This study identified a novel role of neuregulin-1 (NRG-1)/ERBB signaling in the control of proinflammatory activation of monocytes. These results further improve our fundamental understanding of cardioprotective effects of NRG-1 in patients with heart failure.

Keywords: ERBB receptor tyrosine kinase, heart failure, inflammation, inflammatory cytokine, neuregulin

Abstract

Immune activation in chronic systolic heart failure (HF) correlates with disease severity and prognosis. Recombinant neuregulin-1 (rNRG-1) is being developed as a possible therapy for HF, based on the activation of ERBB receptors in cardiac cells. Work in animal models of HF led us to hypothesize that there may be direct effects of NRG-1 on immune system activation and inflammation. We investigated the expression of ERBB receptors and the effect of rNRG-1 isoform glial growth factor 2 (GGF2) in subpopulations of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB MNCs) in subjects with HF. We found that human monocytes express both ERBB2 and ERBB3 receptors, with high interindividual variability among subjects. Monocyte surface ERBB3 and TNF-α mRNA expression were inversely correlated in subjects with HF but not in human subjects without HF. GGF2 activation of ERBB signaling ex vivo inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α production, specifically in the CD14lowCD16+ population of monocytes in a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent manner. GGF2 suppression of TNF-α correlated directly with the expression of ERBB3. In vivo, a single dose of intravenous GGF2 reduced TNF-α expression in PB MNCs of HF subjects participating in a phase I safety study of GGF2. These results support a role for ERBB3 signaling in the regulation of TNF-α production from CD14lowCD16+ monocytes and a need for further investigation into the clinical significance of NRG-1/ERBB signaling as a modulator of immune system function.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study identified a novel role of neuregulin-1 (NRG-1)/ERBB signaling in the control of proinflammatory activation of monocytes. These results further improve our fundamental understanding of cardioprotective effects of NRG-1 in patients with heart failure.

cardiac injury and dysfunction are associated with increased expression of factors that activate the immune system (20, 42). Many studies have reported significant changes in the number of immune cells, mostly monocytes, during the progression of chronic systolic heart failure (HF) (1, 3, 5, 55, 57). Plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines are elevated in HF patients and correlate with poor clinical outcome (16). However, there is considerable interindividual variability in the magnitude and direction of immune responses. A better understanding of the immune involvement in HF in each patient is needed to develop successful immune-modulating therapies (18, 19). Identification of new immunomodulatory signaling pathways, along with markers predicting clinical benefit for individual patients, could potentially be used in therapy for chronic HF.

Neuregulin-1 (NRG-1), an endogenous activator of ERBB receptors, represents a promising therapy for the treatment of various forms of HF. NRG-1/ERBB signaling plays an important role in the regulation of adaptation of the cardiovascular system to stress (23, 34–36). Recently, effects of ERBB ligands, including the recombinant human EGF domain of NRG-1β (rhNRG-1; β2-isoform) as well as glial growth factor 2 (GGF2; β3-isoform), have been evaluated as potential therapies for HF. Both daily infusions of rhNRG-1 (21) and a bolus injection of GGF2 (a.k.a. cimaglermin) resulted in improved cardiac function in patients with HF (37, 38). In a large animal model of HF, GGF2 treatment was associated with suppression of inflammation and fibrosis, in association with improved cardiac function, suggesting direct effects of NRG-1/ERBB signaling on inflammation.

There is limited indirect evidence that NRG-1/ERBB signaling may also contribute to inflammatory cell responses associated with cardiovascular diseases. Endothelial cell-derived NRG-1β prevents accumulation of leukocytes in ischemic and reperfused myocardium (26), suggesting effects of NRG-1β on adhesion and migration of immune cells. Reduced NRG-1β bioavailability was associated with higher levels of proinflammatory cytokine expression in immune cells (41). We have recently shown that ERBB receptors are expressed in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB MNCs) (49).

Collectively, these findings led us to hypothesize that NRG-1 has direct effects on PB MNC function. We analyzed the expression of ERBB receptors on PB MNC in subjects with and without HF using flow cytometry. We found that cell surface expression of ERBB3 on PB MNCs inversely correlates with expression of TNF-α in subjects with HF. We demonstrated further, both in vitro and in vivo, that GGF2 activation of ERBB signaling modulates the expression of TNF-α, specifically in the CD14low human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR+/CD16+ population of monocytes.

METHODS

Study population (subjects).

The study population with HF consisted of subjects recruited to participate in a first in-human phase I single ascending dose study of cimaglermin (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01258387; NRG-1β3, GGF2) (38). All HF subjects were New York Heart Association class 2–3 and were maintained on an optimal medical regimen for at least 3 mo before enrollment. Full details of the enrollment criteria have been reported elsewhere (38). Briefly, this study enrolled both ischemic and nonischemic systolic dysfunction, stable HF subjects. The majority of the enrolled subjects were male (83%) and Caucasian (90%). The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 26%, and mean age was 57 yr. Isolated monocytes and total RNA baseline samples from 25 of the 30 subjects recruited into cohorts 3–7 of this 7-cohort study were available for analysis. Three hours postdose, monocyte and RNA samples were only available for analysis from subjects recruited to cohorts 4 and 5. The study population without HF was recruited under a separate protocol. Per protocol, only subjects without any known history of chronic disease or heart disease were recruited. The mean age of this cohort was 55 yr, 67% were male, and 100% were Caucasian. All participants gave written informed consent. Both studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University.

Isolation of PB MNCs and enrichment of monocytes.

Venous blood (10 ml) was collected from HF and control subjects using BD Vacutainer EDTA tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The total number of white blood cells was determined after erythrocyte lysis with ammonium chloride lysing solution (150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM NaHCO3, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). MNCs (PB MNCs) were isolated from blood on Ficoll-Paque Premium gradient (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden) within 4−6 h of drawing and cryopreserved in FCS:dimethyl sulfoxide (9:1) using a slow temperature-lowering method (Mr. Frosty polyethylene vial holder, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Cells were stored in liquid nitrogen for ≥1 wk before being thawed. Viability and recovery were measured using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) exclusion.

Monocytes were purified from PB MNCs using a magnetic-activated cell sorting negative selection protocol. Negative selection was chosen to obtain a population of “untouched” monocytes to avoid antibody-dependent activation of monocytes. In brief, PB MNCs were incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated CD3 (UCHT1), CD19 (HIB19), CD56 (HCD56), and CD235a (HI264) (all from BioLegend, San Diego, CA) and anti-PE MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA) followed by depletion of positively stained cells using LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec). A small aliquot of flowthrough containing monocytes was analyzed after additional incubation with CD14 (HCD14) and CD16 (3G8) antibodies (BioLegend) using flow cytometry.

Reagents.

RPMI-1640 medium was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. rhGGF2 (NRG-1β3; United States-adopted name: cimaglermin alfa) was provided by Acorda Therapeutics (Ardsley, NY). LPS from Escherichia coli (055:B5), human recombinant insulin, DAPI, and BSA (heat shock fraction) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor wortmannin was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), and brefeldin A solution was from Thermo Fisher Scientific. For experiments that involved cell stimulation, final concentrations of dimethyl sulfoxide (cell culture grade, Sigma-Aldrich) did not exceed 0.1%.

Flow cytometry.

MNCs (106 cells/ml) were treated with Human TruStain FcX (BioLegend) to prevent nonspecific binding followed by incubation with the relevant antibodies for 25 min at 4°C. Cell surface antigens were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-human CD3 (UCHT1), PeCy7-conjugated CD14 (HCD14), anti-HLA-DR-PeCy5 (L243), anti-CD19-allophycocyanin (HIB19), and anti-CD16-Brilliant Violet 650 (3G8) antibodies (all from BioLegend). ERBB receptors were assayed using PE-conjugated anti-human ERBB2 (Fab1129P) and IgG2B (IC0041P) isotype-matched control, ERBB3 (Fab3481P) and IgG1 (IC002P) control, and ERBB4 (Fab11311P) and IgG2A (IC003P) isotype control. Allophycocyanin-conjugated ERBB2 (Fab1129A) antibody was used to determine coexpression of ERBB2 and ERBB3. All anti-ERBB antibodies and controls were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Cell surface expression of ERBB receptors, represented as the difference in mean fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI), was calculated by subtracting geometric MFI of isotype-matched controls from geometric MFI of ERBB-specific antibodies.

For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). PE-conjugated anti-human TNF-α (MAb11) and IgG1-PE (MOPC-21) isotype-matched control antibodies (BioLegend) were used to determine the intracellular level of TNF-α protein. Phosphorylation of Akt (pAkt) was measured using anti-pAkt (D9E, Alexa fluor 488 conjugate) and rabbit (DA1E) IgG XP Isotype Control (both antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Data acquisition was performed on LSRII flow cytometers (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using WinList 5.0 software. Viable and nonviable cells were distinguished using DAPI or LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Stain kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Antigen negativity was defined as having the same fluorescence intensity as the isotype-matched control antibody.

Microarrays.

Total RNA from whole blood collected in EDTA tubes was isolated using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quality assessment of RNA, hybridization to Affymetrix human genome arrays, and data acquisition were performed by the Genome Sciences Resource Microarray Core at Vanderbilt University. Raw data were robust multiarray analysis normalized followed by a paired Student’s t-test or ANOVA, where appropriate, using Genomics Suite 6.6 (Partek, St. Louis, MO). Genes with P < 0.05 and fold differences of >1.5 were considered significantly altered.

Real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from PB MNCs using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). One microgram of total DNase-treated RNA was used to generate cDNA with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI) and random hexamers (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RT-PCR was performed using the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific), as previously described elsewhere (48). Primer sequences for human cytokines and growth factors are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers for RT-PCR used in this study

| Target | Forward Primer (5′–3′) | Reverse Primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1B | GTACCTGTCCTGCGTGTTGAA | TGAAGACAAATCGCTTTTCCATC |

| IL-6 | CACAGACAGCCACTCACCTC | TTTTCTGCCAGTGCCTCTTT |

| IL-8 | TGCCAAGGAGTGCTAAAG | TCCACAACCCTCTGCAC |

| IL-10 | GGTGATGCCCCAAGCTGA | TCCCCCAGGGAGTTCACA |

| VEGFA | GGGCAGAATCATCACGAAGTG | ATTGGATGGCAGTAGCTGCG |

| Transforming growth factor-β | ACTACTACGCCAAGGAGGTCAC | CTTCTCGGAGCTCTGATGTG |

| TNF-α | AGCCCATGTTGTAGCAAACC | TGAGGTACAGGCCCTCTGAT |

| β-Actin | CGCCCCAGGCACCAGGGC | GGCTGGGGTGTTGAAGGT |

Analysis of TNF-α production.

PB MNCs were resuspended in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium at a concentration of 106 cells/ml and stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS. Secretion of TNF-α in culture media was measured using ELISA kits (R&D Systems).

Flow cytometric analysis PB MNCs (105 cells/ml) were resuspended in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium, containing 0.5% BSA and 3 µg/ml Brefeldin A. Cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 10 ng/ml LPS for 5 h and analyzed for intracellular TNF-α.

Western blot analysis.

Monocytes were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Total protein concentrations were quantified with the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of protein (40–60 μg/well) were resolved in 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Rabbit polyclonal anti-pAkt (Ser473) and total Akt (C67E7) antibodies were used at 1:1,000 dilutions (both from Cell Signaling Technology). After treatment with goat anti-rabbit peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), the bands were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence method.

Quantification of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate level.

The peripheral blood monocytes (purified) were incubated in serum-free RPMI medium overnight. Cells were then centrifuged, resuspended in serum-free RPMI at a density of 5 × 106 cell/ml, and incubated in the absence or presence of 30 ng/ml GGF2 for 10 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of ice-cold TCA to a final concentration of 10% (wt/vol), and the phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) level was quantified as previously described (14). In brief, phospholipids were obtained after extraction using a system of MeOH:CHCl3 (2:1) followed by MeOH:CHCl3:12 M HCl (80:40:1). The organic phase was collected after centrifugation with CHCl3/HCl, and samples were dried and resuspended in PBS-Tween + 3% protein stabilizer (provided by the Echelon kit, Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, UT). Samples were then sonicated in an ice-water bath, vortexed, and spun down. The level of PIP3 was measured using ELISA kits (K-1000, Echelon Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Normally distributed variables are expressed as means ± SE. Comparisons between two groups were performed using two-tailed unpaired t-tests. Comparisons among several treatment groups were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests. Data are expressed as median values with interquartile ranges (IQRs) when distributions are skewed. For variables with skewed distributions, pairwise comparisons of median values were examined using the Mann-Whitney test. A Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank was used to compare different subjects within a matched-pairs study design. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

ERBB2 and ERBB3 receptors are expressed on human monocytes.

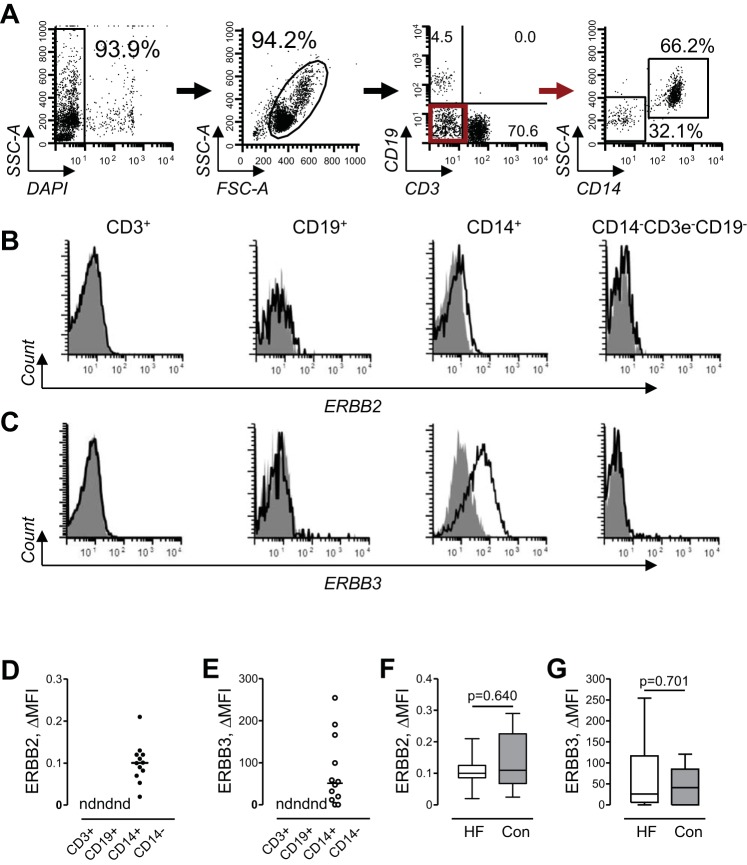

We performed a flow cytometric analysis of ERBB2 and ERBB3 cell surface expression in subpopulations of PB MNCs. Figure 1A shows our gating strategy to define subpopulations of lymphocytes and myeloid cells. With the examination of multiple cell surface markers simultaneously, we identified phenotypically distinct cell subpopulations corresponding to CD3 T lymphocytes, CD19 B lymphocytes, CD14 monocytes, and CD3/CD19/CD14 triple-negative cells (mostly natural killer cells). We evaluated the expression of ERBB receptors in all of these subpopulations of PB MNCs obtained from patients with HF. Representative cytofluorimetric histograms of ERBB2 and ERBB3 expression from one subject are shown in Fig. 1, B and C, respectively. No expression of ERBB receptors was detected on CD3 T lymphocytes, CD19-positive B lymphocytes, and CD3/CD19/CD14 triple-negative cells (Fig. 1, D and E). Thus, monocytes are the only subpopulation of PB MNCs that expresses ERBB2 and ERBB3 receptors.

Fig. 1.

Gating strategy and flow cytometric analysis of ERBB receptor expression in subpopulations of PB MNCs. A, left to right: peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB MNCs) were initially gated as a DAPI-negative population to exclude dead cells (first dot plot, rectangle gate). After adjustment of live cells to singlets using forward-scatter area (FSC-A)/forward-scatter height dot plot (not shown), MNCs were gated (second dot plot, oval gate), and the subpopulation of T lymphocytes (third dot plot, bottom right quadrant) and B lymphocytes (third dot plot, top left quadrant) were distinguished by expression of CD3 and CD19 cell markers. CD3/CD19 double-negative cells (third dot plot, bottom left quadrant, red gate) were additionally separated by expression of CD14 into subpopulations of CD14-negative cells and CD14-positive monocytes (fourth dot plot). SSC-A, side-scatter area. The red arrow indicates that cells from the red gate were analyzed further for cell surface expression of CD14, as shown in the next dot plot to the right. B and C: representative flow cytometric histograms of ERBB2 (B) and ERBB3 (C) cell surface expression in T lymphocytes (CD3+), B lymphocytes (CD19+), monocytes (CD14+), and CD14-negative cell subpopulations (CD14−CD3e−CD19−) of PB MNCs. Unshaded histograms represent ERBB2 (B) or ERBB3 (C), and gray-shaded histograms show isotype-matched antibodies. D and E: graphical representation of cell surface expression of ERBB2 (D) and ERBB3 (E) in major subpopulations of PB MNCs. Data are expressed as changes in mean fluoresence intensity (ΔMFI), and scatter dot plots and horizontal lines indicate median values; n = 12. nd, Not detected. F and G: expression of ERBB2 (F) and ERBB3 (G) on cell surface of monocytes obtained from subjects with heart failure (HF) or control (Con) subjects. Data are expressed as ΔMFI and presented in standard percentile format (minimum; 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles; and maximum). Differences between subjects with HF (n = 25) and control subjects (n = 14) were examined using a Mann-Whitney test. P values are indicated.

Within ERBB-expressing monocytes, we did not observe distinct clusters of ERBB expression but rather a continuous spectrum from ERBB-negative cells to cells expressing high levels of ERBB receptors. In HF subjects but not control subjects, we observed higher interindividual variability in ERBB3 receptor-specific MFI compared with ERBB2 MFI, with calculated coefficient of quartile dispersion (7) values of 0.90 and 0.18, respectively. Although interindividual variability in ERBB3 expression appeared to be greater in HF subjects, the expression of ERBB2 or ERBB3 receptors was similar in HF and control groups (Fig. 1, F and G).

Cell surface expression of ERBB3 on monocytes is inversely correlated with TNF-α in HF.

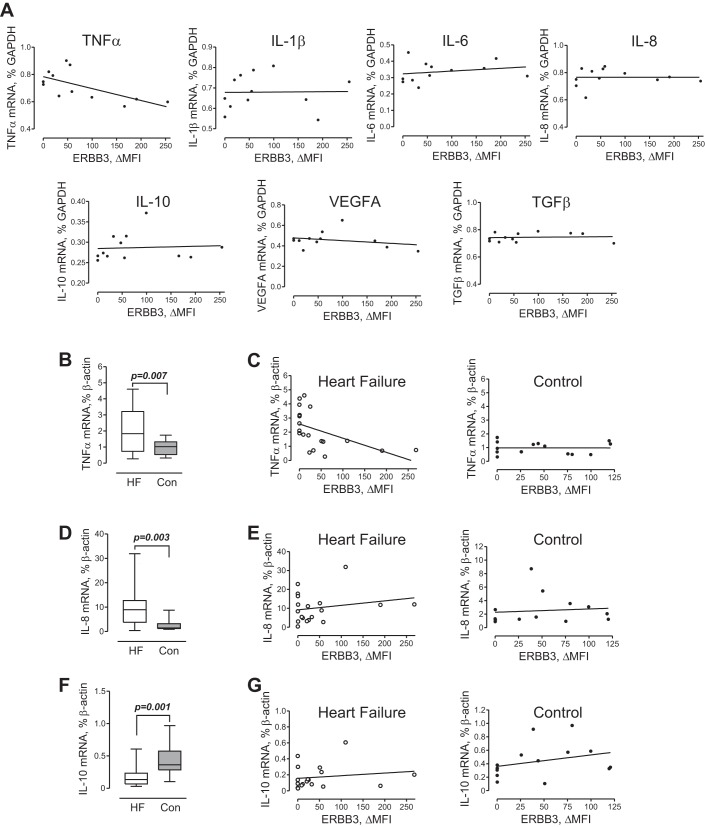

Proinflammatory cytokines secreted by activated monocytes are known to contribute to the pathogenesis of HF. To determine if the expression of ERBB3 on human monocytes is associated with the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, we analyzed whole blood transcript expression by Affymetrix HuGene 1.0 microarrays in HF subjects. A strong inverse correlation was found between the cell surface expression of ERBB3 and TNF-α mRNA levels but not IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, VEGF, and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (Fig. 2A). This relationship was validated by analyzing the expression of cytokines and growth factors in PB MNCs of subjects with HF versus control subjects using real-time PCR. In parallel with flow cytometric analysis shown in Fig. 1, F and G, MNCs were saved and used for the isolation of total RNA and analysis of the expression of cytokines and growth factors associated with monocyte activation, viz. IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, VEGF, and TGF-β. We found higher expression of TNF-α mRNA in PB MNCs of HF patients compared with control subjects (Fig. 2C). Since monocytes represent a major source of TNF-α, we determined their numbers within a mononuclear fraction in HF and control subjects. No differences were found in percentage and absolute numbers of monocytes, including subpopulations of CD14+CD16− and CD14+CD16+ cells, between the two groups (Table 2). Correlation analysis revealed that higher levels of TNF-α mRNA were indeed associated with lower levels of ERBB3 cell surface expression (Fig. 2C), thus confirming the microarray results (Fig. 2A). In contrast, no correlation was found between ERBB3 cell surface expression and TNF-α mRNA in PB MNCs of control subjects. IL-8 expression was also higher in HF subjects (Fig. 2D). However, ERBB3 did not correlate with IL-8 or IL-10 expression (Fig. 2, E and G). Furthermore, we found no significant difference in the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, VEGF, or TGF-β between groups (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Association between cell surface ERBB3 and mRNA expression of cytokine and growth factors. A: microarray data. The correlation between cell surface expression of ERBB3 and TNF-α mRNA (rs = −0.66, P = 0.023), IL-1β (rs = 0.016, P = 0.6023), IL-6 (rs = 0.363, P = 0.245), IL-8 (rs = 0.076, P = 0.812), IL-10 (rs = 0.251, P = 0.429), VEGF (rs = −0.258, P = 0.416), and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (rs = 0.097, P = 0.762) is shown. Total RNA was isolated from whole blood of 12 subjects with HF. B: expression of TNF-α mRNA in a mononuclear fraction of HF and control subjects. C: correlation between ERBB3 and TNF-α mRNA in HF subjects (rs = −0.682, P = 0.001) and control subjects (rs = −0.042, P = 0.886). D and E: mRNA expression of IL-8 (D) and correlation between ERBB3 and IL-8 in HF subjects (rs = 0.041, P = 0.866) or control subjects (rs = 0.333, P = 0.244; E). F and G: mRNA expression of IL-10 (F) and correlation between ERBB3 and IL-10 in HF (rs = 0.146, P = 0.550) or control (rs = 0.395, P = 0.162; G) subjects. B, D, and F: data are expressed as ΔMFI and presented in standard percentile format (minimum; 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles; and maximum). Differences between HF (n = 25) and control (n = 14) subjects were examined using a Mann-Whitney test. P values are indicated.

Table 2.

Percentage and absolute numbers of monocytes in peripheral blood of patients with heart failure and control subjects

| Heart Failure | Control | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % CD14+CD16−† | 70.2 (65.3–76.9) | 75.3 (72.0–78.4) | 0.082 |

| % CD14+CD16+ | 11.8 (4.1–16.8) | 12.8 (9.8–16.6) | 0.512 |

| HLA-DR+CD19−, cells/μl | 272 (121–508) | 313 (224–354) | 0.826 |

| CD14+CD16−, cells/μl | 193 (89–418) | 229 (141–276) | 0.221 |

| CD14+CD16−, cells/μl | 31 (14–55) | 34 (21–48) | 0.123 |

| Mononuclear cells, cells/μl | 1,501 (1,050–2,150) | 1,265 (1,090–1,620) | 0.334 |

Data are presented as medians (interquartile ranges).

Differences between patients with heart failure (n = 25) and control subjects (n = 14) were examined using a Mann-Whitney test.

Percentages of CD16-negative and -positive monocytes were determined within the subpopulation of HLA-DR+CD19− cells.

GGF2, an ERBB receptor agonist, downregulates LPS-induced TNF-α production in CD14lowHLA-DR+ (CD16+) monocytes.

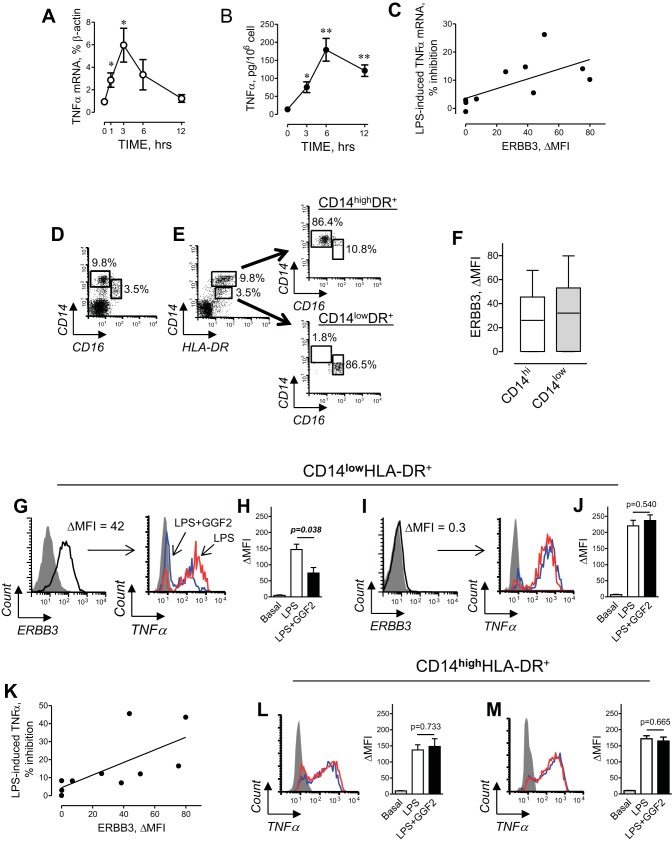

LPS (a.k.a. endotoxin) is a potent activator of TNF-α production in human monocytes (54). It has also been reported that endotoxin may contribute to low-grade inflammation seen in HF patients (11, 33, 51). Therefore, we conducted studies in ex vivo short-term culture of PB MNCs to examine if ERBB receptor activation regulates LPS-induced TNF-α production. Analysis of time-dependent changes in PB MNCs obtained from non-HF control subjects revealed that 10 ng/ml LPS induces TNF-α mRNA expression, which peaked at 3 h, and protein secretion at 6 h (Fig. 3, A and B). Incubation of MNCs with 30 ng/ml GGF2 decreased the LPS-induced TNF-α mRNA expression from median 4.8% (IQR: 3.3–6.4) to 4.3% (IQR: 2.6–6.1) of β-actin expression (P = 0.004, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). The inhibitory effect of GGF2 correlated directly with the expression of ERBB3 receptors on monocytes (Fig. 3C), providing further support for the regulation of TNF-α expression by ERBB3 signaling.

Fig. 3.

Effect of GGF2 on TNF-α production in human PB monocytes. A and B: time course of TNF-α mRNA expression (A) and protein secretion (B) from human PB MNCs induced by 10 ng/ml LPS. Data represent means ± SE from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. basal (0) by unpaired t-test. C: correlation between the inhibitory effect of GGF2 (30 ng/ml) on LPS-induced TNF-α mRNA and cell surface expression of ERBB3 (rs = 0.733, P = 0.020). D: representative flow cytometric dot plot showing subsets of CD16neg and CD16pos monocytes within PB MNCs. E: distribution of CD16neg and CD16pos cells in subpopulations of CD14hi and CD14low monocytes. Left to right: representative dot plot demonstrating gating of CD14high (top gate) and CD14low (bottom gate) HLA-DR+ monocytes. The majority of CD14highHLA-DR+ cells are represented by CD16-negative cells; CD14lowHLA-DR+-CD16-positive monocytes. F: levels of ERBB3 receptor expression on CD14high (open) and CD14low (shaded) HLA-DR+ monocytes. G–J: effect of GGF2 on LPS-induced TNF-α production in CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes. G: ERBB3-expressing “nonclassical” monocytes. Red histogram, LPS-induced TNF-α; blue, the effect of GGF2; gray, isotype control. H: graphical representation of data from flow cytometric analysis of TNF-α production. I: CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes were characterized by the absence of ERBB3 expression. J: GGF2 had no effect in ERBB3-negative cells. K: correlation between the inhibitory effect of GGF2 on LPS-induced TNF-α production and cell surface expression of ERBB3 (rs = 0.769, P = 0.013) in a subset of CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes. L and M: GGF2 had no effect on LPS-induced TNF-α production in a subset of CD14highHLA-DR+ monocytes. Representative histograms demonstrating the effect of GGF2 (blue) on LPS-induced (red) TNF-α production in (L) ERBB3+ and (M) ERBB3− monocytes are shown. H, J, L, and M: data are means ± SE obtained from three different isolations of PB MNCs from one (H and L) ERBB3-positive and one (J and M) ERBB3-negative control subject. P values indicate significance level calculated by unpaired t-test.

We next examined the effects of ERBB3 activation on LPS-induced TNF-α production in distinct monocyte subsets. The population of human PB CD14+ monocytes consists of two major subsets, commonly distinguished by their expression of Fcγ receptor III (a.k.a. CD16; Fig. 3D). Because LPS is known to downregulate the cell surface expression of CD16, we used an alternative cell surface marker, previously used to distinguish subsets of human PB MNCs (6). As shown in Fig. 3, D and E, CD14highHLA-DR+ cells are primarily CD16− cells, whereas CD14lowHLA-DR+ are primarily CD16+ monocytes. Thus, HLA-DR can be used as a surrogate marker of PB MNC major subsets instead of CD16. Next, we examined cell surface expression of ERBB3 in CD14hi and CD14low monocytes. Although the median expression of ERBB3 was slightly less in CD14highHLA-DR+ monocytes compared with that in CD14low HLA-DR+ cells, we found no significant difference in the expression of ERBB3 between two subsets of monocytes (Fig. 3F).

In subjects with high ERBB3 cell surface expression on CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes (Fig. 3G), we found that GGF2 decreased LPS-induced TNF-α production (Fig. 3H). In contrast, GGF2 had no effect on LPS-induced TNF-α production in CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes from subjects lacking the expression of ERBB3 (Fig. 3, I and J). The inhibitory effect of GGF2 on LPS-induced TNF-α production in CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes strongly correlated with the expression of ERBB3 on their surface (Fig. 3K). Thus, ERBB3 receptor expression is required for GGF2 modulation of TNF-α production in human CD14low HLA-DR+ monocytes. In contrast to CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes, we found no effect of GGF2 on LPS-induced TNF-α production in CD14highHLA-DR+ subset of monocytes (Fig. 3, L and M), irrespective of their expression levels of ERBB3. Thus, our data clearly demonstrate that agonist-dependent activation of ERBB3 results in inhibition of TNF-α mRNA expression and protein production, specifically in the CD14lowHLA-DR+ subset of monocytes.

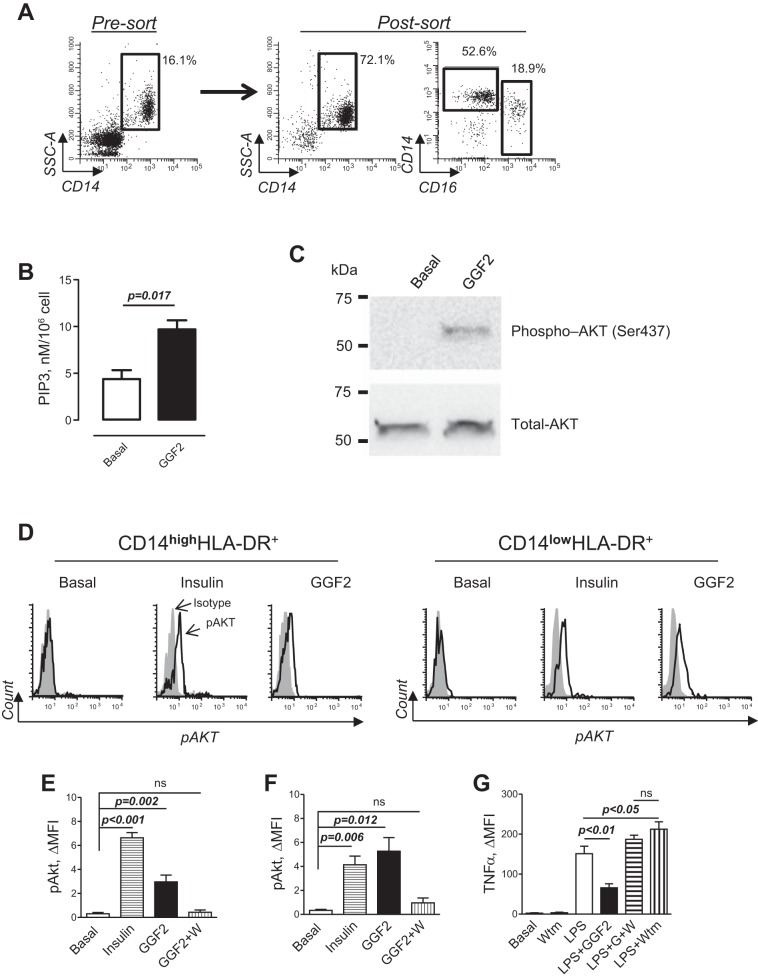

GGF2 modulates LPS-induced TNF-α in human PB monocytes via PI3K.

ERBB3 is known to activate PI3K via its multiple docking sites for the p85 regulatory subunit (10, 27). PI3K/Akt signaling has previously been characterized as anti-inflammatory in human monocytes (24, 32, 44). To examine the functional role of NRG/ERBB signaling, we first purified PB monocytes using immunomagnetic cell separation. To avoid antibody-dependent stimulation of monocytes during purification, we performed negative selection, depleting CD3 T cells, CD19 B lymphocytes, CD56 natural killer cells, and CD235a erythrocytes from PB MNCs. As shown in Fig. 4A, negative selection resulted in significant enrichment of CD14 monocytes, including approximately one-fifth of CD16 nonclassical monocytes. To determine if ERBB3 is coupled to PI3K/Akt signaling in human monocytes, we stimulated cells with GGF2 and measured activation of PI3K by measuring PIP3 as well as pAkt. GGF2 significantly increased cellular PIP3 (Fig. 4B) as well as pAkt (Fig. 4C), indicating the presence of functionally active ERBB signaling in human monocytes. We further analyzed pAkt in subsets of CD14hi and CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes using flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 4, D–F, GGF2 increased pAkt in both subsets of human monocytes. The effect produced by GGF2 in nonclassical monocytes was compared with insulin (Fig. 4F), a well-known inducer of PI3K signaling in human monocytes (30). The effect of GGF2 on pAkt was nearly completely inhibited by 100 nM wortmannin, an inhibitor of PI3K (4).

Fig. 4.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) mediates the effect of GGF2 on LPS-induced TNF-α production in human monocytes. Analysis of PI3K activity and Akt phosphorylation (pAkt) was performed using human PB MNCs obtained from control subjects with documented expression of ERBB3 on monocytes. A: representative dot plots showing percentages of CD14pos monocytes before (left, pre-sort) and after (middle, post-sort) enrichment of monocytes using negative selection (depletion of CD3-, CD19-, and CD56-expressing cells). Also shown is a dot plot showing percentages of CD14hiCD16neg and CD14lowCD16pos after enrichment of monocytes (right, post-sort). An enriched population of monocytes was used to determine PI3K activity and pAkt. B: phospholipids were isolated from monocytes incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 30 ng/ml GGF2 for 10 min, and the level of PIP3 was determined using ELISA. Data represent means ± SE from 3 independent isolations of monocytes (unpaired t-test). C: effect of GGF2 on expression levels of the active form of Akt kinase (pAkt, Ser437; top) and total Akt (bottom) was determined using Western blot analysis. Purified peripheral blood monocytes were stimulated for 15 min; molecular weight, Precision Plus Protein Kaleidoscope standard (Bio-Rad Laboratories). D: representative flow cytometric histograms demonstrating the level of pAkt (open histograms) in CD14hi (left) and CD14low(right) HLA-DR+ monocytes incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 100 ng/ml insulin (positive control) or GGF2 (30 ng/ml); gray-shaded histograms, isotype-matched antibody. E and F: graphical representation of data from flow cytometry analysis of pAkt in CD14hiHLA-DR+ (E) and CD14lowHLA-DR+ (F) monocytes. W, wortmannin; ns, not significant. Data represent means ± SE from 3 independent experiments performed in duplicate. P values are indicated (unpaired t-test). G: graphical representation of data from flow cytometry analysis of TNF-α production in CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes incubated in the absence (basal) or presence of 100 nM wortmannin (Wtm) alone, 10 ng/ml LPS alone (LPS), and a combination of LPS and 30 ng/ml GGF2 and wortmannin (LPS+G+W). Data represent means ± SE from 3 independent experiments. The one-way ANOVA test was significant (P ≤ 0.0001) for between-group differences; Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison posttest was used. P values between groups are shown.

We examined the effect of wortmannin on ERBB3-mediated inhibition of TNF-α expression. Wortmannin itself had no effect on basal TNF-α expression but prevented the inhibitory effect of GGF2 on LPS-induced TNF-α expression in CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes (Fig. 4G). PI3K inhibitors are known to potentiate LPS-induced TNF-α secretion (46, 50). Indeed, we also observed a greater LPS effect on TNF-α production in the presence of wortmannin. However, no difference was found in LPS-induced TNF-α between GGF2-treated and nontreated cells in the presence of wortmannin. Our data demonstrate that PI3K/Akt signaling is involved in the inhibition of LPS-induced TNF-α by GGF2 in CD14lowHLA-DR+ monocytes. GGF2 also induced PI3K activation and pAkt in CD14hiHLA-DR+. However, this was not associated with the inhibition of TNF-α production in classical monocytes, indicating functional diversity of signaling pathways triggered by LPS in subsets of classical and nonclassical monocytes (17, 53).

GGF2 downregulates expression of TNF-α in subjects with HF.

To examine whether ERBB activation occurs in circulating PB MNCs in vivo, we collected whole blood and isolated PB MNCs before and 3 h after a single dose of 0.189 mg/kg (n = 3) or 0.378 mg/kg (n = 4) GGF2 during phase I of the first in-human safety and tolerability study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01258387), as previously reported (38). These were compared with samples collected from three subjects, randomized to placebo infusion. These samples came from cohorts 4 and 5 of the 7-cohort study. Analysis was conducted blinded to treatment groups. GGF2, but not placebo, was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the expression of TNF-α mRNA 3 h after injection (Fig. 5). The level of TNF-α mRNA was slightly increased in only one subject after GGF2 injection, which may be explained by the absence of ERBB3 cell surface expression on monocytes obtained from this subject, as revealed by flow cytometric analysis. Whereas cohorts 4 and 5 of this study received two different doses of GGF2, there was no difference in percent inhibition of TNF-α expression between the two groups of subjects [43.1% (IQR: 29.4–54.4) and 33.6% (IQR: 24.3–54.2) β-actin for 0.189 and 0.378 mg/kg GGF2, respectively, P = 0.701, Mann-Whitney test].

Fig. 5.

GGF2 downregulates TNF-α mRNA expression in HF in vivo. Total RNA was isolated from PB MNCs from HF subjects taken before and 3 h after GGF2 or placebo infusion. Data are presented as before and after plot. Statistical significance was calculated using a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. P values are indicated.

DISCUSSION

The immune system contributes to amplification of inflammation after cardiac injury and propagation of chronic HF (29, 31, 39, 40, 43, 56). Elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, released by activated immune cells, are associated with poor outcomes (13, 45, 47). rNRG-1, an ERBB3 and ERBB4 receptor ligand, has being developed as a new therapeutic approach to HF. Clinical trials have demonstrated that systemically administered rhNRG improves cardiac performance (21, 38). Because immune cells were shown to express ERBB receptors (49), we used a systematic approach to analyze ERBB receptor expression simultaneously on PB MNCs in subjects with HF and in control subjects. We found that monocytes are the only fraction of PB MNCs characterized by cell surface expression of ERBB2 and ERBB3. The coexpression of ERBB2 and ERBB3 is functionally important, due to their mutually dependent coactivation. ERBB2 has no ligand-binding ability, and its involvement in NRG-1 signaling depends on heterodimerization with ERBB3. Upon binding NRGs, ERBB3 has impaired kinase activity on its own but achieves full activity in a complex with ERBB2 (28).

Human blood monocytes consist of two phenotypically and functionally different subsets: a major subset of CD14highCD16−, also called “classical” monocytes, and a small subset of CD14lowCD16+, “nonclassical” monocytes. These subsets have been characterized by differential TNF-α production in response to inflammatory stimuli (6, 12, 15). The present study shows that GGF2 inhibits LPS-induced production of TNF-α in nonclassical monocytes. This effect was dependent of cell surface expression of ERBB3 and mediated via activation of downstream PI3K/Akt signaling. In contrast, GGF2 did not inhibit LPS-induced TNF-α production in CD14highCD16− classical monocytes, regardless of ERBB3 expression or activation of PI3K/Akt signaling. We speculate that differences in responses to GGF2 between these monocyte subsets may be due to differences in signaling downstream to PI3K/Akt (32). However, this hypothesis remains to be investigated.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work demonstrating the possibility of selective inhibition of activated CD14lowCD16+ monocytes. In contrast to CD14highCD16− monocytes, CD14lowCD16+ are characterized by their increased adherence to endothelial cells, with the majority of these cells found in the marginal pool (52). Several studies have suggested that CD14low monocytes patrol blood vessels in search of virally infected or damaged endothelial cells (2, 15, 22, 58). Furthermore, in vivo studies have provided direct evidence that upon activation, Ly6Clow monocytes, the “murine counterpart” of the nonclassical human subset, produce TNF-α and mediate recruitment of neutrophils to the area of damaged endothelial cells (9). TNF-α is a powerful inducer of adhesion molecules, thus stimulating interactions between inflammatory and endothelial cells (60). Endothelial cell-specific deletion of NRG in vivo leads to increased leukocyte accumulation in injured myocardium (25), suggesting that endothelial cell-derived NRG inhibits an amplification of inflammatory reactions. Our results, demonstrating an inhibitory effect of ERBB3 on proinflammatory activation of CD14lowCD16+ monocytes, add further detail to the concept of NRG as an important modulator of inflammation. Interindividual variability in ERBB3 expression appears to relate to both baseline TNF-α expression in HF as well as the ability of rNRG to suppress LPS-inducible TNF-α expression in vitro in control subjects without HF. We speculate that NRG, acting via ERBB3 receptors to downregulate proinflammatory activation of monocytes, may contribute to prevention of inflammation and progression of HF. Given that the uncontrolled activation of monocytes can lead to severe inflammatory conditions (59), NRG/ERBB signaling in CD14lowCD16+ monocytes may represent a new therapeutic option for the treatment of chronic diseases associated with inflammation, including but not limited to HF.

GRANTS

Support for this work was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (P20-HL-101425 and U01-HL-100398 to D. B. Sawyer and K01-HL-121045-01 to C. L. Galindo), in part, by American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 15GRNT25760035 to I. Feoktistov), National Institute of General Medical Science, Progenitor Cell Analysis Core Facility, Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) in Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine (P30-GM-103465), Phase III COBRE in Vascular Biology (P30-GM-103392), and Acorda Therapeutics.

DISCLOSURES

D. B. Sawyer is an inventor on a patent for the use of NRG for the treatment of heart failure. He has received grant support from Acorda Therapeutics and has consulted over the development of recombinant NRGs for the treatment of heart failure.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.R., A.M., Q.Z., T-L.T., D.L., and C.G.L. performed experiments; S.R., A.M., C.L.G., and Q.Z. analyzed data; S.R., A.M., I.F., and D.B.S. interpreted results of experiments; S.R. prepared figures; S.R. drafted manuscript; S.R., C.L.G., D.L., I.F., and D.B.S. edited and revised manuscript; S.R., A.M., C.L.G., Q.Z., T-L.T., D.L., C.G.L., I.F., and D.B.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Michael Rock and Sandy Yoder (Vanderbilt Immunology Core Laboratory) for performing the isolation and storage of peripheral blood mononuclear cells and Jacob Boles [Maine Medical Center Research Institute (MMCRI), Summer Student II] and Larisa Ryzhova (MMCRI, Staff Scientist II) for the assistance with analysis of Akt phosphorylation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amir O, Spivak I, Lavi I, Rahat MA. Changes in the monocytic subsets CD14dimCD16+ and CD14++CD16− in chronic systolic heart failure patients. Mediators Inflamm 2012: 616384, 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/616384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonelli LR, Leoratti FM, Costa PA, Rocha BC, Diniz SQ, Tada MS, Pereira DB, Teixeira-Carvalho A, Golenbock DT, Gonçalves R, Gazzinelli RT. The CD14+CD16+ inflammatory monocyte subset displays increased mitochondrial activity and effector function during acute Plasmodium vivax malaria. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004393, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apostolakis S, Lip GY, Shantsila E. Monocytes in heart failure: relationship to a deteriorating immune overreaction or a desperate attempt for tissue repair? Cardiovasc Res 85: 649–660, 2010. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arcaro A, Wymann MP. Wortmannin is a potent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor: the role of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in neutrophil responses. Biochem J 296: 297–301, 1993. doi: 10.1042/bj2960297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barisione C, Garibaldi S, Ghigliotti G, Fabbi P, Altieri P, Casale MC, Spallarossa P, Bertero G, Balbi M, Corsiglia L, Brunelli C. CD14CD16 monocyte subset levels in heart failure patients. Dis Markers 28: 115–124, 2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/236405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belge KU, Dayyani F, Horelt A, Siedlar M, Frankenberger M, Frankenberger B, Espevik T, Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The proinflammatory CD14+CD16+DR++ monocytes are a major source of TNF. J Immunol 168: 3536–3542, 2002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonett DG, Seier E. Confidence interval for a coefficient of dispersion in nonnormal distributions. Biom J 48: 144–148, 2006. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200410148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlin LM, Stamatiades EG, Auffray C, Hanna RN, Glover L, Vizcay-Barrena G, Hedrick CC, Cook HT, Diebold S, Geissmann F. Nr4a1-dependent Ly6C(low) monocytes monitor endothelial cells and orchestrate their disposal. Cell 153: 362–375, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carraway KL III, Soltoff SP, Diamonti AJ, Cantley LC. Heregulin stimulates mitogenesis and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in mouse fibroblasts transfected with erbB2/neu and erbB3. J Biol Chem 270: 7111–7116, 1995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charalambous BM, Stephens RC, Feavers IM, Montgomery HE. Role of bacterial endotoxin in chronic heart failure: the gut of the matter. Shock 28: 15–23, 2007. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318033ebc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu YG, Shao T, Feng C, Mensah KA, Thullen M, Schwarz EM, Ritchlin CT. CD16 (FcRgammaIII) as a potential marker of osteoclast precursors in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 12: R14, 2010. doi: 10.1186/ar2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohn JN, Goldstein SO, Greenberg BH, Lorell BH, Bourge RC, Jaski BE, Gottlieb SO, McGrew F III, DeMets DL, White BG; Vesnarinone Trial Investigators . A dose-dependent increase in mortality with vesnarinone among patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med 339: 1810–1816, 1998. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812173392503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costa C, Ebi H, Martini M, Beausoleil SA, Faber AC, Jakubik CT, Huang A, Wang Y, Nishtala M, Hall B, Rikova K, Zhao J, Hirsch E, Benes CH, Engelman JA. Measurement of PIP3 levels reveals an unexpected role for p110β in early adaptive responses to p110α-specific inhibitors in luminal breast cancer. Cancer Cell 27: 97–108, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cros J, Cagnard N, Woollard K, Patey N, Zhang SY, Senechal B, Puel A, Biswas SK, Moshous D, Picard C, Jais JP, D’Cruz D, Casanova JL, Trouillet C, Geissmann F. Human CD14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity 33: 375–386, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deswal A, Petersen NJ, Feldman AM, Young JB, White BG, Mann DL. Cytokines and cytokine receptors in advanced heart failure: an analysis of the cytokine database from the Vesnarinone trial (VEST). Circulation 103: 2055–2059, 2001. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.16.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devêvre EF, Renovato-Martins M, Clément K, Sautès-Fridman C, Cremer I, Poitou C. Profiling of the three circulating monocyte subpopulations in human obesity. J Immunol 194: 3917–3923, 2015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felker GM, Pang PS, Adams KF, Cleland JG, Cotter G, Dickstein K, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Greenberg BH, Hernandez AF, Khan S, Komajda M, Konstam MA, Liu PP, Maggioni AP, Massie BM, McMurray JJ, Mehra M, Metra M, O’Connell J, O’Connor CM, Pina IL, Ponikowski P, Sabbah HN, Teerlink JR, Udelson JE, Yancy CW, Zannad F, Gheorghiade M; International AHFS Working Group . Clinical trials of pharmacological therapies in acute heart failure syndromes: lessons learned and directions forward. Circ Heart Fail 3: 314–325, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.893222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fildes JE, Shaw SM, Yonan N, Williams SG. The immune system and chronic heart failure: is the heart in control? J Am Coll Cardiol 53: 1013–1020, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frangogiannis NG. Regulation of the inflammatory response in cardiac repair. Circ Res 110: 159–173, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao R, Zhang J, Cheng L, Wu X, Dong W, Yang X, Li T, Liu X, Xu Y, Li X, Zhou M. A phase II, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, based on standard therapy, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of recombinant human neuregulin-1 in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 55: 1907–1914, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garibaldi S, Barisione C, Ghigliotti G, Spallarossa P, Barsotti A, Fabbi P, Corsiglia L, Palmieri D, Palombo D, Brunelli C. Soluble form of the endothelial adhesion molecule CD146 binds preferentially CD16+ monocytes. Mol Biol Rep 39: 6745–6752, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1499-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geisberg CA, Lenihan DJ. Neuregulin in heart failure : reverse translation from cancer cardiotoxicity to new heart failure therapy. Herz 36: 306–310, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00059-011-3472-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guha M, Mackman N. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway limits lipopolysaccharide activation of signaling pathways and expression of inflammatory mediators in human monocytic cells. J Biol Chem 277: 32124–32132, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedhli N, Dobrucki LW, Kalinowski A, Zhuang ZW, Wu X, Russell RR III, Sinusas AJ, Russell KS. Endothelial-derived neuregulin is an important mediator of ischaemia-induced angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Cardiovasc Res 93: 516–524, 2012. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedhli N, Huang Q, Kalinowski A, Palmeri M, Hu X, Russell RR, Russell KS. Endothelium-derived neuregulin protects the heart against ischemic injury. Circulation 123: 2254–2262, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.991125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hellyer NJ, Cheng K, Koland JG. ErbB3 (HER3) interaction with the p85 regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Biochem J 333: 757–763, 1998. doi: 10.1042/bj3330757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hynes NE, Lane HA. ERBB receptors and cancer: the complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer 5: 341–354, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nrc1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jankowska EA, Ponikowski P, Piepoli MF, Banasiak W, Anker SD, Poole-Wilson PA. Autonomic imbalance and immune activation in chronic heart failure—pathophysiological links. Cardiovasc Res 70: 434–445, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin SY, Kim EK, Ha JM, Lee DH, Kim JS, Kim IY, Song SH, Shin HK, Kim CD, Bae SS. Insulin regulates monocyte trans-endothelial migration through surface expression of macrophage-1 antigen. Biochim Biophys Acta 1842: 1539–1548, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaya Z, Leib C, Katus HA. Autoantibodies in heart failure and cardiac dysfunction. Circ Res 110: 145–158, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kramer PR, Winger V, Reuben J. PI3K limits TNF-alpha production in CD16-activated monocytes. Eur J Immunol 39: 561–570, 2009. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krüger S, Kunz D, Graf J, Stickel T, Merx MW, Koch KC, Janssens U, Hanrath P. Endotoxin hypersensitivity in chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol 115: 159–163, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuramochi Y, Cote GM, Guo X, Lebrasseur NK, Cui L, Liao R, Sawyer DB. Cardiac endothelial cells regulate reactive oxygen species-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through neuregulin-1beta/erbB4 signaling. J Biol Chem 279: 51141–51147, 2004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lebrasseur NK, Coté GM, Miller TA, Fielding RA, Sawyer DB. Regulation of neuregulin/ErbB signaling by contractile activity in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C1149–C1155, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00487.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemmens K, Doggen K, De Keulenaer GW. Activation of the neuregulin/ErbB system during physiological ventricular remodeling in pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H931–H942, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00385.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenihan DJ, Anderson S, Geisberg C, Caggiano A, Eisen A, Brittain E, Muldowney JAS III, Mendes L, Sawyer D. Safety and tolerability of glial growth factor 2 in patients with chronic heart failure: a phase I single dose escalation study. J Am Coll Cardiol 61: E707, 2013. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(13)60707-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lenihan DJ, Anderson SA, Lenneman CG, Brittain E, Muldowney JAS, Mendes L, Zhao PZ, Iaci J, Frohwein S, Zolty R, Eisen A, Sawyer DB, Caggiano AO. A phase I, single ascending dose study of cimaglermin alfa (neuregulin 1β3) in patients with systolic dysfunction and heart failure. JACC Basic Transl Sci 1: 576–586, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine B, Kalman J, Mayer L, Fillit HM, Packer M. Elevated circulating levels of tumor necrosis factor in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 323: 236–241, 1990. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007263230405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mann DL. The emerging role of small non-coding RNAs in the failing heart: big hopes for small molecules. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 25: 149, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s10557-011-6292-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marballi K, Quinones MP, Jimenez F, Escamilla MA, Raventós H, Soto-Bernardini MC, Ahuja SS, Walss-Bass C. In vivo and in vitro genetic evidence of involvement of neuregulin 1 in immune system dysregulation. J Mol Med (Berl) 88: 1133–1141, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0653-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchant DJ, Boyd JH, Lin DC, Granville DJ, Garmaroudi FS, McManus BM. Inflammation in myocardial diseases. Circ Res 110: 126–144, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mari D, Di Berardino F, Cugno M. Chronic heart failure and the immune system. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 23: 325–340, 2002. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:23:3:325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin M, Schifferle RE, Cuesta N, Vogel SN, Katz J, Michalek SM. Role of the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase-Akt pathway in the regulation of IL-10 and IL-12 by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 171: 717–725, 2003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nymo SH, Hulthe J, Ueland T, McMurray J, Wikstrand J, Askevold ET, Yndestad A, Gullestad L, Aukrust P. Inflammatory cytokines in chronic heart failure: interleukin-8 is associated with adverse outcome. Results from CORONA. Eur J Heart Fail 16: 68–75, 2014. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park YC, Lee CH, Kang HS, Chung HT, Kim HD. Wortmannin, a specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase, enhances LPS-induced NO production from murine peritoneal macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 240: 692–696, 1997. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rauchhaus M, Doehner W, Francis DP, Davos C, Kemp M, Liebenthal C, Niebauer J, Hooper J, Volk HD, Coats AJ, Anker SD. Plasma cytokine parameters and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 102: 3060–3067, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.25.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryzhov S, Biktasova A, Goldstein AE, Zhang Q, Biaggioni I, Dikov MM, Feoktistov I. Role of JunB in adenosine A2B receptor-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor production. Mol Pharmacol 85: 62–73, 2014. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.088567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Safa RN, Peng XY, Pentassuglia L, Lim CC, Lamparter M, Silverstein C, Walker J, Chen B, Geisberg C, Hatzopoulos AK, Sawyer DB. Neuregulin-1β regulation of embryonic endothelial progenitor cell survival. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H1311–H1319, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01104.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seow V, Lim J, Iyer A, Suen JY, Ariffin JK, Hohenhaus DM, Sweet MJ, Fairlie DP. Inflammatory responses induced by lipopolysaccharide are amplified in primary human monocytes but suppressed in macrophages by complement protein C5a. J Immunol 191: 4308–4316, 2013. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma R, von Haehling S, Rauchhaus M, Bolger AP, Genth-Zotz S, Doehner W, Oliver B, Poole-Wilson PA, Volk HD, Coats AJ, Adcock IM, Anker SD. Whole blood endotoxin responsiveness in patients with chronic heart failure: the importance of serum lipoproteins. Eur J Heart Fail 7: 479–484, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steppich B, Dayyani F, Gruber R, Lorenz R, Mack M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Selective mobilization of CD14+CD16+ monocytes by exercise. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C578–C586, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thaler B, Hohensinner PJ, Krychtiuk KA, Matzneller P, Koller L, Brekalo M, Maurer G, Huber K, Zeitlinger M, Jilma B, Wojta J, Speidl WS. Differential in vivo activation of monocyte subsets during low-grade inflammation through experimental endotoxemia in humans. Sci Rep 6: 30162, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep30162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Bruggen T, Nijenhuis S, van Raaij E, Verhoef J, van Asbeck BS. Lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha production by human monocytes involves the raf-1/MEK1-MEK2/ERK1-ERK2 pathway. Infect Immun 67: 3824–3829, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vonhof S, Brost B, Stille-Siegener M, Grumbach IM, Kreuzer H, Figulla HR. Monocyte activation in congestive heart failure due to coronary artery disease and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 63: 237–244, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5273(97)00332-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Werdan K. The activated immune system in congestive heart failure—from dropsy to the cytokine paradigm. J Intern Med 243: 87–92, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wrigley BJ, Lip GY, Shantsila E. The role of monocytes and inflammation in the pathophysiology of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 13: 1161–1171, 2011. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wrigley BJ, Shantsila E, Tapp LD, Lip GY. CD14++CD16+ monocytes in patients with acute ischaemic heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest 43: 121–130, 2013. doi: 10.1111/eci.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang J, Zhang L, Yu C, Yang XF, Wang H. Monocyte and macrophage differentiation: circulation inflammatory monocyte as biomarker for inflammatory diseases. Biomark Res 2: 1, 2014. doi: 10.1186/2050-7771-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang F, Yu W, Hargrove JL, Greenspan P, Dean RG, Taylor EW, Hartle DK. Inhibition of TNF-alpha induced ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin expression by selenium. Atherosclerosis 161: 381–386, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]