ABSTRACT

The formation and localization of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) granules in Ralstonia eutropha are controlled by PhaM, which interacts both with the PHB synthase (PhaC) and with the bacterial nucleoid. Here, we studied the importance of proline and lysine residues of two C-terminal PAKKA motifs in PhaM for their importance in attaching PHB granules to DNA by in vitro and in vivo methods. Substitution of the lysine residues but not of the proline residues resulted in detachment of formed PHB granules from the nucleoid. Instead, formation of PHB granule clusters at polar regions of the rod-shaped cells and an unequal distribution of PHB granules to daughter cells were observed. The formation of PHB granules was studied by the expression of chromosomally anchored gene fusions of fluorescent proteins with PhaM and PhaC in different backgrounds. PhaM and PhaC fusions showed a distinct colocalization at formed PHB granules in the nucleoid region of the wild type. In a ΔphaC background, PhaM and the catalytically inactive PhaCC319A protein were not able to form fluorescent foci, indicating that correct positioning requires the formation of PHB. Furthermore, time-lapse experiments revealed that PhaC and PhaM proteins detach from formed PHB granules at later stages, resulting in a nonhomogeneous population of PHB granules. This could explain why growth of individual PHB granules stops under PHB-permissive conditions at a certain size.

IMPORTANCE PHB granules are storage compounds for carbon and energy in many prokaryotes. Equal distribution of accumulated PHB granules during cell division is therefore important for optimal fitness of the daughter cells. In R. eutropha, PhaM is responsible for maximal activity of PHB synthase, for initiation of PHB granule formation at discrete regions in the cells, and for association of formed PHB granules with the nucleoid. Here we found that four lysine residues of C-terminal PhaM sequence motifs are essential for association of PHB granules with the nucleoid. Furthermore, we followed PHB granule formation by time-lapse microscopy and provide evidence for aging of PHB granules that is manifested by detachment of previously PHB granule-associated PhaM and PHB synthase.

KEYWORDS: PHB accumulation, Ralstonia eutropha, Ralstonia, biopolymer

INTRODUCTION

Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and related polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are storage compounds in Eubacteria and Archaea. Storage PHAs are accumulated when growth of the bacteria is limited by a compound other than the carbon source. Recent studies suggest that PHB apparently also occurs in mammals and in plants (1, 2). Research in several laboratories has led to a detailed understanding of the formation of PHB or PHA granules, and a considerable number of proteins/genes that are necessary for formation, homeostasis, and degradation of such storage compounds have been identified (3–10). Detailed descriptions of key enzymes such as PHA synthases, PHA depolymerases, and phasins (structural PHA granule-associated proteins [PGAPs]) are given in numerous publications (11–15). Recently, the structure of the PHB synthase PhaC of Ralstonia eutropha has been solved (16–18). The finding of so many proteins with different functions on the PHB granule surface has led to the classification of PHB granules as multifunctional units, and the designation carbonosomes has been proposed for these organelle-like structures (19). However, a closed lipid boundary layer that is characteristic of true organelles in eukaryotes is not present in PHB and PHA granules (20). At present, a boundary layer consisting of only proteins is the most likely surface structure present on PHB or PHA granules. In R. eutropha H16 (alternative designation, Cupriavidus necator H16), up to 14 individual PGAPs are located on the PHA surface layer in vivo as shown by fluorescence microscopy with expressed PGAP-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion proteins. A similar variety of surface-displayed proteins was detected in the carbonosomes formed by Pseudomonas putida, which consist of medium-chain-length hydroxyalkanoic acids (14, 21, 22).

The cell biology of the initiation and formation of PHB granules has attracted only minor attention. After the phenotypic description that the formation and localization of PHB granules do not happen randomly in several PHB-accumulating species, such as Rhodospirillum rubrum, Beijerinckia indica, Azotobacter vinelandii, Caryophanon latum, R. eutropha, and Haloquadrata walsbyi (23–25), two proteins that apparently control the localization of PHB/PHA granules were identified. The first is PhaF, which was identified in Pseudomonas putida as a PHA granule-bound protein (26) and which was able to control the distribution of PHA granules to daughter cells (27). The other is PhaM, which was discovered in R. eutropha as a protein that interacted in vivo with the PHA synthase PhaC (28). Biochemical characterization of PhaM revealed not only that it was able to interact and to bind to PHB synthase but that it also represented a DNA binding protein. Transmission electron microscopic investigation confirmed that PHB granules in R. eutropha colocalized with the bacterial nucleoid (29). Attachment of PhaM to the PHB synthase PhaC was recently confirmed in three other laboratories (17, 30, 31). Binding of PHB granules to the nucleoid as a scaffold enables the cells to equally distribute PHB/PHA granules to daughter cells during cell division. Accordingly, phaM or phaF mutants form only one large carbonsosome, and only one daughter cell can take advantage of the storage compound after cell division (27, 28). In case of PhaM, the protein might be additionally involved in the formation of the PHB granule initiation complex, as it is able to activate PHB synthesis by reducing the lag phase of PHB polymerization and by increasing the activity of PHB synthase (32). In this study, we investigated the function of a C-terminal region of PhaM for binding of PhaM to DNA in vitro and in vivo and studied the initiation of PHB granule formation by in vivo time-lapse fluorescence microscopy in various chromosomal backgrounds.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Lysines of the C-terminal domain of PhaM are essential for interaction with DNA.

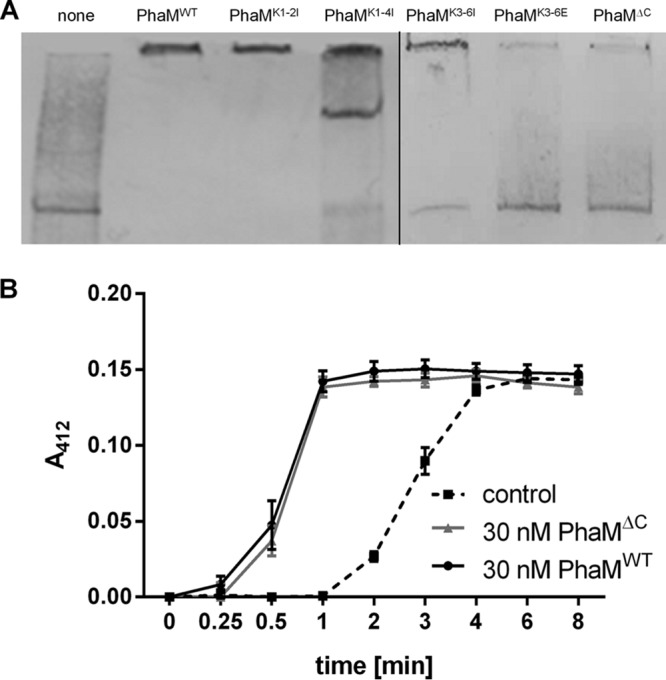

The phaM gene (H16_A0141) codes for a protein of 263 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 26.6 kDa. The calculated isoelectric point is 5.6, suggesting that PhaM is negatively charged. However, PhaM is able to bind to negatively charged DNA in vitro (28). While most of the negatively charged amino acids are located in the N-terminal part of the protein, the C-terminal part of PhaM harbors a 24-amino-acid-long sequence (K217PAARK222APAK226K227APAK231K232AAK235AK237PAR) that is free of any aspartate or glutamate residues but includes 10 basic residues, 8 of which are lysines. This part of PhaM should have a positive charge and could be responsible for interaction of PhaM with DNA. Remarkably, the above-mentioned sequence contains two PAKKA motifs and two PAKKA-like motifs (each one before and after the two PAKKA motifs) which are similar to parts of DNA binding proteins of histones and related DNA binding proteins (33, 34). We therefore hypothesized that the C terminus of the PhaM protein could be responsible for the binding of PhaM to DNA in vitro and for the attachment of PHB granules to the nucleoid via the PHB-bound PhaC-PhaM complex. To find experimental verification for this assumption, we expressed a truncated version of hexahistidine-tagged PhaM protein in which the 47 C-terminal residues, including the PAKKA motifs, were removed. Wild-type (WT) and truncated PhaM proteins were purified, and both were tested for their ability to bind to DNA in vitro by using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). As shown in Fig. 1A, the presence of wild-type PhaM (PhaMWT) resulted in a strong mobility shift in an EMSA. However, no mobility shift was detected when the C-terminally truncated PhaM (PhaMΔC) protein had been added. This result confirmed our previous observations (28) and is in agreement with recent findings by others on the effect of the truncation of the PhaM C terminus (17). The shift in electrophoretic mobility was independent from the source of DNA and was reproduced by using foreign DNA (the PCR-amplified enhanced yellow fluorescent protein [eYFP] gene) or R. eutropha genomic DNA (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The removal of the 47 C-terminal residues did not change the ability of PhaM to reduce the lag phase of PHB synthase-catalyzed in vitro PHB synthesis (Fig. 1B). This result showed that (i) truncation of the C terminus did not detectably change the conformation of the PhaM protein and (ii) the C terminus is not required for PHB synthase activation.

FIG 1.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) of constructed PhaM variants. (A) A PCR-generated DNA fragment labeled with biotin-11-dUTP (eYFP gene DNA, 824 bp, 0.62 nM in each experiment) was incubated with purified His6-tagged PhaM variants for 20 min at room temperature. After electrophoresis (6% native polyacrylamide gel) and blotting, biotinylated DNA-protein complexes were detected as described in Materials and Methods. Additions: none (control without PhaM) (lane 1), 5.4 μM PhaMWT (lane 2), 5.4 μM PhaM muteins as specified (lanes 3 to 7). (B) Effect of truncation of the C terminus of PhaM on PHB synthase activation. A continuous PHB synthase assay was performed using purified PHB synthase and PhaMWT or PhaMΔC. The dashed line corresponds to a control experiment without added PhaM.

To determine whether the positively charged lysine residues are responsible for interaction with the DNA, we constructed phaM variant genes in which the codons for the first two lysine residues (K217K222) upstream of the two PAKKA motifs (PhaMK1-2I), for the first four lysine residues (K217K222K226K227) (PhaMK1-4I), or for the central four lysine residues of both PAKKA motifs (K226K227K232K235) (PhaMK3-6I) were replaced by isoleucine codons. A list of all constructed PhaM variants is shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. The PhaM variants were expressed in Escherichia coli, purified from soluble cell extracts via Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA)-agarose affinity chromatography, and subsequently tested for the ability to interact with DNA by EMSA. Exchange of the first two lysine residues for isoleucine had no effect on the ability of PhaM to interact with DNA, and the same electrophoretic mobility shift as for PhaMWT was determined (Fig. 1A). However, when the first four lysine residues were replaced by isoleucine, an additional DNA-PhaM aggregate with a lower mobility shift as for PhaMWT was observed for PhaMK1-4I. These results suggested that K226K227 but not K217K222 are important for the interaction of PhaM with DNA. When the central four lysine residues (K226K227K232K235) were exchanged for isoleucine (PhaMK3-6I), the PhaM variant had partially lost its ability to reduce the mobility of DNA (Fig. 1A). This result suggested that K232K235 also contribute to the binding of PhaM to DNA. We then constructed a PhaM variant in which the four central lysine residues were replaced by glutamate residues (PhaMK3-6E). Purified PhaMK3-6E, similar to the PhaMΔC variant, was not able to induce any mobility shift, which indicated that the replacement of the central four lysine residues by negatively charged residues completely abolished the DNA binding ability of PhaM (Fig. 1 and S1).

Deletion of the C-terminal domain of PhaM leads to altered PHB granule formation and detachment from the nucleoid.

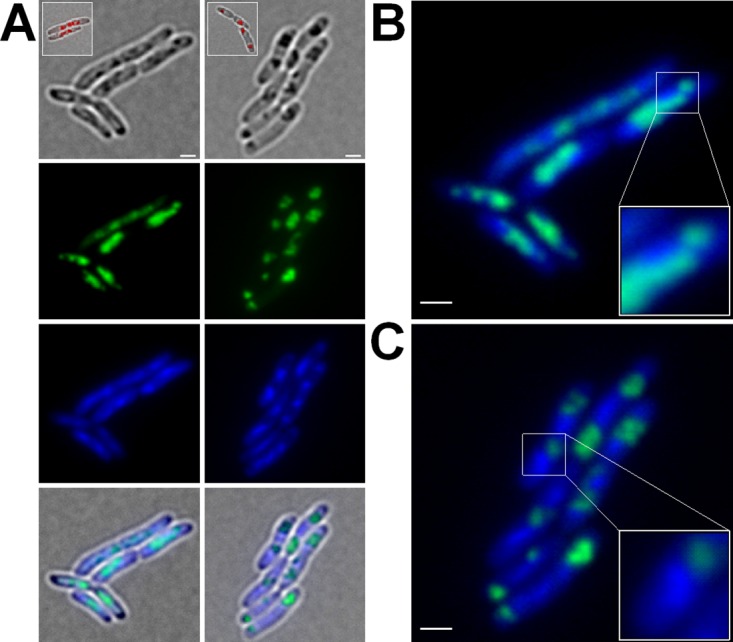

To determine whether the observed in vitro effect of the truncated C terminus of PhaM also had an impact on localization and formation of PHB granules in vivo, we expressed wild-type phaM and the truncated version of phaM as a fusion with the gene for enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) (Fig. 2). Constitutively expressed PhaMWT-eYFP showed a strong fluorescence in the nucleoid region of R. eutropha cells (Fig. 2A, left panels) that colocalized with formed clusters of many small PHB granules when the cells were additionally stained with Nile red. Individual PHB granules in a cluster cannot be resolved by light microscopy but have been previously visualized by transmission electron microscopy (28, 29). In contrast, cells that expressed the truncated PhaMΔC-eYFP protein generally formed one or two (rarely three) foci that had a more condensed and less diffuse appearance than the foci formed by wild-type PhaM-eYFP (Fig. 2A, right panels). Imaging in a bright field and/or staining with Nile red revealed a colocalization of PhaMΔC-eYFP with formed PHB granules and showed that the C-terminal part of PhaM, while essential for interaction with DNA, is not necessary for binding to PHB granules. The formed PhaMΔC-eYFP focus/PHB granule complex was often located close to the cell poles or in the area of future septum formation. Staining of the DNA with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) revealed a close association with the nucleoid region only for PhaMWT-eYFP foci and not for PhaMΔC-eYFP foci (Fig. 2B and C).

FIG 2.

Expression of PhaMWT-eYFP and PhaMΔC-eYFP in R. eutropha H16 cells. Cells expressing PhaMWT-eYFP and PhaMΔC-eYFP were grown on NB medium supplemented with 0.2% Na-gluconate at 30°C. (A) Diffuse fluorescent signals of cells expressing PhaMWT-eYFP colocalized with the DAPI-stained DNA (left panels; enlarged in panel B). Expression of truncated PhaM (PhaMΔC-eYFP) resulted in more focused fluorescence and in detachment from the nucleoid region (right panels; enlarged in panel C). Scale bars correspond to 1 μm. From top to bottom: bright field, eYFP channel, DAPI channel, and merge. Inlays show PHB granules of Nile red-stained cells.

Lysine residues but not proline residues of the PAKKA motifs are responsible for binding of PhaM to DNA and for attachment of PHB granules to the nucleoid.

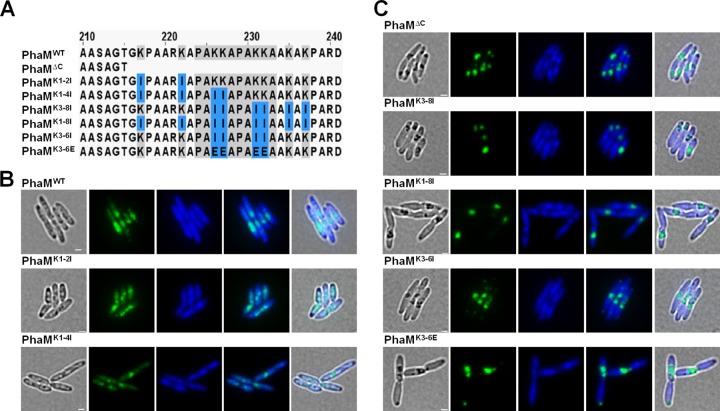

To determine which of the individual residues of the PAKKA motifs could be responsible for the interaction of PhaM with the nucleoid in vivo, we constructed 15 phaM-eYFP gene variants (Table 1 and Fig. S2) in which the codons for one, two, four, six, or eight amino acids of the 24 residues of the PAKKA motif region were exchanged. All phaM-eYFP gene constructs were expressed in R. eutropha, and the localization of PhaM-eYFP foci and PHB granules was determined during growth on nutrient broth (NB)-gluconate medium. No significant difference from wild-type PhaM-eYFP was detected for those PhaM variants in which any of the proline residues was replaced by alanine or histidine (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Even the exchange of both prolines of the two PAKKA motifs (P224 and P229) by alanine or by histidine did not affect PHB granule formation and localization (Fig. S3). We conclude that the prolines of the PAKKA motifs are not essential for interaction of PhaM with PHB granules and with the nucleoid.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmida | Relevant characteristicsb | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| JM109 | Cloning strain | DSMZ 3423 |

| XL-1 Blue | Transformation strain | Stratagene |

| S17-1 | Conjugation strain | 41 |

| Ralstonia eutropha strains | ||

| H16 | Wild-type strain | DSMZ 428 |

| SN6000 | Chromosomal integration of eYFP gene in frame with phaM | This study |

| SN6059 | Chromosomal integration of eYFP gene in frame with phaM in ΔphaC background | This study |

| SN6495 | Chromosomal integration of eYFP gene downstream of A1437 codon in ΔphaM background | This study |

| SN6496 | Chromosomal integration of eYFP gene downstream of A1437 codon | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLO3 | Deletion vector, Tcr, sacB | 38 |

| pLO3-HRI(phaM)-eyfp-HRII | Integration of phaM-eYFP gene | This study |

| pLO3-HRI(phaC)-eyfp-HRII | Integration of phaC-eYFP gene | This study |

| pCM62 | Broad host range vector, Tcr | 42 |

| pCM62-PphaC-dsred2EC-c1 | Universal vector for construction of fusions C-terminal to DsRed2EC under control of the PphaC promoter | 20 |

| pCM62-PphaC-dsred2EC-a1437 | N-terminal fusion of A1437 to DsRed2EC | This study |

| pCM62-PphaC-dsred2EC-a1437C319A | N-terminal fusion of A1437C319A to DsRed2EC | This study |

| pET28a | His tag expression vector, Kmr | Novagen |

| pET28a-phaM | Plasmid for expression of His6-PhaM | 39 |

| pET28a-phaMΔC | Plasmid for expression of His6-PhaM*Δ | This study |

| pET28a-phaMK1-2I | Plasmid for expression of His6-PhaMK1-2I | This study |

| pET28a-phaMK1-4I | Plasmid for expression of His6-PhaMK1-4I | This study |

| pET28a-phaMK3-6I | Plasmid for expression of His6-PhaMK3-6I | This study |

| pET28a-phaMK3-6E | Plasmid for expression of His6-PhaMK3-6E | This study |

| pET28a-phaC | Plasmid for expression of His6-PhaC | 32 |

| pET28a-phaCC319A | Plasmid for expression of His6-PhaCC319A | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2 | Broad-host-range vector, Kmr | 43 |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp | Control vector for eYFP expression | 28 |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-c1 | Universal vector for construction of fusions C-terminal to eYFP under control of the PphaC promoter | 28 |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaM | N-terminal fusion of PhaM to eYFP | 28 |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMΔC | N-terminal fusion of PhaMΔC to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMK1-2I | N-terminal fusion of PhaMK1-2I to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMK1-4I | N-terminal fusion of PhaMK1-4I to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMK3-8I | N-terminal fusion of PhaMK3-8I to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMK1-8I | N-terminal fusion of PhaMK1-8I to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMK3-6I | N-terminal fusion of PhaMK3-6I to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMK3-6E | N-terminal fusion of PhaMK3-6E to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMP1A | N-terminal fusion of PhaMP1A to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMP2A | N-terminal fusion of PhaMP2A to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMP2H | N-terminal fusion of PhaMP2H to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMP3A | N-terminal fusion of PhaMP3A to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMP3H | N-terminal fusion of PhaMP3H to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMP4A | N-terminal fusion of PhaMP4A to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMP2-3A | N-terminal fusion of PhaMP2-3A to eYFP | This study |

| pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaMP2-3H | N-terminal fusion of PhaMP2-3H to eYFP | This study |

HR, homology region (500 bp each).

Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance.

PhaM variants in which the first two lysine residues (PhaMK1-2I) or the first four lysines (PhaMK1-4I) were replaced by isoleucines showed no detectable change in PHB granule formation/localization (Fig. 3). When the four central lysine residues (PhaMK3-6I) were replaced by isoleucines, a phenotype similar to that for the C-terminal deletion was observed at early time points of growth and PHB accumulation, i.e.; the formation of only one or two large PHB granules/clusters near one of the cell poles was detected in the cells. At later time points of growth, cells expressing PhaMK3-6I showed more similarity to R. eutropha cells with PhaMWT. Replacement of the four central lysine residues by glutamate residues (PhaMK3-6E) resulted in the same phenotype as observed for the PhaMΔC variant at all stages of growth and PHB accumulation; clustering of PHB granules detached from the nucleoid region appeared to be more extreme than in the isoleucine variants (Fig. 3). A similar phenotype was determined when six (PhaMK3-8I) or all eight (PhaMK1-8I) lysine residues of the 24-residue-long C-terminal sequence were replaced by isoleucines (Fig. 3). Apparently, an exchange of at least the four central lysine residues of the two PAKKA motifs is required for a phenotypic change in formation and localization of PHB granules. These in vivo findings are in agreement with our in vitro data from gel mobility shift experiments with PhaM variants shown above.

FIG 3.

Phenotypic characterization of truncated PhaM and PhaM lysine mutants in R. eutropha H16 cells. Cells were grown on NB medium supplemented with 0.2% Na-gluconate and 150 μg/ml kanamycin at 30°C. Images were taken after 4 h of PHB formation. (A) Sequence alignment of wild-type PhaM and PhaM mutants, highlighting substituted residues. (B) Replacement of lysine residues upstream of the PAKKA motifs (PhaMK1-2I) and upstream of as well as within the first PAKKA motif (PhaMK1-4I) showed phenotypes similar to that of wild-type PhaM. (C) Truncation of the C terminus of PhaM (PhaMΔC) and replacement of positively charged lysine residues by isoleucine or aspartate residues as indicated induced the formation of large PHB granule clusters. This phenotype showed strong similarity to that of PhaMΔC-expressing cells. From left to right: bright field, eYFP channel, DAPI channel, merge of fluorescent channels, and merge of all channels. Scale bars correspond to 1 μm.

It has been previously shown by transmission electron microscopy that PhaM-overexpressing cells form more but very small PHB granules (29). The amount of accumulated PHB was not determined in that study. When we determined the effect of PhaM overexpression on the PHB contents, a substantial reduction in the PHB content, by 5 to 10% of the cellular dry weight in comparison to that for the wild type, was determined during growth on NB-gluconate medium. Interestingly, the PHB content of the PhaMΔC-overexpressing cells was between those of the PhaMWT-overexpressing and the wild-type cells (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

PhaM-eYFP does not form fluorescent foci in the absence of PHB synthase.

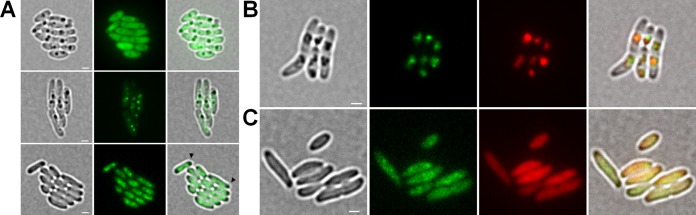

To study the time course of de novo PHB granule formation and its dependence on PhaM, we first constructed two strains in which the phaM gene was replaced by a phaM-eYFP gene fusion on the chromosome to avoid artifacts caused by plasmid-derived overexpression of phaM. The phaM-eYFP gene fusion was chromosomally integrated in wild-type and in PHB-negative (ΔphaC) backgrounds. We then followed expression of PhaM-eYFP under otherwise PHB-permissive conditions. While eYFP without a fusion partner is a cytoplasm-soluble protein in R. eutropha (Fig. 4A, top panels), the chromosomally expressed PhaM-eYFP fusion formed fluorescent foci that colocalized with accumulated PHB granules (Fig. 4A, middle panels). However, the PhaM-eYFP fluorescence was not as diffuse as in the case of the plasmid-derived overexpression of PhaM-eYFP (Fig. 2), and expression of wild-type levels of PhaM-eYFP did not affect number and size of PHB granules. When the PhaM-eYFP fusion was expressed in the PHB-negative background (ΔphaC strain), a homogeneous fluorescence was seen in the central parts (nucleoid region) of the cells. However, distinct foci as in the presence of formed PHB granules were not detected. The regions at the cell poles were free of PhaM-eYFP fluorescence (Fig. 4A, bottom panels, arrowheads). This finding indicated that PhaM-eYFP needs a PHB synthase or a PHB molecule to form foci. We assume that PhaM-eYFP binds to multiple locations in the nucleoid region in the absence of PhaC and PHB granules.

FIG 4.

Expression pattern of chromosomally integrated PhaM-eYFP in R. eutropha H16 cells in WT and ΔphaC backgrounds. (A) R. eutropha H16 WT cells harboring pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp (control) showed a uniformly distributed fluorescence within the cytoplasm (top panels). Formation of fluorescent foci was observed in R. eutropha H16 cells with a chromosomal integration of the phaM-eYFP gene (middle panels). In contrast, expression of the phaM-eYFP gene in ΔphaC cells resulted in a heterogeneously distributed fluorescence within the cytoplasm except in the areas of the cell poles (bottom panels, arrowheads). From left to right: bright field, eYFP channel, merge. (B) DsRed2EC-PhaC-driven formation of PHB granules induced the formation of fluorescent foci of PhaM-eYFP in a background of ΔphaC cells that colocalized with PHB granules (top panels). (C) Coexpression of PhaM-eYFP and DsRed2EC-PhaCC319A in the ΔphaC background showed a cytoplasmically distributed fluorescence (bottom panels). From left to right in panels B and C: bright field, eYFP channel, DsRed2EC channel, and merge of all channels. Scale bars correspond to 1 μm in all images.

Attachment of the PhaM-PhaC initiation complex to the nucleoid region requires the presence of active PHB synthase.

The introduction of a plasmid with a functional copy of the phaC gene (in form of a dsred2EC-phaC fusion) into a ΔphaC R. eutropha strain with a chromosomally integrated phaM-eYFP gene restored the ability of the cells to form PHB granules (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the diffuse PhaM-eYFP fluorescence of PHB-free ΔphaC cells condensed to foci and colocalized with formed PHB granules in the (central) nucleoid region in the presence of a functional PHB synthase. This finding suggested that the formation of PHB granules that are attached to the nucleoid requires the presence of PhaM and active PHB synthase or the presence of PhaM and PHB granules. To find out whether the PHB synthase itself or the PHB synthase-dependent formation of PHB granules was responsible for the formation of PhaM-eYFP foci, we transferred a plasmid harboring an inactive PHB synthase gene (dsRed2EC-phaC-Cys319Ala) to the ΔphaC R. eutropha strain with the chromosomally integrated phaM-eYFP gene fusion. Cultivation of this strain under otherwise PHB-permissive conditions (NB-gluconate medium) resulted in the same localization of PhaM-eYFP (fluorescence in the central cell parts with free cell poles) and in a similarly distributed dsRed2EC-PhaCC319A fluorescence (Fig. 4B). Formation of fluorescent foci (PhaM-eYFP attached to DsRed2EC-PhaC-Cys319Ala) was not observed. The principle ability of the inactive PHB synthase protein with the Cys319Ala mutation to bind to PHB granules was show previously by expression of a PhaCC319A-eYFP fusion in a wild-type background (see Fig. 1 in reference 35). Our results show that the ability of PhaM and PhaC to form foci requires the formation of PHB by active PHB synthase. We cannot, however, exclude that the distributed PhaM-eYFP and distributed DsRed2EC-PhaC-Cys319Ala fluorescence colocalize in vivo without focus formation in the absence of PHB.

Inactive PHB synthase (PhaCC319A) is not impaired in oligomerization and in binding to PhaM.

It is known that the active form of the R. eutropha PHB synthase is a homodimer (36). Homo-oligomerization of PhaC and conversion into a highly active form is enhanced in vitro by the addition of PhaM (32). To find out whether the inactive PHB synthase (PhaCC319A) is impaired in oligomerization and interaction with PhaM, we performed cross-linking experiments using purified PhaC with glutaraldehyde in the presence and absence of purified PhaM. The wild-type PHB synthase but also the inactive PHB synthase (PhaCC319A) existed in an equilibrium of monomers, dimers, and higher oligomers, as was revealed by the appearance of bands at the positions of monomers, dimers, and higher oligomers in cross-linking experiments with glutardialdehyde (Fig. 5). The addition of increasing amounts of PhaM decreased the fraction of the monomer for both the wild-type and the mutant PHB synthases. We conclude that the inactive mutant PHB synthase (PhaCC319A) is not impaired in oligomerization and in complex formation with PhaM. A consequence of this finding is that the largely homogeneous distribution of the inactive PhaCC319A protein in a ΔphaC background is not a result of insufficient dimerization and complex formation with PhaM.

FIG 5.

SDS-PAGE of PhaM, PhaC/PhaCC319A, and mixtures of PhaM with PhaC/PhaCC319A after chemical cross-linking. Oligomerization of His6-PhaC (A) or His6-PhaCC319A (B) and/or PhaM-His6 was analyzed using 2.5% glutardialdehyde as a cross-linking agent as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, marker proteins as indicated. Lanes 2 to 10: 8 μM PhaM without glutardialdehyde (lane 2), 14 μM PhaC without glutardialdehyde (lane 3), mixture of 8 μM PhaM and 14 μM PhaC without glutardialdehyde (lane 4), 8 μM PhaM with glutardialdehyde (lane 5), 14 μM PhaC with glutardialdehyde (lane 6), and mixtures of 14 μM PhaC with different amounts of PhaM and glutardialdehyde (1.3, 2.6, 5.2, and 7.8 μM PhaM in lanes 7 to 10, respectively).

Formation of PhaM foci at the nucleoid region precedes formation of visible PHB granules.

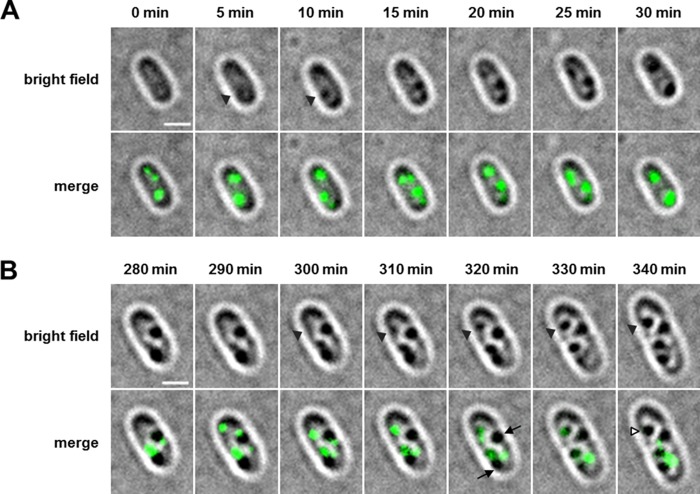

PhaM has a strong impact on the formation and localization of PHB granules due to its in vitro and in vivo affinities to DNA and to PHB synthase, as shown above. Next, we studied the time course of PHB granule formation and expression of a chromosomally integrated phaM-eYFP gene fusion in a wild-type background. To this end, cells were first depleted of previously accumulated PHB by two subsequent cultures in liquid NB medium, with the second culture incubating for at least 24 h at 30°C. These PHB-free cells were spotted onto NB-gluconate-agarose placed on special glass-bottom dishes and dried for 10 min. Formation of PHB granules and of PhaM-eYFP fluorescence was then followed microscopically. Remarkably, cells imaged at t = 0 min (corresponding to 10 min of exposure on PHB-permissive NB-gluconate medium) were free of any visible PHB granules but contained at least two PhaM-eYFP foci (Fig. 6). This indicated that under PHB-permissive conditions, PhaM constitutes an initiation complex with active PHB synthase and that this initiation complex is located at a few discrete regions. The first detectable PHB granule-like structure appeared after 5 min of incubation, clearly visible in the bright-field image, and colocalized with one of the PhaM-eYFP foci (Fig. 6A, arrowheads). Interestingly, when we followed PHB granule formation and localization of PhaM-eYFP foci at later stages of growth, we regularly detected PHB granules that did not colocalize with PhaM-eYFP foci (Fig. 6B, arrows), and the number of visible granules was higher than the number of PhaM-eYFP foci. This indicated that PHB granules at later stages of formation detach from the PhaM-PhaC-PHB-initiation complex. The disappearance of PhaM-eYFP foci is not caused by bleaching of the fluorophores, since PHB granules without PhaM-eYFP foci can be regularly found in cultures that have been imaged for the first time. The finding also explains why not all PHB granules at late stages of PHB accumulation are attached to the nucleoid region and can also be found near the cell poles.

FIG 6.

Time-lapse experiment with R. eutropha H16 cells expressing a chromosomally integrated phaM-eYFP gene. (A) PHB-free cells were transferred to fresh NB-gluconate agarose agar, and early PHB granule formation was immediately imaged every 5 min. At time point t = 0 min, fluorescent foci, but no PHB granules, are visible, and after 5 min a PHB granule that colocalizes with a fluorescent focus of PhaM-eYFP is formed (arrowheads at t = 5 and 10 min). (B) PHB granule formation was also imaged at later time points. Arrowheads show the formation of a PHB granule at the position of a preexisting fluorescent focus (top panels, t = 300 to 340 min). At later time points, a heterogeneity of PHB granules can be observed: while new PHB granules appear at the position of preexisting PhaM-eYFP foci, older PHB granules have lost PhaM-eYFP fluorescence (arrows in the cell at 320 min). White arrowheads in the cell at 340 min indicate a PHB granule that had a PhaM-eYFP focus at 310 to 330 min but lost this focus at 340 min. All pictures were taken with an exposure time of 500 ms. Scale bars correspond to 1 μm.

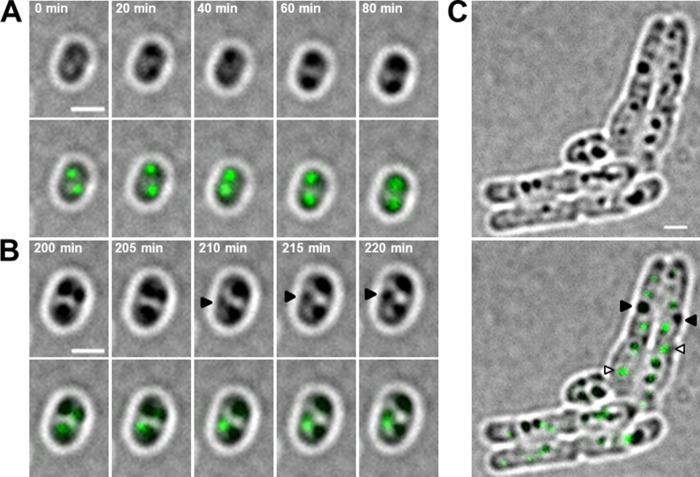

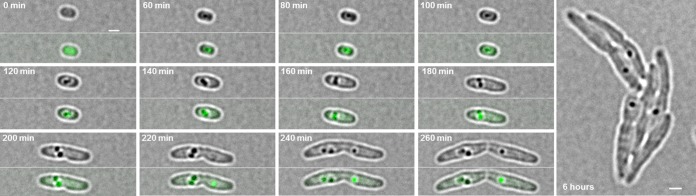

Very similar results were obtained when we followed the formation of PHB in a strain in which the phaC gene of the chromosome was replaced by a phaC-eYFP gene (Fig. 7). PHB granules appeared at preexisting PhaC-eYFP foci, and cells at the early stages of PHB granule formation usually formed two PHB granules. Interestingly, the two PHB granules were never located in the same cell half. The same observation was made when PHB granule formation was followed in the wild type via staining with Nile red (not shown). At later time points of growth, a detachment of the PhaC-eYFP fluorescence from PHB granules, similar to the detachment of PhaM-eYFP from PHB granules mentioned above (Fig. 6B), was frequently observed (Fig. 7C). A consequence of the formation of PHB granules always in both cell halves is that after cell division, both daughter cells get at least one of the formed PHB granules. This “fair” distribution of the storage granules was not observed in cells lacking the phaM gene. The experiment was started by a transfer of a PHB granule-deprived seed culture to fresh NB medium. The PhaC-eYFP fluorescence was homogeneously distributed at the beginning of the experiment but condensed to a focus, and a PHB granule appeared at the position of the PhaC-eYFP focus (Fig. 8). Interestingly, PhaC-eYFP foci did not appear as rapidly in a ΔphaM background as in a wild-type strain. This finding is in agreement with the positive effect of PhaM on PhaC oligomerization and increase in specific activity in vitro. Remarkably, a second PHB granule appeared very close to the first PHB granule, and after 200 min two prominent PHB granules that were present in the same cell half were formed. The cell started to divide, as visible by an invagination at midcell at 200 min. It is evident that one of the future daughter cells will get both PHB granules, while the other daughter cell will get none of the two synthesized storage granules. Since the nutrients of the medium were not yet exhausted at 200 min, the PHB-free daughter cell started to form its own (new) PHB granule (Fig. 8, 220 min). At later stages (6 h), cells either had a PHB granule or were free of any PHB. Interestingly, PHB granules without any attached PhaC-eYFP fluorescence were detected at later stages of PHB accumulation. This confirmed the result with wild-type cells shown above that the PhaM protein detaches from the PHB granules at later stages of growth (Fig. 8, 6 h).

FIG 7.

Time-lapse experiment with R. eutropha H16 cells expressing a chromosomally integrated phaC-eYFP gene. (A) PHB-free cells were transferred to fresh NB agar and dried for 10 min. Early PHB granule formation was then imaged every 20 min. (B) PHB granule formation was additionally analyzed at later time points at 5-min intervals. Arrowheads show the formation of a PHB granule at the position of a preexisting fluorescent focus. (C) After 9 h of incubation at 30°C, heterogeneity of PHB granules that do or do not colocalize with PhaC-eYFP can be observed. Black arrowheads indicate PHB granules without fluorescence, while PHB granules with a fluorescent focus are highlighted by white arrowheads. Pictures were taken with an exposure time of 500 ms. Scale bars correspond to 1 μm. Bright-field images are shown in the top panels, and overlays of bright field and the eYFP channel are shown in the bottom panels.

FIG 8.

Time-lapse experiment with R. eutropha H16 cells expressing a chromosomally encoded phaC-eYFP gene in a ΔphaM background. PHB-free cells were transferred to fresh NB agar and dried for 10 min. PHB granule formation was imaged microscopically. At time point 0 min, the fluorescence of PhaC-eYFP was soluble, and the first fluorescent foci were observed during PHB granule formation (60 min). At later time points (260 min), the PhaC-eYFP fluorescence showed no colocalization with all formed PHB granules. Pictures were taken with an exposure time of 500 ms. Scale bars correspond to 1 μm.

Conclusions.

In this contribution we identified the four lysine residues of the two C-terminal PAKKA motifs of PhaM that were essential for the binding of PhaM to DNA in vitro and in vivo. PHB granule formation in R. eutropha is initiated by the formation of a PhaM-PhaC initiation complex that forms at least two discrete nucleoid-associated foci and gives rise to two PHB granules, each in one cell half. Formation and distribution of PHB granules to daughter cells are disordered in the absence of PhaM. At later stages of growth and PHB granule formation, PhaM and PhaC detach from formed PHB granules, and this detachment can explain why a PHB granule does not grow ad infinitum. Instead, when PHB-permissive conditions prevail, initiation of new PHB granules is favored over an ongoing growth of preexisting PHB granules.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. E. coli JM109 and E. coli XL-1 Blue were used for cloning procedures. Recombinant proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLys. All E. coli strains were grown on lysogeny broth (LB) medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics (depending on the strains and plasmids). R. eutropha H16 strains were grown on nutrient broth (NB) (0.8%, wt/vol) medium with or without sodium gluconate (0.2%, wt/vol) at 30°C.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| PhaM_deletion C-terminus_fwd | CCTCCGCCGGCACGTGAAAGCCCGCCGCC |

| PhaM_deletion C-terminus_rev | GGCGGCGGGCTTTCACGTGCCGGCGGAGG |

| PhaM_K1-2I_fwd | GCACGGGCATTCCCGCCGCCAGGATCGCGCCGG |

| PhaM_K1-2I_rev | CCGGCGCGATCCTGGCGGCGGGAATGCCCGTGC |

| PhaM_K3-4I_fwd | GCGCCGGCAATTATTGCGCCGGCCATCAAGGCGGCCA |

| PhaM_K3-4I_rev | TGGCCGCCTTGATGGCCGGCGCAATAATTGCCGGCGC |

| PhaM_K5-8I_fwd | GCCGGCCATCATTGCGGCCATCGCAATTCCGGCCAGGGAC |

| PhaM_K5-8I_rev | GTCCCTGGCCGGAATTGCGATGGCCGCAATGATGGCCGGC |

| PhaM_K3-4I(2)_fwd | AAGCGCCGGCAATTATTGCGCCGGCCAAAAA |

| PhaM_K3-4I(2)_rev | TTTTTGGCCGGCGCAATAATTGCCGGCGCTT |

| PhaM_K5-6I_fwd | ATTGCGCCGGCCATTATTGCGGCCAAGGCAAA |

| PhaM_K5-6I_rev | TTTGCCTTGGCCGCAATAATGGCCGGCGCAAT |

| PhaM_K3-4E_fwd | GGAAAGCGCCGGCAGAGGAGGCGCCGGCCAAAA |

| PhaM_K3-4E_rev | TTTTGGCCGGCGCCTCCTCTGCCGGCGCTTTCC |

| PhaM_K5-6E_fwd | GAGGAGGCGCCGGCCGAAGAGGCGGCCAAGGCAAAA |

| PhaM_K5-6E_rev | TTTTGCCTTGGCCGCCTCTTCGGCCGGCGCCTCCTC |

| PhaM_P218A_fwd | GGCACGGGCAAGGCCGCCGCCAGGAAAGCG |

| PhaM_P218A_rev | CGCTTTCCTGGCGGCGGCCTTGCCCGTGCC |

| PhaM_P224A_fwd | GCCAGGAAAGCGGCGGCAAAGAAGGCG |

| PhaM_P224A_rev | CGCCTTCTTTGCCGCCGCTTTCCTGGC |

| PhaM_P229A_fwd | GCAAAGAAGGCGGCGGCCAAAAAGGCGGCC |

| PhaM_P229A_rev | GGCCGCCTTTTTGGCCGCCGCCTTCTTTGC |

| PhaM_P238A_fwd | GCCAAGGCAAAAGCGGCCAGGGACGCCG |

| PhaM_P238A_rev | CGGCGTCCCTGGCCGCTTTTGCCTTGGC |

| PhaM_P224H_fwd | CGCCAGGAAAGCGCACGCAAAGAAGGCG |

| PhaM_P224H_rev | CGCCTTCTTTGCGTGCGCTTTCCTGGCG |

| PhaM_P229H_fwd | GCAAAGAAGGCGCACGCCAAAAAGGCG |

| PhaM_P229H_rev | CGCCTTTTTGGCGTGCGCCTTCTTTGC |

| PhaM_fwd_SacI | CGAGCTCGCCCGAGGCCATGCAGTC |

| eYFP(PhaM)_rev_PacI | CCTTAATTAAGGTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCCGAGAGTGATCCCGG |

| HR(PhaM)_fwd_PacI | CCTTAATTAACCGCCAGATACTCCGACAAATCGTCCACACCAACGC |

| HR(PhaM)_rev_XbaI | GCTCTAGACGCACCGCTGTCCAGGCTGGCC |

| PhaC_fwd_SacI | CGAGCTCAAGGTACCGGGCAAGCTGACCG |

| eYFP(PhaC)_rev_PacI | CCTTAATTAAGGTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCCGAGAGTGATCCCG |

| HR(PhaC)_fwd_PacI | CCTTAATTAACGCTTGCATGAGTGCCGGCGTGC |

| HR(PhaC)_rev_XbaI | GCTCTAGACGACGATCATGGTGTCGACCAGCTTGG |

| PhaC(C319A)_fwd_NdeI | CCCATATGGCGACCGGCAAAGGCGCG |

| PhaC(C319A)_rev_BamHI | CGGGATCCTCATGCCTTGGCTTTGACGTATCGCCCAG |

| PhaC(C319A)dsRed_fwd_XhoI | CCGCTCGAGGCATGGCGACCGGCAAAGG |

| PhaC(C319A)dsRed_rev_BamHI | CGGGATCCTCATGCCTTGGCTTTGACGTATCGCCCAGG |

| pET28a-PhaC(C319A)_fwd | CGTGCTCGGCTTCGCCGTGGGCGGCAC |

| pET28a-PhaC(C319A)_rev | GTGCCGCCCACGGCGAAGCCGAGCAC |

Construction of fluorescent fusion proteins.

Molecular cloning of mutated genes for PhaM fusion proteins with enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) as a fluorophore was performed using pBBR1MCS2-PphaC-eyfp-phaM as the template vector. This plasmid allowed the constitutive expression of the fluorescent fusion protein in R. eutropha. The desired base substitutions in phaM were inserted by site-directed mutagenesis PCR, subsequent incubation with DpnI, and transformation into E. coli XL-1 Blue. The mutation(s) was verified by DNA sequencing. All constructs were transformed into E. coli and were conjugatively transferred from recombinant E. coli S17-1 to R. eutropha H16. Selection was achieved using mineral salts medium agar plates (37) supplemented with 0.5% fructose and 350 μg ml−1 kanamycin. Molecular cloning of the genes for fusion proteins with DsRed2EC was performed using the pCM62-PphaC-dsRed2EC-c1 vector harboring the constitutive promoter of the phaCAB operon. The genes for PhaC and PhaCC319A were cloned into the vector. The constructs were subsequently transformed into E. coli and conjugatively transferred from recombinant E. coli S17-1 to R. eutropha H16.

Chromosomal integration of gene fusions for fluorescent proteins.

Precise chromosomal integrations of the eYFP gene downstream of the phaM or phaC gene were obtained using the sacB-sucrose selection method (10% sucrose was used for selection) with pLO3 as an insertion vector as described previously (38). The eYFP gene was placed between homology regions of the respective genomic region, resulting in correct integration at the site of interest. Removal of the stop codons of the phaM and phaC genes allowed for wild-type-level expression of the proteins PhaM-eYFP and PhaC-eYFP, respectively. The genotypes of all generated constructs were verified by PCR amplification and sequencing.

Construction of expression plasmids.

Molecular cloning of the gene for His6-PhaCC319A was performed using pET28a-phaC as the template vector (32). The desired mutation (C319A) was inserted by site-directed mutagenesis PCR, treatment with DpnI, and transformation into E. coli XL-1 Blue. The insertion of the mutation was verified by DNA sequencing. The expression plasmids encoding the respective PhaM muteins were constructed similarly using pET28a-phaM as the template (39).

Overexpression and purification of His6-tagged proteins.

Overexpression of His6-PhaCC319A was performed in recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLys harboring pET28a-phaCC319A by induction with 0.1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 and subsequent incubation overnight at 26°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and disrupted with a French press (3 passages). After ultracentrifugation, His6-PhaCC319A was purified in the presence of 0.05% (wt/vol) Hecameg via Ni-agarose chromatography according to a protocol described in detail previously (32). Imidazole and other low-molecular-weight molecules were removed by size exclusion chromatography (HiPrep 26/10 desalting column, 53-ml bed volume) and exchanged against 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 5% (vol/vol) glycerol and 0.05% (wt/vol) Hecameg. Purified His6-PhaCC319A was concentrated to 3.5 mg/ml via ultrafiltration and was then shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Purification of PhaM-His6 muteins was performed similarly; 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) with 150 mM NaCl was used for purified PhaM-His6 muteins.

Fluorescence microscopy.

Fluorescence microscopy experiments were performed with a Nikon Ti-E microscope (MEA53100) equipped with F41-007 Cy3 and F41-54 Cy2 filters for the analysis of the fluorescent proteins (mCherry, DsRed2EC, and eYFP). Pictures were taken with a digital camera (Hamamatsu Orca Flash 4.0 sCMOS camera) and processed with Nikon imaging software. The fluorophore eYFP was detected with the aid of a standard filter set (excitation, 500/24 nm; emission, 542/27 nm). Another standard filter set (excitation, 562/40 nm; emission, 594 nm [long-pass filter]) was used for the detection of the red fluorescent proteins mCherry and dsRed2EC as well as for visualization of Nile red-stained PHB granules (1 μg/ml Nile red solution in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]). DNA was stained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (60 μg/ml) and detected with a DAPI-DNA-specific filter set (excitation, 387/11 nm; emission, 447/60 nm). Overnight experiments were performed on NB agar pads (0.8% [wt/vol]). To this end, the cells were dropped on the NB agar pad, dried for a few minutes, and then microscopically analyzed. The incubation chamber of the microscope was set to the optimal growth temperature for R. eutropha (30°C). The cells were imaged every 5 min with an exposure time of 500 ms.

EMSA.

A PCR-generated DNA fragment labeled with biotin-11-dUTP (eYFP-c1 DNA, 824 bp, 0.62 nM in each experiment) was incubated with purified His6-tagged proteins in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) with 150 mM NaCl for 20 min at room temperature. Alternatively, genomic DNA of R. eutropha was used in the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) described in the supplemental material. After electrophoresis on a 6% (wt/vol) native polyacrylamide gel, the DNA was transferred via electroblotting to a positively charged nylon membrane at 55 V for 1 h and subsequently fixed by UV cross-linking for 15 min. Biotinylated DNA-protein complexes were detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin and nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolylphosphate (NBT-BCIP) as substrates. Alternatively, the DNA bands with or without attached PhaM protein were separated on a 0.7% (wt/vol) agarose gel for 1 h and visualized after conventional staining with ethidium bromide under UV light.

Cross-linking.

For in vitro cross-linking studies, different mixtures (10-μl total volume) of PhaM (1.4 mg/ml), PhaC (2.2 mg/ml), or PhaCC319A (3.5 mg/ml) were mixed in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 5% (vol/vol) glycerol (pH 7.5) and incubated on ice for 30 min before 0.5 μl of a freshly prepared glutardialdehyde (1,5-pentanedial) solution (2.5%) was added. The mixture was subsequently incubated at 37°C for 5 min, and the reaction was stopped by addition of 1 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8). Samples were mixed with SDS loading buffer and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequent staining with colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 overnight.

Other techniques.

The PHB synthase assay was performed using dl-3-hydroxybutyryl coenzyme A as the substrate in the continuous assay in the presence of Ellman's reagent (dithionitrobenzoate [DTNB]) as described in detail previously (32). Quantitative analysis of PHB contents was done by gas chromatography (GC) analysis after acid methanolysis of lyophilized cells according to a method described previously (40). The PHB content of the samples was determined using three biological and three technical replicates each. Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed under denaturing (sodium dodecyl sulfate) and reducing (β-mercaptoethanol) conditions. Silver staining was routinely used for gel development, expect for cross-linking experiments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00505-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cao C, Yudin Y, Bikard Y, Chen W, Liu T, Li H, Jendrossek D, Cohen A, Pavlov E, Rohacs T, Zakharian E. 2013. Polyester modification of the mammalian TRPM8 channel protein: implications for structure and function. Cell Rep 4:302–315. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsuda H, Shiraki M, Inoue E, Saito T. 2016. Generation of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate from acetate in higher plants: detection of acetoacetyl CoA reductase and PHB synthase activities in rice. J Plant Physiol 201:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson AJ, Dawes EA. 1990. Occurrence, metabolism, metabolic role, and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiol Rev 54:450–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madison LL, Huisman GW. 1999. Metabolic engineering of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates): from DNA to plastic. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 63:21–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pötter M, Steinbüchel A. 2006. Biogenesis and structure of polyhydroxyalkanoate granules. Microbiol Monogr 1:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jendrossek D, Pfeiffer D. 2014. New insights in the formation of polyhydroxyalkanoate granules (carbonosomes) and novel functions of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate). Environ Microbiol 16:2357–2373. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sznajder A, Pfeiffer D, Jendrossek D. 2015. Comparative proteome analysis reveals four novel polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) granule-associated proteins in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:1847–1858. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03791-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu G, Cai S, Hou J, Zhao D, Han J, Zhou J, Xiang H. 2016. Enoyl-CoA hydratase mediates polyhydroxyalkanoate mobilization in Haloferax mediterranei. Sci Rep 6:24015. doi: 10.1038/srep24015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grage K, Jahns AC, Parlane N, Palanisamy R, Rasiah IA, Atwood JA, Rehm BHA. 2009. Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoate granules: biogenesis, structure, and potential use as nano-/micro-beads in biotechnological and biomedical applications. Biomacromolecules 10:660–669. doi: 10.1021/bm801394s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stubbe J, Tian J, He A, Sinskey AJ, Lawrence AG, Liu P. 2005. Nontemplate-dependent polymerization processes: polyhydroxyalkanoate synthases as a paradigm. Annu Rev Biochem 74:433–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rehm BHA. 2003. Polyester synthases: natural catalysts for plastics. Biochem J 376:15–33. doi: 10.1042/bj20031254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sznajder A, Jendrossek D. 2014. To be or not to be a poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) depolymerase: PhaZd1 (PhaZ6) and PhaZd2 (PhaZ7) of Ralstonia eutropha, highly active PHB depolymerases with no detectable role in mobilization of accumulated PHB. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:4936–4946. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01056-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mezzina MP, Pettinari MJ. 2016. Phasins, multifaceted polyhydroxyalkanoate granule-associated proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:5060–5067. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01161-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isabel de Eugenio L, Galan B, Escapa IF, Maestro B, Sanz JM, Luis Garcia J, Prieto MA. 2010. The PhaD regulator controls the simultaneous expression of the pha genes involved in polyhydroxyalkanoate metabolism and turnover in Pseudomonas putida KT2442. Environ Microbiol 12:1591–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuchta K, Chi L, Fuchs H, Pötter M, Steinbüchel A. 2007. Studies on the influence of phasins on accumulation and degradation of PHB and nanostructure of PHB granules in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Biomacromolecules 8:657–662. doi: 10.1021/bm060912e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wittenborn EC, Jost M, Wei Y, Stubbe J, Drennan CL. 14 October 2016. Structure of the catalytic domain of the class I polyhydroxybutyrate synthase from Cupriavidus necator. J Biol Chem doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.756833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim Y-J, Choi SY, Kim J, Jin KS, Lee SY, Kim K-J. 2017. Structure and function of the N-terminal domain of Ralstonia eutropha polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase, and the proposed structure and mechanisms of the whole enzyme. Biotechnol J doi: 10.1002/biot.201600649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Kim Y-J, Choi SY, Lee SY, Kim K-J. 2017. Crystal structure of Ralstonia eutropha polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase C-terminal domain and reaction mechanisms. Biotechnol J doi: 10.1002/biot.201600648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jendrossek D. 2009. Polyhydroxyalkanoate granules are complex subcellular organelles (carbonosomes). J Bacteriol 191:3195–3202. doi: 10.1128/JB.01723-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bresan S, Sznajder A, Hauf W, Forchhammer K, Pfeiffer D, Jendrossek D. 2016. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) granules have no phospholipids. Sci Rep 6:26612. doi: 10.1038/srep26612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruth K, de Roo G, Egli T, Ren Q. 2008. Identification of two acyl-CoA synthetases from Pseudomonas putida GPo1: one is located at the surface of polyhydroxyalkanoates granules. Biomacromolecules 9:1652–1659. doi: 10.1021/bm8001655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maestro B, Galan B, Alfonso C, Rivas G, Prieto MA, Sanz JM. 2013. A new family of intrinsically disordered proteins: structural characterization of the major phasin PhaF from Pseudomonas putida KT2440. PLoS One 8:e56904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jendrossek D. 2005. Fluorescence microscopical investigation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) granule formation in bacteria. Biomacromolecules 6:598–603. doi: 10.1021/bm049441r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hermawan S, Jendrossek D. 2007. Microscopical investigation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) granule formation in Azotobacter vinelandii. FEMS Microbiol Lett 266:60–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jendrossek D, Selchow O, Hoppert M. 2007. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) granules at the early stages of formation are localized close to the cytoplasmic membrane in Caryophanon latum. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:586–593. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01839-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moldes C, Garcia P, García JL, Prieto MA. 2004. In vivo immobilization of fusion proteins on bioplastics by the novel tag BioF. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:3205–3212. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3205-3212.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galan B, Dinjaski N, Maestro B, de Eugenio LI, Escapa IF, Sanz JM, Garcia JL, Prieto MA. 2011. Nucleoid-associated PhaF phasin drives intracellular location and segregation of polyhydroxyalkanoate granules in Pseudomonas putida KT2442. Mol Microbiol 79:402–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfeiffer D, Wahl A, Jendrossek D. 2011. Identification of a multifunctional protein, PhaM, that determines number, surface to volume ratio, subcellular localization and distribution to daughter cells of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate), PHB, granules in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Mol Microbiol 82:936–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wahl A, Schuth N, Pfeiffer D, Nussberger S, Jendrossek D. 2012. PHB granules are attached to the nucleoid via PhaM in Ralstonia eutropha. BMC Microbiol 12:262. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho M, Brigham CJ, Sinskey AJ, Stubbe J. 2012. Purification of polyhydroxybutyrate synthase from its native organism, Ralstonia eutropha: implications for the initiation and elongation of polymer formation in vivo. Biochemistry 51:2276–2288. doi: 10.1021/bi2013596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ushimaru K, Tsuge T. 2016. Characterization of binding preference of polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis-related multifunctional protein PhaM from Ralstonia eutropha. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:4413–4421. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-7225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfeiffer D, Jendrossek D. 2014. PhaM is the physiological activator of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) synthase (PhaC1) in Ralstonia eutropha. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:555–563. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02935-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anuchin AM, Goncharenko AV, Demidenok OI, Kaprelyants AS. 2011. Histone-like proteins of bacteria. Appl Biochem Microbiol 47:580–585. doi: 10.1134/S0003683811060020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kushwaha AK, Grove A. 2013. C-terminal low-complexity sequence repeats of Mycobacterium smegmatis Ku modulate DNA binding. Biosci Rep 33:175–184. doi: 10.1042/BSR20120105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfeiffer D, Jendrossek D. 2012. Localization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) granule-associated proteins during PHB granule formation and identification of two new phasins, PhaP6 and PhaP7, in Ralstonia eutropha H16. J Bacteriol 194:5909–5921. doi: 10.1128/JB.00779-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jia Y, Yuan W, Wodzinska J, Park C, Sinskey AJ, Stubbe J. 2001. Mechanistic studies on class I polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) synthase from Ralstonia eutropha: class I and III synthases share a similar catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry 40:1011–1019. doi: 10.1021/bi002219w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlegel HG, Bartha Von R, Gottschalk G. 1961. Formation and utilization of poly-beta-hydroxybutyric acid by Knallgas Bacteria (Hydrogenomonas). Nature 191:463–465. doi: 10.1038/191463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lenz O, Friedrich B. 1998. A novel multicomponent regulatory system mediates H-2 sensing in Alcaligenes eutrophus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:12474–12479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfeiffer D, Jendrossek D. 2013. Development of a transferable bimolecular fluorescence complementation system for the investigation of interactions between poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) granule-associated proteins in Gram-negative bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:2989–2999. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03965-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brandl H, Gross RA, Lenz RW, Fuller RC. 1988. Pseudomonas oleovorans as a source of poly(beta-hydroxyalkanoates) for potential applications as biodegradable polyesters. Appl Environ Microbiol 54:1977–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon R, Priefer R, Pühler A. 1983. A broad host-range mobilization system for in vivo engeneering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marx CJ, Lidstrom ME. 2001. Development of improved versatile broad-host-range vectors for use in methylotrophs and other Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 147:2065–2075. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.