Abstract

Background

RECORD-3 compared everolimus and sunitinib as first-line therapy, and the sequence of everolimus followed by sunitinib at progression compared with the opposite (standard) sequence in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). This final overall survival (OS) analysis evaluated mature data for secondary end points.

Patients and methods

Patients received either first-line everolimus followed by second-line sunitinib at progression (n = 238) or first-line sunitinib followed by second-line everolimus (n = 233). Secondary end points were combined first- and second-line progression-free survival (PFS), OS, and safety. The impacts of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and baseline levels of soluble biomarkers on OS were explored.

Results

At final analysis, median duration of exposure was 5.6 months for everolimus and 8.3 months for sunitinib. Median combined PFS was 21.7 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 15.1–26.7] with everolimus-sunitinib and 22.2 months (95% CI 16.0–29.8) with sunitinib-everolimus [hazard ratio (HR)EVE-SUN/SUN-EVE, 1.2; 95% CI 0.9–1.6]. Median OS was 22.4 months (95% CI 18.6–33.3) for everolimus-sunitinib and 29.5 months (95% CI 22.8–33.1) for sunitinib-everolimus (HREVE-SUN/SUN-EVE, 1.1; 95% CI 0.9–1.4). The rates of grade 3 and 4 adverse events suspected to be related to second-line therapy were 47% with everolimus and 57% with sunitinib. Higher NLR and 12 soluble biomarker levels were identified as prognostic markers for poor OS with the association being largely independent of treatment sequences.

Conclusions

Results of this final OS analysis support the sequence of sunitinib followed by everolimus at progression in patients with mRCC. The safety profiles of everolimus and sunitinib were consistent with those previously reported, and there were no unexpected safety signals.

Clinical Trials number

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00903175

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, sequential targeted therapy, everolimus, sunitinib

Introduction

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors are standard treatment options for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). Current treatment guidelines for patients with mRCC recommend a first-line VEGF inhibitor, including sunitinib, followed by everolimus at progression [1, 2]. RECORD-3 (REnal Cell cancer treatment with Oral RAD001 given Daily; ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT00903175) was a randomized phase IIb trial that compared outcomes of everolimus and sunitinib as first-line therapy, and the sequence of everolimus followed by sunitinib at progression compared with the opposite (standard) sequence [3]. In the primary analysis, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 7.9 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 5.6–8.2] with first-line everolimus and 10.7 months (95% CI 8.2–11.5) with first-line sunitinib [hazard ratio (HR), 1.43; 95% CI 1.15–1.77]. The noninferiority margin was not achieved; therefore, the primary end point was not met. The objective of the final analyses was to evaluate mature data for secondary end points of combined first-line and second-line PFS (combined PFS), overall survival (OS), and safety, and to conduct exploratory analyses of various biomarkers.

Patients and methods

Patients and study design

RECORD-3 study design has been reported [3]. Briefly, patients who were ≥18 years of age with measurable mRCC as per Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors version 1.0 (RECIST v1.0) were included in the study. Prior nephrectomy was not required. Key eligibility criteria included no prior systemic therapy; Karnofsky performance status (KPS) ≥70%; adequate hematologic, liver, and kidney function; and normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Patients were randomly assigned 1 : 1 to receive either first-line everolimus 10 mg/day or sunitinib 50 mg/day (4 weeks on, 2 weeks off) until first occurrence of progressive disease (PD) (RECIST v1.0). Patients then crossed over and continued on the alternative drug until second occurrence of PD. The crossover period was defined as the time after the end of first-line therapy and before the start of second-line therapy (crossover to occur within 35 days of progression).

Objectives and assessments

Key secondary objectives of the RECORD-3 study were to compare combined PFS and OS between the two treatment sequences. The objective of these final analyses was to assess mature data for combined PFS, OS, and adverse events (AEs). OS by histologic subtypes (clear cell and nonclear cell) and the impact of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and cytokines on OS were evaluated as exploratory end points.

Tumor assessments (RECIST v1.0) were carried out every 12 weeks from randomization until progression or start of another anticancer treatment. AEs, physical examination, and blood work were assessed at baseline and continually thereafter.

Statistical methods

Two criteria were used to declare noninferiority of everolimus compared with sunitinib in terms of first-line PFS [4]. The first criterion was an estimated HR ≤1.1 and the second criterion was an upper estimated one-sided 90% confidence bound ≤1.27, which required 318 PFS events so that fulfillment of first criterion implied the second.

The full analysis set (FAS) included all randomly assigned patients analyzed according to the assigned study treatment and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) prognosis. The safety population included all patients who received at least one dose of either study drug and underwent at least one safety assessment in the first-line period. The second-line safety population included the subset of patients who received at least one dose of second-line everolimus or sunitinib. The biomarker population included all patients with valid biomarker data. Combined PFS was defined as the time from randomization to progression after second-line treatment or death from any cause. Patients who did not cross over to second-line therapy or who did not experience progression after the start of second-line treatment or who were alive at data cutoff for the analysis or at the time of receiving an additional anticancer therapy were censored at last date of tumor evaluation. No formal sample size and power calculation were made for combined PFS. OS was defined as time from randomization to death. The preplanned final OS analysis occurred at the end of the 3-year follow-up period. No formal power calculation was made for the OS analysis and the expected number of deaths was 300. As for the primary endpoint, an OS noninferiority margin was pre-defined. The upper estimated, one-sided 90% confidence bound of the OS HR was to be ≤1.06 to conclude that OS with EVE-SUN is noninferior to SUN-EVE. This value of 1.06 corresponds to approximately one and a half month’s difference in median OS between EVE-SUN and SUN-EVE. The data cutoff date for the final analysis was 16 June 2014.

The neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (defined as absolute neutrophil count from segments and bands, divided by the absolute lymphocyte count) at baseline was dichotomized (≤/> median across all patients). Similarly each soluble biomarker was dichotomized into low/high categories (as </≥ median across all patients). The associations between baseline biomarker (NLR) categories and OS were assessed via Cox proportional hazards models, Kaplan–Meier curves, and log-rank tests. The Kaplan–Meier estimates of the OS function within treatment arm and biomarker (NLR) category were computed according to the Kaplan–Meier product-limit method. Median OS times and 95% CIs are presented for each category. HRs and 95% CIs were estimated from a Cox proportional hazards model for OS, stratified by MSKCC risk groups, with terms for randomized first-line treatment, baseline biomarker (NLR), and treatment-by-biomarker (NLR) interaction. Additional information is presented as supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Results

Patients

From October 2009 to June 2011, 471 patients (FAS population) were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive either first-line everolimus followed by second-line sunitinib at progression (n = 238) or first-line sunitinib followed by second-line everolimus (n = 233). There were 469 patients in the safety population. In the primary analysis, baseline characteristics were generally balanced between treatment arms (Table 1).

Table 1.

RECORD-3 primary analysis summary of key characteristics and primary end point [4]

| Key baseline characteristics | First-line everolimus arm (n = 238) | First-line sunitinib arm (n = 233) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (range) | 62 (20–89) | 62 (29–84) |

| Sex, men/women, n (%) | 166 (70)/72 (30) | 176 (76)/57 (25) |

| KPS, n (%) | ||

| ≥90 | 158 (66) | 181 (78) |

| 80 | 61 (26) | 43 (19) |

| 70 | 18 (8) | 8 (3) |

| Missing | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Predominant tumor histology subtype, n (%) | ||

| Clear cell | 205 (86) | 197 (85) |

| Nonclear cell | 31 (13) | 35 (15) |

| Missing | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Prior nephrectomy, n (%) | 159 (67) | 156 (67) |

| MSKCC risk group, n (%) | ||

| Favorable | 70 (29) | 69 (30) |

| Intermediate | 132 (56) | 131 (56) |

| Poor | 35 (15) | 32 (14) |

| Primary end point | ||

| Median PFS, months (95% CI) | 7.9 (5.6–8.2) | 10.7 (8.2–11.5) |

| HR, 1.43 (95% CI 1.15–1.77) | ||

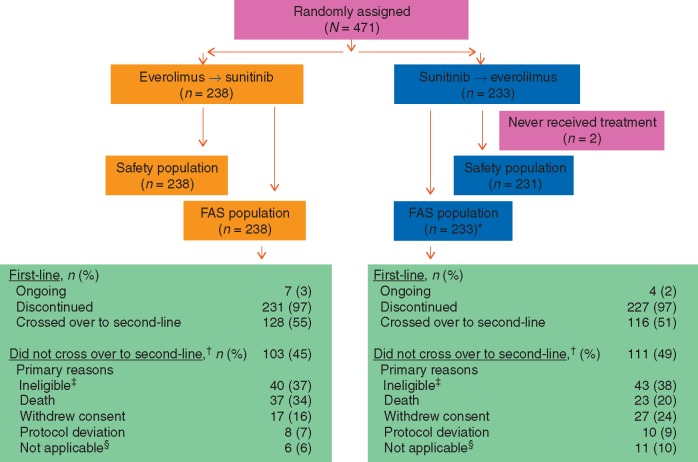

Patient disposition and treatment duration at final OS analysis

At final OS analysis, seven patients (3%) were still receiving first-line everolimus (treatment duration range, 3.1–4.9 years) and four patients (2%) were still receiving first-line sunitinib (treatment duration range, 3.1–4.2 years). In the first-line setting, median duration of exposure was 5.6 months for everolimus and 8.3 months for sunitinib. Among patients who discontinued first-line treatment, 128 (55%) crossed over from everolimus to sunitinib and 116 (51%) crossed over from sunitinib to everolimus. The primary protocol-related reason for not crossing over was ineligibility, which included poor performance status or decline in condition primarily related to PD, brain metastases, or persistent AE (Figure 1). Seven patients (6%) were still receiving second-line sunitinib and four patients (3%) were still receiving second-line everolimus. In the second-line setting, median duration of exposure was 3.4 months for everolimus and 5.7 months for sunitinib. The most common reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression (67%, everolimus; 61%, sunitinib). Median duration of follow-up was approximately 3.7 years.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. *Indicates two patients randomly assigned to receive sunitinib did not receive treatment. †Indicates after first-line treatment discontinuation. ‡Indicates ineligibility included poor performance status or decline in condition primarily related to progressive disease, brain metastases, or persistent adverse events. §Patients crossed over after the cutoff date. FAS, full analysis set.

Combined PFS and OS at final OS analysis

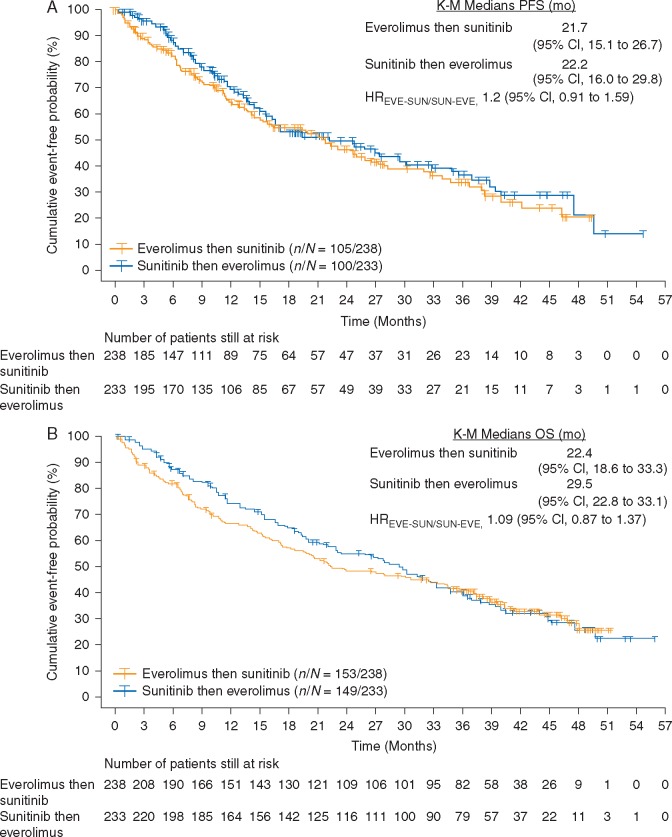

At final OS analysis, median combined PFS was 21.7 months (95% CI 15.1–26.7) with sequential everolimus and sunitinib and 22.2 months (95% CI 16.0–29.8) with sequential sunitinib and everolimus (HREVE-SUN/SUN-EVE, 1.2; 95% CI 0.9–1.6) (Figure 2A). Censoring rates were 56% for sequential everolimus and sunitinib and 57% for sequential sunitinib and everolimus. The primary reason for censoring was no timely crossover to second-line therapy, which led to questionable robustness of Kaplan–Meier estimates and might have confounded the HR estimate.

Figure 2.

(A) Kaplan–Meier estimates of combined first-line and second-line PFS in the FAS population. (B) Kaplan–Meier estimates of OS in the overall population.

Overall, 64% of patients in each treatment arm died. Median OS was 22.4 months (95% CI 18.6–33.3) for sequential everolimus and sunitinib and 29.5 months (95% CI 22.8–33.1) for sequential sunitinib and everolimus (HREVE-SUN/SUN-EVE, 1.1; 95% CI 0.9–1.4) (Figure 2B). The two-sided 80% CI upper limit of 1.27 was above the noninferiority margin of 1.06. Median OS was similar between treatment arms among patients with clear cell mRCC and those with nonclear cell mRCC. In the clear cell group, median OS was 23.9 months for sequential everolimus and sunitinib (n = 207) and 30.2 months for sequential sunitinib and everolimus (n = 197) (HREVE-SUN/SUN-EVE, 1.1; 95% CI 0.9–1.4). Among patients with nonclear cell mRCC, median OS was 16.2 months for sequential everolimus and sunitinib (n = 29) and 16.8 months for sequential sunitinib and everolimus (n = 35) (HREVE-SUN/SUN-EVE, 1.0; 95% CI 0.6–1.8).

In each first-line treatment arm, 18% (n = 43) of patients did not cross over to per-protocol second-line treatment, but did subsequently receive off-protocol antineoplastic therapy after study drug discontinuation. Among those patients, 14 in the first-line everolimus arm received second-line sunitinib and 6 in the first-line sunitinib arm received second-line everolimus. After second-line treatment discontinuation, ∼50% of the patients from each treatment arm received subsequent antineoplastic therapy.

AE profile

The most frequently reported AEs during first-line everolimus and first-line sunitinib, respectively, were stomatitis (53% and 58%), fatigue (47% and 53%), and diarrhea (40% and 58%). The rates of grade 3 and 4 AEs suspected to be related to first-line therapy were 47% with everolimus and 63% with sunitinib. At final OS analysis, the most frequently reported AEs during second-line everolimus were fatigue (35%), stomatitis (32%), and anemia (32%) (Table 2). The most frequently reported AEs during second-line sunitinib were diarrhea (54%), fatigue (38%), nausea (38%), decreased appetite (33%), and hypertension (33%) (Table 2). The rates of grade 3 and 4 AEs suspected to be related to second-line therapy were 47% with everolimus and 57% with sunitinib. Within each treatment sequence, the rates of grade 3 and 4 AEs suspected to be related to treatment were 62% in the sequential everolimus and sunitinib arm and 71% in the sequential sunitinib and everolimus arm.

Table 2.

All-grade AEs during second-line therapy (≥20% incidencea)

| AEb(%) | Second-line everolimus (n = 238) | Second-line sunitinib (n = 231) |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 35 | 38 |

| Stomatitis | 32 | 28 |

| Anemia | 32 | 14 |

| Decreased appetite | 28 | 33 |

| Dyspnea | 24 | 16 |

| Cough | 24 | 15 |

| Nausea | 20 | 38 |

| Peripheral edema | 20 | 20 |

| Diarrhea | 15 | 54 |

| Vomiting | 10 | 27 |

| Dysgeusia | 7 | 24 |

| Hypertension | 5 | 33 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 | 24 |

| Hand-foot syndrome | 2 | 29 |

≥20% for at least 1 of the second-line agents.

Only on-treatment AEs are presented. On-treatment AEs and deaths were those that occurred up to 28 days after discontinuation of study treatment.

AE, adverse events.

In the safety population there were 34 (14%) on-treatment deaths in the first-line everolimus arm (n = 238) and 15 (6%) on-treatment deaths in the first-line sunitinib arm (n = 231). In the second-line safety population there were 11 (9%) on-treatment deaths of patients who received everolimus (n = 116) and 12 (9%) on-treatment deaths of patients who received sunitinib (n = 128).

Prognostic factors

Our previous research work, based on a survey of a large panel of soluble molecules involved in multiple biological processes, showed that the baseline levels of 12 biomarkers were prognostic indicators for the first-line PFS [5]. With the availability of OS data, the prognostic values of these biomarkers were evaluated. All 12 biomarkers were also associated with OS in the same direction as they were associated with first-line PFS, always with an association of a higher biomarker level and a shorter OS (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The impact of these biomarkers on OS by the treatment sequence was often similar. Whenever there was a difference, however, the impact was often more evident on the everolimus-sunitinib sequence than the standard sequence. Of note, the baseline levels of these cytokines were well balanced between the treatment sequences, supporting the adequacy of the OS comparison analysis.

Elevated NLR has recently been shown as a poor prognostic factor for survival in multiple cancer types, including RCC [6, 7]. A similar prognostic signal was confirmed in the RECORD-3 population, although the magnitude was slightly lower than that reported in a meta-analysis (HR 1.85 versus 2.27) (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). The association between NLR and the OS was largely independent of the treatment sequences (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Discussion

On the basis of the first-line PFS HR estimates (primary efficacy analysis), EVE did not demonstrate noninferiority compared with SUN. The inferiority of EVE versus SUN could also not be formally concluded. However, the different safety profile as well as the observed shorter median PFS for first-line EVE [with an HR of 1.4 (95% CI 1.2–1.8)] were deemed to be clinically relevant supporting the standard sequence of first-line sunitinib followed by everolimus at progression for patients with mRCC [3]. Results of the RECORD-4 trial provided additional insight into outcomes of patients with mRCC treated with second-line everolimus (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier, NCT01491672) [8]. In RECORD-4, PFS, and OS were evaluated for second-line everolimus in three cohorts of patients that were enrolled into the trial based on their first-line therapy. Results of RECORD-4 showed a median PFS of 7.8 months in the overall population and in the cohort of patients who received first-line treatment with other anti-VEGF agents (sorafenib, bevacizumab, pazopanib, tivozanib, or axitinib) and a median PFS of 5.7 months for the cohort of patients who received first-line sunitinib. At final OS analysis, median OS was 23.8 months in the overall population and in the first-line sunitinib cohort, and 17.2 months in the other previous anti-VEGF therapy cohort. These results confirmed the survival benefit of second-line everolimus after receiving first-line sunitinib or various other first-line anti-VEGF therapies. However, three new agents that were evaluated in studies of patients previously treated with one or two VEGF-targeted agents have shown survival advantages over everolimus. Results of one study, the phase III CheckMate-025 trial, showed a longer median OS with nivolumab (an inhibitor of the programmed death-1 pathway) over everolimus (25.0 and 19.6 months, respectively) in VEGF-refractory patients with mRCC; median PFS was similar for both agents (4.6 and 4.4 months, respectively; P = 0.11) [9]. In another study, results of the phase III METEOR trial showed a PFS and OS advantage of cabozantinib (an inhibitor of VEGFR2 and c-MET) over everolimus (median PFS 7.4 and 3.9 months, respectively; P <0.0001: median OS 21.4 and 16.5 months, respectively; P = 0.00026) [10]. Phase II study results showed PFS and OS benefits with lenvatinib (a multikinase inhibitor) combined with everolimus compared with everolimus monotherapy (median PFS 14.6 versus 5.5 months, respectively; P = 0.0005: median OS, 25.5 and 15.4 months, respectively; P = 0.024) [11]. Recent regulatory approval of these new agents has changed the second-line treatment landscape for patients with mRCC.

Survival of patients with mRCC has improved since the advent of targeted therapy. For example, results of pivotal phase III studies of first-line VEGF-targeted agents (sunitinib, sorafenib, pazopanib, and bevacizumab) showed that median OS ranged from 19.3 months with sorafenib to 26.4 months with sunitinib [12, 13]. As the treatment landscape changed and targeted agents were developed for second- and later-line use in patients with mRCC, patient survival continued to improve. Results of pivotal studies of targeted agents in the second- or later-line showed a median OS of 14.8 months for patients who received everolimus following treatment with sunitinib or sorafenib (or both) and a median OS of 15.2 months for patients who received axitinib following treatment with sunitinib [14, 15]. The RECORD-3 final OS analysis can only be considered descriptive given that the study failed to meet its primary endpoint. In this final OS analysis, the median OS of 29.5 months for sequential sunitinib and everolimus suggests an improvement from earlier trials in which access to a second-line mTOR inhibitor was not readily available, and the median OS is comparable with that of more recent trials in which patients receiving a first-line VEGFR targeted therapy had access to a second-line agent [16]. The observed shorter median OS for the EVE-SUN sequence (22.4 months) versus SUN-EVE (29.5 months), which is associated with an HR (EVE-SUN versus SUN-EVE) of 1.1 (95% CI 0.9–1.4), is considered consistent with the primary endpoint PFS results. Although not supported by any formal statistical testing, this observed improved median OS in SUN-EVE was also deemed clinically relevant to further support the standard treatment sequence of sunitinib followed by everolimus.

In RECORD-3, the rate (50%–54%) of crossover to second-line therapy was surprisingly low; however, the median combined PFS of 22.2 months for sequential sunitinib and everolimus is a novel end point that was not previously established in prospective trials, and it can serve as a new reference in clinical trials designed to study sequential therapy. Because of high censoring rates, there are limitations to the interpretation of our combined PFS results.

In this RECORD-3 final OS analysis, AEs remained consistent with the known safety profiles of everolimus and sunitinib. The most commonly reported AEs with second-line everolimus were fatigue, stomatitis, and anemia and with second-line sunitinib were diarrhea, fatigue, and nausea. No new safety signals were identified for either agent.

The predictive values of biomarkers could not be robustly assessed because they were confounded by the cross-over design. Evaluation of the soluble biomarkers, which were identified as prognostic factors for first-line PFS, showed that they are also likely prognostic for OS, often independent of the treatment sequences. These prognostic factors and the NLR may be considered as stratification factors in future trial designs or as impactful covariates in the statistical analyses, especially in randomized trials of relatively small sample sizes, to avoid drastic imbalances.

Conclusions

Final OS analysis results are consistent with initial results and further support the sequence of VEGFR-targeted therapy followed by everolimus, in clear cell and nonclear cell mRCC, at progression. The AE profiles of everolimus and sunitinib were consistent with those previously reported, and there were no unexpected safety signals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Editorial assistance was provided by Cathy R. Winter, PhD (ApotheCom, Yardley, PA) and funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Funding

This work was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. Robert J. Motzer’s efforts were supported by MSK Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748).

Disclosure

JJK has received research grants from Astra Zeneca and consulting fees for serving as an advisor to Merck; CHB has received research grants from Pfizer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche/Genentech, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and MSD and consulting fees from Pfizer, Novartis, Roche/Genentech; KP has served in a consulting or advisory role for Novartis, Roche, and Boehringer-Ingelheim; RS has received honoraria and has served in an advisory or consulting role for Novartis and Pfizer, and has received funding for travel, accommodations, or expenses from Pfizer; RDP has received honoraria from Astellas, has served in a consulting or advisory role for Via Oncology, and has received funding for research from Sarah Cannon Research Institute; JTB has received research grants from Novartis; SY has served in a consulting or advisory role for Novartis; PP has received honoraria from GSK and Pfizer; has served in a consulting or advisory role for Roche, GSK, and Scancell; has served on speaker’s bureaus for GSK, and Pfizer; and has received research funding from Scancell; and has received funding for travel, accommodations, and expenses for Merck, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, and GSK; LG has received honoraria and travel, accommodations or expenses from Novartis; and has served as a consulting or advisory role for Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.; JN is an employee of and has received funding for travel, accommodations, or expenses from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.; NB is an employee of and owns stock in Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.; MM is an employee of and owns stock in Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.; DC is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.; RJM has received research grants from Novartis, Pfizer, BMS, GlaxoSmithKline, and Genentech; and has received consulting fees from Novartis and Pfizer. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Key Message

In the RECORD-3 final analysis, median combined PFS was 21.7 months for EVE-SUN and 22.2 months for SUN-EVE (HR, 1.2; 95% CI 0.9–1.6). Median OS was 22.4 months for EVE-SUN and 29.5 months for SUN-EVE (HR, 1.1; 95% CI 0.9–1.4). Safety profiles were consistent with previous reports, and there were no unexpected safety signals. Efficacy results support the SUN-EVE sequence in patients with mRCC.

References

- 1. Escudier B, Porta C, Schmidinger M. et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014; 25 (Suppl 3): iii49–iii56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Kidney Cancer—v1.2017. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/kidney.pdf. (2 March 2017, date last accessed)

- 3. Motzer RJ, Barrios CH, Kim TM. et al. Phase II randomized trial comparing sequential first-line everolimus and second-line sunitinib versus first-line sunitinib and second-line everolimus in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 2765–2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neuenschwander B, Rouyrre N, Hollaender N. et al. A proof of concept phase II non-inferiority criterion. Stat Med 2011; 30: 1618–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Voss MH, Chen D, Marker M. et al. Circulating biomarkers and outcome from a randomised phase II trial of sunitinib vs everolimus for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2016; 114: 642–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Seruga B. et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106: doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Templeton AJ, Knox JJ, Lin X. et al. Change in neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in response to targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma as a prognosticator and biomarker of efficacy. Eur Urol 2016; 70: 358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Motzer RJ, Alyasova A, Ye D. et al. Phase 2 trial of second-line everolimus in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RECORD-4). Ann Oncol 2016; 27(3): 441–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF. et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1803–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T. et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1814–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Glen H. et al. Lenvatinib, everolimus, and the combination in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, phase 2, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(15): 1473–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM. et al. Sorafenib for treatment of renal cell carcinoma: final efficacy and safety results of the phase III treatment approaches in renal cancer global evaluation trial. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 3312–3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P. et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 3584–3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S. et al. Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer 2010; 116: 4256–4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Tomczak P. et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as second-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: overall survival analysis and updated results from a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(6): 552–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D. et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 722–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.