Abstract

Research on the intergenerational transmission of divorce should be expanded to incorporate disrupted nonmarital cohabitations. The current study (1) examined the transmission of union instability from parents to offspring using Waves I and IV of Add Health, (2) replaced the binary variables (divorced versus non-divorced) typically used in this literature with count variables (number of disrupted unions), (3) relied on independent sources for data on parents’ and offspring’s union disruptions to minimize same-source bias, (4) assessed the mediating role of 11 theoretically derived variables (many not previously considered in this literature), and (5) incorporated information on discord in intact parental unions. Parent and offspring union disruptions were positively linked, with each parental disruption associated with a 16% increase in the number of offspring disruptions, net of controls. The mediators collectively accounted for 44% of the estimated intergenerational effect. Parent discord in intact unions also was associated with more offspring disruptions.

Keywords: couple relationships, dissolution, divorce, intergenerational issues, young adults

Although family scholars have speculated that divorce “runs in families” since the 1930s (e.g., Burgess & Cottrell, 1939), the first empirical evidence for the intergenerational transmission of divorce (ITD) was not presented until the 1950s (Landis, 1955). Since then, 25 studies on this topic have been published, and almost all have shown that divorce is correlated across generations (e.g., Amato, 1996, Amato & DeBoer, 2001). Although most of these studies were conducted in the United States, the ITD also has been reported in Australia, Canada, England, and many continental European countries (Diekmann & Schmidheiny, 2013; D’Onofrio et al., 2007; Dronkers & Harkonen, 2008; Kiernan & Cherlin, 2010). We do not know whether the ITD exists in other parts of the world, but it appears to be a feature of most developed, western societies.

In 1987, Robert Merton published a classic article in which he discussed the importance of establishing the phenomenon (Merton, 1987). As he argued, scholars sometimes fail to establish that a phenomenon really exists before they attempt to explain it. In the present case, the ITD appears to be a real phenomenon—perhaps as well established as any finding in the social sciences. Debate exists about whether the ITD has become weaker in the United States in recent decades (Wolfinger, 1999, 2011; Li & Wu, 2008). But even if the ITD has diminished in strength, marital instability in the family of origin continues to be one of the most reliable predictors of adult divorce. What is less clear is why the ITD exists, whether it involves divorce or all forms of union instability, or even if intergenerational “transmission” occurs in a causal or merely descriptive sense.

The current paper extends previous work on the ITD in several ways. We argue that recent demographic trends have made it necessary to move beyond divorce and focus on union instability more generally. Following this approach, we present new estimates of the intergenerational transmission of union instability (ITUI) in early adulthood using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Contrary to most prior studies, we use independent sources for data on parent and offspring union instability. We also examine the role of variables derived from multiple theoretical frameworks in mediating the transmission of instability across generations. Finally, we consider the possibility that stable but troubled parent unions also might destabilize future offspring unions.

Explanations

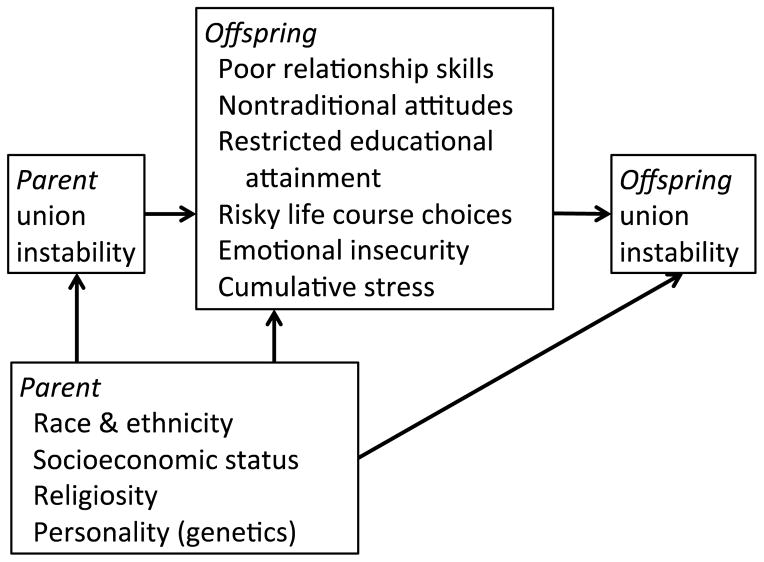

Although the ITD has been replicated frequently, it is less clear why union instability is correlated across generations. Figure 1 outlines several factors that may account for this phenomenon: poor relationships skills, nontraditional attitudes, risky life course choices, restricted educational attainment, emotional insecurity, and cumulative stress. Each of these terms represents a mediating process (or mechanism) through which parent union instability might affect offspring union instability. The figure also includes parent characteristics that may affect instability in both generations and, hence, result in a spurious association: race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religiosity, and personality (which we assume has a genetic component).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the intergenerational transmission of union instability.

Poor relationship skills

Social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) holds that children learn about partner relationships from observing their parents. When parents have happy and stable relationships, children have frequent opportunities to learn positive relationship skills, such as how to communicate clearly, resolve conflict amicably, and show emotional support. If parents with unhappy and unstable relationships do not model these skills, children have limited opportunities to learn them elsewhere. Consequently, many children from unstable families of origin reach adulthood without the skills necessary to achieve satisfying long-term unions. Although this explanation is compelling, it has proved difficult to test because few data sets contain the necessary variables. Consistent with this perspective, however, Amato (1996) found that adults with divorced parents reported an elevated number of problematic interpersonal behaviors in their marriages, such as being critical, getting angry easily, being jealous, having feelings that are hurt easily, not talking, and not being faithful. These problems, in turn, mediated a substantial proportion of the estimated effect of divorce in the family of origin on subsequent marital instability.

Nontraditional beliefs and attitudes

In addition to relationship skills, children form beliefs and attitudes about relationships from observing their parents. When parents have unstable unions, children may learn that most romantic relationships are temporary and that union disruptions are the rule rather than the exception. Children also may overhear divorced parents expressing favorable attitudes toward union disruption. Consistent with this idea, studies have shown that adults who experienced parental divorce while growing up tend to hold relatively nontraditional views about marriage and family life in general and positive attitudes toward divorce in particular (Axinn & Thornton, 1996). These views may have implications for relationship stability. For example, people who see relationships as transitory may not make the kinds of investments that strengthen unions over the long haul, and they may be quick to jettison troubled relationships. Indeed, two studies have shown that adults with divorced parents are especially likely to think about divorce when their marriages are unhappy (Amato & DeBoer, 2001; Webster, Orbuch, & House, 1995). If adults from unstable families of origin make fewer investments in their unions, and if they do not feel a strong commitment to maintain their unions through difficult times, then nontraditional beliefs and attitudes about relationships could be responsible for the transmission of instability across generations (in support of this idea, see Segrin, Taylor, & Altman, 2005).

Restricted educational attainment

Children with single parents tend to obtain less education than do children with continuously together parents (Lopoo & DeLeire, 2014; McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). This difference occurs partly because union disruptions lower children’s standard of living (McLanahan & Percheski, 2008). Parents with meager financial resources are unable to purchase educational goods for their children (such as books, computers, private lessons) and cannot support them through college. The disruption of parent unions also may expose children to high levels of conflict, interfere with the quality of parental support and supervision, and involve moving and changing schools—factors that can negatively affect children’s school performance. Economic insecurity associated with limited education in adulthood, in turn, increases the risk of union disruption for married as well as cohabiting individuals (Amato, 2000; Oppenheimer, 2003; Osborne, Manning, & Smock, 2007). These considerations suggest that limited status attainment may be the link that connects union instability across generations—a conclusion supported by three studies (Mueller & Pope, 1997; McLanahan & Bumpass, 1988; Feng, Giarrusso, Bengtson, & Frye, 1999).

Risky life course choices and transitions

Instability in the family of origin may increase the likelihood that youth make choices that place their unions at risk, such as dropping out of high school, forming unions at early ages, and having children prior to union formation (Amato, 1996; McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). They also may choose “risky” partners with poor economic prospects, a history of unstable relationships, children from previous relationships, or personality or substance abuse problems (Edin & Kefalas, 2005). These choices may result from problems that often accompany parent union instability, including a lack of parental supervision and guidance, conflict between parents or parent figures, and economic hardship (Amato, 2000; McLanahan & Percheski, 2008). Consistent with this perspective, several studies have shown that life course variables such as early age at marriage and having a premarital birth mediate part of the ITD (Amato, 1996; Mueller & Pope, 1977; Teachman, 2002; Kiernan & Cherlin, 2010; Feng, Giarrusso, Bengtson, & Frye, 1999; Diekmann & Engelhardt, 1999).

Attachment and emotional insecurity

Children need close and secure bonds with caregivers (usually parents) for healthy adjustment and development (Bowlby, 1982). When children perceive caregivers as unavailable and unresponsive, they may become emotionally insecure and form negative views of themselves, other people, and relationships. Emotional insecurity is linked with a variety of problems, including internalizing symptoms, externalizing behavior, poor academic achievement, and a pattern of early and frequent sexual relationships during adolescence (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Tracy, Shaver, Albino, & Cooper, 2003). Because attachment security (and insecurity) is relatively stable over the life course, it can strengthen (or undermine) the quality and stability of romantic relationships in adulthood (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). With respect to the ITD, parent union instability (along with discord between parents) can interfere with parental sensitivity and responsiveness (Amato & Booth, 1997) and increase emotional insecurity in children and youth (Brennan & Shaver, 1998; Cummings & Davies, 2010). Consequently, parent union instability, parental unresponsiveness, emotional insecurity in childhood, and union instability in adulthood all may all be linked. Although this explanation seems plausible, no studies to our knowledge have directly assessed this perspective.

Cumulative stress

Stress arises when an accumulation of environmental demands exceeds people’s ability to cope (Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullan, 1981). Parental union disruption initiates a series of events and circumstances that most children find to be stressful, including conflict between parents (both before and after separation), the departure of one biological parent from the household, strains in parent-child relationships, a decline in standard of living, changing residences and schools, and new parent unions and separations (Amato, 2000). Although some of these circumstances may be short-term (producing acute stress), others can persist for years (producing chronic stress). Stress leads to a heightened state of arousal and, over time, results in psychological and physiological “wear and tear.” Indeed, the emotional, behavioral, academic, and social problems seen among children from unstable families are often interpreted as reactions to the accumulation of acute and chronic stressors (Amato, 2000). To the extent that these problems persist into adulthood, they have the potential to undermine romantic relationships. Moreover, some youth may seek out sexual partners and form residential unions at early ages—unions that carry a high risk for disruption—to escape from stressful home environments (Amato & Kane, 2011). No studies to our knowledge, however, have assessed whether stress can account for the transmission of instability across generations.

Selection

All of the perspectives mentioned earlier assume that union instability is transmitted across generations in a causal sense. The selection perspective, however, reminds us that an intergenerational correlation will appear if certain parent characteristics increase the risk of instability in both generations. For example, if low socioeconomic status is a cause of union instability, and if socioeconomic status is transmitted from parents to children, then the intergenerational correlation in instability may be due entirely to socioeconomic status. (This possibility differs from the educational attainment perspective outlined earlier, which assumes that parent union instability lowers offspring attainment net of parent socioeconomic status.) A similar situation arises when certain racial or ethnic groups have especially rates of relationship instability. Similarly, if highly religious parents are less likely than other parents to voluntarily end their unions, and if they transmit their religious beliefs to their children, then religiosity also could be a confounding factor. Moreover, if parents with personality problems (like neuroticism or chronic depression) are especially likely to dissolve their unions, and if personality is transmitted across generations (perhaps through genetic inheritance), then personality could account for the intergenerational link in union instability. Note that these perspectives assume that something is transmitted across generations (socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, religiosity, personality), but parent union instability has no causal status net of these confounding factors.

Previous studies that have controlled for a variety of parent variables (including race, ethnicity, education, religiosity, age at first birth, antisocial behavior, psychological distress, and alcohol and drug use) suggest that part—but not all—of the ITD is due to selection (Amato, 1996; Amato & DeBoer, 2001; D’Onofrio et al., 2007; Teachman, 2002; Wolfinger, 1999). D’Onofrio et. al. (2007) used a genetically informed design (based on the children of twins) to study this topic. Their analysis indicated that about one third of the intergenerational transmission of divorce was due to genetic factors, and the remaining two thirds was due to environmental factors. In all of the studies that have seriously addressed selection, the ITD has continued to be statistically significant.

Contributions of the Current Study

The ITD has been well replicated, and the various theoretical perspectives reviewed earlier provide plausible explanations for why this phenomenon might occur. This research literature, however, is limited in two respects. The first involves the general focus on marriage. This focus is understandable, given that the first study on the ITD appeared in the 1950s. Today, however, marriage is declining, cohabitation has become the first union choice for the majority of young adults, and an increasing number of children are being born and raised within cohabiting unions. Moreover, cohabiting unions tend to be less stable than marriages, and children born to cohabiting parents have an elevated risk of experiencing family instability (Manning, Smock, & Majumdar, 2004). Because the ITD focuses on marriage and divorce, it misses many instances of union instability experienced by parents and offspring. Second, research on the ITD involves binary independent and dependent variables, that is, parent and offspring union status are typically coded 0 = continuously married, 1 = divorced. Many adults have multiple (sequential) co-residential unions, however, and children often experience multiple instances of household instability. Consequently, the independent and dependent variables in this research area may be better represented as count variables. In summary, a more complete picture requires (1) expanding the focus from divorce to the intergenerational transmission of union instability (ITUI), and (2) using count variables rather than binary variables to capture the full range of instability in people’s lives.

In an exception to most studies in this literature, Wolfinger (2000), found that multiple marital disruptions in the family of origin were linked with more frequent divorces among offspring in the National Survey of Families and Households. Instability in the family of origin, however, was not related to offspring’s reports of disrupted cohabiting unions (Wolfinger, 2005). We build on Wolfinger’s work by incorporating information on disrupted cohabitations among parents as well as offspring into our estimates of intergenerational transmission and using a more recent sample of young adult offspring.

The current study uses Add Health data (Harris et al., 2009) to estimate the effects of parent union instability on offspring union instability. Because the oldest youth in wave IV were in their early 30s, the data provide a picture of relationship instability in the early adult years—a time that is demographically dense with life course transitions. Our focus necessarily misses instances of union instability that occur later in the life course. But it is in the early adult years that the seeds of later union instability are sown, and events in this stage of life are of particular interest in helping us to understand the origin of this phenomenon.

We relied on parents’ reports of parent union instability (from Wave I) and offspring’s reports of offspring union instability (from Wave IV). Almost all prior studies of this topic have relied on offspring’s reports of their own and their parents’ divorces, which can produce a hypothesis-confirming bias if offspring with disrupted unions are more likely to recall and report union disruptions in the family of origin. Using different sources for the independent and dependent variables eliminates this source of bias. In estimating the strength of intergenerational transmission, we also controlled for variables that could affect instability in both generations and produce a spurious association, including race and ethnicity, parents’ education, family income, and parents’ religiosity. All of these variables were measured in Wave I, prior to first union formation for the great majority (98%) of youth in the sample.

We assessed the mediating role of multiple variables derived from the theoretical perspectives outlined earlier. A limitation of this effort, however, is that the perspectives overlap a great deal and, consequently, suggest identical mediators. For example, the restricted educational attainment perspective outlined earlier assumes that (1) parent union instability is negatively associated with young adults’ years of education, (2) years of education is negatively associated with union instability in adulthood, and (3) controlling for years of education reduces the association between parent and offspring union instability. But these hypotheses also are consistent with perspectives based on risky life course choices and transitions, attachment and emotional insecurity, and cumulative stress. Indeed, it is difficult (perhaps impossible) to find support for one perspective that does not simultaneously provide support for one or more of the other perspectives.

Given this concern, our theoretical goal was more modest, that is, to assess the mediating role of a variety of offspring variables suggested by theory, acknowledging that no definitive test of any single perspective is possible. Our mediators include emotional closeness to mothers and fathers, symptoms of depression, delinquency, school grades, being suspended or expelled from school, years of education, and the number of sexual partners—all variables suggested by the emotional insecurity and cumulative stress perspectives. Offspring level of education (along with school grades and being suspended) is, as noted earlier, also relevant to the educational attainment perspective. Following the life course perspective, we included age at first residential union and having a child prior to the first residential union (along with level of education). We also included a measure of nontraditional family attitudes, as suggested by the attitudinal perspective. Our goal was to see how much of the ITUI can be accounted for by these variables individually and collectively. Many of these variables, such as children’s delinquency and school grades, have not been examined previously in this literature.

We also conducted a supplementary analysis that incorporated information on parents’ relationship quality in stable unions. We did this partly because the data set contained no direct measures of offspring’s relationship skills—a key component of the perspective based on observational learning. This perspective suggests that offspring may fail to develop good relationship skills if their parents have discordant unions, even if these unions are stable (Amato & DeBoer, 2001). A focus on the modeling of relationship skills assumes that parent union discord and parent union instability have comparable problematic consequences for offspring—an idea we tested in the current study.

Methods

Sample

We relied on data from Waves I and IV of Add Health. When weighted, these data are nationally representative of adolescents in grades 7 through 12 in the United States during the 1994–1995 school year (Harris et al., 2009). A total of 20,745 adolescents participated in the in-home interview at Wave I. One parent of the focal adolescent also was interviewed—usually the mother. Our analytic sample was restricted to adolescents with valid sample weights who were living with a biological parent at Wave I. Because complete information on parent union disruptions was available only from parents in Wave I, we restricted the sample to adolescents who were at least 16 years old at this time. This restriction meant that we had complete information on parent union histories up to age 16 for all adolescents in the analytic sample. (We did not have information on additional disruptions experienced after the Wave I interviews—a limitation of the current study.) Given our focus on parent union instability, we also omitted a small number of adolescents (2%) who had lived continuously with a single parent from birth. This omission simplified the interpretation of who was in the “no disruptions” group, that is, adolescents who lived continuously with two biological or adoptive parents. These data restrictions resulted in a final sample of 7,765 youth.

The ages of youth in Wave I ranged from 16 to 21 with a mean of 17.5. The corresponding ages in Wave IV (collected in 2007–08) ranged from 28 to 35 with a mean of 30.3 About one half (49%) were women. With respect to race and ethnicity, 11% of the sample was Hispanic, 67% was non-Hispanic White, 15% was non-Hispanic Black, and 4% was Asian. The majority (87%) had formed a residential union of some type by Wave IV (69% had ever married and 58% had ever cohabited). The typical youth had 1.3 siblings. The great majority of interviewed parents (93%) were mothers with an average age of 44 in Wave I. Parent education ranged from 1 (not a high school graduate) to 4 (college graduate or higher) with a mean of 1.5. (Although this variable involved four ordered categories, we treated it as metric in the analysis; representing it as a series of dummy variables made no difference to the results but made the tables more complex.) Family income was based on parents’ reports of all family members in the household and ranged from $0 to $998,000 with a mean of $45,900. (All sample statistics here and elsewhere are weighted to be nationally representative.

With respect to attrition, 24% of all within-scope adolescents in Wave I did not complete interviews in Wave IV. Youth who dropped out of the panel tended to be older, male, non-white or Hispanic, have poorly educated parents, and live without both biological parents. Many of these Wave I characteristics also predicted union instability in early adulthood, as we show later. Offspring with unstable union histories also may have dropped out of the panel or been difficult to locate because they had personal problems or led disorganized lives. If these young adults are under-represented in Wave IV (which seems likely), then estimates of the intergenerational correlation in union instability will be attenuated in the current study—a point we return to in the discussion section.

Variables

Union instability

As part of the Wave I parent interview, parents were asked how many “marriages and marriage-like relationships” they had had during the last 18 years. Follow-up questions asked about the specific years during which parents were married to or lived with each of these partners. Up to six unions were recorded. We used this information to construct the number of union disruptions adolescents had experienced through the age of 16. We did not distinguish between marriages and cohabitations, nor did we distinguish between voluntary disruptions and disruptions due to death. The majority of parents (62%) reported no disruptions, 28% reported one disruption, 7% reported two disruptions, and 3% reported three or more disruptions. When parents had been continuously together from the child’s birth, almost all (98%) were married at the time of the Wave I interview.

The Wave 4 interview contained a series of questions about young adults’ current and previous marriages and non-marital cohabitations. Cohabitations were restricted to partners the respondent had lived for one month or more. We used these questions to calculate the number of offspring unions that had ended in disruption. Of all offspring who had ever married or cohabited, about half (54%) reported no disruptions (that is, their first unions were still intact), 27% reported one disruption, 11% reported two disruptions, and 8% reported three or more disruptions. (The maximum was 12.)

Control variable

Most of the control variables were derived from standard demographic questions in either the parent or adolescent interview. (See the earlier description of sample characteristics for information on these variables.) In addition to the demographic controls, parent religiosity was based on two items: (1) How often have you gone to religious services in the past year? (1 = never, 4 = once a week or more), and (2) How important is religion to you? (1 = not important at all, 4 = very important). The two items were added (range 2–8) to form a short scale of religiosity (Cronbach’s α = .75). The resulting score was standardized to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, with higher scores indicating greater religiosity.

Mediating variables

Closeness to mothers (fathers) scores were derived from five Wave 1 offspring interview items. Three items were scored 1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree: “Most of the time, your mother (father) is warm and loving toward you,” “You are satisfied with the way you and your mother (father) communicate with each other,” and “Overall, you are satisfied with the relationship you have with your mother (father).” Two other items were scored 1 = not at all, 5 = very much: “How close do you feel to your mother (father)?” “How much do you think she (he) cares about you?” Responses were scored in the direction of increasing closeness and added. Scale reliabilities (α) were .84 for mothers and .94 for fathers. The summary scores ranged from 5–25 and were standardized to have means of 0 and standard deviations of 1.

A measure of depressive symptoms involved 19 items from the Wave 1 offspring interview. Offspring were asked how often during the previous week they experienced certain feelings. Examples included: “You felt that you could not shake off the blues,” “You had trouble keeping your mind on what you are doing,” “You felt depressed,” “You felt life was not worth living,” and “You felt hopeful about the future.” Response options were 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = a lot of the time, and 3 = most or all of the time. Items were scored in the direction of negative affect and were averaged to create an overall score (α = .86). The scale was standardized to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

Delinquency was based on 15 items from the Wave 1 offspring interview. These items asked about the frequency of various antisocial behaviors in the past 12 months, such as painting graffiti on someone’s property or in a public place, deliberately damaging property that didn’t belong to you, taking something from a store without paying for it, hurting someone badly enough to need bandages or care from a doctor or nurse, and driving a car without its owner’s permission. Response options were 0 = never, 1 = 1 or 2 times, 2 = 3 or 4 times, and 3 = 5 or more times. The final score was an average of all items (α = .84) and was standardized to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

Suspensions and expulsions were created from two items from the Wave I offspring interview: “Have you ever been expelled from school?” and “Have you ever received an out of school suspension?” Responses were combined and scored 0 = never expelled or suspended, 1 = ever expelled or suspended. A measure of high school grades was derived from Wave I reports of recent grades in English/Language arts, mathematics, history or social studies, and science. A grade point average was calculated across the four subjects, and a Z score version served as the scale score (α = .75).

The number of sexual partners was based on the following Wave I item: “With how many people, in total, including romantic relationship partners, have you ever had a sexual relationship?” Responses ranged from 0 to 40 (or more) with a mean of 2.58. The response distribution was highly skewed, with the majority of youth (60%) reporting no sexual partners. In preliminary analyses, we used binary (0 versus 1 or more) and ordered versions of this variable. Because the results did not differ, we used the ordered version in the main analyses.

With respect to nontraditional attitudes, the Wave I interview schedule did not include items dealing with adolescents’ views about cohabitation, marriage, or divorce. It did, however, contain the following question: “Regardless of whether you have ever had a child, would you consider having a child in the future as an unmarried person?” A little more than one fourth of adolescents (27%) responded “yes.” Although less than ideal, we used this item as a proxy for holding nontraditional views about family life more generally.

Three variables were derived from the Wave IV interview with young adults. Educational attainment was an ordered scale ranging from 0 (8th grade or less) to 11 (completed a doctoral degree) with a mean of 5.6. Age at first union (in years) was derived from a series of questions asking about the respondent’s marriage and cohabitation history. This variable ranged from 14 to 33 with a mean of 23.7. Having a child before the first union was a binary variable (0 = no, 1 = yes) derived by comparing the ages at which respondents became parents with the ages at which they first cohabited or married. Of those who had formed residential unions, 22% were parents at the time.

Parent union discord

Parents in stable unions were asked three questions. “How would you rate your relationship with your spouse/partner? (1 = completely unhappy, 10 = completely happy). How much do you fight or argue with your spouse/partner? (1 = a lot, 4 = not at all). In the past year, have you and your spouse/partner talked to each other about separating? (0 = no, 1 = yes). These items were equally weighted and summed to produce a scale of union discord (α = .60). We then placed the top 21% of scores in a high parental discord category—a cutting point suggested by previous studies. For example, a taxonomic analysis by Beach, Fincham, Amir, and Leonard (2005) and a latent class analysis by Dush, Taylor, and Kroeger (2008) found that between 20% and 22% of married couples fell into a high discord category. Although we had information on discord from only one wave, previous research indicates that marital quality is highly stable over a decade or longer (Johnson, Amoloza, & Booth, 1992).

Analysis

The first analysis was restricted to youth (87% of the sample) who reported ever having cohabited or married by Wave IV. We restricted the sample because our dependent variable (the number of union disruptions) did not apply to people who had never formed unions. We relied on negative binomial regression for the analysis. Over-dispersion parameters consistently indicated that negative binomial regression was a better choice than Poisson regression for modeling these data. The statistical models included an exposure variable (Wave IV age) to adjust for the fact that the observation period for risk of union disruption varied across cases. (Older respondents had more time to form and dissolve unions.) We also measured exposure as Wave IV age minus age at first union, and the results were essentially identical.

The second analysis involved the full sample, including youth who had never cohabited or married. The dependent variable in this analysis involved four categories: (1) never formed a union, (2) still in an intact first union, (3) one union disruption, and (4) two or more union disruptions. We analyzed these data with multinomial regression with group two (still in an intact union) serving as the omitted category. We adjusted the standard errors in all analyses to account for weighting and the Add Health sampling design. To deal with missing data, we relied on multiple imputation with ICE (Imputation by Chained Equations) as implemented in Stata 12.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the bivariate association between union instability in the parent and offspring generations. Column 2 shows the percentage of offspring (who had ever married or cohabited) who reported a union disruption by Wave IV. Less than half (43%) of offspring who grew up in stable families had experienced a union disruption. This figure increased to 49%, 58%, and 63% among offspring who had experienced 1, 2, or 3+ parent union disruptions, respectively. The mean number of offspring union disruptions (Column 3) also increased monotonically. Consistent with previous research, these figures reveal that instability in the family of origin and in early adulthood are positively correlated. Moreover, multiple instances of parent instability (i.e., more than 1 disruption) were associated with higher levels of offspring instability than were single instances. Both of the bivariate associations shown in the table were statistically significant at p < .001.

Table 1.

Offspring union disruptions by number of parent union disruptions.

| Number of parent union disruptions | Offspring

|

|

|---|---|---|

| % Any disrupted union | Mean union disruptions | |

|

|

|

|

| 0 | 43 (1.13) | 0.70 (.03) |

| 1 | 49 (1.89) | 0.84 (.04) |

| 2 | 58 (3.31) | 1.06 (.08) |

| 3+ | 63 (5.96) | 1.19 (.18) |

Note: Sample size is 6,784. Data are from Add Health and are weighted to be nationally representative. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

Table 2 shows the negative binomial regression of offspring union disruptions on parent union disruptions. Model 1 reveals the bivariate association (b = .17, p < .001). Exponentiating the b coefficient (eb) produced an incident risk ratio of 1.19. This value indicates that each increase in the number of parent disruptions was associated with a 19% increase in the count of offspring disruptions. Adding the control variables in Model 2 reduced the b coefficient to .15 (p < .001). This result indicates that part of the bivariate association was spurious, at least with respect to the control variables in our model. The corresponding incident risk ratio (1.16) suggests that each disruption in the family of origin increased offspring disruptions by 16%. Four control variables were significant predictors of offspring union instability. Parent religiosity and the number of siblings were negatively associated with instability, young women reported less instability than men, and non-Hispanic Blacks reported more instability than did non-Hispanic Whites (the omitted group).

Table 2.

Negative Binomial Regression of Offspring Union Disruptions on Parent Union Disruptions, Control Variables, and Mediating Variables

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent union disruptions | 0.17*** (0.03) | 0.15*** (0.03) | 0.10** (0.03) | 0.09** (0.03) |

| Parent mother | 0.13 (0.10) | 0.14 (0.10) | 0.14 (0.09) | |

| Parent age | 0.008 (0.006) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | |

| Parent education | −0.05 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.03) | |

| Family income | −0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.0001 (0.0005) | |

| Parent religiosity | −0.18*** (0.03) | −0.15*** (0.03) | −0.11*** (0.03) | |

| Offspring female | −0.38*** (0.05) | −0.31*** (0.05) | −0.38*** (0.05) | |

| Offspring age | −0.06 (0.03) | −0.07* (0.03) | −0.05 (0.03) | |

| Offspring Hispanic | −0.14 (0.08) | −0.18* (0.08) | −0.18* (0.08) | |

| Offspring Black | 0.28*** (0.07) | 0.15* (0.07) | 0.13 (0.07) | |

| Offspring Asian | −0.002 (0.11) | 0.01 (0.10) | 0.06 (0.12) | |

| Number of siblings | −0.06** (0.02) | −0.05* (0.02) | −0.04 (0.02) | |

| Closeness to mothers | −0.06* (0.03) | −0.05 (0.03) | ||

| Closeness to fathers | −0.03 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.04) | ||

| Depression symptoms | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | ||

| Delinquency | 0.19* (0.07) | 0.19* (0.08) | ||

| Suspended/expelled | 0.21*** (0.05) | 0.14** (0.05) | ||

| High school grades | −0.07* (0.03) | −0.02 (0.03) | ||

| Nontraditional attitudes | 0.07 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.05) | ||

| N sexual partners | 0.02*** (0.005) | 0.02** (0.005) | ||

| Educational attainment | −0.04** (0.01) | |||

| Age first union | −0.05*** (0.01) | |||

| Child before first union | 0.41*** (0.09) | |||

| Constant | −3.76*** (0.04) | −2.89*** (0.61) | −2.91*** (0.59) | −2.08*** (0.59) |

Note: Table values are negative binomial regression coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. Sample size is 6,784. Data are from Add Health and are weighted to be nationally representative.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001 (two-tailed).

We then examined associations between parent union instability and the mediating variables by regressing each of the mediators (one at a time) on parent union disruptions with all the control variables in the model. Although not shown in a table, these analyses indicated that parent union disruptions were associated with all of the mediators in the expected directions (p < .05). All of the mediators, therefore, appeared to be good candidates for explaining the link in instability across generations.

Model 3 includes all of the mediators measured in Wave I, when respondents were adolescents. The b coefficient for parent union disruptions declined to .10 (p < .01), which is equivalent to an incident risk ratio of 1.11, or an 11% increase in offspring disruptions associated with each parent disruption. The difference between Models 2 and 3 indicates that the mediators measured during adolescence accounted for almost one third (31%) of the association between parent and offspring disruptions ([16% − 11%]/16% * 100). Model 3 also shows that the number of offspring disruptions was negatively associated with two mediating variables (closeness to mothers and school grades) and positively associated with three mediating variables (delinquency, being suspended or expelled from school, and the number of sexual partners). Although closeness to fathers, symptoms of depression, and nontraditional attitudes were not statistically significant, it is worth noting that these variables were significant predictors of offspring disruptions in models (not shown) that included only one mediator at a time, so correlations between the mediators should be considered in interpreting the results.

Model 4 adds the mediators measured in Wave IV (young adulthood). Educational attainment and age at first union were negatively associated with the number of disruptions, whereas having a child before the first union was positively associated. Adding these mediators reduced the b coefficient for parent union disruptions to .09, which is equivalent to a risk ratio of 9%. Collectively, the mediators accounted for 44% of the intergenerational association ([16% − 9%]/16% * 100).

Sobel tests (MacKinnon, 2008) revealed that delinquency, being suspended or expelled, the number of sexual partners, educational attainment, and age at first union all played significant mediating roles in the analysis (p < .05). Nevertheless, the amount of mediation that could be attributed to any single variable was small. In a series of additional analyses (not shown), we omitted one mediator at a time from the regression equation shown in Model 4. Comparing the b coefficients for parent union disruptions across models made it possible to calculate how much of the association each mediator accounted for net of the others. Although the mediators collectively accounted for 44% of the estimated transmission effect, no single mediator accounted for more than 1%, net of the other mediators. This result occurred, of course, because the mediators were correlated. In other words, young adults who achieved relatively little education also tended to form unions and have children at early ages. They also were more involved in delinquent activities, more likely to be suspended or expelled, less close to parents, less likely to get good grades, and more sexually active during adolescence. Because these outcomes tend to cluster together (theoretically and empirically), it is difficult to consider them in isolation.

In the next step, we incorporated the 981 young adults who had never cohabited or married (but otherwise met the sample criteria) into the analysis by switching to a categorical dependent variable. Table 3 shows the results of a multinomial logistic regression analysis with all control variables in the model. The first column of data compares youth who never formed a union with those still in an intact first union at Wave IV (the omitted comparison group). Parent union disruptions did not appear to increase the likelihood of having no unions relative to being in an intact first union (b = −.08, ns). In contrast, parent union disruptions appeared to increase the likelihood that offspring had either one (b = .18, p < .01) or two or more (b = .28, p < .001) union disruptions, relative to being in an intact first union. Although not shown in Table 3, we rotated the omitted group to allow other comparisons. As expected, parent union disruptions appeared to increase the likelihood of having one union disruption (b = .25, p < .001) or multiple union disruptions (b = .35, p < .001) relative to never having formed a union. Taken together, these results indicate that youth from unstable families of origin tended to form unstable unions, whereas youth from stable families of origin tended to form either stable unions or no unions at all in early adulthood.

Table 3.

Multinomial Logistic Regression of Offspring Union Status on Parent Union Disruptions

| No union vs. intact first union | 1 union disruption vs. intact first union | 2+ union disruptions vs. intact first union | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent union disruptions | −0.08 (0.09) | 0.18** (0.06) | 0.28*** (0.07) |

| Parent mother | 0.05 (0.20) | −0.003 (0.19) | 0.12 (0.23) |

| Parent age | 0.05*** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.004 (0.01) |

| Parent education | 0.13** (0.05) | −0.12** (0.04) | −0.08 (0.05) |

| Family income | 0.0002 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.0005 (0.001) |

| Parent religion | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.19*** (0.05) | −0.30*** (0.05) |

| Offspring female | −0.64*** (0.12) | −0.18* (0.09) | −0.71*** (0.09) |

| Offspring age | −0.19** (0.08) | −0.09 (0.05) | 0.05 (0.06) |

| Offspring Hispanic | 0.36* (0.16) | 0.18 (0.13) | −0.46** (0.17) |

| Offspring Black | 0.55** (0.18) | 0.33** (0.12) | 0.53*** (0.13) |

| Offspring Asian | 0.56** (0.21) | −0.18 (0.22) | 0.04 (0.20) |

| Number of siblings | 0.02 (0.04) | −0.07* (0.03) | −0.11** (0.04) |

| Constant | −0.61 (1.36) | 0.69 (0.85) | −0.16** (1.17) |

Note: Table values are multinomial logistic regression coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. Sample sizes are 981 (no unions), 3,672 (1 union intact), 1,913 (1 union disruption), and 1,199 (2+ union disruptions). Data are from Add Health and are weighted to be nationally representative.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001 (two-tailed).

We also conducted an analysis in which we incorporated information on the quality of intact parent unions. Specifically, we regressed offspring union disruptions on the high-discord variable (described earlier) for youth who had lived continuously with two parents (n = 4,814). An analysis that included all of the control variables (comparable to Model 2 in Table 2) produced a b coefficient of .20 (p < .001) for discordant unions. The corresponding risk ratio indicated that living with parents in stable, high-discord unions appeared to increase offspring union disruptions by 22%, relative to living with parents in stable, low-discord unions. With all of the mediators included (comparable to Model 3 in Table 3) the b coefficient declined to .17 (p < .01)—or a 19% increase in risk. This result indicates that the mediators accounted for only 14% of the estimated effect of discord ([22% − 19%]/22% * 100). Overall, the consequences of parent union discord and parent union instability appeared to be similar, but the estimated effect of discord was more difficult to explain with the mediators in our analysis.

Discussion

We argued that new research on the ITD should (1) be expanded to include the disruption of cohabiting unions and (2) replace binary variables (not divorced versus divorced) with count variables (the number of disrupted unions). We applied this approach to data from the Add Health study to investigate the intergenerational transmission of union instability in the early adult years. Our approach assumes that all forms of parent union disruption (including parental death) have similar (although not necessarily identical) problematic consequences for children—an approach consistent with a variety of earlier studies (Amato & Anthony, 2014; Cherlin, Kiernan, & Chase-Lansdale, 1995; McLanahan & Sandefur). In a study particularly relevant to the current one, Teachman (2002) found that parental death (as well as parental divorce) predicted offspring divorce. Our approach also is consistent with prior work showing that divorce and cohabitation disruption have similar predictors (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002), and that pooling both forms of union instability in analyses yields meaningful results (Kiernan & Cherlin, 1999; Manning, Smock & Majumdar; 2004).

Even though the Add Health sample was relatively young, a good deal of union instability already had occurred by Wave IV. Of all respondents who had ever married, 20% already had divorced. And of all respondents who had cohabited but not married, 52% had split up. Counting disrupted cohabitations substantially expanded the range of the dependent variable. Of all union disruptions in the data, the majority (79%) were disrupted cohabitations rather than marriages. Consequently, ignoring cohabiting unions would have substantially underestimated the amount of instability in young people’s lives.

Our negative binomial regression analysis found that each parent union disruption was associated with a 16% increase in the number of offspring union disruptions, net of a large number of control variables. Although a 16% increase might not seem like a large effect, instability in the family of origin was a risk factor for dropping out of the sample (as we noted earlier) and may have attenuated the strength of the association. Moreover, the mean age of respondents in Wave IV was only 30 years. Many individuals in the study who had not yet experienced a union disruption eventually will, and many individuals who reported a disruption will experience additional ones in the future. As unstable unions accumulate across the life course, the magnitude of the intergenerational correlation is likely to increase. This should occur because restricting the amount of variation in a variable attenuates the magnitude of its correlation with other variables.

Despite the modest strength of the association, our study indicates that the ITUI begins relatively early in the life course, that is, within the first decade of adulthood. If we could extend our view earlier in time to include adolescent dating relationships, we might find that the ITUI appears even earlier. Of course, breaking up with dating partners is expected, given that one purpose of dating is to rule out poor matches. Nevertheless, a history of close relationships—especially those with a sexual component—that break up during adolescence and early adulthood might be an indicator of difficulty in forming stable intimate relationships in later life. Given that the number of parent union disruptions was positively associated with the number of offspring sexual partners in the current study, this hypothesis is likely.

Our multinomial analysis demonstrated that youth from unstable families tended to form unstable unions, whereas youth from stable families tended to form either stable unions or no unions at all in early adulthood. Presumably, many offspring who had not formed unions were biding their time until they had finished their educations, became established occupationally, or found the “right” partner. Postponing first union formation until the late 20s or 30s may be an adaptive strategy for some youth in an era of high union instability.

Our mediation analysis included a relatively large number of potential mechanisms. Although examining only one or two mediators might have produced a sharper focus, our goal was to cast the broadest net possible to explain the ITUI. The 11 mediating variables in our analysis (all suggested by theory) explained 44% of the estimated intergenerational effect. This is not a large share, but it is not trivial either. A limitation of our analysis is that many potential mediators were not available in the data set. For example, we had no direct measures of offspring’s relationship skills, attitudes toward union disruption, emotional insecurity, and so on. Moreover, some of our mediators consisted of single items with unknown reliabilities (such as our measure of attitudes). The ideal study of the ITUI, rather than relying on secondary data, would collect its own data to ensure that the availability of a broad range of theoretically informed mediators.

Although several variables played significant mediating roles in the analysis, the amount of mediation attributed to any one variable net of the others was small (no more than about 1%). Because risk factors for union disruption tend to co-occur, it is difficult to isolate the independent effects of each. Moreover, because the explanatory perspectives suggest similar mediators, it is not possible to conduct a definitive test of one perspective versus the others. Instead, our analysis provides some support for all of the perspectives, with the exception of the perspective based on nontraditional attitudes for which we lacked good measures. We believe that this is a common situation in the social sciences, where most phenomena are multiply determined. Perhaps the most straightforward way of framing these results is to conclude that family-of-origin instability increases multiple risk factors for offspring union instability, with the mediators in our analysis being a subset of these factors. Future research may be able to provide a more comprehensive set of risk factors, ideally measured prior to first offspring union formation.

Although we have focused on parent union instability, our study also found that discord in stable parent unions (usually marriages) also predicted offspring union instability. Indeed, our analysis estimated that growing up with two parents in a stable but discordant union increased offspring union disruptions by 22%. Given that each parent union disruption increased offspring disruptions by 16%, it appears that the impact of a stable but discordant parent union was roughly equivalent to that of one parent union disruption. Indeed, one could argue that the ultimate causal factor in the ITUI is not parent union instability but the discord that precipitates (and often follows) instability. But even if a single parent union disruption is no worse than growing up with two discordant parents, multiple instances of parent union instability (2 or more disruptions) appear to be even more problematic for offspring.

The results for discord provide support for the relationship skills perspective, because it assumes that children from discordant but intact families (like children from unstable families) often fail to learn appropriate relationship skills. Of course, this finding also is consistent with a stress perspective (because parental discord is stressful for children), an attachment and emotional insecurity perspective (because parental discord undermines children’s emotional security), and a risky life course and choice perspective (because parental discord interferes with parental supervision and guidance). Irrespective of the explanation, the present study indicates that children with the most stable relationships in early adulthood were those who grew up with parents in stable and happy unions. Both stability and relationship harmony in the family of origin appear to play important roles in stabilizing children’s future relationships.

In addition to our independent variables, several control variables predicted offspring union instability. The negative binomial regression analysis (Table 2) indicated that parent religiosity was associated with less offspring union instability, and African Americans had a comparatively high level of instability. Similarly, the multinomial logistic regression analysis (Table 3) suggested that parent education increased the likelihood that offspring either refrained from forming unions or had stable unions. Moreover, compared with non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics and Asians were more likely to refrain from forming unions, Hispanics were less likely to have two or more union disruptions, and non-Hispanic Blacks were more likely to either have unstable unions or no unions at all. These findings are generally consistent with prior research on the predictors of union formation and dissolution (Amato, 2000; Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). We assume that these ethnic and racial differences in our study reflect a complex set of cultural and socioeconomic factors, although we do not have the space to examine these in more detail. The number of siblings also was negatively associated with offspring instability in Tables 2 and 3. Although this finding does not have a precedent in the literature, it may be that family size is a proxy for parents having a strong family orientation or more traditional views about family life.

Like all studies, the current one has many limitations. We had no information on parent union disruptions when children were older than 16, we could not follow offspring into the mid-adult years (when many union disruptions undoubtedly occurred), we had only a partial set of theoretically relevant mediators available in the data set, and we could not control for genetic transmission. We also were unable to deal with reverse causality during childhood. More specifically, child problems like depression and delinquency may have contributed to parent union disruptions. Moreover, like almost all studies in this literature, we lacked information on whether the respondents’ partners experienced parent union disruptions while growing up. Nevertheless, our study has the advantage of being based on national data from two generations, with parents providing information on the independent variable (and the key control variables) and offspring providing information on the dependent variable (and the mediating variables). We also were able to expand the framework of research on the ITD to capture the full range of union instability in people’s lives. Previous research suggests that repeated instances of family-of-origin instability create many problems for young children (Fomby & Cherlin, 2007), and the current study extends the scope of this work to early adulthood. The ITUI continues to be a topic of interest to policy makers, practitioners, and the media. A better understanding of this phenomenon should be useful, not only to social scientists who study intergenerational transmission, but also to practitioners who work with couples to achieve stable and satisfying relationships—especially those from unstable families of origin.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth. This research was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to the Population Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University for Population Research Infrastructure (R24 HD041025) and Family Demography Training (T-32HD007514).

Contributor Information

Paul R. Amato, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, 201 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802-6207

Sarah Patterson, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, 201 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802-6207.

References

- Amato PR. Consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1269–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Explaining the intergenerational transmission of divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:628–640. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Anthony CJ. Estimating the effects of parental divorce and death with fixed effects models. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014;76:370–386. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, DeBoer D. The transmission of divorce across generations: Relationship skills or commitment to marriage? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1038–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Booth A. A generation at risk: Growing up in an era of family upheaval. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Kane JB. Parents’ marital distress, divorce, and remarriage: Links with daughters’ early family formation transitions. Journal of Family Issues. 2011;32:1073–1103. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11404363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn WG, Thornton A. The influence of parents’ marital dissolutions on children’s attitudes toward family formation. Demography. 1996;33:66–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Fincham FD, Amir N, Leonard KE. The taxometrics of marriage: Is marital discord categorical? Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:276–285. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. 2. New York: Basic books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. Vital Health Statistics, Series 23. 22. National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Shaver PR. Attachment styles and personality disorders: Their connections to each other and to parental divorce, parental death, and perceptions of parental caregiving. Journal of Personality. 1998;66:835–878. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess EW, Cottrell LS. Predicting success or failure in marriage. New York: Prentice-Hall; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ, Kiernan KE, Chase-Lansdale PL. Parental divorce in childhood and demographic outcomes in young adulthood. Demography. 1995;32:299–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann A, Englehardt H. The social inheritance of divorce: Effects of parent’s family type in postwar Germany. American Sociological Review. 1999;64:783–793. [Google Scholar]

- Diekman A, Schmidheiny K. The intergenerational transmission of divorce: A fifteen-country study with the fertility and family survey. Comparative Sociology. 2013;12:211–235. [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Turkheimer E, Emery RE, Harden KP, Slutske WS, Heath AC, Madden PAF, Martin NG. A genetically informed study of the intergenerational transmission of marital instability. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:793–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dronkers J, Harkonen J. The intergenerational transmission of divorce in cross-national perspective: Results from the fertility and family surveys. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography. 2008;62:273–288. doi: 10.1080/00324720802320475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dush CMK, Taylor MG, Kroeger RA. Marital happiness and psychological well-being across the life course. Family Relations. 2008;57:211–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas MJ. Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Feng D, Giarrusso R, Bengtson VL, Frye N. Intergenerational transmission of marital quality and instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:451–463. [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, Cherlin AJ. Family instability and child well-being. American Sociological Review. 2007;72:181–204. doi: 10.1177/000312240707200203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design. 2009 http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Hazan C, Shaver PR. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DR, Amoloza TO, Booth A. Stability and developmental change in marital quality: A three-wave panel analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1992;54:582–594. [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan KE, Cherlin A. Parental divorce and partnership dissolution in adulthood: Evidence from a British cohort study. Population Studies. 2010;53:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JT. The pattern of divorce in three generations. Social Forces. 1955;34:213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Li JA, Wu LL. No trend in the intergenerational transmission of divorce. Demography. 2008;45:875–883. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopoo LM, DeLeire T. Family structure and the economic wellbeing of children in youth and adulthood. Social Science Research. 2014;43:30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ, Majumdar D. The relative stability of marital and cohabiting unions for children. Population Research and Policy Review. 2004;23:135–159. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Bumpass L. Intergenerational consequences of family disruption. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:130–152. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Sandefur G. Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Percheski C. Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34:257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Three fragments from a sociologist’s notebooks: Establishing the phenomenon, specified ignorance, and strategic research materials. Annual Review of Sociology. 1987;13:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller CW, Pope H. Marital instability: A study of its transmission between generations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1977;39:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. Cohabiting and marriage during young men’s career-development process. Demography. 2003;40:127–149. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C, Manning WD, Smock PJ. Married and cohabiting parents’ relationship stability: A focus on race and ethnicity. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:1345–1366. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C, Taylor ME, Altman J. Social cognitive mediators and relational outcomes associated with parental divorce. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:361–377. [Google Scholar]

- Teachman J. Childhood living arrangements and the intergenerational transmission of divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:717–729. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy JL, Shaver PR, Albino AW, Cooper ML. Attachment styles and adolescent sexuality. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romance and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 137–162. [Google Scholar]

- Webster PS, Orbuch TL, House JS. Effects of childhood family background on adult marital quality and perceived stability. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;101:404– 432. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger NH. Trends in the intergenerational transmission of divorce. Demography. 1999;36:415–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger NH. Beyond the intergenerational transmission of divorce: Do people replicate the patterns of marital instability they grew up with? Journal of Family Issues. 2000;21:1061–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger NH. Understanding the divorce cycle. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger NH. More evidence for trends in the intergenerational transmission of divorce: A completed cohort approach using data from the General Social Survey. Demography. 2011;48:581–592. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]