Our findings, in combination with the nutrient deprivation and oxidative stress associated with the post-transarterial embolization (TAE)/transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) microenvironment, suggest that autophagy may represent an optimal and even necessary target for adjunct therapy in TAE/TACE.

Abstract

Purpose

To characterize hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells surviving ischemia with respect to cell cycle kinetics, chemosensitivity, and molecular dependencies that may be exploited to potentiate treatment with transarterial embolization (TAE).

Materials and Methods

Animal studies were performed according to institutionally approved protocols. The growth kinetics of HCC cells were studied in standard and ischemic conditions. Viability and cell cycle kinetics were measured by using flow cytometry. Cytotoxicity profiling was performed by using a colorimetric cell proliferation assay. Analyses of the Cancer Genome Atlas HCC RNA-sequencing data were performed by using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software. Activation of molecular mediators of autophagy was measured with Western blot analysis and fluorescence microscopy. In vivo TAE was performed in a rat model of HCC with (n = 5) and without (n = 5) the autophagy inhibitor Lys05. Statistical analyses were performed by using GraphPad software.

Results

HCC cells survived ischemia with an up to 43% increase in the fraction of quiescent cells as compared with cells grown in standard conditions (P < .004). Neither doxorubicin nor mitomycin C potentiated the cytotoxic effects of ischemia. Gene-set analysis revealed an increase in mRNA expression of the mediators of autophagy (eg, CDKN2A, PPP2R2C, and TRAF2) in HCC as compared with normal liver. Cells surviving ischemia were autophagy dependent. Combination therapy coupling autophagy inhibition and TAE in a rat model of HCC resulted in a 21% increase in tumor necrosis compared with TAE alone (P = .044).

Conclusion

Ischemia induces quiescence in surviving HCC cells, resulting in a dependence on autophagy, providing a potential therapeutic target for combination therapy with TAE.

© RSNA, 2017

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, with more than 745 000 fatalities in 2012 alone (1). Surgical resection or liver transplantation remain the therapies of choice; however, fewer than 20% of patients with HCC are candidates for resection, and the role of transplantation is limited by a static donor pool and HCC progression precluding transplant eligibility (2). Transarterial embolization (TAE) and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) represent endovascular local-regional embolotherapies, involving hepatic artery embolization with or without intra-arterial infusion of a chemotherapeutic agent. TACE is considered the standard of care for intermediate-stage, unresectable HCC (3,4). While TAE/TACE has a proven survival benefit, local recurrence is common, and long-term survival rates are poor (49% after complete response for a 72-month median follow-up) (5,6). Optimal therapy is limited by a paucity of proven adjuvant therapies to potentiate embolotherapy-induced ischemia. Prospective randomized trials have demonstrated TACE and TAE to be equally effective with respect to survival, and none of the currently used chemotherapeutic agents has demonstrated superiority to others (7–13).

TAE/TACE exploits the vascular biology of HCC to deprive tumors of oxygen and essential nutrients, leading to growth arrest and/or necrosis. However, current therapies induce transient arterial occlusion, with a limited number of treated lesions demonstrating extensive necrosis at pathologic examination, indicating that tumor cells develop an adaptive response to nutrient deprivation (14–17). This adaptive response is reflected by the presence of viable tumor cells adjacent to necrotic regions at histopathologic examination and is consistent with the clinical phenomenon of local recurrence following a brief latency period that is observed at follow-up imaging (16,18,19). Importantly, preclinical models reveal that HCC cells capable of surviving TAE-mediated ischemia demonstrate an invasive phenotype with an associated increase in metastases (20). These findings emphasize the importance of further characterizing HCC cells surviving the ischemia induced by TAE/TACE to develop targeted therapies that potentiate the embolic effects.

Recent advances in cancer biology have demonstrated that cancer cells undergo adaptations to promote survival in hypoxic conditions; however, a detailed characterization of HCC cells capable of surviving severe TAE/TACE-like ischemia and the essential pathways enabling this survival has been limited, in part by the paucity of available tissue samples following treatment. We hypothesized that HCCs may be epigenetically preprogrammed to survive severe, TACE-like ischemia through activation of the targetable survival mechanism autophagy. The purpose of our study was to characterize HCC cells surviving severe ischemia with respect to cell cycle kinetics, chemosensitivity, and a molecular dependency on autophagy that may be exploited to potentiate TAE in vivo.

Materials and Methods

The authors received support from Merit Medical (South Jordan, Utah) in the form of Embospheres but had control of the data and the information submitted for publication. Complete experimental details are given in Appendix E1 (online).

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

HepG2, SNU-449, SNU-387, and SNU-398 cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va). Additional cell lines were generated by transduction with a lentivirus encoding for a green fluorescent protein-microtubule–associated protein light chain 3 fusion protein (hereafter, LC3-GFP) by using a previously described plasmid (plasmid 11546, Addgene, Cambridge, Mass) (21). In vitro experiments were performed following exposure of cells to standard conditions (21% oxygen with standard media, including Roswell Park Memorial Institute [RPMI] medium, 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], and 10 mmol/L glucose) or ischemic conditions (1% or 0.5% oxygen with ischemic media, including RPMI, 1% FBS, and 1 mmol/L glucose). For repletion experiments, cells grown in ischemic conditions for 24 hours were subsequently grown in standard conditions for 48 hours. Hypoxic conditions (1%, 0.5%) were achieved in an In VivO2 400 workstation (Baker Ruskinn, Bridgend, Wales).

Cellular Growth Kinetics

Cell numbers were determined after 24, 72, 120, and 168 hours of incubation (n = 3 per time point) in standard or ischemic conditions by using a Countess Automated Cell Counter (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). For repletion experiments, cells grown in ischemic conditions for 168 hours were subsequently grown in standard conditions for 168 hours and were counted at 192, 240, 288, and 336 hours following the start of incubation (n = 3 per time point). Data points were fit to the exponential growth equation y = y0exp (kx), where x is time in hours, y0 is the cell number at time zero, and k is the rate constant, or to the linear growth equation y = mx + b, where x is time in hours, b is the cell number at time zero, and m is the slope. Tumor doubling times were derived from the rate constants or slopes of these fits, respectively.

Cellular Viability and Cell Cycle Analyses

Cellular viability was determined by using flow cytometry based on staining for Annexin V-FITC and/or propidium iodide (BD Biosciences, San Jose, Calif). Cell cycle phase was determined by using flow cytometry based on staining for the nuclear protein Ki-67 and/or Hoechst dye.

Analyses of RNA-sequencing Data from the Cancer Genome Atlas Database

Raw RNA-sequencing data for 300 HCC tumors and 50 normal liver tissues were downloaded from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) HCC project (http://cancergenome.nih.gov) on October 1, 2015. To perform the gene-set analyses, a comprehensive list of 20 531 genes encoding all mRNA that demonstrated altered expression levels were identified. Two hundred seven previously identified autophagy-associated genes were surveyed (22). In addition, analyses of the TCGA data were performed for the six enzymes constituting the urea cycle as annotated by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/). The cutoff value for fold change was set to +1.1 for autophagy-associated genes and to −1.1 for urea cycle genes, while the false-discovery rate was set to less than 0.03% to exclude genes not consistently detected with RNA sequencing. A Fisher exact test was performed to compare the proportions of samples with fold changes higher than these thresholds in tumor as compared with uninvolved hepatic parenchyma.

Immunofluorescence

Slides were imaged in oil immersion at 60× within 48–72 hours of sealing. Automated quantitation of punctae was performed as described previously (23).

Cytotoxicity Assays

Cellular viability was measured by using the CytoScan WST-1 Assay (G-Biosciences, St Louis, Mo). Spectrophotometric measures of absorbance were made by using a SpectraMax M2e microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, Calif). On the basis of these data, dose-response curves were generated by applying a standard four-parameter logistic equation from which the concentration of the assayed agent required to inhibit growth by 50% (hereafter, IC50) was calculated.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein quantitation was performed by using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Mass). Anti-p62 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Tex). Anti-LC3 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, Mass). These experiments were performed by T.P.F.G., M.S.N., and W.W., who had 7 years of experience in cancer research.

In Vivo Rat Model

Animal studies were performed according to institutionally approved protocols for the safe and humane treatment of animals. Autochthonous HCCs were induced in Wistar rats (n = 10, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass) by using ad libitum oral intake of 0.01% diethylnitrosamine for 12 weeks (24). Rats with liver tumors 0.5–1.0 cm in diameter at preprocedure T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) imaging were selected for treatment and were randomized into one of two cohorts, including (a) segmental TAE alone (n = 5) or (b) intra-arterial administration of the previously described autophagy inhibitor Lys05 (40 mg/kg) with subsequent segmental TAE (n = 5) (25). The percentage of necrosis in each HCC from the treated segment that was identified at necropsy, as well as in an HCC of similar size in an adjacent, untreated lobe (n = 4), was quantified on hematoxylin-eosin–stained slices by a gastrointestinal pathologist (E.E.F., with more than 25 years of experience in evaluating post-TAE/TACE HCC specimens). Lys05 was designed, synthesized, and tested at the University of Pennsylvania (R.K.A., J.W.D.). Intellectual property covering Lys05 and its derivatives is owned by the University of Pennsylvania and has been licensed to Presage Biosciences (Seattle, Wash).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses and curve fittings were performed with the use of GraphPad Prism, version 6.02 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, Calif). Values are reported as means ± standard deviations. The two-tailed unpaired t test was performed to assess the statistical significance of differences in mean values for normally distributed data.

Results

HCC Cells Survive Severe, Sustained, TAE-Like Ischemia

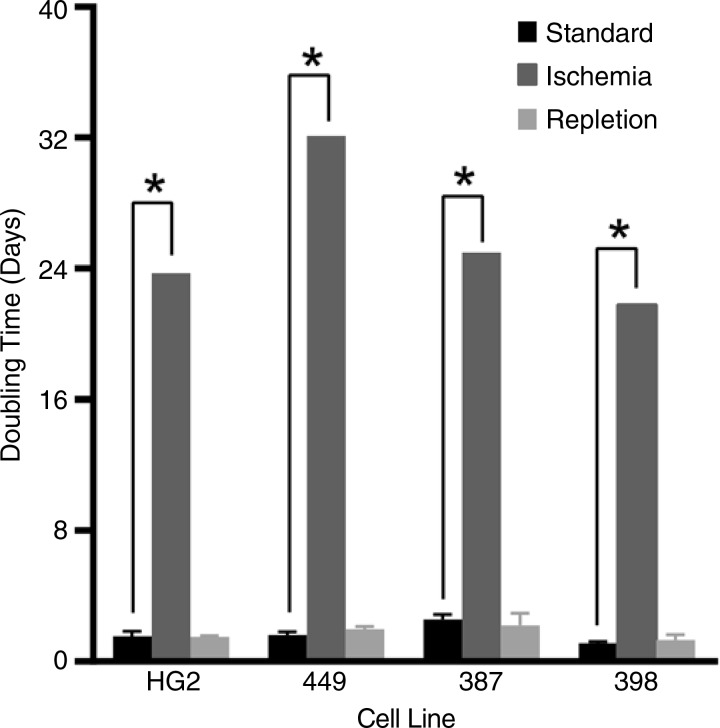

HCC cells (HepG2, SNU-449, SNU-387, and SNU-398) incubated in severe ischemia demonstrated sustained viability for up to 1 week without proliferation, as indicated by a linear regression of the measured cell counts demonstrating a slope not significantly different from zero, as compared with doubling times of 1.8 days ± 0.2, 1.6 days ± 0.2, 2.6 days ± 0.3, and 1.1 days ± 0.1, respectively, in standard conditions (Fig 1; Fig E1, A [online]). To mimic the reperfusion that follows TAE/TACE, cells incubated in severe ischemia for 1 week were subsequently incubated in replete conditions. Despite the growth latency that characterized cells cultured in severe ischemia, each cell line regained an exponential growth kinetic following repletion that was similar to the growth kinetic demonstrated by cells grown in standard conditions, suggesting the capability to re-enter the cycle (Fig 1; Fig E1, B).

Figure 1:

Graph shows that HCC cells survive severe, sustained, TAE-like ischemia. HepG2, SNU-449, SNU-387, and SNU-398 cells showed exponential growth when grown in standard conditions and absent proliferation when grown in severe ischemia, with linear regression demonstrating a slope that was not significantly different from zero. The median estimated doubling times (23.7, 32, 25, and 22 days, respectively) are included for the purpose of comparison (* = P < .001). After incubation for 1 week in severe ischemia, each of the four cell lines assayed was able to redemonstrate exponential growth on subsequent incubation in standard conditions (repletion), with doubling times not significantly different from those of cells never grown in ischemic conditions (P value range: .0749–.4967).

Severe Ischemia Induces Quiescence in Surviving HCC Cells

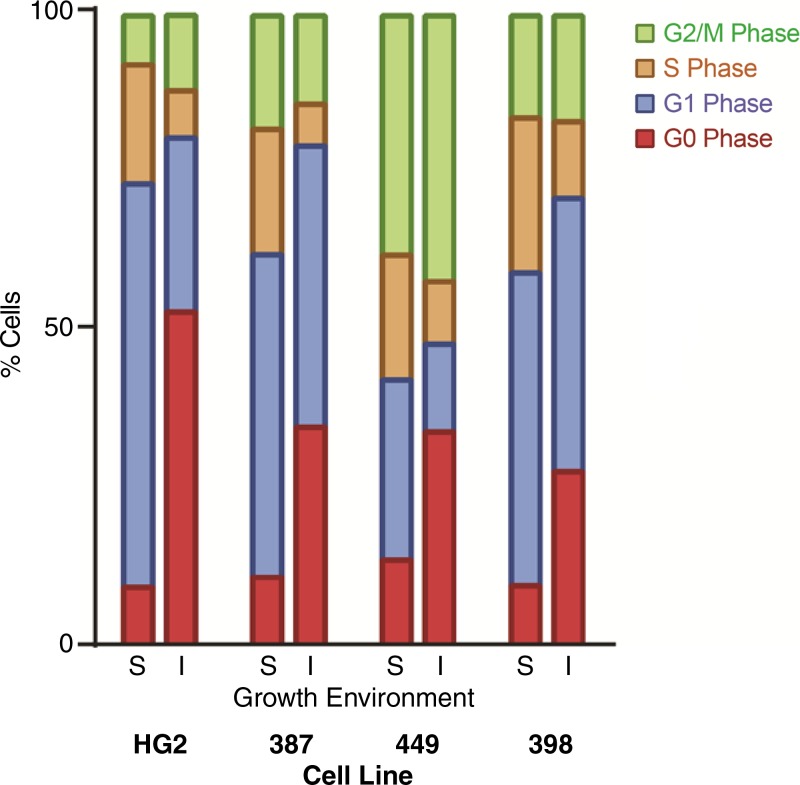

Each of the four cell lines tested demonstrated a significant increase in the fraction of cells with 2N DNA content, with up to 79% of cells in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle when incubated in severe ischemia (P value range: .03–.004, Fig 2; Fig E2, A [online]). The majority of this increase was observed in cells in the G0 phase of the cell cycle (ranging 27%–52% for severe ischemia vs 9%–13% for standard conditions; P value range: .0006–.004). There was an associated decrease in the fraction of cells in the S phase of the cell cycle, from 19%–24% to 6%–12%, indicating a reduced proportion of actively dividing cells (P value range: .0011–.0005). Consistent with the demonstrated ability of surviving cells to regain exponential growth, the increased proportion of G0 cells suggested that severe ischemia induced cellular quiescence, which was confirmed by the upregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 in each of the four cell lines (Fig E2, B [online]).

Figure 2:

Graph shows that severe ischemia induces quiescence in surviving HCC cells. Analysis of flow cytometry data for HepG2, SNU-387, SNU-449, and SNU-398 cell lines revealed an increase in the proportion of G0-phase cells and a decrease in the proportion of S phase cells after incubations in standard (S) versus severely ischemic (I) growth conditions (G0 phase: 51.9% ± 0.8 vs 8.8% ± 0.6, P < .0001; S phase: 7.3% ± 0.3 vs 19% ± 0.5, P < .0001).

Severe Ischemia Fails to Potentiate the Therapeutic Effects of Conventional Chemotherapeutic Agents in Surviving HCC Cells

Severe ischemia failed to potentiate the cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin (Fig E3, A, B [online]). Surprisingly, severe ischemia decreased the sensitivity of HepG2 and SNU-449 cells (Fig E3, A, B [online]). Severe ischemia similarly failed to potentiate the cytotoxic effects of mitomycin C, with no significant differences observed in standard conditions or severe ischemia (Fig E3, C, D [online]).

HCC Cells Surviving Severe Ischemia Activate an Autophagic Stress Response

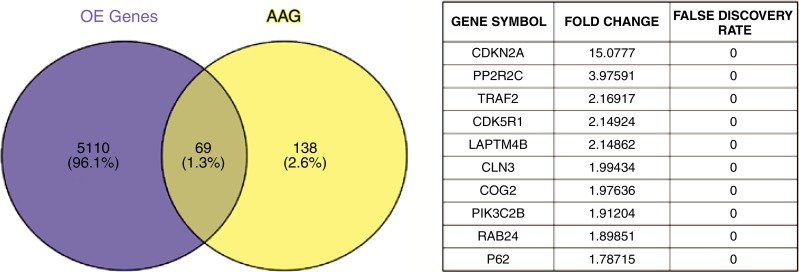

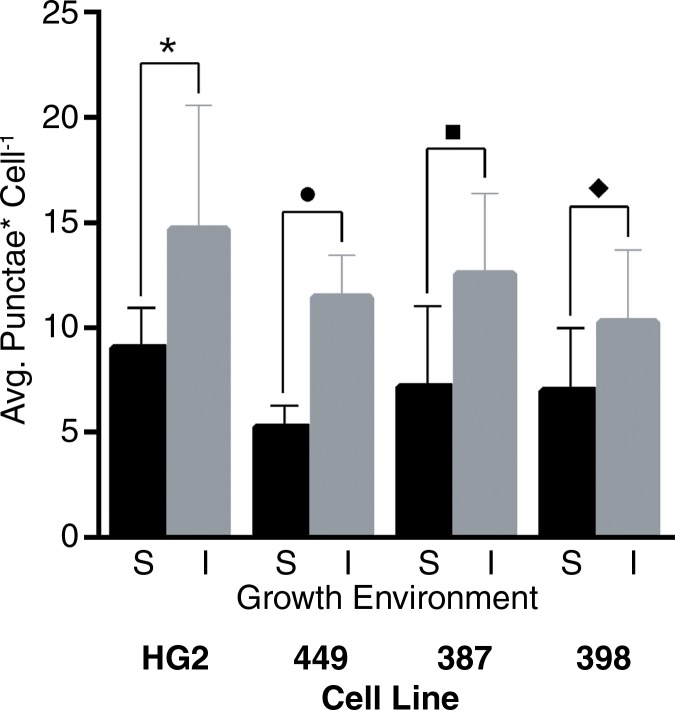

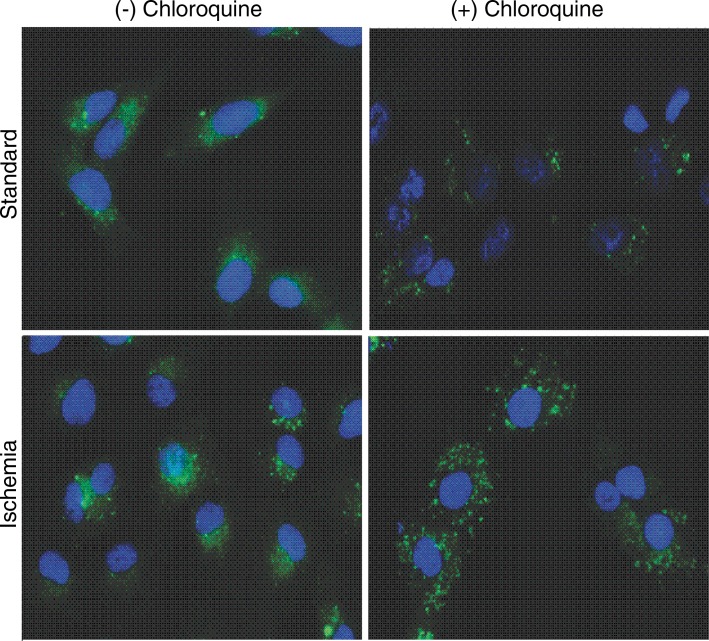

Analyses of TCGA HCC RNA-sequencing data demonstrated a significant increase in RNA expression of autophagy-associated genes in HCCs as compared with normal hepatic parenchyma (Fig 3a). Further analyses of TCGA data demonstrated a marked decrease in expression of each of the enzymes that constitute the urea cycle in HCCs as compared with normal hepatic parenchyma (Fig E4, A [online]). These findings were underscored by substantial autophagic flux in each cell line in standard conditions in vitro, as indicated by the accumulation of proteins that are normally degraded by autophagy but increase when autophagy is inhibited by chloroquine, including conjugated LC3 (LC3II) and the p62 adapter protein (Fig E4, B [online]). Incubation in severe ischemia resulted in an increase in autophagic flux, as demonstrated by a relative increase in the accumulation of LC3II and p62 in the presence of chloroquine (Fig E4, B [online]). Consistent with the protein levels demonstrated at Western blot analysis, quantification of LC3-GFP punctae in cells incubated in ischemia demonstrated a significant increase in autophagic flux in ischemic cells (Fig 3c).

Figure 3a:

Images show that basal activation of autophagy in HCC cells is enhanced in cells surviving severe ischemia. (a) Venn diagram of a gene-set analysis shows the significantly increased expression of RNA for autophagy-associated genes (A AG) relative to all overexpressed genes (OE) in HCCs (P = .0098) and a table of fold increases and false-discovery rates of 10 of the most highly expressed autophagy-associated genes. (b) Representative immunofluorescence microscopic images show increased autophagic flux in SNU-449 cells in ischemia relative to cells in standard conditions, as indicated by an increase in LC3-GFP punctae when incubated with chloroquine. (c) Graph of quantitative analysis of punctae formation shows a significant increase in autophagic flux for cells incubated in severe ischemia with 10 µm chloroquine relative to that in cells incubated in standard conditions with 10 µm chloroquine. Avg. = average. (* = P = .05, ● = P = .0090, ■ = P = .0052, ♦ = P = .033).

Figure 3c:

Images show that basal activation of autophagy in HCC cells is enhanced in cells surviving severe ischemia. (a) Venn diagram of a gene-set analysis shows the significantly increased expression of RNA for autophagy-associated genes (A AG) relative to all overexpressed genes (OE) in HCCs (P = .0098) and a table of fold increases and false-discovery rates of 10 of the most highly expressed autophagy-associated genes. (b) Representative immunofluorescence microscopic images show increased autophagic flux in SNU-449 cells in ischemia relative to cells in standard conditions, as indicated by an increase in LC3-GFP punctae when incubated with chloroquine. (c) Graph of quantitative analysis of punctae formation shows a significant increase in autophagic flux for cells incubated in severe ischemia with 10 µm chloroquine relative to that in cells incubated in standard conditions with 10 µm chloroquine. Avg. = average. (* = P = .05, ● = P = .0090, ■ = P = .0052, ♦ = P = .033).

Figure 3b:

Images show that basal activation of autophagy in HCC cells is enhanced in cells surviving severe ischemia. (a) Venn diagram of a gene-set analysis shows the significantly increased expression of RNA for autophagy-associated genes (A AG) relative to all overexpressed genes (OE) in HCCs (P = .0098) and a table of fold increases and false-discovery rates of 10 of the most highly expressed autophagy-associated genes. (b) Representative immunofluorescence microscopic images show increased autophagic flux in SNU-449 cells in ischemia relative to cells in standard conditions, as indicated by an increase in LC3-GFP punctae when incubated with chloroquine. (c) Graph of quantitative analysis of punctae formation shows a significant increase in autophagic flux for cells incubated in severe ischemia with 10 µm chloroquine relative to that in cells incubated in standard conditions with 10 µm chloroquine. Avg. = average. (* = P = .05, ● = P = .0090, ■ = P = .0052, ♦ = P = .033).

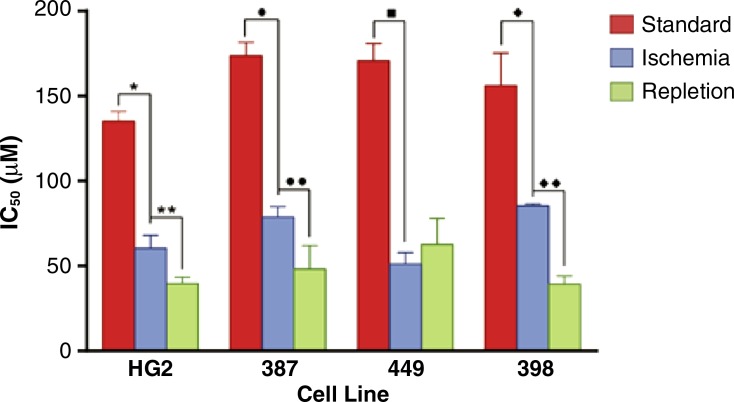

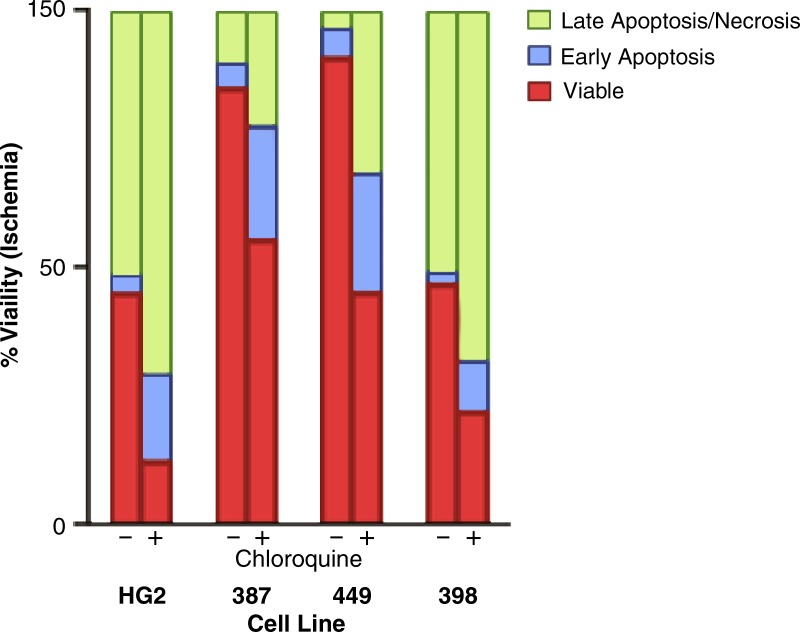

HCC Cells Surviving Severe Ischemia Are Autophagy Dependent

HCC cells surviving severe ischemia were dependent on autophagy, as evidenced by a dramatic reduction in the IC50 of the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine relative to cells incubated in standard conditions (Fig 4a; Fig E5, A [online]). Experiments designed to mimic reperfusion after failed TAE/TACE demonstrated the further potentiation of the effects of autophagy inhibition, with three of the four cell lines assayed demonstrating a significant decrease in the chloroquine IC50 relative to cells grown in ischemic conditions alone (maximum 2.4-fold, SNU-398; minimum 1.5-fold, HepG2; Fig 4a, Fig E5, A [online]). In each of the assayed cell lines, viability assays demonstrated a minimum of a 1.6-fold decrease (SNU-387) and as much as a 3.5-fold decrease (HepG2) in the viable cell fractions for cells incubated in severe ischemia with chloroquine relative to cells incubated in severe ischemia alone (Fig 4b; Fig E5, B [online]). This decrease was associated with a marked increase in the early apoptotic and late apoptotic/necrotic fractions. In contrast, no statistically significant difference was observed in viable fractions for three of the four cell lines incubated in standard conditions, with or without chloroquine (P value range: .0796–.3765), with SNU-449 cells demonstrating a 1.05-fold decrease in viable cells; P = .0058; Fig E5, C [online]).

Figure 4a:

Graphs show that HCC cells surviving severe ischemia are autophagy dependent. (a) Graph of average IC50 values for chloroquine in HCC cells incubated in standard or ischemic conditions shows potentiation of the inhibitory effects of chloroquine for cells incubated in severe ischemia relative to those in cells incubated in standard conditions (HepG2: 60 µM ± 7 vs 135 µM ± 5, * = P = .0002; SNU-387: 79 µM ± 6 vs 174 µM ± 8, ● = P < .0001; SNU-449: 51 µM ± 4 vs 171 µM ± 6, ■ = P < .0001; SNU-398: 85 µM ± 1 vs 156 µM ± 15, ♦ = P = .0031). The inhibitory effects of chloroquine were further potentiated in three of the four cell lines tested after incubation in conditions designed to mimic reperfusion after TAE/TACE, including exposure to severe ischemia followed by incubation in standard conditions, relative to cells incubated with chloroquine in severe ischemia alone (HepG2: 40 µM ± 4, ** = P = .0133; SNU-387: 48 µM ± 13, ●● = P = .0253; SNU-449: 63 µM ± 15, P = .276; SNU-398: 39 µM ± 4, ♦♦ = P < .0001). (b) Graph shows mean viable, necrotic, late apoptotic/necrotic, and early apoptotic fractions of HCC cells incubated in severe ischemia alone or severe ischemia with chloroquine (80 µM). Cells incubated in severe ischemia demonstrated a marked decrease in the fraction of viable cells (HepG2: 12% ± 0.3 vs 43% ± 2, P < .0001; SNU-387: 53% ± 2 vs 85% ± 1, P < .0001; SNU-449: 44% ± 4 vs 90% ± 1, P < .0001; SNU-398: 21% ± 1 vs 46% ± 5, P = .0009), as well as a marked increase in the fraction of early apoptotic cells (HepG2: 18% ± 4 vs 3% ± 1, P < .0032; SNU-387: 23% ± 3 vs 4% ± 1, P = .0003; SNU-449: 24% ± 4 vs 5% ± 1, P = .0021; SNU-398: 10% ± 0.6 vs 2% ± 0.6, P = .0001) and late apoptotic/necrotic cells (HepG2: 71% ± 2 vs 51% ± 1, P = .0002; SNU-387: 22% ± 1 vs 9% ± 2, P = .0005; SNU-449: 31% ± 1 vs 3% ± 0.6, P < .0001; SNU-398: 21% ± 1 vs 46% ± 5, P = .0009).

Figure 4b:

Graphs show that HCC cells surviving severe ischemia are autophagy dependent. (a) Graph of average IC50 values for chloroquine in HCC cells incubated in standard or ischemic conditions shows potentiation of the inhibitory effects of chloroquine for cells incubated in severe ischemia relative to those in cells incubated in standard conditions (HepG2: 60 µM ± 7 vs 135 µM ± 5, * = P = .0002; SNU-387: 79 µM ± 6 vs 174 µM ± 8, ● = P < .0001; SNU-449: 51 µM ± 4 vs 171 µM ± 6, ■ = P < .0001; SNU-398: 85 µM ± 1 vs 156 µM ± 15, ♦ = P = .0031). The inhibitory effects of chloroquine were further potentiated in three of the four cell lines tested after incubation in conditions designed to mimic reperfusion after TAE/TACE, including exposure to severe ischemia followed by incubation in standard conditions, relative to cells incubated with chloroquine in severe ischemia alone (HepG2: 40 µM ± 4, ** = P = .0133; SNU-387: 48 µM ± 13, ●● = P = .0253; SNU-449: 63 µM ± 15, P = .276; SNU-398: 39 µM ± 4, ♦♦ = P < .0001). (b) Graph shows mean viable, necrotic, late apoptotic/necrotic, and early apoptotic fractions of HCC cells incubated in severe ischemia alone or severe ischemia with chloroquine (80 µM). Cells incubated in severe ischemia demonstrated a marked decrease in the fraction of viable cells (HepG2: 12% ± 0.3 vs 43% ± 2, P < .0001; SNU-387: 53% ± 2 vs 85% ± 1, P < .0001; SNU-449: 44% ± 4 vs 90% ± 1, P < .0001; SNU-398: 21% ± 1 vs 46% ± 5, P = .0009), as well as a marked increase in the fraction of early apoptotic cells (HepG2: 18% ± 4 vs 3% ± 1, P < .0032; SNU-387: 23% ± 3 vs 4% ± 1, P = .0003; SNU-449: 24% ± 4 vs 5% ± 1, P = .0021; SNU-398: 10% ± 0.6 vs 2% ± 0.6, P = .0001) and late apoptotic/necrotic cells (HepG2: 71% ± 2 vs 51% ± 1, P = .0002; SNU-387: 22% ± 1 vs 9% ± 2, P = .0005; SNU-449: 31% ± 1 vs 3% ± 0.6, P < .0001; SNU-398: 21% ± 1 vs 46% ± 5, P = .0009).

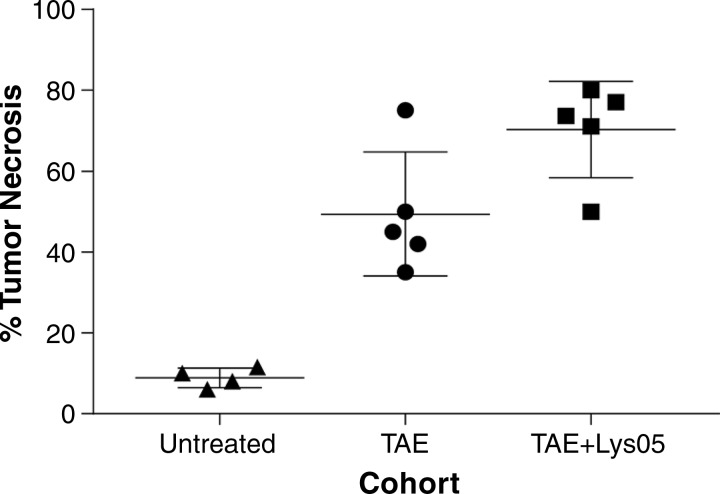

Combination Therapy with Autophagy Inhibition Augments the Therapeutic Effects of TAE in Vivo

We compared the degree of tumor necrosis in autochthonous rat HCC tumors that were (a) untreated, (b) treated with TAE alone, or (c) treated with TAE after the intra-arterial administration of the autophagy inhibitor Lys05. There were no significant differences in the size of the tumors from these three groups at the time of treatment, with average maximal transverse diameters of 0.8 cm ± 0.08, 0.9 cm ± 0.04, and 0.8 cm ± 0.06, respectively (P ≥ .2924). Superselective catheterization of segmental arteries enabled direct administration of embolic agents alone or in combination with Lys05 to the segmental artery of the targeted tumor (Fig E6, A, B [online]). No significant difference was observed between the number of treated tumors in the two treatment groups (TAE: n = 1.8 ± 0.8; TAE plus Lys05: n = 2 ± 1; P = .7404). Tumors treated with combination therapy demonstrated a significant increase in necrosis compared with tumors treated with TAE alone (Fig 5; Fig E6, C, D [online]; 70.3% ± 11.9 vs 49.4% ± 15.3; P = .044). Tumors treated with TAE alone and TAE plus Lys05 demonstrated a significant increase in percentage necrosis as compared with untreated tumors (8.8% ± 1.2; P = .0014 and P < .0001, respectively; Fig 5). No significant differences were found for overall survival in rats treated with TAE compared with those treated with TAE plus Lys05, with median survivals of 11 and 13 days, respectively (P = .3442).

Figure 5:

Scatterplot of percentage tumor necrosis in tumors from untreated rats, as well as from rats treated with TAE alone and rats treated with TAE plus Lys05, shows that inhibition of autophagy potentiates the cytotoxic effects of TAE in vivo.

Discussion

The characterization of cells surviving severe ischemia provides insights into persistent issues surrounding the role of adjunct therapies administered with TAE, including the relative roles of the induced ischemia and the cytotoxic effect of chemotherapy. The rationale for the combined use of embolization and chemotherapy is based on the concept that the induced ischemic microenvironment will potentiate the cytotoxic effect of the chemotherapeutic agent by augmenting intracellular retention and overcoming resistance mechanisms (26,27); however, there remains limited evidence for this potentiation (28). The chemotherapeutic agents used with TACE have focused on cell cycle–specific agents that target proliferating cells and to which HCCs have demonstrated chemoresistance (10,29). Our data suggest that the cell cycle dependence of these agents may represent an additional mechanism for the insensitivity of HCC cells in nutrient-limited conditions, demonstrating that severe ischemia induces G0 cell cycle arrest and fails to potentiate the therapeutic effect of doxorubicin or mitomycin C in surviving HCC cells. In addition, our data underscore the importance of chemoresistance in considering conventional therapies used with TACE. The previously established high expression of the multidrug resistance gene (MDR1) in SNU-449 cells accounts for the marked difference in IC50 for doxorubicin (26). The wide variation in IC50 between cell lines for doxorubicin and mitomycin C may explain some of the reported variations in response to TACE.

We examined the activation of autophagy in HCC cells surviving severe ischemia to identify additional targets for combination therapy. Although a variety of metabolic stress response pathways have been shown to enable cell survival in nutrient-deprived conditions, autophagy plays a central role in facilitating cellular quiescence (30). Recent studies have shown an important role for autophagy in hepatocellular disease. Elevated levels of LC3A have been demonstrated in HCC tissue samples relative to hepatic parenchyma (31). Targeting of autophagy in HCC cells has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation and overcome chemoresistance after short exposures to unsurvivable ischemia (32). Autophagy has been further shown to play an essential role in the replication of the hepatitis B and C viruses, as well as in the suppression of innate immunity to hepatitis C (33). Our findings, in combination with the nutrient deprivation and oxidative stress associated with the post-TAE/TACE microenvironment, suggest that autophagy may represent an optimal and even necessary target for adjunct therapy in TAE/TACE. The data reported herein strongly support this concept. Basal activation of autophagy was confirmed in TCGA analyses of HCCs and in HCC cells in vitro. TCGA analyses demonstrated silencing of the urea cycle enzymes in HCCs, indicating that basal activation of autophagy may result from the absence of a functioning urea cycle, given the established role of ammonia as an independent inducer of autophagy and the elevated serum levels of ammonia in patients with HCC due to cirrhosis and hepatocellular dysfunction (34,35). These data suggest that HCC cells may be epigenetically preprogrammed to survive severe, TACE-like ischemia through activation of autophagy. In addition, HCC cells surviving severe ischemia demonstrated a further activation of, and dependence on, autophagy. Incubation in conditions mimicking failed TAE/TACE enhanced this dependence in all but one cell line, suggesting the potentiation of the antitumor effect following reperfusion. The demonstrated increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) following small interfering RNA–mediated inhibition of autophagy after reperfusion of HCC cells indicates ROS-mediated injury as a mechanism for this phenomenon (32). Moreover, combination therapy with the intra-arterial administration of Lys05 and TAE resulted in an increase in tumor necrosis as compared with TAE alone, consistent with the findings of Gao et al (36), who demonstrated an enhanced therapeutic effect of the intra-arterial administration of chloroquine followed by TACE in fibroblast-like VX2 tumors implanted in rabbit livers. Lys05 was selected for the in vivo experiments on the basis of higher potency for autophagy inhibition, as well as for its consistent cellular uptake in the acidic microenvironments that are associated with ischemia as compared with chloroquine (37).

There were several limitations to our study. First, in vitro experiments were performed on immortalized human HCC lines, which may not reflect the genetic diversity of HCCs in vivo. Second, in vivo experiments were performed in a rat model of HCC, which may limit the extrapolation of the results to human HCCs. Finally, tumor size was not explicitly measured at necropsy, and differences in tumor size could have influenced differences in the degree of necrosis observed among the cohorts; however, there was no difference in the size of tumors prior to the experiment, and no objective differences in tumor size were noted at necropsy.

In summary, we describe the in vitro and in vivo characterization of HCC cells capable of surviving TAE/TACE-like severe ischemia. Severe ischemia induced cell cycle arrest in surviving HCC cells as well as a dependence on autophagy for this survival.

Practical application: Our findings suggest that that the tumor microenvironment can be co-opted using TAE so that tumor cell survival is dependent on the targetable subsistence mechanism autophagy, providing the rationale for an ongoing clinical trial (38).

Advances in Knowledge

■ Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells are capable of surviving severe ischemia, including oxygen tensions as low as 0.5%.

■ Severe ischemia induces quiescence in surviving HCC cells, with an up to 43% increase in the noncycling cell population, which may explain an observed decrease in the sensitivity of certain HCC cell lines to the cell cycle–specific chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin.

■ HCC cells surviving severe ischemia are dependent on autophagy for survival, and this dependence can be targeted to potentiate the cytotoxic effects of transarterial embolization (TAE)-induced ischemia in vivo, as demonstrated by a 21% increase in necrosis in tumors treated with the autophagy inhibitor Lys05 and TAE as compared with TAE alone.

Implication for Patient Care

■ TAE and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) confer a proven survival benefit in the treatment of HCC; however, improved survival has not yet been demonstrated for the concomitant use of conventional chemotherapeutics, but here we demonstrate that HCC cells capable of surviving severe TAE/TACE-like ischemia are autophagy dependent and that targeted autophagy inhibition potentiates the cytotoxic effects of TAE-induced ischemia in vivo, providing a rationale for clinical trials investigating this approach.

APPENDIX

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge John Tobias, PhD, and the Penn Genomics Analysis Core Bioinformatics Group for assistance in the analysis of TCGA RNA-sequencing data. The authors also acknowledge Hongwei Yu, PhD, and the Cancer Histology Core in the Perelman School of Medicine for their help in preparing and staining tumor slices.

Received April 5, 2016; revision requested June 15; revision received October 12; accepted November 21; final version accepted December 18.

T.P.F.G. supported in part by the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics of the University of Pennsylvania, the Radiological Society of North America (Research Resident Grant), the National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (T32 EB00431112), the Society for Interventional Radiology (SIR Pilot Grant), the National Center for Research Resources (UL1RR024134), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000003). M.C. Simon supported by the National Cancer Institute (P01 CA104838).

See also Science to Practice in this issue.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: T.P.F.G. disclosed no relevant relationships. E.T. disclosed no relevant relationships. M.S.N. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.J.H. disclosed no relevant relationships. W.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. B.K. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.N.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. G.J.N. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: has received grants from Guerbet and Teleflex Medical; is a consultant for Teleflex Medical. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. T.W.I.C. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: is a consultant for Merit Medical and Teleflex; receives royalties from Merit Medical and Teleflex. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. M.C. Soulen Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: has received grants from Guerbet and BTG International; has received personal fees from Guerbet, Sirtex Medical, Terumo Medical, and Bayer. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. E.E.F. disclosed no relevant relationships. J.D.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. R.K.A. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: receives money from Presage Biosciences for a licensed patent; receives royalties from Presage Biosciences; holds stock or stock options in Presage Biosciences. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. M.C. Simon disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- HCC

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- TACE

- transarterial chemoembolization

- TAE

- transarterial embolization

- TCGA

- the Cancer Genome Atlas

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65(2):87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanematsu T, Furui J, Yanaga K, Okudaira S, Shimada M, Shirabe K. A 16-year experience in performing hepatic resection in 303 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: 1985-2000. Surgery 2002;131(1 Suppl):S153–S158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raoul JL, Sangro B, Forner A, et al. Evolving strategies for the management of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: available evidence and expert opinion on the use of transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer Treat Rev 2011;37(3):212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farinati F, De Maria N, Marafin C, et al. Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: survival, prognostic factors, and unexpected side effects after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41(12):2332–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin YJ, Chung YH, Kim JA, et al. Predisposing factors of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence following complete remission in response to transarterial chemoembolization. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58(6):1758–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takayasu K, Arii S, Ikai I, et al. Prospective cohort study of transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in 8510 patients. Gastroenterology 2006;131(2):461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawai S, Okamura J, Ogawa M, et al. Prospective and randomized clinical trial for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparison of lipiodol-transcatheter arterial embolization with and without adriamycin (first cooperative study). The Cooperative Study Group for Liver Cancer Treatment of Japan. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1992;31(Suppl):S1–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;359(9319):1734–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang JM, Tzeng WS, Pan HB, Yang CF, Lai KH. Transcatheter arterial embolization with or without cisplatin treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized controlled study. Cancer 1994;74(9):2449–2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, et al. Transarterial therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: which technique is more effective? a systematic review of cohort and randomized studies. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2007;30(1):6–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown KT, Do RK, Gonen M, et al. Randomized trial of hepatic artery embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using doxorubicin-eluting microspheres compared with embolization with microspheres alone. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(17):2046–2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malagari K, Pomoni M, Kelekis A, et al. Prospective randomized comparison of chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting beads and bland embolization with BeadBlock for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010;33(3):541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer T, Kirkwood A, Roughton M, et al. A randomised phase II/III trial of 3-weekly cisplatin-based sequential transarterial chemoembolisation vs embolisation alone for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2013;108(6):1252–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Gazzaz G, Sourianarayanane A, Menon KV, et al. Radiologic-histological correlation of hepatocellular carcinoma treated via pre-liver transplant locoregional therapies. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2013;12(1):34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riaz A, Kulik L, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Radiologic-pathologic correlation of hepatocellular carcinoma treated with internal radiation using yttrium-90 microspheres. Hepatology 2009;49(4):1185–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higuchi T, Kikuchi M, Okazaki M. Hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization. A histopathologic study of 84 resected cases. Cancer 1994;73(9):2259–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung JW. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 1998;45(Suppl 3):1236–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tezuka M, Hayashi K, Kubota K, et al. Growth rate of locally recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization: comparing the growth rate of locally recurrent tumor with that of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci 2007;52(3):783–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forner A, Ayuso C, Varela M, et al. Evaluation of tumor response after locoregional therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma: are response evaluation criteria in solid tumors reliable? Cancer 2009;115(3):616–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu L, Ren ZG, Shen Y, et al. Influence of hepatic artery occlusion on tumor growth and metastatic potential in a human orthotopic hepatoma nude mouse model: relevance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Sci 2010;101(1):120–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson WT, Giddings TH, Jr, Taylor MP, et al. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol 2005;3(5):e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebovitz CB, Robertson AG, Goya R, et al. Cross-cancer profiling of molecular alterations within the human autophagy interaction network. Autophagy 2015;11(9):1668–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dagda RK, Zhu J, Kulich SM, Chu CT. Mitochondrially localized ERK2 regulates mitophagy and autophagic cell stress: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Autophagy 2008;4(6):770–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha WS, Kim CK, Song SH, Kang CB. Study on mechanism of multistep hepatotumorigenesis in rat: development of hepatotumorigenesis. J Vet Sci 2001;2(1):53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAfee Q, Zhang Z, Samanta A, et al. Autophagy inhibitor Lys05 has single-agent antitumor activity and reproduces the phenotype of a genetic autophagy deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109(21):8253–8258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park JG, Lee SK, Hong IG, et al. MDR1 gene expression: its effect on drug resistance to doxorubicin in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994;86(9):700–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruskal JB, Hlatky L, Hahnfeldt P, Teramoto K, Stokes KR, Clouse ME. In vivo and in vitro analysis of the effectiveness of doxorubicin combined with temporary arterial occlusion in liver tumors. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1993;4(6):741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakulterdkiat T, Srisomsap C, Udomsangpetch R, Svasti J, Lirdprapamongkol K. Curcumin resistance induced by hypoxia in HepG2 cells is mediated by multidrug-resistance-associated proteins. Anticancer Res 2012;32(12):5337–5342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeo W, Mok TS, Zee B, et al. A randomized phase III study of doxorubicin versus cisplatin/interferon alpha-2b/doxorubicin/fluorouracil (PIAF) combination chemotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97(20):1532–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valcourt JR, Lemons JM, Haley EM, Kojima M, Demuren OO, Coller HA. Staying alive: metabolic adaptations to quiescence. Cell Cycle 2012;11(9):1680–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xi SY, Lu JB, Chen JW, et al. The “stone-like” pattern of LC3A expression and its clinicopathologic significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013;431(4):760–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du H, Yang W, Chen L, et al. Emerging role of autophagy during ischemia-hypoxia and reperfusion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol 2012;40(6):2049–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Czaja MJ, Ding WX, Donohue TM, Jr, et al. Functions of autophagy in normal and diseased liver. Autophagy 2013;9(8):1131–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheong H, Lindsten T, Wu J, Lu C, Thompson CB. Ammonia-induced autophagy is independent of ULK1/ULK2 kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108(27):11121–11126. [Published correction appears in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108(43):17856.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Dong H, Robertson K, Liu C. DNA methylation suppresses expression of the urea cycle enzyme carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol 2011;178(2):652–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao L, Song JR, Zhang JW, et al. Chloroquine promotes the anticancer effect of TACE in a rabbit VX2 liver tumor model. Int J Biol Sci 2013;9(4):322–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pellegrini P, Strambi A, Zipoli C, et al. Acidic extracellular pH neutralizes the autophagy-inhibiting activity of chloroquine: implications for cancer therapies. Autophagy 2014;10(4):562–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.University of Pennsylvania . Phase 1-2 Trial HCQ Plus TACE in Unresectable HCC. clinicaltrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02013778?term=TACE+hydroxychloroquine&rank=1. Published 2013. Accessed October 14, 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.