Abstract

Ameloblastoma is the most known of the epithelial odontogenic benign tumor. It is slow growing and locally aggressive in nature and most commonly seen in the posterior mandible. Various histopathological variants exist, among which acanthomatous type of ameloblastoma is one of the rarest types. Acanthomatous ameloblastoma is usually seen in older aged human population and most commonly reported in canine region of dogs in literature. Here, we report a rare case of acanthomatous ameloblastoma in a young male patient involving mandibular anterior region crossing the midline with recurrence over a period of 2 years of follow-up after surgical resection.

Keywords: Acanthomatous ameloblastoma, benign odontogenic tumor, recurrence, Ameloblastome acanthomateux, récurrence, tumeur odontogène bénigne

Résumé

L’améloblastome est la plus connue de la tumeur bénigne odontogénique épithéliale. Il est de croissance lente et de nature localement agressif et la plupart Communément vu dans la mandibule postérieure. Diverses variantes histopathologiques existent, dont le type d’améloblastome acanthomateux est L’un des types les plus rares. L’ameloblastome acanthomateux est habituellement observé chez les personnes âgées âgées et le plus souvent signalé chez les canins Région des chiens en littérature. Ici, nous signalons un cas rare d’ameloblastome acanthomateux chez un jeune malade impliquant un antérieur mandibulaire Région traversant la ligne médiane avec récurrence sur une période de 2 ans de suivi après résection chirurgicale.

Introduction

Many benign tumors of the orofacial region cause swellings which are either of odontogenic or nonodontogenic in origin. Of many, the most common benign odontogenic tumor is ameloblastoma and is described for the first time by Broca in 1868 as adamantinoma and then recoined by Churchill in 1934.[1] Higher incidence of occurrence is reported in the mandibular molar-ramus region of about 70% than maxilla by the ratio of 5:1, and it accounts for 1% of all cysts/tumors of jaws and 18% of all odontogenic neoplasms.[2] Average age reported is in the third to fifth decade of life with no sex predilection when the tumor is not associated with an unerupted tooth; the gender ratio is male to female ratio of 1:1.8.[3] According to the current World Health Organization classification of odontogenic tumors, ameloblastomas are divided into four types: solid/multicystic, extraosseous/peripheral, desmoplastic, and unicystic. Various histologically subtypes have been described, including those of follicular, plexiform, acanthomatous, granular, and basal cells. Most literatures showed that follicular ameloblastoma is the most prevalent histological variant (64.9%) followed by the plexiform (13.0%), desmoplastic (5.2%), and acanthomatous (3.9%) varieties.[4,5] This case report presents a distinctive occurrence of acanthomatous ameloblastoma in a young male patient crossing the midline of the anterior mandible, which is the rarest case reported.

Case Report

An 18-year-old male patient reported to the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology with a chief complaint of swelling in his lower front region of the jaw for 4 months. The patient gave a history of swelling which is gradually increasing in size to the present. No history of pain, trauma, or any discharge from the swelling was elucidated.

On extraoral examination, a diffuse swelling was seen over the chin region extending from the left angle of mouth crossing midline to the right of the angle of mouth, measuring approximately 4 cm × 3 cm in size with obliteration of the mentolabial sulcus [Figure 1]. On palpation, swelling was nontender, with movable overlying skin, soft in consistency, and crepitus was felt over the chin region.

Figure 1.

Extraoral preoperative photograph

On intraoral examination, obliteration of the lower labial vestibule and alveolingual sulcus extending from teeth 36 to 45, crossing the midline and superior-inferiorly from the attached gingiva to depth of the labial and buccal vestibule measuring approximately 5 cm × 3 cm in size. Displacement of the teeth anteriomesially in relation to 41, 42 and anteriodistally in relation to 31 was seen [Figure 2]. On palpation, crepitus was felt on labial vestibule in relation to teeth 34, 35, 33, 32, 42, 43, 44, and 45 with nontender swelling and soft in consistency.

Figure 2.

Intraoral view

Pulp vitality test was performed in relation to teeth 35–45 and delayed response was noted. A clear yellow-colored fluid was obtained upon aspiration [Figure 3]. Based on patient history, clinical examination, and chairside investigations, benign odontogenic tumor was considered as provisional diagnosis. Differential diagnosis includes radicular cyst, ameloblastoma, odontogenic keratocyst, central giant cell granuloma, and odontogenic myxoma.

Figure 3.

Yellow-colored clear aspiration fluid

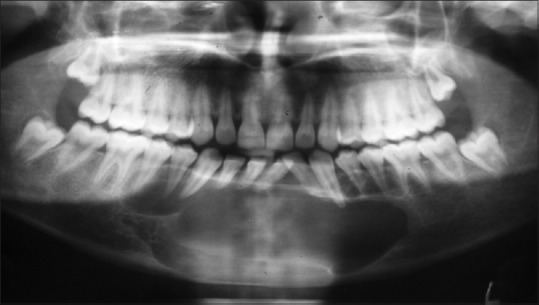

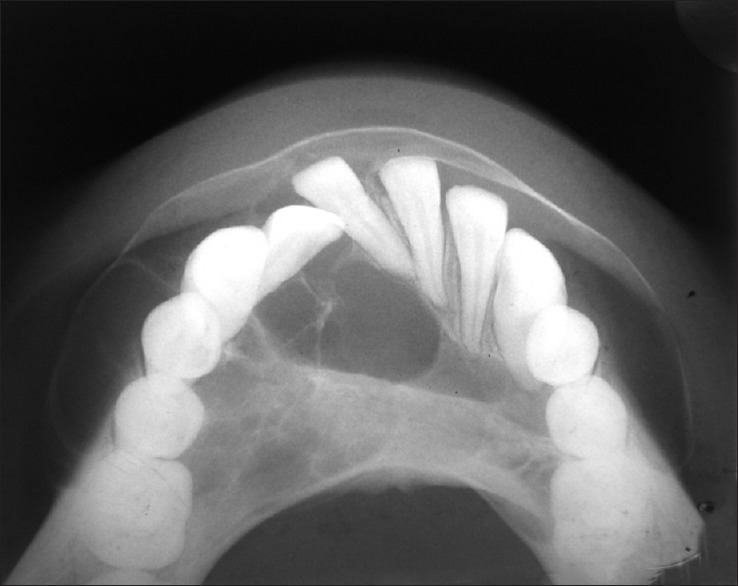

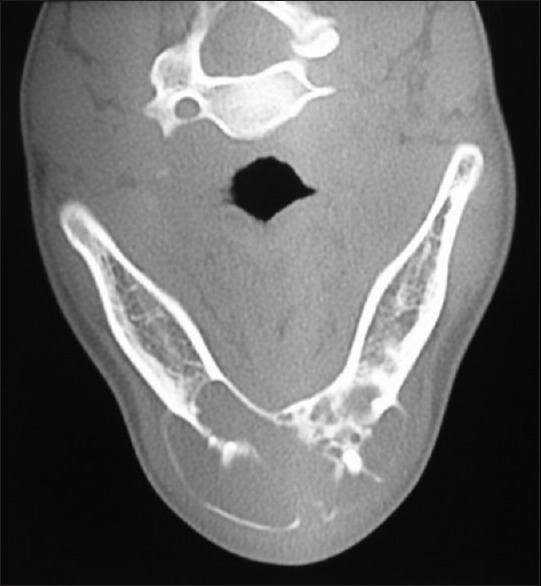

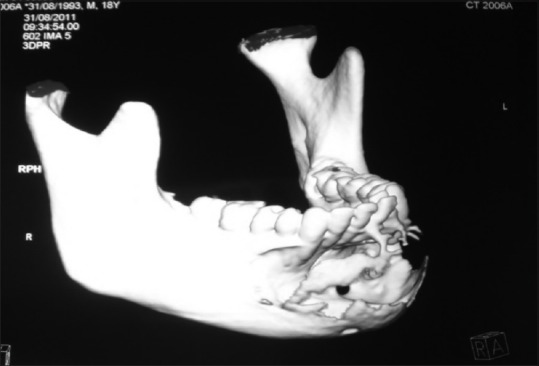

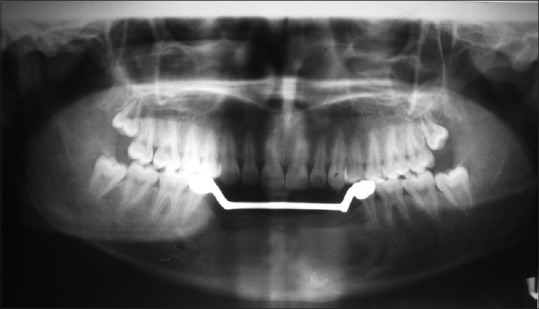

Further investigations were performed such as orthopantomograph (OPG), occlusal anterior mandibular view, computed tomography (CT) scan, and incisional biopsy. OPG interpretation revealed well-defined multilocular radiolucent area with corticated borders and internal septa giving appearance of soap bubble extending from the mesial root of tooth 35 to mesial root of tooth 45 involving midline with root resorption of apical one-third in relation to teeth 33, 32, 31, 41, 42, and 43 and displacement of teeth 31 and 32 [Figure 4]. Anterior occlusal mandibular view revealed expansion of the buccal/labial and lingual cortical plates from the tooth 36 region crossing the midline up to the tooth 46 region, with the presence internal septa in relation to teeth 46, 45, 44, and 43 regions and with a very thin corticated boundary [Figure 5]. CT scan showed an expansile osteolytic radiolucent lesion in the anterior mandible, with expansion and thinning of lingual cortical plate and expansion and break in the continuity of labial cortical plate [Figures 6–8]. Radiological differential diagnosis includes ameloblastoma, central giant cell granuloma, and odontogenic myxoma.

Figure 4.

Orthopantomograph

Figure 5.

Anterior mandibular occlusal view

Figure 6.

Axial view of computed tomography scan

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional computed tomography scan

Figure 7.

Coronal view of computed tomography scan

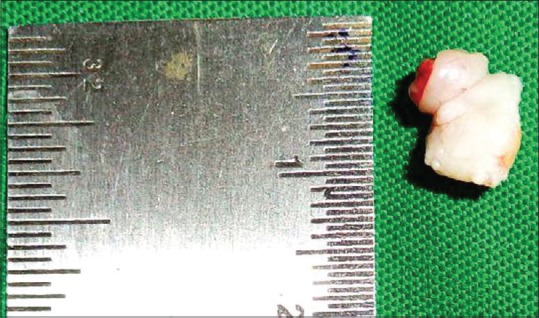

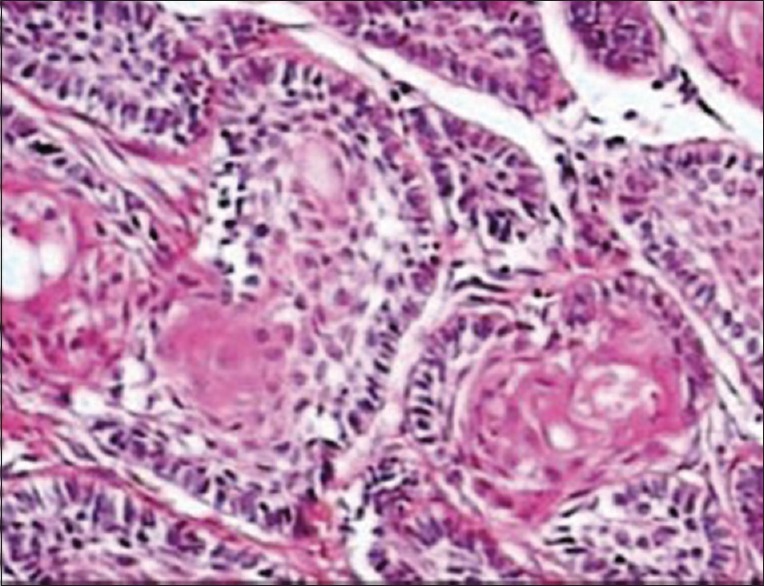

Incisional biopsy was performed later [Figure 9], and histopathological features showed periphery of the follicle which was lined by a single layer of tall columnar ameloblast like cells, and central region showed loosely arranged polygonal or angular cells resembling stellate reticulum. Many solid epithelial cell nests also showed squamous differentiation with well-formed keratin pearls suggestive of acanthomatous ameloblastoma [Figure 10].

Figure 9.

Incisional biopsy

Figure 10.

Histopathology

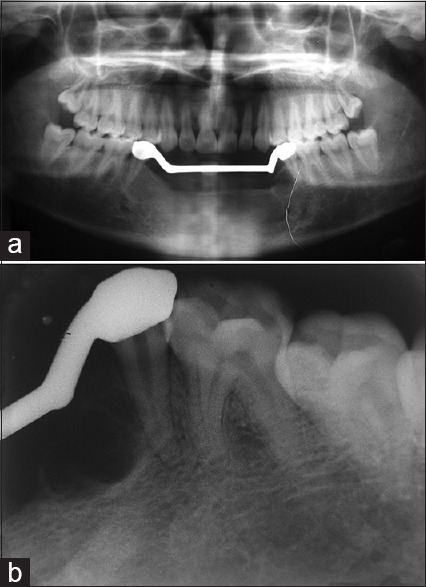

After obtaining the consent from the patient, surgical resection of the anterior mandible with wide normal margins followed by reconstruction with iliac cancellous bone was done. Satisfactory postoperative healing was noted, and replacement with fixed-removable prosthesis was delivered to the patient [Figures 11–13]. After 2 years of follow-up period, OPG and intraoral periapical radiograph [Figure 14a and b] were taken, which revealed satisfactory healing of the resected area. However, a well-defined radiolucency in the edentulous region adjacent to the tooth 34 was noted, which may be a sign of recurrence and was scheduled for further treatment.

Figure 11.

Postoperative follow-up intraoral view

Figure 13.

Postoperative orthopantomograph

Figure 14.

(a and b) Two-year follow-up orthopantomograph and intraoral periapical radiograph

Figure 12.

Postoperative follow-up with fixed-removable prosthesis

Discussion

Ameloblastoma is usually asymptomatic and found on routine dental X-rays; however, they present with jaw expansion. It is slow but relentless growth may cause movement of tooth roots or root resorption as seen in our case, loose teeth, malocclusion, or more rarely paresthesia and pain.[6]

Average age reported is in the third to fifth decade of life, whereas acanthomatous ameloblastoma as reported to occur mostly in the seventh decade of life.[7,5] Unlike the present case, the most common site of occurrence is in the mandible (80% of ameloblastomas) with 70% are located in the area of the molars or the ascending ramus,[7,8] whereas the present case was reported, with occurrence in the mandibular anterior region crossing midline and displacing anterior teeth, which is the rarest reported human case in literature.

Radiographic features of ameloblastoma most commonly appear as radiolucent, unilocular/multiloculated cystic lesion, with a characteristic “soap bubble-like” appearance, cortical thinning/destruction with local invasion, and root resorptions.[3] These characteristic radiographic features are evident in our present case.

Ameloblastomas have been classified in both human and veterinary literature[9] and have been defined as benign, locally invasive, and clinically malignant lesions. Metastasis has been documented only in humans as malignant ameloblastomas and ameloblastic carcinomas have been noted to metastasize to the lungs, pleura, orbit, skull, and brain but not in dogs.[9] Adebiyi et al. reported histopathological types that the most of the solid lesions belonged to follicular ameloblastoma (64.9%) followed by the plexiform (13.0%), desmoplastic (5.2%), and acanthomatous (3.9%).[5] Histopathologically, acanthomatous type shows central squamous cell differential with keratin formation as seen in the present case. Some authors stated that formation of squamous metaplasia may be due to chronic irritation of calculus and oral sepsis.[10] Treatment modality varies depending on the type of ameloblastoma diagnosed as unicystic/multicystic.[8,11] Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for most of the solid/multicystic ameloblastomas. The recurrence rate reported in the literature is 13%–15% for surgical resection and 90%–100% for curettage.[8] Follow-up of the patient is utmost essential as the chance of recurrences present within the first 5 years,[11] which is as seen in our case after a period of 2 years. Some authors also believe that high chance of the acanthomatous variant turning into metastasizing squamous cell carcinoma, if left untreated. There are controversies about the biological behavior of the acanthomatous ameloblastoma; some researchers believe that it is locally aggressive and frequently invades the alveolar bone or recurs after marginal surgical excision as it was reported in our present case. Some others believe that there is no difference among the various subtypes of ameloblastoma.[12,13] Thus, the study of molecular mechanisms of cell proliferation can be helpful to predict the aggressiveness of ameloblastoma and especially p16 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor) which is a tumoral suppressor protein encoded by the CDKN2A gene. A high score in the immunoexpression of the p16 protein may indicate lower aggressiveness and a lower rate of recurrence.[14]

Conclusion

Although ameloblastoma is a most common benign tumor, the incidence of occurrence of acanthomatous ameloblastoma is very rare in human beings. To our knowledge, very few cases of acanthomatous type of ameloblastomas are reported in elderly aged patients occuring in mandibular posterior region, and cases of this type of ameloblastomas in younger aged patients (second decade) occurring in the anterior mandibular region crossing midline with recurrence over a period of time are not reported in the literature. Hence, further study of molecular mechanism and implication in clinical practice has to be considered.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 5th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2008. pp. 323–56. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP, Sonner S. Ameloblastoma: Biological profile of 3677 cases. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1995;31B:86–99. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(94)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Odontogenic cysts and tumors. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO, USA: WB Saunders; 2002. pp. 610–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. p. 284. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adebiyi KE, Odukoya O, Taiwo EO. Ectodermal odontogenic tumours: Analysis of 197 Nigerian cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:766–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendenhall WM, Werning JW, Fernandes R, Malyapa RS, Mendenhall NP. Ameloblastoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:645–8. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181573e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varkhede A, Tupkari JV, Mandale MS, Sarda M. Plexiform ameloblastoma of mandible: Case report. J Clin Exp Dent. 2010;2:e146–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vohra FA, Hussain M, Mudassir MS. Ameloblastomas and their management: A review. J Surg Pak (Int) 2009;14:136–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly JM, Belding BA, Schaefer AK. Acanthomatous ameloblastoma in dogs treated with intralesional bleomycin. Vet Comp Oncol. 2010;8:81–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2010.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bansal M, Chaturvedi TP, Bansal R, Kumar M. Acanthomatous ameloblastoma of anterior maxilla. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2010;28:209–11. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.73797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong J, Yun PY, Chung IH, Myoung H, Suh JD, Seo BM, et al. Long-term follow up on recurrence of 305 ameloblastoma cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:283–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anneroth G, Anders H, Jan W. Acanthomatous ameloblastoma. Int J Oral Surg. 1980;9:231–6. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(80)80024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh G, Agarwal R, Kumar V, Passi D. Acanthomatous ameloblastoma - A case report. J Int Oral Health. 2013;5:54–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olimid DA, Florescu AM, Cernea D, Georgescu CC, Margaritescu C, Simionescu CE, et al. The evaluation of p16 and Ki67 immunoexpression in ameloblastomas. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:363–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]