Abstract

Life expectancy in Mexico increased for more than six decades but then stagnated in the period 2000–10. This decade was characterized by the enactment of a major health care reform—the implementation of the Seguro Popular de Salud (Popular Health Insurance), which was intended to provide coverage to the entire Mexican population—and by an unexpected increase in homicide mortality. We assessed the impact on life expectancy of conditions amenable to medical service—those sensitive to public health policies and changes in behaviors, homicide, and diabetes—by analyzing mortality trends at the state level. We found that life expectancy among males deteriorated from 2005 to 2010, compared to increases from 2000 to 2005. Females in most states experienced small gains in life expectancy between 2000 and 2010. The unprecedented rise in homicides after 2005 led to a reversal in life expectancy increases among males and a slowdown among females in most states in the first decade of the twenty-first century.

The second half of the twentieth century was marked by major improvements in health, living standards, and mortality in most Latin American countries.1 But these improvements have been reversed in recent years, as Latin American countries have experienced a marked increase in homicide rates in the 2000s.2 After six decades of sustained improvement in life expectancy, Mexico experienced stagnation in this indicator between 2000 and 2010 as a result of an unexpected increase in homicides (particularly of people ages 15–50) and an anticipated increase in deaths due to diabetes3 (among people ages forty and older). However, these changes were accompanied by reductions in mortality from causes of death at young ages (for example, perinatal conditions).4,5

The increase in homicides is at the heart of life expectancy stagnation for males in Mexico between 2000 and 2010. Homicide rates increased from 9.5 homicides per 100,000 people in 2005 to more than 22.0 per 100,000 people in 2010.6 As a result, there was a reduction of about 0.6 year in male life expectancy in the period 2000–10.5

Importantly, the stagnation in life expectancy occurred during a time of substantial changes in national public policies to improve the health status of the Mexican population. Mexico implemented an ambitious and comprehensive health care reform in 2004, called the Seguro Popular de Salud (Popular Health Insurance). The program’s goal is to provide universal coverage to the uninsured population.7 Empirical evidence suggests that the Seguro Popular has led to improvements in the equitable distribution of health resources, with increased coverage for the uninsured.8 These improvements were accompanied by reductions in catastrophic and out-of-pocket expenditures9 and increases in financial protection for the beneficiaries in the medium term.10 However, it is still too soon to know what impact the Seguro Popular has had on health outcomes.

Although informative, national trends in life expectancy conceal heterogeneity at the subnational level. National life expectancy in Mexico is made up of state-specific mortality rates. Thus, national life expectancy could be stagnant because of an increase in homicides in some states that was offset by reduced mortality for diseases amenable to medical service (such as infectious and respiratory conditions) in other states.

For instance, mortality rates from diseases amenable to medical service may improve in the poorest states of the country (for example, Oaxaca and other southern states) where, by law, the government made especially significant efforts to enroll the uninsured in the Seguro Popular.11 But independent of health gains that may be occurring in other states, homicide mortality increased in northern states (Chihuahua and Baja California, which border on the United States) and states on the Pacific coast (Sinaloa, Michoacán, and Guerrero), and homicides have slowly spread throughout the country.12

Given the increase in homicides in some states and the large variation in how the Seguro Popular was implemented at the state level, understanding state-specific trajectories in life expectancy is an important step toward explaining its stagnation at the national level.

Study Data And Methods

We used data on deaths from vital statistics files available through the Mexican National Institute of Statistics and Geography to compute the proportion of deaths by cause, age, sex, and state in a given year.13 These data include information on cause of death by age at the time of death, sex, and place of occurrence. Additionally, we used population and death estimates corrected for completeness, age misstatement, and international migration available from the Mexican Society of Demography to construct age-specific death rates by sex and state.4

Cause-Of-Death Classification

To identify causes of death that could be affected by the implementation of the Seguro Popular, we used the concept of amenable or avoidable mortality.14,15 This concept assumes that there are some conditions that should not cause death if effective and pertinent medical care is provided. Deaths due to these conditions are a proxy for the performance of health care systems.15

We used a recent cause-of-death classification system based on previous studies.16,17 We grouped causes of death into eight categories (for details on the International Classification of Diseases [ICD] codes for each cause, see online Appendix Table 1).18

The eight categories are as follows: causes amenable to medical service (deaths that could be reduced by timely medical care or primary or secondary prevention), causes sensitive to public health policies and changes in health behaviors (for example, drunk driving, smoking, and failure to use a seatbelt), homicide, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, HIV/AIDS, suicide and self-inflicted injuries, and all other causes (a category labeled residual causes). We analyzed homicide, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and HIV/AIDS separately from other conditions because homicide and diabetes represent major causes of death in Mexico,5 and all of these conditions are amenable to both health behavior change and medical service.16

We focused on cause-specific mortality below age seventy-five for three reasons. First, we calculated that about 93 percent of the change in life expectancy at birth between 2000 and 2010 was due to mortality changes below that age. Second, cause-of-death classification is less reliable at older ages.19 And third, health care and policy or behavior interventions tend to be more effective at younger ages.16

We studied changes in life expectancy during the decade by looking at two time periods, 2000–05 and 2005–10. This allowed us to identify changes in life expectancy between the periods before and after the 2004 implementation of the Seguro Popular and during the years when the rise in homicides was documented. Significant increases in coverage under the Seguro Popular occurred in the years after its implementation, so it is likely to have had an impact on population health through 2010.11

Methods

We first calculated age- and sex-specific death rates in five-year age groups up to age 100 for the thirty-two Mexican states (including the Distrito Federal). We estimated period life tables—which summarize mortality experience and indicate life expectancy for people in a specific time period—for 2000, 2005, and 2010 using standard demographic procedures.20 Then we calculated cause-of-death contributions below age seventy-five to differences in life expectancy at birth between 2000 and 2005, and between 2005 and 2010, by sex and state using a standard cause-decomposition approach.21 In addition, we carried out a sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of migration between states. Our analysis showed that emigration from one state to another associated with violence between 2005 and 2010 was unlikely to play a major role in our estimates because it accounted for less than 1.5 percent of any state’s population (see Appendix Table 2).18

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, there are likely to be inaccuracies in cause-of-death mortality figures because of coding practices.19 To reduce these inaccuracies, we focused on deaths before age seventy-five and used broad cause-of-death categories from the most recent ICD classification (ICD-10).

Second, we used the concept of avoidable mortality as a proxy to capture the effect of the Seguro Popular on a set of causes of death. This concept should be interpreted as an indicator of potential weaknesses in health care and not as definitive evidence of differences in the effectiveness of health care over time and between the states.14

Third, reductions in mortality from 2005 to 2010 were partly due to previously established public programs (such as labor-based social security) and private health institutions and partly due to changes in health risk factors (for example, smoking status and diet).22 However, the substantive increase in health care coverage through the Seguro Popular8 also probably played a major role in this period.

Fourth, our estimated effects of homicide mortality on life expectancy are likely to be a lower bound instead of the actual impact of homicide on the average length of life because of the underestimation of homicide deaths resulting from undercounting, underreporting, and the large number of missing individuals.23,24

Despite these limitations, we used the most reliable data for Mexico to gauge the contributions of age and cause of death to changes in life expectancy across states and over time.

Study Results

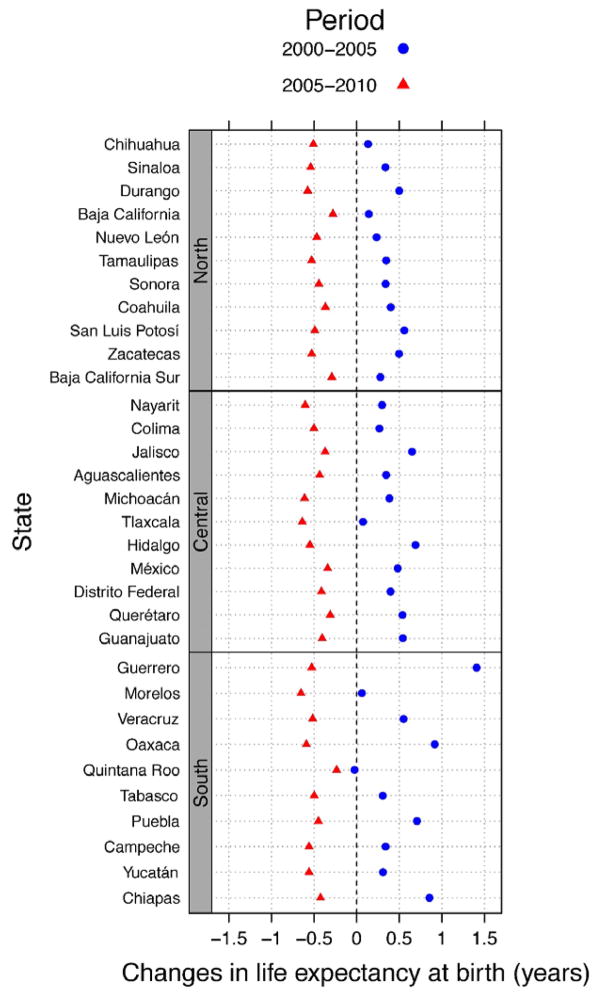

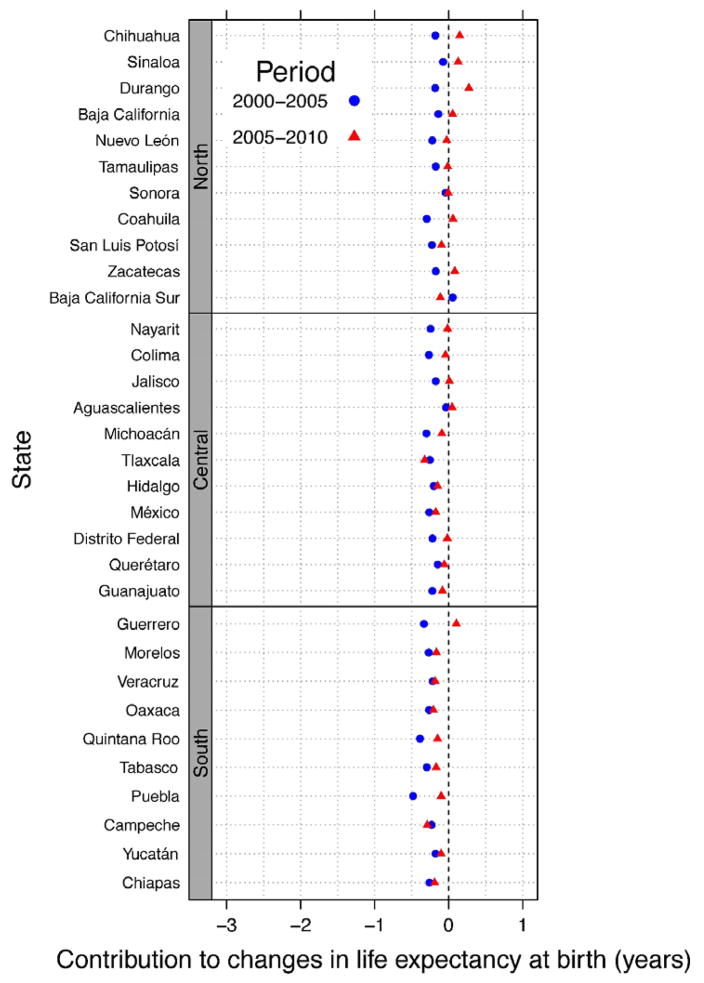

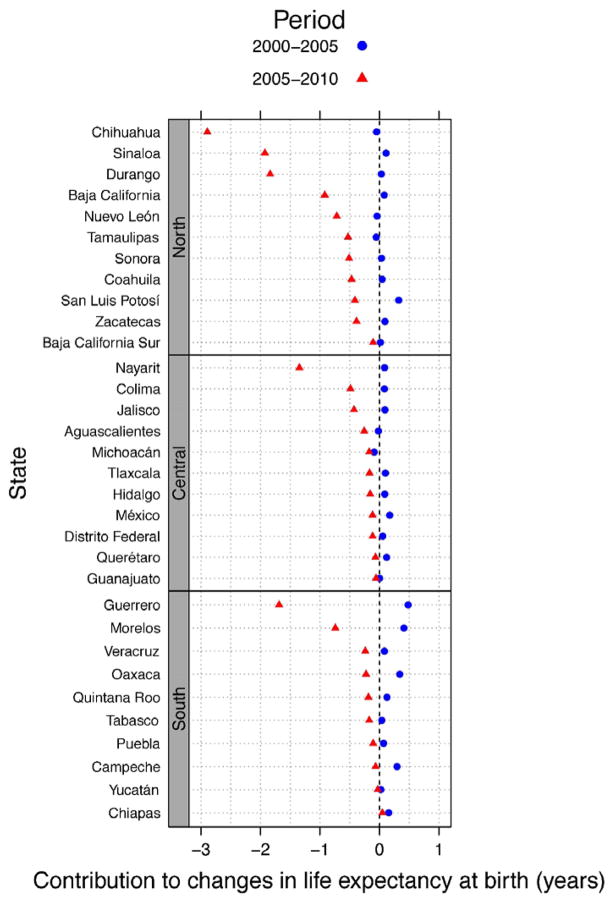

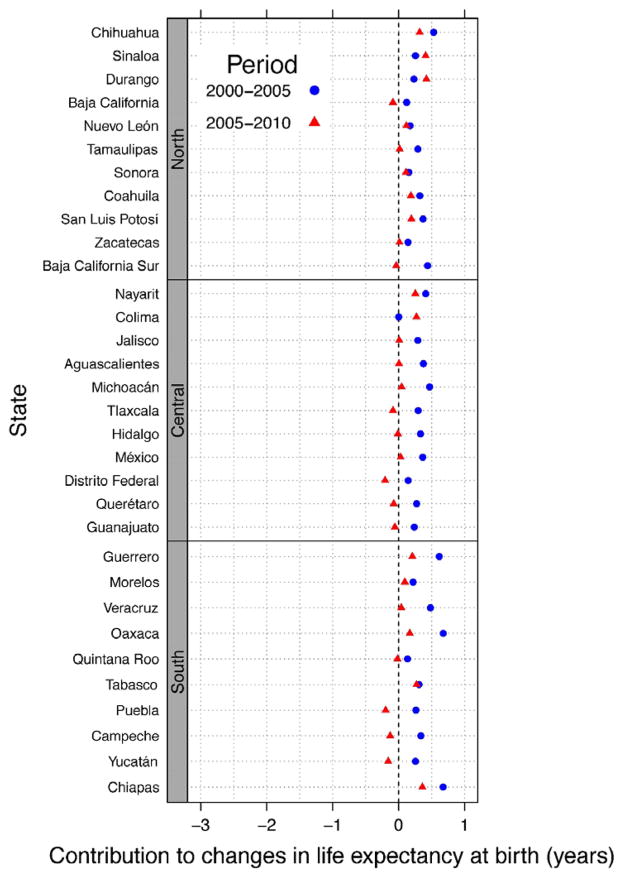

In Figures 1–4, the Mexican states in each region are arranged according to the negative impact of homicide mortality on life expectancy in 2005–10.

Figure 1.

Changes In Male Life Expectancy At Birth In Mexico, By State And Period, From 2000 To 2005 And From 2005 To 2010

Source: Authors ’ calculations based on data from the Mexican Society of Demography (see Note 4 in text) and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (see Note 13 in text).

Notes: Within each region, the states are ordered according to the negative impact of homicide mortality on life expectancyin 2005 –10 (as shown in Figure 2). For example, in the north, Chihuahua experienced the highest loss in life expectancy due to homicide and Baja California Sur the lowest. Negative numbers indicate a decrease in life expectancy during the period.

Figure 4.

Changes In Male Life Expectancy At Birth In Mexico Related To Diabetes Mortality, By State And Period, From 2000 To 2005 And From 2005 To 2010

Source: Authors ’ calculations based on data from the Mexican Society of Demography (see Note 4 in text) and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (see Note 13 in text).

Notes: The states are ordered according to the contribution of homicide mortality to life expectancy within region. Negative changes indicate that cause-specific mortality increased during the period, leading to a reduction in life expectancy. Conversely, positive changes indicate a decline in cause-specific mortality and an increase in life expectancy.

All states except one (Quintana Roo) experienced increases in male life expectancy at birth from 2000 to 2005 (Figure 1). In contrast, male life expectancy declined in all states from 2005 to 2010. The magnitude of the decline in the latter period offset most gains in life expectancy in the former period. In fact, about two-thirds of the states ended up with lower life expectancy in 2010 than they had had ten years earlier.

Female life expectancy showed a different pattern over the decade, with some states experiencing a continuous increase in life expectancy and others showing a continuous decrease (see Appendix Figure S1).18 In contrast to the results for males, females in most states had experienced small gains in life expectancy by decade’s end.

Figures 2–4 show how homicide, causes amenable to medical service, and diabetes, respectively, contributed to changes in male life expectancy at birth for the two periods. These are the causes of death that contributed the most to changes in life expectancy in both periods (for all causes of death, see Appendix Figure S2).18 Cause-specific mortality for homicide (Figure 2) and causes amenable to medical service (Figure 3) declined from 2000 to 2005 in most states, leading to increases in life expectancy at birth over the period. However, there was a clear reversal in those increases from 2005 to 2010, particularly in the case of homicide. In fact, changes in mortality due to homicide caused the largest decline in life expectancy over the decade. The decline was most severe in the north, with males in Chihuahua, Sinaloa, and Durango experiencing a reduction in life expectancy of about two to three years from 2005 to 2010.

Figure 2.

Changes In Male Life Expectancy At Birth In Mexico Related To Homicide Mortality, By State And Period, From 2000 To 2005 And From 2005 To 2010

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Mexican Society of Demography (see Note 4 in text) and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (see Note 13 in text).

Notes: The states are ordered according to the contribution of homicide mortality to life expectancy within region. Negative changes indicate that cause-specific mortality increased during the period, leading to a reduction in life expectancy. Conversely, positive changes indicate a decline in cause-specific mortality and an increase in life expectancy.

Figure 3.

Changes In Male Life Expectancy At Birth In Mexico Related To Mortality Resulting From Causes Amenable To Medical Service, By State And Period, From 2000 To 2005 And From 2005 To 2010

Source: Authors ’ calculations based on data from the Mexican Society of Demography (see Note 4 in text) and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (see Note 13 in text).

Notes: The states are ordered according to the contribution of homicide mortality to life expectancy within region. Negative changes indicate that cause-specific mortality increased during the period, leading to a reduction in life expectancy. Conversely, positive changes indicate a decline in cause-specific mortality and an increase in life expectancy.

Changes in mortality due to causes amenable to medical service contributed to increasing life expectancy for most states in both periods, although one-third of states experienced declines in life expectancy from 2005 to 2010 (Figure 3). Similarly, changes in mortality due to causes sensitive to public health policies and changes in health behaviors (for example, lung cancer, road accidents, and cirrhosis) also contributed to rising life expectancy in most states during the decade (see Appendix Figure S2).18

Although diabetes mortality increased in most states during the decade, that change had a smaller impact on changes in life expectancy from 2005 to 2010 than it did on those changes from 2000 to 2005 (Figure 4). In northern and central states, changes in diabetes mortality had a negligible effect on life expectancy from 2005 to 2010 because of a leveling off in diabetes mortality rates during the period. In some states (such as Chihuahua, Sinaloa, and Durango), diabetes mortality even declined from 2005 to 2010, leading to small increases in life expectancy. Changes in diabetes mortality had a slightly greater negative effect on life expectancy in the south than in the other two regions of the country. However, changes in mortality from diabetes led to an increase in life expectancy in one southern state (Guerrero).

In contrast, in most states there were declines in females’ rates of mortality due to causes amenable to medical service and those sensitive to public health policies and changes in health behaviors (see Appendix Figure S3).18 Homicide mortality rates for females as well as males increased after 2005, but the change had a smaller impact on females’ life expectancy than on that of males. Similar to males, females residing in northern states had the largest increase in homicide mortality from 2005 to 2010, with losses of life expectancy of about half a year in Chihuahua and about one-quarter year in Durango and Sinaloa.

Among females, changes in diabetes mortality resulted in sizable reductions in life expectancy from 2000 to 2005 in most states. However, almost all states in the northern and central regions, and some states in the south, experienced gains in life expectancy for females from 2005 to 2010 as a result of declines in diabetes mortality. Even in southern states, where diabetes mortality continued to have a negative impact on life expectancy, the effect was lower in the second half of the decade than in the first half.

Contributions to changes in life expectancy by mortality due to ischemic heart disease, HIV/AIDS, and suicide were negligible for both males and females (see Appendix Figures S2 and S3).18

Discussion

Life Expectancy Trends In Mexico from 2000 to 2010, life expectancy at birth deteriorated relative to the trend observed in the previous six decades, during which the country experienced an average increase of about four years of life expectancy per decade.25 From 2000 to 2010, women experienced a continuous increase in life expectancy, although with very small increments, but life expectancy for men was stagnant.5 Our research sheds some light on this national trend by showing that it is the result of offsetting state-specific mortality trends, with life expectancy increasing in most states from 2000 to 2005 but decreasing in every state from 2005 to 2010.

Effect Of Homicide And Diabetes On Life Expectancy At Birth

Our findings indicate that the downward trend in the second half of the decade resulted from large increases in homicide mortality in all states, which affected both males and females. As a result, there were large reductions in life expectancy among males in all states and a slowdown in life expectancy gains among females. On average, men experienced homicide rates ten times higher than those of women.26 The increase in male mortality from homicide was such that the initial gain in life expectancy from 2000 to 2005 was lost by the end of the decade.

There were also increases in male mortality from diabetes over the decade that led to reductions in average life expectancy. In contrast, females in most states experienced a reduction in diabetes mortality that led to increasing life expectancy from 2005 to 2010.

Our results clearly indicate that homicides were the main reason for the observed decline in life expectancy from 2005 to 2010 among men nationwide. The intensity and severity of the increase in homicide mortality rates were such that the gains in population health from improvements in other mortality rates—both from 2000 to 2005 and from 2005 to 2010—were largely wiped out. This led to the stagnation of life expectancy at the national level from 2000 to 2010 for men at about seventy-two years, as previously shown.5 These findings are consistent with previous research.10

Importantly, our results for the period from 2005 to 2010 indicate that the largest loss of life due to homicide among males was concentrated in five states (Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Durango, Guerrero, and Nayarit), with over one year of life expectancy lost in each. For example, males in Chihuahua (the northern Mexican state bordering New Mexico and Texas in the United States) experienced a loss of life expectancy of about three years from 2005 to 2010, and in 2010 they had a homicide rate of over twenty deaths per thousand males younger than seventy-five (authors’ calculations). To put these figures into perspective, it took thirteen years (from 1991 to 2003) for Chihuahua to raise male life expectancy by three years (from 69.3 years to 72.4 years),4 but this increase was completely reversed in a five-year period (from 2005 to 2010).

We further estimated cause-age-specific decompositions to determine the ages that contributed the most to this decline in life expectancy (see Appendix Table 3).18 Two-thirds of the decline was due to mortality increases among males ages 20–39 (37.15 percent for those ages 20–29 and 31.52 percent for those ages 30–39). The mortality rate for males ages 20–39 in Chihuahua in the period 2005–10 reached unprecedented levels: It was about 3.1 times higher than the mortality rate of US troops in Iraq between March 2003 and November 2006.27,28

Although homicide mortality has typically been associated with Mexican states linked to drug cartel operations (such as Sinaloa and Michoacán), our results also highlight increasing rates of male homicide in states with historically low levels of homicide mortality (such as Nayarit in the central region and Guerrero in the south) (Figure 2). These results are consistent with previous research showing that homicide mortality increased in tandem with military operations against drug cartels in states linked to their operations but also that the increase has slowly spread to the entire country.12

We also found that diabetes continues to be an important cause of death in Mexico but that diabetes mortality had a lower toll on life expectancy in 2005–10 than it did in 2000–05. Among males, changes in diabetes mortality led to reductions in life expectancy in most states from 2000 to 2005 but had negligible effects on life expectancy from 2005 to 2010. Results for females were more remarkable, with all but two states in the northern and central regions experiencing improvements in diabetes mortality, which led to increasing life expectancy from 2005 to 2010.

The smaller effect of diabetes mortality on life expectancy in 2005–10 may have resulted from increasing access to health care through the Seguro Popular. That view is supported by evidence indicating that an increase in health care cover age through the Seguro Popular8 particularly improved access to diabetes treatment and control among the poor.29

The increase in homicide mortality in Mexico after 2005 suggests a rapid deterioration in life expectancy. However, other countries in Latin America have experienced an even faster increase in homicide mortality.2 Mexico’s national homicide rate in 2012 (21.5 homicides per 100,000 people) was still below that of other Latin American countries such as Brazil (25.2), Colombia (30.8), Belize (44.7), El Salvador (41.2), and Honduras (90.4).2 Given the great number of years of life lost associated with homicide mortality in Mexico, it is likely that other Latin American countries have been experiencing even greater reductions in life expectancy from homicide. Our results from Mexico highlight the need to assess the impact of homicide mortality on population health and life expectancy in other Latin American countries, as well as in those countries’ regions and states.

Addressing Violence And Improving Population Health

Our results show that violence, through homicide, has had devastating consequences for the Mexican population. The Mexican government has attempted to mitigate the rise in violence through national-level judicial, police, and penal reforms.30 However, the strategies implemented by the government have produced mixed (and sometimes unfavorable) results.12,31

For instance, Mexico’s homicide rate started to rise in 2006, which coincided with the implementation of a major national security strategy aimed at reducing drug cartels’ operations and violence in the country.12 Contrary to what was expected, this policy has been associated with an unprecedented increase in violence and homicides in the country,12,31 consistent with our findings. Even though the most recent data show a decline in homicide rates in 2012 and 2013— to 22.2 and 19.5 deaths per 100,000 people, respectively—homicide rates in 2013 were still more than twice as high as they were in 2005.13 There is a need for increased attention to public health interventions that could be implemented to change the factors that contribute to violence in Mexico (such as factors related to social, economic, and cultural conditions). Our results suggest that approaches such as epidemiological surveillance can be used to strengthen policies to reduce violence. Evidence from other countries such as Colombia suggests that it is possible to reduce homicide mortality rates by implementing community programs to prevent violence that focus on lessening risk factors (for example, alcohol use and firearm possession).32,33

Conclusion

Most people in Mexico have access to health services through the Seguro Popular and other public health programs and institutions. However, our results reveal that there are still large health disparities among states. Even more worrisome is the detrimental effect of homicide mortality on population health, since the public health improvements achieved in the period 2000–10 were reversed by the unprecedented rise in homicides after 2005. The impact of the increasing violence in the country extends beyond the loss of human life because of the important social and economic consequences for those left behind. As long as the rate of homicide continues to be high and violence remains prevalent in Mexico, it is likely that the health of the population will continue to deteriorate.

There is no simple way to curtail the increase in homicide mortality, but it is clear that the policies implemented in the past decade have not controlled the high levels of violence in Mexico. These policies should be discontinued, and new strategies incorporating a public health perspective should be implemented to minimize the effects of violence on the health status of the Mexican population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sergio Aguayo for his comments on an earlier version of the article. José Manuel Aburto was supported by funding from the National Council of Science and Technology. He and Victor García-Guerrero were supported by funding from the Center of Demographic, Urban and Environmental Studies at El Colegio de México. Hiram Beltrán-Sánchez was supported by the California Center for Population Research at the University of California, Los Angeles (Grant No. R24-HB041022), and the Center for Demography of Health and Aging at the University of Wisconsin Madison (Core Grant Nos. R24HD047873 and P30AG017266). Vladimir Canudas-Romo was supported by the European Research Council (Grant No. 240795). The funding sources had no influence on the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or the writing of the article and the decision to submit the article. Beltrán-Sánchez and Aburto were responsible for the conception and design of the study and for the analysis and interpretation of the data, and they wrote the first draft of the article. García-Guerrero and Canudas-Romo participated in the revision of the draft and approved the final version.

Notes

- 1.World Health Organization. The world health report 2000—health systems: improving performance [Internet] Geneva: WHO; 2000. [cited 2015 Nov 3]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Global study on homicide 2011 [Internet] Vienna: UNODC; 2011. [cited 2015 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/congress/background-information/Crime_Statistics/Global_Study_on_Homicide_2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barquera S, Tovar-Guzmán V, Campos-Nonato I, González-Villalpando C, Rivera-Dommarco J. 2003 Geography of diabetes mellitus mortality in Mexico: an epidemiologic transition analysis. Arch Med Res. 2003;34(5):407–14. doi: 10.1016/S0188-4409(03)00075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mexican Society of Demography. [Demographic reconciliation of Mexico and its states 1990–2010] Mexico City: SOMEDE-CONAPO; 2011. Conciliación demográfica de México y entidades federativas 1990–2010. Unpublished paper. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canudas-Romo V, García-Guerrero VM, Echarri-Cánovas CJ. The stagnation of the Mexican male life expectancy in the first decade of the 21st century: the impact of homicides and diabetes mellitus. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(1):28–34. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Echarri CC. Homicidio. In: Echarri CC, editor. Panorama estadístico de la violencia en México. Mexico City: Secretaría de Seguridad Pública; 2012. pp. 51–103. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frenk J. Sistema de protección social en salud, elementos conceptuales, financieros, y operativos. Mexico City: Secretaría de Salud; 2005. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker S, Ruvalcaba LN. Identificación y análisis de los efectos en las condiciones de salud de los afiliados al Seguro Popular. Mexico City: Centro de investigación y docencia económicas; 2011. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 9.King G, Gakidou E, Imai K, Lakin J, Moore RT, Nall C, et al. Public policy for the poor? A randomised assessment of the Mexican universal health insurance programme. Lancet. 2009;373(9673):1447–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ávila-Burgos L, Serván-Mori E, Wirtz VJ, Sosa-Rubí SG, Salinas-Rodríguez Efectos del Seguro Popular sobre el gasto en salud en hogares mexicanos a diez años de su implementación. [Effects of the Seguro Popular on health spending in Mexican households at ten years of its implementation] Salud Publica Mex. 2013;55(Suppl 2):S91–9. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knaul FM, Frenk J. Health insurance in Mexico: achieving universal coverage through structural reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;6(24):1467–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villarreal A, Flores M. Exploring the spatial diffusion of homicides in Mexican municipalities through exploratory spatial data analysis. City scape. 2015;17(1):35–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute of Statistics and Geography. Administrative registers of deaths [Internet] Aguascalientes: The Institute; [cited 2015 Nov 3]. Available from: http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/registros/vitales/mortalidad/default.aspx. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolte E, McKee CM. Measuring the health of nations: updating an earlier analysis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;(27):1:58–71. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nolte E, McKee M. Does health care save lives? Avoidable mortality revisited [Internet] London: Nuffield Trust; 2004. [cited 2015 Nov 3]. Available from: http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/files/nuffield/publication/does-healthcare-save-lives-mar04.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elo IT, Beltrán-Sánchez H, Macinko J. The contribution of health care and other interventions to black-white disparities in life expectancy, 1980–2007. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2014;33(1):97–126. doi: 10.1007/s11113-013-9309-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franco-Marina F, Lozano R, Villa B, Soliz P. La mortalidad en México, 2000–2004 muertes evitables: magnitud, distribución y tendencias. Mexico City: Secretaría de Salud; 2006. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 18.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 19.Tobias M, Jackson G. Avoidable mortality in New Zealand, 1981–97. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25(1):12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preston S, Heuveline P, Guillot M. Demography: measuring and modeling population processes. Oxford: Blackwell; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beltrán-Sánchez H, Preston SH, Canudas-Romo V. An integrated approach to cause-of-death analysis: cause-deleted life tables and decompositions of life expectancy. Demogr Res. 2008;19(35):1323–50. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong R, Michaels-Obregon A, Palloni A. Cohort profile: the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) Int J Epidemiol. 2015 Jan 27; doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu263. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinberg N. Neither rights nor security: killings, torture, and disappearances in Mexico’s “war on drugs” [Internet] New York (NY): Human Rights Watch; 2011. Nov 9, [cited 2015 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2011/11/09/neither-rights-nor-security/killings-torture-and-disappearances-mexicos-war-drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinberg N. Mexico’s disappeared: the enduring cost of a crisis ignored [Internet] New York (NY): Human Rights Watch; 2013. Feb 20, [cited. [Google Scholar]

- 25.2015 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/02/20/mexicos-disappeared/enduring-cost-crisis-ignored

- 26.Ordorica M. La esperanza muere al último: la vida después de los 75 años. In: Figueroa B, editor. El dato en cuestión. Mexico City: Colegio de México; 2008. pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamlin J. Violence and homicide in Mexico: a global health issue. Lancet. 2015;385(9968):605–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.We standardized death rates of males in Chihuahua and US troops in Iraq (see Note 28) on the basis of the distribution by age of the national population of Mexico. The death rates of males in Chihuahua were estimated using data from National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Note 13) and the Mexican Society of Demography (Note 4).

- 29.Buzzell E, Preston SH. Mortality of American troops in the Iraq War. Popul Dev Rev. 2007;33(3):555–66. [Google Scholar]; Sosa-Rubí SG, Galárraga O, López-Ridaura R. Diabetes treatment and control: the effect of public health insurance for the poor in Mexico. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(7):512–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.053256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moloeznik MP. Organized crime, the militarization of public security, and the debate on the “new” police model in Mexico. Trends Organ Crim. 2013;16(2):177–94. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rios V. Why did Mexico become so violent? A self-reinforcing violent equilibrium caused by competition and enforcement. Trends Organ Crim. 2013;16(2):138–55. [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Bank. Violence in Colombia: building sustainable peace and social capital [Internet] Washington (DC): World Bank; 1999. Dec, [cited 2015 Nov 4]. Available from: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2000/02/03/000094946_00011405343418/Rendered/PDF/multi_page.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moncada E. Counting bodies: crime mapping, policing, and race in Colombia. Ethn Racial Stud. 2010;33(4):696–716. [Google Scholar]