Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma is a relatively common tumor, with an estimated 63,000 new cases being diagnosed in the United States in 2016. Surgery, be it with partial or total nephrectomy, is considered the mainstay of treatment for many patients. However, those patients with small renal masses, typically less than 3 to 4 cm in size who are deemed unsuitable for surgery, may be suitable for percutaneous thermal ablation. We review the various treatment modalities, including radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation, and cryoablation; discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each method; and review the latest data concerning the performance of the various ablative modalities compared with each other, and compared with surgery.

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, microwave ablation, cryoablation, radiofrequency ablation, interventional radiology

Objectives : Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to describe the indications, techniques, and outcome data for percutaneous thermal ablation of small renal masses.

Accreditation : This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of Tufts University School of Medicine (TUSM) and Thieme Medical Publishers, New York. TUSM is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit : Tufts University School of Medicine designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit ™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a commonly encountered tumor, with an estimated 63,000 new cases of RCC being diagnosed in the United States in 2016. 1 Given the risk of decreased renal function associated with complete nephrectomy, nephron-sparing techniques, such as partial nephrectomy or local ablation, are now considered standard of care in suitable patients.

Initial tumor ablative techniques involved the use of percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) directly into tumors, a technique that is still used today for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma 2 and papillary thyroid cancer metastases. 3 The late 1990s saw the relatively rapid development of thermal ablative technologies for clinical use, which are now well-established minimally invasive oncologic treatments. The first thermal ablation performed as the sole treatment modality for RCC was performed in 1999. 4 Various thermal modalities have been used, including radiofrequency, 5 microwave, 6 cryoablation, 7 laser, 8 and, more recently, irreversible electroporation (IRE). 9 Herein, we discuss the state of the art for renal tumor ablation.

Patient Selection

Surgery remains the gold standard for management of RCC, 10 with partial nephrectomy (or nephron-sparing surgery, NSS) preferred to open nephrectomy whenever possible, 11 to preserve as much renal function as possible, while also ensuring oncologic control is obtained. However, thermal ablative techniques are an established and accepted alternative to surgery, in those patients who may be considered unsuitable or high risk for surgical intervention, such as those with multiple medical comorbidities. 12

Management of small renal masses (<3 cm) may take the form of surgery or ablation; however in some patients, observation alone may be considered appropriate, given that tumors less than 3 cm are relatively unlikely to metastasize. 13

Ablative treatments are typically performed with monitored conscious sedation using midazolam and/or fentanyl, for example, and in occasional patients, deep sedation with monitored anesthesia care (MAC) or general anesthesia may be required. 14 15 16 17 18

Imaging Guidance

In our institution, the overwhelming majority of renal tumor ablations are currently performed using CT guidance. This allows for precise placement of the ablation probe, either by visualization of the mass using the non-contrast or contrast-enhanced images at the time of ablation or, in the case of lesions that are difficult to see, by the relationship with surrounding structures and anatomic outlines.

Ultrasound can also be used, and it provides an approximation of the treatment zone as a result of microbubble formation from radiofrequency ablation (RFA), for example, that can be monitored in real time. 13 Although MRI has been used for tumor ablation, 8 the logistics involved in performing a procedure in an MRI suite are not to be underestimated, and for that reason, CT remains the most common imaging modality used for tumor ablation. 19

Radiofrequency Ablation

Perhaps one of the most established ablative techniques, RFA has been a part of clinical practice for more than 20 years, and has been used to treat a wide variety of conditions ranging from osteoid osteoma to hepatocellular carcinoma and RCC. 20 21 22 23 24

The general principal behind RFA is to expose the tumor to high temperatures (typically above 55°C), resulting in a cytotoxic effect. 25 It has been shown that temperatures above 60°C result in almost instantaneous cell death, whereas temperatures between 50 and 60°C result in coagulation, with subsequent cell death occurring in a matter of minutes. 26 This can be attained by the use of a single tip electrode, multitined expandable electrodes, or a cluster tip electrode, the third typically containing three tips. As with all ablation techniques, a treatment strategy involving overlapping of the treatment zones is frequently undertaken. It follows that small renal tumors typically require fewer overlapping ablations, compared with their larger counterparts. 22

By applying an alternating electric current to tissue, ions in the tissues are disturbed, causing friction and heating. 27 The water molecules immediately adjacent to the RF probe vibrate with application of the current, and the friction between molecules ultimately results in an increase in temperature. It is worth noting that the electrode does not generate heat, rather it produces an electromagnetic field that in turn affects the molecules nearby. The frictional heat that is generated then travels a short distance (dropping exponentially) in the ablation zone, producing tissue destruction and coagulative necrosis.

The optimal size of a renal tumor for RFA is in the region of 3 cm, although larger lesions can be treated by overlapping ablations. 27 Because it was the initial percutaneous thermal ablative technique that became widely used, there is a relatively large amount of data showing efficacy, 15 18 28 safety, 17 cost-effectiveness, 29 and acceptance both by radiologists and referring oncologists, alike. The disadvantages of RFA include the risk of skin pad burns, relatively slow speed (particularly compared with microwave), and the issue of “heat-sink” effect, although the latter is common to all thermal ablative techniques.

RFA has been shown to be successful in the treatment both exophytic renal tumors and those within the renal parenchyma. 22 In some cases, repeat treatments may be necessary, either as a planned two-stage treatment or due to residual disease on follow-up imaging.

The effect of RFA on the treated tissue volume is limited by heat dissipation (or heat sink, discussed later), and also by the physical changes that occur in the tissue during treatment. Desiccation and charring that occur during the treatment result in an increase in impedance, limiting the current that can be applied to the remainder of the tissue. This is further limited by the local environment surrounding the tumor, and although the high impedance that is seen in normal lung parenchyma can be problematic for treating pulmonary tumors, this is less of an issue in the case of renal ablation. 30 31 Some have postulated that the presence of a high electrolyte concentration in the urine of the renal collecting system may result in inadvertent heating of nontarget structures. 26 32 Strategies that perfuse the collecting system may mitigate this effect for tumors near the ureter.

It is not surprising that RFA is most successful in those tumors that are less than 3 cm in size, which are often completely treated in a single sitting. 33 However, even in those patients who have residual disease on follow-up, this can often be treated successfully with a repeat ablation.

In one study where 159 renal tumors ranging in size from 0.9 to 5.4 cm were treated using RF ablation, there was an initial success rate of 95%, as defined by no evidence of residual tumor on the first follow-up imaging study. In those cases where residual tumor was identified, additional ablation was performed in five of eight cases, resulting in an overall success rate of 98%.

Microwave Ablation

Microwaves are a portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that lie between the frequencies of 900 and 2,450 MHz. Modern generators are capable of delivering power up to 140 W. Unlike RFA, microwave does not require the use of grounding pads, eliminating the risk of skin damage. 34 Although the end-effect of microwave ablation is the same as RFA, namely, coagulative necrosis as a result of thermal injury, the way in which such heat is delivered is different. In the case of microwave ablation, polar molecules (such as water) align with an oscillating microwave field, increasing kinetic energy and, as a result, tissue temperature. Water molecules flip back and forth between two and five billion times per second. 35 The advantages of microwave ablation over RFA include the following:

The charring and subsequent increase in impedance (and decrease in deliverable energy) that occurs with RFA is not applicable in the case of microwave ablation, as microwaves are transmitted through all tissues, even those with high impedance. 36

The active treatment area (in the region of 2–3 cm) 36 37 is much larger than that achieved using RFA, which is the order of millimeters. 38 In fact, treatment areas approaching 8 cm have been described, without the need to reposition the antenna 30 ( Fig. 1 ).

Microwave produces active heating of the majority of the ablated tissue, unlike RFA, where the heat is generated in just a small region, and then passes to the neighboring tissue by heat conduction. Thus, microwave ablation is less susceptible to the heat-sink effect that can result in incomplete treatment of tumors adjacent to vessels. 36 39

Although many of the initial microwave systems were limited, advances in the past decade have allowed for the generation of more energy for a prolonged period of time, thereby increasing the speed at which lesions can be treated, and decreasing the need for overlapping ablations. 36 40

Fig. 1.

A 72-year-old man who had undergone a previous RFA of a right renal tumor. Approximately 3 years later, a routine surveillance CT was performed ( a ), revealing recurrent tumor (arrow) in the prior ablation zone (arrowhead). He elected to undergo microwave ablation ( b ), with the immediate postprocedure CT showing some small pockets of gas in the right kidney ( c , arrowheads). A follow-up CT 2 months later revealed no evidence of residual or recurrent tumor in the ablation zone ( d , arrowhead).

However, microwave has faced its own set of challenges when it comes to power delivery, in the form of reflectivity. 41 The reflection coefficient determines how efficiently the antenna is able to transmit power into the tissue, and has been tweaked by adjustments and advances in the antenna design. 42

In addition, the increase in the treatment zone that is achieved with microwave ablation is weighted toward the long axis of the probe, which increases the risk of burns to the body wall, peritoneum, and nearby structures. 43 The estimated zone of ablation is frequently calculated based on manufacturers' guidelines, and in many cases, those parameters have been determined using ex vivo animal models. It is likely that perfused organ ablation zones are less than those predicted by the manufacturers, 44 a fact that should be borne in mind during percutaneous tumor ablation.

A recent study by Yu et al examined the midterm outcomes of microwave ablation for renal tumors, compared with open radical nephrectomy (ORN). The authors treated 163 patients with small RCC (≤4 cm) over a 6-year period. Sixty-five patients underwent microwave ablation and the remaining patients underwent ORN. For RCC-related survival, the estimated 5-year survival rates were 97.1% after microwave ablation and 97.8% after ORN. 45

Cryoablation

Modern cryoablation systems are relatively compact, and use compressed gases to alternate between freezing and thawing. When a gas expands or contracts, the temperature of that gas changes in accordance with the Joule-Thomson effect. The two most commonly used gases are argon and helium, which cool and warm, respectively, as the gas expands. In the case of the freeze cycle, argon gas is allowed to expand, resulting in a heat sink of approximately 9 kJ, generating an ice-ball with temperatures as low as −140°C. 40 46 47 Importantly, the zone of ablation where cell death occurs lies some distance from the outer margin of the visible ice ball, in the lethal isotherm range of −20 to −40°C.

Tissue destruction in cryoablation can occur from direct cell damage related to intracellular ice formation and damage to the cell membrane, 48 typically occurring at the lowest temperatures. At somewhat higher temperatures, extracellular ice crystals form, changing the osmolality of the tissue volume, which in turn leads to cell dehydration and death. 49

Cryoablation probes typically range in size between 13 and 15 gauge, creating ablation zones ranging in size from 1.5 to 2.5 cm. However, systems are equipped to simultaneously activate several probes, allowing for the potential to ablate considerably larger volumes of tissue ( Fig. 2 ), in the region of 8 cm. 50

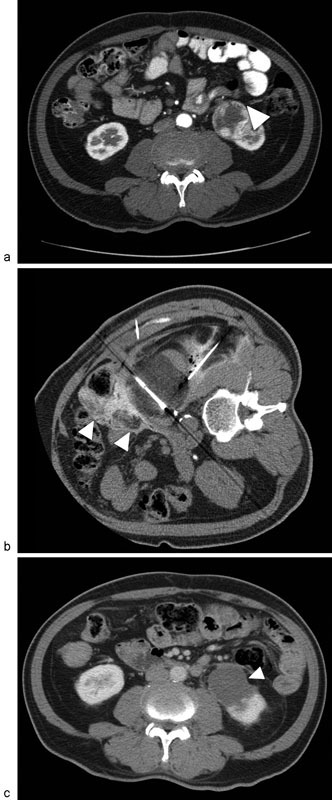

Fig. 2.

A 67-year-old man with a 5-cm renal cell carcinoma in the lower pole of the left kidney. Axial contrast-enhanced CT ( a ) demonstrates a heterogeneously enhancing mass in the lower pole of the left kidney (arrowhead). Cryoablation was performed with three probes ( b ), together with hydrodissection (arrowheads) to protect the nearby bowel. Follow-up CT after 4 weeks revealed no evidence of residual or recurrent disease ( c , arrowhead).

A key advantage of cryoablation over heat-based ablations is the ability to monitor the ice ball using imaging guidance with ultrasound, CT, or even MRI. This allows the treating physician to estimate the ablation zone, noting that the actual area in which cell death occurs is typically several millimeters inside the edge of the ice ball. 30

Another advantage of cryoablation is that central structures such as the ureter and collecting system may be less at risk of injury compared with heat-based methods of tumor ablation. 51 Cryoablation has now been widely available for over 15 years; the short- and long-term data show that this technique is oncologically viable. 52

Irreversible Electroporation

This nonthermal ablation technique is one of the newest ablation technologies available for the treatment of small renal masses. High-voltage electrical pulses are used to increase permeability of the cell membrane, leading to apoptosis. 53 Unlike the other ablation techniques, this form of treatment requires general anesthesia, as the patient needs to be paralyzed. The pulses are synced to the cardiac cycle.

An impressive advantage of IRE over the other ablative techniques is that it does not result in heating of tissues and, as a result, is not affected by tissue-mediated perfusion (“heat-sink”) in the same way as RFA. There is relatively little damage to surrounding normal structures, and the treatment is frequently completed in a matter of minutes.

A disadvantage is that extreme precision is required (within millimeters), to ensure that the correct volume of tissue is treated, and adjustments during the ablation are not possible. 54 The cost of the equipment is high, patients require general anesthesia, and there is a risk of cardiac arrhythmias. 55 Conclusive data regarding the utilization of IRE for small renal masses are not yet available, although ongoing research, such as the IRENE trial, a prospective Phase 2a pilot study investigating focal percutaneous IRE ablation, may provide more information in the future. 56

Postprocedure Observation

It is our practice to discharge the majority of patients after a period of observation ranging between 3 and 4 hours, if they have met our departmental discharge criteria, including absence of significant hematuria, normotension and with adequate home supports and pain control. Those patients with lightly blood-tinged urine are generally discharged home, whereas those with moderate or severe hematuria, including those patients with clots in the urine, may require overnight observation.

Complications

Similar to a renal biopsy, there is risk associated with traversing the renal capsule during an ablation, where disruption of capsular blood vessels may result in subcapsular or retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

In general, the larger diameter of the ablation probes, the larger the area that can be treated with a single ablation. Although it may seem logical to use the narrowest possible gauge probe, the counterargument is that more manipulation, and possibly even additional passes through the renal capsule, may result in an increased risk of hemorrhage. 57 Tract ablation using systems equipped with radiofrequency capabilities is performed by some operators, to coagulate the tract. No studies are available to assess the potential impact of this practice, however.

Hematuria is also a well-recognized complication, and can occur when there is irritation to the urothelium related to thermal ablation. Another potential complication is injury to the proximal ureter from the ablation zone. This may present in the early-procedure period with hydronephrosis, and may require placement of a ureteric stent or nephrostomy.

One way to decrease the risk of ureteric injury is the use of pyeloperfusion, whereby retrograde infusion ( Fig. 3 ) of 5% dextrose (D5W) is performed via a ureteric stent placed by a urologist immediately before the ablation. 58 The open-ended ureteric stent is placed into the renal pelvis or proximal ureter, and secured to a Foley catheter that remains in the bladder for the duration of the procedure. The Foley catheter also allows for urine output to be monitored for both volume and the presence of hematuria, during and immediately after the ablation. In patients undergoing RFA, cooled 5% dextrose is used, whereas warmed saline is used during cryoablation. In many cases, gravity drip alone is sufficient to maintain pyeloperfusion, although pumps can also be utilized.

Fig. 3.

A 59-year-old man with a small renal cell carcinoma in the left kidney. Axial T1 fat-saturated postcontrast image ( a ) shows a 2.5-cm mass in the left kidney (arrow). Image from the cryoablation procedure ( b ) shows the advancing ice ball (arrowheads), with the ureter protected by the indwelling stent (arrow), through which pyeloperfusion was obtained. Follow-up coronal T1 fat-saturated postcontrast subtracted image ( c ) at 6 weeks shows no evidence of residual tumor (arrow), and no hydronephrosis.

In cases where there are other important structures nearby, such as the duodenum or colon, hydrodissection may be employed ( Fig. 4 ). This involves placing a needle under image guidance between the target organ and the adjacent structure, and injecting 5% dextrose (commonly 300–500 mL) to maintain a safe space between the tumor undergoing treatment and the nearby structure. It is also useful to add a small amount of iodinated contrast to the fluid, as this improves visibility of nearby bowel, and in the case of cryoablation, the ice ball.

Fig. 4.

A 55-year-old woman with a 2.4-cm mass in the left kidney (arrowhead), biopsy-proven papillary renal cell carcinoma ( a ). Prior to cryoablation, hydrodissection was performed with dilute iodinated contrast ( b , arrowhead), to displace the nearby large and small bowel. The ice ball was visualized after 10 minutes ( c , arrowhead), the adjacent structures were successfully protected.

During RF ablation, ionic solutions such as saline must be avoided in both pyeloperfusion and hydrodissection, to prevent conduction of current. Hence, 5% dextrose is utilized.

In addition to bleeding and damage to adjacent structures such as the ureter, inadvertent damage to nerves has also been described, which may result in flank numbness in the case of local sensory nerve injury, or ipsilateral groin numbness when the genitofemoral nerve is inadvertently injured as it passes over the psoas muscle. 59

Incomplete treatment has sometimes been ascribed to the “heat-sink” effect, whereby tumors (particularly those located centrally) may not undergo complete necrosis due to convection of heat (or cold) away from the target area by blood vessels. 60 61 This has been shown on both in vivo and ex vivo models, 62 with decreased coagulative necrosis as a result of perfusion-mediated tissue cooling.

Follow-up

To assess for success of treatment, follow-up imaging with CT or MRI is typically obtained approximately 4 weeks following treatment. 60 Subsequent imaging may be obtained at 3, 6, and 12 months, or as per local clinical protocols. 13 The exact follow-up protocol will vary between institutions; however, an advantage of performing a 4-week follow-up scan is that should residual tumor be identified, and a repeat ablation is considered necessary, this can be performed earlier.

Comparison between Treatment Options

When compared with partial nephrectomy, the advantages of thermal ablation include decreased risk of blood loss, faster recovery, and the potential to perform the treatment on an outpatient basis. 33 Due in part to the rapid adaptation and subsequent refinements of ablation technology, there is a notable lack of randomized control trials and comparative trials in the ablation literature. 30

One of the first studies to compare radiofrequency with microwave in a porcine model showed that heat dissipation due to the presence of local blood vessels was 4% in microwave but 26% using an RF system. This is important, given that the protection afforded by perfusion-mediated cooling is an important factor in both incomplete treatment and tumor recurrence in the region of blood vessels. 39

Comparative studies between ablation methods have mainly been retrospective. A 2012 meta-analysis examined the efficacy and complication rates of cryoablation compared with RFA in the treatment of small renal tumors, incorporating 31 case series, 20 of which involved cryoablation and the remainder utilized RFA. 63 The authors found that the clinical efficacy and complication rates were similar for both modalities. Specifically, the clinical efficacy was calculated at 89% for cryoablation (457 cases) and 90% in RFA (426 cases).

In another study, 385 patients with 445 tumors measuring 3.0 cm or smaller over a 10-year period were examined, with 256 tumors undergoing RFA and 189 tumors being treated with cryoablation. 64 The complication rate for both procedures was similar, with major complications occurring in 4.3% of RFAs and 4.5% of cryoablations ( p = 0.91). The authors found that treatment of central tumors with RFA was associated with challenges, something that had been previously described. 65 66 Cryoablation may be more successful in treating central tumors due to decreased effect of the perfusion-mediated temperature changes (compared with RFA), and also because many believe that damaging the renal collecting system with cold, rather than heat, is likely to be associated with decreased adverse consequences, 67 68 allowing for potentially more aggressive treatment with cryoablation. 64

A large series (1,424 patients) from 2015 compared the outcomes following partial nephrectomy and percutaneous ablation for small (cT1) renal masses. 69 The authors found that recurrence-free survival was similar in patients who had undergone either partial nephrectomy or percutaneous ablation. Metastasis free survival rates at 3 years for partial nephrectomy, RFA, and cryoablation were 99, 93, and 100%, respectively. Although the overall survival was highest for those patients who underwent partial nephrectomy, the authors commented that a selection bias may have resulted in younger and healthier patients being selected for surgical treatment.

This relative equivalence is contrary to some previous studies, which suggested the risk of local recurrence was higher with percutaneous ablation than with surgery. 70 71 The authors of the more recent article 69 postulated that improved experience and more careful selection of patients may have resulted in better outcomes in their ablation patients. Nonetheless, even in those patients with residual or recurrent disease following percutaneous ablation, repeat treatment may obtain adequate control.

Manufacturers of both microwave and RFA systems have incorporated improvements into their respective technologies over the past two decades. In the case of RF, this has centered around efforts to increase the volume of ablated tissue, by the use of cluster electrodes or cooled-tip delivery systems, for example. 72 73 74

Multi-tined systems improve heat delivery using RF both by increasing the cumulative surface area and by reducing impedance. By allowing cooling fluid to circulate inside the electrode, temperatures at the electrode–tissue interface are reduced, decreasing charring and allowing for increased deposition of power, 40 a benefit that is largely independent of the temperature of the coolant. 75 For microwave, advances have mainly been in the field of improving both the magnitude and duration of power that can be delivered during one treatment. 41 76

Minimally invasive treatment options such as thermal ablation have the greatest efficacy in patients with small tumors, generally tumors less than 4 cm in size (T1a tumors). 77 In such patients, 5- and 10-year recurrence-free survival rates have been reported as high as 96.1 and 93.2%, respectively. 15 Patients with T1b tumors (4–7 cm) still have reasonable disease control: the 5-year disease-free survival was reported as 74.5%, compared with 91.5% for those patients with a T1a tumor.

It has been noted that there has been little prospective research comparing surgery (radical or partial nephrectomy) directly with image-guided tumor ablation, 78 and so continuing high-quality research on outcomes is required. A retrospective cohort study comparing NSS to ablation based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry reviewed almost 9,000 cases of RCC. 79 In those patients with more than 5 years of follow-up, the authors reported a survival benefit of surgery compared with ablation (hazard ratio: 3.0), although the result did not reach statistical significance.

In another retrospective study comparing partial nephrectomy with RFA, the 3-year recurrence-free survival was reported as 93.4% for RFA and 95.8% for partial nephrectomy, 80 with 100% disease-specific survival in both groups at 3 years.

Predicting those tumors that are most likely to benefit from thermal ablation has typically been performed on the basis of size (3–4 cm). However, recently efforts have been made to identify tumors likely to be successfully treated on the basis of other features. In one study, 751 renal tumors were analyzed using five anatomic components, namely, radius (maximal tumor diameter), exophytic/endophytic properties, proximity of the deepest portion to the tumor of the collecting system or renal sinus, anterior/posterior, and location relative to the polar line. 81 Each element was given a score, with the total resulting in a R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score.

Although previously used to direct surgical management, 82 83 84 85 complications, and outcomes, the R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score was also shown by the authors to be effective in predicting oncological outcomes following percutaneous thermal ablation (both radiofrequency and cryoablation). Their analysis showed that patients with a high R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score were 14.3% more likely to suffer a major complication, and the risk of local failure increased by 11.4%. 81 Such scoring systems are useful to provide some level of standardization both within clinical studies and for comparison of outcomes between different clinical studies, but may not be used routinely in all settings.

Conclusion

Percutaneous renal tumor ablation is an accepted alternative treatment for selected renal tumors in patients who are not ideal candidates for surgery. Regardless of the ablation technique chosen, practitioners should familiarize themselves with the systems being utilized, particularly as modifications to both antennae and generator systems may occur. The operator should be familiar with the expected ablation zones produced at different machine settings, and based on the local tissue and need to protect nontarget structures.

References

- 1.Siegel R L, Miller K D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(01):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pompili M, De Matthaeis N, Saviano A et al. Single hepatocellular carcinoma smaller than 2 cm: are ethanol injection and radiofrequency ablation equally effective? Anticancer Res. 2015;35(01):325–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis B D, Hay I D, Charboneau J W, McIver B, Reading C C, Goellner J R. Percutaneous ethanol injection for treatment of cervical lymph node metastases in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178(03):699–704. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.3.1780699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGovern F J, Wood B J, Goldberg S N, Mueller P R. Radio frequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma via image guided needle electrodes. J Urol. 1999;161(02):599–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gazelle G S, Goldberg S N, Solbiati L, Livraghi T. Tumor ablation with radio-frequency energy. Radiology. 2000;217(03):633–646. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.3.r00dc26633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibata T, Iimuro Y, Yamamoto Y et al. Small hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of radio-frequency ablation and percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy. Radiology. 2002;223(02):331–337. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2232010775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill I S, Remer E M, Hasan W A et al. Renal cryoablation: outcome at 3 years. J Urol. 2005;173(06):1903–1907. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158154.28845.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mack M G, Straub R, Eichler K et al. Percutaneous MR imaging-guided laser-induced thermotherapy of hepatic metastases. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26(04):369–374. doi: 10.1007/s002610000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davalos R V, Mir I L, Rubinsky B. Tissue ablation with irreversible electroporation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33(02):223–231. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8981-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Canfield S et al. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: 2014 update. Eur Urol. 2015;67(05):913–924. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson R H, Boorjian S A, Lohse C Met al. Radical nephrectomy for pT1a renal masses may be associated with decreased overall survival compared with partial nephrectomy J Urol 200817902468–471., discussion 472–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen D Y, Uzzo R G.Optimal management of localized renal cell carcinoma: surgery, ablation, or active surveillance J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2009706635–642., quiz 643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavlovich C P, Walther M, Choyke P L et al. Percutaneous radio frequency ablation of small renal tumors: initial results. J Urol. 2002;167(01):10–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang X, Zhang F, Liu T et al. Radio frequency ablation versus partial nephrectomy for clinical T1b renal cell carcinoma: long-term clinical and oncologic outcomes. J Urol. 2015;193(02):430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Psutka S P, Feldman A S, McDougal W S, McGovern F J, Mueller P, Gervais D A. Long-term oncologic outcomes after radiofrequency ablation for T1 renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2013;63(03):486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uppot R N, Silverman S G, Zagoria R J, Tuncali K, Childs D D, Gervais D A. Imaging-guided percutaneous ablation of renal cell carcinoma: a primer of how we do it. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(06):1558–1570. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gervais D A, Arellano R S, Mueller P R. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(05):960–967. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2651-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gervais D A, Arellano R S, McGovern F J, McDougal W S, Mueller P R. Radiofrequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma: part 2, Lessons learned with ablation of 100 tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185(01):72–80. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.1.01850072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg S N. Comparison of techniques for image-guided ablation of focal liver tumors. Radiology. 2002;223(02):304–307. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2232012152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg S N, Gazelle G S. Radiofrequency tissue ablation: physical principles and techniques for increasing coagulation necrosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48(38):359–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solbiati L, Ierace T, Goldberg S N et al. Percutaneous US-guided radio-frequency tissue ablation of liver metastases: treatment and follow-up in 16 patients. Radiology. 1997;202(01):195–203. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.1.8988211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gervais D A, McGovern F J, Arellano R S, McDougal W S, Mueller P R. Renal cell carcinoma: clinical experience and technical success with radio-frequency ablation of 42 tumors. Radiology. 2003;226(02):417–424. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2262012062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi S, Di Stasi M, Buscarini E et al. Percutaneous RF interstitial thermal ablation in the treatment of hepatic cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(03):759–768. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.3.8751696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zlotta A R, Wildschutz T, Raviv G et al. Radiofrequency interstitial tumor ablation (RITA) is a possible new modality for treatment of renal cancer: ex vivo and in vivo experience. J Endourol. 1997;11(04):251–258. doi: 10.1089/end.1997.11.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberg S N, Stein M C, Gazelle G S, Sheiman R G, Kruskal J B, Clouse M E. Percutaneous radiofrequency tissue ablation: optimization of pulsed-radiofrequency technique to increase coagulation necrosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10(07):907–916. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(99)70136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brace C L. Radiofrequency and microwave ablation of the liver, lung, kidney, and bone: what are the differences? Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2009;38(03):135–143. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong K, Georgiades C.Radiofrequency ablation: mechanism of action and devices J Vasc Interv Radiol 201021(8, Suppl):S179–S186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zagoria R J, Traver M A, Werle D M, Perini M, Hayasaka S, Clark P E. Oncologic efficacy of CT-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of renal cell carcinomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(02):429–436. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandharipande P V, Gervais D A, Mueller P R, Hur C, Gazelle G S. Radiofrequency ablation versus nephron-sparing surgery for small unilateral renal cell carcinoma: cost-effectiveness analysis. Radiology. 2008;248(01):169–178. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinshaw J L, Lubner M G, Ziemlewicz T J, Lee F T, Jr, Brace C L. Percutaneous tumor ablation tools: microwave, radiofrequency, or cryoablation--what should you use and why? Radiographics. 2014;34(05):1344–1362. doi: 10.1148/rg.345140054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldberg S N, Gazelle G S, Solbiati L, Rittman W J, Mueller P R. Radiofrequency tissue ablation: increased lesion diameter with a perfusion electrode. Acad Radiol. 1996;3(08):636–644. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(96)80188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf F J, Grand D J, Machan J T, Dipetrillo T A, Mayo-Smith W W, Dupuy D E. Microwave ablation of lung malignancies: effectiveness, CT findings, and safety in 50 patients. Radiology. 2008;247(03):871–879. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2473070996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Best S L, Park S K, Youssef R F et al. Long-term outcomes of renal tumor radio frequency ablation stratified by tumor diameter: size matters. J Urol. 2012;187(04):1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huffman S D, Huffman N P, Lewandowski R J, Brown D B. Radiofrequency ablation complicated by skin burn. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2011;28(02):179–182. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon C J, Dupuy D E, Mayo-Smith W W. Microwave ablation: principles and applications. Radiographics. 2005;25 01:S69–S83. doi: 10.1148/rg.25si055501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright A S, Sampson L A, Warner T F, Mahvi D M, Lee F T., Jr Radiofrequency versus microwave ablation in a hepatic porcine model. Radiology. 2005;236(01):132–139. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361031249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skinner M G, Iizuka M N, Kolios M C, Sherar M D. A theoretical comparison of energy sources--microwave, ultrasound and laser--for interstitial thermal therapy. Phys Med Biol. 1998;43(12):3535–3547. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/43/12/011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Organ L W.Electrophysiologic principles of radiofrequency lesion making Appl Neurophysiol1976-1977390269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu D S, Raman S S, Vodopich D J, Wang M, Sayre J, Lassman C. Effect of vessel size on creation of hepatic radiofrequency lesions in pigs: assessment of the “heat sink” effect. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178(01):47–51. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.1.1780047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed M, Brace C L, Lee F T, Jr, Goldberg S N. Principles of and advances in percutaneous ablation. Radiology. 2011;258(02):351–369. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10081634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabuse K. Basic knowledge of a microwave tissue coagulator and its clinical applications. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5(02):165–172. doi: 10.1007/s005340050028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brace C L. Microwave ablation technology: what every user should know. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2009;38(02):61–67. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Sun Y, Feng L, Gao Y, Ni X, Liang P. Internally cooled antenna for microwave ablation: results in ex vivo and in vivo porcine livers. Eur J Radiol. 2008;67(02):357–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winokur R S, Du J Y, Pua B B et al. Characterization of in vivo ablation zones following percutaneous microwave ablation of the liver with two commercially available devices: are manufacturer published reference values useful? J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25(12):1939–19460. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu J, Liang P, Yu X L et al. US-guided percutaneous microwave ablation versus open radical nephrectomy for small renal cell carcinoma: intermediate-term results. Radiology. 2014;270(03):880–887. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim C, O'Rourke A P, Mahvi D M, Webster J G. Finite-element analysis of ex vivo and in vivo hepatic cryoablation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54(07):1177–1185. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2006.889775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rewcastle J C, Sandison G A, Muldrew K, Saliken J C, Donnelly B J. A model for the time dependent three-dimensional thermal distribution within iceballs surrounding multiple cryoprobes. Med Phys. 2001;28(06):1125–1137. doi: 10.1118/1.1374246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rui J, Tatsutani K N, Dahiya R, Rubinsky B. Effect of thermal variables on human breast cancer in cryosurgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;53(02):185–192. doi: 10.1023/a:1006182618414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffmann N E, Bischof J C. The cryobiology of cryosurgical injury. Urology. 2002;60(02) 01:40–49. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atwell T D, Farrell M A, Callstrom M R et al. Percutaneous cryoablation of large renal masses: technical feasibility and short-term outcome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(05):1195–1200. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenberg M D, Kim C Y, Tsivian M et al. Percutaneous cryoablation of renal lesions with radiographic ice ball involvement of the renal sinus: analysis of hemorrhagic and collecting system complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(04):935–939. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kunkle D A, Uzzo R G. Cryoablation or radiofrequency ablation of the small renal mass : a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2008;113(10):2671–2680. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pech M, Janitzky A, Wendler J J et al. Irreversible electroporation of renal cell carcinoma: a first-in-man phase I clinical study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34(01):132–138. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knavel E M, Brace C L. Tumor ablation: common modalities and general practices. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16(04):192–200. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deodhar A, Dickfeld T, Single G W et al. Irreversible electroporation near the heart: ventricular arrhythmias can be prevented with ECG synchronization. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(03):W330-5. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wendler J J, Porsch M, Nitschke S et al. A prospective Phase 2a pilot study investigating focal percutaneous irreversible electroporation (IRE) ablation by NanoKnife in patients with localised renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with delayed interval tumour resection (IRENE trial) Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;43:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nicholson M L, Wheatley T J, Doughman T M et al. A prospective randomized trial of three different sizes of core-cutting needle for renal transplant biopsy. Kidney Int. 2000;58(01):390–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cantwell C P, Wah T M, Gervais D A et al. Protecting the ureter during radiofrequency ablation of renal cell cancer: a pilot study of retrograde pyeloperfusion with cooled dextrose 5% in water. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19(07):1034–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boss A, Clasen S, Kuczyk M et al. Thermal damage of the genitofemoral nerve due to radiofrequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma: a potentially avoidable complication. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185(06):1627–1631. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gervais D A, McGovern F J, Wood B J, Goldberg S N, McDougal W S, Mueller P R. Radio-frequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma: early clinical experience. Radiology. 2000;217(03):665–672. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.3.r00dc39665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farrell M A, Charboneau W J, DiMarco D S et al. Imaging-guided radiofrequency ablation of solid renal tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(06):1509–1513. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.6.1801509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goldberg S N, Hahn P F, Tanabe K Ket al. Percutaneous radiofrequency tissue ablation: does perfusion-mediated tissue cooling limit coagulation necrosis? J Vasc Interv Radiol 19989(1, Pt 1):101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.El Dib R, Touma N J, Kapoor A. Cryoablation vs radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of case series studies. BJU Int. 2012;110(04):510–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Atwell T D, Schmit G D, Boorjian S A et al. Percutaneous ablation of renal masses measuring 3.0 cm and smaller: comparative local control and complications after radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(02):461–466. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gervais D A, McGovern F J, Arellano R S, McDougal W S, Mueller P R. Radiofrequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma: part 1, Indications, results, and role in patient management over a 6-year period and ablation of 100 tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185(01):64–71. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.1.01850064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gupta A, Raman J D, Leveillee R J et al. General anesthesia and contrast-enhanced computed tomography to optimize renal percutaneous radiofrequency ablation: multi-institutional intermediate-term results. J Endourol. 2009;23(07):1099–1105. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brashears J H, III, Raj G V, Crisci A et al. Renal cryoablation and radio frequency ablation: an evaluation of worst case scenarios in a porcine model. J Urol. 2005;173(06):2160–2165. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158125.80981.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sung G T, Gill I S, Hsu T Het al. Effect of intentional cryo-injury to the renal collecting system J Urol 2003170(2, Pt 1):619–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thompson R H, Atwell T, Schmit G et al. Comparison of partial nephrectomy and percutaneous ablation for cT1 renal masses. Eur Urol. 2015;67(02):252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Campbell S C, Novick A C, Belldegrun A et al. Guideline for management of the clinical T1 renal mass. J Urol. 2009;182(04):1271–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kunkle D A, Egleston B L, Uzzo R G.Excise, ablate or observe: the small renal mass dilemma--a meta-analysis and review J Urol 2008179041227–1233., discussion 1233–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lorentzen T. A cooled needle electrode for radiofrequency tissue ablation: thermodynamic aspects of improved performance compared with conventional needle design. Acad Radiol. 1996;3(07):556–563. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(96)80219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arata M A, Nisenbaum H L, Clark T W, Soulen M C. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of liver tumors with the LeVeen probe: is roll-off predictive of response? J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12(04):455–458. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61884-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haemmerich D, Staelin S T, Tungjitkusolmun S, Lee F T, Jr, Mahvi D M, Webster J G. Hepatic bipolar radio-frequency ablation between separated multiprong electrodes. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2001;48(10):1145–1152. doi: 10.1109/10.951517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haemmerich D, Chachati L, Wright A S, Mahvi D M, Lee F T, Jr, Webster J G. Hepatic radiofrequency ablation with internally cooled probes: effect of coolant temperature on lesion size. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2003;50(04):493–500. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.809488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lu M D, Chen J W, Xie X Y et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: US-guided percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy. Radiology. 2001;221(01):167–172. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2211001783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Edge S B, Compton C C. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(06):1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.MacLennan S, Imamura M, Lapitan M C et al. Systematic review of oncological outcomes following surgical management of localised renal cancer. Eur Urol. 2012;61(05):972–993. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Whitson J M, Harris C R, Meng M V.Population-based comparative effectiveness of nephron-sparing surgery vs ablation for small renal masses BJU Int 2012110101438–1443., discussion 1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stern J M, Svatek R, Park S et al. Intermediate comparison of partial nephrectomy and radiofrequency ablation for clinical T1a renal tumours. BJU Int. 2007;100(02):287–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schmit G D, Thompson R H, Kurup A N et al. Usefulness of R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry scoring system for predicting outcomes and complications of percutaneous ablation of 751 renal tumors. J Urol. 2013;189(01):30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Canter D, Kutikov A, Manley B et al. Utility of the R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry scoring system in objectifying treatment decision-making of the enhancing renal mass. Urology. 2011;78(05):1089–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kutikov A, Smaldone M C, Egleston B L et al. Anatomic features of enhancing renal masses predict malignant and high-grade pathology: a preoperative nomogram using the RENAL Nephrometry score. Eur Urol. 2011;60(02):241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bruner B, Breau R H, Lohse C M, Leibovich B C, Blute M L. Renal nephrometry score is associated with urine leak after partial nephrectomy. BJU Int. 2011;108(01):67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Simhan J, Smaldone M C, Tsai K J et al. Objective measures of renal mass anatomic complexity predict rates of major complications following partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol. 2011;60(04):724–730. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]