Abstract

One hundred and twenty-five million women in malaria-endemic areas become pregnant each year (see Dellicour et al. PLoS Med 7: e1000221 [2010]) and require protection from infection to avoid disease and death for themselves and their offspring. Chloroquine prophylaxis was once a safe approach to prevention but has been abandoned because of drug-resistant parasites, and intermittent presumptive treatment with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, which is currently used to protect pregnant women throughout Africa, is rapidly losing its benefits for the same reason. No other drugs have yet been shown to be safe, tolerable, and effective as prevention for pregnant women, although monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine has shown promise for reducing poor pregnancy outcomes. Insecticide-treated nets provide some benefits, such as reducing placental malaria and low birth weight. However, this leaves a heavy burden of maternal, fetal, and infant morbidity and mortality that could be avoided. Women naturally acquire resistance to Plasmodium falciparum over successive pregnancies as they acquire antibodies against parasitized red cells that bind chondroitin sulfate A in the placenta, suggesting that a vaccine is feasible. Pregnant women are an important reservoir of parasites in the community, and women of reproductive age must be included in any elimination effort, but several features of malaria during pregnancy will require special consideration during the implementation of elimination programs.

Tens of millions of pregnant women are at risk of malaria every year. But controlling malaria in this population is challenging due to the placental sequestration of parasites and concerns over the safety of interventions.

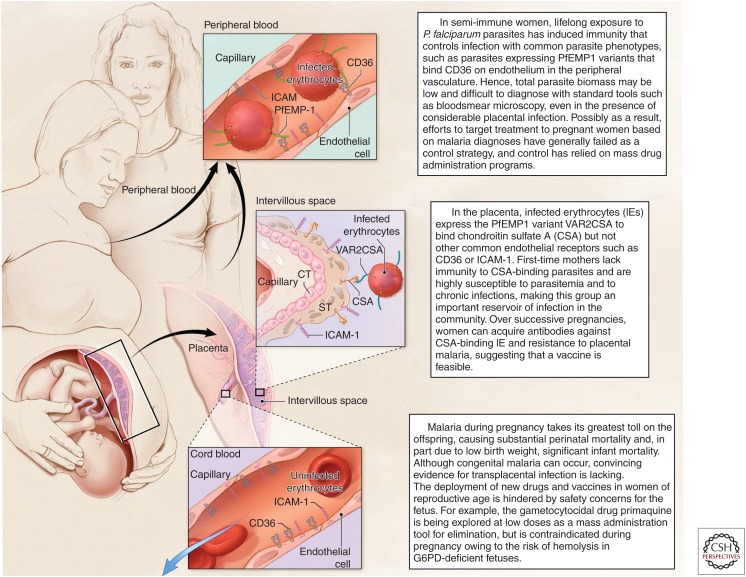

Pregnant women and women of childbearing age will require special consideration during mass campaigns for malaria elimination. Malaria susceptibility increases during pregnancy, making these women an important parasite reservoir in the community. Meanwhile, the biology and clinical presentations of Plasmodium falciparum in semi-immune women interfere with diagnosis during pregnancy, rendering targeted interventions ineffective for control (Fig. 1). Furthermore, concerns for teratogenicity and embryotoxicity complicate the proposed application of any drugs, vaccines, or antivector measures among women of reproductive age, greatly hindering mass campaign planning. For example, primaquine is the leading drug being assessed as a gametocytocidal agent to block parasite transmission to mosquitoes, but is contraindicated in pregnancy because the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase status and hence hemolysis risk of the fetus would be unknown. This chapter reviews malaria during pregnancy, including its epidemiology and disease burden, molecular pathogenesis, naturally acquired immunity and potential for vaccines, diagnostic dilemmas, and drugs being used or considered for prevention and treatment, to envision future approaches for malaria elimination that might be applied to women who may be pregnant.

Figure 1.

Malaria during pregnancy features several unique host–parasite interactions that require special attention for elimination strategies. Although malaria is more common in pregnant women than other adults, it is difficult to diagnose and therefore to control. The few drugs known to be safe during pregnancy are losing efficacy to drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum parasites, and the use of new drugs or other interventions is hindered by concerns for fetal safety. Based on the knowledge of malaria immunity during pregnancy, vaccine approaches appear promising for the control of PM, but first-generation candidates are only now entering clinical trials and it is unclear whether these products will interrupt malaria transmission in pregnant women.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND BURDEN OF DISEASE

Pregnancy malaria looks very different in areas of low and unstable transmission versus high and stable transmission, although overall disease burden in different transmission zones may be similarly heavy in the absence of preventive measures. Where malaria transmission is low and unstable, women are infected infrequently but therefore have low immunity and often rapidly progress to severe disease syndromes when infected. These women have higher risks of severe malaria and death than their nonpregnant counterparts during P. falciparum infection (Duffy and Desowitz 2001) and are more likely to develop syndromes like respiratory distress and cerebral malaria (Nosten et al. 1991). In low transmission areas, women of all parities have increased susceptibility to malaria (Nosten et al. 1991). Women in these areas should be routinely screened and promptly treated for infection to prevent the risk of severe disease and death.

In areas of stable P. falciparum malaria transmission, where approximately 50 million pregnancies occur each year, women are semi-immune and often carry their infections with few or no symptoms. Disease for mother and offspring often develops as an insidious process, and this can make it difficult to relate outcomes such as severe maternal anemia or low birth weight (LBW) back to the infection that caused these sequelae. In areas of stable transmission, primigravid women are at greatest risk, and over successive pregnancies women naturally acquire resistance to P. falciparum that reduces parasite density and prevents disease. Resistance has been associated with antibodies against the parasitized red cells that bind chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) in the placenta (Fried et al. 1998a). In communities in which malaria control has improved and the incidence of malaria decreases, the incidence of P. falciparum pregnancy malaria also decreases, but malaria-specific antibodies wane and the parasite burden and sequelae during any individual infection increase (Mayor et al. 2015).

In areas of stable transmission, interventional studies have provided evidence to estimate the burden of disease. Chemoprophylaxis with pyrimethamine/dapsone (Maloprim) in The Gambia provided significant benefits to primigravid (Greenwood et al. 1992) and grandmultigravid (parity >7) women (Greenwood et al. 1989; Menendez et al. 1994): primigravidae on prophylaxis had lower rates of parasitemia and higher hematocrits. The latter is an important effect, because maternal anemia increases risks of LBW, preterm delivery (PTD), perinatal mortality, and neonatal mortality in low- and middle-income countries (Rahman et al. 2016). In a recent meta-analysis, chemoprevention reduced the risk of moderate-to-severe maternal anemia in first- and second-time mothers by ∼40% in malaria-endemic areas (Radeva-Petrova et al. 2014); severe maternal anemia is a major risk factor for maternal mortality when women suffer postpartum hemorrhage, a common event in low-income countries (Tort et al. 2015).

Malaria prevention similarly improves child outcomes, both before and after delivery. In a meta-analysis of interventional trials, relative risk of perinatal mortality when mothers received prevention was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.53–0.99) (Garner and Gulmezoglu 2006). Effective prophylaxis reduces the risk of LBW newborns, and LBW is a strong predictor for infant mortality: extrapolating from this reduction in LBW, malaria prevention was estimated to reduce the mortality of neonates born to Gambian primigravidae by 42%, and the postneonatal mortality by 18% (Greenwood et al. 1992). In an observational birth cohort study, placental malaria (PM) in Tanzanian primigravidae was directly related to increased postneonatal mortality: 9.3% mortality for offspring of infected first-time mothers, compared with 2.6% for offspring of uninfected first-time mothers (Duffy and Fried 2011). PM in multigravid women did not significantly increase mortality risk of their offspring. In this community, the population attributable risk percent (PAR%) of postneonatal infant mortality owing to PM was 29.2% for first pregnancies.

The direct measurement of postneonatal mortality exceeds the estimates of mortality that would result from LBW, suggesting that other PM-related mechanisms might contribute to infant deaths. Several studies have related PM to increased risks of malaria infection (Schwarz et al. 2008; Goncalves et al. 2014) and to severe malaria (Goncalves et al. 2014) in offspring during infancy, but this relationship has not been observed in other studies (Awine et al. 2016). Interestingly, PM appears to influence immune responses and milieu in the offspring, which could influence their malaria susceptibility. Fetal sensitization to malaria antigens is common (Fievet et al. 1996; King et al. 2002; Malhotra et al. 2005). Some newborns of infected mothers display a “tolerant” phenotype, and have an increased risk of infection and lower hemoglobin levels during early life (Malhotra et al. 2009). Plasma cytokine levels at birth predict levels measured later during infancy, particularly for interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and also predict the risks of malaria infection and severe disease (Kabyemela et al. 2013); however, a relationship between PM and cord cytokine profiles has not been defined. More work is needed to understand whether and how PM in the mother may continue to influence malaria outcomes in her child.

Mixed malaria infections such as P. falciparum and Plasmodium vivax might also alter pregnancy malaria outcomes, but many mixed infections appear to be mono-infections when diagnosed by peripheral blood smear (BS). P. vivax, like P. falciparum, is associated with poor pregnancy outcomes, but, unlike P. falciparum, sequelae may be more common in multigravid pregnancies (reviewed in Duffy 2001). Non-falciparum infections were infrequent and did not appear to impact pregnancy outcomes in West Africa, where P. vivax was absent outside Mali (Williams et al. 2016). In P. vivax–endemic areas, women should be actively screened and treated, but management is complicated because primaquine is contraindicated due to fetal hemolysis risk and, therefore, liver hypnozoite parasite forms remain and cause relapses in the mother.

MOLECULAR PATHOGENESIS

In stable transmission zones, malaria during pregnancy has a unique epidemiology characterized by parity-dependent susceptibility: primigravid women are infected more frequently and with higher placental parasite densities than multigravid women. A prominent feature of P. falciparum malaria during pregnancy is the accumulation of parasites in the placenta, whereas parasite density in the peripheral circulation is low or undetectable (Brabin 1983; McGregor 1984). For decades, the increased susceptibility to malaria during pregnancy was attributed to immunological changes associated with pregnancy, but this could not explain the reduction in infection rate and placental parasite burden over successive pregnancies.

An alternative molecular model to explain parity-dependent susceptibility is based on the ability of P. falciparum infected erythrocytes (IEs) to adhere to receptors on the vascular endothelium and thereby sequester in deep vascular beds. During pregnancy, IEs accumulate in the intervillous spaces or bind to the surface of the syncytiotrophoblast in the placenta. In this model, the placenta presents a new receptor for IE adhesion, thereby selecting a parasite subpopulation to which women are naïve before their first pregnancy, making first-time mothers most susceptible. Analyses of the binding profile of placental IE have shown that this parasite subpopulation adheres to placental CSA, and not to CD36, which commonly supports the binding of IE from nonpregnant individuals (Fried and Duffy 1996). With successive pregnancies, women develop specific antibodies to CSA binding and placental IEs that enable them to better control the infection (Fried et al. 1998a); immunoepidemiology studies that support this model are discussed below. Following the identification of CSA as the unique receptor that supports parasite adhesion in the placenta, additional studies conducted at different sites have confirmed this binding phenotype (Fried et al. 1998a, 2006; Beeson et al. 1999; Maubert et al. 2000; Muthusamy et al. 2007).

CSA is a glycosaminoglycan comprising repeats of the disaccharide d-glucoronic acid and N-acetyl-d-galactosamine (GalNAc). CSA is sulfated at the C4 position of GalNAc. The closely related glycosaminoglycans chondroitin sulfate B and chondroitin sulfate C do not support placental IE adhesion. CSA chains vary in their length and degree of sulfation, and further characterization has shown that a low-sulfated CSA (Achur et al. 2000; Alkhalil et al. 2000; Fried et al. 2000; Andrews et al. 2005) of at least six disaccharide repeats (Alkhalil et al. 2000) is optimal to support placental IE adhesion.

IE sequestration in the placenta is followed by the accumulation of macrophages and B cells in the intervillous spaces. The intensity of the inflammatory immune infiltrate varies between women and is inversely related to acquired immunity: macrophages are more commonly observed in placentas from primigravidae who lack specific immunity to placental IE than in those from multigravidae (Garnham 1938; Muehlenbachs et al. 2007).

The cytokine milieu in a healthy uninfected placenta displays a bias toward type 2 cytokines. PM leads to marked changes in the cytokine milieu, including increased levels of TNF-α, interferon γ (IFN-γ), IL-10, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, macrophage inflammatory protein 1 (MIP-1α and MIP-1β), CXC ligand 8, CXC ligand 9, and CXC ligand 13 (Fried et al. 1998b; Moormann et al. 1999; Abrams et al. 2003; Chaisavaneeyakorn et al. 2003; Rogerson et al. 2003; Suguitan et al. 2003a,b; Kabyemela et al. 2008; Dong et al. 2012). Increased levels of the cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ, and the chemokine CXCL9 that is regulated by IFN-γ, have been associated with LBW deliveries, especially among primigravid women (Fried et al. 1998b; Rogerson et al. 2003; Kabyemela et al. 2008; Dong et al. 2012). Similarly, transcript levels for the chemokines CXCL13, CXCL9, and CCL18 negatively correlate with birth weight, and up-regulation of IL-8 and TNF-α transcription in the placenta has been associated with intrauterine growth retardation (Moormann et al. 1999; Muehlenbachs et al. 2007). These studies support but do not prove that these inflammatory mediators contribute to PM sequelae. Animal models that reproduce placental sequestration and inflammation are needed for mechanistic studies to better understand disease pathogenesis.

IMMUNITY AND VACCINES

Parity-Dependent Acquisition of Antibodies

The unique epidemiology of pregnancy malaria is characterized by parity-dependent susceptibility. Different approaches to evaluate parity-dependent humoral immunity have included serum or plasma reactivity to the IE surface by flow cytometry, adhesion-blocking activity, agglutination of IE, and opsonizing activity (Table 1). Regardless of assay, parity-dependent acquisition of antibody against placental parasites or CSA-binding laboratory isolates has been consistently observed across many studies. Levels of antibodies that surface-react are higher in multigravidae compared with primigravidae in many different countries (Fried et al. 1998a; Ricke et al. 2000; Staalsoe et al. 2001, 2004; Tuikue Ndam et al. 2004; Megnekou et al. 2005; Fievet et al. 2006; Feng et al. 2009; Aitken et al. 2010; Mayor et al. 2011). Adhesion-blocking antibody levels are significantly higher among multigravid than primigravid women (Fried et al. 1998a; O’Neil-Dunne et al. 2001; Jaworowski et al. 2009; Ndam et al. 2015). Although agglutination of placental parasites is uncommon (Beeson et al. 1999), the proportion of serum samples with agglutinating antibodies was significantly higher among multigravidae than primigravidae (Beeson et al. 1999; Maubert et al. 1999). Similarly, opsonic phagocytosis increased with parity (Keen et al. 2007; Jaworowski et al. 2009). Thus, antibodies to CSA-binding IE or placental parasites provide a robust correlate of parity-dependent resistance, regardless of assay.

Table 1.

Studies of naturally acquired antiparasite antibodies and parity

| Reference/study (year) | Test | Parasite tested | Plasma/sera collected at | n | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ricke et al. 2000 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Third trimester | P: 30 S: 30 M: 103 |

Increase with parity |

| Staalsoe et al. 2001, 2004 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Third trimester; delivery | P: 78 S: 105 |

Increase with parity |

| Megnekou et al. 2005 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Combined second–third trimesters | P: 101 S/M: 114 |

Increase with parity |

| Fievet et al. 2006 | Surface proteins by flow | Placental parasites | Second trimester | P: 62 S: 50 M: 153 |

Increase with parity |

| Feng et al. 2009 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Second trimester | P: 80 S: 16 M: 45 |

Increase with parity |

| Aitken et al. 2010 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Second and third trimesters | P: 131 S: 108 M: 310 |

Increase with parity |

| Brolin et al. 2010 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Third trimester | P: 189 S: 21 M: 72 |

Increase with parity |

| Mayor et al. 2011 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected, placental parasites | Delivery | P: 30 M: 60 |

PM−: M > P PM+: M > P for placental isolates |

| Fried et al. 1998a | Anti-adhesion | Placental parasites | Delivery | P: 51 S: 62 M: 84 |

Increase with parity |

| O’Neil-Dunne et al. 2001 | Anti-adhesion | CSA-selected | During pregnancy | P: 45 S/M: 84 |

Increase with parity at gestational age of 12–20 wk |

| Jaworowski et al. 2009 | Anti-adhesion | CSA-selected | Third trimester | P: 44 M: 29 |

Increase with parity |

| Beeson et al. 1999, 2004 | Agglutination | Placental parasites | Second trimester | P: 12 M:12 |

Increase with parity |

| Maubert et al. 1999 | Agglutination | CSA-selected, placental parasites | Delivery | P: 13–76a M: 17–143a |

PM+: Increase with parity for 2/4 isolates |

| Keen et al. 2007 | Opsonizing activity | CSA-selected | Postpartum | P: 21 M: 16 |

Increase with parity |

| Jaworowski et al. 2009 | Opsonizing activity | CSA-selected | Third trimester | P: 44 M: 29 |

Increase with parity |

| Feng et al. 2009 | Opsonizing activity | CSA-selected | Second trimester | P: 80 S: 16 M: 45 |

Increase with parity |

Only studies that analyzed more than five subjects per group are included.

P, Primigravidae; S, secundigravidae; M, multigravidae; PM+, malaria-infected; PM−, uninfected; CSA, chondroitin sulfate A.

aNumber of plasma samples analyzed vary among tested isolates.

Antibodies to Placental Parasites and Infection Status or Infection Risk

Garnham (1938) described three phases of PM based on histology. In the acute or active infection phase, IE accumulate in the intervillous spaces. In the next phase, now called chronic infection, maternal inflammatory cells accumulate, notably monocytes–macrophages containing malaria pigment (hemozoin). After IE are cleared, parasite pigment remains in the intervillous fibrin, sometimes persisting for months, depending on the parasite burden and corresponding amount of pigment (McGready et al. 2002; Muehlenbachs et al. 2010). This last phase of the infection is referred to as past infection. This chronology of PM is typical for primigravidae, but not for multigravidae who usually clear placental parasites quickly and do not progress beyond the active infection phase. Poor outcomes related to PM, such as LBW and maternal anemia, are most strongly associated with the chronic phase of infection (Ordi et al. 1998; Ismail et al. 2000; Shulman et al. 2001; Muehlenbachs et al. 2010).

The relationship of antibodies to infection status or infection risk has varied between studies (Table 2). This may be due, in part, to the heterogeneous chronology of placental infections, and in part to the effect of infection to boost antibodies. In three of four studies, anti-adhesion antibodies have been associated with a reduced risk of infection, or to reduced parasite densities in infected women, supporting a role in protection. Opsonizing activity, agglutinating activity, and IE surface reactivity are elevated during and after an infection, which confounds efforts to assess their relationship with protection against infection. Because naturally acquired immunity to malaria controls infection but does not confer sterile resistance that completely prevents infection, infections also occur in semi-immune multigravidae, and infection boosts their antibody levels (Table 2). As a consequence, increased levels of antibodies, including those that agglutinate, opsonize, or react to the surface of IE, can reflect current or recent exposure to the parasite and thereby confound efforts to find correlates of protection (Ataide et al. 2010).

Table 2.

Studies of naturally acquired antiparasite antibodies and malaria infection status

| Reference/study (year) | Test | Parasite tested | Plasma/sera collected at | n | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staalsoe et al. 2001 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Third trimester | P: 55 M: 58 |

Multigravid: inverse correlation between Abs and parasite density |

| Staalsoe et al. 2004 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Delivery | All 477 | Chronic and past infection > PM− and acute infection, regardless of parity |

| Beeson et al. 2004 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Delivery | P: 54 M: 54 |

Primigravid: PM+ > PM− Multigravid: no differences |

| Elliott et al. 2005 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Delivery | P: 46 M: 20 |

Primigravid: PM+ > PM− for IgG1, IgG3 Multigravid: no differences |

| Ataide et al. 2010 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Third trimester | P: 268 | Primigravid: PM+ > PM− |

| Ataide et al. 2011 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Third trimester | S: 187 | Secundigravid: PM+ > PM− |

| Tutterrow et al. 2012a | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Second–third trimester | Total 27 | PM− > PM+ |

| Mayor et al. 2011, 2013 | Surface proteins by flow | Placental parasites | Delivery | Total 293 | Acute, chronic, and past infections > PM−, regardless of parity |

| Fried et al. 1998 | Anti-adhesion | Placental parasites | Delivery | P: 29 S: 68 M: 46 |

Secundigravid: PM− > PM+ Primigravid: low activity, no differences Multigravid: high activity, no differences |

| O’Neil-Dunne et al. 2001 | Anti-adhesion | CSA-selected | Delivery | Total 97 | Inverse correlation between Abs and placental parasite density |

| Beeson et al. 2004 | Anti-adhesion | CSA-selected | Delivery | P: 54 M: 54 |

Primigravid: PM+ > PM− Multigravid: no differences |

| Ndam et al. 2015 | Anti-adhesion | CSA-selected | Delivery | Total 266 | PM− > PM+ |

| Beeson et al. 2004 | Agglutination | CSA-selected placental parasites | Delivery | P:54 M:54 |

Primigravid and multigravid: PM+ > PM− |

| Ataide et al. 2010 | Opsonizing activity | CSA-selected | Third trimester | P:268 | Primigravid: PM+ > PM− |

| Ataide et al. 2011 | Opsonizing activity | CSA-selected | Third trimester | S: 187 | Secundigravid: PM+ > PM− |

PM+, Placental malaria positive, defined by the presence of parasites in the placenta; PM−, no parasites or the evidence of past infection by histology; CSA, chondroitin sulfate A.

Immune Responses and Pregnancy Outcomes

PM commonly leads to severe maternal anemia and LBW deliveries, especially among primigravidae. The association between naturally acquired antibodies and pregnancy outcomes has been seen in some but not all studies, and notably the target population and antibody assay have differed between studies (Table 3). Among Kenyan women with chronic malaria, low serum reactivity to the surface of CSA-binding laboratory IE was associated with lower hemoglobin level and reduced birth weight (Staalsoe et al. 2004). Among 141 malaria-infected women in Malawi (Feng et al. 2009), serum reactivity to the IE surface during the second trimester was lower among the women who presented with anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dL) at the time of delivery (Feng et al. 2009). Opsonic activity among malaria-infected secundigravid women in Malawi was associated with increased birth weight, and opsonic activity was higher among nonanemic than anemic malaria-infected multigravidae (Jaworowski et al. 2009; Ataide et al. 2011). Among Mozambican women who had been infected during pregnancy, high serum reactivity to both placental and children’s IE at the time of delivery was associated with increased birth weight and gestational age (Mayor et al. 2013). In Kenya, levels of anti-adhesion antibodies to placental IE were associated with increased birth weight and gestational age among offspring of secundigravidae (Duffy and Fried 2003). In Benin, anti-adhesion antibodies reduced the likelihood of LBW deliveries (Ndam et al. 2015). Among multigravid women, anti-adhesion antibodies have not been associated with risks of maternal anemia and LBW (Duffy and Fried 2003; Jaworowski et al. 2009), presumably because as a group these women enjoy protective immunity. Together, these studies provide strong support for the idea that antibodies to placental IE confer protection, but do not indicate which antibody effector mechanism(s) is primarily responsible.

Table 3.

Studies of naturally acquired antiparasite antibodies and pregnancy outcomes

| Reference/study (year) | Test | Parasite tested | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staalsoe et al. 2004 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Among women with chronic malaria, high IgG associated to increased maternal HGB and BW |

| Beeson et al. 2004 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | No association to BW or maternal HGB |

| Feng et al. 2009 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | PM+: Abs at weeks 14–26 associated to decreased maternal anemia (HGB < 10 g/dL) |

| Aitken et al. 2010 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | No association to maternal anemia, BW, and GA |

| Serra-Casas et al. 2010 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | No association to LBW, GA, and maternal anemia |

| Ataide et al. 2010 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Primigravid: no association to LBW or anemia |

| Ataide et al. 2011 | Surface proteins by flow | CSA-selected | Secundigravid PM+: no correlation with BW or maternal HGB |

| Mayor et al. 2013 | Surface proteins by flow | Placental parasites | High Abs to placental and child isolates associated to increased BW |

| Duffy and Fried 2003 | Anti-adhesion | Placental parasites | Anti-adhesion Abs associated to increased BW, GA |

| Beeson et al. 2004 | Anti-adhesion | CSA-selected | No association to BW or maternal HGB |

| Jaworowski et al. 2009 | Anti-adhesion | CSA-selected | Multigravid: no association to maternal HGB or BW |

| Ndam et al. 2015 | Anti-adhesion | CSA-selected | Anti-adhesion Abs associated to decreased LBW and SGA |

| Beeson et al. 2004 | Agglutination | CSA-selected | No association to BW or maternal HGB |

| Feng et al. 2009 | Opsonizing activity | CSA-selected | PM+: Abs at weeks 14–26 associated to decreased maternal anemia (HGB < 11 g/dL) |

| Jaworowski et al. 2009 | Opsonizing activity | CSA-selected | Multigravid PM+: lower opsonic activity in anemic (HGB < 11 g/dL); no association to BW |

| Ataide et al. 2010 | Opsonizing activity | CSA-selected | Primigravid: no association to LBW or maternal anemia |

| Ataide et al. 2011 | Opsonizing activity | CSA-selected | Secundigravid PM+: correlated with BW |

P, Primigravidae; S, secundigravidae; M, multigravidae; CSA, chondroitin sulfate A; PM+, malaria-infected; PM−, uninfected; HGB, hemoglobin; BW, birth weight; LBW, low birth weight; GA, gestational age.

PREGNANCY MALARIA VACCINE DEVELOPMENT

Currently, the leading candidate for a vaccine to prevent pregnancy malaria is VAR2CSA, a member of the var gene or PfEMP1 protein family that is up-regulated in placental parasites as well as CSA-selected laboratory parasites (Salanti et al. 2003; Tuikue Ndam et al. 2005). VAR2CSA is a large protein of ∼350 kDa comprising six extracellular Duffy-binding-like (DBL) domains and is too large to manufacture as an intact molecule. Therefore, immunogens being considered for product development incorporate one or a few domains, with or without adjacent interdomain regions.

Several studies compared primigravid to multigravid women for their seroreactivity with different VAR2CSA domains (Table 4). Parity-dependent acquisition of VAR2CSA domain-specific antibody has varied between studies. This could reflect differences in the recombinant proteins based on expression system, allelic variant, or domain boundaries, or differences in study populations such as transmission intensity, gestational age, or prevalence of infection at the time of serum sampling.

Table 4.

Studies of naturally acquired VAR2CSA antibodies and parity

| Domain | Parity effect | Abs measured at | Study site year, transmission pattern | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBL1 | Yes | Delivery | 2001–2005, Muheza-Tanzania, perennial | Oleinikov et al. 2007 |

| No | Enrollmenta and delivery | 2001, Thiadiaye-Senegal, seasonal | Tuikue Ndam et al. 2006 | |

| DBL1–DBL2 | Yes | Enrollmenta and delivery | 2008–2010, Comé-Benin, perennial | Ndam et al. 2015 |

| DBL2 | No | Enrollmenta and delivery | 2001, Thiadiaye-Senegal, seasonal | Dechavanne et al. 2015 |

| Yes | Delivery | 2003–2006, Manhica-Mozambique, perennial | Mayor et al. 2013 | |

| ID1-ID2a | No | All trimesters | 1994–1996 and 2001–2005, Ngali II and Yaoundé Cameroon, high transmission and low transmission | Babakhanyan et al. 2014 |

| DBL3 | Yes | Delivery | 2001–2005, Muheza-Tanzania, holoendemic | Oleinikov et al. 2007 |

| Enrollmenta and delivery | 2008–2010, Comé-Benin, perennial | Ndam et al. 2015 | ||

| No | Third trimester | 2000–2002, Blantyre-Malawi, perennial | Brolin et al. 2010 | |

| Delivery | 2003–2006, Manhica-Mozambique, perennial | Mayor et al. 2013 | ||

| DBL4 | Yes | Delivery | 2008–2010, Comé-Benin, perennial | Ndam et al. 2015 |

| No | Delivery | 2001–2005, Muheza-Tanzania, perennial | Oleinikov et al. 2007 | |

| Enrollmenta | 2008–2010, Comé-Benin, perennial | Ndam et al. 2015 | ||

| DBL5 | Yes | Delivery | Ghanab, seasonal | Salanti et al. 2004 |

| Enrollmenta and delivery | 2001, Thiadiaye-Senegal, seasonal | Tuikue Ndam et al. 2006 | ||

| Third trimester | 2000–2002, Blantyre-Malawi, perennial | Brolin et al. 2010 | ||

| During pregnancyc | 2005–2008, Ouidah-Benin, perennial | Gnidehou et al. 2010 | ||

| Delivery | 2003–2006, Manhica-Mozambique, perennial | Mayor et al. 2013 | ||

| Enrollmenta | 2008–2010, Comé-Benin, perennial | Ndam et al. 2015 | ||

| No | Delivery | 2001–2005, Muheza-Tanzania, perennial | Oleinikov et al. 2007 | |

| Enrollmenta and delivery | 2001, Thiadiaye-Senegal, seasonal | Dechavanne et al. 2015 | ||

| Delivery | 2008–2010, Comé-Benin, perennial | Ndam et al. 2015 | ||

| DBL6 | Yes | Enrollmenta and delivery | 2001, Thiadiaye-Senegal, seasonal | Tuikue Ndam et al. 2006 |

| Delivery | 2001–2005, Muheza-Tanzania, perennial | Oleinikov et al. 2007 | ||

| Delivery | 2003–2006, Manhica-Mozambique, perennial | Mayor et al. 2013 | ||

| No | Third trimester | 2000–2002, Blantyre-Malawi, perennial | Brolin et al. 2010 | |

| Enrollmenta and delivery | 2001, Thiadiaye-Senegal, seasonal | Dechavanne et al. 2015 |

aSamples collected at enrollment at any time during the first 6 months of gestation.

bStudy year and site information not available.

cSamples collected during pregnancy, but timing not specified.

Antibody boosting during infection can confound attempts to distinguish between protective antibodies and markers of exposure. Perhaps, for this reason, VAR2CSA antibodies have not been related to protection from infection in many studies. After measuring antibody levels to individual DBL domains and domain combinations, Tutterrow et al. (2012a) concluded that antibodies to multiple domains and alleles are needed to reduce PM risk. In Benin, high levels of VAR2CSA-DBL3x antibody during the first two trimesters reduced the risk of PM, although a similar trend was observed with antibody to an unrelated VAR domain (Ndam et al. 2015).

Relationships between VAR2CSA antibodies and pregnancy outcomes have also varied between studies. Among Kenyan women with acute or chronic malaria infection, higher DBL5 antibody levels reduced the risk of LBW delivery (Salanti et al. 2004). Among Mozambican women infected at least once during their pregnancy, above-the-median antibody levels to DBL3X and DBL6ɛ, as well as the unrelated merozoite antigen AMA1, were associated with increased birth weight and gestational age (Mayor et al. 2013). In Benin, high DBL1-ID1-DBL2 antibody levels during the first two trimesters reduced the risk of LBW (Ndam et al. 2015). Additional studies that define relationships between specific antibody and protection are needed to advance the development of a vaccine to prevent malaria during pregnancy.

DIAGNOSIS

Despite its large burden of disease, P. falciparum infection can be difficult to diagnose during pregnancy, particularly in semi-immune women who often are asymptomatic during infection. Although IEs accumulate in the placenta, parasite density in peripheral blood can be too low for detection by routine BS microscopy. BS is the gold standard for malaria diagnosis and is ideal for discriminating the different human malaria parasite species; however, quality varies substantially, and the requirement for microscope and trained microscopist limits BS availability or quality in many places. Paradoxically, although pregnancy malaria is difficult to recognize and diagnose, many women in endemic areas unnecessarily receive antimalarial treatments in the absence of infection. In Mozambique, BS was negative in more than 70% of pregnant women with clinical symptoms of malaria (Bardaji et al. 2008). Because antimalarials are often prescribed on the basis of clinical and not laboratory criteria, many pregnant women receive unnecessary treatment with drugs that have an unclear safety profile especially in the first trimester.

Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) are a more recent tool that is gaining wider acceptance for diagnosis in the general population. RDTs use immunochromatographic approaches to detect soluble Plasmodium antigens, including histidine-rich protein-2 (HRP-2), aldolase, and parasite lactate dehydrogenase (pLDH). The OptiMAL test, based on pLDH detection, gave varying results when compared with peripheral BS in different studies of pregnant women, with sensitivity ranging from 15% to 97% and specificity from 91% to 98% (Mankhambo et al. 2002; VanderJagt et al. 2005; Tagbor et al. 2008). The sensitivity of the OptiMAL test increases with parasite density, and all samples with parasite density <100 per μl were misdiagnosed in one study (VanderJagt et al. 2005). In a larger study (Tagbor et al. 2008), OptiMal had 100% sensitivity and 93% specificity for parasite densities >50 per μl blood, but sensitivity of only 57% at lower densities. RDTs that detect pLDH have the advantage that they are designed to detect only live parasites; however, gametocytemia in the absence of asexual blood stage parasites can still produce positive results.

In general, RDTs that detect HRP-2 have a higher sensitivity than those that detect pLDH. In one study, RDT-HRP-2 sensitivity was greater than 90% when compared with peripheral BS, and 80%–95% when compared with placental BS with specificity between 61% and 94% (Leke et al. 1999; Mockenhaupt et al. 2002; Singer et al. 2004; Mayor et al. 2012). In a multicenter study in West Africa, RDTs that combine the detection of pLDH and HRP-2 showed similar good sensitivity at some but not all sites (range 63.6%–95.1% in primigravidae) when compared with diagnoses using BS and PCR at first antenatal visits, but not at subsequent visits or at delivery in Ghanaian women (<60% sensitivity in all parity groups at delivery) (Williams et al. 2015). In Papua New Guinea, HRP-2/pLDH RDTs were deemed insufficiently sensitive for intermittent screening of asymptomatic anemic women (Umbers et al. 2015). A weakness of RDT-HRP-2 tests is the prolonged half-life of the antigen. HRP-2 can be identified in plasma samples several weeks after parasite clearance, and therefore cannot distinguish current from recent infection (Wongsrichanalai et al. 1999; Mayxay et al. 2001; Tjitra et al. 2001). In Burkina Faso, 2/32 parasitemic pregnant women continued to have detectable HRP-2 antigen 28 d after receiving artemisinin combination therapy (Kattenberg et al. 2012). These shortcomings hinder the use of existing RDTs for managing malaria or monitoring treatment efficacy during pregnancy.

DRUGS FOR PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Intermittent Presumptive Treatment (IPTp)

PM is associated with maternal anemia, LBW deliveries, PTD, and fetal loss. Severe maternal anemia increases the risk of maternal death, and both LBW and PTD increase the risk of infant death. To avoid these poor outcomes, measures to prevent PM have been recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). The first agent used to prevent PM was weekly choloroquine (CQ) at a prophylaxis dose. However, the emergence of CQ-resistant parasites in sub-Saharan Africa during the 1980s prompted the search for new strategies. A 1992 study in Malawi showed that two treatment doses of SP given during the second and early third trimester significantly reduced the prevalence of PM compared with CQ (Schultz et al. 1994). A subsequent trial in Kenya confirmed that two SP treatment doses reduced PM prevalence in HIV-infected women (Table 5) (Parise et al. 1998).

Table 5.

Studies of IPTp-SP efficacya

| References | Study site | Study years | n | Study design | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schultz et al. 1994 | Mangochi district, Malawi, high transmission | 1992 | 357 (placental BS n = 159) | Assigned to one of three arms: (1) weekly CQ, (2) one dose SP followed by weekly CQ, (3) two doses SP | Two doses significantly reduced the rate of peripheral and placental parasitemia |

| Verhoeff et al. 1998 | Chikwawa district, Malawi, high transmission | 1993–1994 | 1837 delivery data: 575 | Observational, enrollment at first ANC visit, outcomes measured at delivery | At delivery, no differences in prevalence of placental or peripheral parasitemia between one and two doses |

| Parise et al. 1998 | Kisumu, Kenya, high transmission | 1994–1996 | 2077 | Assigned to one of three arms: (1) two doses SP, (2) monthly doses of SP between enrollment and gestational week 34, (3) case management with SP | Two doses or monthly SP significantly reduced the prevalence of infection detected in peripheral and placental samples |

| Shulman et al. 1999 | Kilifi, Kenya, hyperholoendemic and mesoendemic sites | 1996–1997 | 1264 | Double-blind, randomized, controlled; number of SP doses (1–3) based on gestational age at enrollment | At gestational week 34, ≥one dose of IPTp-SP significantly reduced the prevalence of peripheral parasitemia; PM: significantly higher proportion of negative by histology in the treatment group; no differences by BS |

| Feng et al. 2010 | Blantyre, Malawi, low transmission | 1997–2006 | 8131 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | 1997–2001: number of IPTp-SP doses associated with protection from PM 2002–2006: IPTp-SP not associated with a reduction in PM |

| Harrington et al. 2009 | Muheza, Tanzania, high transmission | 2002–2005 | 880 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | No IPTp versus ≥ one dose: SP usage associated with increased placental parasite density |

| Gies et al. 2009 | Boromo, Burkina Faso, seasonal, high transmission | 2004–2006 | 915 (peripheral blood) 878 (placental blood) | Substudy of larger study to evaluate IPTp | None to one versus > two doses: reduction in the prevalence of infection detected in peripheral and placental blood |

| Tiono et al. 2009 | Bousse district, Burkina Faso, seasonal, high transmission | 2004–2005 | 648 | Randomized, three treatment arms: (1) IPTp-SP, (2) weekly CQ, (3) IPTp-CQ | At delivery, the prevalence of maternal peripheral parasitemia significantly lower in IPTp-SP than CQ group; significant reduction in PM in IPTp-SP versus weekly CQ but not versus IPTp-CQ |

| Menendez et al. 2008 | Manhica district, Mozambique, moderate transmission | 2003–2005 | 1030 | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled | Placebo + ITN versus SP + ITN: no difference in placental infection Reduction in the prevalence of peripheral blood parasitemia and active placental infection |

| Ndyomugyenyi et al. 2011 | Kabale district, Uganda, low and unstable transmission | 2004–2007 | 5328 | Randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded for SP versus placebo but not for ITN use | IPTp versus ITN versus IPTp + ITN: no differences in infection rate at gestational weeks 36–40 and at delivery |

| Hommerich et al. 2007 | Agogo, Ghana, hyper- to holoendemic | 2006 | 226 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | No IPTp versus ≥ one SP dose: SP associated with decreased placental infection detected by RDT and PCR but not by microscopy |

| Diakite et al. 2011 | Bla district, Mali, seasonal, high transmission | 2006–2008 | 814 | Randomized to two treatment arms: (1) two SP does, (2) three SP doses | PM reduced by half after three doses versus two doses |

| Vanga-Bosson et al. 2011 | Côte d’Ivoire, six sites (four urban, two semiurban) in three regions | 2008 | 2044 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | None versus one to two doses: reduction in PM |

| Wilson et al. 2011 | Accra, Ghana, moderate transmission | 2009 | 363 | Observational, enrollment at ANC (third trimester) | Prior use of IPTp significantly reduced maternal infection |

| Gutman et al. 2013 | Machinga, Malawi, high transmission | 2010 | 703 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | None to one dose versus ≥ two doses: number of doses had no effect on placental and peripheral parasitemia |

| Gutman et al. 2015 | Machinga and Blantyre, Malawi, high and low transmission | Machinga: 2010 Blantyre: 2009–2011 |

Machinga: 710 Blantyre: 1141 |

Observational, enrollment at delivery | Sextuple mutated haplotype in Pfdhfr/Pfdhps associated with significant increase in placental and peripheral parasitemia and parasite density |

| Mace et al. 2015 | Mansa, Zambia, high transmission | 2009–2011 | 435 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | <two versus ≥ two doses: no difference in PM, a decrease in any infection (placental including past infection and peripheral blood) among primigravidae |

| Toure et al. 2014 | Côte d’Ivoire, six sites (three rural, three urban), perennial transmission with seasonal peaks | 2009–2010 | 1317 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | None versus one versus ≥ two doses: no differences in PM |

| Cisse et al. 2014 | Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, seasonal, high transmission | 2010 | 579 | Observational, enrollment during routine ANC visit | No association between SP usage and malaria infection prevalence during pregnancy; lower parasite density in women that used SP |

| Coulibaly et al. 2014 | Kita and Kayes regions, Mali; Ziniaré, Burkina Faso, seasonal high transmission | 2009–2010 2010–2011 |

268 (Mali) 312 (BF) |

IPTp-SP for clearing asymptomatic infection during pregnancy | Low treatment failure: 1.1% at day 42, PCR adjusted |

| van Spronsen et al. 2012 | Gushegu, Ghana, high transmission | 2010 | 145 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | No association between IPTp usage, number of SP doses, and PM |

| Tonga et al. 2013 | Sanaga-Maritime Littoral region, Cameroon, hyperendemic | 2011–2012 | 201 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | None to one versus > two doses IPTp: no difference in PM rate |

| Arinaitwe et al. 2013 | Tororo, Uganda, high transmission | 2011 | 566 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | <two versus ≥ two doses: no differences in PM rate or parasite density |

| Braun et al. 2015 | Fort Portal, western Uganda, mesoendemic | 2013 | 728 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | None versus one to two doses: no differences in placental or peripheral infection rate |

| Mpogoro et al. 2014 | Geita region, Tanzania, high transmission | 2014 | 431 | Observational, enrollment at delivery | <three versus ≥ three SP doses: ≥three doses associated with a reduction in PM (26/431 received ≥three doses) |

SP, Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine; CQ, chloroquine; BW, birth weight; LBW, low birth weight; PTD, preterm delivery; SGA, small for gestational age; ITN, insecticide-treated net.

aResults from adjusted models presented.

In the early 2000s, WHO recommended intermittent presumptive treatment (IPTp) for pregnant women in malaria-endemic regions, with at least two curative doses of the antimalarial drug SP, one dose in the second and the other dose in the third trimester of pregnancy. In 2012, WHO updated the recommendation, increasing the number to three or more SP doses. In practice, women in areas of moderate–high malaria transmission should receive SP at each antenatal care visit during the second and third trimesters (because four visits are recommended), with 1 mo intervals between doses (www.who.int/malaria/areas/preventive_therapies/pregnancy/en).

Owing to the spread of SP resistance in sub-Saharan Africa, artemisinin-based combinations (ACTs) were adopted as the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria in the 2000s (Eastman and Fidock 2009). Even as the general population was switching to ACT as treatment policy, the IPTp-SP strategy was being widely adopted for pregnant women. At present, WHO continues to recommend IPTp-SP, even in areas with high levels of SP resistance and treatment failure. Here, we summarize studies that have examined the associations between IPTp-SP and malaria parasitemia detected in maternal peripheral blood or placental blood (Table 5). We do not include studies that only reported an association between IPTp-SP and other pregnancy outcomes because the main goal of IPTp-SP is to improve pregnancy outcomes by preventing PM. Improved outcomes without an effect on parasitological measures are difficult to interpret.

During the years 1992–2002, IPTp-SP significantly reduced PM in studies conducted across Africa. However, most data collected after 2001–2002 in East and Southeast Africa indicate that IPTp-SP lost its efficacy to reduce PM prevalence and/or parasite density. This trend has progressed to West Africa, where one site in Ghana reported that IPTp-SP did not reduce PM prevalence (van Spronsen et al. 2012).

SP resistance results from accumulating mutations in dhfr and dhps genes. The quintuple P. falciparum mutations (three in Pfdhfr and two mutations in Pfdhps) have been associated with treatment failure (Kublin et al. 2002; Naidoo and Roper 2013), and increased placental parasite density with an increasing number of Pfdhfr mutations (Mockenhaupt et al. 2007). A WHO document published in November 2015 (www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/istp-and-act-in-pregnancy.pdf) stated that “An association between sextuple mutant haplotypes of P. falciparum and decreased birth weight has been reported in observational studies in a few sites in East Africa. Further studies are required to assess this and to devise the best and most cost-effective prevention strategies in areas of very high SP resistance.” The policy of continuing IPTp-SP in areas of high resistance is puzzling and inconsistent with WHO directives for malaria treatment (Nosten and McGready 2015), as well as studies that strongly relate dhfr/dhps mutations to treatment failure.

Currently, IPTp-SP remains efficacious for reducing the rate of PM and/or parasite burden at some sites in West Africa. However, even in areas with low or moderate SP resistance, the IPTp strategy does not completely prevent PM and the protective effects depend on the timing of the first dose and the interval between treatments (Nosten and McGready 2015).

Alternatives to IPTp-SP

Dihydroartemisinin–Piperaquine

A comparison between three doses of IPTp-SP and three doses or monthly dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine (DP) was recently conducted in Uganda (Kakuru et al. 2016). Peripheral blood parasitemia detected by LAMP was significantly higher in the IPTp-SP group than three doses or monthly DP. Similarly, PM (combined active and past infection) was significantly higher among women who received IPTp-SP than women that received three doses or monthly treatment with DP. Although, among primigravid women, the rate of PM was similar between the three groups, the amount of pigment deposition was significantly higher in the IPTp-SP groups, which might indicate higher parasite densities in past infections. The risk of any poor pregnancy outcome (PTD, LBW, congenital anomaly, stillbirth, spontaneous abortion) was significantly lower among women receiving monthly DP than women who received three doses of DP or IPTp-SP.

Mefloquine

In a comparison of IPTp-SP and IPTp-mefloquine (MQ) (Briand et al. 2009), Beninese women received either two doses of IPTp-SP or two doses of MQ (15 mg/kg) during pregnancy. PM was significantly less frequent in the MQ group, but other endpoints including birth weight, LBW, and maternal anemia were similar (Briand et al. 2009). Adverse events were more common with MQ, and overall tolerability was lower (Briand et al. 2009). Another trial compared two doses of IPTp with SP or MQ in women who also received long-lasting insecticide-treated nets. MQ was given as a single 15 mg/kg dose or as a split dose (Gonzalez et al. 2014a). The rates of maternal parasitemia (by BS) at delivery, mild anemia at delivery, and clinical malaria during pregnancy were significantly lower in the MQ group, while PM (by BS or histology), birth weight, and LBW rates were similar (Gonzalez et al. 2014a). As in Benin, tolerability was poor even in the group that received MQ as a split dose (Gonzalez et al. 2014a).

IPTp-SP is not recommended for HIV-infected women who take daily cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, owing to the potential adverse effects of taking two antifolate drugs with a common mechanism of action (reviewed in Peters et al. 2007). Two trials evaluated MQ as IPTp in women taking cotrimoxazole (Gonzalez et al. 2014b;). In a multicenter study conducted in East and Southeast Africa, peripheral and placental parasitemia (defined by BS, PCR, or histology) and nonobstetric admission were less frequent among women that received three doses of IPTp-MQ, while maternal anemia, birth weight, and gestational age at delivery were similar between groups (Gonzalez et al. 2014b). Notably, IPTp-MQ was associated with increased mother-to-child transmission of HIV, and again showed poor tolerability (Gonzalez et al. 2014b). In West Africa, IPTp with three MQ doses (15 mg/kg) was compared with cotrimoxazole alone and cotrimoxazole plus IPTp-MQ (Denoeud-Ndam et al. 2014). At delivery, PM was not detected by PCR in any of the 105 women in the cotrimoxazole + IPTp-MQ group compared with 5/103 women in the cotrimoxazole alone group. Maternal anemia, infection rate during pregnancy detected by PCR, and birth weight did not differ between groups. Again, adverse events were more common among women receiving MQ (Denoeud-Ndam et al. 2014). Although MQ can be effective to reduce infection, tolerability has been poor even when used at a split dose, and thus may result in low compliance if used for prevention.

Chloroquine–Azithromycin Combination

The CQ–azithromycin combination was compared with SP for use as IPTp in a trial that included six sites in Africa. However, interim analyses showed that the new combination was not superior to the existing intervention, and the study was terminated early (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01103063).

Intermittent Screening and Treatment

The Intermittent Screening and Treatment in pregnancy (ISTp) strategy entails screening women for malaria infection during antenatal clinic visits using an RDT and treating infection with an antimalarial drug. A multicenter trial comparing ISTp-AL (artemether–lumefantrine) with IPTp-SP was recently conducted in West Africa in sites with seasonal malaria and low SP resistance (Tagbor et al. 2015). PM, birth weight, and maternal hemoglobin were similar between ISTp-AL and IPTp-SP in the overall analysis and within individual sites (Tagbor et al. 2015). Malaria infections between scheduled visits were significantly more frequent in women randomized to the ISTp-AL (Tagbor et al. 2015). In an area of high malaria transmission and high SP resistance in Kenya, women were randomized to three interventions: ISTp with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine (DP), IPTp with DP, and IPTp-SP (Desai et al. 2015). Malaria infection at delivery was diagnosed by detection of parasites with BS on peripheral or placental blood, or with RDT or PCR on peripheral blood. Risks of malaria infection, mild anemia (HGB < 11 g/dL), stillbirth, and early infant mortality were significantly reduced in women receiving IPTp-DP rather than IPTp-SP or ISTp-DP, while ISTp-DP and IPTp-SP groups did not differ (Desai et al. 2015). The failure of ISTp-DP to improve on IPTp with the failing drug SP echoes the early evaluation of IPTp-SP in 1992–1994 (Parise et al. 1998) in which case management was inferior to IPTp-SP.

Differences in ISTp efficacy between the two studies could result from different transmission patterns, being highly seasonal in West Africa versus perennial with seasonal peaks in Kenya. Peripheral parasite density at delivery in Kenya was much lower than the density at enrollment in West Africa. Although the different assessment times could influence BS results, lower parasite densities might explain the lower sensitivity of RDT to detect PM, potentially rendering the IST strategy ineffective in Kenya (Fried et al. 2012; Desai et al. 2015).

Treatment of Malaria during Pregnancy

Currently, artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) is the first-line treatment for malaria in nonpregnant individuals. Owing to safety concerns, WHO recommends that pregnant women be treated with quinine and clindamycin during the first trimester and with ACT in the second and third trimesters. A multicenter trial reported high cure rate with four different ACTs (artemether–lumefantrine, amodiaquine–artesunate, dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine, and mefloquine–artesunate), with artemether–lumefantrine showing the lowest cure rate of 94.8% (The PREGACT Study Group 2016). Pregnancy outcomes were similar between the four groups and both artemether–lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine had fewer adverse events than amodiaquine–artesunate, and mefloquine–artesunate (The PREGACT Study Group 2016). Analyses of first-trimester antimalarial treatment records at Shoklo Malaria Research Unit in Thailand have shown that artesunate is as safe as choloroquine and quinine (McGready et al. 2012). In a similar study in Kenya, ACT treatment during the first-trimester (based on the review of treatment records) did not increase the risk of miscarriage, compared with women who did not receive any treatment or women who received quinine (Dellicour et al. 2015). However, community surveillance, which included cases without a treatment record, suggested that exposure to ACT may increase the risk of miscarriage compared with women that never received antimalarial drugs (Dellicour et al. 2015). Because both symptomatic and asymptomatic malaria infections (with P. falciparum or P. vivax) during the first trimester increase the risk of miscarriage (McGready et al. 2012), it might be difficult to assess the contribution attributable to ACT when the comparison group includes never-infected women. Both studies had a small number of women that received either ACT or quinine, and clinical trials to compare the safety of ACT to quinine during the first trimester are needed.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Pregnant women are at increased risk of malaria, making this demographic group an important parasite reservoir in the community and a key target for interventions during elimination efforts (Fig. 1). However, pregnant women and women of childbearing age will require special considerations during any mass administration campaigns. Semi-immune women often carry P. falciparum PM with low peripheral parasite burdens and few acute symptoms, hindering diagnosis and complicating efforts to use targeted treatment as a strategy. Drugs currently used for malaria prevention during pregnancy have lost or are losing their efficacy, and finding new drugs is stymied by concerns for teratogenicity and embryotoxicity; dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine has shown promise as the monthly presumptive treatment to prevent poor pregnancy outcomes, although it may not reduce PM prevalence. Vaccines have been important tools for the elimination of other infectious pathogens, and women commonly receive vaccines such as tetanus toxoid during pregnancy. Vaccines could be particularly useful for the control of PM: P. falciparum parasites sequester in the human placenta by adhesion to CSA, and women acquire antibodies against CSA-binding parasites over successive pregnancies, rendering primigravidae most susceptible and suggesting a vaccine is feasible. Vaccines that control PM, prevent human infection, or block onward transmission to mosquitoes, will require testing to assess their ability to interrupt transmission through pregnant women. More effort must be made to address the safety of drugs, vaccines, and antivector measures among women of childbearing age, particularly during the first trimester of pregnancy when safety concerns are greatest.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Tens of millions of pregnant women are at risk of malaria every year, but the management of malaria is particularly complex in this population. In areas of low transmission, women lacking immunity are at increased risk of acute severe disease and of death during P. falciparum infection, and therefore active surveillance and prompt treatment of malaria in these women is paramount. In areas of high stable transmission, acquired immunity can mask acute symptoms but leave women vulnerable to insidious effects such as severe maternal anemia and perinatal, neonatal, or postneonatal death for their offspring. Existing diagnostic tools are inadequate to detect malaria infection in semi-immune women, and the drugs CQ and SP used as preventive interventions have lost or are losing their benefits; a replacement drug has yet to be identified that is sufficiently safe, tolerable, and effective as prevention, although studies of dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine are encouraging. Naturally acquired resistance to malaria suggests that vaccines are feasible by inducing antibodies against the CSA-binding parasites that sequester in the human placenta. Passive or active immunization that provides women with a window of coverage throughout pregnancy is an appealing alternative to drug prevention strategies. The need for new preventive and diagnostic tools for this vulnerable population is urgent, but is often overlooked by policymakers and funding agencies. This dearth of safe and effective tools to control malaria in pregnant women will hinder future malaria elimination campaigns, because any woman of childbearing age will likely be excluded from participation if pregnancy status is unknown.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge J. Patrick Gorres (Laboratory of Malaria Immunology and Vaccinology, National Institutes of Health [NIH]) for proofreading and editing this review, and Alan Hoofring (NIH Medical Arts, NIH) for preparing the illustration. M.F. and P.E.D. are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), NIH.

Footnotes

Editors: Dyann F. Wirth and Pedro L. Alonso

Additional Perspectives on Malaria: Biology in the Era of Eradication available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Abrams ET, Brown H, Chensue SW, Turner GD, Tadesse E, Lema VM, Molyneux ME, Rochford R, Meshnick SR, Rogerson SJ. 2003. Host response to malaria during pregnancy: Placental monocyte recruitment is associated with elevated β chemokine expression. J Immunol 170: 2759–2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achur RN, Valiyaveettil M, Alkhalil A, Ockenhouse CF, Gowda DC. 2000. Characterization of proteoglycans of human placenta and identification of unique chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans of the intervillous spaces that mediate the adherence of Plasmodium falciparum–infected erythrocytes to the placenta. J Biol Chem 275: 40344–40356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken EH, Mbewe B, Luntamo M, Maleta K, Kulmala T, Friso MJ, Fowkes FJ, Beeson JG, Ashorn P, Rogerson SJ. 2010. Antibodies to chondroitin sulfate A-binding infected erythrocytes: Dynamics and protection during pregnancy in women receiving intermittent preventive treatment. J Infect Dis 201: 1316–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhalil A, Achur RN, Valiyaveettil M, Ockenhouse CF, Gowda DC. 2000. Structural requirements for the adherence of Plasmodium falciparum–infected erythrocytes to chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans of human placenta. J Biol Chem 275: 40357–40364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews KT, Klatt N, Adams Y, Mischnick P, Schwartz-Albiez R. 2005. Inhibition of chondroitin-4-sulfate-specific adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum–infected erythrocytes by sulfated polysaccharides. Infect Immun 73: 4288–4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arinaitwe E, Ades V, Walakira A, Ninsiima B, Mugagga O, Patil TS, Schwartz A, Kamya MR, Nasr S, Chang M, et al. 2013. Intermittent preventive therapy with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for malaria in pregnancy: A cross-sectional study from Tororo, Uganda. PLoS ONE 8: e73073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataide R, Hasang W, Wilson DW, Beeson JG, Mwapasa V, Molyneux ME, Meshnick SR, Rogerson SJ. 2010. Using an improved phagocytosis assay to evaluate the effect of HIV on specific antibodies to pregnancy-associated malaria. PLoS ONE 5: e10807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataide R, Mwapasa V, Molyneux ME, Meshnick SR, Rogerson SJ. 2011. Antibodies that induce phagocytosis of malaria infected erythrocytes: Effect of HIV infection and correlation with clinical outcomes. PLoS ONE 6: e22491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awine T, Belko MM, Oduro AR, Oyakhirome S, Tagbor H, Chandramohan D, Milligan P, Cairns M, Greenwood B, Williams JE. 2016. The risk of malaria in Ghanaian infants born to women managed in pregnancy with intermittent screening and treatment for malaria or intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine. Malaria J 15: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babakhanyan A, Leke RG, Salanti A, Bobbili N, Gwanmesia P, Leke RJ, Quakyi IA, Chen JJ, Taylor DW. 2014. The antibody response of pregnant Cameroonian women to VAR2CSA ID1-ID2a, a small recombinant protein containing the CSA-binding site. PLoS ONE 9: e88173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardaji A, Sigauque B, Bruni L, Romagosa C, Sanz S, Mabunda S, Mandomando I, Aponte J, Sevene E, Alonso PL, et al. 2008. Clinical malaria in African pregnant women. Malaria J 7: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeson JG, Brown GV, Molyneux ME, Mhango C, Dzinjalamala F, Rogerson SJ. 1999. Plasmodium falciparum isolates from infected pregnant women and children are associated with distinct adhesive and antigenic properties. J Infect Dis 180: 464–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeson JG, Mann EJ, Elliott SR, Lema VM, Tadesse E, Molyneux ME, Brown GV, Rogerson SJ. 2004. Antibodies to variant surface antigens of Plasmodium falciparum–infected erythrocytes and adhesion inhibitory antibodies are associated with placental malaria and have overlapping and distinct targets. J Infect Dis 189: 540–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabin BJ. 1983. An analysis of malaria in pregnancy in Africa. Bull World Health Org 61: 1005–1016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Rempis E, Schnack A, Decker S, Rubaihayo J, Tumwesigye NM, Theuring S, Harms G, Busingye P, Mockenhaupt FP. 2015. Lack of effect of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy and intense drug resistance in western Uganda. Malaria J 14: 372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand V, Bottero J, Noel H, Masse V, Cordel H, Guerra J, Kossou H, Fayomi B, Ayemonna P, Fievet N, et al. 2009. Intermittent treatment for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in Benin: A randomized, open-label equivalence trial comparing sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine with mefloquine. J Infect Dis 200: 991–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brolin KJ, Persson KE, Wahlgren M, Rogerson SJ, Chen Q. 2010. Differential recognition of P. falciparum VAR2CSA domains by naturally acquired antibodies in pregnant women from a malaria endemic area. PLoS ONE 5: e9230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaisavaneeyakorn S, Moore JM, Mirel L, Othoro C, Otieno J, Chaiyaroj SC, Shi YP, Nahlen BL, Lal AA, Udhayakumar V. 2003. Levels of macrophage inflammatory protein 1 α (MIP-1 α) and MIP-1 β in intervillous blood plasma samples from women with placental malaria and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 10: 631–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisse M, Sangare I, Lougue G, Bamba S, Bayane D, Guiguemde RT. 2014. Prevalence and risk factors for Plasmodium falciparum malaria in pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Bobo-Dioulasso (Burkina Faso). BMC Infect Dis 14: 631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulibaly SO, Kayentao K, Taylor S, Guirou EA, Khairallah C, Guindo N, Djimde M, Bationo R, Soulama A, Dabira E, et al. 2014. Parasite clearance following treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment in Burkina-Faso and Mali: 42-day in vivo follow-up study. Malaria J 13: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechavanne S, Srivastava A, Gangnard S, Nunes-Silva S, Dechavanne C, Fievet N, Deloron P, Chene A, Gamain B. 2015. Parity-dependent recognition of DBL1X-3X suggests an important role of the VAR2CSA high-affinity CSA-binding region in the development of the humoral response against placental malaria. Infect Immun 83: 2466–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoeud-Ndam L, Zannou DM, Fourcade C, Taron-Brocard C, Porcher R, Atadokpede F, Komongui DG, Dossou-Gbete L, Afangnihoun A, Ndam NT, et al. 2014. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis versus mefloquine intermittent preventive treatment to prevent malaria in HIV-infected pregnant women: Two randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 65: 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellicour S, Tatem AJ, Guerra CA, Snow RW, ter Kuile FO. 2010. Quantifying the number of pregnancies at risk of malaria in 2007: A demographic study. PLoS Med 7: e1000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellicour S, Desai M, Aol G, Oneko M, Ouma P, Bigogo G, Burton DC, Breiman RF, Hamel MJ, Slutsker L, et al. 2015. Risks of miscarriage and inadvertent exposure to artemisinin derivatives in the first trimester of pregnancy: A prospective cohort study in western Kenya. Malaria J 14: 461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai M, Gutman J, L’Lanziva A, Otieno K, Juma E, Kariuki S, Ouma P, Were V, Laserson K, Katana A, et al. 2015. Intermittent screening and treatment or intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine versus intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the control of malaria during pregnancy in western Kenya: An open-label, three-group, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet 386: 2507–2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diakite OS, Kayentao K, Traore BT, Djimde A, Traore B, Diallo M, Ongoiba A, Doumtabe D, Doumbo S, Traore MS, et al. 2011. Superiority of 3 over 2 doses of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in mali: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 53: 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Kurtis JD, Pond-Tor S, Kabyemela E, Duffy PE, Fried M. 2012. CXC ligand 9 response to malaria during pregnancy is associated with low-birth-weight deliveries. Infect Immun 80: 3034–3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy PE. 2001. Immunity to malaria: Different host, different parasite. In Malaria in pregnancy: Deadly parasite, susceptible host (ed. Duffy PE, Fried M), pp. 71–127. Taylor & Francis, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy PE, Desowitz RS. 2001. Pregnancy malaria throughout history: Dangerous labors. In Malaria in pregnancy: Deadly parasite, susceptible host (ed. Duffy PE, Fried M), pp. 1–25. Taylor & Francis, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy PE, Fried M. 2003. Antibodies that inhibit Plasmodium falciparum adhesion to chondroitin sulfate A are associated with increased birth weight and the gestational age of newborns. Infect Immun 71: 6620–6623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy PE, Fried M. 2011. Pregnancy malaria: Cryptic disease, apparent solution. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 106: 64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman RT, Fidock DA. 2009. Artemisinin-based combination therapies: A vital tool in efforts to eliminate malaria. Nat Rev Microbiol 7: 864–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott SR, Brennan AK, Beeson JG, Tadesse E, Molyneux ME, Brown GV, Rogerson SJ. 2005. Placental malaria induces variant-specific antibodies of the cytophilic subtypes immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG3 that correlate with adhesion inhibitory activity. Infect Immun 73: 5903–5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G, Aitken E, Yosaatmadja F, Kalilani L, Meshnick SR, Jaworowski A, Simpson JA, Rogerson SJ. 2009. Antibodies to variant surface antigens of Plasmodium falciparum–infected erythrocytes are associated with protection from treatment failure and the development of anemia in pregnancy. J Infect Dis 200: 299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G, Simpson JA, Chaluluka E, Molyneux ME, Rogerson SJ. 2010. Decreasing burden of malaria in pregnancy in Malawian women and its relationship to use of intermittent preventive therapy or bed nets. PLoS ONE 5: e12012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fievet N, Ringwald P, Bickii J, Dubois B, Maubert B, Le Hesran JY, Cot M, Deloron P. 1996. Malaria cellular immune responses in neonates from Cameroon. Parasite Immunol 18: 483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fievet N, Le Hesran JY, Cottrell G, Doucoure S, Diouf I, Ndiaye JL, Bertin G, Gaye O, Sow S, Deloron P. 2006. Acquisition of antibodies to variant antigens on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum–infected erythrocytes during pregnancy. Infect Genet Evol 6: 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried M, Duffy PE. 1996. Adherence of Plasmodium falciparum to chondroitin sulfate A in the human placenta. Science 272: 1502–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried M, Nosten F, Brockman A, Brabin BJ, Duffy PE. 1998a. Maternal antibodies block malaria. Nature 395: 851–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried M, Muga RO, Misore AO, Duffy PE. 1998b. Malaria elicits type 1 cytokines in the human placenta: IFN-γ and TNF-α associated with pregnancy outcomes. J Immunol 160: 2523–2530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried M, Lauder RM, Duffy PE. 2000. Plasmodium falciparum: Adhesion of placental isolates modulated by the sulfation characteristics of the glycosaminoglycan receptor. Exp Parasitol 95: 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried M, Domingo GJ, Gowda CD, Mutabingwa TK, Duffy PE. 2006. Plasmodium falciparum: Chondroitin sulfate A is the major receptor for adhesion of parasitized erythrocytes in the placenta. Exp Parasitol 113: 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried M, Muehlenbachs A, Duffy PE. 2012. Diagnosing malaria in pregnancy: An update. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 10: 1177–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner P, Gulmezoglu AM. 2006. Drugs for preventing malaria in pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10.1002/14651858.CD000169.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnham PCC. 1938. The placenta in malaria with special reference to reticulo-endothelial immunity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 32: 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gies S, Coulibaly SO, Ky C, Ouattara FT, Brabin BJ, D’Alessandro U. 2009. Community-based promotional campaign to improve uptake of intermittent preventive antimalarial treatment in pregnancy in Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg 80: 460–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnidehou S, Jessen L, Gangnard S, Ermont C, Triqui C, Quiviger M, Guitard J, Lund O, Deloron P, Ndam NT. 2010. Insight into antigenic diversity of VAR2CSA-DBL5ɛ domain from multiple Plasmodium falciparum placental isolates. PLoS ONE 5: e13105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves BP, Huang CY, Morrison R, Holte S, Kabyemela E, Prevots DR, Fried M, Duffy PE. 2014. Parasite burden and severity of malaria in Tanzanian children. N Engl J Med 370: 1799–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R, Mombo-Ngoma G, Ouedraogo S, Kakolwa MA, Abdulla S, Accrombessi M, Aponte JJ, Akerey-Diop D, Basra A, Briand V, et al. 2014a. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy with mefloquine in HIV-negative women: A multicentre randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 11: e1001733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R, Desai M, Macete E, Ouma P, Kakolwa MA, Abdulla S, Aponte JJ, Bulo H, Kabanywanyi AM, Katana A, et al. 2014b. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy with mefloquine in HIV-infected women receiving cotrimoxazole prophylaxis: A multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med 11: e1001735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood BM, Greenwood AM, Snow RW, Byass P, Bennett S, Hatib-N’Jie AB. 1989. The effects of malaria chemoprophylaxis given by traditional birth attendants on the course and outcome of pregnancy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 83: 589–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood AM, Armstrong JR, Byass P, Snow RW, Greenwood BM. 1992. Malaria chemoprophylaxis, birth weight and child survival. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 86: 483–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman J, Mwandama D, Wiegand RE, Ali D, Mathanga DP, Skarbinski J. 2013. Effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine during pregnancy on maternal and birth outcomes in Machinga district, Malawi. J Infect Dis 208: 907–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman J, Kalilani L, Taylor S, Zhou Z, Wiegand RE, Thwai KL, Mwandama D, Khairallah C, Madanitsa M, Chaluluka E, et al. 2015. The A581G mutation in the gene encoding Plasmodium falciparum dihydropteroate synthetase reduces the effectiveness of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine preventive therapy in Malawian pregnant women. J Infect Dis 211: 1997–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington WE, Mutabingwa TK, Muehlenbachs A, Sorensen B, Bolla MC, Fried M, Duffy PE. 2009. Competitive facilitation of drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites in pregnant women who receive preventive treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 9027–9032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommerich L, von Oertzen C, Bedu-Addo G, Holmberg V, Acquah PA, Eggelte TA, Bienzle U, Mockenhaupt FP. 2007. Decline of placental malaria in southern Ghana after the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy. Malaria J 6: 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail MR, Ordi J, Menendez C, Ventura PJ, Aponte JJ, Kahigwa E, Hirt R, Cardesa A, Alonso PL. 2000. Placental pathology in malaria: A histological, immunohistochemical, and quantitative study. Hum Pathol 31: 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworowski A, Fernandes LA, Yosaatmadja F, Feng G, Mwapasa V, Molyneux ME, Meshnick SR, Lewis J, Rogerson SJ. 2009. Relationship between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coinfection, anemia, and levels and function of antibodies to variant surface antigens in pregnancy-associated malaria. Clin Vaccine Immunol 16: 312–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabyemela ER, Fried M, Kurtis JD, Mutabingwa TK, Duffy PE. 2008. Fetal responses during placental malaria modify the risk of low birth weight. Infect Immun 76: 1527–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabyemela E, Goncalves BP, Prevots DR, Morrison R, Harrington W, Gwamaka M, Kurtis JD, Fried M, Duffy PE. 2013. Cytokine profiles at birth predict malaria severity during infancy. PLoS ONE 8: e77214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuru A, Jagannathan P, Muhindo MK, Natureeba P, Awori P, Nakalembe M, Opira B, Olwoch P, Ategeka J, Nayebare P, et al. 2016. Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine for the prevention of malaria in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 374: 928–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattenberg JH, Tahita CM, Versteeg IA, Tinto H, Traore-Coulibaly M, Schallig HD, Mens PF. 2012. Antigen persistence of rapid diagnostic tests in pregnant women in Nanoro, Burkina Faso, and the implications for the diagnosis of malaria in pregnancy. Trop Med Int Health 17: 550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen J, Serghides L, Ayi K, Patel SN, Ayisi J, van Eijk A, Steketee R, Udhayakumar V, Kain KC. 2007. HIV impairs opsonic phagocytic clearance of pregnancy-associated malaria parasites. PLoS Med 4: e181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CL, Malhotra I, Wamachi A, Kioko J, Mungai P, Wahab SA, Koech D, Zimmerman P, Ouma J, Kazura JW. 2002. Acquired immune responses to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 in the human fetus. J Immunol 168: 356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]