Abstract

Rationale

Atherosclerotic-arterial occlusions decrease tissue perfusion causing ischemia to lower limbs in patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Ischemia in muscle induces an angiogenic response but the magnitude of this response is frequently inadequate to meet tissue perfusion requirements. Alternate splicing in the exon-8 of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A results in production of pro-angiogenic VEGFxxxa isoforms (VEGF165a, 165 for the 165 amino acid product) and anti-angiogenic VEGFxxxb (VEGF165b) isoforms.

Objective

The anti-angiogenic VEGFxxxb isoforms are thought to antagonize VEGFxxxa isoforms and decrease activation of VEGF-Receptor-2 (VEGFR2), hereunto considered the dominant receptor in post-natal angiogenesis in PAD. Our data will show that VEGF165b inhibits VEGFR1-Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT)-3 signaling to decrease angiogenesis in human and experimental PAD.

Methods and Results

In human PAD vs. control muscle-biopsies, VEGF165b: a) is elevated, b) is bound higher (vs. VEGF165a) to VEGFR1 not VEGFR2, and c) levels correlated with decreased VEGFR1, not VEGFR2, activation. In experimental PAD, delivery of an isoform specific monoclonal antibody (Ab) to VEGF165b vs. control-Ab enhanced perfusion in animal model of severe PAD (Balb/c strain) without activating VEGFR2-signaling but with increased VEGFR1-activation. Receptor pull-down experiments demonstrate that VEGF165b-inhibition vs. control increased VEGFR1-STAT3 binding and STAT3-activation, independent of janus activated kinase (Jak1)/Jak2. Using VEGFR1+/− mice that could not increase VEGFR1 after ischemia, we confirm that VEGF165b decreases VEGFR1-STAT3 signaling to decrease perfusion.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that VEGF165b prevents activation of VEGFR1-STAT3 signaling by VEGF165a and hence inhibits angiogenesis and perfusion recovery in PAD muscle.

Subject Terms: Angiogenesis, Animal Models of Human Disease, Basic Science Research, Cell Signaling/Signal Transduction, Vascular Biology

Keywords: Anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoform, VEGFR2, Ischemia, peripheral artery disease, angiogenesis, alternative splicing

INTRODUCTION

PAD is a complication of systemic atherosclerosis that affects more than 10 million people in US alone, where occlusions reduce perfusion to the leg(s) causing pain with walking, pain at rest, and ischemic ulcers that put the limb at risk for amputation(1,2). Surgical and catheter based revascularization therapies are preferred first line of treatment for patients with the most extreme form of PAD, but many patients are poor candidates or have no revascularization option(1,2). Thus, ~200,000 amputations/year occur in US alone with PAD being the major cause and no medical therapies are available to increase leg perfusion(3). In symptomatic PAD patients, a total occlusion in the inflow vessels means that resting or maximal leg blood flow is dependent on the extent of the angiogenic response to ischemia(4).

Vascular endothelial growth factor-a (VEGF-A) is a key member in the VEGF super family that can bind and activate vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)1 and VEGFR2, to modulate physiological and pathological angiogenesis(5). VEGF-A mediated VEGFR2-signaling activation is largely viewed as the dominant receptor tyrosine kinase signaling to induce angiogenesis(6,7). VEGFR1 plays important roles in several cardiovascular diseases including experimental PAD(8,9,10), however, the processes that regulate VEGFR1-activation or VEGFR1 specific downstream signaling events are not clear.

Human clinical trials aimed at inducing VEGF-A mediated VEGFR2-signaling in PAD via VEGF-A delivery to ischemic muscle were not successful(11,12,13). A number of factors may have contributed for this lack of beneficial effect, but it is clear that induction of functional blood vessel formation in ischemic muscle is a formidable challenge and an inadequate understanding of VEGF-VEGFR signaling is one major possible explanation. Our understanding of the VEGF ligands has become more complex with the recognition of anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms family, termed VEGFxxxb (VEGF165b), which occurs from alternate splicing in exon-8 of VEGF-A (a 6 amino-acid frame shift from CDKPRR (pro-angiogenic) to PLTGKD (anti-angiogenic))(14,15). Replacement of positively charged arginine residues in pro-angiogenic isoforms with neutral aspartic acid and lysine in anti-angiogenic isoforms is predicted to decrease VEGFR2-activation(16) and angiogenesis. Based on the existing paradigm on VEGF165b-VEGFR2 interactions, it was predicted that VEGF165b-inhibition would increase the bioavailability of pro-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms to VEGFR2 for receptor mediated angiogenesis. However, our data will show that VEGF165b modulates VEGFR1 and a novel VEGFR1-STAT3 signaling pathway that promotes angiogenesis and perfusion recovery in PAD.

METHODS

Please see the Online Supplement-Materials and Methods

RESULTS

In human and experimental PAD muscle, VEGF165b induction occurs with ischemia and is associated with lower VEGFR1, not VEGFR2 activation

In a previous study of gastrocnemius skeletal muscle from PAD and non-PAD control subjects (age and gender matched), we reported that VEGF165b was higher in PAD muscle using an ELISA(14). Kikuchi et al(17) more recently showed that peripheral blood monocytes from PAD vs. control patients express significantly higher VEGF165b by immunoblotting(17). We first confirmed that VEGF-A antibody, raised against full length VEGF-A protein, detects both pro-(VEGF165a) and anti-(VEGF165b) angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms and an isoform specific VEGFxxxb antibody raised against the 6 amino acids of exon8b in VEGFxxxb isoforms is extremely specific to recombinant-VEGF165b and does not detect recombinant-VEGF165a (Online Figure I-A) which was in accordance to previous publications(18,15). In cell free ELISA, while VEGF-A was able to detect both recombinant-VEGF165a and VEGF165b isoforms (at equal concentrations) with similar affinity, VEGF165b-Ab was not able to detect recombinant-VEGF165a even at 20x higher concentration than VEGF165b (data not shown) indicating that VEGF165b-Ab is highly specific for VEGFxxxb isoforms and hence was used to examine VEGF165b levels and function in our experiments.

We next quantified total VEGF-A and VEGF165b levels in PAD and normal muscle-biopsies by ELISA. In PAD muscle-biopsies, we observed a decrease in total VEGF-A levels (Normal: 166.3±27.8 vs. PAD:135.6±5.5 pg/mg, Fig-1A-left), with an increase in the VEGFxxxb fraction (Normal: 81.6±9.5 vs. PAD:98.1±12.7 pg/mg, Fig-1A-middle) compared to normal muscle-biopsies. Subtracting VEGFxxxb fraction from total VEGF-A showed that the VEGFxxxa fraction was significantly reduced (~2X, p=0.04) in PAD muscle-biopsies compared to normal (Normal: 84.7±21.6 vs. PAD:37.5±8.0 pg/mg, Fig-1A-right). We confirmed the specificity of our VEGF-A and VEGFxxxb ELISA data from PAD and normal muscle-biopsies by immunoblot analysis of VEGF-A and VEGF165b. In immunoblot analysis, while no significant differences were observed in total VEGF-A levels between PAD and normal muscle-biopsies, VEGF165b levels were significantly induced (p<0.03) in PAD muscle-biopsies compared to normal (Online Figure I-B). Since VEGF165b antibody detects only VEGF165b and the VEGF-A antibody detects both pro- and anti-angiogenic isoforms, we derived a ratio of VEGF165b:VEGF-A which showed that VEGF165b is induced ~3X in PAD muscle vs. normal (Online Figure I-B) indicating that in human PAD muscle, total VEGF-A includes ~75% VEGF165b fraction and ~25% VEGF165a fraction. The ability of VEGF165b ELISA to detect other VEGFxxxb isoforms(19) including VEGF165b offers one of the possible explanations for differences in VEGF165b levels in our ELISA and immunoblot analysis. Based on our ELISA and immunoblot analysis, we conclude that in PAD muscle a tilt in the balance of pro-vs. anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms towards anti-angiogenic VEGF165b isoforms results in decreased angiogenesis.

Figure 1.

A) VEGF-A and VEGF165b ELISA in normal (NL) and PAD muscle-biopsies. Table on the right shows the pg/mg of total protein levels of VEGF-A, VEGF165b and VEGF165a in normal (n=5) and PAD (n=7) muscle-biopsies. B) VEGFR2 was immunoprecipitated from normal and PAD tissue biopsies and analyzed for bound total VEGF-A and VEGF165b by immunoblotting. C) VEGFR1 was immunoprecipitated from normal (n=6) and PAD (n=10) tissue biopsies and analyzed for bound VEGF-A and VEGF165b by immunoblotting. Unpaired T-test. Full-length western blot images are presented in online Figure XII.

Since VEGFR2 is the dominant pro-angiogenic receptor, we next examined the degree of VEGFR2-activation (Y1175) in human PAD vs. control. Replacement of Y1173/Y1175 residue with phenylalanine results in diminished endothelial cell development and embryonic death(20) similar to embryonic lethality in VEGFR2 global knockout mice(21) indicating a critical role of Y1175 in regulating VEGFR2 downstream signaling. Hence, we focused on examining the status of VEGFR2-Y1175 activation in our experiments. Immunoblot of the VEGFR2-immunoprecipitated fraction showed significantly higher VEGFR2-activation (Y1175) in the PAD muscle-biopsies vs. control (P=0.009, Fig-1B). To examine whether increased VEGFR2-phosphorylation correlates with changes in binding of VEGF-A and VEGF165b to VEGFR2, we used the same VEGFR2-immunoprecipitated samples from normal and PAD muscle-biopsies and analyzed for VEGF165b and total VEGF-A. Despite lower total VEGF-A (VEGF165a) and higher VEGF165b levels in PAD vs. normal muscle-biopsies, no significant differences in VEGF165b or total VEGF-A binding was observed in VEGFR2-immunoprecipitated complexes between PAD and normal muscle-biopsies (Fig-1B) suggesting that higher VEGF165b levels in PAD vs. normal do not inhibit VEGFR2-activation.

Using a similar strategy and the same cohort, we next examined the degree of VEGFR1-activation in human PAD vs. control. Immunoblot of VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated fraction showed significantly decreased VEGFR1-activation (Y1333) in PAD muscle-biopsies vs. normal (P=0.003, Fig-1C). To examine whether decreased VEGFR1-phosphorylation correlates with changes in binding of VEGF-A and VEGF165b to VEGFR1, we used the same VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated samples and analyzed for bound VEGF165b and total VEGF-A. VEGFR1 pull-down experiments from PAD and normal muscle-biopsies showed a significant increase in VEGF165b levels bound to VEGFR1 with no significant change in total VEGF-A in PAD muscle-biopsies compared to normal (p<0.03, Fig-1C). Thus, VEGFR1-activation inversely correlated with increased VEGF165b binding to VEGFR1.

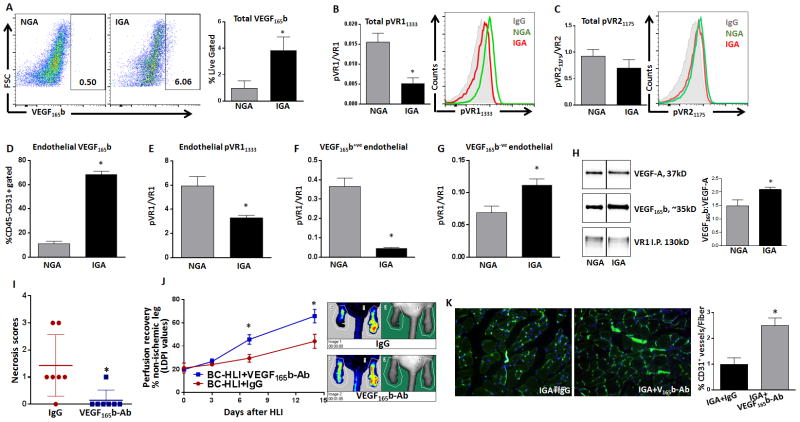

We then used unilateral femoral artery ligation and resection (hind limb ischemia, HLI) in Balb/c mice, as a pre-clinical experimental model for severe PAD (critical limb ischemia, CLI-PAD)(22,23,24,25,26). To determine whether VEGF165b induction correlates with decreased activation of VEGFR1 vs. VEGFR2 in ischemic muscle compared to non-ischemic we analyzed cells from non-ischemic and ischemic whole muscle tissue by flow cytometry (see Online Figure II for VEGF165b, pVEGFR1Y1333/VEGFR1, pVEGFR2Y1175/VEGFR2. We observed ~4X increase (p<0.05) in VEGF165b-expressing cells in ischemic gastrocnemius muscle, IGA (NGA-0.9±0.5 vs. IGA-3.8±1.0% of total live cells) compared to non-ischemic (NGA) (Fig-2A) and ~2X increase (p<0.05) in adductor muscle from ischemic leg (IAM) compared to non-ischemic leg (NAM) (NAM-4.3±2.1 vs. IAM-9.2±1.9%, Online Figure III-A). We also observed significantly lower VEGFR1-activation (determined as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of pVEGFR1Y1333/VEGFR1) in both IGA (~3X, P=0.01, Fig-2B) and IAM (~3X, P=0.007, Online Figure III-B) compared to non-ischemic but no difference in VEGFR2-activation (Fig-2C, Online Figure III-C).

Figure 2.

A) Flow cytometry of VEGF165b-expression in total live cells from NGA (non-ischemic gastrocnemius muscle) and IGA (ischemic gastrocnemius muscle), n=4. B) Flow cytometry of VEGFR1-activation (MFI of PVR1Y1333/VR1) in total live cells from NGA and IGA, n=4. C) Flow cytometry of VEGFR2-activation (MFI of PVR2Y1175/VR2) in total live cells from NGA and IGA, n=4. D) Flow cytometry of VEGF165b-expression in ECs (gated on CD31+CD45−-) from NGA and IGA, n=4. E) Flow cytometry of VEGFR1-activation in ECs (gated on CD31+CD45−) from NGA and IGA. n=4. F) Flow cytometry of VEGF165b-expressing ECs (CD31+CD45−VEGF165b+ve) with VEGFR1-activation, n=4. G) Flow cytometry of VEGF165b non-expressing ECs (CD31+CD45−VEGF165b−ve) with VEGFR1-activation, n=4. H) VEGFR1 was immunoprecipitated from NGA and IGA and examined for bound VEGF-A and VEGF165b by immunoblotting, n=4. Full-length western blot images are presented in online Figure XII. A–H) Unpaired T test. I) Necrosis scores. Necrosis was evaluated according to previously established necrosis scoring system ranging from 0–4 at day 1 and 3. Unpaired, non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. J) Perfusion recovery measured non-invasively by quantifying microvascular blood flow by laser Doppler. Repeated measures ANOVA with Dunnetts post-test. K) CD31 immunostaining in Balb/c IGA treated with VEGF165b-Ab (n=7) or IgG (n=5). Vascular density was calculated as CD31+ cells per muscle fiber. Unpaired T test.

We then correlated endothelial specific VEGF165b-expression with VEGFR1-activation in ischemic muscle. CD31+CD45− endothelial fraction had ~6X higher VEGF165b-expression in IGA (p<0.0001, NGA-10.9±2.1 vs. IGA-68.4±2.6%, (Fig-2D) and ~4X higher VEGF165b-expression in IAM compared to non-ischemic (p<0.05, NAM-2.2±0.4 vs. 9.2±1.9%, Online Figure III-D) and significantly lower VEGFR1-activation compared to non-ischemic (IGA~2X, P=0.01 (Fig-2E); IAM~2X, P=0.004 (Online Figure III-E)).

VEGF165b-expressing (VEGF165b+ve) ECs had significantly lower VEGFR1-activation in ischemic muscle (IGA~6X, P=0.0003 (Fig-2F); IAM~2X, P=0.01 (Online Figure III-F)) compared to non-ischemic. While ECs that do not express VEGF165b (VEGF165b−ve) showed significantly higher VEGFR1-phosphorylation in ischemic muscle (IGA~2X, p<0.03, (Fig-2G); IAM, p<0.03 (Online Figure III-G)) compared to non-ischemic. These data showed an inverse correlation between VEGF165b induction and VEGFR1-activation in experimental PAD.

In order to determine whether changes in VEGFR1-activation are due to the receptor bound VEGF165b in experimental PAD, we performed VEGFR1 pull-down experiments and immunoblotted for VEGF165b and VEGF-A. While there was no significant difference in total VEGF-A bound to VEGFR1 between NGA and IGA, we observed a significant increase in VEGF165b bound to VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated fractions (p<0.04, Fig-2H) in ischemic muscle compared to non-ischemic. These data demonstrated that with ischemia, there is increased production and binding of VEGF165b to VEGFR1 with decreased VEGFR1-activation in ischemic muscle compared to non-ischemic in experimental PAD.

We next examined the role of VEGF165b in modulating outcomes in experimental PAD by inhibiting VEGF165b in ischemic muscle. Consistent with the previous findings from Kikuchi et al(17), following HLI, intra-muscular injection of VEGF165b isoform-specific monoclonal antibody significantly decreased necrosis (p<0.03) and improved perfusion recovery at day-14 post-HLI (p<0.04, IgG-44.0±6.0 vs. VEGF165b-Ab-65.7±5.8, measured by non-invasively quantifying microvascular blood flow by laser Doppler) compared to IgG (Fig-2I, J). VEGF165b-Ab treatment showed a ~2.5X induction (P=0.004) in angiogenesis, evaluated by CD31+ immunostaining (% average of CD31+cells/muscle fiber) in ischemic muscle compared to IgG (Fig-2K).

VEGF165b-inhibition does not activate the classical pro-angiogenic VEGFR2-signaling but activates VEGFR1 to promote angiogenesis and perfusion recovery in ischemic muscle

Based on the well-established role of VEGFR2-signaling in angiogenesis, we first examined whether increased angiogenesis and perfusion post VEGF165b-inhibition is due to the activation of VEGFR2-signaling in ischemic muscle treated with VEGF165b-Ab compared to IgG. Immunoblotting of VEGFR2 and its key signaling intermediates(19,7) showed no significant differences in VEGFR2-activation (pVEGFR2Y1175/VEGFR2, Fig-3A) or activation of VEGFR2 downstream signaling including Akt, Erk or eNos (data not shown) in VEGF165b-Ab treated ischemic muscle compared to IgG suggesting that VEGF165b-inhibition did not activate VEGFR2-signaling in ischemic muscle.

Figure 3.

A) Immunoblot analysis of pVEGFR2Y1175 and VEGFR2. B) Immunoblot analysis of pVEGFR1Y1333 and VEGFR1 (immunoprecipitated fraction) in Balb/c IGA treated with VEGF165b-Ab (n=7) or IgG (n=5). C) Double immunofluorescence analysis of pVEGFR1 (Y1333) (AlexaFluor 555) and CD31 (AlexaFluor 488) pVEGFR1+ ECs in VEGF165b-Ab treated IGA. No negative staining was observed in sections stained with secondary antibody only. D) Flow cytometry of VEGFR1-activation in CD31+CD45− ECs from Balb/c IGA treated with VEGF165b-Ab vs. IgG, n≥5. E) Flow cytometry of VEGFR1-activation in HUVECs treated with VEGF165b-Ab or IgG (10μg/ml) for 24hrs, n=4. A, B, D, E) Unpaired T-test. Full-length western blot images are presented in online Figure XII.

Thus, we next examined the status of VEGFR1-activation post-VEGF165b inhibition in ischemic muscle. Immunoblotting showed that VEGF165b-Ab treatment significantly induced VEGFR1-activation by increasing Y1333 phosphorylation compared to IgG in ischemic muscle (~3X, Fig-3B). VEGFR1-activation in ischemic muscle ECs post-VEGF165b inhibition was confirmed visually by performing double immunofluorescence analysis for pVEGFR1Y1333(AlexaFluor555) and CD31(AlexaFluor488) (Fig-3C). The extent of endothelial specific VEGFR1-activation was quantified by flow cytometry in ischemic muscle treated with VEGF165b-Ab or IgG. Flow cytometry showed a significant increase in VEGFR1Y1333 activation in ischemic endothelium treated with VEGF165b-Ab compared to IgG (P=0.0003, Fig-3D).

We next examined whether VEGF165b-inhibition can induce endothelial specific VEGFR1-activation in vitro. Flow cytometry showed that VEGF165b-inhibition in HUVECs significantly induced VEGFR1-activation (P=0.0004) compared to IgG (Fig-3E) confirming our in vivo data. The specificity of VEGF165b-Ab was validated by treating HUVECs with VEGF165b-Ab pre-adsorbed with VEGF165b peptide (1:1) overnight at 4°C. Pre-adsorbed VEGF165b-Ab did not induce VEGFR1-activation confirming the specificity of VEGF165b-Ab (Online Figure IV). Our data demonstrating that VEGF165b-inhibition activates VEGFR1 but not VEGFR2 in ischemic muscle to induce a pro-angiogenic phenotype clearly suggest that VEGFR1-activation also plays a major role in modulating angiogenesis and perfusion recovery in experimental CLI-PAD.

To confirm that VEGFR1 plays a role in regulating angiogenesis post VEGF165b-inhibition, we first treated human endothelial cells (HUVECs) with recombinant VEGF165b ligand or VEGF165b-Ab under normal or HSS conditions. VEGF165b ligand treatment showed no significant difference in capillary tube formation on growth factor reduced matrigel, under normal or hypoxia serum starvation (HSS) conditions (Online Figure V-A, B). However, VEGF165b-inhibition significantly induced capillary like tube structures on growth factor reduced matrigel in HUVECs under normal (P=0.004, Online Figure V-A) and HSS (P=0.003, Online Figure V-B) conditions compared to IgG. To understand whether VEGF165b-Ab inhibits secreted or endogenous VEGF165b, conditioned media as well as cell lysates from normal and HSS HUVECs were examined for VEGF165b-expression/levels by ELISA and immunoblot analysis respectively. Immunoblot analysis of VEGF165b in normal and HSS-HUVECs showed that HUVECs express VEGF165b under normal conditions and the expression of VEGF165b is significantly induced in HSS-HUVECs (Online Figure V-C). However, we were not able to detect VEGF165b signal from HUVEC conditioned medium in VEGF165b ELISA (data not shown) indicating that the levels of VEGF165b in culture media are below the detection limit of the ELISA or VEGF165b in secreted form is bound to other carrier molecules resulting in its inability to be detected by conventional ELISA techniques. Hence, we think that VEGF165b-Ab inhibits not only endogenous VEGF165b but also secreted VEGF165b to induce endothelial angiogenesis.

Next, we transfected HUVECs with scrambled-SiRNA or VEGFR1-SiRNA with or without VEGF165b-inhibition under normal and HSS conditions and examined the ability of HUVECs to form capillary-like tubes on matrigel. VEGFR1 inhibition was confirmed by qPCR analysis of VEGFR1-expression (Online Figure V-D). A significant decrease in the number of capillary-like tubes was observed in HUVECs treated with VEGFR1-SiRNA compared to scrambled-SiRNA under normal (P=0.002, Online Figure V-E) as well as under HSS (P<0.0001, Online Figure V-F) conditions. VEGF165b-inhibition did not induce capillary-like tube formation on matrigel in HUVECs transfected with VEGFR1-SiRNA compared to scrambled-SiRNA indicating that VEGF165b regulates angiogenesis partly through modulating VEGFR1 in endothelial cells.

VEGF165b has been classically considered an anti-angiogenic ligand that functions by decreasing VEGFR2-activation. Limited literature describes the function of VEGF165b in modulating VEGFR1-signaling and function(27,28). Since, we observed VEGF165b-inhibition induces VEGFR1-activation but not VEGFR2-activation, we next wanted to examine whether VEGF165b delivery has differential effects on VEGFR1 vs. VEGFR2-activation in ECs. Thus, we treated HUVECs with recombinant VEGF165a and recombinant VEGF165b in time (5, 15 and 30min) and dose dependent (5, 25 and 50ng) conditions and examined for VEGFR1 and VEGFR2-activation (calculated as % MFI of baseline pVEGFR expression). We observed that VEGF165a significantly increased VEGFR1-activation at 5, 25 and 50ng concentration at 5, 15 and 30min compared to untreated HUVECs at 0min. VEGFR1-activation by VEGF165b was significantly lower than that of VEGF165a at 15 and 30min at all concentrations (P<0.05, Fig-4A). However, no significant difference in VEGFR2-activation was observed between VEGF165a and VEGF165b treatments at any concentration or time points (Fig-4C) indicating that VEGF165b can decrease VEGF-A mediated VEGFR1-activation.

Figure 4.

A, C) Flow cytometry of VEGFR1Y1333 and VEGFR2Y1175 phosphorylation in HUVECs, n=3. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used to test the significance between VEGF165a and VEGF165b treated samples at the same time points. B, D) Flow cytometry of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2-activation in HEK293-VR1 and HEK293-VR2 cells, n=3. Two-way ANOVA with Dunnetts multiple comparison test was used to test the significance between VEGF165a treated group at specific time point with other treatment groups at that specific time points. * indicates the time points that are significantly different from VEGF165a at that time point. E) Flow cytometry of VEGF165b levels in Balb/c NGA that received VEGF165b-expressing or scrambled plasmid 7-days post electroporation. F) Flow cytometry of VEGFR1Y1333 activation (normalized to VEGFR1) in Balb/c NGA treated with VEGF165b-expressing or scrambled plasmid. G) Flow cytometry of VEGFR2Y1175 activation in Balb/c NGA treated with VEGF165b-expressing or scrambled plasmid. E–G) n=4, Unpaired T-test.

To examine whether VEGF165b has the ability to block VEGF165a mediated VEGFR1 vs VEGFR2-activation we expressed VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 in HEK293 cells (HEK293-VR1 (Online Figure VI-A), HEK293-VR2 (Online Figure VI-B)) and treated them with VEGF165a, VEGF165b alone or in combination. Consistent with our findings in HUVECs (Fig-4A), we observed that while VEGF165a significantly induced VEGFR1-activation in HEK293-VR1 cells, the extent of VEGFR1-activation induced by VEGF165b was significantly lower (Fig-4B). Furthermore, a combination of VEGF165a and VEGF165b at varying concentrations revealed that VEGF165b even at 10X lower quantity has the ability to block VEGF165a mediated VEGFR1-activation compared to VEGF165a alone. Furthermore, similar to the data from HUVECs that showed VEGF165b activated VEGFR2 (Fig-4C), treatment of HEK293-VR2 cells with VEGF165b induced VEGFR2-activation albeit slightly lower than VEGF165a. Since, both ligands function as agonists to VEGFR2, combinations of VEGF165a and VEGF165b induced VEGFR2-activation equal to or higher than VEGF165a and VEGF165b individual treatments (Fig-4D). These data show that while VEGF165b functions as an agonist for VEGFR2, it is a competitive inhibitor for VEGF165a meditated VEGFR1-activation.

To obtain a direct correlation between VEGF165b and VEGFR1-activation in vivo, we next induced VEGF165b levels in Balb/c normal skeletal muscle in the hind limbs by electroporation and examined the extent of endothelial specific VEGFR1-activation by flow cytometry. We found that gastrocnemius muscle that received VEGF165b-expressing plasmid showed a significant increase in VEGF165b levels (P=0.003, Fig-4C) correlating with decreased endothelial (CD31+CD45−) VEGFR1-activation compared to gastrocnemius muscle that received scrambled plasmid (P<0.05, Fig-4D). However, no changes in endothelial specific VEGFR2-activation were observed in skeletal muscle that received VEGF165b-expressing plasmid compared to scrambled plasmid (Fig-4E). These data showed that increased VEGF165b levels could decrease VEGFR1-activation independent of the ischemic state of tissue.

While extensive data exist on VEGFR2-signaling in angiogenesis, information on VEGFR1-signaling is extremely sparse. Based on the previous reports demonstrating that ischemic myocardium from VEGFR1+/− mice had lesser STAT3 binding to DNA than VEGFR1+/+ mice(29) and that VEGFR1 associated with STAT3 in cancer models(30,31), we examined the status of STAT3-activation post-VEGF165b inhibition. Immunoblotting showed that VEGF165b-inhibition significantly induced STAT3-activation (~3X, p<0.05) in ischemic muscle compared to IgG (Fig-5A). CD31+CD45− ECs had significantly higher STAT3-activation in VEGF165b-Ab treated ischemic muscle (p=0.005, Fig-5B) compared to IgG. STAT3-activation also correlated with significantly decreased apoptosis (p<0.04, assayed by counting terminal deoxy uridine nick end labeled+ (TUNEL+) cells in at least 3 random images/section) and P53 inhibition (p<0.04, by immunoblotting)(9) in VEGF165b-Ab treated ischemic muscle vs. IgG (Online Figure VII-A,B). Since, Jak1/Jak2 are key kinases in STAT3-activation, we examined Jak1/Jak2 activation in VEGF165b-Ab vs. IgG treated ischemic muscle by immunoblotting. STAT3-activation post-VEGF165b inhibition occurred without Jak1/Jak2-activation (Online Figure VIII). We next wanted to confirm whether VEGF165b-inhibition induces STAT3-activation in ECs in vitro and correlates with VEGFR1-activation. Flow cytometry showed that VEGF165b-inhibition significantly induced STAT3-activation in HUVECs (~10X, MFI-pSTAT3/STAT3, P=0.0005, Fig-5C) compared to IgG.

Figure 5.

A) Immunoblot analysis of pSTAT3 and STAT3 in Balb/c IGA treated with VEGF165b-Ab (n=7) or IgG (n=5). B) Flow cytometry of endothelial specific (CD31+ CD45−) STAT3-activation (MFI-pSTAT3/STAT3) in Balb/c IGA treated with VEGF165b-Ab or IgG at day 3 post HLI, n=5/group. C) Flow cytometry of STAT3-activation in HUVECs treated with IgG or VEGF165b-Ab (10μg/ml for 24hrs), n=4. D) VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated complexes from VEGF165b-Ab (n=7) and IgG (n=5) treated IGA immunoblotted for bound VEGF-A and VEGF165b. E) VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated complexes from VEGF165b-Ab and IgG (n=3) treated HSS-HUVECs immunoblotted with VEGF-A and VEGF165b-Ab. F) VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated complexes from VEGF165b-Ab (n=7) or IgG (n=5) treated IGA samples immunoblotted for STAT3. G) VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated complexes from VEGF165b-Ab or IgG (n=3) treated HSS-HUVECs immunoblotted for STAT3. H) Double immunofluorescence analysis of pVEGFR1 (Y1333) (AlexaFluor 555) and pSTAT3 (AlexaFluor 488) in VEGF165b-Ab treated IGA. Arrows point towards the cells that are double positive for pVEGFR1 (Y1333) and pSTAT3. No negative staining was observed in sections stained with secondary antibody only. I) Flow cytometric analysis of pVEGFR1+pSTAT3+ ECs (CD31+ CD45−) in IGA treated with IgG or VEGF165b-Ab, n≥5/group. J) Immunoblot analysis of STAT3-activation in HEK293 cells transfected with negative plasmid (Neg Plmd) or VEGFR1-expressing plasmid (VR1-Plmd), n=4. K) Immunoblot analysis of STAT3-activation in VEGFR1 over-expressing HEK293 cells treated with IgG or VEGF165b (50ng/ml) for 30mins, n=4. L) Immunoblot analysis of STAT3-activation in HEK293 cells (VEGFR1 deficient) treated with IgG or VEGF165b-Ab (n=4, 10μg/ml for 24hrs). A–G, I–L) Unpaired T-test. Full-length western blot images are presented in online Figure XII.

VEGF165b-inhibition, in vivo, increases the bioavailability of VEGF-A to bind and activate VEGFR1 in ischemic muscle

In order to determine whether VEGFR1-STAT3 activation post-VEGF165b inhibition is due to increased binding of VEGF165a to VEGFR1, we performed VEGFR1 pull-down assays from VEGF165b-Ab and IgG treated ischemic muscle and assayed for bound VEGF165b and total VEGF-A. Immunoblotting showed that VEGFR1 immunoprecipitated complexes have significantly higher VEGF165a fraction (~3X, P=0.0002) in VEGF165b-Ab treated ischemic muscle compared to IgG (Fig-5D) indicating that VEGF165b-Ab treatment increased the binding of pro-angiogenic VEGF165a to VEGFR1 in ischemic muscle compared to IgG. In vitro, VEGFR1 was immunoprecipitated from HUVECs and immunoblotted for VEGF165b and total VEGF-A under normal and HSS conditions. VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated complexes from VEGF165b-Ab treated HUVECs showed significantly higher VEGF165a bound to VEGFR1 compared to IgG under normal (P=0.007, Online Figure IX-A) and HSS (P=0.002, Fig-5E) conditions. Increased VEGF165a binding over VEGF165b to VEGFR1 in vivo and in vitro correlates with enhanced VEGFR1 and STAT3-activation post-VEGF165b inhibition compared to IgG.

VEGF165b-inhibition induces VEGFR1-STAT3 interactions to promote STAT3-activation in ischemic muscle

As shown in Fig-3D and Online Figure IV, STAT3-activation post-VEGF165b inhibition occurred without changes in Jak1/Jak2-activation and a recent report showed that VEGFR1 is physically associated with STAT3 in cancer models(30,31). Hence, we sought to determine whether VEGFR1 could bind and activate STAT3 upon VEGF165b-inhibition. In vivo, VEGFR1 was immunoprecipitated from VEGF165b-Ab and IgG treated ischemic muscle samples and examined for physical interactions between VEGFR1 and STAT3. In VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated fractions, immunoblotting of STAT3 showed significantly higher STAT3 binding (~2X, p<0.03) post-VEGF165b inhibition vs. IgG (Fig-5F). In vitro, immunoblotting of VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated complexes from VEGF165b-Ab treated HUVECs showed no significant changes in endothelial-STAT3 binding compared to IgG treatment under normal conditions (Online Figure IX-B). However, VEGFR1-immunoprecipitated complexes from HSS-HUVECs (P=0.0002, Fig-5G) treated with VEGF165b-Ab showed a significant increase in STAT3 binding to VEGFR1 compared to IgG.

Activation of VEGFR1-STAT3 signaling in ischemic muscle post-VEGF165b inhibition was visually confirmed by double immunofluorescence analysis of pVEGFR1Y1333 (AlexaFluor-555) and pSTAT3 (AlexaFluor-488) which showed extensive co-localization of pVEGFR1 and pSTAT3 (Fig-5H). Flow cytometry of CD31+CD45− ECs showed that VEGF165b-inhibition induced a significant increase in the numbers of pVEGFR1+pSTAT3+ ECs (IgG-2.1±0.8 vs. VEGF165b-Ab-5.0±0.8%, p<0.02, Fig-5I) in ischemic muscle compared to IgG.

To confirm that VEGFR1 has the ability to activate STAT3, HEK293 cells (deficient in VEGFR1 and VEGFR2) were transfected with a VEGFR1 expressing plasmid (Online Figure X) and assayed for STAT3-activation. Immunoblotting showed that VEGFR1-expression in HEK293 significantly induced STAT3-activation (~3X, P=0.007) compared to control suggesting that VEGFR1 has the ability to activate STAT3 (Fig-5J). We next examined whether VEGF165b can inhibit STAT3-activation in HEK293-VR1 cells. Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that VEGF165b treatment significantly decreased (P<0.05) STAT3-activation in HEK293-VR1 cells compared to IgG treated HEK293-VR1 cells (Fig-5K). In non-transfected HEK293 cells, VEGF165b-inhibition did not significantly change STAT3-phosphorylation compared to IgG (Fig-5L) indicating that VEGFR1 can directly enhance STAT3-activation.

To understand the causal role of VEGFR1 in regulating STAT3-activation in ischemic muscle, we developed VEGFR1+/− mice on Balb/c background (VEGFR1−/− are embryonic lethal) which enabled us not only to understand the role of VEGFR1 in regulating STAT3-activation but also to further confirm the causal role of VEGFR1 in promoting perfusion recovery post-VEGF165b inhibition. Quantitative PCR and VEGFR1 immunofluorescence analysis showed that VEGFR1+/− mice have comparable VEGFR1 levels in normal skeletal muscle, but these mice cannot upregulate VEGFR1 in ischemic muscle compared to WT littermates (WT) (Fig-6A, B). These VEGFR1+/− HLI mice have significantly higher necrosis scores (p<0.05) and apoptosis (p<0.01, analyzed by TUNEL) vs. WT; and VEGF165b-Ab did not improve necrosis scores (Fig-6C) or apoptosis (Fig-6D) compared to IgG treatment in VEGFR1+/−HLI mice indicating that perfusion recovery post-VEGF165b inhibition is VEGFR1 dependent.

Figure 6.

A) VEGFR1-expression in VEGFR1+/− (VEGFR1+/−) mice. qPCR analysis of wild type littermates (WT) and VEGFR1+/− normal and ischemic muscle day-3 post HLI. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni select pair comparison. n=4/group. B) VEGFR1 immunofluorescence in VEGFR1+/− IGA and WT IGA. C) Necrosis scores at day-3 post HLI in WT+IgG-HLI (n=9), VEGFR1+/−+IgG-HLI (n=8) and VEGFR1+/−+VEGF165b-Ab-HLI mice (n=6). Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunnetts post-test. D) TUNEL Assay in WT+IgG-HLI (n=9), VEGFR1+/−+IgG-HLI (n=8) and VEGFR1+/−+VEGF165b-Ab-HLI IGA (n=6) day-3 post HLI. E) Immunoblot analysis of STAT3-activation in WT littermates (WT), VEGFR1+/− IGA treated with IgG or VEGFR1+/− IGA treated with VEGF165b-Ab. n=5. F) Flow cytometric analysis of STAT3-activation in WT littermates (WT), VEGFR1+/− IGA treated with IgG or VEGFR1+/− IGA treated with VEGF165b-Ab. n=4. G) Flow cytometric analysis of STAT3-activation in CD31+ CD45− ECs in WT littermates (WT), VEGFR1+/− IGA treated with IgG or VEGFR1+/− IGA treated with VEGF165b-Ab. n=4. D–G) One-Way ANOVA with Dunnetts post-test. Full-length western blot images for all the figures are presented in online Figure XII.

We next examined the status of STAT3-activation in VEGFR1+/− HLI mice IGA. Immunoblotting for STAT3-activation in VEGFR1+/− HLI mice showed a significant decrease in STAT3-activation (p<0.03) compared to WT in IGA (Fig-6E), and STAT3 was not activated by VEGF165b-inhibition in VEGFR1+/− HLI mice compared to IgG (Fig-6E). Furthermore, flow cytometry also demonstrated a significant decrease in total STAT3-activation (IGA~5X, p<0.04, Fig-6F; IAM~2X, p<0.04, Online Figure XI-A) in VEGFR1+/− IGA compared to WT. CD31+CD45− endothelial fraction showed a significant decrease in endothelial specific STAT3-activation (IGA~5X, p=0.01, Fig-6G; IAM~5X, p=0.03, Online Figure XI-B) in VEGR1+/− IGA compared to WT. VEGF165b-inhibition did not modulate STAT3-activation in VEGFR1+/− IGA. These data clearly indicated that VEGFR1 has the ability to regulate STAT3-activation in ischemic muscle.

DISCUSSION

Our knowledge of the VEGF superfamily continues to increase. While the totality of data to date have led to the conclusion that VEGF165b antagonizes VEGF165a to decrease VEGFR2-activation, our study demonstrates that VEGF165b does not inhibit VEGFR2 in endothelial cells and depletion/displacement of VEGF165b in ischemic muscle did not result in more VEGFR2-activation. Rather, we found an increased bioavailability of VEGF165a to bind and activate VEGFR1. Furthermore, VEGF165b-inhibition increased VEGFR1-STAT3 interactions to promote angiogenesis and enhance perfusion recovery. Our study demonstrates, for the first time, that VEGF165b inhibits VEGFR1-signaling in ischemic muscle and depletion of VEGF165b enhances an underappreciated ‘VEGFR1-activation’ to promote previously unknown ‘VEGFR1-STAT3 signaling’ in ischemic muscle and increases perfusion recovery.

While extensive literature exists on VEGFR2-signaling networks in PAD(7,32), information on VEGFR1-activation and downstream signaling events is sparse. Several of the VEGFR1 functions that have been identified are in non-ECs(33,34,35,36,37,38), and endothelial specific VEGFR1 functions remain uncertain. Our experimental data showed that VEGF165b-inhibition induces VEGFR1-activation not VEGFR2 or its downstream signaling in Balb/c ischemic muscle. Failure to upregulate VEGFR1 resulted in a loss of this effect. Our in vitro experiments with VEGF165a and VEGF165b ligand treatments in time and dose dependent manner showed that VEGF165b has the ability to induce VEGFR2Y1175 phosphorylation almost to a similar extent as VEGF165a in endothelial cells. However, while VEGF165a significantly induced VEGFR1Y1333 activation, VEGF165b failed to induce VEGFR1Y1333 activation in endothelial cells. Consistent with our in vitro experimental findings, VEGF165b delivery into non-ischemic muscle also decreased endothelial specific VEGFR1Y1333 activation but not VEGFR2Y1175.

Kawamura et al(16) has demonstrated that pulmonary arterial endothelial (PAE) cells that express VEGFR2 (PAE-VEGFR2) or VEGFR2-NRP1 (PAE-VEGFR2-NRP1) treated with VEGF165b show increased VEGFR2-activation (Y1052/Y1057) compared to untreated controls but not to the extent induced by VEGF165a(16). Another report by Catena et al(39) demonstrated that recombinant human VEGF165b-PP (produced in Pichia Pastoris) was able to induce VEGFR2Y1175 phosphorylation even more than that of VEGF165a and recombinant human VEGF165b-HS (produced in Chinese Hamster Ovarian cells) was able to induce VEGFR2Y1175 to the same extent as VEGF165a in HUVECs(39). In our current study, we show that VEGF165b functions as a blocker of VEGF165a mediated VEGFR1Y1333 activation (in HEK293-VR1 cells, Fig-4B) and VEGF165b induced VEGFR2Y1175 activation (in HEK293-VR2 cells, Fig-4D) almost to the same extent as VEGF165a. However, Kikuchi et al(17) (using HUVECs in vitro) and Ngo et al(40) (in ex vivo cultured visceral adipose tissue) have demonstrated that antibody medicated VEGF165b inhibition induced VEGFR2Y951 activation. Taken together these findings indicate that VEGF165b can differentially modulate site-specific phosphorylation on VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 and puts forward the requirement for an in depth analysis of the specific phosphorylation sites modulated by VEGF165b in VEGFR1 and VEGFR2.

While we show that VEGF165b decreases VEGFR1, but not VEGFR2 activation, elucidating the molecular mechanisms that regulate VEGF165b selective inhibitory effect towards VEGFR1 is important. Previous studies by Waltenberger et al(32) showed that the binding affinity of VEGF165a-VEGFR1 is Kd ~16pM and for VEGF165a-VEGFR2 is Kd ~760 pM indicating that VEGF165a binding affinity for VEGFR1 is several fold higher than its binding affinity for VEGFR2. Sawano et al(41) also reported similar findings that the binding affinity of VEGF165a to VEGFR1 is Kd 1 to 16 pM whereas for VEGFR2 it is Kd, 410 pM in porcine aortic endothelial (PAE) cells expressing VEGFR1 or VEGFR2. However, the extent of VEGFR1 auto-phosphorylation that follows ligand binding and receptor dimerization by VEGF165a is significantly weaker compared to VEGFR2(32). Since, the binding sites for VEGFR1 (in exon 3) and VEGR2 (in exon 4) are same in VEGF165a and VEGF165b isoforms(19), VEGF165b binding affinity to VEGFR1(42) and VEGFR2 is similar to VEGF165a(19,42). Our data from HEK293 cells with forced expression of either VEGFR1 or VEGFR2, and then treated with VEGF165a, VEGF165b or in combinations show that VEGF165b can block VEGF165a mediated VEGFR1 activation (not VEGFR2) even when present at 10X fold lower levels than VEGF165a. Based on these previously published reports(19,41,32) and our current data, we predict that the replacement of positively charged ‘arginine’ residues in VEGF165a isoforms with neutral ‘lysine and aspartic acid’ residues in VEGF165b isoforms results in an inhibitory effect towards VEGFR1 but not VEGFR2. In totality, VEGF165a and VEGF165b binding vs. activation of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 may not be straightforward. Further experiments at the protein structural changes and binding affinities are needed to get more defined information on the function of VEGF165b in regulating VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 activation at molecular level.

We, for the first time, show that activation of VEGFR1Y1333 is involved in STAT3-activation in ischemic muscle. However, interestingly, we observed that STAT3-activation occurred without any changes in key STAT3-activation kinases, Jak1/Jak2). Recent report by Lee et al(30) has shown that VEGFR1 is physically associated with STAT3 in cancer cells and another report by Zhao et al(31) has shown VEGF-A drives breast and lung cancer stem cells self-renewal by increasing VEGFR2/Jak/STAT3 interactions. VEGFR1 pull-down assays clearly showed that VEGF165b-inhibition can increase the binding of VEGFR1 to STAT3 resulting in increased STAT3-activation. We further confirmed that VEGFR1 has the ability to regulate STAT3-activation in VEGFR1+/− mice (on Balb/c background) in ischemic muscle. Our experiments conclude that VEGFR1 binding to STAT3 can increase STAT3-activation post-VEGF165b inhibition, indicating that a novel VEGFR1-STAT3 signaling is activated in ischemic muscle to promote perfusion recovery. However, the potential mechanisms that regulate VEGFR1-STAT3 interactions to induce STAT3-activation need to be further investigated. One possibility is that the kinase activity of VEGFR1 is responsible for STAT3-activation; and/or additional binding and adaptor molecules might also be involved in mediating VEGFR1-STAT3 interactions. STAT3 Activation can result in the induction of several STAT3 gene targets that have well documented functions(43,44) in inhibiting apoptosis and inducing angiogenesis to revascularize ischemic muscle. Our data do not exclude that VEGFR2-activation is important to promote angiogenesis in ischemic muscle in PAD rather demonstrate that VEGFR1-activation and the resulting STAT3-activation also play a key role in improving perfusion recovery(45).

Our study was largely, but not exclusively, based on data obtained from the use of antibody-mediated approach to inhibit VEGF165b. To confirm that the responses observed post VEGF165b-Ab treatment are specific, we performed several experiments that included 1) specificity of VEGF165b-Ab for VEGF165b isoform but not VEGF165a by immunoblot analysis (Online Figure I); 2) inability of VEGF165b-Ab pre-adsorbed to VEGF165b-lignad to activate VEGFR1 (Online Figure IV); and 3) VEGF165b-Ab decreases the binding of VEGF165b to VEGFR1 in vivo and in vitro vs. IgG control (Fig 5–D, E, Online Figure VIII-A). Separate from the antibody data, we also confirmed that VEGF165b-expressing plasmid delivery (gain of function) decreases VEGFR1-activation, which is consistent with increased VEGFR1-activation with VEGF165b-Ab treatment (loss of function). These data strongly suggest that the outcomes observed by VEGF165b-Ab are specific rather than non-specific events induced by antibody.

Conclusion

VEGFR2 is widely regarded as the dominant VEGF receptor in post-natal/ischemia mediated angiogenesis. However, our data in both mouse and human PAD showed an inverse correlation between VEGF165b binding to VEGFR1 and VEGFR1-activation and depletion of VEGF165b from ischemic muscle activates VEGFR1-STAT3 signaling to promote perfusion. Importantly, in addition to increased endothelial VEGFR1-STAT3 activation, increased VEGFR1-STAT3 activation in non-endothelial sources including monocyte/macrophages could also contribute for increased VEGFR1-STAT3 signaling ischemic muscle. Data from VEGFR1+/− PAD mice that are unable to upregulate VEGFR1 in ischemic muscle not only confirmed that VEGFR1 plays important role in perfusion but also that VEGF165b modulates VEGFR1 to decrease therapeutic angiogenesis and perfusion in PAD. Our data provide evidence to the theoretical hypothesis that removal of an angiogenesis inhibitor by monoclonal antibody approach may be a superior strategy than delivery of an angiogenic activator to treat ischemic cardiovascular diseases especially PAD.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Alternate splicing in exon-8 of VEGF-A gene produces 2 isoform families that are typically described as pro-angiogenic (C-terminus amino acid sequence CDKPRR) and anti-angiogenic (C-terminus amino acid sequence SLTRKD).

The anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms were predicted to inhibit pro-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms’ ability to activate VEGFR2

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Decreasing the anti-angiogenic VEGF-A levels increased VEGFR1 activation with no change in VEGFR2 activation in experimental PAD.

Increasing the anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoform decreased VEGFR1 activation and increased VEGFR2 activation.

Inhibition of anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms Increased VEGFR1-STAT3 binding interactions to enhance STAT3 activation that was independent of Jak1/Jak2 activation.

The anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms exist in human muscle but how these anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms modulate ischemic muscle recovery in PAD is not clear. In human and experimental-PAD, increased levels and binding of anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms to VEGFR1 correlated with decreased VEGFR1-activation. Inhibition of anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms in pre-clinical PAD models increased binding of pro-angiogenic VEGF-A to VEGFR1 to increase VEGFR1-STAT3 interactions and signaling resulting in enhanced ischemic muscle perfusion. VEGFR2 activation is necessary to revascularize ischemic muscle and the anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms were predicted to inhibit VEGFR2. Our work alters current thinking regarding VEGFR mediated angiogenesis by showing that anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms are inhibitors/blockers for VEGFR1 (not VEGFR2) and that removal of the inhibitor increased VEGFR1-activation to improve ischemic muscle perfusion. Our data provide the first evidence that strategies designed to inhibit the “anti-angiogenic” isoforms activate VEGFR1-STAT3 signaling. Furthermore, our finding that the anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms can inhibit pro-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms even at 10X lower levels may also explain the failure of prior human trials designed to increase the pro-angiogenic VEGF-A in ischemic muscle. Hence, therapies aimed at inhibiting anti-angiogenic VEGF-A isoforms may indeed provide a better strategy to promote perfusion in PAD through VEGFR1, not VEGFR2 activation.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

BHA is supported by 1R01 HL116455, 1R01 HL121635, and 2R01 HL101200 (B.H.A.). VCG thanks American Heart Association for scientist development grant 16SDG30340002

We thank Dr. John Lye for the technical assistance in preparing and expanding VEGF165b and VEGFR1 plasmids and maintaining VEGFR1+/− mice colony.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BC

Balb/c mic

- FSC

Forward scatter

- HEK293-VR1

VEGFR1 expressing HEK293 cells

- HEK293-VR2

VEGFR2 expressing HEK293 cell

- HLI

Hind limb ischemi

- HSS

Hypoxia serum starvation

- HUVEC

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial cells

- I.P

immunoprecipitation

- IAM

Non-ischemic adductor muscle

- IGA

Ischemic gastrocnemius muscle

- IgG

immunoglobulin

- MFI

Mean fluorescence intensity

- NAM

Non-ischemic adductor muscle

- NGA

Non-ischemic gastrocnemius muscle Nor

- NL

Normal

- PAD

Peripheral arterial disease

- Plmd

Plasmid

- rVEGF165a

recombinant Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor165a

- rVEGF165b

recombinant V Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor165b

- Scrbd

Scrambled

- TUNEL

Terminal Deoxy-Uridine Nick End labeling

- V165b-Ab

VEGF165b-Antibody

- VR1, VEGFR1

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor1

- VR2, VEGFR2

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor2

- WT

Wild type

- EC

Endothelial cells

- STAT3

Signal transductor and activator of transcription-A

- Jak

Janus associated kinases

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

VCG and BHA researched, designed, analyzed, discussed, wrote and reviewed the manuscript. VCG, MC and AK contributed to discussions and experimental work.

DISCLOSURES

Authors declare no conflict of interest. Part of this study was presented as an abstract (poster) in American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, Orlando, Florida, 7–11 November 2015.

References

- 1.Annex BH. Therapeutic angiogenesis for critical limb ischaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:387–396. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elsayed S, Clavijo LC. Critical Limb Ischemia. Cardiol Clin. 2015;33:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olin JW, Sealove BA. Peripheral artery disease: current insight into the disease and its diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:678–692. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu LH, Vijay CG, Annex BH, Bader JS, Popel AS. PADPIN: protein-protein interaction networks of angiogenesis, arteriogenesis, and inflammation in peripheral arterial disease. Physiol Genomics. 2015;47:331–343. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00125.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shibuya M. VEGF-VEGFR Signals in Health and Disease. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2014;22:1–9. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2013.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibuya M. Differential roles of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 and receptor-2 in angiogenesis. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;39:469–478. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2006.39.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsson AK, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:359–371. doi: 10.1038/nrm1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amano H, Kato S, Ito Y, Eshima K, Ogawa F, Takahashi R, Sekiguchi K, Tamaki H, Sakagami H, Shibuya M, Majima M. The Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-1 Signaling in the Recovery from Ischemia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishi J, Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Nojima A, Tateno K, Okada S, Orimo M, Moriya J, Fong GH, Sunagawa K, Shibuya M, Komuro I. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 regulates postnatal angiogenesis through inhibition of the excessive activation of Akt. Circ Res. 2008;103:261–268. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.174128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang KS, Lim JH, Kim TW, Kim MY, Kim Y, Chung S, Shin SJ, Choi BS, Kim HW, Kim YS, Chang YS, Kim HW, Park CW. Vascular endothelial growth factor-receptor 1 inhibition aggravates diabetic nephropathy through eNOS signaling pathway in db/db mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajagopalan S, Mohler ER, III, Lederman RJ, Mendelsohn FO, Saucedo JF, Goldman CK, Blebea J, Macko J, Kessler PD, Rasmussen HS, Annex BH. Regional angiogenesis with vascular endothelial growth factor in peripheral arterial disease: a phase II randomized, double-blind, controlled study of adenoviral delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor 121 in patients with disabling intermittent claudication. Circulation. 2003;108:1933–1938. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093398.16124.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajagopalan S, Mohler E, III, Lederman RJ, Saucedo J, Mendelsohn FO, Olin J, Blebea J, Goldman C, Trachtenberg JD, Pressler M, Rasmussen H, Annex BH, Hirsch AT. Regional Angiogenesis with Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) in peripheral arterial disease: Design of the RAVE trial. Am Heart J. 2003;145:1114–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen HS, Rasmussen CS, Macko J. VEGF gene therapy for coronary artery disease and peripheral vascular disease. Cardiovasc Radiat Med. 2002;3:114–117. doi: 10.1016/s1522-1865(02)00158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones WS, Duscha BD, Robbins JL, Duggan NN, Regensteiner JG, Kraus WE, Hiatt WR, Dokun AO, Annex BH. Alteration in angiogenic and anti-angiogenic forms of vascular endothelial growth factor-A in skeletal muscle of patients with intermittent claudication following exercise training. Vasc Med. 2012;17:94–100. doi: 10.1177/1358863X11436334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolard J, Wang WY, Bevan HS, Qiu Y, Morbidelli L, Pritchard-Jones RO, Cui TG, Sugiono M, Waine E, Perrin R, Foster R, Digby-Bell J, Shields JD, Whittles CE, Mushens RE, Gillatt DA, Ziche M, Harper SJ, Bates DO. VEGF165b, an inhibitory vascular endothelial growth factor splice variant: mechanism of action, in vivo effect on angiogenesis and endogenous protein expression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7822–7835. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamura H, Li X, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Claesson-Welsh L. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A165b is a weak in vitro agonist for VEGF receptor-2 due to lack of coreceptor binding and deficient regulation of kinase activity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4683–4692. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kikuchi R, Nakamura K, MacLauchlan S, Ngo DT, Shimizu I, Fuster JJ, Katanasaka Y, Yoshida S, Qiu Y, Yamaguchi TP, Matsushita T, Murohara T, Gokce N, Bates DO, Hamburg NM, Walsh K. An antiangiogenic isoform of VEGF-A contributes to impaired vascularization in peripheral artery disease. Nat Med. 2014;20:1464–1471. doi: 10.1038/nm.3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bates DO, Mavrou A, Qiu Y, Carter JG, Hamdollah-Zadeh M, Barratt S, Gammons MV, Millar AB, Salmon AH, Oltean S, Harper SJ. Detection of VEGF-A(xxx)b isoforms in human tissues. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harper SJ, Bates DO. VEGF-A splicing: the key to anti-angiogenic therapeutics? Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:880–887. doi: 10.1038/nrc2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakurai Y, Ohgimoto K, Kataoka Y, Yoshida N, Shibuya M. Essential role of Flk-1 (VEGF receptor 2) tyrosine residue 1173 in vasculogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1076–1081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404984102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shalaby F, Rossant J, Yamaguchi TP, Gertsenstein M, Wu XF, Breitman ML, Schuh AC. Failure of blood-island formation and vasculogenesis in Flk-1-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;376:62–66. doi: 10.1038/376062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalothorn D, Clayton JA, Zhang H, Pomp D, Faber JE. Collateral density, remodeling, and VEGF-A expression differ widely between mouse strains. Physiol Genomics. 2007;30:179–191. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00047.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalothorn D, Faber JE. Strain-dependent variation in collateral circulatory function in mouse hindlimb. Physiol Genomics. 2010;42:469–479. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00070.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dokun AO, Keum S, Hazarika S, Li Y, Lamonte GM, Wheeler F, Marchuk DA, Annex BH. A quantitative trait locus (LSq-1) on mouse chromosome 7 is linked to the absence of tissue loss after surgical hindlimb ischemia. Circulation. 2008;117:1207–1215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.736447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dokun AO, Chen L, Okutsu M, Farber CR, Hazarika S, Jones WS, Craig D, Marchuk DA, Lye RJ, Shah SH, Annex BH. ADAM12: A Genetic Modifier of Preclinical Peripheral Arterial Disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H790–803. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00803.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazarika S, Farber CR, Dokun AO, Pitsillides AN, Wang T, Lye RJ, Annex BH. MicroRNA-93 controls perfusion recovery after hindlimb ischemia by modulating expression of multiple genes in the cell cycle pathway. Circulation. 2013;127:1818–1828. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glass CA, Harper SJ, Bates DO. The anti-angiogenic VEGF isoform VEGF165b transiently increases hydraulic conductivity, probably through VEGF receptor 1 in vivo. J Physiol. 2006;572:243–257. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bills VL, Salmon AH, Harper SJ, Overton TG, Neal CR, Jeffery B, Soothill PW, Bates DO. Impaired vascular permeability regulation caused by the VEGF(1)(6)(5)b splice variant in pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2011;118:1253–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thirunavukkarasu M, Juhasz B, Zhan L, Menon VP, Tosaki A, Otani H, Maulik N. VEGFR1 (Flt-1+/−) gene knockout leads to the disruption of VEGF-mediated signaling through the nitric oxide/heme oxygenase pathway in ischemic preconditioned myocardium. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1487–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee YK, Shanafelt TD, Bone ND, Strege AK, Jelinek DF, Kay NE. VEGF receptors on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) B cells interact with STAT 1 and 3: implication for apoptosis resistance. Leukemia. 2005;19:513–523. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao D, Pan C, Sun J, Gilbert C, Drews-Elger K, Azzam DJ, Picon-Ruiz M, Kim M, Ullmer W, El-Ashry D, Creighton CJ, Slingerland JM. VEGF drives cancer-initiating stem cells through VEGFR-2/Stat3 signaling to upregulate Myc and Sox2. Oncogene. 2015;34:3107–3119. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waltenberger J, Claesson-Welsh L, Siegbahn A, Shibuya M, Heldin CH. Different signal transduction properties of KDR and Flt1, two receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26988–26995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selvaraj D, Gangadharan V, Michalski CW, Kurejova M, Stosser S, Srivastava K, Schweizerhof M, Waltenberger J, Ferrara N, Heppenstall P, Shibuya M, Augustin HG, Kuner R. A Functional Role for VEGFR1 Expressed in Peripheral Sensory Neurons in Cancer Pain. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:780–796. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fong GH, Zhang L, Bryce DM, Peng J. Increased hemangioblast commitment, not vascular disorganization, is the primary defect in flt-1 knock-out mice. Development. 1999;126:3015–3025. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.13.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.d’Audigier C, Gautier B, Yon A, Alili JM, Guerin CL, Evrard SM, Godier A, Haviari S, Reille-Serroussi M, Huguenot F, Dizier B, Inguimbert N, Borgel D, Bieche I, Boisson-Vidal C, Roncal C, Carmeliet P, Vidal M, Gaussem P, Smadja DM. Targeting VEGFR1 on endothelial progenitors modulates their differentiation potential. Angiogenesis. 2014;17:603–616. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muramatsu M, Yamamoto S, Osawa T, Shibuya M. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 signaling promotes mobilization of macrophage lineage cells from bone marrow and stimulates solid tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8211–8221. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beck H, Raab S, Copanaki E, Heil M, Scholz A, Shibuya M, Deller T, Machein M, Plate KH. VEGFR-1 signaling regulates the homing of bone marrow-derived cells in a mouse stroke model. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:168–175. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181c9c05b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohkubo H, Ito Y, Minamino T, Eshima K, Kojo K, Okizaki S, Hirata M, Shibuya M, Watanabe M, Majima M. VEGFR1-positive macrophages facilitate liver repair and sinusoidal reconstruction after hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Catena R, Larzabal L, Larrayoz M, Molina E, Hermida J, Agorreta J, Montes R, Pio R, Montuenga LM, Calvo A. VEGF121b and VEGF165b are weakly angiogenic isoforms of VEGF-A. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:320. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ngo DT, Farb MG, Kikuchi R, Karki S, Tiwari S, Bigornia SJ, Bates DO, LaValley MP, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Hess DT, Walsh K, Gokce N. Antiangiogenic actions of vascular endothelial growth factor-A165b, an inhibitory isoform of vascular endothelial growth factor-A, in human obesity. Circulation. 2014;130:1072–1080. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawano A, Takahashi T, Yamaguchi S, Aonuma M, Shibuya M. Flt-1 but not KDR/Flk-1 tyrosine kinase is a receptor for placenta growth factor, which is related to vascular endothelial growth factor. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hua J, Spee C, Kase S, Rennel ES, Magnussen AL, Qiu Y, Varey A, Dhayade S, Churchill AJ, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Hinton DR. Recombinant human VEGF165b inhibits experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4282–4288. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee SH, Lee KB, Lee JH, Kang S, Kim HG, Asahara T, Kwon SM. Selective Interference Targeting of Lnk in Umbilical Cord-Derived Late Endothelial Progenitor Cells Improves Vascular Repair, Following Hind Limb Ischemic Injury, via Regulation of JAK2/STAT3 Signaling. Stem Cells. 2015;33:1490–1500. doi: 10.1002/stem.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang T, Cunningham A, Dokun AO, Hazarika S, Houston K, Chen L, Lye RJ, Spolski R, Leonard WJ, Annex BH. Loss of interleukin-21 receptor activation in hypoxic endothelial cells impairs perfusion recovery after hindlimb ischemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1218–1225. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Babiak A, Schumm AM, Wangler C, Loukas M, Wu J, Dombrowski S, Matuschek C, Kotzerke J, Dehio C, Waltenberger J. Coordinated activation of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 is a potent arteriogenic stimulus leading to enhancement of regional perfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:789–795. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.