Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) establishes a persistent infection, despite inducing antigen-specific T-cell responses. Although T cells arrive at the site of infection, they do not provide sterilizing immunity. The molecular basis of how Mtb impairs T-cell function is not clear. Mtb has been reported to block major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) antigen presentation; however, no bacterial effector or host-cell target mediating this effect has been identified. We recently found that Mtb EsxH, which is secreted by the Esx-3 type VII secretion system, directly inhibits the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery. Here, we showed that ESCRT is required for optimal antigen processing; correspondingly, overexpression and loss-of-function studies demonstrated that EsxH inhibited the ability of macrophages and dendritic cells to activate Mtb antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Compared with the wild-type strain, the esxH-deficient strain induced fivefold more antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation in the mediastinal lymph nodes of mice. We also found that EsxH undermined the ability of effector CD4+ T cells to recognize infected macrophages and clear Mtb. These results provide a molecular explanation for how Mtb impairs the adaptive immune response.

Host defences, both innate and adaptive, are subverted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). During Mtb infection, there is a delay in priming antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ cells by dendritic cells (DCs) in the lymph node1. When the effector CD4+ T cells traffic to the site of infection in the lungs, although they promote the antimycobacterial activity of macrophages by secreting cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ2, they fail to generate sterilizing immunity. Currently, we lack a comprehensive and detailed understanding as to why major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) antigen presentation fails during Mtb infection. In naive macrophages, Mtb can act through Toll-like receptor 2 to block IFN-γ-induced MHC-II transcription3–5, although the contribution this plays in vivo is unclear6. How Mtb impairs antigen presentation in macrophages already expressing MHC-II is less well understood. One proposed mechanism is that by blocking phagosome maturation Mtb impairs efficient processing of antigen and the MHC-II-associated invariant chain7,8. However, there have been contradictory results regarding the impact of phagosome maturation on antigen presentation8–11. Contradictory results have also been reported in DCs. Some studies have demonstrated that Mtb inhibits DCs maturation, thereby impairing mobilization of MHC-II molecules to the cell surface12, whereas others have shown that Mtb upregulates DC expression of MHC-II, co-stimulatory molecules and inflammatory cytokines13,14. More recent data have shown that Mtb-infected DCs are inefficient at priming antigen-specific CD4+ T cells15–17. Rather, bystander uninfected cells take up Mtb antigen and prime CD4+ T cells18,19.

Our group recently found that Mtb EsxH inhibits phagosome maturation by targeting the host endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)20. EsxH forms a heterodimer with EsxG (EsxGHMt), which is secreted by the Esx-3 type VII secretion system. EsxGHMt is involved in iron and zinc acquisition21–25, and recent work has demonstrated that EsxGHMt also plays an additional role in virulence20,26,27. EsxGHMt binds the host protein hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HGS, also known as HRS), a component of the ESCRT machinery20. ESCRT plays a well-described role in directing cell-surface receptors into intraluminal vesicles of multivesicular bodies so they can be degraded in the lysosome28. We found that ESCRT is also required for phagosome maturation20,29, and we hypothesized that ESCRT, and by extension EsxGHMt, regulates MHC-II antigen presentation. In this study, we showed that ESCRT promotes T-cell activation during Mtb infection by facilitating antigen processing. We demonstrated that EsxGHMt impairs the ability of macrophages and DCs to present mycobacterial antigens and activate CD4+ T cells, resulting in impaired T-cell priming and defective effector function. Overall, our data support a model in which EsxH inhibits ESCRT, thereby undermining two key aspects of the adaptive immune response: (1) efficient priming of naive T cells, and (2) recognition of Mtb-infected cells by CD4+ T cells.

Results

ESCRT promotes antigen presentation during Mtb infection

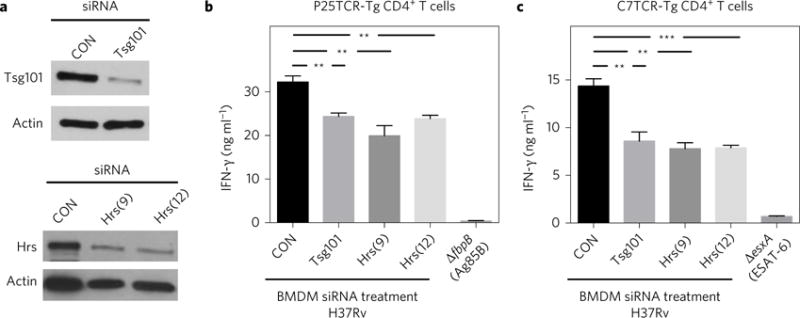

To test the hypothesis that ESCRT contributes to antigen presentation, we depleted HRS and TSG101, components of ESCRT-0 and ESCRT-I, from bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (Fig. 1a). Following ESCRT depletion, BMDMs were activated with IFN-γ to induce MHC-II expression and infected the following day with Mtb. The ability of the infected macrophages to activate CD4+ T cells was assessed using T-helper 1 (TH1) polarized CD4+ effector cells that express a transgenic T-cell antigen receptor (TCR-Tg) specific for peptide 25 (amino acids 240–254) of Mtb Ag85B protein (P25TCR-Tg TH1 cells)30, which secrete IFN-γ when co-cultured with Mtb-infected BMDMs. We found that macrophages depleted of HRS or TSG101 were poor at stimulating P25TCR-Tg effector CD4+ T cells, inducing 30% less IFN-γ release than control cells (Fig. 1b). Similar findings were observed with CD4+ TH1 cells specific for another prominent secreted antigen of Mtb, EsxA/ESAT-63–15 (C7TCR-Tg TH1 cells; Fig. 1c). IFN-γ production by P25 and C7 TCR TH1 cells was antigen specific, as IFN-γ was not made following co-culture with macrophages infected with Ag85B- or ESAT-6-null strains of Mtb (ΔfpbB and ΔesxA; Fig. 1b,c). Importantly, multiple independent small interfering RNAs (siRNA) targeting Tsg101 or Hrs impaired the ability of infected macrophages to stimulate T cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c), and the degree of HRS depletion correlated with levels of impairment in T-cell activation (Supplementary Fig. 1b,c). At the maximal HRS depletion that we were able to achieve, approximately 20% of HRS protein remained, and IFN-γ production was suppressed by approximately 40%. These results indicated that ESCRT promotes the ability of macrophages to activate Mtb-specific CD4+ effector T cells.

Figure 1. ESCRT promotes antigen presentation by Mtb-infected macrophages.

a, BMDMs were transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) pools targeting Tsg101, individual siRNAs targeting Hrs (numbers 9 and 12) or a non-targeting control (CON). After 96 h, the lysates were analysed by western blotting. Actin served as a loading control. Images shown are from one experiment, representative of at least three independent experiments. b,c, BMDMs were treated with siRNAs as indicated and infected 3 d later with Mtb H37Rv (multiplicity of infection of 3–5), ΔfbpB or ΔesxA strain. The following day, infected BMDMs were co-cultured for 24 h with P25TCR-Tg (b) or C7TCR-Tg (c) CD4+ T cells, and IFN-γ was measured from culture supernatants by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Results reflect the mean ± s.e.m. from at least four replicates and are representative of at least three independent experiments. **P = 0.005, ***P = 0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

ESCRT facilitates antigen processing by macrophages

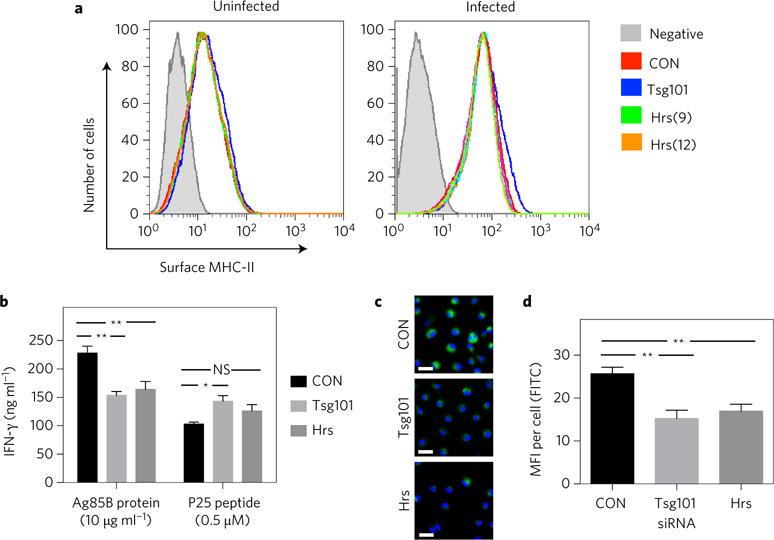

The role of ESCRT in antigen presentation has not been studied. In DCs, cell-surface levels of MHC-II are regulated by ubiquitin-dependent sorting to lysosomes31,32, suggesting that ESCRT might control MHC-II trafficking in DCs, although this has not been tested directly. Whether ESCRT would play a similar role in BMDMs is unclear. To assess this directly, we compared cell-surface MHC-II levels between control BMDMs and those depleted of HRS or TSG101. We found no difference, regardless of infection status, when assayed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2a). It is also possible that, by controlling the multivesicular architecture of the MHC-II compartment or promoting phagosome maturation20,29, ESCRT might influence antigen processing or loading. We found that ESCRT-depleted BMDMs were impaired for activating P25TCR-Tg CD4+ effector T cells in the presence of exogenously added recombinant Ag85B, but behaved similarly to controls when peptide 25 was used as the antigen (Fig. 2b), suggesting that the defect is at the level of processing the protein into peptide. To evaluate this further, we used DQ-OVA, a self-quenched conjugate of ovalbumin that exhibits bright green fluorescence on proteolytic degradation (Fig. 2c). Quantification of fluorescence indicated that ESCRT silencing impaired the degradation of ovalbumin (Fig. 2d). From these experiments, we concluded that ESCRT promotes antigen presentation by facilitating antigen processing.

Figure 2. ESCRT promotes antigen presentation by facilitating antigen processing.

a–d, BMDMs were treated with siRNAs targeting Hrs (numbers 9 and 12 in panel a, number 9 in b–d) or Tsg101 (pool). (a) Mtb-infected and uninfected BMDMs were immunostained with anti-mouse MHC-II (I-A/I-E) and analysed by flow cytometry. Shaded histograms indicate unstained controls. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (b) BMDMs were incubated with recombinant Ag85B protein or peptide P25 and co-cultured with P25TCR-Tg T cells. IFN-γ was measured by ELISA. Results reflect means ± s.e.m. from at least three replicates. (c) BMDMs were treated with DQ-OVA and the level of green fluorescence was determined using fluorescence microscopy. Images presented are representative of three independent experiments. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. Scale bars, 20 μm. d, Graph shows means ± s.e.m. of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of at least 50 cells for each condition. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (unpaired Student’s t-test); NS, not significant.

ESCRT does not restrict bacterial growth in IFN-γ-activated macrophages

Although Mtb arrests phagosome maturation, in naive macrophages a fraction of the bacilli are delivered to the lysosome, which we previously showed depends on ESCRT20. As IFN-γ partially overcomes the arrest in phagosome maturation imposed by Mtb33–35, we asked whether ESCRT is also involved in phagosome maturation in IFN-γ-activated macrophages, which we used for the antigen presentation assays. As we reported previously, silencing of Tsg101 and Hrs in naive macrophages did not decrease the total lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) signal but led to diminished co-localization between Mtb and LAMP1 (a marker of late endosomes and lysosomes) and enhanced intracellular bacterial growth when compared with control cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a,c,d)20. Surprisingly, in IFN-γ-activated macrophages, the same silencing had no effect on the co-localization of bacteria with LAMP1 or on bacterial survival (Supplementary Fig. 2b–d). Thus, phagolysosomal maturation and control of Mtb replication is largely independent of ESCRT in IFN-γ-activated macrophages. Therefore, the impairment in antigen presentation seen with ESCRT silencing is not due to an overall difference in bacterial degradation.

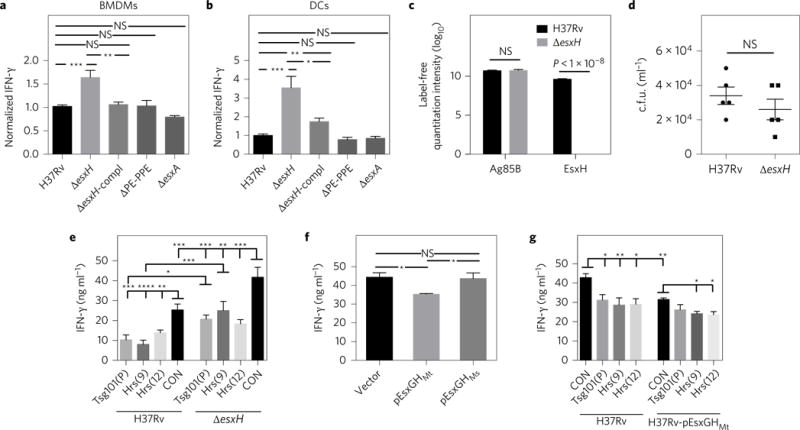

Antigen presentation is impaired by Mtb EsxGHMt but not by Mycobacterium smegmatis EsxGH

As EsxGHMt disrupts ESCRT20, we wondered whether EsxGHMt impairs antigen presentation. We found that macrophages infected with a ΔesxH mutant elicited 50% more T-cell activation compared with BMDMs infected with wild-type Mtb, as assessed by IFN-γ production (Fig. 3 a). Bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) showed an even more pronounced effect, as infection with the ΔesxH mutant resulted in a greater than threefold enhancement in T-cell activation (Fig. 3b). In both cases, the increase in T-cell activation was largely reversed by genetic complementation. The enhanced response was not due to more Ag85B secretion from the mutant (Fig. 3c). While the ΔesxH mutant requires exogenous siderophore to grow on solid medium, it is only modestly impaired in liquid medium26, and there was no difference in the intracellular survival of the wild type and ΔesxH at the time the antigen presentation assay was performed (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, when ESCRT was silenced, the ΔesxH mutant stimulated P25 T cells to a similar extent as control cells infected with wild-type Mtb (Fig. 3e), consistent with the idea that esxH impairs antigen presentation by inhibiting HRS. IFN-γ release was greatest in magnitude in the case of control cells infected with the ΔesxH mutant, whereas it was least in the context of ESCRT-silenced cells infected with Mtb strain H37Rv. The inhibition of IFN-γ by H37Rv relative to ΔesxH seen in ESCRT-silenced cells might reflect the fact that RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated silencing fails to fully deplete the target protein and that EsxGHMt expression does not fully inhibit ESCRT. Alternatively, EsxGHMt may have additional targets beyond HRS that suppress antigen presentation.

Figure 3. EsxGHMt impairs antigen presentation.

a,b, BMDMs (a) or DCs (b) were infected with Mtb H37Rv, ΔesxH (mc27846), ΔesxH complemented with EsxGH (ΔesxH-compl), Δpe5ppe4 (mc27848; ΔPE-PPE) or ΔesxA, and co-cultured with P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells. Results were normalized to H37Rv infection from at least three independent experiments and reflect means ± s.e.m. c, Mass spectrometry and label-free quantitation algorithms were used to determine normalized relative protein levels of Ag85B and EsxH in culture filtrate from the wild type and the ΔesxH mutant26. Results are combined from three independent experiments and reflect means ± s.e.m. d, Bacterial burden in H37Rv- or ΔesxH-infected BMDMs at 24 h postinfection. Results are representative of two independent experiments and reflect means ± s.e.m. e, BMDMs were treated with siRNA and infected with either H37Rv or ΔesxH and co-cultured with P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells as above. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the siRNA control (CON) sample with ESCRT-silenced samples for both H37Rv and ΔesxH infection. For each siRNA, H37Rv was compared with ΔesxH. Results are representative of three independent experiments and reflect means ± s.e.m. All significant results are indicated, f, BMDMs were infected with H37Rv containing empty vector, EsxGHMt or EsxGHMs for 24 h and co-cultured with P25TCR-Tg CD4+ effector T cells. Results are representative of two independent experiments and reflect means ± s.e.m. g, BMDMs were treated with the indicated siRNAs and infected with Mtb containing empty vector or EsxGHMt as indicated and co-cultured with P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the siRNA control sample with ESCRT-silenced samples for both vector control and EsxGHMt; the vector control strain was compared with the EsxGHMt strain for each siRNA treatment. Results are representative of three independent experiments and reflect means ± s.e.m. All significant differences are indicated. For a,b,e–g, IFN-γ released into culture supernatants was measured by an ELISA. *P <0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005, ****P <0.0001 (unpaired Student’s t-test); NS, not significant.

To test whether additional EsxGHMt expressed from Mtb could further inhibit antigen presentation, we examined a wild-type strain that contained esxGHMt on a plasmid20. Macrophages infected with the EsxGHMt-overexpressing Mtb strain elicited decreased activation of P25 CD4+ T cells compared with those infected with a strain containing the vector (Fig. 3f). In addition, when Mtb contained a plasmid bearing EsxGHMs, the M. smegmatis homologue of EsxGHMt, which does not inhibit ESCRT20, there was no effect on antigen presentation (Fig. 3f). The degree of inhibition was comparable if Mtb overexpressed EsxGHMt or if ESCRT was silenced in the BMDMs (Fig. 3g). Infecting ESCRT-depleted macrophages with the Mtb strain overexpressing EsxGHMt did not result in an additive defect in T-cell activation beyond that seen with either manipulation alone. This is consistent with the idea that EsxGHMt and siRNAs depleting HRS and TSG101 target a common pathway required for antigen presentation. In cells in which Tsg101 or Hrs were silenced, there was no statistically significant difference in T-cell activation between infection with the vector control strain and the overexpressing strain, although there was a trend towards a small decrease from the overexpressing strain. In macrophages infected by Mtb overexpressing EsxGHMt, Hrs silencing resulted in a small but statistically significant decrease in IFN-γ production relative to macrophages treated with control siRNA. These small decreases associated with the combination of the overexpressing strain and ESCRT silencing might be because RNAi-mediated silencing and EsxGHMt do not fully inhibit Hrs or because EsxGHMt has additional targets. Overall, we concluded that both overexpression and loss-of-function studies indicated that EsxGHMt impairs effector T-cell responses, similar to the situation seen with ESCRT silencing.

Antigen presentation is unaffected by PE5 and EsxA

In addition to containing esxG and esxH, the esx-3 locus encodes pe5 and ppe4, members of the proline-glutamic acid (PE) and proline–proline–glutamic acid (PPE) families, respectively. Tufariello et al.26 showed that PE5 is secreted by Esx-3, and, like the ΔesxH mutant, Δpe5-ppe4 requires exogenous siderophore-bound iron to grow on solid medium. In addition, the ΔesxH mutant fails to secrete PE5, raising the possibility that PE5 is responsible for the phenotype of the ΔesxH mutant. However, unlike ΔesxH, the Δpe5-ppe4 mutant did not result in increased T-cell responses (Fig. 3a,b). Thus, the influence of EsxH on antigen presentation is not explained by its role in iron acquisition or its effect on PE5 secretion. We also tested the role of EsxA, which is secreted by the Esx-1 type VII secretion system. Macrophages and DCs infected with the ΔesxA mutant did not showed increased ability to activate T cells (Fig. 3a,b), corroborating the idea that enhanced antigen presentation does not simply reflect bacterial attenuation.

EsxGHMt impairs priming of naive CD4+ T cells in vivo

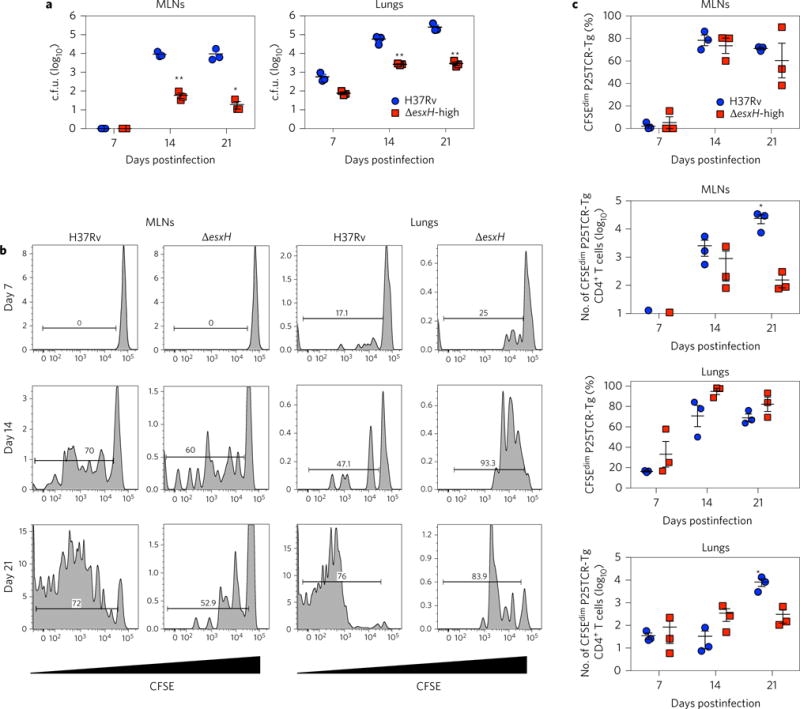

We hypothesized that EsxGHMt might contribute to impaired priming of CD4+ T cells in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we adoptively transferred carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labelled P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells into CD45.2 congenie mice and infected them by aerosol with H37Rv or the ΔesxH mutant and assessed the proliferation of P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells in the mediastinal lymph nodes (MLNs) and lungs. In initial experiments using an inoculum of 102–103 colony-forming units (c.f.u.), ΔesxH was cleared from the lungs and failed to disseminate to the draining lymph node. When we used high-dose ΔesxH (104 c.f.u.), the bacteria disseminated to the MLNs (Fig. 4a), although the number of c.f.u. in the lung was much lower than that found in mice infected with 102 c.f.u. H37Rv, and there were orders of magnitude fewer ΔesxH mutant in the MLNs than H37Rv at 14 d postinfection. Proliferation of the P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells in the MLNs was observed at this time point in response to both ΔesxH and H37Rv (Fig. 4b), and a similar percentage of P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells proliferated in the MLNs and lungs in response to both strains (Fig. 4c). That this degree of T-cell proliferation occurred in response to orders of magnitude fewer ΔesxH bacilli in the MLNs suggested that ΔesxH-infected cells might be superior to wild-type Mtb-infected cells in priming CD4+ T cells.

Figure 4. Fewer ΔesxH c.f.u. are required to initiate proliferation in the MLNs and lungs.

Mice with adoptively transferred CFSE-labelled P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells were infected by aerosol with H37Rv or high-dose ΔesxH. a, The number of c.f.u. in the MLNs and lungs was quantified at the indicated times (n = 3 mice per time point for each bacterial strain). Results reflect means ± s.e.m. b, Representative CFSE dilution profiles of adoptively transferred CFSE-labelled P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells in the MLNs and lung at different time points after aerosol infection. The y axis indicates the number of events. The horizontal bar indicates the percentage of proliferating cells. c, Quantitation of proliferating P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells in the MLNs and lungs after infection with H37Rv or ΔesxH, as determined by flow cytometry. Results reflect means ± s.e.m. Results are representative of two similar experiments. *P< 0.05, **P < 0.01 (unpaired Student’s t-test).

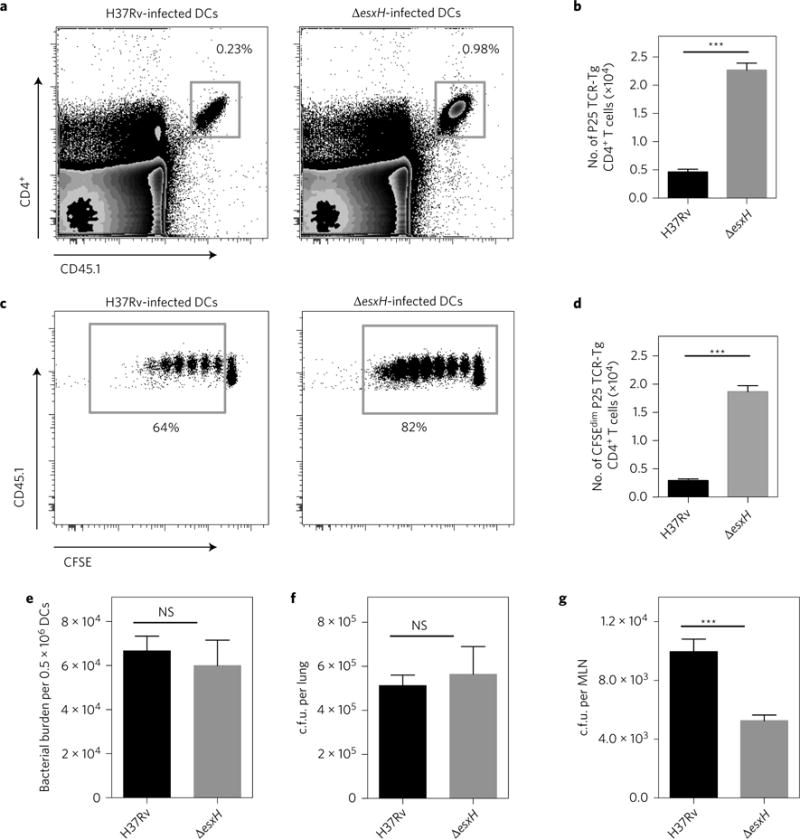

To compare P25TCRTg CD4+ T-cell responses with equal numbers of wild-type and ΔesxH mutant in vivo, we used intratracheal transfer of infected BMDCs. We adoptively transferred naive CFSE-labelled P25TCRTg CD4+ T cells in MHC-II knockout (MHC-II−/−) mice and compared their activation following intratracheal transfer of MHC-II-expressing (wild-type) BMDCs infected with equal numbers of H37Rv or ΔesxH. This experimental design allowed us to assay the contribution of antigen presentation from the infected DCs and eliminated the possibility that antigen transfer to uninfected bystander DCs was contributing to T-cell priming. Analysis of mediastinal MLNs revealed that, following transfer of DCs infected with ΔesxH, there was a threefold increase in the number of P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5a,b) and five- to six-fold more P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T-cell proliferation (Fig. 5c,d). This enhanced CD4+ T-cell priming was not due to a higher bacterial burden, as both groups of infected DCs contained similar numbers of bacteria, and equivalent numbers of DCs were transferred into recipient animals (Fig. 5e). There was also no difference in the number of bacteria in the lungs of the recipient mice (Fig. 5f). Interestingly, and consistent with the aerosol experiment above, the MLNs contained approximately half as many ΔesxH mutant as wild-type bacteria (Fig. 5g) but led to a fivefold increase in CD4+ T-cell proliferation. Thus, following transfer of infected DCs, there was more T-cell proliferation in response to fewer ΔesxH than wild-type bacilli. We concluded that EsxH impairs the ability of Mtb-infected DCs to prime CD4+ T cells in vivo.

Figure 5. EsxGHMt impairs priming of naive CD4+ T cells in vivo.

a, Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting plots showing the frequency of adoptively transferred P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells in the MLNs of MHC-II−/− mice 60 h after intratracheal transfer of MHC-II+/+ DCs infected with either H37Rv or ΔesxH. b, Quantitation of total P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells in the MLNs of the groups of mice shown in (a). c, Frequency of CFSE-labelled P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells undergoing proliferation in the MLNs of mice 60 h after intratracheal transfer of either H37Rv- or ΔesxH-infected MHC-II+/+ DCs. d, Quantitation of P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells that have undergone at least one cycle of proliferation (CFSEdim) in MLNs of groups of mice shown in a–c. e, Bacterial burden in H37Rv- or ΔesxH-infected BMDCs used for intratracheal transfer. Data are expressed as means ± s.e.m. of infected BMDCs in three replicates. f,g, Bacterial burden in lungs f or MLNs g of mice 60 h after receiving intratracheal BMDCs infected with either H37Rv or ΔesxH. All data are from one experiment expressed as mean ± s.e.m. of three pools of mice (n = 6) per experimental group. ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test); NS, not significant.

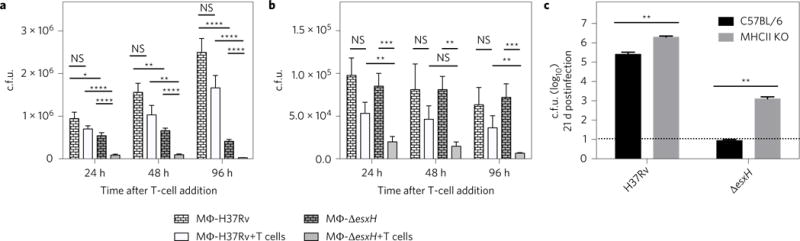

EsxH protects Mtb from CD4+ T-cell-mediated killing

Direct recognition of infected macrophages is important for CD4+ T cells to control Mtb36. To determine whether EsxH impairs the ability of effector CD4+ T cells to recognize infected macrophages, we cocultured BMDMs infected with either wild-type Mtb or the ΔesxH mutant with and without P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells and plated them to determine the number of c.f.u. We found that the addition of P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells to naive or IFN-γ-activated BMDMs had a modest effect on Mtb growth if macrophages were infected with wild-type Mtb (Fig. 6a,b). In contrast, addition of effector T cells to macrophages infected with the ΔesxH mutant resulted in substantial bacterial killing (Fig. 6a,b). We concluded that EsxH limits the ability of T cells to promote clearance of Mtb from infected macrophages. The enhanced sensitivity to T cells exhibited by the ΔesxH mutant may also explain why there were fewer ΔesxH than wild-type bacilli in the MLNs in the DC transfer experiments above (Fig. 5g), while in the lungs ΔesxH and wild type were no different (Fig. 5f). To test whether EsxH protected Mtb from T-cell-facilitated killing in vivo, we compared the bacterial burden of the ΔesxH mutant in the lungs of C57BL/6 and MHC-II−/− mice, which lack CD4+ T cells. Attenuation of the ΔesxH mutant was ameliorated in MHC-II−/− mice; in wild-type mice, there was more than a 4-log difference in c.f.u. between ΔesxH and wild type. In MHC-II−/−mice, there was a 3-log difference. Although the profound attenuation of the ΔesxH mutant is probably multifactorial, reflecting its role in metal homeostasis, phagosome maturation arrest and potentially other processes, the observation that there was a greater impact of T cells on the ΔesxH mutant than on H37Rv (Fig. 6c) is consistent with the idea that the in vivo attenuation of ΔesxH depends in part on MHC-II-mediated antigen presentation and CD4+ T-cell responses.

Figure 6. EsxH protects Mtb from CD4+ T-cell mediated killing.

a, BMDMs infected with H37Rv (wild type) or ΔesxH for 24 h were cultured for an additional 96 h in the absence or presence of P25TCR-Tg CD4+ cells as indicated, and the number of c.f.u. was determined. b, BMDMs treated with IFN-γ (activated BMDMs) the day before they were infected with H37Rv (wild type) or ΔesxH were incubated at 24 h postinfection with or without P25TCR-Tg CD4+ cells, and the number of c.f.u. was determined at the indicated time points. Data in a and b are expressed as means ± s.e.m. from two independent experiments with at least eight individual replicates per experimental group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 (Student’s t-test corrected for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method). c, C57BL/6 and MHC-II KO mice were infected with H37Rv or ΔesxH by aerosol (102 c.f.u. for both strains), and the number of c.f.u. was determined in the lungs at 21 d postinfection. Dashed horizontal line indicates the limit of detection. Data are from one experiment expressed as means ± s.e.m. (n = 5 per group). **P <0.01 (unpaired Student’s t-test). MΦ, macrophage; KO, knockout.

Discussion

We showed previously that to promote its intracellular survival Mtb secretes EsxH and inhibits the function of ESCRT. The role of ESCRT in antigen presentation has not previously been established. Here, we showed that ESCRT contributes to optimal antigen processing and that Mtb EsxH impairs the activation of CD4+ T cells and their ability to promote bacterial clearance. Macrophages and DCs infected with an Mtb mutant lacking EsxH yielded enhanced T-cell activation, whereas infection with a strain that overexpressed EsxGHMt elicited diminished T-cell responses. Overexpression of EsxGHMs, which does not bind HRS or inhibit ESCRT20, had no effect on T-cell responses. Thus, the ability of EsxGHMt to inhibit antigen presentation is probably due to a direct effect on HRS20, although additional targets may also play a role. Our findings are in accordance with those of Tufariello et al.26 who demonstrated an important role of esxH in virulence that is separable from the role in iron acquisition and that cannot be complemented by esxG–esxH from M. smegmatis.

This study is also, to the best of our knowledge, the first demonstration that ESCRT is required for antigen presentation. In DCs, degradation of peptide-loaded MHC-II is regulated by ubiquitination31,32, which has been presumed to be ESCRT dependent. Based on the presumption that ESCRT regulates MHC-II degradation, we expected that ESCRT silencing would result in enhanced MHC-II surface expression and potentially increased antigen presentation. Rather, we found that silencing ESCRT impaired T-cell activation by inhibiting antigen processing and presentation. There are several ways in which ESCRT might do this. First, the multivesicular architecture of the MHC-II compartment might be important for the processing and/or loading of antigen37–39. Alternatively, given the role of ESCRT in phagosome maturation20,29, ESCRT might promote antigen processing because it assists in trafficking Mtb to an acidic phagosomal environment that contains active lysosomal hydrolases. However, the literature does not suggest a simple relationship between phagosome maturation arrest, bacterial fitness and antigen presentation, as some attenuated strains are reported to enhance antigen presentation, whereas others have no effect10,11,40–42. Further complicating this explanation is the fact that lysosomal trafficking of Mtb in IFN-γ-activated macrophages does not depend on ESCRT (Supplementary Fig. 2). Nonetheless, there may be other aspects of the phagosomal environment that are altered by ESCRT inhibition, an explanation that we favour. For example, ESCRT might be required for trafficking the antigen processing or loading machinery to the phagolysosome or the MHC-II compartment.

Our findings extend well beyond the role of ESCRT in antigen presentation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of an Mtb effector and its corresponding cellular target impairing MHC-II antigen presentation by a mechanism other than Mtb Toll-like receptor 2 agonists blocking IFN-γ signalling. The previously described mechanism cannot explain how Mtb downregulates antigen presentation in antigen-presenting cells that already express MHC-II or in macrophages that are exposed to IFN-γ shortly after they are infected. Here, we have provided a molecular explanation for how, in migratory DCs and IFN-γ-activated macrophages, Mtb blunts T-cell responses. EsxGHMt may provide a double hit for Mtb by impairing efficient priming of antigen-specific T cells and preventing effector CD4+ T cells from recognizing infected macrophages, which is important for control of Mtb in vivo36. Importantly, this mechanism of immune evasion may also undermine the ability of pre-existing CD4+ T cells generated by a vaccine or prior infection to be protective. Our results demonstrated only a partial suppression of T-cell activation in response to ESCRT silencing or esxH expression by the bacilli. Thus, there are likely to be additional mechanisms that Mtb uses to impair antigen presentation.

The observation that EsxGHMt impairs antigen presentation would seem to be at odds with the findings that EsxGMt and EsxHMt, also known as TB9.8 and TB10.4, respectively, are prominent T-cell antigens43,44. This apparent conundrum may be explained by the fact that antigen transfer from infected to uninfected DCs allows priming of T cells in the lymph node18,19. When these T cells arrive in the lung, the EsxGHMt-imposed block in antigen presentation in infected macrophages would subvert effector responses. This is an important consideration in vaccine candidates that include EsxH; macrophages infected with Mtb expressing abundant EsxH might be those that are imperceptible to CD4+ T cells. Interestingly, a recent study found that EsxA/ESAT-6, secreted by the Esx-1 type VII secretion system, interacts with β2-microglobulin and inhibits MHC class I β2-microglobulin surface expression45. Thus, two of the most dominant T-cell antigens, EsxA and EsxH, appear to undermine the activation of two major T-cell subsets, leading us to speculate that their prominence as T-cell antigens reflects a bacterial strategy to generate an ineffective host response.

In conclusion, we have shown that ESCRT stimulates antigen presentation and that Mtb EsxGHMt undermines this critical function in activated macrophages and DCs. Our data provide a molecular explanation for the failure of the adaptive immune response to kill Mtb. Recent work has shown that it is possible to identify small molecules that impair type VII secretion46. Esx-3 inhibitors could be particularly potent, as inhibiting this system would impair intrinsic bacterial processes involved in metal homeostasis, as well as promoting host clearance by restoring macrophage function and T-cell activation.

Methods

Mice

P25TCR-Tg30 mice were bred into a C57BL/6 (CD45.1) background. C7TCR-Tg47 mice have been described previously. C57BL/6 (CD45.2) and MHC-II−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The New York University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all work with animals.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Mtb H37Rv overexpressing EsxGHMt or ESXGHMS, Mtb H37Rv expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)20, ΔfbpB1, ΔesxA48, mc27846 (ΔesxH) and mc27848 (Δpe5-ppe4)26 have been described previously. Mtb was grown at 37 °C to log phase in BD Difco Middlebrook 7H9 (Fisher Scientific) medium with 0.05% Tween 80, BD BBL Middlebrook OADC Enrichment (Fisher Scientific) and 0.2% glycerol. The pJP130 complementing plasmid described below (ΔesxH-compl) and the GFP plasmids were selected with 25 μg ml−1 kanamycin (Sigma). Mycobactin was not used routinely to supplement the mutants during growth in broth culture. When plating for determination of c.f. u., the ΔesxH mutant was grown on 7H10 plates supplemented with 200 ng/ml mycobactin J (Allied Monitor).

Tissue culture

RAW264.7 cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2 mM L-glutamine. RAW264.7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, and were expanded and frozen. After thawing, they were used within the first several passages and not tested for mycoplasma contamination. Bone marrow was isolated from 6–8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice as described previously49 and cultured in BMMO medium (DMEM with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 20% L929 cell-conditioned medium). BMDMs were collected between 6 and 7 d, detached from plates by incubation in ice-cold PBS with 5 mM EDTA, and then washed and plated in BMMO medium with 10% L929 cell-conditioned medium. Penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) was added to the medium for passaging but omitted during infections. BMDCs were grown in RPMI 1640 with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1× β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco), 10 mM HEPES and 10 ng ml−1 recombinant murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Peprotech) for 7 d, followed by sorting of CD11c+ DCs using magnetic cell sorting (autoMACS; Miltenyi Biotec).

siRNA treatment

Hiperfect (Qiagen) was used to transfect siRNAs 2 or 3d before infection of RAW cells or BMDMs, respectively.

CD4+ T-cell isolation

P251,30 and C7TCR-Tg47 TH1 effector cells were generated in vitro as described previously. Briefly, CD4+ T cells were isolated magnetically from lymph node cell suspensions from P25TCR-Tg and C7TCR-Tg mice using microbeads (MACS) and an autoMACS (both from Miltenyi Biotec). The cells were co-cultured with irradiated C57BL/6 splenocytes in the presence of mouse interleukin (IL)-12p70, IL-2, anti-IL-4 neutralizing antibody, and peptide P25 or ESAT-6(1–20) for 3 d and frozen until used.

Antigen presentation assays

At 7d after collection, 1 × 105 BMDMs per well were plated in 96-well plates and transfected with siRNAs. Two days later, they were treated with 200 U ml−1 IFN-γ (Gibco). The following day, they were infected with a single-cell suspension of Mtb (multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 1–5) prepared as described previously20. After 4 h, extracellular bacteria were removed by washing three times with warm PBS. Infected macrophages were incubated at 37 °C for an additional 20 h, after which P25TCR TH1 or C7TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells were added (5 × 105 cells per well). At 24 h after co-culture of infected BMDMs with CD4+ T cells, culture supernatants were collected, filtered and assayed for IFN-γ by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA: BD Biosciences). Alternatively, the antigen presentation assay was performed as above but without knocking down ESCRT, or, instead of infection with live Mtb, BMDMs were incubated with 0.5 μM P25 peptide or 10 μg ml−1 recombinant Ag85B protein (BEI Resources). Antigen presentation assays were also done using BMDCs as antigen-presenting cells. In this case, cells were not treated with IFN-γ before infection.

DQ-OVA processing assay

BMDMs were treated with 50 μg ml−1 DQ-OVA (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at 37 °C and washed three times with ice-cold PBS, followed by incubation in fresh medium at 37 °C for 24 h, after which they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Nuclei were stained with 2.5 μg ml−1 Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes). Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse TiE/B automated fluorescent microscope with a Photometrics HQ@ Monochrome digital camera. Z-stack images were acquired at a magnification of ×60, and the mean fluorescence intensity (fluorescein isothiocyanate) was quantified using NIS-Elements DUO software.

Lysosomal trafficking assay

siRNA-transfected RAW cells or BMDMs were infected with GFP-expressing Mtb for 4 h as described above. One day before infection, macrophages were treated with IFN-γ (100 U ml−1) or left untreated. Cells were fixed with 1% PFA in PBS overnight at 24 h postinfection, permeabilized with 0.1% saponin in PBS and blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 1 h. Cells were then immunostained for LAMP1 (1:1000 dilution; Abcam) for at least 1 h at room temperature or at 4 °C overnight, followed by treatment with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse TiE/B automated fluorescent microscope described above and analysed using NIS-Elements DUO software as described previously20.

Intracellular bacterial growth assay

RAW cells or BMDMs were transfected with siRNA and infected as described above (m.o.i. of 5). IFN-γ (100 U ml−1) was added 1 d before infection. At 4 h or 2 d postinfection, the cells were lysed with 0.2% Triton X-100 and serial dilutions plated. The numbers of c.f.u. were calculated 15–21 d later. For co-culture experiments, BMDMs were infected with wild-type Mtb or ΔesxH mutant (m.o.i. of 3). At 24 h postinfection, P25TCR-Tg effector T cells were added or not, and 24 h later, cells were lysed, diluted and plated as described above at different time points.

Western blot analysis

BMDMs were transfected with siRNA for 72 h, after which cellular lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer with Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific) and analysed by western blotting. The antibodies used for western blot analysis were against actin (clone C4; Millipore), HRS (M79; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and TSG101 (Genetex).

Adoptive transfer and naive P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T-cell proliferation

CD4+ T cells (3 × 106) collected from the lymph nodes and spleens of female P25TCR-Tg mice (8–12 weeks old) were labelled with 10 μM CFSE for 7 min and adoptively transferred by retro-orbital injections into 8-week-old female recipient mice. After 24 h, recipient mice were infected with 2×102 c.f.u. H37Rv or 1×104 c.f.u. ΔesxH mutant by the aerosol route using an Inhalation Exposure Unit (Glas-Col), as described previously15. At 7, 14 and 21 d after infection, MLNs and lungs were obtained from recipient mice and cells were analysed for CFSE dilution by flow cytometry. The experiments were not randomized or blinded. The number of animals used was determined based on feasibility and prior experience with the assay.

Intratracheal transfer of infected BMDCs

BMDC from wild-type mice were infected overnight with H37Rv or ΔesxH (m.o.i. of 1), washed, treated with amikacin (200 pg ml−1 for 40 min) and administered intratracheally to MHC-II−/− mice (5×105 DCs per mouse) 1 d after adoptive transfer of CFSE-labelled naive P25TCR-Tg CD4 cells (4 × 106 cells per mouse). At 60 h after BMDC transfer, MLNs were collected and processed for determination of bacterial c.f.u. and flow cytometry, and the lungs were processed for determination of c.f.u.

Flow cytometry

BMDMs were fixed in 1% PFA and stained using Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse MHC-II (I-A/I-E, clone M5/114.15.2; Biolegend). Single-cell suspensions from infected lungs and MLNs were stained using the following fluorescently labelled antibodies: Alexa Fluor 700-conjugated anti-mouse CD45.1 antibody (clone A20), peridinin–chlorophyll-conjugated anti-mouse CD3e (clone 145-2C11) and Pacific Blue-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 antibody (clone RM4-5) (all from Biolegend). Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCalibur and LSR II (BD Biosciences) at the New York University Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core. FlowJo software was used for data analysis.

Plasmids

pJP130 was used to complement the ΔesxH mutant. It was constructed by inserting Rv0289 into pYUB1944, which contains esxG–esxH under control of the hsp60 promoter26. Rv0289 was amplified from Mtb genomic DNA by PCR using forward (5′-TAGAAGCTTCTCGCGCTACATGGATGC-3′) and reverse (5′-CCAATCGATTTACGAGGATTGGGTGG-3′) primers, digested with HindIII, and cloned into the HindIII site after Rv0288 in pYUB1944. The addition of Rv0289 to pYUB1944 resulted in enhanced secretion of EsxG and EsxH compared with the parental plasmid.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Triplicate samples of H37Rv and ΔesxH culture filtrate were prepared and analysed by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry using an Easy nLC-1000 on-line with a QExactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) as described26. The data was analysed with MaxQuant software with the Andromeda search engine for peptide identification. Label-free quantitation algorithms were used to determine normalized relative protein quantitation values50.

Statistical analysis

Biological and technical replicates were used for analyses. Data shown are representative of two or more independent experiments. In all figures, error bars indicate means ± s.e.m. An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to determine statistical significance between experimental groups unless otherwise indicated.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors (W.R.J. and J.A.P.) on request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the New York University Cytometry Core at the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center (partially supported by a Cancer Center Support Grant, P30CA016087) for their assistance with flow cytometry, Beatrix Ueberheide and Jessica Chapman-Lim for assistance with proteomics (New York University Proteomics Resource Center), Michael Glickman (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) for the C7TCR Tg mice, BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH for Ag85B protein (Ag85B Recombinant Protein Reference Standard, NR-14870), and members of the Philips and Ernst laboratories, in particular Colette O’Shaughnessy and Ludovic Desvignes, for assistance and helpful discussions. This workwas supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01s AI087682, AI026170, and AI098925, K08 AI119150-01 and UL1 TR000038.

Footnotes

Author contributions

C.P.-C., and J.A.P. conceived and designed the study. C.P.-C. performed all the in vitro experiments with help from T.K., with the exception of the trafficking studies done by A.Z. C.P.-C. and S.S. designed and performed in vivo experiments. A.M. and H.S.P. created plasmids. J.M.T. and W.R.J. contributed the ΔesxH and Δpe5-ppe4 strains. C.P.-C. and P.S. G performed flow cytometry. C.P.-C. and J.A.P. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. J.D.E., W.R.J. and J.A.P. oversaw the project.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper. Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Wolf AJ, et al. Initiation of the adaptive immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis depends on antigen production in the local lymph node, not the lungs. J Exp Med. 2008;205:105–115. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacMicking JD. Interferon-inducible effector mechanisms in cell-autonomous immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:367–382. doi: 10.1038/nri3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortune SM, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibits macrophage responses to IFN-γ through myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2004;172:6272–6280. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noss EH, et al. Toll-like receptor 2-dependent inhibition of macrophage class II MHC expression and antigen processing by 19-kDa lipoprotein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2001;167:910–918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pennini ME, Pai RK, Schultz DC, Boom WH, Harding CV. Mycobacterium tuberculosis 19-kDa lipoprotein inhibits IFN-γ-induced chromatin remodeling of MHC2TA by TLR2 and MAPK signaling. J Immunol. 2006;176:4323–4330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kincaid EZ, et al. Codominance of TLR2-dependent and TLR2-independent modulation of MHC class II in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:3187–3195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. On regulation of phagosome maturation and antigen presentation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1029–1035. doi: 10.1038/ni1006-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramachandra L, Noss E, Boom WH, Harding CV. Processing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen 85B involves intraphagosomal formation of peptide-major histocompatibility complex II complexes and is inhibited by live bacilli that decrease phagosome maturation. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1421–1432. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagannath C, et al. Autophagy enhances the efficacy of BCG vaccine by increasing peptide presentation in mouse dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:267–276. doi: 10.1038/nm.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansen P, et al. Relieffrom Zmp1-mediated arrest of phagosome maturation is associated with facilitated presentation and enhanced immunogenicity of mycobacterial antigens. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:907–913. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00015-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majlessi L, et al. Inhibition of phagosome maturation by mycobacteria does not interfere with presentation of mycobacterial antigens by MHC molecules. J Immunol. 2007;179:1825–1833. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanekom WA, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibits maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells in vitro. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:257–266. doi: 10.1086/376451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson RA, Watkins SC, Flynn JL. Activation of human dendritic cells following infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1997;159:635–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giacomini E, et al. Infection of human macrophages and dendritic cells with Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces a differential cytokine gene expression that modulates T cell response. J Immunol. 2001;166:7033–7041. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf AJ, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infects dendritic cells with high frequency and impairs their function in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:2509–2519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grace PS, Ernst JD. Suboptimal antigen presentation contributes to virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. J Immunol. 2016;196:357–364. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samstein M, et al. Essential yet limited role for CCR2+ inflammatory monocytes during Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T cell priming. eLife. 2013;2:e01086. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srivastava S, Ernst JD. Cell-to-cell transfer of M. tuberculosis antigens optimizes CD4T cell priming. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:741–752. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srivastava S, Grace PS, Ernst JD. Antigen export reduces antigen presentation and limits T cell control of M. tuberculosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehra A, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis type VII secreted effector EsxH targets host ESCRT to impair trafficking. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003734. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serafini A, Pisu D, Palù G, Rodriguez GM, Manganelli R. The ESX-3 secretion system is necessary for iron and zinc homeostasis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serafini A, Boldrin F, Palù G, Manganelli R. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESX-3 conditional mutant: essentiality and rescue by iron and zinc. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6340–6344. doi: 10.1128/JB.00756-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegrist MS, et al. Mycobacterial Esx-3 requires multiple components for iron acquisition. mBio. 2014;5:e01073–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01073-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegrist MS, et al. Mycobacterial Esx-3 is required for mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18792–18797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900589106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tinaztepe E, et al. Role of metal-dependent regulation of ESX-3 secretion in intracellular survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2016;84:2255–2263. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00197-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tufariello JM, et al. Separable roles for Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESX-3 effectors in iron acquisition and virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E348–E357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523321113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sweeney KA, et al. A recombinant Mycobacterium smegmatis induces potent bactericidal immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:1261–1268. doi: 10.1038/nm.2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raiborg C, Stenmark H. The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature. 2009;458:445–452. doi: 10.1038/nature07961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philips JA, Porto MC, Wang H, Rubin EJ, Perrimon N. ESCRT factors restrict mycobacterial growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3070–3075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707206105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamura T, et al. The role of antigenic peptide in CD4+ T helper phenotype development in a T cell receptor transgenic model. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1691–1699. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baravalle G, et al. Ubiquitination of CD86 is a key mechanism in regulating antigen presentation by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:2966–2973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohmura-Hoshino M, et al. Cutting edge: requirement of MARCH-I-mediated MHC II ubiquitination for the maintenance of conventional dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:6893–6897. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Via LE, et al. Arrest of mycobacterial phagosome maturation is caused by a block in vesicle fusion between stages controlled by rab5 and rab7. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13326–13331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gutierrez MG, et al. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 2004;119:753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakowski ET, et al. Ubiquilin 1 promotes IFN-γ-induced xenophagy of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathogens. 2015;11:e1005076. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srivastava S, Ernst JD. Cutting edge: direct recognition of infected cells by CD4T cells is required for control of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. J Immunol. 2013;191:1016–1020. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ten Broeke T, Wubbolts R, Stoorvogel W. MHC class II antigen presentation by dendritic cells regulated through endosomal sorting. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a016873. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zwart W, et al. Spatial separation of HLA-DM/HLA-DR interactions within MIIC and phagosome-induced immune escape. Immunity. 2005;22:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bosch B, et al. Disruption of multivesicular body vesicles does not affect major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-peptide complex formation and antigen presentation by dendritic cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:24286–24292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.461996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh CR, et al. Processing and presentation of a mycobacterial antigen 85B epitope by murine macrophages is dependent on the phagosomal acquisition of vacuolar proton ATPase and in situ activation of cathepsin D. J Immunol. 2006;177:3250–3259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hinchey J, et al. Enhanced priming of adaptive immunity by a proapoptotic mutant of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2279–2288. doi: 10.1172/JCI31947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saikolappan S, et al. The fbpA/sapM double knock out strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is highly attenuated and immunogenic in macrophages. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hervas-Stubbs S, et al. High frequency of CD4+ T cells specific for the TB10.4 protein correlates with protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3396–3407. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02086-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skjot RL, et al. Epitope mapping of the immunodominant antigen TB10.4 and the two homologous proteins TB10.3 and TB12.9, which constitute a subfamily of the esat-6 gene family. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5446–5453. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5446-5453.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sreejit G, et al. The ESAT-6 protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis interacts with beta-2-microglobulin (β2M) affecting antigen presentation function of macrophage. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004446. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rybniker J, et al. Anticytolytic screen identifies inhibitors of mycobacterial virulence protein secretion. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:538–548. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallegos AM, Pamer EG, Glickman MS. Delayed protection by ESAT-6-specific effector CD4+ T cells after airborne M. tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2359–2368. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong KW, Jacobs WR., Jr Critical role for NLRP3 in necrotic death triggered by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:1371–1384. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Banaiee N, Kincaid EZ, Buchwald U, Jacobs WR, Jr, Ernst JD. Potent inhibition of macrophage responses to IFN-γ by live virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis is independent of mature mycobacterial lipoproteins but dependent on TLR2. J Immunol. 2006;176:3019–3027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luber CA, et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals subset-specific viral recognition in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2010;32:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors (W.R.J. and J.A.P.) on request.