Abstract

The patient portal, increasingly available to patients, allows secure electronic communication with physicians. Although physician attitude toward the portal plays a crucial role in patient adoption, little information regarding physician opinion of the portal is available, with almost no information gathered in the pediatric environment. Using mixed-methods, physicians in a large pediatric medical facility and integrated delivery network were surveyed using an online quantitative questionnaire and structured interviews. Physicians reported the portal’s role in more communication efficiency for patients, parents, and providers. The portal’s acceptance also introduces new challenges such as frequent questions from some parents and medical visit avoidance.

Keywords: patient portal, electronic health record (EHR), technology adoption, meaningful use, physician perception, health information technology, pediatrics, patient engagement

The patient portal, a secure website integrated with the Electronic Health Record (EHR), is designed to give patients secure access to health information and to permit protected methods for communication with their health care providers. Encouraging patients to communicate and to access personal health information such as progress notes, problem lists, current medications, immunization history, laboratory data, and radiology reports, as well as to be able to schedule appointments; request prescription refills; and pay bills is designed to enhance patient satisfaction, improve care, and make care more efficient (Bourgeois, Taylor, Emans, Nigrin, and Mandl, 2008; Byczkowski, Munafo, and Britto, 2014; Emont, 2011; Fiks, Myne, Karavite, DeBartolo, and Grundmeier, 2014; Goldzweig et al., 2013; Stinson et al., 2010; Zomer-Kooijker, van Erp, Balemans, van Ewijk, and van der Ent, 2013).

Changes in health care policy, namely Meaningful Use, seek to use certified EHR technology to: improve quality, safety, efficiency, and reduce health disparities, as well as to engage patients and family, while maintaining privacy and security of patient health information (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). The patient portal is one of the interfaces that will allow patients to have access to their health information so they can participate in the shared decision making process with their clinicians.

More than half of the pediatric patient portal research to date has been focused on chronic disease patients and their parents including management of diabetes mellitus, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, cystic fibrosis, asthma, and other unspecified chronic diseases (Britto et al., 2009; Britto, Hesse, Kamdar, and Munafo, 2013; Byczkowski, Munafo, and Britto, 2011; Byczkowski et al., 2014; Fiks et al., 2014; Shaw and Ferranti, 2011; Tom, Mangione-Smith, Solomon, and Grossman, 2012). The studies have been small in size, generally conducted in academic institutions, and relied on parental rather than patient input (Bush, Connelly, Fuller, and Pérez, 2015). There are very limited data on the use of the portal in teenagers given the issue of the desire for teenager confidentiality versus parental access, which has been seen a barrier to teenage use (Bergman, Brown, and Wilson, 2008; Bourgeois et al., 2008; Britto, Tivorsak, and Slap, 2010; Byczkowski et al., 2014; Hannan, 2010).

While it has been established that physicians have struggled with EHR implementation and the use of the EHR with patient care, resulting in dissatisfaction (Weeks, Keeney, Evans, Moore, and Conrad, 2014; Porter, 2013; Meigs and Solomon, 2016), little is known regarding attitudes of physicians toward electronic portals, with almost no information gathered in the pediatric environment (Keplinger et al., 2013). Since physician perception of and attitude toward the portal plays a crucial role in patient adoption of the portal, it is important to measure these perceptions (Keplinger et al., 2013), and to identify potential concerns or reluctance to adopt the portal within clinical workflow.

The purpose of this mixed-methods study was to increase the understanding of physician perceptions regarding the value of the patient portal in the pediatric environment. The primary aims were to capture physicians’ perceptions regarding their experiences with portal implementation and the impact on their clinical workflow.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

This study used a mixed-methods approach, recruiting physicians from a 520-bed tertiary academic pediatric facility and its integrated pediatric medical system, which serves two counties in southern California. The health system uses the Epic (Madison, WI) EHR, including the patient portal application MyChart. At the time of the study, parents had full access to their child’s record, including those of teenagers through the age of 17; teenagers did not have access except as permitted by their parents.

Following institutional humans subjects approval, the researchers distributed a link to Survey Gizmo (Boulder CO) via the medical practice email distribution list inviting physicians to complete a quantitative online survey and a qualitative telephone interview. The questions were developed using information from the literature review and instruments developed by Bergman et al. (2008) and Ahlers-Schmidt and Nguyen (2013) to examine the role of the patient portal. The data elicited data regarding provider attitudes, perceptions, and responsibilities surrounding their use of the portal, as well as providing a forum to address issues with and potential improvements for incorporation of the patient portal into clinical workflows.

Part one of the questionnaire quantified demographics (4 questions); attitude toward technology adoptions (respondent’s type and frequency of social medial use); and number of emails, telephone calls, and secure messages received monthly from patients to approximate practice volume. Part two consisted of 15 questions with a 5-item Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree to capture responders’ perceptions of the effect of the portal on workload, telephone calls, patient satisfaction, number of patient visits, patient quality of care, treatment compliance, professional satisfaction, and impact on clinical income. Questions also captured workflow modification impact including: ease of incorporating the portal in workflow; using the portal for patient communication and questionnaire completion; medication refills; scheduling appointments; and check medical records. A stand-alone question asked if teenagers should have full access to the patient portal. Three open-ended questions asked: “What effects have you seen in practice following implementation of MyChart?”; “What else should we know?”; and “Would you be willing to participate in a telephone interview?” Responses could be anonymous.

Among those physicians indicating interest, semi structured interviews, which contained questions about physicians’ perceptions of the use, benefits and drawbacks, success stories, issues, and future directions of the online portal MyChart were conducted. Initial development of the topic areas included a review of the literature of use of the portal in pediatric practices. Previously reported strengths and weaknesses of the patient portal for children and provided the foundation for interview (Ahlers-Schmidt and Nguyen, 2013; Bergman et al., 2008; Byczkowski et al., 2011; Ketterer et al., 2013).

Data Analysis

Survey responses were downloaded from the internet survey repository into Microsoft Excel (2010), verified, and exported to IBM SPSS software version 23.0 for analysis. The frequency distributions of participant characteristics, as well as perceptions, were calculated and evaluated by gender, age, and social media usage using Chi-square tests or Fisher's exact tests for categorical data. The five-point scale was condensed into disagree, neutral, and agree.

Each interview was transcribed verbatim and then independently analyzed by two of the investigators (R. B. and A. P.) to identify themes that emerged from the transcripts. Segments of transcripts ranging from a phrase to several paragraphs were assigned codes based on a priori (i.e. based on questions in the interview guide) or emergent themes. The same two study team members then met to review their findings. Identified themes showed high concurrence between the investigators. Themes were compared to look for trends.

Results

Quantitative Results

The analysis included 21 providers: 12 pediatricians and 9 specialists. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the physicians participating in this study, including gender, age, years in clinical practice, specialty, and social media use frequency. Survey respondents were evenly divided between males and females, reporting a mean of 18 years in practice (SD = 12.1), and a mean age of 49.2 (SD = 12.0).

Table 1.

Participant Profile (N = 21)

| Characteristic | n | % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years in Practice | 18.0 | 12.1 | ||

| Age in Years (continuous) | 49.2 | 12.0 | ||

| Under 50 | 11 | 54 | ||

| 50 or over | 10 | 48 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 11 | 54 | ||

| Male | 10 | 48 | ||

| Provider | ||||

| Pediatrician | 12 | 57 | ||

| Specialty | 9 | 43 | ||

| Social Media | ||||

| Never/Infrequent | 9 | 43 | ||

| Frequent | 12 | 57 |

Note. M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation.

The provider view of the portal applications and their impact on patients was generally favorable. The portal’s role in communication of health issues (80%) and the use of the portal for medication refills (62%) were positive. Notable, 72% were neutral as to whether it was easy to enroll patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perception of Portal Use by Patients.

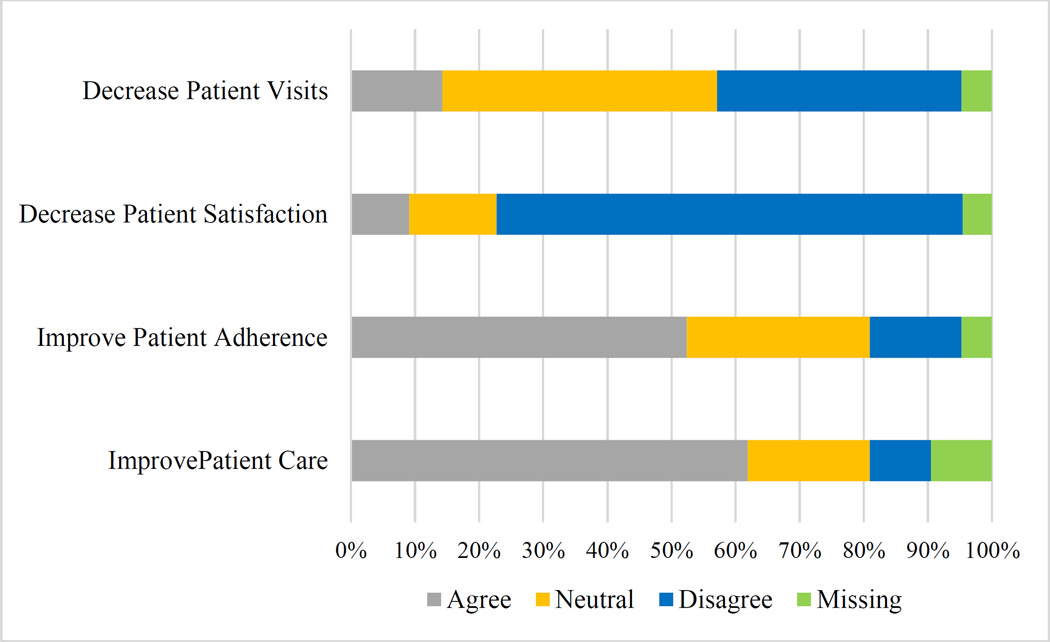

Providers were even more positive about their perceived comprehensive impact of the portal on patient care. The respondents were particularly enthusiastic about their believe that it improved patient care (60%); and that it improved patient adherence (52%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Perceived Impact on General Patient Care.

The providers were also generally pleased with impact on their clinical role. They did not note a negative impact on their salary and 80% found that implementation of the portal had reduced the number of telephone calls they received. Their most negative response was that 43% believed it has increased work load (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Impact of Portal on Physician Workflow.

Qualitative Analysis

Six physicians (4 female) participated in the qualitative interviews. Three were specialists, 2 pediatricians, and one was a hospitalist. Five of the six had a long time association with the health care system and been present for all phases of the EHR implementation. The primary themes that emerged from the qualitative interviews were:

Portal use varies by setting and family

The user profile varies by setting and demographics. Primary care pediatricians noted much greater use of the portal, reporting as many as half of their patient parents used the application and several physicians noted that the portal was not currently set up to receive inpatient data so would not be of use during hospitalizations. Specialists reported fewer than 20% using the portal for their children’s care. Users tend to be younger parents, have access to a home computer, and are already “notebook” keepers who are more engaged in their children’s healthcare. They are also more likely to have a child with an ongoing medical condition or chronic condition necessitating coordination of care. The providers noted that access to the computer is important as the portal application is challenging to use on a smartphone. All reported the most common use of the portal was for parents to send secure messages to their children’s providers.

Portal recruitment approaches

The portal will not impact patient care unless patients are aware of the portal and are registered to use it. Respondents noted, finding the correct patient education technique and registration approach with minimal workflow disruption and reduced clinical productivity has been an obstacle in adopting the patient portal. The respondents reported a variety of ways that recruitment for the portal had taken place including recruitment mailers; inviting participation at appointment check in; sending information home at check out; placing dedicated computers in the waiting room; and enrolling patients during clinic visits using the EHR computer in the examination area. The enrollment during the patient visit provided the best opportunity for conveying the importance of the portal and its role in physician–patient interaction, but does contribute to workflow disruption and is added work for the physician. Those physicians enrolling their patients as part of the appointment reported much higher participation and more frequent interaction with their patients via the portal. There was general agreement that patients were loss to enrollment if not registered during the medical appointment.

Improved patient communication

Providers viewed improved patient communication as greatest portal benefit. All noted the reduction in “telephone tag” and the time no longer spent returning missed telephone calls. Additionally, they were not limited to contacting patients only during the time when a family is home or near a telephone, returning messages later at night or early in the morning. Providers welcomed the use of written communication, which they felt was less easily misinterpreted than oral instructions. Moreover, for many of the patients families whose primary language is not English, written communication allowed the provider to provide precise instructions or advice that could then be more easily translated by a family member rather than conveying important information over the telephone after either 1) waiting for interpreter services or 2) requiring a language for which an interpreter is not easily available. Several providers noted success stories in which the secure written communication permitted families to more closely follow a treatment protocol or to avoid unnecessary trips to the physician. Keeping well patients away from waiting rooms was noted as particularly important for newborns and infants during flu season and more recently, in Southern California, the measles outbreak. One respondent noted, “while he felt communication with the physician was much improved using the portal, he was concerned that the remainder of the care team was not as much ‘in the loop’ as they had been before portal implementation.” He expressed concern that “previously the nurses with whom he worked were more involved in the triage process and knew more about the patients, whereas now it was almost exclusively patient-physician.” He was investigating modification of the settings of the secure communication protocol to incorporate other clinicians in his practice into the messaging system.

Complicated patients

The enhanced availability and access to health data, as well as increased efficiency in delivering care, was generally felt to be improving the quality of care provided to the patients. Physicians noted that for complicated patients, the portal especially facilitated shared communication among care team. The ability to share reports and images not only among the clinical staff but also with patients, including parents, allowed all the members of a care team to receive paid delivery of results, base decision on the same information, reduce unnecessary tests, and other repeated procedures.

Teens and the patient portal

Respondents generally supported full and secure teenage-only access to teenage patient information. They believe the digital interaction of secure messaging and filling out forms within a confidential environment would increase the number of questions teenagers will ask and provide needed health education that may not currently be taking place. Digital interaction might allow teens to “discuss” uncomfortable situations without making eye contact. While welcoming the opportunity to allow teens to have the access, several providers questioned whether teens would embrace the opportunity to become more involved in their own health care.

Challenges

While the general experience with the portal, to date, has been generally positive for the respondents, there have been challenges. Some of the issues have been with the logistics of the portal registration and interface. The current version of the system requires computer access for initial registration; many families’ only internet connection comes from using their smartphones, so clinics must make sure computers are available for registration. Additionally, the application has many screens and may require up to four or five clicks to get to the screen of interest, making the interface difficult to navigate. Updating calendars and scrolling through recent appointments can be difficult, especially if the child is receiving multiple treatments or is seeing several providers. As one respondent noted, “four clicks matter.” Although many results are available via the portal, nonstandard reports, such as genetic information or non-standard labs are not. A telephone call and hard copy reporting must still take place for those patients.

The portal is also impacting clinical workflow and work/life balance. While the number of telephone calls has been reduced, there is an increased administrative workload associated with secure communication and 4 of 6 noted a significant “creep” in the amount of time spent out of the office replying to messages. Physicians noted there are some parents who communicate several times a week or even daily about issues that are not time sensitive or have already been answered during appointments. Other parents use the secure communication for medical visit avoidance, circumventing a copayment, or incurring the cost of a visit. Several physicians noted the avoidance may be reduced following upcoming clarification regarding what constituted an e-visit and the ability to bill for such encounters. They also noted as they have become more efficient in their communication, there are now greater expectations among the parents. Parents now expect responses within two or three hours; some expect a response in minutes rather than a message returned within 24 hours. Several shared parents being upset about not receiving returned messages during the time the physician was in clinic physically seeing other patients. Respondents noted boundaries of when they were and were not at work were becoming blurred as they found themselves communicating with parents several hours every evening at home.

Discussion

The results of this study reinforced much of the initial research about the pediatric patient portal. Portal users have a different profile than non-users. The physician participants in this study reported younger parents who were more computer savvy were likely have a portal account. While other studies have reported individuals of color and those with Medicaid or who were low income were less likely to obtain a portal account (Byczkowski et al., 2011; Ketterer et al., 2013), the participants in this study identified a potential distinction that the issue is not necessarily a lack of technical knowledge among the less educated or lower income patients but the subtlety that because a computer is required for registration and a computer screen rather than a phone screen permits ease of interaction, the issue is one of logistics. This study also supports the finding parents of chronically ill children are more likely to use the portal to help them communicate with their children’s care provider, as well as to manage and understand child’s condition (Britto et al., 2013; Byczkowski et al., 2014).

Both results from the survey and the interviews described the evolving pattern that parents use the portal to communicate but the portal has not replaced telephone calls. In fact, physicians now have multiple sources of messages to return (Byczkowski et al., 2014). Security and privacy were not overwhelming issues, unless it was in the context of adolescent access to a patient portal and what they and their parents might see. Although not the primary topic of interest of the majority of the studies to date, the issue regarding adolescent access to their medical records is still to be resolved (Bergman et al., 2008; Hannan, 2010).

This research has several potential limitations. First, the sample for this study consisted of a limited convenience sample in an academic setting, which may limit transferability of study findings to other clinical practices and other geographic regions of the country. Second, the sample for this study was relatively small (n = 21), thereby limiting generalizability. Although this sample was small, many of the findings were in agreement with previous studies from the patient or parent perspective. Third, data collected in this study were self-reported, which introduces potential bias.

Implementation of the portal is generally positive with both physicians and patients noting improvements in care. The transformation of communication modality and the expectation for message frequency is making an impact on workflow; addressing the impact on time and negotiating boundaries will need to continue to evolve as portal usage increases.

Conclusion

Use of the patient portal has brought more communication efficiency for patients, parents, and providers. The portal’s success also introduces new challenges, such as frequent questions from some parents, and medical visit avoidance; and more communication efficiency results in greater expectations. Providers generally support teenage provider access and note the digital interaction may permit discussing uncomfortable situations with less embarrassment. Future focus areas include expanding patient/family enrollment and increasing dissemination of education. Noted barriers to portal implementation can now be addressed with readjusted clinical workflow approaches.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: Research supported in part by K99/R00 HS022404 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

To the best of our knowledge, no conflict of interest, financial or other, exists.

References

- Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Nguyen M. Parent intention to use a patient portal as related to their children following a facilitated demonstration. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association. 2013;19(12):979–981. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman DA, Brown NL, Wilson S. Teen use of a patient portal: a qualitative study of parent and teen attitudes. Perspectives in Health Information Management. 2008;5:13. Retrieved from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2556441&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois FC, Taylor PL, Emans SJ, Nigrin DJ, Mandl KD. Whose personal control? Creating private, personally controlled health records for pediatric and adolescent patients. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2008;15(6):737–743. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto MT, Hesse EA, Kamdar OJ, Munafo JK. Parents’ perceptions of a patient portal for managing their child's chronic illness. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;163(1):280–281.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto MT, Jimison HB, Munafo JK, Wissman J, Rogers ML, Hersh W. Usability testing finds problems for novice users of pediatric portals. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2009;16(5):660–669. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto MT, Tivorsak TL, Slap GB. Adolescents’ needs for health care privacy. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):e1469–e1476. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush RA, Connelly CD, Fuller M, Pérez A. Implementation of the integrated electronic patient portal in the pediatric population: a systematic review. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association. 2015 doi: 10.1089/tmj.2015.0033. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byczkowski TL, Munafo JK, Britto MT. Variation in use of internet-based patient portals by parents of children with chronic disease. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(5):405–411. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byczkowski TL, Munafo JK, Britto MT. Family perceptions of the usability and value of chronic disease web-based patient portals. Health Informatics Journal. 2014;20(2):151–162. doi: 10.1177/1460458213489054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emont S. Measuring the impact of patient portals: what the literature tells us. 2011 Retrieved from California Health Care Foundation website: http://www.chcf.org/publications/2011/05/measuring-impact-patient-portals.

- Fiks AG, Mayne S, Karavite DJ, DeBartolo E, Grundmeier RW. A shared e-decision support portal for pediatric asthma. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2014;37(2):120–126. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldzweig CL, Orshansky G, Paige NM, Towfigh AA, Haggstrom DA, Shekelle PG. Electronic patient portals: evidence on health outcomes, satisfaction, efficiency, and attitudes: a systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;159(10):677–687. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan A. Providing patients online access to their primary care computerised medical records: a case study of sharing and caring. Informatics in Primary Care. 2010;18(1):41–49. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v18i1.752. Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20429977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keplinger LE, Koopman RJ, Mehr DR, Kruse RL, Wakefield DS, Wakefield BJ, Canfield SM. Patient portal implementation: resident and attending physician attitudes. Family Medicine. 2013;45(5):335–340. Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23681685. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketterer T, West DW, Sanders VP, Hossain J, Kondo MC, Sharif I. Correlates of patient portal enrollment and activation in primary care pediatrics. Academic Pediatrics. 2013;13(3):264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meigs S, Solomon M. Electronic health record use: a bitter pill for many physicians. Perspectives in Health Information Management. 2016;13 Retrieved from: http://perspectives.ahima.org/electronic-health-record-use-a-bitter-pill-for-many-physicians/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter S. Family physicians provide feedback on electronic health records in FPM’S user satisfaction survey. Annals of Family Medicine. 2013;11(1):84–85. doi: 10.1370/afm.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ, Ferranti J. Patient-provider internet portals--patient outcomes and use. Computers, Informatics, Nursing: CIN. 2011;29(12):714–718. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e318224b597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson J, McGrath P, Hodnett E, Feldman B, Duffy C, Huber A, White M. Usability testing of an online self-management program for adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2010;12(3):e30. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom JO, Mangione-Smith R, Solomon C, Grossman DC. Integrated personal health record use: association with parent-reported care experiences. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):e183–e190. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Meaningful use definition and meaningful use objectives of EHRs. 2015 Retrieved from HealthIT.gov website: https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/meaningful-use-definition-objectives.

- Weeks DL, Keeney BJ, Evans PC, Moore QD, Conrad DA. Provider perceptions of the electronic health record incentive programs: a survey of eligible professionals who have and have not attested to meaningful use. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;30(1):123–130. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3008-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zomer-Kooijker K, van Erp FC, Balemans WAF, van Ewijk BE, van der Ent CK. The expert network and electronic portal for children with respiratory and allergic symptoms: rationale and design. BMC Pediatrics. 2013;13:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]