NADPH oxidase (Nox)2 is a promising target for treating cardiovascular disease, but there are no specific inhibitors. Finding endogenous signals that can target Nox2 and other inflammatory molecules is of great interest. In this study, we used high-throughput screening to identify microRNAs that target Nox2 and improve cardiac function after infarction.

Keywords: microRNA, oxidative stress, myocardial infarction

Abstract

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the most common cause of heart failure. Excessive production of ROS plays a key role in the pathogenesis of cardiac remodeling after MI. NADPH with NADPH oxidase (Nox)2 as the catalytic subunit is a major source of superoxide production, and expression is significantly increased in the infarcted myocardium, especially by infiltrating macrophages. While microRNAs (miRNAs) are potent regulators of gene expression and play an important role in heart disease, there still lacks efficient ways to identify miRNAs that target important pathological genes for treating MI. Thus, the overall objective was to establish a miRNA screening and delivery system for improving heart function after MI using Nox2 as a critical target. With the use of the miRNA-target screening system composed of a self-assembled cell microarray (SAMcell), three miRNAs, miR-106b, miR-148b, and miR-204, were identified that could regulate Nox2 expression and its downstream products in both human and mouse macrophages. Each of these miRNAs were encapsulated into polyketal (PK3) nanoparticles that could effectively deliver miRNAs into macrophages. Both in vitro and in vivo studies in mice confirmed that PK3-miRNAs particles could inhibit Nox2 expression and activity and significantly improve infarct size and acute cardiac function after MI. In conclusion, our results show that miR-106b, miR-148b, and miR-204 were able to improve heart function after myocardial infarction in mice by targeting Nox2 and possibly altering inflammatory cytokine production. This screening system and delivery method could have broader implications for miRNA-mediated therapeutics for cardiovascular and other diseases.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY NADPH oxidase (Nox)2 is a promising target for treating cardiovascular disease, but there are no specific inhibitors. Finding endogenous signals that can target Nox2 and other inflammatory molecules is of great interest. In this study, we used high-throughput screening to identify microRNAs that target Nox2 and improve cardiac function after infarction.

myocardial infarction (MI) is the leading cause of heart failure (HF), which results in tremendous morbidity and mortality worldwide (10). MI leads to scar formation and adverse cardiac remodeling including changes in the molecular and structural components of the myocardium, which lead to cardiac dysfunction (1). After MI, circulating blood monocytes respond to chemotactic factors, migrate into the infarcted myocardium, and differentiate into macrophages. In addition, neutrophils and other inflammatory cells migrate to the injured myocardium acutely and initiate a wound healing response (7). While studies have shown that low levels of ROS are physiologically important, production of excessive amounts of ROS is a key event involved in post-MI pathogenesis (8). ROS modulate several processes during cardiac remodeling, including interstitial fibrosis, cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and hypertrophy (4, 23).

Many studies have demonstrated that a major source for ROS in the heart comes from a family of NADPH oxidase enzymes (5). NADPH oxidase is a multisubunit enzyme consisting of membrane proteins (gp91phox, otherwise known as Nox and p22phox) and several intracellular associated proteins (p47phox, p67phox, and Rac). Five Nox isoforms (Nox1 to Nox5) exist and are thought to be the major indispensable subunits. Among these, Nox2 is expressed in cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells and is thought to be the dominant Nox isoform contributing to cardiac superoxide (O2−) level production (2, 23). Evidence shows that both in animal models of MI and patients with end-stage heart failure, Nox2 expression is significantly increased in the infarcted myocardium, primarily in macrophages and myocytes (14, 19). Nox2 knockout mice show reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and adverse remodeling after MI and attenuate interstitial fibrosis after aortic constriction (12, 23). Recent studies have shown that Nox2 overexpression in cardiomyocytes does not alter infarct size but rather long-term remodeling, indirectly demonstrating a role of inflammatory cell Nox2 in this process (27). In addition, as there is no specific inhibitor of Nox2, studies from our own laboratory have shown that Nox2 small interfering (si)RNA delivered in polymeric nanoparticles can attenuate acute cardiac dysfunction after MI as a potential therapeutic alternative (29).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous small noncoding RNAs, ~22 nucleotides in length, which can mediate posttranscriptional gene silencing by binding to the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of target mRNAs and inducing translational inhibition or RNA decay (18). miRNAs are involved in diverse biological progresses, including cellular differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and migration (15, 30, 37). miRNAs have been demonstrated as a significant regulation factor in cardiovascular diseases. For example, miR-24 has been shown to be upregulated after cardiac ischemia, and its inhibition can prevent endothelial cell apoptosis and increase vascularity, which results in preservation of cardiac function and survival (9). Meanwhile, overexpression of miR-21 significantly decreased infarct size in mice after ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury (25). Another study reported miR-34a to be upregulated after MI (34). Knockdown of miR-34a in mice could significantly improve hearts post-MI remodeling.

The critical challenge in miRNA therapy for cardiac disease includes identifying miRNAs that can target important genes and deliver them into specific cells efficiently. A certain miRNA normally has hundreds of targets, which is difficult to validate only by database prediction. Most published works using high-throughput miRNA target validation are used to identify targets of a miRNA (13, 24, 31). However, for a specific pathological disease, in which we already know which genes play important roles, it is more useful to find and select miRNAs that can target those genes directly. As Nox2 has no specific inhibitor and plays such an important role in post-MI pathogenesis, finding new ways to reduce expression could generate new therapeutic options. Moreover, to date, there have been no reports of miRNAs that target Nox2 directly and reduce expression. In this study, we demonstrate use of a self-assembled cell microarray (SAMcell) to find miRNAs that target Nox2 and deliver them into myocardial macrophages via acid-degradable polymers previously shown to deliver siRNAs into macrophages (29). The SAMcell system had been demonstrated for its efficient and accurate miRNA targeting identification by our previous work (35). SAMcell assays using the 3′-UTR of Nox2 identified many potential miRNAs that were then tested in reporter cells as well as in mouse and human macrophages. Validated miRNA were loaded within polyketal nanoparticles for macrophage targeting and delivered after acute MI.

METHODS

Cell culture procedures.

miRNA mimics were obtained from GenePharma and Sigma. 293T and Hela cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS as well as 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (P/S). RAW 264.7 and THP-1 cells were cultured RPMI-1640 containing same amounts of FBS and P/S as described above. All cells were cultured under humidified conditions in 5% CO2 at 37°C. When being seeded, cells were washed with PBS and incubated in 0.25% trypsin containing 5 mmol/l EDTA. After centrifugation, cells were diluted in media, counted via hemocytometer, and then seeded at the appropriate concentration.

To achieve transient expression, plasmids and miRNA mimics were transfected using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). Cell number and nucleotide were determined per manufacturer’s protocol. To establish stable cell lines, the indicated lentiviral vectors were packaged and transfected into cells. In brief, lentivirus was packaged into 293T cells and then harvested and infected to Hela cells. After 72 h, cells were selected and collected by FACS.

Luciferase assays.

For luciferase assays, the 3′-UTR of human or mouse Nox2 was cloned into pGL3 plasmids 3′ to the firefly luciferase gene. 293T cells (4 × 104 cells) were cotransfected with 200 ng of the indicated pGL3 firefly luciferase construct, and 20 ng of pGL3 Renilla luciferase were used as a normalization control. At the same time, the indicated miRNA expression plasmid or mimics were transfected. After 48 h, cells were lysed and luciferase activities were measured using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

Screening of miRNA targets using SAMcell.

The fabrication of the SAMcell microarray has been previously described (36). In brief, glass slides (22 × 22 mm) were covered with poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (Aldrich) dissolved in ethanol [6% (wt/vol)]. Slides were etched via a shadow mask by oxygen plasma for 3.5 min at 200 W of power. The reverse transfection protocol described below refers to a previous description (36). The miRNA mimic library mixed in the reverse transfection reagent was printed on the chip (Suzhou Genoarray). Next, slides were fixed in a six-well plate by melted wax. A reporter system was built that expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP). The 3′-UTR of human Nox2 was then cloned as the 3′-UTR of eGFP, and a stable Hela cell line expressing the reporter system was selected by FACS as described above. Over 260 miRNAs were printed on the SAMcell chip. Then, 5 × 105 cells containing 3′-UTR reporter were transferred into each well. After being cultured for 48 h, dishes were moved to room temperature for 5 min and washed with PBS for three times to remove the polymer. Average fluorescent intensity of each cell island was collected and analyzed. The cutoff value was obtained on the basis of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Z-test in 50 control experiments. Six replicates were repeated for each miRNA.

Polyketal synthesis.

Polyketal (PK3) was synthesized as described in our prior study (20). Briefly, the diols cyclohexanedimethanol and 1,5-pentanediol were dissolved in distilled benzene and heated to 100°C. Recrystallized p-toluenesulfonic acid (PTSA) was dissolved (~1 mg) in ethyl acetate and added to the benzene solution to catalyze the reaction. The polymerization reaction was initiated by the addition of equimolar 2,2-diethoxypropane (DEP). Additional 2,2-dimethoxy propane (DMP) and benzene were subsequently added to the reaction to compensate for loss of volume in the form of ethanol/methanol and the solvent benzene that had distilled off. After 48 h, the reaction was stopped with triethylamine and isolated by precipitation in cold hexanes. The solid polymer was filtered off, rinsed in hexanes, and vacuum dried before storage at −20°C. Polymer molecular weight/polydispersity was confirmed by gel permeation chromatography.

Preparation of miRNA-loaded PK3 particles.

PK3-miRNA particles were prepared following the protocol for PK3-siRNA particles (29). Briefly,1 mg of miRNA in water and 2.2 mg of cationic lipid N-[1-(2,3-dioleoyloxy)propyl]-N,N,N,trimethylammonium methysulfate (DOTAP) dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM) were brought to one phase by the addition of 1.05 ml methanol. After a 15-min incubation, an additional 0.5 ml of water and DCM were added, and the mixture was vortexed and centrifuged at 750 rpm for 5 min. The miRNA:DOTAP complex in the bottom organic layer was encapsulated in PK3 via an oil/water single emulsion procedure using DCM as the oil phase and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) as the surfactant stabilizer. One milliliter of DCM containing ion-paired miRNA was added to 40 mg of PK3 with 1 mg of chloroquine free base. This solution was homogenized into 8 ml of 5% (wt/vol) PVA solution at the highest setting in the Power Gen 500 (Fisher Scientific) for 30 s and sonicated at an intermediate speed (Sonic dismembrator model 100, Fisher Scientific) with 10 pulses of a 1-s duration. The emulsion was then dispersed in a 20 ml of 0.5% PVA solution and stirred for a period of 4–5 h to allow the DCM to evaporate. The resulting particles were isolated by centrifugation (15,000 rpm, 20 min), washed three times, freeze dried, and stored at −20°C for further use.

In vitro delivery of PK3-miRNA particles.

For in vitro studies, RAW 264.7 macrophages or PMA-induced THP-1 cells were plated in six-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well. After 24 h, cells were treated with the indicated PK3-miRNA particles at a concentration of particles equivalent to 2 µg miRNA/well. For gene expression studies, after 48 h of treatment, cells were harvested and RNA or protein was extracted. For the assessment of functional activity of Nox2-NADPH, cells were kept in wells for analysis of O2− production.

Gene expression by real-time PCR and Western blot.

Total RNA from cells was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed using Power SYBR green (Invitrogen) master mix with an Applied Biosystems StepOne Plus real-time PCR system. The primers used are listed in the Supplemental Material (Supplemental Table S1; Supplemental Material for this article is available at the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology website). Nox2 gene expression levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Total protein extracted from cells was resolved by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). Membranes were probed with antibodies against Nox2 (Abcam) and GAPDH (Abcam). Images were obtained and quantified by ImageJ software.

Supernatant collection and ELISA.

Forty-eight hours after transfection with the indicated miRNAs, Raw246.7 media were collected for analysis. The concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the supernatant were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems). All assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Detection of O2− in vitro and in vivo.

To test Nox2 activity in vitro, production of O2− after stimulation with phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) was measured by staining with fluorescent ROSstar 650 dye. Forty-eight hours after transfection with miRNAs or treatment with PK3-miRNA particles, media were aspirated from wells containing induced THP-1 or RAW 264.7 macrophages and then washed with fresh cold Krebs-HEPES buffer (KHB). Then, 10 µM PMA was added to each well and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. After this, 25 µM dye was added to wells and incubated for 20 min under dark conditions. For in vivo studies, frozen sections were washed by KHB and stained with dihydroethidium (DHE) directly for 20 min. Fluorescent images were taken by Nikon fluorescent microscope using equal exposure times for all samples.

MI and particle injection.

Studies were conducted under a randomized and blinded manner. Adult male C57BL/6 mice (>8 wk) were used and assigned to five groups. One group was subjected to sham surgery, whereas the other four groups received permanent MI. The surgeries were conducted as previously described (26). Briefly, animals were anesthetized by isoflurane (1–3% inhaled). After tracheal intubation, the heart was exposed by separation of the ribs. MI was achieved by ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery. For mice that received particle injections, 50 µl of the indicated particle were injected into the cyanotic ischemic zone through a 30-gauge needle immediately after ligation. The dose of miRNA injected was 5 µg/kg. After injection, the chests were closed and animals were recovered on a heating pad. Animals were euthanized by regulated CO2 inhalation in a closed chamber per proper guidelines. Functional assessments were made at 3 days after surgeries using echocardiography. These studies conformed with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health, and all animal studies were approved by the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunohistochemistry.

Fresh heart tissue was frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT, and 5-µm sections were made. After being washed with PBS, sections were fixed by 4% formaldehyde solution and then incubated with goat serum for 1 h. Nox2 antibody diluted in goat serum was added to the sections and incubated at 4°C overnight. After that, sections were washed three times using PBS-Tween and incubated with fluorescent secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. At least three sections from each animal were analyzed. Nuclei were stained by Hoechst dye. Images were taken by Nikon at identical exposures and analyzed by ImageJ software.

Echocardiography and infarct size.

Anesthetized mice were subjected to echocardiography 3 days after MI surgery. Short-axis values of left ventricular diameter were obtained using a Vevo 770 small animal ultrasound system (Visualsonics). An average of three consecutive cardiac cycles was used for each measurement and performed three times in an investigator-blinded manner. Fractional shortening (FS) was calculated as (end-diastolic diameter − end-systolic diameter)/end-diastolic diameter and expressed as a percentage.

Myocardial infarct size was evaluated using 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining and Evans blue dye in which the percent area of infarction was calculated as the infarcted area (TTC stained) divided by the ischemic area at risk at 24 h after injury.

Statistics.

For statistical analysis, two-sided Student’s t-tests were used for in vitro studies, whereas one-way ANOVA tests were used for in vivo studies. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Error bars indicate SD of at least three independent experiments.

RESULTS

SAMcell screening to target human Nox2.

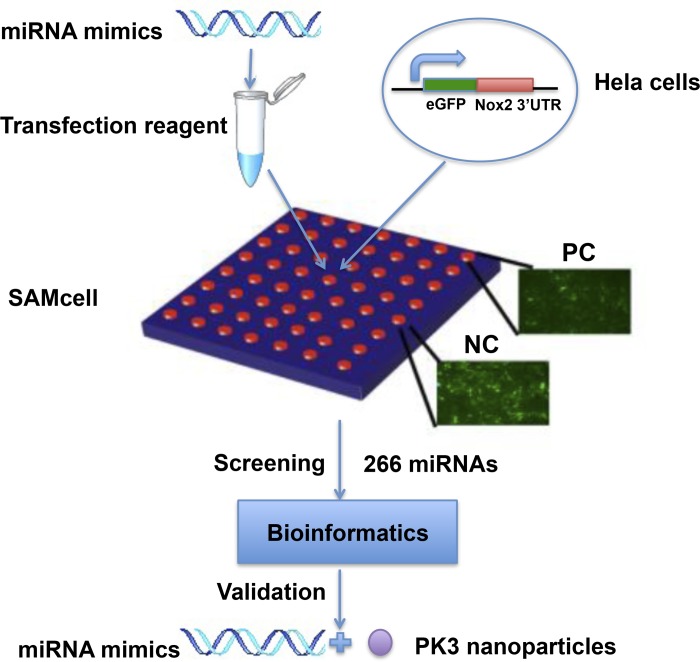

A schematic diagram of the screening system is shown in Fig. 1. The 3′-UTR of human Nox2 was cloned into the reporter system, and 266 miRNAs, conserved between human and mouse, were screened by the SAMcell assay. The top effective miRNAs are shown in Table 1. Three miRNAs, miR-106, miR-148b, and miR-204, were selected for further study after literature research and miRNA target prediction. Each of them have one or more predicted binding sites in human Nox2 3′-UTR according to the Targetscan database, as shown in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the screening strategy to identify microRNAs (miRNAs) targeting human NADPH oxidase (Nox)2. miRNA mimics were printed on the self-assembled cell microarray (SAMcell) together with the transfection reagent. Hela cells stably expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) fused with the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) from human Nox2 were seeded on the array. Human Nox2 siRNA was used as positive control (PC) and scrambled miRNA was used as negative control (NC). In total, 266 miRNAs with conserved sequences between humans and mice were screened. After bioinformatics analysis and validation, 3 miRNAs were chosen for further study.

Table 1.

Top listed results of SAMcell

| miRNA | Fold Change | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| miR-106b | 0.90005 | 0.000251 |

| miR-148b | 0.901037 | 7.55E-05 |

| miR-21 | 0.905 | 0.019 |

| miR-135b | 0.915 | 0.00039 |

| miR-296-5p | 0.916 | 0.00053 |

| miR-590-5p | 0.921 | 0.1019 |

| miR-33a | 0.923 | 0.029 |

| Let-7f-1-3p | 0.925 | 0.0498 |

| miR-29c* | 0.926 | 0.004 |

| Let-7i | 0.927 | 0.027 |

| miR-204 | 0.9278 | 0.008 |

| miR-221 | 0.931 | 0.121 |

| miR-190 | 0.934 | 0.117 |

| miR-7 | 0.935 | 0.058 |

| miR-331-3p | 0.936 | 0.046 |

SAMcell, self-assembled cell microarray; miRNA, microRNA.

Table 2.

miRNA-Nox2 predicted binding sites from the Targetscan database

| Sequence | |

|---|---|

| Nox2 3′-UTR Has-miR-106b |

|

| Predicted consequential pairing of target region | 5′-. . .UCUAUGGUUUUGAGAGCACUUUU. . . |

| Predicted consequential pairing of miRNA | 3′-UAGACGUGACAGUCGUGAAAU |

| Nox2 3′-UTR Has-miR-148b |

|

| Predicted consequential pairing of target region | 5′-. . .CCCAGAAUCCUCAGGGCACUGAG. . . |

| Predicted consequential pairing of miRNA | 3′-UGUUUCAAGACAUCACGUGACU |

| Nox2 3′-UTR Has-miR-204 |

|

| Predicted consequential pairing of target region | 5′-. . .UCAAUUUUAGAAUCAAAAGGGAA. . . |

| Predicted consequential pairing of miRNA | 3′-UCCGUAUCCUACUGUUUCCCUU |

| Nox2 3′-UTR Has-miR-204 |

|

| Predicted consequential pairing of target region | 5′-. . .AAAAUAAAAAAGGCAAAAGGGAG. . . |

| Predicted consequential pairing of miRNA | 3′-UCCGUAUCCUACUGUUUCCCUU |

3′-UTR, 3′-untranslated region.

Functional validation of the selected miRNAs.

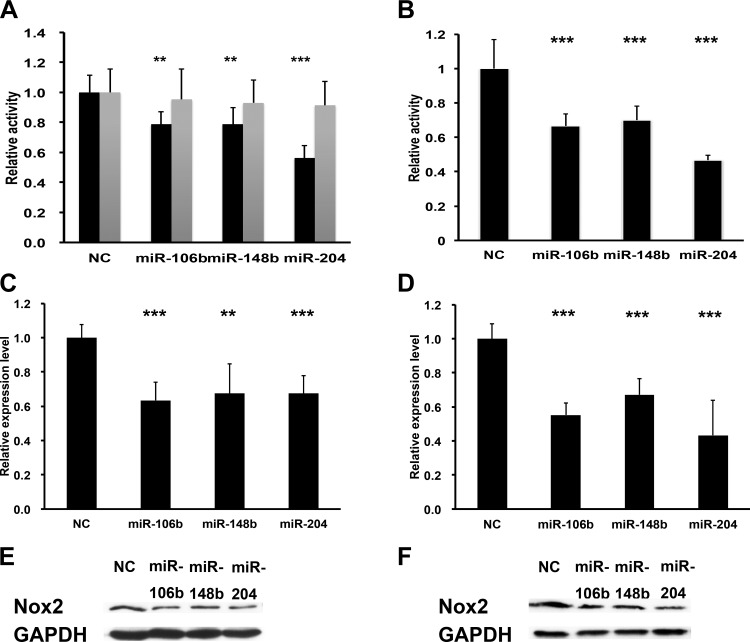

To validate each miRNA’s ability to suppress human Nox2, we performed luciferase assays in 293T cells cloned with the 3′-UTR of Nox2 downstream of luciferase. As shown in Fig. 2A, all of the three miRNAs significantly decreased luciferase expression compared with control (miR-106b = 78.5 ± 8.6%, P < 0.01; miR-148b = 78.6 ± 11.1%, P < 0.01; miR-204 = 56.2 ± 8.4%, P < 0.001). Additionally, we mutated the predicted binding sites in the 3′-UTR and found no effect of the selected miRNAs. To determine whether their regulation was conserved, we also validated the selected miRNAs using mouse Nox2 3′-UTR downstream of luciferase. Similar to human Nox2, luciferase containing mouse Nox2 3′-UTR was also significantly decreased by these miRNAs compared with the control group (miR-106b = 66,6 ± 6.8%, P < 0.001; miR-148b = 70.1 ± 8.2%, P < 0.001; miR-204 = 46.7 ± 2.7%, P < 0.001; Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

miRNAs regulated both human and mouse Nox2 expression. A and B: relative luciferase activity in Hela cells transfected with indicated miRNAs or control vector with human (A) and mouse (B) Nox2 3′-UTR driven reporter constructs; n = 5. Shaded bars in A show 3′-UTR with mutated predicted binding sites (Targetscan). C and D: real-time PCR for Nox2 in PMA-induced THP-1 (C) and RAW 264.7 (D) cells 48 h after transfection with the indicated miRNA or control vector. GAPDH was used as the loading control; n = 3. E and F: immunoblots for Nox2 in PMA-induced THP-1 (E) and RAW 264.7 (F) cells 48 h after transfected with the indicated miRNAs or control vector. GAPDH was used as the loading control. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (t-test).

We also transfected these miRNAs mimics to induced human macrophages (THP-1 cells) and a mouse macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7). Nox2 mRNA and protein levels were detected by real-time PCR and Western blot, respectively. As expected, compared with a scrambled control miRNA group, all three miRNAs decreased both human and mouse Nox2 expression at the gene and protein levels by ~40% (Fig. 2, C and D).

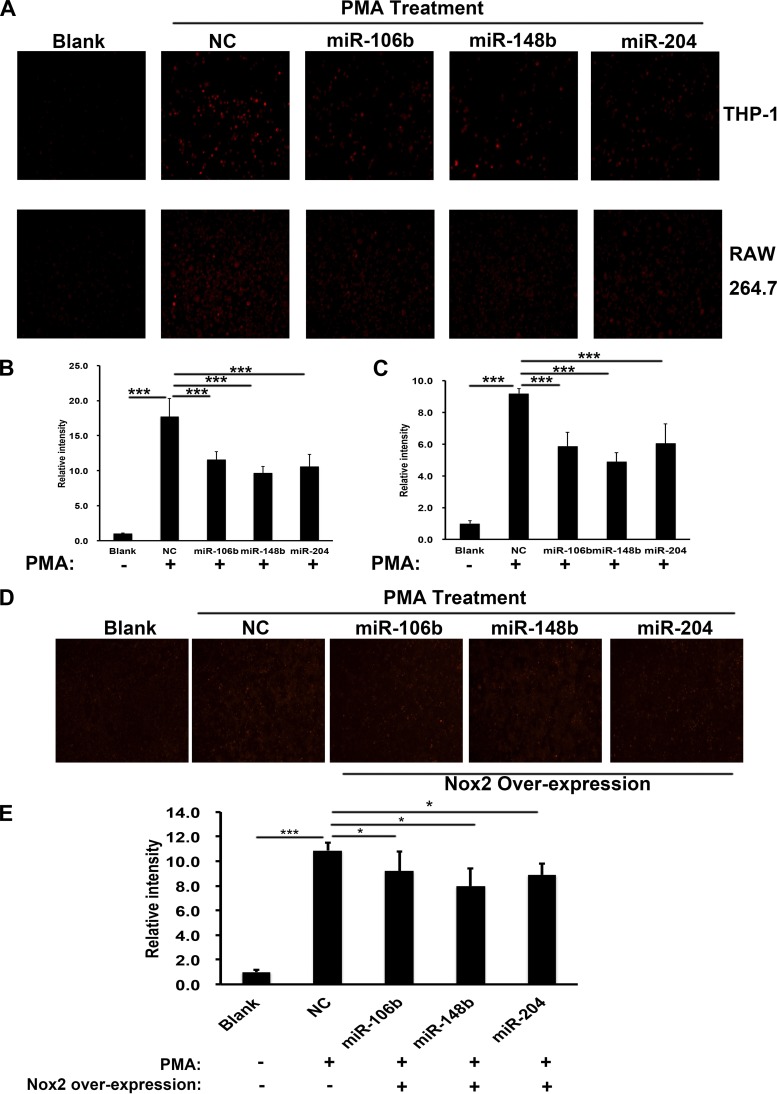

In vitro functional knockdown of Nox2 downstream production.

To determine whether Nox2 knockdown by miRNAs resulted in functional changes, we transfected THP-1-induced and RAW 264.7 macrophages with miRNAs separately, and, 48 h later, they were stimulated with PMA to induce O2− production. ROSstar 650 dye, a fluorescent probe for intracellular ROS, was then added to the cells. Fluorescence intensity was expressed as the fold change in O2− production normalized to basal O2− levels. As shown in Fig. 3A, after stimulation with PMA, O2− production was increased, while each miRNA treatment group showed significantly decreased levels in O2− production compared with the control group in THP-1-induced (top) and RAW 264.7 (bottom) macrophages. Figure 3B shows a quantification of the results for THP-1-induced macrophages and Fig. 3C for RAW 264.7 macrophages. To investigate if the inhibition of O2− production was a result of decreased Nox2, we overexpressed Nox2 protein concurrently with miRNAs transfection. As shown in Fig. 3, D and E, the O2−production level was partially rescued when Nox2 was overexpressed.

Fig. 3.

miRNAs inhibited superoxide production in humans and mice macrophages. A: superoxide production levels in THP-1 (top) and RAW 264.7 (bottom) cells were detected with ROS star dye staining after stimulated by PMA and transfected with the indicated miRNAs or control vector, n = 3. Scar bar = 100 μm. B and C: quantification of superoxide production levels in THP-1 (B) and RAW 264.7 (C) cells by comparing fluorescence intensity of the indicated groups. D and E: representative images (D) and quantification (E) of superoxide production levels in RAW 264.7 when Nox2 was overexpressed together with miRNAs transfection; n = 3. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 (t-test).

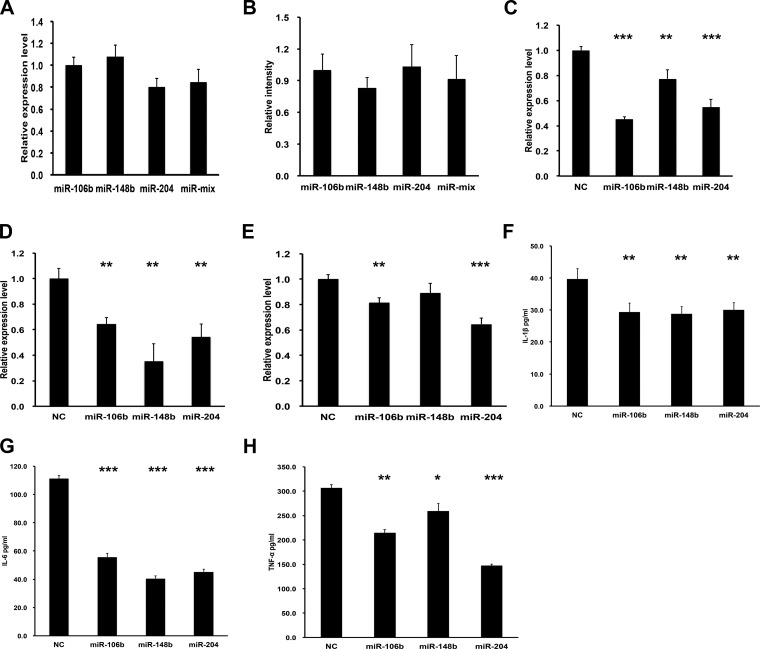

We also examined whether the miRNAs identified were additive and whether there were effects on other inflammatory targets. There was no significant additive effect by delivery of all three miRNAs together compared with the single miRNA alone both for Nox2 expression level and O2− production level (Fig. 4, A and B). We also investigated expression of IL-1α, IL-6, and TNF-α by real-time PCR in RAW 264.7 macrophages after transfection with miRNAs. As shown in Fig. 4, C–E, these miRNAs significantly decreased the mRNA expression level of these proinflammatory genes as well, except for miR-148b on TNF-α. To further identify the effects of miRNAs on the protein level of these three genes, ELISA was used and the expression of secreted proteins was all inhibited when any miRNA was overexpressed, as shown in Fig. 4, F–H.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of miRNA mix and single miRNA function and inhibition on proinflammatory-related genes. A: real-time PCR for Nox2 mRNA in RAW 264.7 after transfection with the indicated miRNA or a mixture of all 3 miRNAs normalized to miR-106b treatment. Data showed no differences between individual miRNAs or combinations; n = 3. B: quantification of relative fluorescence intensity with dihydroethidium (DHE) staining in RAW 264.7 cells after transfection with the indicated miRNA. miR-106b was used as a control. No significant difference among four groups was found; n = 3. C–E: real-time PCR for IL-1β (C), IL-6 (D), and TNF-α (E) mRNA in RAW 264.7 cells after transfection with the indicated miRNA. F–H: ELISA for IL-1β (F), IL-6 (G), and TNF-α (H) protein levels in RAW 264.7 cells; n = 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (t-test).

Nanoparticle uptake by macrophages.

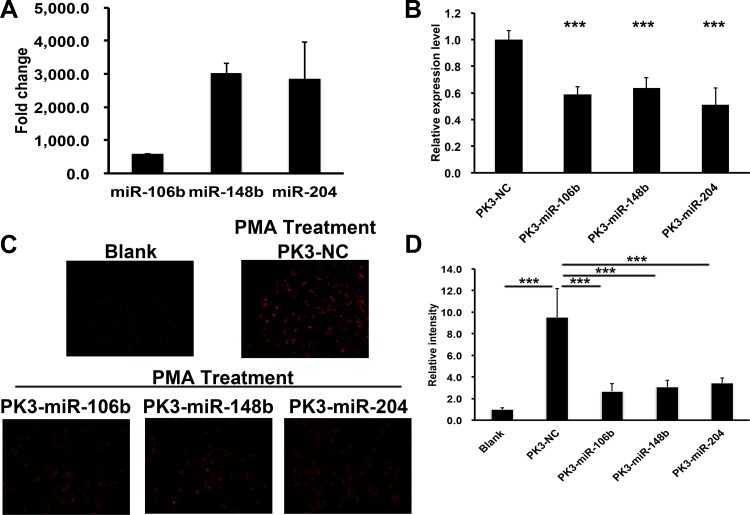

After validation of individual miRNA function on Nox2 expression and downstream O2−production, we sought to validate our previously used in vivo delivery system with miRNA in cultured cells. miRNAs encapsulated within PK3 polymer(PK-miRNA) showed similar loading levels as our prior publications (1 µg/mg particle). Cells were incubated with the indicated PK-miRNA formulation, and expression of the delivered miRNA was evaluated with real-time PCR. As shown in in Fig. 5A, each formulation was able to increase expression of their respective cargo at least 500-fold, indicating effective delivery.

Fig. 5.

Polyketal (PK3)-miRNA nanoparticles reduced Nox2 expression and activity in RAW 264.7 cells. A: fold change of miRNA levels in RAW 264.7 cells after treatment with the indicated PK3-miRNAs nanoparticles by real-time PCR. U6 was used as the loading control; n = 3. B: real-time PCR of Nox2 in RAW 264.7 cells after treatment with the indicated PK3-miRNA or control nanoparticles. GAPDH was used as the loading control; n = 3. C and D: representative images (C) and quantification (D) of superoxide production levels in RAW 264.7 cells treated with the indicated nanoparticles by ROSstar dye; n = 3. ***P < 0.001 (t-test).

We treated RAW 264.7 macrophages with PK-miRNA particles for 48 h, and the Nox2 mRNA expression level was determined by real-time PCR. As shown in Fig. 5B, treatment with any of the particle formulations significantly reduced Nox2 gene expression (miR-106b = 58.9 ± 5.7%, P < 0.001; miR-148b = 63.7 ± 7.9%, P < 0.001; miR-204 = 51.1 ± 12.8%, P < 0.001). O2− production was also measured, and, similar to gene expression, treatment with any PK-miRNA particle significantly decreased production compared with the control group (PK3-NC, Fig. 5, C and D).

PK-miRNA delivery in vivo.

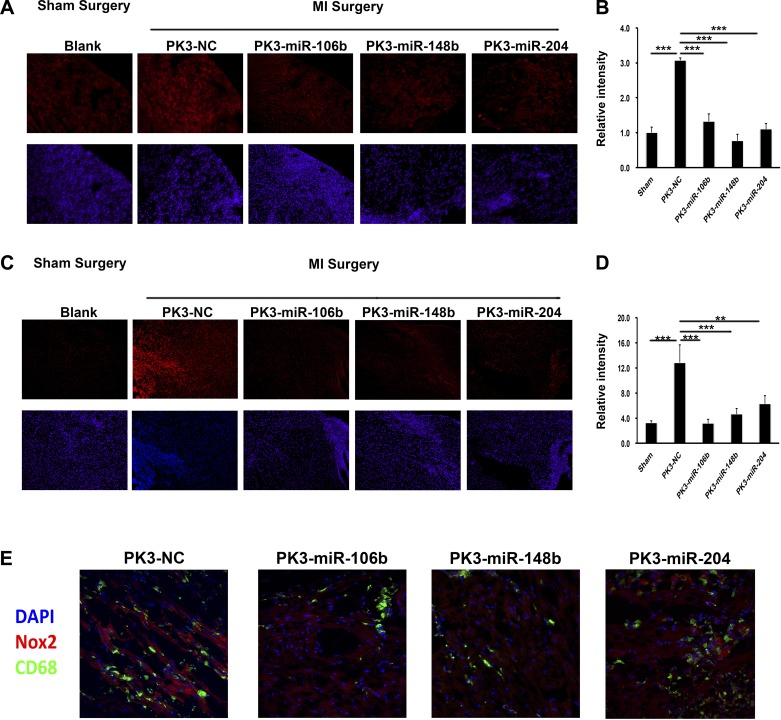

To determine the in vivo efficiency of miRNA-mediated Nox2 suppression, adult male C57BL/6 mice were randomized into five treatment groups. Control mice were subjected to sham surgery, whereas the other four groups received MI surgery followed by injection of PK-miRNA or a negative control scrambled miRNA particle (PK-NC). At 3 days postinjury, hearts were harvested and expression of Nox2 was determined by immunofluorescence staining of frozen sections. As shown in Fig. 6, A and B, there was a significant increase in Nox2 staining with PK-NC treatment after MI compared with sham mice (~3-fold, P < 0.001). Compared with the PK-NC group, each PK-miRNA treatment group demonstrated significantly reduced staining of Nox2 (miR-106b = 43.2 ± 6.8%, P < 0.001; miR-148b = 24.8 ± 6.3%, P < 0.001; miR-204 = 35.9 ± 5.1%, P < 0.001). Additionally, O2− levels were determined by DHE staining on frozen sections. Similar to Nox2 expression levels, each PK-miRNA treatment significantly reduced the elevated DHE staining at least 50% (Fig. 6, C and D). To further identify if Nox2 was specifically inhibited in macrophages, we stained sections for Nox2 and CD68. As shown in Fig. 6E, there was decreased costaining in the PK-miRNA treatment group compared with the PK-NC group.

Fig. 6.

PK3-miRNA nanoparticles inhibited Nox2 expression and activity in vivo. A and B: representative images (A) and quantification (B) of Nox2 (red) levels by in situ immunostaining on frozen sections from the indicated mouse heart tissues. Cell nuclei were stained by Hoechst (blue); n = 5. Scale bar = 100 μm. C and D: representative images (C) and quantification (D) of superoxide production levels by DHE staining on frozen sections from the indicated mouse heart tissues. Cell nuclei were stained by Hoechst; n = 5. Scar bar = 100 μm. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttest). E: representative images of Nox2 (red), CD68 (green), and cell nuclei (blue) by in situ immunostaining on frozen sections.

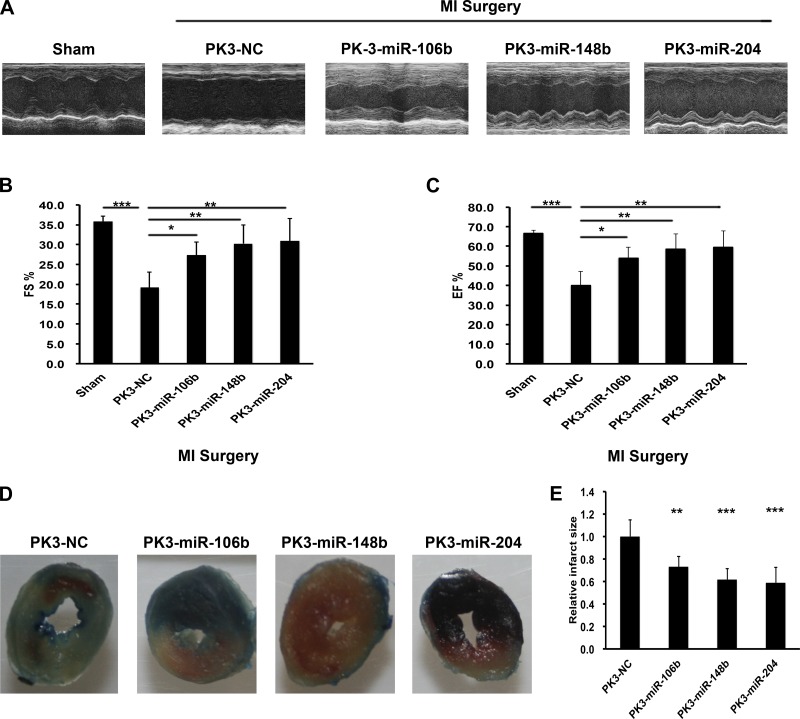

To determine the effect of PK-miRNA delivery on acute cardiac function after MI, echocardiography data were collected 3 days after injury. As shown in Fig. 7, A–C, MI significantly reduced cardiac function as measured in the absolute change in FS and ejection fraction 3 days postinjury. Treatment with each PK-miRNA particle significantly improved function, restoring it to sham levels. To further examine functional changes, we also measured infarct size at 24 h by TTC staining. As the representative images and grouped data show, each PK-miRNA particle significantly inhibited infarct size.

Fig. 7.

PK3-miRNA nanoparticles improved cardiac function after myocardial infarction (MI). A: echocardiographic pictures of mice 3 days after the indicated treatment. B and C: echocardiographic parameters fractional shortening (B) and ejection fraction (C) from the indicated groups of mice; n = 5. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttest). D and E: representative images (D) and grouped data (E) from infarct size experiments; n > 4. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttest).

DISCUSSION

Substantial evidence shows that oxidative stress due to excessive ROS such as O2− plays an important role in the development of post-MI cardiac dysfunction (8, 23). Antioxidant treatment after MI in animal models improves cardiomyocyte survival, attenuates ventricular remodeling, and results in the preservation of left ventricular function (4). NAPDH oxidases are major sources of O2− in the heart, and the family of gp91 proteins (Nox1 to Nox5) is an important catalytic unit of NADPH oxidase (23). Nox2 is mainly expressed in macrophages, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and cardiomyocytes (2) and is significantly increased in the myocardium after MI with the massive influx of inflammatory cells (14, 19). Nox2 is also increased in human cardiomyocytes after MI (14). Nox2 knockout mice are protected from post-MI dysfunction (12, 23), and studies from our own laboratory have shown that siRNA against Nox2 encapsulated in nanoparticles can protect against acute MI dysfunction (29). Therefore, finding additional ways to target Nox2 could be a promising therapeutic approach for preserving function after acute MI.

In the current report, we successfully identified several miRNAs targeting Nox2 with the use of a high-throughput miRNA-target screening system and validated their targeting using a luciferase reporter system with the 3′-UTR of Nox2. We also confirmed their function by testing Nox2 expression and function in both human and mouse macrophage cell lines. To date, there had been no studies that identified a miRNA that directly bound the Nox2 3′-UTR and decreased expression. The SAMcell assay provided a straightforward way to identify miRNAs that target a specific gene. In our previous studies, the performance of this system had been demonstrated using a phenotypic approach to determine miRNAs that regulated processes involved in cancer (35). In this study, miRNAs were selected that were conserved between humans and mice to test potential human targets in mouse models of MI. Three specific miRNAs were chosen for more detailed analysis due to prior publications underscoring their involvement in post-MI healing. After MI, miR-106b reduced apoptosis via inhibition of p21 expression (22) and has also been shown to target the proinflammatory cytokine IL-8 (6). The second hit, miR-148b, has been reported to negatively regulate LPS-induced cytokine production in dendritic cells, including IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α, and plays an important role in immune regulation (21). In addition, a significantly decreased expression of miR-148b was observed in isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury and fibrosis; expression was increased when apocynin treatment was used to reverse this (33). Finally, our third hit, miR-204, was decreased after I/R injury in mice, and overexpression of miR-204 protected the cardiomyocytes against I/R-induced autophagy (32).

After selection of these three miRNAs, their inhibition of both human and mouse Nox2 was validated by several methods. Luciferase assays using the Nox2 3′-UTR demonstrated they could each decrease Nox2 expression directly by canonical miRNA regulation. Real-time PCR and Western blot studies confirmed that all three miRNAs decreased Nox2 levels at the gene and protein levels (Fig. 2, C–F). DHE staining for PMA-induced O2− levels (a surrogate of Nox2 activity) also showed the functional benefit of the miRNA-induced decrease in Nox2 levels.

Once miRNAs were selected and validated, we sought to use an efficient delivery system for targeting macrophages in vivo. Polyketals are a class of delivery vehicles formulated from a class of polymers that contain pH-sensitive, hydrolyzable ketal linkages in their backbone. We had used the polyketal PK3 to deliver miRNA to bone marrow mononuclear cells to induce pluripotency (28). There was no difference in miRNA transfection efficiency between commercial transfection reagent (Oligofactamine) and PK3 nanoparticles (data not shown). Additional published studies from our laboratory demonstrated that PK3 nanoparticles were retained in the myocardium after injection and could be used to deliver siRNA after MI in mice (29). When engaged by macrophages, particles were taken up into phagosome/endosomes where they degrade due to the acidic environment, leading to release of cargo into the cytoplasm of macrophages (over 80% transfection efficiency). In that study, we successfully delivered Nox2 siRNA into cardiac macrophages by PK3 particles and observed a significant improvement in heart function after MI.

Despite our prior study showing beneficial effects of delivery of siRNA to Nox2, delivery of miRNA might have potential advantages. First, miRNA is more natural as there is no siRNA in mammalian cells. miRNA is viewed as endogenous and purposefully expressed products in an organism’s own genome, whereas siRNA is thought to be primarily exogenous in origin, derived directly from viruses, transposons, or transgene triggers (3). Additionally, introduction of too much siRNA could result in nonspecific events due to activation of the innate immune response (17). Second, miRNA could target many genes and sometimes from the same pathways. For example, let-7, which has been shown to be able to directly regulate some key cell cycle proto-oncogenes, e.g., RAS, CDC25a, CDK6, and cyclin D at the same time, was a key regulator of cell proliferation (16). Likewise, miR-23b plays an important role in tumor metastasis since it regulates a cohort of prometastatic targets, including FZD7, MAP3K1, TGFBR2, and PAK2 (36). To validate this hypothesis in this study, we examined expression levels of other proinflammatory genes such as IL-1α, IL-6, and TNF-α by real-time PCR and ELISA in RAW 264.7 cytokines after transfection with miRNAs and found that all miRNAs also targeted other inflammatory genes, although it is unclear as to whether this was indirect or direct.

We next examined the efficacy of these particles in vivo, in a mouse model of MI. Similar to our prior studies, we delivered particles immediately after ligation to the border zone of the infarct. In keeping with published studies (12, 14, 19), both Nox2 levels and O2− levels were significantly increased after MI. While Nox2 levels have been shown to be upregulated in cardiomyocytes, staining indicated upregulation in both cardiomyocyte and noncardiomyocyte origin, likely infiltrating inflammatory cells. Double staining indicated that CD68-positive macrophages had expression of Nox2 that was not present in any PK-miRNA-treated groups. While we did not identify the source of O2−, it was also likely inflammatory cells based on prior studies (4, 23). While it is possible that Nox2 was increased in myocytes, our published studies have shown that polyketals are not efficiently taken up by cardiomyocytes without surface modification of the nanoparticles (11, 20). Thus, any reduction in Nox2 in cardiomyocytes was likely indirect, possibly an effect of reduced local O2− and inflammation. It would be interesting to encapsulate the miRNAs in modified particles and determine whether miRNA-mediated knockdown of Nox2 in cardiomyocytes is sufficient for protection, though this would be unlikely due to the large influx of inflammatory cells. Additionally, we did not measure other ROS, such as H2O2, which could also mediate damage. The role of H2O2 in acute MI is controversial, and it remains a debate as to whether this is a valid target as H2O2 is also involved in important physiological processes. It is also likely that reduced levels of O2− also resulted in decreases in H2O2, and understanding this balance could be an interesting topic for future consideration. After treatment with any PK3-miRNA, Nox2 expression and O2− levels were reduced significantly compared with the empty particle group. More importantly, an improvement in cardiac function and reduction in infarct size were observed in each PK3-miRNA formulation treatment group. These results corroborated reports that knockdown of Nox2 improves cardiac function after MI.

In conclusion, we have found novel miRNA regulation of Nox2 expression using a high-throughput miRNA-target screening method, the SAMcell assay, to narrow down potential targets, specifically miR-106b, 148b, and 204. We validated the results in transfected cells as well as human and mouse macrophages. Combined with our efficient macrophage-specific delivery approach, these miRNAs were able to reduce Nox2 expression and activity in vivo, resulting in improved acute function. With the robust nature of these systems, other inflammatory molecules can be studied to determine optimal miRNA candidates to modulate inflammation in vivo.

GRANTS

We acknowledge the support of the Emory/Georgia Institute of Technology/Peking University Program as well as a Chinese Scholarship Council Fellowship (to J. Yang). This work was also supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-090601 (to M. E. Davis) and National Natural Science Foundation of Chinese Grants 81325010, 81421004, and 31371443.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.Y., M.E.B., H.Z., M.M., Z.Z., S.B., S.Y., and D.T. performed experiments; J.Y., M.E.B., H.Z., M.M., Z.Z., S.B., S.Y., D.T., and M.E.D. analyzed data; J.Y., J.J.X., and M.E.D. interpreted results of experiments; J.Y. prepared figures; J.Y. drafted manuscript; J.Y., J.J.X., and M.E.D. edited and revised manuscript; J.Y., M.E.B., H.Z., M.M., Z.Z., S.B., S.Y., J.J.X., and M.E.D. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Anversa P, Li P, Zhang X, Olivetti G, Capasso JM. Ischaemic myocardial injury and ventricular remodelling. Cardiovasc Res 27: 145–157, 1993. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendall JK, Cave AC, Heymes C, Gall N, Shah AM. Pivotal role of a gp91phox-containing NADPH oxidase in angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Circulation 105: 293–296, 2002. doi: 10.1161/hc0302.103712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136: 642–655, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cave A. Selective targeting of NADPH oxidase for cardiovascular protection. Curr Opin Pharmacol 9: 208–213, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cave AC, Brewer AC, Narayanapanicker A, Ray R, Grieve DJ, Walker S, Shah AM. NADPH oxidases in cardiovascular health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 691–728, 2006. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuang TD, Luo X, Panda H, Chegini N. miR-93/106b and their host gene, MCM7, are differentially expressed in leiomyomas and functionally target F3 and IL-8. Mol Endocrinol 26: 1028–1042, 2012. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ertl G, Frantz S. Healing after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 66: 22–32, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferdinandy P, Schulz R. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite in myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury and preconditioning. Br J Pharmacol 138: 532–543, 2003. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiedler J, Jazbutyte V, Kirchmaier BC, Gupta SK, Lorenzen J, Hartmann D, Galuppo P, Kneitz S, Pena JT, Sohn-Lee C, Loyer X, Soutschek J, Brand T, Tuschl T, Heineke J, Martin U, Schulte-Merker S, Ertl G, Engelhardt S, Bauersachs J, Thum T. MicroRNA-24 regulates vascularity after myocardial infarction. Circulation 124: 720–730, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics–2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 127: e6–e245, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray WD, Che P, Brown M, Ning X, Murthy N, Davis ME. N-acetylglucosamine conjugated to nanoparticles enhances myocyte uptake and improves delivery of a small molecule p38 inhibitor for post-infarct healing. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 4: 631–643, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s12265-011-9292-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grieve DJ, Byrne JA, Siva A, Layland J, Johar S, Cave AC, Shah AM. Involvement of the nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase isoform Nox2 in cardiac contractile dysfunction occurring in response to pressure overload. J Am Coll Cardiol 47: 817–826, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M Jr, Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, Ulrich A, Wardle GS, Dewell S, Zavolan M, Tuschl T. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 141: 129–141, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heymes C, Bendall JK, Ratajczak P, Cave AC, Samuel JL, Hasenfuss G, Shah AM. Increased myocardial NADPH oxidase activity in human heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 41: 2164–2171, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00471-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnnidis JB, Harris MH, Wheeler RT, Stehling-Sun S, Lam MH, Kirak O, Brummelkamp TR, Fleming MD, Camargo FD. Regulation of progenitor cell proliferation and granulocyte function by microRNA-223. Nature 451: 1125–1129, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature06607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson CD, Esquela-Kerscher A, Stefani G, Byrom M, Kelnar K, Ovcharenko D, Wilson M, Wang X, Shelton J, Shingara J, Chin L, Brown D, Slack FJ. The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res 67: 7713–7722, 2007. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Judge AD, Sood V, Shaw JR, Fang D, McClintock K, MacLachlan I. Sequence-dependent stimulation of the mammalian innate immune response by synthetic siRNA. Nat Biotechnol 23: 457–462, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nbt1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 126–139, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nrm2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krijnen PA, Meischl C, Hack CE, Meijer CJ, Visser CA, Roos D, Niessen HW. Increased Nox2 expression in human cardiomyocytes after acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Pathol 56: 194–199, 2003. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S, Yang SC, Kao CY, Pierce RH, Murthy N. Solid polymeric microparticles enhance the delivery of siRNA to macrophages in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res 37: e145, 2009. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Zhan Z, Xu L, Ma F, Li D, Guo Z, Li N, Cao X. MicroRNA-148/152 impair innate response and antigen presentation of TLR-triggered dendritic cells by targeting CaMKIIα. J Immunol 185: 7244–7251, 2010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Z, Yang D, Xie P, Ren G, Sun G, Zeng X, Sun X. MiR-106b and MiR-15b modulate apoptosis and angiogenesis in myocardial infarction. Cell Physiol Biochem 29: 851–862, 2012. doi: 10.1159/000258197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Looi YH, Grieve DJ, Siva A, Walker SJ, Anilkumar N, Cave AC, Marber M, Monaghan MJ, Shah AM. Involvement of Nox2 NADPH oxidase in adverse cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. Hypertension 51: 319–325, 2008. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ørom UA, Lund AH. Experimental identification of microRNA targets. Gene 451: 1–5, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy S, Khanna S, Hussain SR, Biswas S, Azad A, Rink C, Gnyawali S, Shilo S, Nuovo GJ, Sen CK. MicroRNA expression in response to murine myocardial infarction: miR-21 regulates fibroblast metalloprotease-2 via phosphatase and tensin homologue. Cardiovasc Res 82: 21–29, 2009. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seshadri G, Sy JC, Brown M, Dikalov S, Yang SC, Murthy N, Davis ME. The delivery of superoxide dismutase encapsulated in polyketal microparticles to rat myocardium and protection from myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomaterials 31: 1372–1379, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sirker A, Murdoch CE, Protti A, Sawyer GJ, Santos CX, Martin D, Zhang X, Brewer AC, Zhang M, Shah AM. Cell-specific effects of Nox2 on the acute and chronic response to myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 98: 11–17, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sohn YD, Somasuntharam I, Che PL, Jayswal R, Murthy N, Davis ME, Yoon YS. Induction of pluripotency in bone marrow mononuclear cells via polyketal nanoparticle-mediated delivery of mature microRNAs. Biomaterials 34: 4235–4241, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Somasuntharam I, Boopathy AV, Khan RS, Martinez MD, Brown ME, Murthy N, Davis ME. Delivery of Nox2-NADPH oxidase siRNA with polyketal nanoparticles for improving cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Biomaterials 34: 7790–7798, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tay Y, Zhang J, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature 455: 1124–1128, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature07299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomson DW, Bracken CP, Goodall GJ. Experimental strategies for microRNA target identification. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 6845–6853, 2011. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao J, Zhu X, He B, Zhang Y, Kang B, Wang Z, Ni X. MiR-204 regulates cardiomyocyte autophagy induced by ischemia-reperfusion through LC3-II. J Biomed Sci 18: 35, 2011. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-18-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Q, Cui J, Wang P, Du X, Wang W, Zhang T, Chen Y. Changes in interconnected pathways implicating microRNAs are associated with the activity of apocynin in attenuating myocardial fibrogenesis. Eur J Pharmacol 784: 22–32, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Y, Cheng HW, Qiu Y, Dupee D, Noonan M, Lin YD, Fisch S, Unno K, Sereti KI, Liao R. MicroRNA-34a Plays a Key Role in Cardiac Repair and Regeneration Following Myocardial Infarction. Circ Res 117: 450–459, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin S, Fan Y, Zhang H, Zhao Z, Hao Y, Li J, Sun C, Yang J, Yang Z, Yang X, Lu J, Xi JJ. Differential TGFβ pathway targeting by miR-122 in humans and mice affects liver cancer metastasis. Nat Commun 7: 11012, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang H, Hao Y, Yang J, Zhou Y, Li J, Yin S, Sun C, Ma M, Huang Y, Xi JJ. Genome-wide functional screening of miR-23b as a pleiotropic modulator suppressing cancer metastasis. Nat Commun 2: 554, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Liu D, Chen X, Li J, Li L, Bian Z, Sun F, Lu J, Yin Y, Cai X, Sun Q, Wang K, Ba Y, Wang Q, Wang D, Yang J, Liu P, Xu T, Yan Q, Zhang J, Zen K, Zhang CY. Secreted monocytic miR-150 enhances targeted endothelial cell migration. Mol Cell 39: 133–144, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.