Abstract

Background

Patients often ask oncologists how long a cancer has been present before causing symptoms or spreading to other organs. The evolutionary trajectory of cancers can be defined using phylogenetic approaches but lack of chronological references makes dating the exact onset of tumours very challenging.

Patients and methods

Here, we describe the case of a colorectal cancer (CRC) patient presenting with synchronous lung metastasis and metachronous thyroid, chest wall and urinary tract metastases over the course of 5 years. The chest wall metastasis was caused by needle tract seeding, implying a known time of onset. Using whole genome sequencing data from primary and metastatic sites we inferred the complete chronology of the cancer by exploiting the time of needle tract seeding as an in vivo ‘stopwatch’. This approach allowed us to follow the progression of the disease back in time, dating each ancestral node of the phylogenetic tree in the past history of the tumour. We used a Bayesian phylogenomic approach, which accounts for possible dynamic changes in mutational rate, to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree and effectively ‘carbon date’ the malignant progression.

Results

The primary colon cancer emerged between 5 and 8 years before the clinical diagnosis. The primary tumour metastasized to the lung and the thyroid within a year from its onset. The thyroid lesion presented as a tumour-to-tumour deposit within a benign Hurthle adenoma. Despite rapid metastatic progression from the primary tumour, the patient showed an indolent disease course. Primary cancer and metastases were microsatellite stable and displayed low chromosomal instability. Neo-antigen analysis suggested minimal immunogenicity.

Conclusion

Our data provide the first in vivo experimental evidence documenting the timing of metastatic progression in CRC and suggest that genomic instability might be more important than the metastatic potential of the primary cancer in dictating CRC fate.

Keywords: metastatic colorectal carcinoma, cancer evolution, synchronous metastases, phylogenetic tree, mutational analysis, whole genome sequencing

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cancer in Europe and the USA [1]. Synchronous and metachronous metastases contribute to the high mortality of CRC [2] and, despite improvements in the management of metastatic CRC, 5-year mortality remains up to 50% [1, 3, 4] with a worse outcome for synchronous versus metachronous metastasis (5-year relative survival 7.2% versus 17.6%) [2]. Discussion around the optimal management of synchronous metastasis from CRC is still open but it is reasonable to hypothesize that the difference in outcome between synchronous and metachronous metastases may not be entirely attributable to clinical variables. International large-scale sequencing efforts will likely identify cancer pathways associated with the molecular makeup of synchronous and metachronous metastatic spread. Critical questions remain open: what is the chronological evolution of a synchronously presenting metastatic CRC? Can we tailor screening and follow-up strategies according to the expected pattern of metastatic progression?

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of distinct metastases allows reconstruction of cancer evolutionary trees but the lack of defined temporal milestones limits the ability to infer the exact timing of cancer progression.

Needle tract seeding is a rare but well-documented phenomenon after diagnostic core needle biopsies and causes metastatic growth of the cancer along the needle tract [5]. Here, we carried out WGS of primary and multiple metastatic sites of a CRC patient who developed an iatrogenic metastasis due to needle tract seeding. Exploiting the mutational load of this metastasis along with the exact timing of its onset, we calculated the chronology of the primary CRC and metastatic sites.

Methods

Ethical approval

Formalin fixed paraffin embedded material was acquired under the diagnostic samples/pathology archives surplus to clinical requirements protocol at NHS Ayrshire and Arran. The patient provided full written informed consent for the analyses as detailed, and for the case to be published.

Next-generation sequencing, phylogenetic reconstruction and neo-antigen load

Targeted exome sequencing was carried out in all samples using the Comprehensive Cancer Panel (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) that detects mutations in 409 cancer-related genes. WGS was carried out at 30× depth of coverage on all the samples with the exception of the urinary tract metastasis, which was excluded from this analysis due to low tumour content. Phylogenetic analysis and modelling of adjustment in mutational rate was carried out using Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulations. For neo-antigen analysis, we considered variants in the colon primary tumour, in the lung and thyroid metastases and in the Hurthle adenoma. Somatic variants were called with the same Mutect2-Platypus protocol used for the phylogenetic analysis.

The full method list can be found online in the supplementary material.

Results

Needle tract seeding as stopwatch to calibrate cancer evolution

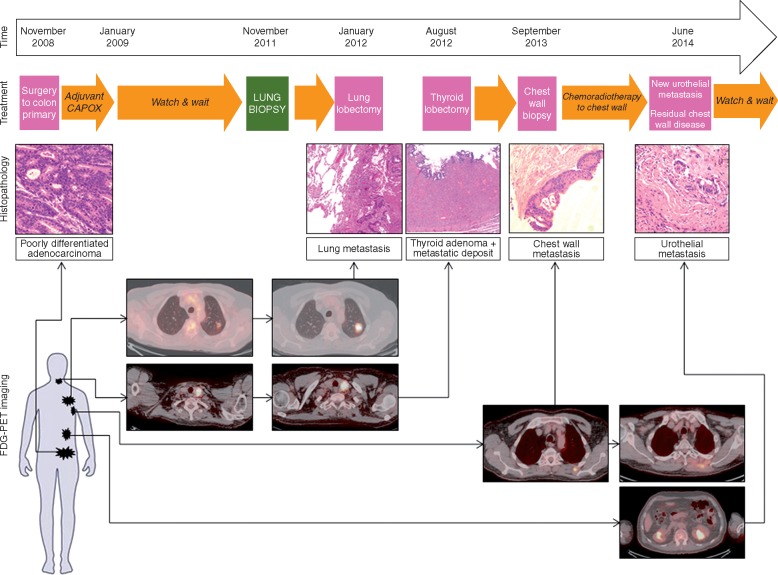

In November 2008 a 68-year-old Caucasian male underwent anterior resection for a pT3pN2(4/17) EMVI negative, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon. Pre-operative staging revealed a solitary left upper lobe lung lesion of uncertain significance, which was kept under active radiological surveillance for nearly 3 years and remained stable (Figure 1; supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

Overview of clinical, radiological and pathological progression of a CRC patient. The patient underwent anterior resection for a pT4pN2 sigmoid cancer in November 2008. A lung nodule of unknown significance at the time of diagnosis was kept under surveillance and was subsequently proved to be metastatic in nature (biopsy in November 2011) and was resected in January 2012. An FDG-avid thyroid nodule was resected in August 2012 and showed a Hurthle adenoma containing foci of metastatic CRC. Two years after the lung biopsy, a chest wall mass on the site of previous lung biopsy was histologically confirmed and treated with chemo-radiotherapy. Six months after treatment the chest wall metastasis showed disease progression and a new site of metastasis along the left ureter was histologically confirmed during the insertion of a urinary stent. The timeline shows the dates that metastatic sites became apparent on imaging. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining as well as FDG-PET-CT images of primary and metastatic sites are shown.

Repeat imaging in July 2011 demonstrated an increase in size of the left upper lobe lung lesion in addition to a new nodule in the left lobe of the thyroid. CT-guided lung biopsy (November 2011) confirmed metastatic colorectal carcinoma with supportive immunohistochemical staining reaction: positive for CK20, CDX2 and CEA but negative for TTF-1 (Figures 1, 2A and B). The patient proceeded to left upper video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy in January 2012. Left thyroid lobectomy (August 2012) demonstrated a follicular Hurthle cell adenoma of the thyroid, within which there was a single tumour-to-tumour deposit of metastatic CRC (Figures 1, 2A and C). The patient underwent periodic follow-up with tumour markers and imaging thereafter and remained disease-free.

Figure 2.

Histopathology and molecular profiling of the primary CRC and metastatic sites. (A) Microscopy of the primary and metastatic sites including H&E staining, proliferation (nuclear Ki-67) and apoptosis (Caspase-3). (B) Microscopy of the CRC lung metastasis that led to the needle tract seeding to the chest wall. Cells stained negative for TTF1 and positive for CDK20, CDX2 and CEA. (C) Gross pathology and microscopy of the Hurthle adenoma containing a CRC metastasis. Macroscopic examination showed the Hurthle adenoma containing a haemorrhagic or cystic area. Different magnifications show the Hurthle adenomatous cells (background large eosinophilic cells) with an invasive front of CRC metastasis. The dotted line indicates the border between the normal thyroid and the Hurthle adenoma. The black rectangle indicates the area of invasive CRC within the adenoma. (D) Microscopy of the urothelial metastasis. H&E and CDK20 staining confirmed the colonic origin of the metastasis. (E) Drivers of CRC detected by WGS and validated by targeted exome sequencing. (F) Copy number changes in primary and metastatic sites.

In September 2013, 5 years from the initial diagnosis, FDG-PET-CT demonstrated a focal unresectable left posterior chest wall mass at the site of previous lung biopsy; histology confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma from the sigmoid primary in keeping with seeding of malignant cells from the needle biopsy carried out 2 years before. Radical chemo-radiotherapy to the left posterior chest wall mass was completed in February 2014 but repeat CT in May and August 2014 demonstrated residual disease at this site in addition to a new abnormality in the upper pole of the left kidney. Renal and left ureteric biopsy demonstrated metastatic CRC, with immunohistochemical staining positive for CDX2, CK20, CK7 and BerEP4 (Figures 1, 2A and D; supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) a detailed description of the case can be found in the Supplementary Material. Primary tumour and metastatic deposits showed similar histopathologic characteristics, resembling that of a traditional poorly-differentiated (G3) adenocarcinoma (Figures 1 and 2). No microsatellite instability (MSI)-like features (i.e. the presence of mucinous and signet ring cells differentiation; medullary growth pattern; presence of tumour intraepithelial lymphocytes; Crohn’s like lymphocytic reaction) were observed.

Genomic profiling

Targeted sequencing of 409 cancer-related genes in both the primary CRC and all metastatic sites (lung, thyroid, chest wall and urinary tract) of our case revealed the presence of clonal non-sense mutations in APC (Gln1367*), as well as missense mutations in CTNNB1 (Leu156Gln), KRAS (Gly12Asp) and TP53 (Ser215Ile) (Figure 2E; supplementary Tables S2 and S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). The same mutations were not detected in the normal tissue or in the Hurthle adenoma (Figure 2E). Two genes included in our panel showed discordance between primary and metastatic cancer: ADAMTS20, a metalloproteinase involved with cancer invasion and migration [6], and AKAP9 an A-kinase anchor protein which binds to the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A [7]. The ADAMTS20 missense mutation Arg1885Thr was observed in the primary cancer but was not detected in either the lung, thyroid or chest wall metastases. Conversely, the AKAP9 missense mutation Ala3077Pro was found in all the metastatic sites but was not detected in the primary cancer. All these mutations were also found using WGS, furthermore ADAMTS20 and AKAP9 were validated by Sanger Sequencing (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). All lesions were microsatellite stable (MSS) [8]. Copy number analysis based on WGS data revealed a relative low level of chromosomal instability (CIN), with LOH of chromosome (chr) 5, gain of chr7, and a focal amplification on chr13q12.2-12.3, encompassing the VEGFR1 [9] and CDX2 [10] genes (Figure 2F; supplementary Figure S3 and Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). These aberrations were clonal in all the CRC lesions, whereas the Hurthle adenoma showed a distinct profile characterized only by loss of chr2, chr9, and chr22. Primary tumour and metastatic sites displayed the same dominant, age related, mutational signature 1 which has previously observed in CRC as well as other cancer types [11] (supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Timing progression

Phylogenetic reconstruction from multiple samples of the same malignancy allows us to turn static snapshots of cancer genomes into the tumour evolutionary history by exploiting genomic intra-tumour heterogeneity [12]. However, although phylogenetic trees inform on the relationship between different samples, estimating the exact chronology of the events without a temporal reference remains extremely challenging.

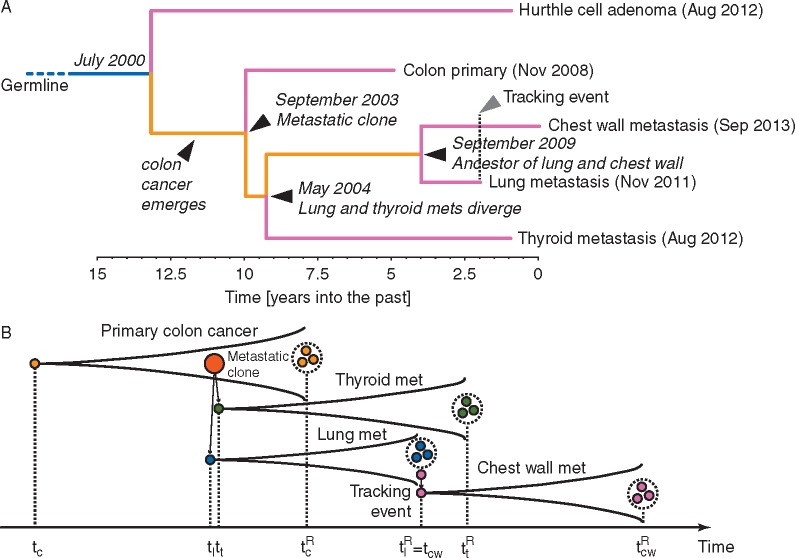

In this exceptional case, the temporal reference is given by the date of seeding along the needle tract that initiated the chest wall metastasis. This information allowed ‘calibration’ of the timing for the whole tree and allowed us to reconstruct the progression of the disease back in time, dating each ancestral node in the past history of the tumour.

The phylogenetic tree was inferred using a Maximum Likelihood approach and timed using a Bayesian phylogenomics framework, accounting for possible dynamic changes in mutational rate, to effectively ‘carbon date’ the malignant progression and reveal the complete chronology of the different lesions in this patient (Figure 3A; see supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online for the list of mutations used to infer the phylogeny). In the field of evolutionary biology, this type of approach is widely used to time the onset of new species by exploiting temporal information from the fossil record [13].

Figure 3.

Chronology of the patient’s CRC evolution. (A) Whole-genome sequencing of multiple lesions from the patient’s malignancy allowed phylogenetic reconstruction of the tumour tree. In the phylogenetic tree, dates within brackets indicate the time of clinical diagnosis whereas dates in italic highlight the estimated times of the different lesions. (B) Illustrative cartoon of the patient disease progression and samples taken. At time the first colorectal cancer cell arose, giving rise to the primary tumour. At time the first metastatic clone emerged, giving rise to the lung metastasis, quickly followed by a second metastasis to the thyroid emerging at time . At time the sample from the primary tumour was collected (resection) and analysed. During the lung biopsy, the needle tract seeding event spread cancer cells in the chest wall at time . A few weeks later, at time the lung metastasis was resected and profiled. Finally at time the chest wall metastasis was also sampled.

By considering the time of chest wall metastasis biopsy as time zero (September 2013) and the node between the chest wall biopsy and the lung biopsy (needle-tract seeding event) as a reference, we estimated that metastatic disease originated 9.26 years before, giving rise to the lung and thyroid metastases in parallel. The primary cancer instead originated between 9.96 and 13.17 years before (Figure 3A and B; supplementary Figure S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). Hence, the primary adenocarcinoma emerged between 5 and 8 years before clinical diagnosis (2000–2003). Despite the long latency between biological onset of the primary cancer and clinical presentation, within just 1 year from its inception the tumour began metastasizing to the lung and to the thyroid where the metastasis grew within a Hurthle adenoma. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the lung and thyroid metastasis were more closely related to one another than to the primary tumour. A schematic representation of the timeline of malignant progression is reported in Figure 3B.

Neo-antigen load

In order to test the contribution of anti-tumour immunity in regulating CRC evolution we applied the pipeline described in supplementary Figure S6, available at Annals of Oncology online (see also supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online) to the samples subjected to multi-region WGS. The analysis resulted in a low number of predicted strong human leukocyte antigen binders [(Colon= 51; Thyroid Metastasis = 5 and Lung Metastasis = 7), supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online].

Discussion

Several studies have applied mathematical modelling to calculate the time-lapse between the onset of primary and metastatic spread [14, 15]. CRC modelling suggests that metastases can develop in less than 2 years from the primary cancer [15]. However, these types of analysis remain difficult to interpret and hard to generalise due to the lack of temporal references. Here, we exploited the occurrence of a needle tract metastasis to define the exact chronology of primary onset and metastatic spread. Our observations suggest that this process might be faster than expected, occurring within the initial 12 months from the primary onset. Similar patterns of early metastatic divergence have been reported in other tumour types using an analogous phylogenomic approach, where in the case of metachronous lesions, the time between primary and metastatic resection was used as a reference [16].

Despite rapid metastatic transformation, our patient showed an indolent course of disease. How can we explain the discordance between the early metastatic dissemination and a relatively favourable prognosis in a patient with synchronous metastasis? The pattern of disease progression we observed is quite uncommon for a CRC patient but, in our opinion, does not account for the favourable outcome. Solitary lung metastases are observed in 11% of colon cancer patients; surgical resection can be curative in some cases but prognosis remains modest [17]. Thyroid and urinary tract metastasis are uncommon and are usually associated with poor prognosis and multi-metastatic disease. CRC metastases to a thyroid adenoma (tumour-to-tumour metastasis) are even less frequent and have always been associated with poor outcome [18]. Although the resection of both lung and the thyroid metastases might have contributed to the improved survival of our patient, the analysis of his molecular makeup suggests that a rather unusual pattern of low genomic instability may have contributed to the indolent course of disease.

In keeping with previous evidence from large-scale genomic studies [19], targeted sequencing showed clonal mutations in genes accounting for the ‘breakthrough’ and ‘expansion’ phase of the primary CRC [20] such as APC, CTNNB1, KRAS and TP53. As expected, all these mutations were also detected in metastatic sites. In contrast, discrepancies between the primary and metastatic sites were observed for ADAMTS20 and AKAP9. In line with our observation, ADAMTS20 mutations were detected in a large series of primary CRC but not in their matching synchronous metastasis [6] suggesting this mutation might promote invasion of the primary cancer but might not be critical for cell fitness in metastatic sites. The anchor protein-coding gene AKAP9 has also been investigated in CRC and found to be up-regulated in CRC with nodal metastasis [21] suggesting a pro-metastatic role for this gene. The molecular pathology of our patient appears common to many other sporadic CRCs. Although the clonal or private mutations described above may have allowed our patient’s cancer cells to metastasise and survive in different environments, this does not explain the slow pattern of progression, suggesting the reason for our patient’s indolent disease may lie elsewhere.

MSI and CIN can be used to classify CRCs with different molecular and prognostic features [22]. Interestingly our patient showed no MSI and relatively few and clonal chromosomal aberrations, with a focal amplification in 13p12.2-12.3 encompassing the VEGFR2 and CDX2 loci, genes previously found over-expressed in synchronous versus metachronous metastatic CRC [23]. Different lines of evidence suggest that high CIN occurring at early stages of neoplastic transformation might represent a hallmark of aggressive behaviour [24, 25] thus the lack of it might explain the indolent course of disease observed in our patient.

A final interesting point relates to the contribution of the tumour microenvironment to CRC evolution: low neo-antigen burden has been associated with worse prognosis in early-stage lung cancer [26]. In our case, the primary cancer displayed low number of neo-antigens and the lack of anti-tumour immunity against the primary cancer might explain the early metastatic spread.

Genomic instability [25] and tumour–stroma interactions [27] represent synergic drivers of cancer progression. The genomic data suggest that in this patient these two hallmarks of cancer evolution might have been uncoupled: while the lack of immune surveillance against the primary tumour might have promoted early cancer metastasis, the relative stability in genomic aberrations might account for the slow rate of progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the NIHR BRC at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and The Institute of Cancer Research.

We thank the patient and his family.

Funding

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK (CEA A18052), European Union FP7 (CIG 334261) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and The Institute of Cancer Research (grants A62, A100, A101, and A159) to NV; Italian Cancer Genome Project – Ministry of University [FIRB RBAP10AHJB]; Associazione Italiana Ricerca Cancro [AIRC 12182] to AScarpa; Wellcome Trust [105104/Z/14/Z] to the Centre for Evolution and Cancer. AS is supported by The Chris Rokos Fellowship in Evolution and Cancer. BW is supported by the Geoffrey W Lewis Post-Doctoral Training fellowship.

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Nordlinger B. et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(Suppl 3): iii1–iii9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ghiringhelli F, Hennequin A, Drouillard A. et al. Epidemiology and prognosis of synchronous and metachronous colon cancer metastases: a French population-based study. Dig Liver Dis 2014; 46: 854–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khan K, Wale A, Brown G, Chau I.. Colorectal cancer with liver metastases: neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection first or palliation alone? World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 12391–12406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moorcraft SY, Smyth EC, Cunningham D.. The role of personalized medicine in metastatic colorectal cancer: an evolving landscape. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2013; 6: 381–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tyagi R, Dey P.. Needle tract seeding: an avoidable complication. Diagn Cytopathol 2014; 42: 636–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim R, Schell MJ, Teer JK. et al. Co-evolution of somatic variation in primary and metastatic colorectal cancer may expand biopsy indications in the molecular era. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0126670.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Onken MD, Winkler AE, Kanchi KL. et al. A surprising cross-species conservation in the genomic landscape of mouse and human oral cancer identifies a transcriptional signature predicting metastatic disease. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 2873–2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Niu B, Ye K, Zhang Q. et al. MSIsensor: microsatellite instability detection using paired tumor-normal sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 1015–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2039–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salari K, Spulak ME, Cuff J. et al. CDX2 is an amplified lineage-survival oncogene in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: E3196–E3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013; 500: 415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Andor N, Graham TA, Jansen M. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of the extent and consequences of intratumor heterogeneity. Nat Med 2016; 22: 105–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dos Reis M, Donoghue PC, Yang Z.. Bayesian molecular clock dating of species divergences in the genomics era. Nat Rev Genet 2016; 17: 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I. et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2010; 467: 1114–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones S, Chen WD, Parmigiani G. et al. Comparative lesion sequencing provides insights into tumor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 4283–4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao ZM, Zhao B, Bai Y. et al. Early and multiple origins of metastatic lineages within primary tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113: 2140–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mitry E, Guiu B, Cosconea S. et al. Epidemiology, management and prognosis of colorectal cancer with lung metastases: a 30-year population-based study. Gut 2010; 59: 1383–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Witt RL. Colonic adenocarcinoma metastatic to thyroid Hurthle cell carcinoma presenting with airway obstruction. Del Med J 2003; 75: 285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012; 487: 330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW.. The path to cancer – three strikes and you're out. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1895–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang MH, Hu ZY, Xu C. et al. MALAT1 promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation/migration/invasion via PRKA kinase anchor protein 9. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015; 1852: 166–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP.. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2014; 383: 1490–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pantaleo MA, Astolfi A, Nannini M. et al. Gene expression profiling of liver metastases from colorectal cancer as potential basis for treatment choice. Br J Cancer 2008; 99: 1729–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burrell RA, McClelland SE, Endesfelder D. et al. Replication stress links structural and numerical cancer chromosomal instability. Nature 2013; 494: 492–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Turajlic S, Swanton C.. Metastasis as an evolutionary process. Science 2016; 352: 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McGranahan N, Furness AJ, Rosenthal R. et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 2016; 351: 1463–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Colvin H, Mori M.. Colorectal cancer: back to the stroma–the real villain in colorectal cancer?. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12: 256–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.