Abstract

Background

The single-arm, phase II Tasigna Efficacy in Advanced Melanoma (TEAM) trial evaluated the KIT-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor nilotinib in patients with KIT-mutated advanced melanoma without prior KIT inhibitor treatment.

Patients and methods

Forty-two patients with KIT-mutated advanced melanoma were enrolled and treated with nilotinib 400 mg twice daily. TEAM originally included a comparator arm of dacarbazine (DTIC)-treated patients; the design was amended to a single-arm trial due to an observed low number of KIT-mutated melanomas. Thirteen patients were randomized to DTIC before the protocol amendment removing this study arm. The primary endpoint was objective response rate (ORR), determined according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors.

Results

ORR was 26.2% (n = 11/42; 95% CI, 13.9%–42.0%), sufficient to reject the null hypothesis (ORR ≤10%). All observed responses were partial responses (PRs; median response duration, 7.1 months). Twenty patients (47.6%) had stable disease and 10 (23.8%) had progressive disease; 1 (2.4%) response was unknown. Ten of the 11 responding patients had exon 11 mutations, four with an L576P mutation. The median progression-free survival and overall survival were 4.2 and 18.0 months, respectively. Three of the 13 patients on DTIC achieved a PR, and another patient had a PR following switch to nilotinib.

Conclusion

Nilotinib activity in patients with advanced KIT-mutated melanoma was similar to historical data from imatinib-treated patients. DTIC treatment showed potential activity, although the low patient number limits interpretation. Similar to previously reported results with imatinib, nilotinib showed greater activity among patients with an exon 11 mutation, including L576P, suggesting that nilotinib may be an effective treatment option for patients with specific KIT mutations.

Clinical Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01028222.

Keywords: KIT, melanoma, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, nilotinib, dacarbazine, imatinib

Introduction

Mutations in the stem cell factor receptor tyrosine kinase gene (KIT) are observed in ≈2% of all melanomas [1], often leading to upregulated signaling from the corresponding protein KIT. KIT mutations are most common in acral and mucosal melanomas and less often observed in cutaneous melanoma arising from skin with chronic sun damage (CSD) [2]. KIT mutations are widely distributed over the coding region and observed in exons 9, 11, 13, 17, and 18 [2, 3]. Advanced melanomas with KIT aberrations (mutations and/or amplifications) have been shown to respond to the BCR-ABL1/KIT tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib (Gleevec, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation) [4–9], although response rates are low compared with BRAF inhibitors in BRAF-mutated melanomas [10, 11]. Nilotinib (Tasigna, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation) has also demonstrated activity against several known KIT mutations in vitro, with potency comparable to or greater than that of imatinib (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) [12, 13], and is less likely to lead to gastrointestinal or fluid retention-related adverse events (AEs) [14]. Nilotinib has thus been investigated as a potential treatment of KIT-mutated melanomas [15–18]. A phase II study in patients with advanced KIT-mutated melanoma reported partial responses (PRs) in 3 of 19 nilotinib-treated patients (15.8%), including two with prior imatinib resistance. The Tasigna Efficacy in Advanced Melanoma (TEAM; ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01028222) trial was the first open-label, multicenter, single-arm, phase II study to assess the efficacy and safety of nilotinib in patients with KIT-mutated advanced melanoma without prior KIT inhibitor therapy.

Methods

Patients, study design, and treatment

Patients were enrolled at 29 centers in 11 countries (Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the USA). Eligible patients were adults with histologically confirmed unresectable or metastatic acral, mucosal, or CSD melanoma without a history of brain metastases and with a confirmed KIT mutation in exons 9, 11, 13, or 17 (D820G, N822H, N822K, D820Y, Y822D, or Y823D), which have known KIT inhibitor sensitivity [4–6, 13]. Following a protocol amendment, patients with CSD melanoma were excluded from further enrollment because of a low observed KIT mutation rate. Mutation status was determined in a central laboratory (MolecularMD, Portland, OR) by DNA extraction from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue that was macrodissected, followed by polymerase chain reaction amplification and sequencing using a panel of direct sequencing assays with 20% mutant allele sensitivity. Germline DNA was not sequenced to determine whether mutations were somatic.

Patients with KIT amplification without mutation were ineligible. Additional exclusion criteria included prior treatment with any TKI or >1 systemic anticancer therapy for melanoma in addition to any adjuvant therapy. Patients with significantly impaired cardiac function were ineligible, as were those with gastrointestinal impairment, chronic or acute pancreatitis, and/or acute or chronic liver or renal disease unrelated to melanoma.

Originally, the TEAM trial was a randomized, phase III study of nilotinib versus dacarbazine (DTIC; standard of care), with a target enrollment of 120 patients. This was amended to an open-label, single-arm design due to the rarity of patients harboring KIT mutations. Although 13 patients were randomized to DTIC before the protocol amendment and 10 eventually switched to nilotinib, the focus of this analysis is on the patients whose initial treatment was nilotinib. All patients assigned to nilotinib received nilotinib 400 mg twice daily. Dose adjustments were allowed per protocol-specified criteria (supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Study endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint was the objective response rate (ORR), defined as the proportion of patients with a confirmed complete response (CR) or PR determined by the investigator according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST). Tumor progression was assessed by computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging or photography at screening, baseline, weeks 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24, and every 12 weeks thereafter.

Key secondary endpoints included Kaplan–Meier (KM) estimates of progression-free survival (PFS; time from treatment start to date of first documented progression or death) and overall survival (OS; time from study start to date of death from any cause; supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online). Additional secondary endpoints included KM-estimated duration of objective response (DOR; time from first documented CR or PR to first documented progression or death) and disease control rate (DCR; proportion of patients with CR, PR, or stable disease [SD] for ≥12 weeks from start of treatment).

AEs were assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0. Safety was evaluated on an ongoing basis during study treatment and ≤30 days after the last dose of study treatment.

Statistical analyses

Demographics, baseline characteristics, and efficacy analyses were determined in the intent-to-treat population, including all patients assigned to nilotinib. Patients randomized to DTIC before the study design amendment were analyzed separately. Demographics and baseline characteristics were summarized by descriptive statistics. Safety analyses were determined in the safety population, including all patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication.

For the primary endpoint, the null hypothesis (ORR ≤10%) was tested according to Simon’s two-stage design. After all 23 nilotinib-treated patients enrolled in the first stage had a confirmed response, discontinued the study, or completed 24 weeks of treatment, the trial was to be discontinued (null hypothesis accepted) if <3 confirmed responses were observed. If ≥3 confirmed responses were observed, the second stage would begin with an enrollment target of an additional 18 patients. If there were ≥9 responders overall, the null hypothesis would be rejected with a one-sided significance level of 2.5% and a power of 90% against an alternative hypothesis of ORR ≥30%.

Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and local laws/regulations. Patients provided written informed consent before participation. The study protocol and all amendments were reviewed and approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee for each center.

Results

Patients and treatment exposure

Between 29 April 2010 and 23 October 2012, 877 patients were prescreened for KIT mutations. While a mutation frequency of 20%–30% was expected in the target population based on prestudy estimates [2], only 106 (12.1%) prescreened patients harbored KIT mutations (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Of these, 78 were screened for eligibility per additional inclusion/exclusion criteria, and 55 enrolled. Primary reasons for screening failure were unacceptable laboratory or test procedure results (e.g. brain metastasis). Before closure of the DTIC arm (via protocol amendment 27 July 2011), 14 and 13 patients were randomized to nilotinib and DTIC, respectively. Ten patients on DTIC subsequently crossed over to nilotinib; the remaining three discontinued [loss to follow-up, disease progression, administrative problems (n = 1 each)]. Herein, demographic, efficacy, and safety data are reported for patients who initiated nilotinib treatment upon enrollment (N = 42), with brief mention of the DTIC results. Further details regarding efficacy/safety for patients randomized to DTIC are included in the supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online.

In the nilotinib arm, acral and mucosal melanomas were most frequent (n = 20; 47.6% each; information on primary site is in Table 1); two patients (4.8%) had CSD melanoma of the head and neck (patients with CSD melanoma were excluded from the study following a protocol amendment). The most frequently observed KIT mutations were in exon 11 [n = 26; 61.9%; most commonly L576P (n = 10)] and exon 13 (n = 13; 31.0%).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics

| Demographic variables | Nilotinib 400 mg twice daily (N = 42) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), years | 65.5 (20–87) |

| <65 years, n (%) | 20 (47.6) |

| ≥65 years, n (%) | 22 (52.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 19 (45.2) |

| Female | 23 (54.8) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 26 (61.9) |

| Asian | 10 (23.8) |

| Other | 6 (14.3) |

| WHO performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 30 (71.4) |

| 1 | 10 (23.8) |

| 2 | 2 (4.8) |

| Melanoma type and primary site, n (%) | |

| Acral | 20 (47.6) |

| Sole | 8 (19.0) |

| Subungual (hand) | 4 (9.5) |

| Subungual (foot) | 2 (4.8) |

| Othera | 6 (14.3) |

| Mucosal | 20 (47.6) |

| Female genital tract | 9 (21.4) |

| Anorectal | 4 (9.5) |

| Head and neck | 1 (2.4) |

| Otherb | 6 (14.3) |

| CSD | 2 (4.8) |

| Head and neck | 2 (4.8) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, n (%) | |

| Within or below normal range | 30 (71.4) |

| Above normal range | 10 (23.8) |

| Missing | 2 (4.8) |

| Prior systemic anticancer therapies,cn (%) | |

| Any therapy | 13 (31.0) |

| Chemotherapy | 9 (21.4) |

| Immunotherapy | 2 (4.8) |

| Otherd | 6 (14.3) |

| KIT mutation status, n (%) | |

| Exon 11 | 26 (61.9) |

| L576P | 10 (23.8)e |

| V559A | 3 (7.1) |

| V560D | 3 (7.1) |

| W557C | 2 (4.8) |

| W557R | 2 (4.8) |

| Otherf | 6 (14.3) |

| Exon 13 | 13 (31.0) |

| K642E | 10 (23.8) |

| Otherg | 3 (7.1) |

| Exon 9h | 2 (4.8) |

| Exon 17 (Y823D) | 1 (2.4) |

| Time since initial diagnosis, median (range), months | 13.2 (1.6–305.4) |

| Time since most recent recurrence/relapse, median (range), days | 61 (1–761) |

Includes toe (n = 4), heel (n = 1), and thumb (n = 1).

Includes esophagus (n = 3), nasal mucosa (n = 2), and intranasal (n = 1).

Other than therapies received only in the adjuvant setting.

Includes recombinant human endostatin injection (n = 4), bleomycin (n = 1), and sargramostim (n = 1).

Includes 1 patient with a combined L576P/W557R mutation.

Other mutations detected were D572G, K558E, K581_P585dup, V559D, V569I, and W557hetdel (n = 1 each).

Other mutations detected were K642Q, R634W, and V654A (n = 1 each).

Specific mutations were D496N and S476C (n = 1 each).

CSD, chronic sun damage; WHO, World Health Organization.

By study completion (last patient last visit, 31 December 2014), 38 patients (90.5%) had discontinued nilotinib, most commonly for disease progression (n = 33; 86.8%). Known subsequent treatments following study discontinuation included chemotherapy/radiation (n = 18), ipilimumab (n = 15), imatinib (n = 8), and other targeted/immune therapies (n = 7). Four patients (9.5%) remained on nilotinib through a rollover study or local protocol. Median duration of nilotinib exposure was 15.0 weeks (range 1–154 weeks). Dose interruptions due to AEs were reported in 26 patients (61.9%). Twenty-two patients (52.4%) received a reduced dose, with six patients having ≥1 direct dose reduction to 400 mg once daily without prior interruption. The lowest nilotinib dose received was 400 mg daily in 21 patients and 200 mg daily in one patient. The median percentage of days on study that patients received a full nilotinib dose was 75.5% (range, 12%–98%).

Efficacy

Among the 42 patients in the nilotinib arm, the ORR was 26.2% (95% CI, 13.9%–42.0%; PR, n = 11; CR, n = 0), sufficient to reject the null hypothesis of ORR ≤10% (Table 2). All responses occurred by 3 months; 5 occurred by 3 weeks and 7 by 6 weeks. Median DOR was 7.1 months (range 2.8–34.6 months). Twenty patients (47.6%) had SD ≥6 weeks and 10 (23.8%) had progressive disease; 1 (2.4%) response was unknown. The DCR was 47.6%. Three of 13 patients in the DTIC arm had a PR (ORR, 23.1%; CR, n = 0; PR, n = 3; supplementary Tables S2 and S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 2.

Response to nilotinib, overall and by KIT mutation status

| Nilotinib 400 mg twice daily |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 42) | Exon 11 (n = 26) | Exon 13 (n = 13) | Othera (n = 3) | |

| Best overall response, n (%)b | ||||

| CR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PR | 11 (26.2) | 10 (38.5) | 1 (7.7) | 0 |

| SD | 20 (47.6) | 13 (50.0) | 5 (38.5) | 2 (66.7) |

| PD | 10 (23.8) | 3 (11.5) | 6 (46.2) | 1 (33.3) |

| Unknown | 1 (2.4)c | 0 | 1 (7.7) | 0 |

| ORR, % (95% CI)d | 26.2 (13.9–42.0) | 38.5 (12.1–39.5) | 7.7 (0.1–12.6) | 0 (0.0–8.4) |

| DOR, median (95% CI), monthse | 7.1 (4.2–not defined) | – | – | – |

| DCR, % (95% CI)f | 47.6 (32.0–63.6) | 61.5 (23.6–54.4) | 30.8 (2.7–22.6) | 0 (0.0–8.4) |

| PFS, median (95% CI), months | 4.2 (2.1–5.8) | 5.4 (2.7–8.3) | 2.8 (1.3–8.6) | 2.1 (1.9–2.8) |

| OS, median (95% CI), months | 18.0 (10.9–20.3) | – | – | – |

Exon 9 and exon 17 (Y823D).

Percentages for mutation subgroups are reported according to the number of patients in the respective mutation subgroups.

This patient discontinued nilotinib on study day 11 and withdrew consent on study day 22.

Rate of patients with CR + PR.

Median DOR was determined among the 11 responding patients. Median DOR was not determined according to mutation subgroups; however, all responding patients had an exon 11 mutation except for one patient with a mutation on exon 13 (DOR, 4.2 months).

Rate of patients with CR + PR + SD >12 weeks. SD in DCR is defined as lasting ≥12 weeks.

CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; DOR, duration of objective response; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

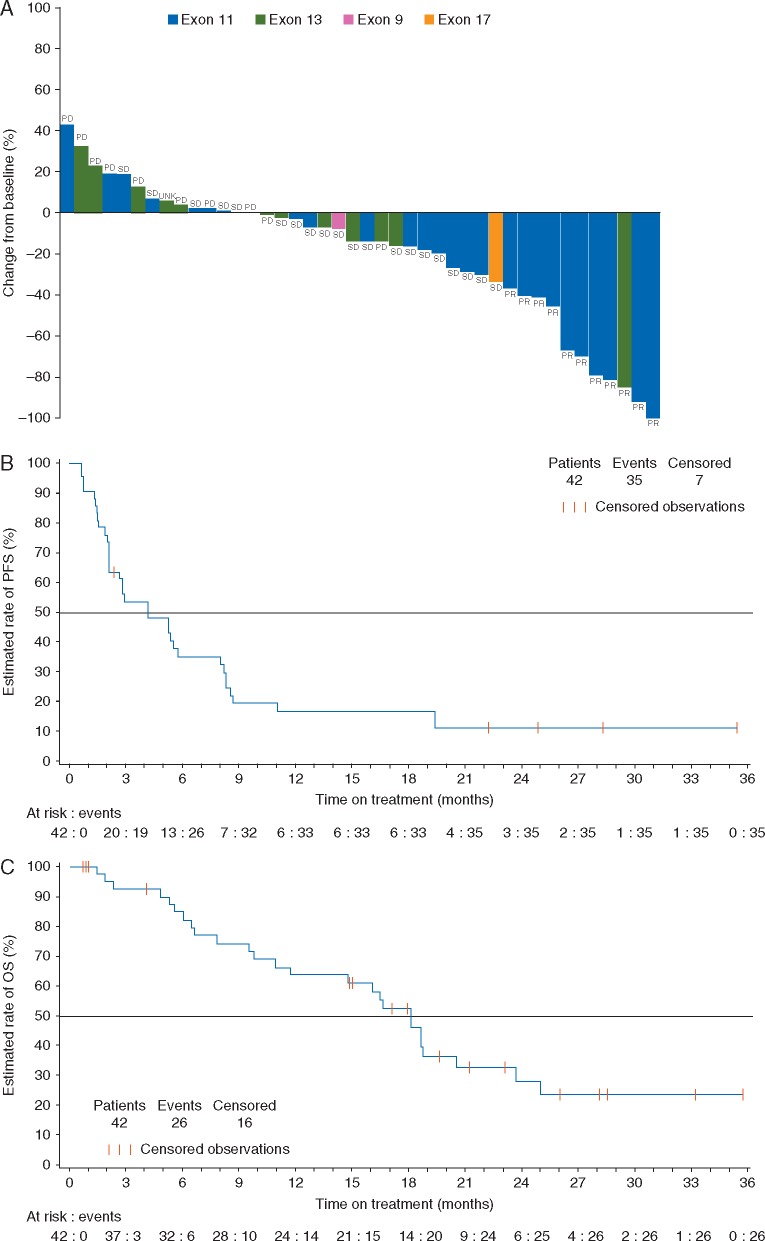

Response rate differed by mutation status; PR was observed in 10 of 26 patients (38.5%) with an exon 11 mutation, 1 of 13 patients (7.7%) with an exon 13 mutation, and 0 of 3 patients with an exon 9 or 17 mutation (Figure 1A). Of the 10 responding patients with an exon 11 mutation, three had the L576P mutation and one had a combined L576P/W557R mutation (Table 3). While the majority of observed mutations affect recurrently mutated sites and are thus considered likely to lead to constitutive KIT activation, a few of the identified mutations (i.e., S476C and D496N in exon 9 and R634W in exon 13) affect nonrecurrent sites and therefore may not be pathogenic.

Figure 1.

Tumor response and survival following nilotinib treatment. (A) Best percentage change from baselinea and best overall response to nilotinib. (B) Kaplan–Meier estimate of PFSb. (C) Kaplan–Meier estimate of OS. OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors; SD, stable disease; UNK, unknown. aBest percentage change from baseline determined from the sum of the longest diameter. bPatients who discontinued due to disease progression without PD per RECIST were not considered to have had a PFS event.

Table 3.

Best overall response by KIT mutation

| Patient | Melanoma type | Exon | KIT mutation | Baseline tumor size, cm | Best overall response | PFS, months | OS, months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acral | 11 | L576P | 7.6 | PR | 24.9a | 25.8b |

| 2 | Mucosal | 11 | L576P | 7.6 | PR | 5.4 | 9.4c |

| 3 | Mucosal | 11 | L576P | 22.1 | PR | 4.1 | 21.0b |

| 4 | Acral | 11 | L576P | 5.9 | SD | 2.1 | 6.6c |

| 5 | Mucosal | 11 | L576P | 3.8 | SD | 2.8a | 16.4c |

| 6 | Mucosal | 11 | L576P | 12.3 | SD | 19.4 | 20.3c |

| 7 | Mucosal | 11 | L576P | 3.3 | SD | 4.2 | 18.0c |

| 8 | Mucosal | 11 | L576P | 28.1 | SD | 5.6 | 7.8c |

| 9 | Mucosal | 11 | L576P | 2.2 | PD | 1.5 | 2.3c |

| 10 | CSD | 11 | V559A | 2.0 | PR | 19.4 | 32.9b |

| 11 | Mucosal | 11 | V559A | 2.1 | SD | 2.3a | 18.5d |

| 12 | Acral | 11 | V559A | 3.0 | PD | 0.7 | 1.0b |

| 13 | Acral | 11 | V560D | 7.7 | PR | 8.6 | 23.5c |

| 14 | Acral | 11 | V560D | 2.2 | SD | 8.2 | 14.7c |

| 15 | Acral | 11 | V560D | 4.5 | SD | 2.7 | 6.0c |

| 16 | Acral | 11 | W557C | 5.4 | SD | 2.1 | 18.5c |

| 17 | Acral | 11 | W557C | 20.9 | PD | 0.7 | 1.4c |

| 18 | Acral | 11 | W557R | 3.8 | PR | 35.4a | 35.4b |

| 19 | Acral | 11 | W557R | 5.6 | SD | 8.3 | 19.4b |

| 20 | Acral | 11 | D572G | 1.0 | SD | 2.1 | 14.9b |

| 21 | Acral | 11 | K558E | 9.2 | SD | 2.0 | 4.8e |

| 22 | Acral | 11 | K581_P585dup | 3.0 | PR | 8.3 | 16.5c |

| 23 | Mucosal | 11 | L576P, W557R | 9.2 | PR | 5.3 | 14.7b |

| 24 | Acral | 11 | V559D | 6.9 | PR | 28.3a | 28.3b |

| 25 | Mucosal | 11 | V569I | 25.9 | SD | 5.3 | 5.3c |

| 26 | Mucosal | 11 | W557hetdel | 10.5 | PR | 8.0 | 18.0c |

| 27 | Mucosal | 13 | K642E | 1.2 | PR | 5.8 | 18.6c |

| 28 | Acral | 13 | K642E | 5.2 | SD | 11.0 | 17.0b |

| 29 | Mucosal | 13 | K642E | 25.6 | SD | 2.8 | 5.5b |

| 30 | Acral | 13 | K642E | 10.1 | SD | 22.2a | 22.9b |

| 31 | Acral | 13 | K642E | 5.6 | SD | 8.6 | 11.6c |

| 32 | Mucosal | 13 | K642E | 3.1 | PD | 1.5 | 17.8b |

| 33 | Mucosal | 13 | K642E | 3.9 | PD | 0.7 | 15.9c |

| 34 | Acral | 13 | K642E | 9.8 | PD | 1.4 | 6.4c |

| 35 | Mucosal | 13 | K642E | 9.0 | PD | 1.3 | 10.9c |

| 36 | Mucosal | 13 | K642E | 16.3 | UNK | 0.7a | 0.7b |

| 37 | CSD | 13 | K642Q | 4.4 | PD | 1.4 | 27.9b |

| 38 | Acral | 13 | R634W | 12.4 | PD | 0.7 | 1.9c |

| 39 | Acral | 13 | V654A | 5.2 | SD | 2.9 | 24.8c |

| 40 | Mucosal | 9 | D496N | 1.8 | PD | 1.9 | 5.5c |

| 41 | Mucosal | 9 | S476C | 17.9 | SD | 2.8 | 4.0b |

| 42 | Mucosal | 17 | Y823D | 1.2 | SD | 2.1 | 9.7c |

Study day of censoring for PFS analysis. Patients were censored at the date of the last adequate tumor assessment (if they were alive and progression-free) or the first date of initiating other anticancer therapy.

Study day of censoring for OS analysis. If death was not observed, patients were censored at day of last contact.

Death due to study indication.

Death due to multi-organ dysfunction.

Death due to cardiopulmonary arrest.

CSD, chronic sun damage; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; UNK, unknown.

Thirty-five patients had PFS events (median PFS of 4.2 months; 95% CI, 2.1–5.8 months). At 6 months, the estimated PFS rate was 34.6% (95% CI, 20.2%–49.3%; Figure 1B). Among the 26 patients with an exon 11 mutation, median PFS was 5.4 months (95% CI, 2.7–8.3 months); the 6-month estimated PFS rate was 43.1% (95% CI, 23.4%–61.5%).

Twenty-six deaths occurred [due to melanoma (n = 24), cardiopulmonary arrest (n = 1), multiorgan dysfunction (n = 1)]. Of these, one death (due to melanoma) occurred within 30 days of discontinuation. No deaths were considered by the investigators to be attributable to nilotinib. Median OS was 18.0 months (95% CI, 10.9–20.3 months). Estimated OS rates at 12 and 24 months were 63.6% (95% CI, 46.4%–76.6%) and 27.7% (95% CI, 13.3%–44.2%), respectively (Figure 1C). Among the 26 patients with an exon 11 mutation, 17 died on study and three were alive and receiving nilotinib with ≥25.8 months’ follow-up. PFS and OS in DTIC-treated patients are shown in supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Safety

Nilotinib was well tolerated, with a safety profile consistent with reports of nilotinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia [14]. No additional safety issues were observed on crossover to nilotinib, although data for this population are limited. Full safety data are provided in supplementary Tables S4–S6, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Discussion

Results from the TEAM trial showed that nilotinib is an active agent in patients with KIT-mutated metastatic melanoma. Similar results have been reported in other studies of nilotinib in patients with advanced melanoma with KIT aberrations, including patients with prior imatinib resistance [15–17]; response rates and survival in these nilotinib studies are similar to those in reports of imatinib treatment in patients with KIT-mutated melanoma (supplementary Table S7, available at Annals of Oncology online) [7–9].

Response rates to imatinib and nilotinib in patients with KIT mutations [7–9, 15–17] are approximately half of those observed in pivotal trials of BRAF inhibitors in patients with BRAF-mutated advanced melanoma [10, 11]. This may result from heterogeneity of KIT mutations relative to BRAF mutations (of which 74% are V600E) and/or a lower efficacy of current KIT inhibitors [19]. Additionally, RAS mutations may confer resistance to KIT inhibitors [9]; although prior data suggest low incidences of concurrent KIT/RAS mutations [2, 9], the RAS mutation status of patients enrolled in TEAM is unknown.

Although the TEAM trial was not powered to statistically determine response rates according to mutation subtypes, numerical differences were observed by mutation. Patients with an exon 11 mutation had a better response rate than patients with an exon 13 mutation. Too few patients had exon 9 or 17 mutations to draw conclusions in these subpopulations. Consistent with prior studies of imatinib and nilotinib, the most frequently observed mutation among responding patients in TEAM was L576P on exon 11 [9, 16], a common KIT-activating mutation [2, 20]. Results from TEAM suggest that nilotinib may have activity in these patients, with 4 of 10 patients (40.0%) with L576P (including 1 with a concurrent W557R mutation) responding to nilotinib.

The response rate among DTIC-treated patients (23.1%) was higher than has been historically observed for DTIC [21], suggesting that patients enrolled in TEAM may have had less aggressive disease than the general population of patients with advanced KIT-mutated melanomas. Formal comparison of nilotinib and DTIC was not conducted due to partial randomization in the nilotinib arm and the very low number of patients in the DTIC arm. A randomized controlled trial of nilotinib versus standard of care in patients with advanced KIT-mutated melanoma may be needed to further evaluate nilotinib efficacy in this population. However, the inability to recruit a sufficient number of patients for a randomized controlled trial demonstrates the difficulty of conducting large trials in uncommon molecular subsets of advanced diseases.

Potential limitations of this study include the lower enrollment target and changes in study design following the protocol amendments, which may have impacted the strength of the results. Additionally, the majority of patients had mucosal/acral melanoma, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to other subtypes known to harbor KIT aberrations, such as melanomas arising on skin with CSD. However, patients with mucosal/acral melanoma may be most appropriate for KIT inhibitor treatment because KIT mutations are most commonly observed in these subtypes [2].

Overall, nilotinib demonstrated activity in patients with advanced melanoma with KIT mutations without prior KIT inhibitor treatment. Although these data did not show an advantage for nilotinib relative to historical data with imatinib, they do suggest that nilotinib may be an additional treatment option for patients with KIT-mutated advanced melanoma, for example, in patients intolerant of imatinib. The treatment landscape for advanced melanoma is rapidly changing with the availability of immunotherapies such as inhibitors of programmed cell death protein 1 (e.g. nivolumab, pembrolizumab) or cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (e.g. ipilimumab), which have shown activity in acral and/or mucosal melanomas (ORRs, 11.4%–23.3%) [22–24]. Thus, a potential role for KIT inhibitors may be in combination with or following disease progression on immunotherapy. Further studies are needed to investigate the potential efficacy of nilotinib in patients with advanced KIT-mutated melanoma, either in combination with immunotherapy or in the setting of disease refractory to immunotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steven Green (Novartis) for statistical input and Joy Loh, PhD, and Jonathan Morgan, PhD (ArticulateScience LLC), for medical editorial assistance with this manuscript. Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Funding

This study was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. No grant number applied.

Disclosure

The authors declare the following relationships: JG: Bayer (consulting or advisory role), Novartis (consulting or advisory role), Merck (consulting or advisory role); RDC: Novartis (consulting or advisory role, research funding), AstraZeneca (consulting or advisory role, research funding), Merck (consulting or advisory role, research funding), Janssen (consulting or advisory role), Aura Biosciences (consulting or advisory role), Iconic Therapeutics (consulting or advisory role), Bristol-Myers Squibb (research funding), Eli Lilly (research funding), Daiichi-Sankyo (research funding), Amgen (research funding), Immunocore (research funding), Incyte (research funding), Celldex (research funding), Genentech (research funding), Mirati (research funding), Macrogenics (research funding), Regeneron (research funding); RD: Novartis (research funding, consulting or advisory role), Merck Sharp & Dohme (research funding, consulting or advisory role), Bristol-Myers Squibb (research funding, consulting or advisory role), Dohme (research funding, consulting or advisory role), GlaxoSmithKline (research funding, consulting or advisory role), Amgen (consulting or advisory role); AH: Amgen (consulting or advisory role, honoraria, research funding), Bristol-Myers Squibb (consulting or advisory role, honoraria, research funding), MedImmune (consulting or advisory role, honoraria), MSD/Merck (consulting or advisory role, honoraria, research funding), Nektar Therapeutics (consulting or advisory role, honoraria), Novartis (consulting or advisory role, honoraria, research funding), Oncosec (consulting or advisory role, honoraria), Philogen (consulting or advisory role, honoraria), Provectus (consulting or advisory role, honoraria), Regeneron (consulting or advisory role, honoraria), Roche (consulting or advisory role, honoraria, research funding), Celgene (research funding), Eisai (research funding), GlaxoSmithKline (research funding), Merck Serono (research funding); AD: OncoSec (stock or other ownership, patent or intellectual property), Novartis (consulting or advisory role), Merck (consulting or advisory role, research funding), Pfizer (consulting or advisory role, research funding), Genentech (consulting or advisory role, research funding), Bristol-Myers Squibb (research funding); BCB: Illumina (stock or other ownership), Novartis (stock or other ownership, consulting or advisory role), Roche (consulting or advisory role), Daiichi-Sankyo (research funding), University of California (San Francisco) (institution holds a patent US 20140045182 A1); AA: Novartis (research funding); CB: AstraZeneca (personal fees), Amgen (personal fees), Bristol-Myers Squibb (personal fees, non-financial support), GlaxoSmithKline (personal fees), MSD (personal fees, non-financial support), Novartis (personal fees), Roche (personal fees, non-financial support), Pierre Fabre (personal fees); TP: Novartis (consulting or advisory role, honoraria, research funding); DS: Amgen (personal fees), GlaxoSmithKline (personal fees), Bristol-Myers Squibb (personal fees), Novartis (personal fees), Roche (personal fees), Merck (personal fees); WS: Bristol-Myers Squibb (grant, personal fees for consulting), Merck (grant, personal fees for consulting), Castle Biosciences (personal fees for consulting); SN: Novartis (employment and stock ownership); SH: Novartis (employment and stock ownership); CN: Novartis (employment and stock ownership); QC: Novartis (employment and stock ownership); FSH: Novartis (consulting or advisory role), Merck (consulting or advisory role), Genentech (consulting or advisory role), Synta (consulting or advisory role), Celldex (consulting or advisory role), Bristol-Myers Squibb (research funding paid to institution). All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Key Message

In a phase II, single-arm trial, the KIT-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor nilotinib demonstrated activity in patients with KIT-mutated advanced melanoma. The activity of nilotinib was similar to historical data from imatinib-treated patients, suggesting that nilotinib may be an effective treatment option for patients with KIT-mutated melanoma.

References

- 1. Lovly CM, Dahlman KB, Fohn LE. et al. Routine multiplex mutational profiling of melanomas enables enrollment in genotype-driven therapeutic trials. PLoS One 2012; 7: e35309.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, Bastian BC.. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 4340–4346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corless CL, Other KIT mutations in melanoma. 22 October 2014. https://www.mycancergenome.org/content/disease/melanoma/kit/132/ (9 September 2016, date last accessed).

- 4. Hodi FS, Friedlander P, Corless CL. et al. Major response to imatinib mesylate in KIT-mutated melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 2046–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Satzger I, Kuttler U, Volker B. et al. Anal mucosal melanoma with KIT-activating mutation and response to imatinib therapy—case report and review of the literature. Dermatology (Basel) 2010; 220: 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lutzky J, Bauer J, Bastian BC.. Dose-dependent, complete response to imatinib of a metastatic mucosal melanoma with a K642E KIT mutation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2008; 21: 492–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carvajal RD, Antonescu CR, Wolchok JD. et al. KIT as a therapeutic target in metastatic melanoma. JAMA 2011; 305: 2327–2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guo J, Si L, Kong Y. et al. Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 2904–2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hodi FS, Corless CL, Giobbie-Hurder A. et al. Imatinib for melanomas harboring mutationally activated or amplified KIT arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun-damaged skin. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 3182–3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C. et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 2507–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV. et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weisberg E, Manley PW, Breitenstein W. et al. Characterization of AMN107, a selective inhibitor of native and mutant Bcr-Abl. Cancer Cell 2005; 7: 129–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guo T, Hajdu M, Agaram NP. et al. Mechanisms of sunitinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumors harboring KITAY502-3ins mutation: an in vitro mutagenesis screen for drug resistance. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 6862–6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S. et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 2251–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carvajal RD, Lawrence DP, Weber JS. et al. Phase II study of nilotinib in melanoma harboring KIT alterations following progression to prior KIT inhibition. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 2289–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee SJ, Kim TM, Kim YJ. et al. Phase II trial of nilotinib in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma harboring KIT gene aberration: a multicenter trial of Korean Cancer Study Group (UN10-06). Oncologist 2015; 20: 1312–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lebbe C, Chevret S, Jouary T. et al. Phase II multicentric uncontrolled national trial assessing the efficacy of nilotinib in the treatment of advanced melanomas with c-KIT mutation or amplification. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2014; 32: 9032. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lesteven E, Battistella M, Jouary T. et al. Phase II multicentric uncontrolled national trial assessing the efficacy of nilotinib in the treatment of advanced melanomas with c-KIT mutation or amplification: results of the pharmacodynamic study. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2015; 33: e20062. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Long GV, Menzies AM, Nagrial AM. et al. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of oncogenic BRAF in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1239–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Torres-Cabala CA, Wang WL, Trent J. et al. Correlation between KIT expression and KIT mutation in melanoma: a study of 173 cases with emphasis on the acral-lentiginous/mucosal type. Mod Pathol 2009; 22: 1446–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chapman PB, Einhorn LH, Meyers ML. et al. Phase III multicenter randomized trial of the Dartmouth regimen versus dacarbazine in patients with metastatic melanoma. JCO 1999; 17: 2745–2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson DB, Peng C, Abramson RG. et al. Clinical activity of ipilimumab in acral melanoma: a retrospective review. Oncologist 2015; 20: 648–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Del Vecchio M, Di Guardo L, Ascierto PA. et al. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab 3 mg/kg in patients with pretreated, metastatic, mucosal melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50: 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Larkin J, D'Angelo S, Sosman JA. et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab (NIVO) monotherapy in the treatment of advanced mucosal melanoma (MEL). Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2015; 28: 789. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.