Abstract

Background

Despite the availability of effective antiemetics and evidence-based guidelines, up to 40% of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy fail to achieve complete nausea and vomiting control. In addition to type of chemotherapy, several patient-related risk factors for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) have been identified. To incorporate these factors into the optimal selection of prophylactic antiemetics, a repeated measures cycle-based model to predict the risk of ≥ grade 2 CINV (≥2 vomiting episodes or a decrease in oral intake due to nausea) from days 0 to 5 post-chemotherapy was developed.

Patients and methods

Data from 1198 patients enrolled in one of the five non-interventional CINV prospective studies were pooled. Generalized estimating equations were used in a backwards elimination process with the P-value set at <0.05 to identify the relevant predictive factors. A risk scoring algorithm (range 0–32) was then derived from the final model coefficients. Finally, a receiver-operating characteristic curve (ROCC) analysis was done to measure the predictive accuracy of the scoring algorithm.

Results

Over 4197 chemotherapy cycles, 42.2% of patients experienced ≥grade 2 CINV. Eight risk factors were identified: patient age <60 years, the first two cycles of chemotherapy, anticipatory nausea and vomiting, history of morning sickness, hours of sleep the night before chemotherapy, CINV in the prior cycle, patient self-medication with non-prescribed treatments, and the use of platinum or anthracycline-based regimens. The ROC analysis indicated good predictive accuracy with an area-under-the-curve of 0.69 (95% CI: 0.67–0.70). Before to each cycle of therapy, patients with risk scores ≥16 units would be considered at high risk for developing ≥grade 2 CINV.

Conclusions

The clinical application of this prediction tool will be an important source of individual patient risk information for the oncology clinician and may enhance patient care by optimizing the use of the antiemetics in a proactive manner.

Keywords: emesis, nausea, risk, prediction, cancer, CINV

Introduction

Despite important advances in new and effective preventative antiemetics, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) remains among the most unpleasant and feared side effects of cancer chemotherapy [1, 2]. Uncontrolled CINV also has a negative impact on several dimensions of patient quality of life (QOL) [3, 4]. Consequently, and consistent with patient wishes as well as international antiemetic guidelines, clinicians should strive for the complete prevention of CINV [5, 6].

Important progress in CINV control was made with the availability of the serotonin receptor antagonist (RA) class of antiemetics (e.g. ondansetron, granisetron, palonosetron), the neurokinin-1 (NK-1) inhibitors (e.g. aprepitant), the better use of agents such as dexamethasone and olanzapine [7], and through evidence-based antiemetic guidelines developed by the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [6, 8, 9].

These guidelines have been instrumental in establishing and communicating the emetogenicity of various chemotherapeutics used, but fall short at including individual patient factors that are well known to contribute to emetic risk. Important risk factors identified in the literature include anticipatory nausea and vomiting, younger age, chemotherapy type, female sex, history of morning sickness, expectation of vomiting as well as others [10, 11]. In contrast to antiemetic guidelines, recommendations on the use of granulocyte colony stimulating factors do incorporate patient risk factors such as advanced age and performance status into their guidance [12]. To help incorporate patient risk factors into the selection of optimal antiemetic therapy, CINV risk prediction models have been independently developed by two different groups [13–15]. However, each model has limitations, particularly with the small sample size used and limited geographic regions used in their development [16].

To improve upon these initial models, a multinational collaborative effort was undertaken to combine the respective datasets and to develop a repeated measures prediction model that would allow personal CINV risk from days 0 to 5 to be estimated on a cycle-by-cycle basis. The advantage of a repeated measures approach compared with using baseline data alone is that the former allows risk to be continually reassessed following each additional cycle of anticancer therapy. In this study, the development of a cycle-by-cycle prediction model for grade ≥2 CINV [National Cancer Institute - Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE, version 4.3)] using the largest dataset assembled outside of the clinical trial setting is described.

Methods

Selection of study endpoint

The primary endpoint was ≥grade 2 CINV (NCI-CTCAE, v4.3). This endpoint was selected primarily because of the nature of the available data. Specifically, the data source for model development was not randomized registration trials of antiemetics under investigation, where patients are homogeneous and antiemetic regimens are standardized per the study protocol. Thus, patient heterogeneity and differences in antiemetic prophylaxis between patients made it difficult to statistically differentiate patients receiving chemotherapy of low (e.g. paclitaxel), moderate (e.g. epirubicin) and high-emetogenic potential (e.g. cisplatin).

Patients and data collection

Patient data for developing the repeated measures risk model for predicting the risk of ≥grade 2 CINV over the first 5 days were obtained from five prospective studies that were conducted between 2008 and 2015, with one of the studies being a randomized physicians choice trial [13–19]. All studies enrolled patients with solid tumors or lymphoma who were receiving outpatient chemotherapy. CINV outcomes data were prospectively collected over the first 5 days of chemotherapy and for at least the first cycle using standardized patient diaries. Data collection consisted of patient demographics, disease-related information and potential CINV predictive factors such as history of motion sickness, history of morning sickness during a previous pregnancy (if applicable) and volume of patient-reported alcohol consumed per day. Before each cycle of chemotherapy, additional information was collected such as the scheduled antiemetic prophylaxis, the anticancer regimen to be administered, patient’s expectation to develop CINV following chemotherapy, anxiety level before treatment and number of hours slept the night before chemotherapy.

At the beginning of each study, patients were provided with a daily diary or the MASCC Antiemesis Tool (MAT) to record the number of vomiting episodes, the occurrence, intensity and duration of nausea in the first 24 h and from days 2 to 5 following chemotherapy. The MAT also captured the use of non-prescribed drugs at home for emesis control [20]. The NCI-CTCAE (v4.3) was used to capture the grade of nausea and vomiting (grades 0–IV). In addition, the 4-point Likert scale for nausea and vomiting (none versus mild versus moderate versus severe) contained within the NCI-CTCAE was used to determined symptom severity. Patients were contacted by telephone the day after chemotherapy and during days 2–5 to ensure that the diary had been completed accurately. Risk factors and all outcomes data were collected from the first cycle until the completion of chemotherapy where possible.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographic and clinical variables were screened for possible inclusion into the risk prediction model. The dependent variable in the analysis was the development of ≥grade 2 CINV (NCI-CTCAE, v4.3) over the first 5 days following the completion of chemotherapy. To identify the set of factors with the largest potential contribution to CINV, those with a P-value ≤0.25 in a simple logistic regression with the dependent variable were retained for further consideration. This is a recommended approach for removing weak prognostic covariates so that a more manageable set of variables can be submitted to multivariate techniques [21].

Generalized estimating equations (GEE), which adjust for patient clustering by cycle of therapy were then used to determine the final set of risk factors for inclusion into the model [22, 23]. A GEE model was chosen since observations between multiple cycles within the same patient would be expected to violate the independence assumption of standard logistic regression. The set of initially retained risk factors were analyzed in the GEE model. The Likelihood ratio test was then used in a backwards elimination process (P < 0.05 to retain) to select the final set of risk factors for retention into the model. The goodness of fit of the final model was then assessed with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Model calibration was evaluated by estimating a smooth calibration line between the observed and predicted outcomes [24]. The calibration curve would equal one (optimal) if the observed and predicted probabilities agree perfectly.

Nonparametric bootstrapping was then applied to test the internal validity of the final prediction model [25, 26]. Resampled data (1000 iterations) were used to generate bootstrap estimates of the regression coefficients of the multivariable model. The confidence intervals of the regression coefficient estimates from the bootstrap sampling were then compared with the values calculated by the GEE regression analysis.

From the GEE regression statistical outputs, the contribution of the individual CINV risk factor was weighted with the final model coefficients. To simplify calculations using these weights in the risk algorithm, the coefficients were transformed by multiplying each by a constant (derived by trial and error) and then rounding to the nearest unit value. A summary CINV risk score was then assigned to each patient by simply adding up transformed coefficient values (points) for each risk factor they possessed.

The predictive accuracy of the final risk scoring algorithm was then determined by measuring the specificity, sensitivity, and area under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve [27, 28]. Discrimination refers to the ability of a diagnostic test or a predictive tool to accurately identify patients at low and high risk for the event under investigation and is often presented as the area under the ROC curve. A predictive instrument with an ROC of ≥ 0.70 is considered to have good discrimination, and an area of 0.5 is equivalent to a ‘coin toss’ [24]. All the statistical analyses were carried out using Stata, V11.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Sample characteristics

Upon pooling the databases from the individual studies, the final sample size consisted of 1198 patients, who received a total of 4197 cycles of chemotherapy (median 2; range 1–11). The median age of patients was 58 years and 74.6% were female. Approximately 56% of patients had breast cancer, among other major solid organ malignancies (Table 1). The majority of all patients (76%) had early stage disease, 37.5% had a history of morning sickness during a prior pregnancy, and 24.5% reported consuming at least one alcoholic beverage on a daily basis. In addition, 27.9% of patients reported they expected to develop CINV following their treatment. The chemotherapy was platinum or anthracycline-based in 27.2% and 52.8% of patients, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient and treatment characteristics from multiple CINV studies

| Patient characteristic | Total no. of patients = 1198 % of patients (no. of patients) |

|---|---|

| Median patient age (range) | 58 (19–100) |

| Female gender | 74.6% (894) |

| Type of cancer | |

| Breast | 55.5% (665) |

| Gastrointestinal | 14.3% (172) |

| Genitourinary | 1.8% (21) |

| Gynecological | 5.7% (68) |

| Lung | 8.1% (97) |

| Other | 13.2% (158) |

| Missing | 1.4% (17) |

| Early stage (vs. metastatic) | 73.4% (879) |

| History of motion sickness | 26.7% (320) |

| History of morning sickness during a pregnancy | 37.5% (449) |

| Daily alcohol intake | 24.5% (294) |

| Patient/treatment characteristic |

Total no. of cycles = 4197 % of cycles (no. of cycles) |

|---|---|

| Median number of cycles (range) | 2 (1–11) |

| Anticipatory nausea and vomiting | 27.9% (1174) |

| Sleep the night before chemotherapy | |

| <5 h | 12.8% (538) |

| 5–7 h | 56.0% (2351) |

| 8–9 h | 26.8% (1125) |

| Ten hours of more | 2.9% (123) |

| Missing | 1.4% (60) |

| Anxiety before chemotherapy | |

| None | 29.5% (1237) |

| Mild | 21.8% (916) |

| Moderate | 18.1% (760) |

| High | 4.9% (205) |

| Missing | 25.7% (1079) |

| Type of chemotherapy | |

| Platinum based | 27.4% (1151) |

| Anthracycline based | 52.8% (2217) |

| Single agent taxanes | 7.4% (310) |

| Other6 | 12.4%% (519) |

| Pre-chemotherapy anti-emetics | |

| Ondansetron/granisetron alone | 15.5% (652) |

| Dexamethasone ± prochlorperazine | 3.6% (152) |

| Dexamethasone + ondansetron | 56.6% (2377) |

| Ondansetron + aprepitant | 12.2% (510) |

| Ondansetron + aprepitant + dexamethasone | 0.6% (25) |

| Ondansetron + aprepitant + olanzapine + dexamethasone | 2.1% (90) |

| Other1 | 15.5% (652) |

| Post-chemotherapy anti-emetics | |

| None | 4.4% (186) |

| Dexamethasone or ondansetron alone | 23.8% (1001) |

| Dexamethasone + ondansetron | 45.0% (1888) |

| Ondansetron + dexamethasone + aprepitant | 12.2% (510) |

| Ondansetron + aprepitant + olanzapine + | 2.1% (90) |

| Dexamethasone | |

| Othera | 12.4% (519) |

| Missing | 0.07% (3) |

Data sources: See references [10–16].

Did not consist of a 5HT3, dexamethasone or aprepitant.

Before each cycle, ∼81% of patients received a 5-HT3 RA as part of their primary antiemetic prophylaxis (Table 1). Dexamethasone was used for pre-chemotherapy in ∼57% of cycles. The NK-1 RA, aprepitant, was used in only 15% and 14% of cycles pre- and post-chemotherapy, respectively (Table 1). Before the next cycle of chemotherapy, 57.7% of patients reported they had used a non-prescribed treatment at home for CINV control at some point during their chemotherapy. These drugs included dimenhydrinate, Peptobismol®, antacids, cannabis products and herbal supplements.

CINV clinical outcomes

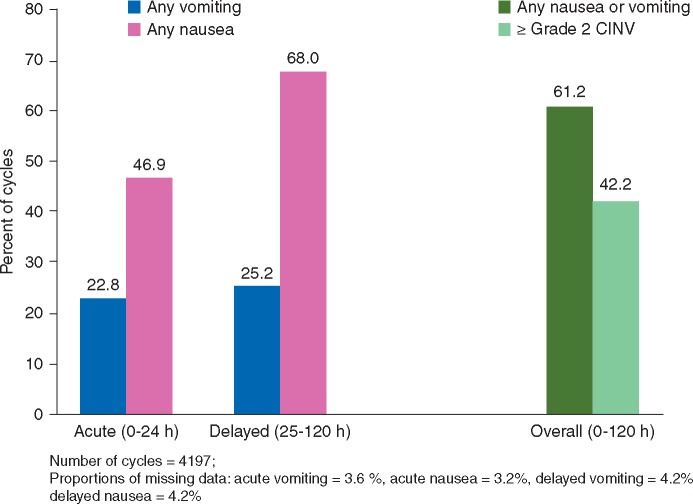

Over 4197 cycles of chemotherapy, 22.8% of patients reported vomiting and 46.9% indicated that they experienced at least some nausea during the first 24 h following the initiation of chemotherapy (Figure 1). From days 2 to 5, the proportion of patients experiencing delayed nausea and vomiting was 68.0% and 25.2%, respectively. When the data were combined from days 0 to 5, CINV was reported in 2567 of 4167 (61.2%) cycles of chemotherapy; ≥grade 2 CINV occurred in 42.2% of cycles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CINV outcomes data.

Development of cycle-based risk prediction model

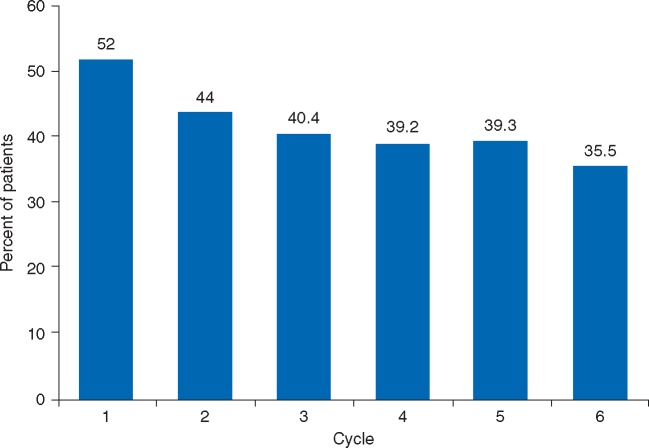

After the initial univariate screening, the potential predictive factors associated with ≥grade 2 CINV were retained for further analysis using multivariable GEE regression analysis through a backwards elimination process with P < 0.05. The final eight variables retained in the model that were considered as significant CINV predictive factors were (i) nausea or vomiting in the prior cycle, (ii) use of non-prescribed antiemetics at home, (iii) platinum or anthracycline-based chemotherapy, (iv) age ≤60 years, (v) anticipatory nausea and vomiting, (vi) <7 h of sleep the night before chemotherapy, (vii) history of morning sickness and (viii) cycle of chemotherapy (Table 2). A negative association between risk and number of cycles was identified where the hazard for CINV was highest in cycles 1 and 2, with a gradual decline and plateau from cycle 3 onward (Figure 2). The confidence intervals of the regression coefficient estimates from the bootstrap sampling were comparable with the values calculated by the GEE regression analysis, supporting the internal validity of the model.

Table 2.

Predictive factors for nausea and vomiting from days 0 to 5

| Predictive factora | Odds ratiob | (95% CI) | Impact on risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age <60 years | 1.41 | (1.12–1.77) | ↑ by 41% |

| Anticipatory nausea and vomiting | 1.41 | (1.13–1.77) | ↑ by 41% |

| Sleep <7 h | 1.34 | (1.10–1.48) | ↑ by 34% |

| History of morning sickness | 1.30 | (1.04–1.64) | ↑ by 30% |

| Use of non-prescribed antiemetics at home | 2.70 | (1.45–2.60) | ↑ 2.7 times |

| Platinum- or anthracycline-based chemotherapy | 1.94 | (1.45–2.60) | ↑ by 94% |

| Nausea or vomiting in the prior cycle | 5.17 | (3.72–7.18) | ↑ 5.17 times |

| Cycle number (vs. cycle 1) | |||

| Cycle 2 | 0.17 | (0.12–0.24) | ↓ by 83% |

| ≥Cycle 3 | 0.15 | (0.10–0.24) | ↓ by 85% |

Dependent variable: ≥grade 2 CINV from days 0 to 5 post-chemotherapy.

These are the final variables that were retained following the application of the Likelihood ratio test (P < 0.05 to retain) in a backwards elimination process.

An odds ratio of less than one means lower risk and greater than one increased risk.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of ≥grade 2 CINV by cycle of chemotherapy.

Development of CINV scoring system

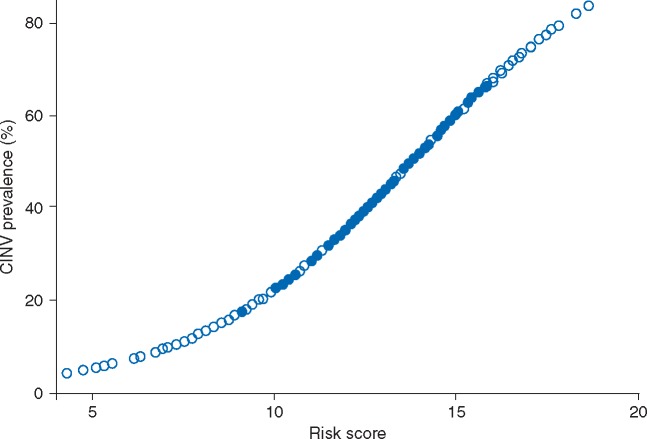

A risk scoring system was then developed from the point estimates of the regression coefficients and the intercept generated from the analysis. Each of the final regression coefficients retained in the model provided a statistical weight for that factor’s contribution to the overall risk of CINV. The scoring system was then adjusted by adding a constant across all scores to ensure that none were below zero. The final product was a scoring system between 0 and 32 where higher scores were associated with an increased risk for ≥grade 2 CINV over the first 5 days of chemotherapy (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

Risk scoring algorithm for ≥grade 2 CINV in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy

| Predictive factor | Before a cycle of chemotherapy |

|---|---|

| Baseline score | 10 |

| Impact of patient risk factors | |

| Patient < age | +1 |

| Patient expects to have CINV | +1 |

| Patient slept <7 h the night before chemotherapy | +1 |

| Patient has a history of morning sickness | +1 |

| Patient is about to receive platinum or anthracycline chemotherapy | +2 |

| Patient on-prescription antiemetics are used at home in the prior cycle | +3 |

| Patient had nausea or vomiting in the prior cycle | +5 |

| About to receive the 2nd cycle | −5 |

| About to receive ≥ 3rd cycle | −6 |

| Total composite risk scorea | ? |

The probability of developing ≥grade 2 CINV during that cycle of therapy can then be estimated from Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Relationship between patient risk score and probability of developing ≥grade 2 CINV.

Factors that elevate the overall score are considered to be positive risk factors for CINV. For instance, one unit would be added to the baseline score of 10 if a patient is <60 years of age (Table 3). In contrast, CINV risk is lower in the second cycle compared with the first cycle of chemotherapy, and this would be reflected by the subtraction of 5 units from the baseline score.

All patients in the sample were then assigned a risk score based on the algorithm (Table 3). The model development was continued with an ROC curve analysis and a measurement of the area under the curve. The findings suggested that the area under the ROC curve was acceptable at 0.69 (95% CI: 0.67–0.70), supporting the predictive accuracy of the scoring algorithm.

The final step in the development of the CINV prediction tool was the identification of a high-risk score threshold or ‘cutoff’, which optimizes sensitivity and specificity. Seven risk score categories were developed and a risk score threshold of ≥16 units was identified as being the point where sensitivity (i.e. the ability to identify true positives) is optimal and keeping in mind the balance between sensitivity and specificity that needs to be made (Table 4). Hence, a risk score threshold of ≥16 would capture patients with a predicted CINV risk of at least 60% before each cycle of chemotherapy (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Detailed analysis of risk scoring system for ≥grade 2 CINV

| Score cut point | Observed prevalencea (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Likelihood ratiob |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <8 | 12.5 | 100 | 0 | 1.0 |

| ≥8 to < 12 | 13.6 | 99.8 | 1.2 | 1.01 |

| ≥12 to < 16 | 23.1 | 97.9 | 10.7 | 1.10 |

| ≥16 to < 20a | 43.7 | 87.4 | 38.4 | 1.42 |

| ≥20 to < 24 | 57.6 | 51.2 | 75.7 | 2.11 |

| ≥24 to < 28 | 72.8 | 18.8 | 94.8 | 3.60 |

| ≥28 | 87.9 | 2.1 | 99.8 | 9.08 |

Patients with a risk score of ≥16 to < 20 had a CINV prevalence of ∼43.7% following that cycle of chemotherapy. Therefore in this analysis, we considered a CINV risk score of ≥16 to be ‘high risk’.

The ratio of the probability of a positive test result, in the case of CINV, a risk score of 16 units or more among patients who actually developed ≥grade 2 CINV to the probability of a positive test result among patients who did not develop such an event. Therefore, patients who developed ≥grade 2 CINV were 1.4 times more likely than patients who did not develop the event to have a risk score of 16 or more.

Notwithstanding, it is important to realize that these risk score thresholds are not fixed and can vary based on the patient or oncologist’s risk tolerance. Some may prefer to select a higher risk threshold before modifying standard antiemetic therapy. A higher risk threshold such as ≥ 20 would have a greater specificity (75.7%), which would minimize the false positive rate (i.e. fewer people would incorrectly receive additional antiemetic prophylaxis). However, using such a threshold would reduce the sensitivity to 51.2%, which would result in missing additional patients (true positives) who develop CINV post-chemotherapy.

Discussion

This paper describes the development of a cycle-by-cycle predictive model and associated scoring algorithm for determining the likelihood of patients experiencing ≥grade 2 CINV using the largest dataset assembled outside of the clinical trial setting. After an initial starting point of 16 potential predictor variables, the final model contained eight variables that were retained by a statistical selection process with P value for retention set at <0.05. The variables identified as being important predictors for CINV included: nausea or vomiting in the prior cycle, use of non-prescribed antiemetics taken at home for CINV control, platinum or anthracycline-based chemotherapy, age ≤60 years, anticipatory nausea and vomiting, <7 h of sleep the night before chemotherapy, history of morning sickness, and the first cycle of chemotherapy, all of which have been reported in literature [10, 11, 14, 15].

Poorly controlled CINV can result in treatment delays, dose reductions, the need for antiemetic rescue therapy, increased health care resource use (e.g. hydration), and even the premature discontinuation of chemotherapy [29]. Therefore, it is important that CINV be managed effectively in the first cycle of chemotherapy because it will almost certainly have a negative impact in CINV outcomes in subsequent cycles. As was demonstrated in one study, CINV risk was increased by at least 6-fold in subsequent cycles if poorly controlled in cycle one [30]. The CINV risk prediction model developed in the current study allows the incorporation of personal risk factors that will identify patients at high risk and ensure they are receiving appropriate prophylaxis. The scoring system has broad applications across oncology practice settings and can discriminate between high and low risk patients. The risk threshold for medical decision-making can also be shifted up or down, depending on a patient’s and/or clinician’s risk tolerance. Such a scoring system can also be incorporated into chemotherapy ordering systems or even delivered through the Internet. Indeed, our group has recently developed a website (http://www.cinvrisk.org) that contains the CINV-risk model and generates an individualized percentage risk estimate by cycle of chemotherapy. The principle behind this website is that clinicians can enter a patient’s risk factors and calculate CINV probability in real time. The primary use of this tool as we see it is to modify current antiemetic prophylaxis in order to avoid unnecessary nausea and vomiting, identify patients who require additional education regarding CINV management, and to monitor current antiemetic protocols.

Despite the potential benefits of the CINV risk model and risk prediction website, there are several limitations in the current study that need to be acknowledged. Even though the sample size was almost 1200 patients who received over 4100 cycles of chemotherapy, the model should undergo external prospective validation on a new sample of patients [31]. The model considered data on only readily measurable variables and did not consider other potentially important predictors. Beyond the personalized risk factors, other predictors may include prescribing (or lack of) within antiemetic guidelines developed by organizations such as MASCC and ESMO as well as pharmacogenomic factors [6]. Hence, not all of the variability was accounted for in our analysis. The area under the ROC curve was estimated to be 0.69 (95% CI: 0.67−0.70). Even though this is deemed to be acceptable, there is opportunity to further improve this model. In addition, the model sensitivity for the suggested risk cut off at ≥16 units was high at 87.4%. However, the specificity at 38.4% was low. Such low specificity would suggest a high rate of false positives; meaning that the model would falsely identify some patients as ‘high risk’ and potentially lead to over treatment of patients at a lower risk for CINV. However, the risk cut off can be adjusted based on a patient’s risk tolerance. External validation of the risk prediction model in a new sample of patients would also improve the specificity.

Despite these limitations, we describe an important step for incorporating individual patient CINV risk factors when selecting antiemetic prophylaxis, which could also be considered by the international guideline development committees. The mathematical algorithm is easy to apply and allows the identification of patients at high risk before each cycle of chemotherapy. The risk prediction website (http://www.cinvrisk.org) will also allow the percentage of CINV risk to be rapidly calculated, ‘just in time’ to modify antiemetic prophylaxis. Therefore, the clinical application of this CINV risk prediction tool will be an important source of patient-specific risk information for the oncology team and may enhance patient care by optimizing the use of the antiemetics in a proactive manner.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from Helsinn Healthcare (no grant numbers apply).

Disclosure

The corresponding author had full access to the data in the study and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit the paper. The co-authors in this manuscript except for Dr Clemons received honoraria for participating in advisory boards undertaken by Helsinn Healthcare.

References

- 1. Kuchuk I, Bouganim N, Beusterien K. et al. Preference weights for chemotherapy side effects from the perspective of women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013; 142: 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sun CC, Bodurka DC, Weaver CB. et al. Rankings and symptom assessments of side effects from chemotherapy: insights from experienced patients with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer 2005; 13: 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee J, Dibble SL, Pickett M, Luce J.. Chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting and functional status in women treated for breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 2005; 28: 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rusthoven JJ, Osoba D, Butts CA. et al. The impact of postchemotherapy nausea and vomiting on quality of life after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 1998; 6: 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hernandez Torres C, Mazzarello S, Ng T. et al. Defining optimal control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting-based on patients' experience. Support Care Cancer 2015; 23: 3341–3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roila F, Molassiotis A, Herrstedt J. et al. 2016 MASCC and ESMO guideline update for the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2016; 27(Suppl 5): v119–v133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Navari RM, Qin R, Ruddy KJ. et al. Olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2016) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Antiemesis. Version 2.2016; https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf (29 December 2016, date last accessed).

- 9. Hesketh PJ, Bohlke K, Lyman GH. et al. Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology Focused Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Molassiotis A, Aapro M, Dicato M. et al. Evaluation of risk factors predicting chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting: results from a European prospective observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 47: 839–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pirri C, Katris P, Trotter J. et al. Risk factors at pretreatment predicting treatment-induced nausea and vomiting in Australian cancer patients: a prospective, longitudinal, observational study. Support Care Cancer 2011; 19: 1549–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith TJ, Khatcheressian J, Lyman GH. et al. 2006 update of recommendations for the use of white blood cell growth factors: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. JCO 2006; 24: 3187–3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Molassiotis A, Stamataki Z, Kontopantelis E.. Development and preliminary validation of a risk prediction model for chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21: 2759–2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dranitsaris G, Joy A, Young S. et al. Identifying patients at high risk for nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy: The development of a practical prediction tool. J Supp Oncol 2009; 7: W1–W8. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petrella T, Clemons M, Joy A. et al. Identifying patients at high risk for nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy: the development of a practical validated prediction tool. J Supp Oncol 2009; 7: W9–W16. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dranitsaris G, Clemons M.. Risk prediction models for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: almost ready for prime time? Support Care Cancer 2014; 22: 863–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bouganim N, Dranitsaris G, Hopkins S. et al. Prospective validation of risk prediction indexes for acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Curr Oncol 2012; 19: e414–e421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dranitsaris G, Bouganim N, Milano C. et al. Prospective validation of a prediction tool for identifying patients at high risk for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Support Oncol 2013; 11: 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clemons M, Bouganim N, Smith S. et al. A randomized trial comparing risk model guided antiemetic prophylaxis to physician’s choice in patients receiving chemotherapy for early stage breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2: 225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Molassiotis A, Coventry PA, Stricker CT. et al. Validation and psychometric assessment of a short clinical scale to measure chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: the MASCC antiemesis tool. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 34: 148–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. George SL. Identification and assessment of prognostic factors. Semin Oncol 1988; 15: 462–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Logistic Regression Using the SAS System: Theory and Application; Chapter 8; pp. 179–216. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.,1999.

- 23. Rabe-Hesketh S, Everitt B, Statistical Analysis using Stata; Chapter 9; p119-136. Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lyman GH, Kuderer NM.. A primer in prognostic and predictive models: development and validation of neutropenia risk models. Support Cancer Ther 2005; 2: 168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ, Harrell FE Jr. et al. Prognostic modeling with logistic regression analysis: in search of sensible strategies in small data sets. Med Decis Making 2001; 21: 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE Jr, Borsboom GJ. et al. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54: 774–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hanley JA, McNeil BJ.. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982; 143: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McNeil BJ, Hanley JA.. Statistical approaches to the analysis of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Med Decis Making 1984; 4: 137–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aapro M, Molassiotis A, Dicato M. et al. The effect of guideline-consistent antiemetic therapy on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Ann Oncol 2012; 23: 1986–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Molassiotis A, Lee PH, Burke TA. et al. Anticipatory nausea, risk factors and its impact on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016; 51: 987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, Royston P, Moons KG.. Prognosis and prognostic research: validating a prognostic model. Br Med J 2009; 338: b605.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]