly potentiates disease progression and is associated with increased IL-1β in the aorta and in peritoneal macrophages treated with cholesterol crystals (19, 67). Further, the effects of autophagy deficiency on inflammation are inflammasome-specific, because other proinflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and interleukin-10 are unaffected by autophagy deficiency (67). In a parallel setting, IL-1β is increased in adipose tissue macrophages from obese autophagy-insufficient mice and in cultured macrophages treated with palmitic acid (68). Third, macrophage autophagy deficiency increases susceptibility to liver fibrosis in a manner specifically dependent on increased IL-1β production (69). We have provided evidence that directly implicates inflammasomophagy in cardiometabolic disease(19). First, NLRP3 inflammasomes in macrophages treated with atherosclerotic stimuli are ubiquitinated and tagged with p62. Deficiency of p62, as predicted, results in inflammasome accumulation and increased IL-1β secretion which is likely and partially due to failure to clear inflammasomes. p62 is a multifunctional scaffold protein that interacts with many metabolic and inflammatory cell signaling pathways. In this case, we have shown that inhibition of nuclear respiratory factor -2 (NRF2), extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK), p38, or NF-kB signaling does not affect the increased IL-1β secretion from p62-deficient macrophages. However, specific loss of the p62 ubiquitin binding domain is sufficient to mimic total p62 deficiency’s effects on IL-1β secretion, suggesting a primary importance of p62’s roles in aggregating and clearing ubiquitin-tagged targets. Overall, the lack of the selective autophagy receptor p62 in macrophages allows accumulation of inflammasomes and consequently increases IL-1β secretion and atherogenesis in mice.

Complementary possibilities beyond direct clearance of inflammasomes may partially explain why selective autophagy limits IL-1β production. First, mitochondrial ROS are a potent inflammasome-activating danger signal such that clearance of mitochondria (mitophagy) and associated reductions in ROS may explain lower IL-1β (57, 70, 71). Conversely, it should be noted that the interaction between mitochondria and inflammasome activation is not unidirectional. Inflammasome activation damages mitochondria, halts mitophagy, and initiates cell death in a process termed pyroptosis (72). Zhong et al. have shown that activation of NF-kB-inflammasome signaling is limited by concurrent NF-kB transcription of p62, which acts to induce mitophagy and limit inflammasome activation. This finding supports the concept that selective autophagy acts as a brake on proinflammatory signal transduction. Additionally, pro-IL-1β is degraded through autophagy, potentially limiting the availability of this precursor substrate (73). However, we should note that there appears to be a complex role for autophagy in targeting IL-1β itself. IL-1β lacks a signal sequence for classical secretion and instead is released through an alternative vesicular route (74). Autophagy has also been proposed to facilitate IL-1β trafficking through this mechanism, potentially leading to enhanced IL-1β secretion under certain conditions (75, 76). The in vivo relevance and underlying mechanisms require additional study, but a potential route involves heat shock protein-90 (Hsp90)-mediated translocation of IL-1β into autophagic vesicle intermediates before secretion (76). Other non-autophagic mechanisms of release such as microvesicle shedding or overt disruption of the plasma membrane during cell death (77) are likely more relevant such that the net impact of autophagy deficiency on IL-1β is still hyper-production and secretion in most autophagy-deficient settings. Although reduced autophagy and increased inflammasome activity are independently linked to the development of cardiometabolic disease, specific genetic or pharmacological manipulations are needed to precisely determine the ways in which inflammasomophagy regulates IL-1β and influences downstream physiological sequelae.

Pexophagy

Peroxisomes are multifunctional organelles with underappreciated roles in lipid metabolism and reactive oxygen species signaling (78). Diverse classes of signaling lipids are degraded or synthesized at least in part by peroxisomes, including bile acids (79), ether lipids (80), and leukotrienes (81). Many of these compounds are ligands for nuclear hormone receptors that activate transcription to profoundly alter cellular metabolism. Peroxisomes also have major roles in ROS metabolism. Many peroxisomal enzymes produce ROS as normal metabolic byproducts, which have homeostatic signaling roles, and the high peroxisomal abundance of the antioxidant enzyme catalase balances their impact. Peroxisomal ROS crosstalk with mitochondrial and cytosolic ROS signaling (82) and are also thought to generally be in excess in cardiometabolic diseases (83). Peroxisome volume is responsive to environmental stimuli such as increased fatty acid bioavailability, and damaging ROS production may be a consequence of peroxisome biogenesis (83, 84). Aging, perhaps the most important risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases, also nearly universally features an accumulation of dysfunctional peroxisomes (85). Clearly, tight regulation of peroxisome homeostasis has major implications for the development of cardiometabolic disease.

Pexophagy is the autophagic degradation of peroxisomes and is exclusively responsible for their clearance (86, 87). The most promising mammalian ubiquitination target that facilitates pexophagy is the import receptor Pex5 (88). Zhang et al. (89) have identified a regulatory cascade in which ROS stimulate the kinase ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) to phosphorylate Pex5, which increases its ubiquitination. In tandem, ROS signal to ATM to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) at the peroxisome to broadly stimulate autophagy and provide the autophagy machinery needed for pexophagy (89, 90). Nordgren et al. (91) propose a different monoubiquitination site on Pex5 in mediating pexophagy but integrate this function with the primary function of Pex5 in importing peroxisomal membrane proteins. They suggest that the dysfunctional matrix import that is observed in disease states (92, 93) stabilizes ubiquitinated Pex5 at the peroxisomal membrane to favor pexophagy, consistent with models favored by computational analysis (94). E3 ubiquitin ligases present at the peroxisome that could target Pex5 include Pex2, Pex10, and Pex12, and their action may be opposed by ubiquitin-specific protease 9x (USP9x)-mediated deubiquitination (95). Sargent et al. specifically propose Pex2 as the predominant ubiquitin ligase for pexophagy during starvation and confirmed Pex5 as a key target (Figure 3) (96). Finally, what are the primary selective autophagy adapter proteins that mediate pexophagy? Deosaran et al. (97) have established that NBR1, but not p62, is sufficient and necessary for mammalian pexophagy through its binding of ubiquitinated Pex5 (Figure 3). The importance of NBR1 has been verified in physiological settings including hypoxia-induced hepatocyte pexophagy (98) and starvation-induced pexophagy (96). However, p62 is still found at ubiquitinated peroxisomes and may facilitate interaction of NBR1 with the peroxisome and/or autophagy machinery (89, 96, 97). Like mitochondria, peroxisomes are spatially dynamic organelles and undergo Pex11-mediated fission (99). This process is essential for pexophagy in yeast and occurs only in peroxisomes in contact with mitochondria (100).

Overall, it can be posited that pexophagy acts to limit peroxisomal β-oxidation capacity, signaling lipid generation, and ROS generation, especially in the case of dysfunctional peroxisomes. First, there are several scenarios in which peroxisome biogenesis is thought to be a generally adaptive response, and coincident pexophagy may limit or reverse induced changes. Characterization of drugs that stimulate peroxisome biogenesis (101) has led to the discovery of the peroxisomal proliferator-actived receptor (PPAR) nuclear hormone receptor family, which are both the targets of peroxisome-generated ligands (80) and inducers of peroxisome biogenesis amongst many other pleiotropic effects. The PPARs have been widely targeted using the fibrate and thiazolidinedione (TZD) classes of drugs for their lipid lowering, insulin-sensitizing properties, which are likely partially attributable to effects on peroxisomes (102,103). Pexophagy is responsible for clearing peroxisomes upon withdrawal of a peroxisome proliferator (87), and may act to maintain the integrity of drug-stimulated peroxisomes such that they are a sink rather than source for ROS.

Pexophagy also likely participates in regulation of adipocyte phenotypes. A major focus of adipocyte biology involves the understanding of adipose tissue browning (the conversion of white adipocytes to “beige” adipocytes which are rich in energetically uncoupled mitochondria) to induce negative whole-body energy balance to treat metabolic diseases (104). Peroxisome biogenesis is characteristic of adipose tissue browning, and is likely necessary to meet the massive β-oxidation demands of brown adipose tissue (105). Adipocyte-specific autophagy deficiency protects against diet induced obesity and metabolic sequelae by inducing a brown adipocyte-like phenotype (106). This effect has been attributed to impaired mitophagy and accumulation of mitochondria, but the accumulation of peroxisomes due to impaired pexophagy could also play a role.

Peroxisome-derived oxidative stress contributes to the pathology of various cardiometabolic disease scenarios including diabetic renal injury (107), lipid induced pancreatic beta cell dysfunction (84), and aging (85). It will be of great interest to examine whether the in vitro findings regarding peroxisomal fission and ATM-mediated sensing of ROS translate to these settings. Beyond these preliminary discussions of how peroxisomes are involved in cardiometabolic diseases and regulated by pexophagy, several studies illustrate how disruption or elimination of pexophagy is severely detrimental to metabolism. Ablation of any of the key peroxisomal players in pexophagy (Pex2, Pex5, and Pex11) results in severe metabolic perturbations (99, 108, 109), though unfortunately the other essential roles of these proteins preclude drawing the strict conclusion that phenotypes arise from altered pexophagy. One last setting in which pexophagy is likely to be relevant is in the liver, where peroxisomes are particularly abundant. Obesity induced by a high-fat diet further enhances the biogenesis of ROS-producing peroxisomes in the liver (110). Predictably, liver-specific autophagy deficiency results in massive peroxisome accumulation (86) though oxidative damage and steatosis are difficult to separate from effects on mitophagy or lipophagy. Overall, more specific experimental manipulations of pexophagy are needed to fully understand its role in cardiometabolic diseases with an emphasis on understanding how peroxisomes become dysfunctional and how the generation of peroxisome-specific ROS and lipid species is altered.

Mitophagy

Of the organelles targeted for selective autophagy, mitochondria have the most straightforward impact on cellular energy metabolism and cardiometabolic disease phenotypes. Mitochondria produce ROS as a normal byproduct of their essential roles in β-oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation to produce ATP. However, mitochondrial dysfunction including ROS overproduction is implicated in cardiometabolic disease pathologies including atherosclerosis (111), cardiomyopathy (112, 113), vascular endothelial dysfunction (114) and diabetes (115). Mitochondrial ROS adversely modify lipids, proteins, and mitochondrial DNA, with the net effect of impaired ATP production and propagation of further dysfunction. Mitochondrial DNA itself is also released into the cytoplasm, promoting inflammation and cell death (116,117), and incomplete β-oxidation from lipid-overloaded mitochondria can generate toxic lipid intermediates and consequent insulin resistance (118) (Figure 2). Attention has turned to restoring mitochondrial bioenergetics to limit the impact of ROS and other toxic mitochondrial byproducts.

Mitophagy is the selective autophagic clearance of mitochondria and great progress has been made in understanding the various modes of its regulation and procession. First, it is important to conceptualize mitochondria as highly dynamic, networked organelles wherein morphology dictates function. Regular rounds of fission segregate mitochondria by membrane potential (119), constituting an integrative set point for functionality that correlates positively with ATP generating capacity and inversely with cumulative damage. Of the mitochondria segregated by fission, those with adequate membrane potential re-fuse with the mitochondrial network, where elongated morphology maximizes ATP synthesis efficiency. In contrast, fissiongenerated mitochondrial fragments with borderline or low membrane potential exist in a transient state with the potential for delayed fusion or autophagic degradation (120). Cellular nutrient excess, as found in cardiometabolic disease states, is also associated with fragmented mitochondria which likely constitutes a protective response that favors both lower oxidation efficiency to burn extra substrate and to steer damaged mitochondria towards degradation (120). From here, several integrative molecular processes may mediate mitophagy. PINK1 mediates one mode of this next step; in healthy mitochondria it is constitutively imported in a membranepotential dependent manner and degraded by the protease presenilins-associated rhomboid-like (PARL) at the inner membrane (121). However, import is inhibited in dysfunctional mitochondria, leading to accumulation of PTEN-induced putative kinase-1 (PINK1) at the outer membrane where its kinase activity recruits the lynchpin E3 ubiquitin ligase for mitophagy, Parkin (Figure 4) (122). The mitochondrial ubiquitination targets of Parkin are widespread, and it is generally not understood whether ubiquitination of any particular protein carries special import (123). Further, Parkin-mediated ubiquitination is opposed by the deubiquitinase USP30, serving as a last point of control to spare salvageable mitochondria from mitophagy (123,124). Analysis of mitophagy in HeLa cells by several groups have suggested the particular importance of the selective autophagy receptors OPTN and NDP52 (125,126), whereas p62 seems to be more critical for mitochondrial clustering (127). Lazarou et al. have identified a parallel mode of PINKl-mediated mitophagy in which PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to recruit OPTN and NDP52, which in turn recruit the autophagy initiation machinery including ULK1 (Figure 4) (125). However, the universality of these findings may be limited as p62 is a main mediator of mitophagy in both macrophages (57) and cardiomyocytes (128). Another mode of targeting mitochondria is through the selective autophagy receptor Bcl2-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) and the related BNIP3L (also known as NIX) (129). The roles of BNIP3 and BNIP3L are complex, because they are implicated both in apoptotic cell death by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and in mediating protective mitophagy (130, 131). Other additions to the growing family of proteins and pathways that mediate mitophagy include the Fanconi Anemia proteins (132), FUNDC1(133) and the selective autophagy receptor AMBRA1 (134). The task to determine the mitophagy pathways that are most relevant and targetable in cardiometabolic disease settings is ongoing and of great interest.

Figure 4. Model of Key Molecular Events That Mediate Mitophagy.

Mitophagy likely proceeds through several complementary mechanisms. Left: In response to mitochondrial damage, PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to directly enhance NDP52 and OPTN binding. NDP52 and OPTN recruit several components of the autophagy machinery including ULK1 to initiate mitophagy. Bottom: PINK1 also activates the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin, which targets many mitochondrial proteins. The deubiquitinase USP30 opposes Parkin to spare lessdamaged mitochondria. Selective autophagy receptors for mitophagy include NDP52, OPTN, and p62. Right: BNIP3 family proteins in the mitochondrial outer membrane directly mediate mitophagy by binding to LC3. Center: Polyubiquitin/p62 oligomers cluster damaged mitochondria to favor mitophagy.

With the understanding that mitochondrial dysfunction is a ubiquitous feature of cardiometabolic diseases, many studies have begun to more directly characterize mitophagy as a modulator of pathology. First, decreases in skeletal muscle mass, function, and insulin sensitivity are implicated in the progression of metabolic disease such that the maintenance of mitochondrial function is particularly important in this highly metabolically active tissue. Broad skeletal muscle-specific autophagy deficiency results in accumulation of aberrant mitochondria that coincides with atrophied myofibrils and losses in muscle mass and function (135). The impact of this phenotype on systemic metabolism is somewhat surprising; compensatory induction of the integrated stress response in muscle results in enhanced secretion of the mitokine fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF-21) (136). In agreement with previous murine models of FGF-21 induction (137), adipose tissue browning and increased insulin sensitivity have been observed in muscle-specific autophagy deficient mice in the short term. However, these phenotypes are commonly observed in cachexic mice and must be weighed against the likely adverse long term consequences of impaired muscle mitophagy. Loss of Estrogen Receptor α (ERα) signaling, which potently stimulates mitophagy in skeletal muscle, results in mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance, and obesity in mice. These results implicate reduced skeletal mitophagy as a potential driver of insulin resistance and adiposity in postmenopausal women (138). In a more direct characterization of skeletal muscle mitophagy, Drew et al. have identified heat-shock protein 72 (HSP72) as a mitochondrial stress sensor that cooperates with Parkin to induce mitophagy (139). Loss of HSP72 or Parkin impairs skeletal muscle mitophagy, insulin sensitivity, and fatty acid oxidation (139). Surprisingly, systemic Parkin-deficient mice overall are protected against high fat diet induced obesity and insulin resistance because Parkin promotes CD36-mediated lipid transport, which appears to outweigh the impact of any mitophagy defects in the short term (140). Alternatively, the mitophagy deficits induced by systemic Parkin knockout result in impaired glucose tolerance in the context of streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes (141). A second setting in which mitophagy may play important protective roles is in the vascular endothelium. Endothelial cells isolated from diabetic patients feature fragmented mitochondria (142), increased oxidative stress (143), and impaired autophagic flux (144). Impaired autophagy (145) also coincides with increased mitochondrial oxidative stress (114) in the aging aortic endothelium. In either of these settings, pharmacological stimulation of autophagy, likely in great part through clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria, reduces ROS production and rescues vascular dysfunction (144, 145).

The role of mitophagy is perhaps best characterized in the setting of cardiomyopathy. Deficiency of many mediators of mitochondrial dynamics or mitophagy, including Opal (146), Mfn2 (147), and PINK1 (148), result in overt heart failure. Montaigne et al. have shown that cardiomyocytes isolated from human diabetic patients display reduced oxidative capacity, increased superoxide production, reduced ATG5, and fragmented mitochondria. Many of these markers of impaired mitophagy or mitochondrial dysfunction are associated with the severity of diabetes (as gauged by hemoglobin A1c levels) and reduced cardiac contractile function (149).

In brown and beige adipocytes, mitophagy is again important for maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis, but also reduces the abundance of metabolically beneficial uncoupled mitochondria. Mice with adipocyte-specific autophagy deficiency accumulate mitochondria in adipocytes and adopt a multilocular “beige” adipocyte-like morphology (106, 150). While these mice are resistant to typical sequelae of diet-induced obesity, a large portion of the phenotype may be due to vastly increased physical activity (106), and the mice are generally cachexic with early mortality (150). Further, the interpretation of these studies is complicated by the use of AP2-Cre to abrogate adipocyte autophagy; AP2 is now known to target many nonadipocyte tissues (151, 152). Additional studies have clarified the role of mitophagy in adipocytes. Altschuler-Keylin et al. have shown that upon withdrawal of classical “beigeing” stimuli, beige adipocytes rapidly reacquire a white adipocyte phenotype in a mitophagy-dependent manner. A more precise murine model was used to characterize the effects of adipocyte-specific autophagy deficiency using UCP1). This model revealed no profound baseline phenotype, but prolonged β-adrenergic agonist induced adipocyte “beiging”, enhanced energy expenditure, and reduced adiposity in response to high fat diet (153). A second study has identified BNIP3 as a crucial mechanistic mediator of mitophagy in adipocytes. BNIP3 is a prominent target of PPARϒ, the transcription factor that is the master regulator of adipogenesis and mediator of many pharmacological effects of TZDs. Further, adipocyte BNIP3 abundance was increased in several murine models of obesity while BNIP3-deficiency predisposed mice to insulin resistance and NAFLD. Mitochondria from adipocytes from these mice are more elongated, have lower respiration, and have increased superoxide production (154). Lastly, p62 disruption in adipocytes results in compromised mitochondrial structure and function, suggesting its involvement in adipocyte mitophagy. However, the obesity observed in p62 deficiency is most likely due to defective β-adrenergic signaling and mitochondrial biogenesis (34). Because mitophagy is a dynamic process with many putative and overlapping mediators, we are just beginning to develop the genetic and pharmacological techniques required to study its roles in disease. Given the widespread evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction across many cardiometabolic disease settings and the essential role for mitophagy in clearing damaged mitochondria, this topic of investigation will continue to be particularly fruitful.

Lipophagy

In a healthy physiological state, lipids are stored mainly in the form of triglycerides and cholesterol esters inside lipid droplets, dynamic organelles that are most prominent in adipocytes. Dysfunction of the metabolic and storage capacities of adipocytes results in toxic spillover of excess lipids into the circulation and their storage as lipid droplets in nearly every organ system (155). This ectopic accumulation is a primary hallmark and driver of systemic insulin resistance and cardiometabolic pathology (156), and restoration of healthy oxidation and trafficking of lipids is a longstanding mechanistic target. Classic regulators of lipid metabolism at the lipid droplet surface include neutral lipases such as neutral cholesterol-ester hydrolase-1 (NCEH1), hormone sensitive lipase (HSL), and adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), and synthases such as diglyceride acyltransferase (DGAT). Lipophagy, the selective autophagic degradation of intracellular lipids, is increasingly appreciated as a parallel, versatile contributor to lipid droplet homeostasis (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Molecular Mediators of Lipophagy.

Left: Autophagosome recruitment to lipid droplets and downstream autophagosome-lysosome interaction depends on the activity of the small GTPase Rab7. Center: The neutral lipases ATGL and HSL contain LC3 binding domains that are required for recruitment to the lipid droplet, constituting a mechanism for crosstalk between lipophagy and neutral lipolysis. Right: PLIN2 and PLIN3 (PLIN2/3) proteins coat the lipid droplet surface and block both lipophagy and neutral lipolysis. Chaperone-mediated autophagy targets PLIN2/3 using HSC70 as an adapter, resulting in their direct translocation into lysosomes for degradation. This allows the machineries of both neutral lipolysis and lipophagy to access the lipid droplet.

Although little is known about the precise steps required to initiate and carry out autophagy at the lipid droplet, most studies thus far have focused on a model in which lipid droplets are sequestered through autophagy and delivered to the lysosome for lysosomal acid lipase-mediated lipolysis (157–159). To our knowledge, classic selective autophagy receptors such as p62 have not been detected at lipid droplets, and ubiquitination events have been linked only to regulatory degradation of particular lipid droplet proteins, often through the proteasome (160–163). Nonetheless, lipophagy is selective because autophagosomes are found associated preferentially with lipid droplets under various conditions of lipid stress, distinguishing it from bulk autophagy (157–159). A molecular mediator of autophagosome recruitment to lipid droplets is the small GTPase Rab7, which also regulates trafficking of autophagosomes to lysosomes, though many structural aspects of these processes remain unclear (164).

Several studies highlight the mechanisms by which selective autophagy regulates lipid droplets through nontraditional means. First, the neutral lipases ATGL and HSL have LC3-binding motifs that are crucial for localization to lipid droplets and for overall lipolytic activity (165). These interactions exemplify the concept that many of the core autophagy structural proteins, including LC3, are themselves “ubiquitin-like” scaffolding proteins (166) with important functions beyond sequestering cargo. Second, under some conditions, autophagy also delivers lipids to lipid droplets for subsequent neutral lipolysis and mitochondrial oxidation (167, 168). Whether this process simply utilizes bulk autophagy of membrane lipids or can selectively target and degrade “less essential” membranes as substrates (169) is unknown. This observation additionally challenges the prevailing notion that autophagy is purely a degradative mechanism at the lipid droplet and that the presence of LC3 at the lipid droplet necessarily implies that degradative lipophagy is occurring. Third, lipolysis has been proposed to be tightly regulated by chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) (170). In this process, perilipin proteins (PLIN2/3), which normally coat the lipid droplet and block access to neutral lipases, are tagged by the adapter heat shock cognate protein 70 (HSC70), which promotes direct lysosome-associated membrane protein 2A (LAMP2A)-mediated translocation into the lysosome. Thus, CMA does not directly deliver lipids to lysosomes but instead constitutes a selective autophagic modulation of lipid droplet physiology. It should be noted that lipid droplets are relatively stable and nontoxic storage sites for cholesterol esters and triglycerides. Labile species such as ceramides, free fatty acids, and diacyglycerol associated with metabolic disease (171) are more likely to mediate lipotoxicity. It is an intriguing possibility that autophagic processes could be a mechanism by which such lipid intermediates are delivered to lipid droplets.

Initial interest in the physiological implications of lipophagy arose from studies suggesting substantive roles of this process in lipid catabolism, especially in the context of NAFLD. Singh et al. have shown that in lipid-overloaded states, autophagic vesicles sequester lipid droplets and deliver their contents to the lysosome for hydrolysis (158). Dysfunction in hepatocyte autophagy leads to reduced β-oxidation, resulting in lipid accumulation and hepatosteatosis (158,172), though this phenomenon may also be partially due to impaired mitophagy (86) rather than lipophagy per se. The limited data available suggests increased abundance of autophagic markers in human NAFLD (22, 173), perhaps as a compensatory response to excess lipids. A second setting in which lipophagy is critical for lipid catabolism is in foam cell macrophages, where massive accumulation of cholesterol ester-rich lipid droplets is a defining event in atherosclerosis. Ouimet et al. have shown that macrophage lipid droplets are delivered to lysosomes through autophagy, and cholesterol esters are then hydrolyzed through lysosomal lipolysis for efflux to HDL in an ABCA1-dependent manner (174). Consequently, it is not surprising that the functionality of lysosomes and associated acid lipases are crucial for lipophagy and disrupted in cardiometabolic pathology(175). Atherogenic lipids initiate lysosome dysfunction that inhibits the degradation of all delivered autophagic substrates (43, 51, 176). Similarly, excess free fatty acids promote lysosomal permeabilization and destabilization in human NAFLD (177). The severe liver steatosis and atherosclerosis observed in lysosomal acid lipase deficiency provides additional indirect evidence for lipophagy as a relevant route of cellular lipid catabolism (178–180).

In contrast, the importance of lipophagic delivery to lysosomes is not universal. Adipose tissue macrophages activate lysosomal biogenesis during obesity most likely to metabolize and redistribute massive internal and external lipid loads from stressed adipocytes (181, 182). Surprisingly, autophagy deficiency achieved by deletion of ATG5 or ATG7 in adipose tissue macrophages does not substantially disrupt lipid metabolism or affect metabolic phenotypes, suggesting lipophagy is not a critical route of lipid delivery to lysosomes even in this lipid-stressed setting (67, 182). Could a predominance of CMA, non-ATG5/ATG7 macroautophagy (183), or extracellular digestion through lysosomal exocytosis(184) explain these findings? Overall, many additional questions remain to be answered in understanding how impaired lipophagy may contribute to cardiometabolic disease and how it might be targeted to more appropriately traffic lipids. Key areas of investigation include how the autophagic machinery interacts with lipid droplets and how lipophagy is regulated in a context-dependent manner to either deplete or build lipid droplets in appropriate tissues.

Transcriptional Regulation and Integration of Selective Autophagy with Metabolic Signaling

Given the importance of selective autophagy in maintaining cellular homeostasis, components of its molecular machinery are under tight regulation by stress-responsive and metabolic transcription factors. In turn, selective autophagy receptors often also serve as scaffolds that interact with and regulate many cell signaling pathways. Through this mechanism, their buildup can serve as a key monitored variable signifying failure or insufficiency of autophagic clearance. We briefly discuss these key concepts and their relevance to cardiometabolic disease.

Transcriptional regulation of the molecular mediators of selective autophagy is poorly understood and seems to be mostly embedded within broader transcriptional programs regulating autophagy-lysosomal biogenesis and stress responses (Figure 6). Amongst these factors are the MITF-TFE family of transcription factors which particularly target autophagy-lysosomal genes, notably including p62 (43, 185). This control is exerted primarily through the affinity of TFEB and TFE3 for Coordinated Lysosome Expression and Regulation (CLEAR) motifs, subtypes of E-box elements in target promoter sequences (185–187). A major point of control for these transcription factors lies in their regulation by the mTORC1 complex, a nutrient-sensitive signaling hub widely implicated in metabolic regulation (188). Under basal conditions, mTORC1 phosphorylates TFEB and/or TFE3 at the lysosome to facilitate binding to 14-3-3 chaperones which retain them in the cytosol, thereby limiting transcriptional activity (189, 190). Upon conditions of starvation or lysosomal stress, mTORC1 activity is inhibited, allowing translocation of TFEB and/or TFE3 to the nucleus to transcriptionally actrivate autophagy and lysosomal genes (187, 189–191).

Figure 6. Transcriptional Feedback Control of Selective Autophagy.

Several parallel feedback loops couple sensing of organelle damage with transcriptional regulation of selective autophagy genes. Under basal conditions, KEAP1 binds to and targets NRF2 for proteasomal degradation. Protein aggregates and dysfunctional mitochondria accumulate p62, which binds to and sequesters KEAP1 to free NRF2 and activate its transcriptional activity. NRF2 targets many selective autophagy genes to degrade p62-tagged cargo. Similarly, TFEB translocates to the nucleus in response to mitochondrial and lysosomal stresses to transcribe selective autophagy, mitochondrial, and lysosomal genes.

In the case of selective autophagy, details are just beginning to emerge on how this mTORC1-TFEB/TFE3 axis interacts with important players such as p62. MITF-TFE family transcription factors translocate to the nucleus in a Parkin or PINK1-dependent manner in response to mitochondrial stress, and the absence of TFEB or TFE3 substantially impairs mitophagy (Figure 6) (192, 193). In many disease and genetic autophagy-deficient settings, p62 builds up as a result of failed autophagic clearance. However, complete genetic deficiency of all MITF-TFE family members impairs mitochondrial stress-induced p62 transcription and translation to such a degree that p62 abundance does not increase in response to mitochondrial stress despite mitophagy deficiency (192).

TFEB also exemplifies a second important concept in the transcriptional regulation of selective autophagy: the coupling of programs regulating selective autophagy with those mediating biogenesis of the organelles destined for degradation. For example, TFEB also transcriptionally targets peroxisome-proliferator activated receptor coactivator-1α (pgc-lα) (194), a transcriptional coactivator that orchestrates mitochondrial and peroxisomal biogenesis (105,195). Another parallel mode of transcriptional regulation of selective autophagy involves the transcription factor NRF2, which mediates antioxidant responses in response to oxidative stress (Figure 6). NRF2 targets autophagy-related genes encoding p62, NDP52, and other autophagy components (196, 197). The most intriguing aspect about this regulation is the feedback role of p62 on NRF2 activity. Under diverse conditions of impaired or insufficient selective autophagy, p62 accumulates on poorly degraded substrates (18,19,198), allowing p62 to bind to and neutralize a large portion of the cellular pool of KEAP1 which would otherwise sequester NRF2 for proteasomal degradation (199). The result is increased availability of free NRF2, enabling nuclear translocation and transcription of selective autophagy targets (Figure 6) (29, 200, 201). We postulate that this mechanism is one of several feedback loops that responds to dysfunctional or insufficient selective autophagy to restore homeostasis and orchestrate cellular metabolism (Figure 4). p62 also both regulates and/or is a transcriptional target of several crucial metabolic signaling mediators including NF-κB (57, 202, 203), mTOR (32, 204, 205), PKC (203, 206), VDR/RXR (33), and ERK1 (207, 208). Unsurprisingly, several murine models of whole body or tissue-specific p62 abrogation result in obesity and diabetes and the precise tissues and physiological mechanisms involved are complex (34, 208, 209). The FOXO family of transcription factors also regulate selective autophagy by targeting the genes encoding PINK1 (210), BNIP3 (211, 212), and other autophagy genes. Like NRF2 and TFEB, the FOXO transcription factors respond to a wide range of stresses by promoting both mitophagy and lipophagy (213). Ultimately, a mature understanding of selective autophagy will require further studies on its regulation and integration with cellular metabolic signaling pathways.

Looking forward: outstanding fundamental questions in the roles of selective autophagy in metabolic disease and therapeutic opportunities

In this review, we have described how dysfunctional organelles are recognized and cleared by selective autophagy to maintain cellular homeostasis and modulate cardiometabolic disease pathology. To put these concepts into context, an important open question is whether the molecular mechanisms that establish the specificity of selective autophagy (such as ubiquitination and selective autophagy receptor binding) are actually dysfunctional or rate-limiting in disease states. On one hand, molecular mediators of these steps are clearly necessary and important for limiting dysfunctional organelle accumulation as we have discussed and evidenced by the maladaptive phenotypes of various cellular and murine knockout models. However, no evidence thus far suggests a strict insufficiency in cargo recognition and tagging. It will be important to test whether enhancing these early steps in selective autophagy through genetic overexpression models or specific drug targeting can promote organelle clearance for cardiometabolic benefit. We propose that appropriate selective autophagy substrates are generally “primed and ready” for autophagic sequestration and lysosomal degradation, but dysfunction in these latter processes is more likely to be rate limiting. For example, there may simply be a lack of autophagy initiation toadequately sequester cargo, the cargo may be too large, or cargo may be toxic and disruptive to the function of the autophagosome and lysosomes. Indeed, mere haploinsufficiency of ATG7 greatly accelerates the progression of diabetic pathology by inducing inflammasome hyperactivity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and lipid accumulation (68) suggesting that the availability of autophagosome components easily becomes limiting even with large obesity-induced compensatory increases (68). Conversely, global overexpression of ATG5 reduces adiposity, increases insulin sensitivity, and extends lifespan (214), and ATG7 overexpression has similar effects (172). Autophagic cargo, especially lipids, may be particularly toxic to autophagic and lysosomal membranes and disrupt their function. For example, lysosomes lose membrane permeability and degradative function when loaded with lipids as in atherosclerosis (43), and autophagosome and lysosome membrane dynamics and fusion are influenced by altered membrane lipid composition induced by high fat diets (215).

These ideas raise several additional questions regarding the therapeutic induction of autophagy to treat cardiometabolic disease. First, does broad induction of autophagy through various genetic, behavioral, or pharmacological means initiate a pattern of grossly nonselective “bulk” degradation, or is tagging of dysfunctional organelles adequate to bias the induced autophagic machinery towards selective degradation of this cargo? It is a concern that initiation of “bulk” autophagy will cause complications due to degradation of off-target cellular components. However, even starvation, the prototypical stimulus for “bulk” autophagy, involves an ordered process of degradation (169, 216). Additionally, we have discussed how several modes of selective autophagy are coupled to transcriptional programs of organelle biogenesis, and that many of the signaling cascades initiating autophagy also target mediators of selective autophagy (Figure 6) such that dysfunctional organelles may be prioritized. Second, several groups have established that autophagy cannot proceed with impaired lysosomes (217, 218). It remains unclear whether lysosomal dysfunctions such as impaired biogenesis, membrane permeabilization, and insufficient acidity are truly a primary cause of autophagic failure and metabolic dysfunction. Could targeting lysosomal dysfunction serve as a better conceptual target in treating metabolic disease? Finally, are specific molecular events (such as favoring phosphorylation and binding of a particular selective autophagy receptor) viable targets to enhance organelle clearance, or is organelle dysfunction too broad for stimulating specific clearance pathways to be beneficial?

With these questions and concepts in mind, we briefly discuss progress in stimulating autophagy to treat cardiometabolic disease with regard to the selective cargoes we have discussed (Table 1). First, exercise and caloric restriction are highly effective frontline behavioral interventions to prevent and curb the progression of cardiometabolic disease. Both interventions stimulate autophagy, restore organelle homeostasis, and target many of the known transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms that regulate selective autophagy (219, 220). For example, Bag3- and p62-mediated selective autophagy is induced in humans performing resistance training (221), and exercise-induced restoration of muscle glucose homeostasis is autophagy dependent (222). Similarly, various modes of caloric restriction protect against steatotic liver pathology (223) and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through mechanisms associated with autophagy induction (224). How these behavioral interventions regulate, and whether their effects depend specifically on selective autophagy is largely unexamined. Genetic manipulations of factors that control selective autophagy are also of mechanistic and therapeutic interest. For example, uncovering how certain transcription factors differentially target molecular mediators of selective autophagy may allow pharmacological compounds targeting those pathways to be appropriately matched to specific organelle dysfunctions. We highlight TFEB and TFE3 as particularly attractive regulators of selective autophagy because they target a mechanistically complete transcriptional program of selective autophagy, lysosomal biogenesis, and lipid catabolism. Overexpression of TFEB and/or TFE3 in various tissue specific manners protects against atherosclerosis (43), steatohepatitis (194, 225), and type 2 diabetes (194, 225, 226). Of course, the ultimate goal lies in pharmacologically targeting selective autophagy to treat cardiometabolic disease. Neutralizing damaging organelle products such as ROS and inflammatory cytokines has been extensively investigated, but conceptually, this approach is thought to be problematic because it also disrupts adaptive basal ROS and inflammatory signaling (227, 228) without proportionally restoring the organelles that generate these signals. In contrast, pharmacologically stimulating selective autophagy addresses the needs of both neutralizing excess ROS and inflammatory signals and rescuing the upstream organelle dysfunction. To date, truly specific pharmacological manipulation of a molecular mediator or organelle target of selective autophagy has not been therapeutically achieved. Nonetheless this degree of precision may be ineffective due to redundancy in clearance pathways, and could cause off target effects because selective autophagy adapters have autophagy-independent roles. As discussed, broader stimulation of autophagy could be leveraged to bias clearance of already selectively tagged cargos, and inducing broader transcriptional regulators such as TFEB and TFE3 favors a comprehensive program of selective autophagic clearance. Various compounds can induce these types of responses. For example, mTORC1 inhibitors such as Rapamycin induce TFEB nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity (190), and also spur autophagy by relieving mTORC1 repression of ULK1, the primary kinase that initiates macroautophagy (229, 230). Although mTOR inhibition has pleiotropic effects beyond inducing autophagy, it represents an important target in treating cardiometabolic disease (231). Second, the naturally occurring disaccharide trehalose potently induces autophagy in vivo and is effective in treating NAFLD (68, 232), endothelial dysfunction (145, 233), and diabetes (41, 68, 234). Because orally administered trehalose does not efficiently cross the intestinal epithelium (235) and may cause modest weight gain in humans due to its conversion to glucose (233), widespread use awaits means of improving its pharmacological properties or exploring the use of closely related compounds (236). Third, the polyamine spermidine can stimulate autophagy by modulating protein acetylation (237) and has shown promise in treating endothelial dysfunction (144, 238) and atherosclerosis (239) through autophagy-related mechanisms. Of course, there are many more autophagy-inducing compounds with therapeutic potential (240) and more studies are required to better understand how they may favor selective clearance of dysfunctional organelle cargo.

Table 1.

Therapeutic Means of Enhancing Selective Autophagy in Metabolic Disease

| Treatment | Selective Autophagy Related Targets Identified thus far | Impacts on Cardiometabolic Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Interventions | ||

| Exercise | Bag3 (241), p62 (241), NRF2 (242), TFEB (243), BNIP3 (244), BRCA1 (245) | Broad Protection |

| Caloric Restriction (or fasting) | BNIP3 (246), FOXO (246),TFEB (194, 247), Rab7 (164), p62 (248), TFE3 (187) | Broad Protection |

| Genetic Models | ||

| TFEB | p62(43, 185) and other autophagy-lysosomal genes (43, 185, 186) | ↓ NAFLD (194) ↓ Obesity/Diabetes (194) ↓ Atherosclerosis (43) |

| TFE3 | p62(192) amongst many autophagy-lysosomal genes (187, 192) | ↓ NAFLD (225, 249) ↓Diabetes (225, 226)(226) |

| Pharmacological Strategies | ||

| Trehalose | p62 (250) and other means of autophagy modulation (145, 232, 250–252) | ↓ NAFLD (68, 232) ↓ Diabetes (41, 68, 234) ↓ Endothelial Dysfunction (145, 233) |

| Spermidine | ATM (253), PINK1 (253), Parkin (253) | ↓ Atherosclerosis (239) ↓ Endothelial Dysfunction (144, 238) |

In summary, selective autophagy is a deterministic pathway that mediates the clearance of diverse organelle cargoes widely implicated in the progression of cardiometabolic disease. Key steps in these coordinated processes include tagging of cargo, recognition, interaction with autophagic machinery, and lysosomal degradation. The precise molecular mediators of selective autophagic clearance of inflammasomes, lipid droplets, protein aggregates, peroxisomes, and mitochondria are somewhat distinct, but perhaps most commonly share ubiquitination and p62 or NBR1 mediated recognition. We anticipate that increased understanding of the regulation and interventional targeting of selective autophagy will prove fruitful in stemming the tide of cardiometabolic disease.

One-sentence summary.

Boosting the autophagic degradation of dysfunctional organelles could be used to treat various cardiometabolic diseases.

GLOSS.

The accumulation of damaged or excess proteins and organelles is a defining feature of cardiometabolic diseases such as diabetes, atherosclerosis, and heart failure. One way in which damaged components such as mitochondria, protein aggregates, or peroxisomes are degraded is through autophagy, a process in which a double membrane vesicle encapsulates cargo and delivers it to the acidic lysosome for degradation. A diverse array of molecular mechanisms target the autophagic machinery specifically to damaged cargo and spare healthy components in a process called selective autophagy. Disruption of these processes leads to accumulation of unhealthy organelles, oxidative stress, inflammation, and disease progression. Conversely, stimulating the autophagy-lysosome degradation system in disease states featuring overt accumulation of dysfunctional organelles provides an attractive avenue for therapies. In this review, which contains 6 figures, 1 table, and 253 citations, we focus on emerging evidence and key questions about the role of selective autophagy in the cell biology and pathophysiology of cardiometabolic diseases.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH) 1R01HL125838 and P30 DK020579 (to B. Razani) and F31HL132434 (to T.D. Evans).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Roth GA, et al. Global and regional patterns in cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to 2013. Circulation. 2015;132:1667–1678. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson C, Ike C, Willis PW, IV, Stouffer GA, Willis MS. The bitter end: The ubiquitin-proteasome system and cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2007;115:1456–1463. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Versari D, et al. Dysregulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in human carotid atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2132–2139. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000232501.08576.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parzych KR, Klionsky DJ. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:460–73. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147:728–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraft C, Peter M, Hofmann K. Selective autophagy: ubiquitin-mediated recognition and beyond. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:836–841. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klionsky DJ, et al. A comprehensive glossary of autophagy-related molecules and processes (2 nd edition) Autophagy. 2011;7:1273–1294. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.11.17661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu P, et al. Quantitative Proteomics Reveals the Function of Unconventional Ubiquitin Chains in Proteasomal Degradation. Cell. 2009;137:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willis M, Patterson C. Proteotoxicity and Cardiac Dysfunction — Alzheimer’s Disease of the Heart? N Engl J Med. 2013;368:455–464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1106180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kopito RR. Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:524–530. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett EJ, Bence NF, Jayakumar R, Kopito RR. Global impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by nuclear or cytoplasmic protein aggregates precedes inclusion body formation. Mol Cell. 2005;17:351–365. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamark T, Johansen T. Aggrephagy: Selective disposal of protein aggregates by macroautophagy. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/736905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murata S, Minami Y, Minami M, Chiba T, Tanaka K. CHIP is a chaperone-dependent E3 ligase that ubiquitylates unfolded protein. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:1133–1138. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olzmann JA, Chin LS. Parkin-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination: A signal for targeting misfolded proteins to the aggresome-autophagy pathway. Autophagy. 2008;4:85–87. doi: 10.4161/auto.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gamerdinger M, Carra S, Behl C. Emerging roles of molecular chaperones and cochaperones in selective autophagy: Focus on BAG proteins. J Mol Med. 2011;89:1175–1182. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0795-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gamerdinger M, Kaya aM, Wolfrum U, Clement AM, Behl C. BAG3 mediates chaperone-based aggresome-targeting and selective autophagy of misfolded proteins. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:149–156. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pankiv S, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komatsu M, et al. Homeostatic Levels of p62 Control Cytoplasmic Inclusion Body Formation in Autophagy-Deficient Mice. Cell. 2007;131:1149–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sergin I, et al. Inclusion bodies enriched for p62 and polyubiquitinated proteins in macrophages protect against atherosclerosis. Sci Signal. 2016;9:1–15. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aad5614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stumptner C, Fuchsbichler A, Zatloukal K, Denk H. In vitro production of mallory bodies and intracellular hyaline bodies: The central role of sequestosome 1/p62. Hepatology. 2007;46:851–860. doi: 10.1002/hep.21744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filimonenko M, et al. The Selective Macroautophagic Degradation of Aggregated Proteins Requires the PI3P-Binding Protein Alfy. Mol Cell. 2010;38:265–279. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuo Y, et al. Abnormality of autophagic function and cathepsin expression in the liver from patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:1026–1036. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zatloukal K, et al. p62 Is a common component of cytoplasmic inclusions in protein aggregation diseases. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:255–263. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64369-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zatloukal K, et al. From Mallory to Mallory-Denk bodies: What, how and why? Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2033–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng Y, French BA, Tillman B, Morgan TR, French SW. The inflammasome in alcoholic hepatitis: Its relationship with Mallory-Denk body formation. Exp Mol Pathol. 2014;97:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inami Y, et al. Persistent activation of Nrf2 through p62 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:275–284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathew R, et al. Autophagy Suppresses Tumorigenesis through Elimination of p62. Cell. 2009;137:1062–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ni HM, et al. Nrf2 promotes the development of fibrosis and tumorigenesis in mice with defective hepatic autophagy. J Hepatol. 2014;61:617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komatsu M, et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:213–223. doi: 10.1038/ncb2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takamura A, et al. Autophagy-deficient mice develop multiple liver tumors. Genes …. 2011;5:795–800. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. p62 at the Crossroads of Autophagy, Apoptosis, and Cancer. Cell. 2009;137:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umemura A, et al. p62, Upregulated during Preneoplasia, Induces Hepatocellular Carcinogenesis by Maintaining Survival of Stressed HCC-Initiating Cells. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:935–948. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duran A, et al. p62/SQSTM1 by Binding to Vitamin D Receptor Inhibits Hepatic Stellate Cell Activity, Fibrosis, and Liver Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:595–609. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller TD, et al. P62 Links β-adrenergic input to mitochondrial function and thermogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:469–478. doi: 10.1172/JCI64209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lahiri P, et al. p62/Sequestosome-1 Is Indispensable for Maturation and Stabilization of Mallory-Denk Bodies. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janson J, Ashley RH, Harrison D, McIntyre S, Butler PC. The mechanism of islet amyloid polypeptide toxicity is membrane disruption by intermediate-sized toxic amyloid particles. Diabetes. 1999;48:491–498. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Despa S, et al. Cardioprotection by controlling hyperamylinemia in a “Humanized” diabetic rat model. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:14–18. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Despa S, et al. Hyperamylinemia contributes to cardiac dysfunction in obesity and diabetes: A study in humans and rats. Circ Res. 2012;110:598–608. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rivera JF, et al. Human-IAPP disrupts the autophagy/lysosomal pathway in pancreatic β-cells: protective role of p62-positive cytoplasmic inclusions. Cell Death {&} Differ. 2011;18:415–426. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivera JF, Costes S, Gurlo T, Glabe CG, Butler PC. Autophagy defends pancreatic β cells from Human islet amyloid polypeptide-induced toxicity. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3489–3500. doi: 10.1172/JCI71981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim J, et al. Amyloidogenic peptide oligomer accumulation in autophagy-deficient β cells induces diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3311–3324. doi: 10.1172/JCI69625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shigihara N, et al. Human IAPP - induced pancreatic β cell toxicity and its regulation by autophagy. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3634–3644. doi: 10.1172/JCI69866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emanuel R, et al. Induction of lysosomal biogenesis in atherosclerotic macrophages can rescue lipid-induced lysosomal dysfunction and downstream sequelae. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014:1942–1952. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herrmann J, et al. associated with acute coronary syndromes Increased Ubiquitin Immunoreactivity in Unstable Atherosclerotic Plaques Associated With Acute Coronary Syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;40 doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02564-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jessup W, Mander EL, Dean RT. The intracellular storage and turnover of apolipoprotein B of oxidized LDL in macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)/Lipids Lipid Metab. 1992;1126:167–177. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(92)90287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]