Abstract

Magnetite nanoparticles (Fe3O4) represent the most promising materials in medical applications. To favor high-drug or enzyme loading on the nanoparticles, they are incorporated into mesoporous materials to form a hybrid support with the consequent reduction of magnetization saturation. The direct synthesis of mesoporous structures appears to be of interest. To this end, magnetite nanoparticles have been synthesized using a one pot co-precipitation reaction at room temperature in the presence of different bases, such as NaOH, KOH or (C2H5)4NOH. Magnetite shows characteristics of superparamagnetism at room temperature and a saturation magnetization (Ms) value depending on both the crystal size and the degree of agglomeration of individual nanoparticles. Such agglomeration appears to be responsible for the formation of mesoporous structures, which are affected by the pH, the nature of alkali, the slow or fast addition of alkaline solution and the drying modality of synthesized powders.

Keywords: magnetite nanoparticles, co-precipitation, room temperature, superparamagnetism, aggregation, mesoporous structure

1. Introduction

Magnetite nanoparticles have applications in several areas, such as biomedical [1,2,3], target drug delivery [4], tumor and cancer diagnosis and treatment [5] and as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrasting agent [6,7]. These medical applications require superparamagnetic magnetite with particle sizes smaller than 20 nm [8].

Magnetite adsorbs oxygen to form maghemite, which, in turn, loses its susceptibility with time [9]. On the other hand, the nanosized particles form less stable systems from the colloidal point of view, determining their agglomeration. In the case of magnetic fluids, to prevent agglomeration, the surface coating of a particle is essential for having stable colloidal dispersion in a wide pH range [10,11]. In addition, the adsorption layer can also enhance the resistance against oxidation of magnetite into maghemite (γ-F2O3).

The applications of magnetite nanoparticles depend on the preparation method, which, in turn, influences particle size and shape, size distribution, agglomeration and the surface chemistry of the material.

The magnetite can be synthesized by various methods, including: ultrasound irradiation [12], sol-gel [13], thermal decomposition [8,14,15,16,17,18] and co-precipitation [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Thermal decomposition and co-precipitation are most commonly used. The thermal decomposition route relies on the pyrolysis of organic precursors of iron, such as Fe(CO)5 [14,15] and Fe(acac)3 [8,16,17,18]. However, Fe(CO)5 and Fe(acac)3 are toxic and may limit the application of magnetite for medical applications. Recently, a one pot synthesis of magnetite by thermal decomposition of [Fe(CON2H4)6](NO3)3 [26] was reported. Co-precipitations based on the hydrolysis of a mixture of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions are used to fix the A to B molar ratio in the inverse spinel structure. Generally, the reaction is performed under an inert (N2 or Ar) atmosphere using degassed solutions to avoid uncontrollable oxidation of Fe2+ into Fe3+ [24]. In this method, Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions are generally precipitated in alkaline solutions, such as ammonium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide or sodium hydroxide. In most cases, the syntheses are performed at 70–80 °C [25] or higher temperatures. The effects of mixing methods [20], stirring rate [27], digestion time [28], initial pH [29] and the presence or absence of a magnetic field [19,30] on particle size, morphology and resulting magnetic properties were also discussed. Co-precipitation methods performed under various precipitation conditions were also reported. For example, when only Fe2+ was used for precipitation, then H2O2 [19,20] or NaNO2 [21] were adopted to partially oxidize Fe2+ into Fe3+ in the precipitated product. When only Fe3+ was used for precipitation, then Na2SO3 [22] partially reduces ferric to ferrous ion in the precipitation product. Some co-precipitation methods are performed in the presence of polymers [23], including: polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and dextran to prevent both agglomeration and/or oxidation of the nanoparticles. All these co-precipitation methods are comparatively complex and require strict control of precipitation conditions.

The magnetic properties of magnetite nanoparticles strongly depended on the synthesis route. In particular, size determines the magnetite properties [31,32]. The saturation magnetization can be most likely affected by several features, such as the spin disorder layer [33], that increase with a decrease in crystallite size.

Other factors include the finite size effect, the incomplete crystallization of magnetite, irregular morphologies of magnetite particles [34] and the magnetostatic interaction responsible for the agglomeration of magnetite particles [35].

The synthesis of mesoporous structures of magnetite appears of interest, because the presence of mesopores favors high drug or enzyme loading of magnetite for medical application. To this end, a cheap coprecipitation method of synthesis is proposed. The main objective of this work concerns the formation of mesoporous structures by agglomeration of magnetite nanoparticles.

Alkaline solutions containing stoichiometric or excesses of NaOH, KOH or (C2H5)4NOH, respectively, were used. Because many of the coprecipitation methods are performed at elevated temperatures [25], to evaluate the effect of temperature on the synthesis magnetite, a computer software, developed by OLI Systems, Inc. (Morris Plains, NJ, USA), was also used.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and Equipment

The chemicals used, FeCl3·6H2O, FeCl2·4H2O, NaOH, KOH and (C2H5)4NOH, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. To avoid the formation of both maghemite, γ-Fe2O3, and hematite, α-Fe2O3, all the syntheses were performed under oxygen-free conditions.

Two series of samples have been prepared: the first one by slow addition, 1.0 mL/min, of the alkaline solution into the reaction solution, whereas the second series was obtained by a fast addition of the alkaline solution to the reaction solution. A precision pump operating at a flow rate of 1.0 ± 0.1 mL/min was used for the addition of reactants to the reaction vessel. In order to evaluate the effect of both temperature and pH on the magnetite synthesis, the OLI (SLA) software, was used. In this software, solution equilibria account for all solution complexes and the solubility of various solids, simultaneously. Table 1 gives a list of solution complexes and solids phases. The solutions are non-ideal, with activity coefficients being calculated for each species in solution using extended the Debye–Hückel theory.

Table 1.

Solution complexes and solid phases in equilibria calculations.

| Solid Phases | Solution Complex Species | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe(OH)2 | FeCl2 | OH− | [FeCl2]+ |

| Fe(OH)3 | FeCl3 | Fe2+ | [Fe(OH)2]+ |

| NaCl | HCl | Fe3+ | [FeCl]2+ |

| FeCl2·4H2O | Aqueous Fe(OH)3 and Fe(OH)2 precipitation precursors | [FeCl]+ | [Fe(OH)]2+ |

| FeCl2 | Cl− | [FeOH]+ | [FeCl4]− |

| NaOH·H2O | [Fe2(OH)2]4+ | [Fe(OH)4]2− | [Fe(OH)4]− |

| FeCl3·6H2O | H+ | [Fe(OH)3]− | Na+ |

The solution conditions used for this analysis are 0.1 mol/L FeCl3, 0.05 mol/L FeCl2 in deionized water and various NaOH concentrations to give various pH values at equilibrium. Solution equilibria are calculated for different temperatures from 0 to 100 °C at one atmosphere total pressure.

2.2. Synthesis

Fe3O4 was synthesized in alkaline conditions using different bases, BOH, with B = Na+, K+ or (C2H5)4N+, to complete the following overall reaction:

| 2FeCl3 + FeCl2 + 8BOH → Fe3O4 (s) + 4H2O + 8BCl | (1) |

To investigate the effect of pH value on the properties of magnetite nanoparticles, the experiments were carried out at various BOH amounts. During the reaction, the reaction flask was equipped with a pH meter to measure the final pH value. The experimental parameters for the synthesis of magnetite nano-particles are summarized in Table 2. The coprecipitation of iron ions has been performed either with stoichiometric or with an excesses of BOH solution, adopting a slow (S) or a fast (F) addition of the precipitating alkaline solution.

Table 2.

Experimental parameters.

| Sample | FeCl3·6H2O (mol) | FeCl2·4H2O (mol) | BOH (mol) | Final pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.08 (NaOH) ** | 10.34 |

| S2 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.085 (NaOH) | 11.94 |

| S3 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 (NaOH) | 12.08 |

| S4 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.095 (NaOH) | 12.20 |

| S5 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.1 (NaOH) | 12.60 |

| F1Na | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.08 (NaOH) ** | 9.4 |

| F3Na | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 (NaOH) | 10.7 |

| F5Na | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.1 (NaOH) | 11.8 |

| F3K | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 (KOH) | – |

| F3TEA | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 (TEAOH) | – |

| * F3TEA | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 (TEAOH) | – |

* Fast and reverse addition of solution containing ferric and ferrous ions into the TEAOH-containing solution; ** stoichiometric amount of base.

In a typical experiment (S1 sample), 0.01 mol FeCl2∙4H2O and 0.02 mol FeCl3∙6H2O were dissolved in 100 mL degassed deionized water and added into a 250 mL three-neck flask, which was immersed in a room temperature (25 °C) water bath. Point-zero-eight moles of NaOH were dissolved in 100 mL degassed deionized water. The reaction solution was mechanically stirred at 500 rpm while nitrogen gas flowed into the flask. After charging of the reactor with NaOH was completed, stirring continued for 3 h, after which the final pH was recorded. After this reaction time, the solution was decanted, allowing the particles to be washed with degassed deionized water. This procedure was repeated three times, and then, the particles were separated by a permanent magnet and dried in a vacuum desiccator.

2.3. Characterization

In order to verify an eventual oxidation of magnetite by the formation of secondary phases, such as maghemite, γ-Fe2O3, and/or hematite, α-Fe2O3, the as-synthesized products were analyzed in the Fe2+/Fe3+ molar ratio. The samples were dissolved in H2SO4 3M under O2-free conditions. The Fe2+ content was analyzed by permanganometric determination, while the total iron (Fe2+ + Fe3+) was determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. The quantity of crystalline phases was determined by Rietveld quantitative analysis using an X-ray diffractometer (PA Nalytical B.V. Almelo, the Netherlands). Data collection was performed using Cu-Kα (λ = 0.154060 nm) radiation (step time, 10 s; step size, 0.05°; 2θ angular range = 5°–95°).

The specific surface area of the powders was measured by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method and the pore size distribution of the powders by the adsorption-desorption isotherm utilizing nitrogen as the adsorbate after drying at 80 °C for 12 h (Gemini 2375, Micromeritics Instrument Inc., Norcross, GA, USA).The magnetite nanoparticle morphology was investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (FEI Quanta 600 FEG, Hillsboro, OR, USA) with a field emission electron gun operated at 25 kV. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) study was carried out on an electron microscopy instrument (FEI Tecnai G12 Spirit Twin, Hillsboro, OR, USA). The powders for TEM were dispersed in ethanol; the suspension was then dropped on carbon-copper grids.

The magnetic properties of the particles were measured with a Physical Properties Measurement System magnetometer at 298 K (Quantum Design, San Diego, CA, USA). The magnetization measurement was taken from the −10 kOe to 10 kOe field. From the magnetization versus applied field curve, the saturation magnetization (Ms) was measured.

3. Results

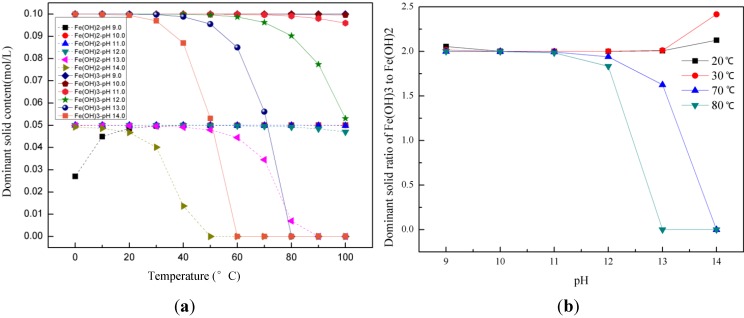

Figure 1a shows the solid concentration in equilibrium with the solution as a function of temperature for various pH conditions, which are equivalent to various amounts of NaOH added during co-precipitation. Here, we see that a stoichiometric ratio of Fe3+ to Fe2+ equal to 2:1 in the solid phase is best achieved at room temperatures, which give the largest window of pH values, from 10.0 to 13.0, where a near perfect 2:1 stoichiometric solid may be produced. At higher temperatures 70–80 °C, the product precipitated from a 2:1 stoichiometric solution is not stoichiometric, except in a narrow pH window. The dominant solids of Fe3+ and Fe2+ ions start to deviate from 0.1 and 0.05 mol/L at pH values greater than 12.0 or 13.0, depending upon temperature. Figure 1b shows the solids ratio of Fe(OH)3 to Fe(OH)2. We see that at 20–30 °C, this ratio stays perfect close to 2.0 in the pH window from 10.0 to 13.0. At higher temperatures 70–80 °C, a 2:1 stoichiometric solution produces a 2:1 stoichiometric solid at pH values less than 12.0, and this ratio starts to deviate from 2.0 at pH values greater than 12.0. This is contrary to the method of increasing pH (OH− concentration) to high values in order to completely precipitate the iron species as hydroxides that is used by experimentalists. These results justify the reason for which all the syntheses have been performed at room temperature.

Figure 1.

(a) Dominant solids (Fe(OH)2 and Fe(OH)3) concentration (mol/L) as a function of temperature at various pH values. Other solids are not precipitated at these conditions; and (b) Dominant solids ratio of Fe(OH)3 to Fe(OH)2 at room temperature (20–30 °C) and high temperature (70–80 °C) at various pH values.

The co-precipitation method using Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions reacting in alkaline conditions has been extensively investigated [24,27,28,29,30], and the following reactions are proposed for the mechanism of magnetite formation:

| Fe3+ + 3OH− = Fe(OH)3 (s) | (2) |

| Fe(OH)3 (s) = FeOOH (s) + H2O | (3) |

| Fe2+ + 2OH− = Fe(OH)2 (s) | (4) |

| 2FeOOH (s) + Fe(OH)2 (s) = Fe3O4 (s) + 2H2O. | (5) |

Giving an overall reaction:

| 2Fe3+ + Fe2+ + 8OH− = 2Fe(OH)3Fe(OH)2 (s) → Fe3O4 (s) + 4H2O | (6) |

First, the ferric and ferrous hydroxides are precipitated. These reactions are very fast. Second, the ferric hydroxide decomposes to FeOOH, due to the low water activity of the resulting NaCl solution in a slower reaction. Finally, a solid state reaction between FeOOH and Fe(OH)2 takes place, due to the low water activity of the solution, which produces magnetite. This solid state reaction takes place between 10 and 30 min at room temperature. The overall reaction mechanism is a dynamic equilibrium equation in which the concentration and size of Fe3O4 nanoparticles are influenced by [Fe3+], [Fe2+] and [OH−], as well as the water activity of the solution. We design ferric to ferrous molar ratio as 2:1, which is the exact stoichiometry for magnetite, in order to produce high purity magnetite nanoparticles. The final [OH−] concentration, which is related to the pH and base amount, is known to control the nucleation and growth of the magnetite nanoparticles and can influence the magnetite properties, e.g., particle size and saturation magnetization (Ms). In this study, the room temperature syntheses of magnetite, obtained at various pH values by varying the nature of the base and its amount, are reported in Table 2.

3.1. Elemental Analysis

The individual Fe2+ content of the products was obtained by permanganometric determination, while the amount of the individual Fe3+ was calculated from the difference between the total iron and the Fe2+ content. The experimental Fe2+/Fe3+ molar ratio being of the order of 0.45 (Table 3) with respect to the theoretical ratio of 0.5 proves that the synthesized magnetite products are pure enough.

Table 3.

Fe2+/Fe3+ molar ratio determined by elemental analysis and quantitative crystalline phases determined by the Rietveld method for the synthesized products.

| Sample | Fe2+/Fe3+ Molar ratio | Magnetite (wt %) | Maghemite (wt %) | Hematite (wt %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.48 | 98.0 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| S2 | 0.47 | 96.7 | 2.9 | 0.4 |

| S3 | 0.45 | 95.5 | 4.2 | 0.3 |

| S4 | 0.46 | 96.1 | 3.3 | 0.6 |

| S5 | 0.43 | 93.9 | 5.8 | 0.4 |

| F1Na | 0.49 | 98.2 | 1.6 | 0.2 |

| F3Na | 0.44 | 94.0 | 5.5 | 0.5 |

| F5Na | 0.42 | 91.1 | 8.7 | 0.2 |

| F3K | 0.43 | 92.3 | 6.3 | 0.4 |

| F3TEA | 0.41 | 90.3 | 9.4 | 0.3 |

3.2. XRD Pattern

An estimation of magnetite content for the products, determined by the Rietveld XRD quantification, are also reported in Table 3. A good agreement between the data of elemental analysis and those of quantitative phase analysis by the Rietveld method results.

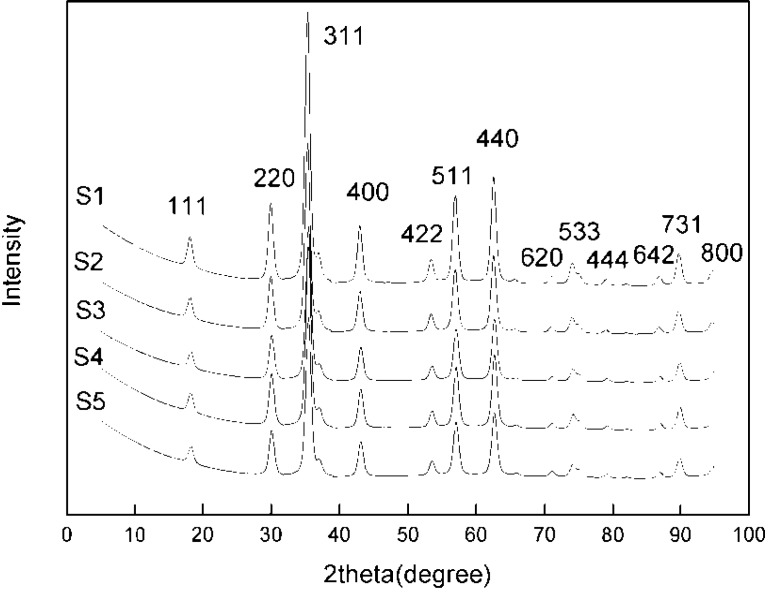

Figure 2 shows the XRD patterns of magnetite particles synthesized by slow addition at various NaOH amounts and pH values. The XRD diffraction peaks correspond well to magnetite Fe3O4 (JCPDS file, No. 00-011-0614). The products synthesized by fast addition also show XRD patterns typical of magnetite particles.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction of magnetite nanoparticles synthesized at various NaOH amounts.

An estimation of the magnetite nanoparticles size has been performed from the Scherrer formula:

| (7) |

where λ is the X-ray wavelength (0.15406 nm), B is the full width at half maximum (FWHM); θ is the corresponding Bragg angle; and K is the shape parameter, which is 0.89 for magnetite. Taking the highest intensity peak, namely the (311) plane, at 2θ = 35.4°, and the half maximum intensity width of the peak after accounting for instrument broadening, the calculated particle sizes are 11.5, 11.2, 11.0, 10.9 and 10.7 nm for samples S1, S2, S3, S4 and S5, respectively (the second column of Table 3). As the NaOH amount and pH increases, the nanoparticle size decreases, albeit a small amount. At higher pH, supersaturation during co-precipitation is higher, promoting nucleation over growth, thus giving smaller particle sizes. By using the co-precipitation method over this wide range of pH values at room temperature, it is easy to prepare magnetite nanoparticles with an approximate size of 11.0 nm.

Note that in the XRD patterns, the peak positions shift slightly forward to larger 2θ values with increasing pH. The (311) XRD peak of the products as a magnified representation clearly shows the peak shift, indicating that the lattice parameter contracts as the particle size decreases (Figure 3). This phenomenon has also been observed and reported in previous works [28,31].

Figure 3.

(311) peaks of the magnetite nanoparticles in expanded 2θ scale.

The fast addition of the stoichiometricor of the more concentrated NaOH solution to the reaction solution determines the formation of magnetite nanoparticles smaller in sizes,10.2 and 8.2 nm for F1Na and F5Na samples, respectively, in comparison to those of the corresponding magnetite obtained by slow addition of the base. The fast addition favors the continuous nucleation with respect to growth, thus enabling the formation of small particles. The nature of the precipitating base also affects the particle sizes. Smaller magnetite nanoparticles of 7.1 and 6.5 nm result for F3K and F3TEA samples synthesized by fast addition of KOH and TEAOH, respectively. The sample * F3TEA, synthesized with a reverse modality by fast addition of ferrous and ferric ions into TEAOH solution, shows magnetite nanoparticles of 6.4 nm determined by TEM, a size very similar to that of the F3TEA sample synthesized by fast addition of TEAOH solution into the iron chloride-containing solution.

Although the syntheses were performed under O2-free conditions, a certain oxidation of magnetite into maghemite results. By comparing the maghemite content detected in the synthesized products (Table 3) with the corresponding crystal sizes shown in Table 4, it can be seen that the smaller the particle sizes of magnetite, the higher the maghemite content. These results agree with the higher reactivity of magnetite characterized by a crystal smaller in size.

Table 4.

Properties of magnetite samples. Ms, saturation magnetization.

| Sample | Size (nm) | Specific surface area (m2/g) | Specific surface area (m2/g) | Interface area (m2/g) | Ms(emu/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XRD | BET | XRD | BET | (SXRD-SBET)/2 | ||

| S1 | 11.5 | 12.9 | 100.7 | 89.4 | 5.6 | 75.3 |

| S2 | 11.2 | 12.4 | 103.4 | 93.3 | 5.1 | 71.6 |

| S3 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 105.3 | 97.1 | 4.1 | 69.8 |

| S4 | 10.9 | 11.8 | 106.3 | 97.8 | 4.3 | 69.4 |

| S5 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 108.3 | 99.4 | 4.5 | 68.3 |

| F1Na | 10.2 | 11.8 | 113.6 | 98.1 | 7.7 | 64.8 |

| F3Na | 9.1 | 10.0 | 127.0 | 109.0 | 9.0 | 58.1 |

| F5Na | 8. 2 | 8.9 | 141.3 | 130.0 | 5.6 | 54.1 |

| F3K | 7.1 | 7.6 | 163.1 | 152.4 | 5.3 | 53.6 |

| F3TEA | 6.5 | 6.9 | 178.2 | 167.9 | 5.1 | 52.3 |

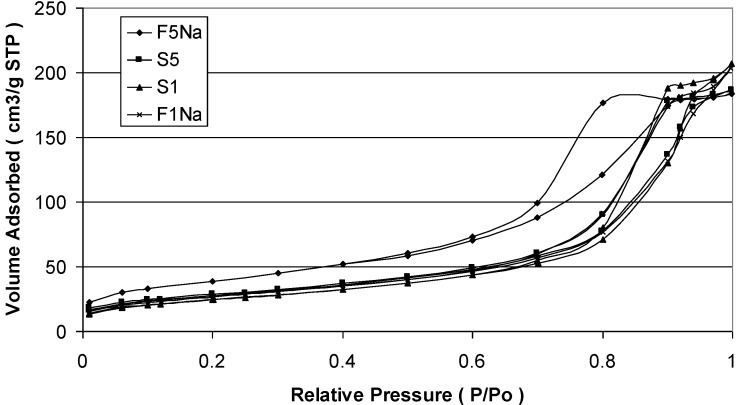

3.3. BET Measurement

Table 4 shows also the specific surface area measured by the BET method and saturation magnetization (Ms) of the magnetite nanoparticles synthesized at various conditions. Here, the listed particle size is calculated either from XRD or from BET measurement adopting the particles diameter, D, given by:

| (8) |

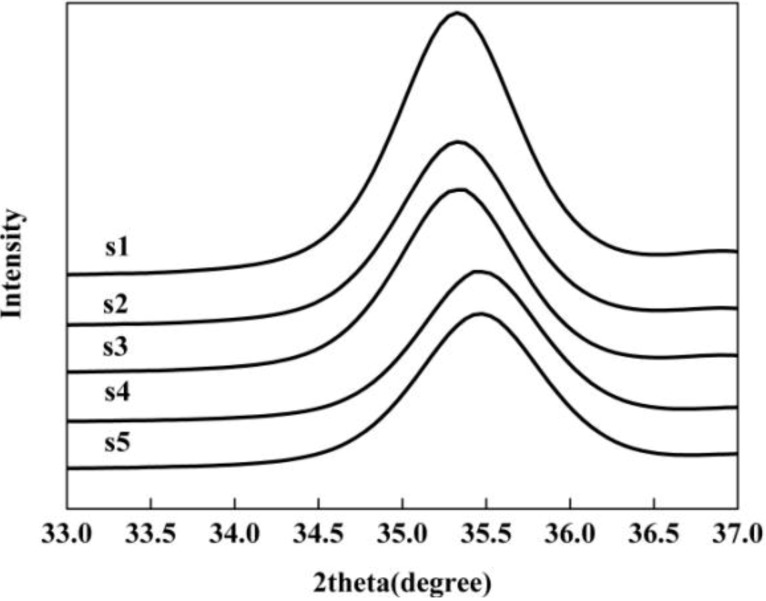

where Ssp is the specific surface area of the sample and ρa is the density 5.18 g/cm3. We can see that, when the pH increases, the specific surface area increases and particle size decreases. The sizes calculated from BET measurements, compared with the size from XRD, are larger. Such a difference in size for the magnetite samples can be explained with the agglomeration of the nanosized particles, so determining lower surface area and, consequently, an apparent larger particle size. Such agglomeration has been evaluated determining the interface area among the particles of magnetite adopting the formula (SXRD – SBET)/2, where SXRD is the surface area calculated from crystal size measured with the Sherrer formula, whereas SBET is the surface area determined with the BET method. The agglomeration of the nanosized particles of magnetite is confirmed by the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms shown in Figure 4 for the samples S1, S5, F1Na and F5Na, respectively. Each product is characterized, in fact, by a clear hysteresis loop, which is typical of mesoporous products as a consequence of the agglomeration.

Figure 4.

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of S1, S5, F1Na and F5Na samples.

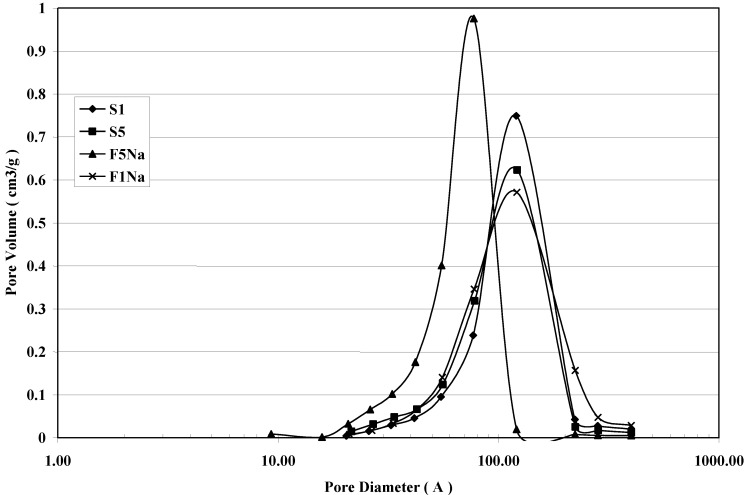

The corresponding Barret–Joiner–Halenda (BJH) pore size distribution determined from the desorption branch isotherm are shown in Figure 5. A pore size distribution with pores changing in the mesopore range is the result for all the samples. The maximum of the pore size is affected by the particle size of magnetite. The smaller the particle size of magnetite, the lower is the maximum of the pore size results. The fast addition with an excess of the NaOH solution gives a magnetite product with the maximum shifted to smaller values of mesopores. It is also evident that a broader pore size distribution characterizes the products synthesized by the slow addition of the basic solution in comparison to that of the products obtained by the fast addition of the precipitating base.

Figure 5.

BJH desorption pore size distribution curves for S1, S5, F1Na and F5Na samples.

3.4. SEM and TEM Images

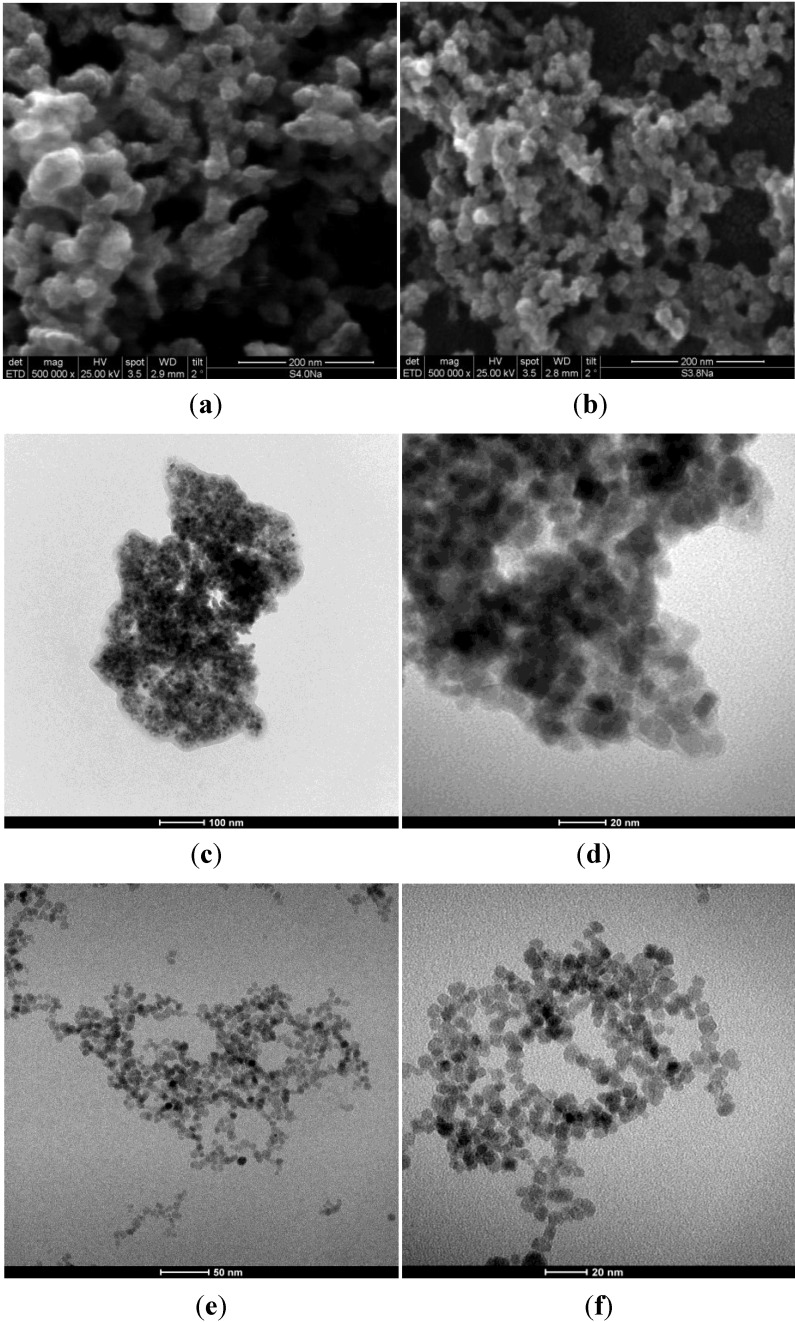

Figure 6 shows SEM images of S4 and S5 samples and TEM images of F3Na and * F3TEA samples, respectively. SEM images show that the samples consist of particles with a nearly spherical shape. They are approximately 11.0 nm in size, indicating that homogeneous magnetite nanoparticles can be synthesized in a large pH window at room temperature.

Figure 6.

SEM images of (a) S4; (b) S5 samples; and TEM images of (c,d) F3Na; and (e,f) * F3TEA.

The magnetite particles are more or less agglomerated, so determining, in the absence of a surfactant, the formation of aggregates with a broad range of mesopores, as can be seen in the TEM images of Figure 6c,d. The TEM images of * F3TEA in Figure 6e,f shows single magnetite particles, due to their very poor agglomeration. Such findings justify the different behavior of this sample in terms of the stability suspension of magnetic particles in the liquid medium.

The * F3TEA sample results in a perfect colloidal suspension, due to the absence of any particles edimentation after several months of aging, whereas for all the other samples, the sedimentation of aggregates results in more or less short times of aging.

This behavior can be related to two concomitant effects of the basic solution of the TEAOH. The magnetic particles synthesized in the presence of TEAOH are very small in size, so that their thermal energy is large enough to overcome the energy of the magnetic interactions among the magnetite nanoparticles [32]. The OH− ions of the basic TEAOH-containing solution are adsorbed onto the magnetite particles, determining a negative charge on each particle. As a surfactant, the positively-charged tetraethylammonium ions form a shell around each magnetite particle, so raising the energy required for the particles to agglomerate, stabilizing the corresponding colloidal suspension. For the F3TEA sample, obtained by fast addition of the TEAOH solution into iron chloride-containing solution, the sedimentation of magnetite particles occurs. Such a difference might be related to the more basic medium in the first step of the reaction when iron chlorides are rapidly added to TEAOH.

3.5. Magnetic Properties

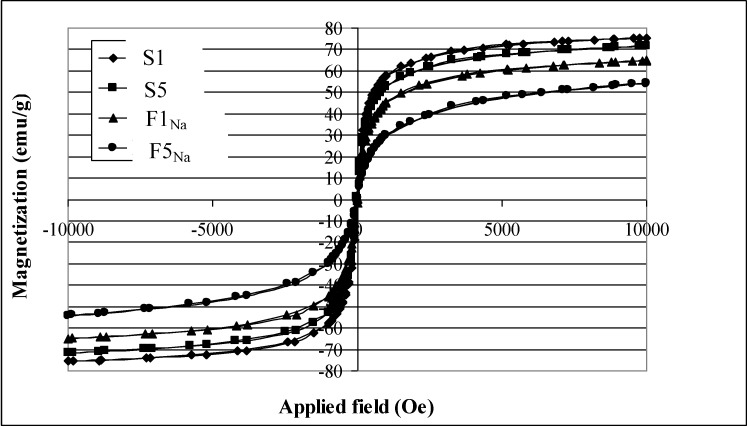

The magnetization curve for the synthesized magnetite nanoparticles reported in Figure 7 does not show any hysteresis behavior for any of the samples and exhibits immeasurable values of coercivity field and remnant magnetization.

Figure 7.

Magnetization curves for S1, S2, F1Na and F5Na samples.

This confirms that the synthesized particles exhibit superparamagnetic properties at room temperature. This is in good agreement with a previous study: that magnetite nanoparticles exhibit superparamagnetic properties when they are smaller than the critical size of the magnetic domain size [36,37,38].

Table 4 shows the saturation magnetization (Ms) of all the synthesized samples. We can see that Ms values decrease as the magnetite particle size decreases. This effect has been reported, in great number, previously [26,28,29,31].

4. Discussion

The formation of crystalline magnetite from solution by nucleation and growth appears to proceed through rapid agglomeration of nanometric primary particles [39]. Such agglomeration determines branched networks, which, in turn, become denser with the formation of crystalline spheroidal nanoparticles higher in size. The final size of individual particles is affected by several parameters, such as: the pH of solution, reaction temperature, concentration of precursors and slow or fast mixing of reagents [40].

A further agglomeration of individual nanoparticles determines the formation of aggregates higher in size. This last agglomeration appears to be responsible for the formation of mesopores, as can be seen in Figure 4 and Figure 5. Their formation could be attributed to the magnetostatic interaction of magnetite particles. It is not to be excluded that the particles agglomerate during magnetic separation and/or during washing/drying of the nanopowders.

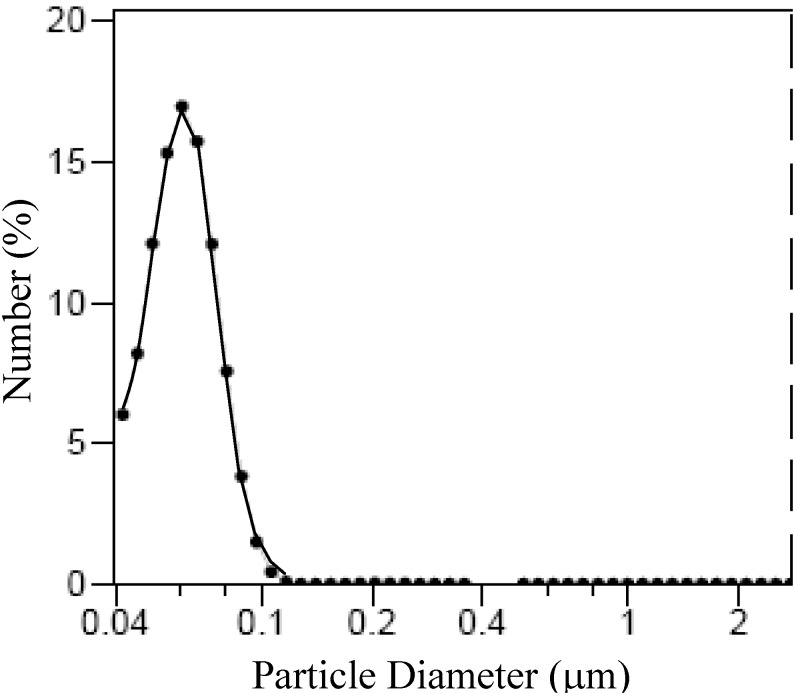

It must be outlined that with the exclusion of the sample, F*3TEA, all the synthesized samples exhibit a distribution of the aggregates size (Figure 8) with a median size of 63 ± 25 nm, as determined by laser light scattering (LS). The formation of these aggregates could be mainly attributed to magnetostatic interaction [35].

Figure 8.

Size distribution of magnetite aggregates determined by laser light scattering (LS).

The aggregates sizes observed by TEM resulted in an order higher size than those detected by LS. Such differences could be attributed to the agglomeration following the magnetic separation and/or washing-drying of the nanoparticles. On the other hand, an increase of interface area with the decrease of particle size must be expected. The resulting interface area for the sample F3Na, F3K and F3TEA, synthesized with the same concentration of base, contrasts the above sentence. Nevertheless, the particle sizes of magnetite decrease according to the following sequence of counter cations of base: Na+ > K+ > N(C2H4)+4; the interface area decreases, in fact, with the same sequence as reported in Table 4. Such a discrepancy could be attributed to the effect of steric hindrance connected to the cations bigger in size, which hamper the agglomeration among the individual nanoparticles.

Recently, a new strategy to perform bioseparation and diagnostic target isolation under continuous flow processing conditions has been described [41]. Reversible aggregation-disaggregation of magnetite nanoparticles under the action of a pH-responsive polymer coating has been exploited. To this end, the degree of agglomeration of magnetite nanoparticles appears to be of great interest.

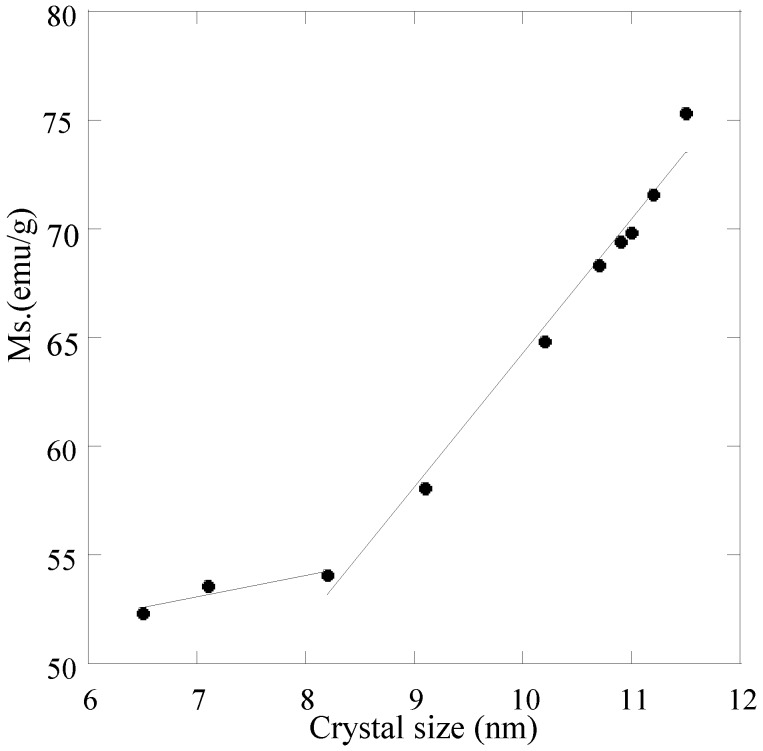

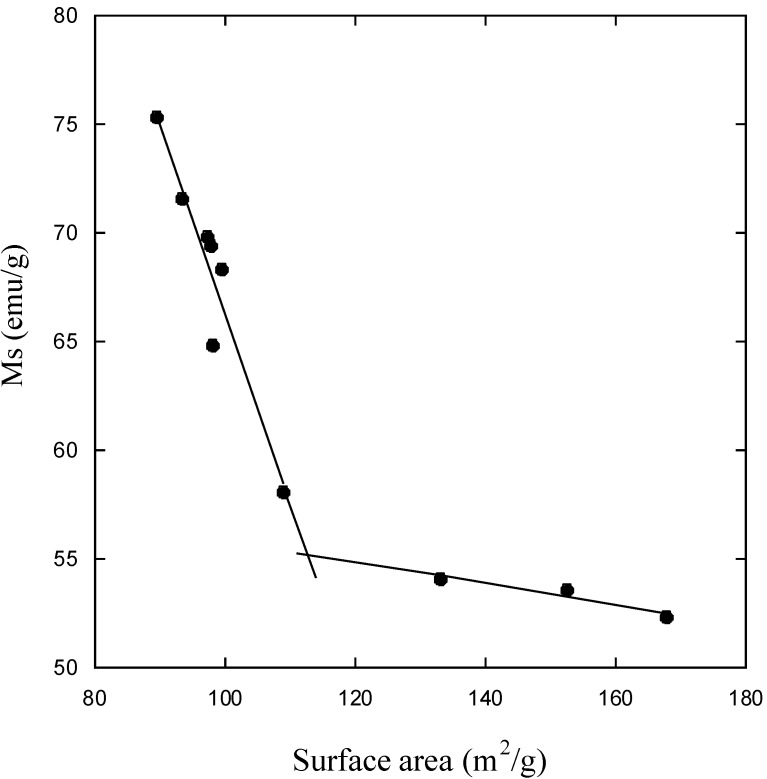

The nanosized magnetite samples display superparamagnetism and saturation magnetization (Ms) values smaller than the bulk magnetite value, 92 emu/g. On the other hand, the synthesized samples show large differences regarding the Ms values measured at room temperature (Table 4). The reduction of Ms can be prevalently related with the magnetite size. A linear correlation between Ms and the particle size of magnetite results, as can be seen in Figure 9 for particle sizes ranging between 9 and 12 nm. An analogous correlation results between Ms and surface area (Figure 10). This linear correlation between Ms and particle size was reported for maghemite [42]. A second linear correlation with a lower gradient can be seen in the 6.5–8.0 nm size range of magnetite particles.

Figure 9.

Saturation magnetization (Ms) as a function of magnetite particles size.

Figure 10.

Saturation magnetization (Ms) as a function of magnetite surface area.

Several explanations have been provided on the decrease of the Ms with the reduction of the particle size of magnetite. One factor concerns the entity of the spin disorder layer, which increases with a decrease in crystallite size [33]. Another factor for the reduction of the magnetic moment can be also explained through the effect of a dipolar interaction between magnetite nanoparticles [32]. The irregular morphology of magnetite particles might influence the value of Ms as a contribution from surface anisotropy [34]. As all the synthesized samples are almost spherical in shape, a zero contribution from surface anisotropy must be expected [43]. A further reduction of Ms could be attributed to incomplete crystallization of magnetite after the reaction synthesis. The decrease in Ms can be also due to changes in A and B site population [44]

The presence of a bend in Figure 9 involves a different trend of Ms as a function of magnetite size. A possible explanation could be related to the nature of the countercation of the base, which affects the degree of agglomeration: i.e., the decrease of magnetite particle size determines a decrease of the agglomeration in the 6.5–8.0 nm size range, so contrasting with the reduction of Ms.

5. Conclusions

A cheap co-precipitation method has been utilized to synthesize magnetite nanoparticles exhibiting superparamagnetic behavior. They were formed by a one pot co-precipitation reaction in a large pH window (10.0–13.0) at room temperature. The size reduction of magnetite nanoparticles, precipitated with a certain base, is affected by both the pH and the slow or fast addition of the basic solution to the solution of mixed Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions. A further reduction of magnetite size can be determined by the nature of the precipitating base in accordance with the following sequence: (C2H5)4NOH < KOH < NaOH.

The resulting magnetite nanoparticles exhibit superparamagnetic properties, depending on the particle size: the lower the particle size, the lower is the saturation magnetization (Ms).

The agglomeration among the magnetite nanoparticles determines the formation of mesopores, whose average size is affected by the size of individual particles. Mesopores larger in size result, in fact, in bigger particles, whereas mesopores smaller in size result in smaller particles. The degree of agglomeration, determined by the interface area among the individual particles, affects the Ms value. Its reduction with the decrease of magnetite particle size becomes less marked for less agglomerated particles: i.e., magnetite synthesized in the presence of a base with a counteraction bigger in size (C2H5)4NOH.

The synthesized magnetite with different mesoporous structures appears very promising for biomedical applications. It is well known that because of the low drug or enzyme loading on the conventional magnetite nanoparticles, the magnetic material is often incorporated into mesoporous materials to form a hybrid support with a consequent reduction of Ms. The synthesized products, being combinations of mesoporous properties with a magnetic property, appear to be of interest for biomedical applications.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the financial support from the Chinese Scholarship Council, which has provided support for an author to perform this research at the University of Utah. OLI Systems, Inc. is thanked for use of the Lab Analyzer℘ software. Joseph G. Bolke, Alex Hogan and Amber C. McConnell from the Departments of Material Science (Nanolab) and Chemistry at the University of Utah are thanked for assistance with XRD, SEM and magnetic measurements.

Thanks are also due to Lab. of Scanning and Transmission Electron Microscopy (LaMEST) of Institute of Chemistry and Technology of Polymers/Institute of Composite and Biomedical Materials (ICTP/IMCB) of National Research Council CNR, Pozzuoli (NA), Italy, for TEM measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Reference

- 1.Nishio K., Ikeda M., Gokon N., Tsubouchi S., Narimatsu H., Mochizuki Y., Sakamoto S., Sandhu A., Abe M., Handa H. Preparation of size-controlled (30–100 nm) magnetite nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007;310:2408–2410. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2006.10.795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta A.K., Gupta M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3995–4021. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jun Y.W., Lee J.H., Cheon J. Chemical design of nanoparticle probes for high-performance magnetic resonance imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:5122–5135. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudimack J.B.A., Lee R.J. Targeted drug delivery via the folate receptor. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2000;41:147–162. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(99)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan A., Scholz R., Maier-hauff K., Johannsen M., Wust P., Nadobny J., Schirra H., Schmidt H., Deger S., Loening S., et al. Presentation of a new magnetic field therapy system for the treatment of human solid tumors with magnetic fluid hyperthermia. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2001;225:118–126. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu F., Wei L., Zhou Z., Ran Y., Li Z., Gao M. Preparation of biocompatible magnetite nanocrystals for in vivo magnetic resonance detection of cancer. Adv. Mater. 2006;18:2553–2556. doi: 10.1002/adma.200600385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song H., Choi J., Huh Y., Kim S., Jun Y., Suh J., Cheon J. Surface modulation of magneticnanocrystals in the development of highly efficient magnetic resonance probes for intracellularlabeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9992–9993. doi: 10.1021/ja051833y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun S., Zeng H. Size-controlled synthesis of magnetite nano-particies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:8204–8205. doi: 10.1021/ja026501x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dronskowski R. The little maghemite story: A classic functional material. Adv. Func. Mater. 2001;11:27–29. doi: 10.1002/1616-3028(200102)11:1<27::AID-ADFM27>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tartaj P., Morales M.P., Gonzales-Carreno T., Veintemillas-Verdaguer S., Serna C.J. Advances in magnetic nanoparticles for biotechnology applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005;290:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2004.11.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petri-Fink A., Chastellain M., Juillerat-Jeanneret L., Ferrari A., Hofmann H. Development offunctionalized superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for interaction with human cancercells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2685–2694. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teo B.M., Chen F., Hatton T.A., Grieser F., Ashokkumar M. Novel one-pot synthesis ofmagnetite latex nanoparticles by ultrasound irradiation. Langmuir. 2009;25:2593–2595. doi: 10.1021/la804278w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teja A.S., Koh P. Synthesis, properties, and applications of magnetic iron oxidenanoparticles. Prog. Cryst. Growth Charact. Mater. 2009;55:22–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pcrysgrow.2008.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng S., Wang C., Xie J., Sun S. Synthesis and stabilization of monodisperse Fe nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10676–10677. doi: 10.1021/ja063969h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge J., Hu Y., Biasini M., Dong C., Guo J., Beyermann W.P., Yin Y. One-step synthesis of highly water-soluble magnetite colloidal nanocrystals. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:7153–7161. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu X., Niu M., Qiao R., Gao M. Superdispersible PVP-coated Fe3O4 nanocrystalsprepared by a “one-pot” reaction. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:14390–14394. doi: 10.1021/jp8025072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Z., Chen H., Bao H., Gao M. One-pot reaction to synthesize water-soluble magnetite nanocrystals. Chem. Mater. 2004;16:1391–1393. doi: 10.1021/cm035346y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vargas J.M., Zysler R.D. Tailoring the size in colloidal iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2005;16:1474–1476. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/16/9/009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu D., Wang Y., Song Q. Weakly magnetic field-assisted synthesis of magnetite nanoparticles in oxidative co-precipitation. Particuology. 2009;7:363–367. doi: 10.1016/j.partic.2009.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizukoshi Y., Shuto T., Masahashi N., Tanabe S. Preparation of superparamagneticmagnetite nanoparticles by reverse precipitation method: Contribution of sonochemicallygenerated oxidants. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2009;16:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nedkov I., Merodiiska T., Slavov L., Vandenberghe R.E., Kusano Y., Takada J. Surfaceoxidation, size and shape of nano-sized magnetite obtained by coprecipitation. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006;300:358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2005.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qu S., Yang H., Ren D., Kan S., Zou G., Li D., Li M. Magnetite nanoparticles prepared byprecipitation from partially reduced ferric chloride aqueous solutions. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 1999;215:190–192. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1999.6185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pardoe H., Chua-anusorn W., Pierre T.G.S., Dobson J. Structural and magnetic properties of nanoscale iron oxide particles synthesized in the presence of dextran or polyvinyl alcohol. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2001;225:41–46. doi: 10.1016/S0304-8853(00)01226-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandhu A., Mukherjee S., Acharya S., Modak S., Brahma S.K., Das D., Chakrabarti P.K. Dynamic magnetic behavior and Mössbauer effect measurements of magnetite nanoparticles prepared by a new technique in the co-precipitation method. Solid State Commun. 2009;149:1790–1794. doi: 10.1016/j.ssc.2009.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozkaya T., Toprak M.S., Baykal A., Kavas H., Koseoglu Y., Aktas B. Synthesis of Fe3O4 nanoparticles at 100 °C and its magnetic characterization. J. Alloys Compd. 2009;472:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.04.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao S., Asuha S. One-pot synthesis of magnetite nanopowder and their magneticproperties. Powder Technol. 2010;197:295–297. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2009.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valenzuela R., Fuentes M.C., Parra C., Baeza J., Duran N., Sharma S.K., Knobel M., Freer J. Influence of stirring velocity on the synthesis of magnetite nanopraticles (Fe3O4) by theco-precipitation method. J. Alloys Compd. 2009;488:227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.08.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gnanaprakash G., Philip J., Jayakumar T., Raj B. Effect of digestion time and alkaliaddition rate on physical properties of magnetite nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. 2007;111:7978–7986. doi: 10.1021/jp071299b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gnanaprakash G., Mahadevan S., Jayakumar T., Kalyanasundaram P., Philip J., Raj B. Effect of initial pH and temperature of iron salt solutions on formation of magnetite nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2007;103:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2007.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vereda F., Vicente J., Hidalgo-Alvarez R. Influence of a magnetic field in the formation of magnetite particles via two precipitation methods. Langmuir. 2007;23:3581–3589. doi: 10.1021/la0633583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumgartner J., Bertinetti L., Widdrat M., Hirt A.M., Faivre D. Formation of magnetite nanoparticles at low temperature: From superparamagnetic to stable single domain particles. Plos One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goya G.F., Berquó T.S., Fonseca F.C., Morales M.P. Static and dynamic magnetic properties of spherical magnetite nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2003;94:3520–3528. doi: 10.1063/1.1599959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang B., Wei Q., Qu S. Synthesis and characterization of uniform and crystalline magnetite nanoparticles via oxidation-precipitation and modified co-precipitation methods. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013;8:3786–3793. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahmed N., Heczko O., Söderberg O., Hannula S.P. Room temperature synthesis of magnetite (Fe3−δO4) nanoparticles by a simple reverse co-precipitation Method. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2011;18 doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/18/3/032020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maity D., Agrawal D.C. Synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles under oxidizing environment and their stabilization in aqueous and non-aqueous media. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007;308:46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park J.Y., Patel D., Choi E.S., Baek M.J., Chang Y., Kim T.J., Lee G.H. Salt effects on the physical properties of magnetite nanoparticles synthesized at different NaCl concentrations. Colloids Surf. 2010;367:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2010.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jolivet J.P., Massart R., Fruchart J.M. Synthesis and physicochemical study onnonsurfactant magnetic colloids in aqueous medium. Nouv. J. Chim. 1983;7:325–331. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunlop D.J. Superparamagnetic and single-domain thresh old sizes in magnetite. Geophys. J. Res. 1973;78:1780–793. doi: 10.1029/JB078i011p01780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baumgartner J., Dey A., Bomans P.H.H., Coadou C.L., Fratzl P., Sommerdijk N.A.J.M., Faivre D. Nucleation and growth of magnetite from solution. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:310–314. doi: 10.1038/nmat3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vayssières L., Chanéac C., Tronc E., Jolivet J.P. Size tailoring of magnetite particles formed by aqueous precipitation: An example of thermodynamic stability of nanometric oxide particles. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 1998;205:205–212. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1998.5614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lai J.J., Nelson K.E., Nash M.A., Hoffman A.S., Yager P., Stayton P.S. Dynamic bioprocessing and microfluidic transport control with smart magnetic nanoparticles in laminar-flow devices. Lab Chip. 2009;9:1997–2002. doi: 10.1039/b817754f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morales M.P., Andres-Verges M., Veintemillas-Verdaguer S., Montero M.I., Serna C.J. Structural effects on the magnetic properties of gamma-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1999;203:146–148. doi: 10.1016/S0304-8853(99)00278-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bødker F., Mørup S., Linderoth S. Surface effects in metallic lron nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994;72:282–285. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goya G.F. Magnetic dynamics of Zn57Fe2O4 nanoparticles dispersed in a ZnO matrix. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2002;38:2610–2612. doi: 10.1109/TMAG.2002.803204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]