Abstract

Aims

We examined effect of vascular or Lewy body co-pathology in subjects with autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer’s disease (AD) on the rate of cognitive and functional decline and transition to dementia.

Methods

In an autopsy sample of prospectively characterized subjects from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center database, neuropathology diagnosis was used to define the groups of pure AD (pAD, n=84), mixed vascular and AD (ADV, n=54), and mixed Lewy body disease and AD (ADLBD, n=31). Subjects had initial CDR-Global (CDR-G) score <1, MMSE ≥15, a final visit CDR-G>1, ≥3 evaluations, and Braak tangle stage ≥ III. We compared the rate of cognitive and functional decline between the groups.

Results

The rate of functional and cognitive decline was lower for ADV and had less severe deficits on CDR-G and CDR-SB scores at last visit than pAD and ADLBD. No significant differences were noted between ADLBD and pAD. After controlling for age at death, the odds of reaching CDR ≥1 at last visit was lower in the ADV subjects compared to pAD subjects.

Conclusions

The mean rate of functional and cognitive decline among ADV subjects was slower than either pAD or ADLBD. Vascular pathology did not increase odds of CDR≥1 when occurring with AD in this national cohort.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, vascular dementia, Lewy Body dementia, mixed dementia, rate of decline

Introduction

Mixed dementia (MD) is characterized by the co-occurrence of more than one type of neuropathology that contributes to cognitive decline. Multiple studies have suggested that MD is more common than previously recognized, with significant proportion of subjects with dementia having mixed pathologies [1–8]. The prevalence rates of MD in autopsy series has been reported in the range from 2 to 56% in retrospective studies and 2.9 to 54% in prospective studies [6]. Alzheimer’s pathology is found most commonly in combination with vascular disease (ADV), followed by Alzheimer’s pathology with Lewy body disease (ADLBD). Vascular dementia with LBD is less common [4, 7–9].

The nature of interaction between co-pathologies with AD in impacting functional and cognitive decline has been debated. Early studies noted the possibility that older individuals with neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques have a lower threshold of dementia when there are co-occurring vascular lesions [10]. Vascular disease was noted to increase clinical dementia severity in persons with AD pathology [11, 12]. Worse cognitive function with co-occurring vascular pathology in the lower pathologic stages of AD, but notably not at higher levels of AD pathology, was also reported [13]. The rate of decline on Mini Mental State Exam scores (MMSE) was noted to decrease slightly with advancing age for subjects with AD alone, but increased with age for subjects with MD [14]. In these early reports the numbers of subjects with MD in the autopsy series was often small and due to the limited data not all subjects had longitudinal follow ups of three or more years nor did they all start from a common pre-dementia baseline.

More recent studies, many with larger number of subjects, suggest a weaker direct interaction between vascular and AD pathologies or even both being independent processes. The Religious Orders study noted that beyond their additive effect, infarctions do not increase the likelihood of dementia [15]. In a clinical study using AD biomarkers, cardiovascular risk profiles were not predictive of progression in CSF β42-amyloid,[18F] fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET uptake and MRI hippocampal atrophy [16], while another reported amyloid burden and vascular risk were found to interact in the parietal brain region alone [17]. Among cognitively normal elderly participants a recent study, using imaging correlates of amyloid and vascular pathology, noted that amyloid and vascular pathologies seem to be at least partly independent processes and that both impact longitudinal cognitive trajectories adversely [18]. An evidence-based review did not find strong support for the proposition that vascular risk factors increase AD pathology [19]. Studies evaluating rate of cognitive decline among non-demented elders in the Rush Memory and Aging project and Religious Orders Study noted that macroscopic and microinfarcts were not significantly associated with a faster rate of decline on a global cognition measure when compared to the presence of amyloid pathology alone [15, 20].

Following these reports, the impact of vascular co-pathology on cognitive decline among subjects with AD pathology is again of intense interest. An outstanding question from this literature is whether ADV patients are more likely to have a faster progression and more severe cognitive and functional deficits before death than those with AD pathology alone? An autopsy cohort with mixed AD and vascular co-pathology and pure AD diagnoses from a national sample who developed dementia during their longitudinal follow up is necessary to complement previous reports.

Among MD patients with co-occurring AD and Lewy body disease (ADLBD), similar controversy reigns on the role of each of these pathologies in impacting rate of cognitive and functional decline. In addition, in ADLBD cases both the amount and the topographical distribution of pathological protein aggregates (Aβ, phospho-τau, α-synuclein) was noted to impact the clinical phenotype [21]. Co-occurrence of AD and Lewy body pathology is common with studies reporting ADLBD in 14%–26% of demented patients, and “pure” LBD in 0%–19% of demented subjects [5]. A meta-analysis of LBD studies noted comparable rates of decline in LBD and AD on MMSE [22]. Studies on MD reported faster decline among subjects with AD and Lewy body co-pathology compared to “pure” AD [23,24]. Among non-demented elders with AD and Lewy body co-pathology the Rush Memory and Aging project and Religious Orders Study noted that neocortical Lewy bodies were associated with a faster rate of decline (unlike the case for vascular co-pathology) [20]. The literature on co-occurring LBD and AD pathology on rate of cognitive decline is smaller compared to ADV. The MD with LBD reports similar to ADV reports have smaller numbers of subjects in their analysis and subjects were often not followed longitudinally starting from a pre-dementia state to death in order to best characterize their rate of decline.

We undertook the current study in a national autopsy cohort, the National Alzheimer’s Disease Coordinating Center (NACC), to characterize subjects with AD pathology with/without vascular disease or LBD co-pathology. We examined: 1) the odds of dementia onset during longitudinal follow up when all subjects started from a pre-dementia state (CDR < 1) 2) the severity of cognitive and functional deficits in MD and pAD before death 3) the rate of cognitive and functional decline in MD and pAD. We hypothesized that subjects having mixed pathologies, that is, ADV and ADLBD, would have higher odds of onset of dementia before death, more severe cognitive and functional deficits at last visit before death, and a faster rate of cognitive and functional decline than subjects with pAD.

Methods

Materials and methods

The NACC maintains a database of participant information collected from 34 past and present Alzheimer’s Disease Centers funded by the National Institute on Aging. Data from the uniform data set (UDS) maintained by NACC between September 2005 and May 2012 was used for the present analysis. Details on data collection and curating are well documented [25]. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR-Global) Scale assesses the participant’s current cognitive and functional status. The level of impairment in the domains or ‘boxes’ of memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care are rated. The CDR-Global (CDR-G) ratings are calculated using a complex algorithm and range from 0 (no dementia) to 3 (severe dementia) [26]. The CDR Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) is an operationalized measure of cognitive and functional ability. CDR-SB scores are calculated by simply adding the ‘box scores’, and range from 0 to 18 (higher scores indicate more impairment).

For the purpose of this analysis, dementia was defined as CDR-G ≥1. Rationale for subject inclusion/exclusion criteria was to determine the likelihood of onset of dementia (transition to CDR-G ≥ 1) across the groups, to reduce the potential effect of the large variability of initial cognitive deficits on the rate of decline analysis (by limiting initial CDR-G <1 and MMSE >15) [27]. By starting longitudinal follow up from a CDR-G<1, we hoped to facilitate comparison between subjects with similar initial severity of cognitive and functional deficits. All subjects included in the analysis had a final CDR-G score ≥1 before death. The mean time from last visit to death was <1 year. The subjects included in the analysis had a minimum of 3 longitudinal visits. Age at symptom onset was determined by the UDS question, ‘What age did the cognitive decline begin’ (based upon the clinician’s assessment) and symptom duration was calculated from the age at death to symptom onset. Patient characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics Mean and Std Dev

| ADLBD | ADV | Pure AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 31 | 54 | 84 |

| % Female | 29% | 50% | 46% |

| Mean Edu Yrs | 17.1(2.7)3 | 14.5(2.8)1,3 | 15.9(2.8)1 |

| APOE 4% | 61%3 (n=14) |

40%1,3 (n=17) |

46%1 (n=29) |

| Mean Age at Symptoms per clinician, Yrs | 71.3(8.1)3 | 79.3(12.3)1,3 | 71.6(13.3)1 |

| Mean Age at Change in CDRG≥1, Yrs | 77.6(8.2)3 | 85.8(10.8)1,3 | 77.8(13.1)1 |

| Mean Age at Death, Yrs | 79.3(8.4)3 | 87.5(10.2)1,3 | 80.0(12.9)1 |

| Duration of Symptoms, Yrs | 8.1 (2.8) | 7.7 (3.5) | 8.5 (3.4) |

| Mean Time last visit to death, Yrs | 0.13(0.6) | 0.17(0.6) | 0.21(0.6) |

P<0.01

= Significant difference between pure AD & ADV

=Significant difference between pure AD & ADLBD

=Significant difference between ADV & ADLBD

Neuropathology

The primary and secondary diagnosis for each of the subjects in the analysis was made by the neuropathologist at autopsy based on the burden of pathology. AD pathology was noted as ‘pure’ (pAD) if the primary pathologic diagnosis was AD and if there was no other contributing pathologic diagnosis. The neurofibrillary tangle stage in all MD cases was Braak stage III or greater and with moderate or frequent grading of neuritic and/or diffuse plaques. The data on diffuse and neuritic plaques were also collected for all subjects. The ADV group was defined as those subjects with either a primary pathologic diagnosis of vascular disease with a contributing pathologic diagnosis of AD or a primary diagnosis of AD and secondary diagnosis of vascular disease. The ADLBD group was defined as those subjects with both a primary pathologic diagnosis of Lewy body disease and a contributing pathologic diagnosis of AD or if the primary pathologic diagnosis was AD and Lewy body disease was a secondary diagnosis. Subjects with any other additional diagnoses listed were not considered for analysis. The minimum threshold of Braak stage III was chosen as just over half the individuals with Braak NFT stage III or IV and intermediate CERAD neuritic plaque score have been reported to have at least mild dementia in the NAAC data set [28]. The vascular pathology described at autopsy include: large infracts, micro infarcts, hemorrhages, lacunes and arteriosclerosis. Details on NAAC vascular pathology coding have been previously described [29]. See supplementary table 1.

Neuropsychological Measures

A core battery of neuropsychological measures was administered to all participants at each visit [30]. All four cognitive domains documented in the UDS were evaluated: attention, executive functioning, language, and memory. Attention was assessed using the Digit Span subtest (Digits Forward) from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) [31] and the Trail-Making Test (TMT) Part A [32]. Executive functioning was quantified using WAIS Digit Span (Digits Backwards) [33] and Trail Making Test Part B [30,31]. Language was assessed using the 30-item version of the Boston Naming Test (BNT) [34]. Memory was evaluated using the Logical Memory subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale [34]. Table 2 notes the detailed neuropsychological characteristics of the subjects at initial and final visits.

Table 2.

Neuropsychology measures Initial and final visit scores, Mean and Std Devs

| INITIAL VISIT | ADLBD | ADV | Pure AD |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDR: Global | 0.5 (0)−3 | 0.4 (0.2)3 | 0.4 (0.2) |

| CDR: Sum of Boxes | 2.5 (1.1)3 | 1.8 (1.3)3 | 2.1(1.4) |

| Functional Activities Questionnaire | 10.1 (6.8) | 9.1(7.1) | 7.6(7.2) |

| MMSE | 25.0(3.1) | 25.3(3.5) | 25.6(3.5) |

| Logical Memory: Learning | 7(4.6)1 | 8.5(5.1) | 6.7(4.5) |

| Logical Memory: Delayed recall | 6 (4.6)1 | 6.6 (5.4) | 4.6 (4.6) |

| Digit Span – Forward | 6(1) | 6.1(1.1) | 6.2(1.2) |

| Digit Span – Backward | 4(1) | 4.2(1.2) | 4(1.2) |

| Trail Making Test – Part A (Sec) | 62.4 (28) | 57 (30) | 62(32) |

| Trail Making Test– Part Β (Sec) | 217.2(81.2) | 189.7 (85.4) | 179.1 (87.4) |

| Boston Naming Test | 23.8(4.4) | 22.7 (6) | 23.8(5.6) |

| FINAL VISIT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CDR: Global | 2.1 (0.8)3 | 1.7(0.8)1,3 | 2.1 (0.8)1 |

| CDR: Sum of Boxes | 12.6 (4.1)3 | 10.2(4.7)1,3 | 12.5(4.5)1 |

| Functional Activities Questionnaire | 27.6(3.7) | 27.1(4.3) | 27.6(3.9) |

| MMSE | 15.3 (8) | 16.9(7.1) | 14.2(6.1) |

| Logical Memory: Learning | 3.5(3.9) | 5.1(5.8)) | 2.3(2.9) |

| Logical Memory: Delayed recall | 2.8(3.4) | 2.9(4.6) | 1.1(2) |

| Digit Span – Forward | 5.3(1.1) | 5.7(1.1) | 4.9(1.7) |

| Digit Span – Backward | 2.4(1.5) | 3.3(1.2) | 2.9(1.3) |

| Trail Making Test – Part A (Sec) | 102.4(48) | 98.1(39.8) | 104.5(48.9) |

| Trail Making Test – Part Β (Sec) | 262.7(81.6) | 203.9(101.9) | 227.4(82.6) |

| Boston Naming Test | 19.3(7.5) | 17.9(6.7) | 15(8.5) |

P<0.01,

= Significant difference between pure AD & ADV,

=Significant difference between pure AD & ADLBD

=Significant difference between ADV & ADLBD

Statistical analysis

Tukey Kramer adjusted pairwise comparisons were undertaken to evaluate the demographic differences, initial and final neuropsychological variables and pathology measures between the groups. A difference of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To evaluate the rate of cognitive decline across the groups, an initial analysis of the matrix of population and demographic variables of interest using the co-linearity diagnostics of variance inflation and condition indices was performed. Results indicated that patient age, gender, APOE ε4 status, diffuse and neuritic plaque burden, and mean duration of symptoms were sufficiently independent of one another to permit their inclusion in a multivariable analysis. Independent sample t-test was used for testing differences in mean slopes.

The method of repeated measures mixed models was next used to assess correlations between neuropsychological measures and these variables across time. Rate of change on CDR-G, CDR-SB, MMSE, and Logical Memory immediate and delayed recall were evaluated for assessing cognitive and functional decline. Backward elimination regression methods were used to construct reduced models for each of the neuropsychological measures. A reduced model is one which only contains terms with significance p ≤ 0.05 were included. Comparisons of rates of decline were made using methods outlined by Larson [35].

All the analyses were done with SAS version 9.3 software.

Results

Subject Sample

A total of 692 NACC subjects had a neuropathologic diagnosis in the pre-specified time frame. Of the 692 subjects, 169 subjects met all inclusion/exclusion clinical and pathological criteria. Flow chart for subject selection is noted in Supplementary Figure 1. There were 84 pAD subjects, 54 ADV, and 31 ADLBD identified in this sample.

Impact of age on dementia types

The percentage of individuals with CDR-G ≥1 (stage of dementia) increased with age for all three pathology groups, but the mean age of transition to CDR-G ≥1 was significantly younger in ADLBD and pAD groups than the ADV group (77.6, 77.9, and 85.8 yrs respectively, P <0.0001, Tukey-Kramer adjusted pairwise comparison). (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative distribution of CDR-G≥1 versus patient age

Mean age at death was similar between ADLBD and pAD (79.3 vs. 80 years), but was significantly higher in ADV (87.5 years) (P<0.0001, Tukey-Kramer adjusted pairwise comparison). (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Duration of symptoms

The duration of symptoms was calculated from the age estimated by the clinician as when the cognitive decline began to age at death. Mean duration of symptoms was not significantly different between the three groups (P>0.05 Tukey-Kramer adjusted pairwise comparison) (Table 1).

The fraction of subjects developing dementia at each year of longitudinal follow up and the odds of dementia before death

Even as the mean age of transition to CDR-G ≥1 was different across groups, the fraction of subjects attaining CDR-G ≥1 at each year before death was similar irrespective of the pathology group. An analysis of the Kaplan-Meier curves indicated no significant differences between the groups. The Log-Rank test for differences between the curves was not significant (P = 0.87, Figure 2). As the mean age at death was significantly higher in ADV, after controlling for age at visit, the odds of an ADV subject with CDR ≥ 1 at last visit before death are 70% of those of a pAD subject (O.R:0.7, 95% CI: 0.50 to 0.96, p<0.030). The odds of an ADLBD subject with CDR ≥ 1 at last visit were not statistically greater than those of a pAD subject after controlling for age at visit (O.R:1.06, 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.53, p= 0.74).

Figure 2.

Probability of development of dementia (CDR-G≥1) vs time to death

The severity of cognitive and functional deficits at initial visit and before death among dementia types

The mean final CDR-G and CDR-SB scores were significantly lower in ADV versus pAD (P < 0.01, Tukey-Kramer adjusted pairwise comparisons). The initial and final CDR scores for ADLBD were similar to the pAD group, but significantly higher than the ADV group (p<0.01, corrected for multiple comparisons). Among other neuropsychology measures analyzed, no overall significant group differences were seen on any initial or final neuropsychology scores (Table 2). When pairwise comparisons were examined, the Logical Memory immediate recall score was different between groups, with the pAD subjects having more deficits in Logical Memory at final visit (P <0.05).

The rate of cognitive and functional decline among dementia types

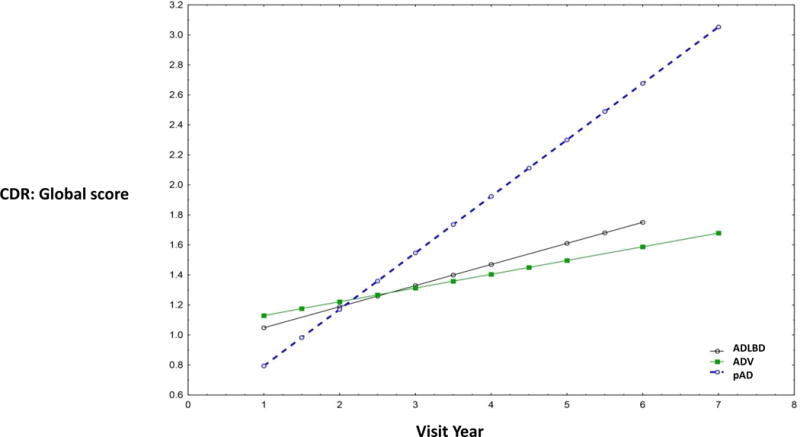

In a repeated measures mixed model, the rate of decline (by visit number and also by subject age) on the CDR-SB, CDR-G and MMSE scores in the ADV group was slower than the ADLBD and pAD groups. (CDR-SB, CDR-G and MMSE: P < 0.0001, Independent samples t-test). This result was noted even after controlling for age, sex, APOE ε4 status, years of education, duration of symptoms, and amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary tangle staging. No significant differences were noted in the rate of decline of Logical Memory immediate recall and delayed recall scores for the three groups. (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

Slope coefficients from method of repeated measures mixed models controlling for age, sex, APOε 4 status, diffuse and neuritic plaque burden, and mean duration of symptoms

| CDR-G | CDR-SB | MMSE | Logical Memory Immediate Recall | Logical Memory Delayed Recall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure AD | 0.341 | 2.11 | −2.431 | −0.99 | −0.81 |

| ADV | 0.221,3 | 1.51,3 | −1.171,3 | −0.41 | −0.36 |

| ADLBD | 0.3783 | 2.333 | −3.083 | −0.88 | −0.76 |

P<0.01

= Significant difference between pure AD & ADV

=Significant difference between pure AD & ADLBD

=Significant difference between ADV & ADLBD

Figure 3.

Slope of CDR-G across patient ages by visit time

Severity of AD neuropathology across groups

The pAD had a mean Braak stage of 5.4 compared to ADV of 4.7 and ADLBD of 4.6 (P < 0.001, Tukey-Kramer adjusted pairwise comparisons). This was noted even after adjusting for final MMSE scores and education. The pAD group also had concomitantly higher mean neuritic plaque and diffuse plaque burden than the ADV group.

(Table 4)

Table 4.

Neuropathology Variables and duration of symptoms, Mean and Std Dev

P<0.05

1= Significant difference between pure AD & ADV

2=Significant difference between pure AD & ADLBD

3=Significant difference between ADV & ADLBD

N = number of unique patients in duration of symptoms analysis as some subjects had missing data

| Duration of Symptoms, Yrs | Braak stage | Diffuse Plaque | Neuritic Plaques | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pure AD N=82 |

8.46(3.4) | 5.4(0.81)1,2 | 1.2(0.39)1 | 1.3(0.50)1 |

|

ADV N=48 |

7.7(3.5) | 4.7(0.95)1 | 1.5(0.87)1 | 1.7(0.99)1 |

|

ADLBD N=29 |

8.1(2.8) | 4.6(1.02)2 | 1.3(0.65) | 1.5(0.72) |

NACC staging for neuritic and diffuse plaques

= Frequent neuritic/diffuse plaques

= Moderate neuritic/diffuse plaques

= Sparse neuritic/diffuse plaques

= No neuritic/diffuse plaques

Discussion

This study of a large autopsy sample of prospectively characterized subjects, examined conversion of subjects from a pre-dementia state to dementia. In this sample, ADV were significantly older than both pAD and ADLBV. However, even when controlling for age, we found that the pAD group had a more rapid rate of cognitive and functional decline and, not surprisingly, more severe functional and cognitive deficits before death than ADV. There were no significant differences found between pAD and ADLBD. Contrary to our initial hypotheses, MD was not associated with higher odds of dementia before death nor a faster rate of cognitive or functional decline.

At autopsy, the pAD subjects had a higher mean Braak stage and plaque count than ADV, after controlling for age, sex, education and APOE ε4 status and despite similar dementia duration. It is notable that this result was found even after controlling for APOE ε4 status, as APOEε4 carriers have been reported to accumulate amyloid at an earlier age and a faster rate than APOE4 noncarriers [36]. These results could be accounted for by the AD neuropathology accruing more rapidly in the pAD group, accounting for the more rapid rate of decline and greater severity of cognitive and functional deficits at final visit before death. This might also indicate that AD pathology among the older ADV group is less aggressive. Alternatively, ADV subjects could a have lower mean Braak stage and plaque counts at initial cognitive symptoms due to coexistent vascular pathology contributing to their cognitive impairment [12,13]. As a previous report among subjects who exhibited silent infarcts on brain magnetic resonance imaging reported a greater risk of developing dementia than those without these lesions [37], our results could also reflect a silent preclinical AD stage in the younger pAD subjects and a silent preclinical stage from vascular pathology among older ADV subjects.

In our analysis cohort, 94% of ADLBD subjects had either diffuse (neocortical) or intermediate (limbic) distribution of Lewy body pathology. Our results, comparing pAD and ADLBD found no significant difference in the functional rate of decline or the probability of developing dementia prior to death. The groups also had similar age of onset of symptoms and death and similar mean disease durations. The ADLBD group had a faster rate of decline on the CDR-G, CDR-SB and MMSE compared to ADV group despite similar Braak stage AD pathology. This difference between the ADV and mixed ADLBD group suggests that Lewy body pathology, in the context of AD, may be a marker for a more aggressive form of MD. These results are similar to the reports from non-demented elders with AD and Lewy body co-pathology in the Rush Memory and Aging project and Religious Orders Study, which noted that neocortical Lewy bodies were associated with a faster rate of decline (unlike the case for co-occurring vascular pathology)[20].

There are several weaknesses to this analysis. Any multi-site study will have variability in assessments between sites. Seventy-five percent of ADV subjects in our cohort had one or more of large infarcts, microinfarcts, hemorrhages, and lacunes (Supplemental table 1 and 2), but systematic assessment of a known dementia-associated vascular pathology, microinfarcts, was not performed consistently across sites. In many longitudinal neurodegenerative cohorts, including the NACC, there is a selection bias as subjects with large hemispheric infarcts or a high burden of early onset vascular cognitive deficits would not have been enrolled. We should therefore consider the possibility that the rate of functional decline might have been higher among younger onset ADV subjects with more severe vascular co-pathology than that reported in the NACC data. The differences in the results noted between early [10–15] and later MD reports [16–18] could also be due to similar differences in the cohorts and inclusion/exclusion and diagnostic criteria. Additional biases can enter in a multicenter autopsy study: a) differences among neuropathology analysis across centers, b) evolution in diagnostic criteria and lack of uniform assessment of the vascular burden and LBD, c) the likelihood of bias against subjects with rapid decline from AD, LBD or vascular pathology, and/or d) limited neuropathology characterization of the severity of vascular and Lewy body pathology.

Despite the limitations noted above, these results are consistent with the findings from the Religious Orders Study where vascular co-pathology did not contribute to a worse cognitive and functional outcome than when AD pathology was present alone, among non-demented adults, and did not increase the likelihood of dementia beyond their additive effect [15, 20].

Summary

In the NACC longitudinal autopsy cohort, vascular co-pathology did not increase odds of dementia onset and ADV subjects had a slower rate of cognitive and functional decline and less severe deficits than pAD. ADLBD subjects had a faster rate of functional decline and more severe deficits than ADV subjects but not compared to those with pAD. These results suggest that the clinical course of MD is heterogeneous and factors including the nature of co-pathology (vascular vs Lewy body), the type of population cohort (with varying severity of vascular and medical co-morbidities), neuropsychology profile [38]and age of subjects need to be considered in the clinical prognosis of AD and MD subjects and in designing interventions. This study also provides an impetus to better understand the biological and environmental factors mediating interaction between AD, vascular, and LBD pathologies impacting functional decline.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI David Teplow, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), and P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD)

JP has the following disclosures: Grant support from Alzheimer’s Association

Dr. Leverenz has the following disclosures: Consulting fees from Axovant, GE Healthcare, Navidea Biopharmaceuticals, Piramal Healthcare, Teva. Grant support from Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundataion, Axovant, Genzyme/Sanofi. Lundbeck, Michael J Fox Foundation, National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

ABJ and RB have no disclosures

References

- 1.Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, et al. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The Nun Study. JAMA. 1997;277:813–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White L, Petrovitch H, Hardman J, et al. Cerebrovascular pathology and dementia in autopsied Honolulu-Asia Aging Study participants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuropathology Group of the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Aging Study (MRC CFAS) Pathologic correlates of late onset dementia in a multicentre, community based population in England and Wales. Lancet. 2001;357:169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007 Dec 11;69(24):2197–204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker WW, Luis CA, Kashuba A, Luis M, Harwood DG, Loewenstein D, Waters C, Jimison P, Shepherd E, Sevush S, Graff-Radford N, Newland D, Todd M, Miller B, Gold M, Heilman K, Doty L, Goodman I, Robinson B, Pearl G, Dickson D, Duara R. Relative frequencies of Alzheimer disease, Lewy body, vascular and frontotemporal dementia, and hippocampal sclerosis in the State of Florida Brain Bank. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002 Oct-Dec;16(4):203–12. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200210000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jellinger KA, Attems J. Neuropathological evaluation of mixed dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2007 Jun;15(257):1–2. 80–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovacs GG, Milenkovic I, Wohrer A, Hoftberger R, Gelpi E, Haberler C, Hönigschnabl S, Reiner-Concin A, Heinzl H, Jungwirth S, Krampla W, Fischer P, Budka H. Non-Alzheimer neurodegenerative pathologies and their combinations are more frequent than commonly believed in the elderly brain: a community-based autopsy series. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:365–384. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1157-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahimi J, Kovacs GG. Prevalence of mixed pathologies in the aging brain. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014 Nov 21;6(9):82. doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0082-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2009 Aug;66(2):200–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markesbery WR. Comments on vascular dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1991;5(2):149–53. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199100520-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of AD. The Nun Study. JAMA. 1997;277:813–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riekse RG, Leverenz JB, McCormick W, Bowen JD, Teri L, Nochlin D, Simpson K, Eugenio C, Larson EB, Tsuang D. Effect of vascular lesions on cognition in Alzheimer’s disease: a community-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Sep;52(9):1442–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esiri MM, Nagy Z, Smith MZ, Barnetson L, Smith AD. Cerebrovascular disease and threshold for dementia in the early stages of AD. Lancet. 1999;354:919–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mungas D, Reed BR, Ellis WG, Jagust WJ. The effects of age on rate of progression of Alzheimer disease and dementia with associated cerebrovascular disease. Arch Neurol. 2001 Aug;58(8):1243–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.8.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Cerebral infarctions and the likelihood of dementia from Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2004 Apr 13;62(7):1148–55. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118211.78503.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo RY, Jagust WJ, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Vascular burden and Alzheimer disease pathologic progression. Neurology. 2012 Sep 25;79(13):1349–55. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826c1b9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villeneuve S, Reed BR, Madison CM, Wirth M, Marchant NL, Kriger S, Mack WJ, Sanossian N, DeCarli C, Chui HC, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ. Vascular risk and Aβ interact to reduce cortical thickness in AD vulnerable brain regions. Neurology. 2014 Jul 1;83(1):40–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vemuri P, Lesnick TG, Przybelski SA, Knopman DS, Preboske GM, Kantarci K, Raman MR, Machulda MM, Mielke MM, Lowe VJ, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Rocca WA, Roberts RO, Petersen RC, Jack CR., Jr Vascular and amyloid pathologies are independent predictors of cognitive decline in normal elderly. Brain. 2015 Mar;138(Pt 3):761–71. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chui HC, Zheng L, Reed BR, Vinters HV, Mack WJ. Vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease: are these risk factors for plaques and tangles or for concomitant vascular pathology that increases the likelihood of dementia? An evidence-based review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012 Jan 4;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/alzrt98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyle PA, Yu L, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Relation of neuropathology with cognitive decline among older persons without dementia. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2013;5:50. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00050.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker L, McAleese KE, Thomas AJ, Johnson M, Martin-Ruiz C, Parker C, Colloby SJ, Jellinger K, Attems J. Neuropathologically mixed Alzheimer’s and Lewy body disease: burden of pathological protein aggregates differs between clinical phenotypes. Acta Neuropathol. 2015 May;129(5):729–48. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breitve MH, Chwiszczuk LJ, Hynninen MJ, Rongve A, Brønnick K, Janvin C, Aarsland D. A systematic review of cognitive decline in dementia with Lewy bodies versus Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014 Sep 16;6(5–8):5. doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0053-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olichney JM, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Hofstetter CR, Hansen LA, Katzman R, Thal LJ. Cognitive decline is faster in Lewy body variant than in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51:351–357. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraybill JL, Larson EB, Tsuang DW, Teri L, McCormick WC, Bown JD, et al. Cognitive Differences in dementia patients with autopsy-verified AD, Lewy body pathology, or both. Neurology. 2005;64:2069–2073. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000165987.89198.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, Deitrich WD, Jacka ME, Wu J, Hubbard JL, Koepsell TD, Morris JC, Kukull WA, NIA Alzheimer’s Disease Centers The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(3):249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyman Bradley T, et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2012;8:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenowitz WD, Nelson PT, Besser LM, Heller KB, Kukull WA. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and its co-occurrence with Alzheimer’s disease and other cerebrovascular neuropathologic changes. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;(10):2702–2708. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo Ferris S, Graff-Radford NR, Chui H, Cummings J, DeCarli C, Foster NL, Galasko D, Peskind E, Dietrich W, Beekly DL, Kukull WA, Morris JC, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): The neuropsychologic test battery. Alz Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(2):91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wechsler D. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of Health and Human Services. Army Individual Test Battery. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larson David. Analysis of Variance With Just Summary Statistics as Input. The American Statistician. 1992 May;46(2) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jack CR, Jr, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Vemuri P, Mielke MM, Lowe V, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Machulda MM, Gregg BE, Pankratz VS, Rocca WA, Petersen RC. Age, Sex, and APOE ε4 Effects on Memory, Brain Structure, and β-Amyloid Across the Adult Life Span. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(5):511–519. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vermeer SE, Prins ND, den Heijer T, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1215–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pillai JA, Bonner-Jackson A, Walker E, Mourany L, Cummings JL. Higher working memory predicts slower functional decline in autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;38(3–4):224–33. doi: 10.1159/000362715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.