Abstract

Background:

Changing epidemiologic profile with increase in cardiovascular risk factors is well documented in literature. Our study sought to see how this is reflected in cardiovascular admissions into medical wards of a Nigerian and an Israeli hospital.

Objective:

To compare the range and pattern of cardiovascular admissions encountered in a Nigerian hospital and an Israel hospital.

Methods:

This was a retrospective study of admission records of patients admitted into both Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Umuahia, Abia State, Nigeria, and Sheba Medical Centre, Israel.

Results:

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) was the most prevalent among the Israeli hospital's admissions but ranks very low as an indication for admission in Nigeria. The most common causes of admission in Nigeria were hypertension and heart failure (HF). The spectrum of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) was very limited in the Nigerian hospital, indicating disparity in diagnostic capacity.

Conclusion:

There were more patients with CVD as a cause of medical admission in the Israel hospital as compared to the Nigerian hospital. Hypertension and HF were prevalent indications for CVD in FMC, Umuahia, Nigeria, while hypertension and IHD were the prevalent indications for admission in Sheba Medical Centre, Israel. Future studies are needed to monitor spectrum and frequency of cardiovascular admissions in view of evolving epidemiological transition in developing countries.

Keywords: Cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, ischemic heart diseases, Israel, Nigeria, Maladie Cardio-vasculaires, hypertension, Défaillance Cardiaque Ischémique, Israël, Nigeria

Résumé

Arrière-plan:

Le changement du profil épidémiologique avec l’augmentation du risque cardiovasculaire a été bien documenté dans la littérature. Notre étude a pour but d’observer comment ceci est démontré dans l’hospitalisation cardiovasculaire dans les salles d’hôpital nigérian et Ismaélien.

Objectif:

comparer le nombre et le pattern des hospitalisations des maladies cardiovasculaires enregistrées dans les hôpitaux nigérians et ismaéliens.

Méthode:

c’est une étude rétrospective du registre des patients hospitalisés dans deux centres médicaux à savoir: Centre Médical Fédéral (CMF), Umuahia, Abia, Nigeria et le Centre Médical de Sheba, Israël.

Résultat:

la Maladie Cardiaque Ischémique (MCI) était le plus prévalent parmi les patients dans les hôpitaux israéliens mais reste bas dans les cas d’hospitalisation dans les hôpitaux Nigérian. La cause d’hospitalisation le plus commun au Nigeria était l’hypertension et la Défaillance Cardiaque (DC). Le spectre des Maladies Cardiaques (MC) est très bas dans les hôpitaux Nigérian; Ceci montre la disparité de la capacité diagnostique.

Conclusion:

Il y a beaucoup de patients avec MCV comme cause d’hospitalisation en Israël par rapport au Nigeria. L’hypertension et le DC sont des indications prévalents pour le MCV à CMF, Umuahia, Nigeria, tandis que l’hypertension et le MCI sont des indications prévalent pour l’hospitalisation au Centre Médical de Sheba, Israël. Les études futures sont nécessaires pour contrôler le spectre et la fréquence des hospitalisations cardiovasculaires, en vue d’évoluer la transition épidémiologique dans les pays en voie du développement.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are important medical and public health issues throughout the world. This is a bigger problem for developing countries like Nigeria which face the dual menace of high prevalence of communicable diseases as well as an increasing burden of noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular illnesses.[1,2]

The incidence of CVDs in developing countries has been on the increase in the last few years.[3] This rise has been attributed to demographic changes, urbanization, lifestyle modifications, and high-risk factors such as obesity, dyslipidemias, diabetes mellitus, hypertension.[3]

Between 1990 and 2020, the rise in mortality due to ischemic heart diseases (IHDs) in developing countries (137% men, 120% women) is predicted to be much higher than that in the developed countries (48% men, 29% women).[4] It is also projected that in the next 15 years, CVDs will become the leading cause of death in developing countries.

Epidemiological data on cardiovascular disorders are generally lacking in the developing nations. However, various hospital-based studies that show the pattern of CVDs have been documented in some regions. In a study of the pattern of medical admissions within a 5-year period (December 1998–November 2003) at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu, Nigeria, among 7399 patients admitted, CVDs accounted for 18.8% with 53% within ages 30–60 years, with male and female ratio of 1.4:1.[5] Furthermore, in Nigeria, Ansa et al.[6] reported 19.9% prevalence of cardiovascular admissions in the University of Uyo Teaching Hospital. In recent years, studies have examined the pattern of admissions to medical wards in various countries,[7,8] but comparison between two countries with different social, economic, and health indices is scarce in the literature. Hence, we studied the indications, frequencies, and distribution of cardiovascular admissions into medical wards of Sheba Medical Centre, Israel, and Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Umuahia, Nigeria, and compared the results.

Sheba Medical Centre is a tertiary health care institution in Israel. It is a 1700-bedded and the largest hospital in the Middle East. It has about 6000 health professionals, of which 850 are doctors and 2000 are nurses. It handles about 4 million patients annually and has 120 departments. Division of Internal Medicine in this hospital has 266 beds for inpatients and 72 day beds for outpatients.

FMC, Umuahia, is a tertiary health care institution situated in Umuahia, the capital city of Abia State of Nigeria. It was founded on March 24, 1956, and was named Queen Elizabeth Hospital after the Queen of England, and subsequently made an FMC. It is a medium-sized 405-bedded hospital with 80 beds in the medical wards.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study, in which we collected data on admissions with CVDs into the medical wards of FMC, Umuahia, over a 4-year period (January 2005–December 2008) using the register of admissions and discharges in both male and female medical wards, as well as a review of the patients’ case files where necessary.

A retrospective survey of cardiovascular admissions in the medical wards of the Sheba Hospital was undertaken for 2006 and 2007 using ward record books. Information retrieved included age, diagnosis, and year of admission. Records of all patients with cardiovascular admissions were retrieved and included in the study while those with incomplete data were excluded from the study.

Ethical clearance was obtained for the study. Data obtained were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16 (International Business Machines (IBM) Corporation, New York USA). Tables were used for descriptive analysis. A P < 0.05 was taken to be statistically significant.

Results

There were 700 cardiovascular admissions in the 4-year period in FMC, Umuahia, which constituted 20.1% of all (3483) medical admissions.

There were 22,264 cardiovascular admissions to Sheba Medical Centre over the 2-year period, which constituted 41.2% of all their medical admissions with an annual average of 27,020.

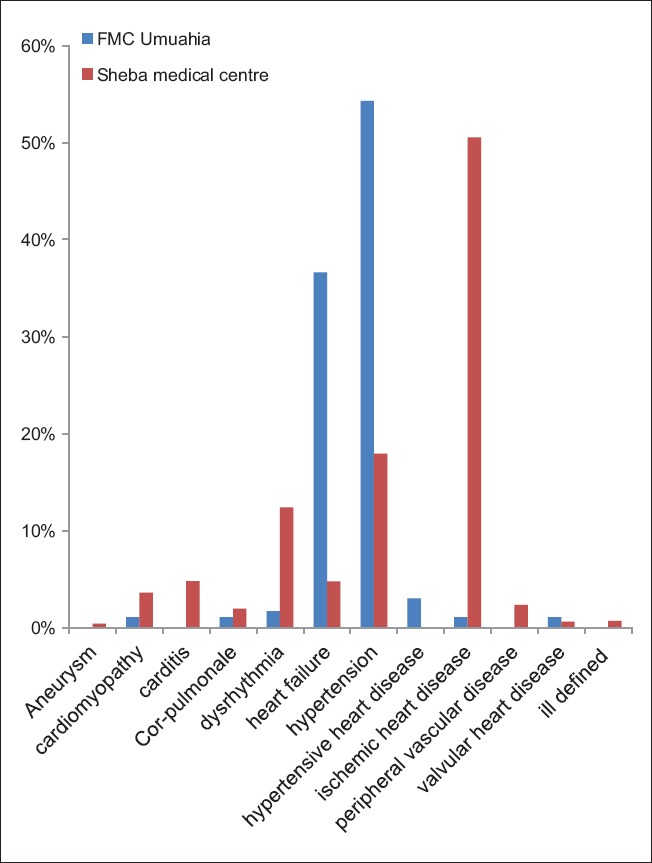

The age distribution studied in FMC, Umuahia, and Sheba Medical Centre is as shown in Table 1. In Sheba, the indications were more precise and of wider spectrum (up to 79 indications). These indications have been grouped and compared with the admissions in FMC, Umuahia, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Age distribution of cardiovascular admissions

| Age (years) | Frequency (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FMC, Umuahia, Nigeria | Sheba Medical Centre, Israel | ||

| 15-34 | 64 (9.1) | 334 (1.5) | 0.001* |

| 35-50 | 140 (20) | 4430 (19.9) | 0.946 |

| 51-74 | 357 (51) | 11,778 (52.9) | 0.321 |

| ≥75 | 139 (19.9) | 5722 (25.7) | 0.0004* |

| Total | 700 (100) | 22,264 (100) | |

*Statistically significant. FMC=Federal Medical Centre

Table 2.

Yearly average number of cardiovascular disease admissions (Umuahia vs. Sheba)

| Cardiovascular disease | Frequency (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FMC, Umuahia | Sheba Medical Centre | ||

| Aneurysm | 0 | 49 (0.41) | 1# |

| Cardiomyopathy | 2 (1.10) | 431 (3.58) | 0.0965# |

| Carditis | 0 | 577 (4.79) | 0.0004#,* |

| Cor-pulmonale | 2 (1.10) | 238 (1.96) | 0.5888# |

| Dysrhythmia | 3 (1.7) | 1493 (12.39) | 0.0001#,* |

| Heart failure | 64 (36.6) | 573 (4.76) | 0.0001* |

| Hypertension | 95 (54.3) | 2160 (17.93) | 0.001* |

| Hypertensive heart disease | 5 (3) | 3 (0.03) | 0.001#,* |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2 (1.1) | 6090 (50.5) | 0.0001* |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0 | 282 (2.34) | 0.0365#,* |

| Valvular heart disease | 2 (1.1) | 72 (0.6) | 0.2862# |

| Ill-defined cardiovascular disease | 0 | 81 (0.67) | 0.6331# |

| Total | 175 (100) | 12,049 (100) | |

#Fisher’s exact P value, *Significant association. FMC=Federal Medical Centre

Figure 1.

Frequencies (%) of CVD admissions in Umuahia Vs Sheba

Discussion

This study provides insight into the differences in cardiovascular admissions between a developed and a developing country. The spectrum of cardiovascular conditions is limited in the data from FMC, Umuahia. This was due to comparative deficiency in specialization and investigative technology at the Nigerian center. In particular, this study was done at a time when echocardiography, a very helpful tool in ascertaining precise diagnosis of various cardiac conditions, was not domiciled in FMC, Umuahia, but could be accessed in nearby diagnostic facilities.

In both centers, age group most affected was 51–74 years, 51.2% for Umuahia and 52.9% for Sheba. Number of admissions of patients ≥75 years was significantly more in Sheba than in Umuahia. This may be because of increased life expectancy in Israel compared to Nigeria.[9]

In FMC, Umuahia, CVDs constituted 20.1% of all medical admissions. This prevalence compares well with other studies done in different parts of Nigeria: 18.8% in Enugu, South-east Nigeria,[5] 19.9% in Uyo, South Nigeria,[6] 17.4% Abeokuta, Southwest Nigeria,[10] and 14.1%–24.2% in Northern Nigeria.[11] The prevalence of 8% reported in Kaduna (Northern Nigeria)[12] was in the 1970s before the increasing trend in CVD burden in the developing nations was recorded. This trend has been documented in Nigeria and other developing nations.[11,13,14,15]

The prevalence of 41.2% in Sheba Medical Centre should reflect that of the country, considering the size of this hospital, in comparison to Israeli population of 7.8 million. Similar prevalence is found in other developed countries.[16] This suggests that the burden of CVD admissions in Israel (a developed country) is more than in Nigeria (a developing country).

Most prevalent indications for cardiovascular admissions in FMC, Umuahia, were hypertension high blood pressure (HBP) 54.6% and heart failure (HF) 36.8%. This agrees with majority of works done in Nigeria. Reports obtained in various Nigerian centers were as follows: Abeokuta, Southwest - HBP 49.5%, HF 44.9%;[10] Ile-Ife, Southwest - HBP 32%, HF 35%;[17] Uyo, South-south - HBP 55.7%, HF 44.9%;[6] North - HBP 39.1% was most prevalent in North-west. Most prevalent indication for CVD admissions in Sheba was IHD - 54.8% and hypertension - 19.4%. Similar pattern is seen in most developed countries.[18]

Considering the epidemiologic transition going on in developing countries, follow-up studies are needed, especially as many workers have documented significant increase in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in developing countries.[19,20,21,22,23] This may soon translate into increase and changes in spectrum of cardiovascular admissions.

Conclusion

There were more patients with CVD as a cause of medical admission in Israel compared with Umuahia, Nigeria. The most prevalent indication for cardiovascular admission in Nigeria (a developing country) was hypertension and HF while in Israel (a developed country), they were IHD and hypertension. Efforts made toward optimal control of hypertension and lifestyle modification will go a long way in reducing the burden of cardiovascular admissions.

Future studies are needed to monitor the spectrum and frequency of cardiovascular admissions in view of the epidemiological transition changing epidemiological profile.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Prof. Hanoch Hod, Director of Intensive Cardiac Care Unit, Sheba Medical Centre, Israel, for granting permission for release of Sheba data.

References

- 1.BeLue R, Okoror TA, Iwelunmor J, Taylor KD, Degboe AN, Agyemang C, et al. An overview of cardiovascular risk factor burden in sub-Saharan African countries: A socio-cultural perspective. Global Health. 2009;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. The World Health Report-Reduction Risks, Promoting Healthy Lifestyle. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omran AR. The Epidemiological Transition: A Theory of the Epidemiology of Population Change. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 04]. Available from: http://www.milbank.org/quarterly/830418omran.pdf .

- 4.Agyemang C, Addo J, Bhopal R, de Graft Aikins A, Stronks K. Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetes and Established Risk Factors among Populations of Sub-Saharan African Descent in Europe: A Literature Review. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 04]. Available from: http://www.globalizationandhealth.com/content/5/1/7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ike SO. The pattern of admissions into the medical wards of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu (2) Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11:185–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ansa VO, Ekott JU, Bassey EO. Profile and outcome of cardiovascular admissions at the University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo – A five year review. Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11:22–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali E, Woldie M. Reasons and outcomes of admissions to the medical wards of Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Southwest-Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2010;20:113–20. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v20i2.69437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor IC, McConnell JG. Patterns of admission and discharge in an acute geriatric medical ward. Ulster Med J. 1995;64:58–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Global health observatory data repository: Life expectancy-data by country. World Health Statistic. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogah SO, Akinyemi RO, Adetutu A, Ogbodo EI. Analysis of medical admissions at the emergency unit of FMC, Abeokuta: A 2 year review. Afr J Biomed. 2012;15:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulcadus AO, Misbau U. Incidence and pattern of cardiovascular disease in North-west Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2009;50:55–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abengowe CU. Cardiovascular disease in Northern Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1979;31:553–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy KS. Cardiovascular diseases in the developing countries: Dimensions, determinants, dynamics and directions for public health action. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:231–7. doi: 10.1079/phn2001298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lore W. Epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases in Africa with special reference to Kenya: An overview. East Afr Med J. 1993;70:357–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ntusi NB, Mayosi BM. Epidemiology of heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2009;7:169–80. doi: 10.1586/14779072.7.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, Rayner M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: Epidemiological update. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2950–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adedoyin RA, Adesoye A. Incidence and pattern of cardiovascular disease in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Trop Doct. 2005;35:104–6. doi: 10.1258/0049475054037075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mensah GA, Brown DW. An overview of cardiovascular disease burden in the United States. Health Aff. 2007;26:38–48. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ejim EC, Okafor CI, Emehel A, Mbah AU, Onyia U, Egwuonwu T, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the middle-aged and elderly population of a Nigerian rural community. J Trop Med 2011. 2011:308687. doi: 10.1155/2011/308687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ike SO, Arodiwe EB, Onoka CA. Profile of cardiovascular risk factors among priests in a Nigerian rural community. Niger Med J. 2007;48:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulasi II, Ijoma CK, Onodugo OD. A community-based study of hypertension and cardio-metabolic syndrome in semi-urban and rural communities in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:71–6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sani MU, Wahab KW, Yusuf BO, Gbadamosi M, Johnson OV, Gbadamosi A. Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors among apparently healthy adult Nigerian population – A cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2010;20:3–11. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawoyin TO, Asuzu MC, Kaufman J, Rotimi C, Owoaje E, Johnson L, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in an African, urban inner city community. West Afr J Med. 2002;21:208–11. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v21i3.28031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]