Abstract

Cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs) are potent lipid mediators widely known for their actions in asthma and in allergic rhinitis. Accumulating data highlights their involvement in a broader range of inflammation-associated diseases such as cancer, atopic dermatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and cardiovascular diseases. The reported elevated levels of CysLTs in acute and chronic brain lesions, the association between the genetic polymorphisms in the LTs biosynthesis pathways and the risk of cerebral pathological events, and the evidence from animal models link also CysLTs and brain diseases. This review will give an overview of how far research has gone into the evaluation of the role of CysLTs in the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorders (ischemia, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, multiple sclerosis/experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, and epilepsy) in order to understand the underlying mechanism by which they might be central in the disease progression.

1. Introduction

Growing evidence indicates that cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs), a group of highly active lipid mediators, synthetized from arachidonic acid via the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) pathway, play a pivotal role in both physiological and pathological conditions.

Cysteinyl leukotrienes—LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4—exhibit several biological activities in nanomolar concentrations through at least two specific G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) subtypes named CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2 which show 38% homology [1]. These endogenous mediators show different affinity toward their receptors [2]: LTD4 indeed is the most potent ligand for CysLTR-1 followed by LTC4 and LTE4 [3], whereas LTC4 and LTD4 equally bound CysLTR-2, while LTE4 shows only low affinity to this receptor [1]. However, the biological effects of CysLTs do not seem to be mediated only by CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2. Indeed, these receptors are phylogenetically related to purinergic P2Y class of GPCRs [4] and evidence reported in the literature suggests the existence of additional receptors responding to CysLTs [5], such as GPR17 [6], GPR99 [7], PPARγ [8], P2Y6 [9], and P2Y12 [10].

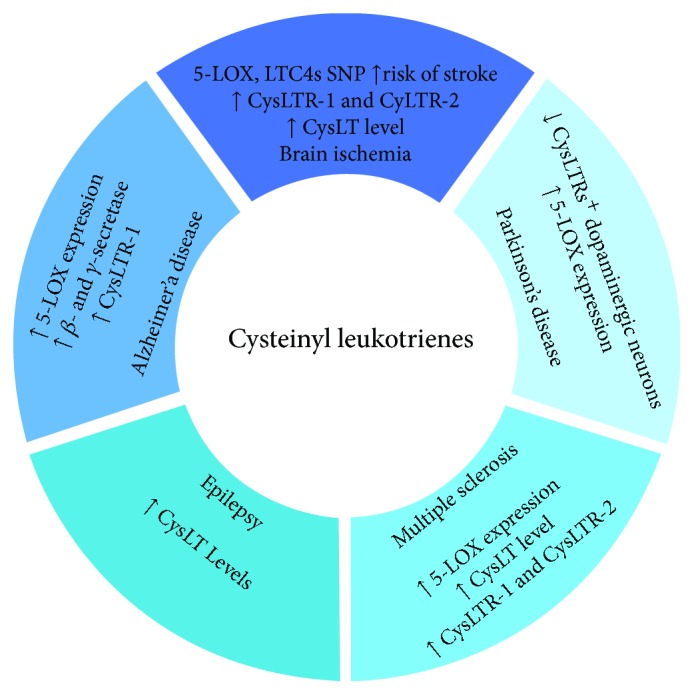

In the last decade, several lines of evidence link CysLTs, central in the pathophysiology of respiratory diseases, such as asthma and allergic diseases [11–14], to other inflammatory conditions including cancer and cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, skin, and immune disorders [15, 16]. Among them, a role of CysLTs and their receptors has been emerging in central nervous system (CNS) diseases, such as cerebral ischemia [15, 17, 18], intracerebral hemorrhage [19], brain trauma [20, 21], epilepsy [22], multiple sclerosis [23], Alzheimer's disease [24], and brain tumor [25]. This review will summarize the state of present research about the involvement of CysLT pathway (Figure 1) and the effects of its pharmacological modulation (Table 1) on CNS disorders.

Figure 1.

CysLTs in neurodegenerative diseases. The circle shows the changes of the CysLT pathway components grouped for the different neurodegenerative diseases and observed in human patients and in in vitro/in vivo models.

Table 1.

The neuroprotective effects of drugs acting on CysLT pathway in CNS disorders.

| Brain ischemia | ||||

| Model | Drug class | Molecule | Effect | Reference |

| Transient MCAO in gerbils | 5-LOX inhibitor | AA-861 | ↓ neuronal death | [70, 71] |

| Transient MCAO in rats |

5-LOX inhibitor | Minocycline | ↓ ischemic injuries, IgG exudation, and neutrophils and macrophage/microglia accumulation |

[83] |

| Permanent MCAO in rats | FLAP inhibitor | MK-886 | ↓ acute infarct size | [72] |

| Permanent MCAO in rats | 5-LOX inhibitor | Zileuton | ↓ edema, infarct volume, neurological deficits, MPO activity, lipid peroxidation levels, inflammatory reaction, and apoptosis |

[73–75] |

| OGD in rats astrocytes | FLAP inhibitor | MK-886 | ↓ astrocyte proliferation and death | [29] |

| OGD in rats astrocytes | 5-LOX inhibitor | Zileuton | ↓ astrocyte proliferation and death | [29] |

| OGD in rats astrocytes | 5-LOX inhibitor | Caffeic acid | ↓ astrocyte proliferation and death | [29] |

| Transient MCAO in rats and mice | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Pranlukast | ↓ neurological deficits, infarct volume, BBB disruption, neuron loss in the ischemic core, astrocyte proliferation in the boundary zone, and ischemia-induced glial scar formation ↑ motor-sensory recovery |

[15, 65, 68, 78] |

| Permanent MCAO in rats and mice | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Pranlukast | ↓ neurological deficits, infarct volume, edema, BBB disruption, neuron degeneration, and MPO-positive neutrophil accumulation |

[49] |

| Transient MCAO in rats and mice | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Montelukast | ↓ infarct size, brain atrophy, neuron loss, behavioural dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, release of glutamate, apoptosis, and lactate dehydrogenase activity |

[80, 81] |

| Permanent MCAO in rats and mice | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Montelukast | ↓ infarct volume, brain edema, neuron density, and neurological deficits |

[6, 79] |

| Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Montelukast | ↓ ischemic cerebral and nerve damage ↑ behavior recovery of chronic ischemic brain damage |

[82] |

| OGD in rats astrocytes | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Montelukast | ↓ astrocyte proliferation | [29] |

| Transient MCAO in rats | CysLTR-2 antagonist | HAMI 3379 | ↓ neurological deficits, lesion volume, edema, and neuronal degeneration and loss |

[50, 69] |

| OGD in PC12 cell | CysLTR-1/CysLTR-2 dual antagonist | Bay-u9773 | ↓ apoptosis | [62] |

| OGD in rats astrocytes | CysLTR-2 antagonist | Bay CysLT2 | ↓ astrocyte death | [29] |

| OGD in rats astrocytes | CysLTR-1/CysLTR-2 dual antagonist | Bay-u9773 | ↓ astrocyte proliferation and death | [29] |

| Alzheimer's disease | ||||

| Model | Drug class | Molecule | Effect | Reference |

| Tg2576 mice | FLAP inhibitor | MK-591 | ↓ Aβ peptide (Aβ) deposition, γ-secretase complex, neuroinflammation, and microglia and astrocytes activation |

[120] |

| N2A-APPswe cells | FLAP inhibitor | MK-591 | ↓ Aβ peptide (Aβ) deposition, γ-secretase complex | [120] |

| Tg2576 mice | 5-LOX inhibitor | Zileuton | ↓ Aβ peptide (Aβ) deposition, γ-secretase complex | [121] |

| N2A-APPswe cells | 5-LOX inhibitor | Zileuton | ↓ Aβ peptide (Aβ) deposition, γ-secretase complex | [121] |

| 3xTg mice | FLAP inhibitor | MK-591 | ↓ Aβ peptide (Aβ) deposition, behavioural deficits, neuroinflammation, and microglia and astrocytes activation |

[127] |

| Tg2576 mice | FLAP inhibitor | MK-591 | ↓ brain tau phosphorylation | [128] |

| Rat hippocampal neurons treated with Aβ1–42 | 5-LOX inhibitors | NDGA, AA-861 |

Prevention of neuronal injury and accumulation of ROS | [129] |

| Microinfusion of Aβ1–42 | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Montelukast | Improvement of memory impairment via inhibiting neuroinflammation and apoptosis |

[125] |

| Mouse cortical neurons treated with Aβ1–42 | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Pranlukast | Reverse Aβ1–42-induced cognitive deficit and AD features | [130] |

| Microinfusion of Aβ1–42 | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Pranlukast | ↓ apoptosis | [130] |

| Mouse neurons treated with Aβ1–42 | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Montelukast | ↓ proinflammatory factors and the apoptosis-related proteins | [131] |

| Microinfusion of Aβ1–42 | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Pranlukast | Improvement of memory impairment via inhibiting neuroinflammation and apoptosis |

[132] |

| Parkinson's disease | ||||

| Model | Drug class | Molecule | Effect | Reference |

| MPTP-treated mice | FLAP inhibitor | MK-866 | ↓ toxicity of dopaminergic neurons; ↑ [3H]-dopamine up-take | [137] |

| MPP+ treated SH-SY5Y cell line | FLAP inhibitor | MK-866 | ↓ toxicity of dopaminergic neurons ↑ [3H]-dopamine uptake and cell survival |

[137] |

| LPS-treated mice | 5-LOX/COX inhibitor | Phenidone | ↓ oxidative stress, microglial activation, and demise of the nigral dopaminergic neurons |

[139] |

| LPS-treated mice | 5-LOX inhibitor | Caffeic acid | ↓ dopaminergic neurodegeneration and microglia activation | [139] |

| Multiple sclerosis/experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis | ||||

| Model | Drug class | Molecule | Effect | Reference |

| PLP-induced EAE mice | 5-LOX inhibitor | Zileuton | Delay of the onset and reduction of cumulative EAE severity | [152] |

| MOG-induced EAE mice | 5-LOX inhibitor | Zileuton | Delay of the onset and reduction of cumulative EAE severity | [153] |

| Cuprizone-treated mice | FLAP inhibitor | MK-886 | ↓ axonal damage, motor deficits, and neuroinflammation | [149] |

| MOG-induced EAE mice | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Zafirlukast | ↓ CNS infiltration of inflammatory cells and symptoms of EAE | [148] |

| MOG-induced EAE mice | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Montelukast | ↓ demyelination, leukocyte infiltration, secretion of IL-17, permeability of the BBB, chemotaxis of T cells, and severity of EAE |

[148] |

| MOG-induced EAE mice | Dual inhibitor of LOX/COX pathway | Flavocoxid | ↓ CNS infiltration of inflammatory cells, infiltration and differentiation of Th1+ and Th17+ cells, and symptoms of EAE | [154] |

| Epilepsy | ||||

| Model | Drug class | Molecule | Effect | Reference |

| Kainic acid rat model | 5-LOX/COX inhibitor | Phenidone | ↓ seizure activity, neurotoxic signs, neuronal loss, lipid peroxidation, and protein oxidation |

[160, 166] |

| Kainic acid rat model | 5-LOX/COX inhibitor | BW755C | ↓ severity of seizures and neurotoxicity | [167] |

| Pilocarpine rat model | 5-LOX inhibitor | Zileuton | ↓ spike–wave discharges | [168] |

| PTZ-mice model | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Montelukast | ↓ recurrent seizures, frequency of daily seizures, BBB disruption, leukocyte migration, and mean amplitude of EEG recordings during seizures. ↑ increased the latency to generalized seizures |

[162, 163] |

| PTZ-mice model |

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase inhibitor |

1,2,3,4, Tetrahydroisoquinoline | ↓ kindled seizures and frequency of daily seizures | [162] |

| Pilocarpine mice model | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Montelukast | ↓ kindled seizures and frequency of daily seizures |

[162] |

| Pilocarpine mice model |

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase inhibitor |

1,2,3,4, Tetrahydroisoquinoline | ↓ recurrent seizures and frequency of daily seizures | [162] |

| Electrically kindled seizure mice |

CysLTR-1 antagonist | Montelukast | ↓ recurrent seizures and frequency of daily seizures | [162] |

| Electrically kindled seizure mice |

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase inhibitor |

1,2,3,4, Tetrahydroisoquinoline | ↓ recurrent seizures and frequency of daily seizures | [162] |

| PTZ-mice model | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Pranlukast | ↓ seizure susceptibility and mean amplitude of ictal EEG recordings |

[163] |

| PTZ-mice model | CysLTR-1/CysLTR-2 dual antagonist | Bay- u9773 | ↑ increased the latency to generalized seizures ↓ mean amplitude of EEG recordings during seizures |

[163] |

| Patients with intractable partial seizures | CysLTR-1 antagonist | Pranlukast | ↓ seizure frequencies, leakage of proinflammatory cytokines into CNS, and extravasation of leucocytes, normalizing serum MMP-9 |

[22] |

2. Cerebral Localization of CysLT Receptors

In healthy brain, the expression of the CysLTRs is weak, but it was reported to increase during several pathological conditions [15, 17, 20]. CysLTR-1 [26], whose expression is normally lower than the CysLTR-2 one [1, 3], is localized in microvascular endothelial cells [21], in glial cells, and in several types of neuronal cells [15, 27, 28].

In human brain, the CysLTR-2 is expressed in many regions, such as hypothalamus, thalamus, putamen, pituitary, and medulla [1] by vascular smooth muscle cells [20] and by astrocytes [18]. After brain trauma and in brain tumors, it was also observed in neurons and in glial-appearing cells [20].

Glial cells, namely astrocytes and microglia, are key players in inflammation typically associated with neurodegenerative diseases, and their functions are regulated in a CysLTR subtype dependent manner [18, 28, 29]. Through CysLTRs localized on glial cells, CysLTs may mediate not only crucial reparative responses in the acute phase [30] but also detrimental effects in the chronic phase [31] of brain damage. Moderately activated microglial cells play a neuroprotective role due to their ability to remove dead cells, to release trophic factors, and to contribute to angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and axonal remodelling [32, 33], promoting reorganization of neuronal circuits and improving neurological recovery [34]. However, when overactivated, microglia show important adverse effects by releasing detrimental factors [35, 36] such as cytokines and nitric oxide (NO) [37] and by activating inflammation-related kinases and transcription factors [38]. Similarly, astrocytes are known to exert a protective function during brain injury [39, 40], but astrogliosis may contribute to neuronal injury [41–44].

Data indicate that in microglia, both CysLTs and CysLTRs participate in the inflammatory response [45, 46]; nevertheless, the impact of CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2 in the process is controversial. A number of in vitro evidence indicate a relevant role of CysLTR-1 in microglial activation. It was reported that rotenone—used in generating animal models of Parkinson's disease (PD)—increased CysLTR-1 expression in mouse microglial BV2 cell line [47, 48] and that treatment with the CysLTR-1 antagonist montelukast prevented phagocytosis and cytokine release [48]. Moreover, the activation of mouse microglial BV2 cells seems to be greatly mediated by CysLTR-1 than CysLTR-2 [28]. On the other hand, another study showed that, in primarily cultured microglia, the CysLTR-2 resulted the main regulator of microglia activation. Indeed, the CysLTR-2 antagonist HAMI 3379 inhibited phagocytosis and cytokine release induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R) and by LTD4, whereas montelukast was effective only against OGD/R [46].

These conflicting results suggest that the responses mediated by CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2 may change across experimental conditions; nevertheless, the role of CysLTR-2 in the regulation of microglial activation and phagocytosis is supported by in vivo evidences. Indeed, the CysLTR-1 antagonist pranlukast did not reduce the accumulation of microglia in the ischemic cerebral cortex [49], while HAMI 3379 significantly attenuated the number of microglia in the ischemic core and in the boundary zone [50].

Unlike in microglia, the function of each CysLTR subtype in astrocytes is already clear. A number of evidence support the major role of CysLTR-1 in regulating astrocyte activation, suggesting its involvement in astrocytosis and in glial scar formation. In vitro, astrocyte proliferation, induced by low concentrations of LTD4 or by mild OGD, is indeed mediated by CysLTR-1, but not by CysLTR-2 [29]. The CysLTR-1 also participates in astrocyte migration induced by transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and LTD4 [51]. In fact, this event was attenuated by administration of the CysLTR-1 antagonist montelukast, but not by the CysLTR-2 specific antagonist Bay CysLT2 [51].

2.1. Brain Ischemia

A strong indication for the involvement of the leukotriene-synthesizing pathway in the occurrence and evolution of ischemic brain diseases comes from genetic studies. In humans, a genetic variant of the gene ALOX5AP, encoding 5-lipoxygenase activating protein (FLAP), is associated with two times greater risk of stroke by increasing leukotriene production and inflammation [52–56]. The −444 A/C polymorphism on the LTC4 synthase gene also predicts an increased risk for ischemic cerebrovascular disease [57, 58]; conversely, the −1072 G/A polymorphism of the same gene results in decreased risk of ischemic cerebrovascular disease [57]. Nevertheless, to date, the meaning of these polymorphisms in the brain ischemia has not been fully understood; thus, a comprehensive analysis of these gene polymorphisms is required.

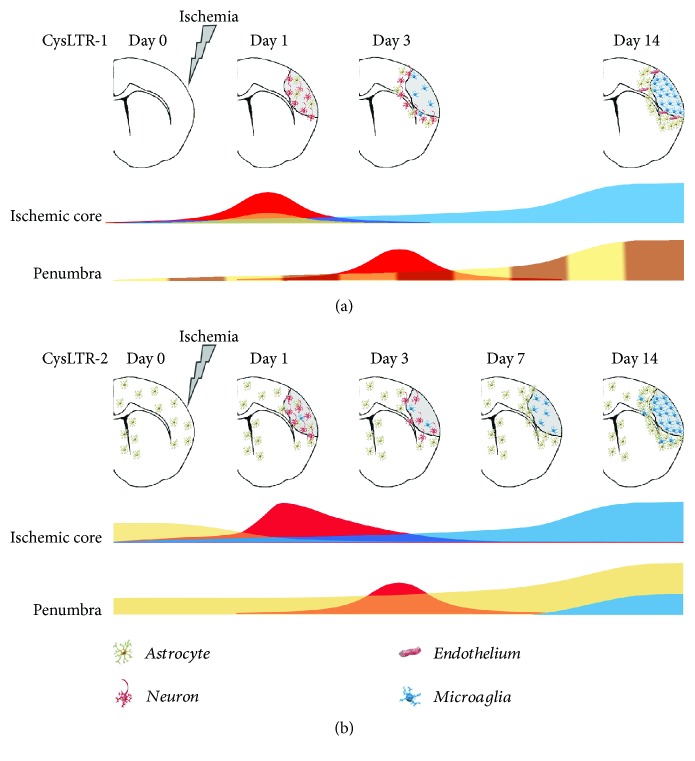

Data from in vivo and in vitro studies show that the production of CysLTs increased in the brain of rodents that underwent a cerebral ischemic insult [38] and in primary culture of neurons [59] and astrocytes [29] subjected to OGD. In rat that underwent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), the brain levels of CysLTs reached the peak within 3 hours and remained high for at least 24 hours [38]. Consequently, also the expression of CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2 was upregulated in injured neurons during the acute phase (about 24 hours) and in activated microglia and proliferating astrocytes [15, 17, 18, 60, 61] during the late phases (3–28 days) (see Figure 2). Taken together, these findings suggest that CysLTs could mediate the acute ischemic neuronal injury and the subsequent secondary injury mainly by promoting microgliosis and astrocytosis.

Figure 2.

Spatio-temporal expression of the CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors after focal cerebral ischemia in rodents. (a) In the control brain, CysLT1 receptor is weakly expressed (time 0) [15, 61]. Following middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo), its expression, at the ischemic core level, is biphasic: at day 1 postischemia, the receptor is mainly expressed in neurons (red wave) [15, 60, 61] and, to a lesser extent, in astrocytes (orange) [15]; between 7 and 14 days postischemia, it increases in microglia (blue) [15]. In the boundary zone, that is, the “penumbra,” the receptor's expression is mainly expressed in neurons (red wave) at 3 days [60] and then it increases over time in most hypertrophic astrocytes (yellow) [15] and microvascular endothelial cells (brown) [15], reaching a peak after 14 days. (b) In the healthy brain, the CysLT2 receptor is primarily expressed in GFAP+ astrocytes around the lateral ventricles and in the cortex [18]. In the ischemic core, one day postischemia, the expression of CysLT2 receptor shows a rapid and transient peak in neurons (red) [18, 60] and then gradually disappeared over 3 days. In the hypertrophic microglia (blue), it slowly increases over time and reaches a peak after 14 days [18]. In the penumbra (boundary zone), following its induction at day 0, the receptor's expression is mainly expressed in neurons (red wave) at 3 days [60] and then it increases over time in astrocytes [18]. After one week, its expression also increases in the microglia [18].

Although the role of CysLTs in brain ischemia is supported by several evidences, the mechanisms through they mediate neuronal injury are not fully clarified. Indeed, in vitro culture of neuron-like PC12 cells transfected with CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2 showed distinct sensitivities to ischemic injury, which resulted prominent in CysLTR-2-transfected cells [62], but neither CysLTR-1 nor CysLTR-2 were able to directly induce neuronal injury [46, 63]. Moreover, OGD/R-induced ischemic injury was not attenuated by the selective CysLTR-2 antagonist HAMI 3379 and by CysLTRs RNA interference in primary neurons [46]. Conflicting results were obtained by using the CysLTR-1 antagonist montelukast: this drug had no effect on neuronal viability [63] and an only moderate effect on the neuronal morphologic changes after OGD [64], while in another study improved viability in OGD/R neurons [46].

Overall, these data suggest that the direct effect of CysLTs on neurons causes only a mild type of injury; nevertheless, CysLTs could indirectly mediate a more severe neuronal injury in the presence of complex intercellular interactions. Indeed, in neuron-microglial cocultures, LTD4 was shown to induce neuronal injury [46]. Conditioned medium from microglia pretreated with OGD/R and LTD4 also induced neuronal injury that was inhibited by HAMI 3379 and CysLTR-2 short hairpin RNA (shRNA), more potently than montelukast. These findings demonstrated the main role of microglial CysLTR-2 in the induction of neuronal death compared to CysLTR-1 [46].

On the contrary, the role of CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2 in astrocyte-mediated neuronal injury is still unclear. In vitro, CysLTR-1 mediates astrocyte proliferation after mild ischemia, whereas CysLTR-2 mediates astrocyte death after more severe ischemia [29]. However, in neuron-astrocyte cocultures, subjected to OGD/R and LTD4 exposure, CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2 antagonists were unable to completely prevent astrocyte-mediated neuronal necrosis [46]. Astrocyte reactivity seems instead to be mainly mediated by CysLTR-1 rather than CysLTR-2. Indeed, CysLTR-1 was involved in glial scar formation during the chronic phase after focal cerebral ischemia [15, 65], and CysLTR-1 antagonist, but not CysLTR-2, was able to reduce the astrocyte response in the subacute phase after brain ischemia [50].

Together with microglia and astrocytes, also endothelial cells seem to contribute in CysLTR-mediated brain injury. The CysLTR-1 is highly expressed in microvascular endothelia at the ischemic boundary zone in rat [15] and in brain tissue after trauma in human [21]. Furthermore, CysLTs induced the disruption of blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the subsequent development of cerebral edema, whose progression was attenuated by CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2 antagonists [66–69]. These data suggest that CysLTR antagonists may be critical in modulating the function of cerebral microvascular endothelia and in preserving the integrity of BBB against cerebral insults.

Overall, these findings lend support to the hypothesis that a pharmacological modulation of CysLT pathway can open new terrain for therapeutic approaches targeted at attenuating local inflammation in order to modulate its impact in cerebral ischemia.

2.1.1. Inhibitors of FLAP/5-LOX

The first in vivo experimental evidence of neuroprotection through postischemic modulation of LT levels was obtained by using AA-861, a selective inhibitor of 5-LOX, in a model of transient ischemia in gerbils [70, 71]. This effect was confirmed in a model of permanent MCAO by the use of MK-886 and zileuton, selective inhibitors of FLAP and 5-LOX, respectively. MK-886 decreased the acute infarct size [72], whereas zileuton attenuated neurological dysfunction and cerebral infarction, probably inhibiting inflammatory reaction, neuronal apoptosis, and BBB disruption [73–75]. Nevertheless, despite these promising results, the association between LTs and brain ischemia is not fully demonstrated. In fact, conflicting results were obtained by using models of FLAP or 5-LOX knockout mice since one study reported an improvement of stroke damage in FLAP knockout mice [76] whereas another one showed no difference in the infarct size between 5-LOX knockout and wild-type MCAO mice [77].

2.1.2. CysLTR-1 Antagonists

Despite the evidence that CysLTR-2 is the main CysLTR subtype in the normal brain, the lack of selective CysLTR-2 antagonists limited, for long time, the clear understanding of the role of CysLTR-2 in cerebral injury. Hence, the first line of data, from experiments carried out with CysLTR antagonists, were limited to CysLTR-1. Pranlukast inhibited acute, subacute, and chronic ischemic injury in the brains of mice and rats after focal cerebral ischemia [15, 49, 65, 78]. Moreover, the postischemic treatment with pranlukast exerted a long-term protective effect in MCAO mice, attenuating the lesion volume, increasing the neuron density, inhibiting the ischemia-induced glial scar formation, and finally improving the neurological deficits and the motor-sensory recovery [65]. Montelukast attenuated infarct volume, brain atrophy, neuron loss, and behavioural dysfunction after focal cerebral ischemia in both mice and rats [6, 79, 80]. It also exerted prophylactic effects in global cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury, decreasing infarct size, oxidative stress, inflammation, release of glutamate, apoptosis, and lactate dehydrogenase activity [81]. In neonatal hypoxic-ischemic rats, montelukast showed neuroprotective effects, likely inhibiting apoptosis through the increase of TERT, the catalytic center of the telomerase complex, and Bcl-2 [82].

In summary, two possible mechanisms could be responsible in mediating the effect of CysLTR-1 antagonists on cerebral ischemia: (i) the reduction of BBB disruption and inflammation in the acute/subacute phases [15, 68, 83] and (ii) the attenuation of astrocyte proliferation and related glial scar formation in the chronic phase [29, 65].

2.1.3. CysLTR-2 Antagonists

Recently, Bay CysLT2 and HAMI 3379 have been reported to selectively antagonize CysLTR-2 [84, 85]. The intracerebral ventricular (i.c.v.) injection of HAMI 3379 showed to protect against acute brain injury in MCAO rats. This treatment attenuated neurological deficits and reduced lesion volume, edema, and neuronal degeneration [69]. HAMI 3379 was also effective when intraperitoneally administered within 1 hour after ischemia in MCAO rats [50]. In the acute phase, HAMI 3379 attenuated neuronal loss, improved neurological score, and reduced cytokine levels in serum and cerebrospinal fluid, and in the late phase, it strongly decreased the microglia/macrophage-associated postischemic inflammation, without affecting astrogliosis. The effect of the CysLTR-2 antagonists on acute ischemic brain injury could be explained by at least four possible mechanisms: (i) a direct protective action on neurons [62]; (ii) protection to astrocytes, since it was reported that in severe ischemic injury, the activated CysLTR-2 could induce astrocyte death [29]; (iii) prevention of the development of cytotoxic edema [69], effect that in astrocytes is mediated by upregulating the water channel protein AQP4, which is induced by LTD4 [86] and by ischemia-like injury [87]; and (iv) attenuation of microglial activation [50]. Potential interactions between CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2 need also to be considered. Indeed, it was reported that CysLTR-2 could limit the formation of CysLTR-1 homodimers and control its cellular surface expression [88, 89].

2.1.4. The CysLTR-Independent Effects

Despite the evidence of a direct involvement of CysLTRs in brain ischemia, we cannot rule out that the neuroprotective effects could be partially ascribed to CysLTR-independent mechanisms. Indeed, it is reported how part of the effects of CysLTs are mediated by GPR17. This receptor is phylogenetically related to CysLTRs [6, 90, 91], activated by endogenous cysteinyl leukotrienes (LTD4 and LTC4) [6, 92] and inhibited by the CysLTR-1 antagonist montelukast [6, 90]. The GPR17 colocalizes and dimerizes with CysLTR-1 and negatively regulates CysLTR-1-mediated effects [93, 94]. It was also upregulated in damaged tissues [6], and the knockout of GPR17 reduced neuronal injury after ischemia [90, 95]. Moreover, in differentiated PC12 cells, the knockdown of GPR17 abolished LTD4-induced effect on cell viability [96].

Restricting to montelukast, its neuroprotective CysLTR-1-independent effects could be also due to its ability to inhibit phosphodiesterases (PDEs) [97]. Indeed, the decreased activity of PDEs may be beneficial to ischemic neuronal injury, since the resultant accumulation of cAMP protects neurons from ischemic brain injury [98, 99] and inhibitors of PDEs have protective effects on neurons [100, 101]. In addition, montelukast was shown to inhibit P2Y receptors [9, 102, 103] and oxidative stress [104–106], which is the major cause of the ischemic injury [107–109]. Taken together, these data add new evidences for the neuroprotective effects of CysLTR-1 antagonists and highlight the need for further studies that will define the possibility to use CysLTR-1 antagonists for treatment of stroke patients. Up to now, there is only a recent cohort study that showed a reduced risk for stroke associated with montelukast use in patients with a prior stroke [110].

2.2. Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common aging-associated neurodegenerative condition resulting in progressive loss of memory and cognition and affecting worldwide over 35 million of individuals [111]. It is pathologically characterized by extracellular deposit of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) of tau protein [112, 113]. Altered inflammatory reactions and dysregulation of inflammatory cytokines as well as immune cell (i.e., microglia and astrocytes) activation are also strongly associated with AD pathology and cognitive dysfunction [114, 115].

Postmortem studies have shown that 5-LOX expression is upregulated in human brain of AD patients [116, 117]. Experiments on animal models have provided evidence on the relevant role of 5-LOX in the development of AD. In detail, the overexpression of this enzyme resulted in a worsening of amyloidosis in Tg2576 mice [118] and in an exacerbation of memory deficits, amyloid plaques, and tau tangles in triple transgenic mice (3xTg-AD) [119]. Of note, these 5-LOX-induced effects seem to be mediated by an increase of γ-secretase complex [119]. The direct involvement of 5-LOX in the γ-secretase pathway is confirmed by findings of both genetic and pharmacological inhibition of 5-LOX that reduced the activity of γ-secretase [117, 120, 121]. The increase of γ- and β-secretase occurs also in the presence of leukotriene metabolites of 5-LOX, such as 5-HPETE, LTC4, and LTD4 [117, 122]. Furthermore, in vivo and in vitro studies showed that LTD4-induced upregulation of CysLTR-1 is correlated with increased Aβ and amyloid precursor protein (APP) and with cognitive dysfunctions in mice [122–124]. In parallel, the microinfusion of Aβ1–42, a more neurotoxic Aβ species, resulted in significant increase in CysLT1-R expression in the hippocampus and cortex [125].

Genetic ablation of 5-LOX clearly reduced Aβ brain deposition in Tg2576 mice and in dexamethasone-induced Aβ mice [117, 126], while pharmacological studies using specific FLAP and 5-LOX inhibitors, MK-591 and zileuton, supported the genetic knockout findings showing in vivo ameliorative effect on AD phenotypes [120, 121, 127, 128].

The inhibition of 5-LOX also exerts beneficial effects on AD pathology-induced oxidative and inflammatory insult. In cultured rat hippocampal neurons, the pharmacological 5-LOX pathway inhibition resulted in reduced Aβ-induced reactive oxygen species generation [129]. Tg2576 mice receiving MK-591 showed a reduction in brain levels of IL-1β and in the immunoreactivity for CD45, a marker of microgliosis, and GFAP, a marker of astrogliosis [120].

Data indicate that pathological AD symptoms are attenuated through administration of selective CysLTR-1 antagonists such as pranlukast and montelukast. In primary culture of mouse neurons, Aβ1–42 markedly increased CysLTR-1 expression, which was associated with cytotoxicity, inflammatory, and apoptotic responses. Incubation with pranlukast and montelukast reversed the upregulation of Aβ1–42-induced CysLTR-1 and NF-kB p65 and activated caspase-3 expression and the downregulation of Bcl-2 [130,131]. In bilateral i.c.v. Aβ1–42-injected mice, pranlukast and montelukast reversed the Aβ1–42-induced cognitive deficits associated to inflammatory and apoptotic responses, as evidenced by decreased NF-kB p65, TNF-α, IL-1β, and caspase-3 in the hippocampus and cortex [125, 132]. Moreover, in other studies, montelukast restores learning and memory function in old rats, in which cognition is compromised and the hippocampus concentrations of 5-LOX transcripts and of leukotrienes were increased [27, 133]. Although the inhibition of CysLTR-1 could explain the maintained BBB integrity and the reduced age-associated neuroinflammation, in particular microglial reactivity, the authors suggest that montelukast promotes hippocampal neurogenesis, in particular progenitor cell proliferation, most likely through blocking GPR17 [27].

2.3. Parkinson's Disease

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disease, characterized by the depletion of striatal dopamine due to degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of the brain and manifested by the movement disorders in elderly populations. Brain inflammation and oxidative stress were reported to play important roles in the pathogenesis of PD [134–136].

Recent evidences suggest an involvement of 5-LOX in nigrostriatal dopaminergic injury. Indeed, 5-LOX upregulation was shown in MPTP-induced animal model of PD [137] and the overactivation of the 5-LOX pathway may lead to neurodegeneration by lipid peroxidation [138]. On the contrary, the inhibition of 5-LOX attenuates LPS-induced oxidative stress and dopaminergic neurodegeneration [139]. Furthermore, MK-886 treatment antagonized the MPP+-induced toxicity of dopaminergic neurons in SH-SY5Y cell line, a common cellular model for PD, and in midbrain neuron-glia cocultures [137]. Of note, LTB4, but not LTD4 or 5-HETE, enhanced the MPP+-induced cytotoxicity in the rat midbrain culture. MK-866 protects also neurons against MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in mice [137].

A recent study reported that CysLTR-1, CysLTR-2, and GPR17 are localized in dopaminergic neurons of healthy mouse brain [140]. In MPTP-treated mice, the number of CysLTR-1+, CysLTR-2+, and GPR17+ dopaminergic neurons was significantly reduced, suggesting an involvement of these receptors in this animal model of PD.

2.4. Multiple Sclerosis/Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory neurological disease of the CNS, characterized by recurrent and progressive autoimmunity-mediated demyelination, and resulting in severe infiltration of CD4+ T cells, development of sclerosis, oligodendrocyte damage, and, ultimately, axonal loss [141, 142]. Brain atrophy, one of the major features of the disease, occurs in the advanced stage of the disease [143].

The role of arachidonic acid cascade in the demyelination of the CNS was suggested by studies utilizing animal models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) [144, 145]. Microarray analysis studies indicated that the mRNA of 5-LOX is upregulated in brain lesions of patients with primary progressive and with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) [146] and in the peripheral blood cells of patients with RRMS during the relapse and the remission phases [147]. These results are corroborated by data obtained with immunohistochemistry analysis showing the presence, in the active and chronic inactive inflammatory lesions, of macrophages strongly positive for 5-LOX staining [146]. Gene and protein expressions of 5-LOX are also increased in CNS of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) [146, 148] and cuprizone-treated mice [149], the widely used animal models utilized to mimic demyelination and MS.

Notably, the concentration of 5-LOX-derived LTB4, but not of CysLTs (LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4), was significantly increased in CSF of patients with clinically active MS [150]. Contrary, previous studies reported higher levels of LTC4 in the CSF of MS patients likely due to the less accurate analytical techniques utilized [150, 151]. In EAE mice, the CysLT levels in both serum and CSF were significantly increased after disease onset, whereas did not change significantly in the brain and spinal cord, although the trends of increase could be observed [148]. Moreover, LTD4 showed a dose-dependent chemotactic activity on splenocytes, in particular those of CD4+ cells, from EAE mice [148].

The CysLTR-1 and CysLTR-2 expression was found to be upregulated in the brain after disease onset in EAE mice [148]. CysLTR-1 started to increase from the onset of the disease and kept increasing throughout the whole process also in spinal cord.

There are several evidences that 5-LOX pathway blockade could ameliorate the pathological development of MS. In EAE mice, the blockade of the cytosolic phospholipase A2α and of its downstream enzyme 5-LOX was found to ameliorate the disease pathogenesis during the effector phase of EAE [152] and to delay the onset and reduce cumulative severity of the pathology [153]. Although MK-886 did not attenuate demyelination in cuprizone-treated mice, the pharmacological inhibition of 5-LOX improved axonal damage and motor deficits related to MS pathology [149].

CysLTR-1 antagonists montelukast and zafirlukast were shown to ameliorate clinical symptoms in EAE mice [148]. In detail, montelukast reduced the demyelination and leukocyte infiltration in the spinal cord sections, the secretion of IL-17 from myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific T cells, the permeability of the BBB, and the chemotaxis of T cells. Interestingly, montelukast was still able to reduce the severity of EAE when given after the onset of the disease, suggesting, in addition to the preventive effect, also a possible therapeutic benefit of this drug. Relevantly, the infiltration of Th1+ and Th17+ cells in the inflamed area of the brain was reduced by the dual inhibitor of LOX/COX pathway flavocoxid and by montelukast in EAE mice [148, 154].

Finally, since GPR17 was found to be reexpressed or upregulated in demyelinating lesions in EAE and human MS plaques [155], GPR17 and purinergic signalling has been strongly suggested as targets for new reparative approaches in MS [155–157].

2.5. Epilepsy

Accumulating clinical and experimental evidence suggests that inflammatory mediators play a relevant role in the pathophysiology of epilepsy [158, 159]. Nevertheless, only few studies have investigated the role for LOX-derived arachidonic acid metabolites in epilepsy [160–162]. Leukotriene levels were found to increase in a time-dependent manner in the brain during kainate-induced seizures in rats [160], and LTD4 i.c.v. injection facilitated pentylenetetrazol- (PTZ-) induced seizures and increased BBB permeability in mice [163]. This effect could be relevant, since magnetic resonance imaging studies in patients with posttraumatic epilepsy demonstrated that the site of increased BBB permeability colocalized with the presumed epileptic focus [164] and animal studies found a positive correlation between the extent of BBB opening and the number of seizures [165].

Pharmacological inhibition of LOX using dual inhibitors of LOX/COX pathway phenidone [160, 166], which decreased the production of CysLTs, or BW755C [167] attenuated the seizure activity. Similarly, zileuton was shown to decrease spike-wave discharges in pilocarpine epileptic rats [168], strongly suggesting that leukotrienes play a role in epilepsy.

In line, montelukast and 1,2,3,4, tetrahydroisoquinoline, a LTD4 synthetic pathway inhibitor, suppressed the development of kindled seizures, as well as pilocarpine-induced spontaneous recurrent seizures in mice [162]. Bay-u9973, a nonselective CysLT receptor antagonist, montelukast, and pranlukast increased the latency to generalized seizures and decreased the mean amplitude of electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings during seizures in PTZ-injected mice [163]. Furthermore, montelukast prevented the PTZ-induced BBB disruption and leukocyte infiltration.

Clinical evidence highlights the efficacy of pranlukast in patients with intractable partial epilepsy. In fact, pranlukast reduced seizure frequencies probably normalizing MMP-9 in serum, reducing leakage of proinflammatory cytokines into CNS, and inhibiting extravasation of leucocytes from brain capillaries [22].

3. Conclusion

The interest in the field of LT research was traditionally focused on their effects on asthma and allergic disorders. Over the years, accumulating data have highlighted the involvement of these inflammatory mediators—and in particular of the CysLTs and their receptors—in a broader range of inflammation-associated diseases. Among them, the presence of elevated levels of CysLTs in CNS lesions, the evidence that polymorphisms within the LT biosynthesis pathways are associated with an increased risk of cerebral pathological events and the accumulating data obtained in animal studies, also suggested a role for CysLTs in cerebrovascular diseases.

Robust data sustain the role of this pathway in brain ischemia; nevertheless, to elucidate the involvement of the CysLT pathway in the other neurodegenerative disorders, further efforts, in experimental and clinical investigation, are needed. The antileukotriene drugs had been approved for the treatment of asthma more than 20 years ago, and promising evidence indicate their beneficial effects in the treatment of neurodegenerative disease. They show a limited toxicity and a good therapeutic-to-toxic ratio; nevertheless, before hypothesizing a translation to clinic, further studies are needed to underlie their molecular mechanism(s) and demonstrate the potential clinical benefits in the treatment of CNS disease. Moreover, remains to explore how other receptors able to bind the CysLTs, such as GPR17, could influence the development of CNS disease and to define their eventual therapeutic value.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Heise C. E., O'Dowd B. F., Figueroa D. J., et al. Characterization of the human cysteinyl leukotriene 2 receptor. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(39):30531–30536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haeggström J. Z., Funk C. D. Lipoxygenase and leukotriene pathways: biochemistry, biology, and roles in disease. Chemical Reviews. 2011;111(10):5866–5898. doi: 10.1021/cr200246d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch K. R., O'Neill G. P., Liu Q., et al. Characterization of the human cysteinyl leukotriene CysLT1 receptor. Nature. 1999;399(6738):789–793. doi: 10.1038/21658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellor E. A., Maekawa A., Austen K. F., Boyce J. A. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 is also a pyrimidinergic receptor and is expressed by human mast cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(14):7964–7969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141221498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brink C., Dahlén S. E., Drazen J., et al. International Union of Pharmacology XLIV. Nomenclature for the oxoeicosanoid receptor. Pharmacological Reviews. 2004;56(1):149–157. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciana P., Fumagalli M., Trincavelli M. L., et al. The orphan receptor GPR17 identified as a new dual uracil nucleotides/cysteinyl-leukotrienes receptor. The EMBO Journal. 2006;25(19):4615–4627. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bankova L. G., Lai J., Yoshimoto E., et al. Leukotriene E 4 elicits respiratory epithelial cell mucin release through the G-protein–coupled receptor, GPR99. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113(22):6242–6247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605957113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paruchuri S., Jiang Y., Feng C., Francis S. A., Plutzky J., Boyce J. A. Leukotriene E4 activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor and induces prostaglandin D2 generation by human mast cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(24):16477–16487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705822200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau W. K., Chow A. W., Au S. C., Ko W. Differential inhibitory effects of CysLT1 receptor antagonists on P2Y6 receptor-mediated signaling and ion transport in human bronchial epithelia. PloS One. 2011;6((7):e22363) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paruchuri S., Tashimo H., Feng C., et al. Leukotriene E4-induced pulmonary inflammation is mediated by the P2Y12 receptor. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2009;206(11):2543–2555. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holgate S. T., Peters-Golden M., Panettieri R. A., Henderson W. R. Roles of cysteinyl leukotrienes in airway inflammation, smooth muscle function, and remodeling. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2003;111(1 Supplement):S18–S36. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss J. W., Drazen J. M., Coles N., et al. Bronchoconstrictor effects of leukotriene C in humans. Science. 1982;216(4542):196–198. doi: 10.1126/science.7063880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicosia S., Capra V., Rovati G. E. Leukotrienes as mediators of asthma. Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2001;14(1):3–19. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2000.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuelsson B. Leukotrienes: mediators of immediate hypersensitivity reactions and inflammation. Science. 1983;220(4597):568–575. doi: 10.1126/science.6301011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang S. H., Wei E. Q., Zhou Y., et al. Increased expression of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-1 in the brain mediates neuronal damage and astrogliosis after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neuroscience. 2006;140(3):969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampson A. P., Pizzichini E., Bisgaard H. Effects of cysteinyl leukotrienes and leukotriene receptor antagonists on markers of inflammation. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2003;111(1 Supplement):S49–S61. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang S. H., Zhou Y., Chu L. S., et al. Spatio-temporal expression of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-2 mRNA in rat brain after focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience Letters. 2007;412(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao C. Z., Zhao B., Zhang X. Y., et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 is spatiotemporally involved in neuron injury, astrocytosis and microgliosis after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neuroscience. 2011;189:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji X., Trandafir C. C., Wang A., Kurahashi K. Effects of the experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage on the eicosanoid receptors in nicotine-induced contraction of the rat basilar artery. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2013;22(8):1258–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu H., Chen G., Zhang J. M., et al. Distribution of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 in human traumatic brain injury and brain tumors. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2005;26(6):685–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang W. P., Hu H., Zhang L., et al. Expression of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 in human traumatic brain injury and brain tumors. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;363(3):247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi Y., Imai K., Ikeda H., Kubota Y., Yamazaki E., Susa F. Open study of pranlukast add-on therapy in intractable partial epilepsy. Brain & Development. 2013;35(3):236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirshafiey A., Jadidi-Niaragh F. Immunopharmacological role of the leukotriene receptor antagonists and inhibitors of leukotrienes generating enzymes in multiple sclerosis. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 2010;32(2):219–227. doi: 10.3109/08923970903283662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu J., Praticò D. 5-lipoxygenase as an endogenous modulator of amyloid beta formation in vivo. Annals of Neurology. 2011;69(1):34–46. doi: 10.1002/ana.22234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nozaki M., Yoshikawa M., Ishitani K., et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonists inhibit tumor metastasis by inhibiting capillary permeability. The Keio Journal of Medicine. 2010;59(1):10–18. doi: 10.2302/kjm.59.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarau H. M., Ames R. S., Chambers J., et al. Identification, molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor. Molecular Pharmacology. 1999;56(3):657–663. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marschallinger J., Schäffner I., Klein B., et al. Structural and functional rejuvenation of the aged brain by an approved anti-asthmatic drug. Nature Communications. 2015;6:p. 8466. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu S.-y., Zhang X.-y., Wang X.-r., et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 mediates LTD4-induced activation of mouse microglial cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2014;35(1):33–40. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang X.-J., Zhang W.-P., Li C.-T., et al. Activation of CysLT receptors induces astrocyte proliferation and death after oxygen–glucose deprivation. Glia. 2008;56(1):27–37. doi: 10.1002/glia.20588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyritsis N., Kizil C., Zocher S., et al. Acute inflammation initiates the regenerative response in the adult zebrafish brain. Science. 2012;338(6112):1353–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.1228773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akiyama H., Barger S., Barnum S., et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2000;21(3):383–421. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00124-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanisch U.-K., Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10(11):1387–1394. doi: 10.1038/nn1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Z., Chopp M. Astrocytes, therapeutic targets for neuroprotection and neurorestoration in ischemic stroke. Progress in Neurobiology. 2016;144:103–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann H., Kotter M. R., Franklin R. J. M. Debris clearance by microglia: an essential link between degeneration and regeneration. Brain. 2008;132(Part 2):288–295. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ransohoff R. M., Perry V. H. Microglial physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annual Review of Immunology. 2009;27:119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graeber M. B., Streit W. J. Microglia: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathologica. 2010;119(1):89–105. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henn A. The suitability of BV2 cells as alternative model system for primary microglia cultures or for animal experiments examining brain inflammation. ALTEX. 2009;26(2):83–94. doi: 10.14573/altex.2009.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Y., Wei E. Q., Fang S. H., et al. Spatio-temporal properties of 5-lipoxygenase expression and activation in the brain after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Life Sciences. 2006;79(17):1645–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barreto G. E., Gonzalez J., Torres Y., Morales L. Astrocytic-neuronal crosstalk: implications for neuroprotection from brain injury. Neuroscience Research. 2011;71(2):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terashvili M., Sarkar P., Nostrand M. V., Falck J. R., Harder D. R. The protective effect of astrocyte-derived 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid on hydrogen peroxide-induced cell injury in astrocyte-dopaminergic neuronal cell line co-culture. Neuroscience. 2012;223:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katayama T., Sakaguchi E., Komatsu Y., Oguma T., Uehara T., Minami M. Sustained activation of ERK signaling in astrocytes is critical for neuronal injury-induced monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production in rat corticostriatal slice cultures. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;31(8):1359–1367. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sullivan S. M., Björkman S. T., Miller S. M., Colditz P. B., Pow D. V. Structural remodeling of gray matter astrocytes in the neonatal pig brain after hypoxia/ischemia. Glia. 2010;58(2):181–194. doi: 10.1002/glia.20911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qu Y., Duan Z., Zhao F., et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase upregulation attenuates astrocyte proliferation and promotes neuronal survival in the hypoxic–ischemic rat brain. Stroke. 2011;42(12):3542–3550. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pekny M., Pekna M. Astrocyte reactivity and reactive astrogliosis: costs and benefits. Physiological Reviews. 2014;94(4):1077–1098. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ballerini P., Di Iorio P., Ciccarelli R., et al. P2Y1 and cysteinyl leukotriene receptors mediate purine and cysteinyl leukotriene co-release in primary cultures of rat microglia. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 2005;18(2):255–268. doi: 10.1177/039463200501800208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X. Y., Wang X. R., Xu D. M., et al. HAMI 3379, a CysLT2 receptor antagonist, attenuates ischemia-like neuronal injury by inhibiting microglial activation. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2013;346(2):328–341. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.203604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo J. Y., Zhang Z., Yu S. Y., et al. Rotenone-induced changes of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 expression in BV2 microglial cells. Zhejiang da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2011;40(2):131–138. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang X.-Y., Chen L., Yang Y., et al. Regulation of rotenone-induced microglial activation by 5-lipoxygenase and cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1. Brain Research. 2014;1572:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chu L.-s., Wei E.-q., Yu G.-l., et al. Pranlukast reduces neutrophil but not macrophage/microglial accumulation in brain after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2006;27(3):282–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi Q. J., Wang H., Liu Z. X., et al. HAMI 3379, a CysLT2R antagonist, dose- and time-dependently attenuates brain injury and inhibits microglial inflammation after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neuroscience. 2015;291:53–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang X.-Q., Zhang X.-Y., Wang X.-R., et al. Transforming growth factor β1-induced astrocyte migration is mediated in part by activating 5-lipoxygenase and cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:p. 634. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Helgadottir A., Manolescu A., Thorleifsson G., Gretarsdottir S., Jonsdottir H., Thorsteinsdottir U., et al. The gene encoding 5-lipoxygenase activating protein confers risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. Nature Genetics. 2004;36(1):233–239. doi: 10.1038/ng1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bevan S., Dichgans M., Wiechmann H. E., Gschwendtner A., Meitinger T., Markus H. S. Genetic variation in members of the leukotriene biosynthesis pathway confer an increased risk of ischemic stroke: a replication study in two independent populations. Stroke. 2008;39(4):1109–1114. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.491969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ji R., Jia J., Ma X., Wu J., Zhang Y., Xu L. Genetic variants in the promoter region of the ALOX5AP gene and susceptibility of ischemic stroke. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2011;32(3):261–268. doi: 10.1159/000330341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang G., Liu R., Zhang J. The arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein (ALOX5AP) gene SG13S114 polymorphism and ischemic stroke in Chinese population: a meta-analysis. Gene. 2014;533(2):461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yi X., Zhang B., Wang C., Liao D., Lin J., Chi L. Genetic polymorphisms of ALOX5AP and CYP3A5 increase susceptibility to ischemic stroke and are associated with atherothrombotic events in stroke patients. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2015;24(3):521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Freiberg J. J., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Sillesen H., Jensen G. B., Nordestgaard B. G. Promotor polymorphisms in leukotriene C4 synthase and risk of ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2008;28(5):990–996. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.158873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Freiberg J. J., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Nordestgaard B. G. Novel mutations in leukotriene C4 synthase and risk of cardiovascular disease based on genotypes from 50,000 individuals. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2010;8(8):1694–1701. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ge Q. F., Wei E. Q., Zhang W. P., et al. Activation of 5-lipoxygenase after oxygen-glucose deprivation is partly mediated via NMDA receptor in rat cortical neurons. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;97(4):992–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi W. Z., Zhao C. Z., Zhao B., et al. Aggravated inflammation and increased expression of cysteinyl leukotriene receptors in the brain after focal cerebral ischemia in AQP4-deficient mice. Neuroscience Bulletin. 2012;28(6):680–692. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1281-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Y., Zhang L., Ye Y., et al. Cysteinyl leukotriene receptors CysLT1 and CysLT2 are upregulated in acute neuronal injury after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2006;27(12):1553–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sheng W.-W., Li C.-T., Zhang W.-P., et al. Distinct roles of CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors in oxygen glucose deprivation-induced PC12 cell death. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;346(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hu X., Ge Q.-F., Zhang W.-P., Wei E.-Q. Effects of cysteinyl receptor agonist and antagonists on rat primary cortical neurons. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2007;36(2):117–122. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang X. X., Zhang X. Y., Huang X. Q., et al. Effect of montelukast on morphological changes in neurons after ischemic injury. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2012;41(3):259–266. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu G. L., Wei E. Q., Wang M. L., et al. Pranlukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-1 antagonist, protects against chronic ischemic brain injury and inhibits the glial scar formation in mice. Brain Research. 2005;1053(1-2):116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baba T., Black K. L., Ikezaki K., Chen K., Becker D. P. Intracarotid infusion of leukotriene C4 selectively increases blood-brain barrier permeability after focal ischemia in rats. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1991;11(4):638–643. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Papadopoulos S. M., Black K. L., Hoff J. T. Cerebral edema induced by arachidonic acid: role of leukocytes and 5-lipoxygenase products. Neurosurgery. 1989;25(3):369–372. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198909000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang W.-P., Wei E.-Q., Mei R.-H., Zhu C.-Y., Zhao M.-H. Neuroprotective effect of ONO-1078, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, on focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2002;23(10):871–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shi Q. J., Xiao L., Zhao B., et al. Intracerebroventricular injection of HAMI 3379, a selective cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 antagonist, protects against acute brain injury after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Research. 2012;1484:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baskaya M. K., Hu Y., Donaldson D., et al. Protective effect of the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor AA-861 on cerebral edema after transient ischemia. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1996;85(1):112–116. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.1.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rao A. M., Hatcher J. F., Kindy M. S., Dempsey R. J. Arachidonic acid and leukotriene C4: role in transient cerebral ischemia of gerbils. Neurochemical Research. 1999;24(10):1225–1232. doi: 10.1023/A:1020916905312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ciceri P., Rabuffetti M., Monopoli A., Nicosia S. Production of leukotrienes in a model of focal cerebral ischaemia in the rat. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2001;133(8):1323–1329. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tu X.-K., Yang W.-Z., Shi S.-S., Chen C.-M., Wang C.-H. 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor zileuton attenuates ischemic brain damage: involvement of matrix metalloproteinase 9. Neurological Research. 2009;31(8):848–852. doi: 10.1179/174313209X403913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tu X. K., Yang W. Z., Wang C. H., et al. Zileuton reduces inflammatory reaction and brain damage following permanent cerebral ischemia in rats. Inflammation. 2010;33(5):344–352. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shi S., Yang W., Tu X., Wang C., Chen C., Chen Y. 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor zileuton inhibits neuronal apoptosis following focal cerebral ischemia. Inflammation. 2013;36(6):1209–1217. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9657-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ström J. O., Strid T., Hammarström S. Disruption of the alox5ap gene ameliorates focal ischemic stroke: possible consequence of impaired leukotriene biosynthesis. BMC Neuroscience. 2012;13(1):p. 146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-13-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kitagawa K., Matsumoto M., Hori M. Cerebral ischemia in 5-lipoxygenase knockout mice. Brain Research. 2004;1004(1-2):198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang L.-H., Wei E.-Q. Neuroprotective effect of ONO-1078, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, on transient global cerebral ischemia in rats. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2003;24(12):1241–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yu G.-L., Wei E.-Q., Zhang S.-H., Xu H.-M., Chu L.-S., Zhang W.-P., et al. Montelukast, a Cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-1 antagonist, dose- and time-dependently protects against focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Pharmacology. 2004;73(1):31–40. doi: 10.1159/000081072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao R., Shi W.-Z., Zhang Y.-M., Fang S.-H., Wei E.-Q. Montelukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-1 antagonist, attenuates chronic brain injury after focal cerebral ischaemia in mice and rats. The Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2011;63(4):550–557. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saad M. A., Abdelsalam R. M., Kenawy S. A., Attia A. S. Montelukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-1 antagonist protects against hippocampal injury induced by transient global cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in rats. Neurochemical Research. 2015;40(1):139–150. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu J. L., Zhao X. H., Zhang D. L., Zhang J. B., Liu Z. H. Effect of montelukast on the expression of interleukin-18, telomerase reverse transcriptase, and Bcl-2 in the brain tissue of neonatal rats with hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2015;14(3):8901–8908. doi: 10.4238/2015.August.3.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chu L.-S., Fang S.-H., Zhou Y., et al. Minocycline inhibits 5-lipoxygenase activation and brain inflammation after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2007;28(6):763–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wunder F., Tinel H., Kast R., et al. Pharmacological characterization of the first potent and selective antagonist at the cysteinyl leukotriene 2 (CysLT2) receptor. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;160(2):399–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ni N. C., Yan D., Ballantyne L. L., Barajas-Espinosa A., St. Amand T., Pratt D. A. A selective cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 2 antagonist blocks myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and vascular permeability in mice. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2011;339(3):768–778. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.186031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang M.-L., Huang X.-J., Fang S.-H., et al. Leukotriene D4 induces brain edema and enhances CysLT2 receptor-mediated aquaporin 4 expression. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;350(2):399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Qi L.-L., Fang S.-H., Shi W.-Z., et al. CysLT2 receptor-mediated AQP4 up-regulation is involved in ischemic-like injury through activation of ERK and p38 MAPK in rat astrocytes. Life Sciences. 2011;88(1-2):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Parhamifar L., Sime W., Yudina Y., Vilhardt F., Mörgelin M., Sjölander A. Ligand-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 triggers internalization and signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. PloS One. 2010;5(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014439.e14439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jiang Y., Borrelli L. A., Kanaoka Y., Bacskai B. J., Boyce J. A. CysLT2 receptors interact with CysLT1 receptors and down-modulate cysteinyl leukotriene dependent mitogenic responses of mast cells. Blood. 2007;110(9):3263–3270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lecca D., Trincavelli M. L., Gelosa P., et al. The recently identified P2Y-like receptor GPR17 is a sensor of brain damage and a new target for brain repair. PloS One. 2008;3(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003579.e3579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Temporini C., Ceruti S., Calleri E., et al. Development of an immobilized GPR17 receptor stationary phase for binding determination using frontal affinity chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Analytical Biochemistry. 2009;384(1):123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Parravicini C., Ranghino G., Abbracchio M. P., Fantucci P. GPR17: molecular modeling and dynamics studies of the 3-D structure and purinergic ligand binding features in comparison with P2Y receptors. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(1):p. 263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maekawa A., Balestrieri B., Austen K. F., Kanaoka Y. GPR17 is a negative regulator of the cysteinyl leukotriene 1 receptor response to leukotriene D 4. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(28):11685–11690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905364106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maekawa A., Xing W., Austen K. F., Kanaoka Y. GPR17 regulates immune pulmonary inflammation induced by house dust mites. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(3):1846–1854. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhao B., Zhao C. Z., Zhang X. Y., et al. The new P2Y-like receptor G protein-coupled receptor 17 mediates acute neuronal injury and late microgliosis after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neuroscience. 2012;202:42–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Daniele S., Lecca D., Trincavelli M. L., Ciampi O., Abbracchio M. P., Martini C. Regulation of PC12 cell survival and differentiation by the new P2Y-like receptor GPR17. Cellular Signalling. 2010;22(4):697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tintinger G. R., Feldman C., Theron A. J., Anderson R. Montelukast: more than a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonist? Scientific World Journal. 2010;10:2403–2413. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tsukada H., Fukumoto D., Nishiyama S., Sato K., Kakiuchi T. Transient focal ischemia affects the cAMP second messenger system and coupled dopamine D1 and 5-HT1A receptors in the living monkey brain: a positron emission tomography study using microdialysis. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2004;24(8):898–906. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000126974.07553.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lin W.-Y., Chang Y.-C., Lee H.-T., Huang C.-C. CREB activation in the rapid, intermediate, and delayed ischemic preconditioning against hypoxic-ischemia in neonatal rat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009;108(4):847–859. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3042.2008.05828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tanaka Y., Tanaka R., Liu M., Hattori N., Urabe T. Cilostazol attenuates ischemic brain injury and enhances neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of adult mice after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2010;171(4):1367–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schaal S. M., Garg M., Sen G. M., et al. The therapeutic profile of rolipram, PDE target and mechanism of action as a neuroprotectant following spinal cord injury. PloS One. 2012;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051337.e43634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mamedova L., Capra V., Accomazzo M. R., et al. CysLT1 leukotriene receptor antagonists inhibit the effects of nucleotides acting at P2Y receptors. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2005;71(1-2):115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pugliese A. M., Trincavelli M. L., Lecca D., et al. Functional characterization of two isoforms of the P2Y-like receptor GPR17: [35S]GTP S binding and electrophysiological studies in 1321N1 cells. AJP Cell Physiol. 2009;297(4):C1028–C1040. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00658.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Muthuraman A., Sood S. Antisecretory, antioxidative and antiapoptotic effects of montelukast on pyloric ligation and water immersion stress induced peptic ulcer in rat. Prostaglandins. Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids. 2010;83(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Coskun A. K., Yigiter M., Oral A., et al. The effects of Montelukast on antioxidant enzymes and proinflammatory cytokines on the heart, liver, lungs, and kidneys in a rat model of cecal ligation and puncture–induced sepsis. Scientific World Journal. 2011;11:1341–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mohamadin A. M., Elberry A. A., Elkablawy M. A., Gawad H. S. A., Al-Abbasi F. A. Montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist abrogates lipopolysaccharide-induced toxicity and oxidative stress in rat liver. Pathophysiology. 2011;18(3):235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Perez Velazquez J. L., Frantseva M. V. Carlen P. L. In vitro ischemia promotes glutamate-mediated free radical generation and intracellular calcium accumulation in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17(23):9085–9094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09085.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gan Y., Ji X., Hu X., et al. Transgenic overexpression of peroxiredoxin-2 attenuates ischemic neuronal injury via suppression of a redox-sensitive pro-death signaling pathway. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2012;17(5):719–732. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhou P., Qian L., D’Aurelio M., et al. Prohibitin reduces mitochondrial free radical production and protects brain cells from different injury modalities. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(2):583–592. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2849-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ingelsson E., Yin L., Bäck M. Nationwide cohort study of the leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast and incident or recurrent cardiovascular disease. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2012;129(3):702–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Alzheimer’s Association. 2014 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2014;10(2):e47–e92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Iqbal K., Liu F., Gong C.-X., Grundke-Iqbal I. Tau in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Current Alzheimer Research. 2010;7(8):656–664. doi: 10.2174/156720510793611592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Holtzman D. M., Morris J. C., Goate A. M. Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3(77):77sr1–77sr1. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1253863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bettcher B. M., Kramer J. H. Longitudinal inflammation, cognitive decline, and Alzheimer’s disease: a mini-review. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2014;96(4):464–469. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bouvier D. S., Murai K. K. Synergistic actions of microglia and astrocytes in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2015;45(4):1001–1014. doi: 10.3233/JAD-143156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ikonomovic M. D., Abrahamson E. E., Uz T., Manev H., Dekosky S. T. Increased 5-lipoxygenase immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2008;56(12):1065–1073. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.951855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Firuzi O., Zhuo J., Chinnici C. M., Wisniewski T., Praticò D. 5-lipoxygenase gene disruption reduces amyloid-beta pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. The FASEB Journal. 2008;22(4):1169–1178. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9131.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chu J., Giannopoulos P. F., Ceballos-Diaz C., Golde T. E., Pratico D. Adeno-associated virus-mediated brain delivery of 5-lipoxygenase modulates the AD-like phenotype of APP mice. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2012;7(1):p. 1. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Chu J., Giannopoulos P. F., Ceballos-Diaz C., Golde T. E., Praticò D. 5-lipoxygenase gene transfer worsens memory, amyloid, and tau brain pathologies in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Annals of Neurology. 2012;72(3):442–454. doi: 10.1002/ana.23642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 120.Chu J., Praticò D. Involvement of 5-lipoxygenase activating protein in the amyloidotic phenotype of an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2012;9(1):p. 127. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chu J., Praticò D. Pharmacologic blockade of 5-lipoxygenase improves the amyloidotic phenotype of an Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mouse model involvement of γ-secretase. The American Journal of Pathology. 2011;178(4):1762–1769. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 122.Wang X. Y., Tang S. S., Hu M., et al. Leukotriene D4 induces amyloid-β generation via CysLT1R-mediated NF-κB pathways in primary neurons. Neurochemistry International. 2013;62(3):340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tang S. S., Wang X. Y., Hong H., et al. Leukotriene D4 induces cognitive impairment through enhancement of CysLT₁ R-mediated amyloid-β generation in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2013;65:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Herbst-Robinson K. J., Liu L., James M., Yao Y., Xie S. X., Brunden K. R. Inflammatory eicosanoids increase amyloid precursor protein expression via activation of multiple neuronal receptors. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:p. 18286. doi: 10.1038/srep18286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lai J.'. E., Hu M., Wang H., et al. Montelukast targeting the cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 ameliorates Aβ1-42-induced memory impairment and neuroinflammatory and apoptotic responses in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Puccio S., Chu J., Praticò D. Involvement of 5-lipoxygenase in the corticosteroid-dependent amyloid beta formation: in vitro and in vivo evidence. PloS One. 2011;6(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015163.e15163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Giannopoulos P. F., Chu J., Joshi Y. B., et al. 5-lipoxygenase activating protein reduction ameliorates cognitive deficit, synaptic dysfunction, and neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;74(5):348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 128.Chu J., Lauretti E., Di Meco A., Praticò D. FLAP pharmacological blockade modulates metabolism of endogenous tau in vivo. Translational Psychiatry. 2013;3(12) doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.106.e333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Goodman Y., Steiner M. R., Steiner S. M., Mattson M. P. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid protects hippocampal neurons against amyloid beta-peptide toxicity, and attenuates free radical and calcium accumulation. Brain Research. 1994;654(1):171–176. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91586-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tang S.-S., Hong H., Chen L., et al. Involvement of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 in Aβ1–42-induced neurotoxicity in vitro and in vivo. Neurobiology of Aging. 2014;35(3):590–599. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lai J., Mei Z. L., Wang H., et al. Montelukast rescues primary neurons against Aβ1–42-induced toxicity through inhibiting CysLT1R-mediated NF-κB signaling. Neurochemistry International. 2014;75:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tang S.-S., Ji M., Chen L., et al. Protective effect of pranlukast on Aβ 1–42-induced cognitive deficits associated with downregulation of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;17(4):581–592. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713001314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Uz T., Pesold C., Longone P., Manev H. Aging-associated up-regulation of neuronal 5-lipoxygenase expression: putative role in neuronal vulnerability. The FASEB Journal. 1998;12(6):439–449. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.6.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]