Abstract

Aims

The goals of this study are to determine if there is (a) a threshold effect for prenatal tobacco exposure (PTE) on adolescent risk for nicotine dependence, and (b) an additive effect of PTE and maternal postnatal nicotine dependence on adolescent risk for nicotine dependence.

Methods

Pregnant women were recruited in their 4th or 5th gestational month and asked about cigarette use during the first trimester. Mothers reported on third trimester cigarette use at delivery. Sixteen years post-partum, mothers and offspring reported on current levels of cigarette use (N = 784). Nicotine dependence was assessed in both using a modified Fagerstrom questionnaire.

Results

Based on the results of a threshold analysis for PTE, four groups were created: threshold PTE only (10+ cigarettes per day), maternal nicotine postnatal dependence with no-low PTE (0–<10 cigarettes per day), threshold PTE + maternal postnatal nicotine dependence, and a referent group with no-low PTE and no maternal postnatal nicotine dependence. Adolescents in the PTE-only group and the PTE + maternal postnatal nicotine dependence group were significantly more likely to be at risk for nicotine dependence than the offspring from the referent group. However, there was no evidence for an additive effect of maternal postnatal nicotine dependence, and maternal nicotine dependence was not a significant predictor of adolescent risk for nicotine dependence in regression models including prenatal tobacco exposure.

Conclusions

Bivariate analysis revealed a threshold effect for PTE of 10 cigarettes per day. In multivariate analysis, PTE remained significantly related to risk for offspring nicotine dependence, after controlling for maternal postnatal nicotine dependence and other covariates associated with adolescent cigarette use.

Keywords: prenatal tobacco exposure, nicotine dependence, adolescence, smoking, pregnancy

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Over a third of all adolescents in the U.S. try smoking, and at least one-fifth of those who experiment with cigarettes will develop nicotine dependence (ND) (Colby et al., 2000; Dierker et al., 2012). Parental smoking is a well-known predictor of adolescent smoking and ND (Gilman et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2012; Kandel et al., 2007, 2015; Mays et al., 2014; Selya et al., 2012; Weden & Miles, 2012). However, many adolescents whose parents currently smoke also have prenatal tobacco exposure (PTE). Offspring with PTE are more likely to smoke than unexposed offspring (Agrawal et al., 2010; Cornelius et al., 2000, 2005; Goldschmidt et al., 2012; Weden & Miles, 2012) and to progress from smoking to ND (Buka et al., 2003; Rydell et al., 2012; Shenassa et al., 2015). Preclinical studies provide a plausible biological mechanism for the effects of PTE on ND: PTE rodents respond differently to nicotine administration and withdrawal during adolescence than unexposed rodents (Slotkin et al., 2006).

Of note, prior studies of the effects of PTE on ND in humans did not focus on the effects of maternal postnatal ND in their models. PTE and maternal postnatal ND may represent separate pathways to ND in adolescents. PTE may have a teratological effect, priming exposed offspring to become smokers and then dependent smokers by sensitizing them to the effects of nicotine at smoking initiation (Bidwell et al., 2016; Pomerleau, 1995). There may also be indirect teratogenic effects of PTE on ND in adolescents via attention and behavior problems (Clark et al., 2016; Cornelius et al., 2007, 2011; Day et al., 2000) that promote disengagement at school, antisocial peer relations and daily smoking. On the other hand, PTE may simply be a marker for maternal postnatal ND (Agrawal et al., 2008) or genetic and environmental influences (Rydell et al., 2016). In addition, dependent mothers are more likely to continue smoking during pregnancy, exposing the offspring to higher levels of tobacco.

To date, most research on ND has focused on the effects of PTE or maternal postnatal ND separately. Only one study previously took into account both exposures, by including a retrospective report of PTE as a covariate. In this study, Kandel and colleagues (2007) found that maternal postnatal ND, but not PTE, predicted ND in smoking adolescents. This study merits replication because it was a small community sample (353 students in Chicago public schools) and the measure of PTE was a retrospective caregiver’s report of any smoking by the adolescent’s biological mother at any point during the pregnancy. The goals of this study are to use prospective birth cohort data to determine if there is (a) a threshold effect for PTE on adolescent risk for ND, using a prospective measure of PTE for each trimester of pregnancy, and (b) an additive effect of PTE and maternal postnatal ND on adolescent risk for ND.

2. Method

2.1 Design

Pregnant girls and women were recruited in their 4th or 5th prenatal month from a teaching hospital in Pittsburgh, PA. They were seen again with their offspring at delivery and 6, 10, 14, and 16 years post-partum. At the 16-year follow-up visit, nicotine dependence (ND) was assessed in mothers and adolescent offspring.

2.2 Participants

The mothers in this study were recruited for three birth cohorts from a consortium of studies on the effects of prenatal substance use on physical and neurobehavioral development. Participants were from two studies of pregnant adults (AA06390; DA03874: PI Day) recruited from 1982–1985 and one study of pregnant adolescents recruited from 1990–1995 (DA09275: PI Cornelius). A new dataset combining the birth cohorts was created for the purposes of this study. The participants were drawn from the same prenatal clinic, seen at same follow-up time periods, and the same measures and personnel were used, so we avoid most sources of between-subject heterogeneity in the merged dataset (Curran and Hussong, 2009).

At birth, the combined sample size was 1,176 mothers. By the 16-year follow-up, 103 offspring were lost to follow up, 67 refused participation, 13 children had died, 15 were adopted or in foster care, and 52 had moved out of the area. Ten adolescents did not complete the drug assessment at age 16, and 27 caregivers were not assessed. We also excluded 105 dyads because the biological mother was not interviewed at the last follow-up. Complete data on ND in both biological mother and child were available for 784 dyads. This sample differed from the birth sample by race and PTE. The analyses were repeated with sampling weights, to adjust for attrition and to examine whether the results remained stable. The weights were calculated as the inverse probability of response for each racial group and tobacco exposure group. The results of the analyses were the same with and without the sampling weights, so unweighted values are presented for ease of interpretation.

2.3 Measurements

Prenatal tobacco exposure

Pregnant mothers were first interviewed in their 4th or 5th prenatal month in a private setting in the prenatal clinic by female interviewers who were comfortable discussing tobacco, alcohol and drug use. Quantity and frequency of cigarette use during the first trimester were assessed in this interview. Mothers were interviewed again within 48 hours of delivery, reporting on 3rd trimester cigarette use. About half of the mothers smoked during pregnancy (48% during the first trimester, 52% by the third trimester). The increase in smoking during pregnancy in the combined sample was influenced by the inclusion of a large number of adolescent mothers in the study, because smoking increased across pregnancy in this younger group (Cornelius et al., 1994; 2001). In comparison, among the adult-aged mothers, smoking prevalence was more stable across pregnancy (Cornelius et al., 2007).

Maternal postnatal nicotine dependence

Mothers were interviewed about their cigarette use 16 years post-partum, and also completed the 6-item Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton et al., 1991). Similar to other epidemiological studies (e.g., Azagba & Asbridge, 2013; Breslau & Johnson, 2000) ND was coded for mothers endorsing at least 4 items on the FTND.

Adolescent offspring risk for nicotine dependence

Offspring were also interviewed about their substance use 16 years post-partum. Adolescent ND was assessed in offspring who had ever tried cigarettes via the FTND questionnaire. A score of 4 on this scale indicates moderate dependence (Prokhorov et al., 2001). Adolescent offspring who scored 3 or higher were considered at risk of ND (outcome variable).

Covariates

Characteristics associated with smoking in previous research (including child age, race, maternal education, and prenatal exposure to alcohol and marijuana) were included in all of the multivariate analyses as covariates. Child sex was also included in preliminary analyses.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Bivariate analyses were first used to examine whether there was a linear relationship between PTE and adolescent ND. Next, a logistic regression was used to test whether PTE was a significant predictor of adolescent ND controlling for race, prenatal exposure to alcohol and marijuana, maternal education and child age at the 16-year assessment. In the second step of the regression, maternal postnatal ND was added to the model and the change in the relation between PTE and adolescent risk for ND was observed. In the last step, we introduced an interaction term to test whether the influence of PTE on adolescent risk for ND was sex-specific.

To determine if there was an additive effect of PTE and maternal postnatal ND, a separate analysis was conducted using the following four exposure groups: PTE only (at the threshold of 10+ cigarettes per day), maternal postnatal ND + no-low PTE (0 < 10 cigarettes/day), PTE + maternal postnatal ND (adolescents with both exposures), and a referent group with no maternal postnatal ND and no-low PTE (0 ≤10 cigarettes per day). Adolescent risk for ND in the reference group was first compared to adolescent risk for ND in the three exposure groups using a χ2 test. Logistic regression was then applied to simultaneously compare adolescent risk for ND in the PTE and maternal ND/low-no PTE groups relative to the reference group, controlling for demographic covariates. Finally, to test whether the effects of PTE and maternal postnatal ND were additive, adolescent risk for ND in the PTE + ND group relative to the PTE only and the ND/low-no PTE groups was compared.

3. Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

On average, the pregnant mothers were young (M = 20.6 years, SD = 4.6, range = 13–42) single mothers (65%). The sample was 61% Black and 39% White. At the 16-year follow up, 92% of the mothers had completed high school/GED (M = 12.5 years of education, SD = 1.9). Monthly family income ranged from 0–18,000 US$ (M = 2,198, SD = 1,741). More than half of the mothers were current smokers 16 years post-partum (55%), and 25% of mothers in the study were ND. Maternal postnatal ND was significantly correlated with maternal number of cigarettes smoked daily (r = 0.48). Paternal ND was not assessed in this study.

Adolescent offspring (half female) were 16.7 years on average (SD = 0.66, range = 16–19) and 39% had tried smoking. One in five of all the adolescent offspring was a current smoker (M = 6.3 cigarettes/day, SD = 6.8, range = 0.01–40). Thirty-six percent of the adolescent smokers were at risk for ND, endorsing at least 3 symptoms on the FTND. Child sex was not associated with being a smoker or with being at risk for ND. The correlation between number of cigarettes smoked daily and risk for ND in adolescents was statistically significant (r = 0.70).

3.2 Bivariate analysis

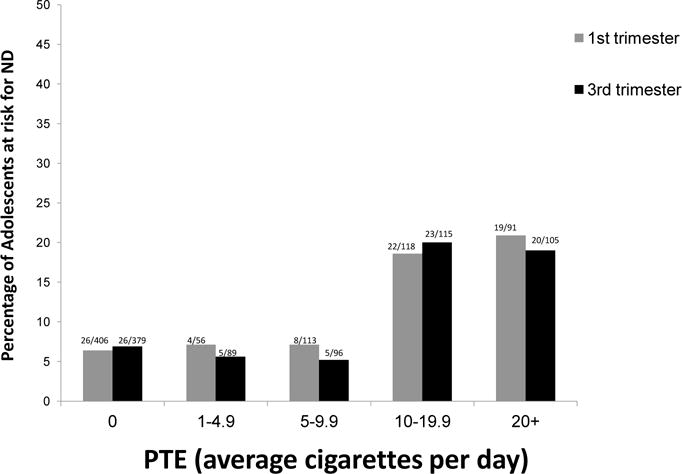

Figure 1 depicts the proportions of adolescent risk for ND as a function of level of PTE (average cigarettes per day during the first and third trimesters). There was a threshold effect at a half pack of cigarettes per day, with roughly 20% of adolescents exposed at this level at risk for ND 16 years later. The percentages of adolescents at risk for ND at lower levels of exposure were similar to non-exposed adolescents. Based on this pattern, the measure of PTE was dichotomized into two categories (0–<10 cigarettes/day and ≥10 cigarettes/day) to increase statistical power of testing.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Adolescents at risk for Nicotine Dependence (ND) as a function of Prenatal Tobacco Exposure (PTE)

Adolescents whose mothers smoked at least 10 cigarettes daily during the first trimester of pregnancy were significantly more likely to be at risk for ND at 16 years post-partum than adolescents with less or no PTE (OR = 3.45, CI = 2.15–5.54, χ2 = 25.5 p < 0.001). A similar pattern was identified for third trimester PTE (OR= 3.56, CI=2.2–5.7, p < 0.001). Adolescent risk for ND was also related to postnatal maternal ND (OR = 2.2, 95% CI = 1.35–3.55, χ2 =9.7, p < 0.005).

3.3 Multivariate analyses

Table 1 illustrates the results of the logistic regression analysis with first trimester PTE. PTE (≥ 10) was significantly related to adolescents’ ND, controlling for maternal race, exposure to other prenatal substances and child age at the last follow-up phase. Maternal postnatal ND did not significantly improve the chi-square for model fit, once PTE and other significant covariates were considered (χ2 = 1.5, p = 0.2). Results were essentially the same for third trimester PTE, with an AOR of 1.8 (CI = 1.04–3.16) in the last step of the equation. None of the interaction terms were significant, indicating that the results of PTE were not sex-specific.

Table 1.

Regression model predicting Adolescent Nicotine Dependence

| Coefficient | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||

| First trimester PTE ≥ 10 | 1.24 | 3.45 | 2.15–5.54 |

| Third trimester PTE ≥ 10a | 1.3 | 3.56 | 2.22–5.73 |

| Step 2 | |||

| Maternal race (White) | 1.18 | 3.25 | 1.87–5.67 |

| Adolescent age | 0.44 | 1.55 | 1.10q–2.16 |

| First trimester PTE ≥ 10 | 0.73 | 2.07 | 1.23–3.50 |

| Third trimester PTE ≥ 10 | 0.78 | 2.18 | 1.27–3.67 |

| Step 3 | |||

| Maternal race (White) | 1.18 | 3.26 | 1.87–5.68 |

| Adolescent age | 0.43 | 1.53 | 1.09–2.15 |

| Maternal postnatal ND | 0.35 | 1.42 | 0.82–2.47 |

| First trimester PTE ≥ 10 | 0.59 | 1.81 | 1.02–3.19 |

| Third trimester PTE ≥ 10 | 0.59 | 1.81 | 1.04–3.16 |

Analyses were run separately by trimester, but shown together for ease of presentation.

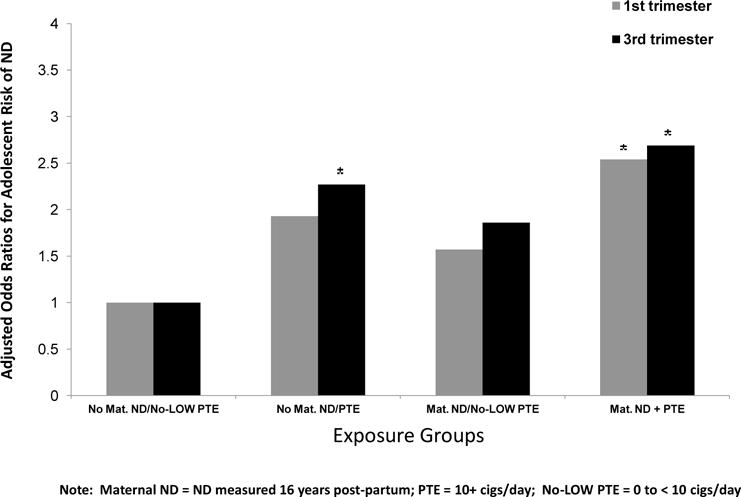

A separate analysis was conducted to determine if there was an additive effect of PTE and maternal postnatal ND on adolescent risk for ND. Four groups were created based on the results from the threshold analysis: 1) no-low level of PTE (0–<10 cigarettes per day) and no maternal postnatal ND (n= 487, the reference group), 2) PTE (≥ 10 cigarettes/day) but no ND (n= 98), 3) ND with no-low PTE (0–9 cigarettes/day) (n= 88), and 4) PTE and ND (n= 111). The proportions of adolescent risk for ND in these groups were 6.2%, 17.3%, 9.1%, and 21.6% for first trimester PTE, respectively. For third trimester exposure, the proportions of adolescent risk for ND in these groups were 5.7%, 17.9%, 9.9%, and 21.3%. The rate of adolescent ND in the first trimester PTE-only group was almost three times higher than the rate for the reference group, but this was only marginally significant after controlling for the demographic variables using regression. The third trimester PTE only group was significantly different from the referent group (AOR = 2.27, 95% CI= 1.16–4.43). Adolescent risk for ND was significantly different between the maternal postnatal ND with no/low PTE group and the PTE + maternal ND group, but the difference between the no-low PTE (0–9 cigarettes/day) and the PTE (at threshold of at least 10 cigarettes/day) + maternal ND groups did not reach statistical significance.

4. Discussion

Our analyses revealed a threshold effect of PTE at 10 cigarettes/day on adolescent risk for ND. However, there was no evidence for an additive effect of maternal postnatal ND (ND), because adolescents exposed to prenatal tobacco at this level in addition to maternal postnatal ND were not significantly more likely to be at risk for ND than adolescents with only PTE. ND symptoms develop rapidly in young smokers (Hu et al., 2012) so adolescence is an important period to examine predictors of risk for ND such as PTE. In prior work focusing on the role of PTE on ND, very high levels of PTE (a pack or more of cigarettes daily during pregnancy) were associated with ND in adults (Buka et al., 2003; Shenassa et al., 2015). We found an effect of PTE on adolescent risk for ND at the much lower threshold of 10 cigarettes per day. This is important because 8% of American women continue to smoke during pregnancy (Curtin & Mathews, 2016), but smokers on average are smoking fewer cigarettes per day (Curtin & Mathews, 2016; Rodriquez et al., 2016). Even though some authors have reported effects of PTE on smoking and ND in adult females but not in adult males (e.g., Kandel et al., 1994; Rydell et al., 2012; Stroud et al., 2014), we did not find sex-specific effects of PTE on adolescent risk for ND.

In contrast to previous investigations of the effects of PTE on adolescent ND, we also focused on the potential effect of maternal postnatal ND. The results demonstrate that PTE predicted adolescent risk for ND in regression models including maternal postnatal ND, whereas maternal postnatal ND was not significant in those models. These results are not consistent with prior work on a smaller sample using a retrospective report of any PTE (Kandel et al., 2007) that predicted ND in adolescent smokers using a scale developed by the Tobacco Etiology Research Network. Some researchers have argued that PTE is a marker for maternal postnatal ND (Agrawal et al., 2008; D’Onofrio et al., 2012). In our cohort, the majority of women who smoked during their pregnancy were also assessed as ND 16 years post-partum. However, we detected an independent effect of PTE, and maternal postnatal ND was not significant in regression models with first or third trimester PTE.

This study has several strengths, including prospective data on a large sample with mothers first assessed in early pregnancy. The proportions of smoking and ND in these birth cohorts were consistent with national estimates (Dierker et al., 2012). The study had twice the number of participants as the other study (Kandel et al., 2007) that considered the role of maternal postnatal ND and PTE in tandem as predictors of risk for adolescent ND. However, there was not enough power to include additional covariates that may influence adolescent risk for ND, such as family status and maternal mental health. Additionally, the FTND is a well-established measure of ND, but not designed as a formal diagnostic assessment of ND (Colby et al., 2000). Another limitation of the study was that maternal and child smoking and ND were based on self-report. PTE and maternal postnatal ND are also two very different measures of exposure to maternal smoking, with ND generally reflecting a more serious level of exposure, confounding time and mode of exposure with intensity. Future work should also consider the role of paternal smoking and adolescent risk for ND, and include families from a more general population.

Conclusions

These findings have implications for clinical work with women of reproductive age and also for research on the long-term effects of PTE. Researchers interested in adolescent risk for ND should also include measures of PTE in their models, preferably prospective measures of cigarettes per day per trimester rather than retrospective reports or dichotomous measures such as any smoking during pregnancy or heavy smoking during pregnancy. This was the first study to consider the effects of threshold levels of PTE during different trimesters on risk for adolescent ND. Assessing frequency and quantity of smoking for first and third trimesters of pregnancy allowed us to determine how early in pregnancy and what levels of PTE predict adolescent ND. The effect sizes for third trimester PTE were larger, suggesting that women who continue to smoke throughout their pregnancy may be putting their children at greater risk for ND. However, first trimester PTE was also significant, indicating that it is important to target pregnant smokers at the first prenatal visit for smoking cessation therapy. Helping mothers achieve smoking cessation, especially during pregnancy, may be the key to breaking the inter-generational cycle of smoking.

Figure 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Adolescent risk for ND by Exposure Groups

*significantly different from the referent group (p < .05).

Highlights.

Prenatal tobacco exposure (PTE) predicts risk for adolescent nicotine dependence (ND).

There is a threshold effect for prenatal tobacco exposure (10 cigarettes/day).

Maternal postnatal ND does not predict risk for adolescent ND when controlling for PTE.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (DA037209, AA06390, AA08284, AA022473, DA03874, DA09275).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Agrawal A, Knopik VS, Pergadia ML, Waldron M, Bucholz KK, Martin NG, et al. Correlates of cigarette smoking during pregnancy and its genetic and environmental overlap with nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:567–78. doi: 10.1080/14622200801978672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Scherrer J, Grant J, Sartor C, Pergadia M, Duncan A, et al. The effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring outcomes. Prev Med. 2010;50:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azagba S, Asbridge M. Nicotine dependence matters: Examining longitudinal association between smoking and physical activity among Canadian adults. Prev Med. 2013;57:652–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidwell LC, Palmer RH, Brick L, Madden PA, Heath AC, Knopik VS. A propensity scoring approach to characterizing the effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring’s initial responses to cigarettes and alcohol. Behavior Genetics. 2016;46:416–30. doi: 10.1007/s10519-016-9791-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Johnson EO. Predicting smoking cessation and major depression in nicotine-dependent smokers. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1122. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buka SL, Shenassa ED, Niaura R. Elevated risk of tobacco dependence among offspring of mothers who smoked during pregnancy: a 30-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1978–84. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1978. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CA, Espy KA, Wakschlag L. Developmental pathways from prenatal tobacco and stress exposure to behavioral disinhibition. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2016;53:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SM, Tiffany ST, Shiffman S, Niaura RS. Are adolescent smokers dependent on nicotine? A review of the evidence. Drug Alc Depend. 2000;59:83–95. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius M, Geva D, Day N, Cornelius J, Taylor P. Patterns and covariates of tobacco use in a recent sample of pregnant teenagers. J Adolesc Health. 1994;15:528–535. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(94)90135-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius M, Ryan C, Day N, Goldschmidt L, Willford J. Prenatal tobacco effects on neuropsychological outcomes of preadolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2001;22:217–225. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200108000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, Leech SL, Goldschmidt L, Day NL. Prenatal tobacco exposure: is it a risk factor for early tobacco experimentation? Nicotine Tob Res. 2000;2:45–52. doi: 10.1080/14622200050011295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, Leech SL, Goldschmidt L, Day NL. Is prenatal tobacco exposure a risk factor for early adolescent smoking? A follow-up study. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2005;27:667–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, Goldschmidt L, De Genna N, Day N. Smoking during teenage pregnancies: effects on behavioral problems in offspring. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:739–50. doi: 10.1080/14622200701416971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, De Genna NM, Leech SL, Willford JA, Goldschmidt L, Day NL. Effects of prenatal cigarette smoke exposure on neurobehavioral outcomes in 10-year-old children of adolescent mothers. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2011;33:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Hussong AM. Integrative data analysis: the simultaneous analysis of multiple data sets. Psychol Methods. 2009;14:81–100. doi: 10.1037/a0015914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. National vital statistics reports. 1. Vol. 65. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. Smoking prevalence and cessation before and during pregnancy: Data from the birth certificate, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day L, Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Cornelius MD. Effects of prenatal tobacco exposure on preschoolers’ behavior. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000;21(3):180–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Swendsen J, Rose J, He J, Merikangas K, Tobacco Etiology Research Network Transitions to regular smoking and nicotine dependence in the Adolescent National Comorbidity Survey (NCS-A) Ann Beh Med. 2012;43:394–401. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9330-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Rickert ME, Langstrom N, Donahue KL, Coyne CA, Larsson H, et al. Familial confounding of the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring substance use and problems. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1140–50. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Rende R, Boergers J, Abrams DB, Buka SL, Clark MA, Colby SM, Hitsman B, Kazura AN, Lipsitt LP, Lloyd-Richardson EE. Parental smoking and adolescent smoking initiation: an intergenerational perspective on tobacco control. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e274–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt L, Cornelius MD, Day NL. Prenatal cigarette smoke exposure and early initiation of multiple substance use. Nicotine & Tob Res. 2012;14:694. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British J Addiction. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M-C, Griesler PC, Schaffran C, Wall MM, Kandel DB. Trajectories of criteria of nicotine dependence from adolescence to early adulthood. Drug Alc Depend. 2012;125:283–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Hu MC, Griesler PC, Schaffran C. On the development of nicotine dependence in adolescence. Drug Alc Depend. 2007;91:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Griesler PC, Hu M. Intergenerational patterns of smoking and nicotine dependence among US adolescents. Am J Pub Hlth. 2015;105:e63–e72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays D, Gilman SE, Rende R, Luta G, Tercyak KP, Niaura RS. Parental smoking exposure and adolescent smoking trajectories. Pediatrics. 2014;133:983–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, de Moor CA, Hudmon KS, Kelder SH, Conroy JL, Ordway N. Nicotine dependence, withdrawal symptoms, and adolescents’ readiness to quit smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:151–5. doi: 10.1080/14622200110043068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriquez EJ, Oh SS, Perez-Stable EJ, Schroeder SA. Changes in smoking intensity over time by birth cohort and by Latino national background, 1997–2014. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydell M, Cnattingius S, Granath F, Magnusson C, Galanti MR. Prenatal exposure to tobacco and future nicotine dependence: population-based cohort study. Brit J Psychiatry. 2012;200:202–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.100123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydell M, Granath F, Cnattingius S, Svensson AC, Magnusson C, Galanti MR. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring’s tobacco dependence. A study of exposure-discordant sibling pairs. Drug Alc Depend. 2016;167:23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selya AS, Dierker LC, Rose JS, Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ. Risk factors for adolescent smoking: parental smoking and the mediating role of nicotine dependence. Drug Alc Depend. 2012;124:311–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenassa ED, Papandonatos GD, Rogers ML, Buka SL. Elevated risk of nicotine dependence among sib-pairs discordant for maternal smoking during pregnancy: evidence from a 40-year longitudinal study. Epidemiology. 2015;26:441–47. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Tate CA, Cousins MM, Seidler FJ. Prenatal nicotine exposure alters the responses to subsequent nicotine administration and withdrawal in adolescence: serotonin receptors and cell signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2462–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud LR, Papandonatos G, Shenassa E, et al. Prenatal glucocorticoids and maternal smoking during pregnancy independently program adult nicotine dependence in daughters: A 40-year prospective study. Biological Psychiatry. 2014;75:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weden MM, Miles JN. Intergenerational relationships between the smoking patterns of a population-representative sample of US mothers and the smoking trajectories of their children. Am J Pub Hlth. 2012;102:723–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]