Abstract

The present study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of erythropoietin (EPO) for improving cancer-associated malignant anemia. A search was performed for randomized clinical trials, conducted according to the Cochrane manual, using electronic databases including PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library and ClinicalTrails.gov up to 15 August 2015. A total of 6 eligible studies from 5 articles enrolling a total of 453 patients were entered into the current meta-analysis. Upon EPO treatment, there were significant differences in the change in hemoglobin (HB) levels compared with the placebo at short-term follow-up [mean difference (MD)=0.66; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.14–1.18; I2=Not applicable; P=0.01) and long-term follow-up (MD=0.10; 95% CI, 0.02–0.18; I2=Not applicable; P=0.01) under the random effects model. For changes in hematocrit (HCT) compared with the placebo, the results revealed there were significant differences at short-term follow-up (MD=2.47; 95% CI, 0.75–4.19; I2=Not applicable; P=0.005) and long-term follow-up (MD=7.60; 95% CI, 6.15–9.05; I2=Not applicable; P<0.00001) under the random effects model. Compared with the placebo in short-term follow-up under the fixed effects model with homogeneity, the result was a significant difference for the transfusion ratio [relative risk (RR)=0.81; 95% CI, 0.67- 0.97; I2=34%; P=0.02) and the transfusion requirements (MD=−0.45; 95% CI, −0.92, 0.03; I2=6%; P=0.07). Funnel plots did not detect any publication bias. These results suggest that EPO was beneficial to alleviate cancer-associated anemia and improve survival outcomes for patients with cancer.

Keywords: erythropoietin, cancer-associated malignant anemia, hemoglobin, meta-analysis

Introduction

Cancer anemia, also known as cancer-associated malignant anemia, is a common clinical symptom of cancer, with a rate of incidence approaching 50% of cancer cases (1,2). There are several causes of cancer-associated malignant anemia, such as bleeding, hemolysis, lack of nutrition, bone marrow necrosis and fibrosis caused by tumor cell infiltration, direct inhibition of red blood cells caused by radiotherapy and chemotherapy, relative insufficiency of erythropoietin (EPO) secretion (3), hematopoietic inhibition and influence of iron metabolism and reduced reactivity of EPO and cytokines from cancerous human bone marrow (4–6). Malignant tumor anemia is a common complication in various malignant tumors, in which red blood cell depletion leads to inadequate tissue oxygenation, reducing the sensitivity of tumors to radiation and chemotherapy, thereby lowering the patient's quality of life, decreasing survival time and affecting overall prognosis (4,7,8). At 3 years post-cancer diagnosis, mortality among patients with anemia is twice as high as that among those without anemia (9–12). Clinically speaking, quality of life and adverse events are important predictors in patients with cancer (8).

At present, there are four methods for treating cancer-associated anemia: Blood transfusion (primarily red blood cell suspension), iron supplements (reduced iron deposits caused by EPO treatment), change of treatment scheme and administration of stimulating factor (4,13). Blood transfusion is not without risks, particularly for patients with cancer. Blood transfusions may decrease the survival rate, and tumor recurrence may occur following blood transfusion, which may lead to poor prognosis. The effect of iron supplements alone is often slow, with low efficacy (2,5). EPO is a type of high-purity active glycoprotein produced using genetically modified technology, and it specifically stimulates bone marrow hematopoietic cells (13–15). Although a large body of research has demonstrated that the EPO is able to improve the symptoms of cancer-associated malignant anemia, this conclusion remains controversial. In order to assess the efficacy of EPO in this setting, the current study conducted a meta-analysis of the available research.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A series of electronic searches of PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library and ClinicalTrails.gov up to8 February 2016 for eligible randomized or parallel-group design clinical trials investigating EPO for the treatment of cancer-associated malignant anemia was performed using the following Medical Subject Headings and text words: ‘neoplasm*’, ‘tumor*’, ‘cancer*’, ‘erythropoietin’ and ‘anaemia*’.

Inclusion criteria

All studies were selected in accordance with following inclusion criteria: (1) All studies were randomized or parallel-group design clinical trials; (2) eligible studies included patients with cancer-associated malignant anemia patients older than 18 years; (3) the entire study population was patients diagnosed with cancer with malignant solid tumors confirmed by histology or cytology; (4) the hemoglobin (HB) levels of the patients were >8.5 and <13.5 g/dl; (5) eligible studies included at least one of the following outcomes: Change in HB, change in hematocrit (HCT), the ratio of transfusion and transfusion requirements during the treatment.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded in accordance with following criteria: (1) The study reported that the patients had received radiation, chemotherapy, or surgery prior to or during receiving EPO; (2) anemia was not caused by cancer; (3) the study included primary hematologic disease, seizure disorder, uncontrolled hypertension, recent history of thromboembolic disease (within 1 year), other clinically significant systemic disease, an active infectious process, pregnancy, ongoing blood loss, scheduled autologous blood donation or blood transfusion within the previous 30 days; (4) duplicate published research was excluded; (5) the data could not be extracted or obtained through contact with the original author.

Data extraction

The relevant information including study design, patients' characteristics, the criteria of tumor staging, tumor staging, the initial HB levels, interventions, controls and outcomes (change in HB, change in HCT, the ratio of transfusion or transfusion requirements) were independently extracted and entered it into a database by two investigators. When relevant research information was missing, particularly design or outcomes, the original authors were contacted for clarifications. Then, intention-to-treat (ITT) datasets were used for all outcomes whenever available. Disagreements between the two authors on data extraction were resolved by discussion. If the dispute persisted, other senior investigators were consulted to reach a consensus.

Statistical analysis

For the outcomes based on dichotomous data (16,17), relative risk (RR) as was utilized as an effect estimator, while for continuous outcomes mean difference (MD) was used (17,18). Subsequently, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P-values were calculated using RevMan 5.3 software (Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK) in all outcomes. A statistical test for heterogeneity was performed and an I2>40 was adopted as evidence for heterogeneity according to the Cochrane handbook (19). If the data were heterogeneous under the fixed effects model, a random effects model was utilized (20). Through observing asymmetry of funnel plots, publication bias was evaluated qualitatively (21). In a funnel plot, larger studies that provide a more precise estimate of an intervention's effect form the spout of the funnel, whereas smaller studies with less precision form the cone end of the funnel. Asymmetry in the funnel plot indicates potential publication bias. P≤0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Study selection and data collection

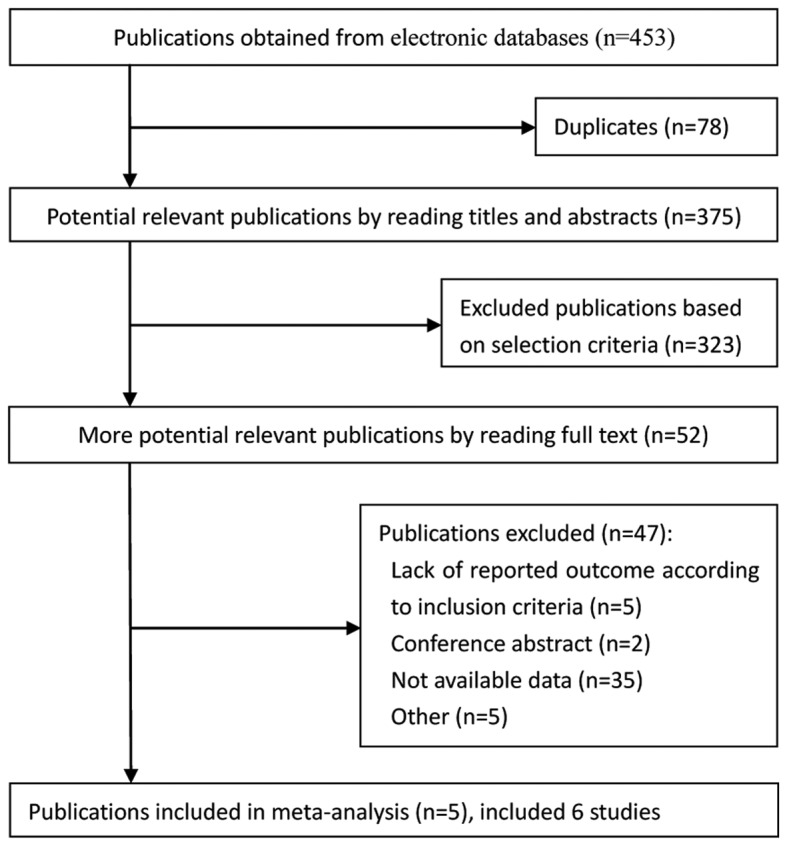

In total, 453 publications were obtained from electronic databases (Fig. 1). Based on the selection criteria, quantitative data was obtained for the current meta-analysis by reading all titles, abstracts and performing full text evaluations. Finally, 6 eligible studies from 5 articles were entered into the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Summary of trial identification and selection process.

Study characteristics

The search obtained 6 eligible studies from 5 articles (22–26), which enrolled a total of 595 patients. The change in HB was reported in 2 studies (23,26), the transfusion requirements were noted from 3 studies (23,25), the ratio of transfusion was obtained from a total of 233 of 495 patients from 5 studies (22–26) and the change in HCT was reported in 2 studies (23,26). Table I presents the clinical characteristics from all studies.

Table I.

Baseline information of the studies included.

| Usage, Dosage, Frequency | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author | Year | Country | Sample (F, I/C) | Age (I/C) | Criteria of tumor staging | Tumor staging (I/C) | Tumor location (I/C) | HB levels (I/C, g/dl) | EPO type | Intervention | Control | ITT/PP | (Refs.) |

| Kettelhack | 1998 | Germany | 48 (27)/54 (32) | 71 (53–87)/67 (37–91) | NA | NA | CC | 11.5 (10.5–12.5)/12.0 (11.0–13.1) | EPO beta | EPO 20,000 IU/day | Placebo | ITT | (22) |

| Scott | 2002 | USA | 29 (13)/29 (11) | 67.6±11.0/61.8±10.8 | AJCC 1997 | 1/1, II5/5, III 6/2, IV 17/21 | PC, BM | 10-13.5 | EPO alfa | EPO 600 IU/kg/day, 150 mg FeSO4, BID | 300 mg/day by FeSO4 | PP | (23) |

| Kosmadakis | 2003 | Greece | 31 (16)/32 (13) | 67.1±2.1/66.4±2 | NA | NA | Stomach 18%/19%, Colon 53%/52%, Rectum 29%/29% | 8.5–13 | EPO alfa | EPO, 100 mg/day iron | Placebo, 100 mg/day iron | ITT | (24) |

| Christodoulakis | 2005 | Greece | 67 (37)/68 (40) | 71 (36–92)/70 (44–89) | Dukes | A and B 28/26, C and D 31/32, unknown 8/10 | CC | 9–12 | EPO alfa | EPO 300 IU/kg/day, 200 mg/day iron | 200 mg/day iron | ITT | (25) |

| Christodoulakis | 2005 | Greece | 69 (38)/68 (40) | 72.5 (43–91)/70 (44–89) | Dukes | A and B 35/26, C and D 29/32, unknown 5/10 | CC | 9–12 | EPO alfa | EPO 150 IU/kg/day, 200 mg/day iron | 200 mg/day iron | ITT | (25) |

| Mystakidou | 2005 | Greece | 50 (28)/50 (33) | 63 (32–79)/64.5 (41–79) | NA | NA | PC 36%/16%, CC 16%/16%, GS 32%/22%, C: LC 18% | 10.15±0.15/9.87±0.50 | EPO alfa | EPO 40000 IU QD/BID, 200 mg/day iron | 200 mg/day iron | ITT | (26) |

AJCC, the American Joint Committee on Cancer; BM, Bone metastases; HB, Hemoglobin; I, Intervening group; C, Control group; CC, Colonic carcinoma; EPO, erythropoietin; F, female; GS, Genital system; ITT, Intention-to-treat; LC, lung cancer; PC, Prostate cancer; PP, Per protocol; NA, Not applicable; TNM, Tumor Node Metastasis; IU, international units; QD, daily; BID, twice daily.

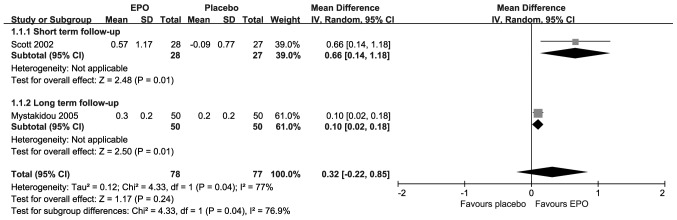

Change in HB

The change in HB levels is presented in Fig. 2; each included study suggested statistically significant improvements upon treatment with EPO. Compared with placebo, the results revealed there were significant differences in the short-term follow-up [MD=0.66; 95% CI, 0.14–1.18; I2=Not applicable (NA); P=0.01] and the long-term follow-up (MD=0.10; 95% CI, 0.02–0.18; I2=NA; P=0.01). However, the overall result revealed that there was not a significant difference (MD=0.32; 95% CI, −0.02–0.85; I2=77%; P=0.24) under substantial heterogeneity.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of change in hemoglobin. EPO, erythropoietin; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

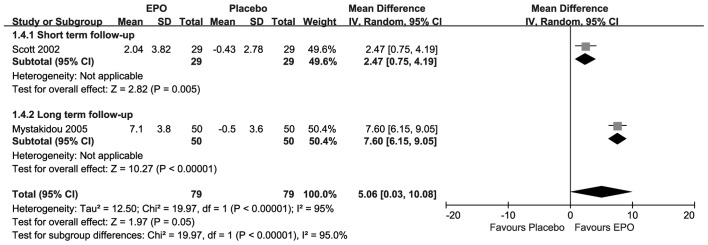

Change in HCT

As presented in Fig. 3, each included research suggested that there were statistically significant changes in HCT upon treatment with EPO. Compared with placebo, the results showed there were significant differences at both the short-term follow-up (MD=2.47, 95% CI, 0.75–4.19; I2=NA;P=0.005) and the long-term follow-up (MD=7.60; 95% CI, 6.15–9.05; I2=NA; P<0.00001). The overall result also revealed that there was a significant difference (MD=5.06; 95% CI, 0.03–10.08; I2=95%; P=0.05) under substantial homogeneity.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of change in hematocrit. EPO, erythropoietin; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

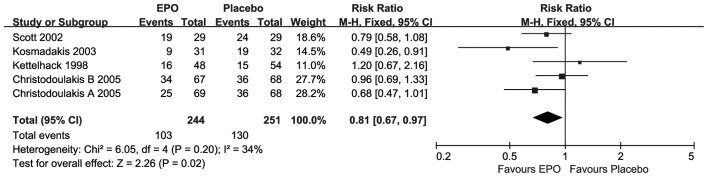

Ratio of transfusion

As presented in Fig. 4, for the ratio of transfusion only one study (24) suggested statistically significant improvements, upon EPO treatment. Compared with placebo, the overall meta-analysis result revealed that there was a significant difference (RR=0.81; 95% CI, 0.67–0.97; I2=34%; P=0.02) at short-term follow-up under moderate homogeneity.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the ratio of transfusion outcome. EPO, erythropoietin; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

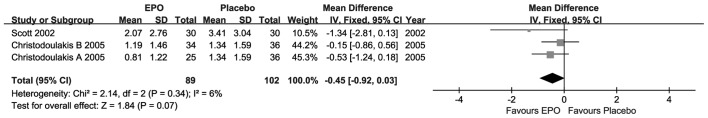

Transfusion requirements

For the transfusion requirements, as presented in Fig. 5, each included research suggested that there were no statistically significant differences, although the MD value was advantageous to EPO. Compared with placebo, the overall result revealed that there was no significant difference (MD=−0.45; 95% CI, −0.92–0.03; I2=6%; P=0.07) at short-term follow-up under weak homogeneity.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of transfusion requirements outcome. EPO, erythropoietin; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

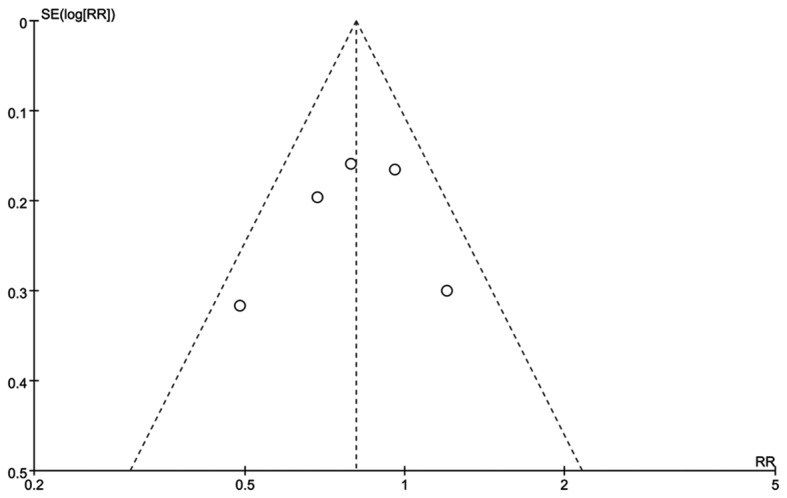

Publication bias

There was no potential publication bias based on symmetry from a funnel plot of the ratio of transfusion outcome (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Funnel plot of the ratio of transfusion.

Discussion

There are several potential causes of cancer-associated malignant anemia. These include bleeding, hemolysis, poor nutrition, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. However, as anemia reflects a shortage of red blood cells, which are produced in the bone marrow, cancer-associated anemia can also be caused by the inability of the bone marrow to produce them due to a relative deficiency of EPO. To establish if EPO significantly increased HB levels, and whether this was associated with improved energy levels and a reduction in blood transfusions, the current meta-analysis was performed with 6 eligible studies from 5 articles that included patients with cancer-associated anemia. The efficacy of EPO for cancer-associated malignant anemia was evaluated by measuring four types of outcome.

The results revealed that EPO improved HB levels, based on the change in HB, independent of the follow-up duration. While the overall result was not statistically significant, the finding is supported by previous studies (26,27). The overall result did not reach statistical significance primarily due to the small sample size. Cancer-associated anemia reduced the HCT level below normal, which was reversed by EPO at the short-and long-term follow-ups. With respect to transfusion requirements and the ratio of transfusion, EPO reduced the need for transfusions. The HB levels were increased owing to stimulation by EPO, which improved the patients' anemic state, thereby reducing the demand for transfusions. EPO is a highly glycosylated (40% of total molecular weight) compound with half-life of ~5 h in the blood, which may vary between its endogenous and various recombinant versions (28). Additional glycosylation or other alterations of EPO via recombinant technology increases its stability in blood (thus reducing the frequency of injections required) (29). EPO binds to the EPO receptor on the red cell progenitor surface and activates a Janus kinase 2 signaling cascade. EPO receptor expression is found in a number of tissues, such as bone marrow and peripheral/central nervous tissue. In the bloodstream, red cells themselves do not express EPO receptors, so they are not able to respond to EPO (30). However, indirect dependence of red cell longevity in the blood on plasma erythropoietin levels has been reported, a process termed neocytolysis (31). The majority of anemic patients with cancer of the gastrointestinal tract have iron deficiency due to subclinical blood loss; therefore, an iron supplement has been advocated (32). In particular, anemia is common in patients with colorectal cancer, as they are more likely to experience a loss and malabsorption of iron (33). However, iron supplementation (5,34) has not been found to be able to stimulate erythropoiesis to a sufficient degree to facilitate autologous blood donation or to reduce the need for allogeneic blood transfusions in patients with cancer (32). This may be due to a reticulo-endothelial blockage of iron, characteristic of several other conditions observed in these patients (35). The treatment scheme combining EPO with iron resulted in a more profound HB increase with intravenous iron, which may contribute to a superior optimization of the patient's condition and possibly a decrease in postoperative morbidity (33).

The advantage of the current meta-analysis was that itincluded studies to explain the effect of EPO from four comprehensive aspects ofblood indicators (20). Thestudy had several limitations. Firstly, only a small number of trials met the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the meta-analysismay have benefitted from more associatedclinical research to support its findings (17). Secondly, certain trials had missing data (36), which was a source of heterogeneity, and the current studywas unable to perform meta-regression for confounding factors.

In conclusion, the currentstudy suggests that EPO reduces cancer-associated anemia as well as improving relevant blood parameters among this patient population.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- EPO

erythropoietin

- HB

hemoglobin

- HCT

hematocrit

- MeSH

medical subject headings

- ITT

intention-to-treat

- MD

mean difference

- NA

not applicable

References

- 1.Mercadante S, Gebbia V, Marrazzo A, Filosto S. Anaemia in cancer: Pathophysiology and treatment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2000;26:303–311. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2000.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henry DH. Supplemental Iron: A key to optimizing the response of cancer-related anemia to rHuEPO? Oncologist. 1998;3:275–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasper C, Terhaar A, Fosså A, Welt A, Seeber S, Nowrousian MR. Recombinant human erythropoietin in the treatment of cancer-related anaemia. Eur J Haematol. 1997;58:251–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1997.tb01663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pronzato P. Cancer-related anaemia management in the 21st century. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32(Suppl 2):S1–S3. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludwig H, Evstatiev R, Kornek G, Aapro M, Bauernhofer T, Buxhofer-Ausch V, Fridrik M, Geissler D, Geissler K, Gisslinger H, et al. Iron metabolism and iron supplementation in cancer patients. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2015;127:907–919. doi: 10.1007/s00508-015-0893-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Littlewood TJ. Erythropoietin for the treatment of anemia associated with hematological malignancy. Hematol Oncol. 2001;19:19–30. doi: 10.1002/hon.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glaspy J. The impact of epoetin alfa on quality of life during cancer chemotherapy: A fresh look at an old problem. Semin Hematol. 1997;34(3 Suppl 2):S20–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandberg Y. Assessing the impact of cancer-related anaemia on quality of life and the role of rHuEPO. Med Oncol. 2000;17(Suppl 1):S23–S31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice L, Alfrey CP, Driscoll T, Whitley CE, Hachey DL, Suki W. Neocytolysis contributes to the anemia of renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:59–62. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(99)70258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leng HM, Albrecht CF, Kidson SH, Folb PI. Erythropoietin production in anemia associated with experimental cancer. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:806–810. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(99)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feelders RA, Vreugdenhil G, Eggermont AM, Kuiper-Kramer PA, van Eijk HG, Swaak AJ. Regulation of iron metabolism in the acute-phase response: Interferon gamma and tumour necrosis factor alpha induce hypoferraemia, ferritin production and a decrease in circulating transferrin receptors in cancer patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 1998;28:520–527. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1998.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung IJ, Dai C, Krantz SB. Stem cell factor increases the expression of FLIP that inhibits IFNgamma -induced apoptosis in human erythroid progenitor cells. Blood. 2003;101:1324–1328. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez S, ánchez CA. Recommendation of the scientific societies on the treatment of anaemia in cancer patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9:582–589. doi: 10.1007/s12094-007-0107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia JM Jurado, Sánchez E Torres, Hidalgo D Olmos, Alba Conejo E. Erythropoietin pharmacology. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9:715–722. doi: 10.1007/s12094-007-0128-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahlqvist-Rastad J, Albertsson M, Bergh J, Birgegård G, Johansson P, Jonsson B, Kjellen E, Påhlman S, Zackrisson B, Osterborg A. Erythropoietin therapy and cancer related anaemia: Updated Swedish recommendations. Med Oncol. 2007;24:267–272. doi: 10.1007/s12032-007-0037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deeks JJ. Issues in the selection of a summary statistic for meta-analysis of clinical trials with binary outcomes. Stat Med. 2002;21:1575–1600. doi: 10.1002/sim.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Oct 1;2011 ]. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walter SD, Yao X. Effect sizes can be calculated for studies reporting ranges for outcome variables in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:849–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henke M, Laszig R, Rübe C, Schäfer U, Haase KD, Schilcher B, Mose S, Beer KT, Burger U, Dougherty C, Frommhold H. Erythropoietin to treat head and neck cancer patients with anaemia undergoing radiotherapy: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:1255–1260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Copas J, Shi JQ. Meta-analysis, funnel plots and sensitivity analysis. Biostatistics. 2000;1:247–262. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kettelhack C, Hönes C, Messinger D, Schlag PM. Randomized multicentre trial of the influence of recombinant human erythropoietin on intraoperative and postoperative transfusion need in anaemic patients undergoing right hemicolectomy for carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1998;85:63–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott SN, Boeve TJ, McCulloch TM, Fitzpatrick KA, Karnell LH. The effects of epoetin alfa on transfusion requirements in head and neck cancer patients: A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1221–1229. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200207000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosmadakis N, Messaris E, Maris A, Katsaragakis S, Leandros E, Konstadoulakis MM, Androulakis G. Perioperative erythropoietin administration in patients with gastrointestinal tract cancer: Prospective randomized double-blind study. Ann Surg. 2003;237:417–421. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200303000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christodoulakis M, Tsiftsis DD. Hellenic Surgical Oncology Perioperative EPO Study Group: Preoperative epoetin alfa in colorectal surgery: A randomized, controlled study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:718–725. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mystakidou K, Kalaidopoulou O, Katsouda E, Parpa E, Kouskouni E, Chondros C, Tsiatas ML, Vlahos L. Evaluation of epoetin supplemented with oral iron in patients with solid malignancies and chronic anemia not receiving anticancer treatment. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3495–3500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lacson E, Jr, Ofsthun N, Lazarus JM. Effect of variability in anemia management on hemoglobin outcomes in ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:111–124. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rainville N, Jachimowicz E, Wojchowski DM. Targeting EPO and EPO receptor pathways in anemia and dysregulated erythropoiesis. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2016;20:287–301. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2016.1090975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh PK, Devasahayam M, Devi S. Expression of GPI anchored human recombinant erythropoietin in CHO cells is devoid ofglycosylation heterogeneity. Indian J Exp Biol. 2015;53:195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aapro M. Emerging topics in anaemia and cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 10):x289–x293. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice L, Alfrey CP. The negative regulation of red cell mass by neocytolysis: Physiologic and pathophysiologic manifestations. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2005;15:245–250. doi: 10.1159/000087234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Means RT, Jr, Krantz SB. Progress in understanding the pathogenesis of the anemia of chronic disease. Blood. 1992;80:1639–1647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borstlap WA, Buskens CJ, Tytgat KM, Tuynman JB, Consten EC, Tolboom RC, Heuff G, van Geloven AA, van Wagensveld BA, Wientjes CA, et al. Erratum to: Multicentre randomized controlled trial comparing ferric (III)carboxymaltose infusion with oral iron supplementation in the treatment of preoperative anaemia in colorectal cancer patients. BMC Surg. 2015;15:110. doi: 10.1186/s12893-015-0090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laï-Tiong F, Brami C, Dubroeucq O, Scotté F, Curé H, Jovenin N. Management of anemia and iron deficiency in a cancer center in France. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:1091–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2877-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braga M, Gianotti L, Vignali A, Gentilini O, Servida P, Bordignon C, Di Carlo V. Evaluation of recombinant human erythropoietin to facilitate autologous blood donation before surgery in anaemic patients with cancer of the gastrointestinal tract. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1637–1640. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800821216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson D, White IR, Mason D, Sutton S. A general method for handling missing binary outcome data in randomized controlled trials. Addiction. 2014;109:1986–1993. doi: 10.1111/add.12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]